Why Credit Access Makes or Breaks Clean Tech Adoption and What Policy Makers Can Do About It

For clean energy to reach everyone, government can’t just regulate behavior. It has to actively shape credit markets in partnership with the private sector.

Implications for democratic governance:

- Financing programs need governance that is visibly fair, transparent, and accountable to enable trust–without that, low trust drags down their efficacy.

- Build broad constituencies to set and drive the agenda.

- Treat local lenders and communities as active implementers, not passive beneficiaries.

Capacity needs:

- Talent, playbooks, and governance structures to run policy-enabled finance (credit, guarantees, revolving funds) with speed and integrity.

- Faster contracting, simpler reporting, and fewer transaction frictions.

- Clear guidance on identifying and resolving tradeoffs, instead of allowing decisions to bog down in case-by-case analysis paralysis.

- Staff who can translate between agencies, investors, and communities.

- Connective tissue to and between states to replicate smart practices and share toolkits for financing mechanisms that move beyond one-time infusions of cash.

- Quasi-public structures that give government agility without sacrificing public interest and accountability.

Access to affordable credit is a necessary condition for an equitable energy transition and an inclusive economy. Markets naturally concentrate capital where risk is low and returns are predictable, leaving low-income communities, rural areas, and smaller projects behind. Well-designed federal policy can change that dynamic by shaping markets—reducing risk, creating incentives, and unlocking private capital so clean technologies reach everyone, everywhere. This paper explores how policy-enabled finance must be part of the toolkit if we are going to drive widespread adoption of clean technologies, and can be summarized as follows:

- Problem: Clean technologies require upfront capital; tax incentives alone are insufficient for small, distributed projects and underresourced borrowers. Without targeted credit solutions, the energy transition will deepen existing economic and environmental inequities.

- Opportunity: Policy‑enabled financial services—direct investments, tax incentives, and loan guarantees—have a proven track record of expanding access to credit and driving inclusive economic growth. The climate policy playbook should be expanded to incorporate lessons from other sectors and programs that have incorporated these interventions.

- Case study: The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) was designed to augment grants and tax incentives contained in the Inflation Reduction Act by seeding revolving capital, leveraging national financing hubs, and mobilizing local lenders to scale clean investments. This program was stopped in its tracks early in the Trump administration, but lessons from its design and early implementation should be leveraged by local, state, and future federal programs.

The critical role of policy-enabled finance to drive widespread economic opportunity

Access to affordable credit is not just a financial tool—it is a cornerstone of economic opportunity. It enables families to buy homes, entrepreneurs to launch businesses, and communities to invest in technologies that reduce costs and improve quality of life. Yet, across the United States, access to credit remains deeply uneven. Nearly one in five Americans and entire regions – particularly rural and Tribal communities – are excluded from the financial mainstream, limiting their ability to thrive.

Private-sector financial institutions—banks, private equity firms, and other lenders—are designed to maximize profit. They concentrate on markets where risk is predictable, transaction costs are low, and deals are easy to close. This business model leaves behind borrowers and communities that fall outside these parameters. Without intervention, capital flows toward the familiar and away from the places that need it most.

Public policy can change this dynamic. By creating incentives or mitigating risk, policy can make lending to or investing in underserved markets viable and attractive. These interventions are not distortions — they are strategic investments that unlock economic potential where the market alone cannot, generating economic value and vitality for the direct recipients while yielding positive externalities and public benefit for local communities. And, importantly, these policy interventions act as a critical complement to regulation. Increasing access to credit is often the carrot that can be paired with, or precede, a regulatory stick so that people are not only led to a particular economic intervention, but they are also incentivized and enabled.

For decades, policy-enabled finance has delivered measurable impact through multiple programs and agencies designed to support local financial institutions – regulated and unregulated, depository and non-depository – that are built to drive economic mobility and local growth. These policies and programs have taken multiple forms, but can generally be put in three categories:

- Direct Investments: Programs like the CDFI Fund Financial Assistance awards that provide enterprise grants to Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs) to support balance sheet strength and increased lending and the Emergency Capital Investment Program (ECIP) that made equity investments into community development credit unions and banks.

- Tax Credits and Incentives: The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC), Opportunity Zones, and renewable energy credits like the Investment Tax Credit and Production Tax Credit have spurred billions in private investment for housing, community development, and clean energy.

- Loan Guarantees: Small Business Administration, U.S. Department of Agriculture, and Department of Energy guarantee programs, among others, reduce risk for the lender, enabling small businesses, rural communities, and earlier stage companies to access credit otherwise unavailable at transparent and affordable rates from participating financial institutions.

These tools enjoy broad recognition and bipartisan support because they work. They increase access, availability, and affordability of credit—fueling job creation, housing stability, and economic resilience. Policy-enabled finance is not charity; it is a proven strategy for broad and inclusive economic growth and a key tool for the policy-maker toolkit to support capital investment, project development, and adoption of beneficial technologies in a market-driven context that can increase the effectiveness of a regulatory agenda.

Most importantly, policy-enabled finance has led to major improvements in wealth-building and quality of life for millions of Americans. The 30-year mortgage was created by the Federal Housing Administration in the 1930s as a response to the Great Depression. Before this intervention, only the very wealthy could afford to buy a home given the high downpayment requirements and short-term loans. Since this policy change, thousands of financial institutions have offered long-term mortgages to millions of Americans who have bought homes that provide safety and security for their families, strong communities, and an opportunity to build wealth through appreciating assets. Broad home ownership is a public good, but until the government created the right policy and regulatory framework for the markets, it was out of reach for the majority of Americans.

Similarly, the Small Business Administration’s loan guarantee programs started in the 1950s supported financial institutions, including banks and non-bank lenders, in extending credit to small businesses that would otherwise be difficult to serve with affordable credit. These programs have collectively helped millions of small businesses access the credit they need to grow their businesses, create wealth for themselves and their families, provide critical goods and services in their communities, and create a diverse and vibrant local tax base.

The financial markets, without these types of interventions, are not structured to prioritize access and affordability. Well-designed policy and complementary regulatory interventions have been proven to drive different behaviors in the capital markets that yield real benefits for American families and businesses.

The role of access to credit in driving an equitable energy transition

The public and private sectors have spent decades and billions of dollars investing in the development of clean technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions, create economic benefits, and deliver a better customer experience. Now that these technologies exist, the challenge is to deploy them for everyone, everywhere.

The barrier to widespread deployment is that most clean technologies require an upfront investment to yield long-term benefits and savings (i.e., an initial capital expense to reduce ongoing operational expenses) – technologies like solar and battery storage, electric vehicles, electric HVAC and appliances, etc. – which means that people and companies with cash or access to credit are adopting these better technologies while those without access to cash or credit are being left behind. This is yielding an even greater divide – creating economic savings, health benefits, and better technologies for those who can afford them, while leaving dirty, volatile, and increasingly expensive energy sources for the lowest-income communities.

Many of the federal policy interventions to support deployment of these new technologies to date have been through tax credits. These policies have been very popular, but are not often widely adopted, particularly in rural and lower-income communities, because, (a) they are complex, (b) they often require working with individuals or businesses with large tax liabilities, and (c) they typically come with high transaction costs, making smaller, more distributed projects harder to make work. The energy transition is a huge wave of change, but it is made up of many small component parts – individual buildings, machines, vehicles, grids – so if our policies fail to enable small projects to get done, we will fail to transition quickly and equitably.

To deploy everywhere, households and businesses need credit to offset capital expenses. To expand access to credit, we need supportive clean energy policies that work within and alongside local financial services ecosystems – just like we’ve seen with housing and small businesses.

Regulation is insufficient to drive widespread adoption

Pursuing a carbon-free economy is a massive undertaking and, understandably, much of the state and federal government’s toolkit has focused on regulation of people and businesses to drive behavior change – policies like fuel economy standards, pollution restrictions, renewable energy standards, and electrification mandates. This is an important piece of the puzzle – but insufficient to drive broad (and willing) adoption.

Take, for example, the goal of electrifying heavy-duty trucks in and around port communities. States like California have attempted to set a date at which all new trucks on the registry must be zero-emissions vehicles. Predictably, this mandate was met with a lot of pushback from truck drivers, small operators, and industry associations who struggled to see a path to complying with this regulation without a major increase in cost.

