USAF Plans To Expand Nuclear Bomber Bases

The US Air Force is working to expand the number of strategic bomber bases that can store nuclear weapons from two today to five by the 2030s.

The plan will also significantly expand the number of bomber bases that store nuclear cruise missiles from one base today to all five bombers bases by the 2030s.

The expansion is the result of a decision to replace the non-nuclear B-1B bombers at Ellsworth AFB and Dyess AFB with the nuclear B-21 over the next decade-and-a-half and to reinstate nuclear weapons storage capability at Barksdale AFB as well.

The expansion is not expected to increase the total number of nuclear weapons assigned to the bomber force, but to broaden the infrastructure to “accommodate mission growth,” Air Force Global Strike Command Commander General Timothy Ray told Congress last year.

Nuclear Bomber Base Expansion

The Air Force announced in May 2018 that the B-21 would replace the B-1B and B-2A bombers and be deployed at Ellsworth AFB, Dyess AFB, and Whiteman AFB. The commander of the strategic bomber force later explained in a video address to the B-1B bases that “the B-21 will bring significant changes to each location, to include the reintroduction of nuclear mission requirements.”

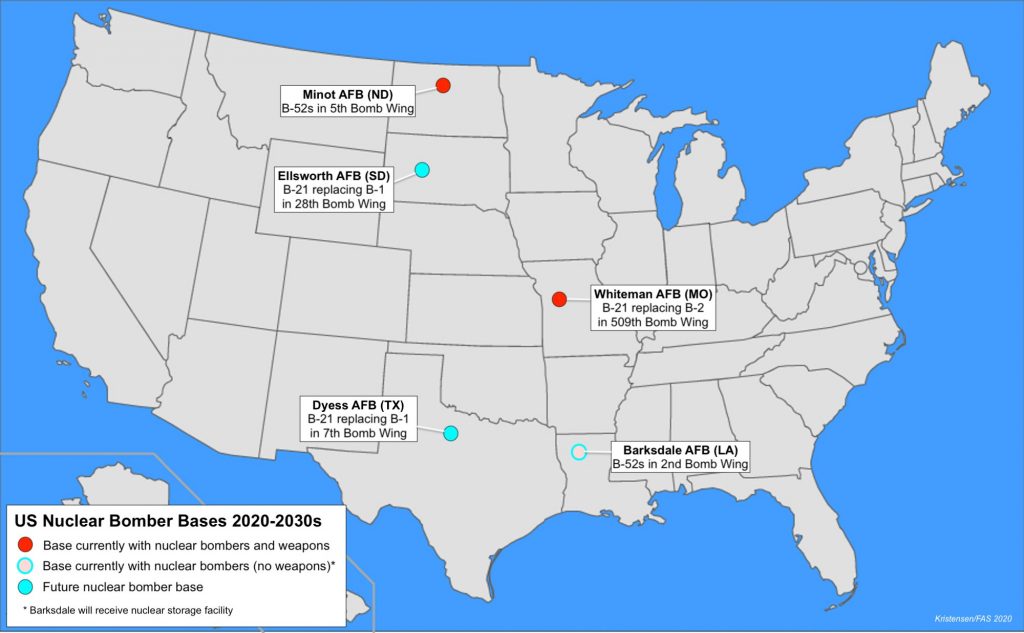

Since the B-1B was replaced in the nuclear war plan by the B-2A in 1997 and all B-1B bombers were denuclearized in 2011, the effect of the B-21 bomber program is that nuclear bomber operations will increase from the three bases today to five bases in the future (see map):

The Air Force plans to increase nuclear weapons storage capacity at bomber bases from two locations today to five in the future. Click map to view full size.

The Air Force previously planned for the B-21 to replace the B-2A no later than 2032 and the B-1Bs no later than 2036, though those dates may have shifted some since.

The effect of the integration of the B-21 is that bases with nuclear stealth bombers will increase from one today (Whiteman AFB) to three in the future.

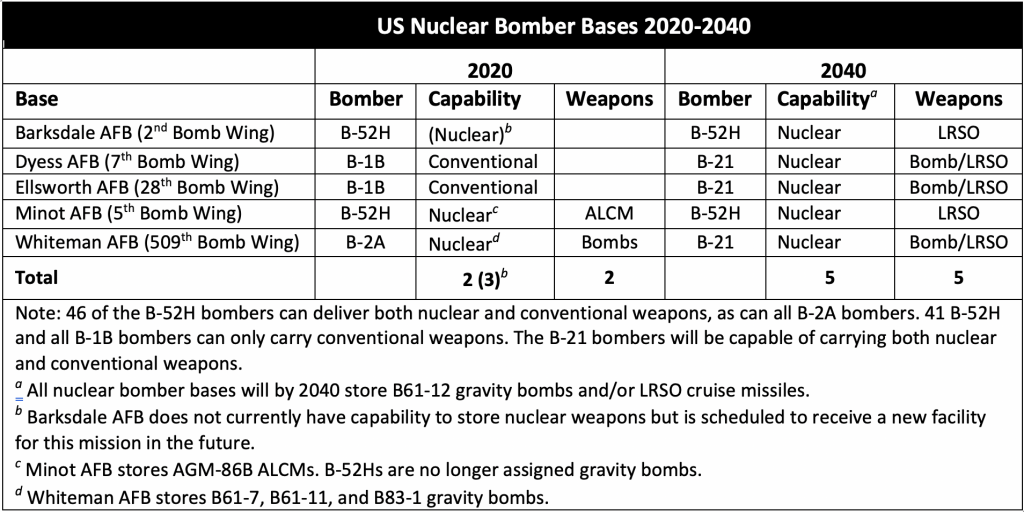

The modernization plan also appears to significantly expand the location of nuclear cruise missiles from one base today (Minot AFB) to all five bomber bases by the late-2030s. The LRSO is scheduled to begin entering the arsenal in 2030 (see table):

The US Air Force plans a significant expansion of nuclear bomber bases and their capabilities. Click table to view full size.

Nuclear Storage Facilities

A key element of the base upgrades to operate the B-21 involves the construction of a new nuclear weapons storage facility at each base: a Weapons Generation Facility (WGF). The new facility is different than the Weapons Storage Areas (WSAs) that that the Air Force built during the Cold War because it will integrate maintenance and storage mission sets into the same facility. The WGF will have a footprint of roughly 35 acres and include an approximately 52,000-square-foot (4,860 square meters) building as well as a 17,600 square-foot munitions maintenance building. The Air Force says the WGF will be “unique to the B-21 mission” and designed to provide a “safer and more secure location for the storage of Air Force nuclear munitions.”

An WGF is also under construction at F.E. Warren AFB for storage of ICBM warheads.

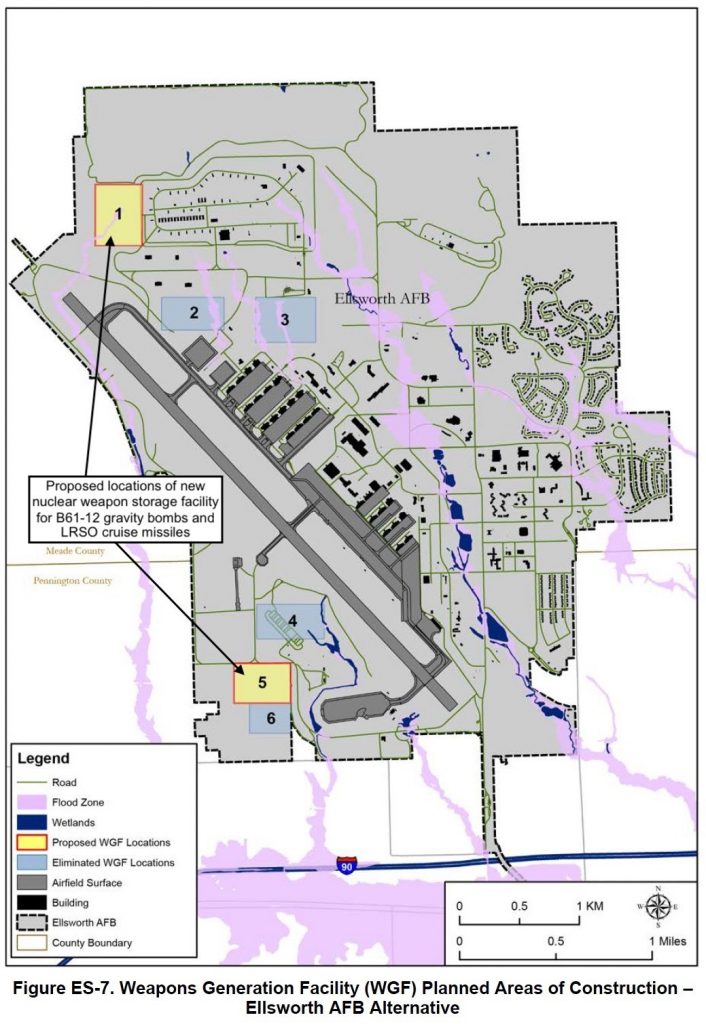

A draft Environmental Impact Statement recently posted by the Air Force shows the planned location of the nuclear weapons storage facility at Dyess and Ellsworth air force bases. At Dyess AFB, the intension is to build facility at the northern end of the base near the current munitions depot (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Dyess Air Force Base in Texas. Click on map to view full size.

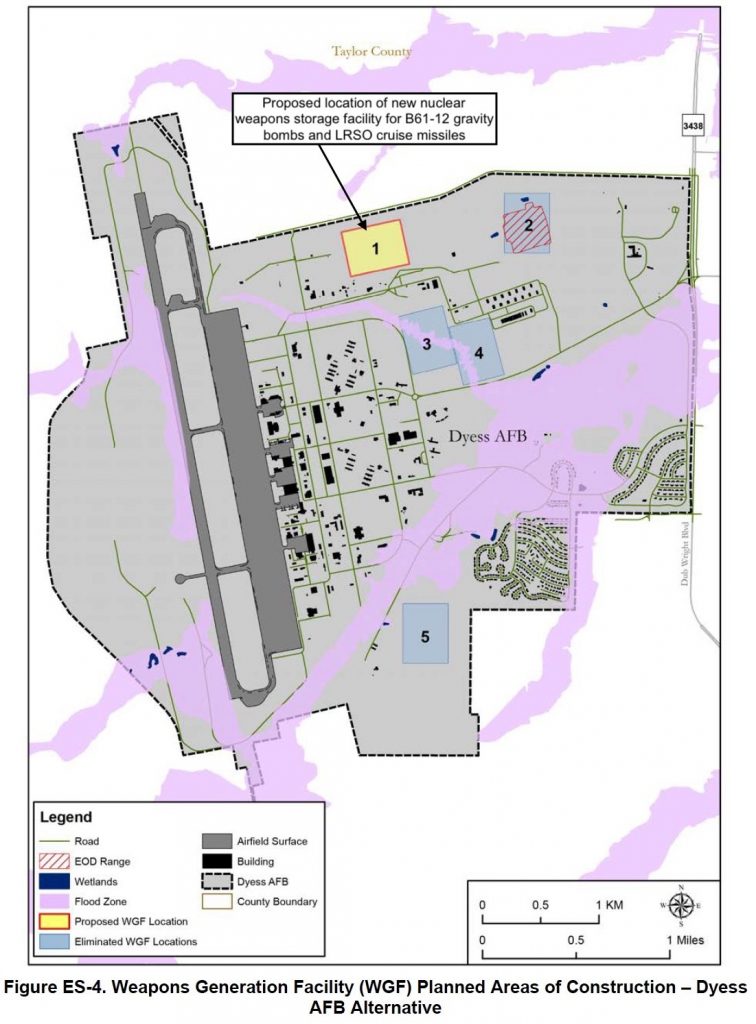

At Ellsworth AFB, the Air Force has identified two preferred locations: one at the northern end near the munitions depot, and one at the southern end near the aircraft alert apron (see map below):

The Air Force plans to add nuclear weapons storage capacity to Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota. Click on map to view full size.

Although Barksdale AFB is not scheduled to receive the B-21, preparations are underway to reinstate the capability to store nuclear weapons at the base. The capability was lost when the Air Force last decade consolidated operational nuclear ALCM storage at Minot AFB. Once completed, the new WGF will enable the base to store nuclear LRSO cruise missiles for delivery by the B-52s.

Nuclear Bomber Force Increase

The B-21 bomber program is expected to increase the overall size of the US strategic bomber force. The Air Force currently operates about 158 bombers (62 B-1B, 20 B-2A, and 76 B-52H) and has long said it plans to procure at least 100 B-21 bombers. That number now appears [https://www.airforcemag.com/article/strategy-policy-9/] to be at least 145, which will increase the overall bomber force by 62 bombers to about 220. There are currently nine bomber squadrons, a number the Air Force wants to increase to 14 (each base has more than one squadron).

During an interview with reporters in April, the head of AFGSC, General Timothy Ray, reportedly said the 220 number was a “minimum, not a ceiling” and added: “We as the Air Force now believe it’s over 220.” Whether Congress will agree to pay for that many B-21s remains to be seen.

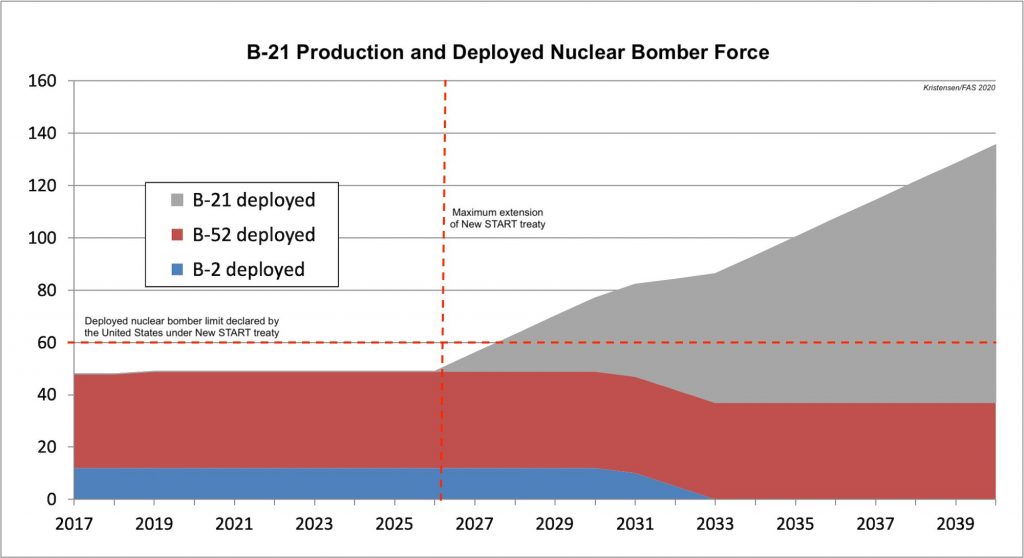

The fielding of large numbers of nuclear-capable B-21 bombers has implications for the future development of the US nuclear arsenal. Under the New START treaty, the United States has declared it will deploy no more than 60 nuclear bombers. Although the treaty will lapse in 2026 (after a five-year maximum extension), it serves as the baseline for long-term nuclear force structure planning.

Unless the Air Force limits the number of nuclear-equipped B-21 bombers to the number of B-2As operated today, the number of nuclear bombers would begin to exceed the 60 deployed nuclear bomber pledge by 2028 (assuming an annual production of nine aircraft and two-year delay in deployment of the first nuclear unit). By 2035, the number of deployed nuclear bombers could have doubled compared with today (see graph below):

Unless nuclear B-21 bombers are not limited, the future nuclear bomber force could significantly exceed the bomber force under the current New START treaty. Click graph to view full size.

