Supporting Federal Decision Making through Participatory Technology Assessment

The incoming administration needs a robust, adaptable and scalable participatory assessment capacity to address complex issues at the intersections of science, technology, and society. As such, the next administration should establish a special unit within the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI)—an existing federally funded research and development center (FFRDC)—to provide evidence-based, just-in-time, and fit-for-purpose capacity for Participatory Technology Assessment (pTA) to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy and across executive branch agencies.

Robust participatory and multi-stakeholder engagement supports responsible decision making where neither science nor existing policy provide clear guidance. pTA is an established and evidence-based process to assess public values, manage sociotechnical uncertainties, integrate living and lived knowledge, and bridge democratic gaps on contested and complex science and society issues. By tapping into broader community expertise and experiences, pTA identifies plausible alternatives and solutions that may be overlooked by experts and advocates.

pTA provides critical and informed public input that is currently missing in technocratic policy- and decision-making processes. Policies and decisions will have greater legitimacy, transparency, and accountability as a result of enhanced use of pTA. When systematically integrated into research and development (R&D) processes, pTA can be used for anticipatory governance—that is, assessing socio-technical futures, engaging communities, stakeholders and publics, and directing decisions, policies, and investments toward desirable outcomes.

A pTA unit within STPI will help build and maintain a shared repository of knowledge and experience of the state of the art and innovative applications across government, and provide pTA as a design, development, implementation, integration and training service for the executive branch regarding emerging scientific and technological issues and questions. By integrating public and expert value assessments, the next administration can ensure that federal science and technology decisions provide the greatest benefit to society.

Challenge and Opportunity

Science and technology (S&T) policy problems always involve issues of public values—such as concerns for safety, prosperity, and justice—alongside issues of fact. However, few systematic and institutional processes meaningfully integrate values from informed public engagement alongside expert consultation. Existing public-engagement mechanisms such as public- comment periods, opinion surveys, and town halls have devolved into little more than “checkbox” exercises. In recent years, transition to online commenting, intended to improve access and participation, have also amplified the negatives. They have “also inadvertently opened the floodgates to mass comment campaigns, misattributed comments, and computer-generated comments, potentially making it harder for agencies to extract the information needed to inform decision making and undermining the legitimacy of the rulemaking process. Many researchers have found that a large percentage of the comments received in mass comment responses are not highly substantive, but rather contain general statements of support or opposition. Commenters are an entirely self selected group, and there is no reason to believe that they are in any way representative of the larger public. … Relatedly, the group of commenters may represent a relatively privileged group, with less advantaged members of the public less likely to engage in this form of political participation.”

Moreover, existing engagement mechanisms tend to be dominated by a small number of experts and organized interest groups: people and institutions who generally have established pathways to influence policy anyway.

Existing engagement mechanisms leave out the voices of people who may lack the time, awareness, and/or resources to voice their opinions in response to the Federal Register, such as the roofer, the hair stylist, or the bus driver. This means that important public values—widely held ideas about the rights and benefits that ought to guide policy making in a democratic system—go overlooked. For S&T policy, a failure to assess and integrate public values may result in lack of R&D and complementary investments that produce market successes with limited public value, such as treatments for cancer that most patients cannot afford or public failure when there is no immediately available technical or market response, such as early stages of a global pandemic. Failure to integrate public values may also mean that little to no attention gets paid to key areas of societal need, such as developing low-cost tools and approaches for mitigating lead and other contaminants in water supplies or designing effective policy response, such as behavioral and logistical actions to contain viral infections and delivering vaccination to resistant populations.

In its 2023 Letter to the President, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), observed that, “As a nation, we must strive to develop public policies that are informed by scientific understandings and community values. Achieving this goal will require both access to accurate and trusted scientific information and the ability to create dialogue and participatory engagement with the American people.” The PCAST letter recommends issuing “a clarion call to Federal agencies to make science and technology communication and public engagement a core component of their mission and strategy.” It also recommended the establishment of “a new office to support Federal agencies in their continuing efforts to develop and build participatory public engagement and effective science and technology communications.”

Institutionalizing pTA within the Federal Government would provide federal agencies access to the tools and resources they need to apply pTA to existing and emerging complex S&T challenges, enabling experts, publics, and decision makers to tackle pressing issues together.pTA can be applied toward resolving long-standing issues, as well as to anticipate and address questions around emerging or novel S&T issues.

pTA for Long-Standing S&T Issues

Storage and siting of disposal sites for nuclear waste is an example of the type of ongoing, intractable problems for which pTA is ideally suited. Billions of dollars have been invested to develop a government-managed site for storing nuclear waste in the United States, yet essentially no progress has been made. Entangled political and environmental concerns, such as the risks of leaving nuclear waste in a potentially unsafe state for the long term, have stalled progress. There is also genuine uncertainty and expert disagreement surrounding safety and efficacy of various storage alternatives. Our nation’s inability to address the issue of nuclear waste has long impacted development of new and alternative nuclear power plants and thus has contributed to the slowing the adoption of nuclear energy.

There are rarely unencumbered or obvious optimal solutions to long-standing S&T issues like nuclear-waste disposal. But a nuanced and informed dialogue among a diverse public, experts, and decision makers—precisely the type of dialogue enabled through pTA—can help break chronic stalemates and address misaligned or nonexistent incentives. By bringing people together to discuss options and to learn about the benefits and risks of different possible solutions, pTA enables stakeholders to better understand each other’s perspectives. Deliberative engagements like pTA often generate empathy, encouraging participants to collaborate and develop recommendations based on shared exploration of values. pTA is designed to facilitate timely, adequate, and pragmatic choices in the context of uncertainty, conflicting goals, and various real-world constraints. This builds transparency and trust across diverse stakeholders while helping move past gridlock.

pTA for Emerging and Novel Issues

pTA is also useful for anticipating controversies and governing emerging S&T challenges, such as the ethical dimensions of gene editing or artificial intelligence or nuclear adoption. pTA helps grow institutional knowledge and expertise about complex topics as well as about public attitudes and concerns salient to those topics at scale. For example, challenges associated with COVID-19 vaccines presented several opportunities to deploy pTA. Public trust of the government’s pandemic response was uneven at best. Many Americans reported specific concerns about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine. Public opinion polls have delivered mixed messages regarding willingness to receive a COVID- 19 vaccine, but polls can overlook other historically significant concerns and socio-political developments in rapidly changing environments. Demands for expediency in vaccine development complicated the situation when normal safeguards and oversights were relaxed. Apparent pressure to deliver a vaccine as soon as possible raised public concern that vaccine safety is not being adequately vetted. Logistical and ethical questions about vaccine rollout were also abound: who should get vaccinated first, at what cost, and alongside what other public health measures? The nation needed a portfolio of differentiated and locally robust strategies for vaccine deployment. pTA would help officials anticipate equity challenges and trust deficits related to vaccine use and inform messaging and means of delivery, helping effective and socially robust rollout strategies for different communities across the country.

pTA is an Established Practice

pTA has a history of use in the European Union and more recently in the United States. Inspired partly by the former U.S. Office of Technology Assessment (OTA), many European nations and the European Parliament operate their own technology assessment (TA) agencies. European TA took a distinctive turn from the OTA in further democratizing science and technology decision-making by developing and implementing a variety of effective and economical practices involving citizen participation (or pTA). Recent European Parliamentary Technology Assessment reports have taken on issues of assistive technologies, future of work, future of mobility, and climate-change innovation.

