Biden, You Should Be Aware That Your Submarine Deal Has Costs

For more than a decade, Washington has struggled to prioritize what it calls great power competition with China — a contest for military and political dominance. President Biden has been working hard to make the pivot to Asia that his two predecessors never quite managed.

The landmark defense pact with Australia and Britain, AUKUS, that Mr. Biden announced this month is a major step to making that pivot a reality. Under the agreement, Australia will explore hosting U.S. bombers on its territory, gain access to advanced missiles and receive nuclear propulsion technology to power a new fleet of submarines.

What Is the Sole Purpose of U.S. Nuclear Weapons?

Read the full report PDF here.

Summary

- Prior to assuming office, President Biden indicated that he would establish that “the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal is to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate for—a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies.”

- Sole purpose should be understood as a central component of an integrated deterrence strategy that can effectively manage the risk of nuclear escalation in a limited conflict as well as the rising stability risks from nonnuclear weapons.

- Sole purpose could significantly reduce the risk of unintended escalation and increase the credibility of more flexible and realistic nonnuclear response options in a range of importance contingencies.

- In order to attain its intended benefits, declaratory policy must be reflected in force structure and planning.

- The president’s existing language on sole purpose provides considerable flexibility for the administration to define the doctrine, but does not itself provide clear guidance for strategy, force structure, or for related declaratory policies like “no first use.”

- Defining sole purpose is a critical task for the administration’s defense policy review.

- As a central component of an integrated defense policy that will strengthen US deterrence and assurance credibility, sole purpose should be defined at the level of the NDS.

- A sole type definition would state that the United States would consider nuclear use in response to a certain type of attack, having modest effects on a narrow set of plans but few effects on force structure.

- A sole function definition would define what is and what is not a requirement of deterrence, potentially removing certain strategic or nonstrategic roles of nuclear weapons.

Depending on how it is defined, sole purpose could have transformational effects on nearly every aspect of nuclear weapons policy or relatively modest effects. It could accommodate or incorporate a range of related policy options, like a deterrence-only posture or no first use.

- Fully implementing a sole purpose policy is critical to attaining its benefits.

- A simple declaratory statement is not a complete sole purpose policy. Because any statement is likely to be ambiguous, sole purpose should also consist of a set of presidential directives that determine how the policy will be affect force structure and planning.

- By eliminating one or more of the requirements that structure US nuclear forces, a sole function definition could potentially have significant effects on a range acquisition decisions and plans.

- If the president concludes that sole purpose has implications for force structure or force posture, the administration should ensure that these changes are made before the presidential term is concluded.

- Following a decision to adopt sole purpose, civilian officials should review existing operational plans and concepts to ensure that they comport with the president’s guidance for escalation management of a conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary.

- Embedding the policy in plans, force structure, and allied consultations is critical to achieving its benefits and reducing the risk that it is reversed by a future president, which would be highly risky.

- If defined, implemented, and communicated as a part of an effective integrated deterrence posture, sole purpose could strengthen assurance of allies.

- Some allies will be understandably apprehensive about any shift in US nuclear weapons policy in the current environment.

- Allies should be consulted closely as sole purpose is being defined, as it is released, and as it is being implemented.

In January 2021, President Biden assumed office after having made unusually explicit commitments to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in US national security strategy. In his primary articulation of his campaign’s foreign policy, Biden declared that “the sole purpose of the US nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack.”1 Since assuming office, Biden has not repeated the pledge, though his initial national security guidance and his Secretary of State have reiterated the goal of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons.2 As the Pentagon begins its review of nuclear weapons policy, Biden and his national security officials will have to determine whether to adopt sole purpose and, if so, what it means. The established language on sole purpose offers the administration considerable latitude in how it chooses to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, it could have transformative consequences for nuclear force structure and strategy, or it could end up as a rhetorical commitment that has few practical effects at all.

Though the language dates back decades, there has never been a precise or agreed definition of sole purpose. The first published use of the phrase is in a piece Albert Einstein related to the eminent journalist Raymond Swing that was published in the Atlantic in 1947. Einstein argued while the United States must stockpile the bomb, it should forswear its use. “Deterrence should be the only purpose of the stockpile of bombs.” If the United Nations were granted international control over atomic energy, as President Truman had proposed, it should be “for the sole purpose of deterring an aggressor or rebellious nations from making an atomic attack.”3 Since the idea was popularized in the 1960s, sole purpose has become a persistent staple in ongoing debates about the role of nuclear weapons, but it has rarely been attached to a precise definition or a plan to implement it.

Sole purpose is more ambiguous than other declaratory policy proposals (such as no first use) because it purports to define, or constrain, the purpose of nuclear weapons. Depending on how the terms of the statement are defined and how the statement is implemented in practice, its effects could be broad, narrow, restrictive, permissive, or ambiguous. For example, President Biden’s sole purpose language could be construed to proscribe nuclear weapons from performing a wide range of functions or from being used in wide ranges of contingencies. Slight variations in the wording of a sole purpose declaration can produce dramatically different policies and be perceived differently by allies and adversaries, who will examine the policy closely. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, sole could reduce or eliminate requirements for each piece of the triad or for nuclear use in a variety of different contingency plans.

Sole purpose is one potential option in declaratory policy, that aspect of nuclear weapons policy that publicly communicates when and why the United States would consider the use of nuclear weapons. It can be combined with or can subsume a range of other potential declaratory policy options. Because the president has sole authority to order the use of a nuclear weapon, only the president can set limits on that power. Though changes in declaratory policy should consider the views of civilian national security officials, uniformed military officials, members of Congress, US allies, and the American public, the president should provide clear guidance on how to modify US declaratory policy. Like all presidents, President Biden should provide clear guidance to the officials conducting the national defense strategy about nuclear declaratory policy.

Because sole purpose could potentially be defined in many different ways, some definitions will be better or worse. Advocates or opponents should be clear about what constitutes a better or worse definition. The administration should not accept the argument that a good definition is one that preserves existing force structure or plans, maintains ambiguity for its own sake, or comports with the preferences of certain allies or services. This piece argues that a good definition of sole purpose is one that assists with the development and implementation of a credible, integrated posture by which the United States and its allies deter aggression and nuclear use; reflects the president’s preferences about how to manage escalation in limited conflicts with nuclear-armed adversaries as well as his assessment of the requirements of deterring a major strategic attack; reduces the risk of misperception and adversary nuclear first use incentives; and can be implemented in force structure and plans so that it is resilient to leadership changes in the United States. Because the president has expressed a preference to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons, a good definition of sole purpose should help to do so in ways consistent with his preferences.

This piece examines the range of options available to officials working to define sole purpose and reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. It explores the practical implications of different definitions of sole purpose and the steps necessary to ensure that they are implemented in a way that is responsible, effective, and most likely to endure over time. There are two central arguments. First, sole purpose should not be understood as a nuclear declaratory policy but as critical component in an integrated deterrence strategy. Understood in this way, sole purpose is not only a valuable means of reducing the risk of nuclear escalation and of meeting US commitments to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons but because it is a substantive judgment about how US nuclear and nonnuclear forces can best manage escalation in a limited conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary. Second, an effective sole purpose policy cannot simply be a sentence in a paragraph on nuclear declaratory policy. If the administration is serious about attaining the benefits of sole purpose, the policy should be comprised of the declaratory statement, additional language to clarify and contextualize the policy, and a set of directives that communicate the president’s guidance for how the policy should affect force structure and plans.

Each of these arguments is critical for attaining the benefits of sole purpose and for maintaining an effective deterrence posture. Sole purpose will be a contentious idea under any circumstances. Allied governments, advocates of various aspects of the current nuclear weapons policies, and political opponents are understandably concerned about the president’s statements. Clearly defining the policy, articulating how it will strengthen an integrated deterrence policy, and moving forward with implementation will help to convince allies and many deterrence experts that sole purpose will increase rather than decrease deterrence credibility.

What Is the Sole Purpose of U.S. Nuclear Weapons?

Summary

- Prior to assuming office, President Biden indicated that he would establish that “the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal is to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate for—a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies.”

- Sole purpose should be understood as a central component of an integrated deterrence strategy that can effectively manage the risk of nuclear escalation in a limited conflict as well as the rising stability risks from nonnuclear weapons.

- Sole purpose could significantly reduce the risk of unintended escalation and increase the credibility of more flexible and realistic nonnuclear response options in a range of importance contingencies.

- In order to attain its intended benefits, declaratory policy must be reflected in force structure and planning.

- The president’s existing language on sole purpose provides considerable flexibility for the administration to define the doctrine, but does not itself provide clear guidance for strategy, force structure, or for related declaratory policies like “no first use.”

- Defining sole purpose is a critical task for the administration’s defense policy review.

- As a central component of an integrated defense policy that will strengthen US deterrence and assurance credibility, sole purpose should be defined at the level of the NDS.

- A sole type definition would state that the United States would consider nuclear use in response to a certain type of attack, having modest effects on a narrow set of plans but few effects on force structure.

- A sole function definition would define what is and what is not a requirement of deterrence, potentially removing certain strategic or nonstrategic roles of nuclear weapons.

Depending on how it is defined, sole purpose could have transformational effects on nearly every aspect of nuclear weapons policy or relatively modest effects. It could accommodate or incorporate a range of related policy options, like a deterrence-only posture or no first use.

- Fully implementing a sole purpose policy is critical to attaining its benefits.

- A simple declaratory statement is not a complete sole purpose policy. Because any statement is likely to be ambiguous, sole purpose should also consist of a set of presidential directives that determine how the policy will be affect force structure and planning.

- By eliminating one or more of the requirements that structure US nuclear forces, a sole function definition could potentially have significant effects on a range acquisition decisions and plans.

- If the president concludes that sole purpose has implications for force structure or force posture, the administration should ensure that these changes are made before the presidential term is concluded.

- Following a decision to adopt sole purpose, civilian officials should review existing operational plans and concepts to ensure that they comport with the president’s guidance for escalation management of a conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary.

- Embedding the policy in plans, force structure, and allied consultations is critical to achieving its benefits and reducing the risk that it is reversed by a future president, which would be highly risky.

- If defined, implemented, and communicated as a part of an effective integrated deterrence posture, sole purpose could strengthen assurance of allies.

- Some allies will be understandably apprehensive about any shift in US nuclear weapons policy in the current environment.

- Allies should be consulted closely as sole purpose is being defined, as it is released, and as it is being implemented.

In January 2021, President Biden assumed office after having made unusually explicit commitments to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in US national security strategy. In his primary articulation of his campaign’s foreign policy, BJoseph R. Biden, “Why American Must Lead Again: Rescuing US Foreign Policy after Trump,” Foreign Affairs 99 (2020): 64.iden declared that “the sole purpose of the US nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack.”1 Since assuming office, Biden has not repeated the pledge, though his initial national security guidance and his Secretary of State have reiterated the goal of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons.2 As the Pentagon begins its review of nuclear weapons policy, Biden and his national security officials will have to determine whether to adopt sole purpose and, if so, what it means. The established language on sole purpose offers the administration considerable latitude in how it chooses to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, it could have transformative consequences for nuclear force structure and strategy, or it could end up as a rhetorical commitment that has few practical effects at all.

Though the language dates back decades, there has never been a precise or agreed definition of sole purpose. The first published use of the phrase is in a piece Albert Einstein related to the eminent journalist Raymond Swing that was published in the Atlantic in 1947. Einstein argued while the United States must stockpile the bomb, it should forswear its use. “Deterrence should be the only purpose of the stockpile of bombs.” If the United Nations were granted international control over atomic energy, as President Truman had proposed, it should be “for the sole purpose of deterring an aggressor or rebellious nations from making an atomic attack.3 Since the idea was popularized in the 1960s, sole purpose has become a persistent staple in ongoing debates about the role of nuclear weapons, but it has rarely been attached to a precise definition or a plan to implement it.

Sole purpose is more ambiguous than other declaratory policy proposals (such as no first use) because it purports to define, or constrain, the purpose of nuclear weapons. Depending on how the terms of the statement are defined and how the statement is implemented in practice, its effects could be broad, narrow, restrictive, permissive, or ambiguous. For example, President Biden’s sole purpose language could be construed to proscribe nuclear weapons from performing a wide range of functions or from being used in wide ranges of contingencies. Slight variations in the wording of a sole purpose declaration can produce dramatically different policies and be perceived differently by allies and adversaries, who will examine the policy closely. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, sole could reduce or eliminate requirements for each piece of the triad or for nuclear use in a variety of different contingency plans.

Sole purpose is one potential option in declaratory policy, that aspect of nuclear weapons policy that publicly communicates when and why the United States would consider the use of nuclear weapons. It can be combined with or can subsume a range of other potential declaratory policy options. Because the president has sole authority to order the use of a nuclear weapon, only the president can set limits on that power. Though changes in declaratory policy should consider the views of civilian national security officials, uniformed military officials, members of Congress, US allies, and the American public, the president should provide clear guidance on how to modify US declaratory policy. Like all presidents, President Biden should provide clear guidance to the officials conducting the national defense strategy about nuclear declaratory policy.