It is difficult to imagine a military justification for such an increase in the number of nuclear bombers – even without New START. One would hope that the number of nuclear B-21s will be limited to well below the total number. Although the New START treaty would have expired before this becomes a a legal issue, it would already now send the wrong message to other nuclear-armed states about US long-term intensions, deepen suspicion and “Great Power Competition,” and could complicate future arms control talks.

In the short term, the incoming Biden administration should commit the United States to not increase the number of nuclear bombers beyond those planned under the New START treaty, and it should urge Russia to make a similar declaration about the size of its nuclear bomber force.

See also: Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear force, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan

Any time a US federal agency proposes a major action that “has the potential to cause significant effects on the natural or human environment,” they must complete an Environmental Impact Statement, or EIS. An EIS typically addresses potential disruptions to water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other factors in great detail––meaning that one can usually learn a lot about the scale and scope of a federal program by examining its Environmental Impact Statement.

What does all this have to do with nuclear weapons, you ask?

Well, given that the Air Force’s current plan to modernize its intercontinental ballistic missile force involves upgrading hundreds of underground and aboveground facilities, it appears that these actions have been deemed sufficiently “disruptive” to trigger the production of an EIS.

To that end, the Air Force recently issued a Notice of Intent to begin the EIS process for its Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) program––the official name of the ICBM replacement program. Usually, this notice is coupled with the announcement of open public hearings, where locals can register questions or complaints with the scope of the program. These hearings can be influential; in the early 1980s, tremendous public opposition during the EIS hearings in Nevada and Utah ultimately contributed to the cancellation of the mobile MX missile concept. Unfortunately, in-person EIS hearings for the GBSD have been cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic; however, they’ve been replaced with something that might be even better.

The Air Force has substituted its in-person meetings for an uncharacteristically helpful and well-designed website––gbsdeis.com––where people can go to submit comments for EIS consideration (before November 13th!). But aside from the website being just a place for civic engagement and cute animal photos, it is also a wonderful repository for juicy––and sometimes new––details about the GBSD program itself.

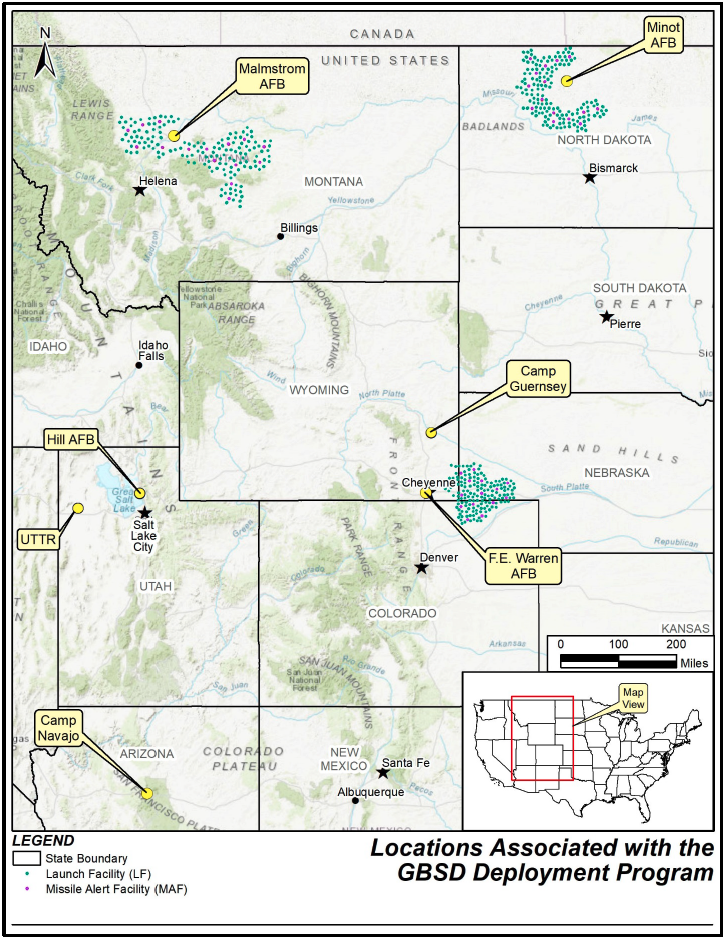

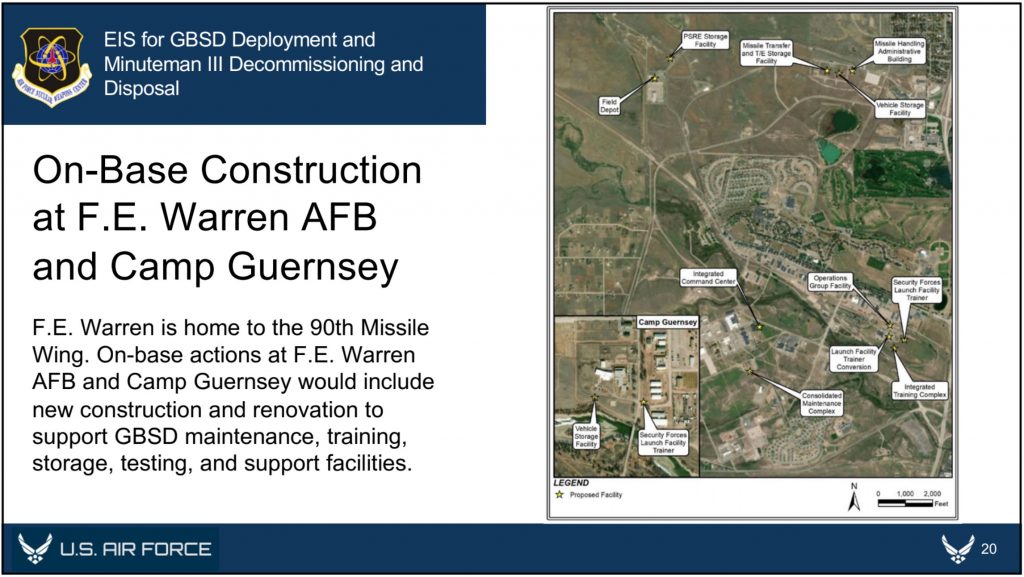

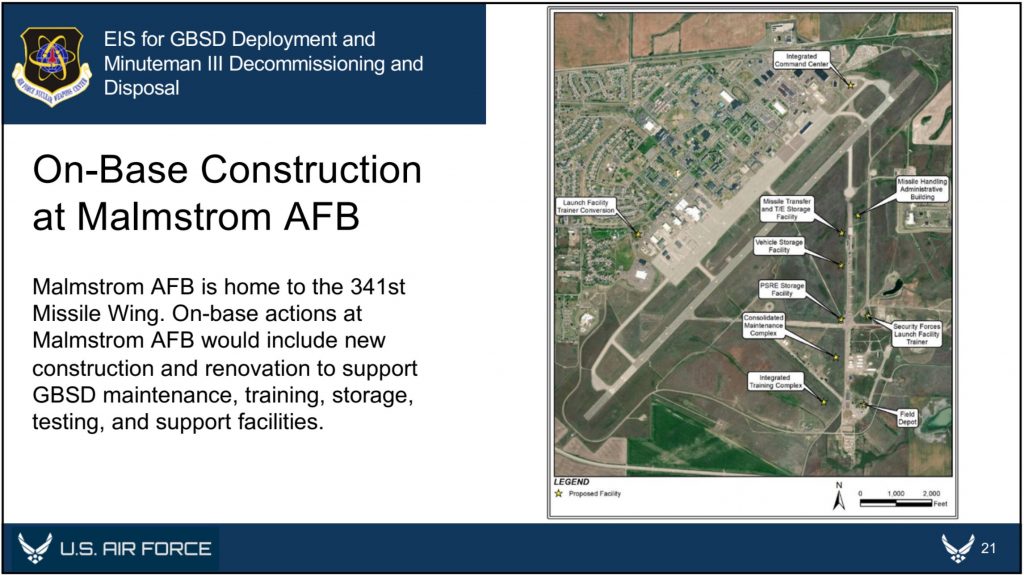

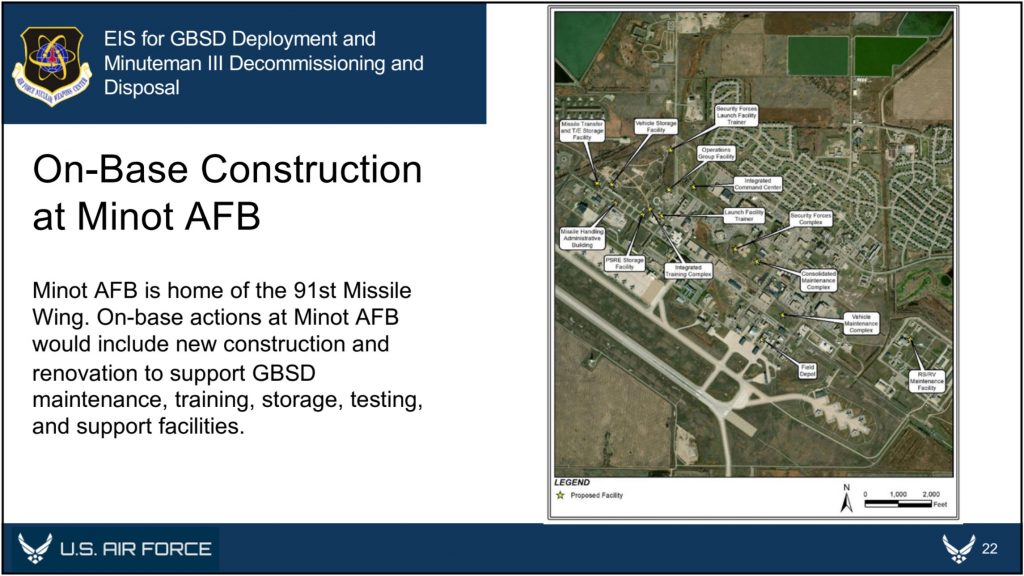

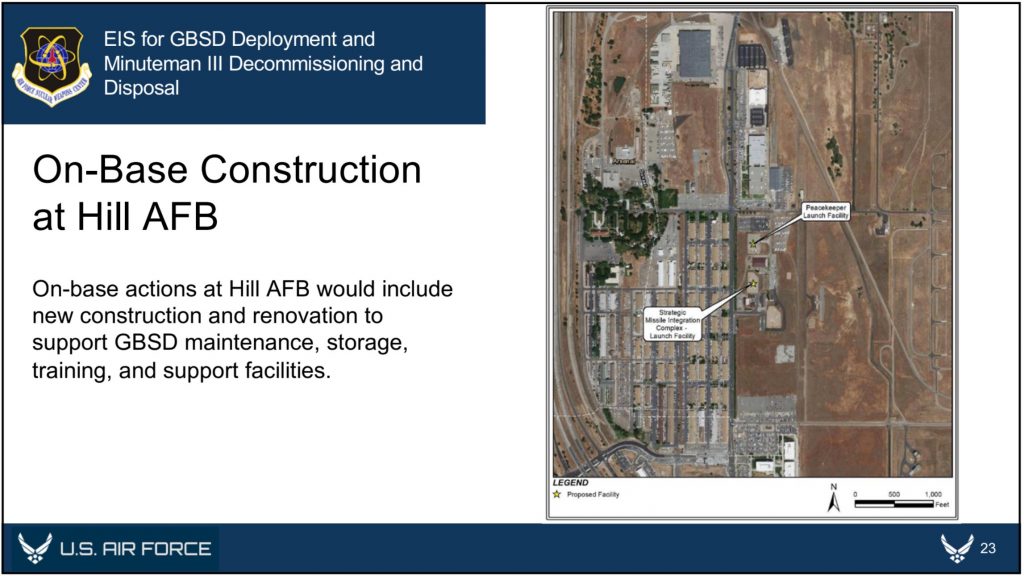

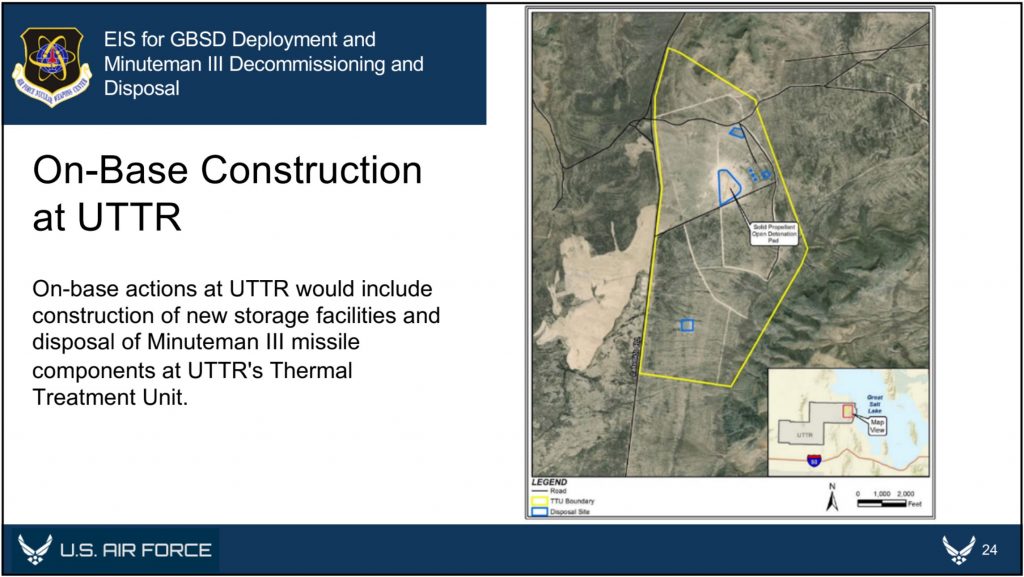

The website includes detailed overviews of the GBSD-related work that will take place at the three deployment bases––F.E. Warren (located in Wyoming, but responsible for silos in Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska), Malmstrom (Montana), and Minot (North Dakota)––plus Hill Air Force Base in Utah (where maintenance and sustainment operations will take place), the Utah Test and Training Range (where missile storage, decommissioning, and disposal activities will take place), Camp Navajo in Arizona (where rocket boosters and motors will be stored), and Camp Guernsey in Wyoming (where additional training operations will take place).

Taking a closer look at these overviews offers some expanded details about where, when, and for how long GBSD-related construction will be taking place at each location.

For example, previous reporting seemed to indicate that all 450 Minuteman Launch Facilities (which contain the silos themselves) and “up to 45” Missile Alert Facilities (each of which consists of a buried and hardened Launch Control Center and associated above- or below-ground support buildings) would need to be upgraded to accommodate the GBSD. However, the GBSD EIS documents now seem to indicate that while all 450 Launch Facilities will be upgraded as expected, only eight of the 15 Missile Alert Facilities (MAF) per missile field would be “made like new,” while the remainder would be “dismantled and the real property would be disposed of.”

Currently, each Missile Alert Facility is responsible for a group of 10 Launch Facilities; however, the decision to only upgrade eight MAFs per wing––while dismantling the rest––could indicate that each MAF could be responsible for up to 18 or 19 separate Launch Facilities once GBSD becomes operational. If this is true, then this near-doubling of each MAF’s responsibilities could have implications for the future vulnerability of the ICBM force’s command and control systems.