It wasn’t until the regulation was paired with direct incentives for truck purchases and an attractive and feasible financing package for vehicle acquisition and charging infrastructure that the industry actors started to come around. This has helped change behavior of both buyers and incumbent sellers in the market.

Policy-enabled finance creates tools – often used in conjunction with other policy mechanisms – that can more effectively meet people where they are with affordable, appropriate, and tailored solutions and can help demonstrate a feasible path to adoption that can help buyers and sellers in these markets adapt accordingly.

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund as an innovative policy-enabled finance program

The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) is more than an emissions initiative—it is a strategic investment in economic equity and market innovation that took lessons in program design from many sectors and programs of the past. Designed with three core objectives, the program aims to:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions at scale

- Deliver direct benefits to communities, particularly those that have been historically underserved by the financial markets

- Transform financial markets to accelerate clean energy adoption and resilience

GGRF programs, including the National Clean Investment Fund, the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator, and Solar for All, were built to complement other Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) programs by occupying a critical middle ground between grant programs and tax credits. Grant programs provide direct, one-time support for projects and programs that are not financeable (i.e., not generating revenue). Tax credits are put into the market to incentivize private investment for anyone interested in taking advantage but are not typically targeted to any specific project or population.

GGRF bridges these approaches. It channels capital into markets where funding does not naturally flow in the form of loans and investments, ensuring that clean energy and climate solutions reach every community—but does so in a way that often extends the benefits of the tax credits and incentive programs so that they reach a broader set of projects and communities where the incentive is insufficient to drive adoption. GGRF focuses on increasing access to credit and investment in places that traditional finance overlooks by reducing risk and creating scalable financing structures, empowering local lenders, community organizations, and national financing hubs to deploy resources where they are needed most. Also, because the program makes loans and investments, it recycles capital continuously – akin to a revolving loan fund – so that the work filling gaps in market adoption can continue for decades.

GGRF’s design was built on a strong foundation of successful direct investment programs for local lenders, such as CDFI Fund awards and USDA programs. What makes it unique is its scale—tens of billions of dollars—and its centralized approach, leveraging national financing hubs to drive systemic change with and through new and existing local financial capillaries (i.e., credit unions, community banks, green banks, and loan funds). This program was not built to drive incremental progress; it is a market-shaping intervention designed to accelerate the clean energy transition while promoting widespread economic growth.

Unfortunately, the program was stopped in its tracks when the Trump administration illegally froze funds already disbursed to awardees, leading to multiple lawsuits to restore funding. Without this disruption, awardees and their partners across the country would be driving direct economic benefits for families and communities across all 50 states. In the first six months of the program, awardees had pipelines of projects and investments that were projected to create over 49,000 jobs, drive $866 million in local economic benefits, save families and businesses $2.7 billion in energy costs, and leverage nearly $17 billion in private capital. The intention and mechanics of the program were working – and working fast – to deliver direct economic, health and environmental benefits for millions of Americans.

Moving at the speed of trust: Bringing the public and private sectors together for effective implementation

For a program like the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund to succeed, both the private and public sectors need clarity, confidence and accountability. But most importantly, they need a baseline of trust between the parties to support ongoing creative problem solving to implement a new, scaled program with exciting promise and a limited blueprint.

For the private sector, certainty is paramount. Investors and lenders (and importantly, their lawyers) require clear definitions, consistent requirements, and transparency about the availability of funds, requirements of use, and the ability to forward commit capital to projects and businesses. They need mechanisms to leverage public dollars with private capital and assurances that counterparties will be shielded from political, compliance, and policy risk. Flexibility is equally critical, allowing actors to adapt to rapid market shifts and technological innovations without being constrained by rigid program structures. Understanding these requirements – and the needs of the financial market actors involved – is outside the comfort zone of most government agencies and employees and requires significant experience and capacity building to strengthen this muscle. Nimble thinking is not often associated with government agencies, but in policy-driven financial services, it is paramount.

At the same time, the public sector has its own requirements which require patience and understanding from the private sector. Policymakers and the EPA, the implementing agency of the GGRF, must ensure that funds are used properly and that Congressional and public oversight is robust. This means designing programs that comply with all laws and regulations while advancing policy priorities. It requires mechanisms for accountability—certifications, reporting, and transparency in how funds flow – along with safeguards against undue influence from purely profit-motivated private actors. Balancing these needs is not optional when managing taxpayer funds; it is the foundation for building trust and ensuring that the program delivers on its promise of reducing emissions, benefiting communities, and transforming markets.

Implementation requires striking the balance between the needs of the private and public actors; this was difficult and time consuming for both the federal employees and for us as private recipients. There was pressure to deploy quickly to demonstrate impact and the value of the program, but it took a long time to get contracts signed and funds in the market because of the many requirements of the public and private parties involved. We speak different languages, are solving for different constraints, and work in drastically different environments – all which led to complexity and delays.

Internal EPA requirements and federal crosscutters (i.e., federal requirements from other related laws that applied to this program) increased time to market and transaction costs. Many of these requirements came with high-level policy objectives without the ability to get to a level of detail required for capital deployment.

For example, two of the major policy crosscutters were the Davis Bacon and Related Acts (DBRA) requirements around labor and workforce, and the Build America Buy America (BABA) requirements for equipment manufacturing and component parts. While the agency and private awardees were aligned at a high level on policy intention – good-paying jobs and domestically-manufactured goods – down streaming these requirements to borrowers and projects required significantly more detail and nuance than was available to the agency, adding weeks and months onto implementation and frustration among private counterparties.

Clear expectations up front on how to manage the trade-offs – policy priorities versus capital deployment – could have helped create a high-level framework for implementation, which was a one-by-one review of use cases to determine feasibility and applicability. This added complexity and friction to the process without driving outsized results.

More requirements and complexity led to slower, more costly deployment, which meant fewer communities would benefit from the program’s goals of cutting emissions, creating jobs, and cutting household and business costs.

Another key feature of the program for the National Clean Investment Fund and Clean Communities Investment Accelerator was the ability for the federal government to leverage a Financial Agent to administer the funds. This arrangement was developed between the EPA and Treasury, leveraging a long-standing practice of the Treasury Department of contracting with external banks to provide financial services that were hard for the government to provide directly. This was particularly important for the National Clean Investment Fund program because the disbursement of funds into awardee accounts enabled the awardees to meet a core statutory requirement to leverage funds with private capital. Without this function, the cash would not be available on the balance sheet of the awardees and would be difficult to leverage with private investment.

Lastly, the reporting requirements for the program were complex, making it hard to provide clarity on what data collection was required for early transactions. Again, both parties recognized the importance of transparent data collection and dissemination but implementing that intent in practice was time consuming. A simple, standardized framework to get started that could evolve over time would have helped reduce uncertainty and supported faster deployment.

Altogether, the cross-sector translation – finding common ground between two disparate worlds – added many months onto the process of getting the program to the market which, in the current political climate, was time not spent doing the important work to educate a broad set of stakeholders on the program’s promise, potential, and purpose. A lot of this complexity could have been reduced by developing a baseline of trust between the parties through the application and award process, complemented by a common goal to improve program implementation over time.

Strange bedfellows create weak alliances

In addition to the programmatic elements of translation, the actors involved in implementing direct investment strategies tend to be unknown entities to government agencies and Congress. Even though many of the implementing organizations – the “awardees” – have been around for decades doing similar work, there were weak ties with Congress, federal agencies, and other related stakeholders. Similarly, there was a lack of understanding of the role that nonprofit and community-based financial organizations play in addressing market gaps. This mutual lack of understanding and engagement leaves room for misunderstanding, distrust or generalizations that can hinder the ability to make collective progress.

Within the agency, this was a new program type for the EPA, so requirements and design process took many months before anything was shared publicly. The Notice of Funding Opportunity was released nearly a year after the legislation was signed.

The unique form and function of the program and limited direct engagement with lawmakers and other stakeholders about the program left a vacuum of information, which led to skepticism and confusion. Because the funds were provided to awardees as grants, many interpreted this as just another grant program – a large federal spending package that would lead to “handouts” – instead of what it was, the federal government seeding a sustainable fund with “equity” that would be lent out, returned, and reinvested in perpetuity. For example, here is the Wall Street Journal editorial page,and later, the EPA press release conflating investments with “handouts”:

“Imagine if Republicans gave the Trump Administration tens of billions of dollars to dole out to right-wing groups to sprinkle around to favored businesses. That’s what Democrats did in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The Trump team’s effort to break up this spending racket has led to a court brawl, which could be educational.”

