Don’t Let American Allies Go Nuclear

President Trump is moving quickly to push U.S. allies to invest even more in their own defense. NATO allies have already committed to spend 3% of their GDP on defense, yet the U.S. is now calling for them to spend at least 5%. It is likely that U.S. allies in East Asia will soon face similar calls to do more. Greater investments in conventional capabilities make a lot of sense. However, there are some U.S. policy experts, officials and academics calling for more U.S. allies to go nuclear to reduce U.S. defense requirements. These calls are dangerously misguided and ignore the threat any proliferation – including by U.S. allies – poses to American security interests. They must be rejected wholesale by the Trump Administration.

One of the most enduring successes of U.S. national security policy has been its effort to limit the number of states with nuclear weapons. Predictions that dozens of countries might possess nuclear weapons did not materialize because of concerted U.S. actions. The risks include the reality that U.S. allies can and often do experience internal instability or even regime collapse, that any state with nuclear weapons creates a risk that those materials or knowhow can be stolen or diverted, that any state with nuclear weapon in a crisis might actually use those weapons, and lastly the reality that states with their nuclear weapons are less susceptible open to U.S. influence. There may be reasons why a state may want to go nuclear from their own perspective but there are few if any lasting benefits to American security that comes from proliferation to friends and allies.

Nine countries currently have nuclear weapons, but perhaps 40 additional states are technically advanced enough to build nuclear weapons if they chose to do so. Many of these states are U.S. allies or partners, including in Europe as well as Japan, South Korea, and even the island of Taiwan. That these states never went nuclear (although some tried) is due to a combination of factors, including the credibility of U.S. defense commitments to their security, the pressure America brought to bear when these states indicated a potential interest in building independent nuclear arsenals, and the recognition that if the world was serious about getting rid of all nuclear weapons then their spread was a step in the wrong direction.

The re-election of Donald Trump has understandably spooked many U.S. allies, renewing doubts that America will come to their aid. The growth of China’s military and economic power relative to the United States is adding to these concerns. More allies are asking now, just as they did during the Cold War if America would really risk Boston to protect Berlin, or Seattle to protect Seoul. As this question festers and as America’s relative power over China and other states ebbs, the lure to encourage U.S. friends to develop nuclear weapons of their own to deter or defeat an attack will grow. After all, the theory goes, why should the United States worry if its friends go nuclear?

In the real world, however, the spread of nuclear weapons anywhere complicates and undermines U.S. security. One reason is states are not always stable. In the 1970s, the U.S. supported its Treaty partner Iran acquiring nuclear reactors and advanced technology but in 1979, that regime was overthrown by the Islamic Revolution. Pakistan went nuclear when the U.S. needed its help fighting the Soviets in Afghanistan, and has faced wave after wave of instability and crisis. And South Korea is a more recent challenge. For the last few decades, South Korea was considered a stable and vibrant democracy – even hosting a Summit for Democracy last year. Under President Yoon, South Korea has voiced increasing interest in an independent nuclear arsenal. And just last year, a former Trump official, Elbridge Colby, expected to serve in a senior policy role at the Pentagon publicly encouraged South Korea to build their own nuclear weapons to deter North Korea and enable the U.S. to focus more on China. The situation in South Korea, with an impeached President and no clear sense of who controls the country’s military, would be a lot more dangerous if Seoul had nuclear weapons.

This is not just an issue for newer nuclear weapons states. Prior to the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, a coup created confusion for days over exactly who had the ability to control Soviet nuclear weapons. Following the USSR’s demise, nuclear weapons and materials remained at risk of theft and diversion for years and required massive U.S. efforts and investments to prevent their loss. And even the United States is not immune from these risks. The 2021 insurrection raised nuclear risk to the point that the Speaker of the House had to publicly ask the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs about the risk that President Trump might use nuclear weapons in a gambit to remain in power, and Chairman Milley took extraordinary steps to insert himself into the nuclear chain of command to preempt that risk. Any nuclear arsenal anywhere is a potential danger if political circumstances change.

