Russian Nuclear Missile Submarine Patrols Decrease Again

By Hans M. Kristensen

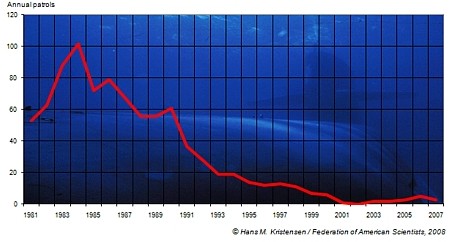

The number of deterrence patrols conducted by Russia’s 11 nuclear-powered ballistic missiles submarines (SSBNs) decreased to only three in 2007 from five in 2006, according to our latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

In comparison, U.S. SSBNs conducted 54 patrols in 2007, more than three times as many as all the other nuclear weapon states combined.

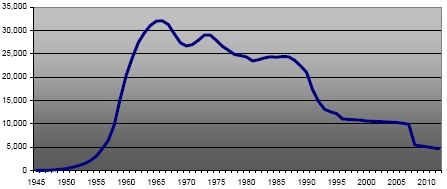

The low Russian patrol number continues the sharp decline from the Cold War; no patrols at all were conducted in 2002 (see Figure 1). The new practice indicates that Russia no longer maintains a continuous SSBN patrol posture like that of the United States, Britain, and France, but instead has shifted to a new posture where it occasionally deploys an SSBN for training purposes.

An Occasional Sea-Based Deterrent

The shift to an occasional sea-based deterrent became apparent in 2007, when then Defense Minister Sergei Ivanov declared on September 11 that five SSBNs were on patrol at that time. Four months later, I received information from U.S. Naval Intelligence showing that those five patrols were all Russian SSBNs did that year. Combined, the two sources indicated a cluster of patrols at approximately the same time rather than distributed throughout the year.

|

Figure 1: |

|

| Russian SSBNs conducted only three deterrent patrols in 2007, a decline from five in 2006. |

.

The reason for the shift is unclear. Perhaps the Russian navy is still not over the financial and technical constraints that hit it after the collapse of the Soviet Union. SSBNs can launch their missile from pier side if necessary, although such a posture essentially converts each SSBN into a very soft and vulnerable target. Russia might simply have decided that it’s no longer necessary to maintain a continuous nuclear retaliatory force at sea, and that a few training patrols are all that’s needed to be able to deploy the SSBNs in a hypothetical crisis if necessary.

SSBN Patrol Areas

Little is known in public about where Russian SSBNs conduct their deterrent patrols. However, in 2000, U.S. Naval Intelligence released a series of rough patrol maps for Soviet/Russian SSBNs that showed the locations of the patrol areas used by Delta IV and Typhoon class SSBNs in the late-1980s and 1990s (see Figure 2). The few SSBNs that occasionally sail on patrol today probably use roughly the same areas.

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Russian SSBN patrol areas today are probably similar to those used in the 1990s. |

.

In Perspective

The decline in SSBN patrols is in stark contrast to Russian bomber and surface fleet operations in 2006-2007, which are said to have increased in scope and reach. For now, at least, SSBN patrols are not used to “signal” Russian status.

Approximately 20 percent of Russia’s strategic warheads are sea-based. But with the upcoming replacement of old Delta III SSBNs and their three-warhead missiles with the new Borey SSBNs (the first of which is scheduled to enter service later this year) with six-warhead missiles, the SSBNs’ share of the posture might increase to approximately 30 percent by 2015.

Overall, the Nuclear Notebook estimates that Russia currently has approximately 5,200 nuclear warheads in its operational stockpile, including some 3,110 strategic and 2,090 non-strategic warheads. Another 8,800 warheads are thought to be in reserve or awaiting dismantlement.

Additional information: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007, Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Old Anti-nuclear Movie from FAS

The Federation of American Scientists was formed just a couple of months after the dawning of the nuclear age by scientists as who had worked on the Manhattan Project to develop the world’s first nuclear weapons. In the fall of 1945, there was tremendous interest in the new atomic bomb: what it was, how it worked, and its effects–and not just direct effects but the effect this invention would have on the military balance and politics of the world. FAS organized a group of its members, which it called the National Committee on Atomic Information, to talk to the public, the press, and political leaders, and to produce media materials for distribution. (Sixty two years later and we still seem to be at it…)

Jeff Aron here at FAS recently came across this amazing little film on YouTube called One World or None. It was produced by FAS and the National Committee. I have to admit, no one currently at FAS knew about it, it predates anyone’s memory here, and we are ourselves doing some research on its origins and asking our long-term members what they know. (If any of our blog readers can provide any information, please let us know.) Presumably, it was released in conjunction with the release of the first publication of the Federation, also called One World or None, a collection of essays by great scientists of the day, including Albert Einstein, that was first published in 1946. One World has recently been reprinted by the New Press in New York and is available through bookstores, Amazon, and the FAS website.

The film is clearly a bit dramatic, but the dangers of nuclear weapons are dramatic. By today’s standards, the graphics are Stone Age but the message is as important today as it ever was and doesn’t depend on fancy graphics. I can’t say you should enjoy this little film–not much to enjoy when discussing nuclear dangers–but I hope you take it to heart. The Federation is still working to reduce the global threat of nuclear weapons.

Nuclear Safety and the Saga About the Missing Bent Spear

By Hans M. Kristensen

The recent Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on Air Force nuclear weapons safety was a welcome but long-overdue event. Internal reports about deteriorating nuclear weapon safety and surety in the Air Force have been accumulating since the early 1990s, but six nuclear weapons had to “disappear” for a day from Minot Air Force Base last August to get the Pentagon and Congress to finally pay attention. Had it not been for reporter Michael Hoffman at Military Times, the incident likely would have been filed away in secret cabinets as well.

Two internal investigations have identified numerous deficiencies in the handling and management of nuclear weapons within the military and have recommended substantial changes. Some of the obvious recommendations – such as not storing nuclear and conventional weapons in the same bunker and that personnel must follow the rules – have now been implemented. Others will require more effort.

Yet the investigations have revealed an inherent problem in post-Cold War nuclear planning: self-management and lack of independent oversight. Indeed, the investigations themselves appear to have been hampered by the same shortcomings. The result is an inherent conflict between scrutinizing and promoting the nuclear mission and a reluctance to change things too much.

As a consequence, the reviews recommend revitalizing the nuclear mission and returning the bombers to a heightened nuclear alert posture to improve safety, while missing the most obvious and effective fix: removing nuclear weapons from bomber bases and ending the operational nuclear bomber mission.

U.S. Plans Test of Anti-Satellite Interceptor Against Failed Intelligence Satellite

The United States is planning to intercept a dying reconnaissance satellite with a missile launched from a Navy ship. The administration justifies the intercept on the basis of public safety. That is a long stretch, indeed, and thus far in the news coverage that I have seen there is virtually no mention of the political consequences of the United States’ conducting its first anti-satellite test in over two decades.

The United States, along with China, Russia, and other space-faring nations, should be working to ban anti-satellite weapons. Such a ban would work strongly in the best interests of the United States because we depend more, by far, than any other nation on access to space for our economy and security. Any measure that reduces the threats to satellites will enhance American security. The proposed test is a potential public relations bonanza, showing the public how a defensive missile can protect us from a—largely imaginary—danger from above. What follows is a simple analysis of what some of these dangers might be and a description of what might happen. These are questions that should have been asked of the administration.

