Innovation Ecosystem Job Board Launches to Connect Federal Talent to Opportunities

In a previous post, we announced an initiative to connect scientists, engineers, technologists, and skilled federal workers and contractors who have recently departed government service with the emerging innovation ecosystems across America that could use their expertise. With the support of FAS, we are now excited to share the launch of the Innovation Ecosystem Job Board. This unique job board contains opportunities from across the nation with the explicit goal of matching in-demand science and technology talent with open positions across the nation’s innovation ecosystems, in roles ranging from lab researchers and data scientists to workforce development practitioners and science communicators.

These innovation ecosystems – namely Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – are advancing critical technologies spanning from advanced manufacturing to quantum computing to biotech, all vital for our national and economic security. To accomplish this work, they operate as multi-stakeholder coalitions that bring together universities, industry, nonprofits, and other partners, all searching for talent to help them fulfill their missions.

These coalitions face growing talent needs, particularly for mission-driven roles that can help drive progress across critical technology areas. Meanwhile, we’re witnessing an exodus of thousands of experienced federal talent from agencies like the National Science Foundation, National Institutes for Health, and the Department of Energy whose knowledge gained from years of managing and working in multimillion-dollar technical programs could be lost entirely if not effectively redeployed.

This initiative directly addresses both challenges by collaborating with innovation ecosystems to identify their immediate talent needs while simultaneously engaging displaced federal workers through job fairs and targeted outreach to understand their backgrounds and geographic preferences. It’s a purposeful approach that ensures mission-driven federal talent can continue contributing to America’s technological leadership. By connecting talent to need, we help strategically imperative innovation ecosystems access the experienced professionals necessary for success.

We will be updating this job board regularly with opportunities from additional Tech Hubs, NSF Engines, and other innovation ecosystems. While our outreach is specifically to former federal workers and contractors, this job board is open to all, and we encourage others on the job hunt to take a look.

As economic policy wonks, we understand that there are often frictions that hinder matching between individuals with the right skills and geographic preferences and the jobs that exist. We are taking this seriously and will engage in what we’re calling “light-touch matching”. Please feel free to fill out this interest form (whether you have applied to a listing on the job board or not), and we will flag profiles that generally align with relevant innovation ecosystems and their needs.

Our process:

We spent the last several months talking to and learning from other talent connectors, innovation ecosystem builders, and the talent themselves. Through facilitated federal roundtables with former federal workers, we understood more deeply their diverse skill sets, their unwavering commitment to mission-driven work, and the unique challenges they face in their current job transition. Work for America’s research on federal workers also validated our hypotheses: these are experienced professionals (59% of survey respondents have a decade or more of experience), are geographically distributed (53% already live outside the DC-Virginia-Maryland area), and are mobile (54% are open to relocating). Job fairs additionally provided us an opportunity to meet individuals leaving the federal government and hear about their backgrounds and interests.

Simultaneously, we reached out to several innovation ecosystems to explore if they had immediate talent needs. Some ecosystems shared their most critical postings among their partners; others had recently conducted surveys of their coalitions to assess available positions and passed that information on to us; still others are actively developing comprehensive approaches to capture all the talent needs across their expansive coalitions. We reviewed and aggregated these opportunities into the job board which is now available and will be regularly updated. We are grateful for all these ecosystems that have engaged in this initiative and we look forward to continuing the conversation with more ecosystems and skilled former federal professionals alike.

Like anything new, this is an experiment. Does this effort in the end successfully match candidates and employers based on skills and geography? If you use this tool, please let us know how it goes!

Maryam Janani-Flores (mjananiflores@fas.org) is a Senior Fellow at FAS and former Chief of Staff at the U.S. Economic Development Administration. Meron Yohannes (myohannes@fas.org) is a Digital Services Alumni Fellow at FAS and most recently served as Senior Policy Advisor for the U.S. Secretary of Commerce.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Labor

Extreme heat is a major occupational hazard with far-reaching impacts on the national economy as well as worker health and safety. Extreme heat costs an estimated $100 billion per year in lost productivity, and causes an average of at least 3,389 heat-related injuries and 33 heat-related fatalities annually – numbers that are likely vast undercounts. To protect workers, Congress must mandate a federal heat standard, retain federal workers with expertise in heat stress management strategies, and establish Centers of Excellence to support research, training, and sector-specific mitigation strategies. Through investments in infrastructure for heat safety, Congress can save lives, protect the economy, and enhance resilience nationwide.

Heat-Related Risks are Heightened in Many Work Environments

Extreme heat puts workers of all types at risk: OSHA has documented hospitalizations and heat-related deaths in close to 275 industries. Some work environments present extreme heat risk, particularly those involving high exposures to the outdoors and limited access to cooling. With roughly one in three U.S. employees regularly working outdoors, a large share of the workforce is at elevated risk during summer months. Indoor workers also face high exposure, especially in kitchens, warehouses, manufacturing plants, and other poorly ventilated environments because heat and humidity easily build up in enclosed spaces without adequate air flow and climate-control.

Business and Economic Impacts of High Heat Exposure in the Workplace

On top of the $100 billion in direct annual losses, high temperatures are also linked to increased healthcare costs for employers and workers’ compensation claims, with claim frequencies rising by up to 10% during temperature extremes. Some industries are more exposed than others; for example, agriculture, construction, and utility companies face twice the risk of incurring increased healthcare claims due to extreme weather and other environmental conditions. This growing number of claims increases companies’ experience modification rates, which insurers use as a key factor for calculating higher future premiums. Higher premiums translate to greater insurance and overall operating costs, which is especially burdensome for small and low-margin businesses. Despite all these risks, many employers continue to underestimate the financial burden of extreme heat and other weather-related health impacts.

Many Military Personnel and Federal Workers Face Above-Average Risks of Heat-Related Illness

Military personnel, federal law enforcement officers, border patrol officers, wildland firefighters, federal transportation workers like railroad inspectors, and postal employees are all in positions that require long, labor-intensive hours outdoors, raising the risk for heat-related illness. In 2024, heat-related illnesses were among the top five most reported medical events among U.S. active duty service members. Without consistent standards in place to protect these workers from extreme heat, military and other federal operations will continue to be vulnerable to disruption and reduced workforce capacity.

Advancing Solutions: Establish a Strong Federal Heat Standard and Sector-Specific Centers of Excellence for Heat Workplace Safety

To begin to address heat-related injuries and illnesses in workplaces, OSHA in 2022 established the National Emphasis Program (NEP) on Outdoor and Indoor Heat-Related Hazards, which remains in effect until April 2026. As of 2025, OSHA reports that this NEP has conducted nearly 7,000 inspections connected to heat risks, which lead to 60 heat citations and nearly 1,400 “hazard alert” letters being sent to employers.

However, in the absence of a federal mandate for effective heat safety practices, most workplaces rely on voluntary guidance that is not tailored to specific job conditions, backed by consistent data, or subject to enforcement. This puts both workers and businesses at risk. OSHA’s proposed Heat Injury and Illness Prevention rule would be a critical step forward to establishing common-sense baseline protections. According to the agency’s projections, compliance with this standard could prevent thousands of heat-related illnesses and deaths. The projected benefits from reduced fatalities, illness, and injury amount to $9.18 billion per year. Importantly, this action has broad public backing: 90% of American voters support the implementation of federal protections from extreme heat in the workplace.

Congress should act swiftly to ensure OSHA finalizes and enforces a strong, evidence-based heat standard. To do this effectively, it is essential that funding for experts at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is retained in the FY26 budget request, as these critical workers develop criteria for recommended standards on occupational heat stress. These experts have been impacted by reductions in force at NIOSH, and as of July 2025 have not been brought back by the agency.

