What the CRS Report on Regional Innovation Ecosystems Gets Right and Misses

At the beginning of April, the Congressional Research Service (CRS) released a landmark report outlining the scope of federal investments in regional ecosystems, something we have written about at FAS in the past. This CRS report, ‘Regional Innovation: Federal Programs and Issues for Consideration,’ does an excellent job covering the scope and scale of our massive federal investment in innovation ecosystems. It also raises some important questions that legislators would do well to consider. But there are a few places where deeper and more practice-grounded perspectives on innovation ecosystems are needed for Congress to effectively oversee federal programs. Read on to see what highlights and added thoughts we have for lawmakers who wish to invest in regional innovation.

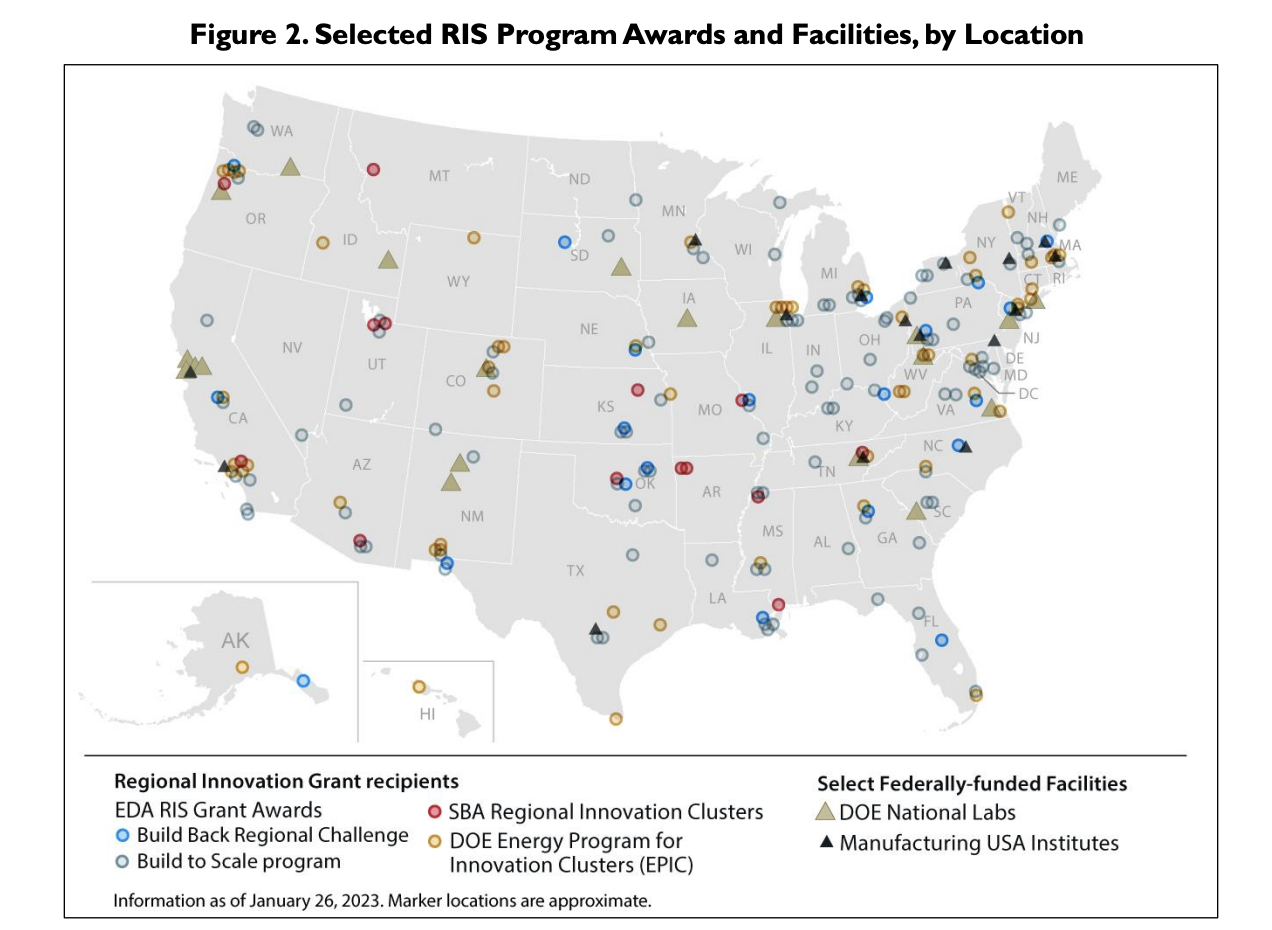

The recent expansion of federal support for RIS policies may expand the nation’s innovation capacity by helping regional economies address barriers to entrepreneurship and the development and commercialization of certain technology areas. Source.

