Long-term effects of disasters: an ongoing threat to public health

2025 was a costly extreme weather year. January kicked off with the Palisades and Eaton wildfires, which caused an estimated 31 deaths in Los Angeles County and billions of dollars in economic damages. Texas experienced some of its worst flooding in decades in July, resulting in the deaths of more than 100 people, many of whom were children staying at an overnight summer camp. In October, flooding in Alaska led to at least one person’s death and the displacement of more than 1,500 others as whole villages were inundated from the remnants of Typhoon Halong.

However, even though 2025 is over, the effects of these disasters are not.

There is considerable interest from both sides of the political aisle in reforming FEMA. The reform conversation has largely focused on where responsibility for disaster response should sit – with the federal government, or with the states? But from a public health perspective, we should be talking about something even more important: our hyperfocus on short-term disaster effects that causes us to neglect the longer-term needs of disaster-affected survivors and communities.

Disasters create ripple effects on health that can extend into the months, years, and even decades after fires are put out, winds die down, and floodwaters recede. While these effects are hard to precisely measure, they are undeniably potent. Official data, for instance, indicate that hurricanes and other tropical cyclones cause an average of 24 deaths per storm. That number is too high – every death is a tragedy – but it pales in comparison to the 7,000 – 11,000 deaths that studies estimate actually come from storms’ longer-term consequences.

With extreme weather events becoming ever-more common, there is a national and moral imperative to rethink not just who responds to disasters, but for how long and to what end. This issue brief presents an overview of the ways in which disasters affect public health and well-being in the long term, as well as suggestions for disaster governance reform viewed through a public health lens.

Disasters impose sustained effects on physical and mental health

The evidence is clear: disasters cause suffering that persists long after national attention turns elsewhere. The same study cited above also found that the adverse health effects of hurricanes and other tropical cyclones were most pronounced in infants under the age of one almost two years after a given storm. If you do the math, this means the storms continued to increase the infants’ risk of death despite them not having even been conceived at landfall, suggesting that the true damage from hurricanes (and likely other natural hazards) comes from the stress they put on families and communities. This doesn’t just apply to infants, but other vulnerable groups, such as older adults. For example, older adults who lived through Superstorm Sandy had higher risks of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality five years after the storm had passed.

Why do exposures to extreme weather events have these long-term health impacts? More research is needed, but so far at least three likely pathways have been identified.

Disasters can expose survivors to hazardous conditions that increase their risk of chronic illnesses. For example, hazardous particles from wildfire smoke can settle into people’s lungs and negatively affect lung function for years, which is especially dangerous when individuals have pre-existing respiratory conditions like asthma or COPD. This decreased lung function has been shown to last at least two years after the wildfire for some individuals. Individuals living in high-risk areas where wildfires frequently occur may never get the chance to fully recover.

The physical damages from a disaster to the built and natural environments that surround survivors can become hazardous to human health. For instance, when disasters knock out power during a heatwave or cold snap, individuals can be exposed to dangerous temperature extremes. Heatwaves alone can increase the risk of chronic kidney disease, and can even make the body age faster, while those who have experienced heat illness and heat stroke are at risk of organ damage, including damage to the brain. Other disasters can spread harmful toxins. Floodwaters often contain hazardous waste from runoff and sewage system overflow, increasing the risk of illness in the months following the flood. Homes and businesses that flooded are also at risk of growing toxic mold, especially in warm and humid environments (like the hurricane-prone Southeast United States). What is especially challenging about mold is that it can be difficult to detect and can persist for years unless treated, leading to families living in toxic environments without ever knowing it. Exposure to mold increases the risk for various diseases and health problems, including asthma attacks and infections, and are particularly concerning for sensitive individuals, like those who are immunocompromised. Similarly, when wildfires burn houses, vehicles, and other infrastructure, this releases toxic ash and other debris into the air for hundreds of miles, contaminating the lands and waters of communities for years. Airborne toxins released during wildfires can settle on indoor surfaces and in heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems. These harmful exposures can contribute to serious long-term health conditions like cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and cancer.

Living through a disaster and then navigating a byzantine recovery landscape can contribute to chronic stress that takes a toll on mental and physical health. Several studies suggest that exposure to disasters increases the risk of mental health challenges like depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress, affects people of all age groups, including children, and can last for years. One study found that survivors of Hurricane Katrina were still dealing with post-traumatic stress symptoms twelve years later. Poor mental health can lead to poor physical health in the long term (such as an increased risk of chronic diseases and premature death), as people deal with the toll chronic stress can have on the body. This stress can also increase risk of cognitive decline and dementia, and considering that chronic stress is common among disaster survivors, it’s no wonder that wildfires, hurricanes, and heat waves have all been found to be associated with cognitive decline and dementia too.

Disasters disrupt healthcare delivery and operations

Access to healthcare, including going to doctor’s appointments, getting prescription refills, and receiving specialty treatment (like chemotherapy or dialysis), is critical for keeping people healthy and maintaining quality of life. Unfortunately, disasters often displace people from their homes, communities, and from the healthcare services they depend on. For many people, displacement after a disaster is permanent. These people must then navigate entirely new environments, find new healthcare providers, and become re-established with the medical system all the while securing a place to live, meeting their other needs, and dealing with the stress of losing their life as they knew it. Medical care often falls to the wayside in the chaos of disaster recovery, leaving survivors vulnerable to worsening health conditions over time.

Disasters often displace people from their homes, communities, and from the healthcare services they depend on. Take for instance, these flooded homes adjacent to the Red River in North Dakota, via Wikimedia Commons

Even if displacement is only temporary, when residents return to their homes and communities they may find that their healthcare options no longer exist, as disasters can disrupt or destroy entire healthcare systems. Damaged clinics and hospitals may be temporarily or permanently shut down, creating healthcare “deserts” that lack sufficient healthcare infrastructure to treat people. Rural areas are particularly vulnerable to these disruptions, as they already face limited budgets and fewer resources – leaving less “cushion” to absorb disaster impacts. Disasters can also disrupt supply chains, impacting the quality of medical care for entire regions. This occurred when Hurricane Helene flooded one of the major medical IV suppliers in the United States, leading to IV shortages at healthcare facilities that persisted even months after the hurricane.

Disasters drive housing insecurity

Having an affordable and stable place to live is one of the most important social determinants of health. Access to housing that is safe, clean, and sheltered from the elements can affect everything from risk of hospitalization, the number of medications someone takes, mortality, and overall quality of life. Unfortunately, housing is also one of the most vulnerable and deeply personal domains to be affected by disasters. Many are forced to flee from fires, floods, high winds, or other dangerous conditions presented by natural hazards, and people can be displaced from their homes for months or years at a time – or even permanently. This displacement is associated with numerous mental and physical health issues, including risk of death. And as insurance premiums continue to increase or insurance companies withdraw from states altogether because of the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters, homeowners may be unable to afford property insurance altogether in the near future, further reducing the chances of ever being able to return home.

Even for those who could return home, the cost of recovery may be too prohibitive. For wildfire survivors, many insurance companies do not include smoke damage testing and remediation costs under their policies, and even some plans that cover smoke damage may refuse to remediate, which can cost thousands of dollars out-of-pocket. For flood survivors, mold can be difficult to detect and may require the services of a professional cleaner, which can be prohibitively expensive. Even if someone has flood insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), mold remediation is not typically covered, creating barriers for people trying to make their homes healthy to live in again. If someone’s insurance plan covers mold remediation, many plans make exceptions if action to prevent mold growth is not taken in the immediate days after the flood, which can pose a problem for those blocked from returning under emergency orders. These policy barriers result in survivors having to either relocate away from their homes and communities, or continue to live in unsafe conditions that can chronically affect their health.

