Investing in Young Children Strengthens America’s Global Leadership

Supporting the world’s youngest children is one of the smartest, most effective investments in U.S. strength and soft power. The cancellation of 83 percent of foreign assistance programs in early 2025, coupled with the dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), not only caused unnecessary suffering of millions of young children in low-income countries, but also harmed U.S. security, economic competitiveness, and global leadership. As Congress crafts legislation to administer foreign assistance under a new America First focused State Department, it should recognize that renewed attention and support for young children in low-income countries will help meet stated U.S. foreign assistance priorities to make America safer, stronger, and more prosperous. Specifically, Congress should: (1) prioritize funding for programs that promote early childhood development; (2) bolster State Department staffing to administer resources efficiently; and (3) strengthen accountability and transparency of funding.

Challenge and Opportunity

Supporting children’s development through health, nutrition, education, and protection programs helps the U.S. achieve its national security and economic interests, including the Administration’s priorities to make America “safer, stronger, and more prosperous.” Investing in global education, for example, generates economic growth overseas, creating trade opportunities and markets for the U.S. In fact, 11 of America’s top 15 trading partners once received foreign aid. Healthy, educated populations are associated with less conflict and extremism, which reduces pressures on migration. Curbing the spread of infectious diseases like HIV/AIDS and Ebola makes Americans safer from disease both abroad and at home. As a diplomacy tool, providing support for early childhood development, which is a priority in many partner countries, increases U.S. goodwill and influence in these countries and contributes to its geopolitical competitiveness.

Helping young children thrive in low-income countries is a high-return investment in stable economies, skilled workforces, and a stronger America on the world stage. In a July 2025 press release, the State Department recognized how investing in children and families globally contributes to America’s national development and priorities:

Supporting children and families strengthens the foundation of any society. Investing in their protection and well-being is a proven strategy for ensuring American security, solidifying American strength, and increasing American prosperity. When children and families around the world thrive, nations flourish.

The first five years of a child’s life is a period of unprecedented brain development. Investments in early childhood programs – including parent coaching, child care, and quality preschool – yield large and long-term benefits for individuals and society-at-large, up to a 13% return on investment, particularly when these interventions are targeted to the most vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. Despite the promise of early childhood interventions, 43% of children under five in low- and middle-income countries are at elevated risk of poor development, leaving them vulnerable to the long-term negative impacts of adversity, such as poverty, malnutrition, illness, and exposure to violence. The costs of inaction are high; countries that underinvest in young children are more likely to have less healthy and educated populations and to struggle with higher unemployment and lower GDPs.

Informed by this powerful evidence, the bipartisan Global Child Thrive Act of 2020 required U.S. Government agencies to develop and implement policies to advance early childhood development – the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional development of children up to age 8 – in partner countries. This legislation supported early childhood development through nutrition, education, health, and water, sanitation, and hygiene interventions. It mandated the U.S. Government Special Advisor for Children in Adversity to lead a coordinated, comprehensive, and effective U.S. government response through international assistance. The bipartisan READ Act complements the Thrive Act by requiring the U.S. to implement an international strategy for basic education, starting with early childhood care and education.

Three examples of USAID-funded early childhood programs terminated in 2025 illustrate how investments in young children not only achieve multiple development and humanitarian goals, but also address U.S. priorities to make America safer, stronger, and more prosperous:

- Cambodia. Southeast Asia is of strategic importance to U.S. security given risks of China’s political and military influence in the region. The Integrated Early Childhood Development activity ($20 million) helped young children (ages 0-2) and their caregivers through improved nutrition, responsive caregiving, agricultural practices, better water, sanitation, and hygiene, and support for children with developmental delays or disabilities. Within a week of cancellation, China filled the USAID vacuum and gained a soft-power advantage by announcing funding for a program to achieve almost identical goals.

- Honduras. Foreign assistance mitigates poverty, instability, and climate shocks that push people to migrate from Central America (and other regions) to the U.S. The Early Childhood Education for Youth Employability activity ($8 million) aimed to improve access to quality early learning for more than 100,000 young children (ages 3-6) while improving the employability and economic security for 25,000 young mothers and fathers, a two-generation approach to address drivers of irregular migration.

- Ethiopia. The U.S. has a long-standing partnership with Ethiopia to increase stability and mitigate violent extremism in the Horn of Africa. Fostering peace and promoting security, in turn, expands markets for American businesses in the region. Through a public-private partnership with the LEGO Foundation, the Childhood Development Activity ($46 million) reached 100,000 children (ages 3-6+) in the first two years of the program with opportunities for play-based learning and psycho-social support for coping with negative effects of conflict and drought.

Drastic funding cuts have jeopardized the wellbeing of vulnerable children worldwide and the “soft power” the U.S. has built through relationships with more than 175 partner countries. In January 2025, the Trump Administration froze all foreign assistance and began to dismantle the USAID, the lead coordinating agency for children’s programs under the Global Child Thrive Act and READ Act. By March 2025, sweeping cuts ended most USAID programs focused on children’s education, health, water and sanitation, nutrition, infectious diseases (malaria, tuberculosis, neglected tropical diseases, and HIV/AIDS), and support for orphans and vulnerable children. In total, the U.S. eliminated around $4 billion in foreign assistance intended for children in the world’s poorest countries. As a result, an estimated 378,000 children have died from preventable illnesses, such as HIV, malaria, and malnutrition.

In July 2025, Congress voted to approve the Administration’s rescission package, which retracts nearly $8 billion of FY25 foreign assistance funding that was appropriated, but not yet spent. This includes support for 6.6 million orphans and vulnerable children (OVC) and $142 million in core funding to UNICEF, the UN agency which helps families in emergencies and vulnerable situations globally. An additional $5 billion of foreign assistance funding expired at the end of the fiscal year while being withheld through a pocket rescission.

As Congress works to reauthorize the State Department, and what remains of USAID, it should see that helping young children globally supports both American values and strategic interests.

Recent U.S. spending on international children’s programs accounted for only 0.09% of the total federal budget and only around 10% of foreign assistance expenditure. If Congress does not act, this small, but impactful funding is at risk of disappearing from the FY 2026 budget.

Plan of Action

For decades, the U.S. has been a leader in international development and humanitarian assistance. Helping the world’s youngest children reach their potential is one of the smartest, most effective investments the U.S. government can make. Congress needs to put in place funding, staffing, and accountability mechanisms that will not only support the successful implementation of the Global Child Thrive Act, but also meet U.S. foreign policy priorities.

Recommendation 1. Prioritize funding for early childhood development through the Department of State

In the FY26 budget currently under discussion, Congress has the responsibility to fund global child health, education, and nutrition programs under the authority of the State Department. These child-focused programs align with America’s diplomatic and economic interests and are vital to young children’s survival and well-being globally.

To promote early childhood development specifically, the Global Child Thrive Act should be reauthorized under the auspices of the State Department. While there is bipartisan support in the House Foreign Affairs Committee to extend authorization of the Global Child Thrive Act through 2027, the current bill had not made it to the House floor as of October 2025, and the Senate bill was delayed by a federal government shutdown.