And states with nuclear weapons create a nuclear risk if nuclear technology, materials and knowhow are stolen or diverted. Five of today’s nuclear weapon states – America, Russia, China, France, and Pakistan – have either knowingly or unwittingly helped other states go nuclear. Even if theft or transfer were not an issue, when new states have gone nuclear in the past, others have followed. America’s nuclear success led the Soviet Union to build them as well. This in turn led the UK and France to follow suit. These four nuclear weapon programs fueled China’s desire to join the club. Beijing having the bomb drove India to do the same, which then led Pakistan to follow suit.

And any nuclear state might decide one day to use those weapons. Every nuclear leader must get every nuclear decision right, every time or boom. The history of U.S. and Soviet nuclear deterrence is marked as much by nuclear misunderstandings and potential accidents as by stable deterrence. India and Pakistan have the same problem. It is reasonable to assume new nuclear states with nuclear weapons would encounter many of the same risks.

And finally, from a very direct Americentric point of view, each state that acquires their own nuclear weapons lessens the ability of the United States to influence, control or dictate security outcomes in that state and region. While not the message U.S. diplomats use openly when trying to work diplomatically to stop proliferation, the issue of influence is as relevant to U.S. allies as adversaries. To the extent that the U.S. security is enhanced by being able to heavily influence how states around the world act, then enabling the spread of nuclear weapons undermines that ability.

It is and will continue to be tempting for the next Administration to find rapid and easy solutions to long-standing security challenges. Empowering U.S. allies to do more so Washington can do and spend less, or focus more effectively on fewer challenges is an understandable policy outcome. But enabling, or looking the other way at the spread of nuclear weapons is not in America’s interests anymore today than it was in the 20th century.

Over the Line: The Implications of China’s ADIZ Intrusions in Northeast Asia

When China established its first ADIZ in the East China Sea on November 23, 2013, the move was widely seen as a practice run before establishing one in the South China Sea to strengthen its controversial territorial claims. However, examining China’s use of its ADIZ the way its treatment of those of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan has evolved over the past seven years reveals that China’s East China Sea ADIZ has effectively given China new latitude to extend its influence in Northeast Asia.

Since 2013, China has committed more than 4,400 intrusions into the ADIZs of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Often, Chinese forces violate multiple countries’ ADIZs on their flights, flying routes that consecutively transgress South Korea’s and Japan’s ADIZs or Taiwan’s and Japan’s. While each country has so far managed the issue in its own way by scrambling jets, discussing the issue with China in bilateral meetings, and publicizing some information about the intrusions, the issue has become a regional one impacting all three countries.

This report uses data gathered from multilingual sources to explore China’s motivations behind these intrusions as well as the implications for Japanese, South Korean, Taiwanese, and U.S. forces operating in Northeast Asia.

Israel’s Official Map Replaces Military Bases with Fake Farms and Deserts

Somewhat unexpectedly, a blog post that I wrote last week caught fire internationally. On Monday, I reported that Yandex Maps—Russia’s equivalent to Google Maps—had inadvertently revealed over 300 military and political facilities in Turkey and Israel by attempting to blur them out.

In a strange turn of events, the fallout from that story has actually produced a whole new one.

After the story blew up, Yandex pointed out that its efforts to obscure these sites are consistent with its requirement to comply with local regulations. Yandex’s statement also notes that “our mapping product in Israel conforms to the national public map published by the government of Israel as it pertains to the blurring of military assets and locations.”

The “national public map” to which Yandex refers is the official online map of Israel which is maintained by the Israeli Mapping Centre (מרכז למיפוי ישראל) within the Israeli government. Since Yandex claims to take its cue from this map, I wondered whether that meant that the Israeli government was also selectively obscuring sites on its national map.

I wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Israeli government goes well beyond just blurring things out. They’re actually deleting entire facilities from the map—and quite messily, at that. Usually, these sites are replaced with patches of fake farmland or desert, but sometimes they’re simply painted over with white or black splotches.