White House Announces (Secret) Nuclear Weapons Cuts

|

|

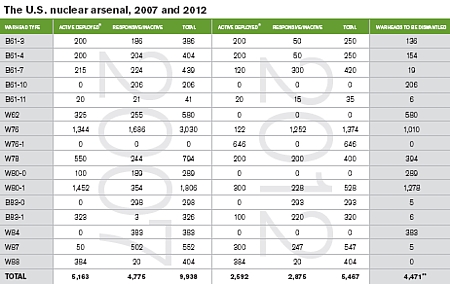

The W62 is the only nuclear warhead that has been publicly identified for elimination under the Bush administration’s secret nuclear stockpile reduction plan. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The While House announced earlier today that the President had “approved a significant reduction in the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile to take effect by the end of 2007.” The decision reaffirmed an earlier decision from June 2004 to cut the stockpile “nearly 50 percent,” but moved the timeline up five years from 2012 to 2007.

Not included in the White House statement, but added by other government officials, is an additional decision to cut the remaining stockpile by another 15% percent, although not until 2012.

The announcement of these important initiatives unfortunately was hampered by Cold War secrecy which meant that government officials were not allowed to reveal how many nuclear weapons will be cut or what the size of the stockpile is. As a result, news media accounts were full of errors, and one can only imagine the misperceptions this misplaced secrecy creates in other nuclear weapon states.

Estimates of the Secret Cuts

Before the latest announcements, I and my colleague Robert Norris estimated that the stockpile consisted of approximately 9,900 warheads of which roughly 4,600 were operational. With the new announcements, we predict the following development:

The White House announcement reaffirms the 2004 decision to reduce the size of the Defense Department’s nuclear weapons stockpile “by nearly 50 percent from the 2001 level.” This objective was reaffirmed by the National Nuclear Security Administration in a press release earlier today. The DOD stockpile included roughly 10,500 warheads in 2001, which means that the 2004 stockpile plan probably envisioned a stockpile of some 5,400 warheads by 2012. It is this cut that the White House reaffirmed today, but implemented by the end of 2007 instead of 2012.

The additional 15 percent reduction announced today and confirmed by the White House would cut approximately 800 warheads more from the 5,400, resulting in an estimated stockpile of roughly 4,600 warheads by 2012.

At that time the SORT agreement signed with Russian in 2002 is scheduled to enter into effect, setting an upper limit of no more than 2,200 operationally deployed strategic warheads. The remaining 2,400 warheads will likely include 2,000 reserve warheads to “hedge” against unforseen political developments and 400 non-strategic bombs.

|

|

|

|

The Bush administration’s planned reduction of the nuclear stockpile is significant but modest compared to the cuts in the 1990s, and will leave a stockpile that is four times larger than the combined arsenals of all other nuclear weapon states (excluding Russia). |

What Doesn’t Change

The White House’s announcement to implement the 2004 stockpile plan in 2007 does not mean that the “cut” warheads will have been dismantled by then – far from it. In fact, the decision to reduce the stockpile does not in itself result in the destruction of a single warhead. “Reducing” the stockpile by nearly half is a form of nuclear book keeping that means that ownership of the “cut” warheads will shift from DOD to DOE.

But DOE doesn’t have storage capacity for all of these weapons at its facility at Pantex. That factory is busy rebuilding the warheads slated to remain in the “enduring stockpile” beyond 2012. As a result, dismantlement of the backlog of warheads from the current reductions is not scheduled to be completed until 2023, more than a decade-and-a-half after today’s White House announcement to speed things up. Indeed, the current administration has demonstrated the lowest warhead dismantlement rate of any U.S. government since the Eisenhower administration.

So for now, most of the “cut” warheads will likely remain at the bases where they are and only gradually be moved to the central warhead storage locations such as Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. The only known timeline for this move is 2012, by which time no more than 2,200 strategic warheads can remain at bases for operational delivery platforms according to the SORT agreement.

Observations

The While House statement highlights that “the U.S. nuclear stockpile will be less than one-quarter its size at the end of the Cold War” [1991, ed.]. But the stockpile the administration plans for 2012 is large by post-Cold War standards:

* Four times the combined number of nuclear weapons of all the world’s nuclear weapons states, excluding Russia.

* Almost half of the stockpile – a maximum of 2,200 warheads – will be operational, and a third of those (more than 850) will be on alert.

* More than 10 times bigger than in 1950, when the United States decided to contain the Soviet Union.

Although the White House says the planned reductions seek to “reduce U.S. reliance on nuclear weapons,” the statement not only reaffirms that “a credible deterrent remains an essential part of U.S. national security,” but also declares that “nuclear forces remain key to meeting emerging security challenges.”

In the weeks ahead, we will fine-tune this estimate further.

More background: Estimates of the U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Today and Tomorrow | Estimates of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, 2007 and 2012

US Arms Sales to Pakistan: New CRS Report

A new Congressional Research Service report on “U.S. Arms Sales to Pakistan” recently obtained by the FAS provides a succinct overview of recent U.S. arms sales to General Pervez Musharraf’s regime, the tumultous fifty-year history of US security assistance to Pakistan, and presidential authority to stop such sales. The release of the report coincides with a worsening political crisis in Pakistan and growing Congressional and public discontent over the United States’ multi-billion dollar military aid program for General Musharraf’s beseiged and increasingly authoritarian regime.

A new Congressional Research Service report on “U.S. Arms Sales to Pakistan” recently obtained by the FAS provides a succinct overview of recent U.S. arms sales to General Pervez Musharraf’s regime, the tumultous fifty-year history of US security assistance to Pakistan, and presidential authority to stop such sales. The release of the report coincides with a worsening political crisis in Pakistan and growing Congressional and public discontent over the United States’ multi-billion dollar military aid program for General Musharraf’s beseiged and increasingly authoritarian regime.

(more…)

White House Guidance Led to New Nuclear Strike Plans Against Proliferators, Document Shows

By Hans M. Kristensen

The 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) and White House guidance issued in response to the terrorist attacks against the United States in September 2001 led to the creation of new nuclear strike options against regional states seeking to acquire weapons of mass destruction, according to a military planning document obtained by the Federation of American Scientists.

Rumors about such options have existed for years, but the document is the first authoritative evidence that fear of weapons of mass destruction attacks from outside Russia and China caused the Bush administration to broaden U.S. nuclear targeting policy by ordering the military to prepare a series of new options for nuclear strikes against regional proliferators.

Responding to nuclear weapons planning guidance issued by the White House shortly after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, U.S. Strategic Command created a series of scenario driven nuclear strike options against regional states. Illustrations in the document identify the states as North Korea and Libya as well as SCUD-equipped countries that appear to include Iran, Iraq (at the time), and Syria – the very countries mentioned in the NPR. The new strike options were incorporated into the strategic nuclear war plan that entered into effect on March 1, 2003.

The creation of the new strike options contradict statements by government officials who have insisted that the NPR did not change U.S. nuclear policy but decreased the role of nuclear weapons.

Non-Denial Denials and a Few Hints

When portions of the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) were leaked in the Los Angeles Times in March 2002, government officials responded by playing down the importance of the document and its effect on nuclear planning. And officials have since continue to credit the NPR with reducing the reliance on nuclear weapons.

The NPR is “not a plan, it’s not an operational plan,” then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard B. Myers insisted on CNN the day after the NPR was leaked. “It’s a policy document. And it simply states our deterrence posture, of which nuclear weapons are a part….And it’s been the policy of this country for a long time, as long as I’ve been a senior officer, that the president would always reserve the right up to and including the use of nuclear weapons if that was appropriate. So that continues to be the policy.”

A formal statement published by the Department of Defense added that the NPR “does not provide operational guidance on nuclear targeting or planning,” but that the military simply “continues to plan for a broad range of contingencies and unforeseen threats to the United States and its allies.”