Congress should pass legislation to appropriate $1.5 billion in FY26 funding for life-saving and life-changing programs for young children, including:

- The Vulnerable Children’s Account which funds multi-sectoral, evidence-based programs that support the objectives of the Global Child Thrive Act and the Advancing Protection and Care for Children in Adversity Strategy ($50 million).

- PEPFAR 10% Orphans and Vulnerable Children Set Aside which protects and promotes the holistic health and development of children affected by HIV/AIDS ($710 million).

- UNICEF core funding, given the agency’s track record in advancing early childhood development programs in development and humanitarian settings ($300 million).

- Commitments to government-philanthropy partnerships with pooled funds that prioritize the early years including the Global Partnership for Education, Education Cannot Wait, the Early Learning Partnership, and the Global Financing Facility ($430 million).

Funding should be written into legislation so that it is protected from future cuts.

Recommendation 2. Adequately staff the State Department to coordinate early childhood programs

The State Department needs to rebuild expertise on global child development that was lost when USAID collapsed. As a first step, current officials need to be briefed on relevant legislation including the Global Child Thrive Act and the READ Act. In response to the reduced capacity, Congress should fund a talent pipeline in order to attract a cadre of professionals within the State Department in Washington, DC and at U.S. Embassies who can focus on early years issues across sectors and funding streams. Foreign nationals who have a deep understanding of local contexts should be considered for these roles.

In the context of scarce resources, coordination and collaboration is more important than ever. The critical role of the USG Special Advisor for Children in Adversity should be formally transferred to the State Department to provide technical leadership and implementation support for children’s issues. Within the reorganized State Department, the Special Advisor should sit in the office of the Under Secretary for Foreign Assistance, Humanitarian Affairs and Religious Freedom (F), where s/he can serve as a leading voice for children and foster inter-agency coordination across the Departments of Agriculture and Labor, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, etc.

Congress also should seek clarification on how the new Special Envoy for Best Future Generations will contribute specifically to early childhood development. The State Department appointed the Special Envoy in June 2025 as a liaison for initiatives impacting the well-being of children under age 18 in the U.S. and globally. In the past three months, the Special Envoy has met with U.S. government officials at the White House and State Department, representatives from 14 countries at the U.N., and non-governmental organizations to discuss coordinated action on children’s issues, such as quality education, nutritious school meals, and ending child labor and trafficking.

Recommendation 3. Increase accountability and transparency for funds allocated for young children

Increased oversight over funds can improve efficiency, prevent delays, and reduce risks of funds expiring before they reach intended families. The required reporting on FY24 programs is overdue and should be submitted to Congress by the end of December 2025.

Going forward, Congress should require the State Department to report regularly and testify on how money is being spent on young children. Reporting should include evidence-based measures of Return on Investment (ROI) to help demonstrate the impact of early childhood programs. In addition, the Office of Foreign Assistance should issue a yearly report to Congress and to the public which tracks annual inter-agency progress toward implementing the Global Child Thrive Act using a set of indicators, including the approved pre-primary indicator and other relevant and feasible indicators across age groups, programs, and sectors.

Conclusion

Investing in young children’s growth and learning around the world strengthens economies, builds goodwill, and secures America’s position as a trusted global leader. To help reach U.S. foreign policy priorities, Congress must increase funding, staffing and accountability of the State Department’s efforts to promote early childhood development, while also strengthening multi-agency coordination and accountability for achieving results. The Global Child Thrive Act provides the legislative mandate and a technical roadmap for the U.S. Government to follow.

By investing only about 1% of the federal budget, USAID contributed to political stability, economic growth, and good will with partner countries. A new Lancet article estimates USAID funding saved 30 million children’s lives between 2001 and 2021 and was associated with a 32% reduction in under five deaths in low- and middle-income countries. In the past five years alone, funding supported the learning of 34 million children. USAID spending was heavily examined by the State Department, Congress, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Office of the Inspector General. Recent claims of waste, fraud, and abuse are inaccurate, exaggerated or taken out of context.

The public strongly supports many aspects of foreign assistance that benefit children. A recent Pew Research Study found that around 80% of Americans agreed that the U.S. should provide medicine and medical supplies, as well as food and clothing, to people in developing countries. In terms of political support, children’s programs are viewed favorably by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. For example, the Global Child Thrive Act was introduced by Representatives Joaquin Castro (D-TX) and Brian Fitzpatrick (R-PA) and Senators Roy Blunt (R-MO) and Christopher Coons (D-DE) and passed with bipartisan support from Congress.

AI Implementation is Essential Education Infrastructure

State education agencies (SEAs) are poised to deploy federal funding for artificial intelligence tools in K–12 schools. Yet, the nation risks repeating familiar implementation failures that have limited educational technology for more than a decade. The July 2025 Dear Colleague Letter from the U.S. Department of Education (ED) establishes a clear foundation for responsible artificial intelligence (AI) use, and the next step is ensuring these investments translate into measurable learning gains. The challenge is not defining innovation—it is implementing it effectively. To strengthen federal–state alignment, upcoming AI initiatives should include three practical measures: readiness assessments before fund distribution, outcomes-based contracting tied to student progress, and tiered implementation support reflecting district capacity. Embedding these standards within federal guidance—while allowing states bounded flexibility to adapt—will protect taxpayer investments, support educator success, and ensure AI tools deliver meaningful, scalable impact for all students.

Challenge and Opportunity

For more than a decade, education technology investments have failed to deliver meaningful results—not because of technological limitations, but because of poor implementation. Despite billions of dollars in federal and local spending on devices, software, and networks, student outcomes have shown only minimal improvement. In 2020 alone, K–12 districts spent over $35 billion on hardware, software, curriculum resources, and connectivity—a 25 percent increase from 2019, driven largely by pandemic-related remote learning needs. While these emergency investments were critical to maintaining access, they also set the stage for continued growth in educational technology spending in subsequent years.

Districts that invest in professional development, technical assistance, and thoughtful integration planning consistently see stronger results, while those that approach technology as a one-time purchase do not. As the University of Washington notes, “strategic implementation can often be the difference between programs that fail and programs that create sustainable change.” Yet despite billions spent on educational technology over the past decade, student outcomes have remained largely unchanged—a reflection of systems investing in tools without building the capacity to understand their value, integrate them effectively, and use them to enhance learning. The result is telling: an estimated 65 percent of education software licenses go unused, and as Sarah Johnson pointed out in an EdWeek article, “edtech products are used by 5% of students at the dosage required to get an impact”.

Evaluation practices compound the problem. Too often, federal agencies measure adoption rates instead of student learning, leaving educators confused and taxpayers with little evidence of impact. As the CEO of the EdTech Evidence Exchange put it, poorly implemented programs “waste teacher time and energy and rob students of learning opportunities.” By tracking usage without outcomes, we perpetuate cycles of ineffective adoption, where the same mistakes resurface with each new wave of innovation.

Implementation Capacity is Foundational

A clear solution entails making implementation capacity the foundation of federal AI education funding initiatives. Other countries show the power of this approach. Singapore, Estonia, and Finland all require systematic teacher preparation, infrastructure equity, and outcome tracking before deploying new technologies, recognizing, as a Swedish edtech implementation study found, that access is necessary but not sufficient to achieve sustained use. These nations treat implementation preparation as essential infrastructure, not an optional add-on, and as a result, they achieve far better outcomes than market-driven, fragmented adoption models.