The GBSD EIS website also offers a prospective construction timeline for these proposed upgrades. The website notes that it will take seven months to modernize each Launch Facility, and 12 months to modernize each Missile Alert Facility. Once construction begins, which could be as early as 2023, the Air Force has a very tight schedule in order to fully deploy the GBSD by 2036: they have to finish converting one Launch Facility per week for nine years. It is expected that construction and deployment will begin at F.E. Warren between 2023 and 2031, followed by Malmstrom between 2025 and 2033, and finally Minot between 2027 and 2036.

Although it is still unclear exactly what the new Missile Alert Facilities and Launch Facilities will look like, the EIS documents helpfully offer some glimpses of the GBSD-related construction that will take place at each of the three Air Force bases over the coming years.

In addition to the temporary workforce housing camps and construction staging areas that will be established for each missile wing, each base is expected to receive several new training, storage, and maintenance facilities. With a single exception––the construction of a new reentry system and reentry vehicle maintenance facility at Minot––all of the new facilities will be built outside of the existing Weapons Storage Areas, likely because these areas are expected to be replaced as well. As we reported in September, construction has already begun at F.E. Warren on a new underground Weapons Generation Facility to replace the existing Weapons Storage Area, and it is expected that similar upgrades are planned for the other ICBM bases.

Finally, the EIS documents also provide an overview of how and where Minuteman III disposal activities will take place. Upon removal from their silos, the Minutemen IIIs will be transported to their respective hosting bases––F.E. Warren, Malmstrom, or Minot––for temporary storage. They will then be transported to Hill Air Force Base, the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), or Camp Najavo, in Arizona. It is expected that the majority of the rocket motors will be stored at either Hill AFB or UTTR until their eventual destruction at UTTR, while non-motor components will be demilitarized and disposed of at Hill AFB. To that end, five new storage igloos and 11 new storage igloos will be constructed at Hill AFB and UTTR, respectively. If any rocket motors are stored at Camp Navajo, they will utilize existing storage facilities.

After the completion of public scoping on November 13th (during which anyone can submit comments to the Air Force via Google Form), the next public milestone for the GBSD’s EIS process will occur in spring 2022, when the Air Force will solicit public comments for their Draft EIS. When that draft is released, we should learn even more about the GBSD program, and particularly about how it impacts––and is impacted by––the surrounding environment. These particular aspects of the program are growing in significance, as it is becoming increasingly clear that the US nuclear deterrent––and particularly the ICBM fleet deployed across the Midwest––is uniquely vulnerable to climate catastrophe. Given that the GBSD program is expected to cost nearly $264 billion through 2075, Congress should reconsider whether it is an appropriate use of public funds to recapitalize on elements of the US nuclear arsenal that could ultimately be rendered ineffective by climate change.

Additional background information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

-

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image sources: Air Force Global Strike Command. 2020. “Environmental Impact Statement for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent Deployment and Minuteman III Decommissioning and Disposal: Public Scoping Materials.”

US Officials Give Confusing Comparisons Of US And Russian Nuclear Forces

October 22, 2020 [updated]

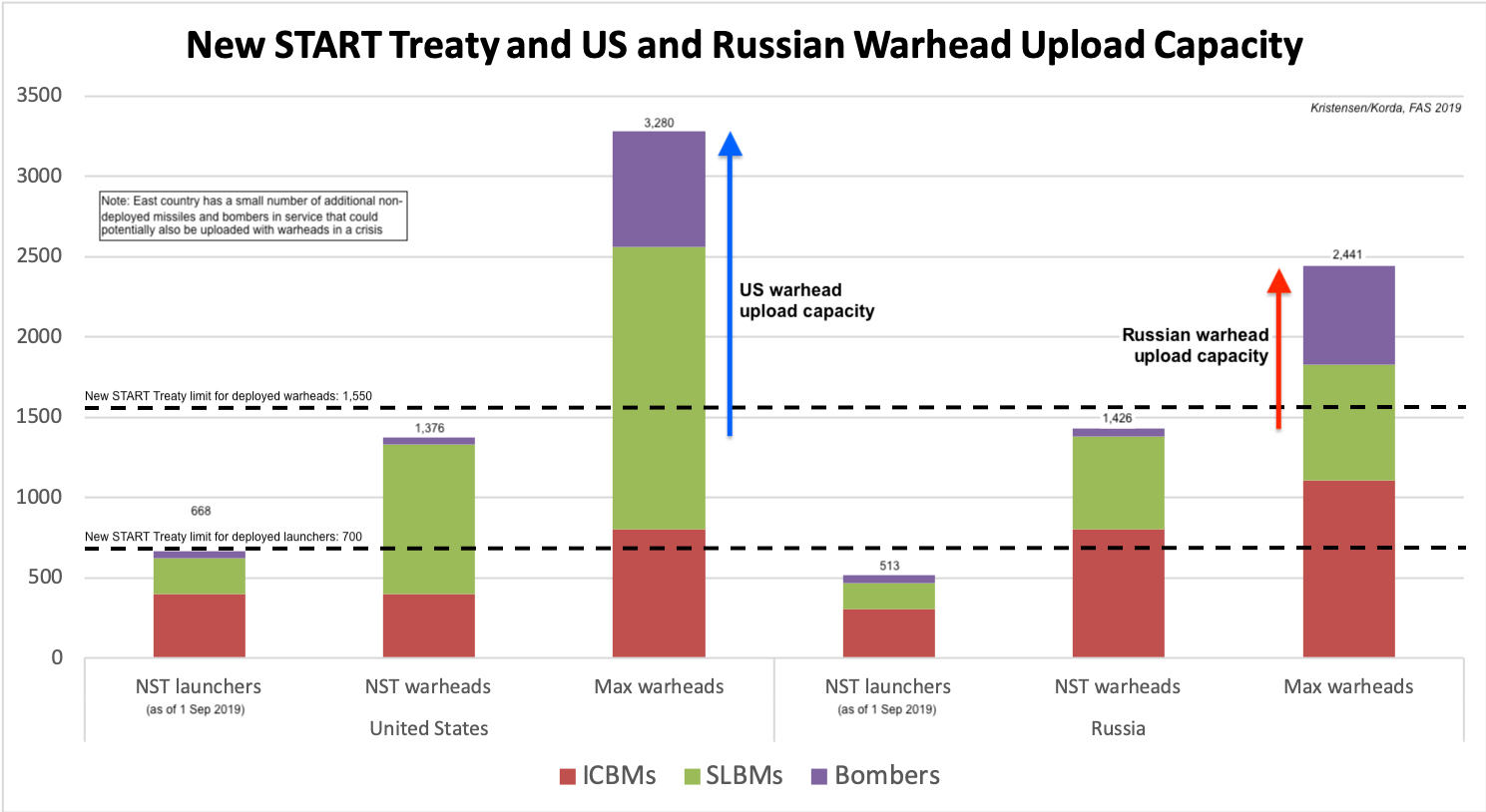

In their effort to paint the New START treaty as insufficient and a bad deal for the United States and its allies, Trump administration official have recently made statements suggesting the treaty limits the US nuclear arsenal more than it limits the Russian arsenal.

New START imposes the same restrictions on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces.

During a virtual conference organized by the Heritage Foundation on October 13, Marshall Billingslea, special presidential envoy for arms control, stated: “What we’ve indicated to the Russians is that we are in fact willing to extend the New START Treaty for some period of time provided that they agree to a limitation, a freeze, in their nuclear arsenal. We’re willing to do the same. I don’t see how it’s in anyone’s interests to allow Russia to build up its inventory of these tactical nuclear weapons systems with which they like to threaten NATO…We cannot agree to a construct that leaves unaddressed 55 percent or more of the Russian arsenal.”

One week later, in an interview on National Public Radio, Billingslea added: “The New START treaty constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent” but “only covers 45 percent or less of the Russian arsenal…”

Finally, on October 21, Secretary of State Michal Pompeo repeated this talking point: “President Trump has made clear that the New START Treaty by itself is not a good deal for the United States or our friends or allies. Only 45 percent of Russia’s nuclear arsenal is subject to numerical limits, posing a threat to the United States and our NATO allies. Meanwhile, that agreement restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits contained in the New START agreement.”

Pompeo and Billingslea didn’t specify what they meant by “arsenal” and the reaction from nuclear weapons analysts – ourselves included – was bewilderment. Most assumed “arsenal” was referring warheads, but the numbers don’t seem to fit with the percentages and descriptions in the statements. Interestingly, the percentages and categories seem to work better for launchers, unless one does a back-of-the-envelope calculation.

Matching Comparison With Warheads

Our first step was to analyze the statements and see if we could make them fit with our understanding of the size and composition of the nuclear arsenals. If we assume the percentages and descriptions refer to warhead numbers, then we see the following potential options:

Option 1: The 45% refers to New START warhead limit for deployed strategic warheads (1,550). If this were the case, then Russia’s entire stockpile would only consist of 3,445 warheads, which we doubt. Our estimate is 4,310. For the United States, 1,550 would only constitute 41% of the US stockpile, not 92% as stated by Billingslea.

Option 2: The 45% refers to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto ICBMs and SLBMs but not bomber weapons. New START counts actual numbers of warheads on deployed ICBMs and SLBMs, but not those on bomber bases. According to our estimate of Russian forces, their ICBMs can load 1,136 warheads and SLBMs can load 720 warheads, a total of 1,856 warheads. That would constitute 43% of the total stockpile of 4,310 warheads (our estimate). It would of course be embarrassing if the US officials have been using our numbers instead of those of the US Intelligence Community. Even so, that methodology does not fit with the 92% comparison used for the United States. US ICBMs and SLBMs can load a maximum of 2,720 warheads, by our estimate, or 72% of the stockpile. And Billingslea explicitly says the US comparison includes the “entire” arsenal.

Option 3: The 45% refers to the total number of strategic warheads in the Russian arsenal (deployed and non-deployed). If that were the case, then the remaining 55% of 3,025 warheads would be non-strategic warheads, far more than the “up to 2,000” stated in the Nuclear Posture Review. And it would imply a total stockpile of 5,500 warheads, far more than the number of warhead spaces on launchers.

Option 4: The percentage numbers come from a simplistic back-of-the-envelope calculation. The Russian 45% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 2,000 (tactical). The US 92% is 1,550 (New START limit) / 1,550 (reserve) + 150 (tactical). Those numbers don’t fully match the stockpiles and statements but can explain the comparison. (We are indebted to Pavel Podvig for suggesting this option.)

Billingslea and Pompeo both compared the Russian restrictions to those affecting the US arsenal, but they described it differently.

Billingslea said New START “constraints…92 percent of the entire U.S. arsenal, of our deterrent…” (emphasis added). Since we know the approximate size of the total US stockpile (about 3,800 warheads), 92% would constitute 3,496 warheads, far more than the treaty’s limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads. But the count would be close to the number of strategic warheads that can be loaded onto strategic launchers (3,570 by our estimate), leaving about 300 non-strategic warheads.

Pompeo said that New START “restricts 92 percent of America’s arsenal that is subject to the limits” (emphasis added), which is different than what Billingslea said because it doesn’t appear to include non-deployed strategic warheads or tactical warheads, two categories that are not subject to the treaty limits.

Matching Comparison With Launchers

Our next step was to analyze the statements to see how they compare with the number of launchers that can deliver nuclear warheads. New START limits both sides to no more than 800 strategic launchers in total, of which no more than 700 can be deployed at any given time.

In the latest set of aggregate numbers released by the US State Department, the United States is listed with exactly 800 launchers in total, of which 675 are deployed. Russia is listed with a total of 764 launchers, of which 510 are deployed.

While complaining about limits on US and Russian weapons, neither Billingslea nor Pompeo mentions this US strategic advantage of 165 deployed launchers, a number that exceeds the number of Minuteman IIIs in one missile wing and corresponds to more than half of the entire Russian ICBM force.

For the United States, if the 800 total strategic launchers constitute 92% of all US nuclear launchers (“entire” arsenal), then that would imply the existence of another 70 launchers, which potentially could refer to non-strategic fighter-bombers assigned missions with gravity bombs.

For Russia, if the 764 total strategic launchers constitute 45% of all its nuclear launchers, that would potentially imply that Russia has 1,698 total nuclear launchers, of which 934 would be launchers of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

We don’t yet know if this is the case. But the percentages mentioned by Billingslea and Pompeo appear to fit better if they refer to launchers than warheads, unless one applies the Option 4 calculation described above. The Trump administration has been particularly critical about Russia’s development of new types of strategic-range weapons that are not covered by the New START treaty, just like it has criticized that Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are not covered by any arms control agreement.

Context and Recommendations

The comparisons and descriptions of Russian and US nuclear forces presented by Billingslea and Pompeo are confusing. Some might suspect “fuzzy math” but until we see otherwise, we suspect the comparisons use real data. Option 4 above might represent the most likely explanation although it doesn’t fully match the stockpiles and descriptions provided by the officials.

When it comes to nuclear negotiations, it is incredibly important to be precise with official words and statements, in order to avoid misunderstandings or mischaracterizations. Unfortunately, the Trump administration has a habit of cherry-picking or spinning statistics in an apparent attempt to make existing and equitable arms control agreements seem like “bad deals” for the United States. Given this track record, we should view their statements here with skepticism and ask for clarification if they’re referring to warheads or launchers. We have done so but have not yet heard back from the State Department.

A one-year extension of New START is better than no extension, but it’s worse than a five-year extension because it creates uncertainty about the commitment to continue to limit force levels and unnecessarily shortens the time available to negotiate follow-on arrangements. There is no technical need to shorten the extension. If a new deal is made, the old one will fall away.

A freeze on warheads would be a welcoming new step and Russia’s acceptance of the idea is a breakthrough because it opens up possibilities for building on this idea in the future. But a freeze will not have much credibility or effect without verification and despite saying it would like “portal monitoring” the Trump administration has not presented a plan for how this would work or secured Moscow’s agreement. Verification of a total warhead freeze would be much more complex than verifying the New START treaty itself and one year may not be sufficient to do the work. Has the US military and intelligence community signed off on Russian inspectors monitoring every US warhead moving in and out of facilities? Have US allies in Europe agreed to allow Russian officials to monitor the bases where the US Air Force stores nuclear bombs?

Russia’s acceptance of a one-year New START extension and a declaration to freeze warhead levels is a significant compromise from its previous offer to unconditionally extend the treaty by five years with no warhead freeze.

The Trump administration’s “offer” of a one-year extension of New START and a one-year warhead freeze with no verification at the outset represents an astounding walk-back from its previous statements. Trump has repeatedly called New START a “bad deal” and the whole point of the talks was to “fix” what the administration claimed was inadequate verification, incorporate Russia’s new strategic weapons into the agreement, and get China onboard. And how many times have we heard that you can’t trust Russia because they violate every arms control agreement they have signed? Yet here we are. None of those “fixes” are attached to the one-year treaty extension and the administration now says it is willing to sign on to a warhead freeze without agreed verification measures with the Great Cheater.

There is nothing wrong with trying to broaden arms control to other weapons categories and countries. We strongly support that. But the last-minute flurry and attempts to shorten extension strongly suggest that the Trump administration has been more focused on creating chaos and to appear tough on Moscow and Beijing than to create nuclear arms control progress. The one-year timeline unnecessarily constrains both countries and could well mean that they would be in pretty much the same situation one year from now.

The inconvenient fact is that New START is working as designed and keeps the vast majority of Russian and US strategic arsenals in check, prevents either country from uploading thousands of extra warheads onto their deployed missiles, and offers a modicum of predictability in an otherwise unpredictable world.