Most recently, on October 9, 2007, Christina Rocca, the U.S. permanent representative to the Conference on Disarmament, told the First Committee of the U.N. General Assembly that the United States has been “reducing the…degree of reliance on [nuclear] weapons in national security strategies….It was precisely the new thinking embodied in the NPR that allowed for the historic reductions we are continuing today.”

Yet a few officials hinted in 2002 that the same guidance expanded nuclear planning. “There are nations out there developing weapons of mass destruction,” then Secretary of State Colin Powell said on CBS’ Face the Nation. “Prudent planners have to give some consideration as to the range of options the president should have available to him to deal with these kinds of threat,” he said.

The declassified U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) document shows that one of the first results of “the new thinking” of the NPR was the creation of a series of new nuclear strike options against regional states.

A Series of Regional Options

The 26-page declassified document, an excerpt from a 123-page STRATCOM briefing on the production of the 2003 strategic nuclear war plan known as OPLAN 8044 Revision 03, includes two slides that describe the planning against “regional states.” The first of these slides lists a “series of [deleted] options” directed against regional countries with weapons of mass destruction programs. The planning is “scenario driven,” according to the document. The majority of the document deals with targeting of Russia and China, but virtually all of those sections were withheld by the declassification officer.

The names of the “regional states” were also withheld, but three images used to illustrate the planning were released, and they leave little doubt who the regional states are: One of the images is the North Korean Taepo Dong 1 missile; another image shows the Libyan underground facility at Tarhuna; and the third image shows a SCUD B short-range ballistic missile. The SCUD B image is not country-specific, but the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center report Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat from 2003 listed 12 countries with SCUD B missiles: Belarus, Bulgaria, Egypt, Iran, Kazakhstan, Libya, North Korea, Syria, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Vietnam and Yemen. Five of these were listed in the NPR as examples of countries that were “immediate, potential, or unexpected contingencies…setting requirements for nuclear strike capabilities”: Iran, Iraq, Libya, North Korea and Syria.

|

|

Images included in the declassified STRATCOM document identify several regional states as targets for new nuclear strike plans. |

The inclusion of regional nuclear counterproliferaiton strike options into the national (strategic) war plan is a new development because such scenarios have normally been thought to reside at a lower level than the national strategic plan, which has traditionally been focused on targeting of Russia and China. During the 1990s, STRATCOM developed adaptive planning capabilities that enabled quick production of strikes against “rogue” states if necessary, but “there were no immediate plans on the shelf for target packages to give to bombers or missile crews,” a former senior Pentagon official told Washington Post in 2002. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 changed that by producing executable strike options to the nuclear forces.

The “target base” for the regional states is outlined in the STRATCOM document, but everything except the title has been withheld. But the target base probably included weapons of mass destruction, deep, hardened bunkers containing chemical or biological weapons, or the command and control infrastructure required for the states to execute a WMD attack against the United States or its friends and allies. The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) that entered into effect one year after OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 stated in part: “U.S. nuclear forces must be capable of, and be seen to be capable of, destroying those critical war-making and war-supporting assets and capabilities that a potential enemy leadership values most and that it would rely on to achieve its own objectives in a post-war world.”

The creation of a “target base” indicates that the planning went further than simple retaliatory punishment with one or a few weapons, but envisioned actual nuclear warfighting intended to annihilate a wide range of facilities in order to deprive the states the ability to launch and fight with WMD. The new plan formally broadened strategic nuclear targeting from two adversaries (Russia and China) to a total of seven.

Iraq presumably disappeared from the war plan again after U.S. forces invaded the country in March 2003 – only three weeks after OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 went into effect – and discovered that Iraq did not have weapons of mass destruction. Libya presumably disappeared after December 2003, when President Muammar Gaddafi declared that he was giving up efforts to develop weapons of mass destruction.

The nuclear strike plans against Iran, North Korea and Syria, however, presumably were carried forward into the next OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 from October 2004, a plan that was still in effect as recently as July 2007.

|

Nuclear Guidance |

|

|

|

|

| “The 2001 Nuclear Posture Review (top) and White House guidance led to an expansion of U.S. nuclear targeting plans. |

New Guidance for the Regions

The STRATCOM document indicates that National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD)-14 signed by President Bush on June 28, 2002, was the key While House guidance that resulted in the incorporation into the strategic nuclear war plan of strike options against regional proliferators.

Very little has been disclosed about NSPD-14, except that it laid out Presidential nuclear weapons planning guidance and provided broad overarching directions to the agencies and commands for nuclear weapon planning. As such, NSPD-14 might have been replacing Presidential Decision Directive (PDD)-60 signed by President Clinton in November 1997 as the primary White House guidance for nuclear weapons planning. PDD-60 reportedly also required planning against proliferators, but the new strike options incorporated into Revision 03 were “notable changes” compared with the previous plan, according to the STRATCOM document.

Flowing from NSPD-14 were several other important guidance documents that deepened the commitment to targeting regional proliferators. The first was the JSCP Transitional Guidance in June 2002, which directed changes to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP). JSCP includes a nuclear annex or supplement, known as JSCP-N, that give detailed nuclear planning guidance to the unified and regional commanders. The new JSCP-N was published on October 1, 2002. Another document was the NUWEP (Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy) Transitional Guidance signed on August 29, 2002, which led to the publication of NUWEP-04 in April 2004.

Three months after NSPD-14, on September 14, 2002, President Bush also signed NSPD-17 (National Strategy to Combat Weapons of Mass Destruction), a directive that articulated a comprehensive strategy to counter nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction. NSPD-17 reaffirmed that, if necessary, the United States will use nuclear weapons against anyone using weapons of mass destruction against the United States, its forces abroad, and friends and allies, according to Washington Times. But a top-secret appendix to NSPD 17 specifically named Iran, Syria, North Korea and Libya as being among the countries that are the central focus of the new strategy, and that options included nuclear weapons. Those options were in place with OPLAN 8044 Revision 03. The motivation for the new strategy, one participant in the interagency process that drafted it told Washington Post, was the conclusion that “traditional nonproliferation has failed, and now we’re going into active interdiction.” NSPD-17 is sometimes also called the preemption doctrine.

The regional strike plans also found their way into the draft Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations (Joint Publication 3-12), which was under preparation within the military at the time Revision 03 was created. Yet the doctrine showed that planning went beyond retaliation and included preemptive strikes. The second draft from March 2005 listed five scenarios where use of nuclear weapons might be requested:

• To counter an adversary intending to use weapons of mass destruction against U.S., multinational, or allies forces or civilian populations;

• To counter an imminent attack from an adversary’s biological weapons that only effects from nuclear weapons can safely destroy;

• To attack on adversary installations including weapons of mass destruction, deep, hardened bunkers containing chemical or biological weapons, or the command and control infrastructure required for the adversary to execute a WMD attack against the United States or its friends and allies; [this was probably the “target base” in OPLAN 8044 Revision 03]

• To counter potentially overwhelming adversary conventional forces;

• To demonstrate U.S. intent and capability to use nuclear weapons to deter adversary WMD use.

After I disclosed this development in an article in Arms Control Today in September 2005 and the Washington Post followed up with a front-page story, sixteen members of Congress – including the current chair of the House Armed Services Committee – reacted by writing to the president to object to what they considered to be a “drastic shift in U.S. nuclear policy.”