Some employers have raised concerns about the technical and financial feasibility of the proposed rule. To address these concerns, Congress should pair regulation with practical support by creating federally funded, sector-specific Centers of Excellence (CoEs)for Heat Workplace Safety. These Centers would develop and implement evidence-based solutions tailored to different work environments, such as agriculture and construction. The CoE approach includes comprehensive data collection at worksites that form the basis of occupational safety and health protocols best practices and policies to enhance productivity, prevent injury and illness, and ensure a return on investment. Once strategies are developed, CoEs implement them, track their impact, and work with workers, employers, and cross-sector partners to ensure long-term success.

By leveraging advanced technology, predictive analytics, and continuously updated industry standards, CoEs can help modernize OSHA regulations and make them more aligned with current workplace realities that go beyond simple compliance or post-injury responses. Federal agencies and other industries with sizable workforces that receive government contracts are key places to develop best practices, technologies, and public-private partnerships for these interventions, all while reducing fiscal risk to the federal government.

FAS Position on “Schedule PC” and Impact on Federal Scientists

FAS shares the following formal comment in the Federal Register and asks that the scientific community, and the people across the nation who benefit from their research, to do the same.

The Federation of American Scientists opposes the proposed “Schedule Policy/Career” (“Schedule PC”) in present form because it rescinds civil servant employment protections, placing unnecessary and undesirable political pressure on highly specialized scientific and technical career professionals serving in government.

FAS encourages the Office of Personnel Management to rescind or substantially overhaul the Proposed Rule on Improving Performance, Accountability and Responsiveness in the Civil Service. We ask that OPM respond to the following comments and reflect how it will revise the Proposed Rule or abandon it.

New Employment Category is Unnecessary

Instead of creating a new employment category – the Schedule P/C for federal civil servants – the same goals can be accomplished by requiring agencies to regularly review and update critical elements in the performance appraisal system and their rating factors. Changing performance elements will have the impact of ensuring attention to accountability and responsiveness to policy without the ambiguity or determining assignment to the Schedule or the taxpayer expense of defending it.

The Administration is already taking this action by changing the performance appraisal system for the Senior Executive Service to make senior executives more responsive to Executive-branch priorities and policies. FAS advocates for updates to performance standards and rating factors appropriate for non-executives–based on the best available evidence–to achieve the intended accountability and responsiveness goals in this Proposed Rule.

Proposed Rule Conflates Accountability with Administration

The Proposed Rule makes several errors in interpretation of the Civil Service Act of 1978, including the one potentially most detrimental to scientific enquiry, innovation, and exploration:

- The proposed rule is about accountability to the President and his/her Administration policies, not about performance on the job and accountability to the Constitution. By conflating the two, Schedule P/C takes away individual appeal rights for anyone reassigned to this categorization rather than focusing on removing poor performers. An employee’s poor performance is more commonly related to a lack of quality, accuracy, and/or timeliness of their job tasks, according to the U.S. Merit Systems Protection Board. As written, Schedule P/C also discourages dissent, evidence-based policymaking, performance management to understand and track results, and program evaluation to understand outcomes.

- The proposed rule newly defines Policy-Influencing Roles for merit-based civil servants, while underutilizing existing regulations for other Policy-Making roles like political appointees and those with excepted service employment.

- Newly designating “Policy-influencing” positions as Schedule P/C provides such a breadth of interpretation for federal agencies that it could encompass most federal jobs, which currently rely on a non-partisan, merit based civil service and their associated civil service protections. Already, a Social Security Administration (SSA) leader has voiced the intent to designate nearly all SSA career employees as Schedule P/C. Furthermore, the lack of guidance to agencies in identifying “policy influencing” roles will create inconsistencies in its application across agencies and confusion in comparing similar occupations and their duties.

- Moreover, the Proposed Rule deviates from the accepted definitions for “policy determining,” “policy advocating,” and “policy influencing” roles identified in the Civil Service Act of 1978, and assigned to political appointees and excepted service employment categories. If the proposed rule were limited to “policy determining” and “policy making”, most of these positions would already be part of the Senior Executive Service (SES). These federal employment Schedules already carry the requisite responsiveness and accountability to Administration policies and priorities needed to ensure alignment of federal programs with legislative and executive branch intent.

- Newly designating “Policy-influencing” positions as Schedule P/C provides such a breadth of interpretation for federal agencies that it could encompass most federal jobs, which currently rely on a non-partisan, merit based civil service and their associated civil service protections. Already, a Social Security Administration (SSA) leader has voiced the intent to designate nearly all SSA career employees as Schedule P/C. Furthermore, the lack of guidance to agencies in identifying “policy influencing” roles will create inconsistencies in its application across agencies and confusion in comparing similar occupations and their duties.

Launch the Next Nuclear Corps for a More Flexible Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), the Nation’s regulator of civilian nuclear technologies, should shift agency staff, resources, and operations more flexibly based on emergent regulatory demands. The nuclear power industry is demonstrating commercialization progress on new reactor concepts that will challenge the NRC’s licensing and oversight functions. Rulemaking on new licensing frameworks is in progress, but such regulation will fall short without changes to the NRC’s staffing. Since the NRC is exempt from civil service laws under the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) of 1954, the agency should use AEA flexible hiring authorities to launch the Next Nuclear Corps, a staffing program to shift capacity based on emergent, short-term workforce needs. The NRC should also better enable hiring managers to meet medium-term workforce needs by clarifying guidance on NRC’s direct hire authority.

Challenge and Opportunity

Policymakers, investors, and major energy users, such as data centers and industrial plants, are interested in new nuclear power because it promises unique value. New nuclear power technologies could add either additional base load or variable power to electrical systems. Small modular or micro reactors could provide independent power to military bases, many of which are connected to power grids and vulnerable to disruption. Local governments can stimulate economies with high-paying and safe jobs at nuclear plants. The average nuclear power plant also has the lowest lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions compared to other available electricity-generating technologies, including wind, solar, and hydropower. Current efforts to expand nuclear power are different from those of the 1970s and 1980s, the most recent decades of significant building. Proposals today include building plants designed similarly to plants of those decades or even restarting power operations at up to three closed plants; but more activity is focused on commercializing advanced and small modular reactors, diverse concepts incorporating innovations in reactor design, fuel types, and safety systems. The government has partnered with private companies to develop and demonstrate advanced reactors since the inception of nuclear technology in the 1950s, but today several companies demonstrate advanced technical and business progress toward commercialization.

Innovation in nuclear power challenges the NRC’s status-quo approaches to licensing and oversight. Rulemaking on new regulatory frameworks is necessary and in progress, but changes to the agency’s staffing and operations are also needed. Over time, Congress, the President, and the Commission itself have adjusted the agency’s operations in response to shifts in international postures, comprehensive national energy plans, and accidents or emerging threats at nuclear plants, but the NRC’s ability to respond to sudden changes in the nuclear industry is a long-standing challenge. To become more flexible, NRC initiated Project Aim in 2014 after expectations of significant industry growth, spurred in part by tax incentives in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, were not realized due to record-low natural gas prices. More recent assessments from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and NRC Office of Inspector General (OIG) acknowledge the challenge of workload forecasting in an unpredictable nuclear industry, but counterintuitively, some recommendations focus on improving the ability to workforce plan two years or more in advance. Renewed expectations of growth, spurred by interest from policymakers and energy customers, reinforces a point from the 2015 Project Aim final report that, “…effectiveness, efficiency, agility, flexibility, and performance must improve for the agency to continue to succeed in the future.”

