Belarus’ “Nuclear-Capable” Iskanders Get A New Garage

A Maxar satellite image appears to show Iskander missile launchers outside new garage at Belarusian base

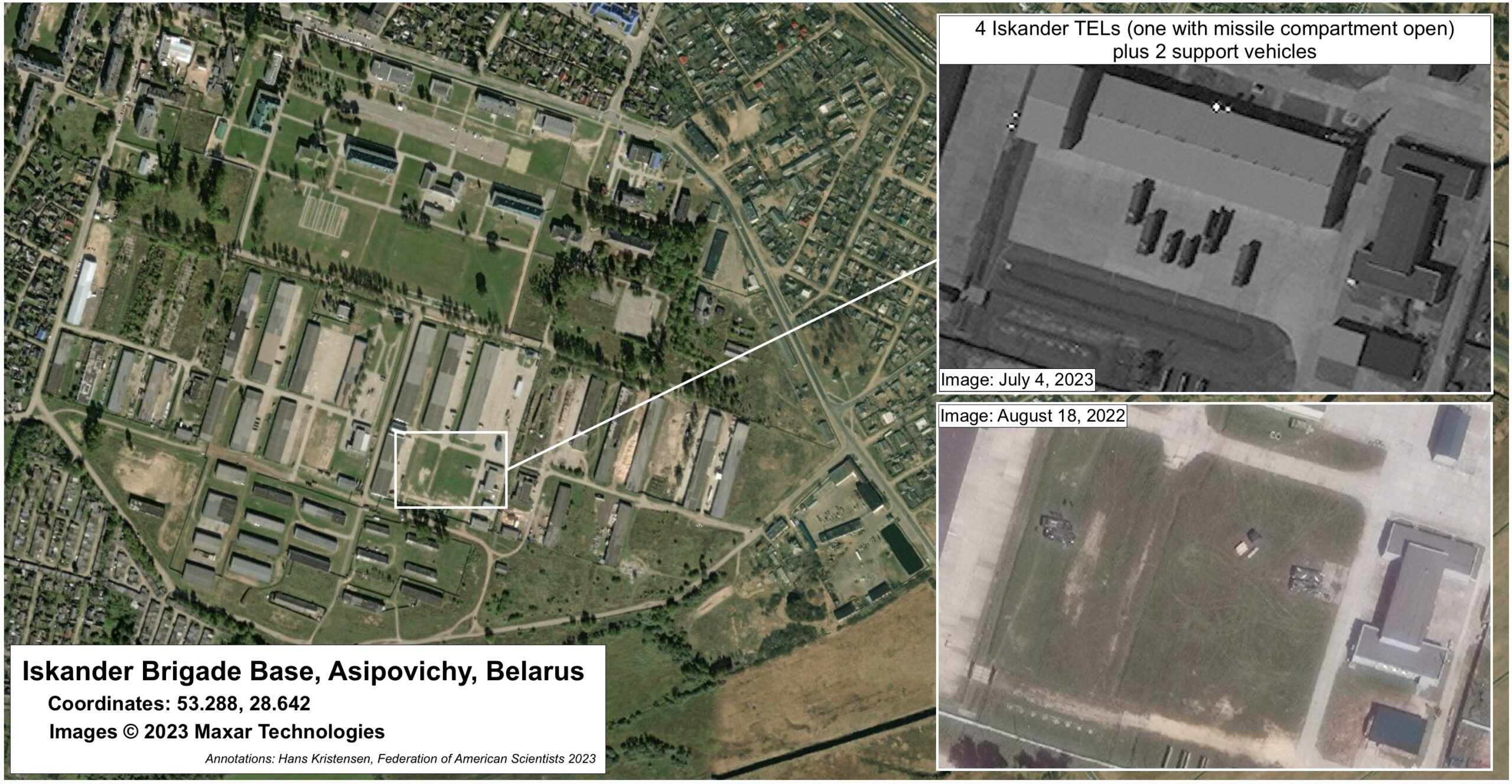

The Belarusian military has completed what appears to be a new garage facility for the allegedly nuclear-capable Iskander missile launchers it received from Russia.