Because sole purpose could potentially be defined in many different ways, some definitions will be better or worse. Advocates or opponents should be clear about what constitutes a better or worse definition. The administration should not accept the argument that a good definition is one that preserves existing force structure or plans, maintains ambiguity for its own sake, or comports with the preferences of certain allies or services. This piece argues that a good definition of sole purpose is one that assists with the development and implementation of a credible, integrated posture by which the United States and its allies deter aggression and nuclear use; reflects the president’s preferences about how to manage escalation in limited conflicts with nuclear-armed adversaries as well as his assessment of the requirements of deterring a major strategic attack; reduces the risk of misperception and adversary nuclear first use incentives; and can be implemented in force structure and plans so that it is resilient to leadership changes in the United States. Because the president has expressed a preference to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons, a good definition of sole purpose should help to do so in ways consistent with his preferences.

This piece examines the range of options available to officials working to define sole purpose and reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. It explores the practical implications of different definitions of sole purpose and the steps necessary to ensure that they are implemented in a way that is responsible, effective, and most likely to endure over time. There are two central arguments. First, sole purpose should not be understood as a nuclear declaratory policy but as critical component in an integrated deterrence strategy. Understood in this way, sole purpose is not only a valuable means of reducing the risk of nuclear escalation and of meeting US commitments to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons but because it is a substantive judgment about how US nuclear and nonnuclear forces can best manage escalation in a limited conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary. Second, an effective sole purpose policy cannot simply be a sentence in a paragraph on nuclear declaratory policy. If the administration is serious about attaining the benefits of sole purpose, the policy should be comprised of the declaratory statement, additional language to clarify and contextualize the policy, and a set of directives that communicate the president’s guidance for how the policy should affect force structure and plans.

Each of these arguments is critical for attaining the benefits of sole purpose and for maintaining an effective deterrence posture. Sole purpose will be a contentious idea under any circumstances. Allied governments, advocates of various aspects of the current nuclear weapons policies, and political opponents are understandably concerned about the president’s statements. Clearly defining the policy, articulating how it will strengthen an integrated deterrence policy, and moving forward with implementation will help to convince allies and many deterrence experts that sole purpose will increase rather than decrease deterrence credibility.

China Is Building A Second Nuclear Missile Silo Field

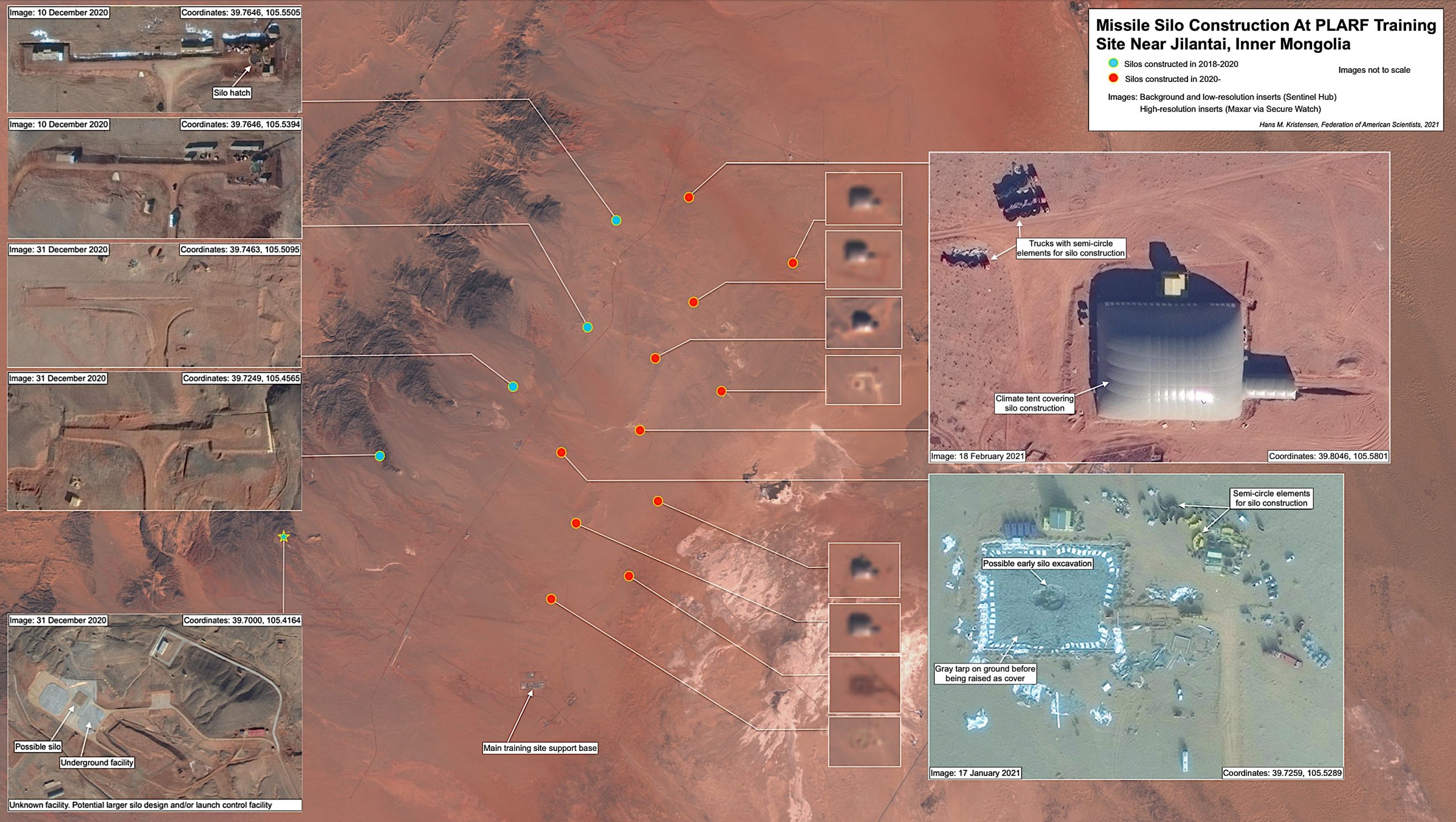

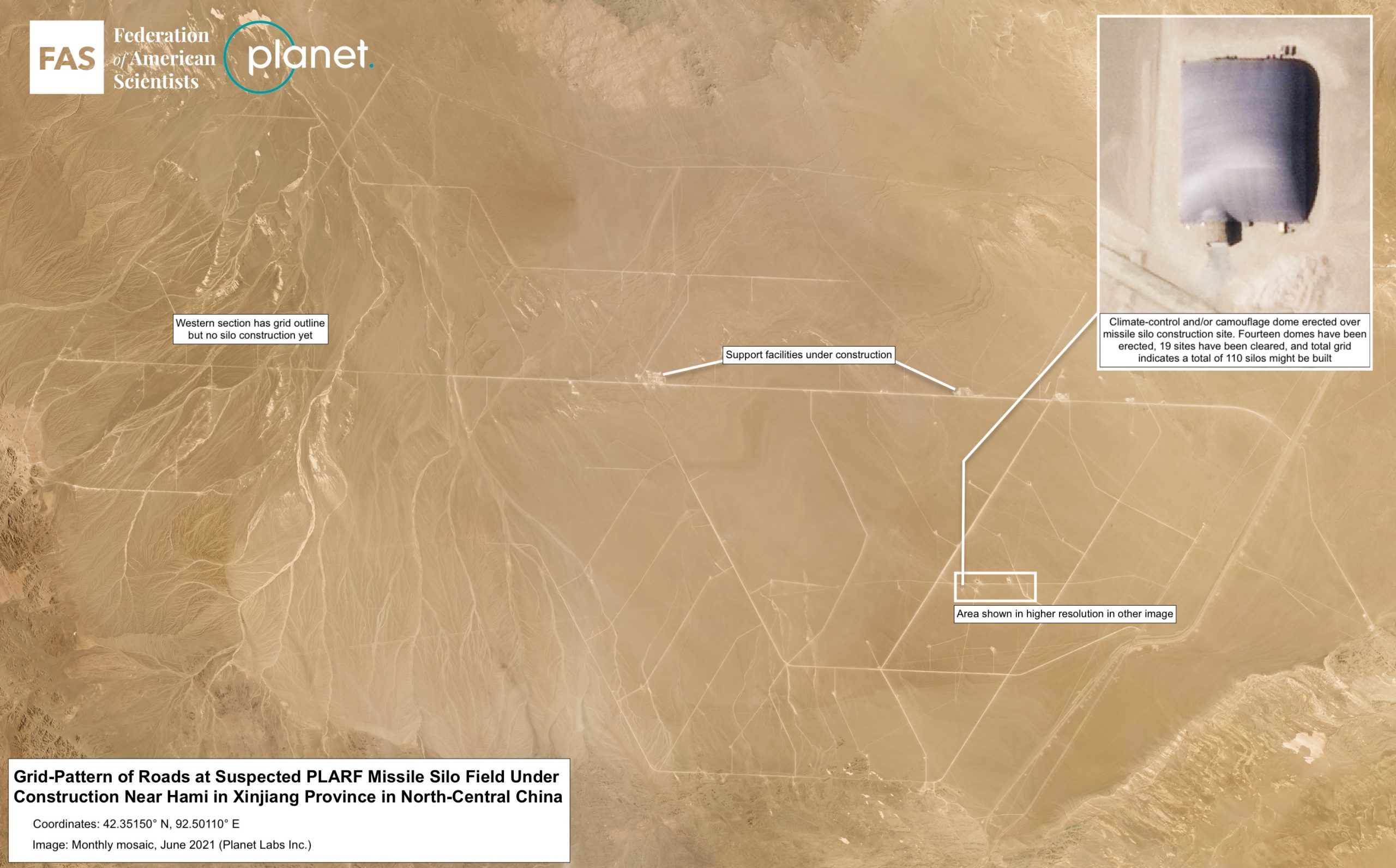

The Hami missile silo field covers an area of about 800 square kilometers and is in the early phases of construction.

