General Cartwright Confirms B61-12 Bomb “Could Be More Useable”

By Hans M. Kristensen

General James Cartwright, the former commander of U.S. Strategic Command and former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, confirmed in an interview with PBS Newshour that the increased accuracy of the new guided B61-12 nuclear bomb could make the weapon “more useable” to the president or national-security making process.

GEN. JAMES CARTWRIGHT (RET.), Former Commander, U.S. Strategic Command: If I can drive down the yield, drive down, therefore, the likelihood of fallout, et cetera, does that make it more usable in the eyes of some — some president or national security decision-making process? And the answer is, it likely could be more usable.

Cartwright’s confirmation follows General Norton Schwartz, the former U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, who in 2014 assessed that the increased accuracy would have implications for how the military thinks about using the B61. “Without a doubt. Improved accuracy and lower yield is a desired military capability. Without a question,” he said.

In an article in 2011 I first described the potential effects the increased accuracy provided by the new guided tail kit and the option to select lower yields in nuclear strike could have for nuclear planning and the perception of how useable nuclear weapons are. I also discuss this in an interview on the PBS Newshour program.

In contrast to the enhanced military capabilities offered by the increased accuracy of the B61-12, and its potential impact on nuclear planning confirmed by generals Cartwright and Schwartz, it is U.S. nuclear policy that nuclear weapons “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities,” as stated in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report.

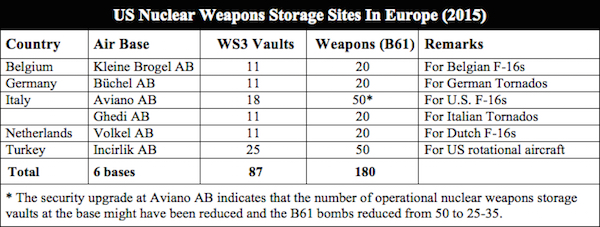

The effect of the B61-12 modernization will be most dramatic in Europe where less accurate older B61s are currently deployed at six bases in five countries for delivery by older aircraft. The first B61-12 is scheduled to roll off the assembly line in 2020 and enter the stockpile in 2024 after which some of the estimated 480 bombs to be built and, under current policy, would be deployed to Europe for deliver by the new F-35A Lightning II fifth-generation fighter-bomber and (for a while) older aircraft.

For background information, see:

- B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

- General Confirms Enhanced Targeting Capabilities of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

- Upgrades At US Nuclear Bases Acknowledge Security Risk

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

LRSO: The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Updated January 26, 2016] In an op-ed in the Washington Post, William Perry and Andy Weber last week called for canceling the Air Force’s new nuclear air-launched cruise missile.

The op-ed challenged what many see as an important component of the modernization of the U.S. nuclear triad of strategic weapons and a central element of U.S. nuclear strategy.

The recommendation to cancel the new cruise missile – known as the LRSO for Long-Range Standoff weapon – is all the more noteworthy because it comes from William Perry, known to some as “ALCM Bill,” who was secretary of defense from 1994 to 1997, and as President Carter’s undersecretary of defense for research and engineering in the late-1970s and early-1980s was in charge of developing the nuclear air-launched cruise missile the LRSO is intended to replace.

And his co-author, Andy Weber, was assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs from 2009 to 2014, during which he served as director of the Nuclear Weapons Council for five-plus years – the very time period the plans to build the LRSO emerged [note: the need to replace the ALCM was decided by DOD during the Bush administration in 2007].

Obviously, Perry and Weber are not impressed by the arguments presented by the Air Force, STRATCOM, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the nuclear laboratories, defense hawks in Congress, and an army or former defense officials and contractors for why the United States should spend $15 billion to $20 billion on a new nuclear cruise missile.

Those arguments seem to have evolved very little since the 1970s. A survey of statements made by defense officials over the past few years for why the LRSO is needed reveals a concoction of justifications ranging from good-old warfighting scenarios of using nuclear weapons to blast holes in enemy air defenses to “the old missile is getting old, therefore we need a new one.”

LRSO: What Is It Good For?

When I wrote about the LRSO in 2013, the Air Force had only said a few things in public about why the weapon was needed. Since then, defense officials have piled on justifications in numerous public statements.

Those statements (see table below) describe an LRSO mission heavily influenced by nuclear warfighting scenarios. This involves deploying nuclear bombers “whenever and wherever we want” with large numbers of LRSOs onboard that “multiplies the number of penetrating targets each bomber presents to an adversary” and “imposes an extremely difficult, multi-azimuth air defense problem on our potential adversaries.” By providing “flexible and effective stand-off capabilities in the most challenging area denial environments” to “effectively conduct global strike operations” at will, the LRSO “maximally expands the accessible space of targets that can be held at risk,” including shooting “holes and gaps [in enemy air defenses] to allow a penetrating bomber to get in” to be able to “do direct attacks anywhere on the planet to hold any place at risk” whether it be in “limited or large scale” nuclear strike scenarios.

It seems clear from many of these statements that the LRSO is not merely a retaliatory capability but very much seen as an offensive nuclear strike weapon that is intended for use in the early phases of a conflict even before long-range ballistic missiles are used. In a briefing from 2014, Major General Garrett Harencak, until September this year the assistant chief of staff for Air Force strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, described a “nuclear use” phase before actual nuclear war during which bombers would use nuclear weapons against regional and near-peer adversaries (see image below).

This Air Force slide from 2014 shows “nuclear use” from bombers in a pre-“nuclear war” phase of a conflict. This apparently could include LRSO strikes against air-defense systems.

Although the LRSO is normally presented as a strategic weapon, the public descriptions by U.S. officials of limited regional scenarios sound very much like a tactical nuclear weapon to be used in a general military campaign alongside conventional weapons. “I can make holes and gaps” in air defenses, Air Force Global Strike commander Lieutenant General Stephen Wilson explained in 2014, “to allow a penetrating bomber to get in.” Indeed, an Air Force briefing slide from 2011 shows the LRSO launched from a next-generation bomber against air defenses to allow a next-generation penetrator launched from the same bomber to attack an underground target (see image below).

This Air Force briefing slide from 2011 shows the LRSO used against air-defense systems, similar to scenarios described by Air Force officials in 2014.

Use of bombers with LRSO in a pre-nuclear war phase is part of an increasing focus on regional nuclear strike scenarios. “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts,” according to Robert Scher, US Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities. “The goal of strengthening regional deterrence cuts across both the strategic stability and extended deterrence and assurance missions to which our nuclear forces contribute.” The efforts include development of “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

The Pentagon appears to be using the Obama administration’s nuclear weapons employment policy to enhance strike options and plans in these regional scenarios. “The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, told the Senate last year. And “continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.” (Emphasis added.)

Cruise Missile Dilemma: Nuclear Versus Conventional

The arguments used to justify the LRSO sound like the United States has little else with which to hold targets at risk. But bomber standoff and targeting capabilities today are vastly superior to those of the late-1970s and early-1980s when the ALCM was developed. Not only are non-nuclear cruise missiles proliferating in numbers and deliver platforms, the Air Force itself seems to prefer them over nuclear cruise missiles.

The Air Force plan to buy 1,000-1,100 LRSOs represents a significant increase of more than 40 percent over the current inventory of 575 ALCMs. Armed with the W80-4 warhead, the LRSO will not only be integrated onto the B-52H that currently carries the ALCM, but also onto the B-2A and the next-generation bomber (LRS-B).

Assuming the LRSO force will have the same number of warheads (approximately 528) as the current ALCM force, the roughly 180 missiles that would be lost in flight tests over a 30-year lifespan does not explain what the remaining 300-400 missiles would be used for.

Air Force Global Strike Command appears to hint that the extra missiles might be used for a conventional LRSO. “We fully intend to develop a conventional version of the LRSO as a future spiral to the nuclear variant.” Yet a lot of other conventional cruise missiles and standoff weapons are already in development – some even making their way onto smaller aircraft such as F-16 fighter-bombers – and Congress is unlikely to pay for yet another conventional air-launched cruise missile.