Additional background information:

- Status of world nuclear forces, September 2020

- United States nuclear forces, 2020

- Russian nuclear forces, 2020

- At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

At 11th Hour, New START Data Reaffirms Importance of Extending Treaty

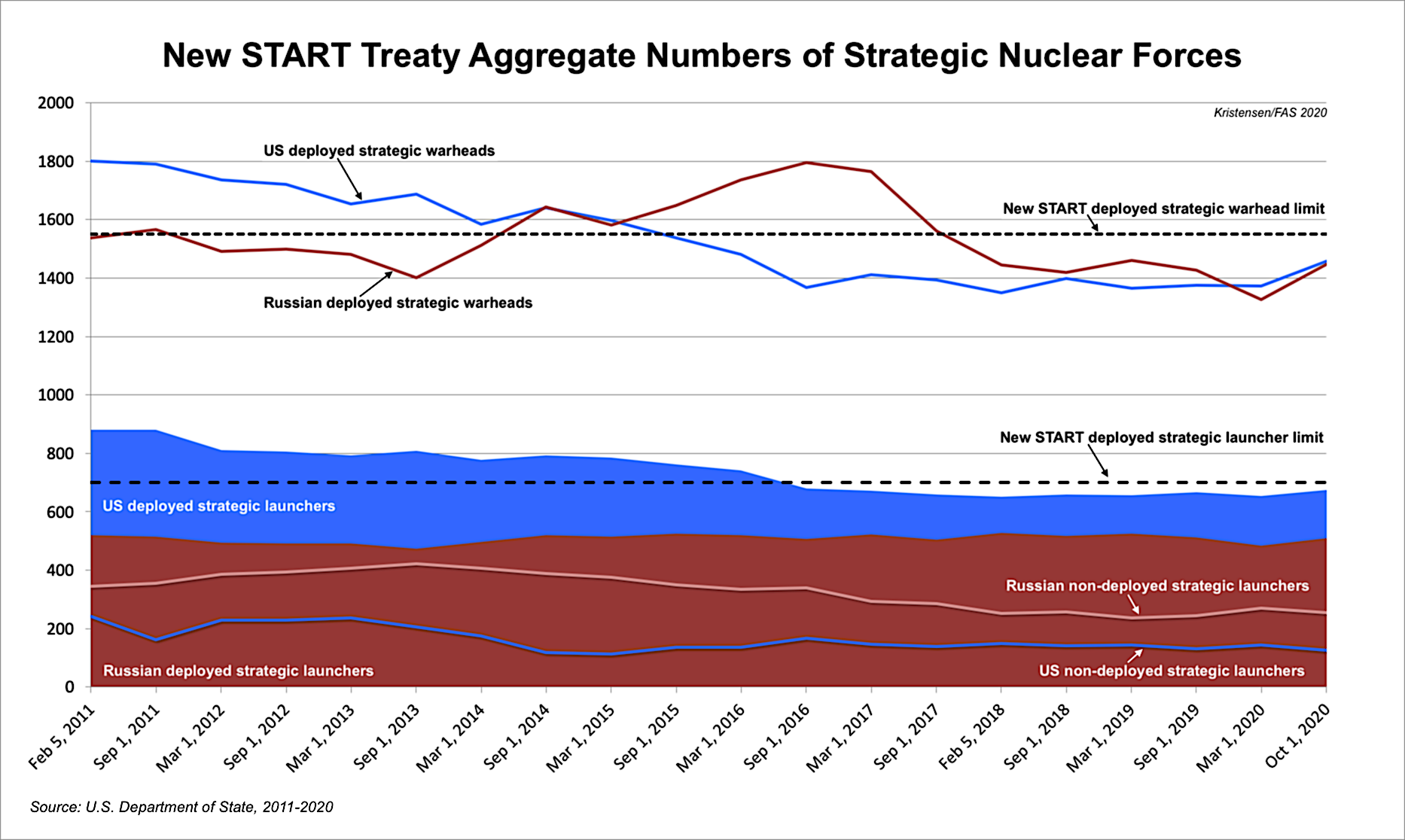

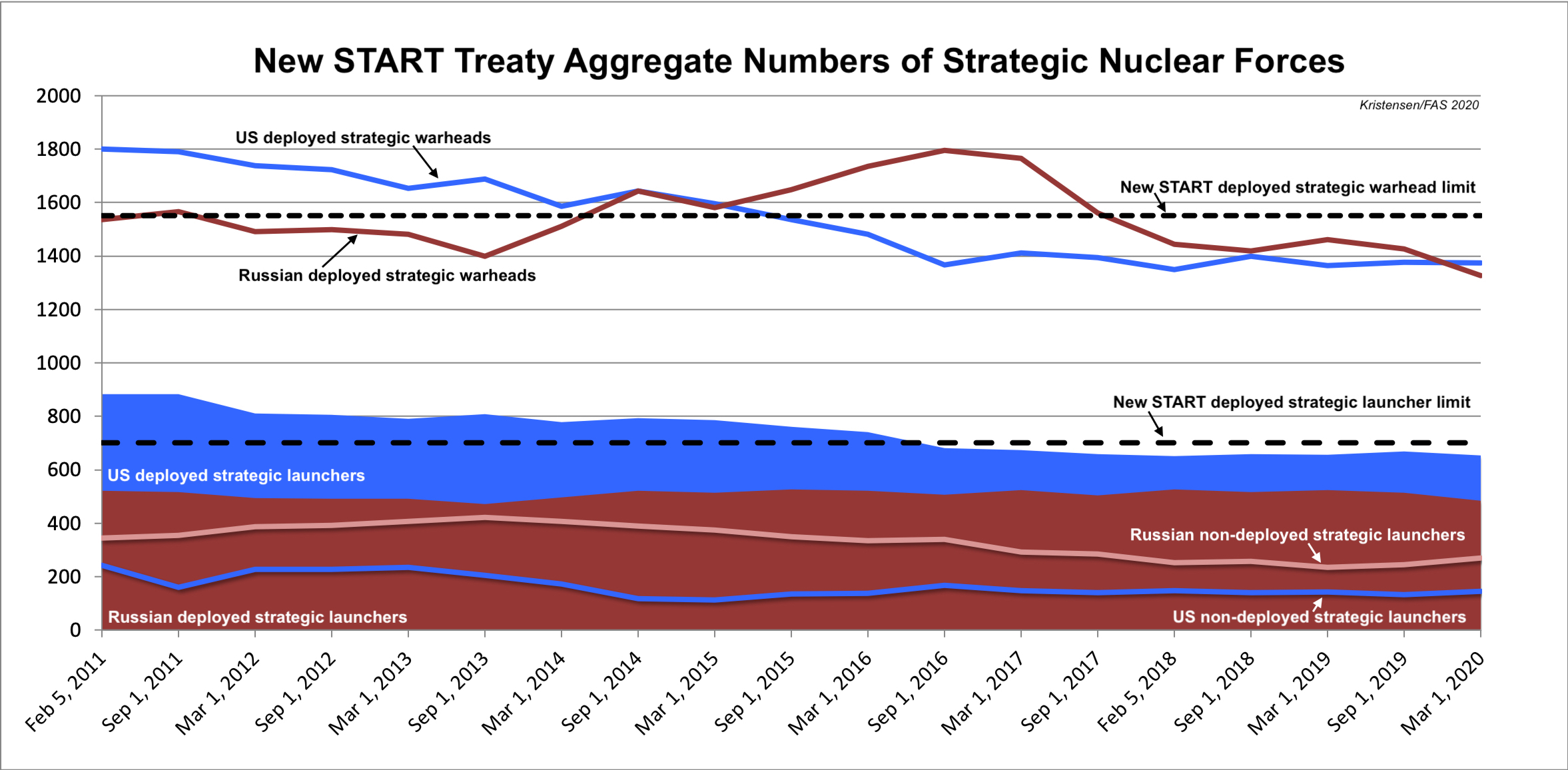

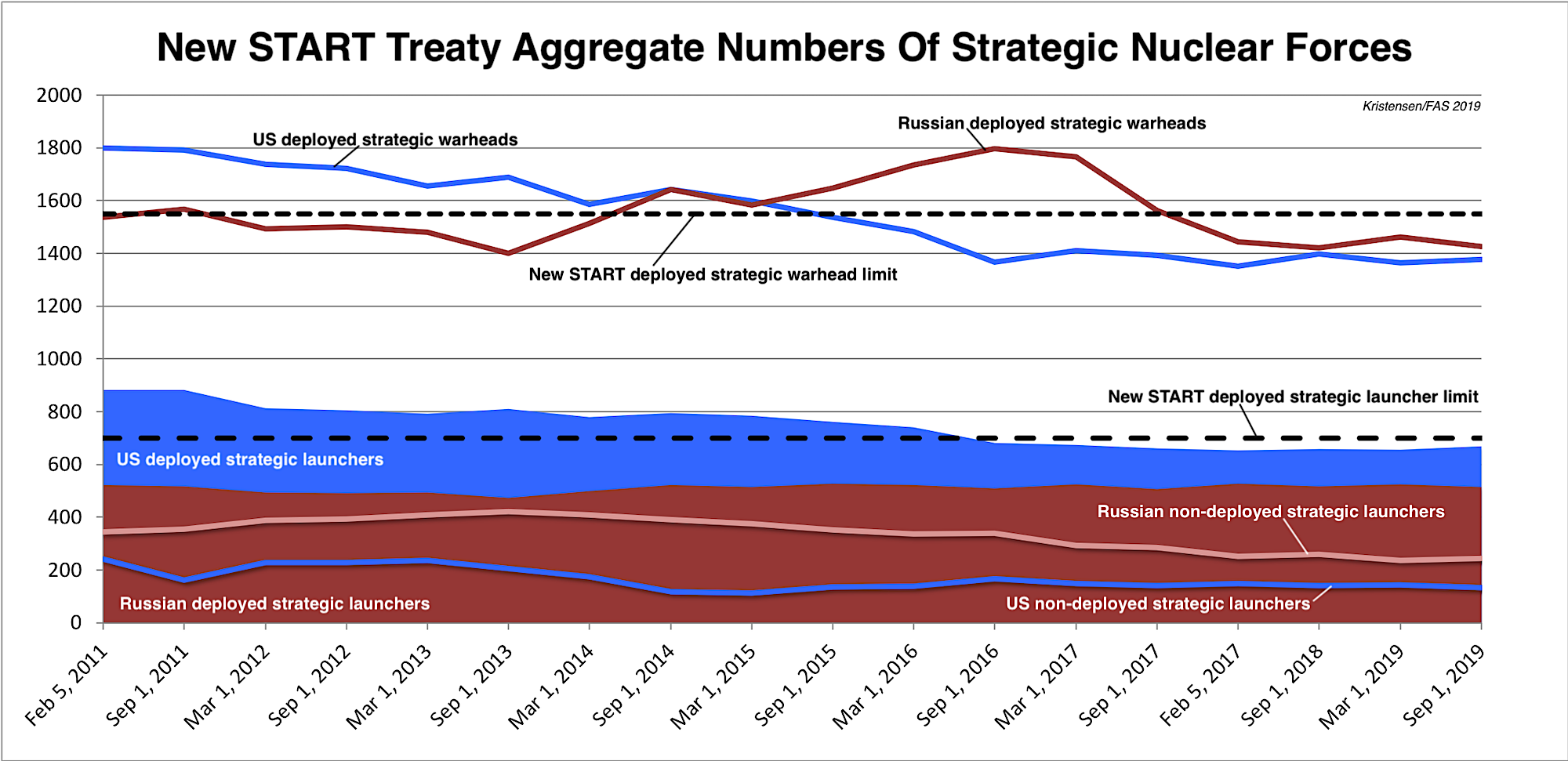

Just four months before the New START treaty is set to expire, the latest set of so-called aggregate data published by the State Department shows the treaty is working and that both countries – despite tense military and political rhetoric – are keeping their vast strategic nuclear arsenals within the limits of the treaty.

The treaty caps the number of long-range strategic missiles and heavy bombers the two countries can possess to 800, with no more than 700 launchers and 1,550 warheads deployed. The treaty entered into force in February 2011, into effect in February 2018, and is set to expire on February 5, 2021 – unless the two countries agree to extend it for an additional five years.

Twice a year, the two countries have exchanged detailed data on their strategic forces. Of that data, the public gets to see three sets of numbers twice a year (1 March and 1 October): the aggregate data of deployed launchers, warheads attributed to those launchers, and total launchers. This time, the web-version helpfully includes the full data set (including a breakdown of US forces; it would be helpful is Moscow could also publish its breakdown) but the PDF-version does not.

This is the final set of periodic six-month aggregate data to be released, although a final set will probably be released if the treaty expires in February. If the treaty is extended for another five years, an additional ten data sets would probably be released.

The nearly ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of October 1, 2020. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,564 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,185 launchers were deployed with 2,904 warheads. That is a slight increase in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with March 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 10, increased combined deployed strategic launchers by 45, and increased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 205. Of these numbers, only the “10” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 have cut 425 strategic launchers from their combined arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 218, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 433. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (less than 6 percent) of the estimated 8,110 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (less than 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 12,170 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, the maximum number allowed by the treaty, of which 675 are deployed with 1,457 warheads attributed to them. This is an increase of 20 deployed strategic launchers and 84 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual increases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The warhead numbers are interesting because they reveal that the United States now deploys 1,009 warheads on the 220 deployed Trident missiles on the SSBN fleet. That’s an increase of 82 warheads compared with March and the first time since 2015 that the United States has deployed more than 1,000 warheads on its submarines, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for nearly 70 percent of all the 1,457 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 72 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data reveals that the United States as of October 1, 2020 deployed over 1,000 warheads on its fleet of ballistic missile submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 207, and deployed strategic warheads by 343. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 9 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 6 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 764 strategic launchers, of which 510 are deployed with 1,447 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 25 deployed launchers and 121 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 101, deployed launchers by 11, and deployed strategic warheads by 90. This modest warhead reduction represents about 2 percent of the estimated 4,310 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (not even 3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,370 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials and nuclear weapons advocates that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 165 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap that exceeds the size of an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by one-third since its lowest point in February 2018. One factor that could change this is if the Trump administration kills New START and Russia believes the threat made by Marshall Billingslea, the Trump administration’s Special Presidential Envoy for Arms Control, that the United States might increase its nuclear forces if New START expires.

The New START data shows that Russia’s nuclear modernization program has not been trying increase the number of launchers despite a sizable gap compared with the US arsenal.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher gap by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles that are replacing older types (Yars and Bulava). Many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance, however, but stored and could potentially be uploaded onto launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (Avangard and Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types, which have become a sticking point for the Trump administration, are in relatively small numbers (if they have even been deployed yet) and do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types.