Embarrassed by the exposure, the Pentagon canceled not only the draft doctrine (and four other related doctrine documents) but also the existing Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations document that had been publicly available on the Joint Chiefs of Staff web site for a decade. A Joint Staff official explained that the documents would not be published, revised or classified, explaining that that they had been found not to be real doctrine documents but “pseudo doctrine” documents discussing nuclear policy issues. The public “visibility led a lot of people to question why we have them,” he said.

|

|

|

|

During the tenure of Admiral Ellis (right), STRATCOM prepared, and CJCS Richard Myers (left) approved, an expansion of the SIOP to “a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios.” |

From SIOP to OPLAN 8044: A “Family of Plans”

There is no indication that cancelation of the Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations documents changed nuclear policy. The declassified STRATCOM document describes OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 as “a transitional step toward the new TRIAD and future war plans.” That transition began long before the “New Triad” phrase was coined by the 2001 NPR, and has gradually transformed the top-heavy self-standing Single Integrated Operational Plan (SIOP) to a broader set of strike options applicable in a wider range of scenarios against more adversaries. When preparation of Revision 03 began in March 2002, the combat employment portion of the strategic nuclear war plan was still known as the SIOP, but the name had to be changed to reflect the emerging multitude of strike options.

As the Joint Staff started to review the new war plan, STRATCOM commander Admiral James Ellis wrote to General Myers that the name SIOP did not properly describe the new plan. “STRATCOM is changing the nation’s nuclear war plan from a single, large, integrated plan to a family of plans applicable in a wider range of scenarios,” Ellis explained with a reference to Revision 03. The first STRATCOM commander, General George Lee Butler, had tried to change the name in 1992, but with no luck. Butler wanted to change the name to National Strategic Response Plans. Eleven years later, Admiral Ellis tried again. The SIOP name, he said, was a Cold War legacy.

This time, the JCS chairman was more receptive. On February 8, 2003, only one month before Revision 03 went into effect, General Myers authorized STRATCOM to formally change the name to reflect the creation the “new family of plans.” Yet Myers was concerned that confusion might arise “between the basic USSTRATCOM OPLAN 8044 and the combat employment portion of that OPLAN, currently known as the SIOP.” The solution, he decided, was to continue to call the basic plan OPLAN 8044, but incorporate the term OPLAN 8044 Revision (FY) to describe that portion of the plan currently known as the SIOP. The Revision number (FY) would correspond to the fiscal year the combat employment plan was put into effect. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 of March 1, 2003, was the first plan to carry the new name.

The new strike options apparently were carried forward into OPLAN 8044 Revision 05, the next strategic war plan that entered into effect on October 1, 2004. This plan was described as a “major revamping” of the U.S. strategic war plan, which, according to General Myers, “provides more flexible options to assure allies, and dissuade, deter, and if necessary, defeat adversaries in a wider range of contingencies.” OPLAN 8044 Revision 05 was still in effect as of July 2007 (for a chronology of U.S. nuclear guidance and war plans under the Bush administration, go here).

Claims About Reducing Reliance On Nuclear Weapons

Officials frequently credit the NPR with having significantly reduced the reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. nuclear policy. The basis for this claim is that non-nuclear capabilities also should play a role in deterring potential adversaries, an goal exemplified by the incorporation of conventional strike options into OPLAN 8044 Revision 05, the war plan than followed OPLAN 8044 Revision 03, and the removal of Russia as an “immediate contingency.”

“The United States has set in motion an entirely new way of looking at the role of nuclear weapons in our defense strategy,” Jackie W. Sanders, U.S. Ambassador and Special Representative of the President for the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, told the 2005 Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference. “I speak, Mr. Chairman, of the U.S. Nuclear Posture Review, or NPR, of 2001. The United States has undertaken reviews of this sort in the past, but the 2001 NPR is unique, and fully consistent with Article VI. The 2001 NPR established a New Triad of strategic capabilities, one that places far less reliance on nuclear weapons to meet U.S. defense policy goals…. Let me emphasize, Mr. Chairman, that the New Triad concept resulting from the NPR, in principle and in practice, will reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy. It reflects a totally new vision of the future, and is fully consistent with our indisputable resolve to implement Article VI.”

But while some conventional weapons are being incorporated into the national war plan and planning against Russia is not done in the same way it was during the Cold War, the NPR (building on the 1997 PDD-60) and White House guidance also resulted in an increased nuclear targeting of China and, as the declassified STRATCOM document illustrates, an geographic expansion of national-level nuclear targeting to regional proliferators. Prudent or not, this is not a development that is highlighted by U.S. diplomats at NPT conferences.

Description of Document

The declassified document is heavily redacted and consists of 26 of a total of 123 slides from the Revision 03 Periodic Update of the U.S. strategic war plan that went into effect on March 1, 2003. The plan was the first strategic war plan to carry the new name Operations Plan (OPLAN) 8044 Revision 03, which replaced the Single Operational Strategic Plan (SIOP) name used since 1960. OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 replaced SIOP-03 from October 1, 2002.

The document describes six parts of the new plan preparation: Revision 03 production status, planning guidance, target base, committed forces, options, and conclusions.

The document is not dated, but appears to be from October 2002, shortly before the Secretary of Defense was briefed. Targeting intelligence and selection had been completed, warheads allocated to the strike plans, and strike (sortie) planning for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs), Sea-Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs), and long-range bombers nearly completed. After a Joint Staff review and production of the final Revision Report 03 in January 2003, final Defense Secretary review and approval by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff were scheduled for late January 2003 before OPLAN 8044 Revision 03 went into effect on March 1, 2003.

Declassification of the document took four years. It was released in response to a FOIA request submitted in October 2003 for documents pursuant to remarks made by then Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard Myers during a Senate Foreign Relations Committee Hearing in July 2002. When asked if there had been a review of the SIOP since the mid-1990s, Myers replied: “Yes, there absolutely has. In fact, the secretary and I spent considerable time revising the SIOP. I think we started that last year and have gotten another major review ongoing.” The declassified document was released on October 10, 2007.

Resources: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Guidance | The Matrix of Deterrence | The Post Cold War SIOP and Nuclear Warfare Planning: A Glossary, Abbreviations, and Acronyms

Acknowledgements: This research has been made possible by support from the Ford Foundation, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund.

Flying Nuclear Bombs

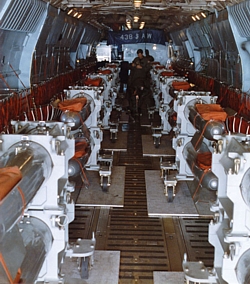

|

|

The Air Force is reported to have loaded and flown five (some say six) nuclear-armed Advanced Cruise Missiles on a B-52H bomber – by mistake. This image shows a B-52H will a full load of 12 Advanced Cruise Missiles under the wings. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Michael Hoffman reports in Military Times that five (some say six) nuclear-armed Advanced Cruise Missiles were mistakenly flown on a B-52H bomber from Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana on August 30.

I disclosed in March that the Air Force had decided to retire the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM), and the Minot incident apparently was part of the dismantlement process of the weapon system.

| Update September 23, 2007: Contributed information to story in the Washington Post.Update September 6, 2007: The Air Force has issued a statement on the B-52 incident. |

Managing Nuclear Weapons Custody

Beyond the safety issue of transporting nuclear weapons in the air, the most important implication of the Minot incident is the apparent break-down of nuclear command and control for the custody of the nuclear weapons. Pilots (or anyone else) are not supposed to just fly off with nuclear bombs, and base commanders are not supposed to tell them to do so unless so ordered by higher command. In the best of circumstances the system worked, and someone “upstairs” actually authorized the transport of nuclear cruise missiles on a B-52H bomber.