CRS Highlights

The report connects investment in innovation ecosystems to investments in the critical technologies that will improve our national competitiveness in the long-term.

This CRS report lays out clearly and in detail, for the first time that we’ve seen, the connection between the legislative intent of a national technology competitiveness strategy (expressed via the CHIPS and Science Act) and regional innovation ecosystems. It also lists the ten identified critical technology areas in the same place. Did you feel a breeze? It’s a collective sigh of relief from ecosystem builders across the country who now have a simple guide to the technologies that they ought to consider building an ecosystem around. The report lists those as:

- Artificial intelligence, machine learning, autonomy, and related advances

- High performance computing, semiconductors, and advanced computer hardware and software

- Quantum information science and technology

- Robotics, automation, and advanced manufacturing

- Natural and anthropogenic disaster prevention or mitigation

- Advanced communications technology and immersive technology

- Biotechnology, medical technology, genomics, and synthetic biology

- Data storage, data management, distributed ledger technologies, and cybersecurity, including biometrics

- Advanced energy and industrial efficiency technologies, such as batteries and advanced nuclear technologies

- Advanced materials science, including composites 2D materials, other next- generation materials, and related manufacturing technologies

There you have it, folks. Wise ecosystem builders would do well to consider whether the cluster they’ve been working to build advances one of these key technology areas, and where their competitive advantage lies within these. It’s important, however, that the report explicitly says this list is a guide and not a requirement, and that communities will likely choose the clusters that they build for many reasons–some more closely tied to local economic conditions and assets.

What is more, the report recognizes that, “‘regional economic development is often a long-term process,” and thus Congress needs to consider the long view when it comes to funding periods and appropriating money for programs to advance Regional Innovation Strategies (RIS). Such patience is necessary to see world-class clusters develop to their full potential.

We have now seen the writing on the wall–the federal government has invested in regional innovation ecosystems because leaders see them as a path to improving national competitiveness, which they define in terms of these ten critical technologies. The only question left to answer is: how does your region’s work support this vision? If what you’re building isn’t on this list of ten technologies, you’d better have a darn good reason.

The report sets up a stakeholder framework as a basis for understanding and evaluating innovation ecosystems.

The report defines regional innovation ecosystems using a stakeholder model. This is very similar to the FAS view–that innovation ecosystems are made up of different stakeholder groups, working together in a complex, adaptive system to advance a shared vision. In fact, that philosophy is at the core of the comments we made to help inform the Tech Hubs and Recompetes programs. The stakeholder groups that CRS identifies don’t fully align with our understanding of successful ecosystems, especially with regards to distinguishing between small and large firms within ‘private industry.’ But the basic idea is important; definitionally, regional innovation ecosystems are groups of people.

The report rightly calls out the fact that innovation ecosystems aren’t always accessible or inclusive–and that they sometimes create more prosperity for those who are already very privileged.

As the report outlines considerations for Congress, it rightly acknowledges that traditionally, innovation ecosystems have not been forces for equity and inclusion. Building inclusive Tech-Based Economic Development (TBED) movements requires navigating many layers of systemic wrongs, including (but not limited to) racism, sexism, and their intersectional impacts. The majority of past TBED efforts have failed to produce equitable outcomes for left behind groups. Over the years, too many have written these challenges off as “pipeline problems” without also investing the time and effort necessary to understand the work that equity would require.

This is why CRS should not frame RIS as just ‘a place-based form of TBED.” This regards the current regional innovation programs as more or less contiguous with past TBED efforts, and fails to fully envision how RIS programs could look different. Modern innovation ecosystems are about much more than just helping those with a Ph.D. in biology roll the next pharmaceutical innovation out of an R1 university lab.

The report questions how agencies might coordinate to ensure that all federally-funded regional innovation ecosystem programs work together to promote innovation everywhere.

Another aspect of this report that should be lauded is its call for interagency collaboration. Federal agencies should work together to advance a shared vision of renewed national competitiveness. This method of alignment is often called “collective impact.” There are clear steps that agency leaders can and should take, inspired by this framework, to align around shared strategies: they should agree on a common agenda (both Congress and the Executive branch have a role here); they should agree to a shared system of measurement and evaluation; they should consider how to best design the programs they manage to be mutually reinforcing; they should be empowered to engage in continuous, expedited communication that is unburdened by bureaucracy; and they need a “backbone organization” or at the very least, a forum, that can be used to hold all federal stakeholders accountable to this shared plan.

Additional considerations for Congress

The underlying purpose of innovation ecosystems is to make it easier for new companies to enter a market; entrepreneurship is not an incidental benefit, it is the entire point.