The United States can do the same. With only half of states currently offering AI literacy guidance, federal leadership can set guardrails while leaving states free to tailor solutions locally. Implementation-first policies would allow federal agencies to automate much of program evaluation by linking implementation data with existing student outcome measures, reducing administration burden and ensuring taxpayer investments translate into sustained learning improvements.

The benefits would be transformational:

- Educational opportunity. Strong implementation support can help close digital skill gaps and reduce achievement disparities. Rural districts could gain greater access to technical assistance networks, students with disabilities could benefit from AI tools designed with accessibility at their core, and all students could build the AI literacy necessary to participate in civic and economic life. Recent research suggests that strategic implementation of AI in education holds particular promise for underserved and geographically isolated communities.

- Workforce development. Educators could be equipped to use AI responsibly, expanding coherent career pathways that connect classroom expertise to emerging roles in technology coaching, implementation strategy, and AI education leadership. Students graduating from systematically implemented AI programs would enter the workforce ready for AI-driven jobs, reducing skills gaps and strengthening U.S. competitiveness against global rivals.

In short, implementation is not a secondary concern; it is the primary determinant of whether AI in education strengthens learning or repeats the costly failures of past ed-tech investments. Embedding implementation capacity reviews before large-scale rollout—focused on educator preparation, infrastructure adequacy, and support systems—would help districts identify strengths and gaps early. Paired with outcomes-based vendor contracts and tiered implementation support that reflects district capacity, this approach would protect taxpayer dollars while positioning the United States as a global leader in responsible AI integration.

Plan of Action

AI education funding must shift to being both tool-focused and outcome-focused, reducing repeated implementation failures and ensuring that states and districts can successfully integrate AI tools in ways that strengthen teaching and learning. Federal guidance has made progress in identifying priority use cases for AI in education. With stronger alignment to state and local implementation capacity, investments can mitigate cycles of underutilized tools and wasted resources.

A hybrid approach is needed: federal agencies set clear expectations and provide resources for implementation, while states adapt and execute strategies tailored to local contexts. This model allows for consistency and accountability at the national level, while respecting state leadership.

Recommendation 1. Establish AI Education Implementation Standards Through Federal–State Partnership

To safeguard public investments and accelerate effective adoption, the Department of Education, working in partnership with state education agencies, should establish clear implementation standards that ensure readiness, capacity, and measurable outcomes.

- Implementation readiness benchmarks. Federal AI education funds should be distributed with expectations that recipients demonstrate the enabling systems necessary for effective implementation—including educator preparation, technical infrastructure, professional learning networks, and data governance protocols. ED should provide model benchmarks while allowing states to tailor them to local contexts.

- Dedicated implementation support. Funding streams should ensure AI education investments include not only tool procurement but also consistent, evidence-based professional development, technical assistance, and integration planning. Because these elements are often vendor-driven and uneven across states, embedding them in policy guidance helps SEAs and local education agencies (LEAs) build sustainable capacity and protect against ineffective or commodified approaches—ensuring schools have the human and organizational capacity to use AI responsibly and effectively.

- Joint oversight and accountability. ED and SEAs should collaborate to monitor and publicly share progress on AI education implementation and student outcomes. Metrics could be tied to observable indicators, such as completion of AI-focused professional development, integration of AI tools into instruction, and adherence to ethical and data governance standards. Transparent reporting builds public trust, highlights effective practices, and supports continuous improvement, while recognizing that measures of quality will evolve with new research and local contexts.

Recommendation 2. Develop a National AI Education Implementation Infrastructure

The U.S. Department of Education, in coordination with state agencies, should encourage a national infrastructure that helps and empowers states to build capacity, share promising practices, and align with national economic priorities.

- Regional implementation hubs. ED should partner with states to create regional AI education implementation centers that provide technical assistance, professional development, and peer learning networks. States would have flexibility to shape programming to their context while benefiting from shared expertise and federal support.

- Research and evaluation. ED, in coordination with the National Science Foundation (NSF), should conduct systematic research on AI education implementation effectiveness and share annual findings with states to inform evidence-based decision-making.

- Workforce alignment. Federal and state education agencies should continue to coordinate AI education implementation with existing workforce development initiatives (Department of Labor) and economic development programs (Department of Commerce) to ensure AI skills align with long-term economic and innovation priorities.

Recommendation 3. Adopt Outcomes Based Contracting Standards for AI Education Procurement

The U.S. Department of Education should establish outcomes based contracting (OBC) as a preferred procurement model for federally supported AI education initiatives. This approach ties vendor payment directly to demonstrated student success, with at least 40% of contract value contingent on achieving agreed-upon outcomes, ensuring federal investments deliver measurable results rather than unused tools.

- Performance-based payment structures. ED should support contracts that include a base payment for implementation support and contingent payments earned only as students achieve defined outcomes. Payment should be based on individual student achievement rather than aggregate measures, ensuring every learner benefits while protecting districts from paying full price for ineffective tools.

- Clear outcomes and mutual accountability:. Federal guidance should encourage contracts that specify student populations served, measurable success metrics tied to achievement and growth, and minimum service requirements for both districts and vendors (including educator professional learning, implementation support, and data sharing protocols).

- Vendor transparency and reporting. AI education vendors participating in federally supported programs should provide real-time implementation data, document effectiveness across participating sites, and report outcomes disaggregated by student subgroups to identify and address equity gaps.

- Continuous improvement over termination. Rather than automatic contract cancellation when challenges arise, ED should establish systems that prioritize joint problem-solving, technical assistance, and data-driven adjustments before considering more severe measures.

Recommendation 4. Pilot Before Scaling

To ensure responsible, scalable, and effective integration of AI in education, ED and SEAs should prioritize pilot testing before statewide adoption while building enabling conditions for long-term success.

- Pilot-to-scale strategy. Federal and state agencies could jointly identify pilot districts representing diverse contexts (rural, urban, and suburban) to test AI implementation models before large-scale rollout. Lessons learned would inform future funding decisions, minimize risk, and increase effectiveness for states and districts.

- Enabling conditions for sustainability. States could build ongoing professional learning systems, technical support networks, and student data protections to ensure tools are used effectively over time.

- Continuous improvement loop. ED could coordinate with states to develop feedback systems that translate implementation data into actionable improvements for policy, procurement, and instruction, ensuring educators, leaders, and students all benefit.

Recommendation 5. Build a National AI Education Research & Development Network

To promote evidence-based practice, federal and state agencies should co-develop a coordinated research and development infrastructure that connects implementation data, policy learning to practice, and global collaboration.

- Implementation research partnerships. Federal agencies (ED, NSF) should partner with states and research institutions to fund systematic studies on effective AI education implementation, with emphasis on scalability and outcomes across diverse student populations. Rather than creating a new standalone program, this would coordinate existing ED and NSF investments while expanding state-level participation.

- Testbed site networks. States should designate urban, suburban, and rural AI education implementation labs or “sandboxes”, modeled on responsible AI testbed infrastructure, where funding supports rigorous evaluation, cross-district peer learning, and local adaptation.