Congress also called on the NRC to become more responsive to current developments as expressed in legislation enacted with bipartisan support. Across the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 and the ADVANCE Act of 2024, Congress requires the NRC to update its mission statement to better reflect the benefits of civilian nuclear technology, establish regulatory frameworks for new technology, streamline environmental review, incentivize licensing of advanced nuclear technologies, and position itself and the United States as a leader in civilian nuclear power. Meeting expectations requires significant operational and workforce changes. Since NRC is exempt from civil service laws and operates an independent competitive merit system, widespread changes to the agency’s hiring practices will be determined by future Commissioners, including the President’s selection of Chair (and by extension, the Chair’s selection of the Executive Director for Operations (EDO)), and modifications to agreements between the NRC and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). In the meantime, NRC is well equipped to increase hiring flexibility using authorities from existing law and regulations.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. The NRC EDO should launch the Next Nuclear Corps, a staffing program dedicated to shifting agency capacity based on short-term workforce needs.

The EDO should hire a new director to lead the Corps. The Corps director should report to the EDO and consult with the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO) and division heads to develop Corps positions to address near-term priorities in competency areas that do not require in-depth training. Near-term priorities should be informed by the NRC’s existing yearly capacity assessments, but the Corps director should also rely on direct expertise and insights from branch chiefs who have a real-time understanding of industry activity and staffing challenges.

Recommendation 2. Hiring for the Corps should be executed under the special authority to appoint directly to the excepted service under 161B(a) of the Atomic Energy Act (AEA).

The ADVANCE Act of 2024 created new categories of hires to fill critical needs related to licensing, oversight, and matters related to NRC efficiency. The EDO should execute the Corps under the new authorities in section 161B(a) of the AEA as it provides clear direction and structure for the EDO to make personnel appointments outside of the NRC’s independent competitive merit system described in Management Directive 10.1. 161B(a)(A) provides up to 210 hires at any time and 161B(a)(B) provides up to 20 additional hires each fiscal year which are limited to a term of four years. The standard service term should be one year as near-term workforce needs may be temporary because of the nature of the position or uncertainty in future demand.

The EDO should adopt the following practices to allow renewals of some positions from the prior year without reaching the limits described in the AEA:

- 161B(a)(A): Appoint up to 140 new staff each fiscal year and consider staggering appointments to address capacity needs that arise later in the year. After the initial one-year term, up to half of the positions should be eligible for a one-year renewal if the need continues. After the initial cohort off-boards, an additional 140 new staff should be appointed alongside up to 70 renewed staff from the prior cohort without exceeding the maximum of 210 appointments at any time.

- 161B(a)(B): Appoint up to 20 new staff each fiscal year and consider staggering appointments to address capacity needs that arise later in the year. All positions should be eligible for a one-year renewal for up to three additional years if the need continues.

Recommendation 3. The EDO should update Management Directives 10.13 and 10.1 to contain or reference the standard operating procedure for NRC’s mirrored version of OPM’s Direct Hire Authority.

The proposed Corps addresses emergent, short-term capacity needs, but internal policy clarity is needed to solve medium-term hiring challenges for hard-to-recruit positions. As far back as 2007, NRC hiring managers and human resources reported that DHA was highly desired for hiring flexibility. The NRC OIG closed Recommendation 2.1 from Audit of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Vacancy Announcement Process in June 2024 because NRC updated Standard Operating Procedure for Direct Hire Authority with more details. However, management directives are the primary policy and procedure documents that govern the NRC’s internal functions. The EDO should update management directives to formally capture or reference this procedure so that NRC staff are better equipped to use DHA. Specifically, the EDO should:

- amend Management Directive 10.13 Special Employment Programs to add Section IX. Direct Hire Authority, that formalizes the procedure in the Standard Operating Procedure for Direct Hire Authority

- update Management Directive 10.1, Section I.A. to reference the amended Management Directive 10.13 as the general policy for non-competitive hiring

Conclusion

The potential of new nuclear power plants to meet energy demand, increase energy security, and revitalize local economies depends on new regulatory and operational approaches at the NRC. Rulemaking on new licensing frameworks is in progress, but the NRC should also use AEA flexible hiring authorities to address emergent, short-term workforce needs that may be temporary based on shifting industry developments. The proposed Corps structure allows the EDO to quickly hire new staff outside of the agency’s competitive merit system for short-term needs while preserving flexibility to renew appointments if the capacity needs continue. For permanent hard-to-recruit positions, the EDO should clarify guidance for hiring managers on direct hire authority. The NRC is well equipped with existing authorities to meet emergent regulatory demand and renewed expectations of nuclear power growth.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The Corps director should create positions informed by the expertise and insights from agency leaders who have a real-time understanding of industry activity and present staffing challenges. Positions should cover all career levels and cover competency areas that do not require in-depth internal training or security clearances. The Corps should fill new positions created for special roles in support of other staff or teams, such as special coordinators, specialists, and consultants.

The Corps is not a graduate-level fellowship or leadership development program. The Corps is specifically for short-term, rapid hiring based on emergent capacity needs that may be temporary based on the nature of the need or uncertainty in future demand.

The Corps structure includes flexibility for a limited number of renewals, but it is not intended to recruit for permanent positions. Supervisors and hiring managers could choose to coordinate with the OCHCO to recruit off-boarding Corps members to other employment opportunities.

The Corps director can identify talent through existing NRC recruiting channels, such as job fairs, universities, and professional associations, however, the Corps director should also establish new recruiting efforts through more competitive channels. Because the positions are temporary, the Corps can recruit from more competitive talent pools, such as talent seeking long term careers in private industry. Job seekers with long-term ambitions in the private nuclear sector and the NRC could both benefit from a one- or two-year period of service focused on a specific project.

Establishing a Cyber Workforce Action Plan

The next presidential administration should establish a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan to address the critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals and bolster national security. This plan encompasses innovative educational approaches, including micro-credentials, stackable certifications, digital badges, and more, to create flexible and accessible pathways for individuals at all career stages to acquire and demonstrate cybersecurity competencies.

The initiative will be led by the White House Office of the National Cyber Director (ONCD) in collaboration with key agencies such as the Department of Education (DoE), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), and National Security Agency (NSA). It will prioritize enhancing and expanding existing initiatives—such as the CyberCorps: Scholarship for Service program that recruits and places talent in federal agencies—while also spearheading new engagements with the private sector and its critical infrastructure vulnerabilities. To ensure alignment with industry needs, the Action Plan will foster strong partnerships between government, educational institutions, and the private sector, particularly focusing on real-world learning opportunities.

This Action Plan also emphasizes the importance of diversity and inclusion by actively recruiting individuals from underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, veterans, and neurodivergent individuals, into the cybersecurity workforce. In addition, the plan will promote international cooperation, with programs to facilitate cybersecurity workforce development globally. Together, these efforts aim to close the cybersecurity skills gap, enhance national defense against evolving cyber threats, and position the United States as a global leader in cybersecurity education and workforce development.

Challenge and Opportunity

The United States and its allies face a critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals, in both the public and private sectors. This shortage poses significant risks to our national security and economic competitiveness in an increasingly digital world.

In the federal government, the cybersecurity workforce is aging rapidly, with only about 3% of information technology (IT) specialists under 30 years old. Meanwhile, nearly 15% of the federal cyber workforce is eligible for retirement. This demographic imbalance threatens the government’s ability to defend against sophisticated and evolving cyber threats.

The private sector faces similar challenges. According to recent estimates, there are nearly half a million unfilled cybersecurity positions in the United States. This gap is expected to grow as cyber threats become more complex and pervasive across all industries. Small and medium-sized businesses are particularly vulnerable, often lacking the resources to compete for scarce cyber talent.

The cybersecurity talent shortage extends beyond our borders, affecting our allies as well. As cyber threats from adversarial nation states become increasingly global in nature, our international partners’ ability to defend against these threats directly impacts U.S. national security. Many of our allies, particularly in Eastern Europe and Southeast Asia, lack robust cybersecurity education and training programs, further exacerbating the global skills gap.

