Domestic Terrorism: Some Considerations

The problem of domestic terrorism is distinct from that of foreign terrorism because of the constitutional protections enjoyed by U.S. persons, the Congressional Research Service explained last week.

“Constitutional principles — including federalism and the rights to free speech, free association, peaceable assembly, petition for the redress of grievances — may complicate the task of conferring domestic law enforcement with the tools of foreign intelligence gathering.” See Domestic Terrorism: Some Considerations, CRS Legal Sidebar, August 12, 2019.

Some other noteworthy new publications from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Convergence of Cyberspace Operations and Electronic Warfare, CRS In Focus, August 13, 2019

Renewed Great Power Competition: Implications for Defense–Issues for Congress, updated August 5, 2019

U.S. Foreign Aid to Israel, updated August 7, 2019

U.S.-North Korea Relations, CRS In Focus, updated August 13, 2019 (which notes that “Pyongyang appears to be losing its ability to control information inflows from the outside world.”)

Russia’s Nuclear Weapons: Doctrine, Forces, and Modernization, August 5, 2019

Classified Anti-Terrorist Ops Raise Oversight Questions

Last February, the Secretary of Defense initiated three new classified anti-terrorist operations intended “to degrade al Qaeda and ISIS-affiliated terrorists in the Middle East and specific regions of Africa.”

A glimpse of the new operations was provided in the latest quarterly report on the U.S. anti-ISIS campaign from the Inspectors General of the Department of Defense, Department of State, and US Agency for International Development.

The three classified programs are known as Operation Yukon Journey, the Northwest Africa Counterterrorism overseas contingency operation, and the East Africa Counterterrorism overseas contingency operation.

Detailed oversight of these programs is effectively led by the DoD Office of Inspector General rather than by Congress.

“To report on these new contingency operations, the DoD OIG submitted a list of questions to the DoD about topics related to the operations, including the objectives of the operations, the metrics used to measure progress, the costs of the operations, the number of U.S. personnel involved, and the reason why the operations were declared overseas contingency operations,” the joint IG report said.

DoD provided classified responses to some of the questions, which were provided to Congress.

But “The DoD did not answer the question as to why it was necessary to designate these existing counterterrorism campaigns as overseas contingency operations or what benefits were conveyed with the overseas contingency operation designation.”

Overseas contingency operations are funded as “emergency” operations that are not subject to normal procedural requirements or budget limitations.

“The DoD informed the DoD OIG that the new contingency operations are classified to safeguard U.S. forces’ freedom of movement, provide a layer of force protection, and protect tactics, techniques, and procedures. However,” the IG report noted, “it is typical to classify such tactical information in any operation even when the overall location of an operation is publicly acknowledged.”

“We will continue to seek answers to these questions,” the IG report said.

Domestic Terrorism: An Overview, & More from CRS

The problem of “domestic terrorism” is examined in a new report from the Congressional Research Service, along with an assessment of the government’s difficulty in addressing it.

“Since the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11), domestic terrorists–people who commit crimes within the homeland and draw inspiration from U.S.-based extremist ideologies and movements–have not received as much attention from federal law enforcement as their violent jihadist counterparts,” the report says.

Among other obstacles to an effective response, “The federal government lacks a process for publicly designating domestic terrorist organizations.” See Domestic Terrorism: An Overview by CRS Specialist Jerome P. Bjelopera, August 21, 2017.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Confederate Names and Military Installations, CRS Insight, August 22, 2017

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act: Selected Military Personnel Issues, August 22, 2017

Human Rights in China and U.S. Policy: Issues for the 115th Congress, July 17, 2017

North Korean Cyber Capabilities: In Brief, August 3, 2017

Justice Department’s Role in Cyber Incident Response, August 23, 2017

Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP): History and Overview, updated August 17, 2017

Remedies for Patent Infringement, July 18, 2017

Russia: Background and U.S. Interests, updated August 21, 2017

Terrorism and the First Amendment, & More from CRS

Incitement to commit an imminent act of violence is not protected by the First Amendment, and may be restricted by the government. But advocacy of terrorism that stops short of inciting “imminent” violence probably falls within the ambit of freedom of speech. A new report from the Congressional Research Service examines the legal framework for evaluating this issue.

“Many policymakers, including some Members of Congress, have expressed concern about the influence the speech of terrorist groups and the speech of others who advocate terrorism can have on those who view or read it,” CRS notes. Yet, “Significant First Amendment freedom of speech issues are raised by the prospect of government restrictions on the publication and distribution of speech, even speech that advocates terrorism.”

Essentially, in order for punishment of speech advocating violence to be constitutional, “the speaker must both intend to incite a violent or lawless action and that action must be likely to imminently occur as a result.”

At the same time, “government restrictions on advocacy that is provided to foreign terrorist organizations as material support have been upheld as permissible. This report will discuss relevant precedent that may limit the extent to which advocacy of terrorism may be restricted. The report will also discuss the potential application of the federal ban on the provision of material support to foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) to the advocacy of terrorism and the dissemination of such advocacy by online service providers like Twitter or Facebook.”

See The Advocacy of Terrorism on the Internet: Freedom of Speech Issues and the Material Support Statutes, September 8, 2016.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Digital Searches and Seizures: Overview of Proposed Amendments to Rule 41 of the Rules of Criminal Procedure, updated September 8, 2016

Post-Heller Second Amendment Jurisprudence, September 7, 2016

Immigration Legislation and Issues in the 114th Congress, updated September 9, 2016

Interior Immigration Enforcement: Criminal Alien Programs, September 8, 2016

The Endangered Species Act: A Primer, updated September 8, 2016

Biologics and Biosimilars: Background and Key Issues, September 7, 2016

Corporate Inversions: Frequently Asked Legal Questions, September 7, 2016

FATCA Reporting on U.S. Accounts: Recent Legal Developments, September 7, 2016

National Monuments and the Antiquities Act, updated September 7, 2016

U.S. Farm Income Outlook for 2016, updated September 7, 2016

The 2016 G-20 Summit, CRS Insight, September 8, 2016

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, September 7, 2016

Argentina: Background and U.S. Relations, updated September 6, 2016

Burma Holds Peace Conference, CRS Insight, September 8, 2016

EU State Aid and Apple’s Taxes, CRS Insight, September 2, 2016

Leadership Succession in Uzbekistan, CRS Insight, September 6, 2016

Marine Corps Amphibious Combat Vehicle (ACV) and Marine Personnel Carrier (MPC): Background and Issues for Congress, updated September 9, 2016

Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV): Background and Issues for Congress, updated September 9, 2016

NASA: FY2017 Budget and Appropriations, September 6, 2016

Information Warfare: Russian Activities, CRS Insight, September 2, 2016

DoD Gets Go-Ahead to Counter Islamic State Messaging

There are “substantial gaps” in the ability of the Department of Defense to counter Islamic State propaganda and messaging, the Commander of U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM) informed Congress earlier this year.

But now Congress has moved to narrow some of those gaps.

Until recently, the Pentagon’s authority to act in this area had been deliberately curtailed by Congress in order to preserve a civilian lead role for the State Department’s public diplomacy program.

“Congress has expressed concern with DOD engaging violent extremist propaganda on the Internet, except in limited ways,” wrote General Joseph L. Votel, the SOCOM Commander, in newly published responses to questions for the record from a March 18, 2015 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee (at page 69).

“They [Congress] tend to view… efforts to influence civilians outside an area of conflict as Public Diplomacy, the responsibility of the Department of State or Broadcasting Board of Governors.”

By contrast, “We [at US Special Operations Command] believe there is a complementary role for the Department of Defense in this space which acknowledges the need for a civilian lead, but allows DOD to pursue appropriate missions, such as counter-recruitment and reducing the flow of foreign fighters,” he wrote.

General Votel suggested that “An explicit directive from Congress outlining the necessity of DOD to engage in this space would greatly enhance our ability to respond.”

Now he has it.

Without much fanfare, something like the directive from Congress that General Votel requested was included in the FY2016 defense authorization bill that was signed into law by President Obama on November 25:

“The Secretary of Defense should develop creative and agile concepts, technologies, and strategies across all available media to most effectively reach target audiences, to counter and degrade the ability of adversaries and potential adversaries to persuade, inspire, and recruit inside areas of hostilities or in other areas in direct support of the objectives of commanders.”

That statement was incorporated in Section 1056 of the 2016 Defense Authorization Act, which also directed DOD to perform a series of technology demonstrations to advance its ability “to shape the informational environment.”

Even with the requested authority, however, DOD is poorly equipped to respond to Islamic State propaganda online, General Votel told the House Armed Services Committee.

