Widespread Blurring of Satellite Images Reveals Secret Facilities

Want to know how to make a satellite imagery analyst instantly curious about something?

Blur it out.

Google Earth occasionally does this at the request of governments that want to keep prying eyes away from some of their more sensitive military or political sites. France, for example, has asked Google to obscure all imagery of its prisons after a French gangster successfully conducted a Hollywood-inspired jailbreak involving drones, smoke bombs, and a stolen helicopter(!)—and Google has agreed to comply by the end of 2018. In similar fashion, an old Dutch law requires Dutch companies to blur their satellite images of military and royal facilities—even to the point where a satellite imagery provider once doctored an image of Volkel Air Base after it was purchased by FAS’ very own Hans Kristensen.

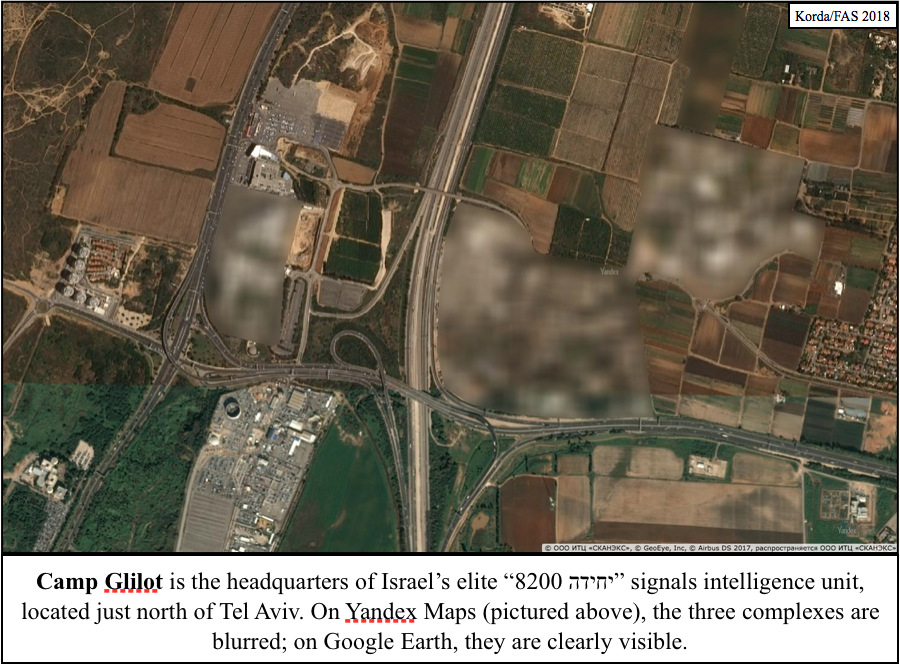

Yandex Maps—Russia’s foremost mapping service—has also agreed to selectively blur out specific sites beyond recognition; however, it has done so for just two countries: Israel and Turkey. The areas of these blurred sites range from large complexes—such as airfields or munitions storage bunkers—to small, nondescript buildings within city blocks.

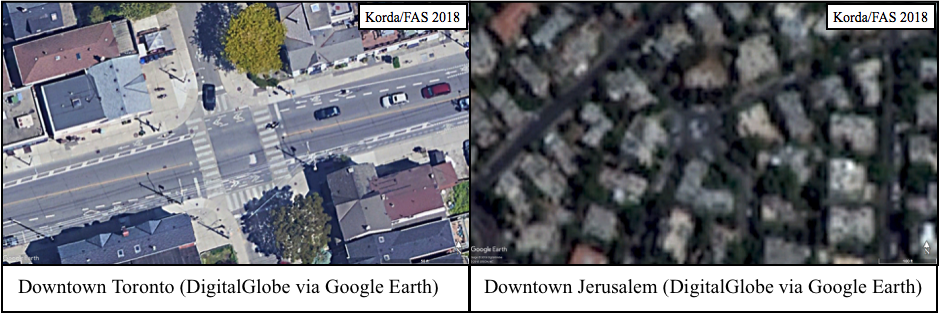

Although blurring out specific sites is certainly unusual, it is not uncommon for satellite imagery companies to downgrade the resolution of certain sets of imagery before releasing them to viewing platforms like Yandex or Google Earth; in fact, if you trawl around the globe using these platforms, you’ll notice that different locations will be rendered in a variety of resolutions. Downtown Toronto, for example, is always visible at an extremely high resolution; looking closely, you can spot my bike parked outside my old apartment. By contrast, imagery of downtown Jerusalem is always significantly blurrier; you can just barely make out cars parked on the side of the road.

As I explained in my previous piece about geolocating Israeli Patriot batteries, a 1997 US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA) prohibits US companies from publishing satellite imagery of Israel at a Ground Sampling Distance lower than what is commercially available. This generally means that US-based satellite companies like DigitalGlobe and viewing platforms like Google Earth won’t publish any images of Israel that are better than 2m resolution.

Foreign mapping services like Russia’s Yandex are legally not subject to the KBA, but they tend to stick to the 2m resolution rule regardless, likely for two reasons. Firstly, after 20 years the KBA standard has become somewhat institutionalized within the satellite imagery industry. And secondly, Russian companies (and the Russian state) are surely wary of doing anything to sour Russia’s critical relationship with Israel.

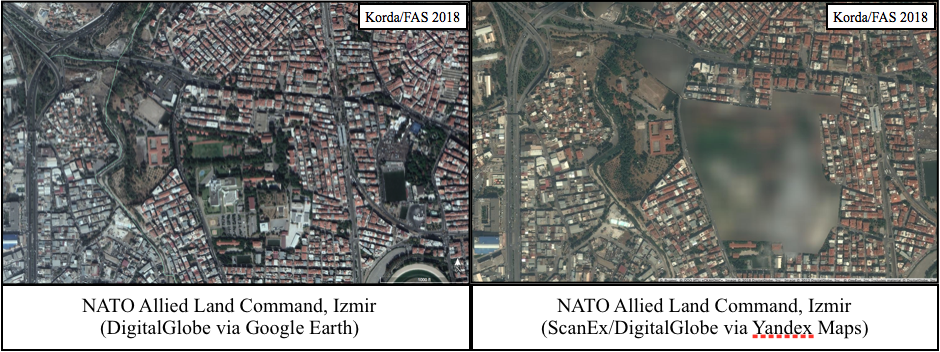

However, Yandex has taken a step well beyond simply downgrading its Israeli imagery, as is typical for most mapping services. Yandex itself—or perhaps its imagery provider ScanEx—has blurred out specific military installations in their entirety. Interestingly, it has done the same to Turkey, a country that benefits from no special standards and is therefore almost always shown in very high resolution.

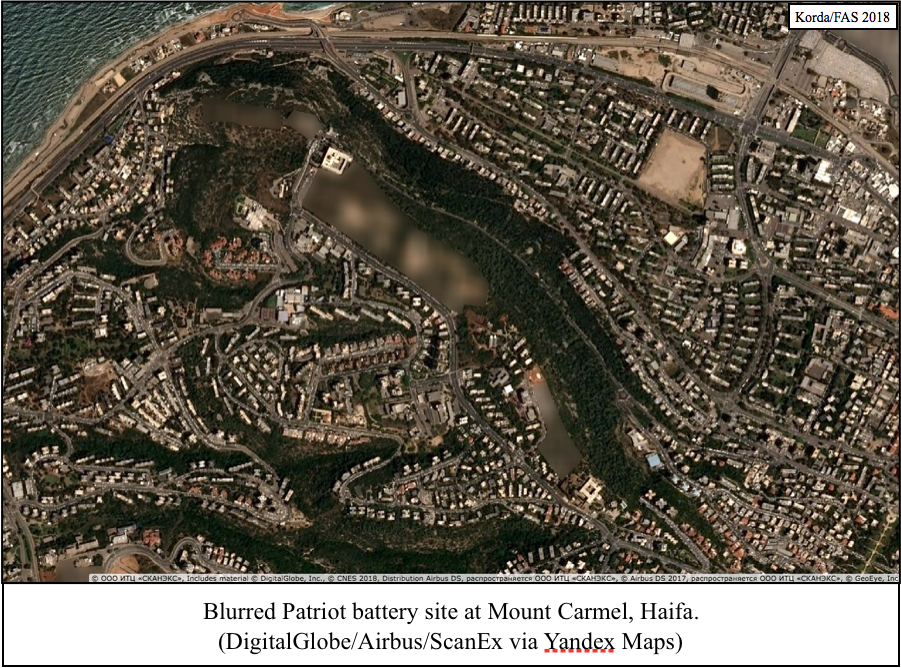

This blurring is almost certainly the result of requests from both Israel and Turkey; it seems highly unlikely that a Russian company would undertake such a time-consuming task of its own volition. Fortunately (from an OSINT perspective), this has had the unintended effect of revealing the location and exact perimeter of every significant military facility within both countries, if one is obsessive curious enough to sift through the entire map looking for blurry patches. Matching the blurred sites to un-blurred (albeit downgraded) imagery available through Google Earth is a method of “tipping and cueing,” in which one dataset is used to inform a more detailed analysis of a second dataset.

My complete list of blurred sites in both Israel and Turkey totals over 300 distinct buildings, airfields, ports, bunkers, storage sites, bases, barracks, nuclear facilities, and random buildings—prompting several intriguing points of consideration:

- Included in the list of Yandex’s blurred sites are at least two NATO facilities: Allied Land Command (LANDCOM) in Izmir, and Incirlik Air Base, which hosts the largest contingent of US B61 nuclear gravity bombs at any single NATO base.