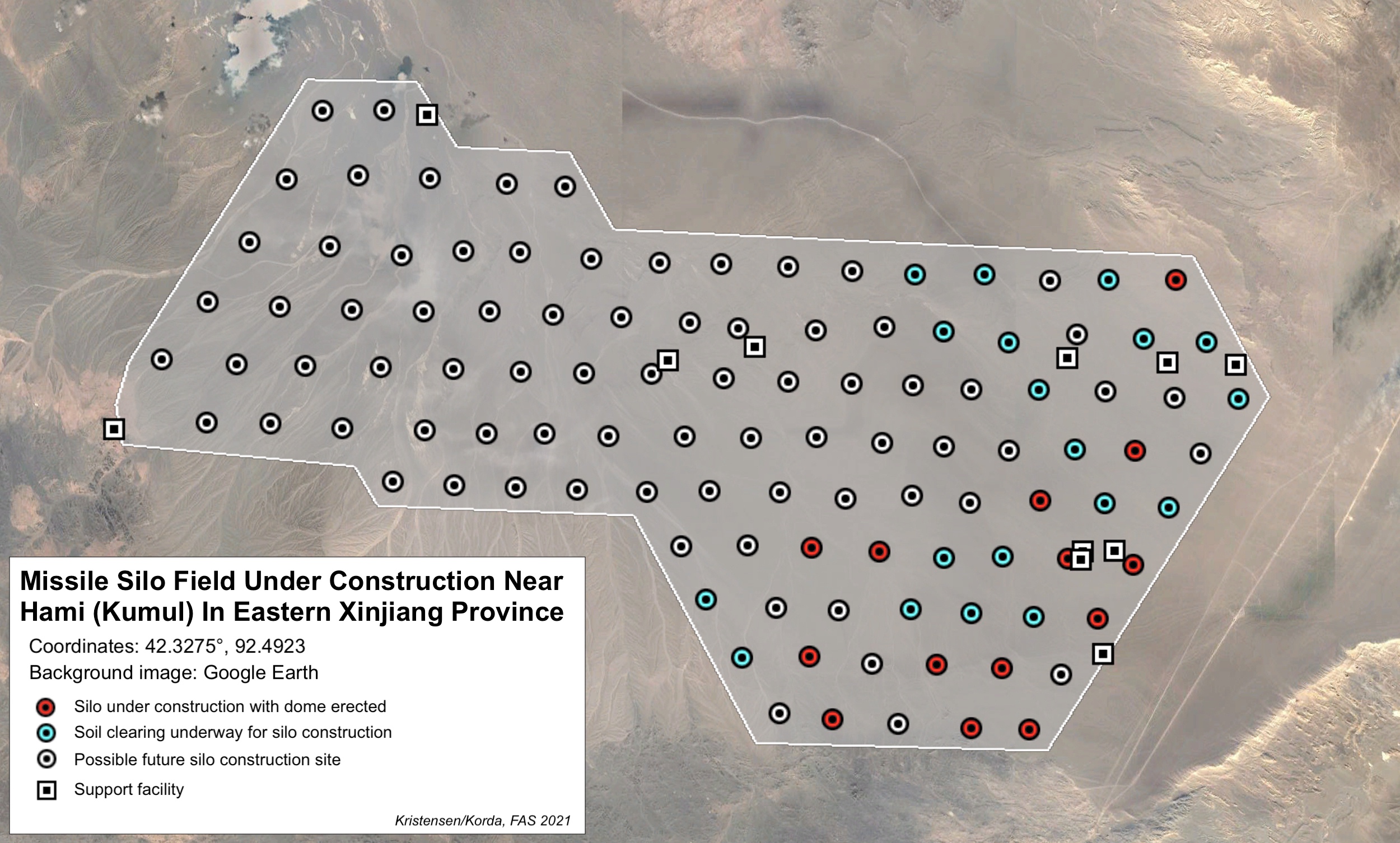

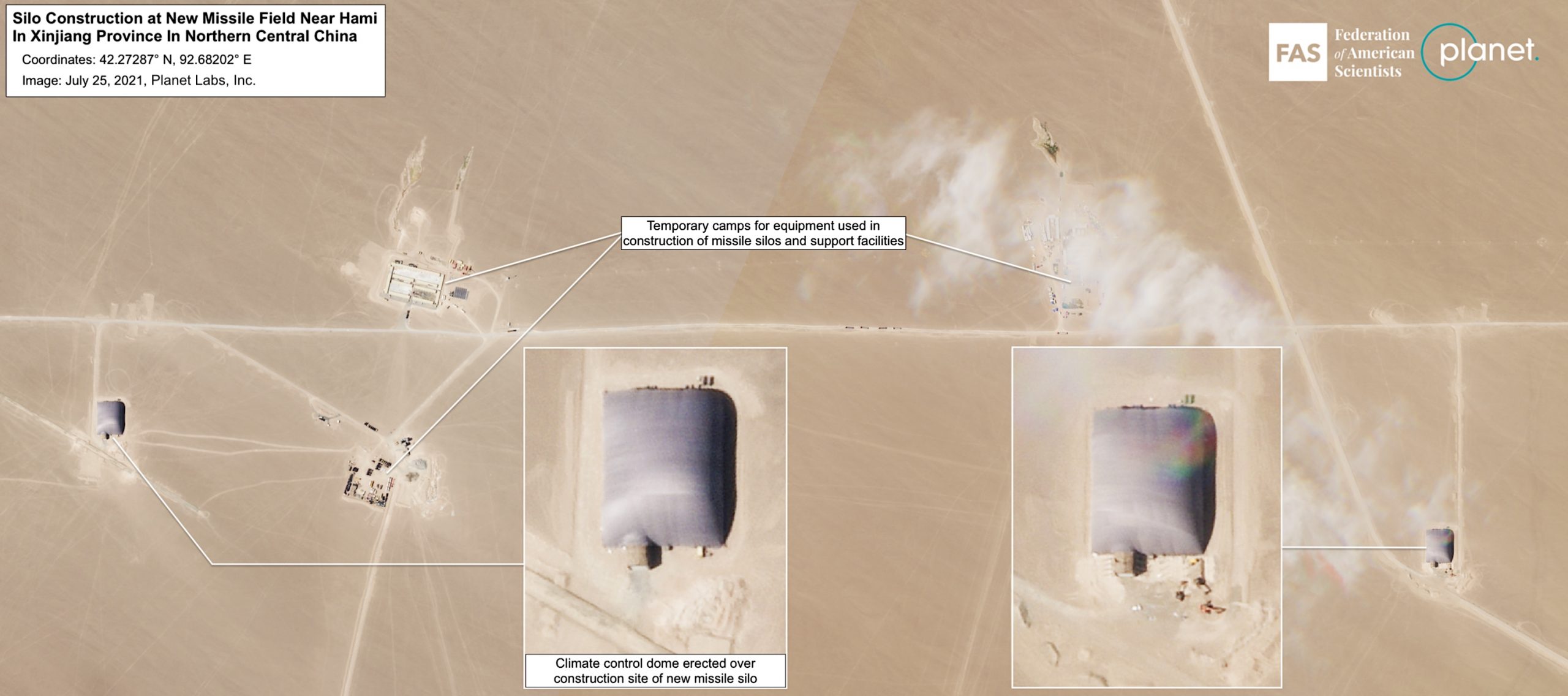

Satellite images reveal that China is building a second nuclear missile silo field. The discovery follows the report earlier this month that China appears to be constructing 120 missile silos near Yumen in Gansu province. The second missile silo field is located 380 kilometers (240 miles) northwest of the Yumen field near the prefecture-level city of Hami in Eastern Xinjiang.

The Hami missile silo field is in a much earlier stage of development than the Yumen site. Construction began at the start of March 2021 in the southeastern corner of the complex and continues at a rapid pace. Since then, dome shelters have been erected over at least 14 silos and soil cleared in preparation for construction of another 19 silos. The grid-like outline of the entire complex indicates that it may eventually include approximately 110 silos.

Dome structures have been erected over 14 silo construction sites. Preparation is underway for another 19, and the entire missile field might eventually include 110 silos.

The Hami site was first spotted by Matt Korda, Research Associate for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, using commercial satellite imagery. Higher resolution images of the site were subsequently provided by Planet.

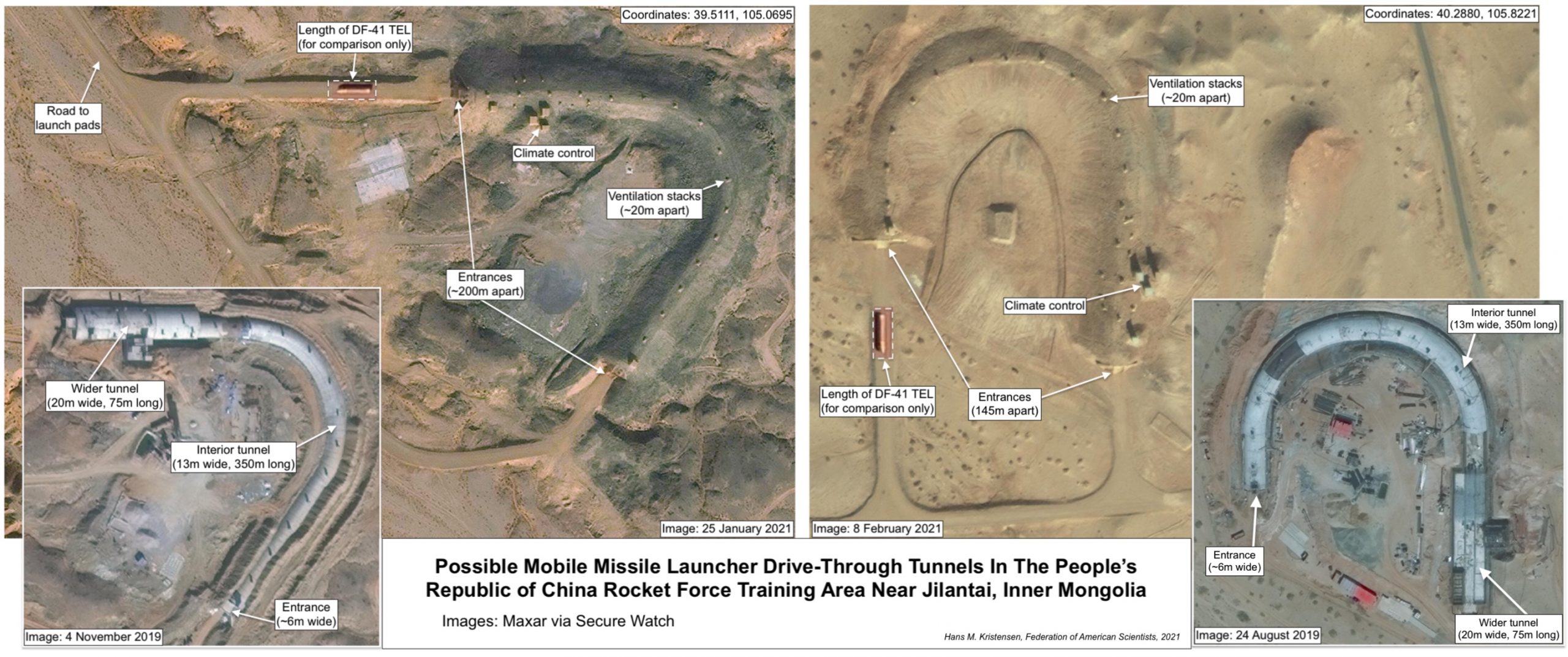

The silos at Hami are positioned in an almost perfect grid pattern, roughly three kilometers apart, with adjacent support facilities. Construction and organization of the Hami silos are very similar to the 120 silos at the Yumen site, and are also very similar to the approximately one-dozen silos constructed at the Jilantai training area in Inner Mongolia. These shelters are typically removed only after more sensitive construction underneath is completed. Just like the Yumen site, the Hami site spans an area of approximately 800 square kilometers.

The Hami missile silo field has a grid-pattern where the silos are located approximately 3 kilometers from each other.

Impact on the Chinese nuclear arsenal

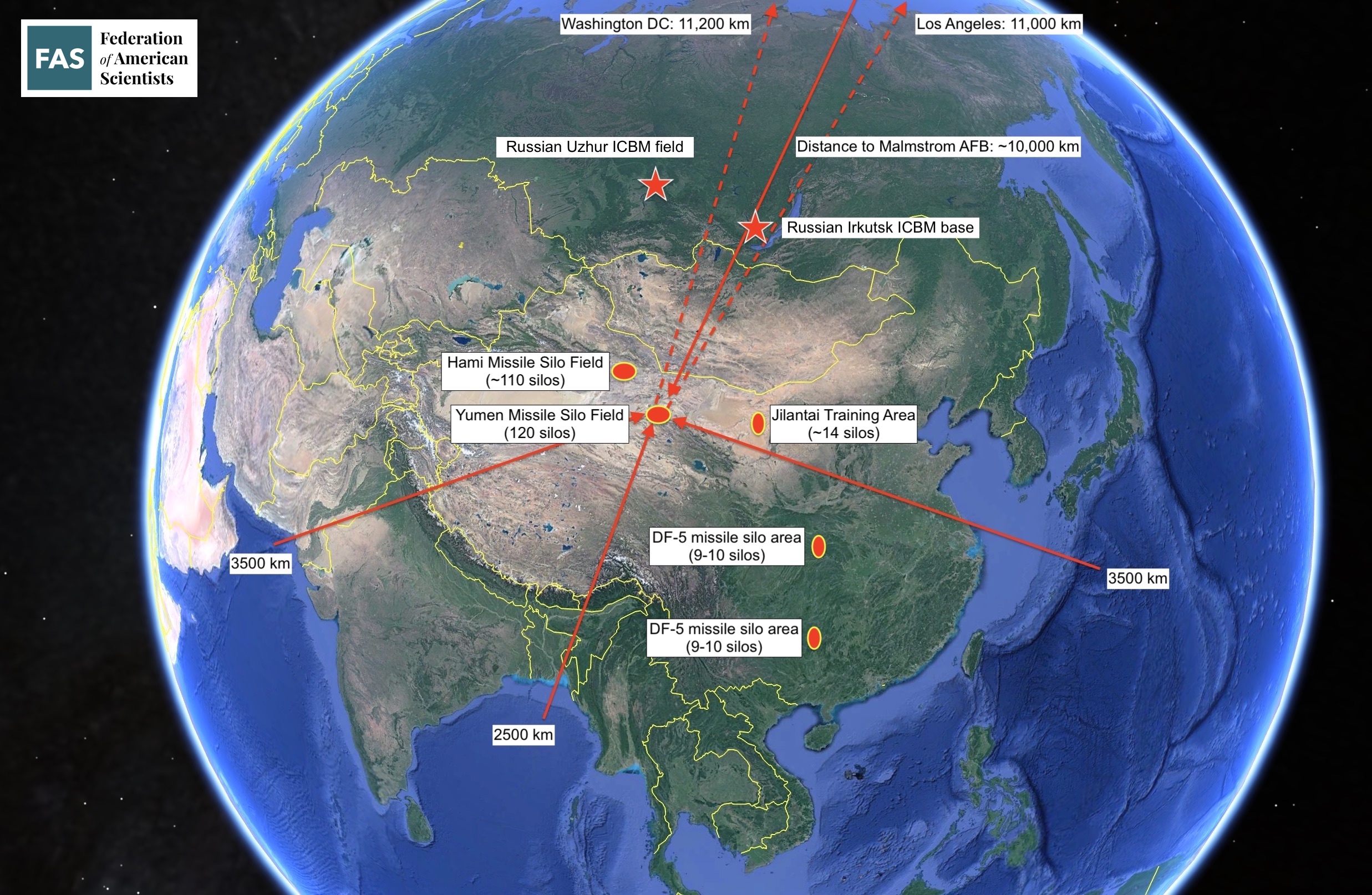

The silo construction at Yumen and Hami constitutes the most significant expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever. China has for decades operated about 20 silos for liquid-fuel DF-5 ICBMs. With 120 silos under construction at Yumen, another 110 silos at Hami, a dozen silos at Jilantai, and possibly more silos being added in existing DF-5 deployment areas, the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) appears to have approximately 250 silos under construction – more than ten times the number of ICBM silos in operation today.

The number of new Chinese silos under construction exceeds the number of silo-based ICBMs operated by Russia, and constitutes more than half of the size of the entire US ICBM force. The Chinese missile silo program constitutes the most extensive silo construction since the US and Soviet missile silo construction during the Cold War.