- Evidence-to-policy pipeline. Federal agencies should integrate findings from these research-practice partnerships into national AI education guidance, while states embed lessons learned into local technical assistance and professional development.

- National leadership and evidence sharing. Federal and state agencies should establish mechanisms to share evidence-based approaches and emerging insights, positioning the U.S. as a leader in responsible AI education implementation. This collaboration should leverage continuous, practice-informed research, called living evidence, which integrates real-world implementation data, including responsibly shared vendor-generated insights, to inform policy, guide best practices, and support scalable improvements.

Conclusion

The Department’s guidance on AI in education marks a pivotal step toward modernizing teaching and learning nationwide. To realize the promise of AI in education, funding should support both the acquisition of tools and the strategies that ensure their effective implementation. To realize its promise, we must shift from funding tools to funding effective implementation. Too often, technologies are purchased only to sit on the shelf while educators lack the support to integrate them meaningfully. International evidence shows that countries investing in teacher preparation and infrastructure before technology deployment achieve better outcomes and sustain them.

Early research also suggests that investments in professional development, infrastructure, and systems integration substantially increase the long-term impact of educational technology. Prioritizing these supports reduces waste and ensures federal dollars deliver measurable learning gains rather than unused tools. The choice before us is clear: continue the costly cycle of underused technologies or build the nation’s first sustainable model for AI in education—one that makes every dollar count, empowers educators, and delivers transformational improvements in student outcomes.

Clear implementation expectations don’t slow innovation—they make it sustainable. When systems know what effective implementation looks like, they can scale faster, reduce trial-and-error costs, and focus resources on what works to ultimately improve student outcomes.

Quite the opposite. Implementation support is designed to build capacity where it’s needed most. Embedding training, planning, and technical assistance ensures every district, regardless of size or resources, can participate in innovation on an equal footing.

AI education begins with people, not products. Implementation guidelines should help educators improve their existing skills to incorporate AI tools into instruction, offer access to relevant professional learning, and receive leadership support, so that AI enhances teaching and learning.

Implementation quality is multi-dimensional and may look different depending on local context. Common indicators could include: educator readiness and training, technical infrastructure, use of professional learning networks, integration of AI tools into instruction, and adherence to data governance protocols. While these metrics provide guidance, they are not exhaustive, and ED and SEAs will iteratively refine measures as research and best practices evolve. Transparent reporting on these indicators will help identify effective approaches, support continuous improvement, and build public trust.

Not when you look at the return. Billions are spent on tools that go underused or abandoned within a year. Investing in implementation is how we protect those investments and get measurable results for students.

The goal isn’t to add red tape—it’s to create alignment. States can tailor standards to local priorities while still ensuring transparency and accountability. Early adopters can model success, helping others learn and adapt.

In Honor of Patient Safety Day, Four Recommendations to Improve Healthcare Outcomes

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is working to ensure that rigorous, evidence-based ideas on the cutting edge of disease prevention and health outcomes are reaching decision makers in an effective and timely manner. To that end, we have been collaborating with the Strengthening Pathways effort, a series of national conversations held in spring 2025 to surface research questions, incentives, and overlooked opportunities for innovation with potential to prevent disease and improve outcomes of care in the United States. FAS is leveraging its skills in policy entrepreneurship, working with session organizers, to ensure that ideas surfaced in these symposia reach decision-makers to drive impact in active policy windows.

On this World Patient Safety Day 2025, we share a set of recommendations that align with the National Quality Strategy of Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) goal for zero preventable harm in healthcare. Working with Patients for Patient Safety US, which co-led one of Strengthening Pathways conversations this spring with the Johns Hopkins University Armstrong Institute for Patient Safety and Quality, the issue brief below outlines a bold, modernized approach that uses Artificial Intelligence technology to empower patients and drive change. FAS continues to explore the rapidly evolving AI and healthcare nexus.

Patient safety is an often-overlooked challenge in our healthcare systems. Whether safety events are caused by medical error, missed or delayed diagnoses, deviations from standards of care, or neglect, hundreds of billions of dollars and hundreds of thousands of lives are lost each year due to patient safety lapses in our healthcare settings. But most patient safety challenges are not really captured and there are not enough tools to empower clinicians to improve. Here we present four critical proposals for improving patient safety that are worthy of attention and action.

Challenge and Opportunity

Reducing patient death and harm from medical error surfaced as a U.S. public health priority at the turn of the century with the landmark National Academy of Sciences (NAS) report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (2000). Research shows that medical error is the 3rd largest cause of preventable death in the U.S. Analysis of Medicare claims data and electronic health records by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) Office of the Inspector General (OIG) in a series of reports from 2008 to 2025 consistently finds that 25-30% of Medicare recipients experience harm events across multiple healthcare settings, from hospitals to skilled nursing facilities to long term care hospitals to rehab centers. Research on the broader population finds similar rates for adult patients in hospitals. The most recent study on preventable harm in ambulatory care found that 7% of patients experienced at least one adverse event, with wide variation of 1.8% to 23.6% from clinical setting to clinical setting. Improving diagnostic safety has emerged as the largest opportunity for patient harm prevention. New research estimates 795,000 patients in the U.S. annually experience death or harm due to missed, delayed or ineffectively communicated diagnoses. The annual cost to the health care system of preventable harm and its health care cascades is conservatively estimated to exceed $200 billion. This cost is ultimately borne by families and taxpayers.

In its National Quality Strategy, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) articulated an aspirational goal of zero preventable harm in healthcare. The National Action Alliance for Patient and Workforce Safety, now managed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), has a goal of 50% reduction in preventable harm by 2026. These goals cannot be achieved without a bold, modernized approach that uses AI technology to empower patients and drive change. Under-reporting negative outcomes and patient harms keeps clinicians and staff from identifying and implementing solutions to improve care. In its latest analysis (July 2025), the OIG finds that fewer than 5% of medical errors are ever reported to the systems designed to gather insights from them. Hospitals failed to capture half of harm events identified via medical record review, and even among captured events, few led to investigation or safety improvements. Only 16% of events required to be reported externally to CMS or State entities were actually reported, meaning critical oversight systems are missing safety signals entirely.

Multiple research papers over the last 20 years find that patients will report things that providers do not. But there has been no simple, trusted way for patient observations to reach the right people at the right time in a way that supports learning and Improvement. Patients could be especially effective in reporting missed or delayed diagnoses, which often manifest across the continuum of care, not in one healthcare setting or a single patient visit. The advent of AI systems provides an unprecedented opportunity to address patient safety and improve patient outcomes if we can improve the data available on the frequency and nature of medical errors. Here we present four ideas for improving patient safety.

Recommendation 1. Create AI-Empowered Safety Event Reporting and Learning System With and For Patients

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) can, through CMS, AHRQ or another HHS agency, develop an AI-empowered National Patient Safety Learning and Reporting System that enables anyone, including patients and families, to directly report harm events or flag safety concerns for improvement, including in real or near real time. Doing so would make sure everyone in the system has the full picture — so healthcare providers can act quickly, learn faster, and protect more patients.

This system will:

- Develop a reporting portal to collect, triage and analyze patient reported data directly from beneficiaries to improve patient and diagnostic safety.