In the United States, a group of researchers, educators, and policy practitioners established the Expert and Citizen Assessment of Science and Technology (ECAST) network in 2010 to develop a distinctive 21st-century model of TA. Over the course of a decade, ECAST developed an innovative and reflexive participatory technology assessment (pTA) method to support democratic decision-making in different technical, social, and political contexts. After a demonstration project providing citizen input to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity in collaboration with the Danish Board of Technology, ECAST, worked with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on the agency’s Asteroid Initiative. NASA-sponsored pTA activities about asteroid missions revealed important concerns about mitigating asteroid impact alongside decision support for specific NASA missions. Public audiences prioritized a U.S. role in planetary defense from asteroid impacts. These results were communicated to NASA administrators and informed the development of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, demonstrating how pTA can identify novel public concerns to inform decision making.

This NASA pTA paved the way for pTA projects with the Department of Energy on nuclear-waste disposal and with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration on community resilience. ECAST’s portfolio also includes projects on climate intervention research, the future of automated vehicles, gene editing, clean energy demonstration projects and interim storage of spent nuclear fuel. These and other pTA projects have been supported by more than six million dollars of public and philanthropic funding over the past ten years. Strong funding support in recent years highlights a growing demand for public engagement in science and technology decision-making.

However, the current scale of investment in pTA projects is vastly outstripped by the number of agencies and policy decisions that stand to benefit from pTA and are demanding applications for different use cases from public education, policy decisions, public value mapping and process and institutional innovations. ECAST’s capacity and ability to partner with federal agencies is limited and constrained by existing administrative rules and procedures on the federal side and resources and capacity deficiencies and flexibilities on the network side. Any external entity like ECAST will encounter difficulties in building institutional memory and in developing cooperative-agreement mechanisms across agencies with different missions as well as within agencies with different divisions. Integrating public engagement as a standard component of decision making will require aligning the interests of sponsoring agencies, publics, and pTA practitioners within the context of broad and shifting political environments. An FFRDC office dedicated to pTA would provide the embedded infrastructure, staffing, and processes necessary to achieve these challenging tasks. A dedicated home for pTA within the executive branch would also enable systematic research, evaluation, and training related to pTA methods and practices, as well as better integration of pTA tools into decision making involving public education, research, innovation and policy actions.

Plan of Action

The next administration should support and conduct pTA across the Federal Government by expanding the scope of the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) to include a special unit with a separate operating budget dedicated specifically to pTA. STPI is an existing federally funded research and development center (FFRDC) that already conducts research on emerging technological challenges for the Federal Government. STPI is strategically associated with the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Integrating pTA across federal agencies aligns with STPI’s mission to provide technical and analytical support to agency sponsors on the assessment of critical and emerging technologies.

A dedicated pTA unit within STPI would (1) provide expertise and resources to conduct pTA for federal agencies and (2) document and archive broader public expertise captured through pTA. Much publicly valuable knowledge generated from one area of S&T is applicable to and usable in other areas. As part of an FFRDC associated with the executive branch, STPI’s pTA unit could collaborate with universities to help disseminate best practices across all executive agencies.

We envision that STPI’s pTA unit would conduct activities related to the general theory and practice of pTA as well as partner with other federal agencies to integrate pTA into projects large and small. Small-scale projects, such as a series of public focus groups, expert consultations, or general topic research could be conducted directly by the pTA unit’s staff. Larger projects, such as a series of in-person or online deliberative engagements, workshops, and subsequent analysis and evaluation, would require additional funding and support from the requesting agencies. The STPI pTA unit could also establish longer-term partnerships with universities and science centers (as in the ECAST network), thereby enabling the federal government to leverage and learn from pTA exercises sponsored by non-federal entities.

The new STPI pTA unit would be funded in part through projects requested by other federal agencies. An agency would fund the pTA unit to design, plan, conduct, assess, and analyze a pTA effort on a project relevant to the agency. This model would enable the unit to distribute costs across the executive branch and would ensure that the unit has access to subject-matter experts (i.e., agency staff) needed to conduct an informed pTA effort. Housing the unit within STPI would contribute to OSTP’s larger portfolio of science and technology policy analysis, open innovation and citizen science, and a robust civic infrastructure.

Cost and Capacities

Adding a pTA unit to STPI would increase federal capacity to conduct pTA, utilizing existing pathways and budget lines to support additional staff and infrastructure for pTA capabilities. Establishing a semi-independent office for pTA within STPI would make it possible for the executive branch to share support staff and other costs. We anticipate that $3.5–5 million per year would be needed to support the core team of researchers, practitioners, leadership, small-scale projects, and operations within STPI for the pTA unit. This funding would require congressional approval.

The STPI pTA unit and its staff would be dedicated to housing and maintaining a critical infrastructure for pTA projects, including practical know-how, robust relationships with partner organizations (e.g., science centers, museums, or other public venues for hosting deliberative pTA forums), and analytic capabilities. This unit would not wholly be responsible for any given pTA effort. Rather, sponsoring agencies should provide resources and direction to support individual pTA projects.

We expect that the STPI pTA unit would be able to conduct two or three pTA projects per year initially. Capacity and agility of the unit would expand as time went on to meet the growth and demands from the federal agencies. In the fifth year of the unit (the typical length of an FFRDC contract), the presidential administration should consider whether there is sufficient agency demand for pTA—and whether the STPI pTA unit has sufficiently demonstrated proof-of-concept—to merit establishment of a new and independent FFRDC or other government entity fully dedicated to pTA.

Operations

The process for initiating, implementing and finalizing a pTA project would resemble the following:

Pre:

- Agency approaches the pTA unit with interest in conducting pTA for agency assessment and decision making for a particular subject.

- pTA unit assists the agency in developing questions appropriate for pTA. This process involves input from agency decision makers and experts as well as external stakeholders.

- A Memorandum of understanding/agreement (MOU/MOA) is created, laying out the scope of the pTA effort.

During:

- pTA unit and agency convene expert and/or public workshops (as appropriate) to inform pTA activities.

- pTA unit and agency create, test, and evaluate prototype pTA activities (see FAQs below for more details on evaluation).

- pTA unit and agency work with a network of pTA host institutions (e.g, science centers, universities, nonprofit organizations, etc.) to coordinate pTA forums.

- pTA unit oversees pTA forums.

Post:

- pTA unit collects, assesses, and analyzes pTA forum results with iterative input and analysis from the hosting agency.

- pTA unit works with stakeholders to share and finalize pTA reports on the subject, as well as a dissemination plan for sharing results with stakeholder groups.

Conclusion

Participatory Technology Assessment (pTA) is an established suite of tools and processes for eliciting and documenting informed public values and opinions to contribute to decision making around complex issues at the intersections of science, technology, and society.