The 250 new silos under construction are in addition to the force of approximately 100 road-mobile ICBM launchers that PLARF deploys at more than a dozen bases. It is unclear how China will operate the new silos, whether it will load all of them with missiles or if a portion will be used as empty decoys. If they are all loaded with single-warhead missiles, then the number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs could potentially increase from about 185 warheads today to as many as 415 warheads. If the new silos are loaded with the new MIRVed DF-41 ICBMs, then Chinese ICBMs could potentially carry more than 875 warheads (assuming 3 warheads per missile) when the Yumen and Hami missile silo fields are completed.

It should be emphasized that it is unknown how China will operate the new silos and how many warheads each missile will carry. Regardless, the silo construction represents a significant increase of the Chinese arsenal, which the Federation of American Scientists currently estimates includes approximately 350 nuclear warheads. The Pentagon stated last year that China had “an operational nuclear warhead stockpile in low-200s,” and STRATCOM commander Adm. Charles Richard said early this year that “China’s nuclear weapons stockpile is expected to double (if not triple or quadruple) over the next decade.” The new silos could allow China to accomplish this goal, if it is indeed the goal.

Although significant, even such an expansion would still not give China near-parity with the nuclear stockpiles of Russia and the United States, each of whom operate nuclear warhead stockpiles close to 4,000 warheads.

The Hami missile silo field domes are identical to silo domes seen at the Yumen missile silo field and the Jilantai training area.

Chinese motivations

There are several possible reasons why China is building the new silos. Regardless of how many silos China ultimately intends to fill with ICBMs, this new missile complex represents a logical reaction to a dynamic arms competition in which multiple nuclear-armed players––including Russia, India, and the United States––are improving both their nuclear and conventional forces as well as missile defense capabilities. Although China formally remains committed to its posture of “minimum” nuclear deterrence, it is also responding to the competitive relationship with countries adversaries in order to keep its own force survivable and capable of holding adversarial targets at risk. Thus, while it is unlikely that China will renounce this policy anytime soon, the “minimum” threshold for deterrence will likely continue to shift as China expands its nuclear arsenal. The decision to build the large number of new silos has probably not been caused by a single issue but rather by a combination of factors, listed below in random order:

Ensuring survivability of nuclear retaliatory capability: China is concerned that its current ICBM silos are too vulnerable to US (or Russian) attack. By increasing the number of silos, more ICBMs could potentially survive a preemptive strike and be able to launch their missiles in retaliation. China’s development of its current road-mobile solid-fuel ICBM force was, according to the US Central Intelligence Agency, fueled by the US Navy’s deployment of Trident II D5 missiles in the Pacific. This action-reaction dynamic is most likely a factor in China’s current modernization.

Increasing the readiness of the ICBM force: Transitioning from liquid-fuel missiles to solid-fuel missiles in silos will increase the reaction-time of the ICBM force.

Protecting ICBMs against non-nuclear attack: All existing DF-5 silos are within range of US conventional cruise missiles. In contrast, the Yumen and Hami missile silo fields are located deeper inside China than any other Chinese ICBM base (see map below) and out of reach of US conventional missiles.

Overcoming potential effects of US missile defenses: Concerns that missile defenses might undermine China’s retaliatory capability have always been prominent. China has already decided to equip its DF-5B ICBM with multiple warheads (MIRV); each missile can carry up to five. The new DF-41 ICBM is also capable of MIRV and the future JL-3 SLBM will also be capable of carrying multiple warheads. By increasing the number of silos-based solid-fuel missiles and the number of warheads they carry, China would seek to ensure that they can continue to penetrate missile defense systems.

Transitioning to solid-fuel silo missiles: China’s old liquid-fuel DF-5 ICBMs take too long to fuel before they can launch, making them more vulnerable to attack. Handling liquid fuel is also cumbersome and dangerous. By transitioning to solid-fuel missile silos, survivability, operational procedures, and safety of the ICBM force would be improved.

Transitioning to a peacetime missile alert posture: China’s missiles are thought to be deployed without nuclear warheads installed under normal circumstances. US and Russian ICBMs are deployed fully ready and capable of launching on short notice. Because military competition with the United States is increasing, China can no longer be certain it would have time to arm the missiles that will need to be on alert to improve the credibility of China deterrent. The Pentagon in 2020 asserted that the silos at Jilantai “provide further evidence China is moving to a LOW posture.”

Balancing the ICBM force: Eighty percent of China’s roughly 110 ICBMs are mobile and increasing in numbers. The US military projects that number will reach 150 with about 200 warheads by 2025. Adding more than 200 silos would better balance the Chinese ICBM force between mobile and fixed launchers.

Increasing China’s nuclear strike capability: China’s “minimum deterrence” posture has historically kept nuclear launchers at a relatively low level. But the Chinese leadership might have decided that it needs more missiles with more warheads to hold more adversarial facilities at risk. Adding nearly 250 new silos appears to move China out of the “minimum deterrence” category.

National prestige: China is getting richer and more powerful. Big powers have more missiles, so China needs to have more missiles too, in order to underpin its status as a great power.

The Hami and Yumen missile silo fields are located deeper inside China than any other ICBM base and beyond the reach of conventional cruise missiles. Click on image to view full size. Image: Google Earth.

What to do about it?

China’s construction of nearly 250 new silos has serious implications for international relations and China’s role in the world. The Chinese government has for decades insisted it has a minimum deterrent and that it is not part of any nuclear arms race. Although it remains unclear how many silos will actually be filled with missiles, the massive silo construction and China’s other nuclear modernization programs are on a scale that appears to contradict these polices: the build-up is anything but “minimum” and appears to be part of a race for more nuclear arms to better compete with China’s adversaries. The silo construction will likely further deepen military tension, fuel fear of China’s intensions, embolden arguments that arms control and constraints are naïve, and that US and Russian nuclear arsenals cannot be reduced further but instead must be adjusted to take into account the Chinese nuclear build-up.

The disclosure of the second Chinese silo missile field comes only days before US and Russian negotiators meet to discuss strategic stability and potential arms control measures. Responding to the Chinese build-up with more nuclear weapons would be unlikely to produce positive results and could cause China build up even more. Moreover, even when the new silos become operational, the Chinese nuclear arsenal will still to be significantly smaller than those of Russia and the United States.

The clearest path to reining in China’s nuclear arsenal is through arms control, but this is challenging. The United States has been trying to engage China on nuclear issues since the late-1990s, but so far with minimal success. Rather than discuss specific limitations on weapon systems, these efforts have been limited to increasing transparency about force structure plans and strategy, and well as discussing nuclear doctrine and intentions.

The Trump administration correctly sought to broaden nuclear arms control to include China, but fumbled the effort by turning it into a public-relations pressure stunt and insisting that China should be part of a New START treaty extension. Beijing not surprisingly rejected the effort, and Chinese officials have plainly stated that “it is unrealistic to expect China to join [the United States and Russia] in a negotiation aimed at nuclear arms reduction,” particularly while China’s arsenal remains a fraction of the size.

Bringing China and other nuclear-armed states into a sustained arms control dialogue will require a good-faith effort that will require the United States to clearly articulate what it is willing to trade in return for limits on Chinese forces. In this regard, it is worth noting that the absence of limits on US missile defenses is of particular and longstanding concern to both China and Russia. When the Bush administration decided to withdraw from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 2002, officials from both countries explicitly stated that the treaty’s demise would be highly destabilizing, and implied that they would take steps to offset this perceived US advantage. Nearly 20 years later, the knock-on effects of this decision are clear. Putting US missile defenses on the negotiating table could help clear the path towards enacting a new arms control agreement that ultimately keeps both Chinese and Russian nuclear arsenals in check.

But the Chinese nuclear modernization is driven by more than just missile defenses. This includes the nuclear modernization programs of the United States, India, and Russia, the significant enhancements of the conventional forces of those countries and their allies, as well as China’s own ambitions about world power status.

Later this year (or early next year) the parties to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) will meet to review the progress of the treaty. Although the treaty does not explicitly prohibit a country from modernizing or even increasing its nuclear arsenal, reduction and eventually elimination of nuclear weapons are key pillars of the treaty’s goal as reaffirmed by numerous previous NPT conferences. It is difficult to see how adding nearly 250 nuclear missile silos is consistent with China’s obligation to “pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament…”

Background information:

- China Expanding Missile Training Area: More Silos, Tunnels, and Support Facilities

- Chinese nuclear forces, 2021 (SIPRI Yearbook)

- The Pentagon’s 2020 China Report

Our Hami missile silo discovery was first featured in the New York Times on 26 July 2021.

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Secrecy: In Defense of Reform

One of the stranger features of nuclear weapons secrecy is the government’s ability to reach out and classify nuclear weapons-related information that has been privately generated without government involvement. This happened most recently in 2001.

The roots of this constitutionally questionable policy are investigated in Restricted Data, a book by science historian Alex Wellerstein that sheds new light on the origins and development of nuclear secrecy.

One might suppose that nuclear secrecy is merely incidental to the larger history of nuclear weapons, but Wellerstein demonstrates that the subject is rich and dynamic and consequential enough to merit a history of its own.

He traces nuclear secrecy back to the Manhattan Project (or shortly before) when the most basic questions were first posed: what is a nuclear secret? what is the role of “information” in creating nuclear weapons? what can secrecy accomplish and what are its hazards? when and how are secrets to be disclosed?

Answers to such questions naturally varied. The basic idea of the atomic bomb did not actually involve any secrets, according to physicist Hans Bethe. But when it came to the hydrogen bomb, he said, “this time we have a real secret to protect.”

Wellerstein is not just an accomplished historian who has done his archival homework, he is also a lively storyteller. And he leavens his narrative with surprising observations and insights. We learn, for example, that Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn read a copy of the official Smyth Report on the atomic bomb while on his way to the Gulag. Elsewhere Wellerstein writes that declassification can be a way of reinforcing classification: “the release of some information [is] used to uphold the importance of not releasing other information. . . . disclosure could be a form of control as well.”

Challenges to nuclear secrecy quickly came from many directions: Soviet spies, recalcitrant scientists, careless bureaucrats, and eventually “anti-secrecy” activists.

Wellerstein devotes a particularly engaging chapter to the “anti-secrecy” efforts of Howard Morland, the late Chuck Hansen, and Bill Arkin who all, for their own diverse reasons, defied or circumvented secrecy controls.

He gives less focused attention to more conventional attempts to reform and reduce nuclear secrecy, which he seems to consider less significant than the antagonistic efforts to discover classified matters.

Maybe because I was present on the periphery of the Openness Initiative led by Secretary of Energy Hazel O’Leary in 1993-97, I found Wellerstein’s treatment of it to be somewhat cursory and understated. From my perspective, the O’Leary Openness Initiative represented the single biggest discontinuity in the history of nuclear secrecy since the 1945 Smyth Report that first described the production of the atomic bomb.

Within a fairly short period of time, O’Leary declassified and disclosed (as Wellerstein notes) a complete list of nuclear explosive tests and their yields; inventories of highly enriched uranium and weapons-grade plutonium; most of the previously classified research on inertial confinement fusion; and a wealth of other historical and contemporary nuclear weapons-related information that had been sought by researchers and advocates. The final report of a year-long Fundamental Classification Policy Review launched by O’Leary and intended to reboot classification policy somehow did not make it into Wellerstein’s notes or bibliography. A copy is here.

Outside critics of secrecy who join the government will often adapt themselves to the status quo, Wellerstein writes. They find that secrecy is “sticky” and hard to dislodge. Yet O’Leary dislodged it repeatedly.

The date of her 1993 Openness press conference — it was December 7 — remains fresh in memory because a Washington Times columnist called it “the most devastating single attack on the underpinnings of the U.S. national security structure since Japan’s lightning strike” on Pearl Harbor. That can’t have been pleasant for her. But O’Leary came back and did it again with more declassified disclosures a few months later. And then again.

So one lesson for secrecy reform that emerges from the O’Leary Openness Initiative is that it matters who is in charge. Given a choice between an opportunity to wordsmith a classification policy regulation or to select an agency head who is committed to open government, it is clear what the right move would be. Good policy statements can be ignored or subverted. Good leaders will often get the job of reform done.

A second lesson here is that “nuclear secrecy” is not an undifferentiated mass of information and that not all nuclear secrets are equally important or equally in demand.

O’Leary’s use of the management jargon of “stakeholders” reflected the reality that different groups had different interests in reducing nuclear secrecy and that different secrets were sought by each. Environmentalists wanted environmental information. Laser fusion scientists wanted fusion technology. Arms controllers wanted stockpile data. Historians wanted other things. And so on. Interestingly, there was also plenty of stuff that no one wanted. There is a good deal of classified technical data that has little or no policy relevance or historical significance — or that everyone agrees is properly withheld.

It can be difficult to think clearly about nuclear secrecy and to set aside what one wishes were true in order to acknowledge what actually appears to be the case. As startling and unprecedented as O’Leary’s disclosures were, the lasting impact of the Openness Initiative was limited, as Wellerstein assesses. Her disclosures were not reversed (they couldn’t be), but her successors resembled her predecessors more than they resembled her. What’s worse is that mere “facts” like those that she released seem to have less traction on the political process than ever before.

Wellerstein does an outstanding job of explaining how we got where we are today, and his analysis will help inform where we might realistically hope to go in the future. Restricted Data is bound to be the definitive work on the history of nuclear secrecy.