- Redesign and modernize Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems

(CAHPS) surveys to include questions that capture beneficiaries’ experiences and outcomes related to patient and diagnostic safety events.

- Redefine the Beneficiary and Family Centered Care Quality Improvement Organizations (BFCC QIO) scope of work to integrate the QIOs into the National Patient Safety Learning and Reporting System.

The learning system will:

- Use advanced triage (including AI) to distinguish high-signal events and route credible

reports directly to the care team and oversight bodies that can act on them.

- Solicit timely feedback and insights in support of hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes to prevent recurrence, as well as feedback over time on patient outcomes that manifest later, e.g. as a result of missed or delayed diagnoses.

- Protect patients and providers by focusing on efficacy of solutions, not blame assignment.

- Feed anonymized, interoperable data into a national learning network that will spot systemic risks sooner and make aggregated data available for transparency and system learning.

Recommendation 2. Create a Real-time ‘Patient Safety Dashboard’ using AI

HHS should build an AI-driven platform that integrates patient-reported safety data — including data from the new National Patient Reporting and Learning System, recommended above — with clinical data from electronic health records to create a real-time ‘patient safety dashboard’ for hospitals and clinics. This dashboard will empower providers to improve care in real time, and will:

- Assist health care providers make accurate and timely diagnoses and avoid errors.

- Make patient reporting easy, effective, and actionable.

- Use AI to triage harm signals and detect systemic risk in real time.

- Build shared national infrastructure for healthcare reporting for all stakeholders.

- Align incentives to reward harm reduction and safety.

By harnessing the power of AI providers will be able to respond faster, identify patients at risk more effectively, and prevent harm thereby improving outcomes. This “central nervous system” for patient safety will be deployed nationally to help detect safety signals in real time, connect information across settings, and alert teams before harm occurs.

Recommendation 3. Mine Billing Data for Deviations from Standards of Care

Standards of care are guidelines that define the process, procedures and treatments that patients should receive in various medical and professional contexts. Standards ensure that individuals receive appropriate and effective care based on established practices. Most standards of care are developed and promulgated by medical societies. But not all clinicians and clinical settings adhere to standards of care, and deviations from standards of care are normal depending upon the case before them. Nonetheless, standards of care exist for a reason and deviations from standards of care should be noted when medical errors result in negative outcomes for patients so that clinicians can learn from these outcomes and improve.

Some patient safety challenges are evident right in the billing data submitted to CMS and insurers. For example, deviations from standards of care can be captured in billing data by comparing clinical diagnosis codes with billing codes and then compared to widely accepted standards of care. By using CMS billing data, the government could identify opportunities for driving the development, augmentation, and wider adoption of standards of care by showing variability and compliance with standards of care for patients, reducing medical error and improving outcomes.

Giving standard setters real data to adapt and develop new standards of care is a powerful tool for improving patient outcomes.

Recommendation 4. Create a Patient Safety AI Testbed

HHS can also establish a Patient Safety AI Testbed to evaluate how AI tools used in diagnosis, monitoring, and care coordination perform in real-world settings. This testbed will ensure that AI improves safety, not just efficiency — and can be co-led by patients, clinicians, and independent safety experts. This is an expansion of the testbeds in the HHS AI Strategic Plan.

The Patient Safety Testbed could include:

- Funding for independent AI test environments to monitor real-world safety and performance over time.

- Public reliability benchmarks and “AI safety labeling”.

- Required participation by AI vendors and provider systems.

Conclusion

There are several key steps that the government can take to address the major loss of health, dollars, and lives due to medical errors, while simultaneously bolstering treatment guidelines, driving the development of new transparent data, and holding the medical establishment accountable for improving care. Here we present four proposals. None of them are particularly expensive when juxtaposed against the tremendous savings they will drive throughout our healthcare system. We can only hope that the Administration’s commitment to patient safety is such that they will adopt them and drive a new era where caregivers, healthcare systems and insurance payers work together to improve patient safety and care standards.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

ASTRA: An American Space Transformation Regulatory Act

From helping farmers maximize crop yields to creating new and exotic pathways for manufacturing, the space economy has the potential to triple over the next decade. Unlocking abundance in the space economy will require lowering the barriers for new space actors, aligning with international partners, and supporting traditional measures of risk assessment (like insurance) to facilitate space investment.

Unlike countries with newer space programs that can benefit from older programs’ experience, exploration, and accidents, the United States has organically developed a patchwork regime to manage human and non-human space flight. While this approach serves and supports the interests of government agencies and their mission-specific requirements, it hinders the deployment of new and novel technologies and gives other countries motive to deploy extraterritorial regulatory regimes, further complicating the outlook for new space actors. There is an urgent need for rationalization, as well as for a clear and logical pathway for the deployment of new technologies, and to facilitate responsible activities in orbit so that space resources need not be governed by scarcity.

As the impacts of human space activities become more clear, there is also a growing need to address the sustainability of human space operations and their capacity to restrain a more abundant human future. While the recent space commercialization executive order attempts to rationalize some of this work, it also preserves some of the regulatory disharmony that exists in the current system while taking actions that are likely to create additional conflicts with impacted communities. The United States should re-take the lead; among the examples set by New Zealand, the European Union, and other emerging space actors; in providing a comprehensive space regulatory framework that ensures the safe, sustainable, and responsible growth of the space industry.

Challenge and Opportunity

The Outer Space Treaty creates a set of core responsibilities that must be followed by any country wishing to operate a space program, including (but not limited to) international responsibility for national activities, authorization and supervision of space activities carried out by non-governmental entities, and liability for damage caused to other countries. In the United States, individual government agencies have adopted responsibilities over individual elements of human activity in space, including (but again, not limited to) the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) over launch and reentry, the Department of Commerce (DOC) over remote sensing, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and DOC over spectrum management, and the State Department and DOC over space-related export controls. The FCC has also asserted its regulatory authority over space into other domains, in particular the risk of in-space collision and space debris. If a company wishes to launch a satellite with remote sensing capabilities, they need to participate in every single one of these regulatory permitting processes.

Staffing and statutory authority create significant challenges for American space regulators at a time when other countries are getting their respective regulatory houses in order. The offices that manage these programs are relatively small – the Commercial Remote Sensing Regulatory Affairs (CRSRA) division of the Office of Space Commerce (OSC) currently staffed by two full time government employees while the FAA has only five handling space flight authorizations. CRSRA was briefly hamstrung earlier this year when its director was released (and then immediately rehired) as part of the Trump Administration’s firing of probationary employees at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration–likely collateral damage in the Administration’s attempts to target programs that interact with climate change.

The lack of personnel capacity creates particular challenges for the FAA, which has struggled to keep pace with launch approvals under its Part 450 launch authorization process, among a record-breaking number of mishap investigations, novel space applications, and application revisions in 2023. Last year, FAA officials testified that the increase in SpaceX launches, alone, has led to hundreds of hours of monthly overtime logged, constituting over 80% of staff overtime paid for by the American taxpayer. Other companies have described that accidents from SpaceX-related launches create shifting goalposts for their companies, pushing FAA officials to avoid confirming receipt of necessary launch documents to avoid starting Part 450’s 180 day review deadline. The shifting goalposts and prior approvals also means that certain launch vehicles are subject to different requirements, creating incentives for companies to focus their efforts on non-commercial and defense-related missions.