The fact that this policy structure and the private sector entities charged with implementing it were relative strangers led to confusion and delay during a period that could have been spent on outreach, engagement, and education. Without that broad base of support, the program unnecessarily became a political punching bag.

To mitigate this risk going forward, there needs to be greater investment in relationship building, education, stakeholder engagement and capacity building within and among the implementing partners across all relevant government actors and their private sector counterparts, especially after award selections are made. This connective tissue would go a long way in creating a baseline of common understanding of the policy objectives, program design, and implementation partners involved so all parties are aligned on strategic intent and path forward.

Making policy-enabled finance programs work in the future

If we agree that policy-enabled finance is essential to drive the energy transition and deliver broad benefits, the next step is asking the right questions about how to design these interventions for success, drawing lessons from the GGRF and other related programs.

First, what mechanisms should we use, and what are the trade-offs for each? Federally supported direct investment programs, such as managed funds, can deploy capital quickly and target underserved markets, but they require strong governance, thoughtful program design, and radical transparency, otherwise they are susceptible to the “slush fund” narrative or similar risks (i.e. conflicts of interest and political favors).

Tax credits and incentives have proven effective in attracting private investment, yet they often favor actors with existing tax liability and can leave smaller players behind. Guarantees reduce risk for lenders and unlock private capital, but they demand careful structuring to avoid moral hazard and can struggle to reach communities that are truly under-resourced.

Despite the many pitfalls of direct investment programs, they address a challenge that has plagued many of the more distributed policies: centralization and market making. Often in an attempt to let a thousand flowers bloom, policymakers underestimate the need for centralized or regional infrastructure to help with asset aggregation, data collection, product standardization, and scaled capital access. This yields local infrastructure that is sub-scale, inefficient, and unable to access the capital markets for private leverage – too small to truly shape markets.

While the GGRF’s future is uncertain given pending litigation, its purpose and role as a set of centralized financial institutions within the broader community-based financial ecosystem is critical – and needs to be more broadly understood as policymakers set future priorities.

Second, should government manage funds and programs internally or partner with external experts? Internal management within an agency offers control and accountability but can strain agency capacity and impede the ability to be an active market participant. It is also difficult to attract the right talent within the government’s pay scale, leading to an inability to recruit and high turnover. This model has been attempted through programs like the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office (LPO), but even that market-based program has been slower to execute, delaying critical infrastructure and technology investments by months, if not years.

On the other hand, external management brings specialized expertise and market agility, yet it raises questions about oversight and influence. No matter who the private party is, there is skepticism around the use of funds, their personal or professional gain, and their intentions with taxpayer money. In our deeply politicized world, this puts a target on the leaders of these organizations that may limit who is willing to play this role.

Quasi-public Structures

Despite the challenges, on balance it seems that internal agency management or a quasi-public structure is the most feasible path. Internal management pushes the boundaries of public agency function but goes a long way to build trust and accountability. Quasi-public structures seem to be a good compromise when feasible. Other countries have figured out how to manage these programs within a government or quasi-government agency (see the Clean Energy Finance Corporation and Reconstruction Finance Corporation, both in Australia). We can too.

At the federal level, credit programs should be managed by agencies with the skills and capacities to hold an investment function, like the Department of Energy or the Treasury Department, and leverage lessons learned from programs like DOE’s LPO and EPA’s GGRF to structure new entities. Or – like many of the state and local green banks have done – create quasi-public entities that have public sector governance and appropriations but otherwise operate independently as financial institutions with their own balance sheets, bonding authority, and staffing structure.

Lastly, if public-private partnerships are preferred, who should the government work with to implement policies meant to expand access to capital and credit? Nonprofit financial institutions often prioritize mission, community impact and are willing to arrange complex financings that require a higher touch approach but often lack scale and institutional capital access. For-profit firms bring scale and expertise but often find it hard to manage a government program with a mindset or culture that differs from their typical profit-maximization frameworks.

Depository institutions such as banks offer stability and regulatory oversight, whereas non-depositories can innovate more freely to reach the hardest to serve communities. Regulated entities provide robust and trusted infrastructure and controls, but unregulated actors may move faster and can be more creative in supporting traditionally under-resourced opportunities. Specialty firms bring deep sector or asset-class knowledge, while generalists offer broad reach and experience in managing across asset classes.

To identify the optimal path, it is helpful to look to existing programs for lessons. The U.S. Treasury’s Emergency Capital Investment Program (ECIP) demonstrates how direct investment into regulated depository institutions can mobilize significant capital for underserved communities through an existing financial ecosystem. The Loan Programs Office shows what internal management can achieve for large-scale projects. Tax credit programs like the New Markets Tax Credit (NMTC) and Investment Tax Credit (ITC)/Production Tax Credit (PTC) illustrate how incentives can transform markets, while guarantee programs such as the U.S. Department of the Treasury’s Community Development Financial Institutions Fund (CDFI) Fund Bond Guarantee and SBA 7(a) and 504 guarantees highlight the power of risk mitigation in activating and standardizing products to support secondary market access. These precedents offer valuable insights as we design future policies to accelerate a broadly beneficial energy transition.

Educating policymakers to build trust in the community finance ecosystem

Regardless of path forward, one thing remains critical – building better relationships between policymakers and the community finance industry, including community banks, credit unions, loan funds, and green banks. These are the boots-on-the-ground organizations that share a mission with many policymakers to expand economic opportunity and broaden access to capital and credit. And they are often the organizations navigating multiple public products and programs to bring affordable, quality financial services to communities.

The challenge is that most advocacy and educational work for these organizations has been siloed – there are groups representing credit unions big and small, those representing housing lenders, loan funds, green banks, and community banks. The disaggregation of these efforts has diluted the potential for policymakers to look at this ecosystem as a whole to determine how best to leverage it for public good. This is not to say that each of these individual groups does not have a role to play for their members – they all have different needs and requirements and deserve representation. But the broader industry would benefit from collaboration across these organizations to create a mechanism for these institutions to help with outreach, advocacy and education around policy-enabled finance overall. This would bring a strong and powerful group of actors together for a higher collective purpose and, ideally, create a large and diverse constituency with common goals.

State and local governments stepping up

In the near-term, the absence of federal support for clean technology deployment through policy-enabled finance creates an enormous opportunity for state and local governments to step up and push forward. Hundreds of local financial institutions were doing work to prepare for the delivery of GGRF funds to and through local projects and businesses to drive broader adoption of clean technologies. These organizations continue to have the skillsets, capacity, and pipeline to finance these projects – but need access to flexible and affordable capital to do so.

State funding efforts could mirror the program and product design of the GGRF to get deals done locally, working with one or more of the constellation of financial institutions preparing to deploy federal funds. Just because the GGRF’s programs were cut short, it doesn’t mean that the infrastructure and learnings generated should go to waste – if there are public institutions willing to commit capital, there should be many financial institutions across the country ready to put it to good use.

Conclusion

If our shared goal is an equitable, rapid energy transition, policy must do more than regulate — it must enable finance and focus on deployment, or getting great projects done. The Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund showed both the promise and the pitfalls of large-scale, policy-enabled finance: when designed and governed well, these tools can unlock private capital, deliver measurable local benefits, and sustain long-term market transformation. When implementation gaps and weak relationships persist, even well-intentioned programs become politically vulnerable and ripe for attack. To make these programs successful within our current political context, future efforts should prioritize clear governance, cross-sector capacity, and sustained stakeholder engagement so public dollars can catalyze private investment that reaches every community.

Agenda for an American Renewal

Imperative for a Renewed Economic Paradigm

So far, President Trump’s tariff policies have generated significant turbulence and appear to lack a coherent strategy. His original tariff schedule included punitive tariffs on friends and foes alike on the mistaken basis that trade deficits are necessarily the result of an unhealthy relationship. Although they have been gradually paused or reduced since April 2, the uneven rollout (and subsequent rollback) of tariffs continues to generate tremendous uncertainty for policymakers, consumers, and businesses alike. This process has weakened America’s geopolitical standing by encouraging other countries to seek alternative trade, financial, and defense arrangements.