* * *

Last month marked 30 years since the classified Pentagon nuclear rocket program codenamed Timberwind was disclosed without authorization. See “Secret Nuclear-Powered Rocket Being Developed for ‘Star Wars'” by William J. Broad, New York Times, April 3, 1991.

In those days before the world wide web and the proliferation of online news and opinion, the story’s appearance on the front page of the New York Times (“above the fold”) commanded wide attention and soon led to formal declassification of the program followed by its termination.

* * *

There is no shortage of secrets remaining at the Department of Energy, according to one recent account. See “If You Want To Hide A Classified Program, Try The Department Of Energy” by Brett Tingley, The Drive: The Warzone, May 13.

First New START Data After Extension Shows Compliance

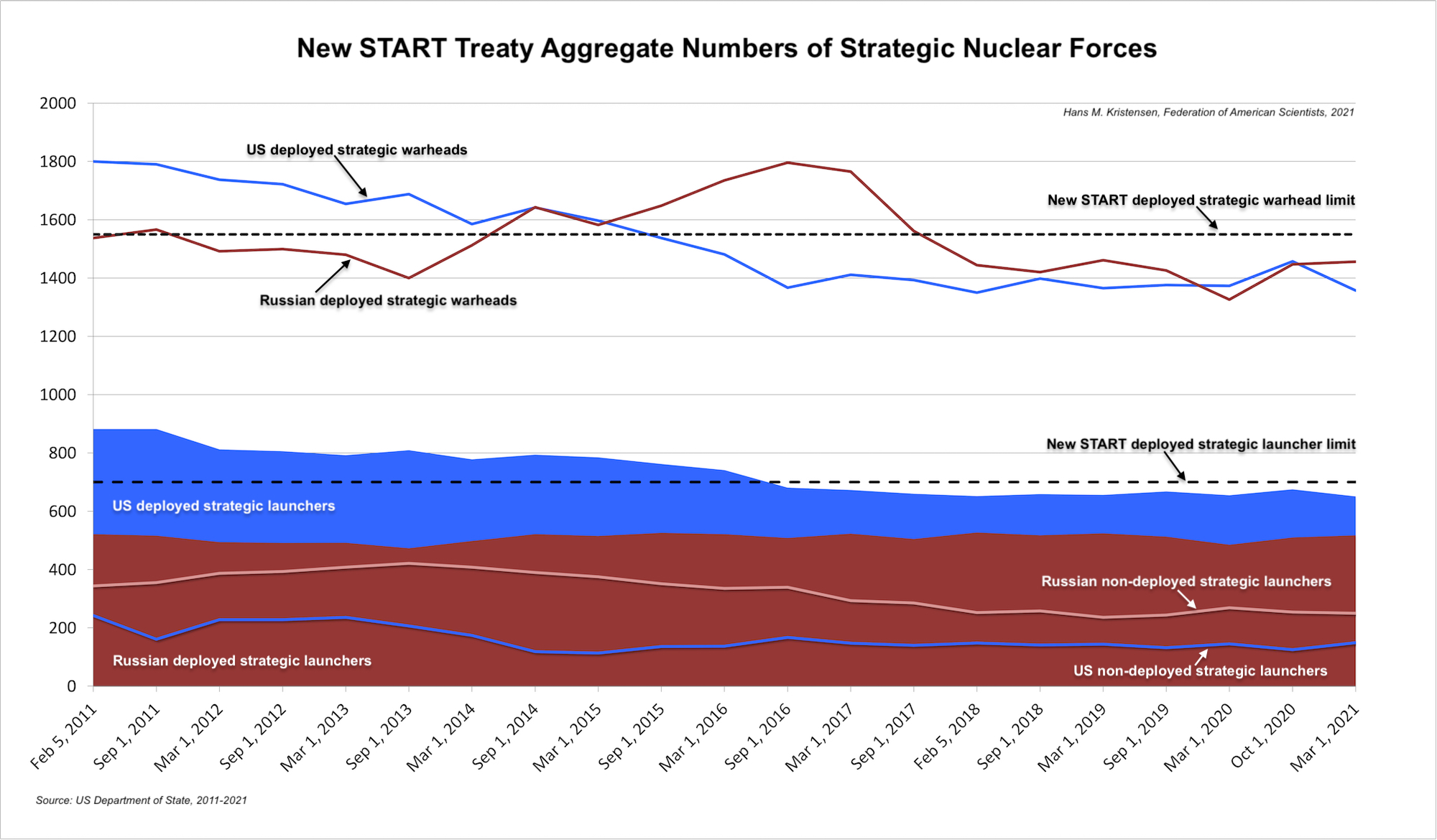

The first public release of New START aggregate numbers since the United States and Russia in February extended the agreement for five years shows the treaty continues to limit the two nuclear powers strategic offensive nuclear forces.

Continued adherence to the New START limits is one of the few positive signs in the otherwise frosty relations between the two countries.

The ten years of aggregate data published so far looks like this:

Combined Forces

The latest set of this data shows the situation as of March 1, 2021. As of that date, the two countries possessed a combined total of 1,567 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,168 launchers were deployed with 2,813 warheads. That is a slight decrease in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2020, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 3, decreased combined deployed strategic launchers by 17, and decreased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 91. Of these numbers, only the “3” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 combined have cut 422 strategic launchers from their arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 235, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 524. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (just over 6 percent) of the estimated 8,297 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (just over 4 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 11,807 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States currently possessing 800 strategic launchers, exactly the maxim number allowed by the treaty, of which 651 are deployed with 1,357 warheads attributed to them. This is a decrease of 24 deployed strategic launchers and 100 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. These are not actual decreases but reflect normal fluctuations caused by launchers moving in and out of maintenance. The United States has not reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers since 2017.

The aggregate data does not reveal how many warheads are attributed to the three legs of the triad. The full unclassified data set will be released later. But if one assumes the number of deployed bombers and deployed ICBMs are the same as in the September 2020 data, then the SSBNs carry 909 warheads on 200 deployed Trident II SLBMs. That is a decrease of 100 warheads on the SSBN force compared with September, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for 67 percent of all the 1,357 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 70 percent if excluding the “fake” 50 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data indicates that the United States as of March 1, 2021 deployed approximately 909 warheads on ballistic missile onboard its strategic submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 231, and deployed strategic warheads by 443. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 12 percent) of the 3,800 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (less than 8 percent if counting total inventory of 5,800 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 767 strategic launchers, of which 517 are deployed with 1,456 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is an increase of 7 deployed launchers and 9 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its inventory of strategic launchers by 98, deployed launchers by 4, and deployed strategic warheads by 81. This modest warhead reduction represents less than 2 percent of the estimated 4,497 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (only 1.3 percent if counting the total inventory of 6,257 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) Russian warheads).

Compared with 2011, the Russian reductions accomplished under New START are smaller than the U.S. reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Build-up, What Build-up?

With frequent claims by U.S. officials that Russia is increasing its nuclear arsenal, which may be happening in some categories, it is interesting that despite a significant modernization program, the New START data shows this increase is not happening in the size of Russia’s accountable strategic nuclear forces. (The number of strategic-range nuclear forces outside New START is minuscule.)

On the contrary, the New START data shows that Russia has 134 deployed strategic launchers less than the United States, a significant gap roughly equal to the number of missiles in an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. It is significant that Russia despite its modernization programs so far has not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by nearly one-third since its lowest point in February 2018.

Although Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces, such as those of this SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) ICBM exercise near Bernaul, this has not yet resulted in an increase of its strategic nuclear weapons.

Instead, the Russian military appears to try to compensate for the launcher disparity by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles (SS-27 Mod 2, Yars, and SS-N-32, Bulava) that are replacing older types (SS-25, Topol, and SS-N-18, Vysota). Thanks to the New START treaty limit, many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but are stored and could potentially be uploaded onto the launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (SS-19 Mod 4, Avangard, and SS-29, Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types (Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, and Burevestnik nuclear-powered ground-launched cruise missile) are not yet deployed and appear to be planned in relatively small numbers. They do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types, if the two sides agree.

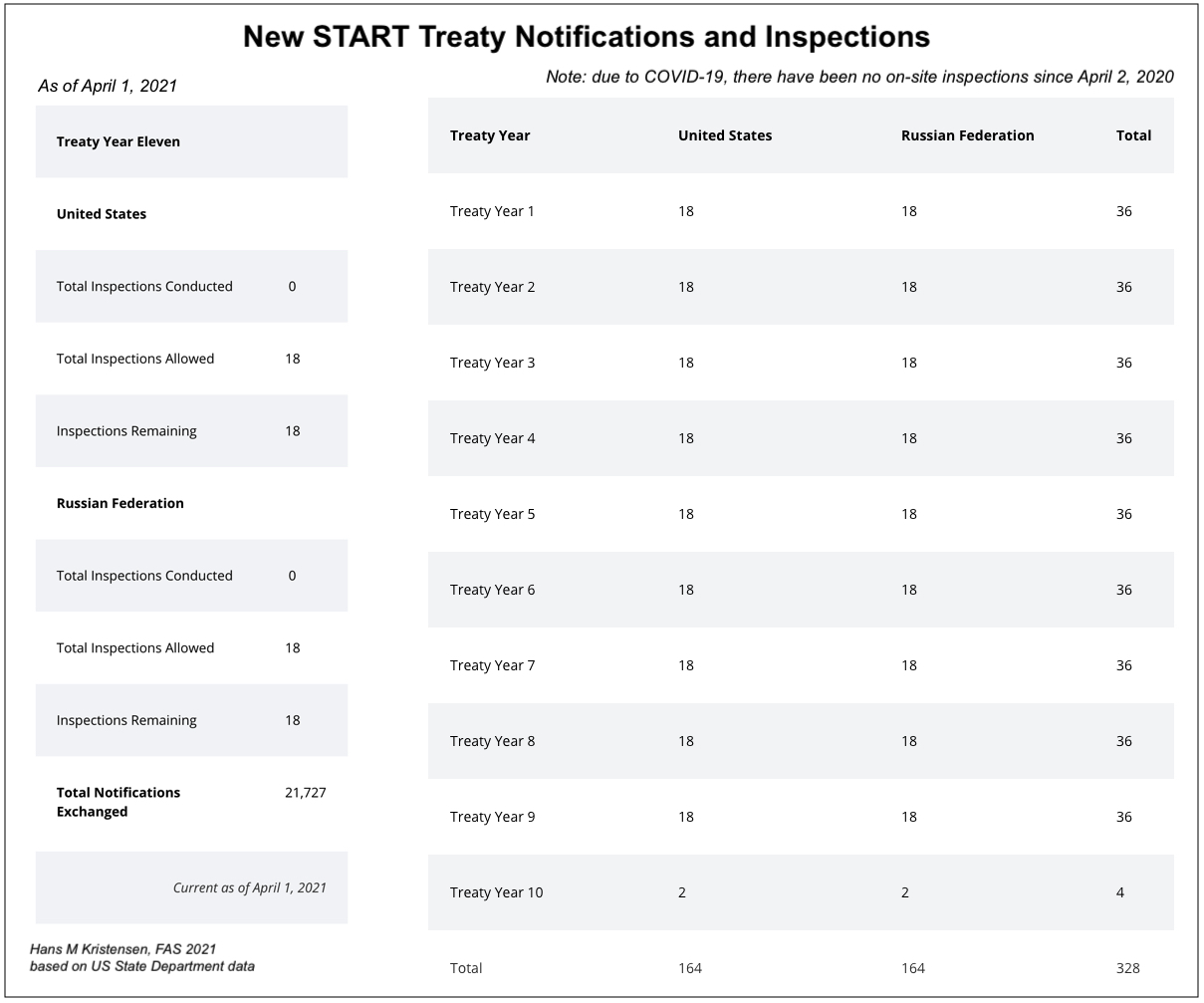

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the New START data, the U.S. State Department has also updated the overview of part of its treaty verification activities. The data shows that the two sides since February 2011 have carried out 328 on-site inspections of each other’s strategic nuclear forces and exchanged 21,727 notifications of launcher movements and activities. Nearly 860 of those notifications were exchanged since September 2020.

Importantly, due to the Coronavirus outbreak, there have been no on-site inspections conducted since April 1, 2020. Instead, notification exchanges and National Technical Means of verification have provided adequate verification. Nonetheless, on-site inspection can hopefully be resumed soon.

This inspection and notification regime and record are crucial parts of the treaty and increasingly important for U.S.-Russian strategic relations as other treaties and agreements have been scuttled.