“Another gap exists in [DOD’s] ability to operate on social media and the Internet, due to a lack of organic capability” in relevant languages and culture, not to mention a compelling alternative vision that would appeal to Islamic State recruits. The Department will be forced to rely on contractors, even as it pursues efforts to “improve the Department’s ability to effectively operate in the social media and broader online information space.”

And even with a mature capacity to act, DOD’s role in counter-propaganda would still be hampered by current policy when it comes to offensive cyber operations, for which high-level permission is required, he said.

“The ability to rapidly respond to adversarial messaging and propaganda, particularly with offensive cyberspace operations to deny, disrupt, degrade or corrupt those messages, requires an Execute Order (EXORD) and is limited by current U.S. government policies.”

“The review and approval process for conducting offensive cyberspace operations is lengthy, time consuming and held at the highest levels of government,” Gen. Votel wrote. “However, a rapid response is frequently required in order to effectively counter the message because cyber targets can be fleeting, access is dynamic, and attribution can be difficult to determine.”

No immediate solution to that policy problem is at hand, as far as is known.

The difficulty that the U.S. government has had in confronting the Islamic State on the level of messaging, influence or propaganda is more than an embarrassing bureaucratic snafu; it has also tended to expedite the resort to violent military action.

“Overmatched online, the United States has turned to lethal force,” wrote Greg Miller and Souad Mekhennet of the Washington Post, in a remarkable account of the Islamic State media campaign. (“Inside the surreal world of the Islamic State’s propaganda machine,” November 20).

* * *

The House Armed Services Committee now produces the most informative hearing volumes of any congressional committee in the national security domain. Beyond the transcripts of the hearings themselves, which are of varying degrees of interest, the published volumes typically include additional questions that elicit substantive new information in the form of agency responses to questions for the record.

The new hearing volume on US Special Operations Command notes, for example:

* USSOCOM currently deploys 20-30 Military Information Support Teams to embassies around the world. They are comprised of forces “specially trained in using information to modify foreign audiences’ behavior” [page 69].

* “Only one classified DE [directed energy] system is currently fielded by USSOCOM and being used in SOF operations” [page 61]. Other directed energy technology development programs have failed to meet expectations.

* Advanced technologies of interest to SOCOM include: signature reduction technologies; strength and endurance enhancement; unbreakable/unjammable, encrypted, low probability to detect/low probability of intercept communications; long-range non-lethal vehicle stopping; clandestine non-lethal equipment and facility disablement/defeat; advanced offensive and defensive cyber capabilities; weapons of mass destruction render safe; chemical and biological agent defeat [page 77].

Another recently published House Armed Services Committee hearing volume is “Cyber Operations: Improving the Military Cybersecurity Posture in an Uncertain Threat Environment.”

Tools for Deterring Terrorist Travel (CRS)

A new report issued by the Congressional Research Service describes the various procedures that the U.S. government can use “to prevent individuals from traveling to, from, or within the United States to commit acts of terrorism.”

See Legal Tools to Deter Travel by Suspected Terrorists: A Brief Primer, CRS Legal Sidebar, November 16, 2015.

In light of the Paris attacks, CRS also updated its short report on European Security, Islamist Terrorism, and Returning Fighters, CRS Insights, November 16, 2015.

The False Hope of Nuclear Forensics? Assessing the Timeliness of Forensics Intelligence

Nuclear forensics is playing an increasing role in the conceptualization of U.S. deterrence strategy, formally integrated into policy in the 2006 National Strategy on Combatting Terrorism (NSCT). This policy linked terrorist groups and state sponsors in terms of retaliation, and called for the development of “rapid identification of the source and perpetrator of an attack,” through the bolstering of attribution via forensics capabilities.12 This indirect deterrence between terrorist groups and state sponsors was strengthened during the 2010 Nuclear Security Summit when nuclear forensics expanded into the international realm and was included in the short list of priorities for bolstering state and international capacity. However, while governments and the international community have continued to invest in capabilities and databases for tracking and characterizing the elemental signatures of nuclear material, the question persists as to the ability of nuclear forensics to contribute actionable intelligence in a post-detonation situation quickly enough, as to be useful in the typical time frame for retaliation to terrorist acts.

In the wake of a major terrorist attack resulting in significant casualties, the impetus for a country to respond quickly as a show of strength is critical.3 Because of this, a country is likely to retaliate based on other intelligence sources, as the data from a fully completed forensics characterization would be beyond the time frame necessary for a country’s show of force. To highlight the need for a quick response, a quantitative analysis of responses to major terrorist attacks will be presented in the following pages. This timeline will then be compared to a prospective timeline for forensics intelligence. Fundamentally, this analysis makes it clear that in the wake of a major nuclear terrorist attack, the need to respond quickly will trump the time required to adequately conduct nuclear forensics and characterize the origins of the nuclear material. As there have been no instances of nuclear terrorism, a scenario using chemical, biological, and radiological weapons will be used as a proxy for what would likely occur from a policy perspective in the event a nuclear device is used.

This article will examine existing literature, outline arguments, review technical attributes,4 examine the history of retaliation to terrorism, and discuss conclusions and policy recommendations. This analysis finds that the effective intelligence period for nuclear forensics is not immediate, optimistically producing results in ideal conditions between 21 and 90 days, if at all. The duration of 21 days is also based on pre-detonation conditions, and should be considered very, if not overly, optimistic. Further, empirical data collected and analyzed suggestions that the typical response to conventional terrorism was on average 22 days, with a median of 12 days, while terrorism that used chemical, biological, or radiological materials warranted quicker response – an average of 19 days and a median of 10 days. Policy and technical obstacles would restrict the effectiveness of nuclear forensics to successfully attribute the origin of a nuclear weapon following a terrorist attack before political demands would require assertive responses.

Literature

Discussions of nuclear forensics have increased in recent years. Non-technical scholarship has tended to focus on the ability of these processes to deter the use of nuclear weapons (in particular by terrorists), by eliminating the possibility of anonymity.5 Here, the deterrence framework is an indirect strategy, by which states signal guaranteed retribution for those who support the actions of an attacking nation or non-state actor. This approach requires the ability to provide credible evidence both as to the origin of material and to the political decision to transfer material to a non-state actor. As a result of insufficient data available on the world’s plutonium and uranium supply, as well as the historical record of the transit of material, nuclear forensics may not be able to provide stand-alone intelligence or evidence against a supplying country. However, scholars have largely assumed that the ‘smoking gun’ would be identifiable via nuclear forensics. Michael Miller, for example, argues that attribution would deter both state actors and terrorists from using nuclear weapons as anyone responsible will be identified via nuclear forensics.6 Keir Lieber and Daryl Press have echoed this position by arguing that attribution is fundamentally guaranteed due to the small number of possible suppliers of nuclear material and the high attribution rate for major terrorist attacks.7 There is an important oversight from both a technical and policy perspective in these types of arguments however.

First, the temporal component of nuclear forensics is largely ignored. The processes of forensics do not produce immediate results. While the length of time necessary to provide meaningful intelligence differs, it is unlikely that nuclear forensics will provide information as to the source of the device in the time frame required by policymakers, who in the wake of a terrorist attack will need to respond quickly and decisively. This is likely to decrease both the credibility of forensics information and its usefulness if the political demand requires a leader to act promptly.

Secondly, the existence and size of a black-market for nuclear and radiological material is generally dismissed as a non-factor as it is assumed that a complex weapon provided by a state with nuclear weapon capacity is necessary. While it is acknowledged that a full-scale nuclear device capable of being deployed on a delivery device certainly requires advanced technical capacity that a terrorist organization would likely not have, a very crude weapon is possible. Devices such as a radiological dispersal device or a low yield nuclear device, or even a failed (fizzle) nuclear weapon, would still create a desirable outcome for a terrorist group in that panic, death, and devastating economic and societal consequences would ensue. Further, black market material could the ideal method of weaponization, as its characterization and origin-tracing would prove nearly impossible due to decoupling, and thus confusion, between perpetrator and originator.

It is evident that there is a gap between a robust technical understanding and arguments as to the viability and speed of nuclear forensics in providing actionable intelligence. This gap could lead to unrealistic expectations in times of crisis.

Technical Perspective

This section will outline the technologies, processes, and limitations of forensics in order to better inform its potential for contributing meaningful data in a crisis involving nuclear material. It should be noted that most open-source literature on the processes and capabilities of nuclear forensics come from a pre-detonation position, as specifics on post-denotation procedures and timelines are classified.8 This has resulted in the technical difficulties and inherent uncertainties in the conduct of forensic operations in a post-detonation situation being ignored. The following will attempt to extrapolate the details of the pre-detonation procedures into the post-detonation context in order to posit a potential time frame for intelligence retrieval.