Some of the more obvious examples of Israeli censorship include nuclear facilities:

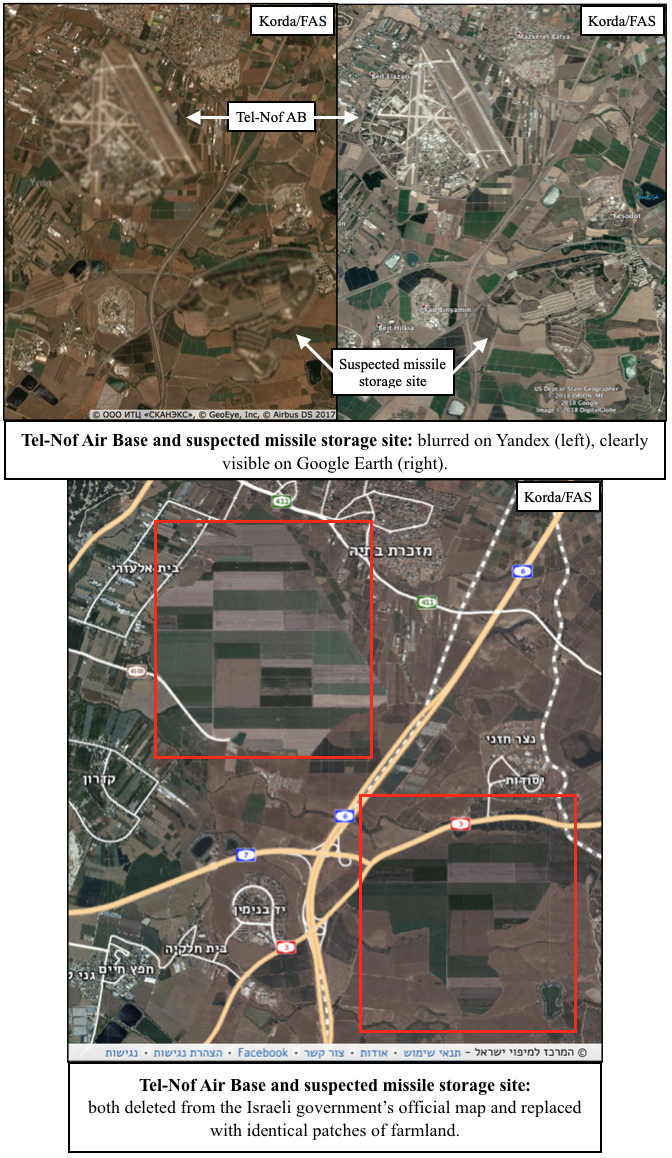

- Tel-Nof Air Base is just down the road from a suspected missile storage site, both of which have been painted over with identical patches of farmland.