- Strangely, no Russian facilities have been blurred—including its nuclear facilities, submarine bases, air bases, launch sites, or numerous foreign military bases in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, or the Middle East.

- Although none of Russia’s permanent military installations in Syria have been blurred, almost the entirety of Syria is depicted in extremely low resolution, making it nearly impossible to utilize Yandex for analyses of Syrian imagery. By contrast, both Crimea and the entire Donbass region are visible at very high resolutions, so this blurring standard applies only selectively to Russia’s foreign adventures.

- All four Israeli Patriot batteries that I identified using radar interference in my previous post have been blurred out, confirming that these sites do indeed have a military function.

Putting aside the geopolitical intrigue of Russia’s relations with both Israel and Turkey, Yandex’s actions are a prime example of what is known as the Streisand Effect. In 2003, Barbra Streisand attempted to sue a photographer who posted photos of her Malibu mansion online, claiming $10 million in damages and demanding that the innocuous photo be taken down. Her actions completely backfired: not only did Streisand lose the case and have to cover the defendant’s legal fees, but the attention raised by her lawsuit directed significant traffic to the photo in question. Before the lawsuit, the photo had only been viewed six times (including twice by Streisand’s lawyers); a month later, the photo had accumulated over 420,000 views—a prime example of how attempting to obscure something is actually likely to result in unwanted attention.

So too with Yandex. By complying with requests to selectively obscure military facilities, the mapping service has actually revealed their precise locations, perimeters, and potential function to anyone curious enough to find them all.

New START Numbers Show Importance of Extending Treaty

By Hans M. Kristensen

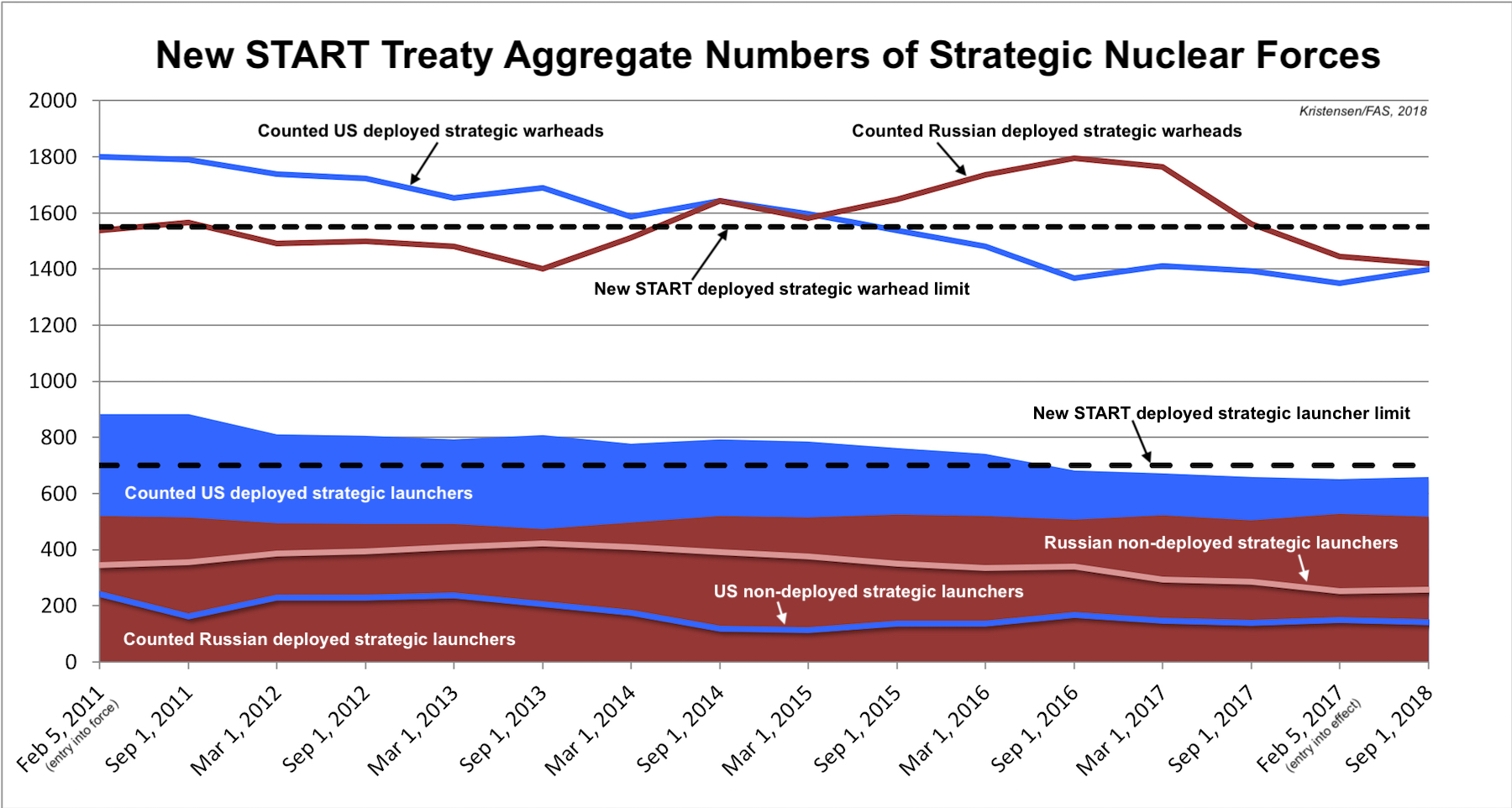

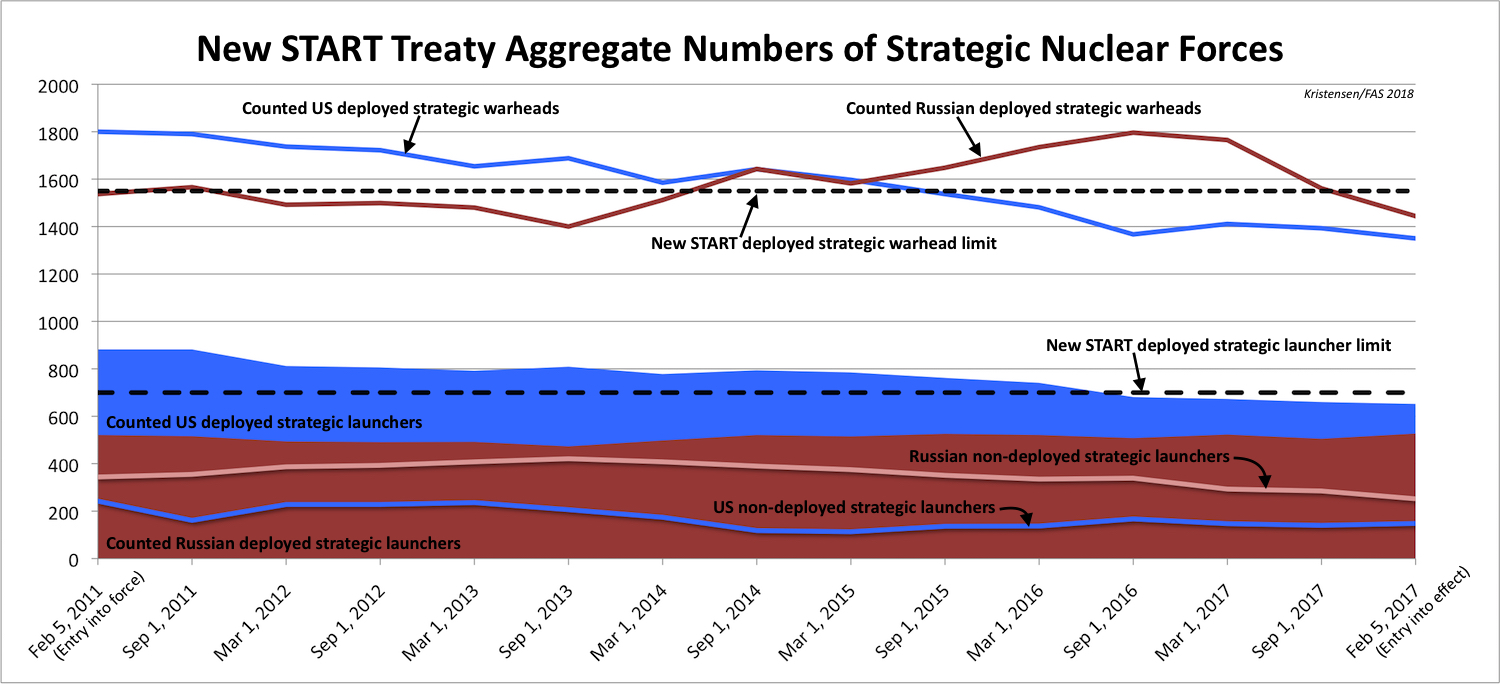

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers published by the State Department earlier today show a slight increase in U.S. deployed strategic forces and a slight decrease in Russian deployed strategic forces over the past six months.

The data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 1, 2018 combined deployed a total of 1,176 strategic launchers with 2,818 attributed warheads. In addition, the two countries also had a total of 399 non-deployed launchers for a total of 1,576 strategic launchers.

Combined, the two countries have reduced their deployed strategic forces by 227 launchers and 519 warheads since 2011.

The warheads counted by the New START treaty are only a portion of the total warhead numbers possessed by the two countries. The Russian military stockpile includes an estimated 4,350 warheads while the United States has about 3,800.