Opportunities for Action

Our nation needs policies that understand and address the true public health effects of disasters over the months and years after the disaster is technically “over”. Opportunities for action include:

Update how health impacts are measured. Tracking of health impacts from disasters is generally limited to the direct impacts of disasters (i.e., injuries and deaths, like drownings from floods and smoke asphyxiation from wildfires). Few official data sources capture the indirect effects of disasters that take more time to manifest. Impact assessments should include epidemiological methodology that can capture these indirect effects, such as excess death calculations, to begin to truly understand and quantify the extent of disasters on peoples’ health.

Reinstate disrupted grants and other funding for health research relevant to disasters. Recent budget cuts, terminated grants, and increased hostility towards public health threaten our ability to understand – and therefore effectively address – the health impacts of disasters. Policymakers should reinstate such funding, and look for opportunities to prioritize research related to the longer-term and often overlooked impacts.

Invest in the physical resilience of healthcare infrastructure. Investments in the physical resilience of healthcare infrastructure (such as the installation of hurricane-proof glass, flood barriers, air filtration systems, etc.) strengthens disaster resilience and reduces the overall health impacts of disasters in the short and long terms. Studies show that these investments pay off in the long run, with every dollar dedicated to resilience yielding multiple dollars in avoided societal costs – and providing strong justification for state and federal resources to catalyze and support such investments.

Strengthen medical supply chains. The Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) provides a critical reserve of essential medical equipment, buffering health supply chains against disruptions from events like disasters. Congress should act to increase the SNS, particularly in locations that could provide rapid response of medical provisions to disaster-affected areas, and ensure that key medical suppliers are adequately prepared for future disasters.

Help with housing. One of the most efficient and effective means of disaster recovery is ensuring survivors have access to stable, safe, and healthy housing. One way to achieve this is by creating a centralized agency or entity (such as the Joint County-State Housing Task Force established in the wake of the 2025 Los Angeles wildfires) to handle housing-specific needs from disasters and for those displaced. At the federal level, this could look like integration of housing-relevant capabilities and authorities across agencies such as the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA, particularly FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Program), the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the Small Business Administration. Other options could include streamlining access to housing relief funds (such as by creating a consolidated hub for applications for assistance), creating pre-approved resilient home designs that can be fast-tracked for permitting and construction, and establishing well-defined responsibilities for remediation efforts, including cleaning of contaminated lands and homes. (Note: many of these issues are addressed in the proposed FEMA Act of 2025.)

Support on-the-ground efforts. Federal and state agencies can support nonprofit rapid response teams (such as SBP) equipped with cleaning and rebuilding supplies. These teams can be rapidly organized and deployed to mitigate physical damage from disasters, making it faster and safer for survivors to return home. As these teams often include members of affected communities, they often have a deep understanding of what the needs of survivors truly are, enabling more efficient use of resources.

Conclusion

Disaster survivors want reform – but drastically reducing FEMA’s workforce without investing in any new disaster-response capabilities isn’t the type of reform they want. Rather, survivors are looking for leaders to institute more holistic disaster-governance strategies that include efforts to minimize long-term negative impacts, instead of the drop-in/rapid withdrawal pattern historically demonstrated. If we are to make (and keep) Americans healthy, then it’s time to make sure considerations for the long-term health needs of disaster survivors are being met, even after the winds, floods, and fires are gone.

A National Blueprint for Whole Health Transformation

Despite spending over 17% of GDP on health care, Americans live shorter and less healthy lives than their peers in other high-income countries. Rising chronic disease and mental health challenges as well as clinician burnout expose the limits of a system built to treat illness rather than create health. Addressing chronic disease while controlling healthcare costs is a bipartisan goal, the question now is how to achieve this shared goal? A policy window is opening now as Congress debates health care again – and in our view, it’s time for a “whole health” upgrade.

Whole Health is a proven, evidence-based framework that integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community support so that people can live healthier, longer, and more meaningful lives. Pioneered by the Veterans Health Administration, Whole Health offers a redesign to U.S. health and social systems: it organizes how health is created and supported across sectors, shifting power and responsibility from institutions to people and communities. It begins with what matters most to people–their purpose, aspirations, and connections–and aligns prevention, clinical care, and social supports accordingly. Treating Whole Health as a shared public priority would help ensure that every community has the conditions to thrive.

Challenge and Opportunity

The U.S. health system spends over $4 trillion annually, more per capita than any other nation, yet underperforms on life expectancy, infant mortality, and chronic disease management. The prevailing fee-for-service model fragments care across medical, behavioral, and social domains, rewarding treatment over prevention. This fragmentation drives costs upward, fuels clinician burnout, and leaves many communities without coordinated support.

At this inflection point in our declining health outcomes and growing public awareness of the failures of our health system, federal prevention and public health programs are under review, governors are seeking cost-effective chronic disease solutions, and the National Academies is advocating for new healthcare models. Additionally, public demand for evidence-based well-being is growing, with 65% of Americans prioritizing mental and social health. There is clear demand for transformation in our health care system to deliver results in a much more efficient and cost effective way.