A key factor contributing to this shortage is the lack of accessible, flexible pathways into cybersecurity careers. Traditional education and training programs often fail to keep pace with rapidly evolving technology and threat landscapes. Moreover, they frequently overlook the potential of career changers and nontraditional students who could bring valuable diverse perspectives to the field.

However, this challenge presents a unique opportunity to revolutionize cybersecurity education and workforce development. By leveraging innovative approaches such as apprenticeships, micro-credentials, stackable certifications, peer-to-peer learning platforms, digital badges, and competition-based assessments, we can create more agile and responsive training programs. These methods can provide learners with immediately applicable skills while allowing for continuous upskilling as the field evolves.

Furthermore, there’s an opportunity to enhance cybersecurity awareness and basic skills among all American workers, not just those in dedicated cyber roles. As digital technologies permeate every aspect of modern work, a baseline level of cyber hygiene and security consciousness is becoming essential across all sectors.

By addressing these challenges through a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan, we can not only strengthen our national cybersecurity posture but also create new pathways to well-paying, high-demand jobs for Americans from all backgrounds. This initiative has the potential to position the United States as a global leader in cyber workforce development, enhancing both our national security and our economic competitiveness in the digital age.

Evidence of Existing Initiatives

While numerous excellent cybersecurity workforce development initiatives exist, they often operate in isolation, lacking cohesion and coordination. ONCD is positioned to leverage its whole-of-government approach and the groundwork laid by its National Cyber Workforce and Education Strategy (NCWES) to unite these disparate efforts. By bringing together the strengths of various initiatives and their stakeholders, ONCD can transform high-level strategies into concrete, actionable steps. This coordinated approach will maximize the impact of existing resources, reduce duplication of efforts, and create a more robust and adaptable cybersecurity workforce development ecosystem. This proposed Action Plan is the vehicle to turn these collective workforce-minded strategies into tangible, measurable outcomes.

At the foundation of this plan lies the NICE Cybersecurity Workforce Framework, developed by NIST. This common lexicon for cybersecurity work roles and competencies provides the essential structure upon which we can build. The Cyber Workforce Action Plan seeks to expand on this foundation by creating standardized assessments and implementation guidelines that can be adopted across both public and private sectors.

Micro-credentials, stackable certifications, digital badges, and other innovations in accessible education—as demonstrated by programs like SANS Institute’s GIAC certifications and CompTIA’s offerings—form a core component of the proposed plan. These modular, skills-based learning approaches allow for rapid validation of specific competencies—a crucial feature in the fast-evolving cybersecurity landscape. The Action Plan aims to standardize and coordinate these and similar efforts, ensuring widespread recognition and adoption of accessible credentials across industries.

The array of gamification and competition-based learning approaches—including but not limited to National Cyber League, SANS NetWars, and CyberPatriot—are also exemplary starting points that would benefit from greater federal engagement and coordination. By formalizing these methods within education and workforce development programs, the government can harness their power to simulate real-world scenarios and drive engagement at a national scale.

Incorporating lessons learned from the federal government’s previous DoE CTE CyberNet program, the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Scholarship for Service Program (SFS), and the National Security Agency’s (NSA) GenCyber camps—the Action Plan emphasizes the importance of early engagement (the middle grades and early high school years) and practical, hands-on learning experiences. By extending these principles across all levels of education and professional development, we can create a continuous pathway from high school through to advanced career stages.

A Cyber Workforce Action Plan would provide a unifying praxis to standardize competency assessments, create clear pathways for career progression, and adapt to the evolving needs of both the public and private sectors. By building on the successes of existing initiatives and introducing innovative solutions to fill critical gaps in the cybersecurity talent pipeline, we can create a more robust, diverse, and skilled cybersecurity workforce capable of meeting the complex challenges of our digital future.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Create a Cyber Workforce Action Plan.

ONCD will develop and oversee the plan, in close collaboration with DoE, NIST, NSA, and other relevant agencies. The plan has three distinct components:

1. Develop standardized assessments aligned with the NICE framework. ONCD will work with NIST to create a suite of standardized assessments to evaluate cybersecurity competencies that:

- Cover the full range of knowledge, skills, and abilities defined in the NICE framework.

- Include both theoretical knowledge tests and practical, scenario-based evaluations.

- Be regularly updated to reflect evolving cybersecurity threats and technologies.

- Be designed with input from both government and industry cybersecurity professionals to ensure relevance and applicability.

2. Establish a system of stackable and portable micro-credentials. To provide flexible and accessible pathways into cybersecurity careers, ONCD will work with DoE, NIST, and the private sector to help develop and support systems of micro-credentials that are:

- Aligned with specific competencies in the NICE framework: NIST, as the national standards-setting body, will issue these credentials to ensure alignment with the NICE framework. This will provide legitimacy and broad recognition across industries.

- Stackable, allowing learners to build towards larger certifications or degrees: These credentials will be designed to allow individuals to accumulate certifications over time, ultimately leading to more comprehensive qualifications or degrees.

- Portable across different sectors and organizations: The micro-credentials will be recognized by both government agencies and private-sector employers, ensuring they have value regardless of where an individual seeks employment.

- Recognized and valued by both government agencies and private-sector employers: By working closely with the private sector—where credentialing systems like those from CompTIA and Google are already advanced—the ONCD will help ensure government-issued credentials are not duplicative but complementary to existing industry standards. NIST’s involvement, combined with input from private-sector leaders, will provide confidence that these credentials are relevant and accepted in both public and private sectors.

- Designed to facilitate rapid upskilling and reskilling in response to evolving cybersecurity needs: Given the rapidly changing landscape of cybersecurity threats, these micro-credentials will be regularly updated to reflect the most current technologies and skills, enabling professionals to remain agile and competitive.

3. Integrate more closely with more federal initiatives. The Action Plan will be integrated with existing federal cybersecurity programs and initiatives, including:

- DHS’s Cybersecurity Talent Management System

- DoD’s Cyber Excepted Service

- NIST’s NICE framework

- NSF’s CyberCorps SFS program

- NSA’s GenCyber camps

This proposal emphasizes stronger integration with existing federal initiatives and greater collaboration with the private sector. Instead of creating entirely new credentialing standards, ONCD will explore opportunities to leverage widely adopted commercial certifications, such as those from Google, CompTIA, and other private-sector leaders. By selecting and promoting recognized commercial standards where applicable, ONCD can streamline efforts, avoiding duplication and ensuring the cybersecurity workforce development approach is aligned with what is already successful in industry. Where necessary, ONCD will work with NIST and industry professionals to ensure these commercial certifications meet federal needs, creating a more cohesive and efficient approach across both government and industry. This integrated public-private strategy will allow ONCD to offer a clear leadership structure and accountability mechanism while respecting and utilizing commercial technology and standards to address the scale and complexity of the cybersecurity workforce challenge.

The Cyber Workforce Action Plan will emphasize strong collaborations with the private sector, including the establishment of a Federal Cybersecurity Curriculum Advisory Board composed of experts from relevant federal agencies and leading private-sector companies. This board will work directly with universities to develop model curricula that incorporate the latest cybersecurity tools, techniques, and threat landscapes, ensuring that graduates are well-prepared for the specific challenges faced by both federal and private-sector cybersecurity professionals.

To provide hands-on learning opportunities, the Action Plan will include a new National Cyber Internship Program. Managed by the Department of Labor in partnership with DHS’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) and leading technology companies, the program will match students with government agencies and private-sector companies. An online platform will be developed, modeled after successful programs like Hacking for Defense, where industry partners can propose real-world cybersecurity projects for student teams.