To keep track of the thousands of nuclear weapons in the U.S. nuclear stockpile, the Department of Defense and Department of Energy use several Automated Information Systems (AISs) to provide automated assistance in stockpile management, stockpile database support, in processing nuclear weapons reports and controlling weapons movements, and in coordinating materiel management for DOE spare parts:

* Defense Integration and Management of Nuclear Data Services (DIAMONDS). Automated tool that, together with the Nuclear Management Information System (NUMIS), enables users to maintain, report, track and highlight trends affecting the nuclear weapon stockpile activities ensuring continued sustainability and viability of the nuclear stockpile. Installation of DIAMONDS at Navy sites was completed in December 2006.

* Nuclear Management Information System (NUMIS). NUMIS is the official AIS of record for maintaining the National Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Databases, and is used to maintain current data on the U.S. nuclear stockpile in the custody of DOD and DOE.

* Nuclear Weapons Contingency Operations Module (NWCOM). NWCOM is a database system that provides current summarized information on all nuclear weapons. NWCOM has the capability to operate independently from the NUMIS architecture, giving users a nuclear weapons tracking system capable of wartime operations. Once fully segmented and integrated into the Global Command and Control System-Top Secret (GCCS-T), NWCOM will begin its integration into the DOD (DISA/STRATCOM) Nuclear Planning and Execution System (NPES).

* Special Weapons Information Management (SWIM) system. SWIM is a PC-based system that provides worldwide nuclear custodial units the capability to automate weapons status reports and local stockpile management tasks.

|

|

|

|

Twenty-four B61 nuclear bombs lined up in the cargo hull of a C-124 cargo aircraft of the 438th Airlift Wing. Since this Air Force picture was taken, the C-124 has been retired and its mission of nuclear weapons transporter taken over by the C-17. |

A Brief History of Nukes in the Air

The last time the Air Force is known to have flown nuclear weapons on a bomber was during the so-called Chrome Dome missions in the 1960s when the Air Force maintained a dozen bombers loaded with nuclear weapons in the air at any time. The program, formally known as the Airborne Alert Program, lasted between July 1961 and January 1968. The program ended abruptly on January 21, 1968, when a B-52 carrying four B28 thermonuclear bombs crashed on the ice off Thule Air Base in Greenland during an emergency landing. The accident followed another crash in Spain in 1966 and several other nuclear incidents.

Between 1968 and 1991, Air Force bombers continued to be loaded with nuclear weapons and stand alert at the end of runways on bases across the country, but flying them was not allowed due to safety concerns. The ground alert ended in September 1991 when the bombers were taken off nuclear alert as part of the first Bush administration’s Presidential Nuclear Initiative.

Although nuclear weapons are not flown on combat aircraft under normal circumstances, they are routinely flown on selected C-17 and C-130 transport aircraft, which as the Primary Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) are used to airlift Air Force nuclear warheads between operational bases and central service and storage facilities in the United States and in Europe (see overview here).

Trimming the Cruise Missile Inventory

The ACM transport from Minot Air Force Base is part of the Air Force’s transition to a slimmer nuclear cruise missile force. By 2012, the current inventory of 1,800 nuclear cruise missiles will be trimmed to 528. The transition will completely retire 400 ACMs and scrap about 870 Air Launch Cruise Missiles (ALCMs). Under the plan, the 2nd Bomb Wing at Barksdale Air Force Base will no longer have a nuclear cruise missile capability, and all of the remaining 528 ALCMs will be based at Minot Air Force Base.

| Read also the comments section:

“If the B-52 incident tells us that the military’s command and control system cannot ensure with 100% certainty which weapons are nuclear and which ones are not, imagine the implications of the wrong weapon being used in a crisis or war. ‘Sorry Mr. President, we thought it was conventional.'” …and my comment on Google News. |

Background: USAF statement | U.S. Air Force Decides to Retire Advanced Cruise Missile | U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Today and Tomorrow

Article: U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Today and Tomorrow

|

|

The latest FAS-NRDC estimate of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile currently contains an estimated 9,900 nuclear warheads of 15 different versions of nine basic types, according to the latest FAS-NRDC Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. By 2012, approximately 4,470 of the warheads will have been withdrawn, leaving a stockpile of roughly 5,500 warheads.

The administration insists that the size and breakdown of the stockpile must be kept secret in the interest of national security, but a growing number of lawmakers argue that some stockpile information is not necessary to classify.

The Nuclear Notebook is written by FAS’ Hans M. Kristensen and NRDC’s Robert Norris.

Background: Administration Increases Submarine Warhead Production Plan | Estimates of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, 2007 and 2012 | U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2007

Administration Increases Submarine Nuclear Warhead Production Plan

|

|

The slim Mk4A reentry body for the W76-1 warhead. The administration plans to produce 2,000 between 2007 and 2021. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Bush administration has decided to more than double the number of nuclear warheads undergoing an expensive upgrade for potential future deployment on the Navy’s 14 ballistic missile submarines, according to answers provided by the National Nuclear Security Administration in response to questions from the Federation of American Scientists.

The decision preempts a debate in Congress about how the United States should size its future nuclear weapons arsenal.

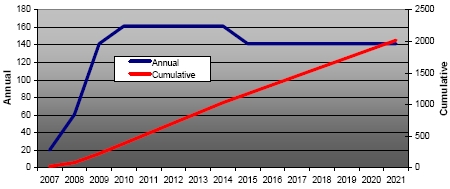

The upgrade concerns the W76, the most numerous warhead in the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile. The Clinton administration decided to upgrade 25 percent, but the Bush administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) in 2001 recommended that significantly more warheads had to be upgraded. An assessment completed by the Department of Defense in 2005 increased the plan to 63 percent of the W76 stockpile, corresponding to an estimated 2,000 warheads.

More than just a refurbished weapon, official sources indicate, the new weapon will have significantly increased military capabilities against hard targets.

Expansion of the W76 Life Extension Program

The W76 Life Extension Program (LEP) was initially approved in March 2000, when the Nuclear Weapons Council approved life-extension of approximately 800 W76s (Block 1). The decision whether to proceed with Block 2 and how many W76s to life-extend in total was deferred. Block 1 completion was initially set for 2012, but in subsequent DOE budget requests the W76 LEP completion date gradually began to slide: 2013 in the FY 2005 request; 2017 in the FY 2006 request; 2020 in the FY 2007 budget request; and most recently 2021 in the FY 2008 request. It was this slide that in May prompted FAS to submit questions to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The NNSA letter explains that DOD requirements before 2001 called for 25 percent of the W76 stockpile to be life-extended, or approximately 800 of the roughly 3,200 W76 warheads estimated to be in the stockpile at the time. But the Bush administration’s 2001 Nuclear Posture Review “resulted in plans to refurbish a significantly greater quantity.” The NPR was implemented by the March 2003 Nuclear Posture Review Implementation Plan, a 26-page document that instructed government agencies which parts of the NPR they must implement and when. Finally, the “most recent classified [W76 LEP]Selected Acquisition Report estimate is for a planned refurbishment of 63 percent of the stockpile,” according to NNSA.

|

|

|

|

The Bush administration’s plan to life-extend 63 percent of the W76 stockpile requires production of approximately 2,000 W76-1 warheads between 2007 and 2021. Authorization to produce the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) from 2014 could affect the second half of the plan. |

The 63 percent requirement (roughly 2,000 warheads) contained in the 2007 W76 LEP Selected Acquisition Report was set, the NNSA letter reveals, by the Strategic Capabilities Assessment, a review completed in 2005 in preparation for the Quadrennial Defense Review by the DOD of the assumptions used for the 2001 NPR. The DOD Assessment concluded that “the NPR’s planning assumptions remain valid, although conditions are trending toward − if anything − a more stressing strategic landscape, for example, with respect to North Korea, Iran and nuclear proliferation.”