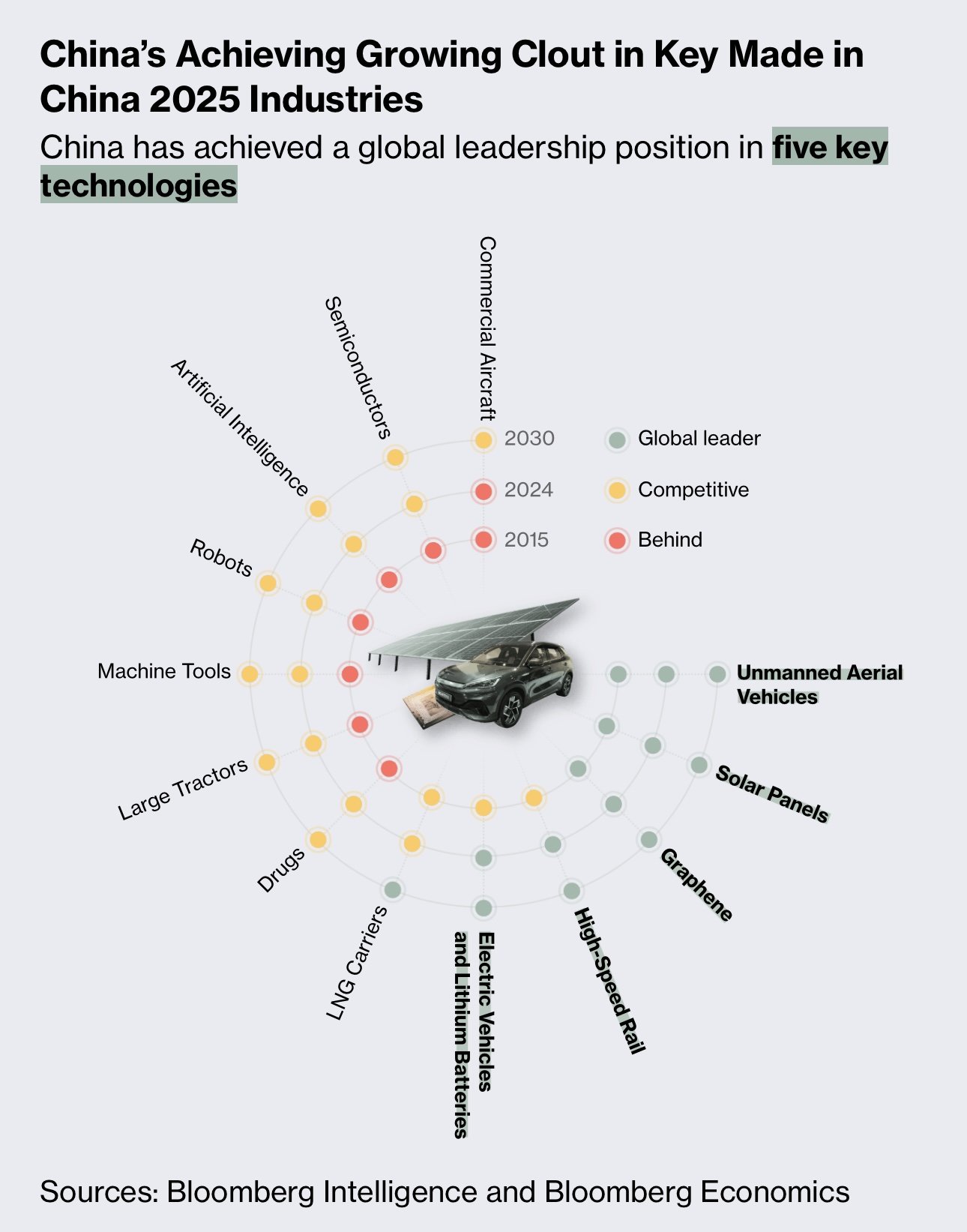

However, notwithstanding the uncoordinated approach to date, President Trump’s mistaken instinct for protectionism belies an underlying truth: that American manufacturing communities have not fared well in the last 25 years and that China’s dominance in manufacturing poses an ever-growing threat to national security. After China’s admission to the WTO in 2001, its share of global manufacturing grew from less than 10% to over 35% today. At the same time, America’s share of manufacturing shrank from almost 25% to less than 15%, with employment shrinking from more than 17 million at the turn of the century to under 13 million today. These trends also create a deep geopolitical vulnerability for America, as in the event of a conflict with China, we would be severely outmatched in our ability to build critical physical goods: for example, China produces over 80% of the world’s batteries, over 90% of consumer drones, and has a 200:1 shipbuilding capacity advantage over the U.S. While not all manufacturing is geopolitically valuable, the erosion in strategic industries, which went hand-in-hand with the loss of key manufacturing skills in recent decades, poses potential long-term challenges for America.

In addition to its growing manufacturing dominance, China is now competing with America’s preeminence in technology leadership, having leveraged many of the skills gained in science, engineering, and manufacturing for lower-value add industries to compete in higher-end sectors. DeepSeek demonstrated that China can natively generate high-quality artificial intelligence models, an area in which the U.S. took its lead for granted. Meanwhile, BYD rocketed past Tesla in EV sales and accounted for 22% of global sales in 2024 as compared to Tesla’s 10%. China has also been operating an extensive satellite-enabled secure quantum communications channel since 2016, preventing others from eavesdropping.

China’s growing leadership in advanced research may give it a sustained edge beyond its initial gains: according to one recent analysis of frontier research publications across 64 critical technologies, global leadership has shifted dramatically to China, which now leads in 57 research domains. These are not recent developments: they have been part of a series of five year plans, the most well known of which is Made in China 2025, giving China an edge in many critical technologies that will continue to grow if not addressed by an equally determined American response.

An Integrated Innovation, Economic Foreign Policy, and Community Development Approach

Despite China’s growing challenge and recent self-inflicted damage to America’s economic and geopolitical relationships, America still retains many ingrained advantages. The U.S. still has the largest economy, the deepest public and private capital pools for promising companies and technologies, and the world’s leading universities; it has the most advanced military, continues to count most of the world’s other leading armed forces as formal treaty allies, and remains the global reserve currency. Ordinary Americans have benefited greatly from these advantages in the form of access to cutting edge products and cheaper goods that increase their effective purchasing power and quality of life – notwithstanding Secretary Bessent’s statements to the contrary.

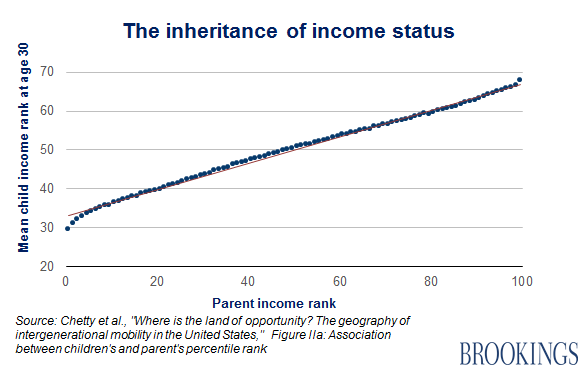

The U.S. would be wise to leverage its privileged position in high-end innovation and in global financial markets to build “industries of the future.” However, the next economic and geopolitical paradigm must be genuinely equitable, especially to domestic communities that have been previously neglected or harmed by globalization. For these communities, policies such as the now-defunct Trade Adjustment Assistance program were too slow and too reactive to help workers displaced by the “China Shock,” which is estimated to have caused up to 2.4 million direct and indirect job losses.