It is a curious dilemma for the Air Force: it needs the LRSO to help justify the long-range bomber program, but it prefers to spend its money on conventional standoff weapons that are much more flexible and – in contras to the LRSO – can actually be used. The trend is that new conventional standoff weapons are gradually pushing the nuclear cruise missiles off the bombers. To reduce the nuclear load-out under the New START Treaty and prioritize conventional weapons, the Air Force is currently converting stripping the B-52H of its excess capability to carry the ALCM internally in the bomb bay. a total of 44 sets of Common Strategic Rotary Launchers (CSRLs) are being modified to Conventional Rotary Launchers (CRLs). This will give the B-52H the capability to deliver the non-nuclear Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) and its 1,100-kilometer (648 miles) extended range variant JASSM-ER (AGM-158B), weapons that are more useful for deterrent missions than a nuclear cruise missile. Once completed in 2018, each remaining nuclear-capable B-52H will only be capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles externally: 12 missiles under the wings compared with a total of 20 today.

The Air Force is stripping the B-52H of its capability to nuclear air-launched cruise missiles in its bomb bay. By 2018, each B-52H will only be able to carry 12 ALCMs, down from 20 today. Instead it the bomber will equipping it B-52Hs to carry new conventional cruise missiles in its bomb bay.

While the B-52H will lose the capability to carry nuclear cruise missiles internally, The JASSM in contrast will be integrated for both internal and external carriage. As a result, each B-52H will be equipped to carry up to 20 JASSM, of which as many as 16 can be JASSM-ER. Moreover, while only 46 B-52H will be nuclear-capable, all remaining 76 B-52Hs in the inventory will be back fitted for JASSM. An interim JASSM-ER capability is planned for 2017 – nearly a decade before the LRSO is scheduled to be deployed – providing essentially the same standoff capability (although with less range).

The B-2A Spirit stealth-bomber cannot currently carry ALCMs but the Air Force says but will be fitted to carry the LRSO internally in addition to the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. The B-2A, which is scheduled to fly until the 2050s, is also scheduled to be back-fitted with the JASSM-ER.

The next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) will also be equipped with the LRSO (probably 16 internally) in addition to the B61-12, and probably also the JASSM-ER. Once it begins to enter the force after 2025, the LRS-B will probably replace the B-52H in the nuclear mission on a one-for-one basis.

Approximately 5,000 JASSMs are planned, including more than 2,900 JASSM-ERs. Although the nuclear LRSO has a “significantly” greater range than the JASSM-ER (probably 2,500-3,000 kilometers), the conventional missile will still enable the bomber to attack from well beyond air-defense range against soft, medium, and very hard (not deeply buried) targets.

JASSM-ER has been integrated on the B-1B bomber that recently was incorporated into Air Force Global Strike Command alongside B-2A and B-52H bombers. After it is added to the B-52H and B-2A, the JASSM will also be added to F-15E and F-16 fighter-bombers and possibly also to some navy aircraft. Several European countries have already bought JASSM for their fighter-bombers (Poland and Finland).

Clearly, conventional standoff missiles rather than the LRSO appear to be the priority of the Air Force.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In their op-ed, Perry and Weber describe the justification that was used during the Cold War for developing the existing cruise missile, the ALCM (AGM-86B). “At that time, the United States needed the cruise missile to keep the aging B-52, which is quite vulnerable to enemy air defense systems, in the nuclear mission until the more effective B-2 replaced it. The B-52 could safely launch the long-range cruise missile far from Soviet air defenses. We needed large numbers of air-launched nuclear cruise missiles to be able to overwhelm Soviet air defenses and thus help offset NATO’s conventional-force inferiority in Europe,” they write.

The anti-air defense mission that justified development of a nuclear ALCM during the Cold War is no longer relevant. According to Perry and Weber, “such a posture no longer reflects the reality of today’s U.S. conventional military dominance.”

They are right. All U.S. bombers, as well as many fighter-bombers, are scheduled to be equipped with long-rang conventional cruise missiles that provide sufficient capability against the same air-defense targets that LRSO proponents argue require a standoff nuclear cruise missile on the next-generation bomber.

Canceling the LRSO would be an appropriate way to demonstrate implementation of the Obama administration’s nuclear weapons employment strategy from 2013 that directed the Pentagon to “undertake concrete steps toward reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy” and “conduct deliberate planning for non-nuclear strike options to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options.”

Instead, statements by defense officials reveal a worrisome level of warfighting thinking behind the LRSO mission that risks dragging U.S. nuclear planning back into Cold War thinking about the role of nuclear weapons. Instead of implementing the guidance and use advanced conventional weapons to “make holes and gaps” in air defenses, the LRSO mission appears to entertain ideas about using nuclear weapons against regional and near-peer adversaries in the name of extended deterrence and escalation control before actual nuclear war.

Although bombers armed with nuclear gravity bombs can be used to signal to adversaries in a crisis, loading the aircraft with long-range nuclear cruise missiles that can slip unseen under the radar in a surprise attack is inherently destabilizing. This dilemma is exacerbated by the large upload-capability of the bombers that are not normally on alert with nuclear weapons. Pentagon officials will normally warn that re-alerting nuclear weapons onto launchers in a crisis is dangerous, but in the case of LRSO they seem to relish the option to “provide a rapid and flexible hedge against changes in the strategic environment.”

Perry and Weber’s recommendation to cancel the unnecessary and dangerous LRSO is both wise and bold. The strategic situation has changed fundamentally, conventional capabilities can do most of the mission, and arguments for the LRSO seem to be a mixture of Cold War strategy and general nuclear doctrinal mumbo jumbo. Some people in the Obama administration will certainly listen (as will many that have already left). Others will argue that even if they wanted to cancel LRSO, they have little room to maneuver given a hostile Congress, Russia’s return as an official threat, and China’s military modernization and posturing in the South China Sea.

Moreover, the development of the LRSO and its W80-4 warhead is already well underway and rapidly approaching the point of no return. The decision to replace the ALCM with the LRSO was reaffirmed by the Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, the Airborne Strategic Deterrence Capability Based Assessment, and the Initial Capability Document. The LRSO Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) study is already complete and has been approved by the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC), and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force signed the Draft Capabilities Development Document in February 2014. LRSO was selected by the assistance secretary of the Air Force for acquisition (SAF/AQ) as a pilot program for “Bending the Cost Curve,” a new acquisition initiative to make weapons programs more affordable (although with a cost of $15 billion to $20 billion that curve seems to point pretty much straight up). The critical Milestone A decision is expected in early 2016, and program spending will ramp up in 2017 as full-scale development begins with $1.8 billion programmed through 2020.

Similarly, development of the W80-4 warhead for the LRSO is well underway with $1.9 billion programmed through 2020. Warhead development is in Phase 6.2 with first production unit scheduled for 2025.

If national security and rational defense planning – not institutional turf and inertia – determined the U.S. nuclear weapons modernization program, then the LRSO would be canceled. At least Perry and Weber had the guts to call for it.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Drops Below New START Warhead Limit For The First Time

By Hans M. Kristensen

The number of U.S. strategic warheads counted as “deployed” under the New START Treaty has dropped below the treaty’s limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time since the treaty entered into force in February 2011 – a reduction of 263 warheads over four and a half years.

Russia, by contrast, has increased its deployed warheads and now has more strategic warheads counted as deployed under the treaty than in 2011 – up 111 warheads.

Similarly, while the United States has reduced its number of deployed strategic launchers (missiles and bombers) counted by the treaty by 120, Russia has increased its number of deployed launchers by five in the same period. Yet the United States still has more launchers deployed than allowed by the treaty (by 2018) while Russia has been well below the limit since before the treaty entered into force in 2011.

These two apparently contradictory developments do not mean that the United States is falling behind and Russia is building up. Both countries are expected to adjust their forces to comply with the treaty limits by 2018.

Rather, the differences are due to different histories and structures of the two countries’ strategic nuclear force postures as well as to fluctuations in the number of weapons that are deployed at any given time.

Deployed Warhead Status

The latest warhead count published by the U.S. State Department lists the United States with 1,538 “deployed” strategic warheads – down 60 warheads from March 2015 and 263 warheads from February 2011 when the treaty entered into force.

But because the treaty artificially counts each bomber as one warhead, even though the bombers don’t carry warheads under normal circumstances, the actual number of strategic warheads deployed on U.S. ballistic missiles is around 1,450. The number fluctuates from week to week primarily as ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) move in and out of overhaul.

Russia is listed with 1,648 deployed warheads, up from 1,537 in 2011. Yet because Russian bombers also do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are artificially counted as one warhead per bomber, the actual number of Russian strategic warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles is closer to 1,590 warheads.