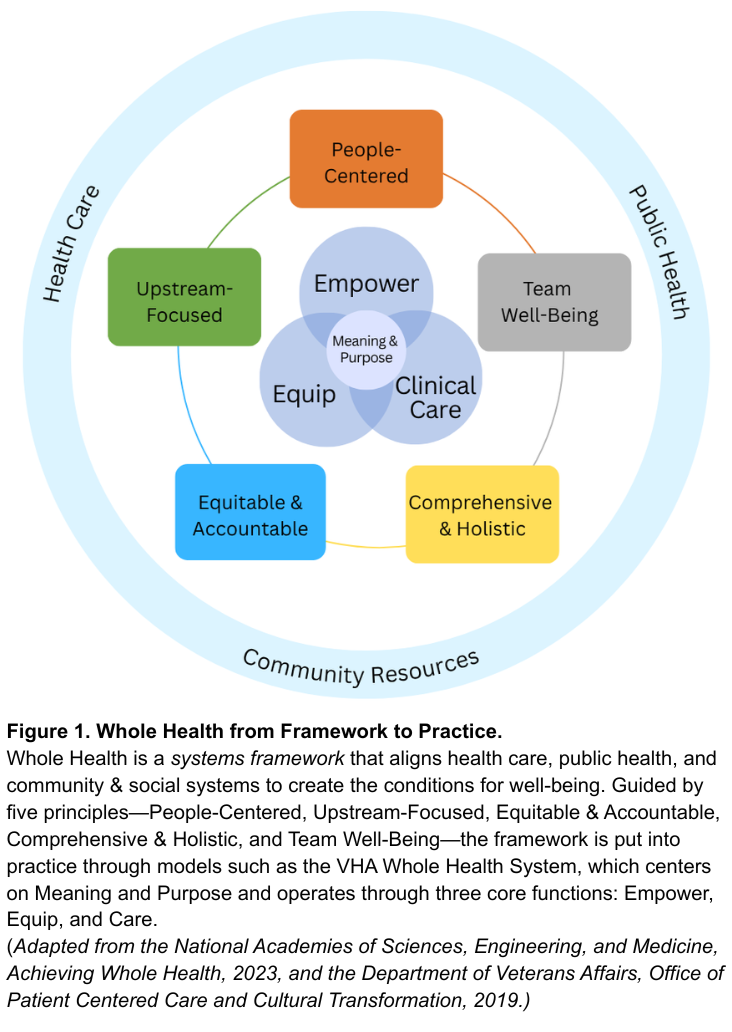

Veterans Health Administration’s Whole Health System Debuted in 2011

Whole Health offers a system-wide redesign for the challenge at hand. As defined by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Whole Health is a framework for organizing how health is created and supported across sectors. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and community resources. As shown in Figure 1, the framework connects five system principles—People-Centered, Upstream-Focused, Equitable & Accountable, Comprehensive & Holistic, and Team Well-Being–that guide implementation across health and social support systems. The nation’s largest health system, the Veterans Health Administration’s (VHA), has demonstrated this framework in clinical practice through their Whole Health System since 2011. The VHA’s Whole Health System operates through three core functions: Empower (helping individuals define purpose), Equip (providing community resources like peer support), and Clinical Care (delivering coordinated, team-based care). Together, these elements align with what matters most to people, shifting the locus of control from expert-driven systems to shared agency through partnerships. The Whole Health System at the VHA has reduced opioid use and improved chronic disease outcomes.

Successful State Examples

Beyond the VHA, states have also demonstrated the possibility and benefits of Whole Health models. North Carolina’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots extended Medicaid coverage to housing, food, and transportation, showing fewer emergency visits and savings of about $85 per member per month. Vermont’s Blueprint for Health links primary care practices with community health teams and social services, reducing expenditures by about $480 per person annually and boosting preventive screenings. Finally, the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), currently being implemented in 33 states, utilizes both Medicare and Medicaid funding to coordinate medical and social care for older adults with complex medical needs. While improvements can be made to national program-wide evaluation, states like Kansas have done evaluations that have found that the PACE program is less expensive than nursing homes per beneficiary and that nursing home admissions decline by 5% to 15% for beneficiaries.

Success across each of these examples relies on three pillars: (1) integrating medical, behavioral, social, and public health resources; (2) sustainable financing that prioritizes prevention and coordination; and (3) rigorous evaluation of outcomes that matter to people and communities. While these programs are early signs of success of Whole Health models, without coordinated leadership, efforts will fragment into isolated pilots and it will be challenging to learn and evolve.

A policy window for rethinking the health care system is opening. At this national inflection point, the U.S. can work to build a unified Whole Health strategy that enables a more effective, affordable and resilient health system.

Plan of Action

To act on this opportunity, federal and state leaders can take the following coordinated actions to embed Whole Health as a unifying framework across health, social, and wellbeing systems.

Recommendation 1. Declare Whole Health a Federal and State Priority.

Whole Health should become a unifying value across federal and state government action on health and wellbeing, embedding prevention, connection, and integration into how health and social systems are organized, financed, and delivered. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. The Executive Office of the President should create a Whole Health Strategic Council that brings together Veterans Affairs (VA), Health and Human Services (e.g. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), and Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)), Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to align strategies, budgets, and programs with Whole Health principles through cross-agency guidance and joint planning. This council should also work with Governors to establish evidence-based benchmarks for Whole Health operations and evaluation (e.g., person-centered planning, peer support, team integration) and shared outcome metrics for well-being and population health.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Authorize whole health benefits, like housing assistance, nutrition counseling, transportation to appointments, peer support programs, and well-being centers as reimbursable services under Medicare, Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act health subsidies.

- State Action. Adopt Whole Health models through Medicaid managed-care contracts and through CDC and HRSA grant implementation. States should also develop support for Whole Health services in trusted local settings such as libraries, faith-based organizations, senior centers, to reach people where they live and gather.

Recommendation 2. Realign Financing and Payment to Reward Prevention and Team-Based Care.

Federal payment modalities need to shift from a fee-for-service model toward hybrid value-based models. Models such as per-member-per-month payments with quality incentives, can sustain comprehensive, team-based care while delivering outcomes that matter, like reductions in chronic disease and overall perceived wellbeing. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Expand Advanced Primary Care Management (APCM) payments to include Whole Health teams, including clinicians, peer coaches, and community health workers. Ensure that this funding supports coordination, person-centered planning, and upstream prevention, such as food as medicine programs. Further, CMS can expand reimbursements to community health workers and peer support roles and standardize their scope-of-practice rules across states.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Invest in Medicare and Medicaid innovation programs, such as the CMS Innovation Center (CMMI), that reward prevention and chronic disease reduction. Additionally, expand tools for payment flexibility, through Medicaid waivers and state innovation funds, to help states adapt Whole Health models to local needs.

- State Action. Require Medicaid managed-care contracts to reimburse Whole Health services, particularly in underserved and rural areas, and encourage payers to align benefit designs and performance measures around well-being. States should also leverage their state insurance departments to guide and incentivize private health insurers to adopt Whole Health payment models.

Recommendation 3. Strengthen and Expand the Whole Health Workforce.

Whole Health practice needs a broad team to be successful: clinicians, community health workers, peer coaches, community organizations, nutritionists, and educators. To build this workforce, governments need to modernize training, assess the workforce and workplace quality, and connect the fast-growing well-being sector with health and community systems. Actions include:

- Federal Executive Action. Through VA and HRSA establish Whole Health Workforce Centers of Excellence to develop national curricula, set standards, and disseminate evidence on effective Whole Health team-building. Further, CMS should track workforce outcomes such as retention, burnout, and team integration, and evaluate the benefits for health professionals working in Whole Health systems versus traditional health systems.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Expand CMS Graduate Medical Education Funds and HRSA workforce programs to support Whole Health training, certifications, and placements across clinical and community settings.

- State Action. As a part of initiatives to grow the health workforce, state governments should expand the definition of a “health professional” to include Whole Health practitioners. Further, states can leverage their role as a licensure for professionals by creating a “whole health” licensing process that recognizes professionals that meet evidence-based standards for Whole Health.

Recommendation 4. Build a National Learning and Research Infrastructure.

Whole Health programs across the country are proving effective, but lessons remain siloed. A coordinated national system should link evidence, evaluation, and implementation so that successful models can scale quickly and sustainably.

- Federal Executive Action. Direct the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, National Institutes of Health, and partner agencies (VA, HUD, USDA) to run pragmatic trials and cost-effectiveness studies of Whole Health interventions that measure well-being across clinical, biomedical, behavioral, and social domains. The federal government should also embed Whole Health frameworks into government-wide research agendas to sustain a culture of evidence-based improvement.

- U.S. Congressional Action. Charter a quasi-governmental entity, modeled on Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), to coordinate Whole Health demonstration sites and research. This new entity should partner with CMMI, HRSA and VA to test Whole Health payment and delivery models under real-world conditions. This entity should also establish an interagency team as well as state network to address payment, regulatory, and privacy barriers identified by sites and pilots.

- State Action. Partner with federal agencies through innovation waivers (e.g. 1115 waivers and 1332 waivers) and learning collaboratives to test Whole Health models and share data across state systems and with the federal government.