To incentivize industry participation, the General Services Administration (GSA) and DoD will update federal procurement guidelines to require companies bidding on cybersecurity-related contracts to certify that they offer internship or early-career opportunities for cybersecurity professionals. Additionally, CISA will launch a “Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence” certification program, which will be a prerequisite for companies bidding on certain cybersecurity-related federal contracts.

The Action Plan will also address the global nature of cybersecurity challenges by incorporating international cooperation elements. This includes adapting the plan for international use in strategically important regions, facilitating joint training programs and professional exchanges with allied nations, and promoting global standardization of cybersecurity education through collaboration with international standards organizations.

Ultimately, this effort intends to implement a national standard for cybersecurity competencies—providing clear, accessible pathways for career progression and enabling more agile and responsive workforce development in this critical field.

Recommendation 2. Implement an enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program.

ONCD should expand the NSF’s CyberCorps Scholarship for Service program as an immediate, high-impact initiative. Key features of the expanded CyberCorps fellowship program include:

1. Comprehensive talent pipeline: While maintaining the current SFS focus on students, the enhanced CyberCorps will also target recent graduates and early-career professionals with 1–5 years of work experience. This expansion addresses immediate workforce needs while continuing to invest in future talent. The program will offer competitive salaries, benefits, and loan forgiveness options to attract top talent from both academic and private-sector backgrounds.

2. Multiagency exposure and optional rotations: While cross-sector exposure remains valuable for building a holistic understanding of cybersecurity challenges, the rotational model will be optional or limited based on specific agency needs. Fellows may be offered the opportunity to rotate between agencies or sectors only if their skill set and the hosting agency’s environment are conducive to short-term placements. For fellows placed in agencies or sectors where longer ramp-up times are expected, a deeper, longer-term placement may be more effective. Drawing on lessons from the Presidential Innovation Fellows and the U.S. Digital Corps, the program will emphasize flexibility to ensure that fellows can make meaningful contributions within the time frame and that knowledge transfer between sectors remains a core objective.

3. Advanced mentorship and leadership development: Building on the SFS model, the expanded program will foster a strong community of cyber professionals through cohort activities and mentorship pairings with senior leaders across government and industry. A new emphasis on leadership training will prepare fellows for senior roles in government cybersecurity.

4. Focus on emerging technologies: Complementing the SFS program’s core cybersecurity curriculum, the expanded CyberCorps will emphasize cutting-edge areas such as artificial intelligence in cybersecurity, quantum computing, and advanced threat detection. This focus will prepare fellows to address future cybersecurity challenges.

5. Extended impact through education and mentorship: The program will encourage fellows to become cybersecurity educators and mentors in their communities after their service, extending the program’s impact beyond government service and strengthening America’s overall cyber workforce.

By implementing these enhancements to the CyberCorps program as a first step and quick win, the Action Plan will initiate a more comprehensive approach to federal cybersecurity workforce development. The enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program will also emphasize diversity and inclusion to address the critical shortage of cybersecurity professionals and bring fresh perspectives to cyber challenges. The program will actively recruit individuals from underrepresented groups, including women, people of color, veterans, and neurodivergent individuals.

To achieve this, the program will partner with organizations like Girls Who Code and the Hispanic IT Executive Council to promote cybersecurity careers and expand the applicant pool. The Department of Labor, in conjunction with the NSF, will establish a Cyber Opportunity Fund to provide additional scholarships and grants for individuals from underrepresented groups pursuing cybersecurity education through the CyberCorps program.

In addition, the program will develop standardized apprenticeship components that provide on-the-job training and clear pathways to full-time employment, with a focus on recruiting from diverse industries and backgrounds. Furthermore, partnerships with Historically Black Colleges and Universities, Hispanic-Serving Institutions, and Tribal Colleges and Universities will be strengthened to enhance their cybersecurity programs and create a pipeline of diverse talent for the CyberCorps program.

The CyberCorps program will expand its scope to include an international component, allowing for exchanges with allied nations’ cybersecurity agencies and bringing international students to U.S. universities for advanced studies. This will help position the United States as a global leader in cybersecurity education and training while fostering a worldwide community of professionals capable of responding effectively to evolving cyber threats.

By incorporating these elements, the enhanced CyberCorps fellowship program will not only address immediate federal cybersecurity needs but also contribute to building a diverse, skilled, and globally aware cybersecurity workforce for the future.

Implementation Considerations

To successfully establish and execute the comprehensive Action Plan and its associated initiatives, careful planning and coordination across multiple agencies and stakeholders will be essential. Below are some of the key timeline and funding considerations the ONCD should factor into its implementation.

Key milestones and actions for the first two years

Months 1–6:

- Create the Cyber Workforce Action Plan as a roadmap to implementing ONCD’s NCWES.

- Form interagency working group and private-sector advisory board.

- NIST’s Information Technology Laboratory, in collaboration with industry partners, will begin the development of the standardized assessment system and micro-credentials framework.

- Initiate the Federal Cybersecurity Curriculum Advisory Board.

- Launch the expanded CyberCorps fellowship program recruitment.

Months 7–12:

- Implement pilot programs for standardized assessments and micro-credentials.

- Begin first cohort of expanded CyberCorps fellows.

- Launch diversity and inclusion initiatives, including the “Cyber for All” awareness campaign.

- Initiate the National Cybersecurity Internship Program.

- Begin development of the Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence recognition program.

Months 13–18:

- Pilot standardized assessments and micro-credentials system in select agencies and educational institutions, with full rollout anticipated after evaluation and adjustments based on feedback.

- Expand CyberCorps program and university partnerships.

- Implement private-sector internship and project-based learning programs.

- Launch the International Cybersecurity Workforce Alliance.

Months 19–24:

- Implement tax incentives for industry participation in workforce development.

- Establish the Cybersecurity Development Fund for international capacity building.

- Conduct first annual review of diversity and inclusion metrics in federal cyber workforce.

Program evaluation and quality assurance

Beyond these key milestones, the Action Plan must establish clear evaluation frameworks to ensure program quality and effectiveness, particularly for integrating non-federal education programs into federal hiring pathways. For example, to address OPM’s need for evaluating non-federal technical and career education programs under the Recent Graduates Program, the Action Plan will implement the following evaluation framework:

- Alignment with NICE framework competencies (minimum 80% coverage of core competencies)

- Completion of NIST-approved standardized technical assessments

- Documentation of supervised practical experience (minimum 400 hours)

- Evidence of quality assurance processes comparable to registered apprenticeship programs

- Regular curriculum updates (minimum annually) to reflect current security threats

- Industry partnership validation through the Cybersecurity Employer of Excellence program

The implementation of these criteria will be overseen by the same advisory board established in Months 1-6, expanding their scope to include program evaluation and certification. This approach leverages existing governance structures while providing OPM with quantifiable metrics to evaluate non-federal program graduates.

Budgetary, resource, and personnel needs

The estimated annual budget for the proposed initiative ranges from $125 million to $200 million. This range considers cost-effective resource allocation strategies, including the integration of existing platforms and focused partnerships. Key components of the program include:

- Staffing: A core team of 15–20 full-time employees will oversee the centralized program office, focusing on high-level coordination and oversight. Specialized tasks such as curriculum development and assessment design will be contracted to external partners, reducing the need for a larger in-house team.

- IT infrastructure: Rather than building new systems from scratch, the initiative will use existing platforms and credentialing technologies from private-sector providers (e.g., CompTIA, Coursera). This significantly reduces upfront development costs while ensuring a robust system for managing assessments and credentials.

- Marketing and outreach: A smaller but targeted budget will be allocated for domestic and international outreach to raise awareness of the program. Partnerships with industry and educational institutions will help amplify these efforts, reducing the need for a large marketing budget.