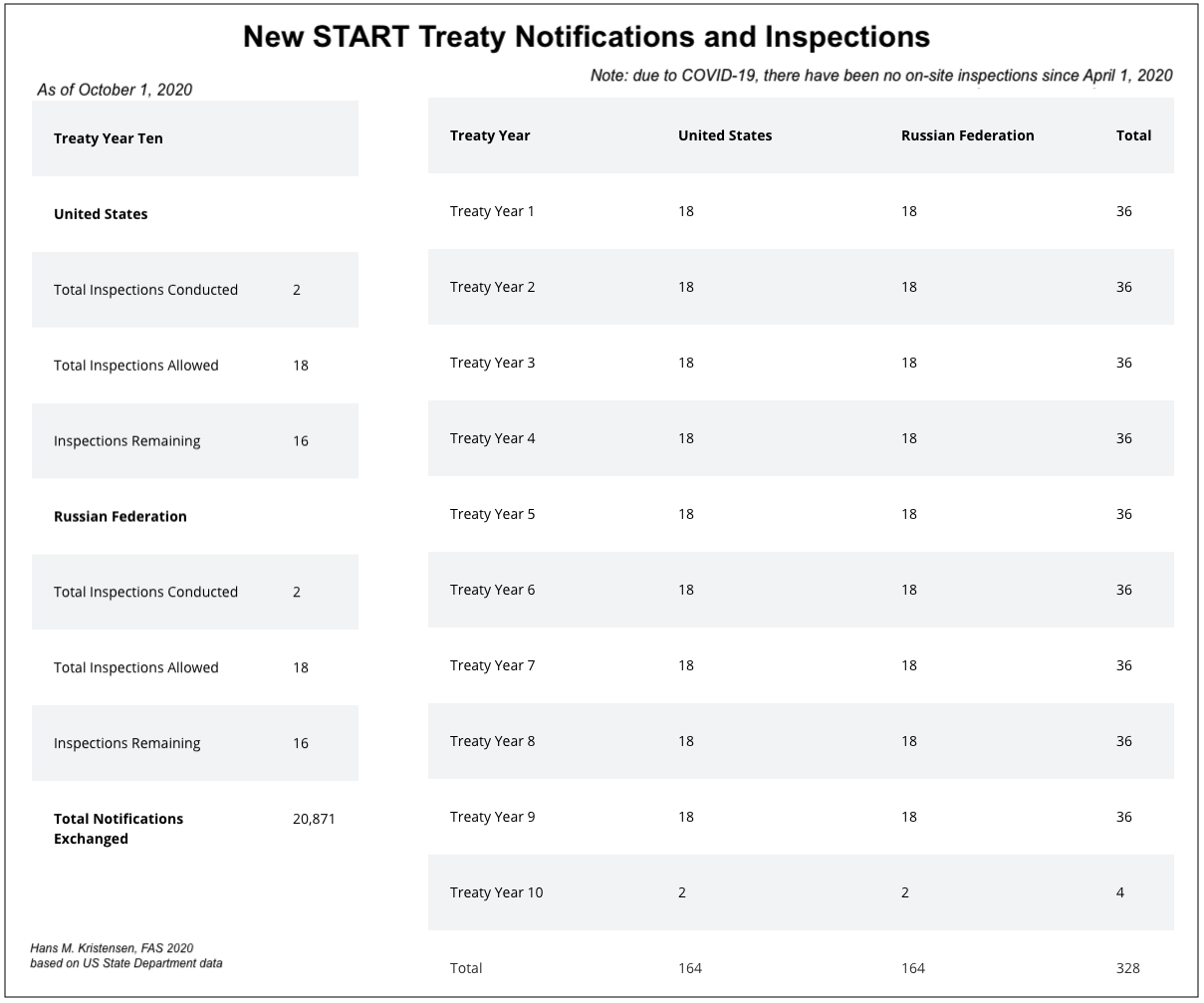

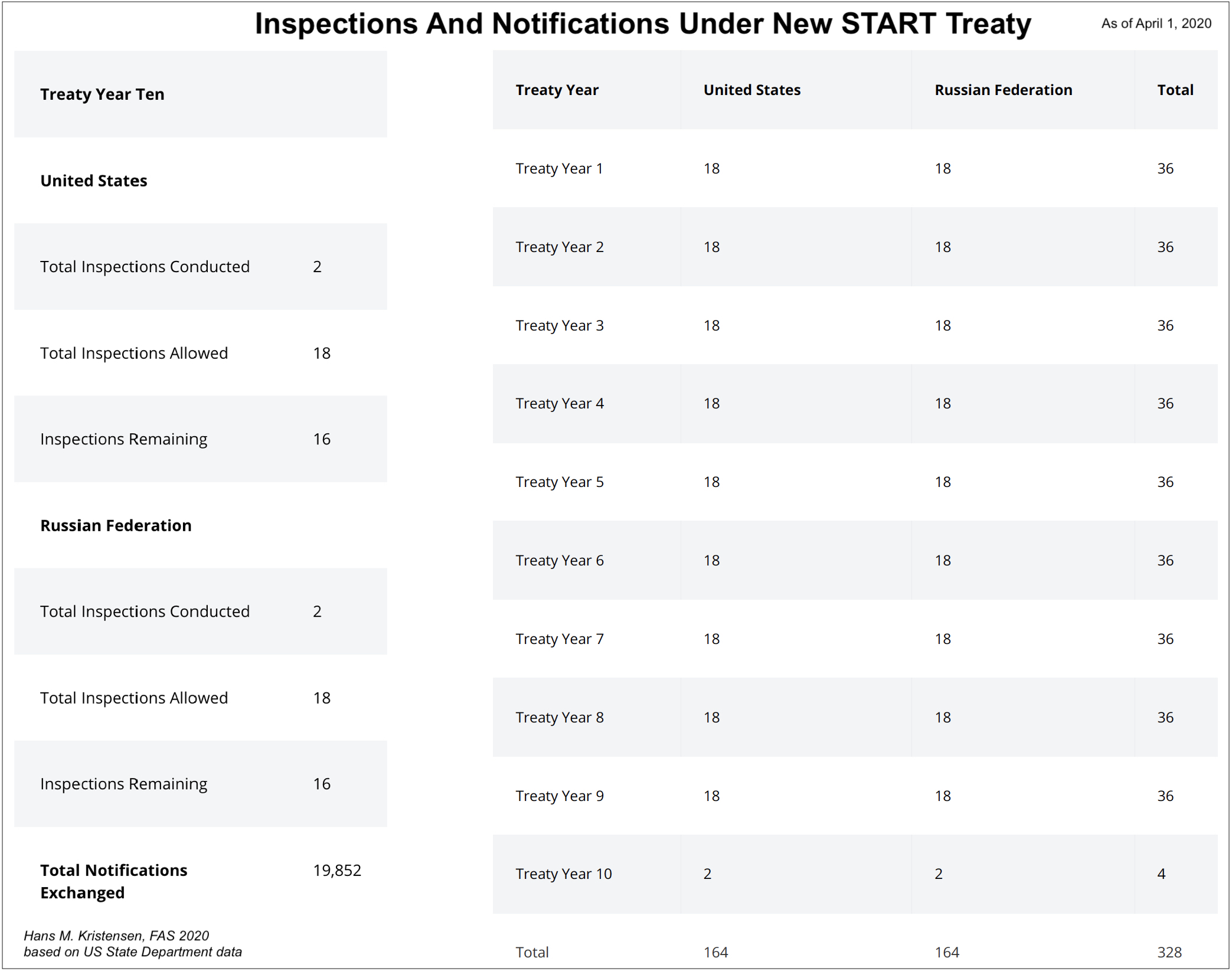

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 20,871 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 1,200 of those notifications were exchanged since March 5, 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Treaty opponents might use this to argue that compliance with the treaty cannot be determined or that it shows it’s irrelevant. Both claims would be wrong because National Technical Means of verification also provide insight to activities on the ground, but that on-site inspections provide valuable additional data.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for US-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

The 11th Hour

Time is now quickly running out for New START with only a little over four months remaining before the treaty expires on February 5, 2021. Rather than working to secure extension, the Trump administration instead has introduced last-minute conditions that threaten to derail extension.

Russia and the United States can and should extend the New START treaty as is by up to 5 more years. Once that is done, they should continue negotiations on a follow-on treaty with additional limitations and improved verification. It is essential both sides act responsibly and do so to preserve this essential cornerstone of strategic stability.

The fact that Marshall Billingslea has already threatened to increase US nuclear forces if Russia doesn’t agree to the US conditions for extending the treaty only reaffirms how important New START is for keeping a lid on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces and for providing transparency and predictability on the status and plans for the arsenals.

Additional background information:

Status of world nuclear forces, September 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Construction of New Underground Nuclear Warhead Facility At Warren AFB

Construction has begun of a new nuclear weapons storage facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base. Click on image to view full size

The Air Force has begun construction of a new underground nuclear weapons storage and handling facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The new Weapons Storage and Maintenance Facility (WSMF; sometimes called Weapons Generation Facility), which will replace the current Weapons Storage Area (WSA), will be a 90,000-square-foot reinforced concrete and earth-covered facility with supporting surface structures.

A satellite image taken in August and obtained from Maxar shows construction is well underway of the underground facility as well as several supporting facilities.

The Air Force says the new facility “will provide a safer and more secure facility for the storage of U. S. Air Force (USAF) assets,” a reference to W78/Mk12A and W87/Mk21 warheads for the Minuteman III ICBMs deployed in Warren AFB’s 150 missile silos. In the future, if Congress agrees to fund it, the new W87-1 warhead will replace the W78. According to the Air Force:

“The primary interior walls of Maintenance and Storage Area are 4-foot thick reinforced concrete (RC) elements with 4-foot thick RC roof slabs. The primary wall and roof elements are surrounded by a 20-foot thick soil layer which is contained by a 3-foot thick RC wall and roof element layer. The heavy multilayered system sits on a 5-foot thick RC structural mat for support.”

The $144 million contract was awarded to Fluor Corporation by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2018. The ground-breaking ceremony took place on May 21, 2019 but substantial construction (of buildings) did not begin until the Spring of 2020. The president of Flour’s Government Group is Tom D’Agostino, who previously served as the undersecretary for nuclear security at the Department of Energy, administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), and deputy administrator for defense programs. Construction was scheduled to take 40 months and be completed in 2022.

Construction of the underground storage facility at F.E. Warren AFB follows the completion in 2012 of a massive underground nuclear weapons storage facility at the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC) next to the Kitsap Naval Submarine Base. Underground storage facilities are also planned at other bases.

(The Other) Red Storm Rising: INDO-PACOM China Military Projection

Click on image to download PDF-version of full briefing

Some Missile Numbers Do Not Match Recent DOD China Report

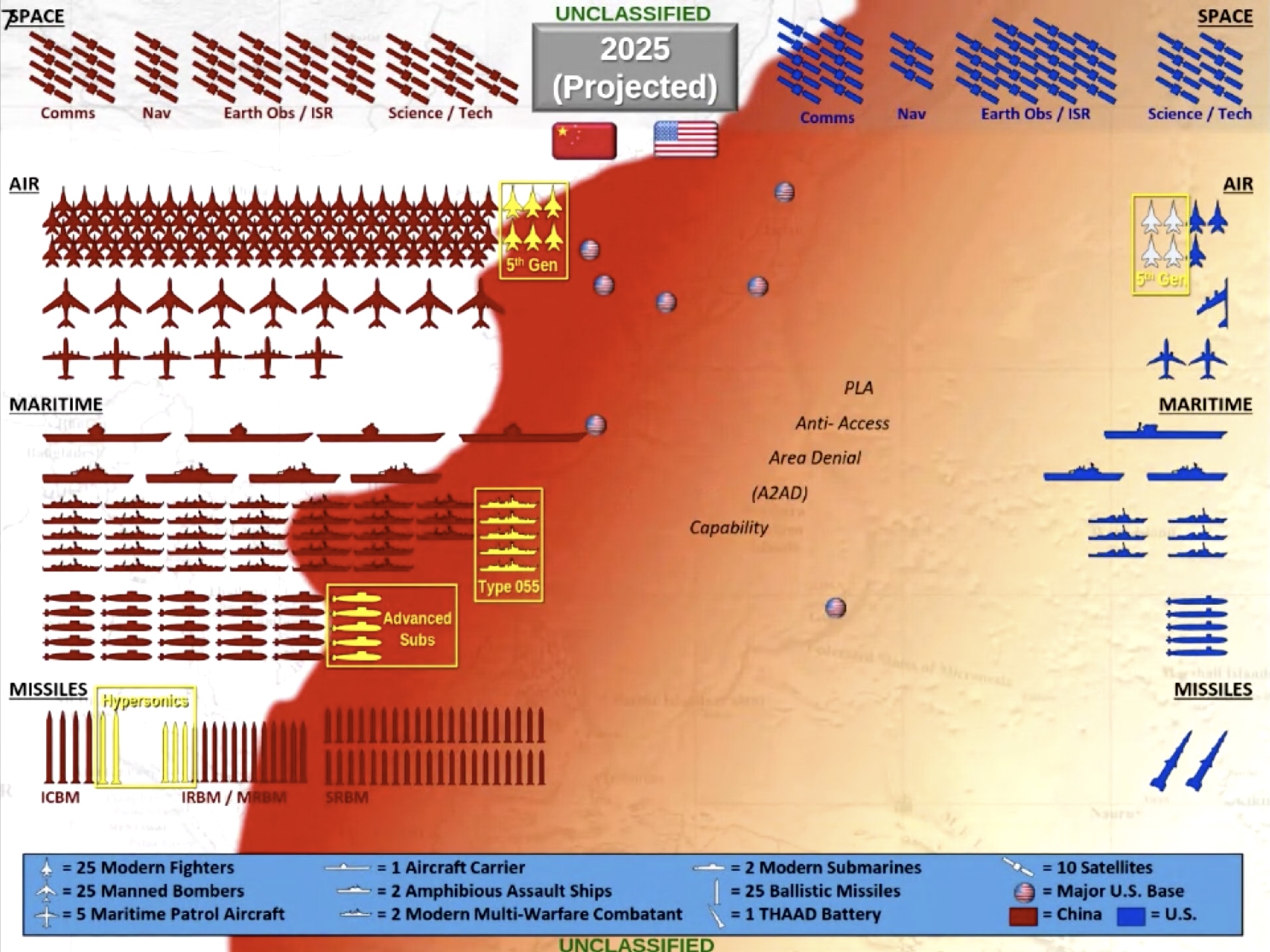

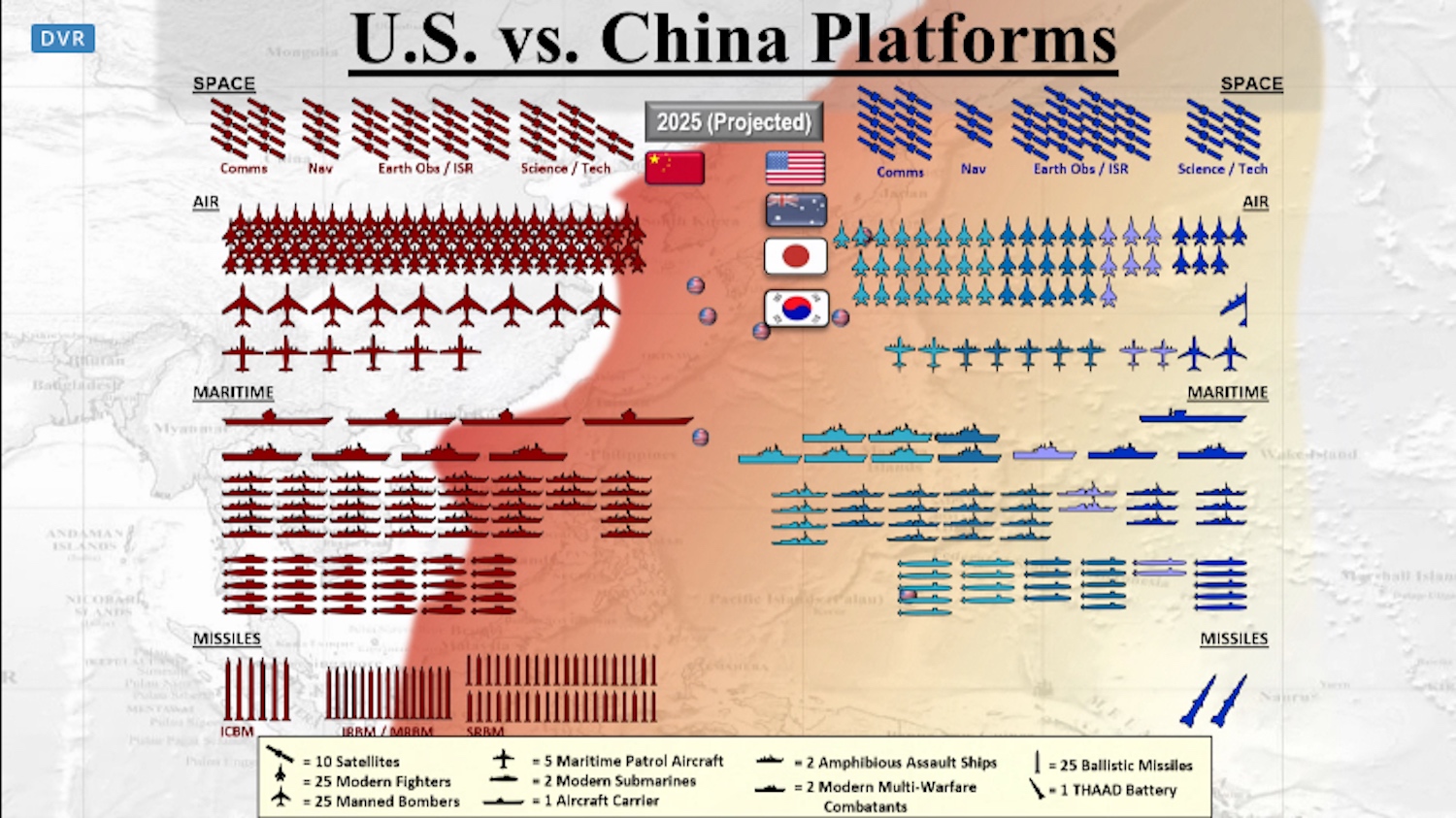

U.S. Indo-Pacific Command recently gave a briefing about the challenges the command sees in the region. The briefing says China is the “Greatest Threat to Global Order and Stability” and presents a set of maps that portray a massive Chinese military buildup and very little U.S. capability (and no Allied capability at all) to counter it. With its weapons icons and a red haze spreading across much of the Pacific, the maps resemble a new version of the Cold War classic Red Storm Rising.