Conclusion

The United States spends more on health care than any other nation yet delivers poorer outcomes. Whole Health offers a proven path to reverse this trend, reframing care around prevention, purpose, and integration across health and social systems. Embedding Whole Health as the operating system for America’s health requires three shifts: (1) redefining the purpose from treating disease to optimizing health and well-being; (2) restructuring care to empower, equip, and treat through team-based and community-linked approaches; and (3) rebalancing control from expert-driven systems to partnerships guided by what matters most to people and communities. Federal and state leaders have the opportunity to turn scattered Whole Health pilots to a coordinated national strategy. The cost of inaction is continued fragmentation; the reward of action is a healthier and more resilient nation.

This memo produced as part of Strengthening Pathways to Disease Prevention and Improved Health Outcomes.

Both approaches emphasize caring for people as integrated beings rather than as a collection of diseases, but they differ in scope and application. Whole Person Health, as used by NIH, focuses on the biological, psychological, and behavioral systems within an individual—it is primarily a research framework for understanding health across body systems. Whole Health is a systems framework that extends beyond the individual to include families, communities, and environments. It integrates medical care, behavioral health, public health, and social support around what matters most to each person. In short, Whole Person Health is about how the body and mind work together; Whole Health is about how health, social, and community systems work together to create the conditions for well-being. Policymakers can use Whole Health to guide financing, workforce, and infrastructure reforms that translate Whole Person Health science into everyday practice.

Integrative Health combines evidence-based conventional and complementary approaches such as mindfulness, acupuncture, yoga, and nutrition to support healing of the whole person. Whole Health extends further. It includes prevention, self-care, and personal agency, and moves beyond the clinic to connect medical care with social, behavioral, and community dimensions of health. Whole Health uses integrative approaches when evidence supports them, but it is ultimately a systems model that aligns health, social, and community supports around what matters most to people. For policymakers, it provides a structure for integrating clinical and community services within financing and workforce strategies.

They share a common foundation but differ in scope and audience. The VA Whole Health System, developed by the Department of Veterans Affairs, is an operational model, a way of delivering care that helps veterans identify what matters most, supports self-care and skill building, and provides team-based clinical treatment. The National Academies’ Whole Health framework builds on the VA’s experience and expands it to the national level. It is a policy and systems framework that applies Whole Health principles across all populations and connects health care with public health, behavioral health, and community systems. In short, the VA model shows how Whole Health works in practice, while the National Academies framework shows how it can guide national policy and system alignment.

Poison in our Communities: Impacts of the Nuclear Weapons Industry across America

In 1942, the United States formally began the Manhattan Project, which led to the production, testing, and use of nuclear weapons. In August 1945, the United States dropped two nuclear weapons on Japanese cities, killing around 200,000 people by the end of 1945 and leaving survivors with cancer, leukemia and other illnesses caused by radiation exposure. While this was their only use in wartime, states have detonated nuclear weapons many times since for testing purposes, producing radioactive fallout. Many U.S. nuclear weapons production activities, including the mining of uranium and testing of the weapons themselves, have occurred outside of the continental United States. Notably, explosive testing in the Pacific islands and ocean spread radioactive fallout to Marshallese, Japanese, and Gilbertese people, forcibly displacing entire communities and producing intergenerational illnesses.

Much of the scholarship surrounding the effects of nuclear weapons on environmental and human health is framed within a potential detonation scenario. For example, studies have shown that even a regional nuclear war would cause millions of immediate deaths and trigger a “nuclear winter,” a shift in the climate that would disrupt agricultural production, thus killing hundreds of millions more through starvation. Additionally, in 2024, the United Nations General Assembly voted to create an independent scientific panel to study the health, environmental and economic consequences of nuclear war. While such research is crucial for understanding the consequences of nuclear weapons use, nuclear weapons are built, maintained, and deployed everyday, impacting communities at every stage even before detonation. Studying only the predictive futures of the use of a nuclear weapon in war is insufficient in understanding nuclear weapons’ holistic humanitarian impact. According to former Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, “The heart of American deterrence is the people who protect us and our allies. Here at STRATCOM, you proudly stand up—day in and day out and around the clock—to defend us from catastrophe and to build a safer and more peaceful future. So let us always ensure that the most dangerous weapons ever produced by human science are managed with the greatest responsibility ever produced by human government.” Nuclear deterrence theory contends that a retaliatory nuclear strike is so threatening that an adversary will not attack in the first place. Thus, nuclear advocates often suggest that these weapons protect American citizens and the U.S. homeland. This report demonstrates, however, that the creation and sustainment of the nuclear deterrent harms members of the American public. As the United States continues nuclear modernization on all legs of its nuclear triad through the creation of new variants of warheads, missiles, and delivery platforms, examining the effects of nuclear weapons production on the public is ever more pressing.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Labor

Extreme heat is a major occupational hazard with far-reaching impacts on the national economy as well as worker health and safety. Extreme heat costs an estimated $100 billion per year in lost productivity, and causes an average of at least 3,389 heat-related injuries and 33 heat-related fatalities annually – numbers that are likely vast undercounts. To protect workers, Congress must mandate a federal heat standard, retain federal workers with expertise in heat stress management strategies, and establish Centers of Excellence to support research, training, and sector-specific mitigation strategies. Through investments in infrastructure for heat safety, Congress can save lives, protect the economy, and enhance resilience nationwide.

Heat-Related Risks are Heightened in Many Work Environments

Extreme heat puts workers of all types at risk: OSHA has documented hospitalizations and heat-related deaths in close to 275 industries. Some work environments present extreme heat risk, particularly those involving high exposures to the outdoors and limited access to cooling. With roughly one in three U.S. employees regularly working outdoors, a large share of the workforce is at elevated risk during summer months. Indoor workers also face high exposure, especially in kitchens, warehouses, manufacturing plants, and other poorly ventilated environments because heat and humidity easily build up in enclosed spaces without adequate air flow and climate-control.

Business and Economic Impacts of High Heat Exposure in the Workplace

On top of the $100 billion in direct annual losses, high temperatures are also linked to increased healthcare costs for employers and workers’ compensation claims, with claim frequencies rising by up to 10% during temperature extremes. Some industries are more exposed than others; for example, agriculture, construction, and utility companies face twice the risk of incurring increased healthcare claims due to extreme weather and other environmental conditions. This growing number of claims increases companies’ experience modification rates, which insurers use as a key factor for calculating higher future premiums. Higher premiums translate to greater insurance and overall operating costs, which is especially burdensome for small and low-margin businesses. Despite all these risks, many employers continue to underestimate the financial burden of extreme heat and other weather-related health impacts.

Many Military Personnel and Federal Workers Face Above-Average Risks of Heat-Related Illness

Military personnel, federal law enforcement officers, border patrol officers, wildland firefighters, federal transportation workers like railroad inspectors, and postal employees are all in positions that require long, labor-intensive hours outdoors, raising the risk for heat-related illness. In 2024, heat-related illnesses were among the top five most reported medical events among U.S. active duty service members. Without consistent standards in place to protect these workers from extreme heat, military and other federal operations will continue to be vulnerable to disruption and reduced workforce capacity.

Advancing Solutions: Establish a Strong Federal Heat Standard and Sector-Specific Centers of Excellence for Heat Workplace Safety

To begin to address heat-related injuries and illnesses in workplaces, OSHA in 2022 established the National Emphasis Program (NEP) on Outdoor and Indoor Heat-Related Hazards, which remains in effect until April 2026. As of 2025, OSHA reports that this NEP has conducted nearly 7,000 inspections connected to heat risks, which lead to 60 heat citations and nearly 1,400 “hazard alert” letters being sent to employers.

