The Biden Administration’s Nuclear Posture Review

On 27 October 2022, the Biden administration finally released an unclassified version of its long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The classified NPR was released to Congress in March 2022, but its publication was substantially delayed––likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is the Pentagon’s primary statement of nuclear policy, produced by the last four presidents during their first years in office.

The NPR outlines the perceived global security environment, offers an overview of US nuclear capabilities, and considers plans for tailored deterrence, assurance, and arms control with allies and adversaries. The NPR can also be used to make changes to US declaratory nuclear policy, to consider alterations to the US nuclear stockpile, or to announce the introduction or retirement of specific weapon systems.

For more analysis, see: The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review: Arms Control Subdued by Military Rivalry

All of the nuclear-armed states––including the United States––plan to retain significant nuclear arsenals for the indefinite future.

All nine countries are modernizing their nuclear forces, several are adding new types, and many are increasing the role that nuclear weapons serve in military strategy and public statements.

For an overview of global modernization programs, see our annual contribution to the SIPRI Yearbook and our Status of World Nuclear Forces webpage. Individual country profiles are available in various editions the FAS Nuclear Notebook, which is published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and is freely available to the public.

A brief analysis of the 2022 NPR is available below; a more robust and detailed analysis is available on the FAS Strategic Security Blog.

Major Components of the NPR

Assumptions About U.S. Competitors

The NPR suggests that “[b]y the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” This echoes previous statements from high-ranking US military leaders, including the former and incoming Commanders of US Strategic Command.

China

Given that the National Defense Strategy is largely focused on China, it is unsurprising that the NPR declares China to be “the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent.”

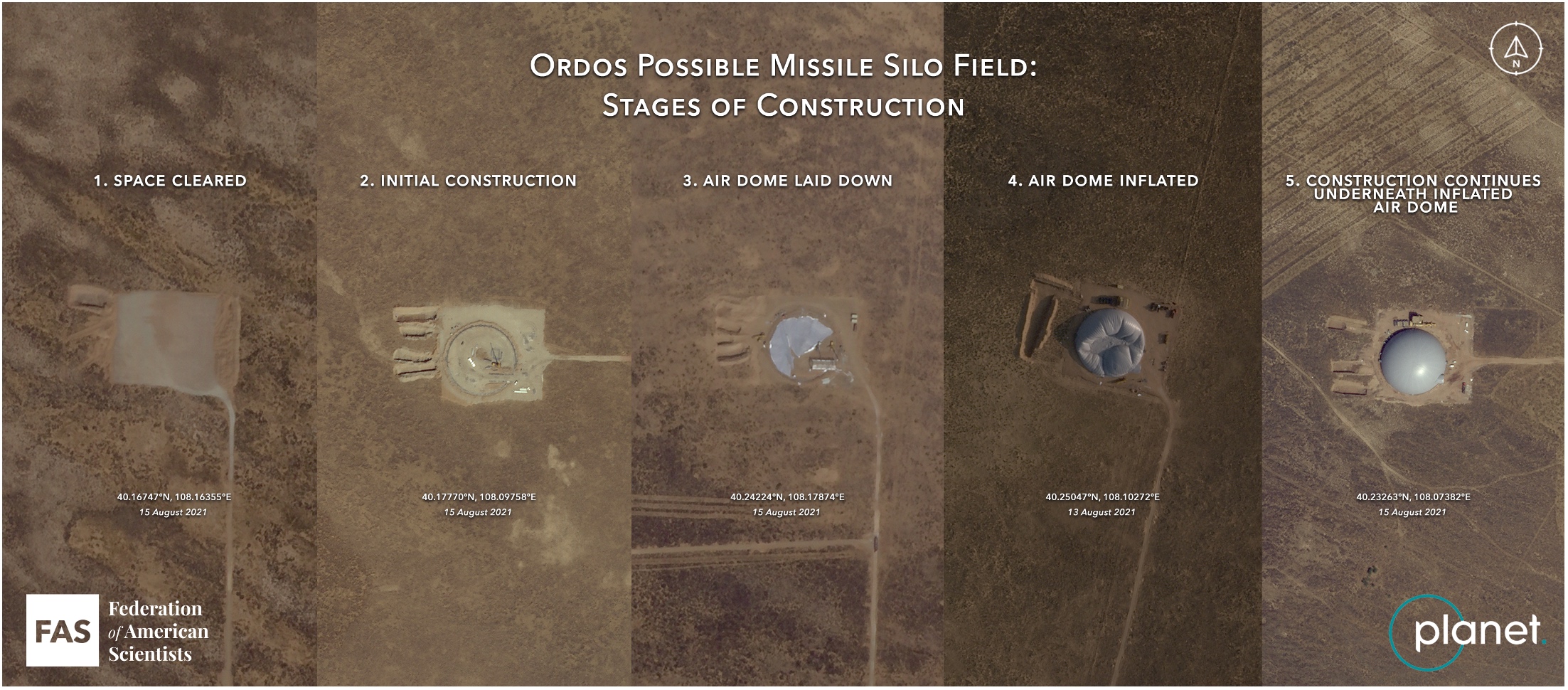

Echoing the findings of the previous year’s China Military Power Report, the NPR suggests that “[t]he PRC likely intends to possess at least 1,000 deliverable warheads by the end of the decade.” According to the NPR, China’s more diverse nuclear arsenal “could provide the PRC with new options before and during a crisis or conflict to leverage nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, including military provocations against U.S. Allies and partners in the region.”

Russia

The NPR presents harsh language about Russia, in particular surrounding its behavior around the invasion of Ukraine. In contrast to the Trump administration’s NPR, the assumptions surrounding a potential low-yield escalate-to-deescalate policy are no longer present; instead the NPR simply states that Russia is diversifying its arsenal and that it views its nuclear weapons as “a shield behind which to wage unjustified aggression against [its] neighbors.” The NPR also suggests that “Russia is pursuing several novel nuclear-capable systems designed to hold the U.S. homeland or Allies and partners at risk, some of which are also not accountable under New START.”

Nuclear Declaratory Policy

The NPR reaffirms long-standing policy about the role of U.S. nuclear weapons but with slightly modified language. This includes: 1) Deter strategic attacks, 2) Assure allies and partners, and 3) Achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.

The NPR reiterates the language from the 2010 NPR that the “fundamental role” of U.S. nuclear weapons “is to deter nuclear attacks” and only in “extreme circumstances.” The strategy seeks to “maintain a very high bar for nuclear employment” and, if employment of nuclear weapons is necessary, “seek to end conflict at the lowest level of damage possible on the best achievable terms for the United States and its Allies and partners.”

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden spoke repeatedly in favor of a no-first-use and sole-purpose policy for U.S. nuclear weapons. But the NPR explicitly rejects both under current conditions.

Interestingly, the NPR states that “hedging against an uncertain future” is no longer a stated (formal) role of nuclear weapons. Hedging has been part of a strategy to be able to react to changes in the threat environment, for example by deploying more weapons or modifying capabilities. The change does not mean that the United States is no longer hedging, but that hedging is part of managing the arsenal, rather than acting as a role for nuclear weapons within U.S. military strategy writ large.

Nuclear Modernization

The NPR reaffirms a commitment to the modernization of its nuclear forces, nuclear command and control and communication systems (NC3), and production and support infrastructure. This is essentially the same nuclear modernization program that has been supported by the past three administrations.

But there are some differences. The NPR also identifies “current and planned nuclear capabilities that are no longer required to meet our deterrence needs.” This includes retiring the B83-1 megaton gravity bomb and cancelling the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). These decisions were expected and survived opposition from defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists.

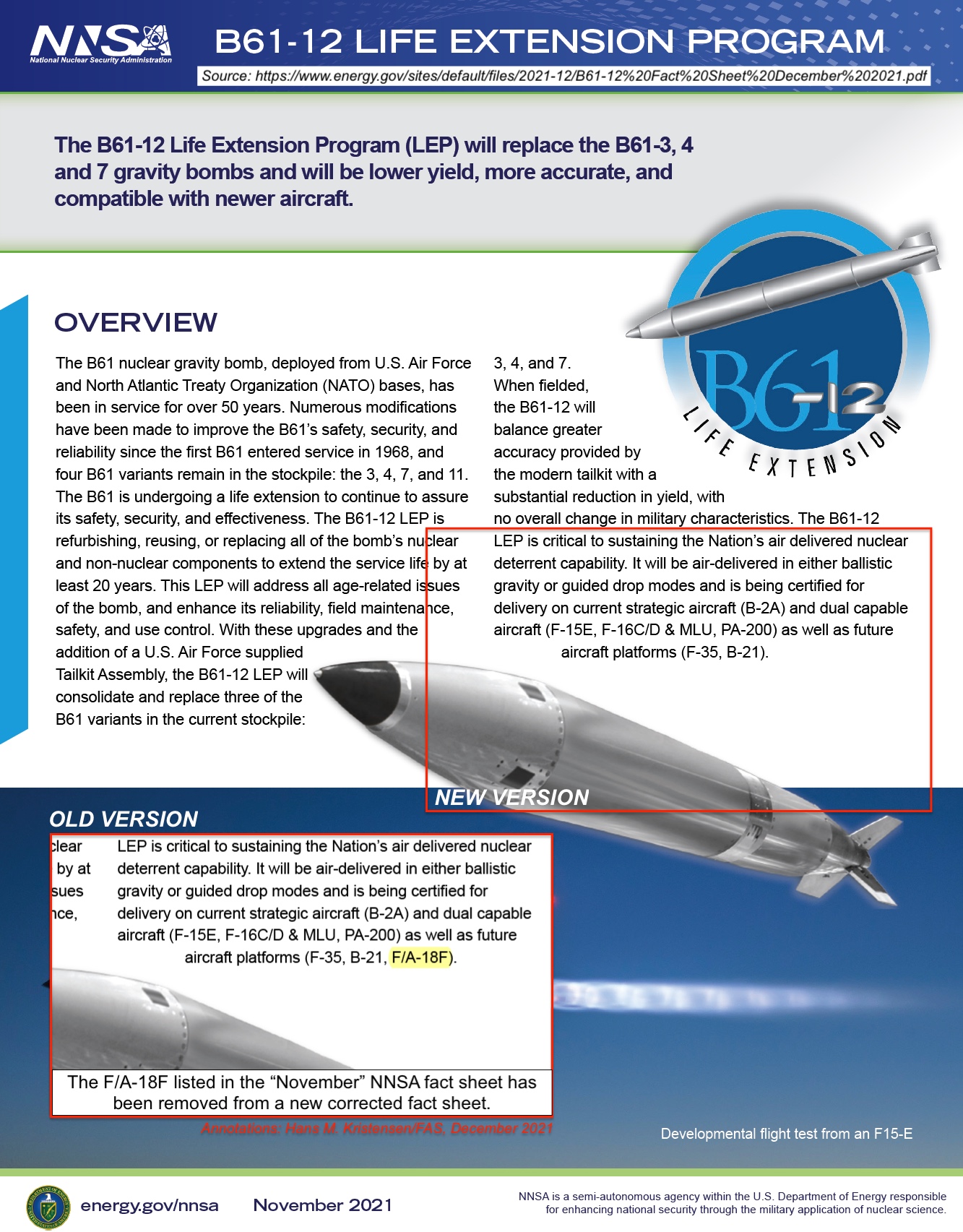

The review also notes that “[t]he United States will work with Allies concerned to ensure that the transition to modern DCA and the B61-12 bomb is executed efficiently and with minimal disruption to readiness.”

Nuclear-Conventional Integration

Although the integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities into strategic deterrence planning has been underway for years, the NPR seeks to deepen it further. It “underscores the linkage between the conventional and nuclear elements of collective deterrence and defense” and adopts “an integrated deterrence approach that works to leverage nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities to tailor deterrence under specific circumstances.”

This is not only intended to make deterrence more flexible and less nuclear focused when possible, but it also continues the strategy outlined in the 2010 NPR and 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons by relying more on new conventional capabilities.

Beyond force structure issues, this effort also appears to be a way to “raise the nuclear threshold” by reducing reliance on nuclear weapons but still endure in regional scenarios where an adversary escalates to limited nuclear use. In contrast, the 2018 NPR sought low-yield non-strategic “nuclear supplements” for such a scenario, and specifically named a Russian so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” scenario as a potentially possibility for nuclear use.

A significant challenge of deeper nuclear-conventional integration in strategic deterrence is to ensure that it doesn’t blur the line between nuclear and conventional war and inadvertently increase nuclear signaling during conventional operations.

Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

The Biden administration’s review contains significantly more positive language on arms control than can be found in the Trump administration’s NPR. The NPR concludes that “mutual, verifiable nuclear arms control offers the most effective, durable and responsible path to achieving a key goal: reducing the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. strategy.”

In that vein, the review states a willingness to “expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START,” as well as an expansive recommitment to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Comprehensive Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). However, the authors take a negative view of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), stating that the United States does not “consider the TPNW to be an effective tool to resolve the underlying security conflicts that lead states to retain or seek nuclear weapons.”

The Trump NPR perceived a rapidly deteriorating threat environment in which potential nuclear-armed adversaries are increasing their reliance on nuclear weapons and follows suit. The review reverses decades of bipartisan policy and orders what would be the first new nuclear weapons since the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, the document expands the use of circumstances in which the United States would consider employing nuclear weapons to include “non-nuclear strategic attacks.”

- Nuclear Posture Review Report, February 2018

- FAS 2018 Nuclear Posture Review Resource Page

- Hans M. Kristensen, “New Data Shows Detail About Final Phase of US New START Treaty Reductions,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, January 2018

- Hans M. Kristensen, “NNSA’s New Nuclear Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, November 2017

- Hans M. Kristensen, “The Flawed Push For New Nuclear Weapons Capabilities,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, June 2017

- Adam Mount, “Trump’s Troubling Nuclear Plan,” Foreign Affairs, February 2018

- Adam Mount, “Letting It Be An Arms Race,” The Atlantic, January 2018

- Adam Mount, “The Case Against New Nuclear Weapons,” Center for American Progress, May 2017

The third Nuclear Posture Review set out from the start to produce a comprehensive public document. In this way, the review served several purposes: it provided an opportunity to interpret President Obama’s Prague commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons, to explain the strategic benefits of the New START treaty and to establish the force structure to comply with it, and served as a prominent and public way of communicating with allies and adversaries. The central compact was that as long as nuclear weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure, and effective deterrent. In this way, the NPR could endorse modernization and sustainment investments while reducing the role and number of nuclear weapons. Though relatively modest in terms of force structure changes, the document’s main innovation was to declare that the United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against nonnuclear weapons states that are party to and remain in compliance with their obligations under the Nonproliferation Treaty.

- Nuclear Posture Review Report, April 2010

- Report on Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United States, June 2013

- Hans M. Kristensen, “The Nuclear Posture Review,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, April 8, 2010

- Hans M. Kristensen, “Nuclear Posture Review to Reduce Regional Role of Nuclear Weapons,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, February 22, 2010

- Hans M. Kristensen, “New Nuclear Weapons Employment Guidance Puts Obama’s Fingerprint on Nuclear Weapons Policy and Strategy,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, June 20, 2013

- Hans M. Kristensen, “US Nuclear War Plan Updated Amidst Policy Review,” FAS Strategic Security, April 4, 2013

The second NPR was marked by inventive concepts and poor public relations. The intention was to produce a classified document that would be briefed publicly. In open testimony, Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith described the NPR as an attempt rethink deterrence for a world where Russia was no longer an enemy. The nation’s strategic posture would no longer depend on Mutual Assured Destruction, but one Feith said would have “the flexibility to tailor military capabilities to a wide spectrum of contingencies.” Operational concepts would rely more on prompt conventional strike and defensive capabilities. To enhance flexibility, the NPR seemed to endorse development of new earth-penetrating warheads and also required a responsive infrastructure that could quickly produce and test new capabilities if a threat arose. Moving away from MAD allowed for a reduction of deployed warheads below 2,200, but the NPR mandated no further modifications to force structure. Three months after the initial briefing, selections of the classified report leaked to the media and were widely criticized by arms control groups and foreign officials. Fairly or unfairly, many read the leaked sections as blurring the line between nuclear and conventional weapons and refusing to accept mutual vulnerability. Administration officials scrambled to clarify but never fully dispelled concerns, leaving more questions than answers.

- “Excerpts of Classified Nuclear Posture Review,” 1/2002

- Amy F. Woolf, “The Nuclear Posture Review,” Congressional Research Service, 1/2002

- Douglas J. Feith, Testimony before Senate Armed Services Committee on the Nuclear Posture Review, 2/2002

- Keith B. Payne, “The Nuclear Posture Review: Setting the Record Straight,” United States Nuclear Strategy Forum, 2005

- Hans M. Kristensen, “STRATCOM Cancels Controversial Preemption Strike Plan,” FAS Strategic Security, July 25, 2008

- Hans M. Kristensen, “The RISOP is Dead – Long Live RISOP-Like Nuclear Planning,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, July 21, 2008

- Hans M. Kristensen, Robert S. Norris, and Ivan Oelrich, From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence, FAS Occasional Paper No. 7, April 2009

- Hans M. Kristensen, “White House Guidance Led to New Nuclear Strike Plans Against Proliferators, Document Shows,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, November 5, 2007

- Hans M. Kristensen, “The Role of U.S. Nuclear Weapons: New Doctrine Falls Short of Bush Pledge,” Arms Control Today, 9/2005

President Clinton ordered the first NPR to examine the role of nuclear weapons after the end of the Cold War. A five-person steering group led six working groups. The established process broke down in the summer of 1994 over tensions the steering group and the military stakeholders. In the end, the review failed to generate a unitary document; its results were briefed to the press and to Congress. The 1994 NPR established a force structure to comply with the START II Treaty and ordered cuts to each leg of the triad: conversion of four Ohio-class submarines and all B-1 bombers to conventional missions, reduction in B-52 and Minuteman III inventories, and elimination of Minuteman II and Peacekeeper ICBMs. Secretary of Defense Bill Perry summarized the NPR as an attempt to provide leadership for further reductions while hedging against the emergence of threats.