Unfortunately, the maps are highly misleading. They show all of China’s forces but only a fraction of U.S. forces operating or assigned missions in the Pacific.

There is no denying China is in the middle of a very significant military modernization that is increasing its forces and their capabilities. This is and will continue to challenge the military and political climate in the region. For decades, the United States enjoyed an almost unopposed – certainly unmatched – military superiority in the region and was able to project that capability against China as it saw fit. The Chinese leadership appears to have concluded that that is no longer acceptable and that the country needs to be able to defend itself.

In describing this development, however, the INDO-PACOM briefing slides make the usual mistake of overselling the threat and under-characterizing the defenses. Moreover, some of the Chinese missile forces listed in the briefing differ significantly from those listed in the recent DOD report on Chinese military developments. As military competition and defense posturing intensify, expect to see more of these maps in the future.

Apples, Oranges, and Cherry-Picking

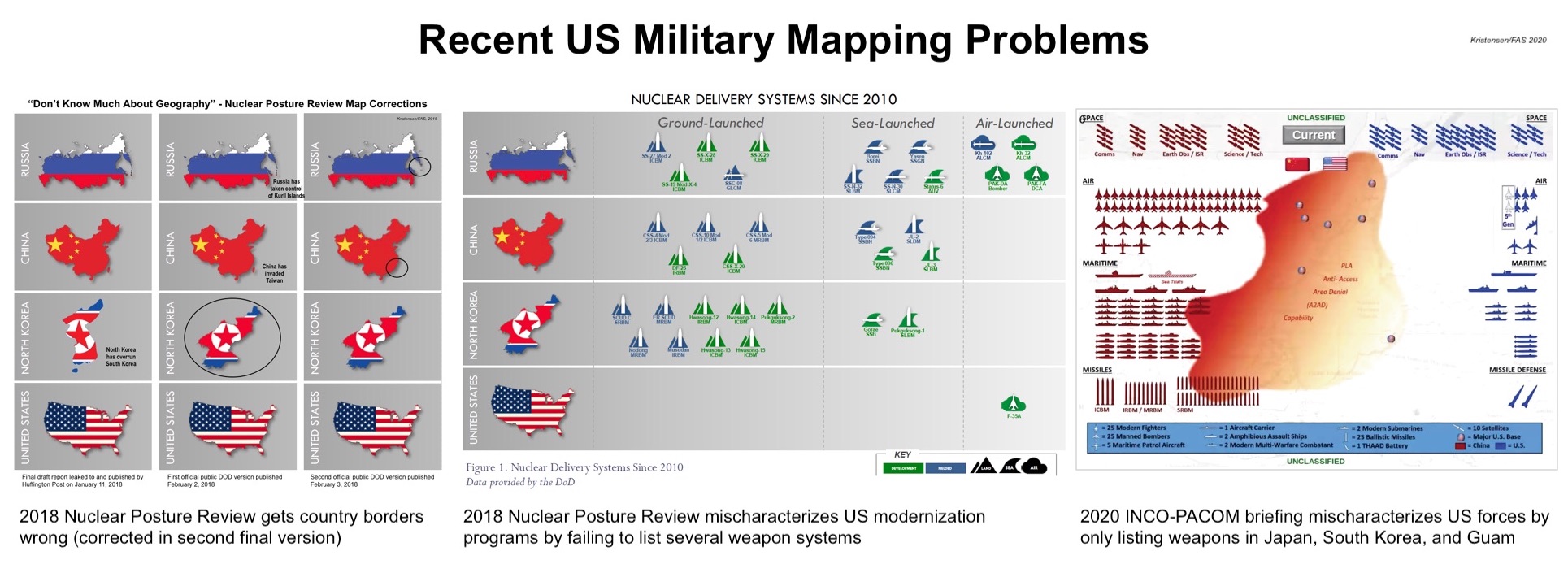

The INDO-PACOM maps suffer from the same lopsided comparison and cherry-picking that handicapped the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review: it overplays the Chinese capabilities and downplays the U.S. capabilities (see image below). While he briefing maps includes all of China’s military forces, whether they are postured toward India or Russia, it only shows a small portion of U.S. forces. INDO-PACOM mapmakers may argue that it’s only intended to show the force level in the Western Pacific theater, but INDO-PACOM spans all of the Pacific and the maps ignore other significant U.S. forces that are operating in the region to oppose China.

The INDO-PACOM map gives the impression that the United States only has 175 fighter-jets, 12 bombers, 50 maritime patrol aircraft, 1 aircraft carrier, four amphibious assault ships, 12 modern multi-warfare warships, 10 submarines, and 2 THAAD missile defense batteries in the region to deter China. In reality, the U.S. military forces based or assigned missions in the INDO-PACOM area of responsibility are significantly greater. The map excludes everything based in Hawaii, in Alaska, on the U.S. west coast, and elsewhere in the continental United States with missions in the Pacific or forces rotating through bases in the Indo-Pacific region. Examples of mischaracterizations of U.S. forces include:

Fighter aircraft: The map lists only lists 175 fighter-jets, but Pacific Air Forces says it has “Approximately 320 fighter and attack aircraft are assigned to the command with approximately 100 additional deployed aircraft rotating on Guam.”

Bombers: The map lists only 12 bombers, but the United States has more than 150 bombers, many of which would be used to counter Chinese forces in a war. Moreover, those bombers are considerably more capable than Chinese bombers and are supported by tankers to provide unconstrained range in the Pacific, something Chinese bombers cannot do.

Submarines: The map lists only 10 U.S. submarines, but according to the U.S. Naval Vessel Register the U.S. Navy has more than three times that many (35) in the Pacific, including 25 attack submarines, 2 guide missile submarines, and 8 ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) homeported in Pacific ports. The omission of the 8 Pacific-based SSBNs is particularly problematic given their important role of targeting China – and that they are assigned up to eight times more nuclear warheads than China has in its entire nuclear weapons stockpile.

The INDO-PACOM briefing does not show that the United States has any ballistic missile submarines in the Pacific, even though eight U.S. Pacific-based SSBNs play a central role in targeting China. Just two of these Ohio-class SSBNs can carry more warheads than China has in its entire nuclear stockpile. This image shows the USS Pennsylvania (SSBN-735) during a port visit to Guam in 2016.

Aircraft carriers: The map lists only one U.S. aircraft carrier, but according to the U.S. Naval Vessel Register the U.S. Navy has six aircraft carriers based in the Pacific (two of them in shipyard). Moreover, unlike China’s single aircraft carrier (a second is fitting out), U.S. carriers are large flat-tops with more aircraft.

Amphibious assault ships: The map shows four U.S. amphibious assault ships, but the U.S. Pacific Fleet says it operates six (although one was recently damaged by fire). Moreover, the amphibious assault ships are being upgraded to carry the F-35B VSTOL aircraft, significantly improving their strike capability.

Missile defense: The map shows only two THAAD batteries but does not mention the Ground Based Midcourse missile defense system in Alaska. Nor are missile defense interceptors deployed on cruisers and destroyers listed.

ICBMs: One of the most glaring omissions is that the maps do not show the United States has any ICBMs (the map also does not list U.S. SLBMs but nor does it list Chinese SLBMs). Although U.S. ICBMs are thought to be mainly assigned to targeting Russia and would have to overfly Russia to reach targets in China, that does not rule out they could be used to target China (Chinese ICBMs would also have to overfly Russia to target the continental United States). U.S. ICBMs carry more nuclear warheads than China has in its entire nuclear stockpile.

The INDO-PACOM briefing shows China with 100 ICBMs and the United States with none. This infrared image shows a U.S. Minuteman III ICBM test-launched from Vandenberg AFB into the Pacific on September 2, 2020.

A modified map, apparently made available by U.S. Pacific Air Forces, is a little better because it includes Australian, Japanese, and South Korean forces. But it still significantly mischaracterizes the forces the United States has in the Pacific or are assigned missions in the region. Moreover, the new map does not include the yellow highlights showing “hypersonics” missiles and portion of aircraft, ships, and submarines that are modern (see modified map below).

A modified map released after the INDO-PACOM briefing also shows Australian, Japanese, and South Korean forces – but still mischaracterizes U.S. military forces in the Pacific.

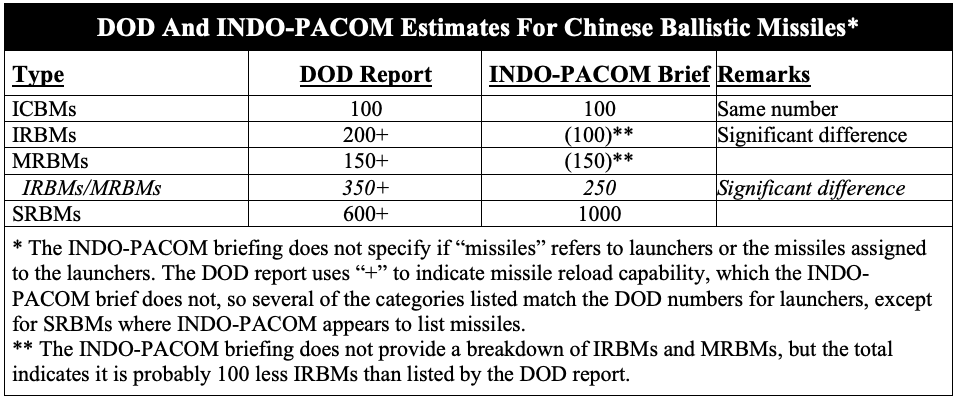

Inconsistent Missile Numbers

The INDO-PACOM maps are also interesting because the numbers for Chinese IRBMs and MRBMs are different than those presented in the 2020 DOD report on Chinese military developments. INDO-PACOM lists 250 IRBMs/MRBMs, more than 100 missiles fewer than the DOD estimate. China has fielded one IRBM (DF-26), a dual-capable missile that exists in two versions: one for land-attack (most DF-26s are of this version) and one for anti-ship attack. China operates four versions of the DF-21 MRBM: the nuclear DF-21A and DF-21E, the conventional land-attack DF-21C, and the conventional anti-ship DF-21D.

There is also a difference in the number of SRBMs, which INDO-PACOM sets at 1,000, while the DOD report lists 600+. The 600+ could hypothetically be 1,000, but the INDO-PACOM number shows that the high-end of the 750-1,500 range reported by the 2019 DOD China report probably was too high.

A comparison (see table below) is complicated by the fact that the two reports appear to use slightly different terminology, some of which seems inconsistent. For example, INDO-PACOM lists “missiles” but the low IRBM/MRBM estimate suggests it refers to launchers. However, the high number of SRBMs listed suggest it refers to missiles.

Several of the Chinese missile estimates provided by INDO-PACOM and DOD are inconsistent.

2025 Projection

The projection made by INDO-PACOM for 2025 shows significant additional increases of Chinese forces, except in the number of SRBMs.

The ICBM force is expected to increase to 150 missiles from 100 today. That projection implies China will field an average of 10 new ICBMs each year for the next five years, or about twice the rate China has been fielding new ICBMs over the past two decades. Fifty ICBMs corresponds to about four new brigades. About 20 of the 50 new ICBMs are probably the DF-41s that have already been displayed in PLARF training areas, military parades, and factories. The remaining 30 ICBMs would have to include more DF-41s, DF-31AGs, and/or the rumored DF-5C, but it seems unlikely that China can add enough new ICBM brigade bases and silos in just five years to meet that projection.

The briefing also projects that 50 of the 150 ICBMs by 2025 will be equipped with “hypersonics.” The reference to “hypersonics” as something new is misleading because existing ICBMs already carry warheads that achieve hypersonic speed during reentry. Instead, the term “hypersonics” probably refers to a new hypersonic glide vehicle. It is unclear from the briefing if INDO-PACOM anticipates the new payload will be nuclear or conventional, but a conventional ICBM payload obviously would be a significant development with serious implications for crisis stability. Even if this expansion comes true, the entire Chinese ICBM force would only be one-third of the size of the U.S. ICBM force. Nonetheless, a Chinese ICBM force of 100-150 is still a considerable increase compared with the 40 or so ICBMs it operated two decades ago (see graph below).

The INDO-PACOM briefing appears to show a greater increase in ICBMs projected for the next five years than DOD reported in the past decade.

The IRBM/MRBM force is projected to increase to 375, from 250 today. That projection assumes China will field 125 additional missiles over five years, or 25 missiles each year. That corresponds to a couple of new brigades per year, which seems high. Yet production is significant and IRBM launchers have been seen in several regions in recent years. The IRBM/MRBM force presumably would include the DF-17, DF-21, and the DF-26.

About 75-87 of the IRBM/MRBM force will be equipped with “hypersonics” by 2025, according to INDO-PACOM. That projection probably refers to the expected fielding of the DF-17 with a new glide-vehicle payload, although that would imply a lot of the new launcher (enough for 4-6 brigades). Another possibly is that a portion of other IRBMs/MRBMs (perhaps the DF-26) might also be equipped with the new payload or have their own version. China has presented the DF-17 as conventional but STRATCOM has characterized it as a “new strategic nuclear system.” Adding new hypersonics to IRBMs/MRBMs that are already mixing nuclear and conventional seems extraordinarily risky and likely to further exacerbate the danger of misunderstandings.

The INDO-PACOM does not list any DF-17s but projects that 75-87 of China’s IRBMs/MRBMs by 2025 will carry some form of hypersonic payload that is different from what they carry today.

The status and projection for the surface fleet are also interesting. The INDO-PACOM briefing lists the total number of aircraft carriers, amphibious assault ships, and modern multi-warfare combatant vessels at 54, of which 46 are modern multi-warfare combatant vessels. The briefing doesn’t specify what is excluded from this count, but it differs significantly from the count in the DOD China report.