- Grants and partnerships: The program will provide modest grants to universities to support curriculum development, with a focus on fostering partnerships rather than large-scale financial commitments. This allows for more cost-effective collaboration with educational institutions.

- Fellowship programs and international exchanges: The expanded CyberCorps fellowship will begin with a smaller cohort, scaling up based on available funding and demonstrated success. International exchanges will be limited to strategic, high-impact partnerships to ensure cost efficiency while still addressing global cybersecurity needs.

Potential funding sources

Funding for this initiative can be sourced through a variety of channels. First, congressional appropriations via the annual budget process are expected to provide a significant portion of the financial support. Additionally, reallocating existing funds from cybersecurity and workforce development programs could account for approximately 25–35% of the overall budget. This reallocation could include funding from current programs like NICE, SFS, and other workforce development grants, which can be repurposed to support this broader initiative without requiring entirely new appropriations.

Public-private partnerships will also be explored, with potential contributions from industry players who recognize the value of a robust cybersecurity workforce. Grants from federal entities such as DHS, DoD, and NSF are viable options to supplement the program’s financial needs. To offset costs, fees collected from credentialing and training programs could serve as an additional revenue stream.

Finally, the Action Plan and its initiatives will seek contributions from international development funds aimed at capacity-building, as well as financial support from allied nations to aid in the establishment of joint international programs.

Conclusion

Establishing a comprehensive Cyber Workforce Action Plan represents a pivotal move toward securing America’s digital future. By creating flexible, accessible career pathways into cybersecurity, fostering innovative education and training models, and promoting both domestic diversity and international cooperation, this initiative addresses the urgent need for a skilled and resilient cybersecurity workforce.

The impact of this proposal is wide-ranging. It will not only reinforce national security by strengthening the nation’s cyber defenses but also contribute to economic growth by creating high-paying jobs and advancing U.S. leadership in cybersecurity on the global stage. By expanding access to cybersecurity careers and engaging previously underutilized talent pools, this initiative will ensure the workforce reflects the diversity of the nation and is prepared to meet future cybersecurity challenges.

The next administration must make the implementation of this plan a national priority. As cyber threats grow more complex and sophisticated, the nation’s ability to defend itself depends on developing a robust, adaptable, and highly skilled cybersecurity workforce. Acting swiftly to establish this strategy will build a stronger, more resilient digital infrastructure, ensuring both national security and economic prosperity in the 21st century. We urge the administration to allocate the necessary resources and lead the transformation of cybersecurity workforce development. Our digital future—and our national security—demand immediate action.

Retiring Baby Boomers Can Turn Workers into Owners: Securing American Business Ownership through Employee Ownership

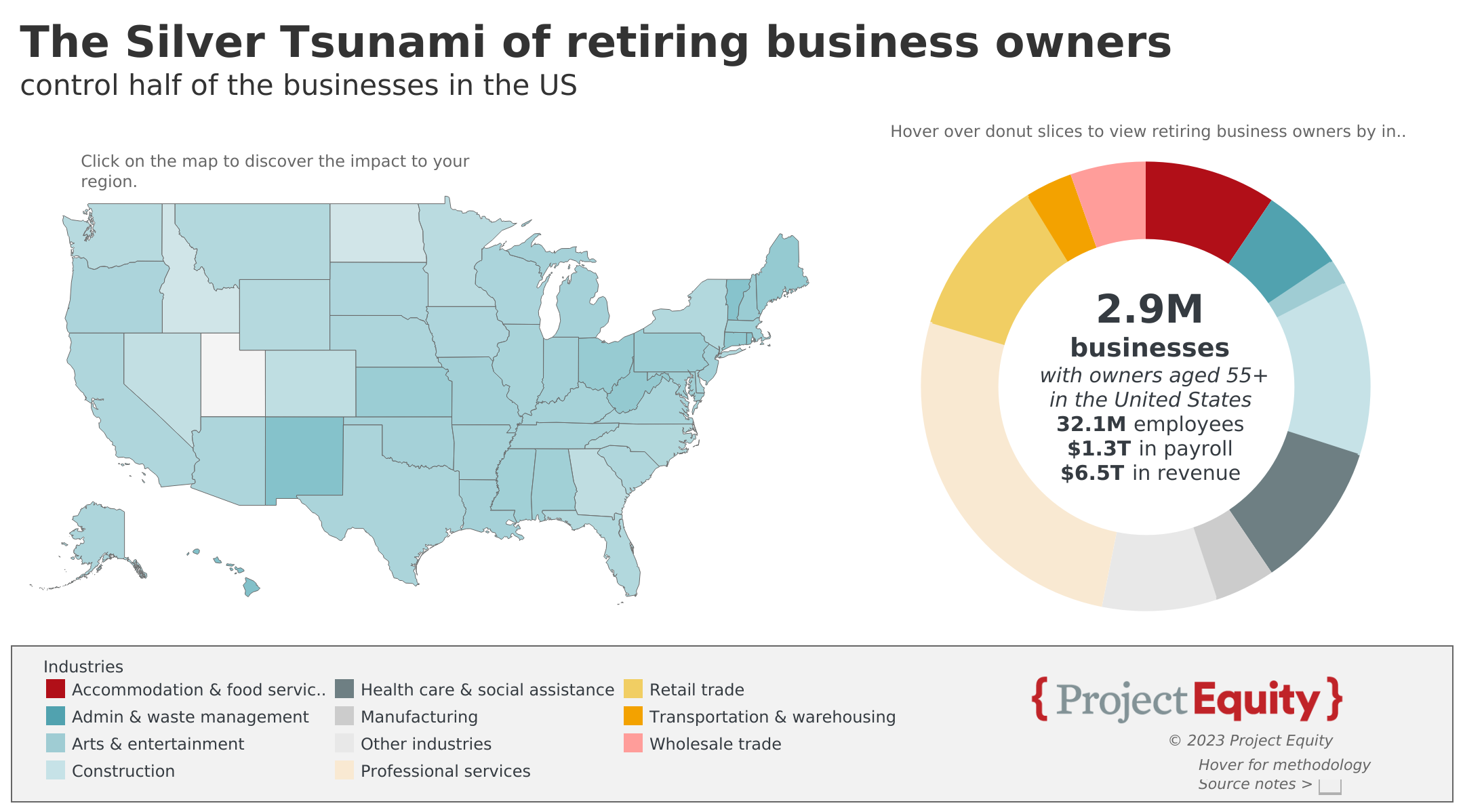

The economic vitality and competitiveness of America’s economy is in jeopardy. The Silver Tsunami of retiring business owners puts half of small businesses at risk: 2.9 million companies are owned by someone at or near retirement age, of which 375,000 are manufacturing, trade, and distribution businesses critical to our supply chains. Add to this that 40 percent of U.S. corporate stock is owned by foreign investors, which funnels these companies’ profits out of our country, weakening our ability to reinvest in our own competitiveness. If the steps to expand the availability of employee ownership were to address even just 10% of the Silver Tsunami companies over 10 employees, this would preserve an estimated 57K small businesses and 2.6M jobs, affecting communities across the U.S. Six hundred billion dollars in economic activity by American-owned firms would be preserved, ensuring that these firms’ profits continue to flow into American pockets.

Broad-based employee ownership (EO) is a powerful solution that preserves local American business ownership, protects our supply chains and the resiliency of American manufacturing, creates quality jobs, and grows the household balance sheets of American workers and their families. Expanding access to financing for EO is crucial at this juncture, given the looming economic threats of the Silver Tsunami and foreign business ownership.