Fundamentally, nuclear forensics is the analysis of nuclear or radiological material for the purposes of documenting the material’s characteristics and process history. With this information, and a database of material to compare the sample to, attribution of the origin of the material is possible.9 Following usage or attempted usage of a nuclear or radiological device, nuclear forensics would examine the known relationships between material characteristics and process history, seeking to correlate characterized material with known production history. While forensics encompasses the processes of analysis on recovered material, nuclear attribution is the process of identifying the source of nuclear or radioactive material, to determine the point of origin and routes of transit involving such material, and ultimately to contribute to the prosecution of those responsible.

Following a nuclear detonation, panic would likely prevail among the general populace and some first responders charged with helping those injured. Those tasked with collecting data from the site for forensic analysis would take time to deploy.10 While National Guard troops are able to respond to aid the population, specialized units are more dispersed throughout the country.11 Nuclear Emergency Support Teams, which would respond in the wake of a nuclear terror attack, are stationed at several of the national laboratories spread around the country. Depending on the location of the attack, response times may vary greatly. The responders’ first step would be to secure the site, as information required for attribution comes from both traditional forensics techniques (pictures, locating material, measurements, etc.) and the elemental forensics analysis of trace particles released from the detonation. At the site, responders would be able to determine almost immediately if it was indeed a full-scale nuclear detonation, a fizzle, or a radiological dispersal device. This is possible by assessing the level of damage and from the levels of radiation present, which can be determined with non-destructive assay techniques and dosimetry. Responders (through the use of gamma ray spectrometry and neutron detection) will be able to classify the type of material used if it is a nuclear device (plutonium versus uranium). With these factors assessed, radiation detectors would need to be deployed to carefully examine the blast site or fallout area to catalogue and extricate radioactive material for analysis. These materials would then need to be delivered to a laboratory capable of handling them.

Once samples arrive at the laboratories, characterization of the material will be undertaken to provide the full elemental analysis (isotopic and phase) of the radioactive material, including major, minor and trace constituents, and a variety of tools that can help classify into bulk analysis, imaging techniques, and microanalysis. Bulk analysis would provide elemental and isotopic composition on the material as a whole, and would enable the identification of trace material that would need to be further analyzed. Imaging tools capture the spatial and textural heterogeneities that are vital to fully characterizing a sample. Finally, microanalysis examines more granularly the individual components of the bulk material.

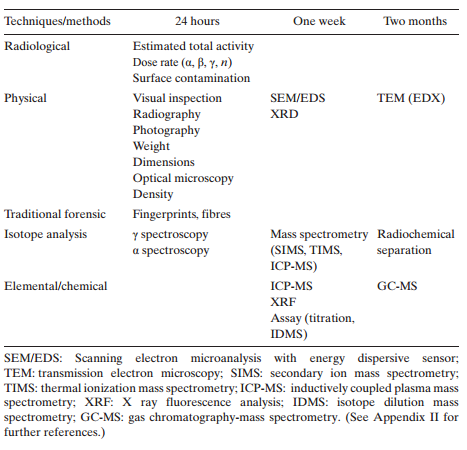

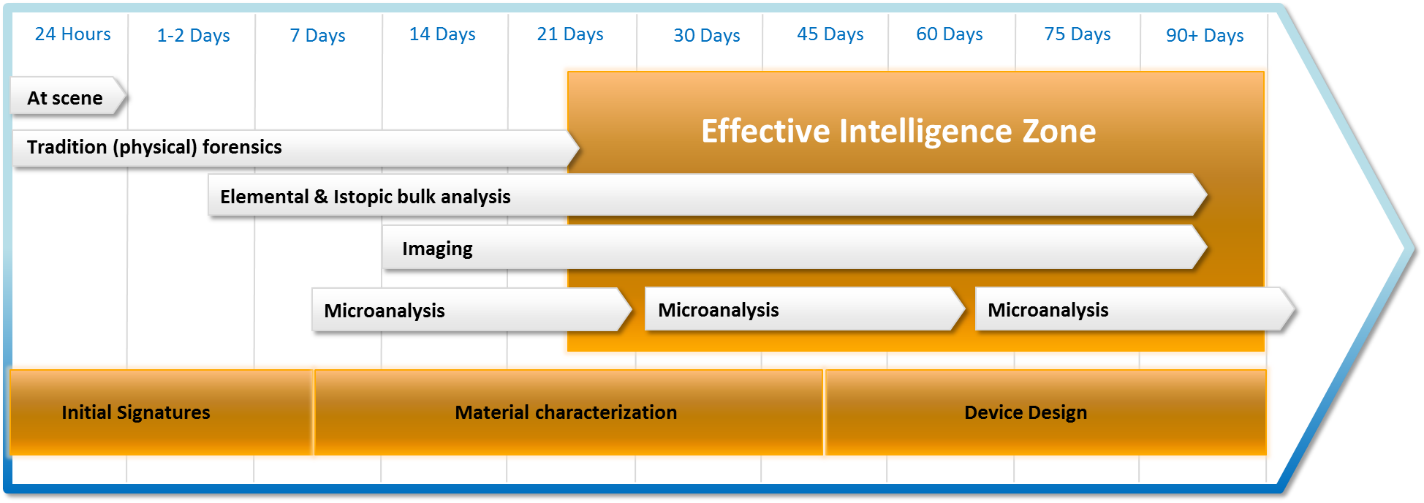

The three-step process described above is critical to assessing the processes the material was exposed to and the origin of the material. The process, the tools used at each stage, and a rough sequencing of events is shown in Figure 1.12 This table, a working document produced by the IAEA, presents techniques and methods that would be used by forensics analysts as they proceed through the three-step process, from batch analysis to microanalysis. Each column represents a time frame in which a tool of nuclear forensics could be utilized by analysts. However, this is a pre-detonation scenario. While it does present a close representation of what would happen post-detonation, some of the techniques listed below would be expected to take longer. This is due to several factors such as the spread of the material, vaporization of key items, and safety requirements for handling radioactive material. These processes take time and deal with small amounts of material at a time which would require a multitude of microanalysis on a variety of elements.

IAEA Suggested Sequence for Laboratory Techniques and Methods

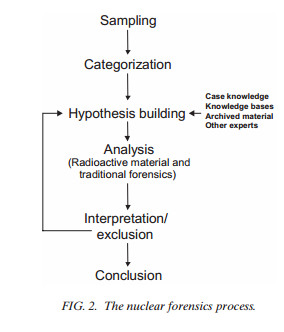

It should also be noted that while nuclear forensics does employ developed best practices, it is not an exact science in that a process can be undertaken and definitive results. Rather, it is an iterative process, by which a deductive method of hypothesis building, testing, and retesting is used to guide analysis and extract conclusions. Analysts build hypotheses based on categorization of material, test these hypotheses against the available forensics data and initiate further investigation, and then interpret the results to include or remove actors from consideration. This can take several iterations. As such, while best practices and proven science drive analysis, the experience and quality of the analyst to develop well-informed hypotheses which can be used to focus more on the investigation is critical to success. A visual representation of the process is seen in Figure 2 below.13

IAEA forensic analysis process

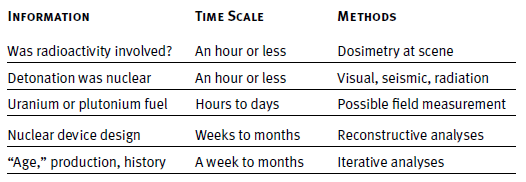

A net assessment by the Joint Working Group of the American Physical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science of the current status of nuclear forensics and the ability to successfully conduct attribution concluded that the technological expertise was progressing steadily, but greater cooperation and integration was necessary between agencies.14 They also provided a simplified timeline of events following a nuclear attack, which is seen in Figure 3.15 Miller also provides a more nuanced breakdown of questions that would arise in a post-detonation situation; however, it is the opinion of the author that his table overstates technical capacity following a detonation and uses optimistic estimates for intelligence.16

Nuclear forensics activities following a detonation

Many of the processes that provide the most insight simply take time to configure, run, and rerun. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, for instance, is able to detect and measure trace organic elements in a bulk sample, a very useful tool in attempting to identify potential origin via varying organics present.17 However, when the material is spread far (mostly vaporized or highly radioactive), it can take time to configure and run successfully. Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS) allows for the measuring of multiple isotopes simultaneously, enabling ratios between isotope levels to be assessed.18 While critically important, this process takes time to prepare each sample, requiring purification in either a chemical or acid solution.