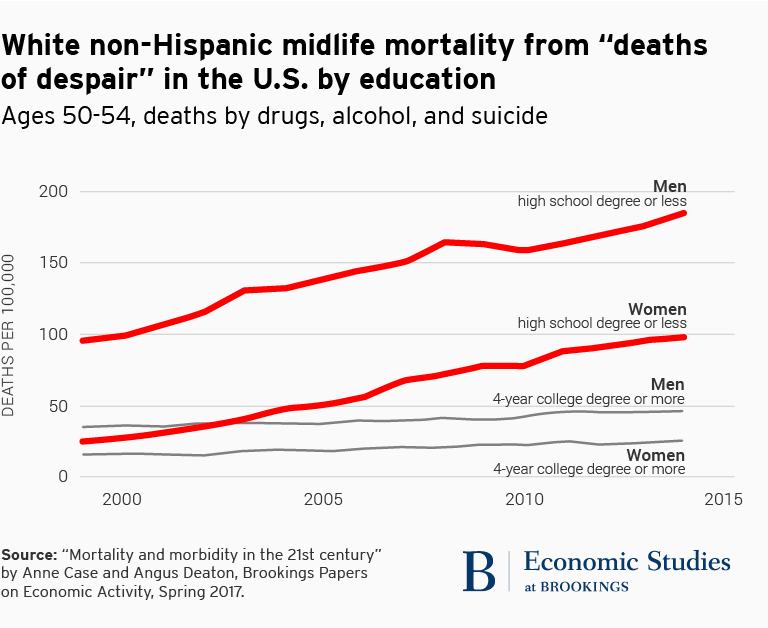

Although jobs in trade-affected communities were eventually “replaced,” the jobs that came after were disproportionately lower-earning roles, accrued largely to individuals who had college degrees, and were taken by new labor force entrants rather than providing new opportunities for those who had originally been displaced. Moreover, as a result of ineffective policy responses, this replacement took over a decade and has contributed to heinous effects: look no further than the rate at which “deaths of despair” for white individuals without a college degree skyrocketed after 2000.

Nonetheless, surrendering America’s hard-won advantages in technology and international commerce, especially in the face of a growing challenge from China, would be an existential error. Rather, our goal is to address the shortcomings of previous policy approaches to the negative externalities caused by globalization. Previous approaches have focused on maximizing growth and redistributing the gains, but in practice, America failed to do either by underinvesting in the foundational policies that enable both. Thus, we are proposing a two-pronged approach that focuses on spurring cutting-edge technologies, growing novel industries, and enhancing production capabilities while investing in communities in a way that provides family-supporting, upwardly mobile jobs as well as critical childcare, education, housing, and healthcare services. By investing in broad-based prosperity and productivity, we can build a more equitable and dynamic economy.

Our agenda is intentionally broad (and correspondingly ambitious) rather than narrow in focus on manufacturing communities, even though current discourse is focused on trade. This is not simply a “political bargain” that provides greater welfare or lip-service concessions to hollowed-out communities in exchange for a return to the prior geoeconomic paradigm. Rather, we genuinely believe that economic dynamism which is led by an empowered middle-class worker, whether they work in manufacturing or in a service industry, is essential to America’s future prosperity and national security – one in which economic outcomes are not determined by parental income and one where black-white disparities are closed in far less than the current pace of 150+ years.

Thus, the ideas and agenda presented here are neither traditionally “liberal” nor “conservative,” “Democrat” nor “Republican.” Instead, we draw upon the intellectual traditions of both segments of the political spectrum. We agree with Ezra Klein’s and Derek Thompson’s vision in Abundance for a technology-enabled future in which America remembers how to build; at the same time, we take seriously Oren Cass’s view in The Once and Future Worker that the dignity of work is paramount and that public policy should empower the middle-class worker. What we offer in the sections below is our vision for a renewed America that crosses traditional policy boundaries to create an economic and political paradigm that works for all.

Policy Recommendations

Investing in American Innovation

Given recent trends, it is clear that there is no better time to re-invigorate America’s innovation edge by investing in R&D to create and capture “industries of the future,” re-shoring capital and expertise, and working closely with allies to expand our capabilities while safeguarding those technologies that are critical to our security. These investments will enable America to grow its economic potential, providing fertile ground for future shared prosperity. We emphasize five key components to renewing America’s technological edge and manufacturing base:

Invest in R&D. Increase federally funded R&D, which has declined from 1.8% of GDP in the 1960s to 0.6% of GDP today. Of the $200 billion federal R&D budget, just $16 billion is allocated to non-healthcare basic science, an area in which the government is better suited to fund than the private sector due to positive spillover effects from public funding. A good start is fully funding the CHIPS and Science Act, which authorized over $200 billion over 10 years for competitiveness-enhancing R&D investments that Congress has yet to appropriate. Funding these efforts will be critical to developing and winning the race for future-defining technologies, such as next-gen battery chemistries, quantum computing, and robotics, among others.

Capability-Building. Develop a coordinated mechanism for supporting translation and early commercialization of cutting-edge technologies. Otherwise, the U.S. will cede scale-up in “industries of the future” to competitors: for example, Exxon developed the lithium-ion battery, but lost commercialization to China due to the erosion of manufacturing skills in America that are belatedly being rebuilt. However, these investments are not intended to be a top-down approach that selects winners and losers: rather, America should set a coordinated list of priorities (leveraging roadmaps such as the DoD’s Critical Technology Areas), foster competition amongst many players, and then provide targeted, lightweight financial support to industry clusters and companies that bubble to the top.

Financial support could take the form of a federally-funded strategic investment fund (SIF) that partners with private sector actors by providing catalytic funding (e.g., first-loss loans). This fund would focus on bridging the financing gap in the “valley of death” as companies transition from prototype to first-of-a-kind / “nth-of-a-kind” commercial product. In contrast to previous attempts at industrial policy, such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or CHIPS Act, they should have minimal compliance burdens and focus on rapidly deploying capital to communities and organizations that have proven to possess a durable competitive advantage.

Encourage Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Provide tax incentives and matching funds (potentially from the SIF) for companies who build manufacturing plants in America. This will bring critical expertise that domestic manufacturers can adopt, especially in industries that require deep technical expertise that America would need to redevelop (e.g., shipbuilding). By striking investment deals with foreign partners, America can “learn from the best” and subsequently improve upon them domestically. In some cases, it may be more efficient to “share” production, with certain components being manufactured or assembled abroad, while America ramps up its own capabilities.

For example, in shipbuilding, the U.S. could focus on developing propulsion, sensor, and weapon systems, while allies such as South Korea and Japan, who together build almost as much tonnage as China, convert some shipyards to defense production and send technical experts to accelerate development of American shipyards. In exchange, they would receive select additional access to cutting-edge systems and financially benefit from investing in American shipbuilding facilities and supply chains.

Immigration. America has long been described as a “nation of immigrants.” Their role in innovation is impossible to deny: 46% of companies in the Fortune 500 were founded by immigrants and accounted for 24% of all founders; they are 19% of the overall STEM workforce but account for nearly 60% of doctorates in computer science, mathematics, and engineering. Rather than spurning them, the U.S. should attract more highly educated immigrants by removing barriers to working in STEM roles and offering accelerated paths to citizenship. At the same time, American policymakers should acknowledge the challenges caused by illegal immigration. One such solution is to pass legislation such as the Border Control Act of 2024, which had bipartisan support and increased border security, supplemented by a “points-based” immigration system such as Canada’s which emphasizes educational credentials and in-country work experience.

Create Targeted Fences. Employ tariffs and export controls to defend nascent, strategically important industries such as advanced chips, fusion energy, or quantum communications. However, rather than employing these indiscriminately, tariffs and export controls should be focused on ensuring that only America and its allies have access to cutting-edge technologies that shape the global economic and security landscape. They are not intended to keep foreign competition out wholesale; rather, they should ensure that burgeoning technology developers gain sufficient scale and traction by accelerating through the “learn curve.”