Because it has fewer ICBMs than the United States (see below), Russia is prioritizing deployment of multiple warheads on its new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). In contrast, the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carry a single warhead – although the missiles retain the capability to load the warheads back on if necessary. And the next-generation missile (GBSD; Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent) the Air Force plans to deploy a decade from now will also be capable of carry multiple warheads.

Warheads from the last MIRVed U.S. ICBM are moved to storage at Malmstrom AFB in June 2014. The sign “MIRV Off Load” has been altered from “Wide Load” on the original photo. Image: US Air Force.

This illustrates one of the deficiencies of the New START Treaty: it does not limit how many warheads Russia and the United States can keep in storage to load back on the missiles. Nor does it limit how many of the missiles may carry multiple warheads.

And just a reminder: the warheads counted by the New START Treaty are not the total arsenals or stockpiles of the United States and Russia. The total U.S. stockpile contains approximately 4,700 warheads (with another 2,500 retired but still intact warheads awaiting dismantlement. Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,500 warheads (with perhaps 3,000 more retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Deployed Launcher Status

The New START Treaty count lists a total of 762 U.S. deployed strategic launchers (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers), down 23 from March 2015 and a total reduction of 120 launchers since 2011. Another 62 launchers will need to be removed before February 2018.

Four and a half years after the treaty entered into force, the U.S. military is finally starting to reduce operational nuclear launchers. Up till now all the work has been focused on eliminating so-called phantom launchers, that is launchers that were are no longer used in the nuclear mission but still carry some equipment that makes them accountable. But that is about to change.

On September 17, the Air Force announced that it had completed denuclearization of the first of 30 operational B-52H bombers to be stripped of their nuclear equipment. Another 12 non-deployed bombers will also be denuclearized for a total of 42 bombers by early 2017. That will leave approximately 60 B-52H and B-2A bombers accountable under the treaty.

The Air Force is also working on removing Minuteman III ICBMs from 50 silos to reduce the number of deployed ICBMs from 450 to no more than 400. Unfortunately, arms control opponents in the U.S. Congress have forced the Air Force to keep the 50 empted silos “warm” so that missiles can be reloaded if necessary.

Finally, this year the Navy is scheduled to begin inactivating four of the 24 missile tubes on each of its 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The work will be completed in 2017 to reduce the number of deployed sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) to no more than 240, down from 288 missiles today.

Russia is counted with 526 deployed launchers – 236 less than the United States. That’s an addition of 11 launchers since March 2015 and five launchers more than when New START first entered into force in 2011. Russia is already 174 deployed launchers below the treaty’s limit and has been below the limit since before the treaty was signed. So Russia is not required to reduce any more deployed launchers before 2018 – in fact, it could legally increase its arsenal.

Yet Russia is retiring four Soviet-era missiles (SS-18, SS-19, SS-25, and SS-N-18) faster than it is deploying new missiles (SS-27 and SS-N-32) and is likely to reduce its deployed launchers more over the next three years.

Russia is also introducing the new Borei-class SSBN with the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM, but slower than previously anticipated and is unlikely to have eight boats in service by 2018. Two are in service with the Northern Fleet (although one does not appear fully operational yet) and one arrived in the Pacific Fleet last month. The Borei SSBNs will replace the old Delta III SSBNs in the Pacific and later also the Delta IV SSBNs in the Northern Fleet.

Russian Borei- and Delta IV-class SSBNs at the Yagelnaya submarine base on the Kola Peninsula. Click to open full size image.

The latest New START data does not provide a breakdown of the different types of deployed launchers. The United States will provide a breakdown in a few weeks but Russia does not provide any information about its deployed launchers counted under New START (nor does the U.S. Intelligence Community say anything in public about what it sees).

As a result, we can’t see from the latest data how many bombers are counted as deployed. The U.S. number is probably around 88 and the Russian number is probably around 60, although the Russian bomber force has serious operational and technical issues. Both countries are developing new strategic bombers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Four and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011, the United States has reduced its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads below the limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time. The treaty limit enters into effect in February 2018.

Russia has moved in the other direction and increased its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads and launchers since the treaty entered into force in 2011. Not by much, however, and Russia is expected to reduce its deployed strategic warheads as required by the New START Treaty by 2018. Russia is not in a build-up but in a transition from Soviet-era weapons to newer types that causes temporary fluctuations in the warhead count. And Russia is far below the treaty’s limit on deployed strategic launchers.

Yet it is disappointing that Russia has allowed its number of “accountable” deployed strategic warheads to increase during the duration of the treaty. There is no need for this increase and it risks fueling exaggerated news media headlines about a Russian nuclear “build-up.”

Overall, however, the New START reductions are very limited and are taking a long time to implement. Despite souring East-West relations, both countries need to begin to discuss what will replace the treaty after it enters into effect in 2018; it will expire in 2021 unless the two countries agree to extend it for another five years. It is important that the verification regime is not interrupted and failure to agree on significantly lower limits before the next Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2020 will hurt U.S. and Russian status.

Moreover, defining lower limits early rather than later is important now to avoid that nuclear force modernization programs already in full swing in both countries are set higher (and more costly) than what is actually needed for national security.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Upgrades At US Nuclear Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk

Security upgrades underway at U.S. Air Force bases in Europe indicate that nuclear weapons deployed in Europe have been stored under unsafe conditions for more than two decades.

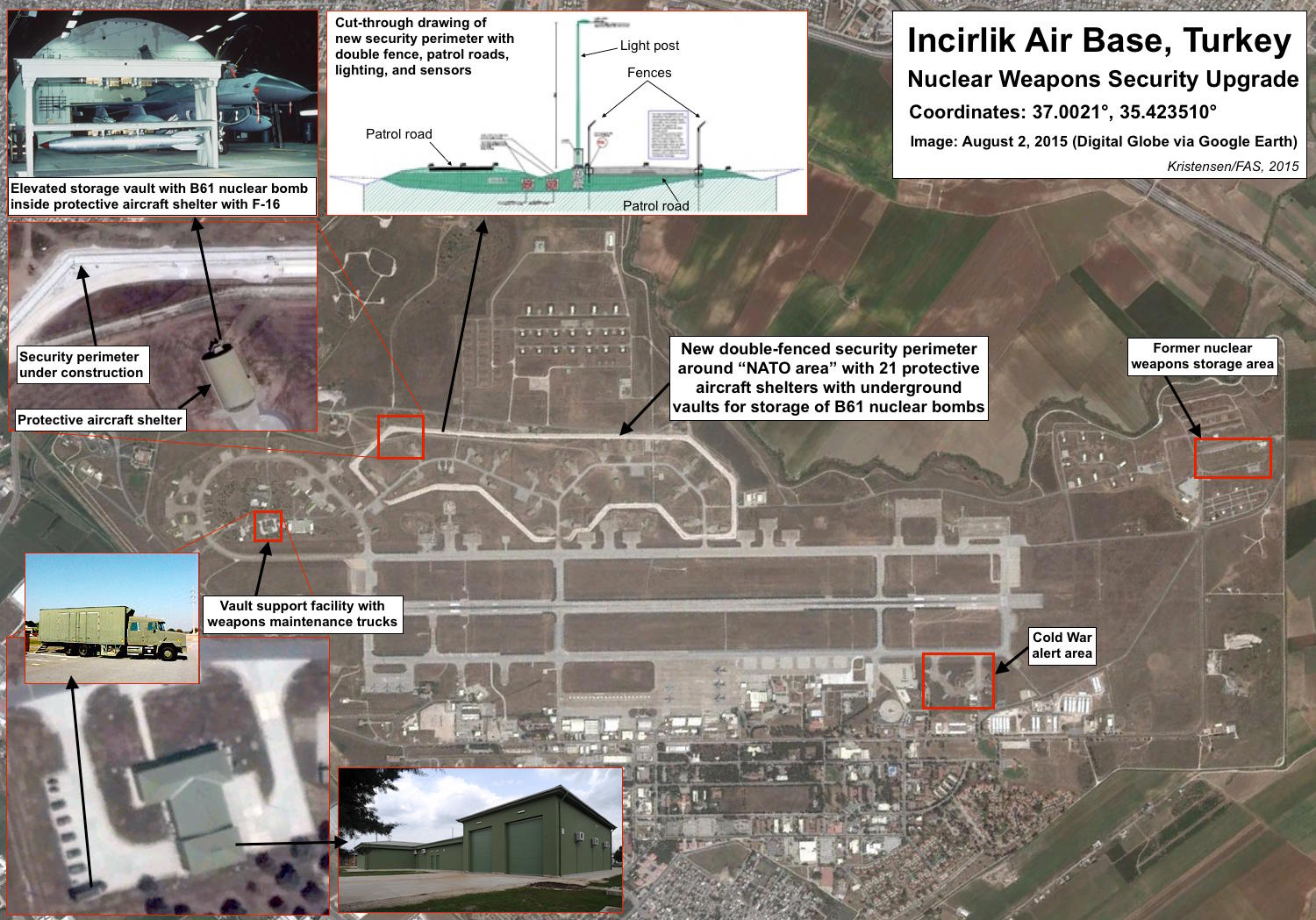

Commercial satellite images show work underway at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey and Aviano Air Base in Italy. The upgrades are intended to increase the physical protection of nuclear weapons stored at the two U.S. Air Force Bases.