However, its creative adaptation and innovative use by federal agencies in recent years demonstrate their utility beyond providing decision support: from increasing scientific literacy and social acceptability to diffusing tensions and improving mutual trust. By creating capacity for pTA within STPI, the incoming administration will bolster its ability to address longstanding and emerging issues that lie at the intersection of scientific progress and societal well-being, where progress depends on aligning scientific, market and public values. Such capacity and capabilities will be crucial to improving the legitimacy, transparency, and accountability of decisions regarding how we navigate and tackle the most intractable problems facing our society, now and for years to come.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Experts can help map potential policy and R&D options and their implications. However, there will always be an element of judgment when it comes to deciding among options. This stage is often more driven by ethical and social concerns than by technical assessments. For instance, leaders may need to figure out a fair and just process to govern hazardous-waste disposal, or weigh the implications of using genetically modified organisms to control diseases, or siting clean energy research and demonstration projects in resistant or disadvantaged communities. Involving the public in decision-making can help counter challenges associated with expert judgment (for example, “groupthink”) while bringing in perspectives, values, and considerations that experts may overlook or discount.

pTA incorporates a variety of measures to inform discussion, such as background materials distributed to participants and multimedia tools to provide relevant information about the issue. The content of background materials is developed by experts and stakeholders prior to a pTA event to give the public the information they need to thoughtfully engage with the topic at hand. Evaluation tools, such as those from the informal science-education community, can be used to assess how effective background materials are at preparing the public for an informed discussion, and to identify ineffective materials that may need revision or supplementation. Evaluations of several past pTA efforts have 1) shown consistent learning among public participants and 2) have documented robust processes for the creation, testing, and refinement of pTA activities that foster informed discussions among pTA participants.

pTA can result in products and information, such as reports and data on public values, that are relevant and useful for the communication missions of agencies. However, pTA should avoid becoming a tool for strategic communications or a procedural “checkbox” activity for public engagement. Locating the Federal Government’s dedicated pTA unit within an FFRDC will ensure that pTA is informed by and accountable to a broader community of pTA experts and stakeholders who are independent of any mission agency.

The work of universities, science centers, and nonpartisan think tanks have greatly expanded the tools and approaches available for using pTA to inform decision-making. Many past and current pTA efforts have been driven by such nongovernmental institutions, and have proven agile, collaborative, and low cost. These efforts, while successful, have limited or diffuse ties to federal decision making.

Embedding pTA within the federal government would help agencies overcome the opportunity and time cost of integrating public input into tight decision-making timelines. ECAST’s work with federal agencies has shown the need for a stable bureaucratic infrastructure surrounding pTA at the federal level to build organizational memory, create a federal community of practice, and productively institutionalize pTA into federal decision-making.

Importantly, pTA is a nonpartisan method that can help reduce tensions and find shared values. Involving a diversity of perspectives through pTA engagements can help stakeholders move beyond impasse and conflict. pTA engagements emphasize recruiting and involving Americans from all walks of life, including those historically excluded from policymaking.

Currently, the Government Accountability Office’s Science, Technology Assessment, and Analytics team (STAA) conducts technology assessments for Congress. Technology Assessment (TA) is designed to enhance understanding of the implications of new technologies or existing S&T issues. The STAA certainly has the capacity to undertake pTA studies on key S&T issues if and when requested by Congress. However, the distinctive form of pTA developed by ECAST and exemplified in ECAST’s work with NASA, NOAA, and DOE follows a knowledge co- production model in which agency program managers work with pTA practitioners to co-design, co-develop, and integrate pTA into their decision-making processes. STAA, as a component of the legislative branch, is not well positioned to work alongside executive agencies in this way. The proposed pTA unit within STPI would make the proven ECAST model available to all executive agencies, nicely complementing the analytical TA capacity that STAA offers the federal legislature.

Executive orders could support one-off pTA projects and require agencies to conduct pTA. However, establishing a pTA unit within an FFRDC like STPI would provide additional benefits that would lead to a more robust pTA capacity.

FFRDCs are a special class of research institutions owned by the federal government but operated by contractors, including universities, nonprofits, and industrial firms. The primary purpose of FFRDCs is to pursue research and development that cannot be effectively provided by the government or other sectors operating on their own. FFRDCs also enable the government to recruit and retain diverse experts without government hiring and pay constraints, providing the government with a specialized, agile workforce to respond to agency needs and societal challenges.

Creating a pTA unit in an FFRDC would provide an institutional home for general pTA know-how and capacity: a resource that all agencies could tap into. The pTA unit would be staffed by a small but highly-trained staff who are well-versed in the knowledge and practice of pTA. The pTA unit would not preclude individual agencies from undertaking pTA on their own, but would provide a “help center” to help agencies figure out where to start and how to overcome roadblocks. pTA unit staff could also offer workshops and other opportunities to help train personnel in other agencies on ways to incorporate the public perspective into their activities.

Other potential homes for a dedicated federal pTA unit include the Government Accountability Office (GAO) or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. However, GAO’s association with Congress would weaken the unit’s connections to agencies. The National Academies historically conduct assessments driven purely by expert consensus, which may compromise the ability of National Academies-hosted pTA to include and/or emphasize broader public values.

Evaluating a pTA effort means answering four questions:

First, did the pTA effort engage a diverse public not otherwise engaged in S&T policy formulation? pTA practitioners generally do not seek statistically representative samples of participants (unlike, for instance, practitioners of mass opinion polling). Instead, pTA practitioners focus on including a diverse group of participants, with particular attention paid to groups who are generally not engaged in S&T policy formulation.

Second, was the pTA process informed and deliberative? This question is generally answered through strategies borrowed from the informal science-learning community, such as “pre- and post-“ surveys of self-reported learning. Qualitative analysis of the participant responses and discussions can evaluate if and how background information was used in pTA exercises. Involving decision makers and stakeholders in the evaluation process—for example, through sharing initial evaluation results—helps build the credibility of participant responses, particularly when decision makers or agencies are skeptical of the ability of lay citizens to provide informed opinions.

Third, did pTA generate useful and actionable outputs for the agency and, if applicable, stakeholders? pTA practitioners use qualitative tools for assessing public opinions and values alongside quantitative tools, such as surveys. A combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis helps to evaluate not just what public participants prefer regarding a given issue but why they hold that preference and how they justify those preferences. To ensure such information is useful to agencies and decision makers, pTA practitioners involve decision makers at various points in the analysis process (for example, to probe participant responses regarding a particular concern). Interviews with decision makers and other stakeholders can also assess the utility of pTA results.

Fourth, what impact did pTA have on participants, decisions and decision-making processes, decision makers, and organizational culture? This question can be answered through interviews with decision makers and stakeholders, surveys of pTA participants, and impact assessments.

Evaluation of a pTA unit within an existing FFRDC would likely involve similar questions as above: questions focused on the impact of the unit on decisions, decision-making processes, and the culture and attitudes of agency staff who worked with the pTA unit. An external evaluator, such as the Government Accountability Office or the National Academies of Sciences, could be tasked with carrying out such an evaluation.

pTA results and processes should typically be made public as long as few risks are posed to pTA participants (in line with federal regulations protecting research participants). Publishing results and processes ensures that stakeholders, other members of government (e.g., Congress), and broader audiences can view and interpret the public values explored during a pTA effort. Further, making results and processes publicly available serves as a form of accountability, ensuring that pTA efforts are high quality.

How Policy Entrepreneurs Can Seize the Presidential Transition Opportunity

The United States is heading into a critical period of political transition. In a climate of uncertainty, it’s tempting to step back and wait to see how the presidential transition will unfold—but this is exactly when changemakers need to press forward. Policy entrepreneurs have a unique opportunity to shape the agenda for the next administration. Knowing when and how to act is crucial to turning policy ideas into action.

Through the Day One 2025 initiative FAS has engaged with more than 100 policy entrepreneurs across the country to produce policy ideas for the next administration. In the coming weeks we will be rolling out policy memos that focus on five core areas: energy and environment, government capacity, R&D, innovation and competitiveness, global security, and emerging technologies and artificial intelligence. The initial intellectual work has been developed between FAS and its network of experts, but the broader process of policy entrepreneurship has just begun. To seize this policy window, here are five things policy entrepreneurs should consider as we enter the presidential transition:

1. Timing is everything: when a policy window opens, those who recognize the opening will be the ones shaping the conversation

Policy-making is often about timing. Success in advancing a novel idea or solution often depends on aligning policy proposals with favorable political, social, economic conditions, and taking advantage of the right policy window. These opportunities might come and go based on shifts in public opinion, crises, or leadership changes. Policy entrepreneurs who are ready to act when these windows present themselves are more likely to advance their policy ideas and shape the conversation. Historically, the first 100 days of a new presidency is going to be a crucial period for passing major legislation, as the new administration’s political capital is typically at its highest. For policy entrepreneurs, this means now is the time to position your ideas, build coalitions, and make your voice heard. Preparing early and being ready to seize this window can make the difference between a policy idea gaining traction or being left behind in the political shuffle.