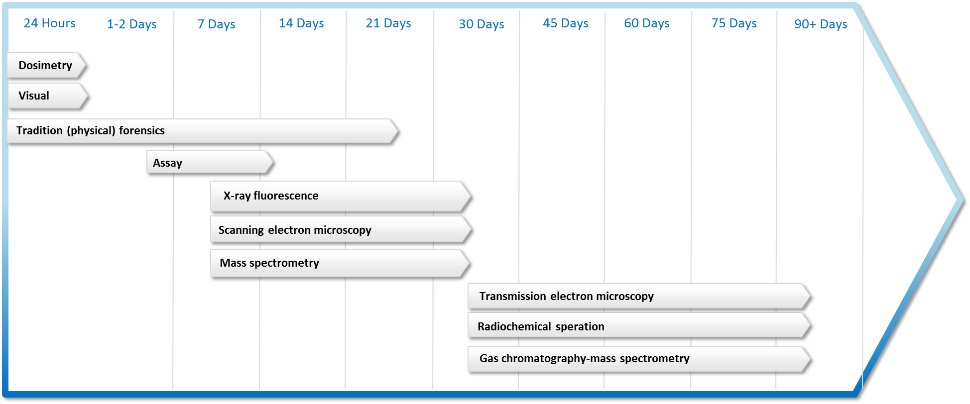

With this broad perspective in mind, how long would it take for actionable intelligence to be produced by a nuclear forensics laboratory following the detonation of a nuclear weapon? While Figure 1 puts output being produced in as little as one week, this would be high-level information and able to eliminate possible origins, but most likely not able to come to definitive conclusion. The estimates of Figure 3 (ranging from a week to months), are more likely as the iterative process of hypothesis testing and the obstacles leading up to the point at which the material arrives at the laboratory, would slow and hamper progress. Further, if the signatures of the material are not classified into a comprehensive database, though disperse efforts are underway, the difficulty in conclusively saying it is a particular actor increases.19 As such, an estimate of weeks to months, as is highlighted in Figures 4 and 5, is an appropriate time frame by which actionable intelligence would be available from nuclear forensics. The graphics below show the likely production times for definitive findings by the forensics processes and outlines a zone of effective intelligence production. How does this align with the time frame of retribution?

Nuclear forensics timeline (author-created figure, compiled from above cited IAEA reports and AAAS report}

Effective Intelligence Zone (author-created figure, compiled from above cited IAEA reports and AAAS report.)

Retaliation Data

How quickly do policymakers act in the wake of a terrorist attack? This question is largely unexplored in the social science literature. However, it is critical to establishing a baseline period in which nuclear forensics would likely need to be able to provide actionable intelligence following an attack. As such, an examination of the retaliatory time to major terrorist attacks will be examined to understand the time frame likely available to forensics analysts to contribute conclusions on materials recovered.

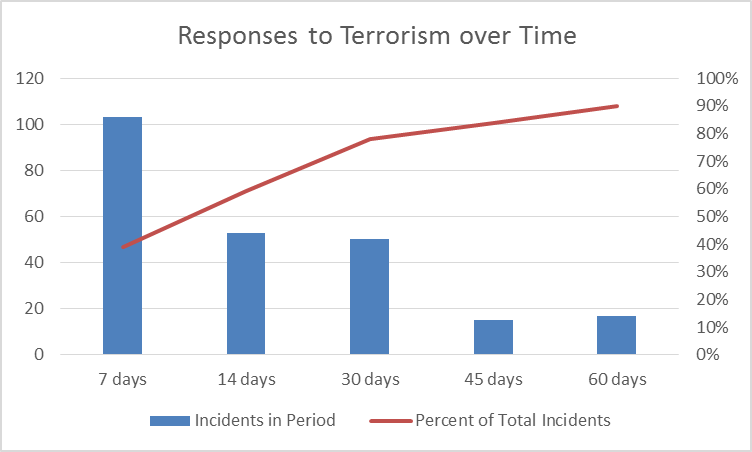

Major terrorist attacks were identified using the Study for Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism Global Terrorism Database.20 As such, the database was selected to return events that resulted in either 50 or more fatalities or over 100 injured. Also removed were cases occurring in Afghanistan or Iraq after 2001 and 2003 due to the indistinguishability of responses to terror attacks and normal operations of war within the data. This yielded 269 observations between 1990 and 2004. Cases that had immediate responses (same day) were excluded as this would indicate an ongoing armed conflict. Summary statistics for this data are as follows:

The identified terrorist events were then located in Gary King’s 10 Million Events data set21, which uses a proven data capture and classification method to catalogue events between 1990 and 2004. Government responses following the attack were then captured. Actions were restricted to only those where the government engaged the perpetrating group. This was done by capturing events classified as the following: missile attack, arrest, assassination, unconventional weapons, armed battle, bodily punishment, criminal arrests, human death, declare war, force used, artillery attack, hostage taking, torture, small arms attack, armed actions, suicide bombing, and vehicle bombing. This selection spans the spectrum of policy responses available to a country following a domestic terror attack that would demonstrate strength and resolve. Additionally, by utilizing a range of responses, it is possible to examine terrorism levied from domestic and international sources, thus enabling the consideration of both law enforcement and military actions. Speech acts, sanctions, and other policy actions that do not portray resolve and action were excluded, as they would typically occur within hours of an attack and would not be considered retaliation.

Undertaking this approached yielded retaliation dates for all observations. The summary statistics and basic outline of response time by tier of causalities are as follows:

Table 2: Summary Statistics Table 3: Casualties by Retaliation Quartile

Immediately, questions arise as to the relationship between retaliation time and destruction inflicted, as well as the time frame available to nuclear forensics analysts to provide intelligence before a response is required. With an average retaliation time of 22 days, this would fall within the 1-2 month time frame for complete analysis. Further, a median retaliation time of 12 days would put most laboratory analysis outside the bounds of being able to provide meaningful data. Figure 6 further highlights this by illustrating that within 30 days of a terrorist attack, 80 percent of incidents will have been responded to with force.

Response Time

One of the fundamental graphics presented in the Lieber and Press article shows that as the number of causalities in a terror attack increases, the likelihood of attribution increases correspondingly. This weakens their arguments for two reasons. First, forensics following a conventional attack would have significantly more data available than in the case of a nuclear attack, due to the destructive nature of the attack and the inability of responders to access certain locales. Secondly, a country that is attacked via unconventional means could arguably require a more resolute and quicker response. In looking at the data, the overall time to retaliation is 21.66 days. This number is significantly smaller when limited to unconventional weapons (19.04 days) and smaller still when the perpetrators are not clearly identified (18.8 days). This highlights the need for distinction between unconventional and conventional attacks, which Lieber and Press neglected in their quantitative section.

To further highlight the point that nuclear forensics may not meet the political demands put upon it in a post-detonation situation, Table 4 highlights the disconnect between conventional and unconventional attacks and existing threats. To reiterate, the term unconventional is used colloquially here as a substitute for CBRN weapons, and not unconventional tactics. In only 37 percent of the cases observed was the threat a known entity or attributed after the fact. This compares to 85 percent for conventional. In all of these attacks, retaliation did occur; allowing the conclusion that with the severity of an unconventional weapon and the unordinary fear that is likely to be produced that public outcry and a prompt response would be warranted regardless of attribution.

As the use of a nuclear weapon would result in a large number of deaths, the question as to whether or not higher levels of casualties influence response time is also of importance. However, no significant correlation is present between retaliation time and any of the other variables examined. Here, retaliation time (in days) was compared with binary variables for whether or not the perpetrators were known, if the facility was a government building or not, if the device used was a bomb or not, and if an unconventional device was used or not. Scale variables used include number of fatalities, injured, and the total casualties from the attack. Of particular note here is the negative correlation between unconventional attacks and effective attribution at time of response; this reemphasizes the above point on attribution prior to retaliation as being unnecessary following an unconventional attack.

Assessment

From this review, the ability of nuclear forensics to provide rapid, actionable intelligence in unlikely. While it is acknowledged that the process would produce gains along the way, an effective zone of intelligence production can be assumed between 21-90 days optimistically. This is highlighted in Figure 5 above, which aligns the effective zone with the processes that would likely provide definitive details. However, this does not align with the average (22 days) and median (12 days) time of response for conventional attacks. More importantly, unconventional attack responses fall well before this effective zone, with an average of 19 days and a median of 10. While the effective intelligence zone is close to these averages of these data points, the author remains skeptical that the techniques to be performed would produce viable data in a shorter time frame presented given the likely condition of the site and the length of time necessary for each run of each technique.22 This woasuld seem to support an argument that the working timelines for actionable data being outside the boundary of average retaliatory time. More examination is necessary to further narrow down the process times, a task plagued with difficulties due to material classification.ass

A secondary argument that can be made when thinking about unattributed terror attacks is that even without complete attribution, a state will retaliate against a known terror, cult, or insurgent organization following a terror attack to show strength and deter further attacks. This was shown to be the case in 34 of 54 observations (63 percent unattributed). While this number is remarkably high, all states were observed taking decisive action against a group. This would tend to negate the perspective that forensics will matter following an attack, as a state will respond more decisively to unconventional attacks than conventional whether attribution has been established or not.