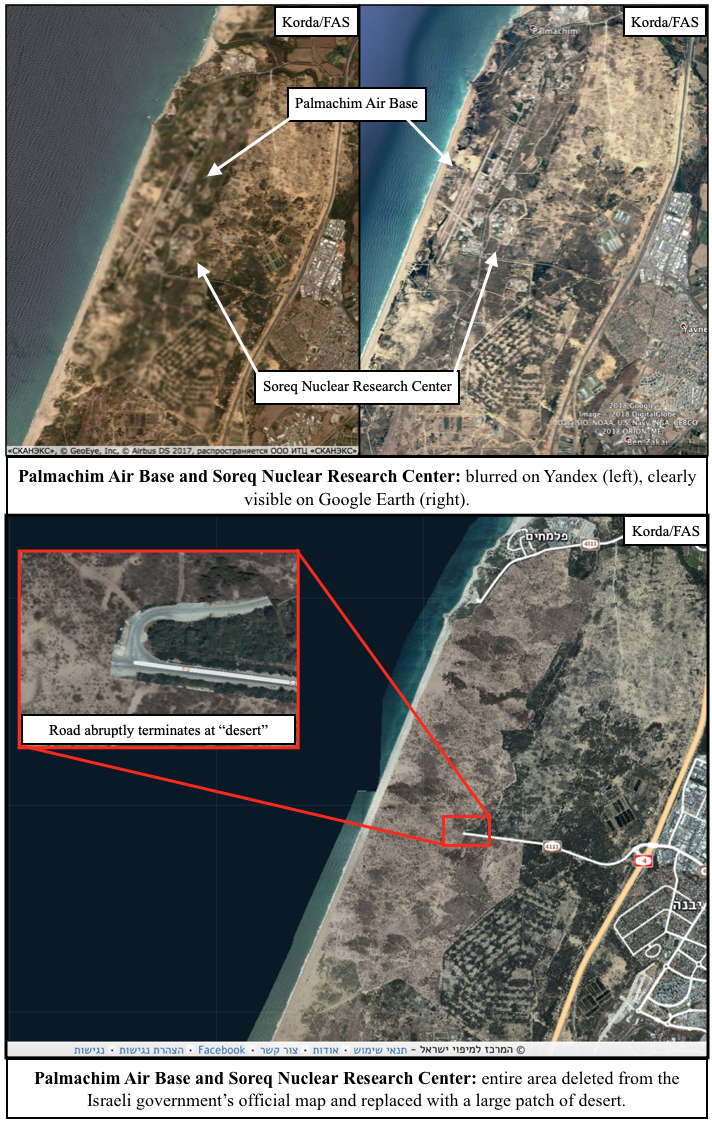

- Palmachim Air Base doubles as a test launch site for Jericho missiles and is collocated with the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, which is rumoured to be responsible for nuclear weapons research and design. The entire area has been replaced with a fake desert.

- The Haifa Naval Base includes pens for submarines that are rumoured to be nuclear-capable, and is entirely blacked out on the official map.

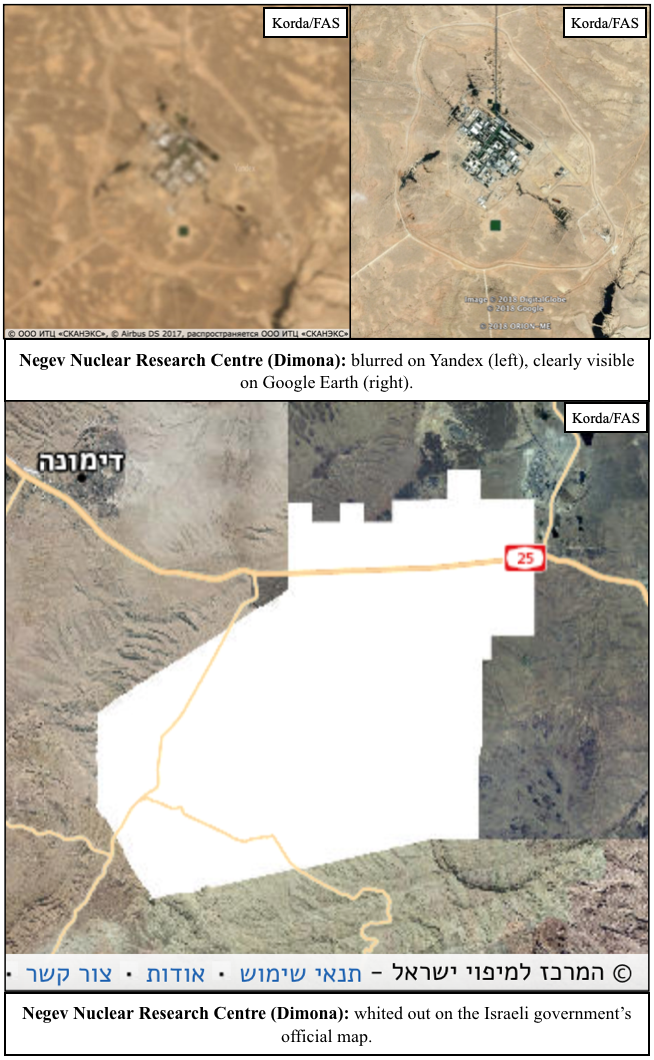

- The Negev Nuclear Research Center at Dimona is responsible for plutonium and tritium production for Israel’s nuclear weapons program, and has been entirely whited out on the official map.