One of the puzzling parts of the INDO-PACOM briefing is the projection that China by 2025 will be operating four aircraft carriers for fixed-wing jets. China is currently operating one carrier with a second undergoing sea-trials. How China would be able to add another three carriers in five years is a mystery, not least because the third and fourth hulls are of a new and more complex design. The projection also doesn’t fit with the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, which predicts the third carrier won’t be commissioned until 2024.

The INDO-PACOM briefing says China will operate four aircraft carriers by 2025 but ONI estimates the third won’t be commissioned until 2024.

Bombers are projected to increase from 175 today to 225 in 2025, an increase of nearly 30 percent. Since 2025 is probably too early for the new H-20 to become operational, the increase appears to only involve modern version of the H-6 bomber. Although the bomber force has recently been reassigned a nuclear mission, the majority of the Chinese bomber force will likely continue to be earmarked for conventional missions.

Submarines and surface vessels will also increase and some of them are being equipped with long-range missiles. Combined with the growing reach of ground-based ballistic missiles and air-delivered cruise missiles, this results in the INDO-PACOM maps showing a Chinese “anti-access area denial” (A2AD) capability bleeding across half of the Pacific well beyond Guam toward Hawaii. But A2AD is not a bubble and weakens significantly in areas further from Chinese shores.

Conclusion and Recommendations

The INDO-PACOM maps project China’s military modernization will continue at a significant pace over the next five years with increases in delivery platforms and capabilities. This will reduce the military advantage the United States has enjoyed over China for decades and further stimulate modernization of U.S. and allied military forces in the region. As forces grow, operations increase, and rhetoric sharpens, insecurity and potential incidents will increase as well and demand new ways of reducing tension and risks.

The Trump administration is correct that China should be included in talks about limiting forces and reducing tension. So far, however, the administration has not presented concrete ideas for what that could look like. Like the United States, China will not accept limits on its forces and operations without something in return that Beijing sees as being in its national interest. Although China is modernizing its nuclear forces and appears intent on increasing it further over the next decade, the force will remain well below the level of the United States and Russia for the foreseeable future. Insisting that China should join U.S.-Russian nuclear talks seems premature and it is still unclear what the United States would trade in return for what. In the near-term, it seems more important to try to reach agreements on limiting the increase of conventional forces and operations.

Unfortunately, the INDO-PACOM briefing does a poor job in comparing Chinese and U.S. forces and suffers from the same flaw as the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review by cherry-picking and mischaracterizing force levels. It is tempting to think that this was done with the intent to play up the Chinese threat while downplaying U.S. capabilities to assist public messaging and defense funding. But the Chinese military modernization is important – as is finding the right response. Neither the public nor the Congress are served by twisted comparisons.

It would also help if the Pentagon and regional commands would coordinate and streamline their public projections for Chinese modernizations. Doing so would help prevent misunderstandings and confusion and increase the credibility of these projections.

Finally, these kinds of projections raise a fundamental question: why does the Pentagon and regional military commands issue public threat projections at all? That should really be the role of the Director of National Intelligence, not least to avoid that U.S. public intelligence assessments suffer from inconsistencies, cherry-picking, and short-term institutional interests.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

A Decade After Signing, New START Treaty Is Working

On this day, ten years ago, U.S. President Barack Obama and Russian President Dmitri A. Medvedev signed the New START treaty during a ceremony in Prague. The treaty capped the number of strategic missiles and heavy bombers the two countries could possess to 800, with no more than 700 launchers and 1,550 warheads deployed. The treaty entered into force in February 2011 and into effect in February 2018.

Twice a year, the two countries have exchanged detailed data on their strategic forces. Of that data, the public gets to see three sets of numbers: the so-called aggregate data of deployed launchers, warheads attributed to those launchers, and total launchers. Nine years of published data looks like this:

The latest set of this data was released by the U.S. State Department last week and shows the situation as of March 1, 2020. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,554 strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which

1,140 launchers were deployed with 2,699 warheads (note: the warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though bombers don’t carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2019, the data shows the two countries combined cut 3 strategic launchers, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 41, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 103. Of these numbers, only the “3” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

Compared with February 2011, the data shows the two countries combined have cut 435 strategic launchers, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 263, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 638. While important, it’s important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (less than 8 percent) of the estimated 8,110 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (less than 6 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 12,170 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, of which 655 are deployed with 1,373 warheads attributed to them. This is a reduction of 13 deployed strategic launchers and 3 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual reductions but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 227, and deployed strategic warheads by 427. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 11 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (a little over 7 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 764 strategic launchers, of which 485 are deployed with 1,326 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is a reduction of 28 deployed launchers and 100 deployed strategic warheads and reflects launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 111, deployed launchers by 36, and deployed strategic warheads by 211. This modest reduction represents less than 5 percent of the estimated 4,310 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (less than 4 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,370 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

The Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials and nuclear weapons advocates that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces.

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia now has 170 deployed strategic launchers fewer than the United States, a number that exceeds the size of an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. The Russian launcher deficit has been growing by more than one-third since the lowest point of 125 in February 2018.

The Russian military is trying to compensate for this launcher disparity by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on newer missiles replacing older types. Most of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but stored and could potentially be uploaded onto launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (Avangard and Sarmat) are covered by New START. Other types are in relatively small numbers and do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types.

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department also recently updated its overview of the status of the on-site inspections and notification exchanges that are part of the treaty’s verification regime.

Since February 2011, U.S. and Russian inspectors have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 19,852 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Four inspections happened this year before activities were temporarily halted due to the Coronavirus.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for U.S.-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

But time is now also running out for New START with only a little over 10 months remaining before the treaty expires on February 5, 2021.

Russia and the United States can extend the New START treaty by up to 5 more years. It is essential both sides act responsibly and do so to preserve this essential agreement.

See also: Count-Down Begins For No-Brainer: Extend New START Treaty

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Count-Down Begins For No-Brainer: Extend New START Treaty

One year from today, on February 5, 2021, the New START treaty will expire, unless the United States and Russia act to extend the last nuclear arms control agreement for an additional five years.

No matter your political orientation, treaty extension is a no-brainer – for at least six primary reasons.

1. New START keeps nuclear arsenals in check. If the treaty expires, there will be no constraints on US or Russian strategic arsenals for the first time since 1972. It would remove caps on how many strategic nuclear missiles and bombers the two sides can own and how many warheads that are carried on them. This means that Russia could quickly upload about a thousand new warheads onto its deployed missile arsenal–without adding a single new missile. The United States could upload even more because it has more missiles and bombers than Russia (see table below). And both sides could begin to increase their arsenals, risking a new nuclear arms race.

Both Russia and the United States have large warhead inventories that could be added to missiles and bombers if New START treaty expires. Click image to view full size

At a time when NATO-Russian relations are at their lowest since the end of the Cold War, when long-term predictability is more important than in the past three decades, allowing New START constraints to expire is obviously not in the US strategic interest or that of its allies. Very simply, New START is a good deal for both the United States and Russia; it cannot be allowed to expire without replacing it with something better.

2. New START force level is the basis for current nuclear infrastructure plans. Both the United States and Russia have structured their nuclear weapons and industry modernization plans on the assumption that the New START force level will continue, or at least not increase. If New START falls away, those assumptions and modernization plans will have to be revised, resulting in significant additional costs that neither Russia nor the United States can afford.

3. New START offers transparency and predictability in an unstable world. Under the current treaty, the United States receives a notification every time a Russian missile is deployed, every time a missile or bomber moves between bases, and every time a new missile is produced. Without these notifications, the United States would have to spend more money and incur significant risks to get the exact same information through National Technical Means (i.e. satellites and other forms of site monitoring). Russia benefits in the same way.

New START has forced Russia and the United States to reduce deployed strategic nuclear forces. Click image to view full size

Why would we willingly give all that up – to get absolutely nothing in return (and actually pay a steep price for giving it up)?

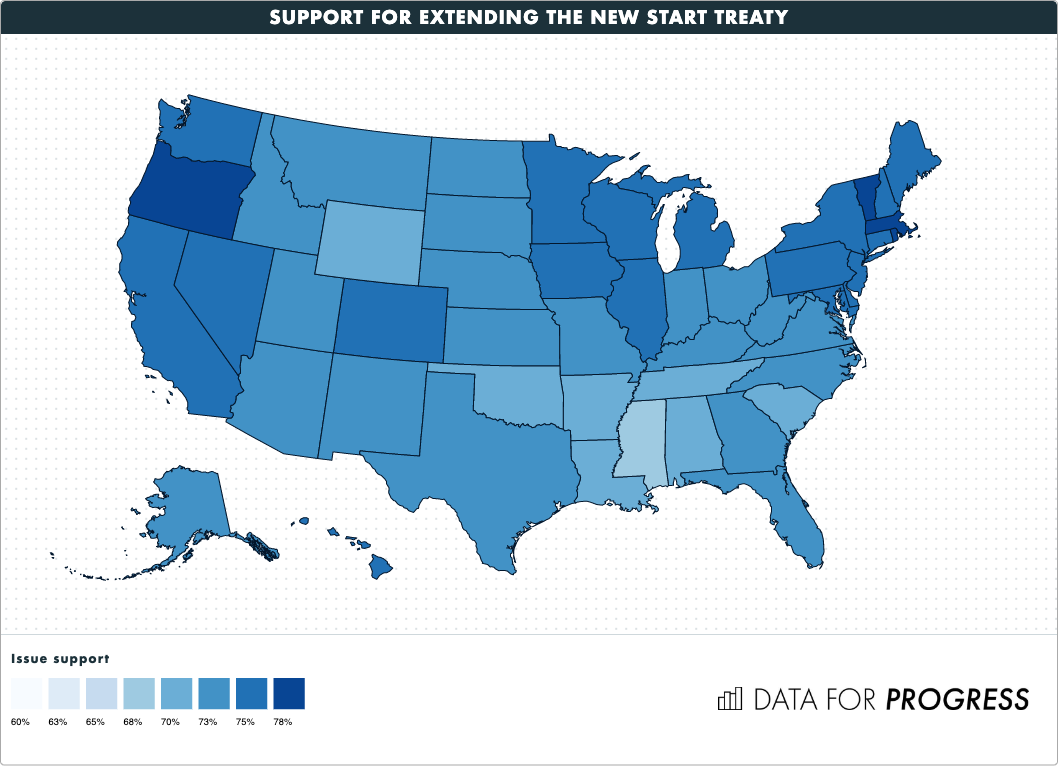

4. New START has overwhelming bipartisan support––even among Trump voters. Not only is extension a foreign policy priority for Democrats, but polling data indicates that approximately 70% of Trump voters across the country are in favor of extending New START.

Additionally, senior military leaders like the Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the commander of Air Force Global Strike Command have expressed support for the treaty. Even one of Trump’s own political appointees, Deputy Secretary of Defense for Policy David Trachtenberg, has testified that that “the transparency and verification requirements of the New START Treaty are a benefit” to the security of the United States.

5. We won’t get another chance. If New START expires next year, arms control between Russia and the United States as we know it is effectively over. Given the underlying East-West tensions and upcoming dramatic governance shifts in both the United States and Russia, there appears to be little interest or bandwidth available on either side in negotiating a new and improved treaty.

Moreover, although future arms control must attempt to incorporate other nuclear-armed states, efforts to do so should not jeopardize New START.

At risk of stating the obvious, negotiating a new treaty is exponentially more difficult than extending an existing one.

6. It’s easy. Extension of New START doesn’t require Congressional legislation or Senate ratification. All it takes is a presidential stroke of a pen. And at the end of 2019, Putin offered to immediately extend the treaty “without any preconditions.” President Trump should immediately take him up on his offer; as of today, he has exactly one year left to do so. But don’t wait till the last minute! Get it done!

Additional information:

- New START Treaty Data Shows Treaty Keeping Lid On Strategic Nukes

- The New START Treaty Keeps Nuclear Arsenals In Check And President Trump Must Act To Preserve It

- Overview: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

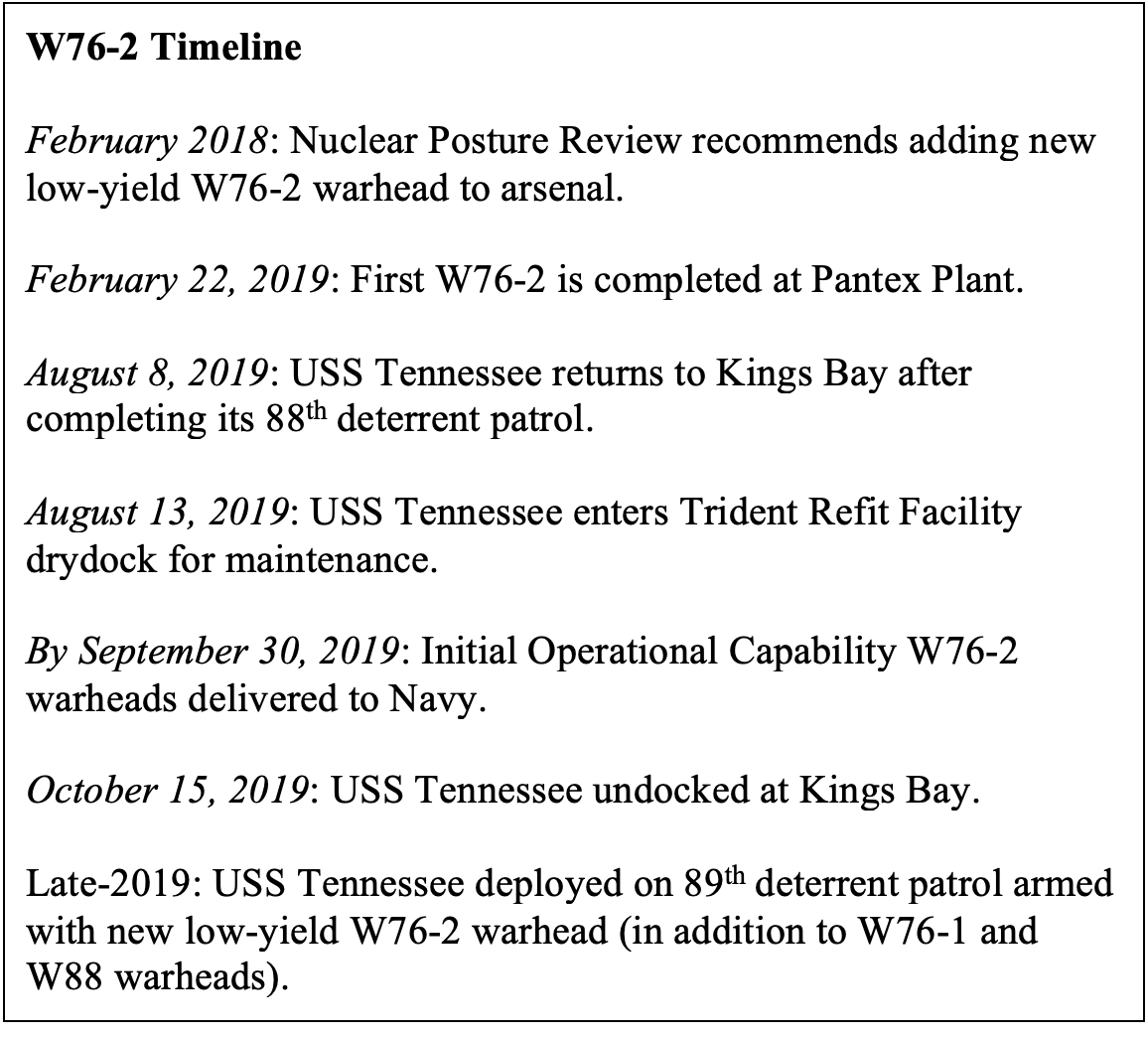

US Deploys New Low-Yield Nuclear Submarine Warhead

The USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) at sea. The Tennessee is believed to have deployed on an operational patrol in late 2019, the first SSBN to deploy with new low-yield W76-2 warhead. (Picture: U.S. Navy)