There are also strategic implications for indirect deterrent strategies as well. Indirect deterrence offers a bit more flexibility in the timing of results, but less so in the uncertainty of results, as it will critical in levying guilty claims against a third-party actor. Thus, nuclear forensics can be very useful, and perhaps even necessary, in indirect deterrent strategies if data is available to compare materials and a state is patient in waiting for the results; however, significant delays in intelligence or uncertainty in results may reduce the credibility of accusations and harm claims of guilt in the international context. From a strategic perspective, the emphasis in the United States policy regarding rapid identification that was discussed at the outset of the paper reflects optimism rather than reality.

Policy Recommendations

While nuclear forensics may not be able to contribute information quickly enough to guide policymakers in their retaliatory decision-making following terrorist attacks, nuclear forensics does have significant merit. Nuclear forensics will be able to rule people out. It will be able to guide decisions for addressing the environmental disaster. Forensics also has significant political importance, as it can be used in a post-hoc situation following retaliation to possibly justify any action taken. It will also continue to be important in pre-detonation interdiction situations, where it has been advanced and excelled to-date, providing valuable information on the trafficking of illicit materials.

However, realistic expectations are necessary and should be made known so that policymakers are able to plan accordingly. The public will demand quick action, requiring officials to produce tangible results. If delay is not possible, attribution may not be possible. To overcome this, ensuring policymakers are aware of the technical limitations and hurdles that are present in conducting forensics analysis of radioactive material would help to manage expectations.

To reduce analytical time and improve attribution success rates, further steps should be taken. Continuing to enlarge the IAEA database on nuclear material signatures is critical, as this will reduce analytical time and uncertainty, making more precise attribution possible. Additional resources for equipment, building up analytical capacity, and furthering cooperation among all states to ensure that signatures are catalogued and accessible is critical. The United States has taken great steps in improving the knowledge base on how nuclear forensics is conducted with fellowships and trainings available through the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). While funding constraints are tight, expansion of these programs and targeted recruitment of highly-qualified students and individuals is key. Perhaps, these trainings and opportunities could be expanded to cover individuals that are trained to do analytical work, but is not their primary tasking – like a National Guard for nuclear forensics. DOE and other agencies have similar programs for response capacity during emergencies; bolstering analytical capacity for rapid ramp-up in case of emergency would help to reduce analytical time. However, while these programs may reduce time, some of the delay is inherent in the science. Technological advances in analytics may help, but in the short-term are unavailable. In sum, further work in developing the personnel and technological infrastructure for nuclear forensics is needed; in the meantime, prudence is necessary.

Philip Baxter is currently a PhD Candidate in the International Affairs, Science, and Technology program in the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs at Georgia Tech. He completed his BA in political science and history at Grove City College and a MA in public policy, focusing on national security policy, from George Mason University. Prior to joining the Sam Nunn School, Phil worked in international security related positions in the Washington, DC area, including serving as a researcher at the National Defense University and as a Nonproliferation Fellow at the National Nuclear Security Administration. His dissertation takes a network analysis approach in examining how scientific cooperation and tacit knowledge development impacts proliferation latency. More broadly, his research interests focus on international security issues, including deterrence theory, strategic stability, illicit trafficking, U.S.-China-Russia relations, and nuclear safeguards.

Solidarity with Charlie Hebdo? Subscribe!

What can anyone do in response to the horrific murders of twelve persons associated with the French weekly Charlie Hebdo?

One way of expressing solidarity with the victims, and opposition to the killers, would be to purchase a subscription to the satirical (often deliberately offensive) publication, whether for yourself or for a local library.

In the U.S., subscriptions to Charlie Hebdo are conveniently available through Amazon.com (h/t Jack Shafer).

The surviving staff said that next week’s issue will be published on schedule.

Is ISIL a Radioactive Threat?

In the past several months, various news stories have raised the possibility that the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, also commonly referred to as ISIS) could pose a radioactive threat. Headlines such as “Dirty bomb fears after ISIS rebels seize uranium stash,”1 “Stolen uranium compounds not only dirty bomb ingredients within ISIS’ grasp, say experts,”2 “Iraq rebels ‘seize nuclear materials,’” 3 and “U.S. fears ISIL smuggling nuclear and radioactive materials: ISIL could take control of radioactive, radiological materials”4 have appeared in mainstream media publications and on various blog posts. Often these articles contain unrelated file photos with radioactive themes that are apparently added to catch the eye of a potential reader and/or raise their level of concern.

Is there a serious threat or are these headlines over-hyped? Is there a real potential that ISIL could produce a “dirty bomb” and inflict radiation casualties and property damage in the United States, Europe, or any other state that might oppose ISIL as part of the recently formed U.S.-led coalition? What are the confirmed facts? What are reasonable assumptions about the situation in ISIL-controlled areas and what is a realistic assessment of the level of possible threat?

As anyone who has followed recent news reports about the rapid disintegration of the Iraqi Army in Western Iraq can appreciate, ISIL is now in control of sizable portions of Iraq and Syria. These ISIL-controlled areas include oilfields, hospitals, universities, and industrial facilities, which may be locations where various types of radioactive materials have been used, or are being used.

In July 2014, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) released a statement indicating that Iraq had notified the United Nations “that nuclear material has been seized from Mosul University.”5 The IAEA’s press release indicated that they believed that the material involved was “low-grade and would not present a significant safety, security or nuclear proliferation risk.” However, despite assessing the risk posed by the material as being low, the IAEA stated that “any loss of regulatory control over nuclear and other radioactive materials is a cause for concern.”6 The IAEA’s statement caused an initial flurry of press reports shortly after its release in July.

A second round of reports on the threat of ISIL using nuclear or radioactive material started in early September, triggered by the announcement of a U.S.-Iraq agreement on a Joint Action Plan to combat nuclear and radioactive smuggling.7 According to a Department of State (DOS) press release on the Joint Action Plan, the U.S. will provide Iraq with training and equipment via the Department of Energy’s Global Threat Reduction Initiative (GTRI) that will enhance Iraq’s capability to “locate, identify, characterize, and recover orphaned or disused radioactive sources in Iraq thereby reducing the risk of terrorists acquiring these dangerous materials.”8 Although State’s press release is not alarmist, it does state that the U.S. and Iraq share a conviction that nuclear smuggling and radiological terrorism are “critical and ongoing” threats and that the issues must be urgently addressed.9

While September’s headlines extrapolating State’s press release to U. S. “fears” might be characterized by some as over-hyping the issue, it is clear that both statements from the IAEA and the State Department have indicated that the situation in Iraq may be cause for concern. Did IAEA and DOS go too far in their statements? In their defense, it would be highly irresponsible to indicate that any situation where nuclear or other radioactive material might be in the hands of individuals or groups with a potential for criminal use is not a subject for concern. However, we need to go beyond such statements and determine what risks are posed by the materials that have been reported as possibly being under ISIL control in order to determine how concerned the public should be.

According to the IAEA’s press release, the material reported by Iraq was described as “nuclear material,” but this description does not imply that it is suitable for a yield producing nuclear weapon. In fact, the IAEA’s description of the material as “low-grade” indicates that the IAEA believes that this material is not enriched to the point where it could be used to produce a nuclear explosion. Furthermore, although the agency has not provided a technical description of the nuclear material, it is highly unlikely that this is anything other than low enriched uranium or perhaps even natural or depleted uranium, all of which would fit under the IAEA’s definition of “nuclear material.” If the material is not useful in a yield producing device, is it a radioactive hazard? All forms of uranium are slightly radioactive, but the level of radioactivity is so low that these materials would not pose a serious radioactive threat, (either to persons or property), if they were used in a Radioactive Dispersion Devices (RDDs). Even a “Dirty Bomb,” which is an RDD dispersed by explosives, would not be of significant concern.

Other than the nuclear material mentioned in the report to the United Nations, there are no known open source reports of loss of control of other radioactive materials. However, a lack of specific reporting does not mean that control is still established over any materials that are in ISIL -controlled areas. It would be prudent to assume that all materials in these areas are out of control and assessable to ISIL should it choose to use whatever radioactive materials can be found for criminal purposes. How do we know what materials may be at risk? Hopefully the Iraq Radioactive Sources Regulatory Authority (IRSRA) has/had a radioactive source registry in Iraq. If so, authorities should know in some detail what materials are in ISIL-controlled territories. The Syrian regulatory authority may have at one time had a similar registry that would indicate what may now be out of control in the ISIL-controlled areas of Syria. Unfortunately, there is no open source reporting of any of these materials so we are left to speculate as to what might be involved and what the consequences may be should those materials attempt to be used criminally.