The release of the data comes at a particular important time when the United States and Russia are considering whether to extend the New START treaty for another five years beyond 2021 when it expires. The treaty is under attack from defense hawks in Congress and the Trump administration is weighing whether to extend New START in light of Russia’s alleged violation of other agreements.

The data reaffirms that Russia, despite its modernization program, is not increasing its strategic nuclear forces but continue to limit them in compliance with the limitations of New START. In our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia forces, we estimate that the New START limits recently caused Russia to reduce the number of warheads deployed on several of its strategic missiles.

Deployed Warheads

The data shows that the United States as of September 1 deployed 1,398 warheads on its strategic launchers. This is an increase of 48 warheads since February. Since 2011, the United States has offloaded 402 attributed warheads from its force.

The 1,398 is not the actual number of warheads deployed because bombers are artificially attributed one weapon each even though they don’t carry any weapons in peacetime. The actual number of deployed warheads is closer to 1,350.

Russia was counted with 1,420 deployed strategic warheads, a reduction of 24 warheads from February, and a total of 117 attributed warheads offloaded since 2011. Russian bombers also do not carry weapons so the Russian number is probably closer to 1,370 deployed strategic warheads.

These changes don’t reflect one country building up and the other reducing its forces, but are caused by fluctuations when launchers move in and out of maintenance or old launchers are retired or new ones added.

Deployed Launchers

The data shows the United States deployed 659 strategic launchers, an increase of 7 since February, and a total reduction of 223 launchers since 2011.

Russia deployed 517 strategic launchers, 142 fewer than the United States. That is 10 launchers less than in February, and a total reduction of 4 launchers since 2011.

Non-Deployed Launchers

The data also shows how many non-deployed launchers the two countries have. These are either empty launchers that are in reserve or overhaul or have not yet been destroyed.

The United States had 141 non-deployed launchers, which included empty ICBM silos, bombers in overhaul, and empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul or refit. Since 2011, the United States has destroyed 101 non-deployed launchers.

Russia was counted with 258 non-deployed launchers. This includes empty ICBM silos, empty missile tubes on SSBNs in overhaul, and bombers in overhaul. Since 2011, Russia has destroyed 86 non-deployed launchers.

Essential Verification In Troubled Times

The treaty includes an important verification system that requires the United States and Russia to exchange vast amounts of data about the numbers and operations of their strategic forces and allows them to inspect each other’s facilities.

Since the treaty entered into effect in 2011, the two countries have exchanged 16,444 notifications about launcher movements and telemetry data; 1,603 since February this year.

Data released by the State Department shows that U.S. and Russian inspectors have conducted a total of 277 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic forces and facilities since the treaty entered into force in 2011. So far this year, U.S. officials have inspected Russian facilities 13 times compared with 12 Russian inspections of U.S. facilities.

The combined effects of limiting deployed strategic forces and the verification activities requiring professional collaboration between U.S. and Russian officials, mean that the New START treaty has become a beacon of light in the otherwise troubled relations between Russia and the United States, far more so than anyone could have predicted in 2010 when the treaty was signed.

Other background information:

- Russia nuclear forces, 2018

- US nuclear forces, 2018

- Status of world nuclear forces, 2018

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian ICBM Upgrade at Kozelsk

By Hans M. Kristensen

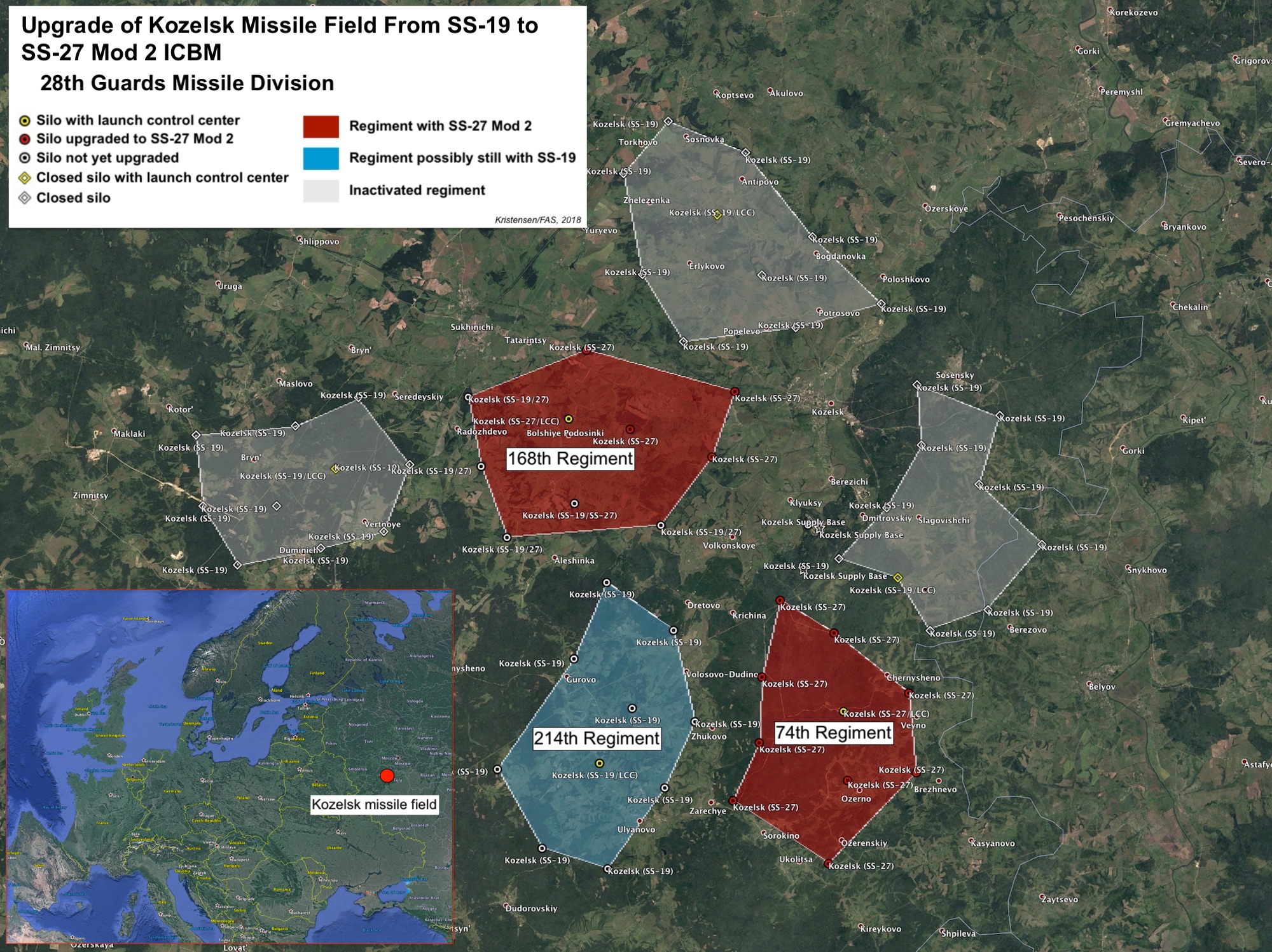

New satellite photos show substantial upgrades of ICBM silos at the missile field near Kozelsk in western Russia.

The images show that progress is well underway on at least half of the silos (possibly more) of the second regiment of the 28th Guards Missile Division from the Soviet-era SS-19 ICBM to the new SS-27 Mod (RS-24, Yars). The first regiment of ten silos completed its upgrade in late-2015. Like the SS-19, the SS-27 Mod 2 carries MIRV.

In its earlier configuration of six regiments with a total of 60 silos, the Kozelsk missile field covered an area of roughly 2,300 square-kilometers (890 square-miles). With closure of three regiments, the active field has been reduced to about 400 square-miles. That includes one 10-missile regiment (74th Regiment) that has already been upgraded to SS-27 Mod 2, a second that is being upgraded (168th Regiment), and a third (219th Regiment) that might still operate SS-19s, although the status is uncertain. It is possible that Russia will upgrade a total of 30 silos at Kozelsk. The Kozelsk missile field is located about 240 kilometers (150 miles) southwest of Moscow about 180 kilometers (115 miles) from Belarus (see image below).

Each SS-27 Mod 2 ICBM can carry up to four MIRV warheads, each with a yield of about 500 kilotons. Each SS-19 carried up to six MIRV, each with a yield of about 400 kilotons. The New START treaty apparently has forced Russia to reduce warhead loading on some of its missiles.

The latest image from Digital Globe on Google Earth is from June 22, 2018. It shows the large launch control center covering 335,000 square-meters (3,620,000 square-feet) with reconstruction nearly completed of the inner area with silo and underground command center. The administrational and technical area has been significantly expanded. A new gun turret is under construction and multi-layered security perimeter has been nearly completed around entire area (see image below).

Approximately 5 kilometers (2.8 miles) southeast of the launch control center, upgrade is underway on another of the 10 silos of the regiment. Comparison with an earlier photo from 2002 clearly shows the extensive upgrade, which is expanding the overall size of the facility to 136,000 square-meters (1,500,000 square-feet). Visible work includes a nearly finished silo, a new gun turret, trenches for new cables, and a new security perimeter (see image below).

Approximately 7 kilometers further southeast, another silo is being upgraded. This silo covers a slightly smaller are of 120,000 square-meters (1,300,000 square-meters). The upgrade appears to be less advanced with substantial work still going on in the silo, the gun turret not yet completed, no cable trenches visible yet, and the security perimeter only partially done. Visible in this area, however, is a unique entrance feature (see image below).