The W76-1/Mk4A

Approximately 3,250 W76 warheads were produced between 1978 and 1988. The weapons armed the Poseidon C3 and Trident I C4 and currently the Trident II D5 missiles (together with about 400 W88 warheads). A modified W76 also arms Trident II missiles on British submarines. With the service life limit of the oldest units approaching, the Clinton administration in the late 1990s ordered a W76 Life Extension Program (LEP) to extend the service life for another 30 years. Major milestones for the program are:

|

|

|

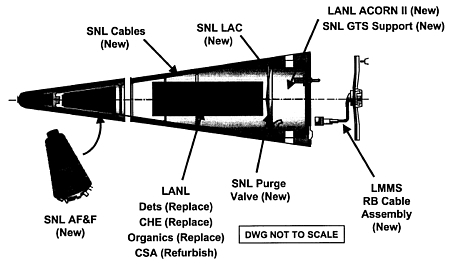

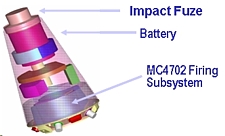

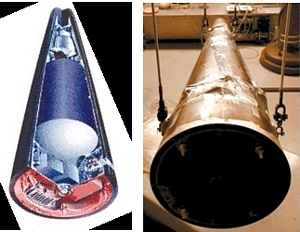

The W76 LEP creates a modified warhead called the W76-1. The cone-shaped Mk4 reentry body designed to protect the warhead against the heat created by the fiery reentry through the earth’s atmosphere will also be modified; the new reentry body is called the Mk4A. The W76 LEP is a major overhaul of the warhead that involves changes to both the reentry body and the warhead package: Replacing “organics” in the primary; replacing detonators; replacing chemical high explosives; refurbishing the secondary; adding a new Arming, Fuzing & Firing (AF&F) system, a new gas reservoir, a new gas transfer support system, a new lightning arrestor connector (LAC) (see Sandia National Laboratories drawing below).

|

|

|

|

The W76 LEP includes significant changes to the both the W76 warhead and the Mk4A reentry body. Guide: AF&F, Arming, Fuzing & Firing; CHE, Chemical High Explosives; CSA, Canned Secondary Assembly; Dets, detonators; GTS, Gas Transfer System; LAC, Lightning Arrestor Connector; LANL, Los Alamos National Laboratory; LMMS, Lockheed Martin Missiles & Space; SNL, Sandia National Laboratories. |

Boosting Hard Target Kill Capability

Government documents and statements by government officials hint that the W76 LEP is quietly creating a weapon with significantly improved military capability over the old version. Whereas the old fuze only permitted targeting of soft targets, the new MC4700 Arming, Fuzing and Firing (AF&F) system gives the W76 hard target kill capability for the first time. The former head of the navy’s Strategic Systems Program, Rear Admiral George P. Nanos, who later became the Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory which designed the W76, explained in an article in The Submarine Review in April 1997 that the “capability for the [existing] Mk4…is not very impressive by today’s standards, largely because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” But “with the accuracy of D5 and Mk4, just by changing the fuse in the Mk4 re-entry body, you get a significant improvement,” Nanos stated. In fact, “the Mk4, with a modified fuze and Trident II accuracy, can meet the original D5 hard target requirement.”

|

|

|

|

The new MC4700 Arming, Fuzing and Firing system developed for the W76-1/Mk4A will enable the warhead to take advantage of the accuracy of the Trident II D5 missile to “meet the original D5 hard target requirement.” |

The added capability is normally not highlighted in official presentations of the W76 LEP. Yet the purpose of developing a new AF&F system on the W76-1/Mk4A, according to the Department of Energy’s 1997 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (excerpt), is to “enable [the] W76 to take advantage of [the] higher accuracy of the D5 missile.”

There are two reasons for increasing the accuracy. First, the previous hard target kill missile – the Peacekeeper ICBM – was withdrawn from operational service in 2005, and the modernized Minuteman III apparently has not been able to achieve the same degree of accuracy. Second, as the number of weapons in the nation’s arsenal is reduced, the ones remaining must be more flexible and capable of holding a wider range of targets than before.

With “advanced fuzing options” the AF&F system will allowing targeteers to set the Height of Burst (HOB) more accurately and significantly improve the ability to hold hard targets at risk. Because 63 percent of the W76 stockpile is being added the new fuze, if Admiral Nanos is correct, the U.S. inventory of reentry vehicles with hard target kill capability will increase from 400 today to 2,400 in 2021.

Sizing the Arsenal

The disclosure of the 63 percent number adds new information about how the administration envisions the structure of the future nuclear arsenal. Under the SORT agreement signed with Russia in 2002, no more than 2,200 strategic warheads may be operationally deployed by 2012. Yet the total stockpile will be significantly larger, about two and a half times, and include an estimated 5,467 warheads.

|

|

|

|

The government has only recently begun to show pictures of the W76 reentry vehicle. Los Alamos National Laboratory has published a drawing of a W76 interior layout (left), and Sandia National Laboratories has published photographs of the Mk4A reentry body (right). |

Under SORT, the Navy plans to deploy up to an estimated 1,150 warheads on 12 ballistic missile submarines (an average of four warheads per missile). Another two submarines will normally be in overhaul. Approximately 750 of the warheads will be W76-1 with the balance made up by the more powerful W88 warheads. Because SORT doesn’t set limits on reserve warheads or regulate how Russia and the United States can distribute their nuclear weapons below the ceiling, most of the planned W76-1 warheads will not be deployed but kept in storage as a “hedge” against a nuclear-armed adversary suddenly increasing its nuclear arsenal. The 63 percent production plan suggests that the administration wants to retain the capability to increase the warhead loading to as much as eight warheads per missile, the same number it deployed during the Cold War. Another reason for retaining spare W76 warheads is to have replacement warheads in case of technical failure of deployed warheads.

The administration has proposed to replace some of the W76s with the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW-1) to increase the “diversity” of the type of warheads at sea. If Congress approves RRW-1 production, the second half of the 76-1 production plan would probably be changed to RRW-1 warheads beginning (under current plans) in 2014, in which case the future sea-based posture would be made up of a mix of W76-1, W88 and RRW-1 warheads.

In Congress both the Senate and House have called for a review of U.S. nuclear policy to ensure the right size and role of the nuclear posture. The 63 percent W76-1 production set by the 2005 Strategic Capabilities Assessment would appear to preempt that effort.

Background:

Targeting Missile Defense Systems

By Hans M. Kristensen

The now month-long clash between Russia and the West over U.S. plans to build a missile defense system in Europe should warn us that – despite important progress in some areas – Cold War thinking is alive and well.

The missile defense system, Moscow says, is but the latest step in a gradual military encroachment on Russian borders by NATO, and could well be used to shoot down Russian ballistic missiles. The head of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces and President Putin have suggested that Russia might target the defenses with nuclear weapons. The United States has rejected the complaints insisting that Russia has nothing to fear and that the defenses will only be used against Iranian ballistic missiles. European allies have complained that the Russian threats are unacceptable and have no place in today’s Europe.

That may be true, but the reactions have revealed a frightening degree of naiveté about strategic war planning in the post-Cold War era, a widespread belief that such planning has somehow stopped. It has certainly changed, but all the major nuclear weapon states insist that they must hedge against an uncertain future and continue to adjust their strike plans against potential adversaries that have weapons of mass destruction. Russia continues to plan against the West and the West continues to plan against Russia. The plans are not the same that existed during the Cold War, but they are strike plans nonetheless.

The argument made by some officials that missile defense systems are merely defensive and don’t threaten anyone is disingenuous because it glosses over a fact that all planners know very well: Even limited missile defenses become priority targets if they can disturb other important strike plans. The West concluded that very early on in its military relationship with Russia.