The new facility was added to an existing base in Asipovichy in central Belarus (53.288, 28.642), which is home to the 465th Missile Brigade. Satellite images indicate construction began in October 2022 and was completed in April 2023.

A Maxar satellite image taken on July 4, 2023, shows what appears to show four 13-meter Iskander launchers (and/or transporters) and two smaller support vehicles outside the garage. The missile storage compartment on one of the launchers is open.

Between October 2022 and April 2023, a new Iskander garage was constructed at a Belarusian military base in Asipovichy

The new facility is located only seven kilometers (4.4 miles) from the training ground (53.296, 28.536) where the Iskander launchers were first geolocated, and only 12 kilometers (7.3 miles) from a weapons depot (53.317, 28.813) that might be undergoing a potential upgrade to a temporary nuclear warhead storage facility.

Russian Iskander missile launchers supplied to Belarus allegedly are capable of firing Russian nuclear warheads

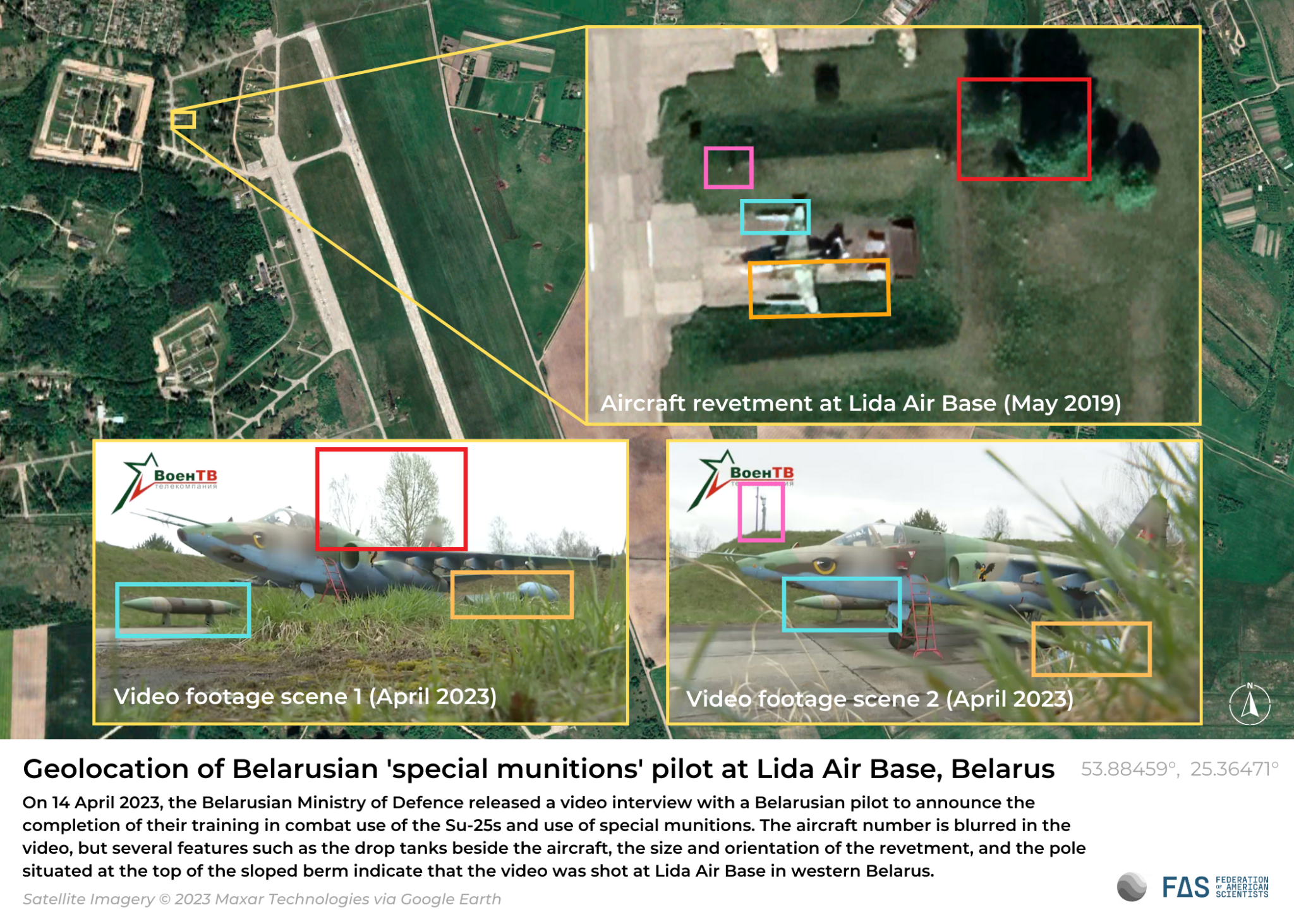

Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko and Russian President Vladimir Putin have repeatedly described plans to equip Belarusian Iskander launchers with the capability to fire Russian nuclear-tipped missiles and to build a nuclear storage facility in Belarus. They also said Russia would upgrade some Belarusian military jets (potentially Su-24 or Su-25) to deliver nuclear bombs.

If so, this would be the first time since the Cold War that Russia is equipping another country to launch its nuclear weapons and undercut Russian criticism of U.S. nuclear sharing arrangements with NATO allies.

So far there has been no clear visual confirmation of these plans, and public Western intelligence reports have not confirmed that Russia has actually deployed nuclear warheads in Belarus. Russia is thought to keep its non-strategic nuclear warheads in central storage facilities in Russia.

Additional information:

• Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans In Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?

• Video Indicates That Lida Air Base Might Get Russian “Nuclear Sharing” Mission In Belarus

• Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Oppenheimer, FAS, and Today’s Nuclear Weapons Risks

They won’t fear it unless they understand it. And they won’t understand it until we use it

– Cillian Murphy, depicting J. Robert Oppenheimer, in Oppenheimer, opening in theaters tomorrow.