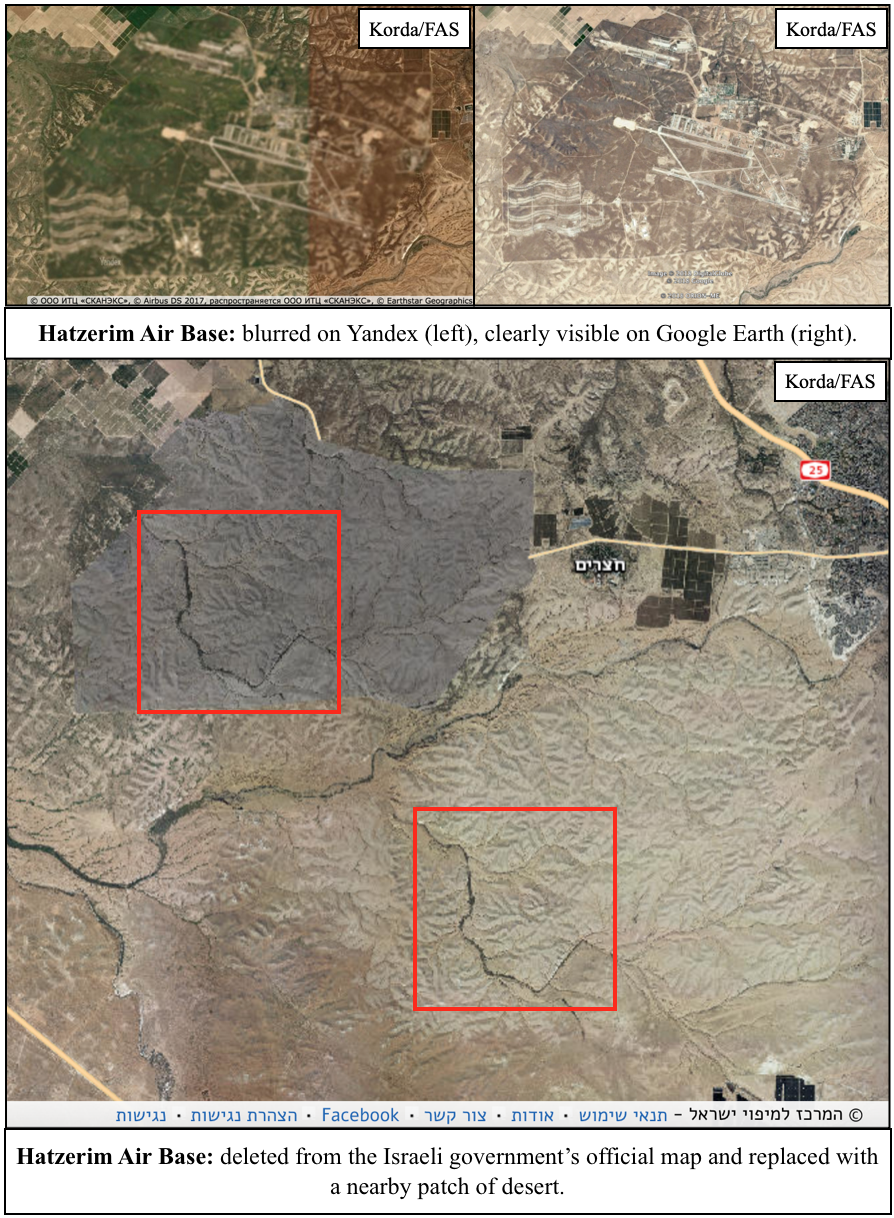

- Hatzerim Air Base has no known connection to Israel’s nuclear weapons program; however, the sloppy method that was used to mask its existence (by basically just copy-pasting a highly-distinctive and differently-coloured patch of desert to an area only five kilometres away) was too good to leave out.