However, in the absence of a federal mandate for effective heat safety practices, most workplaces rely on voluntary guidance that is not tailored to specific job conditions, backed by consistent data, or subject to enforcement. This puts both workers and businesses at risk. OSHA’s proposed Heat Injury and Illness Prevention rule would be a critical step forward to establishing common-sense baseline protections. According to the agency’s projections, compliance with this standard could prevent thousands of heat-related illnesses and deaths. The projected benefits from reduced fatalities, illness, and injury amount to $9.18 billion per year. Importantly, this action has broad public backing: 90% of American voters support the implementation of federal protections from extreme heat in the workplace.

Congress should act swiftly to ensure OSHA finalizes and enforces a strong, evidence-based heat standard. To do this effectively, it is essential that funding for experts at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) is retained in the FY26 budget request, as these critical workers develop criteria for recommended standards on occupational heat stress. These experts have been impacted by reductions in force at NIOSH, and as of July 2025 have not been brought back by the agency.

Some employers have raised concerns about the technical and financial feasibility of the proposed rule. To address these concerns, Congress should pair regulation with practical support by creating federally funded, sector-specific Centers of Excellence (CoEs)for Heat Workplace Safety. These Centers would develop and implement evidence-based solutions tailored to different work environments, such as agriculture and construction. The CoE approach includes comprehensive data collection at worksites that form the basis of occupational safety and health protocols best practices and policies to enhance productivity, prevent injury and illness, and ensure a return on investment. Once strategies are developed, CoEs implement them, track their impact, and work with workers, employers, and cross-sector partners to ensure long-term success.

By leveraging advanced technology, predictive analytics, and continuously updated industry standards, CoEs can help modernize OSHA regulations and make them more aligned with current workplace realities that go beyond simple compliance or post-injury responses. Federal agencies and other industries with sizable workforces that receive government contracts are key places to develop best practices, technologies, and public-private partnerships for these interventions, all while reducing fiscal risk to the federal government.

Advance AI with Cleaner Air and Healthier Outcomes

Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming industries, driving innovation, and tackling some of the world’s most pressing challenges. Yet while AI has tremendous potential to advance public health, such as supporting epidemiological research and optimizing healthcare resource allocation, the public health burden of AI due to its contribution to air pollutant emissions has been under-examined. Energy-intensive data centers, often paired with diesel backup generators, are rapidly expanding and degrading air quality through emissions of air pollutants. These emissions exacerbate or cause various adverse health outcomes, from asthma to heart attacks and lung cancer, especially among young children and the elderly. Without sufficient clean and stable energy sources, the annual public health burden from data centers in the United States is projected to reach up to $20 billion by 2030, with households in some communities located near power plants supplying data centers, such as those in Mason County, WV, facing over 200 times greater burdens than others.

Federal, state, and local policymakers should act to accelerate the adoption of cleaner and more stable energy sources and address AI’s expansion that aligns innovation with human well-being, advancing the United States’ leadership in AI while ensuring clean air and healthy communities.

Challenge and Opportunity

Forty-six percent of people in the United States breathe unhealthy levels of air pollution. Ambient air pollution, especially fine particulate matter (PM2.5), is linked to 200,000 deaths each year in the United States. Poor air quality remains the nation’s fifth highest mortality risk factor, resulting in a wide range of immediate and severe health issues that include respiratory diseases, cardiovascular conditions, and premature deaths.

Data centers consume vast amounts of electricity to power and cool the servers running AI models and other computing workloads. According to the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, the growing demand for AI is projected to increase the data centers’ share of the nation’s total electricity consumption to as much as 12% by 2028, up from 4.4% in 2023. Without enough sustainable energy sources like nuclear power, the rapid growth of energy-intensive data centers is likely to exacerbate ambient air pollution and its associated public health impacts.

Data centers typically rely on diesel backup generators for uninterrupted operation during power outages. While the total operation time for routine maintenance of backup generators is limited, these generators can create short-term spikes in PM2.5, NOx, and SO2 that go beyond the baseline environmental and health impacts associated with data center electricity consumption. For example, diesel generators emit 200–600 times more NOx than natural gas-fired power plants per unit of electricity produced. Even brief exposure to high-level NOx can aggravate respiratory symptoms and hospitalizations. A recent report to the Governor and General Assembly of Virginia found that backup generators at data centers emitted approximately 7% of the total permitted pollution levels for these generators in 2023. Based on the Environmental Protection Agency’s COBRA modeling tool, the public health cost of these emissions in Virginia is estimated at approximately $200 million, with health impacts extending to neighboring states and reaching as far as Florida. In Memphis, Tennessee, a set of temporary gas turbines powering a large AI data center, which has not undergone a complete permitting process, is estimated to emit up to 2,000 tons of NOx annually. This has raised significant health concerns among local residents and could result in a total public health burden of $160 million annually. These public health concerns coincide with a paradigm shift that favors dirty energy and potentially delays sustainability goals.

In 2023 alone, air pollution attributed to data centers in the United States resulted in an estimated $5 billion in health-related damages, a figure projected to rise up to $20 billion annually by 2030. This projected cost reflects an estimated 1,300 premature deaths in the United States per year by the end of the decade. While communities near data centers and power plants bear the greatest burden, with some households facing over 200 times greater impacts than others, the health impacts of these facilities extend to communities across the nation. The widespread health impacts of data centers further compound the already uneven distribution of environmental costs and water resource stresses imposed by AI data centers across the country.

While essential for mitigating air pollution and public health risks, transitioning AI data centers to cleaner backup fuels and stable energy sources such as nuclear power presents significant implementation hurdles, including lengthy permitting processes. Clean backup generators that match the reliability of diesel remain limited in real-world applications, and multiple key issues must be addressed to fully transition to cleaner and more stable energy.

While it is clear that data centers pose public health risks, comprehensive evaluations of data center air pollution and related public health impacts are essential to grasp the full extent of the harms these centers pose, yet often remain absent from current practices. Washington State conducted a health risk assessment of diesel particulate pollution from multiple data centers in the Quincy area in 2020. However, most states lack similar evaluations for either existing or newly proposed data centers. To safeguard public health, it is essential to establish transparency frameworks, reporting standards, and compliance requirements for data centers, enabling the assessment of PM2.5, NOₓ, SO₂, and other harmful air pollutants, as well as their short- and long-term health impacts. These mechanisms would also equip state and local governments to make informed decisions about where to site AI data center facilities, balancing technological progress with the protection of community health nationwide.

Finally, limited public awareness, insufficient educational outreach, and a lack of comprehensive decision-making processes further obscure the potential health risks data centers pose to public health. Without robust transparency and community engagement mechanisms, communities housing data center facilities are left with little influence or recourse over developments that may significantly affect their health and environment.

Plan of Action

The United States can build AI systems that not only drive innovation but also promote human well-being, delivering lasting health benefits for generations to come. Federal, state, and local policymakers should adopt a multi-pronged approach to address data center expansion with minimal air pollution and public health impacts, as outlined below.

Federal-level Action

Federal agencies play a crucial role in establishing national standards, coordinating cross-state efforts, and leveraging federal resources to model responsible public health stewardship.