The upgrades indirectly acknowledge that security at U.S. nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe has been inadequate for more than two decades.

And the decision to upgrade nuclear security perimeters at the two U.S. bases strongly implies that security at the other four European host bases must now be characterized as inadequate.

Security challenges at Incirlik AB are unique in NATO’s nuclear posture because the base is located only 110 kilometers (68 miles) from war-torn Syria and because of an ongoing armed conflict within Turkey between the Turkish authorities and Kurdish militants. The wisdom of deploying NATO’s largest nuclear weapons stockpile in such a volatile region seems questionable. (UPDATE: Pentagon orders “voluntary departure” of 900 family members of U.S. personnel stationed at Incirlik.)

Upgrades at Incirlik Air Base

Incirlik Air Base is the largest nuclear weapons storage site in Europe with 25 underground vaults installed inside as many protective aircraft shelters (PAS) in 1998. Each vault can hold up to four bombs for a maximum total base capacity of 100 bombs. There were 90 B61 nuclear bombs in 2000, or 3-4 bombs per vault. This included 40 bombs earmarked for deliver by Turkish F-16 jets at Balikesir Air Base and Akinci Air Base. There are currently an estimated 50 bombs at the base, or an average of 2-3 bombs in each of the 21 vaults inside the new security perimeter.

The new security perimeter under construction surrounds the so-called “NATO area” with 21 aircraft shelters (the remaining four vaults might be in shelters inside the Cold War alert area that is no longer used for nuclear operations). The security perimeter is a 4,200-meter (2,600-mile) double-fenced with lighting, cameras, intrusion detection, and a vehicle patrol-road running between the two fences. There are five or six access points including three for aircraft. Construction is done by Kuanta Construction for the Aselsan Cooperation under a contract with the Turkish Ministry of Defense.

A major nuclear weapons security upgrade is underway at the U.S. Air Force base at Incirlik in Turkey.

In addition to the security perimeter, an upgrade is also planned of the vault support facility garage that is used by the special weapons maintenance trucks (WMT) that drive out to service the B61 bombs inside the aircraft shelters. The vault support facility is located outside the west-end of the security perimeter. The weapons maintenance trucks themselves are also being upgraded and replaced with new Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS) trailers.

The nuclear role of Incirlik is unique in NATO’s nuclear posture in that it is the only base in Europe with nuclear weapons that doesn’t have nuclear-capable fighter-bombers permanently present. Even though the Turkish government recently has allowed the U.S. Air Force to fly strikes from Incirlik against targets in Syria, the Turks have declined U.S. requests to permanently base a fighter wing at the base. As such, there is no designated nuclear wing with squadrons of aircraft intended to employ the nuclear bombs stored at Incirlik; in a war, aircraft would have to fly in from wings at other bases to pick up and deliver the weapons.

Upgrades at Aviano Air Base

A nuclear security upgrade is also underway at the U.S. Air Force base near Aviano in northern Italy. Unlike Incirlik, that does not have nuclear-capable aircraft permanently based, Aviano Air Base is home to the 31st Fighter Wing with its two squadrons of nuclear-capable F-16C/Ds: the 510th “Buzzards” Fighter Squadron and the 555th “Triple Nickel” Fighter Squadron. These squadrons have been very busy as part of NATO’s recent response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and some of Aviano’s F-16s are currently operating from Incirlik as part of strike operations in Syria.

A nuclear security upgrade appears to be underway at the U.S. Air Base at Aviano in Italy.

A total of 18 underground nuclear weapons storage vaults were installed in as many protective aircraft shelters at Aviano in 1996 for a maximum total base storage capacity of 72 nuclear bombs. Only 12 of those shelters are inside the new security perimeter under construction at the base. Assuming nuclear weapons will only be stored in vaults inside the new security perimeter in the future, this indicates that the nuclear mission at Aviano may have been reduced.

In 2000, shortly after the original 18 vaults were completed, Aviano stored 50 nuclear bombs, or an average of 2-3 in each vault. The 12 shelters inside the new perimeter (one of which is of a smaller design) would only be able to hold a maximum of 48 weapons if loaded to capacity. If each vault has only 2-3 weapons, it would imply only 25-35 weapons remain at the base.

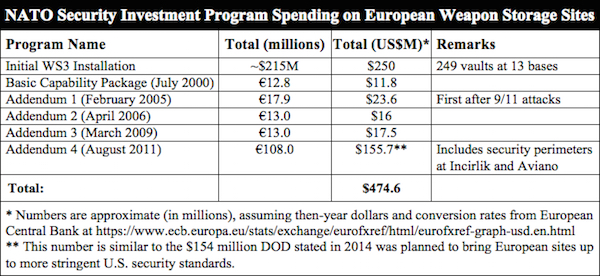

NATO Nuclear Security Costs

Publicly available information about how much money NATO spends on security upgrades to protect the deployment in Europe is sketchy and incomplete. But U.S. officials have provided some data over the past few years.

In November 2011, three years after the U.S. Air Force Ribbon Review Review in 2008 concluded that “most” nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe did not meet U.S. Department of Defense security standards, James Miller, then Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, informed Congress that NATO would spend $63.4 million in 2011-2012 on security upgrades for munitions storage sites and another $67 million in 2013-2014.

In March 2014, as part of the Fiscal Year 2015 budget request, the U.S. Department of Defense stated that NATO since 2000 had invested over $80 million in infrastructure improvements required to store nuclear weapons within secure facilities in storage sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. Another $154 million was planned for these sites on security improvements to meet with stringent new U.S. standards.

The following month, in April 2014, Andrew Weber, then Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs, told Congress that “NATO common funding has paid for over $300 million, approximately 75 percent of the B61 storage security infrastructure and upgrades” in Europe. Elaine Bunn, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, added that because host base facilities are funded through individual national budgets, “it is not possible to provide an accurate assessment of exactly how much NATO basing nations have contributed in Fiscal Year 2014 toward NATO nuclear burden sharing, although it is substantial.” Bunn provided additional information that showed funding of security enhancements and upgrades as well as funding of infrastructure upgrades (investment) at the specific European weapon storage sites. This funding, she explained, is provided through the NATO Security Investment Program (NSIP) and there have been four NATO weapons storage-related upgrades (Capability Package upgrades) since the original NATO Capability Package was approved in 2000:

In addition to the security upgrades underway at Incirlik and Aviano, upgrades of nuclear-related facilities are also underway or planned at national host bases that store U.S. nuclear weapons. This includes a new WS3 vault support facility and a MUNSS (Munitions Support Squadron) Operations Center-Command Post at Kleine Brogel AB in Belgium, and a WS3 vault support facility at Ghedi AB in Italy.

Implications and Recommendations

When I obtained a copy of the U.S. Air Force Blue Ribbon Review report in 2008 under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act and made it available on the FAS Strategic Security Blog, it’s most central finding – that “most” U.S. nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe did not meet U.S. security requirements – was dismissed by government officials in Europe and the United States.

During a debate in the Dutch Parliament, then Defense Minister Eimert van Middelkoop dismissed the findings saying “safety and security at Volkel are in good order.” A member of the U.S. Congressional delegation that was sent to Europe to investigate told me security problems were minor and could be fixed by routine management, a view echoed in conversations with other officials since then.

Yet seven years and more than $170 million later, construction of improved security perimeters at Incirlik AB and Aviano AB suggest that security of nuclear weapons storage vaults in Europe has been inadequate for the past two and a half decades and that official European and U.S. confidence was misguided (as they were reminded by European peace activists in 2010).