The anticipated summer blockbuster is already abuzz with its portrayal of history, politics, ethics, and science; for good measure, it’s said to have “earned that R rating” for the undisclosed “complicated” sexual appetites of the main characters, too.

What may truly stun audiences, though, is the realization of what has and hasn’t changed when it comes to nuclear weapons risks – especially now.

Oppenheimer and FAS

Audiences will be interested to learn of Oppenheimer’s connection to the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). His work actually created FAS in 1945. Initially called the Federation of Atomic Scientists, a group of scientists directly involved with the Manhattan Project formed FAS in response to the urgent need to combat nuclear arms racing by promoting public engagement, reducing nuclear risks, and establishing an international system for nuclear control and cooperation. This is a mission we continue today.

FAS has come to Oppenheimer’s defense not once, but twice. First, in 1954, by joining forces with Albert Einstein and scientists from Princeton to defend Oppenheimer’s loyalty and patriotic devotion to the United States when the government revoked his security clearance, stripping him of his stature and ability to serve in high levels of the government. Second, in 2022, FAS submitted a formal letter of support when the government retroactively and posthumously restored Oppenheimer’s reputation.

FAS continues to be a leader in promoting nuclear arms control, nonproliferation, and disarmament through our Nuclear Information Project. By providing the most accurate information about nuclear weapons and trends to policymakers, activists, academics, journalists, and the public, we strive to create the conditions for a more just, equitable, and peaceful world. We also recognize the importance of training and empowering the next generation of nuclear arms controllers and policy experts. To that end, FAS is currently fostering new perspectives via our New Voices in Nuclear Weapons fellowship. Still, more work is needed.

I spoke with Eliana Johns, Research Associate with the Nuclear Information Project at FAS, about how Oppenheimer’s story connects with contemporary issues and current risks, and how FAS continues to advocate for a safer world.

Katie: What would you say to someone who sees Oppenheimer and comes away from it with a new sense of awe, and perhaps dread, about nuclear capabilities? Audiences may be profoundly upset to realize nuclear weapons are still a threat. What are some misconceptions people may have about threat levels today?