Recommendation 1. Incorporate Public Health Benefits to Accelerate Clean and Stable Energy Adoption for AI Data Centers

Congress should direct relevant federal agencies, including the Department of Energy (DOE), the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), to integrate air pollution reduction and the associated public health benefits into efforts to streamline the permitting process for more sustainable energy sources, such as nuclear power, for AI data centers. Simultaneously, federal resources should be expanded to support research, development, and pilot deployment of alternative low-emission fuels for backup generators while ensuring high reliability.

- Public Health Benefit Quantification. Direct the EPA, in coordination with DOE and public health agencies, to develop standardized methods for estimating the public health benefits (e.g., avoided premature deaths, hospital visits, and economic burden) of using cleaner and more stable energy sources for AI data centers. Require lifecycle emissions modeling of energy sources and translate avoided emissions into quantitative health benefits using established tools such as the EPA’s BenMAP. This should:

- Include modeling of air pollution exposure and health outcomes (e.g., using tools like EPA’s COBRA)

- Incorporate cumulative risks from regional electricity generation and local backup generator emissions

- Account for spatial disparities and vulnerable populations (e.g., children, the elderly, and disadvantaged communities)

- Evaluate both short-term (e.g., generator spikes) and long-term (e.g., chronic exposure) health impacts

- Preferential Permitting. Instruct the DOE to prioritize and streamline permitting for cleaner energy projects (e.g., small modular reactors, advanced geothermal) that demonstrate significant air pollution reduction and health benefits in supporting AI data center infrastructures. Develop a Clean AI Permitting Framework that allows project applicants to submit health benefit assessments as part of the permitting package to justify accelerated review timelines.

- Support for Cleaner Backup Systems. Expand DOE and EPA R&D programs to support pilot projects and commercialization pathways for alternative backup generator technologies, including hydrogen combustion systems and long-duration battery storage. Provide tax credits or grants for early adopters of non-diesel backup technologies in AI-related data center facilities.

- Federal Guidance & Training. Provide technical assistance to state and local agencies to implement the protocol, and fund capacity-building efforts in environmental health departments.

Recommendation 2. Establish a Standardized Emissions Reporting Framework for AI Data Centers

Congress should direct the EPA, in coordination with the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), to develop and implement a standardized reporting framework requiring data centers to publicly disclose their emissions of air pollutants, including PM₂.₅, NOₓ, SO₂, and other hazardous air pollutants associated with backup generators and electricity use.

- Multi-Stakeholder Working Group. Task EPA with convening a multi-stakeholder working group, including representatives from NIST, DOE, state regulators, industry, and public health experts, to define the scope, metrics, and methodologies for emissions reporting.

- Standardization. Develop a federal technical standard that specifies:

- Types of air pollutants that should be reported

- Frequency of reporting (e.g., quarterly or annually)

- Facility-specific disclosures (including generator use and power source profiles)

- Geographic resolution of emissions data

- Public access and data transparency protocols

State-level Action

Recommendation 1. State environmental and public health departments should conduct a health impact assessment (HIA) before and after data center construction to evaluate discrepancies between anticipated and actual health impacts for existing and planned data center operations. To maintain and build trust, HIA findings, methodologies, and limitations should be publicly available and accessible to non-technical audiences (including policymakers, local health departments, and community leaders representing impacted residents), thereby enhancing community-informed action and participation. Reports should focus on the disparate impact between rural and urban communities, with particular attention to overburdened communities that have under-resourced health infrastructure. In addition, states should coordinate HIA and share findings to address cross-boundary pollution risks. This includes accounting for nearby communities across state lines, considering that jurisdictional borders should not constrain public health impacts and analysis.

Recommendation 2. State public health departments should establish a state-funded program that offers community education forums for affected residents to express their concerns about how data centers impact them. These programs should emphasize leading outreach, engaging communities, and contributing to qualitative analysis for HIAs. Health impact assessments should be used as a basis for informed community engagement.

Recommendation 3. States should incorporate air pollutant emissions related to data centers into their implementation of the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and the development of State Implementation Plans (SIPs). This ensures that affected areas can meet standards and maintain their attainment statuses. To support this, states should evaluate the adequacy of existing regulatory monitors in capturing emissions related to data centers and determine whether additional monitoring infrastructure is required.

Local-level Action

Recommendation 1. Local governments should revise zoning regulations to include stricter and more explicit health-based protections to prevent data center clustering in already overburdened communities. Additionally, zoning ordinances should address colocation factors and evaluate potential cumulative health impacts. A prominent example is Fairfax County, Virginia, which updated its zoning ordinance in September 2024 to regulate the proximity of data centers to residential areas, require noise pollution studies prior to construction, and establish size thresholds. These updates were shaped through community engagement and input.

Recommendation 2. Local governments should appoint public health experts to the zoning boards to ensure data center placement decisions reflect community health priorities, thereby increasing public health expert representation on zoning boards.

Conclusion

While AI can revolutionize industries and improve lives, its energy-intensive nature is also degrading air quality through emissions of air pollutants. To mitigate AI’s growing air pollution and public health risks, a comprehensive assessment of AI’s health impact and transitioning AI data centers to cleaner backup fuels and stable energy sources, such as nuclear power, are essential. By adopting more informed and cleaner AI strategies at the federal and state levels, policymakers can mitigate these harms, promote healthier communities, and ensure AI’s expansion aligns with clean air priorities.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Rural Communities

46 million rural Americans face mounting risks from temperature extremes that threaten workforce productivity, raise business operational costs, and strain critical public services. Though extreme heat is often portrayed in research and the media as an urban issue, almost every state in the contiguous U.S. has rural communities with above-average rates of vulnerability to extreme heat. To protect rural America, Congress must address extreme heat’s impacts by repairing rural health systems, strengthening the preparedness of rural businesses, and hardening rural energy infrastructure.

Extreme heat exacerbates rural communities’ unique health vulnerabilities

On average, Americans living in rural areas are twice as likely as those in urban areas to have pre-existing health conditions, like heart disease, diabetes, and asthma, that make them more sensitive to heat-related illness and death. Further compounding the risk, rural places also have larger populations of underinsured and uninsured people than urban areas, with 1 in 6 people lacking insurance.

Limited healthcare infrastructure in rural places worsens these vulnerabilities. Rural areas have higher shortages of healthcare professionals who provide primary care, mental health, and dental services than urban areas. Over the last decade, 100 rural hospitals have closed, and hundreds more are vulnerable to closure. Finally, many rural communities do not have public health departments, and those that do are underfunded and understaffed. Because public health systems and healthcare professionals are the first responders to extreme heat, rural residents are severely underprepared.

Congress should provide flexible resources and technical assistance to rural hospitals to prepare for emerging threats like extreme heat. Additionally, Congress should continue to enable the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services to provide loans or grant assistance to help rural residents retain access to health services and improve the financial position of rural hospitals and clinics. And because Medicaid expansion correlates with better rural hospital financial performance and fewer closures, Congress should invest in Medicaid to protect rural healthcare access.

Extreme heat puts rural businesses and workers at risk

Rural economic health relies on the outdoors (e.g., recreation tourism) and outdoor labor (e.g., agriculture and oil and gas extraction). Extreme heat in many of these places makes it dangerous to be outside, which impacts worker productivity and local business revenues. Indoor workers in facilities like manufacturing plants, food processing, and warehouses also face heat-related safety threats due to the presence of heat-producing machines and poorly ventilated buildings with limited cooling. These facilities are rapidly growing components of rural economies, as these sectors employ almost 1 in 5 rural workers.