- Office of Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs), “DOD Review Recommends Reduction in Nuclear Force,” 9/1994

- US Strategic Command, “Overview of Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) Results,” 9/1994

- John Deutch and Adm. William Owens, Senate Armed Services Committee “Briefing on the Results of the Nuclear Posture Review,” 9/1994

- Hans M. Kristensen, “The 1994 Nuclear Posture Review,” nukestrat.com, July 8, 2005

FAS Expert Analysis

Adam Mount, “The Biden Nuclear Posture Review: Obstacles to Reducing Reliance on Nuclear Weapons,” Arms Control Today, January/February 2022

Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda, “After Trump Secrecy, Biden Administration Restores US Nuclear Weapons Transparency,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, 6 October 2021

NATO Steadfast Noon Exercise And Nuclear Modernization in Europe

The Steadfast Noon exercise will practice employment of non-strategic nuclear weapons, like this unarmed B61-4 nuclear gravity bomb dropped by an F-15E from the 48th Fighter Wing at RAF Lakenheath. Image: Sandia National Laboratories.

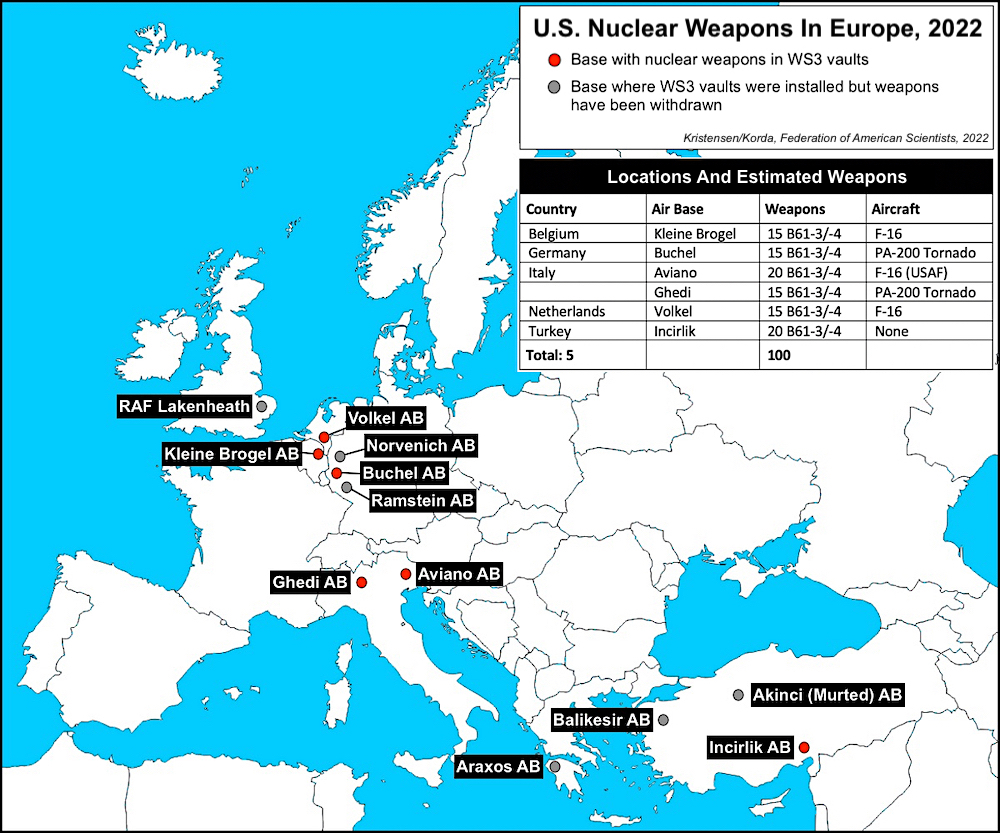

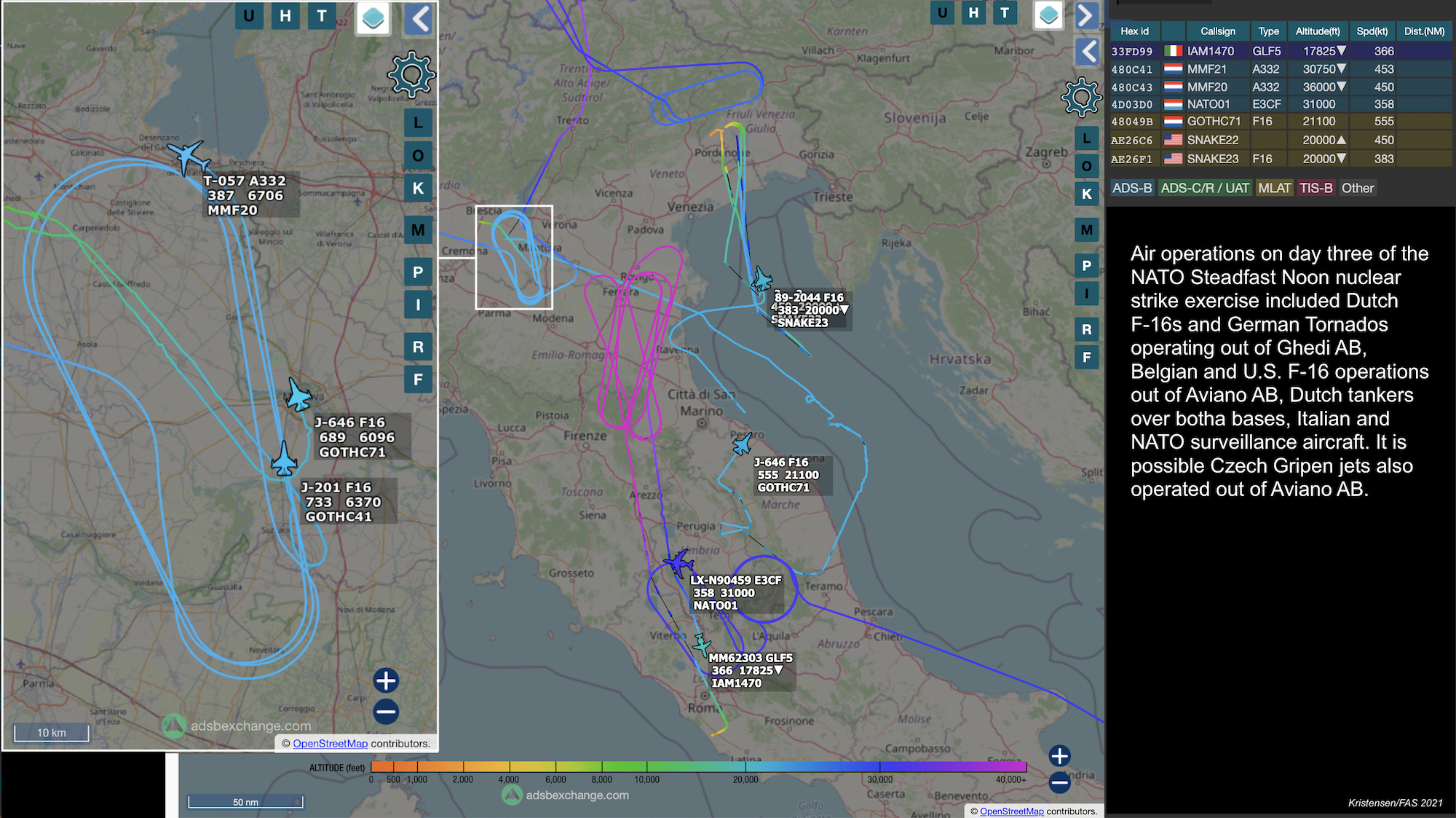

[Updated version] Today, Monday October 17, 2022, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) will begin a two-week long exercise in Europe to train aircrews in using U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs. The exercise, known as Steadfast Noon, is centered at Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium, one of six airbases in Europe that store U.S. nuclear bombs. The exercise takes place midst significant modernizations at nuclear bases across Europe.

Steadfast Noon exercises are held once every year, but this year is unique because the exercise will take place during the largest conventional war in Europe since World War II with considerable tension and uncertainty resulting from Russia’s war in Ukraine. Moreover, Steadfast Noon is expected to more or less coincide with a large Russian strategic nuclear exercise. For NATO officials, other than Putin’s war in Ukraine, this is all routine. But for the public, it is but the latest development in rising tensions and unprecedented fears about nuclear war.

According to NATO, Steadfast Noon will involve 14 countries (less than half of the 30 NATO allies) and up to 60 aircraft. That involves fourth-generation F-16s and F-15Es as well as fifth-generation F-35A and F-22 fighter jets. A number of tankers and surveillance aircraft will also take part. Although the exercise is practicing NATO’s non-strategic nuclear forces, a couple of U.S. strategic B-52 bombers will also participate. Training flights will take place over Belgium and the United Kingdom as well as over the North Sea. There might also be flights over Germany and the Netherlands.

Practicing Nuclear Bomb Sharing

The Steadfast Noon exercise will practice a controversial arrangement known as nuclear sharing, under which the United States installs nuclear equipment on fighter jets of select non-nuclear NATO countries and train their pilots to carry out nuclear strike with U.S. nuclear bombs.

The arrangement is controversial because the United States as a party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) has promised not to hand over nuclear weapons to other countries, and the non-nuclear countries in the sharing arrangement have promised not to receive nuclear weapons from the nuclear weapon states. In peacetime the nuclear weapons are under U.S. control, but the arrangement means that they would be handed over to the non-nuclear country in war time. The arrangement was in place before the NPT was signed so it is not a violation of the letter of the treaty. But it can be said to violate the spirit and has been an irritant for years.

Under supervision by U.S. Air Force personnel, German Air Force personnel is practicing loading of a U.S. B61-4 nuclear bomb shape on a German Tornado fighter jet. In a war, German pilots could be given control of U.S. nuclear bombs. Image: Der Spiegel.

“If NATO was to conduct a nuclear mission in a conflict,” NATO says, “the B-61 [sic] weapons would be carried by certified Allied aircraft…However, a nuclear mission can only be undertaken after explicit political approval is given by NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) and authorisation is received from the US President and UK Prime Minister.” It is unclear why the U.K. Prime Minister would have to authorize employment of U.S. nuclear weapons, and unless NATO territory had been attacked with nuclear weapons first, it seems unlikely that the 29 countries in the NPG would be able to agree to approve of employment of non-strategic nuclear weapons from bases in Europe.

NATO disclosed earlier this year that seven NATO countries contribute dual-capable aircraft to the nuclear sharing mission. The countries were not identified but five are widely known: Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, and the United States. The sixth country is probably Turkey (despite rumors that it was no longer part of the mission), in which case some Turkish F-16s are still equipped to deliver B61 bombs. The seventh country was a mystery, but it turns out it is Greece. Although Greece no longer stores nuclear weapons (they were withdrawn in 2001) and doesn’t have a committed fighter unit, it has a reserve units and a contingency mission. Like other allies (except France), Greece is fully involved in the NPG.]

Nuclear Base Modernizations

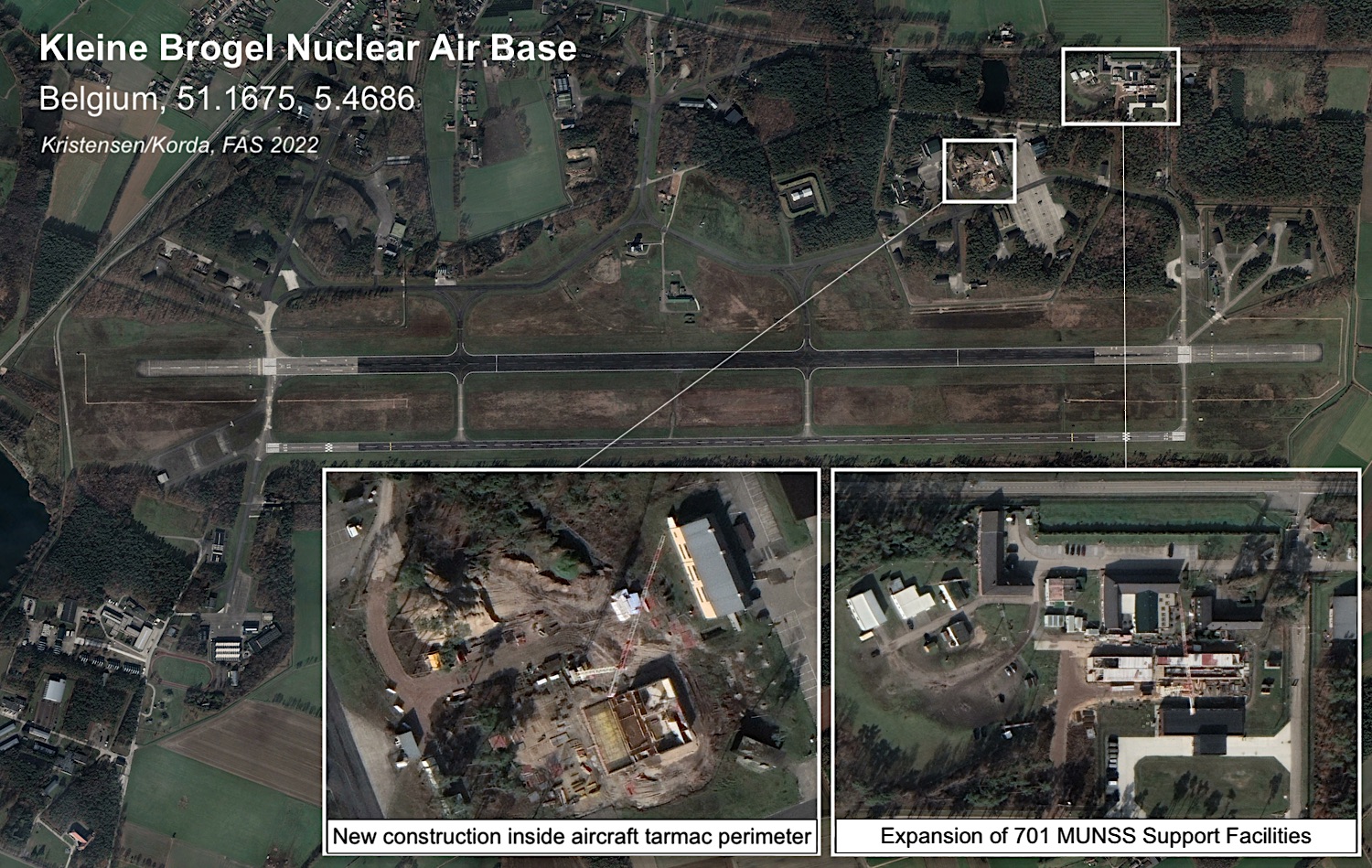

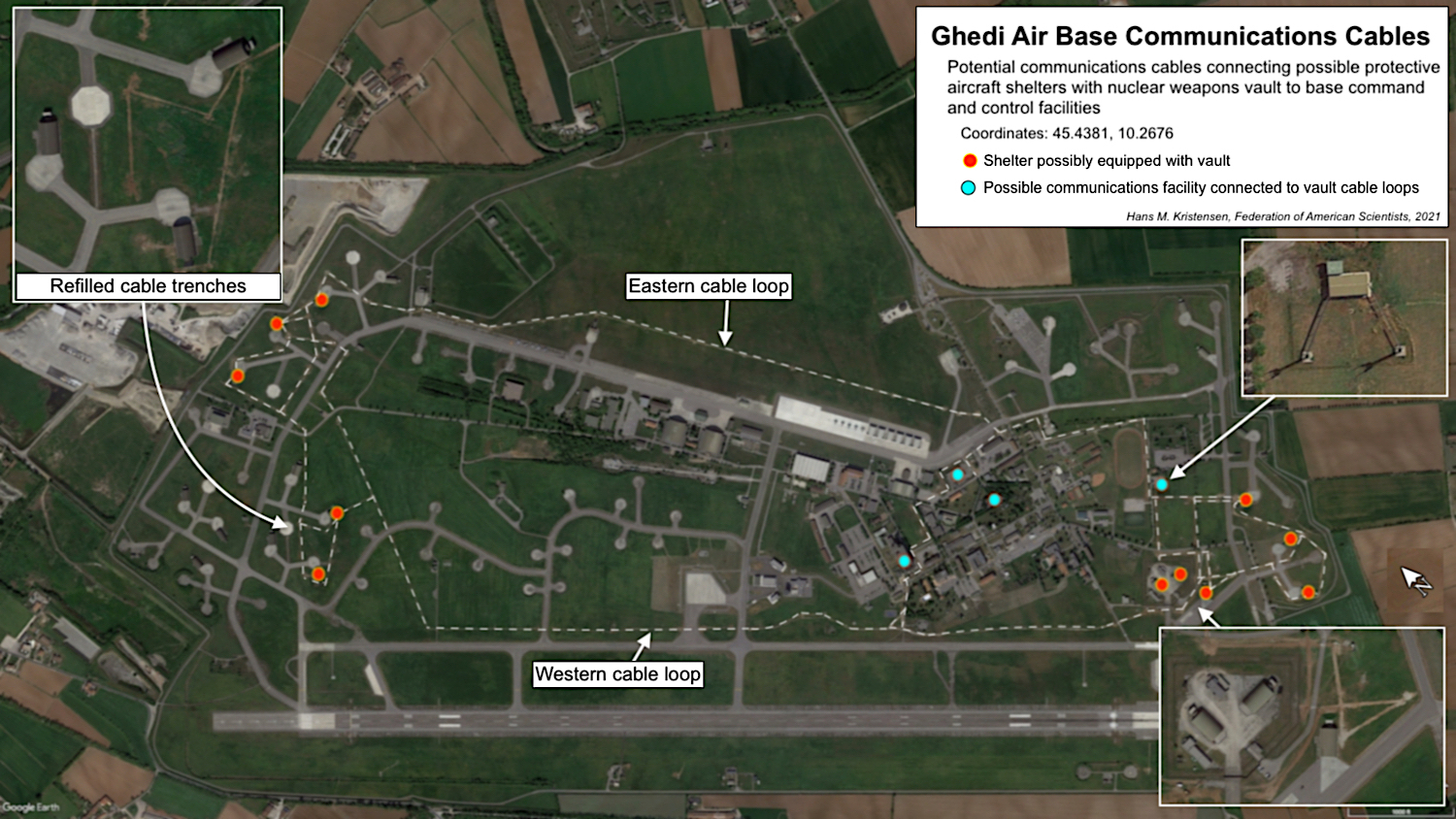

During the past several years, the nuclear bases and the infrastructure that support the nuclear sharing mission in Europe have been undergoing significant upgrades, including cables, command and control systems, weapons maintenance and custodial facilities, security perimeters, and runway and tarmac areas.