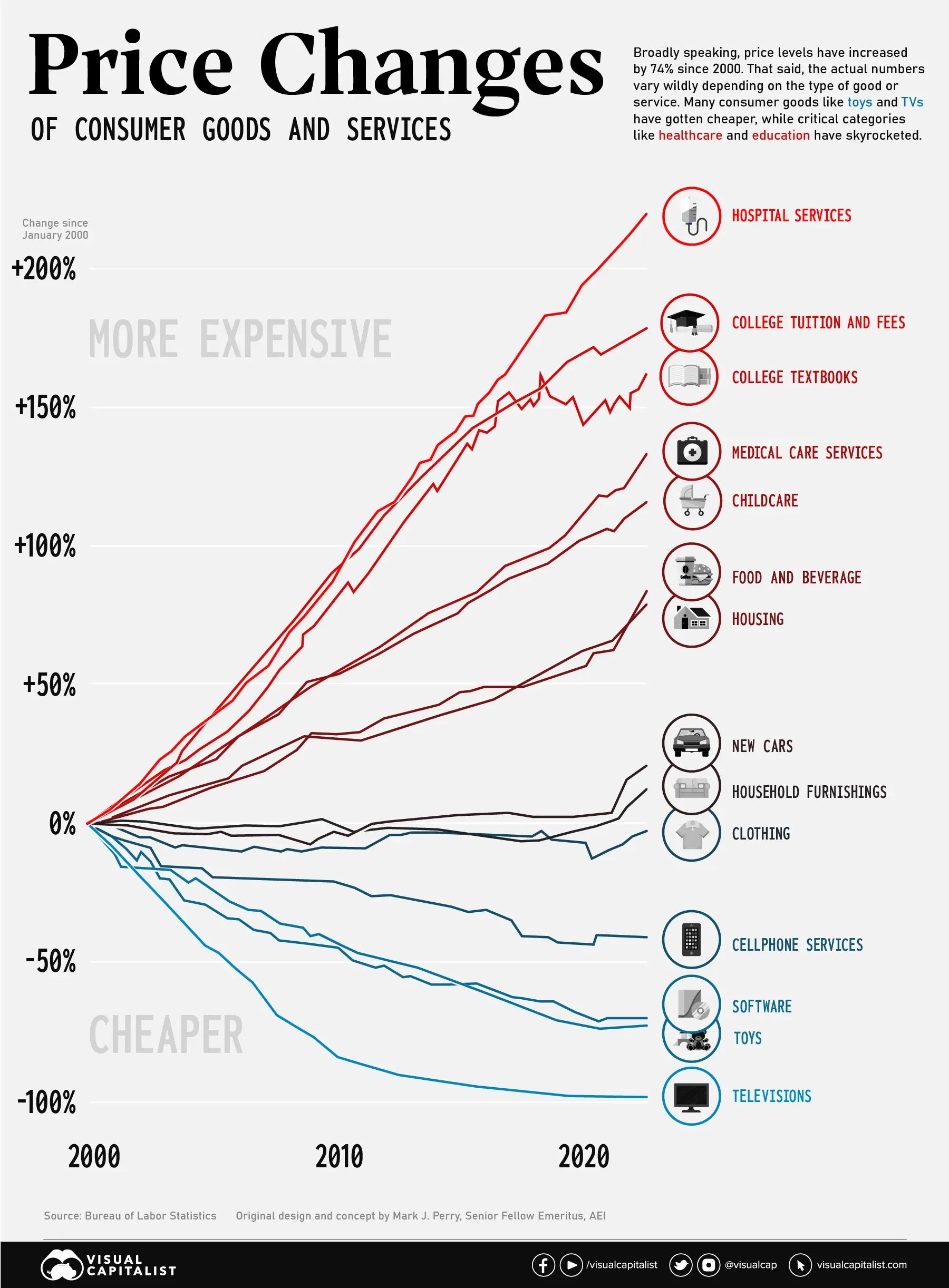

Building Strong Communities

Strong communities are the foundation of a strong workforce, without which new industries will not thrive beyond a small number of established tech hubs. However, strengthening American communities will require the country to address the core needs of a family-sustaining life. Childcare, education, housing, and healthcare are among the largest budget items for families and have been proven time and again to be critical to economic mobility. Nevertheless, they are precisely the areas in which costs have skyrocketed the most, as has been frequently chronicled by the American Enterprise Institute’s “Chart of the Century.” These essential services have been underinvested in for far too long, creating painful shortages for communities that need them most. As such, addressing these issues form the core pillars of our domestic reinvestment plan. Addressing them means grappling with the underlying drivers of their cost and scarcity. These include issues of state capacity, regulatory and licensing barriers, and low productivity growth in service-heavy care sectors. A new policy agenda that addresses the fundamental supply-side issues is needed to reshape the contours of this debate.

Expand Childcare. Inadequate childcare costs the U.S. economy $122 billion in lost wages and productivity as otherwise capable workers, especially women, are forced to reduce hours or leave the labor force. Access is further exacerbated by supply shortages: more than half the population lives in a “childcare desert,” where there are more than three times as many children as licensed slots. Addressing these shortages will alleviate the affordability issue, enabling workers to stay in the workforce and allow families to move up the income ladder.

Fund Early Education. Investments in early childhood education have been demonstrated to generate compelling ROI, with high-quality studies such as the Perry preschool study demonstrating up to $7 – $12 of social return for every $1 invested. While these gains are broadly applicable across the country, they would make an even greater difference in helping to rebuild manufacturing communities by making it easier to grow and sustain families. Given the return on investment and impact on social mobility, American policymakers should consider investing in universal pre-K.

Invest in Workforce Training and Community Colleges. The cost of a four-year college education now exceeds $38K per year, indicating a clear need for cheaper BA degrees but also credible alternatives. At the same time, community colleges can be reimagined and better funded to enable them to focus on high-paying jobs in sectors with critical labor shortages, many of which are in or adjacent to “industries of the future.” Some of these roles, such as IT specialists and skilled tradespeople, are essential to manufacturing. Others, such as nursing and allied healthcare roles, will help build and sustain strong communities.

Build Housing Stock. America has a shortage of 3.2 million homes. Simply put, the country needs to build more houses to address the cost of living and enable Americans to work and raise families. While housing policy is generally decided at lower levels of government, the federal government should provide grants and other incentives to states and municipalities to defray the cost of developing affordable housing; in exchange, state and local jurisdictions should relax zoning regulations to enable more multi-family and high-density single-family housing.

Expand Healthcare Access. American healthcare is plagued with many problems, including uneven access and shortages in primary care. For example, the U.S. has 3.1 primary care physicians (PCPs) per 10,000 people, whereas Germany has 7.1 and France has 9.0. As such, the federal government should focus on expanding the number of healthcare practitioners (especially primary care physicians and nurses), building a physical presence for essential healthcare services in underserved regions, and incentivizing the development of digital care solutions that deliver affordable care.

Allocating Funds to Invest in Tomorrow’s Growth

Investment Requirements

While we view these policies as essential to America’s reinvigoration, they also represent enormous investments that must be paid for at a time when fiscal constraints are likely to tighten. To create a sense of the size of the financial requirements and trade-offs required, we lay out each of the key policy prescriptions above and use bipartisan proposals wherever possible, many of which have been scored by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) or another reputable institution or agency. Where this is not possible, we created estimates based on key policy goals to be accomplished. Although trade deals and targeted tariffs are likely to have some budget impact, we did not evaluate them given multiple countervailing forces and political uncertainties (e.g., currency impacts).

Potential Pay-Fors

Given the budgetary requirements of these proposals, we looked for opportunities to prune the federal budget. The CBO laid out a set of budgetary options that collectively could save several trillion over the next decade. In laying out the potential pay-fors, we used two approaches that focused on streamlining mandatory spending and optimizing tax revenues in an economically efficient manner. Our first approach is to include budgetary options that eliminate unnecessary spending that are distortionary in nature or are unlikely to have a meaningful direct impact on the population that they are trying to serve (e.g., kickback payments to state health plans). Our second approach is to include budgetary options in which the burden would fall upon higher-earning populations (e.g., raising the cap on payroll and Social Security taxes).

As the table below shows, there is a menu of options available to policymakers that raise funding well in excess of the required investment amounts above, allowing them to pick and choose which are most economically efficient and politically viable. In addition, they can modify many of these options to reduce the size or magnitude of the effect of the policy (e.g., adjust the point at which Social Security benefits for “high earners” is tapered or raise capital gains by 1% instead of 2%). While some of these proposals are potentially controversial, there is a clear and pressing need to reexamine America’s foundational policy assumptions without expanding the deficit, which is already more than 6% of GDP.

Conclusion

America is in need of a new economic paradigm that renews and refreshes rather than dismantles its hard-won geopolitical and technological advantages. Trump’s tariffs, should they be fully enacted, would be a self-defeating act that would damage America’s economy while leaving it more vulnerable, not less, to rivals and adversaries. However, we also recognize that the previous free trade paradigm was not truly equitable and did not do enough to support manufacturing communities and their core strengths. We believe that our two-pronged approach of investing in American innovation alongside our allies along with critical community investments in childcare, higher education, housing, and healthcare bridges the gap and provides a framework for re-orienting the economy towards a more prosperous, fair, and secure future.

Driving Product Model Development with the Technology Modernization Fund

The Technology Modernization Fund (TMF) currently funds multiyear technology projects to help agencies improve their service delivery. However, many agencies abdicate responsibility for project outcomes to vendors, lacking the internal leadership and project development teams necessary to apply a product model approach focused on user needs, starting small, learning what works, and making adjustments as needed.