Simple protections like water, rest, shade, and cooling can improve productivity and generate returns on investments. But small-to-medium rural enterprises need support to adopt affordable cooling systems, shade and passive cooling infrastructure, and worker safety measures that reduce heat-related disruptions. Congress should help rural businesses reduce heat’s risks by appropriating funding to support workplace heat risk reduction and practical training on worker protections. Additionally, Congress should require OSHA to finalize a federal workplace heat standard.

Extreme heat threatens rural energy security

When a power outage happens during a severe extreme heat event, the chance of heat-related illness and death increases exponentially. Extreme heat strains power infrastructure, increasing the risk of power outages. This risk is particularly acute for rural communities, which have limited resources, older infrastructure, and significantly longer waits to restore power after an outage.

Weatherized housing and indoor infrastructure are one of the key protective factors against extreme heat, especially during outages. Yet rural areas often have a higher proportion of older, substandard homes. Manufactured and mobile homes, for example, compose 15% of the rural housing stock and are the one of the most at-risk housing types for extreme heat exposure. When the power is on, rural residents spend 40% more of their income on their energy bills than their urban counterparts. Rural residents in manufactured housing spend an alarming 75% more. Energy debt can force people to choose between paying for life-saving energy or food and key medications, compounding poverty and health outcomes.

To drive the energy independence and economic resilience of rural America, Congress should support investments in energy-efficient and resilient cooling technologies, weatherized homes, localized energy solutions like microgrids, and grid-enhancing technologies.

Economic Impacts of Extreme Heat: Energy

As temperatures rise, the strain on energy infrastructure escalates, creating vulnerabilities for the efficiency of energy generation, grid transmission, and home cooling, which have significant impacts on businesses, households, and critical services. Without action, energy systems will face growing instability, infrastructure failures will persist, and utility burdens will increase. The combined effects of extreme heat cost our nation over $162 billion in 2024 – equivalent to nearly 1% of the U.S. GDP.

The federal government needs to prepare energy systems and the built environment through strategic investments in energy infrastructure — across energy generation, transmission, and use. Doing so includes ensuring electric grids are prepared for extreme heat by establishing an interagency HeatSmart Grids Initiative to assess the risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency responses. Congress should retain and expand home energy rebates, tax credits, and the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) to enable deep retrofits that prepare homes against power outages and cut cooling costs, along with extending the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC) to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation.

Challenge & Opportunity: Grid Security

Extreme Heat Reduces Energy Generation and Transmission Efficiency

During a heatwave, the energy grid faces not only surges in demand but also decreased energy production and reduced transmission efficiency. For instance, turbines can become up to 25% less efficient in high temperatures. Other energy sources are also impacted: solar power, for example, produces less electricity as temperatures rise because high heat slows the flow of electrical current. Additionally, transmission lines lose up to 5.8% of their capacity to carry electricity as temperatures increase, resulting in reliability issues such as rolling blackouts. These combined effects slow down the entire energy cycle, making it harder for the grid to meet growing demand and causing power disruptions.

Rising Demand and Grid Load Increase the Threat of Power Outages

Electric grids are under unprecedented strain as record-high temperatures drive up air conditioning use, increasing energy demand in the summer. Power generation and transmission are impeded when demand outpaces supply, causing communities and businesses to experience blackouts. According to data from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), between 2024 and 2028, an alarming 300 million people across the United States could face power outages. Texas, California, the Southwest, New England, and much of the Midwest are among the states and regions most at risk of energy emergencies during extreme conditions, according to 2024 NERC data.

Data center build-out, driven by growing demand for artificial intelligence, cloud services, and big data analytics, further adds stress to the grid. Data centers are estimated to consume 9% of US annual electricity generation by 2030. With up to 40% of data centers’ total yearly energy consumption driven by cooling systems, peak demand during the hottest days of the year puts demand on the U.S. electric grid and increases power outage risk.

Power outages bear significant economic costs and put human lives at severe risk. To put this into perspective, a concurrent heat wave and blackout event in Phoenix, Arizona, could put 1 million residents at high risk of heat-related illness, with more than 50% of the city’s population requiring medical care. As we saw with 2024’s Hurricane Beryl, more than 2 million Texans lost power during a heatwave, resulting in up to $1.3 billion in damages to the electric infrastructure in the Houston area and significant public health and business impacts. The nation must make strategic investments to ensure energy reliability and foster the resilience of electric grids to weather hazards like extreme heat.

Advancing Solutions for Energy Systems and Grid Security

Investments in resilience pay dividends, with every federal dollar spent on resilience returning $6 in societal benefits. For example, the DOE Grid Resilience State and Tribal Formula Grants, established by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), have strengthened grid infrastructure, developed innovative technologies, and improved community resilience against extreme weather. It is essential that funds for this program, as well as other BIL and Inflation Reduction Act initiatives, continue to be disbursed.

To build heat resilience in communities across this nation, Congress must establish the HeatSmart Grids Initiative as a partnership between DOE, FEMA, HHS, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), NERC, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). This program should (i) perform national audits of energy security and building-stock preparedness for outages, (ii) map energy resilience assets such as long-term energy storage and microgrids, (iii) leverage technologies for minimizing grid loads such as smart grids and virtual power plants, and (iv) coordinate protocols with FEMA’s Community Lifelines and CISA’s Critical Infrastructure for emergency response. This initiative will ensure electric grids are prepared for extreme heat, including the risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency and public health responses.

Challenge & Opportunity: Increasing Household and Business Energy Costs

As temperatures rise, so do household and business energy bills to cover cooling costs. This escalation can be particularly challenging for low-income individuals, schools, and small businesses operating on thin margins. For businesses, especially small enterprises, power outages, equipment failures, and interruptions in the supply chain become more frequent and severe due to extreme weather, negatively affecting production and distribution. One in six U.S. households (21.2 million people) find themselves behind on their energy bills, which increases the risk of utility shut-offs. One in five households report reducing or forgoing food and medicine to pay their energy bills. Families, school districts, and business owners need active and passive cooling approaches to meet demands without increasing costs.

Advancing Solutions for Businesses, Households, and Vital Facilities

Affordably cooled homes, businesses, and schools are crucial to sustaining our economy. To prepare the nation’s housing and infrastructure for rising temperatures, the federal government should:

- Expand the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, existing rebates and tax credits (including HER, HEAR, 25C, 179D, 45L, Direct Pay) to include passive cooling technology such as cool walls, pavements, and roofs (H.R. 9894). Revise 25C to be refundable at purchase to increase accessibility to low-income households.

- Authorize a Weatherization Readiness Program (H.R. 8721) to address structural, plumbing, roofing, and electrical issues and environmental hazards with dwelling units to make them eligible for WAP.

- Direct the DOE to work with its WAP contractors to ensure home energy audits consider passive cooling interventions, such as cool walls and roofs, strategically placing trees to provide shading and high-efficiency windows.

- Extend the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC) to include (i) the development of codes and metrics for sustainable and passive cooling, shade, materials selection, and thermal comfort and (ii) the identification of opportunities to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation. Partner with the National Institute of Standards and Technology to create an Extreme Heat clearinghouse for model building codes.