Eliana: I think Oppenheimer will definitely be a lot for everyone to process. The film may even be the first moment that people (especially from my generation) realize the destructive capability of nuclear weapons and that the threat of nuclear use is still very real today. There are plenty of misconceptions about the technical aspects, the purpose, and the costs associated with nuclear weapons programs. For instance, we all know about the devastating bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, but some may not know that modern nuclear warheads and delivery systems are exponentially more powerful and accurate. However, I think the biggest misconception is that nuclear weapons don’t cause any harm unless used in war.

I think the biggest misconception is that nuclear weapons don’t cause any harm unless used in war.

Katie: What are some issues the film will likely misunderstand, gloss over, or even avoid?

Unfortunately, the film will likely leave out a huge part of the story of the Manhattan Project: impacted communities. From predominantly Navajo uranium miners in Colorado and Congolese miners in the Belgian Congo to downwinders and victims of nuclear testing in the southwestern United States, Kazakhstan, the Marshall Islands, and Algeria to the Hibakusha in Japan – nuclear weapons have already taken a toll on countless communities around the world. Not only is the threat of further nuclear weapons use very real today, but many other consequences have already resulted from their invention, testing, and use.

Additionally, nuclear weapons programs are expensive, which means that countries like the United States end up spending billions of dollars each year on maintaining and modernizing their nuclear arsenals, while countries like North Korea resort to hacking, laundering, exploitation, and other illegal activities to fund their nuclear weapons and missile programs. The cumulative costs are tremendous and put a huge burden on the public.

Although it can be hard and confusing, having conversations about nuclear weapons is important because we cannot ignore the problem. We should feel some level of dread and anger because nuclear weapons are dangerous and have already had significant and terrible impacts on many people’s lives. In a time when nuclear weapons are being referenced more and more in the news, social media, and politics, I hope seeing Oppenheimer will inspire people to become more informed and engaged on these issues.

Katie: What is being done today to mitigate nuclear risks, and what is the role of FAS in this work?

Eliana: There are a variety of ways that people work to mitigate the risk of nuclear weapons use and seek justice for those impacted by nuclear testing and uranium mining. From academics to government officials, people are working toward arms control and non-proliferation goals to prevent the increase and spread of nuclear weapons. Also, several organizations (such as the Tularosa Basin Downwinder Consortium) advocate for downwinder communities, seek financial and environmental reconciliation, and tell their stories.

A crucial aspect of this work is transparency. When governments are opaque about how many weapons they have and the situations in which they might use them, this causes arms racing and worst-case thinking between nations that are in blind competition with one another. And when governments are not transparent with their citizens about nuclear-related accidents, exposure, or spending on weapons systems, people suffer the consequences.

Because of this key element of transparency, our work at FAS is extremely important. FAS’ Nuclear Information Project develops estimates of global nuclear weapons stockpiles in order to inform conversations around arms control and risk reduction in both the public and private sectors. Our goal is to engage the public and policymakers in educated discussions about topics such as nuclear weapons spending, non-proliferation, and the intersectionality between nuclear weapons and other security threats like climate change. This work continues the long-lasting legacy of promoting transparency and accountability in the nuclear weapons space, which is vital for progress in reducing the risks of nuclear weapons.

FAS also recently started a summer program for aspiring nuclear weapons experts called the New Voices on Nuclear Weapons Fellowship. This program is designed to address the high barriers to entry into the nuclear field by providing young nuclear scholars with support, mentorship, and opportunity for publication. Programs such as this help bring up the next generation of experts who carry with them a diverse range of experiences and perspectives that inform creative ideas for the future of arms control and non-proliferation.

Katie: What should the general public do to learn more, stay informed, and join the effort to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons?

Eliana: FAS is a great place to stay updated on what is happening in the world with regard to nuclear weapons. The Nuclear Information Project team publishes detailed accounts of the current status of nuclear weapons arsenals as well as shorter, factual articles that explain important events or discoveries.