Cold War Targeting of Missile Defense Systems

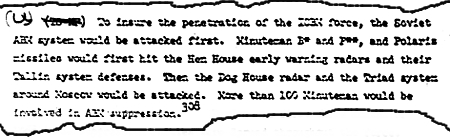

In 2003, I received a declassified Strategic Air Command document that showed how the United States reacted when the Soviet Union built a limited missile defense system back in the late 1960s. The response was overwhelming: A nuclear strike plan that included more than 100 ICBMs plus an unknown number of SLBMs to overwhelm and destroy the Soviet interceptors and radars. Based on the declassified information, two colleagues and I estimated in an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the total strike plan involved approximately 130 nuclear warheads with a total combined yield of some 115 megatons. Here is how the SAC historian described the plan:

|

|

|

|

“To ensure the penetration of the ICBM force, the Soviet ABM system would be attacked first. Minuteman E and F and Polaris missiles would first hit the Hen House early warning radars, and their Tallin system defenses [SA-5 SAM, ed.]. Then the Dog House radar and the Triad system around Moscow would be attacked. More than 100 Minuteman would be involved in the ABM suppression.” |

The Soviet ABM system back then consisted of about fifteen facilities, including eight launch sites around Moscow with a total of 64 nuclear-tipped interceptors, half a dozen SA-5 launch complexes (later found not to have much ABM capability) near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and at least three large early warning radars. Each of these surface facilities were highly vulnerable to the blast effect from a single nuclear warhead, so the large number of ICBMs was mainly needed to “suppress” (overwhelm) the interceptors.

In the late 1980s, the Soviets upgraded they system by moving 32 remaining interceptors at four sites into underground silos (see Figure 2) and adding 68 shorter-range nuclear-tipped interceptors at five new sites closer to Moscow. This hardened and dispersed the interceptors, requiring U.S. planners to upgrade their strike plan, which probably ballooned to more than 200 warheads (although with less total yield due to more accurate missiles with less powerful warheads).

|

|

|

|

Four long-range Gorgon interceptor site crescent Moscow toward the northwest. The 217-mile (350-kilometer) range Gorgon carries a 1 Megaton warhead. The site shown here is near Poryadino southwest of Moscow. There are unconfirmed rumors that the interceptors have been removed and the system is in the process of decommissioning. |

The 68 shorter-range (50 miles, 80 km) interceptors added to the system in the late 1980s were the nuclear-armed Gazelle. Each missile carried a 10-kiloton warhead. The five launch sites, which are still thought to be operational, are positioned in a circle around Moscow approximately 13 miles (23 kilometers) from the center of the city. The 68 interceptors are deployed in hardened silos, 16 at two sites (Northwest and Southeast), and 12 at each of the other three sites. Public uncertainty about the location of the fifth site was recently resolved by a satellite image showing the site next to the Pill Box radar north of Moscow.

|

|

|

|

Five launch sites with Gazelle interceptors in hardened silos are located in a circle around Moscow as part of the A-135 ABM system. The sites have either 12 silos, like the Southwestern site (top) near Moscow Vnukovo airport, or 16. The fifth site (bottom) next to the Pill Box ABM radar north of Moscow has 12 silos, and is depicted in the Pentagon drawing (insert). |

All of this happened during the Cold War and many things have changed, but the basic motivation for targeting a limited missile defense system then was the same as today: The Soviet ABM system was entirely defensive and couldn’t threaten anyone (to paraphrase a characterization frequently use by U.S. and NATO officials to justify their missile defense plans today), but it could disturb the main ICBM attack on Moscow and military facilities downrange. That made it a top-priority target. And even though U.S. planners suspected that the system was not very efficient, they committed about 10 percent of the entire ICBM force to destroy it. To the extent the Russia ABM is operational, U.S. nuclear strike plans probably still target it today.

|

Figure 4: |

||

|

||

| Type | Designation, Location | Remarks |

| Interceptor | ||

| Gorgon (SH-11/ABM-4)* | – E05, 6 miles (9 km) southwest of Karabanovo, at 56°14’39.51″N, 38°34’41.75″E | |

| – E24, 4 miles (6.5 km) northwest of Poryadino, at 55°20’58.31″N, 36°28’50.28″E | ||

| – E31, 6 miles (9.6 km) north of Nudol Sharino, at 56° 9’0.18″N, 36°30’13.08″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| – E33, east of Klin, at 56°20’30.03″N, 36°47’35.21″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| Gazelle (SH-08/ABM-3) | – South of Ashcherino, at 55°34’40.06″N, 37°46’17.89″E | |

| – 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Kaliningrad, at 55°52’41.63″N, 37°53’37.51″E | ||

| – 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Kartmazovo, at 55°37’31.81″N, 37°23’19.99″E | ||

| – Korostovo, at 55°54’6.00″N, 37°18’28.33″E | ||

| – 6 miles (9.6 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’50.69″N, 37°47’12.01″E | ||

| Radar** | ||

| Pill Box (Don-2N) | – 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’23.48″N, 37°46’12.51″E | |

| To view satellite images of all these sites, click here. * There are unconfirmed rumors that the Gorgon interceptors have been removed from the system. ** Other forward-based early-warning radars are not included in this overview. Two older radars (Dog House and Cat House) are no longer operational. |

||

Now history repeats itself, but the table has been turned. Today it is the United States building a limited missile defense system (more capable than the Soviet system, but focused on “rogue” state missiles), and it is the Russians who say they need to target it to maintain the effectiveness of their deterrent. The Cold War may be over, but military and policy planners in both countries still think in Cold War terms.

Russia’s Real Concerns Today

Most of the current debate has focused on whether the missile defense system could disrupt Russia’s deterrent against the United States. Although this may be a concern to Russian planners in the long run, their objections probably have more to do with the capability of the system to disrupt limited strikes against France or the United Kingdom. Russian nuclear strike plans against each of those smaller nuclear powers probably include only a few ICBMs, but their flight path would take them right over the planned interceptors (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: |

|

|

The Russian objections to the proposed US anti-ballistic missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic seem more linked to potential Russian strike plans against British and French nuclear forces than to strike plans against the United States. The trajectories for a hypothetical ICBM attack against French and British nuclear submarines bases pass over the proposed U.S. missile defense system in Europe. |

Russian planners are probably also thinking ahead. By 2015, under current plans, Russia’s ICBM force is expected to have declined from about 480 missiles today to approximately 150. Significantly less than the 450 the United States plans to retain. This, of course, will have no real implications for Russia’s security, but for Russian planners it means that a European ballistic missile defense system with 10 interceptors (that could quickly be expanded) and 21 interceptors at Fort Greely in Alaska (and silos already dug for more) suddenly doesn’t seem so limited anymore. Indeed, if Russia’s statements about targeting a future missile defense system in Europe are genuine, then the U.S. interceptors in Alaska are probably already targeted by Russian missiles.

Implications

There’s probably a fair amount of chest beating in the Russian statements, especially because Russia has little to gain from antagonistic relations with the West in the long run. Putin’s recent “offer” to include Russian radars in the Western defense plans suggests he is trying to find a way out of the stalemate, although not necessarily the way out that Western governments would like to see.

It would, of course, be much simpler if the Russians “just got over it” and accepted Western missile defenses as a fact of life. But they haven’t, and there are clear signs that U.S. missile defense plans have already influenced Russian military planning. An eerie feeling is emerging in Washington that the Russian “experiment” may be over and that Russia, instead of becoming a full partner or a full enemy, is entering a new assertive period intent on acting as a counterbalance to current U.S. foreign policy. That may not necessarily be a bad thing, unless of course it plays out in the form of military posturing.