Two important opportunities expand capital access to finance sales of businesses into EO, building on over 50 years of federal support for EO and over 65 years of supporting the flow of small business private capital to where it is not in adequate supply: first, the Employee Equity Investment Act (EEIA), and second, addressing barriers in the SBA 7(a) loan guarantee program.

Three trends create tremendous urgency to leverage employee ownership small business acquisition: (1) the Silver Tsunami, representing $6.5T in GDP and one in five private sector workers nationwide, (2) fewer than 30 percent of businesses are being taken over by family members, and (3) only one in five businesses put up for sale is able to find a buyer.

Without preserving Silver Tsunami businesses, the current 40 percent share of foreign ownership will only grow. Supporting U.S. private investors in the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) space to proactively pitch EO to business owners, and come with readily available financing, enables EO to compete with other acquisition offers, including foreign firms.

In communities all across the U.S., from urban to suburban to rural (where arguably the need to find buyers and the impact of job losses can be most acute), EO is needed to preserve these businesses and their jobs in our communities, maintain U.S. stock ownership, preserve manufacturing production capacity and competitive know how, and create the potential for the next generation of business owners to create economic opportunity for themselves and their families.

Challenge and Opportunity

Broad-based employee ownership (EO) of American small businesses is one of the most promising opportunities to preserve American ownership and small business resiliency and vitality, and help address our country’s enormous wealth gap. EO creates the opportunity to have a stake in the game, and to understand what it means to be a part owner of a business for today’s small business workforces.

However, the growth of EO, and its ability to preserve American ownership of small businesses in our local economies, is severely hampered by access to financing.

Most EO transactions (which are market rate sales) require the business owner to first learn about EO, then to not only initiate the transaction (typically hiring a consultant to structure the deal for them), but also to finance as much as 50 percent or more of the sale. This contrasts to how the M&A market traditionally works: buyers who provide the financing are the ones who initiate the transaction with business owners. This difference is a core reason why EO hasn’t grown as quickly as it could, given all of the backing provided through federal tax breaks dating back to 1974.

More than one form of EO is needed to address the urgent Silver Tsunami and related challenges, including Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) which are only a fit for companies of about 40 employees and above, and worker-owned cooperatives and Employee Ownership Trusts (EOTs), which are a fit for companies of about 10 employees and above (below 10 is a challenge for any EO transition). Of small businesses with greater than 10 employees, those with 10-19 employees make up 51% of the total; those with 20-49 employees make up 33%. In other words, the vast majority of companies with over 10 employees (the minimum size threshold for EO transitions) are below the 40+ employee threshold required for an ESOP. This underscores the importance of ensuring financing access for worker coops and EOTs that can support transitions of companies in the 10-40 employee range.

Without action, we are at risk of losing the small businesses and jobs that are in need of buyers as a result of the Silver Tsunami.

Across the entire small business economy, 2.9M businesses that provide 32.1M jobs are estimated to be at risk, representing $1.3T in payroll and $6.5T in business revenue. Honing in on only manufacturing, wholesale trade and transportation & warehousing businesses, there are an estimated 375,000 businesses at risk that provide 5.5M jobs combined, representing $279.2B of payroll and $2.3T of business revenue.

Plan of Action

Two important opportunities will expand capital access to finance sales of businesses into EO and solve the supply-demand imbalance created in the small business merger and acquisition marketplace with too many businesses needing buyers and being at risk of closing down due to the Silver Tsunami.

First, passing new legislation, the Employee Equity Investment Act (EEIA), would establish a zero-subsidy credit facility at the Small Business Administration, enabling Congress to preserve the legacy of local businesses and create quality jobs with retirement security by helping businesses transition to employee ownership. By supporting private investment funds, referred to as Employee Equity Investment Companies (EEICs), Congress can support the private market to finance the sale of privately-held small- and medium-sized businesses from business owners to their employees through credit enhancement capabilities at zero subsidy cost to the taxpayer.

EEICs are private investment companies licensed by the Small Business Administration that can be eligible for low-cost, government-backed capital to either create or grow employee-owned businesses. In the case of new EO transitions, the legislation intends to “crowd in” private institutional capital sources to reduce the need for sellers to self-finance a sale to employees. Fees paid into the program by the licensed funds enable it to operate at a zero-subsidy cost to the federal government.

The Employee Equity Investment Act (EEIA) helps private investors that specialize in EO to compete in the mergers & acquisition (M&A) space.

Second, addressing barriers to EO lending in the SBA 7(a) loan guarantee program by passing legislation that removes the personal guarantee requirement for worker coops and EOTs would help level the playing field, enabling companies transitioning to EO to qualify for this loan guarantee without requiring a single employee-owner to personally guarantee the loan on behalf of the entire owner group of 10, 50 or 500 employees.

Importantly, our manufacturing supply chain depends on a network of tier 1, 2 and 3 suppliers across the entire value chain, a mix of very large and very small companies (over 75% of manufacturing suppliers have 20 or fewer employees). The entire sector faces an increasingly fragile supply chain and growing workforce shortages, while also being faced with the Silver Tsunami risk. Ensuring that EO transitions can help us preserve the full range of suppliers, distributors and other key businesses will depend on having capital that can finance companies of all sizes. The SBA 7(a) program can guarantee loans of up to $5M, on the smaller end of the small business company size.

Even though the SBA took steps in 2023 to make loans to ESOPs easier than under prior rules, the biggest addressable market for EO loans that fit within the SBA’s 7(a) loan size range are for worker coops and EOTs (because ESOPs are only a fit for companies with about 40 employees or fewer, given higher regulatory costs). Worker coops and EOTs are currently not able to utilize this SBA product.

The legislative action needed is to require the SBA to remove the requirement for a personal guarantee under the SBA 7(a) loan guarantee program for acquisitions financing for worker cooperatives and Employee Ownership Trusts. The Capital for Cooperatives Act (introduced to both the House and the Senate most recently in May 2021) provides a strong starting point for the legislative changes needed. There is precedent for this change; the Paycheck Protection Program loans and SBA Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL) were made during the pandemic to cooperatives without requiring personal guarantees as well as the aforementioned May 2023 rule change allowing majority ESOPs to borrow without personal guarantee.

There is not any expected additional cost to this program outside of some small updates to policies and public communication about the changes.

Addressing barriers to EO lending in the SBA 7(a) loan guarantee program would open up bank financing to the full addressable market of EO transactions.

The Silver Tsunami of retiring business owners puts half of all employer-businesses urgently at risk if these business owners can’t find buyers, as the last of the baby boomers turns 65 in 2030. Maintaining American small business ownership, with 40% of stock of American companies already owned by foreign stockholders, is also critical. EO preserves domestic productive capacity as an alternative to acquisition by foreign firms, including China, and other strategic competitors, which bolsters supply chain resiliency and U.S. strategic competitiveness. Manufacturing is a strong fit for EO, as it is consistently in the top two sectors for newly formed employee-owned companies, making up 20-25% of all new ESOPs.

Enabling private investors in the M&A space to proactively pitch EO to business owners, and come with readily available financing will help address these urgent needs, preserving small business assets in our communities, while simultaneously creating a new generation of American business owners.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

There are an estimated 7,500+ EO companies in the U.S. today, with nearly 40,000 employee-owners and assets well above $2T. Most are ESOPs (about 6,500), plus about 1,000 worker cooperatives, and under 100 EOTs.

For every 1% of Silver Tsunami companies with more than 10 employees that is able to transition to EO based on these recommendations, an estimated 5.7K firms, $60.7B in sales, 260K jobs, and 12.3B in payroll would be preserved.