Many other organizations in the nuclear policy field are also working to inform and engage people on these issues and offer a variety of resources that can be easily shared with friends, coworkers, and family members; many also provide information on how to engage with your representatives. For example, The Friends Committee on National Legislation helps you contact your members of Congress about issues like extending the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provides monetary benefits to onsite participants of nuclear testing and downwinders but is set to expire in 2024.

After watching Oppenheimer (in IMAX 70mm, of course), I hope folks will be inspired to learn more about the nuclear field and use these resources to take part in the effort to stigmatize nuclear weapons and seek justice for impacted communities.

Katie: Well said! Thank you for your time, Eliana.

Nuclear Notebook: French Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column reviews the status of France’s nuclear arsenal and finds that the stockpile of approximately 290 warheads has remained stable in recent years. However, significant modernizations regarding ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, submarines, aircraft, and the nuclear industrial complex are underway.

Read the full “French Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

Does Russia Have Nuclear Landmines?

Photos of Russian nuclear “backpacks” or landmines are hard to come by. For illustrative purposes, this is an image of a U.S. Special Atomic Demolition Munition (SADM) in its bag (since retired). The U.S. military possessed nuclear demolition weapons until the 1980s.

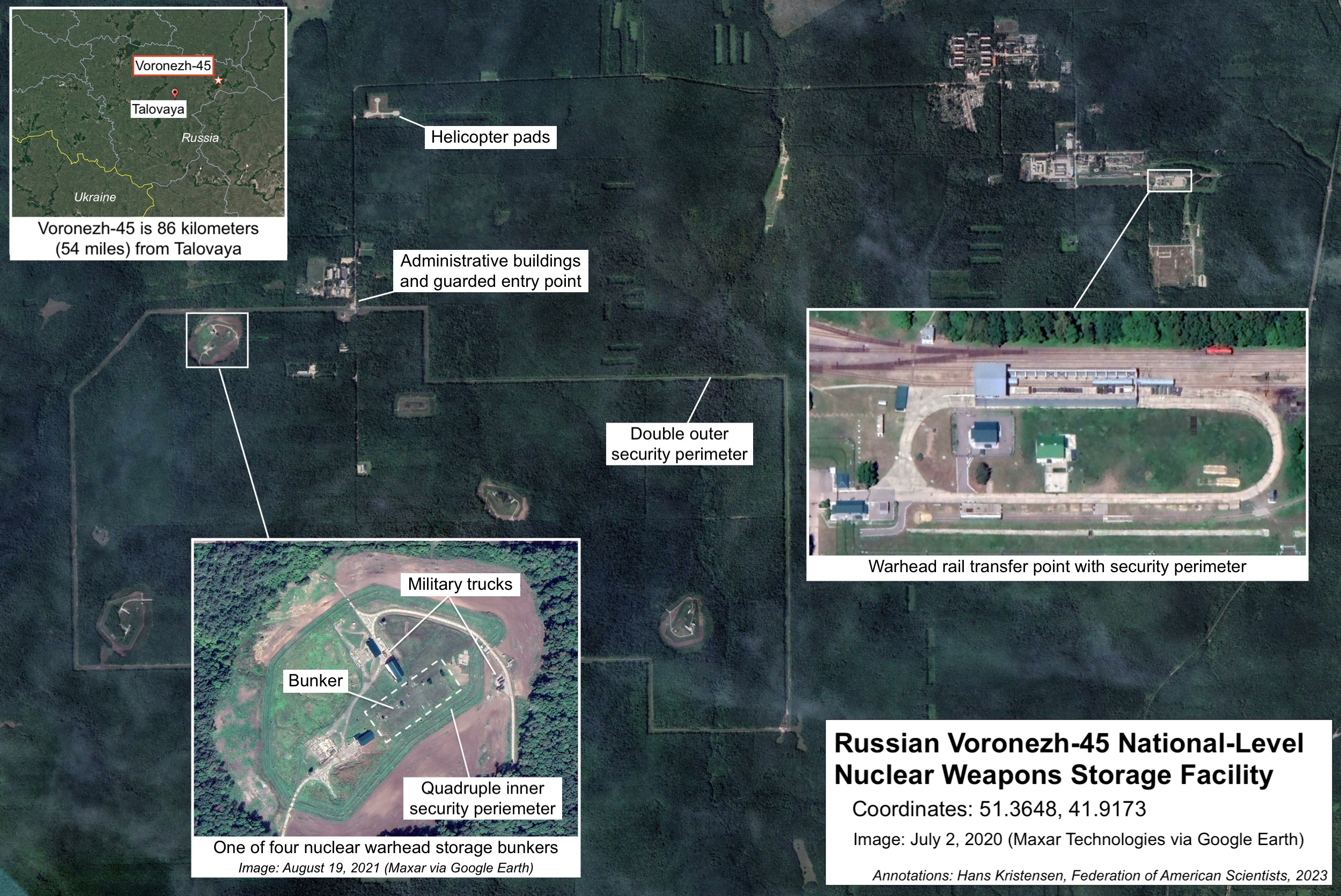

Last week, Reuters published a report that said the Wagner group rebellion that sent armed forces hundreds of miles across Russia got near a nuclear weapons storage site: Voronezh-45.

Kyrylo Budanov, the head of Ukraine’s military intelligence, reportedly said that the rebels reached the nuclear base and that their intention was to acquire small Soviet-era nuclear devices in order to “raise the stakes” in their mutiny.

Wagner rebels approached a Russian nuclear weapons storage site near Voronezh to get nuclear “backpacks,” Ukraine’s military intelligence chief claimed. The White House said it could not corroborate the claim.