And the security upgrades do raise a pertinent question: since NATO now has decided that it is necessary after all to enhance security perimeters around underground vaults with nuclear weapons at the two U.S. bases at Incirlik and Aviano, doesn’t that mean that security at the four European national bases that currently store nuclear weapons (Büchel, Ghedi, Kleine Brogel, and Volkel) is inadequate? Ghedi reportedly was recently eyed by suspected terrorists arrested by the Italian police.

Just wondering.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Nuclear Weapons Base In Italy Eyed By Alleged Terrorists

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two suspected terrorists arrested by the Italian police allegedly were planning an attack against the nuclear weapons base at Ghedi.

The base stores 20 US B61 nuclear bombs earmarked for delivery by Italian PA-200 Tornado fighter-bombers in war. Nuclear security and strike exercises were conducted at the base in 2014. During peacetime the bombs are under the custody of the US Air Force 704th Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a 130-personnel strong units at Ghedi Air Base.

The Italian police said at a press conference today that the two men in their conversations “were referring to several targets, particularly the Ghedi military base” near Brescia in northern Italy.

Ghedi Air Base is one of several national air bases in Europe that a US Air Force investigation in 2008 concluded did not meet US security standards for nuclear weapons storage. Since then, the Pentagon and NATO have spent tens of millions of dollars and are planning to spend more to improve security at the nuclear weapons bases in Europe.

There are currently approximately 180 US B61 bombs deployed in Europe at six bases in five NATO countries: Belgium (Kleine Brogel AB), Germany (Buchel AB), Italy (Aviano AB and Ghedi AB), the Netherlands (Volkel AB), and Turkey (Incirlik AB).

Over the next decade, the B61s in Europe will be modernized and, when delivered by the new F-35A fighter-bomber, turned into a guided nuclear bomb (B61-12) with greater accuracy than the B61s currently deployed in Europe. Aircraft integration of the B61-12 has already started.

Read also:

– Italy’s Nuclear Anniversary: Fake Reassurance For a King’s Ransom

– B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Obama Administration Releases New Nuclear Warhead Numbers

By Hans M. Kristensen

In a speech to the Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in New York earlier today, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry disclosed new information about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

Updated Stockpile Numbers

First, Kerry updated the DOD nuclear stockpile history by declaring that the stockpile as of September 2014 included 4,717 nuclear warheads. That is a reduction of 87 warheads since September 2013, when the DOD stockpile included 4,804 warheads, or a reduction of about 500 warheads retired since President Obama took office in January 2009.

The September 2014 number of 4,717 warheads is 43 warheads off the estimate we made in our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook in March this year.

Disclosure of Dismantlement Queue

Second, Kerry also announced a new number we have never seen in public before: the official number of retired nuclear warheads in line for dismantlement. As of September 2014, the United States had approximately 2,500 additional warheads that have been retired (but are still relatively intact) and awaiting dismantlement.

The number of “approximately 2,500” retired warheads awaiting dismantlement is close to the 2,340 warheads we estimated in the FAS Nuclear Notebook in March 2015.

Increasing Warhead Dismantlements

Kerry also announced that the administration “will seek to accelerate the dismantlement of retired nuclear warheads by 20 percent.”

“Over the last 20 years alone, we have dismantled 10,251 warheads,” Kerry announced.

This updates the count of 9,952 dismantled warheads from the 2014 disclosure, which means that the administration between September 2013 and September 2014 dismantled 299 retired warheads.

Under current plans, of the “approximately 2,500” warheads in the dismantlement queue, the ones that were retired through (September) 2009 will be dismantled by 2022. Additional warheads retired during the past five years will take longer.

How the administration will accelerate dismantlement remains to be seen. The FY2016 budget request for NNSA pretty much flatlines funding for weapons dismantlement and disposition through 2020. In the same period, the administration plans to complete production of the W76-1 warhead, begin production of the B61-12, and carry out refurbishments of four other warheads. If the administration wanted to dismantle all “approximately 2,500” retired warheads by 2022 (including those warheads retired after 2009), it would have to dismantle about 312 warheads per year – a rate of only 13 more than it dismantled in 2014. So this can probably be done with existing capacity.

Implications

Secretary Kerry’s speech is an important diplomatic gesture that will help the United States make its case at the NPT review conference that it is living up to its obligations under the treaty. Some will agree, others will not. The nuclear-weapon states are in a tough spot at the NPT because there are currently no negotiations underway for additional reductions; because the New START Treaty, although beneficial, is modest; and because the nuclear-weapon states are reaffirming the importance of nuclear weapons and modernizing their nuclear arsenals as if they plan to keep nuclear weapons indefinitely (see here for worldwide status of nuclear arsenals).

And the disclosure is a surprise. As recently as a few weeks ago, White House officials said privately that the United States would not be releasing updated nuclear warhead numbers at the NPT conference. Apparently, the leadership decided last minute to do so anyway. [Update: another White House official says the release was cleared late but that it had been the plan to release some numbers all along.]

The roughly 500 warheads cut from the stockpile by the Obama administration is modest and a disappointing performance by a president that has spoken so much about reducing the numbers and role of nuclear weapons. Unfortunately, the political reality has been an arms control policy squeezed between a dismissive Russian president and an arms control-hostile U.S. Congress.

In addition to updating the stockpile history, the most important part of the initiative is the disclosure of the number of weapons awaiting dismantlement. This is an important new transparency initiative by the administration that was not included in the 2010 or 2014 stockpile transparency initiatives. Disclosing dismantlement numbers helps dispel rumors that the United States is hiding a secret stash of nuclear warheads and enables the United States to demonstrate actual dismantlement progress.

And, besides, why would the administration not want to disclose to the NPT conference how many warheads it is actually working on dismantling? This can only help the United States at the NPT review conference.

There will be a few opponents of the transparency initiative. Since they can’t really say this harms U.S. national security, their primary argument will be that other nuclear-armed states have so far not response in kind.

Russia and China have not made public disclosures of their nuclear warhead inventories. Britain and France has said a little on a few occasions about their total inventories and (in the case of Britain) how many warheads are operationally available or deployed, but not disclosed the histories of stockpiles or dismantlement. And the other nuclear-armed states that are outside the NPT (India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan) have not said anything at all.

But this is a work in progress. It will take a long time to persuade other nuclear-armed states to become more transparent with basic information about nuclear arsenals. But seeing that it can be done without damaging national security and at the same time helping the NPT process is important to cut through old-fashioned excessive nuclear secrecy and increase nuclear transparency. Hat tip to the Obama administration.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Treaty Count: Russia Dips Below US Again

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian deployed strategic warheads counted by the New START Treaty once again slipped below the U.S. force level, according to the latest fact sheet released by the State Department.

The so-called aggregate numbers show that Russia as of March 1, 2015 deployed 1,582 warheads on 515 strategic launchers.

The U.S. count was 1,597 warheads on 785 launchers.

Back in September 2014, the Russian warhead count for the first time in the treaty’s history moved above the U.S. warhead count. The event caused U.S. defense hawks to say it showed Russia was increasing it nuclear arsenal and blamed the Obama administration. Russian news media gloated Russia had achieved “parity” with the United States for the first time.

Of course, none of that was true. The ups and downs in the aggregate data counts are fluctuations caused by launchers moving in an out of overhaul and new types being deployed while old types are being retired. The fact is that both Russia and the United States are slowly – very slowly – reducing their deployed forces to meet the treaty limits by February 2018.

New START Count, Not Total Arsenals

And no, the New START data does not show the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States, only the portion of them that is counted by the treaty.

While New START counts 1,582 Russian deployed strategic warheads, the country’s total warhead inventory is much higher: an estimated 7,500 warheads, of which 4,500 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The United States is listed with 1,597 deployed strategic warheads, but actually possess an estimated 7,100 warheads, of which about 4,760 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The two countries only have to make minor adjustments to their forces to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads by February 2018.

Launcher Disparity

The launchers (ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) are a different matter. Russia has been far below the treaty limit of 700 deployed launchers since before the treaty entered into effect in 2011. Despite the nuclear “build-up” alleged by some, Russia is currently counted as deploying 515 launchers – 185 launchers below the treaty limit.

In other words, Russia doesn’t have to reduce any more launchers under New START. In fact, it could deploy an additional 185 nuclear missiles over the next three years and still be in compliance with the treaty.

The United States is counted as deploying 785 launchers, 270 more than Russia. The U.S. has a surplus in all three legs of its strategic triad: bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs. To get down to the 700 launchers, the U.S. Air Force will have to destroy empty ICBM silos, dismantle nuclear equipment from excess B-52H bombers, and the U.S. Navy will reduce the number of launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 20.