These are just a few facilities of Russia’s extensive land-based nuclear missile force, which has been under upgrade since the late-1990s. The upgrade of Russia’s four ICBM silo missile divisions and seven road-mobile ICBM divisions currently without just over 300 ICBMs is expected to be completed by the mid-2020s. Despite the modernization program, the U.S. Intelligence Community projects “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints,” according to the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center.

For a breakdown of Russian nuclear forces, including locations of its entire land-based missile force, see the FAS Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

To compare Russia’s nuclear forces with those of the world’s other eight nuclear-armed states, go here.

This publication was made possible by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, New Land Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Sanctions on Russia, and More from CRS

The United States has imposed sanctions on Russia in recent years “for aggression against Ukraine, election interference, malicious cyber activity, human rights violations, weapons proliferation,” and other causes. The range of sanctions was surveyed in a new Congressional Research Service publication.

The sanctions include “blocking U.S.-based assets; prohibiting U.S. persons from engaging in transactions related to those assets; prohibiting certain, and in some cases all, U.S. transactions; and denying entry into the United States,” as well as various export control restrictions. See Overview of U.S. Sanctions Regimes on Russia, CRS In Focus, July 26, 2018.

The impact of the punitive sanctions on Russia policy is uncertain. There is no indication that US sanctions were discussed at the recent Helsinki meeting between Trump and Putin, CRS said.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

NAFTA Renegotiation and Modernization, updated July 26, 2018

Momentum Toward Peace Talks in Afghanistan?, CRS Insight, July 24, 2018

The European Union and China, CRS In Focus, July 26, 2018

Australia and New Zealand React to China’s Growing Influence in the South Pacific, CRS Insight, July 26, 2018

Zimbabwe: Forthcoming Elections, CRS In Focus, July 26, 2018

Federal Prize Competitions, July 25, 2018

What Happens If the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) Lapses?, CRS Insight, July 24, 2018

History of Use of U.S. Military Bases to House Immigrants and Refugees, CRS Insight, July 26, 2018

The Essential Judge Brett M. Kavanaugh Reader: What Cases Should You Read?, CRS Legal Sidebar, July 25, 2018

Russia Upgrades Nuclear Weapons Storage Site In Kaliningrad

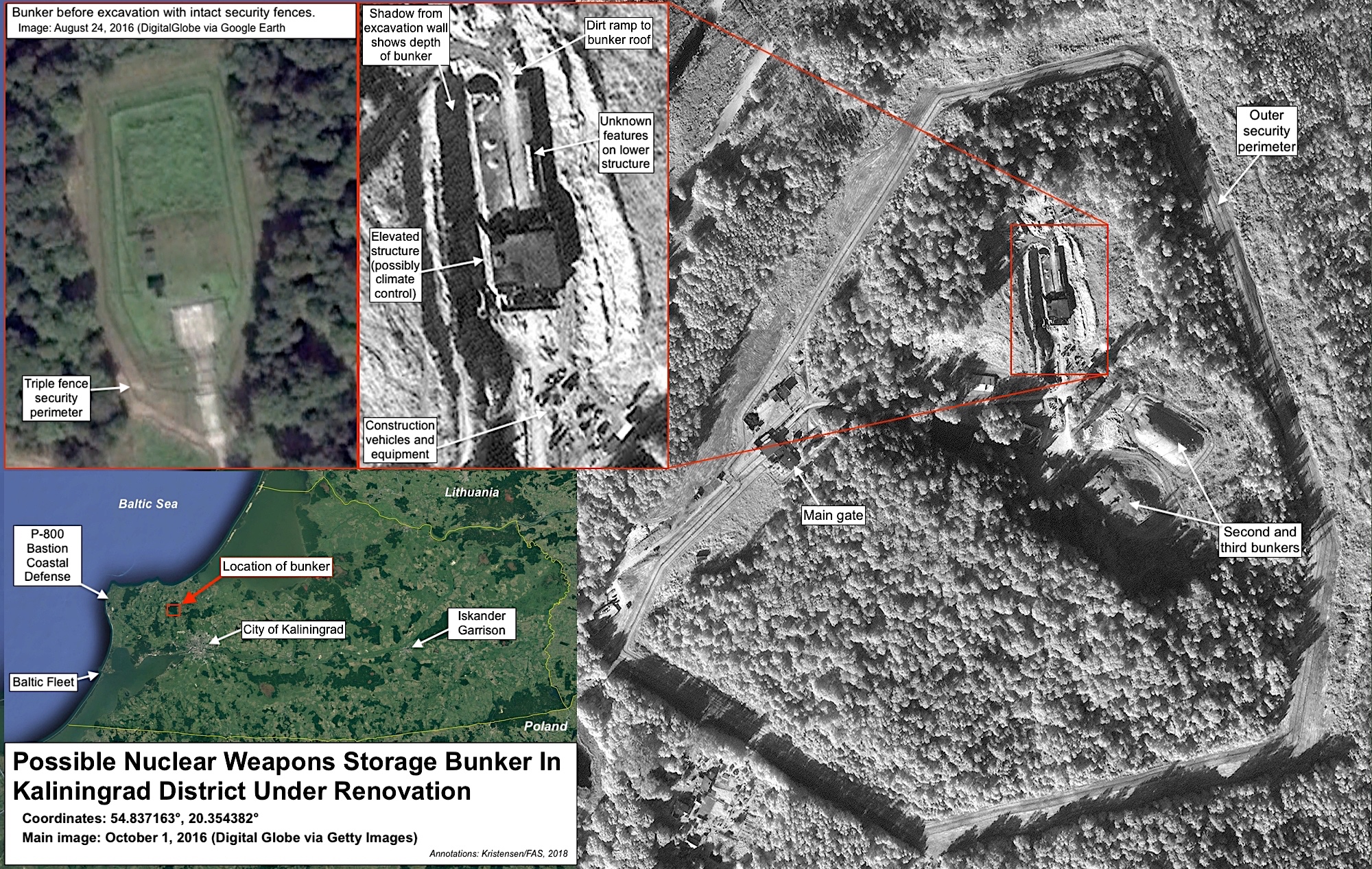

A buried nuclear weapons storage bunker in the Kaliningrad district has been under major renovation since mid-2016. Click on image to see full size.

By Hans M. Kristensen

During the past two years, the Russian military has carried out a major renovation of what appears to be an active nuclear weapons storage site in the Kaliningrad region, about 50 kilometers from the Polish border.

A Digital Globe satellite image purchased via Getty Images, and several other satellite images viewable on TerraServer, show one of three underground bunkers near Kulikovo being excavated in 2016, apparently renovated, and getting covered up again in 2018 presumably to return operational status soon.

The site was previously upgraded between 2002 and 2010 when the outer security perimeter was cleared. I described this development in my report on U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons from 2012.

Between 2002 and 2010, the security perimeter around the Kulikovo nuclear weapons storage site were cleared and upgraded. Click on image to view full size.

The latest upgrade obviously raises questions about what the operational status of the site is. Does it now, has it in the past, or will it in the future store nuclear warheads for Russian dual-capable non-strategic weapon systems deployed in the region? If so, does this signal a new development in Russian nuclear weapons strategy in Kaliningrad, or is it a routine upgrade of an aging facility for an existing capability? The satellite images do not provide conclusive answers to these questions. The Russian government has on numerous occasions stated that all its non-strategic nuclear warheads are kept in “central” storage, a formulation normally thought to imply larger storage sites further inside Russia. So the Kulikovo site could potentially function as a forward storage site that would be supplied with warheads from central storage sites in a crisis.

The features of the site suggest it could potentially serve Russian Air Force or Navy dual-capable forces. But it could also be a joint site, potentially servicing nuclear warheads for both Air Force, Navy, Army, air-defense, and costal defense forces in the region. It is to my knowledge the only nuclear weapons storage site in the Kaliningrad region. Despite media headlines, the presence of nuclear-capable forces in that area is not new; Russia deployed dual-capable forces in Kaliningrad during the Cold War and has continued to do so after. But nearly all of those weapon systems have recently been, or are in the process of being modernized. The Kulikovo site site is located:

- About 8 kilometers (5 miles) miles from the Chkalovsk air base (54.7661°, 20.3985°), which has been undergoing major renovation since 2012 and hosts potentially dual-capable strike aircraft.

- About 27 kilometers (16 miles) from the coastal-defense site near Donskoye (54.9423°, 19.9722°), which recently switched from the SSC-1B Sepal to the P-800 Bastion coastal-defense system. The Bastion system uses the SS-N-26 (3M-55, Yakhont) missile, that U.S. Intelligence estimates is “nuclear possible.”

- About 35 kilometers (22 miles) from the Baltic Sea Fleet base at Baltiysk (54.6400°, 19.9175°), which includes nuclear-capable submarines, destroyers, frigates, and corvettes.

- About 96 kilometers (60 miles) from the 152nd Detachment Missile Brigade at Chernyakovsk (54.6380°, 21.8266°), which has recently been upgraded from the SS-21 SRBM to the SS-26 (Islander) SRBM. Unlike other SS-26 bases, however, Chernyakovsk has not (yet) been added a new missile storage facility.

- Near half a dozen S-300 and S-400 air-defense units deployed in the region. The 2018 NPR states that Russian’s air-defense forces are dual-capable. These sites are located 20 kilometers (13 miles) to 98 kilometers (60 miles) from the storage site.