A White House spokesperson said he could not corroborate the report and added that the United States “had no indication at any point that nuclear weapons or materials were at risk” during the Wagner event.

To help improve transparency on this issue, below we review what U.S. and NATO sources have stated recently about Russian nuclear landmines and non-strategic nuclear forces in general (for a more detailed overview of Russian nuclear forces, see our latest Nuclear Notebook).

Western Statements About Russian Nuclear Landmines

Whether or not the Wagner rebels got to or near a Russian nuclear weapons storage site (or what their intensions were), or whether nuclear weapons potentially stored there were at risk, the episode raises the question if Russia still has nuclear “backpacks” or landmines?

The answer appears to be yes – at least in some form. Recent U.S. Intelligence Community reports refer to them repeatedly, including a U.S. State Department report from 2023. But it is unclear what the status of the Russian landmines is: Are they part of the operational forces or leftovers from the Cold War in queue for dismantlement?

Before examining that question, it is useful to first review what U.S. and NATO sources have said about Russian landmines.

Refences to Soviet-era nuclear landmines can be found in many declassified Intelligence reports. One Central Intelligence Agency assessment from 1981 reported that the Soviet Union “may have introduced nuclear landmines” and a Defense Intelligence Agency guide reportedly listed them. But the wording in these reports were “may have” or “possibly have,” indicating a lower level of confidence. When the Soviet Union broke apart, the issue of “loose nukes” became a prominent concern – especially small weapons that could be easily transported. In a speech at the Stimson Center in 1994, for example, then US Defense Secretary William Perry expressed concern about the danger of loose tactical nuclear weapons in Russia, “such as nuclear artillery shells, land mines and others.” In 1997, Alexander Lebed, a former Russian general and advisor who had been fired by President Yeltsin, claimed Russia had lost track of 100 of 250 suitcase nuclear bombs. The U.S. Government and others questioned the claim and Lebed later withdrew his claim.