2. Preparation is key: have your policy ideas ready to go

When an opportunity arises and transition teams invite your ideas, you won’t have the luxury of time to think up a brand new policy idea. For policy entrepreneurs to capitalize on the opportunity, it’s crucial to have a solid policy proposal on hand. Preparation involves more than just having a concept, it means supporting your policy idea with data, research, and a clear implementation strategy. Policymakers are looking for solutions that are both innovative and practical, so the more detail you can provide, the better positioned you’ll be to influence decision-making. Having a policy idea prepared in advance – perhaps with contingencies to reposition its appeal – allows you to adapt quickly to changing circumstances or emerging priorities.

3. Be versatile: frame policy proposals in ways that resonate with a diverse audience regardless of political leaning

To effectively advocate for policy proposals, it’s essential to tailor your messaging to resonate with diverse political audiences. Whether it’s job growth, economic efficiency, or social equity—thinking about how your policy proposal appeals to different values, increases the chance of building broad support across the political spectrum. A great way to pressure test your framing is by engaging with stakeholders from various backgrounds who can provide valuable insights into how your policy might be perceived by different audiences. Similarly, be creative in identifying outlets that your idea could be folded into if pursuing it as a standalone policy isn’t feasible. There are opportunities for ‘quick wins’ if you can have your idea incorporated into a bill or report that is required to be produced annually, mold it into something that is relevant to anticipated geopolitical challenges, or apply it to issues where movement is certain in 2025, such as artificial intelligence.

4. Understand the potential impact of your policy proposal: who will this impact?

As you develop your policy idea, think about who and what communities will be impacted and how. This means identifying the specific communities, industries, or demographic groups that will feel the immediate and long-term effects, both positively and negatively. Think about how the policy will address their needs or challenges, and whether any unintended consequences might arise. Will it benefit marginalized or underserved populations, or will it place unintended burdens on particular groups? Engaging with stakeholders throughout the policy development process is extremely crucial to understand the practical benefits and potential blindspots.

5. Iterate, iterate, iterate: policy entrepreneurship is an ongoing process

The journey of shaping effective policies is not a linear path but rather an iterative process that requires ongoing refinement and adaptation. Being receptive to feedback and criticism strengthens your policy idea. Successful policy entrepreneurs proactively build relationships, and stay attuned to the shifting political climate. Ultimately, embracing the iterative nature of policy entrepreneurship not only strengthens your proposals but also builds your credibility and resilience as a changemaker. By committing to ongoing learning, relationship-building, and adaptive strategies, you can navigate the complexities of policymaking more effectively and increase your chances of making a lasting impact.

There has never been a better time than now for people across demographics to engage in policy entrepreneurship. Make sure to keep an eye out on the policy memos that will be rolling out over the next several weeks and do not hesitate to submit your novel policy ideas through our Day One Project Open Call platform.

A Guide to Public Deliberation

Science is advancing at an unprecedented speed, and scientists are facing major ethical dilemmas daily. Unfortunately, the general public rarely gets opportunities to share their opinions and thoughts on these ethical challenges, moving us, as a society, towards a future that is not inclusive of most people’s ideas and beliefs. Scientists regularly call for public engagement opportunities to discuss cutting-edge research. In fact, “71% of scientists [associated with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)] believe the public has either some or a lot of interest in their specialty area.” Sadly, scientists’ calls often go unnoticed and unanswered, as there continue to be inadequate mechanisms for these engagement opportunities to come to fruition.

To Deliberate or Not to Deliberate

Public deliberation, when performed well, can lead to more transparency, accountability to the public, and the emergence of ideas that would otherwise go unnoticed. Due to the direct involvement of participants from the public, decisions made through such initiatives can also be seen as more legitimate. On a societal level, public deliberation has been shown to encourage pluralism among participants.

Despite the importance of deliberation, it’s important to note that it is not always the best way to engage the public. Planning a public deliberation event — a citizens’ panel, for instance — takes a large amount of time and resources. Plus, incentivizing a random sample of citizens to participate (which is considered the gold standard of deliberation) is difficult. It’s therefore paramount to first assess whether the topic of focus is suitable for public deliberation.

To assess the appropriateness of a deliberation topic, consider the following criteria (inspired by criteria set forth by Stephanie Solomon and Julia Abelson and the Kettering Foundation):

- Does the issue involve conflicting public opinions? Issues that involve setting priorities in healthcare, for example, may benefit from public deliberation as there is no singular correct answer; deliberation may offer a more clear and holistic view of what is best for a community, according to the community.

- Is the issue controversial? If so, deliberation can be a good tool as it brings many opinions into view and can foster pluralism as mentioned previously.

- Does the issue have no clear-cut solution and is “intractable, ongoing, or systemic”?

- Do all available solutions have significant drawbacks?

- Does the community at large have an interest in the problem?

- Would the discussion of the issue benefit from a combination of expert and real-world experience and knowledge (what Solomon and Abelson call “hybrid” topics)? Certain issues may solely require technical knowledge but many issues would benefit from the views of the public as well.1

- Are citizens and the government on the same page about the issue? If not, public deliberation can foster trust, but only if the initiative is done with the intention of taking the public’s conclusions into account.

Setting Goals

If it’s deemed that the topic is suitable for public deliberation, the next step is to set goals for the public deliberation initiative. Julia Abelson, Lead of the Public Engagement in Health Policy Project and Professor at McMaster University, has explained that one of the significant differentiating factors between successful and unsuccessful initiatives is thoughtful planning and organization — including setting clear goals and objectives organizers would like to meet by the end of deliberation. Having an end goal not only helps with planning but also allows for a realistic goal to be shared with deliberation participants. Setting unrealistic expectations as to what the deliberation process is meant to achieve — and subsequently not achieving those goals — will lead participants and citizens, in general, to lose trust in the deliberation process (and organizational body).

Is the goal of deliberation to bring new ideas into view and share those with relevant agencies (governmental or otherwise)? Is the goal instead to enact change in current policies? Is the goal to help shape new policies? The aforementioned Citizens’ Reference Panel on Health Technologies in Canada did not directly impact the government’s decisions, but served to make experts aware of a viewpoint they had not previously explored. This is in contrast to the typical “sit and listen” initiatives that don’t have as much of a capacity to encourage new ideas to emerge. In another instance, a citizens’ jury in Buckinghamshire, England was formed to discuss how to tackle back pain in the county. The Buckinghamshire Health Authority promised to implement the citizens’ recommendations (as was mandated by a charity that was supporting this public deliberation effort) — and they did.

Expanding on the idea of making promises and accountability, it’s important for the organizing body — which may or may not include a federal agency — to consider its role in implementing the conclusions of the deliberation. Promising to implement the conclusion of the deliberations can serve to invigorate discussion and make participants more engaged, knowing that their discussions can have a direct impact on future decisions. For instance, the British Columbia Biobank Deliberation involved a “commitment at the outset of the deliberation from the leaders of a proposed BC BioLibrary (now funded by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research) that the Bio-Library’s policy discussions would consider suggestions from this deliberation.” Researchers have suggested this may have contributed to participants’ interest in the deliberation event. Despite some examples of implementation following deliberation (such as the Buckinghamshire and Ontario examples), there continues to be a lack of adequate change based on the public’s recommendations. One other instance comes from NASA’s 2014 efforts to involve the public in the discussion around planetary defense (in the context of asteroids) through a participatory technology assessment (PTA). It seems that the PTA helped to spur the creation of NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

Furthermore, providing updates on implementation to participants, and the public at large, would provide another crucial aspect of accountability: “explanations and justifications.” However, these updates on their own would not fulfill an organization or agency’s duty to accountability as that requires an active dialogue with the public (which is precisely why implementing the conclusions of public deliberation initiatives is important).