To promote better outcomes, TMF could make three key changes to help agencies shift from simply purchasing static software to acquiring ongoing capabilities that can meet their long-term mission needs: (1) provide education and training to help agencies adopt the product model; (2) evaluate investments based on their use of effective product management and development practices; and (3) fund the staff necessary to deliver true modernization capacity.

Challenge and Opportunity

Technology modernization is a continual process of addressing unmet needs, not a one-time effort with a defined start and end. Too often, when agencies attempt to modernize, they purchase “static” software, treating it like any other commodity, such as computers or cars. But software is fundamentally different. It must continuously evolve to keep up with changing policies, security demands, and customer needs.

Presently, agencies tend to rely on available procurement, contracting, and project management staff to lead technology projects. However, it is not enough to focus on the art of getting things done (project management); it is also critically important to understand the art of deciding what to do (product management). A product manager is empowered to make real-time decisions on priorities and features, including deciding what not to do, to ensure the final product effectively meets user needs. Without this role, development teams typically march through a vast, undifferentiated, unprioritized list of requirements, which is how information technology (IT) projects result in unwieldy failures.

By contrast, the product model fosters a continuous cycle of improvement, essential for effective technology modernization. It empowers a small initial team with the right skills to conduct discovery sprints, engage users from the outset and throughout the process, and continuously develop, improve, and deliver value. This approach is ultimately more cost effective, results in continuously updated and effective software, and better meets user needs.

However, transitioning to the product model is challenging. Agencies need more than just infrastructure and tools to support seamless deployment and continuous software updates – they also need the right people and training. A lean team of product managers, user researchers, and service designers who will shape the effort from the outset can have an enormous impact on reducing costs and improving the effectiveness of eventual vendor contracts. Program and agency leaders, who truly understand the policy and operational context, may also require training to serve effectively as “product owners.” In this role, they work closely with experienced product managers to craft and bring to life a compelling product vision.

These internal capacity investments are not expensive relative to the cost of traditional IT projects in government, but they are currently hard to make. Placing greater emphasis on building internal product management capacity will enable the government to more effectively tackle the root causes that lead to legacy systems becoming problematic in the first place. By developing this capacity, agencies can avoid future costly and ineffective “modernization” efforts.

Plan of Action

The General Services Administration’s Technology Modernization Fund plays a crucial role in helping government agencies transition from outdated legacy systems to modern, secure, and efficient technologies, strengthening the government’s ability to serve the public. However, changes to TMF’s strategy, policy, and practice could incentivize the broader adoption of product model approaches and make its investments more impactful.

The TMF should shift from investments in high-cost, static technologies that will not evolve to meet future needs towards supporting the development of product model capabilities within agencies. This requires a combination of skilled personnel, technology, and user-centered approaches. Success should be measured not just by direct savings in technology but by broader efficiencies, such as improvements in operational effectiveness, reductions in administrative burdens, and enhanced service delivery to users.

While successful investments may result in lower costs, the primary goal should be to deliver greater value by helping agencies better fulfill their missions. Ultimately, these changes will strengthen agency resilience, enabling them to adapt, scale, and respond more effectively to new challenges and conditions.

Recommendation 1. The Technology Modernization Board, responsible for evaluating proposals, should:

- Assess future investments based on the applicant’s demonstrated competencies and capacities in product ownership and management, as well as their commitment to developing these capabilities. This includes assessing proposed staffing models to ensure the right teams are in place.

- Expand assessment criteria for active and completed projects beyond cost savings, to include measurements of improved mission delivery, operational efficiencies, resilience, and adaptability.

Recommendation 2. The TMF Program Management Office, responsible for stewarding investments from start to finish, should:

- Educate and train agencies applying for funds on how to adopt and sustain the product model.

- Work with the General Services Administration’s 18F to incorporate TMF project successes and lessons learned into a continuously updated product model playbook for government agencies that includes guidance on the key roles and responsibilities needed to successfully own and manage products in government.

- Collaborate with the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) to ensure that agencies have efficient and expedited pathways for acquiring the necessary talent, utilizing appropriate assessments to identify and onboard skilled individuals.

Recommendation 3. Congress should:

- Encourage agencies to set up their own working capital funds under the authorities outlined in the TMF legislation.

- Explore the barriers to product model funding in the current budgeting and appropriations processes for the federal government as a whole and develop proposals for fitting them to purpose.

- Direct OPM to reduce procedural barriers that hinder swift and effective hiring.

Conclusion

The TMF should leverage its mandate to shift agencies towards a capabilities-first mindset. Changing how the program educates, funds, and assesses agencies will build internal capacity and deliver continuous improvement. This approach will lead to better outcomes, both in the near and long terms, by empowering agencies to adapt and evolve their capabilities to meet future challenges effectively.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Congress established TMF in 2018 “to improve information technology, and to enhance cybersecurity across the federal government” through multiyear technology projects. Since then, more than $1 billion has been invested through the fund across dozens of federal agencies in four priority areas.

White House Issues a “National” Science & Tech Agenda

A new White House budget memo presents science and technology as a distinctly American-led enterprise in which U.S. dominance is to be maintained and reinforced. The document is silent on the possibility or the necessity of international scientific cooperation.

“The five R&D budgetary priorities in this memorandum ensure that America remains at the forefront of scientific progress, national and economic security, and personal wellbeing, while continuing to serve as the standard-bearer for today’s emerging technologies and Industries of the Future,” wrote Acting OMB Director Russell T. Vought and White House science advisor Dr. Kelvin K. Droegemeier in the August 30 memo.

The document, which is intended to inform executive branch budget planning for fiscal year 2021, contains no acknowledgment that many scientific challenges are global in scope, that foreign countries lead the U.S. in some areas of science and technology, or that the U.S. could actually benefit from international collaboration.

* * *

The White House memo begins by designating the entire post-World War II period until now as America’s “First Bold Era in S&T [Science & Technology].” It goes on to proclaim that the “Second Bold Era in S&T” has now begun under President Trump.

“The Trump Administration continues to prioritize the technologies that power Industries of the Future (IotF),” the memo declares.

Many of the proposed technology priorities are already in progress — including artificial intelligence, robotics, and gene therapy. Some are controversial or disputed — such as the purported need to invest in protection against electromagnetic pulse attacks.

Meanwhile, the memo takes pains to avoid even mentioning the term “climate change,” which is disfavored by this White House. Instead, it speaks of “Earth system predictability” and “knowing the extent to which components of the Earth system are practically predictable.”

Today’s Second Bold Era is “characterized by unprecedented knowledge, access to data and computing resources, ubiquitous and instant communication,” and so on. “Unfortunately, this Second Bold Era also features new and extraordinary threats which must be confronted thoughtfully and effectively.”

The White House guidance suggests vaguely that the Second Bold Era could require a recalibration of secrecy policy in science and technology. “[Success] will depend upon striking a balance between the openness of our research ecosystem and the protection of our ideas and research outcomes.”

This may or may not augur a change in the longstanding policy of openness in basic research that was formally adopted in President Reagan’s 1985 National Security Decision Directive 189. That directive stated that “It is the policy of this Administration that, to the maximum extent possible, the products of fundamental research remain unrestricted.”

* * *

The context for the concern about protecting U.S. ideas and research outcomes is an assessment that U.S. intellectual property is being aggressively targeted and illicitly acquired by China, among other countries.

“China has expansive efforts in place to acquire U.S. technology to include sensitive trade secrets and proprietary information,” according to a 2018 report from the National Counterintelligence and Security Center. “Chinese companies and individuals often acquire U.S. technology for commercial and scientific purposes.”

Perceived Chinese theft of U.S. intellectual property is one of the factors that led to imposition of U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports. See U.S.-China Relations, Congressional Research Service, August 29, 2019.

* * *

At an August 30 briefing on artificial intelligence in the Department of Defense, Air Force Lt. General Jack Shanahan discussed the need to protect military data in the context of AI.

But unlike the new White House memo, Gen. Shanahan recognized the need for international cooperation even (or especially) in national security matters:

“We’re very interested in actively engaging a number of international partners,” he said, “because if you envision a future of which the United States is employing A.I. in its military capabilities and other nations are not, what does that future look like? Does the commander trust one and not the other?”