So there are many potential clients for the Kulikovo nuclear weapons storage site. Similar upgrades have been made to other Russian nuclear weapons storage sites over the base decade, including for the Navy’s nuclear submarine base on the Kamchatka peninsula. There are also ongoing upgrades to other weapons storage sites in the Kaliningrad region, but they do not appear to be nuclear.

A Google street-view image from 2017 shows a military stop sign at the approach to the suspected nuclear weapons storage site north of Kaliningrad. Click image to view full size.

The issue of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons has recently achieved new attention because of the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which accused Russia of increasing the number and types of its non-strategic nuclear weapons. The Review stated Russia has “up to 2,000” non-strategic nuclear weapons, indirectly confirming FAS’ estimate.

NATO has for several years urged Russia to move its nuclear weapons further back from NATO borders. With Russia’s modernization of its conventional forces, there should be even less, not more, justification for upgrading nuclear facilities in Kaliningrad.

Additional Resources:

This publication was made possible by generous grants from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, New Land Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

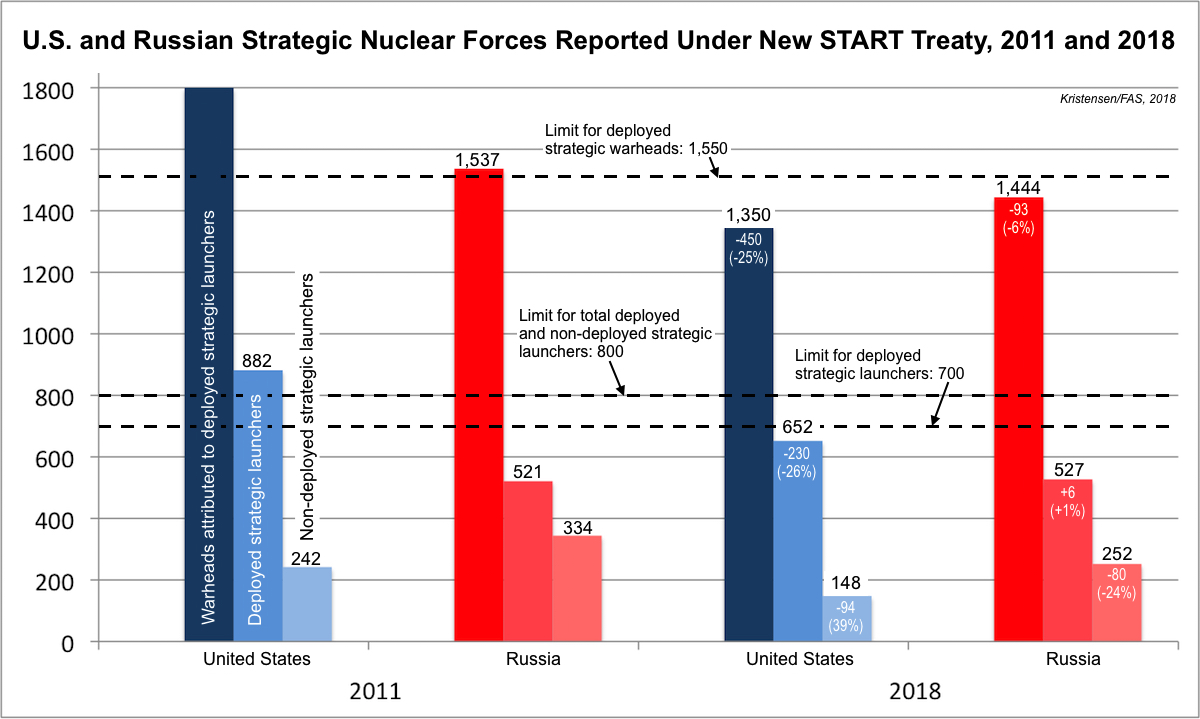

Russia and the United States are currently in compliance with the treaty limits of the New START treaty. This table summarizes the evolution of the three weapons categories reported between 2011 and 2018. (Click on graph to view full size.)

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Note: On February 22nd, the US State Department published updated numbers instead of relying on September 2017 numbers. This blog and tables have been updated accordingly.]

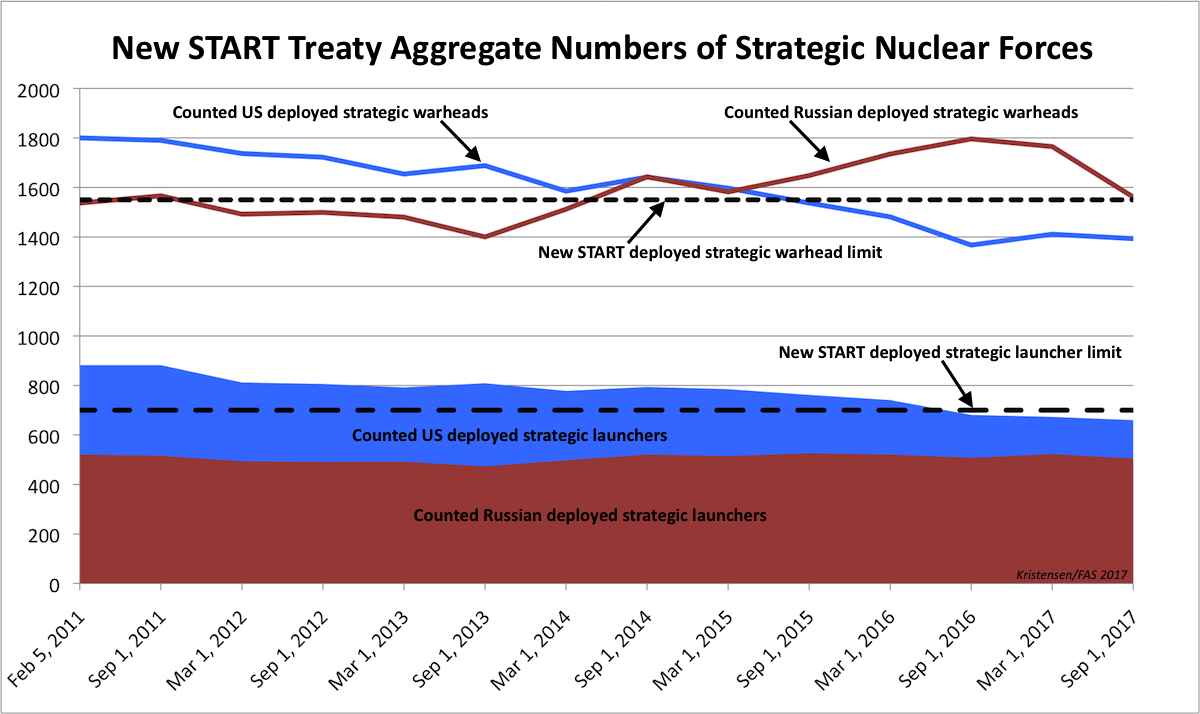

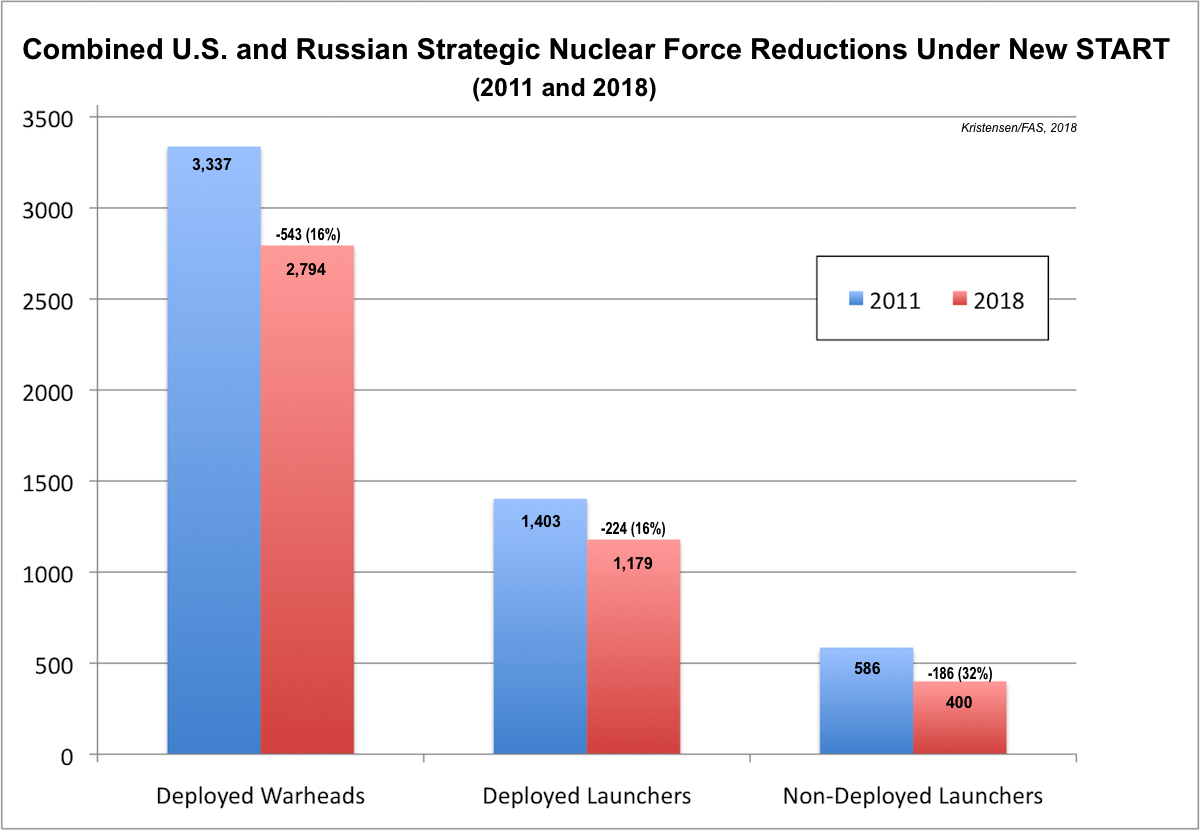

Seven years after the New START treaty between Russia and the United States entered into force in 2011, the treaty entered into effect on February 5. The two countries declared they have met the limits for strategic nuclear forces.