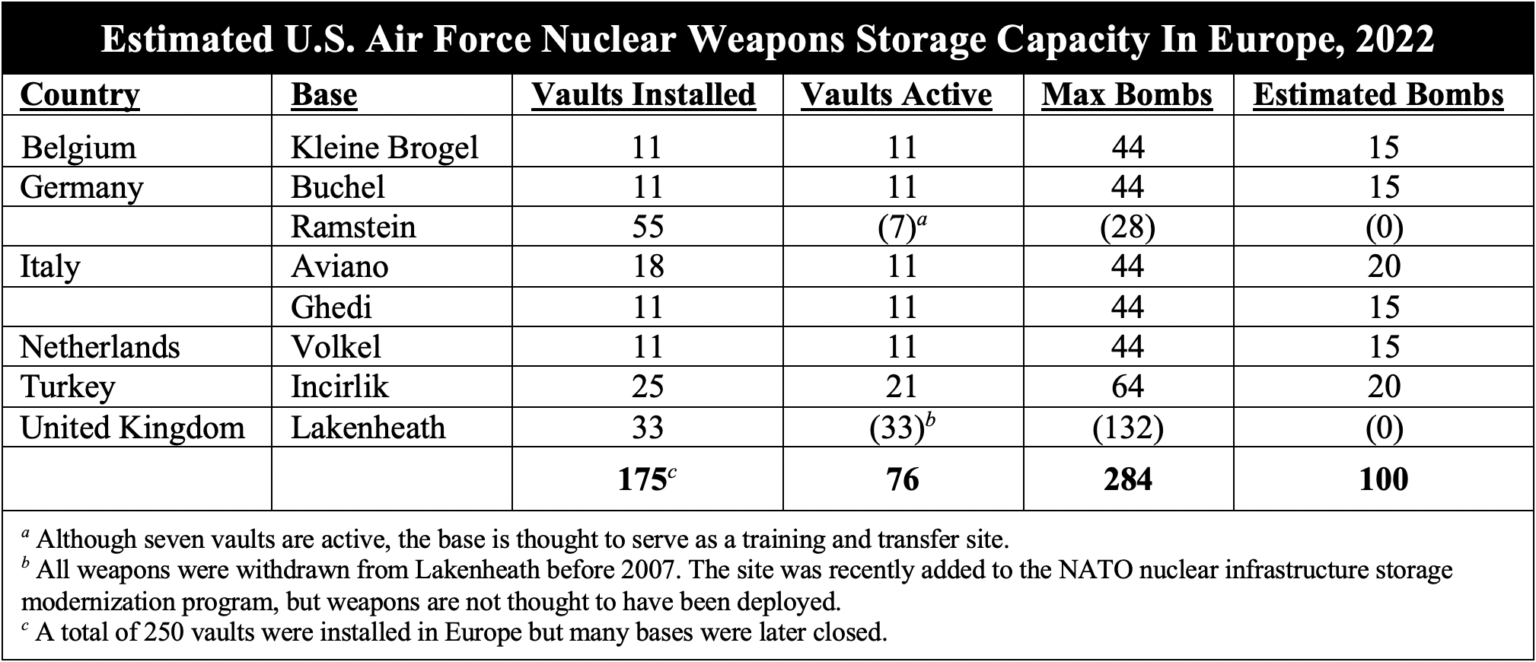

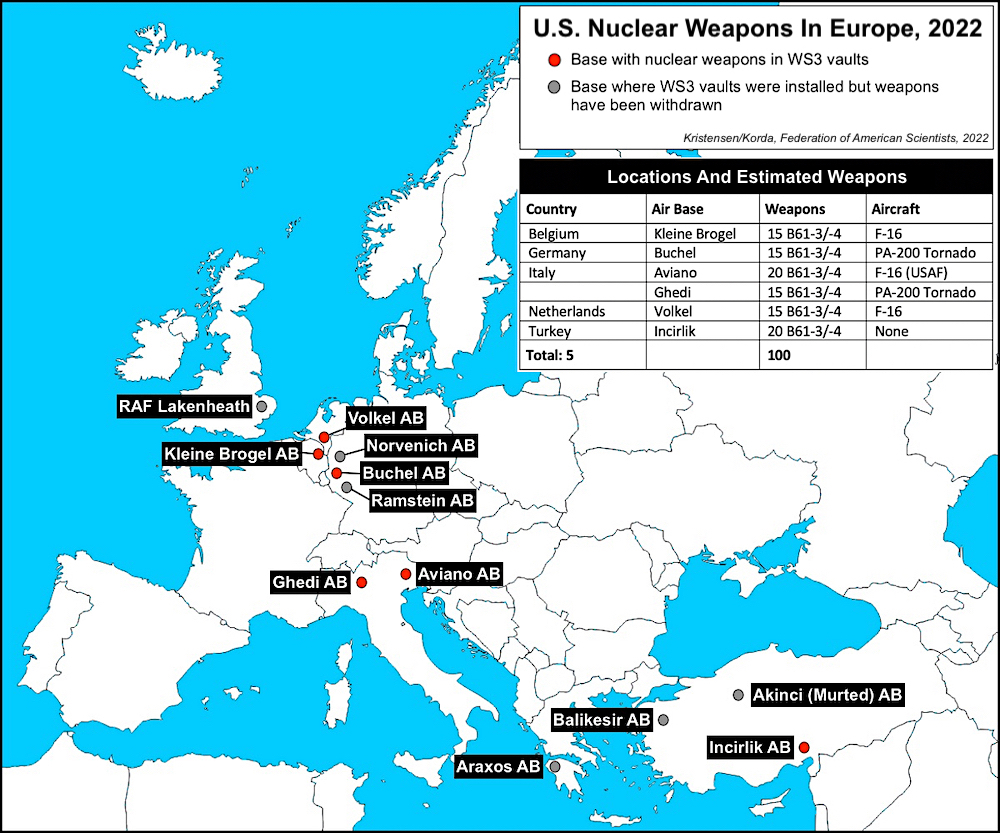

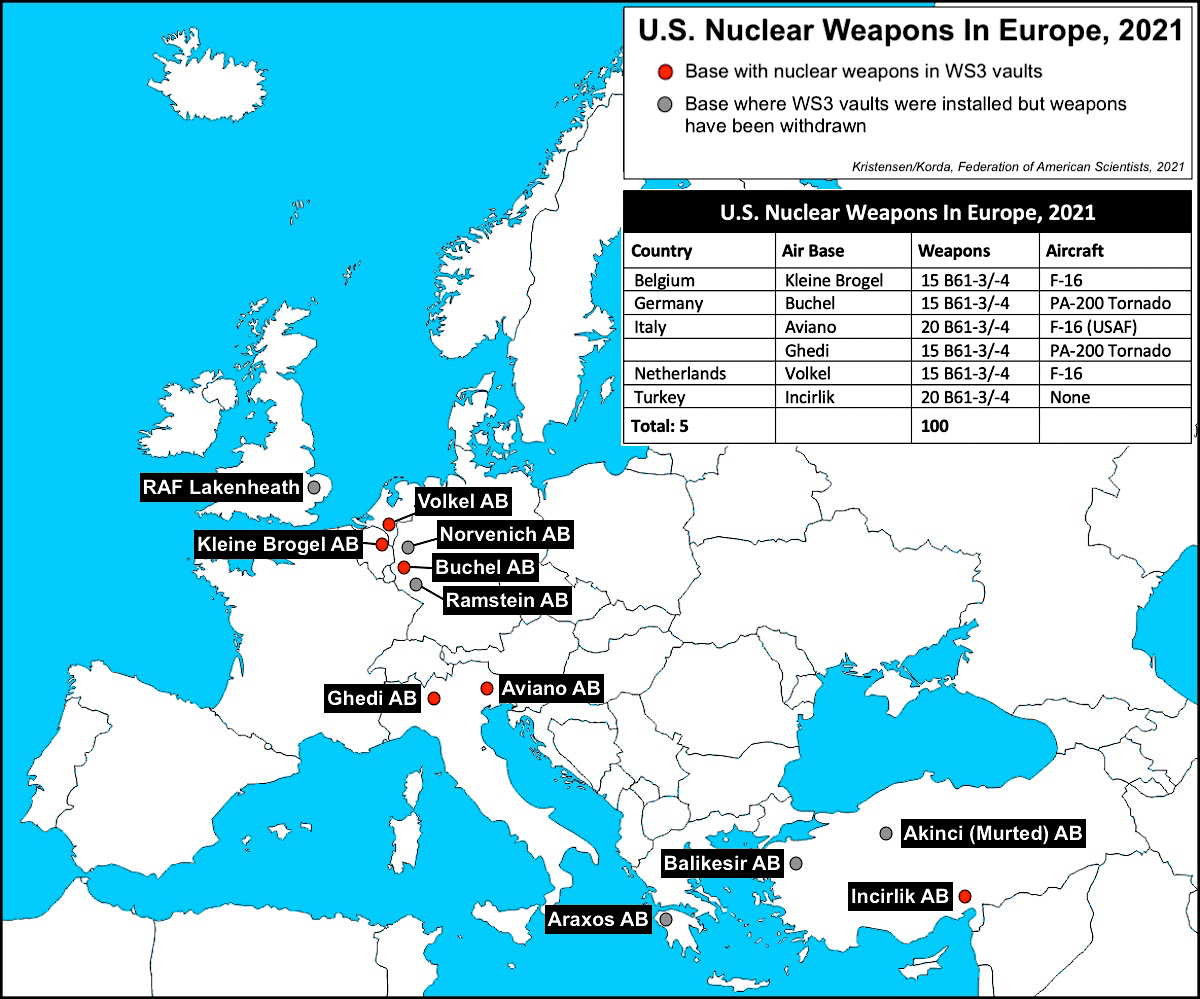

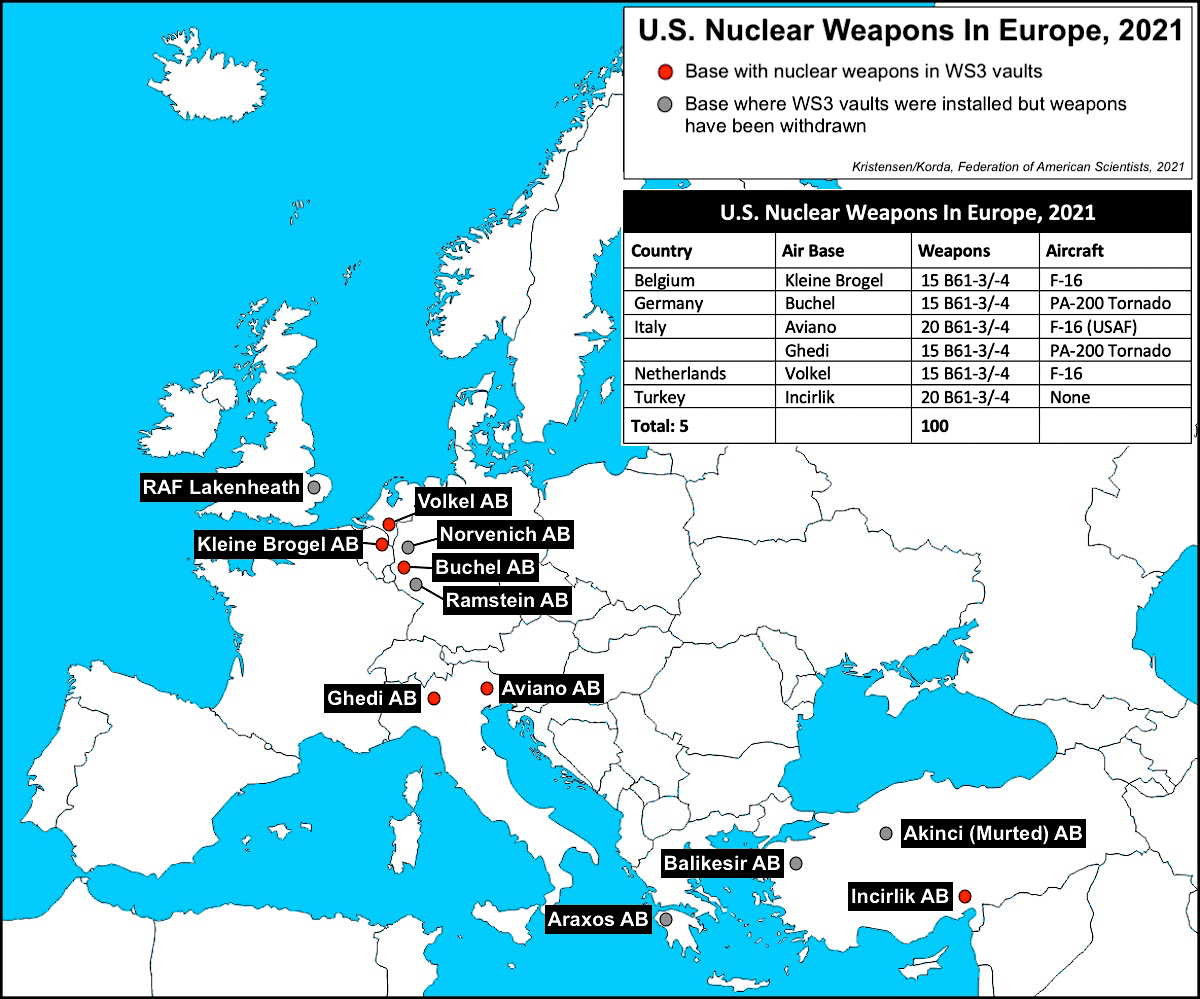

There are currently six active sites in Europe that store U.S. nuclear bombs: Kleine Brogel air base in Belgium, Büchel air base in Germany, Aviano and Ghedi air bases in Italy, Volkel air base in the Netherlands, and possibly Incirlik in Turkey. The estimated number of weapons at each site is based on the number of active vaults, aircraft, and other information.

Each of these bases have one or two dozen active vaults (Weapons Storage Security System, WS3) inside as many protective aircraft shelters. Ramstein air base in Germany used to be the largest storage site in Europe but only 7 vaults remain active possibly for training and transfer. All weapons were withdrawn from Lakenheath before 2007 but the United Kingdom was recently added to the nuclear infrastructure storage modernization program, which means there are now eight active WS3 sites in Europe.

The modernizations at the various bases vary depending on capacity, location, and host country. At Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium, the host base for the Steadfast Noon exercise this year, the 701st Munition Support Squadron quarters have been significantly expanded with a drive-through facility for nuclear weapons maintenance trucks. Other construction includes a major facility inside the aircraft tarmac perimeter area, a new control tower, and upgrades of underground cables and the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system.

At Büchel Air Base in Germany, construction is underway on the runway. During construction, the Tornados of the 33rd Fighter Wing will be temporarily based at Norvenich Air Base. However, the 10-15 B61 nuclear bombs will remain in the vaults at Büchel. Other recent updates at the base have included underground cables and the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system.

In 2020, as part of a series of visits to bases involved in the nuclear sharing mission, U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Derek C. France, the director of operations, strategic deterrence, and integration for U.S. Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa Headquarters director of operations, strategic deterrence, and integration, visited Büchel Air Base where he received a tour and explanation of a protective aircraft shelter. A picture of the tour shows the vault open and a B61 nuclear bomb shape inside.

U.S. Air Force Maj. Gen. Derek C. France, U.S. Air Forces in Europe – Air Forces Africa Headquarters director of operations, strategic deterrence, and nuclear integration, received a tour of a Protective Aircraft Shelter at Büchel Air Base on October 15, 2020. The image shows a B61 nuclear bomb shape hanging in the elevated vault.