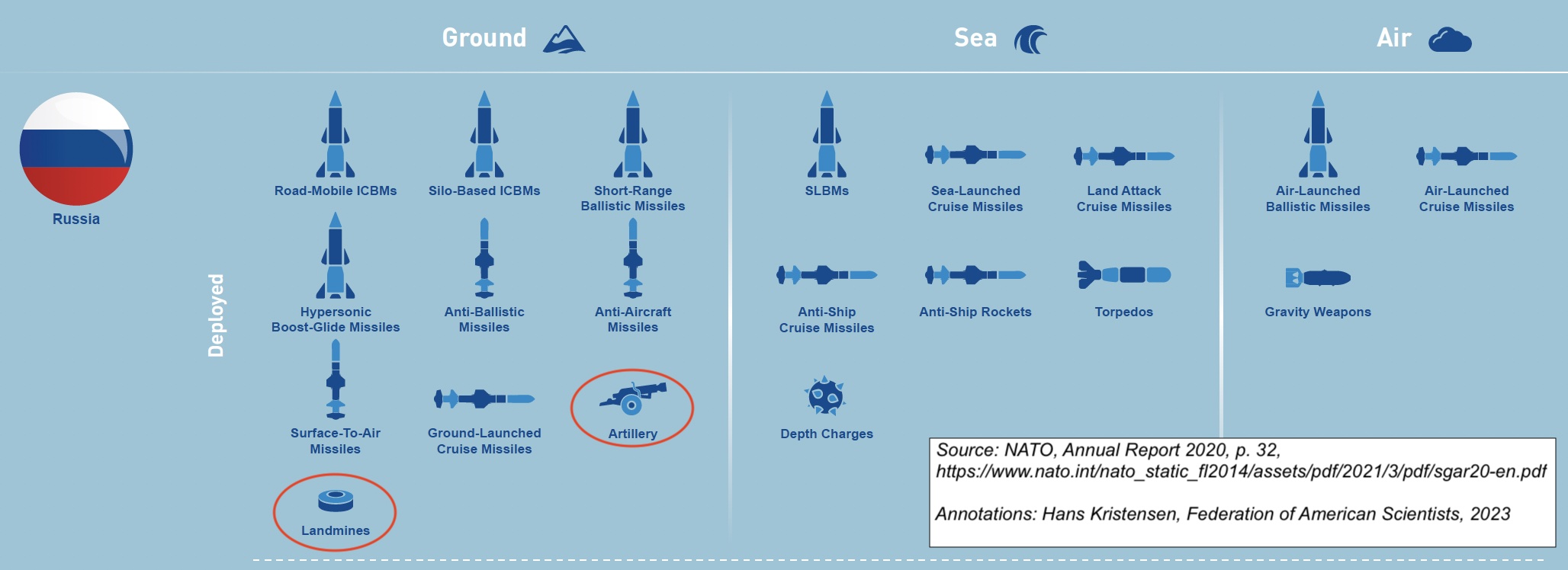

These were extraordinary claim for which no evidence was provided and Lebed later withdrew his claim. Yet the rumor that Russia has nuclear landmines has continued to percolate in the public debate and studies. The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review from February 2018 did not list landmines in its overview of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons. But the following year, one Pentagon official told Congress that the Russian non-strategic nuclear arsenal included “nuclear landmines, and nuclear artillery shells…” NATO appeared to pick up on that in its Annual Report from 2020 that listed both “landmines” and “artillery” (see image below). (It should be noted that neither the U.S. Department of State’s 2022 compliance report nor its 2023 non-strategic nuclear weapons report mentions nuclear artillery.)

NATO in 2020 listed both landmines and artillery in its overview of Russian nuclear forces.