Looking Ahead

Although the New START treaty has been extended for five years and it appears to be working, that is no reason to be complacent. The United States and Russia should undertake detailed and ongoing negotiations about what a follow-on treaty will look like, so they are ready well before the five-year extension runs out. The incompetent and brinkmanship negotiation style of the Trump administration fully demonstrated the risks and perils of waiting to the last minute. The Biden administration can and should do better.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The U.S. Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Force: A Post-Cold War Timeline

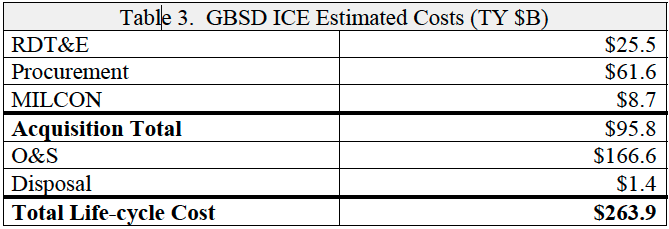

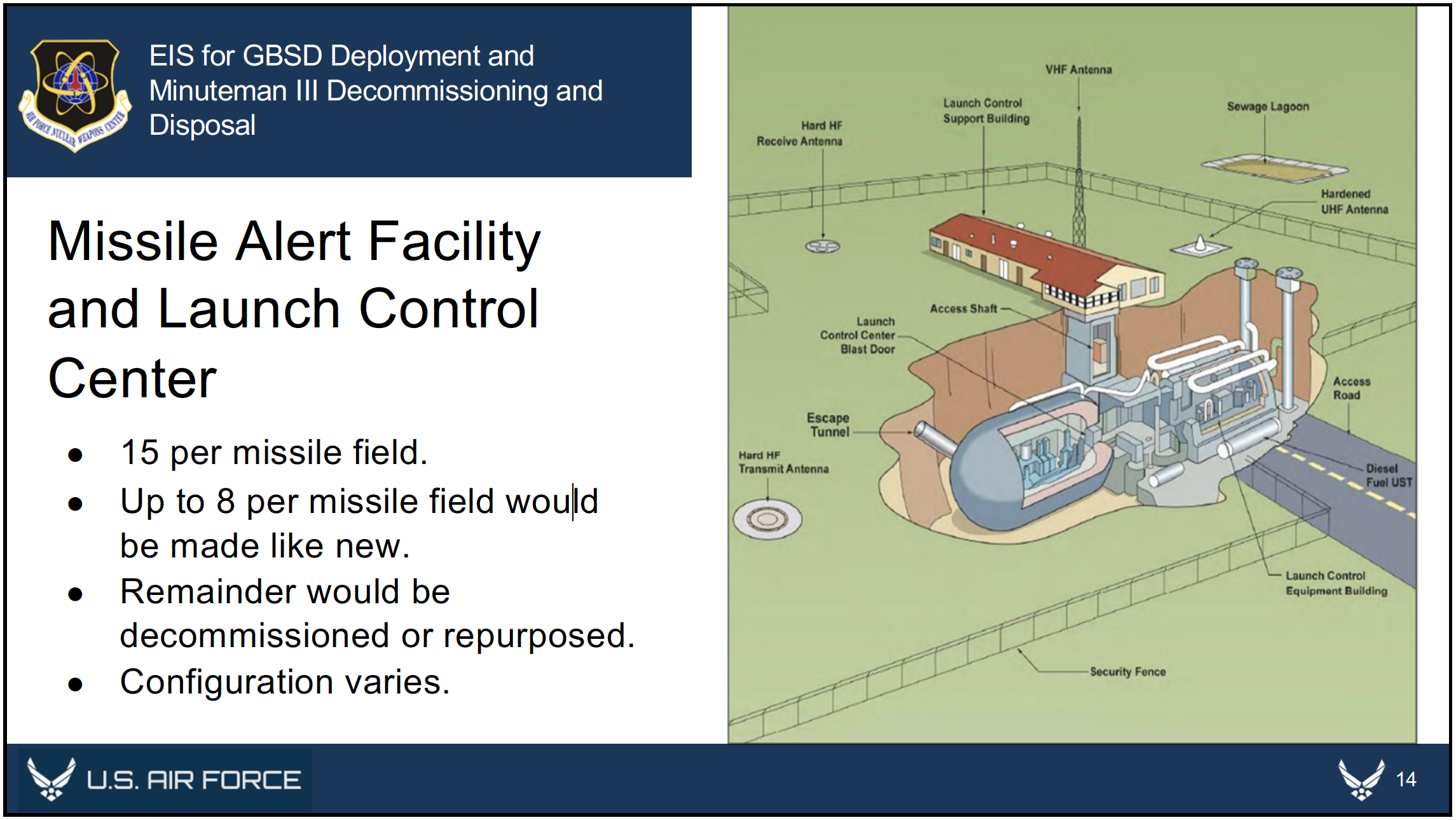

The Pentagon is currently planning to replace its current arsenal of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) with a brand-new missile force, known as the Sentinel (previously called the Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, or GBSD); it was previously estimated to cost approximately $100 billion in acquisition fees and $264 billion throughout its lifecycle until 2075 (in Then-Year dollars); however, the price tag has since risen substantially, calling the program’s future into question.

Below, you will find a comprehensive timeline of all relevant actions taken relating to the ICBM force since the end of the Cold War, including force posture alterations, international treaties, congressional efforts, government studies, and milestones in the Sentinel acquisition process.

The United States and Soviet Union sign the START Treaty.

START prohibited each country from deploying more than 6,000 nuclear warheads deployed on up to 1,600 strategic delivery vehicles. At the time, the United States’ ICBM force comprised 450 single-warhead Minuteman IIs, 500 three-warhead Minuteman IIIs, and 50 ten-warhead Peacekeeper MX missiles––for a total of 2,450 warheads attributed to 1,000 ICBMs.

27 September 1991

President Bush announces the de-alerting and eventual retirement of all 450 Minuteman II ICBMs.

With the Cold War coming to a close, President Bush took the first steps toward reducing the United States’ land-based nuclear force under the direction of the newly-signed START Treaty.

The first Minuteman II ICBM is removed from Ellsworth Air Force Base’s Golf-02 silo near Red Owl, South Dakota.

The last Minuteman II ICBM at Ellsworth Air Force Base was withdrawn from its silo in April 1994, and the 44th Missile Wing became formally inactive in July 1994.

The United States and Russia sign the START II Treaty.

In order to comply with START II’s ban on ICBMs with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs), the Pentagon planned to retire its 50 Peacekeeper MX ICBMs and de-MIRV its Minuteman III fleet, for an expected future ICBM force of 500 warheads attributed to 500 Minuteman III ICBMs; however, START II never entered into force. After the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT) was signed in 2002, President George Bush eventually did retire the Peacekeepers and download many of the MIRV’ed warheads from the Minuteman III force.

June 1993

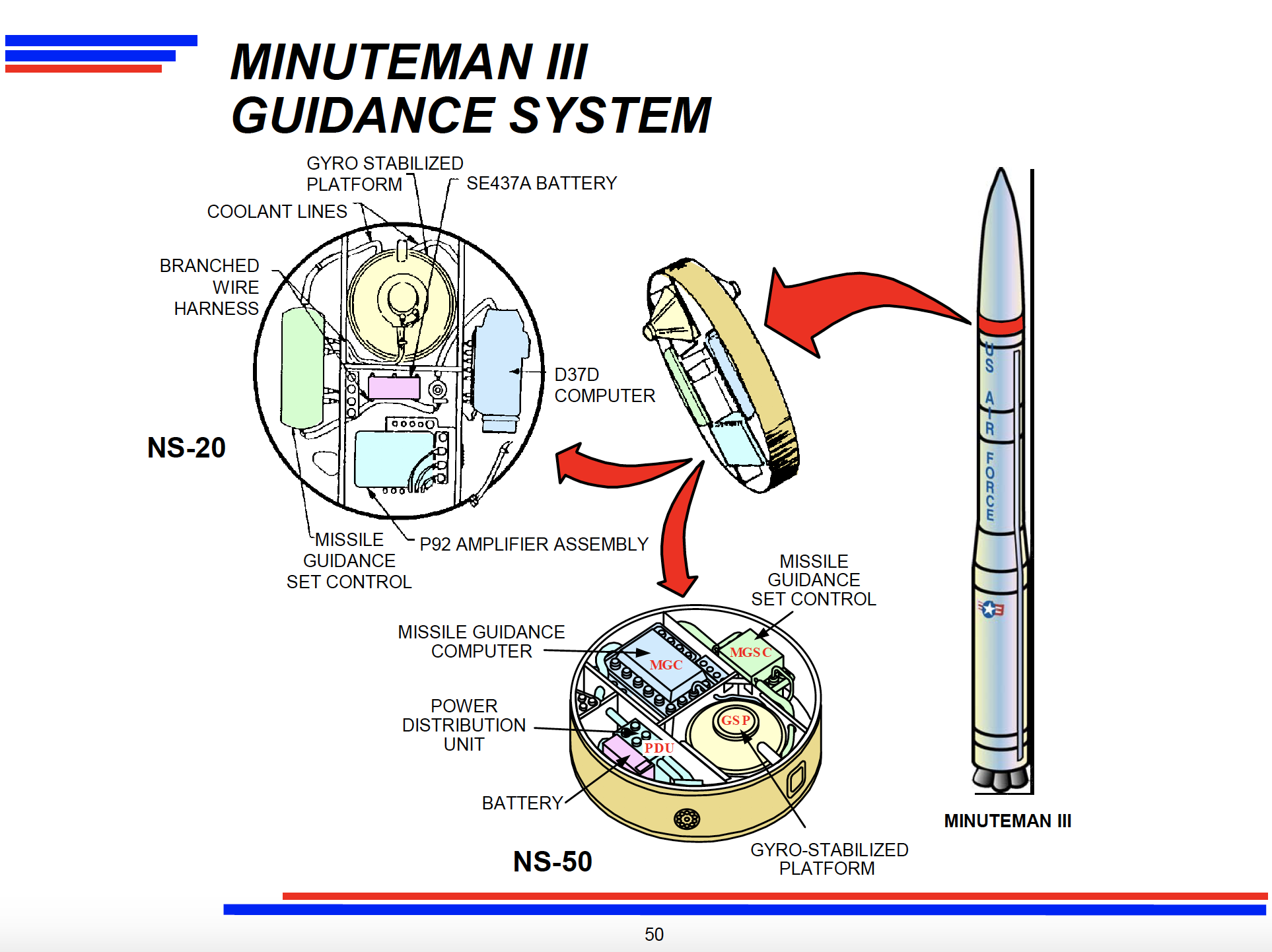

GAO publishes an evaluation of the proposed Minuteman III Guidance Replacement Program.

At the time, the Air Force hoped to begin replacing the Minuteman III’s guidance systems with upgraded versions. The GAO’s evaluation, titled” Minuteman III Guidance Replacement Program Had Not Been Adequately Justified,” noted that the Air Force’s own assessments “are not identifying any Minuteman III missile guidance set system-level performance concerns. To the contrary, for the last several years the Minuteman III missile guidance set flight reliability has improved.”

The study further assessed that “missile guidance set failure rates have remained at an acceptable level, with no adverse failure rate trends,” and quoted a previous Air Force study which suggested that “there is no conclusive evidence of degradation within the Minuteman III missile guidance set that cannot be corrected on a case-by-case basis.”

Ultimately, Congress chose to fully fund the $1.6 billion program, which was completed in December 2008.

10 June 1993

GAO publishes its evaluation of the US nuclear modernization program.

The GAO’s evaluation included several notable passages:

p. 5: “We found that the Soviet threat to the weapon systems of the land and sea legs had also been overstated. For the sea leg, this was reflected in unsubstantiated allegations about likely future breakthroughs in Soviet submarine detection technologies, along with underestimation of the performance and capabilities of our own nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines. The projected threat to the sea leg was, however, used frequently as a justification for costly modernizations in the other legs to ‘hedge’ against SSBN vulnerability. Our specific finding, based on operational test results, was that submerged SSBNs are even less detectable than is generally understood, and that there appear to be no current or long-term technologies that would change this. Moreover, even if such technologies did exist, test and operational data show that the survivability of the SSBN fleet would not be in question.”

pp. 6-7, 14: “Compared to ICBMs, no operationally meaningful difference in time to target was found,” further noting that “SSBNs are in essentially constant communication with national command authorities and, depending on the scenario, SLBMs from submarine platforms would be almost as prompt as ICBMs in hitting enemy targets.”

pp. 7-8: “In comparing performance and cost across the legs and weapon systems of the triad, we were concerned to find little or no prior recent effort by DOD to do what we were doing––that is, evaluate comprehensively the relative effectiveness of similar weapon systems. Yet such agency evaluation is critical if limited budget dollars are to be concentrated on programs that are both needed and effective. With regard to proposed upgrades, we found many instances of dubious support for claims of their high performance; insufficient and often unrealistic testing; understated cost; incomplete or unrepresentative reporting; lack of systematic comparison against the systems they were to replace; and unconvincing rationales for their development in the first place. Where mature programs were concerned, on the other hand, we often found that their performance was understated and that inappropriate claims of obsolescence had been made. […] Perhaps the most important point here is that comparative evaluation across the three legs of the triad–and between individual weapon systems and their proposed upgrades–has been signally lacking. This is unfortunate because it deprives policymakers in both the executive branch and the Congress of information they need for making decisions involving hundreds of billions of dollars.”

p. 14: Nuclear “[command, control, and communications] to SSBNs is about as prompt and as reliable as to ICBMs, under a range of conditions.”

1994

The Clinton administration releases its Nuclear Posture Review.

The first comprehensive review of the United States’ nuclear posture in the post-Cold War era was launched by the Department of Defense under Secretary Les Aspin. The Clinton administration’s Nuclear Posture Review working groups, convened by future Secretary of Defense Ash Carter, considered several proposals that would have eliminated the ICBM force entirely––including Carter’s suggestion to adopt a “monad” of 10 submarines carrying 24 Trident missiles with six warheads each––however, these proposals were quickly shot down. Ultimately, it was decided that ICBMs would remain part of the US nuclear deterrent.