At a time when relations between the two countries are at a post-Cold War low and defense hawks in both countries are screaming for new nuclear weapons and declaring arms control dead, the achievement couldn’t be more timely or important.

Achievements by the Numbers

The declarations show that Russia and the United States currently deploy a combined total of 2,794 warheads on 1,179 deployed strategic launchers. An additional 400 non-deployed launchers are empty, in overhaul, or awaiting destruction.

Compare that with the same categories in 2011: 3,337 warheads on 1,403 deployed strategic launchers with an additional 586 non-deployed launchers.

In other words, since 2011, the two countries have reduced their combined strategic forces by: 543 deployed strategic warheads, 224 deployed strategic launchers, and 186 non-deployed strategic launchers. These are modest reductions of about 16 percent over seven years for deployed forces (see chart below).

The New START data shows the world’s two largest nuclear powers have reduced their deployed strategic force by about 15 percent over the past seven years. (Click on graph to view full size.)

The Russian statement reports 1,444 warheads on 527 deployed strategic launchers with another 392 non-deployed launchers.

That means Russia since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 93, or only 6 percent. The number of deployed launchers has increased a little, by 6, while non-deployed launchers have declined by 80, or 24 percent (see chart below).

The Russian numbers hide an important new development: In order to meet the New START treaty limit, the warhead loading on some Russian strategic missiles has been reduced. The details of the download are not apparent from the limited data published by Russia. I am currently working on developing the estimate for how the download is distributed across the Russian strategic forces. The analysis will be published in a subsequent blog, as well in our next FAS Nuclear Notebook and in the 2018 SIPRI Yearbook.

The US statement lists 1,350 warheads on 652 deployed strategic launchers, and 148 non-deployed launchers.

That means the United States since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 450, or 25 percent. The number of deployed launchers has been reduced by 230, or 26 percent, while the number of non-deployed launchers had declined by 94, or 39 percent (see chart below).

US and Russian strategic force structures differ significantly. As a result, the reductions under New START have affected the two countries differently. Russia has significantly fewer launchers so rely on great warhead-loading to maintain rough overall parity. (Click on chart to view full size.)

In Context

The reason for the different reductions is, of course, that the United States in 2011 had significantly more warheads and launchers deployed than Russia. During the New START negotiations, the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit than proposed by Russia. So while Russia by the latest count has 94 deployed warheads more than the United States, the United States enjoys a sizable advantage of 125 deployed strategic launchers more than Russia. Those extra launchers have a significant warhead upload capacity, a potential treaty breakout capability that Russian officials often complain about.

So despite the importance of the New START treaty and its achievements, not least its important verification regime, the declared numbers are a reminder of how far the two nuclear superpowers still have to go to reduce their unnecessarily large nuclear forces. Ironically, because the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit, Russia could – if it decided to do so, although that seems unlikely – build up its strategic launchers to reduce the US advantage, and still be in compliance with the treaty limits. The United States, in contrast, is at full capacity.

But the apparent download of warheads on Russia’s strategic missiles demonstrates an important effect of New START: It actually keeps a lid on the strategic force levels.

Still, not to forget: The deployed strategic warhead numbers counted under New START represent only a portion of the total number of warheads the two countries have in the arsenals. We estimate that the deployed strategic warheads declared by the two countries represent on about one-third of the total number of warheads in their nuclear stockpiles (see here for details).

This all points to the importance of the two countries agreeing to extend the New START treaty for an additional five years before it expires in 2021. Neither can afford to abandon the only strategic limitations treaty and its verification regime. Failing this most basic responsibility would, especially in the current political climate, remove any caps on strategic nuclear forces and potentially open the door to a new nuclear arms race. The warning signs are all there: East and West are in an official adversarial relationship, increasing military posturing, modernizing and adding nuclear weapons to their arsenals, and adjusting their nuclear policies for a return to Great Power competition.

The symbolic importance of New START could not be greater!

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data: Russia Slashes Deployed Warheads, US Reaches Limits

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has now reached the limits for all three weapons categories under the New START treaty.

The latest data published by the State Department shows that the United States for the first time since the treaty entered into force in 2011 has reached the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. The 660 deployed launchers are also below the treaty limit of 700 and the 1,393 deployed warheads is well below the limit of 1,550. As such, the United States is now technically in compliance with the treaty.

The latest US reductions are the result of denuclearization of bombers and reduction of launch tubes on the Ohio-class submarines.

The data shows that Russia has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 235 in the past 12 months and is now only 11 warheads above the New START treaty limit of 1,550 warheads to be achieved by February 2018. Russia is already below the treaty limit on deployed launchers as well as deployed and non-deployed launchers.

Russia’s increase in deployed strategic warheads between 2013 and 2016 triggered widespread claims by defense hawks that Kremlin was building up its nuclear forces. As I previously pointed out, that was wrong and the result of temporary fluctuations in the Russian force structure. Russia is modernizing, not increasing, its nuclear arsenal.

The Bigger Picture

The latest data shows that the United States has a significant advantage over Russia in deployed strategic launchers; 660 versus 505. The 155-launcher disparity means Russia emphasizes multiple warhead loading on its ICBMs while the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carrying only a single warhead each. A future follow-on treaty will need to address this disparity, which is unhealthy for long-term strategic stability.

Although the United States and Russia are now at, near, or below the limits of the New START treaty, the warheads counted by the treaty only constitute a small fraction of the two countries’ total warhead inventories.

We estimate that Russia has a military stockpile of 4,300 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 7,000 warheads. For its part, we estimate the United States has a military stockpile of 4,000 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 6,800 warheads.

These arsenals are vastly in excess of the nuclear force levels maintained by other nuclear-armed states and constitute more than 90% of the world’s combined inventory of nearly 15,000 nuclear warheads.

Moreover, the New START treaty does not limit the 2,350 non-strategic nuclear warheads we estimate that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals combined. Both sides are modernizing their non-strategic nuclear forces.

Finally, the New START treaty expires in 2021 unless extended for another five years. The Trump administration has previously indicated opposition to extending the treaty, although recent discussions with Russia may seek to change that. A follow-on treaty seems unlikely given the current political climate but could easily be achieved by reducing the excess nuclear forces of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

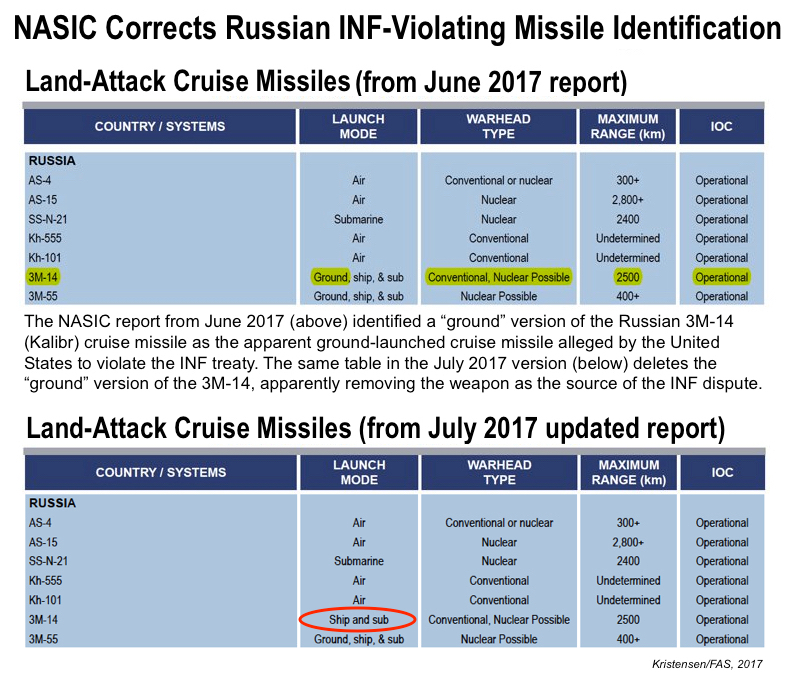

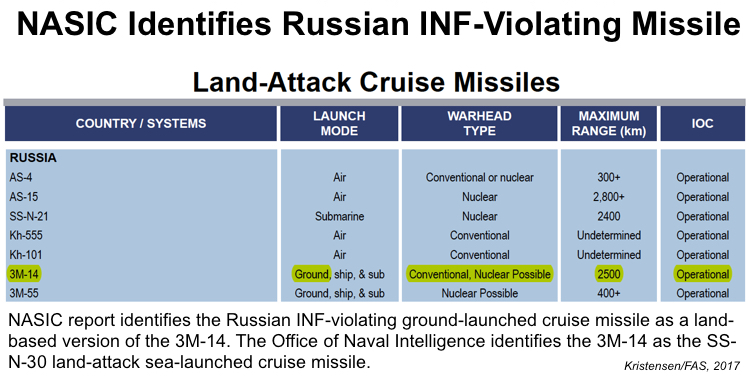

NASIC Removes Russian INF-Violating Missile From Report

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has quietly published a corrected report on the world’s Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats that deletes a previously identified Russian ground-launched cruise missile.