Without updates to the law, the statutory justification for increasingly important regulatory responsibilities is also unsound, particularly those that pertain to orbital debris. After the Supreme Court’s Loper Bright ruling, it is unlikely that the theory of law underpinning FCC’s regulation of space debris could withstand court challenges. This creates a particularly dangerous situation given the long-term impact that the breakup of even small objects can have on the orbital environment, and is likely the reason that space companies have yet to openly challenge the FCC’s assertion of regulatory authority in this space. This also challenges the insurance industry, which has suffered significant financial losses over the past few years and caused certain companies to pull out of the market entirely.

As human space activities increase, the demands created by the Outer Space Treaty’s requirement for supervision and liability are likely to also see corresponding increases. Some countries hosting astronomical observatories that are significantly impaired by light, radio, and other electromagnetic pollution from commercial spacecraft have enacted laws relating to satellite brightness and interference. The number of high-profile debris strikes on property – like when a metal component from the international space station crashed into a Florida family’s occupied home – will also increase as second stages of rockets and larger satellites return to earth. The Mexican government is exploring options to sue SpaceX over environmental contamination and debris near its Starbase Texas launch site.

The unique properties of interstellar space and other planetary surfaces demand other considerations we take for granted on Earth. On Earth, we consider the flexibility of nature to “heal itself” and revert to “natural” states of being, regrowth, and regeneration of destructive resource extraction. Instead, planetary surfaces with little to no atmosphere or wind, such as the moon, will preserve footprints and individual tire tracks for decades to thousands of years, altering the geological features. Flecks of paint and bacteria from rovers can create artificial signatures in spectroscopy and biology, contaminating science in undocumented ways that are likely to interrupt astrobiology and geology for generations to come. We risk rendering an advanced human civilization unable to unlock discoveries resulting from pristine science or explore the existence of extraterrestrial life.

Significant safety concerns resulting from increased human space activities could create additional regulatory molasses if unaddressed. An increasing and under-characterized population of debris increases risk to multi-million dollar instruments and continued operations in the event of a collision cascade. Current studies – both conservative and optimistic – point to the fact we are already in the regime of “unstable” debris growth in orbit, complicating the mass-deployment of large constellations.

Unfortunately, current international law creates challenges for the mass-removal of orbital debris. Article 8 of the Outer Space Treaty establishes that ownership of objects in space does not change by virtue of being in space. This is done to make the seizure of other countries’ objects illegal, and it isn’t difficult to imagine weaponizing satellite removal capabilities (seen in the James Bond film “You Only Live Twice”). If it is not financially advantageous to mitigate space debris, or export control concerns prevent countries from allowing debris removal, then the most-likely long term results are either unchecked debris growth, likely leading to increasingly draconian regulatory requirements. None of this is good for industry.

Absent a streamlined data-sharing platform of satellite location and telemetry, which could be decimated by federal cuts to the Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS), the cost and responsibility of satellite collision and debris avoidance will encourage many commercial space operators to fly blind. The underutilized space insurance industry, already reeling from massive losses in recent years, would face another source of pressure. If the barriers to satellite servicing and recovery satellites remain high, it is probable that the only market for such capabilities will be military missions, inherently inhibiting the ability of these systems to attend to the orbital environment.

While abundance speaks to increasing available resources, chemistry and the law of conservation of matter remind us that our atmosphere and the oxygen we breathe is finite, fragile, and potentially highly reactive to elements commonly found in spacecraft. We are only starting to understand the impact of spacecraft reentry on the upper atmosphere, though there is already significant cause for concern. Nitrous oxide (NOx), a common compound used in spacecraft propulsion, is known to deplete ozone. Aluminum, one of the most common elements in spacecraft, bonds easily with ozone. Black carbon from launches increases stratospheric temperature, changing circulation patterns. When large rockets explode, the aftermath can create enormous impacts for aviation and rain debris on beaches and critical areas. To top it all off, the reliance of space companies on the defense sector for financing means that many of these assets and constellations are often inherently tied to defense activities, increasing the probability that they will be actively targeted or compromised as a result of foreign policy actions or fast-tracked due to regulatory streamlining that circumvents public comment periods from raising valid safety concerns.

We are quickly approaching a day when the United States government may no longer be the primary regulator of our own industry. The European Union in May 2025 introduced its own Space Act with extraterritorial requirements for companies wishing to participate in the European market. Many of these provisions are well-considered and justified, though the uncertainty and extra layer of compliance that they create for American companies is likely to increase the cost of business further. The EU has created a process for recognizing equivalent regimes in other countries. Under current rules, and especially under the Administration’s new commercial space executive order, the United States regulatory regime is unlikely to be judged as “equivalent.” Given the concerns from EU member states and companies alike about the actions of U.S. space companies, it is more likely than not that the EU will seek to rein in the U.S. space industry in ways that could limit our ability to remain internationally competitive.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Congress should devote resources to study that which threatens the abundance of space, such as the impacts of human space exploration, damage to the ozone layer; inadvertent geoengineering as a result of orbital reentry and fuel deposition.

This should include the impact of satellite interference on space situational awareness capabilities and space weather forecasting, which are critical to stabilizing the space economy.

While the regulatory environment for space should be rationalized to unleash the potential of the space economy, research is also needed to better understand the impacts of space activities and exploration given that we are already beginning to feel the impacts of space activities terrestrially. Having an abundant space economy is meaningless if the continual reentry of satellites destroys the ozone layer and renders the planet uninhabitable. Congress should continue to fund research on the upper atmosphere and protect research done by the NOAA Chemical Sciences Laboratory to understand the upper atmospheric impacts from human space activities.

The astronomy community has also voiced significant concerns about the impact of satellites on their observations. Satellites show up as bright streaks in the sky when taking pictures and can cause significant disruption to radio telescopes and weather forecasting sensors, alike. This impact is not only felt by ground-based telescopes and sensors, but also those in orbit like the Hubble. This could have consequences for tracking other interstellar phenomena, including (but not limited to) space debris, space weather, cislunar space domain awareness, and planetary defense. Further, light pollution inhibits our ability to discover new physics through astronomical observations–the Hubble Tension, neutrino mass problem, quantum gravity, and matter-antimatter imbalance all suggest that there are major discoveries waiting for us on the horizon. Failure to preserve the sky could inadvertently restrain our ability to unleash a technological revolution akin to the one that produced Einstein’s theory of relativity and the nuclear age.

There is still much more work to be done to understand these topics and to develop workable solutions that can be adopted by new space actors. The bipartisan Dark and Quiet Skies Act, introduced in 2024, narrowly addresses but one of these needs; sustained support for NASA, NOAA, and NSF science are all necessary given the technology required for taking measurements in the stratosphere and advanced metrology.

Recommendation 2. Congress should create an independent Space Promotion and Regulatory Agency.