Congress and the federal government have demonstrated their support of small business and the EO form of small business in many ways, which this proposed two-pronged legislation builds on, for example:

- Creation of the SBIC program in the SBA in 1958 designed to stimulate the small business segment of the U.S. economy by supplementing “the flow of private equity capital and long-term loan funds which small-business concerns need for the sound financing of their business operations and for their growth, expansion, and modernization, and which are not available in adequate supply [emphasis added]”

- Passage of multiple pieces of federal legislation providing tax benefits to EO companies dating back to 1974

- Passage of the Main Street Employee Ownership Act in 2018, which was passed with the intention of removing barriers to SBA loans or guarantees for EO transitions, including to allow ESOPs and worker coops to qualify for loans under the SBA’s 7(a) program. The law stipulated that the SBA “may” make the changes the law provided, but the regulations SBA initially issued made things harder, not easier. Over the next few years, Representatives Dean Phillips (D-MN) and Nydia Velazquez (D-NY), both on the House Small Business Committee, led an effort to get the SBA to make the most recent changes that benefitted ESOPs but not the other forms of EO.

- Release of the first Job Quality Toolkit by the Commerce Department in July 2021, which explicitly includes EO as one of the job quality strategies

- Passage of the WORK Act (Worker Ownership, Readiness, and Knowledge) in 2023 (incorporated as Section 346 of the SECURE 2.0 Act), which directs the Department of Labor (DOL) to create an Employee Ownership Initiative within the department to coordinate and fund state employee ownership outreach programs and also requires the DOL to set new standards for ESOP appraisals. The program was to be funded at $4 million in fiscal year 2025 (which starts in October 2024), gradually increasing to $16 million by fiscal year 2029, but it has yet to be appropriated.

EO transitions using worker cooperatives have been happening for decades. Over the past ten years, this practice has grown significantly. There is a 30-member network of practitioners that actively support small business transitions utilizing worker coops and EOTs called Workers to Owners. Employee Ownership Trusts are newer in the U.S. (though they are the standard EO form in Europe, with decades of strong track record) and are a rapidly growing form of EO with a growing set of practitioners.

Given the supply ~ demand imbalance of retiring business owners created by the Silver Tsunami (lots of businesses need buyers), as well as the outsized positive benefits of EO, prioritizing this form of business ownership is critical to preserving these business assets in our local and national economies. Capital to finance the transactions is central to ensuring EO’s ability to play this important role.

The SBA 7(a) loan program has been and continues to be, critical to opening up bank (and some CDFI) financing for small businesses writ large by guaranteeing loans up to $5M. In FY23, the SBA guaranteed more than 57,300 7(a) loans worth $27.5 billion.

The SBA 7(a) loan program’s current rules require that all owners with 20% or more ownership of a business provide a personal guarantee for the loan, but absent anyone owning 20%, at least one individual must provide the personal guarantee. The previously mentioned May 2023 rule changes updated this for majority ESOPs.

Just as with the ESOP form of EO, the SBA would be able to consider documented proof of an EO borrower’s ability to repay the loan based on equity, cash flow, and profitability to determine lending criteria.

Research into employee ownership demonstrates that EO companies have faster growth, higher profits, and that they outlast their competitors in business cycle downturns. There is precedent for offering loans without a personal guarantee. First, during COVID, the SBA extended both EIDL (Economic Injury Disaster Loans) and PPP (Paycheck Protection Program) loans to cooperatives without requiring a personal guarantee. Second, the SBA’s May 2023 rule changes allow majority ESOPs to borrow without personal guarantee.

The overlap of the EO transaction value with the $5M ceiling for the 7(a) loan guarantee has the largest overlap with transaction values that are suitable for worker coops and EOTs. This is because ESOPs are not viable below about $750K-$1M transaction value due to higher regulatory-related costs, but the other forms of EO are viable down to about 10 or so employees.

A typical bank- or CDFI- financed EO transaction is a senior loan of 50-70% and a seller note of 30-50%. With a $5M ceiling for the 7(a) loan guarantee, this would cap the EO transaction value for 7(a) loans at $10M (a 50% seller note of $5M alongside a $5M bank loan). If a sale price is 4-6x EBITDA (a measure of annual profit) at this transaction value, this would cap the eligible company EBITDA at $1.7-$2.5M, which captures only the lowest company size thresholds that could be viable for the ESOP form.

Supply chain fragility and widespread labor shortages are the two greatest challenges facing American manufacturing operators today, with 75% of manufacturers citing attracting and retaining talent as their primary business challenge, and 65% citing supply chain disruptions as their next greatest challenge. Many don’t realize that the manufacturing sector is built like a block tower, with the Tier 1 (largest) suppliers to manufacturers at the top, Tier 2 suppliers at the next level down, and the widest foundational layer made up of Tier 3 suppliers. For example, a typical auto manufacturer will rely on 18,000 suppliers across its entire value chain, over 98% of which are small or medium sized businesses. In fact, 75% of manufacturing businesses have fewer than 20 employees. It is critical that we preserve American businesses across the entire value chain, and opening up financing for EO for companies of all sizes is absolutely critical.

The manufacturing sector generates 12% of U.S. GDP (gross domestic product), and if we count the value of the sector’s purchasing, the number goes to nearly one quarter of GDP. The sector also employs nearly one in ten American workers (over 14 million). Manufacturing plays a vital role in both our national security and in public health. Finally, the sector has long been a source of quality jobs and a cornerstone of middle class employment.

Though we aren’t certain the reasoning, it is most likely because ESOPs have the largest lobbying presence. Given the broad support by the federal government of ESOPs through a myriad of tax benefits designed to encourage companies to transition to ESOPs, it is the biggest form of EO, enabling its lobbying presence. As discussed, their size threshold (based on the costs to comply with the regulatory requirements) put ESOPs out of reach for companies with below $750K – $1M EBITDA (a measure of annual profit), which leaves a large swath of America’s small businesses not supported by the SBA 7(a) loan guarantee when they are transacting an employee ownership succession plan.

Likely, the lack of lobbying presence by parties representing the non-ESOP forms of employee ownership has resulted in the rule change not applying to the other forms of broad-based employee ownership. However, the data (as outlined above) clearly shows that worker cooperatives and EOTs are needed to address the full breadth of Silver Tsunami EO need, given the size overlap of loans that fit the size guidelines of the 7(a) loan guarantee and the fit with the form of EO. As such, legislators that are focused on American business resiliency and competitiveness are in the good positions to direct the SBA to mirror the ESOP personal loan guarantee treatment for worker cooperatives and EOTs.

Work-based Learning for All: Aligning K-12 Education and the Workplace for both Students and Teachers

The incoming presidential administration of 2025 should champion a policy position calling for strengthening of the connection between K-12 schools and community workplaces. Such connections result in a number of benefits including modernized curricula, more meaningful lessons, more motivated students, more college and career readiness, more qualified applicants for local jobs, more vibrant communities, and a stronger nation. The gains associated with education-workplace partnerships are certainly not exclusive to STEM disciplines of study but given the high-demand for talent in STEM business and industry, the imperative may be greatest in science and mathematics, and the applied domains of engineering and technology.

The rationale for a policy priority around K-12 and workplace partnerships centers around waning public confidence in the ability of schools to prepare tomorrow’s workforce. A perceived disconnect between what gets taught and what learners need in order to thrive on the job threatens individual livelihoods, family and community stability, and national competitiveness in an ever-more rapidly evolving global economy. Bridges are needed that unite education and workplaces, putting students and their teachers to work beyond the classroom. A new administration should:

- Expand externships for teachers in community workplaces. The best way to help every student to explore and to be inspired about career horizons is to prepare and inspire their teachers to represent to them the opportunities that await. Externships in community workplaces sharpen teachers’ content knowledge and skills and equip them to portray the exciting careers that await students. The existing Research Experiences for Teachers (RET) federal infrastructure can be adapted for supporting externships.