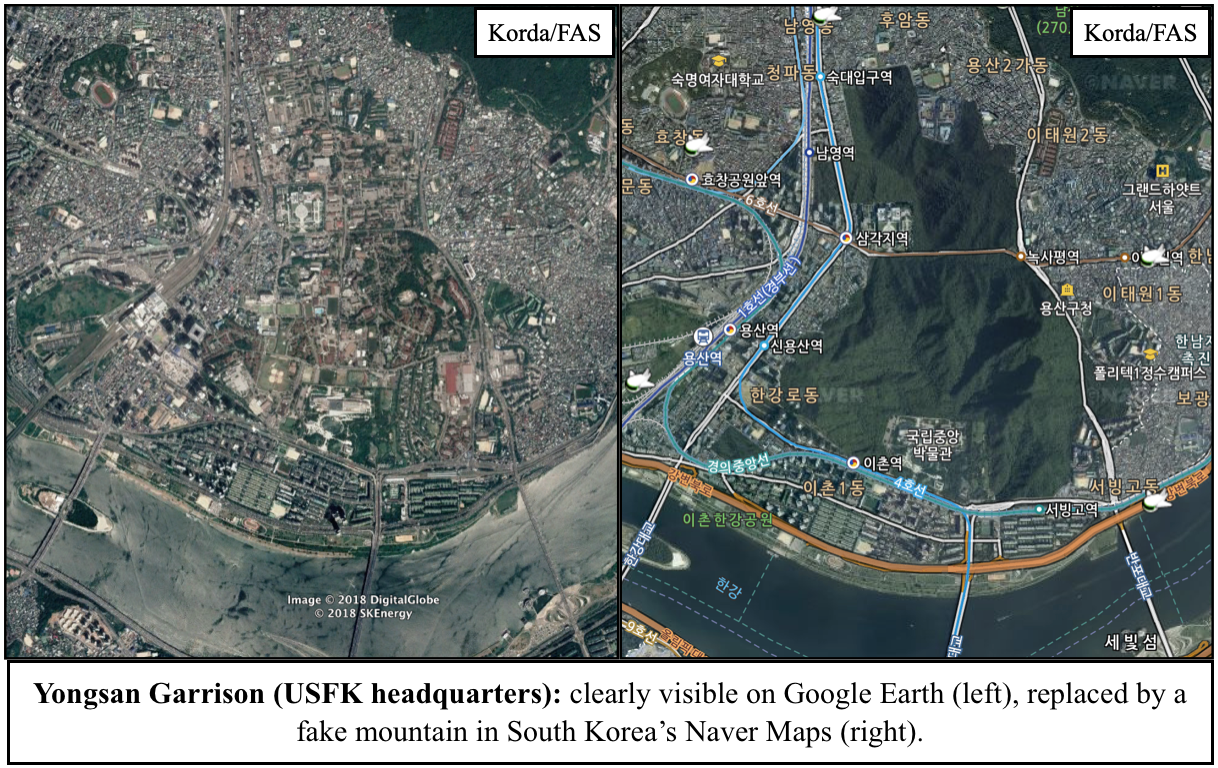

Given that all of these locations are easily visible through Google Earth and other mapping platforms, Israel’s official map is a prime example of needless censorship. But Israel isn’t the only one guilty of silly secrecy: South Korea’s Naver Maps regularly paints over sensitive sites with fake mountains or digital trees, and in a particularly egregious case, the Belgian Ministry of Defense is actually suing Google for not complying with its requests to blur out its military facilities.

Before the proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery, obscuring aerial photos of military facilities was certainly an effective method for states to safeguard their sensitive data. However, now that anyone with an internet connection can freely access these images, it simply makes no sense to persist with these unnecessary censorship practices–especially since these methods can often backfire and draw attention to the exact sites that they’re supposed to be hiding.

Case studies like Yandex and Strava—in which the locations of secret military facilities were revealed through the publication of fitness heat-maps—should prompt governments to recognize that their data is becoming increasingly accessible through open-source methods. Correspondingly, they should take the relevant steps to secure information that is absolutely critical to national security, and be much more publicly transparent with information that is not—hopefully doing away with needless censorship in the process.

US B-1B bomber assurance missions to Korea

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

By Adam Mount

As the Trump administration has prioritized North Korea, it has expanded military exercises around the peninsula to attempt to coerce the regime and assure US allies in Seoul and Tokyo. Perhaps the most dependable signal has been B-1B bombers missions to allied airspace. Though the flights were staged regularly during the Obama administration, they have become more frequent over the last year and more assertive. A review of official press releases and public reporting places this week’s flight of a conventional B-1B bomber near the Korean peninsula as the thirteenth of 2017.