One casualty of the broad political acceptance of cluster development as economic development is that we have lost touch with the reason we build clusters to begin with. We don’t build clusters because more clusters are good. We don’t build clusters because they create jobs (although the productivity increases that they enable often result in job growth). We build clusters because they fundamentally change the dynamics of an industry on a local scale, giving one geographic place the ability to build specialized capabilities to support the growth of companies in a specific industry. Because it is often difficult for those specialized capabilities to be replicated without great expense, that place then has a sustainable advantage in supporting companies in an industry. As they say in the business school world, that place has ‘built a moat,’ that will protect its unique regional assets from the globally competitive hordes. This ‘moat’ is effective because “new entrants” (startups) find it much easier to enter the market when they have access to these specialized capabilities–and they would find it much more difficult and expensive to start the same business in a community without those resources.

In the context of today’s regional innovation ecosystems, a community’s ‘moat’ might look like a shared, subsidized lab space that allows biotech companies to reduce the cost of developing a technology and completing clinical trials by sharing the burden of building expensive Bio Security Level – 2 labs. BioSTL’s lab facility in St. Louis is one example which reduces local companies’ barriers to entry in the biotech market. It might also look like the innovation matchmaking programs conducted by the Milwaukee Water Council, which connect startups with the Council’s 250 member companies like Molson Coors and Culligan–an advantage that you’d probably put in the “five forces” category of customer power. It might look like the work being done to repurpose Wichita’s legacy aerospace manufacturing capabilities for a new smart manufacturing era through broad worker training, building a new ‘supplier power’ in terms of the supply of labor. Each of these interventions makes it easier for “new market entrants” to succeed and grow. Startups are, fundamentally, new market entrants.

We have forgotten that job creation is an incidental output of the act of starting a business, not the other way around. This is an important distinction, because it leads to the mistaken logic that any job ‘created’ in a place that has a cluster is the same as any other. This logic lumps together startups and larger, older companies as ‘the private sector.’ This is irresponsible because new, small businesses really are the engines here. Research suggests that all net new job creation in the U.S. is attributable to new companies, even to the point that they offset job losses from older companies. This is not to say that larger and older companies do not have important roles in innovation ecosystems—they do. More established companies serve as customers, investors, and acquirers of startups. They often take cues from disruptive startup competitors that lead to improvements in their own productivity and profitability. They employ lots of people by virtue of their size. But to mistake their role as that of generators, and not consumers, of innovation can be very, very expensive.

Lumping together the interests of large companies and startups as “the private sector” jeopardizes the effectiveness of our investments in innovation ecosystems, and therefore American competitiveness, altogether. In the future, the CRS should consider revising their stakeholder model to recognize the meaningfully different role of startups as other models do.

Domestic cluster selection decisions are not made in an analytical vacuum. They are organic and social decision making processes that are also path dependent.

The point of federal program evaluation is not to assess whether communities have made the ‘right’ decision, but to assess whether the federal government’s support is making a difference in a given community’s growth trajectory. In its discussion of the need for better evaluation and measurement of federal regional innovation ecosystem programs, the CRS cites a bevy of academic studies published in peer-reviewed journals that speak to how communities ought to choose clusters in the context of a variety of statistical frameworks and analyses. But they reflect academic understanding of the observable factors of an ecosystem, not the day-to-day reality of ecosystem builders working to build coalitions through a consensus process. That renders them incomplete as an analytical tool.

This is why: Imagine yourself in the shoes of an ecosystem builder. You are likely managing a number of direct support programs for entrepreneurs, attending a bevy of community meetings and working groups on topics ranging from regional economic development to neighborhood disputes, all while trying to maintain a broad professional network, adjuncting a class at your local university, and representing the voice of entrepreneurs in your state legislature with no funding or help (after all, Foundations can’t fund lobbying activity and entrepreneurs are busy running their businesses). When the EDA announces the next grant opportunity (and that your application is due in 60 days), your first thought is likely along the lines of, “Well, I guess I am going to have to fit that into my 1-3 a.m. email answering time.”

The reality is that many communities and the ecosystem builders that lead them–especially those that do not already have a functioning cluster with rich local support–begin thinking about their plans to build a cluster shortly after they hear about opportunities to fund that work. Their analyses of what cluster to build are not informed by carefully replicated statistical models, pulling from the methodology sections of the papers cited in this report. Should communities be thinking more proactively about these opportunities? Certainly. Do resources and tools exist to support them as they do that work? They do not. The best-supported communities can count on philanthropic funding of consultants from McKinsey, Deloitte, and Brookings to support them as they assemble their plans. Those communities have already won EDA Build Back Better and Good Jobs Challenge and are well on their way to winning an NSF Engine award. Those that remain have won nothing, and have already invested time in two to three failed efforts. Insanity, it is said, is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.