The earlier version, published on June 26, 2017, identified a “ground” version of the 3M-14 land-attack cruise missile that appeared to identify the ground-launched cruise missile the United States has accused Russia of testing and deploying in violation of the 1987 INF Treaty.

The corrected version, available on the NASIC web site, no longer lists a “ground” version of the 3M-14 (popularly referred to as Kalibr) but only ship- and submarine-launched versions of the missile.

Apart from correcting the spelling of the North Korean Bukkeukseong-2 medium-range ballistic missile and downgrading the operational status of the Iranian Shahab-3 medium-range ballistic missile from deployed with “fewer than 50” launchers to “undetermined,” the deletion of the “ground” version of the Russian 3M-14 appears to be the only correction in the new NASIC report. (Curiously, the report still doesn’t identify the Russian Kh-102 air-launched cruise missile). Other than these changes buried deep in the report, however, there are no external markings on the new version to indicate that it has been changed (the URL identifies the new report date as July 21, 2017).

The older version of the NASIC report has been deleted from the NASIC web site, but a copy can be found here.

Implications and Recommendations

The deletion of the 3M-14 as the apparent INF-violating missile from the NASIC report is noteworthy, but it doesn’t actually change much. In essence, it returns the public INF debate to square one where it was three months ago. The correction even helps clear up confusion about the origins and status of the alleged Russian INF violation (several of us in the GNO community have been trying to crosscheck and cross-reference missile designations).

The United States has refused to publicly identify the INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile, apparently to protect intelligence sources. Instead, government sources have described what the missile is not (see here for previous statements). Although NASIC took the time to correct the error, it missed the opportunity to identify the actual INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile.

The correction refocuses the attention back on what I’ve heard all along: That the Russian INF-violating missile is thought to be a modification of the ground-launched SSC-7, a short-range cruise missile used on the Iskander system. But U.S. intelligence officials are adamant that the INF-violating missile is not the Iskander but a state-of-the-art missile. The new missile is known in the U.S. intelligence community as the SSC-8. The launcher itself apparently is physically different from the one used for the SSC-7. I co-authored a paper about this with the Deep Cuts Commission in April.

Apparently one battalion is operational and a second is fitting out, potentially embedded with Islander battalions starting in central Russia, and deployments are expected eventually in all four Russian military districts. So far, however, according to U.S. officials, the SSC-8 does not appear to give Russia any military advantage in Europe. And the U.S. military already has the military capability to counter the SSC-8 with sea- and air-launched cruise missiles and other means.

The U.S. refusal to identify the missile has given the Russian government the public space to “play ignorant” and claim it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about. Similarly, the secrecy has made it difficult for allied governments to verify the claim and privately and publicly assist the United States with putting pressure on Russia to return to treaty compliance. That, in turn, has allowed hardliners in the U.S. Congress to propose that the United States should also develop it’s own ground-launched cruise missile (something the U.S. military does not believe is necessary).

Rather than making a bad situation worse, in order to sustain and increase pressure on Russia to return to INF compliance, the United States must reinforce its own commitment to the treaty by rejecting any Cold War proposal to mimic Russia’s bad behavior by developing a U.S. ground-launched cruise missile and instead focus potential military responses on existing forces already widely available, remove public ambiguity by identifying the Russia missile and disclose the information it has shared with Russia (if it can tell the Kremlin, then it can also tell the rest of the world), increase intelligence sharing with allies to improve their ability to work the issue with Russia directly, and pursue the matter directly with Russia in the Special Versification Commission of the INF treaty.

Background information:

- NASIC (corrected) report on Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats

- NASIC (previous) report on Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats

- FAS review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

- Deep Cuts Commission: Preserving the INF Treaty

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

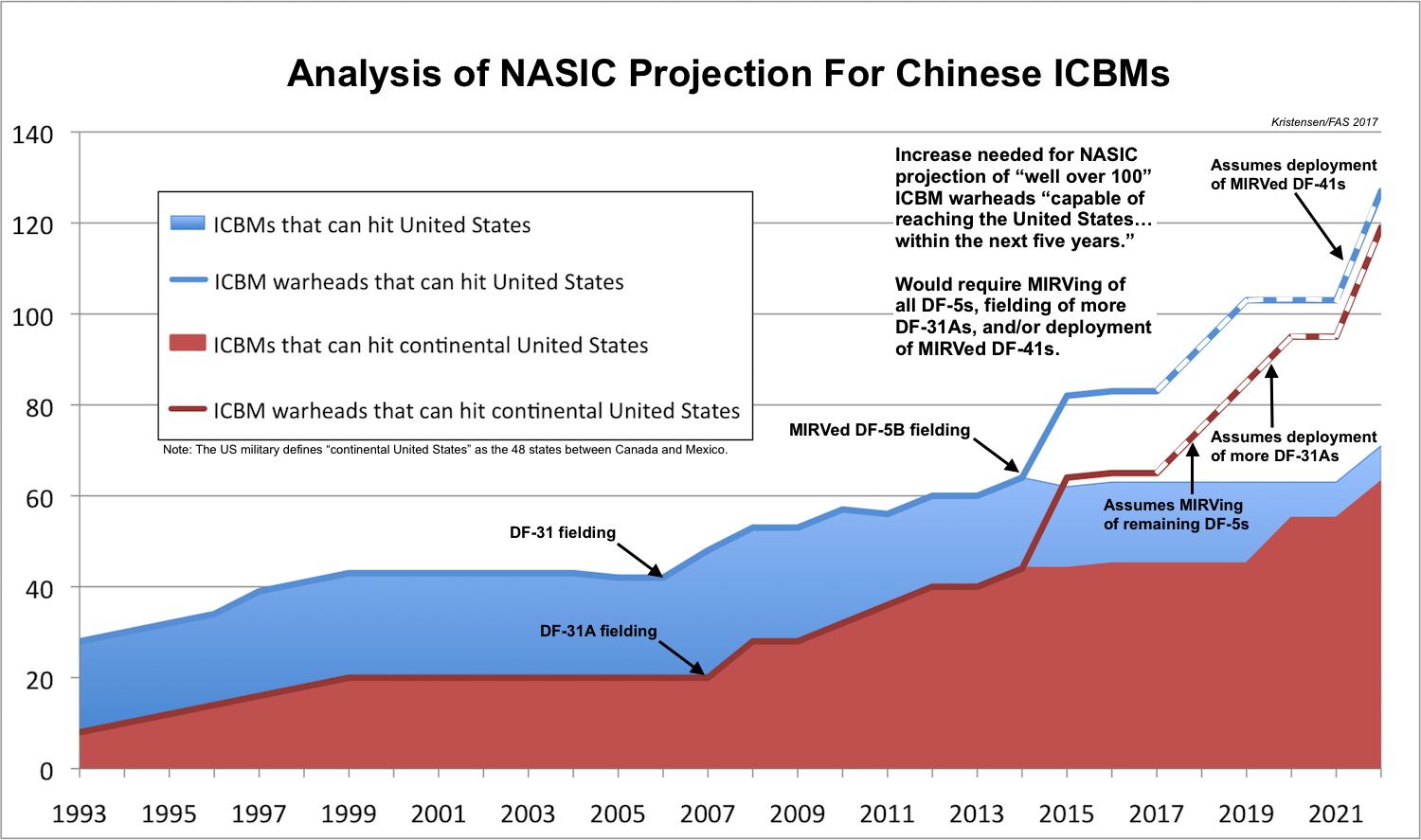

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Yet the description of the DF-31A program sounds like deployment is still in progress: “The longer range CSS-10 Mod 2 will allow targeting of most of the continental United States” (emphasis added).

For the first time, the report includes a graphic illustration of the DF-31 and DF-31A side by side, which shows the longer-range DF-31A to be little shorter but with a less pointy nosecone and a wider third stage (see image).

The long-awaited (and somewhat mysterious) DF-41 ICBM is still not deployed. NASIC says the DF-41 is “possibly capable of carrying MIRV,” a less certain determination than the 2017 DOD report, which called the missile “MIRV capable.” The report lists the DF-41 with three stages and a Post-Boost Vehicle, details not provided in the previous report.

One of the two nuclear versions of the DF-21 MRBM appears to have been retired. NASIC only lists one: CSS-5 Mod 2. In total, the report lists “fewer than 50” launchers for the nuclear version of the DF-21, which is the same number it listed in the 2013 report (see here for description of one of the DF-21 launch units. But that was also the number listed back then for the older nuclear DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1). The nuclear MRBM force has probably not been cut in half over the past four years, so perhaps the previous estimate of fewer than 50 launchers was intended to include both versions. The NASIC report does not mention the CSS-5 Mod 6 that was mentioned in the DOD’s annual report from 2016.

Sea-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report lists a total of 48 JL-2 SLBM launchers, corresponding to the number of launch tubes on the four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. That does not necessarily mean, however, that the missiles are therefore fully operational or deployed on the submarines under normal circumstances. They might, but it is yet unclear how China operates its SSBN fleet (for a description of the SSBN fleet, see here).