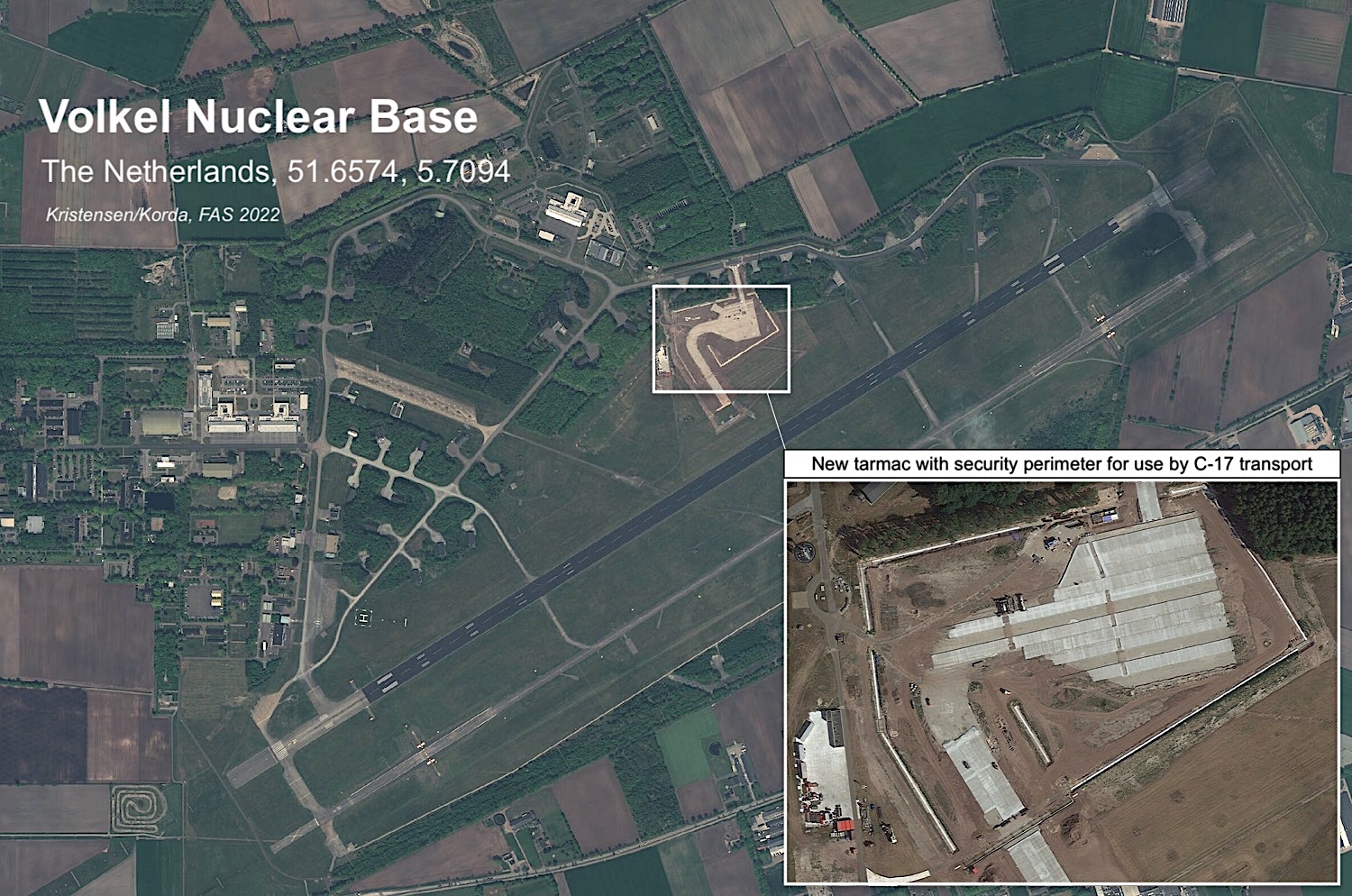

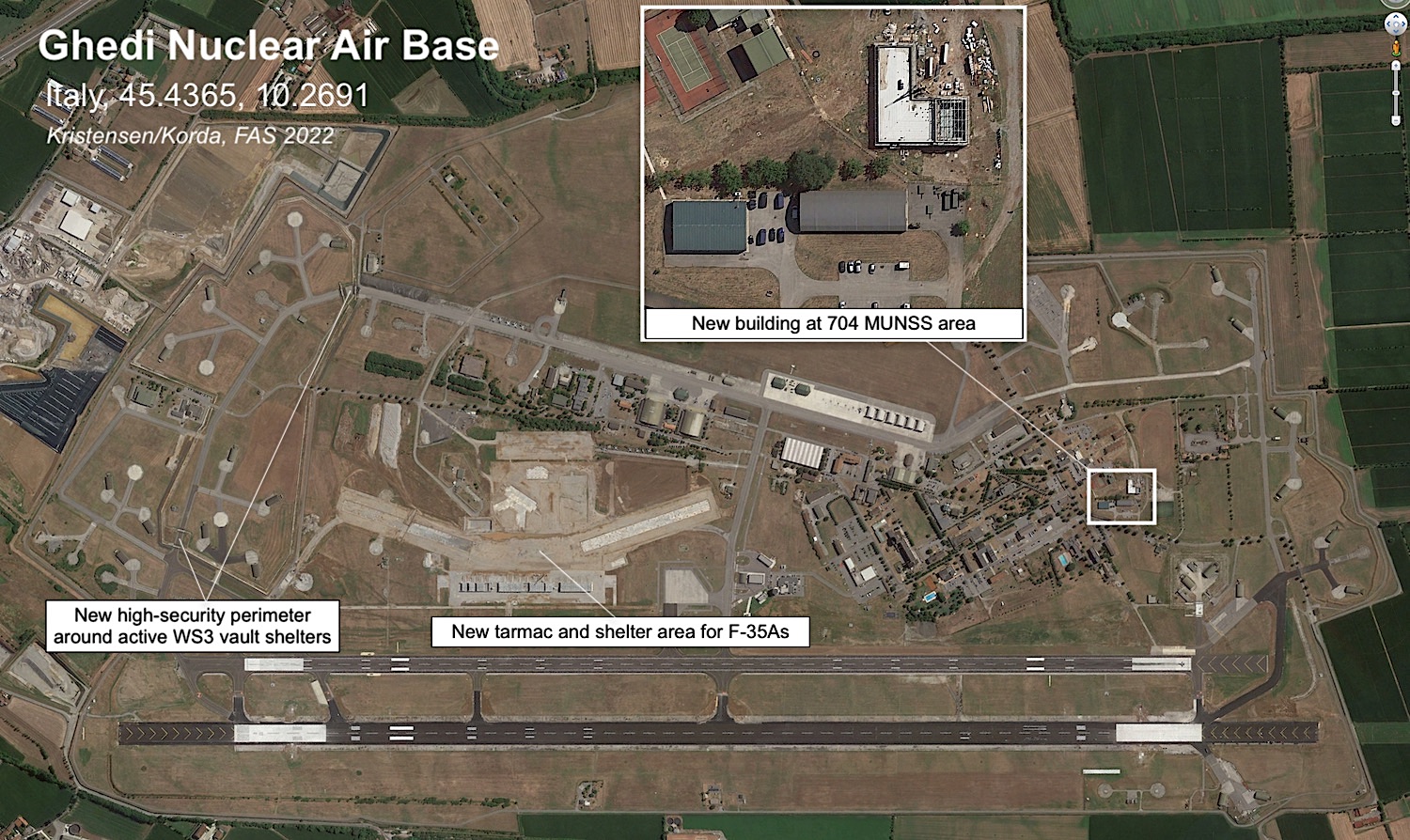

At Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, the most visible modernization currently underway is a major new tarmac area. The construction includes security perimeters probably intended to protect the C-17 aircraft that transport weapons and components to and from the base. Other recent construction the base has included burying underground cables and upgrading the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system used for the WS3 vaults.

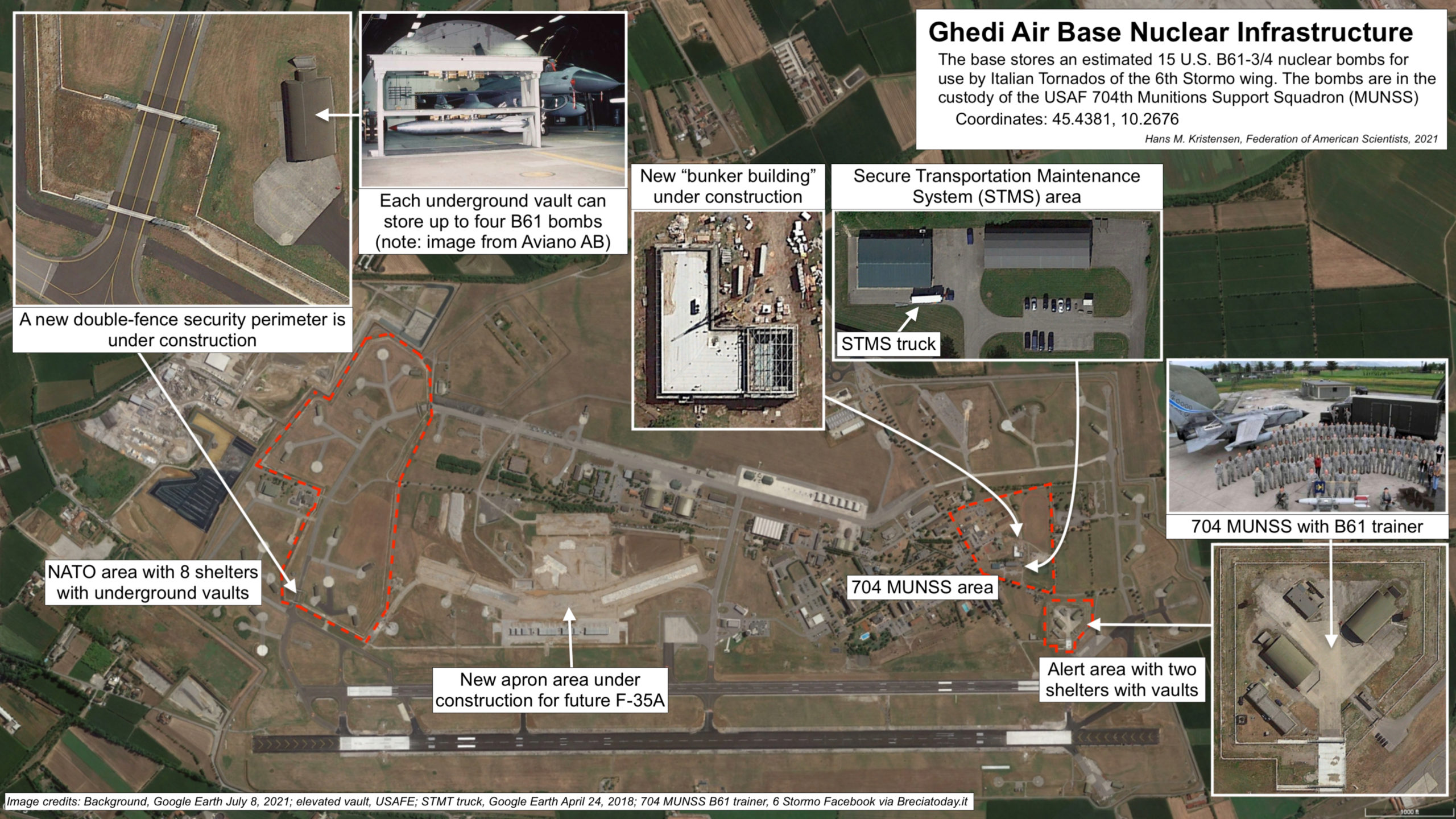

Ghedi Air Base in Italy is undergoing a dramatic upgrade that includes a new tarmac and shelter area for the new F-35A fighter jets that will replace the Tornado jets in the nuclear sharing mission. Work is also underway on what appears to be a drive-through facility for weapons maintenance trucks in the 704th MUNSS area. And a new high-security perimeter has been erected around eight vaults, possibly those of the 11 that are active. This perimeter is similar to perimeters that were constructed at Aviano and Incirlik air bases in 2014-2015. Finally, Ghedi also has received an upgrade of underground cables and the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system used for the WS3 vaults.

Upgrades of Aviano Air Base in Italy and Incirlik Air Base in Turkey happened around 2015 are described in this article: Upgrades At US Nuclear Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk. Since then, installation of new cables between the nuclear vaults at Incirlik Air Base is visible on satellite images.

Weapons Modernization

In addition to modernization of bases and support facilities, delivery systems and weapons are also being upgraded. Five of the seven countries that contribute dual-capable aircraft to the nuclear sharing mission are upgrading to the F-35A fifth-generation fighter-bomber: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and the United States. Turkey was scheduled to upgrade to F-35A but lost the contract after it purchased the Russian S-400 system.

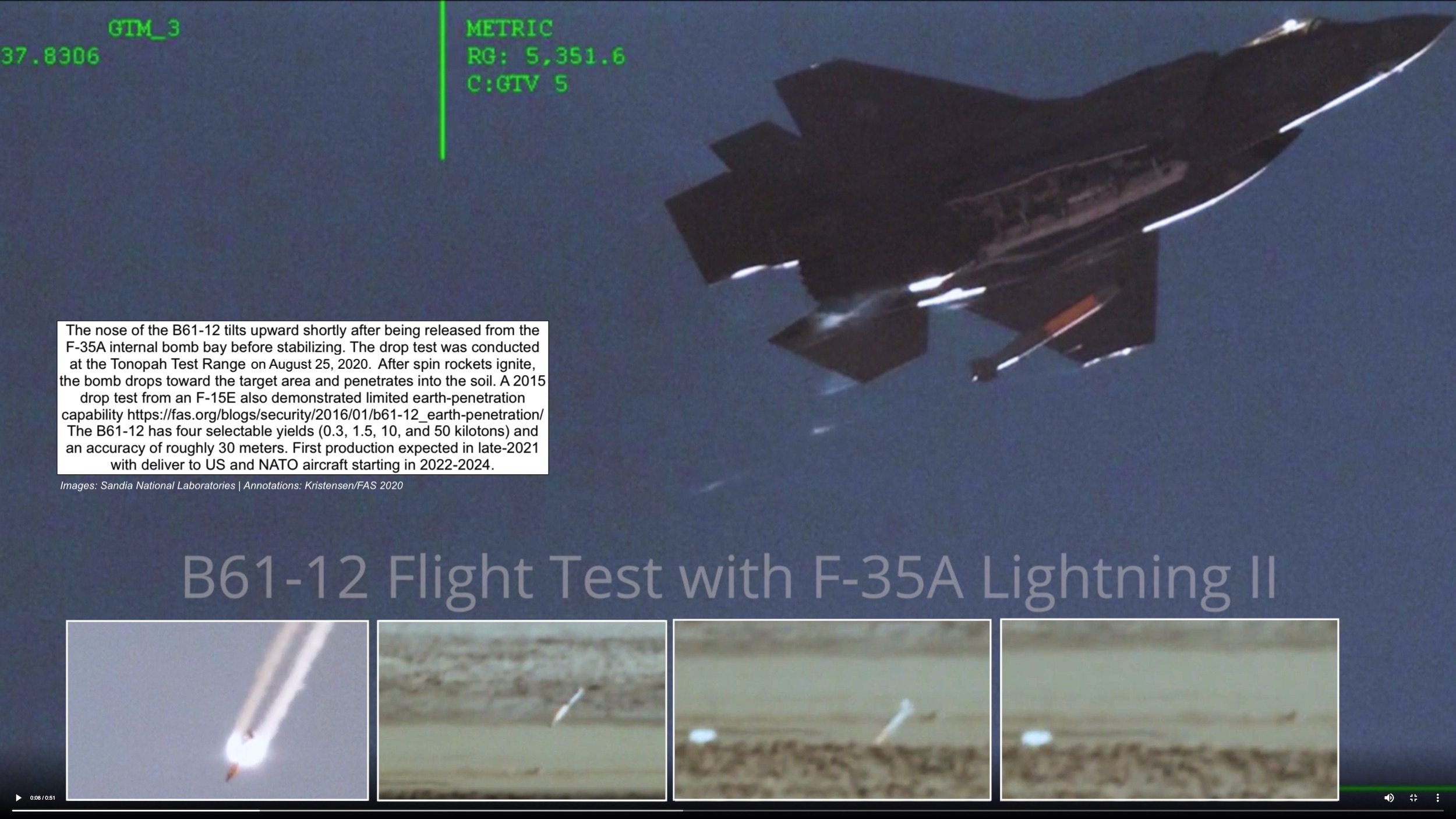

An F-35A test-drops a B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. The enhanced weapon will be compatible with both fighter jets and strategic bombers and begin replacing older B61 versions in Europe from 2023. Image: U.S. Air Force.

Finally, the existing B61 nuclear bombs will soon be replaced by the enhanced B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. Development is essentially complete and full-scale production of about 480 B61-12s is expected to begin soon. The new weapon is thought to have the same yield range as the current B61-4: 0.3, 1.5, 10 and 50 kilotons. Training of the units in Europe to receive the new weapon is scheduled to begin in early-2023 and the first weapons potentially arriving at the first base in late-2023 or 2024.

In addition to the non-strategic fighter jets F-15E, F-16, F-35A, and Tornado, the B61-12 will also be integrated on the B-2 and B-21 strategic bombers. Because of the increased accuracy provided by the tail kit, all the digital aircraft that can make use of it (all except F-16 and Tornado) will be able to hold at risk a wide range of targets. The combination of increased accuracy and lower-yield options on non-strategic and strategic stealth aircraft will significantly increase the capability of the gravity bomb mission.

Each of the WS3 vaults at European bases can hold up to four nuclear bombs. Here crews are practicing loading B61 bombs into a vault: two B61-3/4 bombs on the top rack and two B61-12 bombs on the lower rack. Image: U.S. Air Force, obtained by Joseph Trevithick (The Drive) under FOIA.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Environmental Assessment Reveals Fascinating Alternatives to Land-Based ICBMs

A new Air Force environmental assessment reveals that it considered basing ICBMs in underground railway tunnels––or possibly underwater.

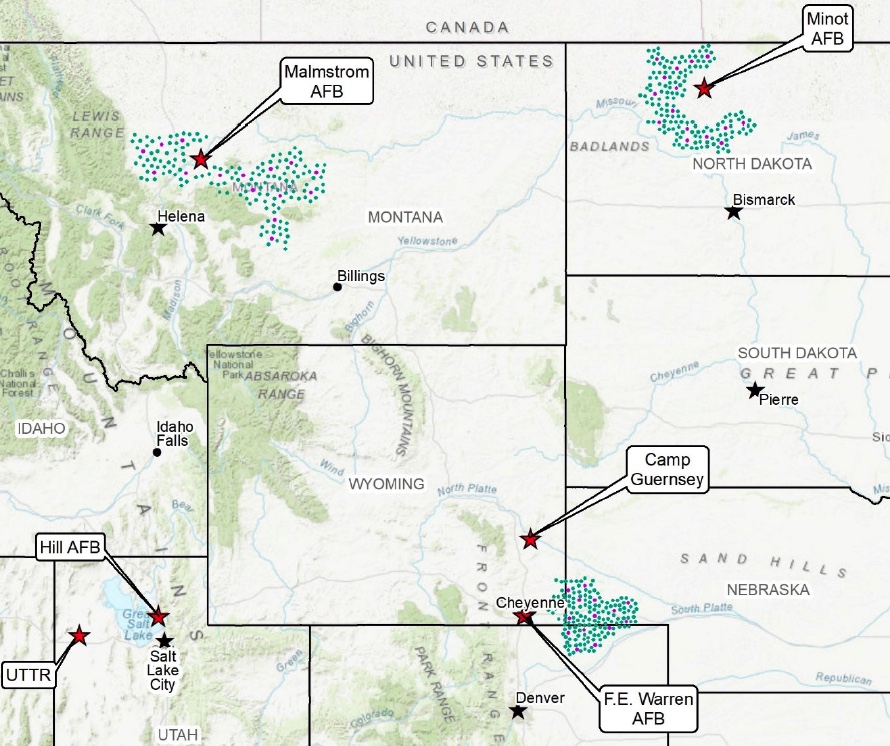

Map of the ICBM missile fields contained within the Air Force’s July 2022 assessment.