In 2015 the U.S. Navy will begin reducing the number of missile tubes from 24 to 20 on each SSBN, three of which are seen in this July 2014 photo at Kitsap Naval Submarine Base at Bangor (WA). The image also shows construction underway of a second Trident Refit Facility (coordinates: 47.7469°, -122.7291°). Click image for full size,

Even when the treaty enters into force in 2018, a considerable launcher disparity will remain. The United States plans to have the full 700 deployed launchers. Russia’s plans are less certain but appear to involve fewer than 500 deployed launchers.

Russia is compensating for this disparity by transitioning to a posture with a greater share of the ICBM force consisting of MIRVed missiles on mobile launchers. This is bad for strategic stability because a smaller force with more warheads on mobile launchers would have to deploy earlier in a crisis to survive. Russia has already begun to lengthen the time mobile ICBM units deploy away from their garrisons.

Modernization of mobile ICBM garrison base at Nizhniy Tagil in the Sverdlovsk province in Central Russia. The garrison is upgrading from SS-25 to SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) (coordinates: 58.2289°, 60.6773°). Click image for full size.

It seems obvious that the United States and Russia will have to do more to cut excess capacity and reduce disparity in their nuclear arsenals.

The INF Crisis: Bad Press and Nuclear Saber Rattling

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian online news paper Vzglaid is carrying a story that wrongly claims that I have said a Russian flight-test of an INF missile would not be a violation of the INF Treaty as long as the missile is not in production or put into service.

That is of course wrong. I have not made such a statement, not least because it would be wrong. On the contrary, a test-launch of an INF missile would indeed be a violation of the INF Treaty, regardless of whether the missile is in production or deployed.

Meanwhile, US defense secretary Ashton Carter appears to confirm that the ground-launched cruise missile Russia allegedly test-launched in violation of the INF Treaty is a nuclear missile and threatens further escalation if it is deployed.

Background

The error appears to have been picked up by Vzglaid (and apparently also sputniknews.com, although I haven’t been able to find it yet) from an article that appeared in a Politico last Monday. Squeezed in between two quotes by me, the article carried the following paragraph: “And as long as Russia’s new missile is not deployed or in production, it technically has not violated the INF.” Politico did not explicitly attribute the statement to me, but Vzglaid took it one step further:

According to Hans Kristensen, a member of the Federation of American Scientists, from a technical point of view, even if the Russian side and tests a new missile, it is not a breach of the contract as long as it does not go into production and will not be put into service.

Again, I didn’t say that; nor did Politico say that I said that. Politico has since removed the paragraph from the article, which is available here.

The United States last year officially accused Russia of violating the INF Treaty by allegedly test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a range that violates the provisions of the treaty. Russia rejected the accusation and counter-accused the United States for violating the treaty (see also ACA’s analysis of the Russian claims).

Conventional or Nuclear GLCM?

The US government has not publicly provided details about the Russian missile, except saying that it is a GLCM, that it has been test-launched several times since 2008, and that it is not currently in production or deployed. But US officials insist they have provided enough information to the Russian government for it to know what missile they’re talking about.

US statements have so far, as far as I’m aware, not made clear whether the GLCM test-launched by Russia is conventional, nuclear, or dual-capable. It is widely assumed in the public debate that it concerns a nuclear missile, but the INF treaty bans any ground-launched missile, whether nuclear or conventional. So the alleged treaty violation could potentially concern a conventional missile.

However, in a written answer to advanced policy questions from lawmakers in preparation for his nomination hearing in February for the position of secretary of defense, Ashton Carter appeared to identify the Russian GLCM as a nuclear system:

Question: What does Russia’s INF violation suggest to you about the role of nuclear weapons in Russian national security strategy?

Carter: Russia’s INF Treaty violation is consistent with its strategy of relying on nuclear weapons to offset U.S. and NATO conventional superiority.

That explanation would imply that US/ NATO conventional superiority to some extent has triggered Russian development and test-launch of the new nuclear GLCM. China and the influence of the Russian military-industrial complex might also be factors, but Russian defense officials and strategists are generally paranoid about NATO and seem convinced it is a real and growing threat to Russia. Western officials will tell you that they would not want to invade Russia even if you paid them to do it; only a Russian attack on NATO territory or forces could potentially trigger US/NATO retaliation against Russian forces.

Possible Responses To A Nuclear GLCM?

The Obama administration is currently considering how to respond if Russia does not return to INF compliance but produces and deploys the new nuclear GLCM. Diplomacy and sanctions have priority for now, but military options are also being considered. According to Carter, they should be designed to “ensure that Russia does not gain a military advantage” from deploying an INF-prohibited system:

The range of options we should look at from the Defense Department could include active defenses to counter intermediate-range ground-launched cruise missiles; counterforce capabilities to prevent intermediate-range ground-launched cruise missile attacks; and countervailing strike capabilities to enhance U.S. or allied forces. U.S. responses must make clear to Russia that if it does not return to compliance our responses will make them less secure than they are today.

What to do? Defense Secretary Ashton Carter wants to use counterforce and countervailing planning if Russia deploys its new ground-launched nuclear cruise missile.

The answer does not explicitly imply that a response would necessarily involve developing and deploying nuclear cruises missiles in Europe. Doing so would signal intent to abandon the INF Treaty but the Obama administration wants to maintain the treaty. Yet the reference to using “counterforce capabilities to prevent” GLCM attacks and “countervailing strike capability to enhance U.S. or allied forces” sound very 1980’ish.

Counterforce is a strategy that focuses on holding at risk enemy military forces. Using it to “prevent” attack implies drawing up plans to use conventional or nuclear forces to destroy the GLCM before it could be used. Current US nuclear employment strategy already is focused on counterforce capabilities and does not rely on countervalue and minimum deterrence, according to the Defense Department. Given that a GLCM would be able to strike its target within an hour (depending on range), preempting launch would require time-compressed strike planning and high readiness of forces, which would further deepen Russian paranoia about NATO intensions.

“Countervailing” was a strategy developed by the Carter administration to improve the flexibility and efficiency of nuclear forces to control and prevail in a nuclear war against the Soviet Union. The strategy was embodied in Presidential Directive-59 from July 1980. PD-59 has since been replaced by other directives but elements of it are still very much alive in today’s nuclear planning. Enhancing the countervailing strike capability of US and NATO forces would imply further improving their ability to destroy targets inside Russia, which would further deepen Russian perception of a NATO threat.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Part of Carter’s language is probably intended to scare Russian officials into concluding that the cost to Russia of deploying the GLCM would be higher than the benefits of restoring INF compliance – a 21st century version of the NATO double-track decision in 1979 that threatened deployment of INF missiles in Europe unless the Soviet Union agreed to limits on such weapons.

Back then the threat didn’t work at first. The Soviet Union rejected limitations and NATO went ahead and deployed INF missiles in Europe. Only when public concern about nuclear war triggered huge demonstrations in Europe and the United States did Soviet and US leaders agree to the INF Treaty that eliminated those weapons.

Reawakening the INF spectra in Europe would undermine security for all. Both Russia and the United States have to be in compliance with their arms control obligations, but threatening counterforce and countervailing escalation at this point may be counterproductive. Vladimir Putin does not appear to be the kind of leader that responds well to threats. And the INF issue has now become so entangled in the larger East-West crisis over Ukraine that it’s hard to see why Putin would want to be seen to back down on INF even if he agreed treaty compliance is better for Russia.

In fact, the military blustering and posturing that now preoccupy Russia and NATO could deepen the INF crisis. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and increased air operations across Europe fuel anxiety in NATO that leads to the very military buildup and modernization Russian officials say they are so concerned about. And NATO’s increased conventional operations and deployments in Eastern NATO countries probably deepen the Russian rationale that triggered development of the new GLCM in the first place.