When to Deliberate: Agenda Setting for Citizens

As mentioned above, deliberation can happen at various points during the policymaking pipeline. It has become increasingly popular to include the public early on in the process, such as in an agenda-setting role. This allows the public not only to engage in discussions about a topic but to also set the priorities and frame how the discussions will move forward. As Naomi Scheinerman writes, “with proper agenda setting and precedent creation, the resulting […] questions would be more reflective of what the public is interested in discussing rather than of the companies, industries, and other stakeholder groups.”

A trailblazing model in citizen agenda-setting has been the Ostbelgien Model. The model involves both a permanent Citizens’ Council and ad hoc Citizens’ Panels. Though the members of the Citizens’ Council rotate (and are chosen randomly), one of the permanent roles of the Council is to select topics for the ad hoc Citizens’ Panels, with citizens having a direct hand in what issues their fellow citizens and government should tackle. Since its inception in 2019, the Citizens’ Council has asked Citizens’ Panels to tackle issues such as “how to improve the working conditions of healthcare workers” and “inclusive education.”

Framing

One of the pillars of the success of public deliberation is a well-scoped question that is framed appropriately. Issues that are framed unfairly, meaning they place emphasis on a specific part of the issue while ignoring others, can lead to inaccurate results and a loss of trust between the public and the organizers. Though this depends on the goals of the deliberation, it’s often best for questions to be specific in their scope to allow for concrete results at the end of the deliberation initiative. For example, an online deliberation session in New York City aimed to assess the public’s views on who should be given priority access to COVID-19 vaccines. One of the questions asked participants to rank the order in which they think a pre-specified list of essential workers should get access to the vaccine. This allows for discussion while retaining a clear focus.

Another example comes from climate change. Climate change can be framed in many ways — through an economic frame, a public health frame, a justice frame, and others. These various framings impact how the public reacts to the issue; in the case of the economic frame, it has led to “political divisiveness.” Focusing instead on the public health frame, for instance, led to greater agreement on policy decisions. Similarly, according to a 2023 policy paper from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an issue like COVID-19 can be less polarizing if the framing used is about solutions to the pandemic rather than solely vaccines. Importantly, the organizers of the public deliberation initiative do not have sole control over the framing of the issue. Citizens often have a pre-existing “frame of thought.” This makes frames tricky yet essential in making it possible to appropriately and productively deliberate a topic.

Framing is implicit in that participants in deliberation are not aware of it, making it all the more crucial to be wary of the framing. Thus, it becomes clear how seemingly unimportant factors, such as setting, also affect deliberation. According to Mauro Barisione, the framing of the setting includes:

- Who is promoting the event and who the sponsors are: Whether the public trusts the promoters/sponsors and the feelings they associate with them (including any explicit views the sponsors promote) may impact the framing of the topic at hand.

- Where is/are the deliberative session(s) being held “(i.e., institutional, academic, civil society or business organization, etc.)”: Apart from accessibility concerns, the location of the deliberative session(s) sends implicit messages to participants who may have previously had negative experiences at governmental institutions, for instance.

- Who are the witnesses and experts brought on as part of the project: This point is most obvious. Especially when it comes to less well-known topics, witnesses and experts may be the first window into a new topic for participants. A biased selection of experts (or including experts who provide unscientific evidence) can significantly impact deliberation. Moreover, an oft-neglected point worth considering is the diversity of expert witnesses who present relevant information at public deliberation events. Selecting experts is discussed in more detail in a later section, but it’s worth noting here that a diverse group of expert presenters will ensure a diversity of views and may aid in building trust with participants as well.

Selecting a Type of Public Deliberation

Another factor that merits attention at this point is the type of public deliberation being undertaken. Though public deliberation has been referred to as one entity thus far, there are many different types, including, but not limited to, citizens’ juries, planning cells, consensus conferences, citizens’ assemblies, and deliberative polls. Below are some further details about various types of public deliberation (where a source is not included below, it was adapted from Smith & Setälä).

Citizens’ juries

- Description: “In common with the legal jury, citizens’ jury assumes that a small group of ordinary people, without special training, is willing and able to take important decisions in the public interest” (Coote & Mattinson)

- Selected jurists are meant to represent a microcosm of their community (Crosby)

- Jurors are selected through a quota process that often takes into account demographics (e.g., age, gender, education and race) or jurors’ prior opinions about the question at hand (Crosby)

- Neutral moderator moderates discussions (Crosby)

- Jurors are able to determine what questions are asked of the witnesses

- Similar to planning cells (below), jurors are paid for the time (e.g., $75 per day)

- Number of participants: 12–24

- Time: 2-4 days (Armour)

- Output: Jurors put together a written report of their conclusions (Armour)

- Examples: Ned Crosby of the independent Jefferson Institute in the US initially ran them with groups of 12-24 people (Smith & Wales)

- Another example is the Oregon Citizens’ Initiative Review

Planning cells

- Description: Deliberation includes 3 phases (Participedia):

- Citizens are presented with pertinent information from multiple perspectives and ask clarifying questions

- Cells are broken up into smaller groups of 5 and work together to come up with recommendations regarding the topic

- The full cell reconvenes and each mini group presents their top recommendation, which is then assessed by all members of the group, until some final recommendations are made

- Number of participants: 25 in each cell (multiple cells running simultaneously or one after another); often have 6-10 planning cells total (Dienel)

- Time: 3-4 days (Dienel)

- Each day is split into four chunks of time, each spent on a different “thematic focus”

- The final day is used to summarize the participants’ thoughts and come to conclusions (Planning Cells Database)

- Output: Citizens’ report

- Created by the planning committee based on quantitative data aggregated from all the cells (for instance, from how participants responded to which option they favored) (Dienel)

- The first draft of the report may also be discussed with participants in a follow-up meeting

- Example: Cologne Town Square

Consensus conferences/citizens’ conferences

- Description: These conferences have been described as a citizens’ jury plus a town hall meeting (Einsiedel & Eastlick)

- Citizens learn some basic facts about the issue at hand and formulate questions they’d like addressed (Kenyon). In other words, the topic is chosen by the organizers while the concrete problems are selected by the citizens (Nielsen et al.).

- Witnesses are called to answer these questions (Kenyon) and the experts are selected entirely by citizens (Nielsen et al.)

- A steering group is often involved who ensures that “the conference is balanced and just” and provides support to the organizers (Nielsen et al.)

- Members include “scientists, representatives of non-governmental organizations, policy-makers and others, who are engaged and informed concerning the topic”

- It’s recommended that fact sheets be prepared that explain basic definitions necessary for understanding the topic as well as pros and cons for all sides — this will be provided to participants in preparation for discussions and the questioning of expert witnesses (Nielsen et al.)