5 December 1994

The START Treaty enters into force.

The START Treaty, signed three years earlier, was the first post-Cold War bilateral arms control treaty to reduce global nuclear arsenals and resulted in an 80 percent reduction of all strategic nuclear weapons in the world at the time of its implementation. The treaty expired in December 2009 and would later be replaced by New START, which was signed by the United States and Russia in 2010.

Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting (REACT) upgrade program completed.

The REACT system, originally conceived in the early 1980s, made it possible to retarget the entire Minuteman fleet in under ten hours, and––most critically––allowed missileers to continuously retarget individual missiles as necessary. Although the upgrade was painted at the time as primarily a means of reducing crew fatigue, it also further entrenched the idea of nuclear weapons as “flexible” tools that could be called upon in warfighting scenarios––a strain of thought that continues to dominate nuclear deterrence thinking to this day.

15 December 1997

The Minuteman II elimination process is completed.

The last Minuteman II silo––Hotel-11, near Dederick, Montana––was imploded on 15 December 1997, formally completing the Minuteman II elimination process.

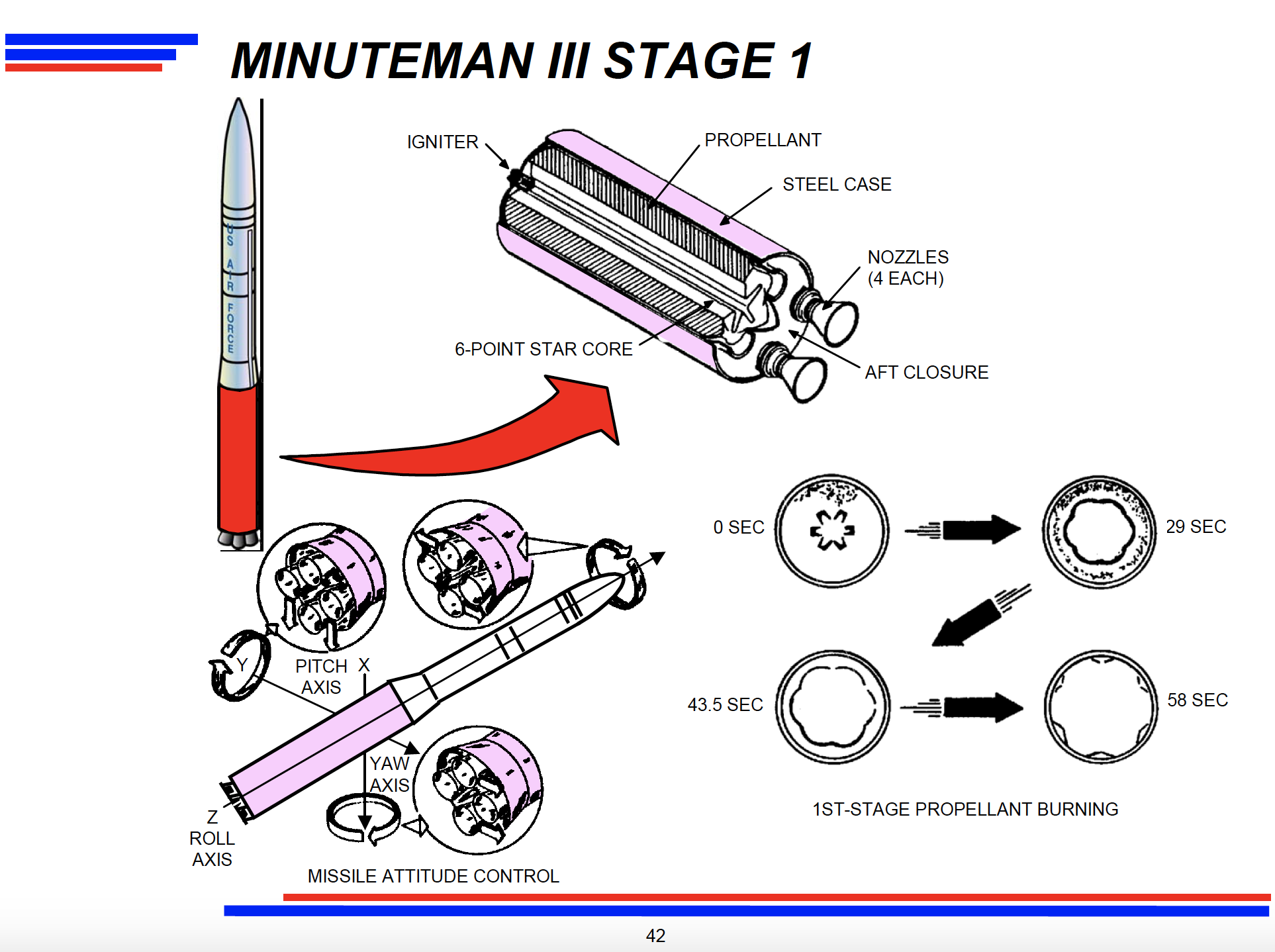

Propulsion Replacement Program (PRP) begins.

The PRP was a life-extension program for the Minuteman III that extended the service lives of approximately 600 solid rocket motors by re-manufacturing all three stages. The first PRP-extended missile was deployed at Malmstrom in April 2001.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 395.

Guidance Replacement Program (GRP) begins.

The GRP was a life-extension program for the Minuteman III that replaced both the electronic components of the missile guidance set control and the inertial measurement instruments contained within the gyro-stabilized platform.* The first GRP missile was installed on 3 August 1999 in launch facility I-09 at Malmstrom Air Force Base.**

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 174.

**David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 397.

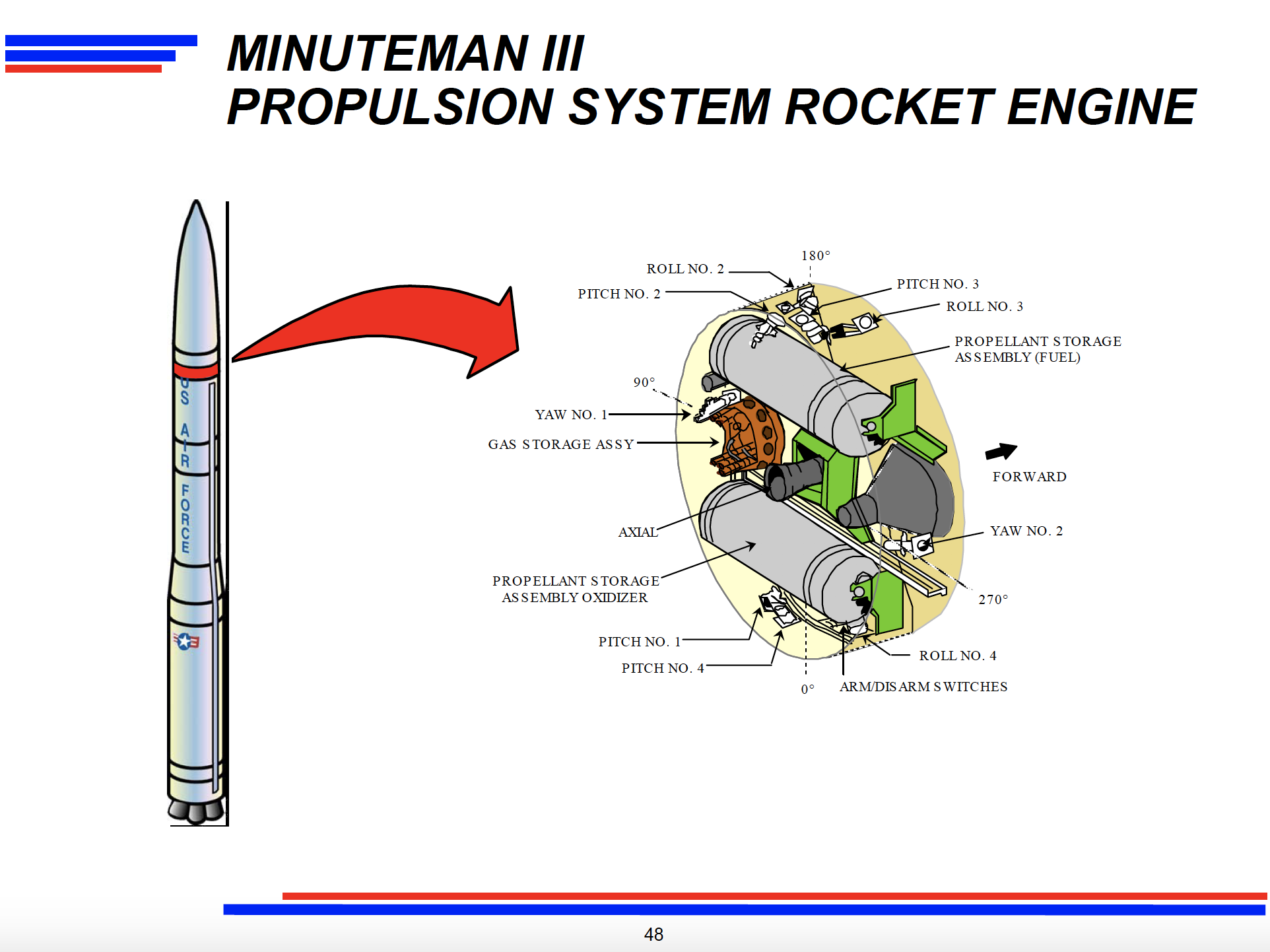

Propulsion System Rocket Engine (PSRE) life-extension program begins.

The PSRE life-extension program was initiated in February 2000 to sustain the Minuteman III missiles’ post-boost propulsion system. The program included the manufacture of 586 PSRE modification kits and cost approximately $107 million to complete.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 395.

8 January 2002

Bush administration publishes its Nuclear Posture Review.

This review established a “New Triad” composed of nuclear and non-nuclear offensive strike systems, active and passive defenses, and a responsive defense infrastructure. The report also called for a reduction in the US nuclear arsenal.

The United States and Russia sign the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT).

Both parties agreed to reduce their nuclear arsenals to between 1,700 and 2,200 operationally deployed warheads each. SORT entered into force on June 1, 2003, and was eventually superseded by the New START Treaty.

October 2002

The Air Force begins to decommission all 50 Peacekeeper ICBMs.

After almost twenty years of service, the LGM-118 Peacekeeper (MX) was phased out as part of the START II agreement (later bypassed by the SORT Treaty) with Russia.

September 2005

The Air Force deactivates the last remaining Peacekeeper ICBM.

As part of the Peacekeeper deactivation, the rockets were converted and repurpose for exploratory space missions (satellite launchers) and the W87 warheads were deployed on the Minuteman III missiles.

6 February 2006

Quadrennial Defense Review announces the reduction of the deployed Minuteman III force from 500 to 450.

The Department of Defense released the QDR in the fifth year of the War in Afghanistan. This review promoted the “New Triad” strategy proposed by the 2002 Nuclear Posture review and emphasized more tailorable approaches to deterrence. The QDR also announced the elimination of 50 additional ICBMs from service, for a remaining force of 450 ICBMs.

Rapid Execution and Combat Targeting (REACT) Service Life-Extension Program (SLEP) completed.

This upgrade modified the Minuteman launch control centers to combine the communications system and weapons system into one console, thereby reducing the number of keys for a launch and the time needed to retarget the ICBM force. The effort was identified as “essential to the future nuclear force,” according to the 2002 Nuclear Posture Review.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 178.

October 2006

As part of the SERV program, the Minuteman III three-warhead MIRVs were converted to the single Mk21 reentry vehicles that were previously carried by the Peacekeeper missile. The first SERV Minuteman III was deployed with the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base and placed on alert on 1 January 2007.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 396.

17 October 2006

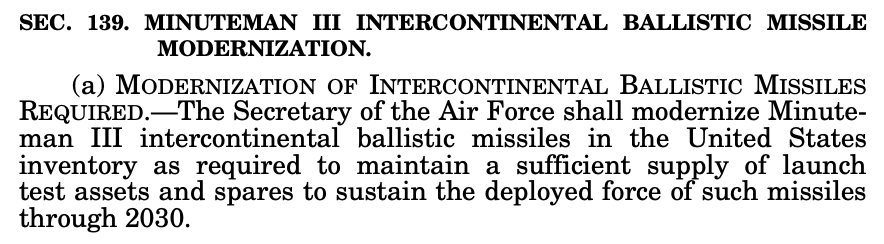

Congress passes the FY 2007 Defense Appropriations Act.

Sec. 139 directs the Secretary of the Air Force to “modernize Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missiles in the United States inventory as required to maintain a sufficient supply of launch test assets and spares to sustain the deployed force of such missiles through 2030.” This amendment proved to be incredibly 18 consequential because, as Air Force historian David N. Spires describes, “Although Air Force leaders had asserted that incremental upgrades, as prescribed in the analysis of land-based strategic deterrent alternatives, could extend the Minuteman’s life span to 2040, the congressionally mandated target year of 2030 became the new standard.”*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), pp. 184-185.

12 July 2007

The Air Force begins to deactivate the 50 Minuteman III ICBMs scheduled for retirement.