Will Carter’s threat work? Right now it seems like one hell of a gamble.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

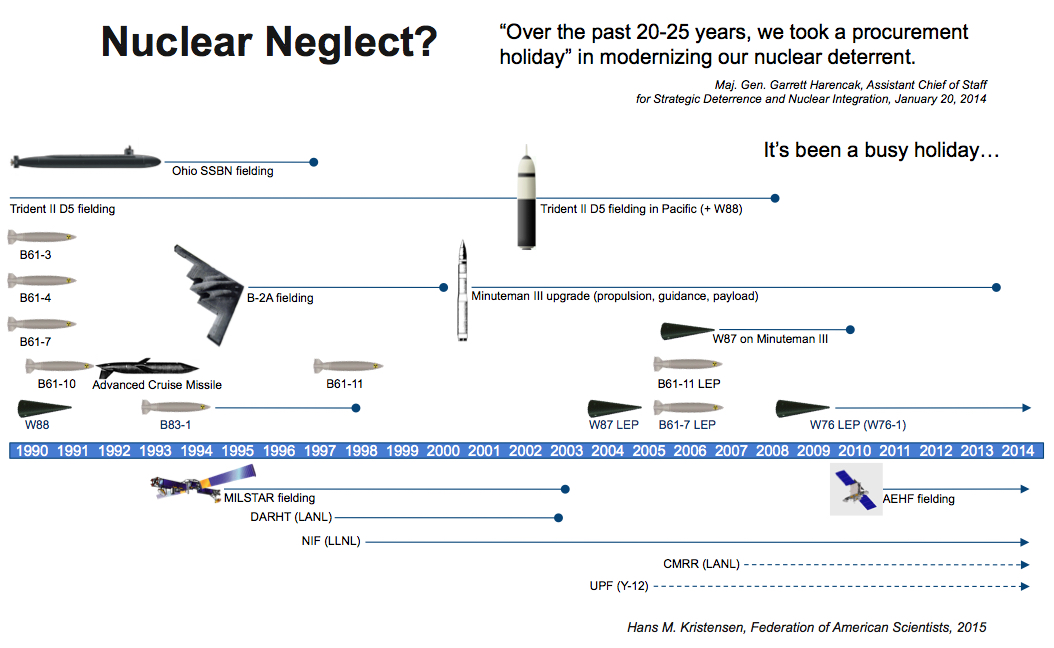

The Nuclear Weapons “Procurement Holiday”

It has become popular among military and congressional leaders to argue that the United States has had a “procurement holiday” in nuclear force planning for the past two decades.

“Over the past 20-25 years, we took a procurement holiday” in modernizing U.S. nuclear forces, Major General Garrett Harencak, the Air Force’s assistant chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, said in a speech yesterday.

Harencak’s claim strongly resembles the statement made by then-commander of US Air Force Global Strike Command, Lt. General Jim Kowalski, that the United States had “taken about a 20 year procurement holiday since the Soviet Union dissolved.”

Kowalski, who is now deputy commander at US Strategic Command, made a similar claim in May 2012: “Our nation has enjoyed an extended procurement holiday as we’ve deferred vigorous modernization of our nuclear deterrent forces for almost 20 years.”

One can always want more, but the “procurement holiday” claim glosses over the busy nuclear modernization and maintenance efforts of the past two decades.

About That Holiday…

If “holiday” generally refers to “a day of festivity or recreation when no work is done,” then its been a bad holiday. For during the “procurement holiday” described by Harencak, the United States has been busy fielding and upgrading submarines, bombers, missiles, cruise missiles, gravity bombs, reentry vehicles, command and control satellites, warhead surveillance and production facilities (see image below).

Despite claims about a two-decade long nuclear weapons “procurement holiday,” the United States has actually been busy modernizing and maintaining its nuclear forces.

The not-so-procurement-holiday includes fielding of eight of 14 Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines (the last in 1997), fielding of the Trident II sea-launched ballistic missile (the world’s most reliable nuclear missile), all 21 B-2A stealth bombers (the last in 2000), an $8 billion-plus complete overhaul of the entire Minuteman III ICBM force including back-fitting it with the W87 warhead, five B61 bomb modifications, one modification of the B83 bomb, a nuclear cruise missile, the W88 warhead, completed three smaller life-extensions of the W87 ICBM warhead and two B61 modifications, and developed and commenced full-scale production of the modified W76-1 warhead.

Harencak’s job obviously is to advocate nuclear modernization but glossing over the considerable efforts that have been done to maintain the nuclear deterrent for the past two decades is, well, kind of embarrassing.

Russia and China have continued to introduce new weapons and the United States is falling behind, so the warning from Harencak and others goes. But modernizations happen in cycles. Generally speaking, the previous Russian strategic modernization happened in the 1970s and 1980s (the country was down on its knees much of the 1990s), so now we’re seeing their next round of modernizations. Similarly, China modernized in the 1970s and 1980s so now we’re seeing their next cycle. (For an overview about worldwide nuclear weapons modernization programs, see this article.)

The United States modernized later (1980s-2000s), and since then has focused more on refurbishing and life-extending existing weapons instead of wasting money on mindlessly deploying new systems.

What the next cycle of U.S. nuclear modernizations should look like, how much is needed and with what kinds of capabilities, requires a calm and intelligent assessment.

Comparing Nuclear Apples and Oranges With a Vengeance

“Once you strip away all the emotions, once you strip away all the ‘I just don’t like nuclear weapons,’ OK fine. Alright. And I would love to live in a world that doesn’t have it. But you live in this world. And in this world there still is a nuclear threat,” Harencak said yesterday in an apparent rejection of at least part of his Commander-in-Chief’s 2009 Prague speech.

“This nuclear deterrent, here in January 2015, I’m here to tell you, is relevant and is as needed today as it was in January 1965, and 1975, and 1985, and 1995. And it will be till that happy day comes when we rid the world of nuclear weapons. It will be just as relevant in 2025, ten years from now…it will still be as relevant,” he claimed.

God forbid we have emotions when assessing the nuclear mission, but I fear Harencak may be doing the deterrent mission a disservice with his over-zealot nuclear advocacy that belittles other views and time-jumps from Cold War relevance to today’s world.

Whether or not one believes that nuclear weapons are relevant and needed (or to what extent) in today’s world, to suggest that they are as relevant and as needed today as during the nail-biting and gong-ho conditions that characterized the Cold War demonstrates a surprising lack of understanding and perspective. Remember: the Cold War that held the world hostage at gunpoint with tens of thousands of nuclear weapons deployed around the world only minutes from global annihilation?

Even with Russian and Chinese nuclear modernizations, there is no indication that today’s threats or challenges are even remotely as dire or as intense as the Cold War.

Instead of false claims about “procurement holiday” and demonization of other views – listen for example to Harencak’s new bomber argument: if you don’t want to pay for my grant child to destroy enemy targets with the next-generation bomber, then send your own grandchild! – how about an intelligent debate about how much is needed, for what purpose, and at what cost?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rumors About Nuclear Weapons in Crimea

The news media and private web sites are full of rumors that Russia has deployed nuclear weapons to Crimea after it invaded the region earlier this year. Many of these rumors are dubious and overly alarmist and ignore that a nuclear-capable weapon is not the same as a nuclear warhead.

Several U.S. lawmakers who oppose nuclear arms control use the Crimean deployment to argue against further reductions of nuclear weapons. NATO’s top commander, U.S. General Philip Breedlove, has confirmed that Russian forces “capable of being nuclear” are being moved to the Crimean Peninsula, but also acknowledged that NATO doesn’t know if nuclear warheads are actually in place.

Recently Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Alexei Meshkov said that NATO was “transferring aircraft capable of carrying nuclear arms to the Baltic states,” and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reminded that Russia has the right to deploy nuclear weapons anywhere on its territory, including in newly annexed Crimea.

Whether intended or not, non-strategic nuclear weapons are already being drawn into the new East-West crisis.

What’s New?

First a reminder: the presence of Russian dual-capable non-strategic nuclear forces in Crimea is not new; they have been there for decades. They were there before the breakup of the Soviet Union, they have been there for the past two decades, and they are there now.

In Soviet times, this included nuclear-capable warships and submarines, bombers, army weapons, and air-defense systems. Since then, the nuclear warheads for those systems were withdrawn to storage sites inside Russia. Nearly all of the air force, army, and air-defense weapon systems were also withdrawn. Only naval nuclear-capable forces associated with the Black Sea Fleet area of Sevastopol stayed, although at reduced levels.

Yet with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea, a military reinforcement of military facilities across the peninsula has begun. This includes deployment of mainly conventional forces but also some systems that are considered nuclear-capable.

Naval Nuclear-Capable Forces

The Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol includes nuclear-capable cruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and submarines. They are capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles and torpedoes. But the warheads for those weapons are thought to be in central storage in Russia.