Western claims that Russia has nothing to fear, although genuine, miss the point: They apparently fear something enough to publicly use it to underscore their own capability. East and West need to figure out what has gone wrong and how to get out of this mess before strategic antagonism becomes a prominent policy feature for the long haul. The fact that we’re even having this debate nearly two decades after the Cold War ended shows that both countries have failed miserably to move beyond Cold War posturing and planning principles.

Background: The Protection Paradox | Russian Nuclear Forces, 2007 | Pavel Podvig’s Analysis

United States Removes Nuclear Weapons From German Base, Documents Indicate

|

|

The United States appears to have quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base. Here a B61 nuclear bomb is loaded unto a C-17 cargo aircraft. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force has removed its main base at Ramstein in Germany from a list of installations that receive periodic nuclear weapons inspections, indicating that nuclear weapons previously stored at the base may have been removed and withdrawn to the United States.

If correct, the withdrawal reduces the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe to an estimated 350 B61 bombs, or roughly equivalent to the size of the entire French nuclear weapons inventory.

New Nuclear Inspection List

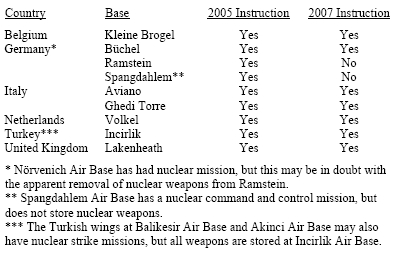

The new nuclear inspection list is contained in the unclassified instruction Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visit (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visit (FEV) Program Management published by the U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) on January 29, 2007. The instruction supersedes an earlier version from March 29, 2005, which did include Ramstein Air Base.

The NSSAV team includes 14-31 inspectors with expertise in the different areas of nuclear weapons mission management. The NSSAV normally takes place six months prior to the a Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI), and the visit is intended to help prepare the unit for the much more rigid NSI, which units with nuclear weapons mission responsibilities must pass at least every 18 months to remain certified to handle and store nuclear weapons. During the visit, which normally lasts a week, the NSSAV team observes and evaluates how the unit conducts day-to-day operations and administers nuclear surety program management. A typical visit includes uploading and downloading of training nuclear weapons on strike aircraft.

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visits (FEV) Program Management, January 29, 2007; U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NS SAV) and Functional Expert Visits |

A Brief History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

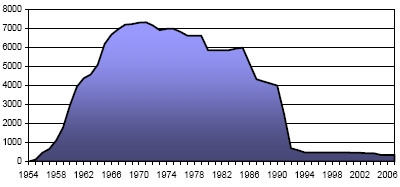

The current number of approximately 350 nuclear weapons is only a fraction of the force level the United States deployed in Europe during the Cold War. That level reached a peak of 7,300 weapons in 1971. The number dropped to 4,000 by the end of the Cold War in 1990, plunged to 700 in 1992, and leveled off at approximately 480 weapons (all bombs) in 1994. This ended the dramatic period of nuclear disarmament initiatives, which has since been replaced by a period of relative stability with slow and gradual reductions happening mainly due to base closures rather than arms control initiatives.

One of the last acts of the Clinton administration in late 2000 was to authorize deployment of 480 nuclear bombs at nine bases in seven European NATO countries. Twenty of the bombs were withdrawn in 2001 after Greece pulled out of the NATO nuclear strike mission, and another 20 were withdrawn in 2003 when Germany closed Memmingen Air Base.

The Bush administration updated the deployment authorization for Europe in May 2004 to reflect these changes, and it is possible that the authorization may have cleared the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base. But as of late March 2005, Ramstein was still on the updated list of installations receiving nuclear surety staff assistance visits. The report U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe published by the Natural Resources Defense Council in February 2005 estimated 440-480 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe.

|

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 1954-2007 |

|

| The U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe peaked in 1971 at 7,300 weapons, was reduced significantly a decade and a half ago, but has remained comparatively stable since then. |

Then in May 2005, the German magazine Der Spiegel cited unnamed German defense officials saying that the U.S. had quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base during major construction work at the base. The assumption was that the move was temporary, but the German officials hoped they would never return. Their wish seems to have come through with Ramstein’s removal from the updated Air Force instruction published in January 2007.

Both the U.S. government and NATO have always refused to disclose the number of weapons deployed in Europe but occasionally have provided the approximate range of the force level or the percentage of reduction since the Cold War. In an interview with Italian RAINEWS in April 2007, NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts also refused to disclose the number weapons, but explained: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

Seen in Cold War context, 350 bombs may not seem like a lot, but for the post-Cold War era it is a significant force. It is roughly equivalent is size to the entire French nuclear arsenal, larger than the Chinese nuclear arsenal, and it is larger that the nuclear arsenals of all the three non-NPT countries Israel, India and Pakistan combined.

Recent Reaffirmation of Nuclear Mission

Despite the apparent reduction, NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) as recently as June 15, 2007, reaffirmed the importance of deploying U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. NPG stated that the purpose of the weapons is to “preserve peace and prevent coercion and any kind of war,” and that NATO places “great value” on the U.S. deployment in Europe. The NPG did not identify any particular enemy that the weapons are intended to protect against, but instead said they “provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”

|

|

|

|

The only nuclear weapons storage site in Germany now appears to be Büchel Air Base, where theft – not enemy attack – is the main threat, as practiced by these security forces in February 2007. |

Germany’s Nuclear Decline

The apparent withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base also raises questions about the continued nuclear strike mission of the German Tornado squadron at Nörvenich Air Base. The base previously stored nuclear weapons, but they were moved to Ramstein in 1995 with the intent that they could quickly be returned to Nörvenich if necessary. A withdrawal from Ramstein would indicate that the 31st Wing at Nörvenich probably no longer has a nuclear strike mission, and that Germany’s contribution to NATO nuclear mission now is reduced to Büchel Air Base.

A reduction to a single German nuclear base with “only” 20 nuclear bombs is a dramatic change from the late-1980s, when more than 2,570 nuclear weapons were deployed at dozens of locations across the country. The latest withdrawal follows a political seachange in German voters’ views on nuclear weapons in the country. A poll published by Der Spiegel in 2005 revealed an overwhelming support across the political spectrum for a complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Germany.

The German government said in May 2005 that it would raise the issue of continued deployment within NATO, but officials later told Der Spiegel that the government had changed its mind. Yet the withdrawal from Ramstein indicates that the government has been more proactive than thought or that the Bush administration “got the message” and decided not to return the weapons. The withdrawal reduces Germany from the status of a major nuclear host nation to one on par with Belgium and the Netherlands, both of which also only have one nuclear base. The German government can now safely decide to follow Greece, which in 2001 unilaterally left NATO’s nuclear club. This in turn would open the possibility that Belgium (and likely also the Netherlands) will follow suit, essentially throwing NATO’s long-held principle of nuclear burdensharing into disarray.

A New Southern Focus

For now, the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base shifts the geographic focus of NATO’s nuclear posture to the south. Before the withdrawal, a clear majority of NATO’s nuclear weapons were deployed in Northern and Central Europe. After the withdrawal, however, more than half (51%) of the weapons are deployed in Southern Europe along the Eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea in Italy and Turkey.

The geographic shift has implications for international security issues that NATO countries are actively involved in, such as the attempts to create a Mediterranean Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, and the efforts to persuade countries like Iran not to develop nuclear weapons. The new southern focus of NATO’s nuclear posture will make it harder to persuade other countries in the region to show constraint.

Background: Satellite Images of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Bases Europe | U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe (report from 2005)