So how are decisions made in these cities that are not among the shining few? How do they choose what cluster to build, when to pivot and when to stop trying and put their time and effort elsewhere? FAS is working to interview a cohort of the cities that have as yet, been left out of federal funding for innovation ecosystems. We’ll soon publish a series of blogs telling their stories, and drawing insights from their shared experiences. In the meantime, our early returns show that these decisions are more likely to be made behind closed doors in a Chamber of Commerce board room than in consultation with statistical models. It is our hope that this effort can help to inform programs still to come, especially the Recompetes program created in the CHIPS and Science Act. The success of federal investments should be judged on the basis of how much they improve the capacity of a region’s innovation ecosystem, via the capacity of its stakeholders.

Place-based TBED is not sufficient to build an inclusive innovation ecosystem.

Page 3 of the CRS report explicitly says, “The RIS approach is a place-based form of TBED.” While that might have been true when Congress first began funding the Regional Innovation Strategies Program in 2014, times have changed. Today, building innovation ecosystems that advance American competitiveness and provide opportunity for all requires a much broader approach–one that includes but is not limited to TBED strategies. Ten years ago, many regional innovation ecosystem movements were primarily focused on the effective and speedy commercialization of university technology. That approach and its single-minded focus on the most highly educated, well-credentialed people with entrepreneurial potential has led us to a place where many don’t believe that innovation ecosystems can be inclusive. But there is another way of building inclusive access to innovation for those who have been more often impacted by it.

Today, workforce development and broad entrepreneurship support are commonly understood to be important added elements of ecosystem building strategies. These are aspects of ecosystem building that are not always well-supported by a TBED approach. But these two strategies are not enough, because alone they create, essentially, two classes of innovation ecosystem participant: one that has the education and support necessary to become “an innovator” and benefit from the opportunity for massive wealth creation, and another, less well-resourced class of ecosystem participant who can be part of “the workforce,” limiting their options for wealth creation. In some ways, this responds to the reality that we see across our country–that access to generational wealth, and thus access to the capital needed to start an innovation-led enterprise, is deeply inequitable. It also reflects deep and systemic inequities in access to educational opportunity, to networks, and even in the group of model entrepreneurs that one can look up to as an example. Given these inequities, building systems that produce more equitable outcomes will be challenging. But it is not impossible and for the good of all of us, we should try.

This moment, and the emerging thinking around cluster development as a tool to advance not just economic development, but also industrial policy, may just provide us an opportunity to think differently (and more inclusively) about regional innovation ecosystems. What is the primary difference between TBED strategies focused on university commercialization and industrial policy, focused on producing semiconductors, biotechnology, and advanced manufacturing capabilities? It is supply chains–which often include small and midsize enterprises with the potential for high growth and broad wealth creation. It is also commonly understood that these supply chains don’t exist today in the way that they need to. To us, that sounds like a call for the creation of a generation of growth-capable small businesses, grounded in skills like process manufacturing, bench science, and component assembly–skills that are much more broadly distributed across our country than Ph.D. credentials.

The inclusive innovation ecosystems of the future will require diverse pipelines of university innovators, and workforce development that trains people for good jobs in these critical technology industries. It will also require adequately supporting opportunities to start and grow new small businesses in critical technology industries, inclusive and locally preferential supplier pipelines, and new markets for main street businesses that are an important part of making places vibrant as they attract “the workforce” needed to grow (and in that, new pathways to provide amnesty for, formalize, and grow the informal businesses that are common in systemically disinvested communities). It will require small armies of sole proprietors that support and provide affordable expertise to help companies–whether small businesses or startups–grow, like graphic designers, communications advisors, manufacturing consultants, CPAs, lawyers, tax preparers, and wealth advisors.

Most importantly, the inclusive innovation ecosystem of the future will require opportunities for people who have traditionally been disenfranchised, experimented on, priced out of their own homes, and left behind in the name of growth and innovation. In order to have truly equitable impacts, in fact, we must prioritize this kind of restitution via wealth creation. New models are emerging from the grassroots, like community wealth-building trusts and requirements for small business opportunities in first-floor retail. Entire innovation districts are being built explicitly around the needs of Black innovators, such as the Sankofa Innovation District in Omaha. Does this sound like TBED to you? Because to us, it sounds like something much richer, more inclusive, more equitable, and more liberating.

It is in the interests of the United States to appropriately protect information that needs to be protected while maintaining our participation in new discoveries to maintain our competitive advantage.

Our analysis of federal AI governance across administrations shows that divergent compliance procedures and uneven institutional capacity challenge the government’s ability to deploy AI in ways that uphold public trust.

To secure the U.S. bio-infrastructure, maintain global leadership in biotechnology, and safeguard American citizens from emerging threats to their privacy, the federal government must modernize its approach to human genetic and biological data.

From use to testing to deployment, the scaffolding for responsible integration of AI into high-risk use cases is just not there.