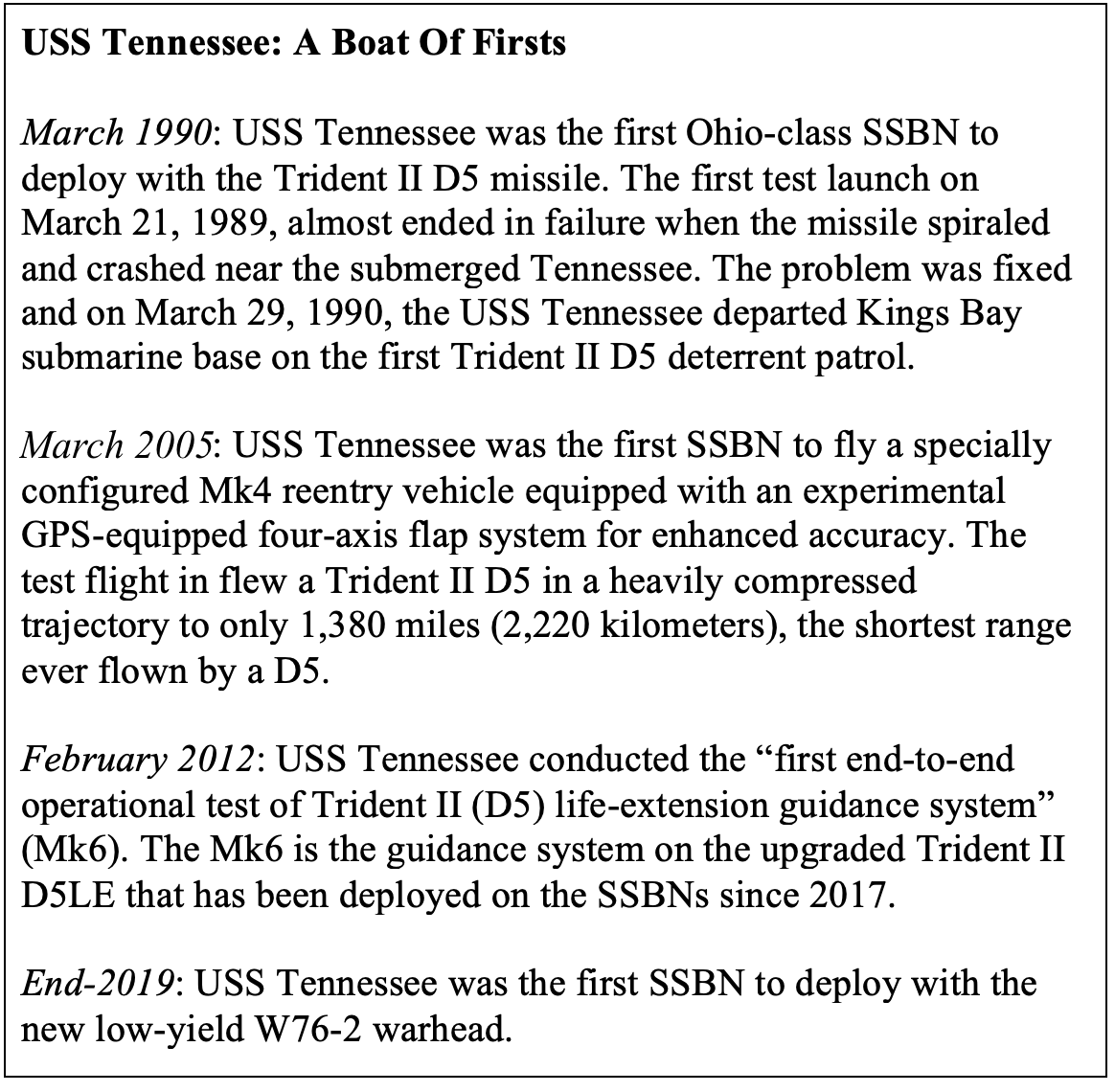

The US Navy has now deployed the new W76-2 low-yield Trident submarine warhead. The first ballistic missile submarine scheduled to deploy with the new warhead was the USS Tennessee (SSBN-734), which deployed from Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia during the final weeks of 2019 for a deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean.

The W76-2 warhead was first announced in the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) unveiled in February 2018. There, it was described as a capability to “help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable ‘gap’ in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities,” a reference to Russia. The justification voiced by the administration was that the United States did not have a “prompt” and useable nuclear capability that could counter – and thus deter – Russian use of its own tactical nuclear capabilities.

We estimate that one or two of the 20 missiles on the USS Tennessee and subsequent subs will be armed with the W76-2, either singly or carrying multiple warheads. Each W76-2 is estimated to have an explosive yield of about five kilotons. The remaining 18 missiles on each submarine like the Tennessee carry either the 90-kiloton W76-1 or the 455-kiloton W88. Each missile can carry up to eight warheads under current loading configurations.

The first W76-2 (known as First Production Unit, or FPU) was completed at Pantex in February 2019. At the time, NNSA said it was “on track to complete the W76-2 Initial Operational Capability warhead quantity and deliver the units to the U.S Navy by the end of Fiscal Year 2019” (30 September 2019). We estimate approximately 50 W76-2 warheads were produced, a low-cost add-on to improved W76 Mod 1 strategic Trident warheads which had just finished their own production run.

The W76-2 Mission

The NPR explicitly justified the W76-2 as a response to Russia allegedly lowering the threshold for first-use of its own tactical nuclear weapons in a limited regional conflict. Nuclear advocates argue that the Kremlin has developed an “escalate-to-deescalate” or “escalate-to-win” nuclear strategy, where it plans to use nuclear weapons if Russia failed in any conventional aggression against NATO. The existence of an actual “escalate-to-deescalate” doctrine is hotly debated, though there is evidence that Russia has war gamed early nuclear use in a European conflict.

Based upon the supposed “escalate-to-deescalate” doctrine, the February 2018 NPR claims that the W76-2 is needed to “help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable ‘gap’ in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities.” The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has further explained that the “W76-2 will allow for tailored deterrence in the face of evolving threats” and gives the US “an assured ability to respond in kind to a low-yield nuclear attack.”

Consultants who were involved in producing the NPR have suggested that “[Russian President] Putin may well believe that the United States would not respond with strategic warheads that could cause significant collateral damage” and “that Moscow could conceivably engage in limited nuclear first-use without undue risk…”

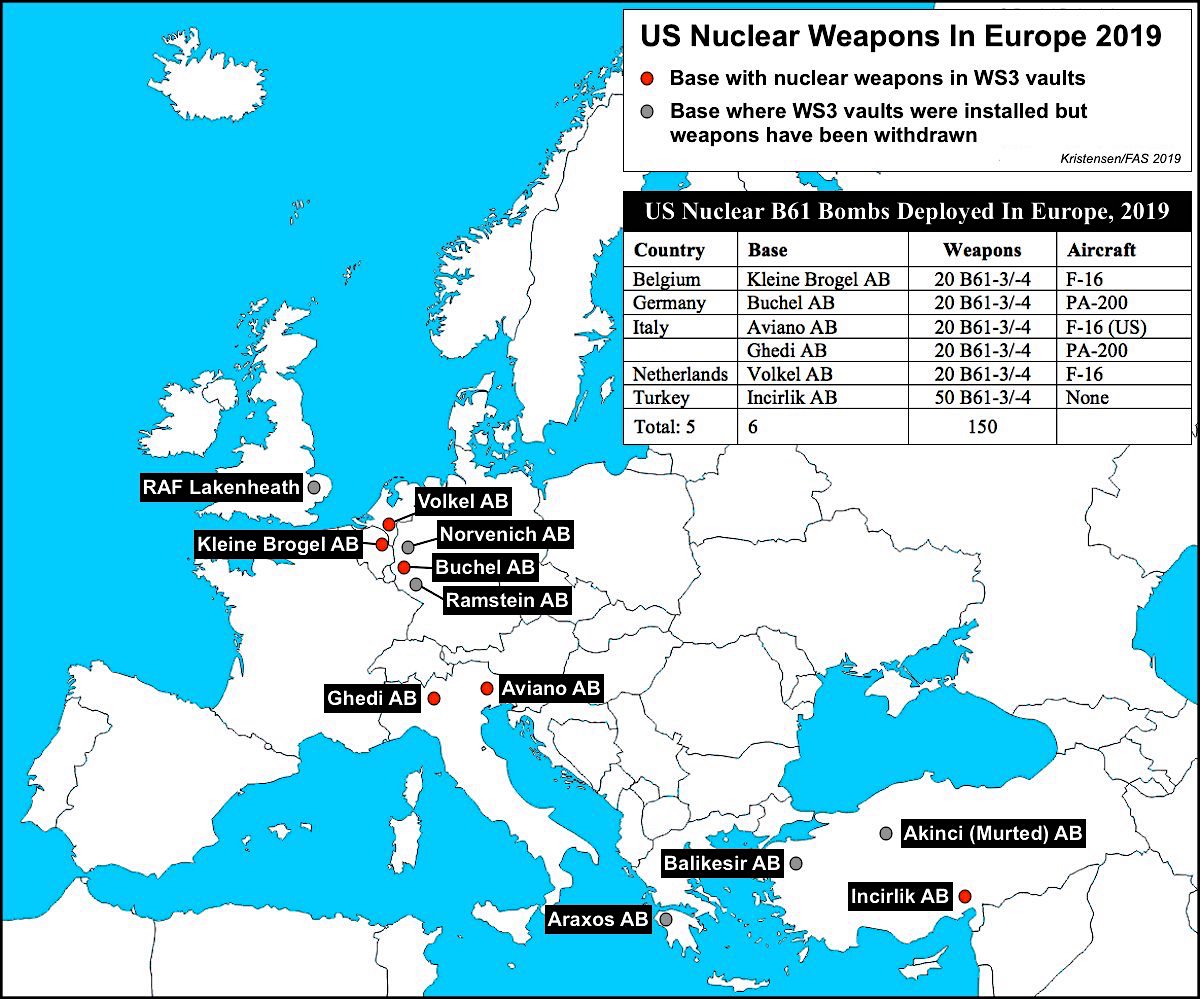

There is no firm evidence that a Russian nuclear decision regarding the risk involved in nuclear escalation is dependent on the yield of a US nuclear weapon. Moreover, the United States already has a large number of weapons in its nuclear arsenal that have low-yield options – about 1,000 by our estimate. This includes nuclear cruise missiles for B-52 bombers and B61 gravity bombs for B-2 bombers and tactical fighter jets.

Yes, but – so the W76-2 advocates argue – these low-yield warheads are delivered by aircraft that may not be able to penetrate Russia’s new advanced air-defenses. But the W76-2 on a Trident ballistic missile can. Nuclear advocates also argue the United States would be constrained from employing fighter aircraft-based B61 nuclear bombs or “self-deterred” from employing more powerful strategic nuclear weapons. In addition to penetration of Russian air defenses, there is also the question of NATO alliance consultation and approval of an American nuclear strike. Only a low-yield and quick reaction ballistic-missile can restore deterrence, they say. Or so the argument goes.

All of this sounds like good old-fashioned Cold War warfighting. In the past, every tactical nuclear weapon has been justified with this line of argument, that smaller yields and “prompt” use – once achieved through forward European basing of thousands of warheads – was needed to deter. Now the low-yield W76-2 warhead gives the United States a weapon its advocates say is more useable, and thus more effective as a deterrent, really no change from previous articulations of nuclear strategy.

The authors of the NPR also saw the dilemma of suggesting a more usable weapon. They thus explained that the W76-2 was “not intended to enable, nor does it enable, ‘nuclear war-fighting.’ Nor will it lower the nuclear threshold.” In other words, while Russian low-yield nuclear weapons lower the threshold making nuclear use more likely, U.S. low-yield weapons instead “raise the nuclear threshold” and make nuclear use less likely. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood even told reporters that the W76-2 would be “very stabilizing” and in no way supports U.S. early use of nuclear weapons, even though the Nuclear Posture Review explicitly stated the warhead was needed for “prompt response” strike options against Russian early use of nuclear weapons.

“Prompt response” means that strategic Trident submarines in a W76-2 scenario would be used as tactical nuclear weapons, potentially in a first use scenario or immediately after Russia escalated, thus forming the United States’ own “escalate-to-deescalate” capability. The United States has refused to rule out first use of nuclear weapons.

The USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) in drydock at Kings Bay submarine base in September 2019 shortly before it returned to active duty and loaded with Trident D5 missiles carrying the new low-yield W76-2 warhead. (Photo: U.S. Navy)

Since the United States ceased allocating some of its missile submarines to NATO command in the late-1980s, U.S. planners have been reluctant to allocate strategic ballistic missiles to limited theater tasks. Instead, NATO’s possession of dual-capable aircraft and increasingly U.S. long-range bombers on Bomber Assurance and Deterrence Operations (BAAD) – now Bomber Task Force operations – have been seen as the most appropriate way to slow down regional escalation scenarios. The prompt W76-2 mission changes this strategy.

In the case of the W76-2, carried onboard a submarine otherwise part of the strategic nuclear force, amidst a war Russia would have to determine that a tactical launch of one or a few low-yield Tridents was not, in fact, the opening phase of a much larger escalation to strategic nuclear war. Thus, it seems inconceivable that any President would approve employment of the W76-2 against Russia; deployment on the Trident submarine might actually self-deter.

Though almost all of the discussion about the new W76-2 has focused on Russia scenarios, it is much more likely that the new low-yield weapon is intended to facilitate first-use of nuclear weapons against North Korea or Iran. The National Security Strategy and the NPR both describe a role for nuclear weapons against “non-nuclear strategic attacks, and large-scale conventional aggression.” And the NPR explicitly says the W76-2 is intended to “expand the range of credible U.S. options for responding to nuclear or non-nuclear strategic attack.” Indeed, nuclear planning against Iran is reportedly accelerating, B-2 bomber attacks are currently the force allocated but the new W76-2 is likely to be incorporated into U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) war planning.

Cheap, Quick, Simple, But Poorly Understood

In justifying the W76-2 since the February 2018 NPR, DOD has emphasized that production and deployment could be done fast, was simple to do, and wouldn’t cost very much. But the warhead emerged well before the Trump administration. The Project Atom report published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in 2015 included recommendations for a broad range of low-yield weapons, including on long-range ballistic missiles. And shortly after the election of President Trump, the Defense Science Board’s defense priority recommendations for the new administration included “lower yield, primary-only options.” (This refers to the fact that the W76-2 is essentially little different than the strategic W76-1, “turning off” the thermonuclear secondary and thus facilitating rapid production.)

Initially, the military interest in a new weapon seemed limited. When then STRATCOM commander General John E. Hyten (now Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) was asked during Congressional hearings in March 2017 about the military need for lower-yield nuclear weapons, he didn’t answer with a yes or no but explained the U.S. arsenal already had a wide range of yields:

Rep. Garamendi: The Defense Science Board, in their seven defense priorities for the new administration, recommended expanding our nuclear options, including deploying low yield weapons on strategic delivery systems. Is there a military requirement for these new weapons?