The B-1B bomber originally entered service in 1986 as a supersonic nuclear bomber intended to serve as an interim step between the aging B-52 and the stealthy B-2. The B-1B’s nuclear mission was eliminated in 1994, after which the Air Force did not expend money to maintain its nuclear certification. To meet its obligations under the START treaties, the B-1B was converted to a conventional only platform by welding a metal sleeve onto the aircraft to prevent installation of cruise missile pylons and by removing cable connections in the weapon bays necessary to arm nuclear munitions. As part of New START, Russian observers inspected these modifications in 2011 and accepted the bomber as nonnuclear.

Though effectively nonnuclear, the regional perception of the B-1B is more nuanced. South Korea regularly refers to these flights as demonstrating “strategic assets,” a term usually applied to nuclear-capable platforms. By allowing the term to refer to the intercontinental range of the aircraft in this context, the United States mollifies South Korean officials who desire frequent signals of the US nuclear commitment without devaluing their nuclear signaling options.

Perceptions of the flights are additionally complicated by the fact that North Korea regularly refers to the B-1B as a nuclear platform. For example, North Korea decried this week’s flight a “nuclear strike drill.” Whether they do so for propaganda purposes or genuinely believe the aircraft is nuclear-capable is not clear, but defense strategists must consider the possibility that Pyongyang perceives a nuclear signal, even if the US officials did not intend to send one. What is clear is that the B-1B flights are of particular concern for Pyongyang. In August, 2017, state propaganda agency KCNA described “the operational plan for making an enveloping fire at the areas around Guam” by firing four Hwasong-12 IRBMs as a way of “containing” B-1B flights. The threat was an early attempt to brandish North Korea’s new long-range missiles in an attempt to coerce the US-South Korea alliance to modify its deterrent posture.

The missions are meant to ensure interoperability with allied forces and reassure allies of US defense commitments. US defense observers now widely doubt that the missions have any deterrent value and have instead become essentially routine signals of assurance to South Korea. North Korea now expects that any major test or provocation will elicit a B-1B flight in response. The assurance value of the flights is also an open question. Though ROK officials appreciate the signal, in the wake of the North Korean ICBM and thermonuclear weapons tests, they have also reportedly sought explicit signals of the US nuclear commitment as well as new conventional military signals. As such, the flights now probably have limited value to the alliance and several observers suggest that they could be modified if North Korea proved willing to negotiate tensions reductions measures.

B-1B missions more frequent and more assertive

‘For the first two months of the Trump administration, US Pacific Air Force did not carry out B-1B flights. From March through June, there was one flight per month. Since then, the alliance has conducted two B-1B flights to Korea per month, often in direct response to North Korean missile or nuclear tests. (USAF carried out additional bilateral missions with Japan as well as flights to the South China Sea.)

The most common mission profile has been “sequenced bilateral” missions in which usually two B-1Bs depart Guam, operate with Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fighters near Japan (often near Kyushu), then subsequently with Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) fighters. About half the time, the bombers perform a simulated release of munitions or, as in (July, August, and September) release live or inert munitions onto Pilsung range, South Korea.

In September and October, the Air Force has begun to experiment with provocative new mission profiles. On 30 August, the B-1Bs were escorted for the first time by USMC F-35B aircraft from MCAS Iwakuni, Japan. The combination of the stealth fighter with the low-observable bomber will raise new concerns in Pyongyang about the abilities of their air defenses to detect and aerial intrusions. On 23 September, a B-1B mission for the first time flew Northeast of the Demilitarized Zone in international airspace. According to the US Air Force, North Korean air defenses failed to detect the flight, raising additional concerns about their capabilities.