- Introductory materials should also clearly explain the role of the consensus conference participants and how their contributions will be used to inform future decisions

- Number of participants: 10-24

- Time: 4 days

- Output: Report written by citizen participants (Kenyon)

- Example: Danish Board of Technology consensus conferences

Citizens’ assemblies

- Description: Typically larger and longer than the deliberative processes discussed above, similar to legislatures composed of regular citizens (Lacelle-Webster & Warren)

- Organizers often aim to make assemblies as representative of the public as possible through methods like stratified random sampling (Lacelle-Webster & Warren)

- More limited participation opportunities so some suggest that it’s better to call citizens’ assemblies “representative institutions” rather than a form of participatory democracy (Lacelle-Webster & Warren)

- Participants compensated for their time (Ferejohn)

- Based on the initial citizens’ assembly in British Columbia, any interested expert witnesses or groups were able to testify in front of the participants (Ferejohn)

- Participants can ask any questions of the witnesses (Ferejohn)

- A Chair — who was the only public official directly involved in the process — is able to make obligatory rulings as to how the deliberations would proceed

- Organizers set the agenda

- Formats can vary: the inaugural 2004 British Columbia citizens’ assembly was more so in the format of a legislature as opposed to an Irish citizens’ assembly which included roundtable discussions with groups of 7-8 participants alongside a facilitator and notetaker at each table (Farrell et al.)

- Number of participants: 99-150

- Time: Meetings over several months (often during weekends) (Farrell et al.)

- Output: Report and recommendations from citizens’ assembly (Ferejohn)

- Example: The 2004 British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly

Deliberative polls

- Description: Combines traditional polling with the benefits of participatory processes

- Randomly selected participants are polled on their opinions about a topic (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- Participants receive introductory materials about the issue prior to the event (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- A weekend-long event where participants learn more about the issues from experts (ask questions from experts) and discuss issues with one another with trained facilitators present (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- At the end, complete the questionnaire from earlier once more (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- Participants often paid for their time ($75-$200) (Participedia)

- Number of participants: 200+

- Time: One weekend (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- Output: Differences measured between the opinions of participants pre- and post-deliberative polling process (Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab)

- Example: 2008 deliberative poll on housing shortages in San Mateo County, California

A note on online deliberation

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many initiatives to shift to a fully online modality. This highlighted many of the opportunities as well as challenges that online deliberation presents. One consideration is accessibility, a double-edged sword when it comes to deliberation. Virtual deliberation alleviates the need for a venue or hotel accommodations — decreasing costs for organizers — and may allow participants to continue to go to work at the same time. However, difficulties with using technology and a lack of access to a device or an internet connection are drawbacks. Another opportunity presented by virtual deliberation is to provide more balanced viewpoints on the topic of deliberation. For instance, there are no geographical barriers as to the experts organizers can invite to speak at an event.

A concern somewhat unique to online deliberation is data privacy and security. While this can also be an issue with in-person initiatives, many tools that participants are familiar with and may prefer to use do not have robust security.

A note on cost

While the cost of many deliberation initiatives is not publicly available, the available estimates range from $20,000 (citizens’ jury) to $95,000 (consensus conference) to $2.6 million (Europe-wide deliberative poll of 4300 people) to $5.5 million (citizens’ assembly). Note that these costs come from a range of time points and locations (though they have been adjusted for inflation) and only serve as rough estimates. A major contributor to these costs, particularly for longer deliberative initiatives, is hotel or venue costs as well as the reimbursement of participants. This reimbursement is costly but a part of the founding philosophy of many types of deliberation, including that of planning cells.

Selecting Participants

Many different approaches can be taken to selecting participants for deliberative forums. Unfortunately, there are inherent trade-offs in selecting a sampling method or approach. For instance, random sampling is more in line with the principle of “equal opportunity” and may promote “cognitive diversity”— the diversity of ideas, experiences, and approaches participants bring to the event — but is prone to creating deliberation groups that are not representative of the population at large. This is particularly true when the deliberative forum has few participants. This is why, depending on the type of deliberation event (and therefore number of participants chosen), a different type of sampling may be appropriate.

Another approach is random-stratified sampling, where participants are randomly chosen and invited to participate in the deliberative event. There is often an unequal distribution among those who accept the invitation — for instance, individuals with higher socio-economic statuses may respond disproportionately more. In this case, a more representative sample may be chosen from those who responded. Quotas may also be set, such as ensuring that a certain number of female-identifying participants are included in a deliberative event. For this method, the organizers must decide on groups of individuals who are primarily affected by the topic being discussed, as well as groups often excluded from such deliberations. A deliberative forum on immigration, for instance, may call for the presence of a participant who is an immigrant to ensure polarization does not take place. In certain instances, purposive sampling — where individuals from groups whose views are specifically being sought are purposefully chosen — may also be appropriate. Furthermore, some researchers suggest including a “critical mass” of individuals from typically underserved groups. This can serve to make participants more comfortable in speaking up, ensure that the diversity of discussions is retained when participants are broken up into smaller groups (in certain forms of public deliberation), and provide a step in avoiding tokenism.

Furthermore, there are newer methods of selecting participants that combine both random and stratified sampling — namely algorithms that try to maximize both representation and equal opportunity of participation. One instance is the LEXIMIN algorithm which “choose[s] representative panels while selecting individuals with probabilities as close to equal as mathematically possible.” This algorithm is open-access and can be used at panelot.org.

Aside from considerations for selecting participants, it’s important to consider the selected individuals’ ability and willingness to participate. Several factors can dissuade selected individuals from taking part, including but not limited to, the cost of missing work, the cost of childcare, transportation costs, and lack of trust in the organizing body or agency. Prohibitive costs are addressed by several of the deliberation models discussed in the “Selecting a Type of Public Deliberation” section. These models strongly suggest stipends which, at minimum, cover incidental expenses. A lack of trust is a particularly important issue to address as it can hinder the organizer’s ability to reach individuals typically left out of policymaking discussions. One approach to addressing this once again brings us to making — and critically, keeping — promises regarding the implementation of the conclusions of participants. Framing (as discussed in an earlier section) can also contribute to building trust, though, importantly, this is not a gap that can be bridged overnight. A more extensive discussion on inclusion in public deliberation forums can be found here.

Bringing On Experts & Creating Materials

Prior to selecting the group who will participate in the public deliberation activity, steps need to be taken to organize which experts will be part of the event and create the informational material that will be provided to participants before deliberations begin.

Here, efforts must be made to ensure sufficient and balanced information is presented without creating a framing event where participants enter discussions with a biased perspective. It has been found that participants readily integrate the facts and opinions presented by experts/witnesses prior to deliberation and critically engage with their points. A deliberative engagement initiative in British Columbia, Canada about biobanking brought on a variety of experts and stakeholders to present to participants. To ensure fairness, presenters were “given specific topics, limited presentation times, and asked to use terms as defined in the information booklet” that was previously provided. A unique component included in this initiative was the ability for participants to ask presenters questions in between the two deliberative session weekends, which were two weeks apart, through a website.

In addition, participants were provided with booklets and readings. In the case of the British Columbia initiative, to create booklets and background materials, a literature review was performed. Once more, the materials should provide a balance of opinions. They should include the most important facts relevant to the question at hand, some of the most common/salient approaches and points with regards to the question, and the weaknesses of each approach/point (Mauro Barisione). It is also best to keep materials succinct, with some deliberative initiatives keeping their materials to one page long.

Though the traditional approach is to have experts present prior to deliberation, other methods have also been used. For instance, a Colorado deliberation initiative focused on future water supply used an “on tap but not on top” expert approach. Rather than call experts to present information, they instead provided one-page information sheets, followed directly by deliberation. Experts were present during the deliberation session. When prompted by a participant, a facilitator would ask an expert to briefly join the group to answer the participant’s question. The approach was largely successful, though one “rogue expert” frequently interjected in a group’s discussion, providing his own opinions. One limiting factor to this approach is time; the deliberative sessions mentioned above were two hours long. But many other forms of deliberation are significantly longer, making coordinating with experts for long durations of time difficult. Despite these challenges, this approach provides an interesting way of integrating experts into the deliberation process so their expertise is best used and the participants’ questions are best answered as they arise.