A nuclear-capable SS-N-12 cruise missile is loaded into one of the 16 launchers on the Slava-class cruiser in Sevastopol (top). In another part of the harbor, a nuclear-capable SS-N-22 cruise missile is loaded into one of eight launchers on a Dergach-class corvette (insert).

There are several munitions storage facilities in the Sevastopol area but none seem to have the security features required for storage of nuclear weapons. The nearest national-level nuclear weapons storage site is Belgorod-22, some 690 kilometers to the north on the other side of Ukraine.

Backfire Bombers

There is a rumor going around that president Putin last summer ordered deployment of intermediate-range Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers to Crimea.

Rumors say that Russia plans to deploy Tu-22M3 intermediate-range bombers (see here with two AS-4 nuclear-capable cruise missiles) to Crimea.

One U.S. lawmaker claimed in September that Putin had made an announcement on August 14, 2014. But even before that, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in March and annexed Crimea, Jane’s Defence Weekly quoted a Russian defense spokesperson describing plans to deploy Backfires to Gvardiesky (Gvardeyskoye) along with Tu-142 and Il-38 in 2016 after upgrading the base. Doing so would require major upgrades to the base.

Russia appears to have four operational Backfire bases: Olenegorsk Air Base on the Kola Peninsula (all naval aviation is now under the tactical air force) and Shaykovka Air Base near Kirov in Kaluzhskaya Oblast near Belarus in the Western Military District (many of the Backfires intercepted over the Baltic Sea in recent months have been from Shaykovka); Belaya in Irkutsk Oblast in the Central Military District; and Alekseyevka near Mongokhto in Khabarovsk Oblast in the Eastern Military District. A fifth base – Soltsy Air Base in Novgorod Oblast in the Western Military District – is thought to have been disbanded.

The apparent plan to deploy Backfires in Crimea is kind of strange because the intermediate-range bomber doesn’t need to be deployed in Crimea to be able to reach potential targets in Western Europe. Another potential mission could be for maritime strikes in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea, but deployment to Crimea will only give it slightly more reach in the southern and western parts of the Mediterranean Sea (see map below). And the forward deployment would make the aircraft much more vulnerable to attack.

Deployment of Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers to Crimea would increase strike coverage of the southern parts of the Mediterranean Sea some compared with Backfires currently deployed at Shaykovka Air Base, but it would not provide additional reach of Western Europe.

Iskander Missile Launchers

Another nuclear-capable weapon system rumored to be deployed or deploying to Crimea is the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile. Some of the sources that mention Backfire bomber deployment also mention the Iskander.

One of the popular sources of the Iskander rumor is an amateur video allegedly showing Russian military vehicles rolling through Sevastopol on May 2, 2014. The video caption posted on youtube.com specifically identified “Iskander missiles” as part of the column.

An amateur video posted on youtube reported Iskander ballistic missile launchers rolling through downtown Sevastopol. A closer look reveals that they were not Islander. Click image to view video.

A closer study of the video, however, reveals that the vehicles identified to be launchers for “Iskander missiles” are in fact launchers for the Bastion-P (K300P or SSC-5) costal defense cruise missile system. The Iskander-M and Bastion-P launchers look similar but the cruise missile canisters are longer, so the give-away is that the rear end of the enclosed missile compartments on the vehicles in the video extend further back beyond the fourth axle than is that case on an Iskander-M launcher.

While the video does not appear to show Iskander, Major General Alexander Rozmaznin of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, reportedly stated that a “division” of Iskander had entered Crimea and that “every missile system is capable of carrying nuclear warheads…”

The commander of Russia’s strategic missile forces, Colonel General Sergei Karakayev, recently ruled out rumors about deployment of strategic missiles in Crimea, but future plans for the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles in Crimea are less clear.

Russia is currently upgrading short-range ballistic missile brigades from the SS-21 (Tochka) to the SS-26 (Iskander-M) missile. Four of ten brigades have been upgraded or are in the process of upgrading (all in the western and southern military districts), and a fifth brigade will receive the Iskander in late-2014. In 2015, deployment will broaden to the Central and Eastern military districts.

The Iskander division closest to Crimea is based near Molkino in the Krasnodar Oblast. So for the reports about deployment of an Iskander division to Crimea to be correct, it would require a significant change in the existing Iskander posture. That makes me a little skeptical about the rumors; perhaps only a few launchers were deployed on an exercise or perhaps people are confusing the Iskander-M and the Bastion-P. We’ll have to wait for more solid information.

Air Defense

As a result of the 1991-1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives, roughly 60 percent of the Soviet-era inventory of warheads for air defense forces has been eliminated. The 40 percent that remains, however, indicates that Russian air defense forces such as the S-300 still have an important secondary nuclear mission.

The Ukrainian military operated several S-300 sites on Crimea, but they were all vacated when Russia annexed the region in March 2014. The Russian military has stated that it plans to deploy a complete integrated air defense system in Crimea, so some of the former Ukrainian sites may be re-populated in the future.

Just as quickly as the Ukrainian S-300 sites were vacated, however, two Russian S-300 units moved into the Gvardiesky Air Base. A satellite image taken on March 3, 2014, shows no launchers, but an image taken 20 days later shows two S-300 units deployed.

Two S-300 air defense units were deployed to Gvardiesky Air Base immediately after the Russian annexation of Crimea. The Russian Air Force moved Su-27 Flanker fighters in while retaining Su-24 Fencers (some of which are not operational). Click image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Russia has had nuclear-capable forces deployed in Crimea for many decades but rumors are increasing that more are coming.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet already has many types of ships and submarines capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles and torpedoes. More ships are said to be on their way.

Rumors about future deployment of Backfire bombers to Crimea would, if true, be a significant new development, but it would not provide significant new reach compared with existing Backfire bases. And forward-deploying the intermediate-range bombers to Crimea would increase their vulnerability to potential attack.

Some are saying Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles have been deployed, but no hard evidence has been presented and at least one amateur video said to show “Iskander missiles” instead appears to show a coastal missile defense system.

New air-defense missile units that may have nuclear capability are visible on satellite images.

It is doubtful that the nuclear-capable forces currently in Crimea are equipped with nuclear warheads. Their dual-capable missiles are thought to serve conventional missions and their nuclear warheads stored in central storage facilities in Russia.

Yet the rumors are creating uncertainty and anxiety in neighboring countries – especially when seen in context with the increasing Russian air-operations over the Baltic Sea and other areas – and fuel threat perceptions and (ironically) opposition to further reductions of nuclear weapons.

The uncertainty about what’s being moved to Crimea and what’s stored there illustrates the special problem with non-strategic nuclear forces: because they tend to be dual-capable and serve both nuclear and conventional roles, a conventional deployment can quickly be misinterpreted as a nuclear signal or escalation whether intended or real or not.

The uncertainty about the Crimea situation is similar (although with important differences) to the uncertainty about NATO’s temporary rotational deployments of nuclear-capable fighter-bombers to the Baltic States, Poland, and Romania. Russian officials are now using these deployments to rebuff NATO’s critique of Russian operations.

This shows that non-strategic nuclear weapons are already being drawn into the current tit-for-tat action-reaction posturing, whether intended or not. Both sides of the crisis need to be particularly careful and clear about what they signal when they deploy dual-capable forces. Otherwise the deployment can be misinterpreted and lead to exaggerated threat perceptions. It is not enough to hunker down; someone has to begin to try to resolve this crisis. Increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear force deployments – especially when they are not intended as a nuclear signal – would be a good way to start.

Additional information: report about U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pentagon Review To Fix Nuclear Problems – Again

Less than a decade after the Pentagon conducted a major review to fix problems in the nuclear management of U.S. nuclear forces, the Pentagon today announced the results of yet another review.

The new review identifies more than 100 fixes that are needed to correct management and personnel issues. The fixes “will cost several billion dollars over the five-year defense spending program in addition to ongoing modernization requirements identified in last year’s budget submission.” The Pentagon says it will “prioritize funding on actions that improve the security and sustainment of the current force, ensures that modernization of the force remains on track, and that address shortfalls, which are undermining the morale of the force.”

That sounds like a strategy doomed to fail without significant adjustments. The Pentagon is already planning to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on modernizing submarines, bombers, missiles, warheads, and production facilities over the next decade (and even more later).

Those modernization plans are already too expensive, under tremendous fiscal pressure, and competing for money needed to sustain and modernize conventional forces. So who is going to pay for the billions of dollars extra needed to fix the nuclear business?

Previous Fixes