Ideally, Congress should create a new and independent space promotion and regulatory agency whose activities would include both the promotion of civil and commercial space activities and provide for authorization and supervision of all U.S.-based commercial space organizations. This body, whose activities should be oriented to fulfilling U.S. obligations under the Outer Space Treaty, should be explicitly empowered to also engage in space traffic coordination or management, to manage liability for U.S. space organizations, and to rationalize all existing permitting processes under one organization. Staff from existing agencies (which is typically 2–25 people) should be relocated from existing departments and agencies to this new body to provide for continuity of operations and institutional knowledge.

Congress should seek to maintain a credible firewall between the promotion and regulatory elements of the organization. The promotion element could be responsible for providing assistance to companies (including through loans and grants for technology and product development like the DOE Loan Programs Office, and also general advocacy). The regulatory element should be responsible for domestic licensing space activities, operating the Traffic Coordination System for Space (TraCSS), and any other supervision activities that may become necessary. This would be distinct from the existing Office of Space Commerce function in that the organization would be independent, have the ability to regulate space commerce, and ideally have resources to fulfill the advocacy and promotion elements of the mission.

In an ideal world, the Office of Space Commerce (OSC) would be able to fulfill this mission with an expanded mission mandate, regulatory authority, and actual resources to promote commercial space development. In practice, recent events under both administrations have pointed toward the office being isolated within the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration under the Biden Administration while running into similar bottlenecks with the Secretary of Commerce in the second Trump Administration. Independent authority and resourcing would not only give the director greater plenary authority, but also allow them to better balance the views of interagency partners (and hopefully shedding some of the baggage that comes from broader relationships between government departments with broad mandates).

This recommendation explicitly does not suggest eliminating the FAA or OSC’s functions, but rather merging the two, preserving current staff and institutional knowledge, and allowing them to work in the same (and independent) organization to make it easier to share knowledge and information. Creating a new regulatory agency on top of the FAA or OSC is not recommended; the purpose is to streamline. Preference would be given toward assigning all of the functions to one actor or another rather than creating a new and duplicative function on top of the existing structures in Commerce and FAA.

Given the significant terrestrial impact of spectrum issues related to space, delegating those functions to the FCC and NTIA probably still makes sense, so long as orbital debris and other space regulatory functions are consolidated into a new body that is clearly given such regulatory authority by Congress.

Recommendation 3. Congress should consider requiring that insurance be purchased for all space activities to address the Outer Space Treaty’s liability requirements.

Insurance ensures that nascent areas of growth are minimally disruptive to other interests, i.e. damaging critical infrastructures such as spraying GPS satellites with debris shrapnel, or harming the general public when skyscraper-sized pressurized fuel tanks explode on the ground. Insurance is broadly recognized for its ability to help create the type of market stability that is necessary for large capital investments and promote long-term infrastructure improvements.

The participation of insurance markets is also more likely to encourage venture capital and financial industry participation in commercial space activities, moving the market from dependency on government funding toward self-sustaining commercial enterprise. Despite this, out of 13,000 active satellites, only about 300 are insured. The satellite insurance industry’s losses have been staggering over the last two years, making the pricing of risk difficult for new space actors and investors alike. Correct pricing of risk is essential for investors to be able to make informed decisions about which companies or enterprises to invest in.

Current insurance covers $500 million in damages to third parties – any costs beyond this are drawn from the reservoir of the American taxpayer (unless damages exceed a ceiling cap for the government of about $3.1 billion). The current incentive structure favors the deployment of cheap, mass produced satellites over more sophisticated vehicles that drive technological leadership and progress. The failure or loss of control over such assets can create a permanent hazard to the orbital environment and increase the risk of a collision cascade over the lifetime of the object. Increasing the number of covered satellites should help more correctly price overall market risk, making space investments more accessible and attractive for companies looking to deploy commercial space stations; in space servicing, assembly, and manufacturing satellites; and other similarly sophisticated investments. These types of technologies are more likely to contribute to abundance in the broader market, as opposed to a temporary, mass-produced investment that does only one thing and ends in a loss of everyone’s long-term access to specific orbits.

The Outer Space Treaty’s liability provisions make a healthy and risk-based insurance market particularly important. If a country or company invests in a small satellite swarm, and some percentage of that swarm goes defunct and produces a collision cascade and/or damages on-the ground assets, then U.S. entities (including the government) could be on the hook for potentially unlimited liabilities in a global multi-trillion dollar space economy. It is almost certain that the United States government has not adequately accounted for such an event and that risk is not currently priced into the market.

A thriving insurance market can also help facilitate other forms of investment, which may become more confident in their investments and tolerant of other risks associated with investment. It would also serve as an important signal to international partners that the United States is willing to act responsibly in the orbital environment and has the capacity to create the financial incentive schemes to honor its commitments. By requiring insurance, Congress can use the prescriptive power of law to ensure transparency for both investors and the general public.

Recommendation 4. The United States should create an inventory of abandoned objects and establish rules governing the abandonment of objects to enable commercial orbital salvage operations.

Given that Article 8 of the Outer Space Treaty could serve as an impediment to orbital debris removal, countries could establish rules or lists of objects that have reached end of life and are now effectively abandoned. The Treaty does not necessarily prevent State Parties from creating rules governing the authorization and supervision of objects, including transfer of ownership at the end of a mission. An inventory of abandoned objects that are “OK for recovery” could help manage concerns related to export controls, intellectual property, or other issues associated with one country recovering another country’s objects. Likewise, countries could also explore the creation of salvage rights or rules to incentivize orbital debris removal missions.

Recommendation 5. The State Department should seek equivalency for the United States under the EU Space Act as soon as possible, and seek to engage the EU in productive discussions to limit the probability of regulatory divergence, probably more than doubling the regulatory burden placed on U.S. companies.

With the introduction of the EU Space Act, the primary regulator for U.S. space companies with an international presence is likely to be the European Union. The U.S. Department of State should continue to pursue constructive engagement with the European Commission, Parliament, and Council to limit the risk of regulatory divergence and to ensure that the United States provides adequate safeguards to quickly achieve equivalency, obviating the need for U.S. space companies to worry about compliance with more than one country’s framework. This would ultimately result in lower regulatory burden for the United States, particularly if measures are taken to consolidate the existing U.S. space regulatory environment as described in Recommendation 2.

The failure of the U.S. to get its own house in order is likely to motivate other countries to take similar measures, increasing compliance costs for American companies while foreign operators may only need to rely on their domestic frameworks. Without equivalency, U.S. operators are likely to have to deal with multiple competing regulatory regimes, especially given the past history of other countries outside the EU adopting EU regulatory frameworks in order to secure market access (the Brussels Effect).

There is a foreign policy need for the U.S. and EU to get on the same page (and fast). Given that companies from the United States are more likely to seek access to European markets than those in the PRC, an asymmetric space policy environment opens a new sphere for contentious policy negotiations between the U.S. and EU. Transatlantic alignment is likely to produce greater leverage in negotiations with the PRC while creating a more stable market where U.S. and European industry can both thrive. Similarly, an antagonistic relationship is more likely to push the European Union toward greater strategic autonomy. Fear of dependence on U.S. companies is already creating new barriers for the United States in other areas, and space has been specifically called out as a key area of concern.