Facilitation

A good facilitator or moderator is critical to the deliberation process. As explained by Kara N. Dillard, moderators set the ground rules for the discussion and prevent any one participant from dominating the session; this is called presentation. It has been found that clearly setting expectations for the discussion can lead to greater deliberative functioning — which, for our purposes, includes the exchange of ideas/reasons, equality, and freedom to speak and be heard — according to participants. Moderators also guide the discussion in two main ways: asking questions that challenge what participants have already discussed (elicitation); and connecting ideas that were previously brought up to new topics and “play[ing] devil’s advocate” to bring forth new ideas (interpretation). At the end of the session, moderators also help participants produce conclusions by asking what areas of consensus and contention were present throughout the discussion.

Moderators can take multiple approaches to facilitating, with one framework proposed by Kara N. Dillard separating moderators into three groups: passive, moderate, and involved. Passive moderators take a “backseat” approach to moderating. They often describe their role to participants as only being there to prevent a participant from dominating the conversation, rather than actively leading it. This has led to unfocused discussions and unclear conclusions. Participants often jumped around and went off-topic. Though this passive approach may work in some instances, a moderate or involved approach often leads to better deliberation.

Involved facilitators actively lead the discussion by asking questions that challenge participants to think in new ways, sometimes acting as a “quasi-participant.” In line with this, these moderators often play devil’s advocate to move the discussion in new, albeit related, directions. These moderators ask follow-up questions and “editorialize” to help participants flesh out their ideas together and aim to pinpoint points of contention so participants can further discuss them. If participants begin to veer off-topic, involved moderators will move the group back into a more focused direction while also connecting this new topic to the main question, allowing for new thoughts to emerge. These moderators take the time to sum up the main points brought up by participants after each point so conclusions become clear. Once more, this approach may not work in all instances but often leads to deeper conversations and more focused conclusions.

As implied by the name, moderate facilitators are somewhere in between passive and involved facilitators. These moderators ask questions to guide the discussion, but don’t often challenge the participants and let them take the wheel. These moderators use the elicitation strategy frequently, an important difference between moderate and passive moderators.

Due to the skills needed to facilitate a deliberation event well, organizers or government agencies looking to organize these events may require would-be facilitators to undergo brief training.

What Comes Next

After deliberation has taken place, the next step is to write a report summarizing the conclusions of the deliberative forum. As we have seen several times with other topics, there are multiple approaches to this. One approach is to leave the report writing to the facilitators, organizers, or researchers who use their own takeaways from the deliberation (in the case of facilitators) or summarize based on recordings or transcripts (in the case of organizers or researchers). However, this method introduces bias into the process and doesn’t allow participants to be directly involved in creating conclusions or next steps.

An alternative is to allocate time towards coming up with conclusions together with participants both throughout and at the end of the deliberative session. Recall that involved facilitators frequently summarize the conclusions of the group throughout the deliberation, making this final task both more efficient and more participant-led. Participants can directly and immediately add on to or push back against the facilitator’s summary. As a guideline, Public Agenda, an organization conducting public engagement research, divides the summary into the following sections: areas of agreement, areas of disagreement, questions requiring further research, and high-priority action steps.

Big Issues for Science Policy in a Challenging World: A Conversation with Dr. Alondra Nelson

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) seeks to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress. In recognition of her work in public service, FAS will honor Dr. Alondra Nelson with the Public Service Award next month alongside other distinguished figures including Senators Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and Todd Young (R-IN) for their work in Congress making the CHIPS & Science Act a reality to ensure a better future for our nation.

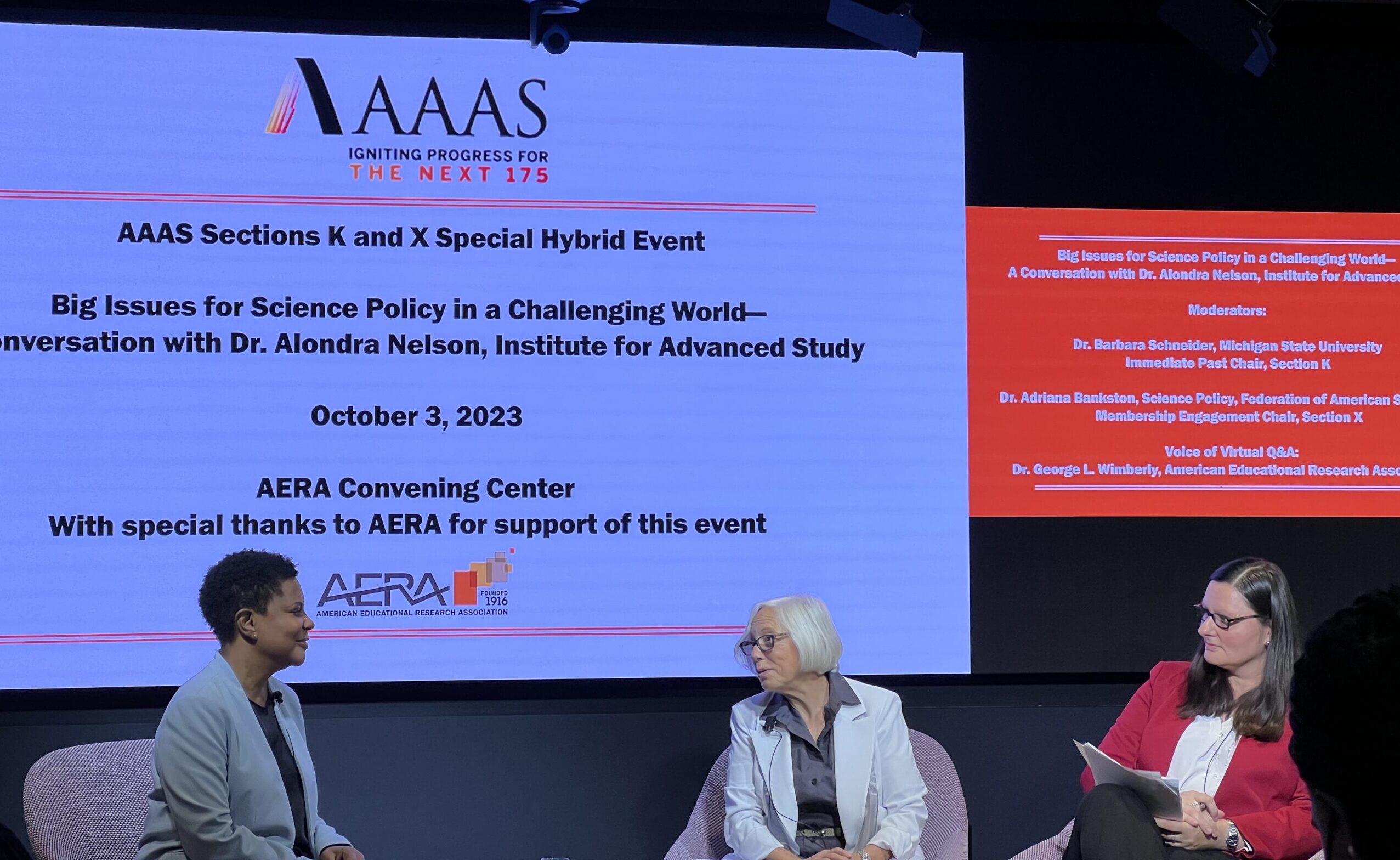

In addition to my role as Senior Fellow in Science Policy for FAS, I have the pleasure of chairing Membership Engagement for Section X, a governance committee of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) focused on Societal Impacts of Science and Engineering. I had the honor of co-moderating a session featuring Dr. Alondra Nelson last week, titled Big Issues for Science Policy in a Challenging World—A Conversation with Dr. Alondra Nelson at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) in Washington D.C.