By analogy, however, the same need for international collaboration arises in many other areas of science and technology which cannot be effectively addressed solely on a national basis, from mitigating climate change to combating disease. In such cases, everyone needs to be “at the forefront” together.

* * *

One way to bolster U.S. scientific and intellectual leadership that the White House memo does not contemplate is to encourage foreign students at American universities to remain in this country. Too often, they are discouraged from doing so, wrote Columbia University Lee C. Bollinger in the Washington Post.

“Many of these international scholars, especially in the fields of science, technology, engineering and mathematics, would, if permitted, prefer to remain in the United States and work for U.S.-based companies after graduation, where they could also contribute to the United States’ economic growth and prosperity. But under the present rules, when their academic studies are completed, we make it difficult for them to stay. They return to their countries with the extraordinary knowledge they acquired here, which can inform future commercial strategies deployed against U.S. competitors,” Bollinger wrote on August 30.

* * *

As for the Trump Administration’s pending FY2020 budget request for research and development, it does not convey much in the way of boldness (or Boldness).

“Under the President’s FY2020 budget request, most federal agencies would see their R&D funding decline. The primary exception is the Department of Defense,” according to the Congressional Research Service.

“The President’s FY2020 budget request would reduce funding for basic research by $1.5 billion (4.0%), applied research by $4.3 billion (10.5%), and facilities and equipment by $0.5 billion (12.8%), while increasing funding for development by $4.5 billion (8.3%).” See Federal Research and Development (R&D) Funding: FY2020, updated August 13, 2019.

Navy Torpedoes Scientific Advisory Group

This week the U.S. Navy abruptly terminated its own scientific advisory group, depriving the service of a source of internal critique and evaluation.

The Naval Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) was established by legislation in 1946 and provided science and technology advice to the Navy for the past 73 years. Now it’s gone.

The decision to disestablish the Committee was announced in a March 29 Federal Register notice, which did not provide any justification for eliminating it. Phone and email messages to the office of the Secretary of the Navy seeking more information were not returned.

“I think it’s a shortsighted move,” said one Navy official, who was not part of the decisionmaking process.

This official said that the Committee had been made vulnerable by an earlier effort to reduce the number of Navy advisory committees. Instead of remaining an independent entity, the NRAC was redesignated as a sub-committee of the Secretary of the Navy Advisory Panel, which provides policy advice to the Secretary. It was a poor fit for the NRAC technologists, the official said, since they don’t do policy and were thus “misaligned.” When the Secretary decided to eliminate the Panel, the NRAC was swept away with it.

Did the NRAC do or say something in particular to trigger the Navy’s wrath? If so, it’s unclear what that might have been. “This is the most highly professional crew I’ve seen,” the Navy official said. “They stay between the lines.”

The NRAC was the Navy counterpart to the Army Science Board and the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. It has no obvious replacement.

“This will leave the Navy without an independent and objective technical advisory body, which is not in the best interests of the Navy or the nation,” said a Navy scientist.

According to the NRAC website (which is still online for now), “The Naval Research Advisory Committee (NRAC) is an independent civilian scientific advisory group dedicated to providing objective analyses in the areas of science, research and development. By its recommendations, the NRAC calls attention to important issues and presents Navy management with alternative courses of action.”

Its mission was “To know the problems of the Navy and Marine Corps, keep abreast of the current research and development programs, and provide an independent, objective assessment capability through investigative studies.”

A 2017 report on Autonomous and Unmanned Systems in the Department of the Navy appears to be the NRAC’s most recent unclassified published report.

Under Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modly ordered disestablishment of the NRAC in a 21 February 2019 memo.

“This was a sudden and unexpected move according to people I know,” said the Navy scientist. “I have not yet seen an explanation for its termination.”

A Profile of Defense Science & Tech Spending

Annual spending on defense science and technology has “grown substantially” over the past four decades from $2.3 billion in FY1978 to $13.4 billion in FY2018 or by nearly 90% in constant dollars, according to a new report from the Congressional Research Service.

Defense science and technology refers to the early stages of military research and development, including basic research (known by its budget code 6.1), applied research (6.2) and advanced technology development (6.3).

“While there is little direct opposition to Defense S&T spending in its own right,” the CRS report says, “there is intense competition for available dollars in the appropriations process,” such that sustained R&D spending is never guaranteed.

Still, “some have questioned the effectiveness of defense investments in R&D.”

CRS takes note of a 2012 article published by the Center for American Progress which argued that military spending was an inefficient way to spur innovation and that the growing sophistication of military technology was poorly suited to meet some low-tech threats such as improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in Iraq and Afghanistan (as discussed in an earlier article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists).

The new CRS report presents an overview of the defense science and tech budget, its role in national defense, and questions about its proper size and proportion. See Defense Science and Technology Funding, February 21, 2018,

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response, updated February 16, 2018

Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations, updated February 16, 2018

Bahrain: Reform, Security, and U.S. Policy, updated February 15, 2018

Potential Options for Electric Power Resiliency in the U.S. Virgin Islands, February 14, 2018

U.S. Manufacturing in International Perspective, updated February 21, 2018

Methane and Other Air Pollution Issues in Natural Gas Systems, updated February 15, 2018

Where Can Corporations Be Sued for Patent Infringement? Part I, CRS Legal Sidebar, February 20, 2018

How Broad A Shield? A Brief Overview of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, CRS Legal Sidebar, February 21, 2018

Russians Indicted for Online Election Trolling, CRS Legal Sidebar, February 21, 2018

Hunting and Fishing on Federal Lands and Waters: Overview and Issues for Congress, February 14, 2018

US-China Scientific Cooperation “Mutually Beneficial”

The US and China have successfully carried out a wide range of cooperative science and technology projects in recent years, the State Department told Congress last year in a newly released report.

Joint programs between government agencies on topics ranging from pest control to elephant conservation to clean energy evidently worked to the benefit of both countries.

“Science and technology engagement with the United States continues to be highly valued by the Chinese government,” the report said.

At the same time, “Cooperative activities also accelerated scientific progress in the United States and provided significant direct benefit to a range of U.S. technical agencies.”

The 2016 biennial report to Congress, released last week under the Freedom of Information Act, describes programs that were ongoing in 2014-2015.

See Implementation of Agreement between the United States and China on Science and Technology, report to Congress, US Department of State, April 2016.

Science & Technology Issues Facing Congress, & More from CRS

Science and technology policy issues that may soon come before Congress were surveyed in a new report from the Congressional Research Service.

Overarching issues include the impact of recent reductions in federal spending for research and development.

“Concerns about reductions in federal R&D funding have been exacerbated by increases in the R&D investments of other nations (China, in particular); globalization of R&D and manufacturing activities; and trade deficits in advanced technology products, an area in which the United States previously ran trade surpluses. At the same time, some Members of Congress have expressed concerns about the level of federal funding in light of the current federal fiscal condition. In addition, R&D funding decisions may be affected by differing perspectives on the appropriate role of the federal government in advancing science and technology.”

See Science and Technology Issues in the 115th Congress, March 14, 2017.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

The American Health Care Act, March 14, 2017

Previewing a 2018 Farm Bill, March 15, 2017

EPA Policies Concerning Integrated Planning and Affordability of Water Infrastructure, updated March 14, 2017

National Park Service: FY2017 Appropriations and Ten-Year Trends, updated March 14, 2017

Qatar: Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, updated March 15, 2017

Northern Ireland: Current Issues and Ongoing Challenges in the Peace Process, updated March 14, 2017

Navy LX(R) Amphibious Ship Program: Background and Issues for Congress, updated March 14, 2017

Under Pressure: Long Duration Undersea Research

“The Office of Naval Research is conducting groundbreaking research into the dangers of working for prolonged periods of time in extreme high and low pressure environments.”

Why? In part, it reflects “the increased operational focus being placed on undersea clandestine operations,” said Rear Adm. Mathias W. Winter in newly published answers to questions for the record from a February 2016 hearing.

“The missions include deep dives to work on the ocean floor, clandestine transits in cold, dark waters, and long durations in the confines of the submarine. The Undersea Medicine Program comprises the science and technology efforts to overcome human shortfalls in operating in this extreme environment,” he told the House Armed Services Committee.

See DoD FY2017 Science and Technology Programs: Defense Innovation to Create the Future Military Force, House Armed Services Committee hearing, February 24, 2016.

Patents Granted to Two Formerly Secret Inventions