It is doubtful that any radioactive materials in ISIL controlled areas are very large sources. The materials that would pose the greatest risk would probably be for medical uses. These sources are found in hospitals or clinics for cancer treatment or blood irradiation and typically use cesium 137 or cobalt 60, both of which are relatively long-lived (approximately 30 and five years respectively) and produce energetic gamma rays. It is also possible that radiography cameras containing iridium 192 and well logging sources that typically use cesium 137 and an americium beryllium neutron source may also be in the ISIL-controlled areas. Any technical expert would opine that these sources are capable of causing death and that dispersal of these materials would create a cleanup problem and possibly significant economic loss. However, experts almost uniformly agree that such materials do not constitute Weapons of Mass Destruction, but are potential sources for disruption and for causing public fear and panic. Furthermore the scenarios that pose the greatest risk for the United States or Europe from these materials are difficult for ISIL to organize and carry out.

If ISIL were to attempt to use such materials in an RDD, they would need to transport the materials to the target area (for example in the United States or Europe), in a manner that is undetectable and relatively safe for the person(s) transporting or accompanying a movement of the material. Although in some portions of a shipment cycle there would be no need to accompany the materials, at some point people would need to handle the materials. Even if the handlers had suicidal intent, shielding would be required in order to prevent detection of the energetic radiations that would be present for even a weak RDD. Shielding required for really dangerous amounts of these materials is typically both heavy and bulky and therefore the shielded materials cannot be easily transported simply by a person carrying them on their person or in their luggage. They would probably need to be shipped as cargo in or on some sort of vehicle (car, bus, train, ship, or plane). Surface methods of transport might reach Europe, but carriage by ship or air is necessary to reach the United States.10 Aircraft structures do not provide any inherent shielding and so the most logical (albeit not only), method of transportation to the United States or Europe would be by ship, probably from a Syrian port. Even though ISIL controls a significant land area, the logistics of shipping an item that is highly radioactive to the United States or Europe would be a complex process and need to defeat significant post-9/11 detection systems. These systems, although perhaps not 100 percent effective for all types and amounts of radioactive material, typically are thought to be very effective in the detection of high-level sources.

Any materials from ISIL-controlled areas could only be used in the United States or Europe with great difficulty. It is highly probable that the current radiation detection systems would be effective in deterring any such attempted use even if there were no human intelligence that would compromise such an effort. Even if ISIL could use materials for an RDD attack, the actual damage potential of these types of attacks is relatively low when they are compared to far simpler and often used terrorist tactics such as suicide vests and truck and car bombs. The casualties that would result from any theoretical RDD would be probably less than those resulting from a serious traffic accident and that is probably on the high end of casualty estimates. Indeed, many experts feel that most, if not all, of the serious injuries from a “dirty bomb” would result from the explosive effects of the bomb, not from the dispersal of radioactive materials. The major consequence of even a fairly effective dispersal of material would be a cleanup problem with the economic impact determined by the area contaminated and the level to which the area would need to be cleaned.

Efforts by the United States to work with the ongoing government in Iraq in improving detection and control of nuclear and other radioactive materials appear to be a prudent effort to minimize any threat from these materials in the ISIL-controlled areas. To date, ISIL has not made any threats to use radioactive material. That does not mean that ISIL is unaware of the potential, and we should be prepared for ISIL to use their surprisingly effective social media connections to attempt to make any future radioactive threat seem apocalyptic. Rational discussion of potential consequences and responses to an attack scenario should occur before an actual ISIL threat, rather than having the discussion in the 24/7 news frenzy that could invariably follow an ISIL threat.

Dr. George Moore is currently a Scientist in Residence and Adjunct Faculty Member at the Monterey Institute of International Studies’ James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, a Graduate School of Middlebury College, in Monterey, California. He teaches courses and workshops in nuclear trafficking, nuclear forensics, cyber security, drones and surveillance, and various other legal and technical topics. He also manages an International Safeguards Course sponsored by the National Nuclear Security Agency in cooperation with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

From 2007-2012 Dr. Moore was a Senior Analyst in the IAEA’s Office of Nuclear Security where he was involved with, among other issues, the IAEA’s Illicit Trafficking Database System and the development of the Fundamentals of Nuclear Security publication, the top-level document in the Nuclear Security Series. Dr. Moore has over 40 years of computer programming experience in various programming languages and has managed large database and document systems. He completed IAEA training in cyber security at Brandenburg University and is the first instructor to use the IAEA’s new publication NS22 Cyber Security for Nuclear Security Professional as the basis for a course.

Dr. Moore is a former staff member of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory where he had various assignments in areas relating to nuclear physics, nuclear effects, radiation detection and measurement, nuclear threat analysis, and emergency field operations. He is also a former licensed research reactor operator (TRIGA).

Feasibility of a Low-Yield Gun-Type Terrorist Fission Bomb

Introduction

Edward Friedman and Roger Lewis’s essay “A Scenario for Jihadist Nuclear Revenge,” published in the Spring 2014 edition of the Public Interest Report, is a sobering reminder of both the possibility of a terrorist nuclear attack based on stolen highly-enriched uranium and the depressing level of public ignorance of such threats. Articles exploring the issue of terrorists or rogue sub-national actors acquiring and using a nuclear weapon or perpetrating some other type of nuclear-themed attack have a long history and have addressed a number of scenarios, including a full-scale program to produce a weapon from scratch, use of stolen reactor-grade plutonium, an attack with a radiological dispersal device, and the vulnerability of research reactors.[5]Equally vigorous are discussions of countermeasures such as detecting warheads and searching for neutron activity due to fissile materials hidden inside cargo containers. An excellent summary analysis of the prospects for a terrorist-built nuclear weapon was prepared almost three decades ago by Carson Mark, Theodore Taylor, Eugene Eyster, William Maraman and Jacob Wechsler, who laid out a daunting list of materials, equipment, expertise and material-processing operations that would be required to fabricate what the authors describe as a “crude” nuclear weapon – a gun or implosion-type device similar to Little Boy or Fat Man. The authors estimated that such a weapon might weigh on the order of a ton or more and have a yield of some 10 kilotons. Perpetrators would face a serious menu of radiological and toxicological hazards involved in processing fissile materials. For example, both uranium (U) and plutonium (Pu) are chemically toxic; also, U can ignite spontaneously in air and Pu tends to accumulate in bones and kidneys. Of course, longer-term health effects might be of little concern to a group of suicidal terrorists.

While the difficulties of such a project might provide reassurance that such an effort has a low probability of being brought to fruition, we might ask if nuclear-armed terrorists along the lines envisioned by Friedman and Lewis would be willing to settle for a relatively low-yield device to achieve their ends. A bomb with a yield of 10 percent of that of Little Boy would still create a devastating blast, leave behind a radiological mess, and generate no small amount of social and economic upheaval. Such a yield would be small change to professional weapons engineers, but the distinction between one kiloton and 15 kilotons might largely be lost on political figures and the public in the aftermath of such an event. Timothy McVeigh’s 1995 Oklahoma City truck bomb used about 2.5 tons of explosive; a one-kiloton detonation would represent some 400 such explosions and make a very powerful statement.

Motivated by Friedman and Lewis’s scenario, I consider the feasibility of an extremely crude gun-type U-235 device configured to be transported in a pickup truck or similar light vehicle. My concern is not with the difficulties perpetrators might face in acquiring fissile material and clandestinely preparing their device, but rather with the results they might achieve if they can do so. The results reported here are based on the basic physics of fission weapons as laid out in a series of pedagogical papers that I have published elsewhere. The essential configuration and expected yield of the device proposed is described in the following section; technical details of the physics computations are gathered in the Appendix.

A Crude Gun-Type Fission Bomb

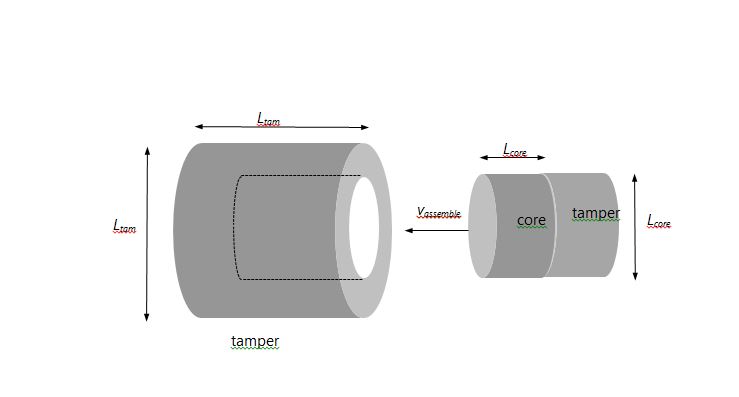

The bare critical mass of pure U-235 is about 46 kg; this can be significantly lowered by provision of a surrounding tamper. I frame the design of a putative terrorist bomb by assuming that perpetrators have available 40 kg of pure U-235 to be packaged into a device with a length on the order of 2-3 meters and a total estimated weight of 450 kg (1000 pounds), of which 200 kg is budgeted for tamper material. The 40-kg core is subcritical, and the uranium need not be divided up into target and projectile pieces as in the Friedman-Lewis scenario, although the design suggested here could easily be modified to accommodate such an arrangement.