- Authorize an extension to the DOE Renew America’s Schools Program to continue funding cost-saving, energy-efficient upgrades in K-12 schools.

- Provide supportive appropriations to heat-critical programs at DOE, including: the Affordable Home Energy Shot, State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy (DOE), and the Home Energy Rebates program

The Federation of American Scientists: Who We Are

At the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), we envision a world where the federal government deploys cutting-edge science, technology, ideas, and talent to solve and address the impacts of extreme heat. We bring expertise in embedding science, data, and technology into government decision-making and a strong network of subject matter experts in extreme heat, both inside and outside of government. Through our 2025 Heat Policy Agenda and broader policy library, FAS is positioned to help ensure that public policy meets the challenges of living with extreme heat.

Consider FAS a resource for…

- Understanding evidence-based policy solutions

- Directing members and staff to relevant academic research

- Connecting with issue experts to develop solutions that can immediately address the impacts of extreme heat

We are tackling this crisis with initiative, creativity, experimentation, and innovation, serving as a resource on environmental health policy issues. Feel free to always reach out to us:

Emerging Technologies

Resilient Communities,

Extreme Weather,

Inclusive Innovation & Technology

Reforming the Federal Advisory Committee Landscape for Improved Evidence-based Decision Making and Increasing Public Trust

Federal Advisory Committees (FACs) are the single point of entry for the American public to provide consensus-based advice and recommendations to the federal government. These Advisory Committees are composed of experts from various fields who serve as Special Government Employees (SGEs), attending committee meetings, writing reports, and voting on potential government actions.

Advisory Committees are needed for the federal decision-making process because they provide additional expertise and in-depth knowledge for the Agency on complex topics, aid the government in gathering information from the public, and allow the public the opportunity to participate in meetings about the Agency’s activities. As currently organized, FACs are not equipped to provide the best evidence-based advice. This is because FACs do not meet transparency requirements set forth by GAO: making pertinent decisions during public meetings, reporting inaccurate cost data, providing official meeting documents publicly available online, and more. FACs have also experienced difficulty with recruiting and retaining top talent to assist with decision making. For these reasons, it is critical that FACs are reformed and equipped with the necessary tools to continue providing the government with the best evidence-based advice. Specifically, advice as it relates to issues such as 1) decreasing the burden of hiring special government employees 2) simplifying the financial disclosure process 3) increasing understanding of reporting requirements and conflict of interest processes 4) expanding training for Advisory Committee members 5) broadening the roles of Committee chairs and designated federal officials 6) increasing public awareness of Advisory Committee roles 7) engaging the public outside of official meetings 8) standardizing representation from Committee representatives 9) ensuring that Advisory Committees are meeting per their charters and 10) bolstering Agency budgets for critical Advisory Committee issues.

Challenge and Opportunity

Protecting the health and safety of the American public and ensuring that the public has the opportunity to participate in the federal decision-making process is crucial. We must evaluate the operations and activities of federal agencies that require the government to solicit evidence-based advice and feedback from various experts through the use of federal Advisory Committees (FACs). These Committees are instrumental in facilitating transparent and collaborative deliberation between the federal government, the advisory body, and the American public and cannot be done through the use of any other mechanism. Advisory Committee recommendations are integral to strengthening public trust and reinforcing the credibility of federal agencies. Nonetheless, public trust in government has been waning and efforts should be made to increase public trust. Public trust is known as the pillar of democracy and fosters trust between parties, particularly when one party is external to the federal government. Therefore, the use of Advisory Committees, when appropriately used, can assist with increasing public trust and ensuring compliance with the law.

There have also been many success stories demonstrating the benefits of Advisory Committees. When Advisory Committees are appropriately staffed based on their charge, they can decrease the workload of federal employees, assist with developing policies for some of our most challenging issues, involve the public in the decision-making process, and more. However, the state of Advisory Committees and the need for reform have been under question, and even more so as we transition to a new administration. Advisory Committees have contributed to the improvement in the quality of life for some Americans through scientific advice, as well as the monitoring of cybersecurity. For example, an FDA Advisory Committee reviewed data and saw promising results for the treatment of sickle cell disease (SCD) which has been a debilitating disease with limited treatment for years. The Committee voted in favor of gene therapy drugs Casgevy and Lyfgenia which were the first to be approved by the FDA for SCD.

Under the first Trump administration, Executive Order (EO) 13875 resulted in a significant decrease in the number of federal advisory meetings. This limited agencies’ ability to convene external advisors. Federal science advisory committees met less during this administration than any prior administration, met less than what was required from their charter, disbanded long standing Advisory Committees, and scientists receiving agency grants were barred from serving on Advisory Committees. Federal Advisory Committee membership also decreased by 14%, demonstrating the issue of recruiting and retaining top talent. The disbandment of Advisory Committees, exclusion of key scientific external experts from Advisory Committees, and burdensome procedures can potentially trigger severe consequences that affect the health and safety of Americans.

Going into a second Trump administration, it is imperative that Advisory Committees have the opportunity to assist federal agencies with the evidence-based advice needed to make critical decisions that affect the American public. The suggested reforms that follow can work to improve the overall operations of Advisory Committees while still providing the government with necessary evidence-based advice. With successful implementation of the following recommendations, the federal government will be able to reduce administrative burden on staff through the recruitment, onboarding, and conflict of interest processes.

The U.S. Open Government Initiative encourages the promotion and participation of public and community engagement in governmental affairs. However, individual Agencies can and should do more to engage the public. This policy memo identifies several areas of potential reform for Advisory Committees and aims to provide recommendations for improving the overall process without compromising Agency or Advisory Committee membership integrity.

Plan of Action

The proposed plan of action identifies several policy recommendations to reform the federal Advisory Committee (Advisory Committee) process, improving both operations and efficiency. Successful implementation of these policies will 1) improve the Advisory Committee member experience, 2) increase transparency in federal government decision-making, and 3) bolster trust between the federal government, its Advisory Committees, and the public.

Streamline Joining Advisory Committees

Recommendation 1. Decrease the burden of hiring special government employees in an effort to (1) reduce the administrative burden for the Agency and (2) encourage Advisory Committee members, who are also known as special government employees (SGEs), to continue providing the best evidence-based advice to the federal government through reduced onerous procedures

The Ethics in Government Act of 1978 and Executive Order 12674 lists OGE-450 reporting as the required public financial disclosure for all executive branch and special government employees. This Act provides the Office of Government Ethics (OGE) the authority to implement and regulate a financial disclosure system for executive branch and special government employees whose duties have “heightened risk of potential or actual conflicts of interest”. Nonetheless, the reporting process becomes onerous when Advisory Committee members have to complete the OGE-450 before every meeting even if their information remains unchanged. This presents a challenge for Advisory Committee members who wish to continue serving, but are burdened by time constraints. The process also burdens federal staff who manage the financial disclosure system.

Policy Pathway 1. Increase funding for enhanced federal staffing capacity to undertake excessive administrative duties for financial reporting.

Policy Pathway 2. All federal agencies that deploy Advisory Committees can conduct a review of the current OGC-450 process, budget support for this process, and work to develop an electronic process that will eliminate the use of forms and allow participants to select dropdown options indicating if their financial interests have changed.

Recommendation 2. Create and use public platforms such as OpenPayments by CMS to (1) aid in simplifying the financial disclosure reporting process and (2) increase transparency for disclosure procedures