The hybrid event was co-organized with Section K (Social, Economic, and Political Sciences) and co-moderated with Dr. Barbara Schneider, John A. Hannah University Distinguished Professor in the College of Education and the Department of Sociology at Michigan State University and Immediate Past Chair of AAAS Section K. We led a targeted Q&A discussion informed by audience questions in-person and online.

The conversation focused on how scientific and technical expertise can have a seat at the policymaking table, which aligns with the mission of FAS, and provided key insights from an established leader. Opening remarks featured reflections from Dr. Alondra Nelson on the current state of key issues in science policy that were priorities during her time in the Biden-Harris administration, and her views on the landscape of challenges that should occupy our attention in science policy today and in the future. Dr. Alondra Nelson is the Harold F. Linder Professor at the Institute for Advanced Study and a distinguished senior fellow at the Center for American Progress. A former deputy assistant to President Joe Biden, she served as acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) and the first ever Deputy Director for Science and Society.

FAS is highly invested in ensuring that federal government spending is directed towards enhancing our nation’s competitiveness in science and technology. Dr. Nelson emphasized the idea of innovation for a purpose, and how scientific research and technology development have the potential to improve society, including through STEM education and the infrastructure necessary for research investments to be successful. She also discussed how science and technology can advance democratic values, and highlighted three examples from her time at OSTP that provide promise for the future, including: the cancer moonshot; expanding access to federally funded research across the country; and the need for bringing new voices into science and technology.

Public trust in science and public engagement. The moderated discussion began with the idea of public trust in science in order to set the stage for the current policy landscape. We are operating in a low trust environment for science, and we should make scientific data more accessible to the public. She also highlighted that we need to engage the public in the design process of science and technology, which is why the OSTP Division of Science and Society was initially created. On this point, Dr. Nelson also said that “science policy is a space of possibility” and that we need to expand these opportunities more widely.

FAS Science Policy Fellow Adriana Bankston in conversation with Alondra Nelson at the American Educational Research Association.

Scientific workforce, federal investments and international collaboration. Dr. Nelson described the need to make the implementation of CHIPS and Science a reality and to bring more young voices into science and technology. She remarked that the promise of the CHIPS and Science Act is the intention around investments, and that “we need the ‘and science’ part to be fully funded in order to support the future scientific workforce.” To the question of how we should target federal investments in science and technology, she emphasized the need for collaborative research, bipartisan opportunities, and continuing to study the ‘science of science’ in order to understand the best ways for improving the system, while recognizing that the ROI from the investments we make today may take a few generations to be evident. Relatedly, on the question of ensuring our nation’s competitiveness in science and technology while fostering international collaboration, Dr. Nelson reminded the audience that “national security is a concern around many STEM areas of research.”

Including marginalized voices and technological development. A significant part of the conversation focused on ensuring that marginalized voices have a seat at the table in science and technology. Dr. Nelson stated bluntly that “you can’t have good science without diversity” and that we need to support institutions across the country and engage with different types of educational institutions that may have been traditionally marginalized. To this end, as an example, she emphasized that OSTP previously engaged indigenous knowledge in its work around science and technology governance. The field of artificial intelligence (AI) was also discussed as an example of an area where we need to elevate the visibility of ethical issues that marginalized communities face. The CHIPS and Science Act focused on key technology areas that could create jobs in fields such as AI, leading to a discussion on the need for better policy around emerging technologies, creating high quality jobs, and a stronger focus on workers in the innovation economy.

The event concluded with a high level discussion on policy impact, to which Dr. Nelson remarked that “if you want your science to have an impact, you should find ways to elevate the visibility of your findings among policymakers.” She stated that this will necessitate expanding our current methods to include broader voices in science and technology in the future. We look forward to honoring Dr. Nelson’s impact in the field during next month’s FAS event.

Government Shutdowns Are ‘Science Shutdowns’

Government shutdowns are “Science Shutdowns” – a wildly expensive and ineffective tactic that slows or stops scientific progress at the expense of everyday Americans.

Agencies are busy preparing contingency plans for a government shutdown as Congress spars for political points. FAS would like to draw attention to the danger and absurdity of this tactic as it relates to science, as well as our nation’s safety, competitiveness, and cost burden.

There are four (4) primary results of any government shutdown, and each affect science, which is why we refer to government shutdowns as “Science Shutdowns”:

1. Ongoing Experiments / Activities Requiring Ongoing Observation are Disrupted.

This isn’t just an aggravation to researchers; stoppage destroys work underway at considerable costs to the public. Some examples:

The Department of Commerce will cease operational activity related to most research activities at the National Institute of Standards and Technology.

During a shutdown, researcher access to certain federally funded user facilities and scientific infrastructure can be restricted. When this happens, it can mean lost experiments, disrupted projects, and missed opportunities for students and U.S. industry. (See: FAS work in Social Innovation, specifically STEM Education and Education R&D.)

The Department of Energy’s nuclear verification work––particularly work involving international partnerships––is likely to be restricted. This could have implications for U.S. leadership on non-proliferation, arms control, and risk reduction. (While Nuclear weapons deployments, security, and transportation operations would be largely unaffected due to national security exemptions and funding contingencies, this is still a dangerous situation. See: FAS’s work in Nuclear Weapons.)

2. New initiatives can’t continue (or begin).

Science and technology undergird a large percentage of entrepreneurial startups and economic clusters across the country. Stopping or slowing these businesses impact local communities of all sizes, in every state.

One example: Functionally all SBA (Small Business Administration) lending activity and program support will cease. Small businesses across the country will lose access to this critical source of financing. SBA lending is used to finance growth, but also (critically) to provide working capital for small businesses. Government shutdowns delay Tech Hubs and Engines Type 2 funding, disrupting ecosystem building efforts across the country (See: FAS work in Ecosystems and Entrepreneurship).

3. Funding Decisions are Halted and Delayed.

Shutdowns can mean funding agencies like the National Science Foundation and National Institute of Health (NIH) must furlough most of their staff. This results in delays and rescheduling of review panels, the people responsible for evaluating the effectiveness of a new medicine, for example. Stoppages ultimately delay award decisions and slow advances.

Such delays can affect thousands of American researchers and students and disrupt vital research in many crucial areas. One example limited by a shutdown pause is emerging research in the bioeconomy, a growing part of our global competitiveness. (See: FAS work in Science Policy and bioeconomy, specifically.)

4. Upgrades, Repairs, and Modernization of National Research Infrastructure at Labs and Universities are Frozen.

Labs across the country are continuously upgrading facilities to leverage the latest technology to remain competitive and secure. A government shutdown arrests this necessary work.

Bottom line: A government shutdown is a science shutdown; the decision to pull the plug on government funding incur steep costs on wind-down and re-start, and leads to massive general waste and disruption. We must work together to find resolutions that do not involve holding science hostage during a government shutdown.

Opening Up Scientific Enterprise to Public Participation

This article was written as part of the Future of Open Science Policy project, a partnership between the Federation of American Scientists, the Center for Open Science, and the Wilson Center. This project aims to crowdsource innovative policy proposals that chart a course for the next decade of federal open science. To read the other articles in the series, and to submit a policy idea of your own, please visit the project page.