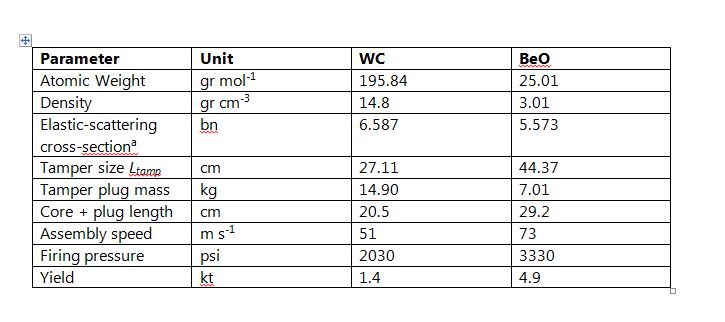

As sketched below, I assume that the uranium is formed into a cylindrical slug of diameter and length Lcore. The core and a plug of tamper material are to be propelled down an artillery tube into a cylindrical tamper case such that the core will be located in the middle of the case once assembly is complete; the assembled core-plus-tamper is assumed to be of diameter and length Ltamp. The choice of tamper material is a crucial consideration; it can seriously affect the predicted yield. In the case of Little Boy, readily-available tungsten-carbide (WC) was employed. Beryllium oxide (BeO) has more desirable neutron-reflective properties, but is expensive and its dust is carcinogenic; more importantly, an effort to acquire hundreds of kilograms of it is likely to bring unwanted attention. I report results for both WC and BeO tampers.

Adopted parameters and calculated results are gathered in Table 1. Technical details are described in the Appendix; the last line of the table gives estimated yields in kilotons. To estimate these yields I used a FORTRAN version of an algorithm which I developed to simulate the detonation of a spherical core-plus-tamper assembly (see the numerical simulation paper cited in footnote 10). A spherical assembly will no doubt give somewhat different results in detail from the cylindrical geometry envisioned here, but as the program returns an estimated yield for a simulation of Little Boy in good accord with the estimated actual yield of that device, we can have some confidence that the results given here should be sensible.

For both configurations in Table 1, the sum of the core, tamper, and artillery-tube masses is about 315 kg (700 lb). With allowance for a breech to close off the rear end of the tube, neutron initiators, detonator electronics, propelling chemical explosives and an enclosing case (which need not be robust if the weapon is not to be lifted), it appears entirely feasible to assemble the entire device with a total weight on the order of 1,000 pounds. Beryllium oxide is clearly preferable as the tamper material, but even with a tungsten-carbide tamper the yield is about 10 percent of that of Little Boy. In open terrain a 2-kiloton ground-burst creates a 5-psi overpressure out to a radius of about one-third of a mile; such an overpressure is quite sufficient to destroy wood-frame houses.

In summary, the sort of vehicle-deliverable makeshift gun-type fission weapon envisioned by Friedman and Lewis appears to be a very plausible prospect; yields on the order of a few kilotons are not out of reach. In view of the fact that all of the calculations in this paper are based on open information, there are sure to be nuances in the physics and particularly the engineering involved that would make realization of such a device more complex than is implied here. But this exercise nevertheless serves as a cautionary tale to emphasize the need for all nuclear powers to rigorously secure and guard their stockpiles of fissile material.

Technical Appendix

Refer to Table 1 and the figure above. A 40-kg U-235 core of normal density (18.71 gr cm-3) will have Lcore = 13.96 cm. The first three lines of Table 1 give adopted atomic weights, densities, and elastic-scattering cross sections for each tamper material. The next two lines give the tamper size and plug mass, and the sixth line the total length of the core-plus-plug bullet.

To estimate the yield of the proposed device I assumed for sake of simplicity that the core is spherical (radius ~ 8 cm) and surrounded by a snugly-fitting 200-kg tamper. Each fission was assumed to liberate 180 MeV of energy and secondary neutrons of average kinetic energy 2 MeV. The number of initiator neutrons was assumed to be 100, radiation pressure was assumed to dominate over gas pressure in the exploding core, and the average number of neutrons per fission was taken to be n = 2.637.

Lines 7 and 8 in Table 1 refer to two important considerations in bomb design: the speed with which the core seats into the tamper and the propellant pressure required to achieve this speed. The core material will inevitably contain some U-238, which, because of its high spontaneous fission rate (~ 7 per kg per second), means that there will be some probability for premature initiation of the chain reaction while the core and tamper are being assembled. (There is no danger of pre-detonation before seating as 40 kg is less than the “bare” critical mass of U-235. The danger during seating arises from the fact that the tamper lowers the critical mass.) The key to minimizing this probability lies in maximizing the assembly speed. If our 40-kg core contains 10 percent by mass U-238, the pre-detonation probability can be kept to under 10 percent if the time during which the core is in a supercritical state during assembly is held to no more than four milliseconds (see the pre-detonation paper cited in footnote 10). The seventh line of Table 1 shows corresponding assembly speeds based on this time constraint and the core-plug lengths in the preceding line. These speed demands are very gentle in comparison to the assembly speed employed in Little Boy, which was about 300 m s-1.

To achieve the assembly speed I assume that (as in Little Boy), the core-plus-plug is propelled along a tube by detonation of a conventional explosive adjacent to the rear end of the tamper plug in the tail of the weapon. To estimate the maximum pressure required, I assumed that the propulsion is provided by the adiabatic expansion (in which no heat is gained or lost) of the detonated explosive. Adiabatic expansion of gas to propel a projectile confined to a tube has been extensively studied; an expression appearing in Rohrbach et. al. can be used to estimate the initial pressure required given the cross-sectional area of the tube, the mass of the projectile, the length of the tube, a value for the adiabatic exponent _gand the assembly speed to be achieved. This pressure also depends on the initial volume of the detonated explosive; for this I adopted a value of 0.004 m3, about the volume of the core-plug assemblies. The eighth line of Table 1 shows the estimated necessary initial pressures (neglecting any friction between the projectile and the tube) for a travel length of 1.5 meters for g = 1.4; this value of g is characteristic of a diatomic gas. These pressures are very modest, and would set no undue demands on the tube material. Stainless steel, for example, has an ultimate strength of ~ 500 MPa (~75,000 psi); such a tube of inner diameter 7 cm, thickness 1 cm, and length 2 meters would have a mass of about 75 kg. This would bring the sum of the core, tamper, and tube masses to ~ 315 kg (700 lb).

A final technical consideration is the so-called fizzle yield that this makeshift weapon might achieve, that is, its yield if the chain reaction should begin at the moment when the core achieves first criticality. As described by von Hippel and Lyman in Mark (footnote 3), the fizzle yield as a fraction of the nominal design yield can be estimated from the expression Yfizzle/Ynominal ~ (2t F/a tO)3/2, where t is the average time that a neutron will travel before causing a fission, F is the natural logarithm of the number of fissions that have occurred when the nuclear chain reaction proper can be considered to have begun, a is a parameter in the exponential growth rate of the reaction set by the masses and sizes of the core and tamper, and tO is the time required to complete the core assembly. As described by Mark, t ~ 10-8 sec and F ~ 45. For the design posited here, a~ 0.32 for the WC tamper and ~ 0.47 for the BeO tamper; see Reed (2009) in footnote 10 or Sect. 2.3 of the last reference in footnote 10 regarding the computation of a. Taking tO = 0.004 sec gives Yfizzle/Ynominal ~ 1.9 x 10-5 for the WC tamper and 1.0 x 10-5 for the BeO tamper. With nominal yields of 1.4 and 4.9 kt, the estimated fizzle yields are only ~ 27 and 50 kilograms equivalent. While the perpetrators of such a device might be willing risk such a low yield in view of the low pre-detonation probability involved, they would be well-advised to increase the assembly speed as much as possible.

*Fission-spectrum averaged elastic-scattering cross-sections adopted from Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute Table of Nuclides, http://atom.kaeri.re.kr

Edward A. Friedman & Roger K. Lewis, “A Scenario for Jihadist Nuclear Revenge,” Federation of American Scientists Public Interest Report 67 (2) (Spring 2014).

Robert Harney, Gerald Brown, Matthew Carlyle, Eric Skroch & Kevin Wood, “Anatomy of a Project to Produce a First Nuclear Weapon,” Science and Global Security 14 (2006): 2-3, 163-182.