The 564th Missile Squadron, colloquially known as the “Odd Squad,” used different communications and launch control systems from the rest of the Minuteman III force, and was therefore a clear candidate for decommissioning. The entire decommissioning process was completed in approximately one year, with the final Minuteman III removed from its silo on 28 July 2008.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), p. 185-186.

December 2008

Guidance Replacement Program (GRP) completed.

The final GRP missile was installed on 18 February 2008 with the 90th Missile Wing at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, and Boeing delivered the final upgraded missile guidance set to the Air Force in December 2008.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 397.

7 August 2009

Creation of the Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC).

With major command headquarters at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana, AFGSC is responsible for the three ICBM wings and the entire bomber force. Air Force Global Strike Command is the service component to the United States Strategic Command, and its major command mission was formerly under the direction of Strategic Air Command, which was disestablished in 1992.

November 2009

ICBM Coalition publishes first white paper.

In anticipation of the crucial Senate vote on New START ratification, the white paper implied that the Coalition would deliver the crucial votes to support the treaty if the Obama administration committed to maintaining 450 ICBMs equipped with one warhead each.

March 2010

US Strategic Command sends an ICBM memo to Air Force Global Strike Command calling for an immediate start to a follow-on ICBM.

The memo indicates that the Air Force would have to begin a procurement effort for a follow-on ICBM immediately, if the Air Force planned to deploy it in the 2030 timeframe.*

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Intelligence and Capabilities Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XR), “Request for Information 12122011” (December 2011), US General Services Administration.

6 April 2010

Obama administration releases its Nuclear Posture Review.

The NPR announced the “deMIRV-ing” of the ICBM force, and called for the Pentagon to begin the Analysis of Alternatives process for a follow-on ICBM in fiscal years 2011 and 2012.

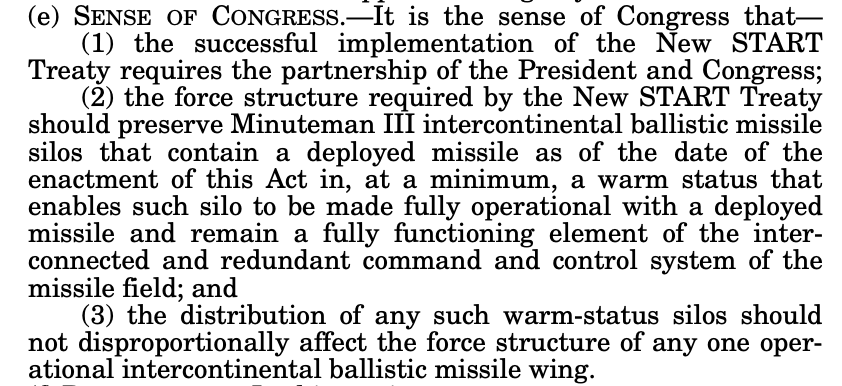

The United States and Russia sign the New START Treaty.

Replacing the START I Treaty, New START placed updated limitations on strategic nuclear arms, including a limit of 1,550 nuclear warheads deployed on no more than 700 strategic delivery vehicles. The treaty was set to have a duration of ten years and was extended in January 2021 for an additional five years.

On the same day as the ratification vote, the Obama administration delivered its intended force posture to Congress: the United States would eliminate 30 ICBMs, ultimately retaining a force level of 420 ICBMs with one warhead each. Of the 71 Senators who voted in favor of New START, six of them were members of the Senate ICBM Coalition.

5 February 2011

New START enters into force.

From the date the treaty entered into force, the United States and Russia had seven years to meet the treaty’s central limits on arms reduction. Both parties were in compliance with the central limits in February 2018.

May 2011

Air Force Global Strike Command completes its Capabilities-Based Assessment for the proposed GBSD program.

A Capabilities-Based Assessment (CBA) is one of the earliest elements of the defense acquisition process. It is used to identify the capabilities required to conduct a particular mission, determine whether there are potential capability gaps in the current system and evaluate their associated risks, and provide abstract recommendations for addressing those gaps. This analysis feeds into the subsequent Initial Capabilities Document, which the Air Force completed for the GBSD in May 2012.

December 2011

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center issues a Request For Information for the proposed GBSD program.

This RFI – which was based on the conclusions reached in the CBA and still-in-progress Initial Capabilities Document, was intended to solicit “concepts that address modernization or replacement of the ground based leg of the nuclear triad.”* It was one of the first public documents offering significant insight into how the Air Force was imagining the GBSD system at the time. Notably, the Air Force suggested that contractors could “propose innovative deployment and basing strategies, including, but not limited to mobile basing, fixed basing with mobile elements, or hardened silos, in addition to or in place of existing Minuteman III infrastructure.”

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Intelligence and Capabilities Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XR), “Request for Information RFI-12122011” (December 2011), US General Services Administration.

2012

Safety Enhanced Reentry Vehicle (SERV) conversion for Minuteman III completed.

Although the SERV program was billed as a safety measure due to the new emphasis on configuring the missile fleet with insensitive high explosives, enhanced detonation systems, and other safety features, it also had the practical effect of dramatically improving the Minuteman III’s hard-target kill capability.*

*David Spires, On Alert: An Operational History of the United States Air Force Intercontinental Ballistic Missile Program, 1945-2011 (Colorado Springs: United States Air Force, 2012), pp. 176-178.

May 2012

Joint DOD/DNI Report on Russian strategic forces.

In 2012, the Secretary of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence jointly concluded in a report to Congress that “the only Russian shift in its nuclear forces that could undermine the basic framework of mutual deterrence […] is a scenario that enables Russia to deny the United States the assured ability to respond against a substantial number of highly valued Russian targets following a Russian attempt at a disarming first strike––a scenario that the Department of Defense judges will most likely not occur.”

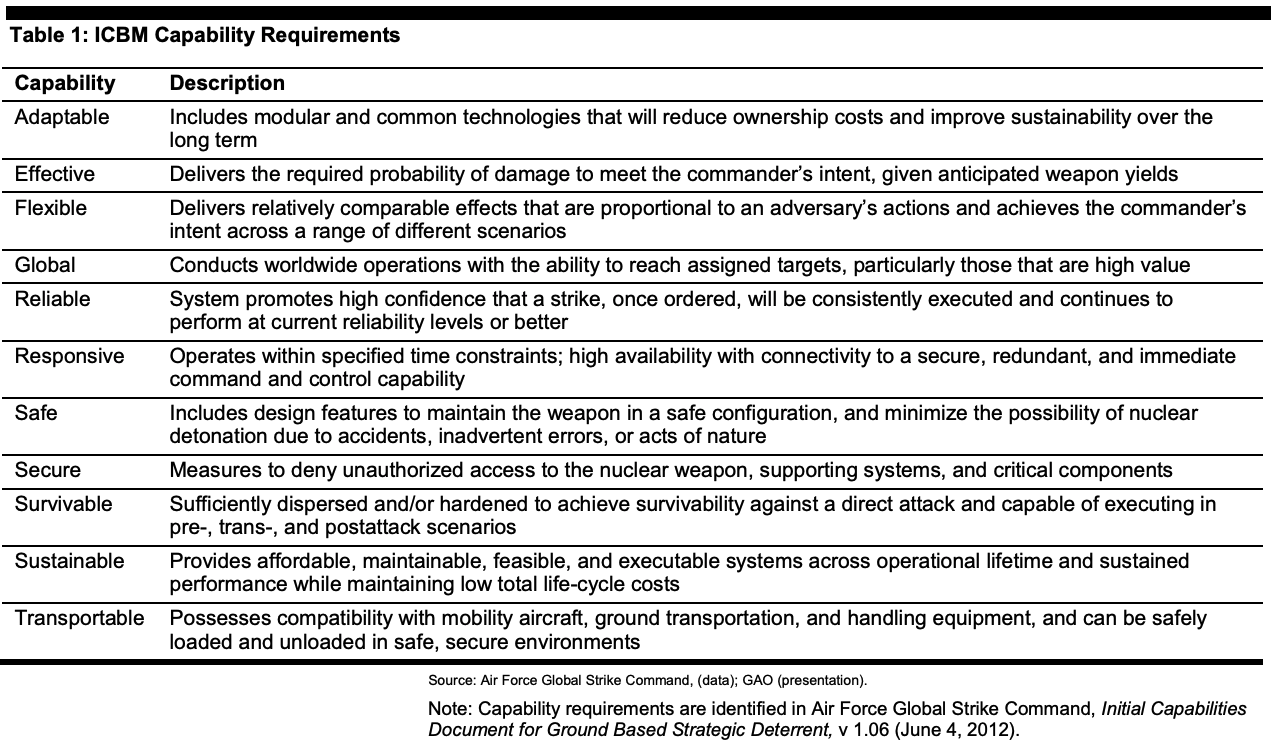

4 June 2012

An Initial Capabilities Document (ICD) further refines the analysis of the Capabilities-Based Assessment, justifies the need for a material change to the system, and provides a list of capabilities that the proposed new system would need to fulfill. This analysis is required for the acquisition process to proceed. The ICD suggested the following capability requirements for the GBSD: adaptable, effective, flexible, global, reliable, responsive, safe, secure, survivable, sustainable, transportable.

July 2012

Revised US nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) comes into effect.

As Hans Kristensen suggested at the time, “although very different from the [Cold War-era Single Integrated Operational Plan], OPLAN 8010-12 is still thought to be focused on nuclear warfighting scenarios using a Cold War-like Triad of nuclear forces on high alert to hold at risk and, if necessary, hunt down and destroy nuclear (and to a smaller extent chemical and biological) forces, command and control facilities, military and national leadership, and war supporting infrastructure in a myriad of tailored strike scenarios.”

8 August 2012

The Joint Requirements Oversight Council approves the Air Force’s Initial Capabilities Document and directs it to begin the Analysis of Alternatives process.

The Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) process is a critical component of the defense acquisition process. It compares the effectiveness, suitability, and life-cycle costs of each proposed material solution, and is therefore a key document that influences the system’s ultimate development and acquisition.*

*United States Air Force, “Cost Comparison of Extending the Life of the Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile to Replacing it with a Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent: Report to Congress,” Department of Defense (July 2016), p. 4.

2013

President Obama directs the Pentagon to reduce the number of circumstances under which the United States would rely on launch-under-attack.

Jon Wolfsthal, former senior director at the National Security Council for arms control and nonproliferation, subsequently described the implications of this decision as follows: “By openly stating that the United States could, and would, sacrifice its ICBMs in a conflict and still fulfill its missions, the country signaled the reliability and strength of its retaliatory forces.”

2013

Propulsion System Rocket Engine (PSRE) life-extension program completed.

This marked the conclusion of the $107 million contract that the Air Force had awarded to TRW in 2000 for refurbishing the Minuteman III’s liquid-propellant, upper-stage engine that operated during the post-boost phase of flight.*

*David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile That Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2020), p. 177.

January 2013

The Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center issues a Broad Agency Announcement for the GBSD program.

The Broad Agency Announcement (BAA) is intended to solicit white papers from industry with the purpose of further developing the GBSD design, specifically with an eye towards exploring new basing concepts. In the BAA, the Air Force listed five basing options for further consideration and refinement: “continued use”, “current fixed”, “new fixed”, “new mobile”, and “new tunnel.”*

*Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center, Program Development and Integration Directorate (AFNWC/XZ), “Broad Agency Announcement BAA-AFNWC-XZ-13-001Rev2” (14 January 2013), US General Services Administration.

30 January 2013

Senate ICBM Coalition writes to incoming Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel, critiquing his participation in Global Zero’s 2012 Nuclear Policy Commission Report, which specifically recommended eliminating US ICBMs.

The eight senators wrote to Hagel requesting a clarification regarding his position on ICBMs in a Global Zero report which Hagel had recently co-authored. The letter inquired as to whether Hagel supported eliminating ICBMs and whether he would support the continuation of the Analysis of Alternatives process for the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent.

June 2013

The Obama administration completes its review of US nuclear force posture under New START.

Although the administration ultimately concluded that the United States could reduce its deployed strategic forces by up to “one-third”––down to approximately 1,000-1,100 warheads––press reports indicated that the Pentagon contemplated reducing the arsenal to as low as 500 warheads in a plan known as the “deterrence only” approach.

23 July 2013

Allies of the Senate ICBM Coalition in the House of Representatives help quash an amendment to the FY 2014 National Defense Authorization Act that would reduce the number of ICBMs from 450 to 300.

As Illinois Democrat Rep. Mike Quigley’s amendment was defeated by voice vote, he took to the House floor to lambast his colleagues: “I’ve been here for four years, and I now recognize what the Department of Defense is. It is our jobs program. I respect my colleagues defending jobs in their district. But this isn’t about national security, it’s about job maintenance. That’s not what this is supposed to be about. If we’re going to spend money creating jobs, I want to build bridges, schools, and transit systems.”

25 September 2013

The Senate ICBM Coalition writes to Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel in “strenuous opposition” to the Pentagon’s plan to conduct an environmental assessment on the elimination of ICBM silos.

The environmental assessment would have been prepared as part of the New START implementation process; however, the Coalition called such a move “premature,” suggesting that “Treaty terms do not require the destruction of a single one of the 450 silos housing our Minuteman III force” and that considering such an action “would represent a serious breach of faith.”

18 December 2013