On July 1st, the Air Force published its Draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for its proposed ICBM replacement program, previously known as the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD) and now by its new name, “Sentinel.” The government typically conducts an EIS whenever a federal program could potentially disrupt local water supplies, transportation, socioeconomics, geology, air quality, and other related factors.

A comprehensive environmental assessment is certainly warranted in this case, given the tremendous scale of the Sentinel program––which consists of a like-for-like replacement of all 400 Minuteman III missiles that are currently deployed across Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Wyoming, plus upgrades to the launch facilities, launch control centers, and other supporting infrastructure.

Cover page of the Air Force’s July 2022 Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the GBSD.

The Draft EIS was anxiously awaited by local stakeholders, chambers of commerce, contractors, residents, and… me! Not because I’m losing sleep about whether Sentinel construction will disturb Wyoming’s Western Bumble Bee (although maybe I should be!), but rather because an EIS is also a wonderful repository for juicy, and often new, details about federal programs––and the Sentinel’s Draft EIS is certainly no exception.

Interestingly, the most exciting new details are not necessarily about what the Air Force is currently planning for the Sentinel, but rather about which ICBM replacement options they previously considered as alternatives to the current program of record. These alternatives were assessed during in the Air Force’s 2014 Analysis of Alternatives––a key document that weighs the risks and benefits of each proposed action––however, that document remains classified. Therefore, until they were recently referenced in the July 2022 Draft EIS, it was not clear to the public what the Air Force was actually assessing as alternatives to the current Sentinel program.

Missile alternatives

The Draft EIS notes that the Air Force assessed four potential missile alternatives to the current plan, which involves designing a completely new ICBM:

- Reproducing Minuteman III ICBMs to “existing specifications” by washing out and refilling the first- and second-stage rocket boosters; remanufacturing the third stages and Propulsion System Rocket Engine––the ICBM’s post-boost vehicle; and refurbishing and replacing all other subsystems;

The Air Force appears to have ultimately eliminated all four of these options from consideration because they did not meet all of their “selection standards,” which included criteria like sustainability, performance, safety, riskiness, and capacity for integration into existing or proposed infrastructure.

Of particular interest, however, is the Air Force’s note that the Minuteman III reproduction alternative was eliminated in part because it did not “meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs in the context of modern and evolving threats (e.g., range, payload, and effectiveness.” It is highly significant to state that the Minuteman III cannot meet the required performance criteria for ICBMs, given that the Minuteman III currently performs the ICBM role for the US Air Force and will continue to do so for the next decade.

This statement also suggests that “modern and evolving threats” are driving the need for an operationally improved ICBM; however, it is unclear what the Air Force is referring to, or how these threats would necessarily justify a brand-new ICBM with new capabilities. As I wrote in my March 2021 report, “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,”

“With respect to US-centric nuclear deterrence, what has changed since the end of the Cold War? China is slowly but steadily expanding its nuclear arsenal and suite of delivery systems, and North Korea’s nuclear weapons program continues to mature. However, the range and deployment locations of the US ICBM force would force the missiles to fly over Russian territory in the event that they were aimed at Chinese or North Korean targets, thus significantly increasing the risk of using ICBMs to target either country. Moreover, […] other elements of the US nuclear force––especially SSBNs––could be used to accomplish the ICBM force’s mission under a revised nuclear force posture, potentially even faster and in a more flexible manner. […] It is additionally important to note that even if adversarial missile defenses improved significantly, the ability to evade missile defenses lies with the payload––not the missile itself. By the time that an adversary’s interceptor was able to engage a US ICBM in its midcourse phase of flight, the ICBM would have already shed its boosters, deployed its penetration aids, and would be guided solely by its reentry vehicle. Reentry vehicles and missile boosters can be independently upgraded as necessary, meaning that any concerns about adversarial missile defenses could be mitigated by deploying a more advanced payload on a life-extended Minuteman III ICBM.”

Of additional interest is the passage explaining why the Air Force dismissed the possibility of using the Trident II D5 SLBM as a land-based weapon:

“The D5 is a high-accuracy weapon system capable of engaging many targets simultaneously with overall functionality approaching that of land- based missiles. The D5 represents an existing technology, and substantial design and development cost savings would be realized; but the associated savings would not appreciably offset the infrastructure investment requirements (road and bridge enhancements) necessary to make it a land-based weapon system. In addition, motor performance and explosive safety concerns undermine the feasibility of using the D5 as a land-based weapon system.”

The Air Force’s concerns over road and bridge quality are probably justified––missiles are incredibly heavy, and America’s bridges are falling apart at a terrifying rate. However, it is unclear why the Air Force is not confident about the D5’s motor performance, given that even aging Trident SLBMs have performed very well in recent flight tests: in 2015 the Navy conducted a successful Trident flight test using “the oldest 1st stage solid rocket motor flown to date” (over 26 years old), with 2nd and 3rd stage motors that were 22 years old. In January 2021, Vice Admiral Johnny Wolfe Jr.––the Navy’s Director for Strategic Systems Programs––remarked that “solid rocket motors, the age of those we can extend quite a while, we understand that very well.” This is largely due to the Navy’s incorporation of nondestructive testing techniques––which involve sending a probe into the bore to measure the elasticity of the propellant––to evaluate the reliability of their missiles.

As a result, the Navy is not currently contemplating the purchase of a brand-new missile to replace its current arsenal of Trident SLBMs, and instead plans to conduct a second life-extension to keep them in service until 2084. However, the Air Force’s comments suggest either a lack of confidence in this approach, or perhaps an institutional preference towards developing an entirely new missile system. [Note: Amy Woolf helpfully offered up another possible explanation, that the Air Force’s concerns could be related to the ability of the Trident SLBM’s cold launch system to perform effectively on land, given that these very different launch conditions could place additional stress on the missile system itself.]

Basing alternatives

The Draft EIS also notes that the Air Force assessed two fascinating––and somewhat familiar––alternatives for basing the new missiles: in underground tunnels and in “deep-lake silos.”

The tunnel option––which had been teased in previous programmatic documents but never explained in detail––would include “locating, designing, excavating, developing, and installing critical support infrastructure such as rail systems and [launch facilities] for an array of underground tunnels that would likely span hundreds of miles”––and it is effectively a mashup of two concepts from the late Cold War.

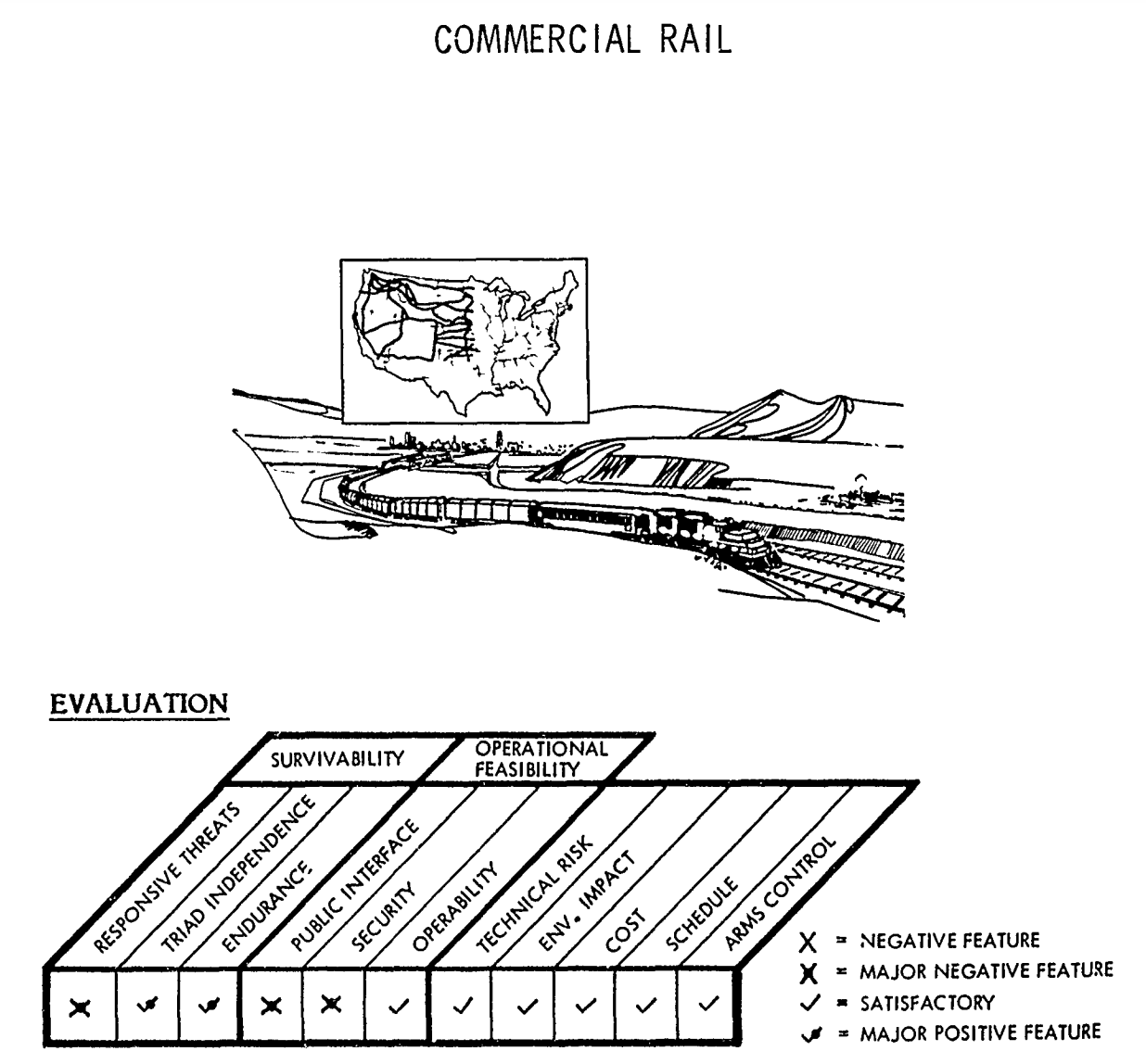

The rail concept was strongly considered during the development of the MX missile in the 1980s, although the plan called for missile trains to be dispersed onto the country’s existing civilian rail network, rather than into newly-built underground tunnels. Both the rail and tunnel concepts were referenced in one of my favourite Pentagon reports––a December 1980 Pentagon study called “ICBM Basing Options,” which considered 30 distinct and often bizarre ICBM basing options, including dirigibles, barges, seaplanes, and even hovercraft!

Illustrations of “Commercial Rail” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

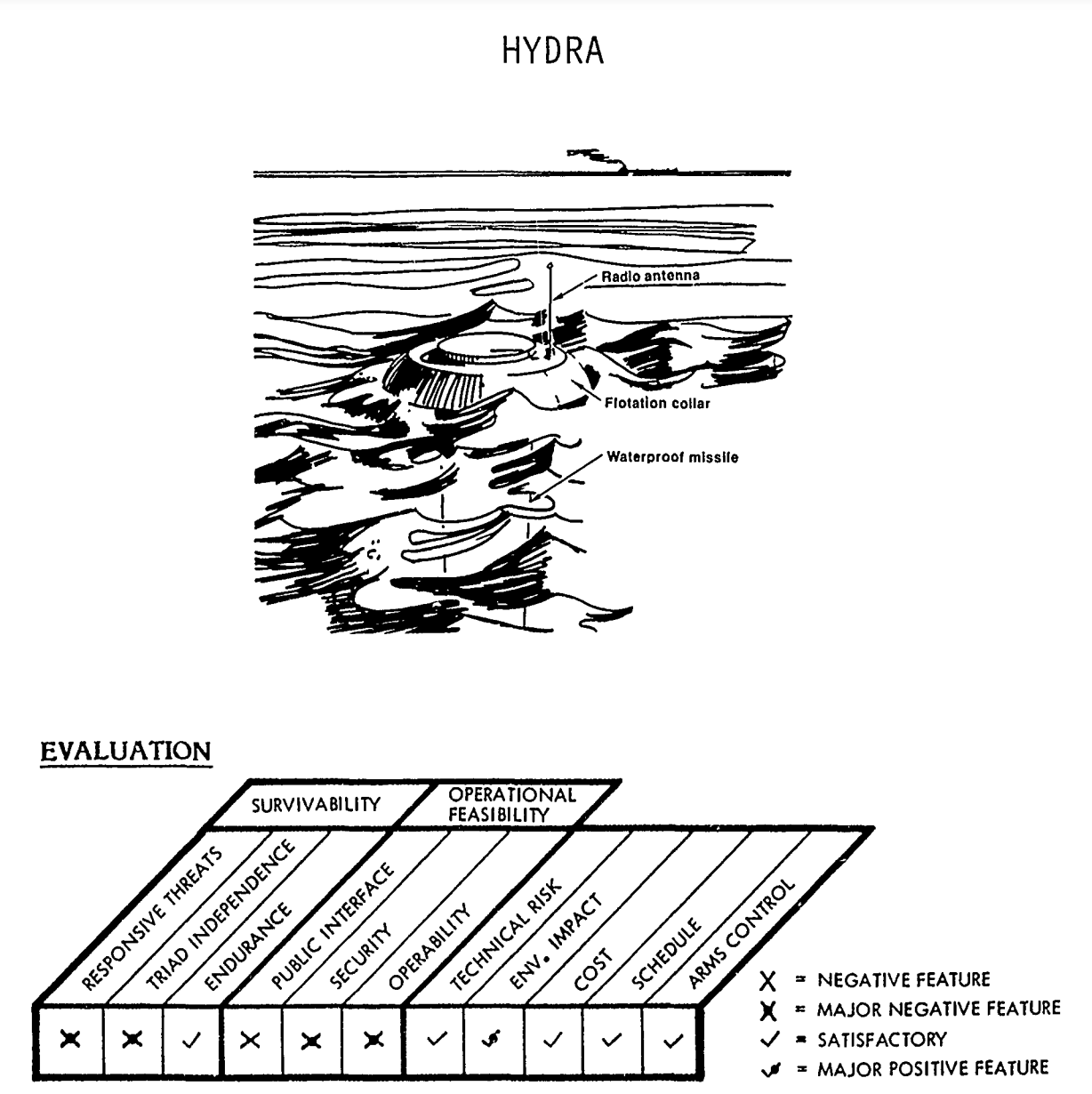

The second option––basing ICBMs in deep-lake silos––was also referenced in that same December 1980 study. The concept––nicknamed “Hydra”––proposed dispersing missiles across the ocean using floating silos, with “only an inconspicuous part of the missile front end [being] visible above the surface.” Interestingly, this raises the theoretical question of whether the Air Force would still maintain control over the ICBM mission, given that the missiles would be underwater.

Illustration of “Hydra” concept from 1980 Pentagon report, “ICBM Basing Options.”

When considering alternative basing modes for the Sentinel ICBM, the Air Force eliminated both concepts due to cost prohibitions, and, in the case of underwater basing, a lack of confidence that the missiles would be safe and secure. This concern was also floated in the 1980 study as well, with the Pentagon acknowledging the likelihood that US adversaries and non-state actors “would also be engaged in a hunt for the Hydras. Not under our direct control, any missile can be destroyed or towed away (stolen) at leisure.”

Another potential option?

In addition to revealing these fascinating details about previously considered alternatives to the Sentinel program, the Draft EIS also highlighted a public comment suggesting that “the most environmentally responsible option” would simply be the reduction of the Minuteman III inventory.

The Air Force rejected the comment because it says that it is “required by law to accelerate the development, procurement, and fielding of the ground based strategic deterrent program;’” however, the public commenter’s suggestion is certainly a reasonable one. The current force level of 400 deployed ICBMs is not––and has never been––a magic number, and it could be reduced further for a variety of reasons, including those related to security, economics, or a good faith effort to reduce deployed US nuclear forces. In particular, as George Perkovich and Pranay Vaddi wrote in a 2021 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, “This assumption that the ICBM force would not be eliminated or reduced before 2075 is difficult to reconcile with U.S. disarmament obligations under Article VI of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.”

The security environment of the 21st century is already very different than that of the previous century. The greatest threats to Americans’ collective safety are non-militarized, global phenomena like climate change, domestic unrest and inequality, and public health crises. And recent polling efforts by ReThink Media, the Union of Concerned Scientists, and the Federation of American Scientists suggest that Americans overwhelmingly want the government to invest in more proximate social issues, rather than on nuclear weapons. To that end, rather than considering building new missile tunnels, it would likely be much more domestically popular to spend money on domestic priorities––perhaps new subway tunnels?

—

Background Information:

- “Siloed Thinking: A Closer Look at the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent,” Federation of American Scientists (Mar. 2021)

- “Environmental Assessment Reveals New Details About the Air Force’s ICBM Replacement Plan,” Federation of American Scientists (Nov. 2020)

- ICBM Information Project, Federation of American Scientists

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and Longview Philanthropy. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Lakenheath Air Base Added To Nuclear Weapons Storage Site Upgrades

The US Air Force base at Lakenheath has been added to the list of nuclear weapons storage sites being upgraded in Europe.