J. Carson Mark, “Explosive Properties of Reactor-Grade Plutonium,” Science and Global Security 4 (1993): 1, 111-128.

J. Magill, D. Hamilton, K. Lützenkirchen, M. Tufan, G. Tamborini, W. Wagner, V. Berthou & A. von Zweidorf, “Consequences of a Radiological Dispersal Event with Nuclear and Radioactive Sources,” Science and Global Security 15 (2007): 2, 107-132.

Steve Fetter, Valery A. Frolov, Marvin Miller, Robert Mozley, Oleg F. Prilutsky, Stanislav N. Rodinov & Roald Z. Sagdeev, “Detecting nuclear warheads,” Science and Global Security 1 (1990): 3-4, 225-253.

J. I. Katz, “Detection of Neutron Sources in Cargo Containers,” Science and Global Security 14 (2006): 2-3, 145-149.

J. Carson Mark, Theodore Taylor, Eugene Eyster, William Maraman & Jacob Wechsler, “Can Terrorists Build Nuclear Weapons?” Paper Prepared for the International Task Force on the Prevention of Nuclear Terrorism. Nuclear Control Institute, Washington, DC (1986). Available at http://www.nci.org/k-m/makeab.htm

Cristoph Wirz & Emmanuel Egger, “Use of nuclear and radiological weapons by terrorists?” International Review of the Red Cross 87 (2005): 859, 497-510.

B. Cameron Reed, “Arthur Compton’s 1941 Report on explosive fission of U-235: A look at the physics.” American Journal of Physics 75 (2007): 12, 1065-1072; “A brief primer on tamped fission-bomb cores.” American Journal of Physics 77 (2009): 8, 730-733; “Predetonation probability of a fission-bomb core.” American Journal of Physics 78 (2010): 8, 804-808; “Student-level numerical simulation of conditions inside an exploding fission-bomb core.” Natural Science 2 (2010): 3, 139-144; “Fission fizzles: Estimating the yield of a predetonated nuclear weapon.” American Journal of Physics, 79 (2011): 7, 769-773; The Physics of the Manhattan Project (Heidelberg, Springer-Verlag, 2010).

Z. J. Rohrbach, T. R. Buresh & M. J. Madsen, “Modeling the exit velocity of a compressed air cannon,” American Journal of Physics 80 (2012): 1, 24-26.

Cameron Reed is the Charles A. Dana Professor of Physics at Alma College, where he teaches courses ranging from first-year algebra-based mechanics to senior-level quantum mechanics. He received his Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Waterloo (Canada). His research has included both optical photometry of intrinsically bright stars in our Milky Way galaxy, and the history of the Manhattan Project. His book The History and Science of the Manhattan Project was recently published by Springer.

Domestic Terrorism Again a Priority at DOJ, and More from CRS

The threat of domestic terrorism is receiving greater attention at the Department of Justice with the reestablishment in June of the Domestic Terrorism Executive Committee, the Congressional Research Service noted last week.

“The reestablishment suggests that officials are raising the profile of domestic terrorism as an issue within DOJ after more than a decade of heightened focus on both foreign terrorist organizations and homegrown individuals inspired by violent jihadist groups based abroad,” CRS wrote. See Domestic Terrorism Appears to Be Reemerging as a Priority at the Department of Justice, CRS Insights, August 15, 2014.

Other new or updated CRS products include the following.

Latin America: Terrorism Issues, updated August 15, 2014:

Cuba: U.S. Restrictions on Travel and Remittances, updated August 19, 2014:

Preparing for Disasters: FEMA’s New National Preparedness Report Released, CRS Insights, August 12, 2014

Export-Import Bank Reauthorization Debate, CRS Insights, August 18, 2014:

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): Appropriations for FY2014 in P.L. 113-76, August 15, 2014:

Senate Unanimous Consent Agreements: Potential Effects on the Amendment Process, updated August 15, 2014

Synthetic Drugs: Overview and Issues for Congress, updated August 15, 2014

Hezbollah and the Use of Drones as a Weapon of Terrorism

The international terrorist group Hezbollah, driven by resistance to Israel, now regularly sends low flying drones into Israeli airspace. These drones are launched and remotely manned from the Hezbollah stronghold in Lebanon and presumably supplied by its patron and strategic partner, Iran. On the U.S. State Department’s list of terrorist organizations since 1995, Hezbollah has secured its presence in Lebanon through various phases. It established a strong social services network, and in 2008 it became the dominant political party in the Lebanese government and supported the Assad regime in the Syrian Civil War.

Hezbollah’s drone flights into Israeli airspace

Hezbollah’s first flight of an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or drone, into Israeli airspace for reconnaissance purposes occurred in November 2004, catching Israeli intelligence off guard. A Mirsad-1 drone (an updated version of the early Iranian Mohajer drone used for reconnaissance of Iraqi troops during the 1980s Iran-Iraq War), flew south from Lebanon into Israel, hovered over the Western Galilee town of Nahariya for about 20 minutes and then returned to Lebanon before the Israeli air force could intercept it.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah boasted that the Mirsad could reach “anywhere, deep, deep” into Israel with 40 to 50 kilograms of explosives. One report at the time was that Iran had supplied Hezbollah with eight such drones, and over two years some 30 Lebanese operatives had undergone training at Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps bases near Isfahan to fly missions similar to the Mirsad aircraft.

The second drone flight into Israel was a short 18-mile incursion in April 2005 (again by a Mirsad-1 drone), that eluded Israeli radar and returned to Lebanon before Israeli fighter planes could be scrambled to intercept it. A third drone mission in August 2006 during the Lebanon War was intended for attack; Hezbollah launched three small Ababil drones into Israel each carrying a 40-50 kilogram explosive warhead intended for strategic targets. This time Israeli F-16s shot them down, one on the outskirts of Haifa, another in Western Galilee, and the third in Lebanon near Tyre.

Abruptly, the incursion of Hezbollah drones into Israeli airspace stopped – only to be started up again after a six year hiatus. Presumably, drone launches by Hezbollah into Israel are planned and carried out to meet the political agenda of Iran, while shielding Iran’s involvement and allowing a measure of deniability. The involvement of Shiite Hezbollah with Iran dates back to financial support and training from the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps and the suicide attacks in Beirut in October 1983 on the U.S. embassy and the Marine Corps barracks attacks. This was followed by Iranian sponsorship of Hezbollah attacks on the Israeli embassy and the Jewish Community Center in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1992 and 1994, and the Khobar Towers bombing in Saudi Arabia in 1996.

The drones sent out from Lebanon were small objects moving at slow speed and low elevation and as such they were difficult to detect by radar. The Mirsad-1 and the Ababil were each only about 9.5 feet in length. The low speed (120 miles per hour for the Mirsad-1 and 180 miles per hour for the Ababil) minimized the Doppler shift in the reflected radar beam and made detection difficult. The low ceiling (6,500 feet for the Mirsad-1 and 9,800 feet for the Ababil) would limit detection as it is obscured by ground clutter, glare, and other environmental conditions. In the past it has been reported that drones could penetrate Israel’s radar and air defense systems, even the Iron Dome. But ongoing upgrades in detection capability suggest progress has been made in improving sensitivity and limiting detection failure to areas lacking air defenses, or suppressed defenses, or when the drones are indeed very small.

A daring mission to the nuclear complex at Dimona

The next appearance of a Hezbollah drone on October 6, 2012, was a spectacular foray that took Israel by surprise. An Iranian drone called “Ayub” flew south from Lebanon over the Mediterranean and into Israel via the Gaza Strip, moving westward about 35 miles into the Negev and penetrating to a point near the town of Dimona, the site of Israel’s nuclear weapons complex. There it was shot down over a forest by Israeli aircraft. Examining the wreckage, Israeli military said that it was possible the drone could have transmitted imagery of the nuclear research center.

Observers immediately interpreted this incursion as a message from Iran that Israel’s nuclear facilities were vulnerable to attack should Israel attempt any military action against Iran’s nuclear facilities. Apparently the propaganda victory was significant enough for Iran to admit spying on Israel several weeks later: an influential member of the Iranian Parliament announced that Iran had pictures of sensitive Israeli facilities transmitted by the drone.

In a more recent flight in April 2013, an unmanned aircraft attributed to Hezbollah reached the coast near the city of Haifa, where an Israeli warplane brought it down, demonstrating that these drones are still vulnerable to counter-attack.

Each drone flight into Israel is potentially a significant propaganda victory for Hezbollah. As Matthew Levitt of the Washington Institute has noted, “They love being able to say, ‘Israel is infiltrating our airspace, so we’ll infiltrate theirs, drone for drone.’”