The 2017 report no longer lists the Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN or the JL-1 SLBM, indicating that China’s first (and not very successful) sea-based nuclear capability has been retired from service.

Cruise Missiles: The new report removes the “conventional or nuclear” designation from the DH-10 (CJ-10) ground-launched land-attack cruise missile. The possible nuclear option for the DH-10 was listed in the previous three NASIC reports (2006, 2009, and 2013). The DH-10 brigades are organized under the PLA Rocket Force that operates both nuclear and conventional missiles.

A US Air Force Global Strike Command document in 2013 listed another cruise missile, the air-launched DH-20 (CJ-20), with a nuclear option. NASIC has never attributed nuclear capability to that weapon and the Office of the Secretary of Defense stated recently that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.”

At the same time, the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently told Congress that China was upgrading is cruise missiles further, including “with two, new air-launched ballistic [cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Pakistan

The NASIC report surprisingly does not list Pakistan’s Babur GLCM as operational.

The NASIC report states that “Pakistan continues to improve the readiness and capabilities of its Army Strategic Force Command and individual strategic missile groups through training exercises that include live missile firings.” While all nuclear-armed states do that, the implication probably is that Pakistan is increasing the reaction time of its nuclear missiles, particularly the short-range weapons.

The report states that the Shaheen-2 MRBM has been test-launched “seven times since 2004.” While that fits the public record, NASIC doesn’t mention that the Shaheen-2 for some reason has not been test launched since 2014, which potentially could indicate technical problems.

The Abdali SRBM now has a range of 200 km (up from 180 km in the 2013 report). It is now designated as close-range ballistic missile instead of a short-range ballistic missile.

NASIC describes the Ababeel MRBM, which was first test-launch in January 2017, as as “MIRVed” missile. Although this echoes the announcement made by the Pakistani military at the time, the designation “the MIRVed Abadeel” sounds very confident given the limited flight history and the technological challenges associated with developing reliable MIRV systems.

Neither the Ra’ad ALCM nor the Babur GLCM is listed as deployed, which is surprising especially for the Babur after 13 flight tests. Babur launchers have been fitting out at the National Development Complex for years and are visible at some army garrisons. Nor does NASIC mention the Babur-2 or Babur-3 (naval version) versions that have been test-flown and announced by the Pakistani military.

India

It is a surprise that the NASIC report only lists “fewer than 10” Agni-2 MRBM launchers. This is the same number as in 2013, which indicates there is still only one operational missile group equipped with the Agni-2 seven years after the Indian government first declared it deployed. The slow introduction might indicate technical problems, or that India is instead focused on fielding the longer-range Agni-3 IRBM that NASIC says is now deployed with “fewer than 10” launchers.

Neither the Agni-4 nor Agni-5 IRBMs are listed as deployed, even though the Indian government says the Agni-4 has been “inducted” into the armed forces and has reported three army “user trial” test launches. NASIC says India is developing the Agni-6 ICBM with a range of 6,000 km (3,728 miles).

For India’s emerging SSBN fleet, the NASIC report lists the short-range K-15 SLBM as deployed, which is a surprise given that the Arihant SSBN is not yet considered fully operational. The submarine has been undergoing sea-trials for several years and was rumored to have conducted its first submerged K-15 test launch in November 2016. But a few more are probably needed before the missile can be considered operational. The K-4 SLBM is in development and NASIC sets the range at 3,500 km (2,175 miles).

As for cruise missiles, it is helpful that the report continue to list the Bramos as conventional, which might help discredit rumors about nuclear capability.

North Korea

Finally, of the nuclear-armed states, NASIC provides interesting information about North Korea’s missile programs. None of the North Korean ICBMs are listed as deployed.

The report states there are now “fewer than 50” launchers for the Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM. NASIC sets the range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles) instead of the 4,000 km (2,485 miles) sometimes seen in the public debate.

Likewise, while many public sources set the range of the mobile ICBMs (KN-08 and KN-14) as 8,000 km (4,970 miles) – some even longer, sufficient to reach parts of the United States, the NASIC report lists a more modest range estimate of 5,500+ km (3,418 miles), the lower end of the ICBM range.

Additional Information:

- Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2017 [Note: A corrected NASIC report was published in June 2017.]

- Previous versions of this NASIC report: 2006, 2009, 2013

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Defense Intelligence Agency Views Russian Military Power

The Defense Intelligence Agency yesterday launched a new series of unclassified publications on foreign military threats to the United States with a report on the Russian military.

“The resurgence of Russia on the world stage — seizing the Crimean Peninsula, destabilizing eastern Ukraine, intervening on behalf of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, and shaping the information environment to suit its interests — poses a major challenge to the United States,” the report said.

The 116-page report provides DIA data and perspective on Russian military strategy, force structure, defense spending, intelligence, nuclear weaponry, cyber programs, foreign arms sales, and more. Though unclassified and citing open sources, it is presumably consistent with DIA’s classified collection. See Russia Military Power 2017 published by the Defense Intelligence Agency, June 2017.

The new publication is inspired by the Soviet Military Power series that was published by DIA in the 1980s to draw critical attention to Soviet military programs. Both informative and provocative, Soviet Military Power was immensely popular by government document standards though it was viewed by some critics as verging on, or crossing over into, propaganda.

The new report usefully describes official US perceptions of Russian military programs and intentions, allowing those perceptions to be scrutinized, discussed and corrected as necessary. “These products are intended to foster a dialogue between U.S. leaders, the national security community, partner nations, and the public,” DIA said.

A companion report on China Military Power, among others, is expected to be published shortly.

Legality of the Trump Disclosures, Revisited

When President Trump disclosed classified intelligence information to Russian officials last week, did he commit a crime?

Considering that the President is the author of the national security classification system, and that he is empowered to determine who gets access to classified information, it seems obvious that the answer is No. His action might have been reckless, I opined previously, but it was not a crime.

Yet there is more to it than that.

The Congressional Research Service considered the question and concluded as follows in a report issued yesterday:

“It appears more likely than not that the President is presumed to have the authority to disclose classified information to foreign agents in keeping with his power and responsibility to advance U.S. national security interests.” See Presidential Authority to Permit Access to National Security Information, CRS Legal Sidebar, May 17, 2017.

This tentative, rather strained formulation by CRS legislative attorneys indicates that the question is not entirely settled, and that the answer is not necessarily obvious or categorical.

And the phrase “in keeping with his power and responsibility to advance U.S. national security interests” adds an important qualification. If the president were acting on some other agenda than the U.S. national interest, then the legitimacy of his disclosure could evaporate. If the president were on Putin’s payroll, as the House majority leader lamely joked last year, and had engaged in espionage, he would not be beyond the reach of the law.

Outlandish hypotheticals aside, it still seems fairly clear that the Trump disclosures last week are not a matter for the criminal justice system, though they may reverberate through public opinion and congressional deliberations in a consequential way.

But several legal experts this week insisted that it’s more complicated, and that it remains conceivable that Trump broke the law. See:

“Don’t Be So Quick to Call Those Disclosures ‘Legal'” by Elizabeth Goitein, Just Security, May 17, 2017

“Why Trump’s Disclosure to Russia (and Urging Comey to Drop the Flynn Investigation, and Various Other Actions) Could Be Unlawful” by Marty Lederman and David Pozen, Just Security, May 17, 2017

“Trump’s disclosures to the Russians might actually have been illegal” by Steve Vladeck, Washington Post, May 16, 2017

Update, 05/23/17: But see also Trump’s Disclosure Did Not Break the Law by Morton Halperin, Just Security, May 23, 2017.

An Authorized Disclosure of Classified Information

Updated below

President Trump’s disclosure of classified intelligence information to Russian officials, reported by the Washington Post, may have been reckless, damaging and irresponsible. But it was not a crime.

Disclosures of classified information are not categorically prohibited by law. Even intelligence sources and methods are only required to be protected under the National Security Act from “unauthorized disclosure.” This leaves open the possibility that disclosures of such classified information can actually be authorized. And we know that they are, from time to time.

One statute in particular — 18 USC 798 — does come close to matching the circumstances of the Trump disclosure to Russia, with a crucial exception.

That statute makes it a felony to disclose to an unauthorized person any classified information “concerning the communication intelligence activities of the United States or any foreign government; or […] obtained by the processes of communication intelligence from the communications of any foreign government.”

But it further explains that an “unauthorized person” is one who has not been “authorized to receive information… by the President.”

This morning, President Trump tweeted that “As President I wanted to share with Russia (at an openly scheduled W.H. meeting) which I have the absolute right to do, facts pertaining to terrorism and airline flight safety. Humanitarian reasons, plus I want Russia to greatly step up their fight against ISIS & terrorism.”

(Was the gratuitous parenthetical phrase “at an openly scheduled W.H. meeting” intended to rule out a clandestine transfer of classified information?)

All of that is to say that this episode, though it may have far-reaching ramifications for national security, is probably not a matter for law enforcement. (Based on the reporting by the Washington Post, the President’s actions did violate the terms of an intelligence sharing agreement with a foreign government that supplied the information. But that agreement would not be enforced by the criminal justice system.)

Instead, this is something to be weighed by Congress, which has the responsibility to determine whether Donald J. Trump is fit to remain in office.

Update, 05/17/17: For contrasting views arguing that Trump’s disclosure of classified intelligence to the Russians may actually have been illegal, see Marty Lederman and David Pozen, Liza Goitein, and Stephen Vladeck.

Update, 05/23/17: See also Trump’s Disclosure Did Not Break the Law by Morton Halperin, Just Security, May 23.