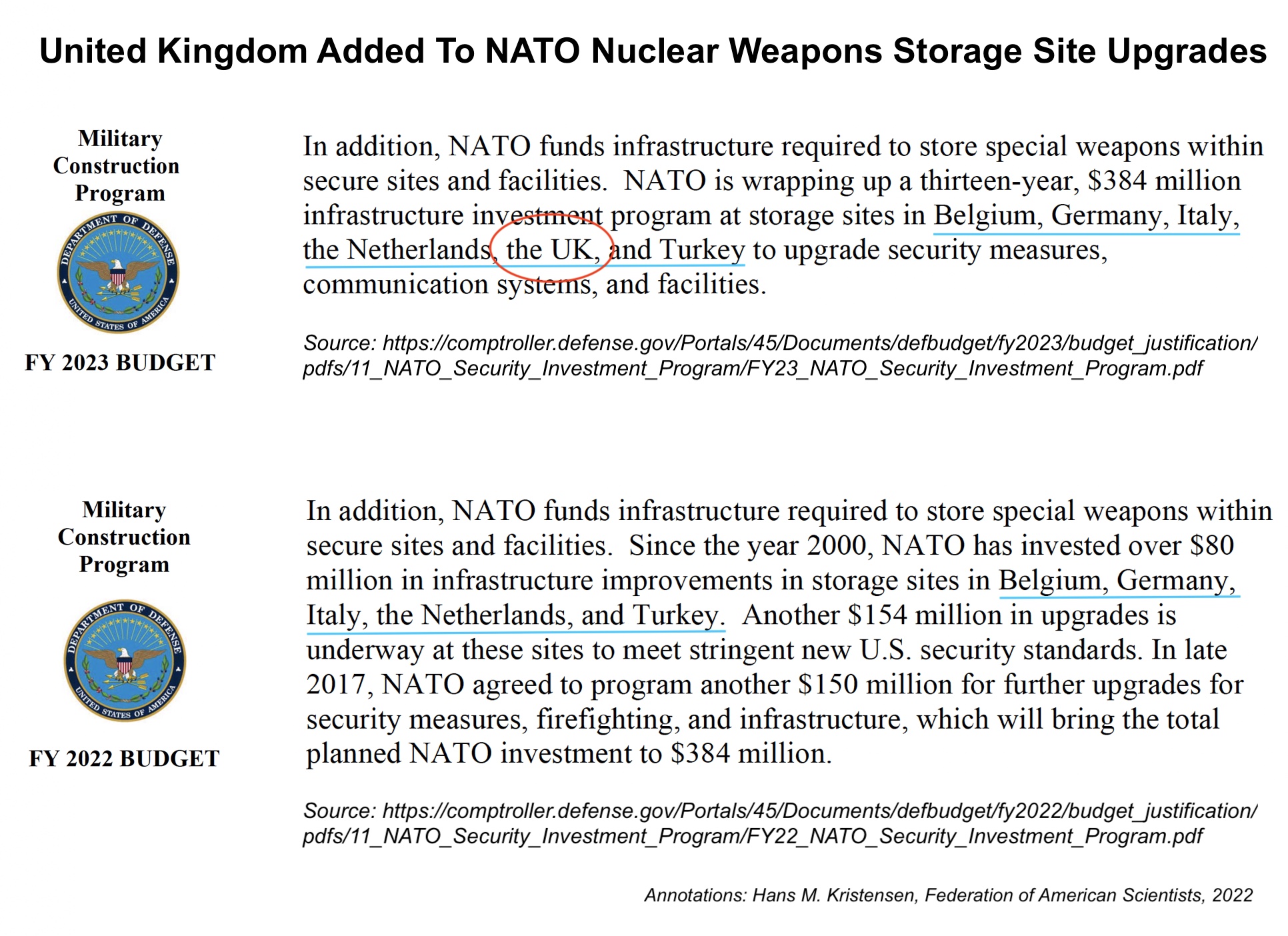

US Defense Department documents show that NATO has quietly added the United Kingdom to the list of nuclear weapons storage locations that are being upgraded.

The documents do not identify the specific facility, but it is believed to be the US Air Base at RAF Lakenheath in southeast England approximately 100 kilometers northeast of London.

Previous budget documents listed “special weapons” storage sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey as receiving upgrades under a 13-year NATO investment program. The Biden administration’s FY2023 defense budget request adds “the UK” to the list (see image below).

The United Kingdom has been added to the list of nuclear weapons storage site locations in Europe. Click on image to view full size.

RAF Lakenheath was not on the list of “active sites” in the 2016 contract for the upgrade of the nuclear weapons storage site in Europe. The budget documents indicate the base has since been added to the list.

The US Air Force used to store nuclear gravity bombs at Lakenheath, which in the 1990s was equipped with 33 underground storage vaults. By the early 2000s, there were a total of 110 B61 gravity bombs in the vaults for delivery by F-15E aircraft of the 48th Fighter Wing.

In 2008, I disclosed that the nuclear weapons had been withdrawn from RAF Lakenheath, the first time since 1954 that the United States did not store nuclear weapons in the United Kingdom.

What’s Going On?

The addition of the United Kingdom to the list of nuclear storage locations being upgraded in Europe signals a change in the nuclear status of RAF Lakenheath. It is unclear if nuclear weapons have been returned to the base yet or NATO is upgrading the base to be capable of receiving nuclear weapons in the future if necessary.

After nuclear weapons were withdrawn nearly two decades ago, the empty storage vaults were kept in caretaker status. The F-15Es fighter-bombers retained their nuclear capability but at a lower operational level. In recent years there have been rumors about nuclear exercises at the base.

A ceremony during a F-22 Raptor visit to RAF Lakenheath in 2016 was held inside an aircraft shelter with an (empty) underground nuclear weapons vault. There are 33 vaults at the base.

The nuclear upgrade comes as RAF Lakenheath is preparing to become the first US Air Force base in Europe equipped with the nuclear-capable F-35A Lightning. The first of the fifth-generation fighter-bombers arrived in December 2021. A total of 24 F-35As will form the 495th Fighter Squadron of the 48th Fighter Wing at the base.

The US Air Force is scheduled to begin training the nuclear units in Europe within the next year to receive the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb that will begin full-scale production next month. It is possible the first B61-12 bombs will be shipped to Europe in 2023, where they will replace the B61-3/-4 bombs currently deployed there.

The US will begin full-scale production of the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb next month, start training units in Europe around the turn of the year, and potentially deploy the first weapons in 2023.

Given NATO’s cautious nuclear response to Russia’s nuclear saber rattling at the start of its invasion of Ukraine, it would be odd if the nuclear upgrade at RAF Lakenheath reflected plans to deploy additional US nuclear bombs to Europe. FAS estimates there currently are roughly 100 nuclear bombs deployed at six air bases in five European countries.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg declared in December 2021, that “we have no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in any other countries than we already have these nuclear weapons as part of our deterrence and that… have been there for many, many years.” Unless NATO has changed its plans since, that seems to be a clear signal that there are currently no plans to deploy nuclear weapons to RAF Lakenheath for now (see map below).

RAF Lakenheath has been an inactive nuclear weapons storage site for nearly two decades. There are currently an estimated 100 US Air Force nuclear bombs stored in Europe.

Rather, the upgrade at RAF Lakenheath could potentially be intended to increase the flexibility of the existing nuclear deployment within Europe, without increasing the number of weapons. Adding RAF Lakenheath as an active site would potentially allow it to receive nuclear weapons from other existing locations in Europe, if that became necessary. Such a contingency could potentially involve receiving weapons withdrawn from Turkey. There are unconfirmed rumors that many of the weapons at Incirlik Air Base in Turkey have already been withdrawn and moved to other bases in Europe.

Readying RAF Lakenheath could potentially also be intended to better realign the overall nuclear posture in Europe with the rapidly deteriorating relations with Russia. This is a delicate issue because changes in NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe might trigger retaliatory changes in Russia’s nuclear posture, including potentially deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus, which recently changed its constitution to allow for just that.

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Amidst Nuclear Saber Rattling, New START Treaty Demonstrates Importance

Shortly after Russian military forces invaded Ukraine and President Vladimir Putin said that he had ordered Russian nuclear forces on high combat alert – apparently to deter the United States from getting directly involved, and the United States condemned the statement as “unacceptable” nuclear saber rattling but refused to respond in kind, the two vehemently opposed countries did something amazing: They exchanged factual information about the status of their strategic nuclear forces as required under the New START Treaty.

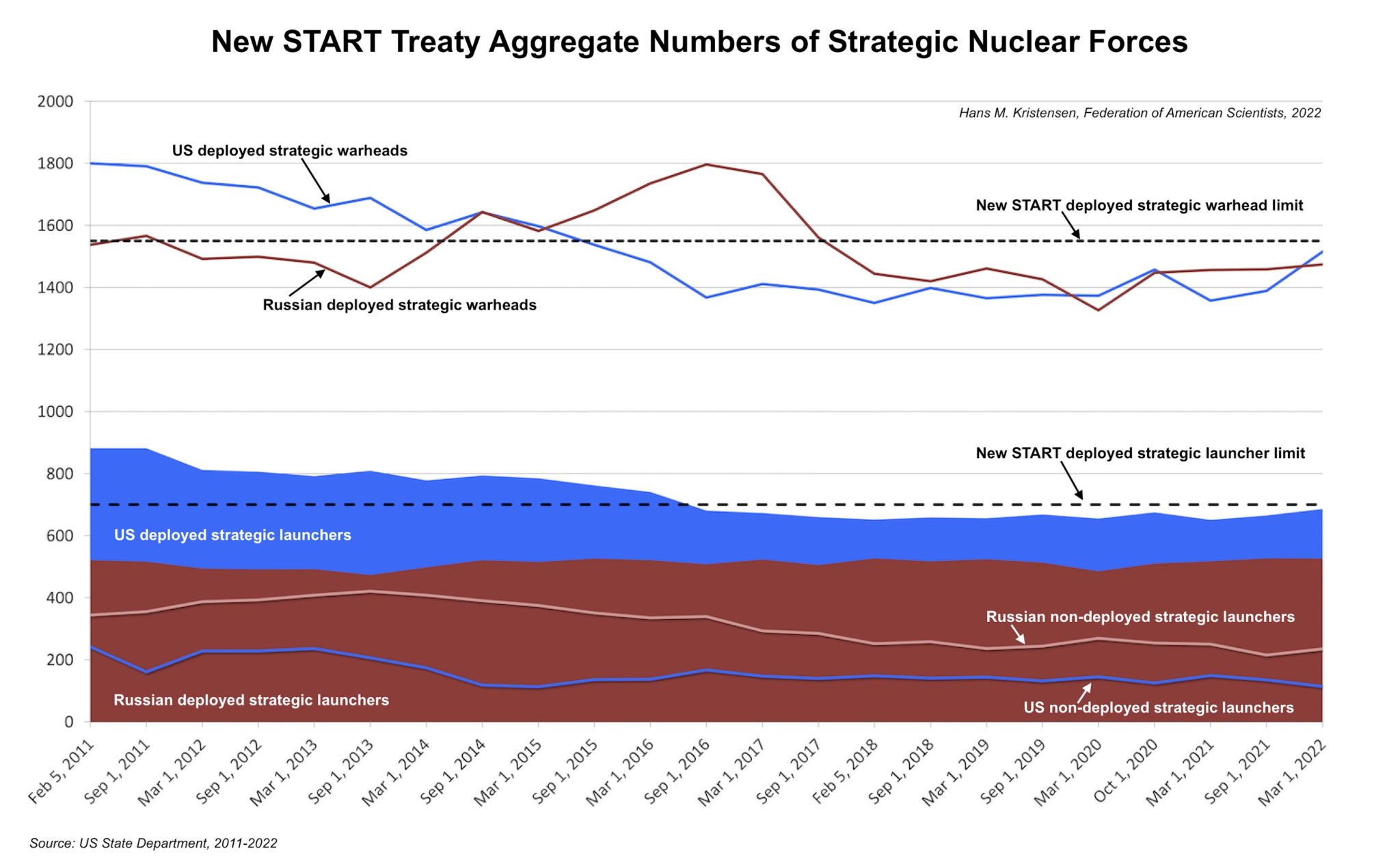

Yesterday, the US State Department published the unclassified bits of that data exchange. It shows that both countries were below the limits set by the treaty for deployed strategic nuclear forces: 1,550 warheads attributed to 700 deployed long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers.

At a time when direct contacts are being curtailed, antagonism runs high, and trust completely lost, it is nothing short of amazing that Russia and the United States continue to abide by the New START treaty and exchange classified information as if nothing had happened.

The reason is clear. Despite their differences, they both have a keen interest in keeping the other country’s long-range nuclear forces in check.

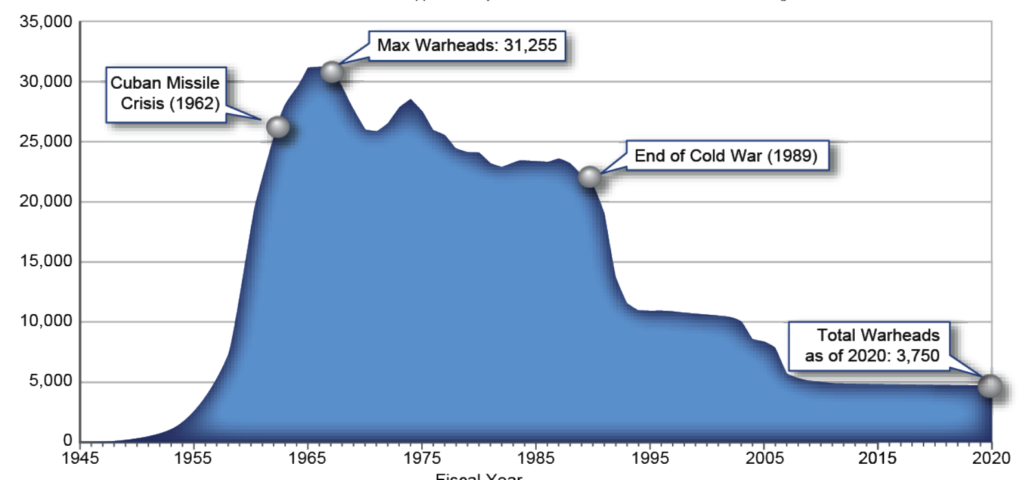

Both the United States and Russia have far more nuclear warheads in their total military stockpiles than what they deploy on their launchers under New START. If the treaty fell away, each side could dramatically and quickly increase the number of nuclear warheads ready to launch on short notice. The US has close to 2,000 strategic warheads in storage, Russia about half that many. Such an increase would be extraordinarily destabilizing and dangerous, especially with a full-scale war raging in Europe and Russia buckling under the strain of unprecedented sanctions.

What the Data Shows

The latest set of data shows that as of March 1, 2022, the United States and Russia both were in compliance with their obligations under the New START treaty not to operate more than 800 total strategic launchers, no more than 700 deployed strategic launchers, and no more than 1,550 warheads attributed to those deployed launchers.

Combined the two countries possessed a total of 1,561 accountable strategic missiles and heavy bombers, of which 1,212 launchers were deployed with 2,989 attributable warheads. That is a slight increase in the number of deployed launchers and warheads compared with six months ago (note: the combined warhead number is actually about 100 too high because each deployed bomber is counted as one weapon even though neither country’s bombers carry weapons under normal circumstances).

Compared with September 2021, the data shows the two countries combined increased the total number of strategic launchers by 19, increased combined deployed strategic launchers by 20, and increased the combined deployed strategic warheads by 142. Of these numbers, only the “19” is real; the other changes reflect natural fluctuations as launchers move in and out of maintenance or are being upgraded.

In terms of the total effect of the treaty, the data shows the two countries since February 2011 combined have cut 428 strategic launchers from their arsenals, reduced deployed strategic launchers by 191, and reduced the number of deployed strategic warheads by 348. However, it is important to remind that this warhead reduction is but a fraction (just over 4 percent) of the estimated 8,185 warheads that remain in the two countries combined nuclear weapons stockpiles (just over 3 percent if counting their total combined inventories of 11,405 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The United States

The data shows the United States possessing 800 strategic launchers, exactly the maximum number allowed by the treaty, of which 686 are deployed with 1,515 warheads attributed to them. This is an increase of 21 deployed strategic launchers and 126 deployed strategic warheads over the past 6 months. The increase is probably partly due to the 13th SSBN – the USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) – having completed its reactor refueling overhaul. The 1,515 deployed warheads is the highest number the United States has deployed since September 2015. The total inventory of strategic launchers has not declined since 2017.

The aggregate data does not reveal how many warheads are attributed to the three legs of the triad. The full unclassified data set will be released later this summer. But if one assumes the number of deployed bombers and deployed ICBMs are the same as in the September 2021 data, then the SSBNs carry 1,068 warheads on roughly 220 deployed Trident II SLBMs. That is an increase of 123 warheads on the SSBN force compared with September, or an average of 4-5 warheads per deployed missile. Overall, this accounts for roughly 70 percent of all the 1,515 warheads attributed to the deployed strategic launchers (nearly 73 percent if excluding the “fake” 45 bomber weapons included in the official count).

The New START data indicates that the United States as of March 1, 2022 deployed approximately 1,068 warheads on ballistic missile onboard its strategic submarines.

Compared with February 2011, the United States has reduced its total inventory of strategic launchers by 324, deployed launchers by 196, and deployed strategic warheads by 285. While important, the warhead reduction represents only a small fraction (about 8 percent) of the estimated 3,708 warheads that remain in the U.S. stockpile (just over 5 percent if counting total inventory of 5,428 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian Federation

The New START data shows Russia with an inventory of 761 strategic launchers, of which 526 are deployed with 1,474 warheads attributed to them. Compared with six months ago, this is a decrease of 1 deployed launcher and an increase of 16 deployed strategic warheads. The change reflects fluctuations caused by launcher maintenance and upgrade work to new systems.