Further, space actors are less familiar with the extent to which trade negotiations can result in asymmetric concessions that could disadvantage one industry to gain benefits in another. To put it bluntly, it is unlikely that President Trump will go to bat for SpaceX (especially given his current relationship with its owner) if it means giving up opportunities to sell American farm exports. One need only look at the recent semiconductor export controls decision, allegedly done to facilitate a bilateral meeting between the two presidents in Beijing.

Conclusion

Unlocking the abundance of the space economy, and doing so responsibly, will require the development of a stable and trustworthy regulatory environment, repairing frameworks that enable monopolistic behavior, and correct pricing of risk in order to facilitate sustainable investment in the outer space environment. Abundance in one realm at the expense of all others (like when a new spacecraft pauses all air traffic in the Caribbean after exploding) is no longer “abundance.” If the United States does not act soon, the deployment of more modern regulatory frameworks by other countries offering a more agile environment for new technology deployment is likely to accelerate the growth of their advantages in orbit.

If space is there, and if we are going to climb it, then regulatory reform must be a challenge that we are willing to accept, something that we are unwilling to postpone, for a competition that we intend to win.

Clean Water: Protecting New York State Private Wells from PFAS

This memo responds to a policy need at the state level that originates due to a lack of relevant federal data. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has a learning agenda question that asks,“To what extent does EPA have ready access to data to measure drinking water compliance reliably and accurately?” This memo fills that need because EPA doesn’t measure private wells.

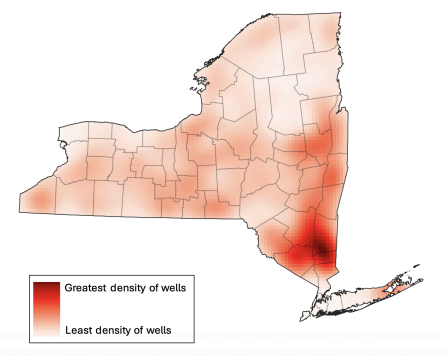

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are widely distributed in the environment, in many cases including the contamination of private water wells. Given their links to numerous serious health consequences, initiatives to mitigate PFAS exposure among New York State (NYS) residents reliant on private wells were included among the priorities outlined in the annual State of the State address and have been proposed in state legislation. We therefore performed a scenario analysis exploring the impacts and costs of a statewide program testing private wells for PFAS and reimbursing the installation of point of entry treatment (POET) filtration systems where exceedances occur.

Challenge and Opportunity

Why care about PFAS?

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a class of chemicals containing millions of individual compounds, are of grave concern due to their association with numerous serious health consequences. A 2022 consensus study report by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine categorized various PFAS-related health outcomes based on critical appraisal of existing evidence from prior studies; this committee of experts concluded that there is high confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) decreased antibody response (a key aspect of immune function, including response to vaccines) (2) dyslipidemia (abnormal fat levels in one’s blood), (3) decreased fetal and infant growth, and (4) kidney cancer, and moderate confidence of an association between PFAS exposure and (1) breast cancer, (2) liver enzyme alterations, (3) pregnancy-induced high blood pressure, (4) thyroid disease, and (5) ulcerative colitis (an autoimmune inflammatory bowel disease).

Extensive industrial use has rendered these contaminants virtually ubiquitous in both the environment and humans, with greater than 95% of the U.S. general population having detectable PFAS in their blood. PFAS take years to be eliminated from the human body once exposure has occurred, earning their nickname as “forever chemicals.”

Why focus on private drinking water?

Drinking water is a common source of exposure.

Drinking water is a primary pathway of human exposure. Combining both public and private systems, it is estimated that approximately 45% of U.S. drinking water sources contain at least one PFAS. Rates specific to private water supplies have varied depending on location and thresholds used. Sampling in Wisconsin revealed that 71% of private wells contained at least one PFAS and 4% contained levels of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), two common PFAS compounds, exceeding Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) of 4 ng/L. Sampling in New Hampshire, meanwhile, found that 39% of private wells exceeded the state’s Ambient Groundwater Quality Standards (AGQS), which were established in 2019 and range from 11-18 ng/L depending on the specific PFAS compound. Notably, while the EPA MCLs represent legally enforceable levels accounting for the feasibility of remediation, the agency has also released health-based, non-enforceable Maximum Contaminant Level Goals (MCLGs) of zero for PFOA and PFOS.

PFAS in private water are unregulated and expensive to remediate.

In New York State (NYS), nearly one million households rely on private wells for drinking water; despite this, there are currently no standardized well testing procedures and effective well water treatment is unaffordable to many New Yorkers. As of April 2024, the EPA has established federal MCLs for several specific PFAS compounds and mixtures of compounds and its National Primary Drinking Water Regulations (NPDWR) require public water systems to begin monitoring and publicly reporting levels of these PFAS by 2027; if monitoring reveals exceedances of the MCLs, public water systems must also implement solutions to reduce PFAS by 2029. In contrast, there are no standardized testing procedures or enforceable limits for PFAS in private water. Additionally, testing and remediating private wells are both associated with high costs which are unaffordable to many well owners; prices range in hundreds of dollars for PFAS testing and can cost several thousands of dollars for the installation and maintenance of effective filtration systems.

How are states responding to the problem of PFAS in private drinking water?

Several states, including Colorado, New Hampshire, and North Carolina, have already initiated programs offering well testing and financial assistance for filters to protect against PFAS.

- After piloting its PFAS Testing and Assistance (TAP) program in one county in 2024, Colorado will expand it to three additional counties in 2025. The program covers the expenses of testing and a $79 nano pitcher (point-of-use) filter. Residents are eligible if PFOA and/or PFOS in their wells exceeds EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L; filters are free if their household income is ≤80% of the area median income and offered at a 30% discount if this income criteria is not met.

- The New Hampshire (NH) PFAS Removal Rebate Program for Private Wells offers greater flexibility and higher cost coverage than Colorado PFAS TAP, with reimbursements of up to $5000 offered for either point-of-entry or point-of-use treatment system installation and up to $10,000 offered for connection to a public water system. Though other residents may also participate in the program and receive delayed reimbursement, households earning ≤80% of the area median family income are offered the additional assistance of payment directly to a treatment installer or contractor (prior to installation) so as to relieve the applicant of fronting the cost. Eligibility is based on testing showing exceedances of the EPA MCLs of 4 ng/L for PFOA or PFOS or 10 ng/L for PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (trademarked as “GenX”).

- The North Carolina PFAS Treatment System Assistance Program offers flexibility similar to New Hampshire in terms of the types of water treatment reimbursed, including multiple point-of-entry and point-of-use filter options as well as connection to public water systems. It is additionally notable for its tiered funding system, with reimbursement amounts ranging from $375 to $10,000 based on both the household’s income and the type of water treatment chosen. The tiered system categorizes program participants based on whether their household income is (1) <200%, (2) 200-400%, or (3) >400% the Federal Poverty Level (FPL). Also similar to New Hampshire, payments may be made directly to contractors prior to installation for the lowest income bracket, who qualify for full installation costs; others are reimbursed after the fact. This program uses the aforementioned EPA MCLs for PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA, or HFPO-DA (“GenX”) and also recognizes the additional EPA MCL of a hazard index of 1.0 for mixtures containing two or more of PFHxS, PFNA, HFPO-DA, or PFBS.

An opportunity exists to protect New Yorkers.