On 11 October, CNN reported that a sequenced bilateral mission had performed a missile release drill in the East Sea (Sea of Japan), following which the B-1Bs and their ROKAF escorts crossed the peninsula and repeated the drill in the West Sea (Yellow Sea). Though B-1B exercises in the West Sea are not unprecedented, they are highly unusual. Additionally, this is the first known report of a missile release drill. The only missiles carried by the B-1B are the standard and extended-range variants of the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Munition, a long-range conventional cruise missile. Using the unclassified range of 500 miles, the JASSM-ER is capable of striking Chinese territory from most points in the East Sea and all of the West Sea. Beijing can be struck from the western half of the West Sea without flying north of the DMZ. This fact, combined with the proximity of the flight with US-ROK naval exercises in the West Sea around the time of the landmark Chinese Party Congress, suggests that the flight was an assertive signal not only to Pyongyang but also to Beijing.

Escalation risks

Though B-1B sequenced bilateral missions are now essentially routine, several trends raise the risk that these flights could contribute to military escalation.

This year’s B-1B flights occur in a political and military context distinct from previous administration. The Trump administration has through rhetorical comments and assertive military signaling around the peninsula has signaled that they could order military strikes on North Korea. In the last two weeks, the US-ROK combined forces have staged a series of highly provocative exercises ahead of Mr. Trump’s visit to the region (including major live fire naval exercises in the East and West Seas, drills to evacuate US civilians, port visits from American submarines and the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier, and announcements of upcoming deployments of F-35A to Japan and a three-carrier exercise in the Pacific).

Both in exercises and in other announcements, both the United States and South Korea have openly signaled that they are training for decapitation strikes against North Korea’s leadership. The signal is intended to convey to Pyongyang that ordering an attack could place their lives directly at risk and so to deter aggression. Yet, the administration’s rhetorical emphasis on forcible denuclearization of the peninsula may also give the impression that the United States could carry out assassination strikes even absent North Korean aggression. Combined with poor situational awareness of low-observable aircraft, the statements significantly raise North Korea’s incentives to escalate any crisis, the likelihood that they perceive US operations as a prelude to attack, and the risk of nuclear use.

To date, the Trump administration has not conducted a flight of a nuclear-capable B-2 stealth bomber to Korea. In 2013, the Obama administration did carry out a prominent flight from Whiteman AFB, MO to deliver inert munitions at Pilsung, the first and last time a B-2 mission has been disclosed publicly.

However, on 28-29 October, 2017, a B-2 flew from Whiteman to an undisclosed location in the Pacific. The bomber reportedly stopped on Guam, where it swapped crews with the engines running. Though a B-2 flight to Korea is unlikely to be radically destabilizing, in the context of a frequent White House comments playing up the possibility of military action and thinly-veiled nuclear threats to North Korea, planners should be aware that dispatching a B-2 is likely to be significantly more provocative than similar missions in previous years.

In the past, the United States had generally conducted Bomber Assurance and Deterrence (BAAD) flights with B-52 bombers. Because some B-52s are nuclear-capable, these missions were widely interpreted as nuclear deterrent signals. The most recent B-52 flight was in January, 2016, following the fourth DPRK nuclear test. Since 2004, either B-1B, B-52, or B-2 bombers have been rotationally stationed in Guam as part of the “Continuous Bomber Presence” Mission. In 2003, 12 B-52s and 12 B-1B bombers were alerted in the United States and subsequently deployed to Guam after 4 North Korean MiG fighters intercepted an American surveillance plane.

Lastly, the missions may be sending precisely the opposite message from the one intended. For the last several years, the United States has continued to work to improve trilateral coordination between the United States, South Korea, and Japan in order to present North Korea with a united front. However, the sequenced bilateral missions only serve underscore the reticence of the ROKAF and JASDF to operate together. Though JASDF fighters sometimes “hand off” the US bombers to ROK pilots, trilateral missions would send a far stronger signal of cohesion and capability, especially if conducted over ROK airspace.

These considerations raise serious questions about the value of B-1B assurance flights. At a time of rapid advance in North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities, with a US leadership that has made statements exacerbating South Korea’s concerns that the United States could decouple from its allies, it is unlikely that routine and symbolic flights are an effective signal either for deterring Pyongyang or assuring Seoul.