Compared with February 2011, Russia has cut its total inventory of strategic launchers by 104, increased deployed launchers by 5, and decreased deployed strategic warheads by 63. This modest warhead reduction represents less than 2 percent of the estimated 4,477 warheads that remain in Russia’s nuclear weapons stockpile (roughly 1 percent if counting the total inventory of 5,977 stockpiled and retired (but yet to be dismantled) warheads).

The Russian New START reductions since 2011 are smaller than the US reductions because Russia had fewer strategic forces than the United States when the treaty entered into force.

That disparity remains today. Despite frequent claims by hardliners that Russia is ahead of the United States, the New START data shows that Russia has 160 deployed strategic launchers fewer than the United States, a significant gap that exceeds the number of missiles in an entire US Air Force ICBM wing. Despite its nuclear modernization program, Russia has so far not sought to reduce this gap by deploying more strategic launchers. Instead, the Russian launcher deficit has been increasing by about one-third since its lowest point in February 2018.

Instead of closing the launcher gap, the Russian military appears to try to compensate by increasing the number of warheads that can be carried on the newer missiles (SS-27 Mod 2, Yars, and SS-N-32, Bulava) that are replacing older types (SS-25, Topol, SS-N-18, Vysota, and SS-N-23, Sineva). Thanks to the New START treaty limit, many of these warheads are not deployed on the missiles under normal circumstance but are stored and could potentially be uploaded onto the launchers in a crisis. The United States also has such an upload capability for its larger inventory of launchers and therefore is not at a strategic disadvantage.

Two of Russia’s new strategic nuclear weapons (SS-19 Mod 4, Avangard, and SS-29, Sarmat) are covered by New START if formally incorporated. Other types (the Poseidon nuclear-powered torpedo, and the Burevestnik nuclear-powered ground-launched cruise missile) are not yet deployed and appear to be planned in relatively small numbers. They do not appear capable of upsetting the strategic balance in the foreseeable future. The treaty includes provisions for including new weapon types, if the two sides agree.

The sanctions in reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely slow Russia’s nuclear modernization in the next decade.

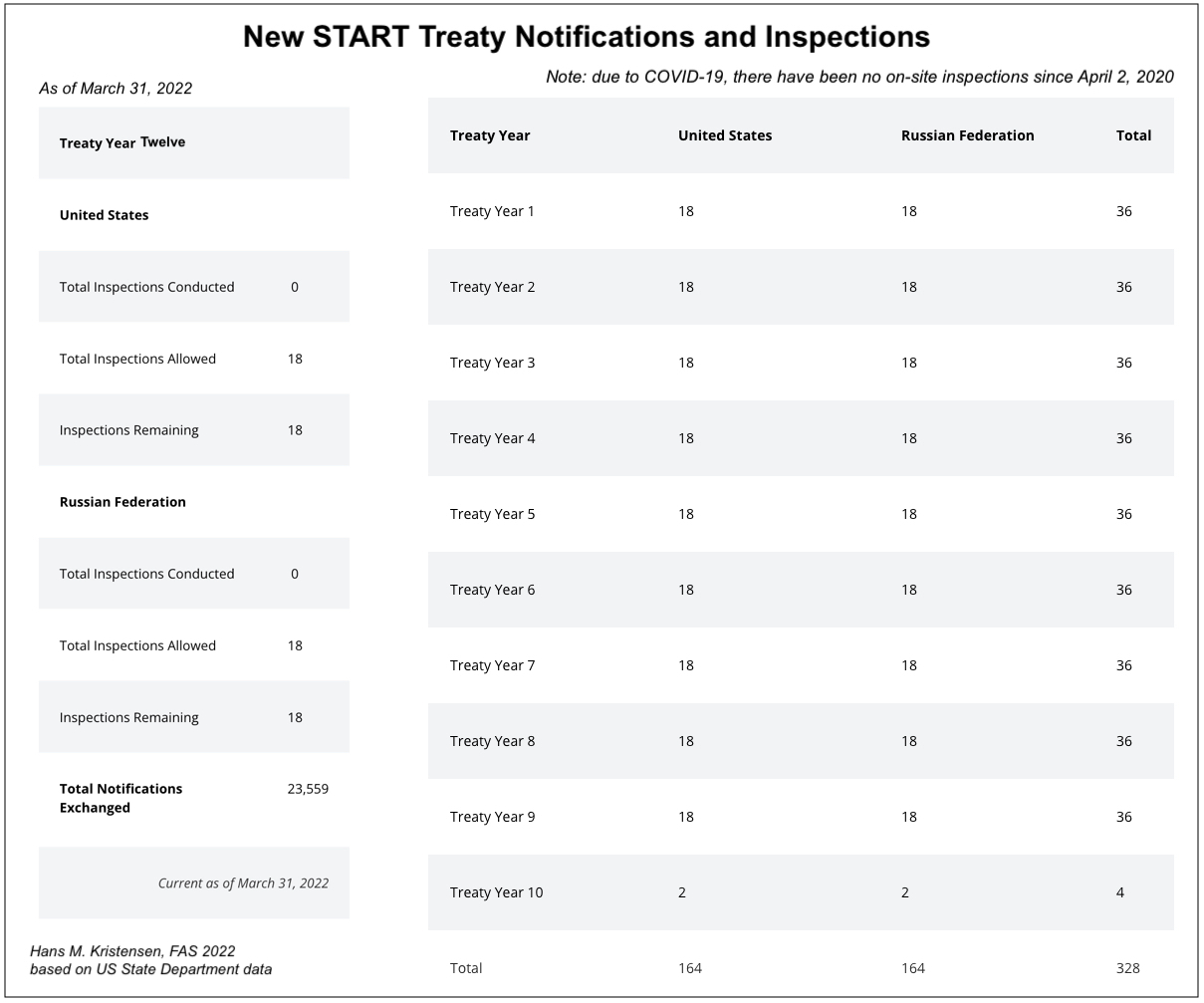

Inspections and Notifications

In addition to the aggregate data described above, the New START treaty also allows for up to 18 on-site inspections per year and notifications of launcher movements and activities. Up until April 2020, a total of 328 on-site inspections were conducted. Because of COVID-19, there have been no inspections since. The two countries have continued to exchange large numbers of notifications: a total of 23,559 as of March 31, 2022.

Looking Ahead

The continued complaince by the United States and Russia to the New START treaty and its data exchanges are extraordinary given the demise of treaties, agreements, and deep animosity and almost complete loss of trust. The treaty’s interactions between the two countries and the caps and predictability it provides on strategic offensive nuclear forces have never been more important since New START was negotiated more than a decade ago.

But the clock is running out. Although New START was extended in February 2021 for an additional five years, the treaty will expire in February 2026. Strategic stability talks between Russia and the United States have been disrupted by the war in Ukraine and seem unlikely to resume in the foreseeable future.

If New START is not followed by a new treaty by the time it expires in 2026, there will no limits on US and Russian nuclear forces for the first time the 1970s.

Moreover, political polarization makes it highly uncertain if the US Congress would approve a new treaty.

Short of a formal treaty, the two sides potentially could make an executive agreement and pledge to continue to abide by the New START limits even after the treaty officially expires.

The silver lining is that both countries have a strong interest in continuing to maintain limits on the other side’s strategic offensive nuclear forces. That is why it is important that hardliners are not allowed to misuse Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s nuclear buildup to undermine New START and increase nuclear forces.

Additional information:

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

- Russian nuclear forces, 2022

- United States nuclear forces, 2021 [2022 version forthcoming]

This publication was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Flying Under The Radar: A Missile Accident in South Asia

A crashed Indian missile inside Pakistani territory. Image: Pakistan Air Force.

With all eyes turned towards Ukraine these past weeks, it was easy to miss what was almost certainly a historical first: a nuclear-armed state accidentally launching a missile at another nuclear-armed state.*

On the evening of March 9th, during what India subsequently called “routine maintenance and inspection,” a missile was accidentally launched into the territory of Pakistan and impacted near the town of Mian Channu, slightly more than 100 kilometers west of the India-Pakistan border.

Because much of the world’s attention has understandably been focused on Eastern Europe, this story is not getting the attention that it deserves. However, it warrants very serious scrutiny––not only due to the bizarre nature of the accident itself, but also because both India’s and Pakistan’s reactions to the incident reveal that crisis stability between South Asia’s two nuclear rivals may be much less stable than previously believed.

The Incident

Using official statements and open-source clues, it is possible to piece together a relatively complete picture of what took place on the evening of March 9th.

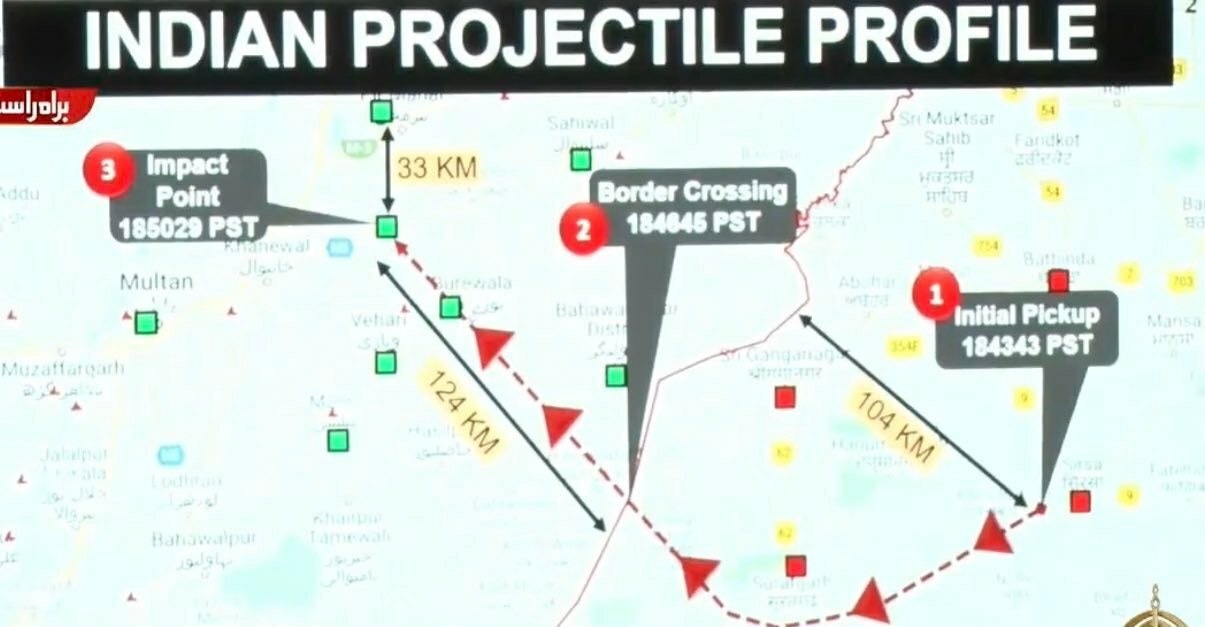

At 18:43:43 Pakistan Standard Time (19:13:43 India Standard Time), the Pakistan Air Force picked up a “high-speed flying object” 104 kilometers inside Indian territory, near Sirsa, in the state of Haryana. According Air Vice Marshal Tariq Zia––the Director General Public Relations for the Pakistan Air Force––the object traveled in a southwesterly direction at a speed between Mach 2.5 and Mach 3. After traveling between 70 and 80 kilometers, the object turned northwest and crossed the India-Pakistan border at 18:46:45 PKT. The object then continued on the same northwesterly trajectory until it crashed near the Pakistani town of Mian Channu at 18:50:29 PKT.

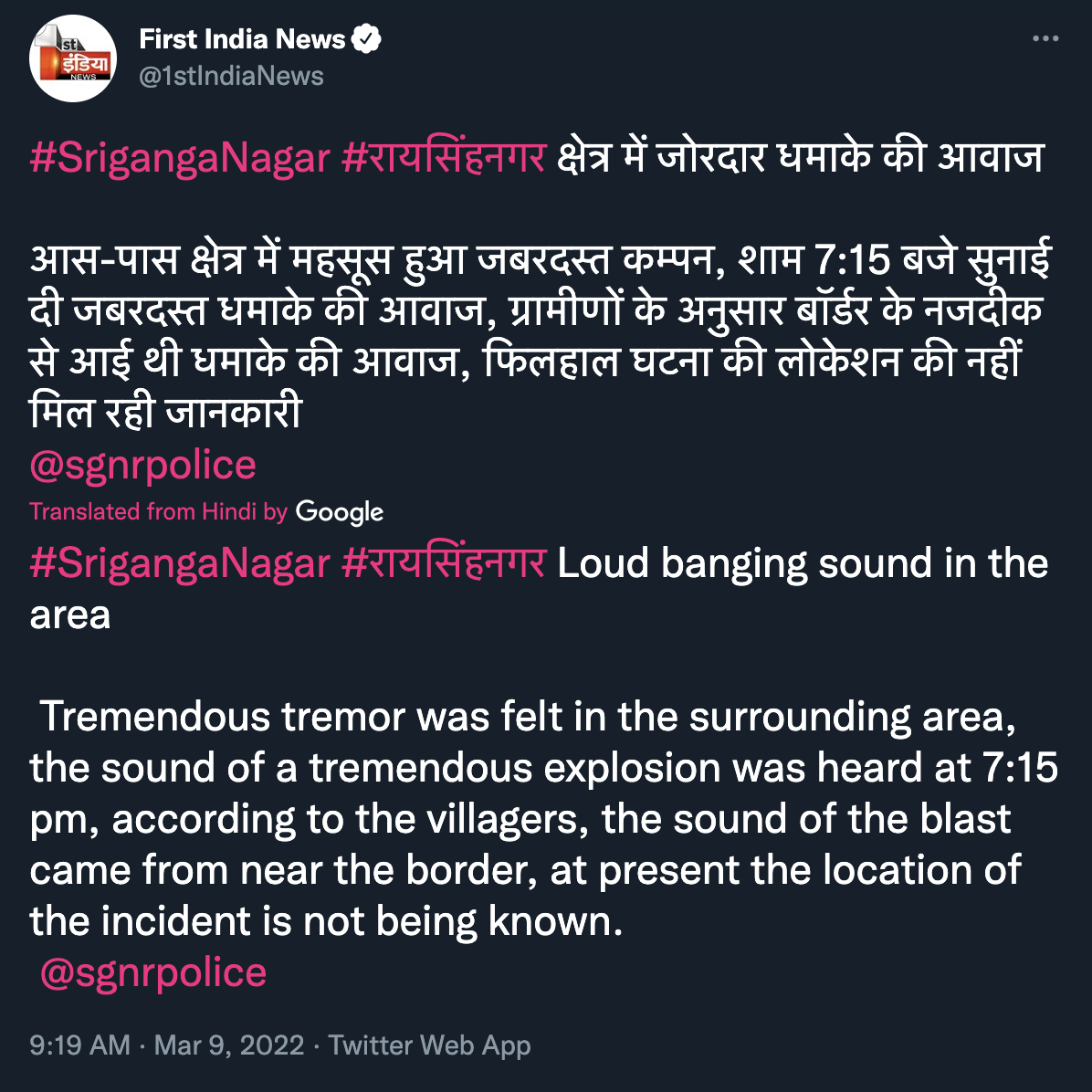

Tweet from @1stIndiaNews indicating that a “tremendous explosion” was heard at approximately 19:15 IST at the city of Sri Ganganagar near the India-Pakistan border. This time and location adds a data point to interpreting the flight path of the missile.

According to Pakistani military officials in a March 10th press conference, 3 minutes and 46 seconds of the object’s total flight time of 6 minutes and 46 seconds were within Pakistani airspace, and the total distance traveled inside of Pakistan was 124 kilometers.

Annotated map of the missile’s flight path provided by Pakistani military officials to media on 10 March 2022.

In a press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that the object was “certainly unarmed” and that no one was injured, although noted that it damaged “civilian property.”

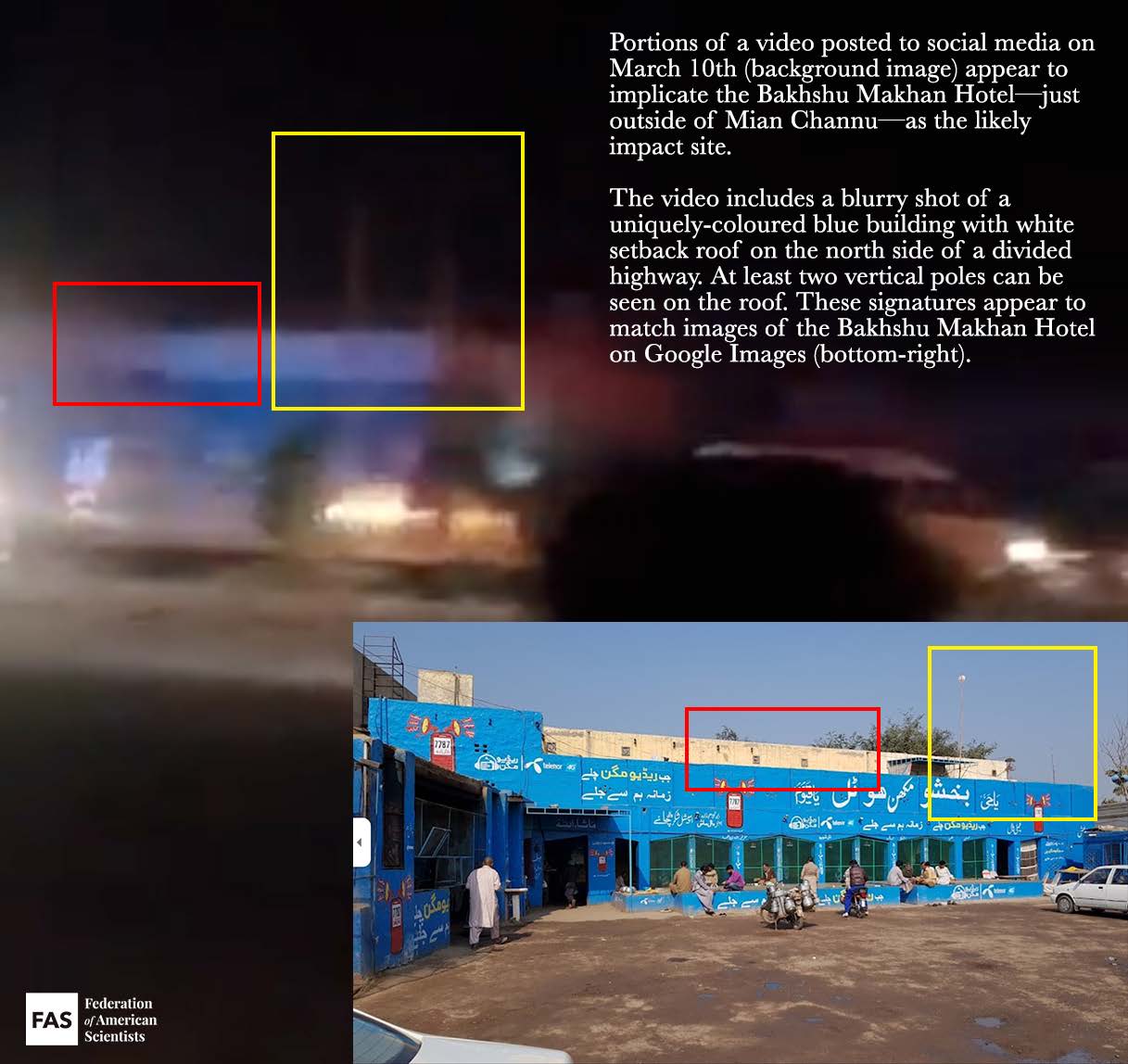

Although the crash site has not been confirmed and official photos include very few useful visual signatures, observation of local civilian social media activity indicates that a likely candidate is the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel, just outside of Mian Channu (30°27’6.40″N, 72°24’10.87″E). One video of the crash site posted to Twitter includes a shot of a uniquely-colored blue building with a white setback roof on the other side of a divided highway. At least two vertical poles can be seen on the roof of the building. All of these signatures appear to match those included in images of the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel in Google Images.

The video’s caption suggests that the object that crashed was an “army aviation aircraft drone;” however, Pakistani military officials subsequently reported that the object was an Indian missile. Neither Pakistan nor India has publicly confirmed what type of missile it was; however, in a March 10th press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that “we can so far deduce that it was a supersonic missile––an unknown missile––and it was launched from the ground, so it was a surface-to-surface missile.”

This statement, in addition to photos of the debris and other official details relating to range, speed, altitude, and flight time of the object, suggest that it was very likely a BrahMos cruise missile.

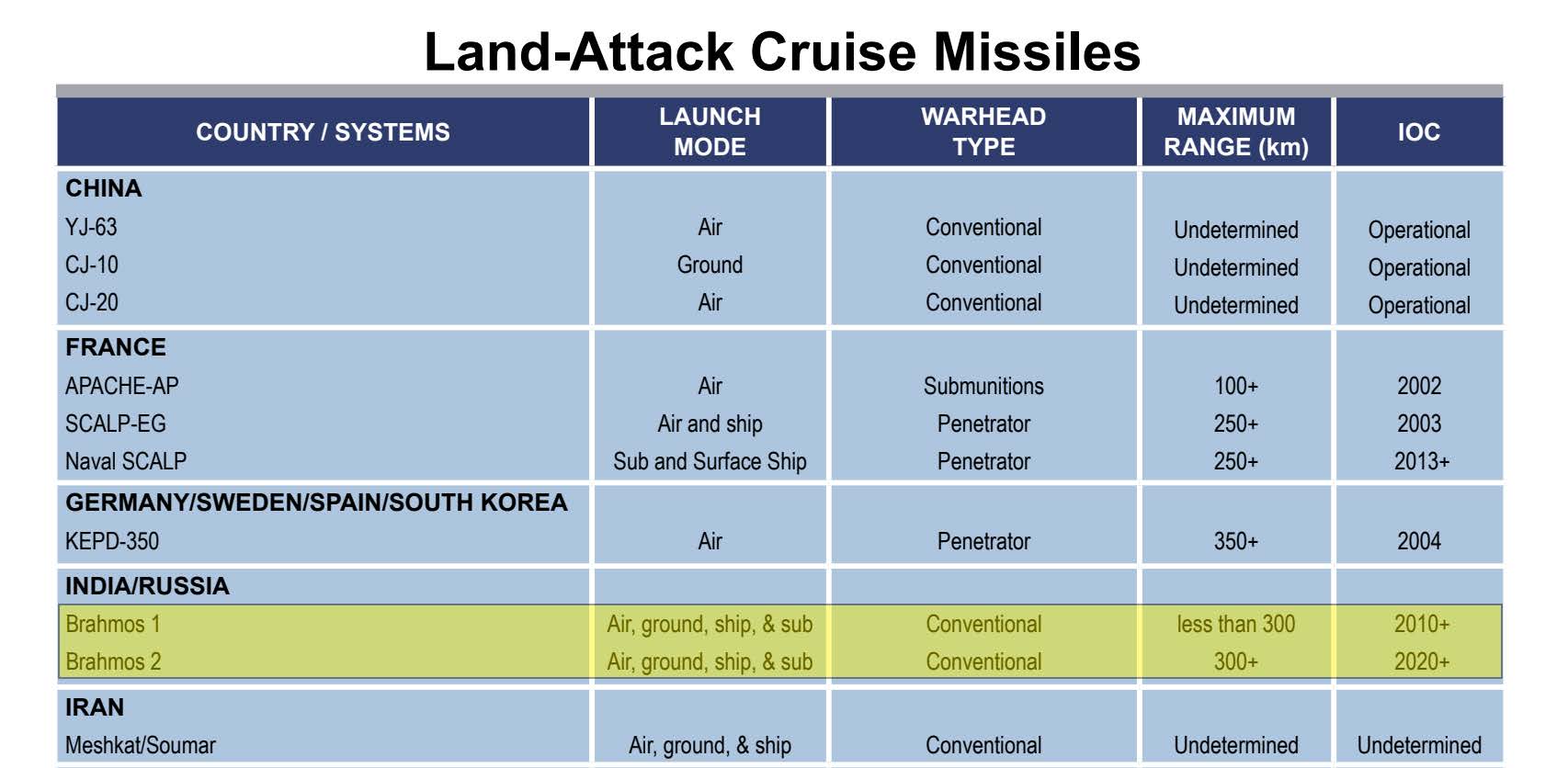

BrahMos is a ramjet-powered, supersonic cruise missile co-developed with Russia, that can be launched from land, sea, and air platforms and can travel at a speed of approximately March 2.8. The US National Air and Space Intelligence Centre (NASIC) suggested that an earlier version of BrahMos had a range of “less than 300” kilometers, but the Indian Ministry of Defence recently announced on 20 January 2022 that it had extended the BrahMos’ range, with defence sources saying that the missile could now travel over 500 kilometres. The reported speed of the “high-speed flying object,” as well as the distance traveled, matches the publicly-known capabilities of the BrahMos cruise missile.

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s 2017 Ballistic and Cruise Missile report lists two versions of the BrahMos missile as “conventional.”

Although many Indian media outlets often describe the BrahMos as a nuclear or dual-capable system, NASIC lists it as “conventional,” and there is no public evidence to indicate that the missile can carry nuclear weapons.

India has launched a Court of Inquiry to determine how the incident occurred; however, the Indian government has otherwise remained tight-lipped on details. In the absence of official statements, small snippets have trickled out through Indian and Pakistani media sources––prompting several questions that still need answers.

How did the missile get “accidentally” launched?

According to the Times of India, an audit was being conducted by the Indian Air Force’s Directorate of Air Staff Inspection at the time of the launch. As part of that audit, or possibly as part of a separate exercise, it appears that target coordinates––including mid-flight waypoints––were fed into the missile’s guidance system. According to Indian defence sources, in order to launch the BrahMos, the missile’s mechanical and software safety locks would also have had to be bypassed and the launch codes would have had to be entered into the system.

The BrahMos does not appear to have a self-destruct mechanism. As a result, once the missile was launched, there was no way to abort.

Given that defence sources indicate that the missile “was certainly not meant to be launched,” it still remains unclear whether the launch was due to human or technical error. On March 11th, in its first public statement about the incident, the Indian government stated that “a technical malfunction led to the accidental firing of a missile.” However, since the formal convening of a Court of Inquiry, the government has since changed its rhetoric, with Indian officials stating that “the accidental firing took place because of human error. That’s what has emerged at this stage of the inquiry. There were possible lapses on the part of a Group Captain and a few others.” Tribute India reports that there are currently four individuals under investigation.

While this is certainly a plausible explanation for the incident, it is also worth noting that the Indian government would be financially incentivized to emphasize the human error narrative over a technical malfunction narrative. On January 28th, India concluded a $374.96 million deal with the Philippines to export the BrahMos––a deal which amounts to the country’s largest defence export contract. Additional BrahMos exports will be crucial for India to meet its ambitious defence export targets by 2025, and the negative publicity associated with a possible BrahMos technical malfunction could significantly hinder that goal.

Did Pakistan track the missile correctly?

In a press conference on March 10th, Pakistani military officials noted that Pakistan’s “actions, response, everything…it was perfect. We detected it on time, and we took care of it.” However, Indian military officials have publicly disputed Pakistan’s interpretation of the missile’s flight path. Pakistan announced on March 10th that the missile was picked up near Sirsa; however, Indian officials subsequently stated that the missile was launched from a location near Ambala Air Force Station, nearly 175 kilometers away. India’s explanation is likely to be more accurate, given that there is no known BrahMos base near Sirsa, but there is one near Ambala (h/t @tinfoil_globe). Indian defence sources have also suggested that the map of the missile’s perceived trajectory that the Pakistani military released on March 10th was incorrect.

Annotated Google Earth image showing the 175 kilometer distance between the likely launch site and Pakistan’s radar pickup.

Furthermore, Pakistani officials announced on March 10th that the missile’s original destination was likely to be the Mahajan Field Firing Range in Rajasthan, before it suddenly turned and headed northwest into Pakistan. However, Indian defence sources have since suggested that the missile was not actually headed for the Mahajan Field Firing Range, but instead was “follow[ing] the trajectory that it would have in case of a conflict, but ‘certain factors’ played a role in ensuring that any pre-fed target was out of danger.” Given that the impact site was not near any critical military or political infrastructure, this could suggest that the cruise missile had its wartime mid-flight trajectory waypoints pre-loaded into the system, but its actual target had not yet been selected. If this is the case, then this targeting practice would be similar in nature to how some other nuclear-armed states target their missiles at the open ocean during peacetime––precisely in case of incidents like this one. Although the missile still landed on Pakistani territory, the fact that it did not hit any critical targets prevented the crisis from escalating. It is worth noting, however, that this would certainly not be the case if the missile had actually injured or killed anyone.

During the March 10th press conference, Pakistani officials noted that the Pakistan Air Force did not attempt to shoot down the missile because “the measures in place in times of war or in times of escalation are different [from those] in peace time.” However, India’s challenges to Pakistan’s narrative also raise significant questions about whether the Pakistan Air Force was able to accurately track the missile correctly. If not, then this raises the possibility of miscalculation or miscommunication, and crisis stability would be seriously eroded if a similar situation occurred during a time of heightened tensions.

Were any civilian aircraft put in danger?

In its public statements, Pakistan has emphasized that the accidental missile launch could have put civilian flights in danger, as India did not issue a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) prior to launch. Governments typically issue NOTAMs in conjunction with missile tests, in order to inform civilian aircraft to avoid a particular patch of airspace during the launch window. Given that India did not issue one, a time-lapse video prepared by Flightradar24 showed that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch. The video erroneously suggests that the missile traveled in a straight line from Ambala to Mian Channu, when it appears to have dog-legged in mid-flight; however, the video is still a useful resource to demonstrate how crowded the skies were at the time of the accident.

A screenshot of a video prepared by Flightradar24, showing that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch.

Why was India’s response so poor?

Given the seriousness of the incident, India’s delayed response has been particularly striking. Immediately following the accidental launch, India could have alerted Pakistan using its high-level military hotlines; however, Pakistani officials stated that it did not do so. Additionally, India waited two days after the incident before issuing a short public statement.

India’s poor response to this unprecedented incident has serious implications for crisis stability between the two countries. According to DNA India, in the absence of clarification from India, Pakistan Air Force’s Air Defence Operations Centre immediately suspended all military and civilian aircraft for nearly six hours, and reportedly placed frontline bases and strike aircraft on high alert. Defence sources stated that these bases remained on alert until 13:00 PKT on March 14th. Pakistani officials appeared to confirm this, noting that “whatever procedures were to start, whatever tactical actions had to be taken, they were taken.”

We were very, very lucky

Thankfully, this incident took place during a period of relative peacetime between the two nuclear-armed countries. However, in recent years India and Pakistan have openly engaged in conventional warfare in the context of border skirmishes. In one instance, Pakistani military officials even activated the National Command Authority––the mechanism that directs the country’s nuclear arsenal––as a signal to India. At the time, the spokesperson of the Pakistan Armed Forces not-so-subtly told the media, “I hope you know what the NCA means and what it constitutes.”

If this same accidental launch had taken place during the 2019 Balakot crisis, or a similar incident, India’s actions were woefully deficient and could have propelled the crisis into a very dangerous phase.

Furthermore, as we have written previously, in recent years India’s rocket forces have increasingly worked to “canisterize” their missiles by storing them inside sealed, climate-controlled tubes. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis.

This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

India’s recent missile accident––and the deficient political and military responses from both parties––suggests that regional crisis instability is less stable than previously assumed. To that end, this crisis should provide an opportunity for both India and Pakistan to collaboratively review their communications procedures, in order to ensure that any future accidents prompt diplomatic responses, rather than military ones.

Background Information:

- “Indian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August 2020.

- “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept/Oct 2021.

- “India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, Dec 2021.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This article was made possible with generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

*[Note: This type of missile accident has apparently happened before; on 11 September 1986, a Soviet missile flew more than 1,500 off-course and landed in China. Thank you to the excellent Stephen Schwartz for the historical reference.]

Categories: Arms Control, ballistic missiles, Deterrence, Disarmament, India, Nuclear Weapons, Pakistan

India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward

On 18 December 2021, India tested its new Agni-P medium-range ballistic missile from its Integrated Test Range on Abdul Kalam Island. This was the second test of the missile, the first test having been conducted in June 2021.

Our friends at Planet Labs PBC managed to capture an image of the Agni-P launcher sitting on the launch pad the day before the test took place.

Following both launches of the Agni-P, the Indian Government referred to the missile as a “new generation” nuclear-capable ballistic missile. Back in 2016, when the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) first announced the development of the Agni-P (which was called the Agni-1P at the time), a senior DRDO official explained why this missile was so special:

“As our ballistic missiles grew in range, our technology grew in sophistication. Now the early, short-range missiles, which incorporate older technologies, will be replaced by missiles with more advanced technologies. Call it backward integration of technology.”

The Agni-P is India’s first shorter-range missile to incorporate technologies now found in the newer Agni-IV and -V ballistic missiles, including more advanced rocket motors, propellants, avionics, and navigation systems.

Most notably, the Agni-P also incorporates a new feature seen on India’s new Agni-V intermediate-range ballistic missiles that has the potential to impact strategic stability: canisterization. And the launcher used in the Agni-P launch appears to have increased mobility. There are also unconfirmed rumors that the Agni-P and Agni-V might have the capability to launch multiple warheads.

Canisterization

“Canisterizing” refers to storing missiles inside a sealed, climate-controlled tube to protect them from the outside elements during transportation. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis. This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

If Indian warheads are increasingly mated to their delivery systems, then it would be harder for an adversary to detect when a crisis is about to rise to the nuclear threshold. With separated warheads and delivery systems, the signals involved with mating the two would be more visible in a crisis, and the process itself would take longer. But widespread canisterization with fully armed missiles would shorten warning time. This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

For years, it was evident that India’s new Agni-V intermediate-range missile (the Indian Ministry of Defense says Agni-V has a range of up to 5,000 kilometers; the US military says the range is over 5,000 kilometers but not ICBM range) would be canisterized; however, the introduction of the shorter-range, canisterized Agni-P suggests that India ultimately intends to incorporate canisterization technology across its suite of land-based nuclear delivery systems, encompassing both shorter- and longer-range missiles. While Agni-V is a new addition to India’s arsenal, Arni-P might be intended––once it becomes operational––to replace India’s older Agni-I and Agni-II systems.

MIRV technology

It appears that India is also developing technology to potentially deploy multiple warheads on each missile. There is still uncertainty about how advanced this technology is and whether it would enable independent targeting of each warhead (using multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles, or MIRVs) or simply multiple payloads against the same target.

The Agni-P test in June 2021 was rumored to have used two maneuverable decoys to simulate a MIRVed payload, with unnamed Indian defense sources suggesting that a functional MIRV capability will take another two years to develop and flight-test. The Indian MOD press release did not mention payloads. It is unclear whether the December 2021 test utilized decoys in a similar manner.

In 2013, the director-general of DRDO noted in an interview that “Our design activity on the development and production of MIRV is at an advanced stage today. We are designing the MIRVs, we are integrating [them] with Agni IV and Agni V missiles.” In October 2021, the Indian Strategic Forces Command conducted its first user trial of the Agni-V in full operational configuration, which was rumored to have tested MIRV technology. The MOD press release did not mention MIRVs.

If India succeeds in developing an operational MIRV capability for its ballistic missiles, it would be able to strike more targets with fewer missiles, thus potentially exacerbating crisis instability with Pakistan. If either country believed that India could potentially conduct a decapitating or significant first strike against Pakistan, a serious crisis could potentially go nuclear with little advance warning. Indian missiles with MIRVs would become more important targets for an adversary to destroy before they could be launched to reduce the damage India could inflict. Additionally, India’s MIRVs might prompt Indian decision-makers to try and preemptively disarm Pakistan in a crisis.