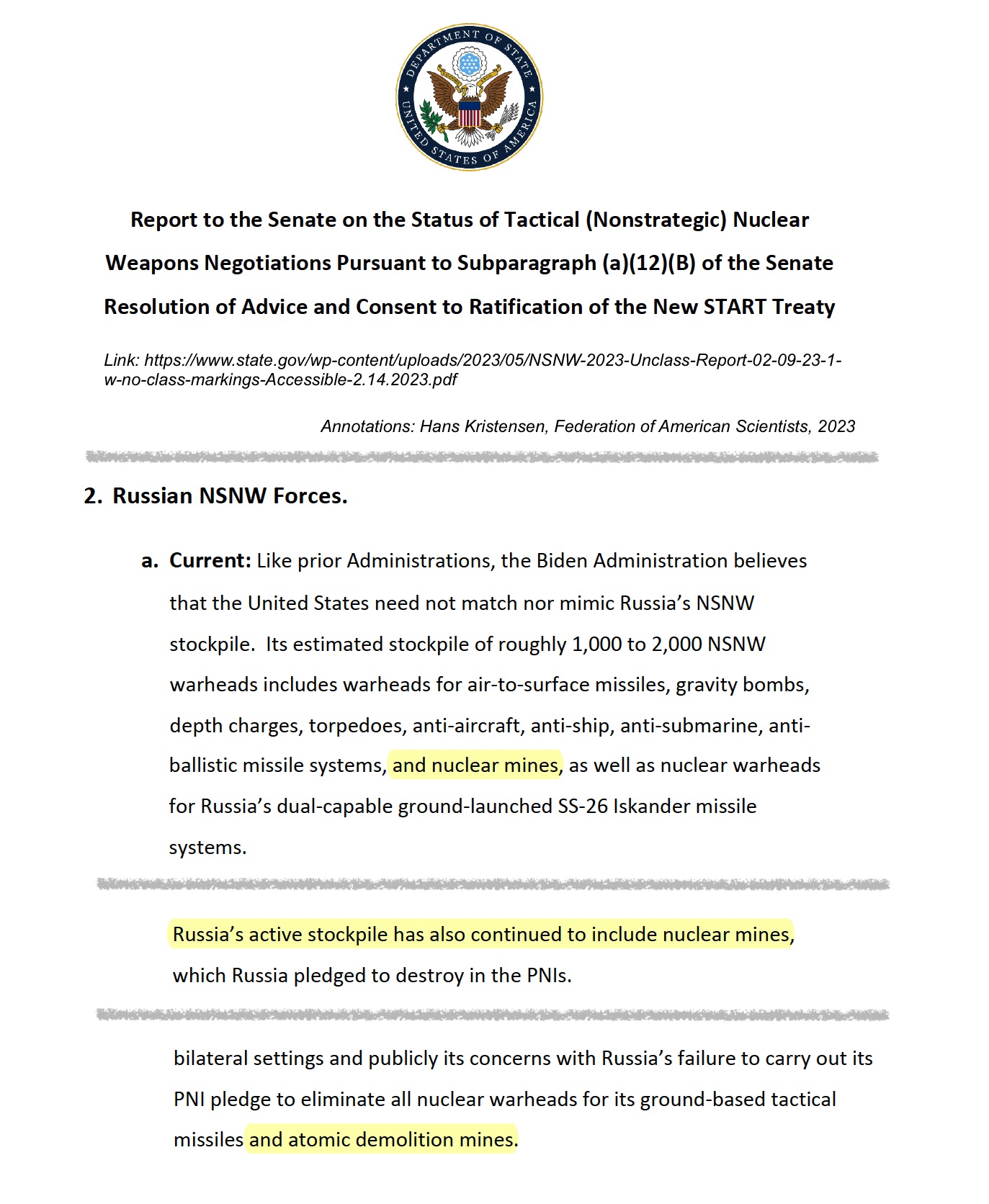

References to Russian nuclear landmines have also appeared frequently in the U.S. State Department’s annual reports on arms control compliance. The report from 2020 listed “atomic demolition mines” as part of Russia’s “active” stockpile of non-strategic nuclear weapons. The 2021 report did not explicitly mention nuclear mines in the active stockpile, and the 2022 report changed the language slightly to the active stockpile “has also continue to include nuclear mines.”

The latest compliance report from 2023 does not include the usual large section on the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives and Russian non-strategic weapons. Instead, that section was moved into a special report on non-strategic nuclear weapons that Congress had requested as part of its approval of the New START treaty. That report, published in February 2023, reiterates that Russia’s “active” non-strategic nuclear stockpile incudes nuclear mines (see image below).

Recent U.S. Intelligence reports refer repeatedly to the existence of Russian nuclear landmines, although it is uncertain how operational they are. The reports do not refer to nuclear artillery.

Russian Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

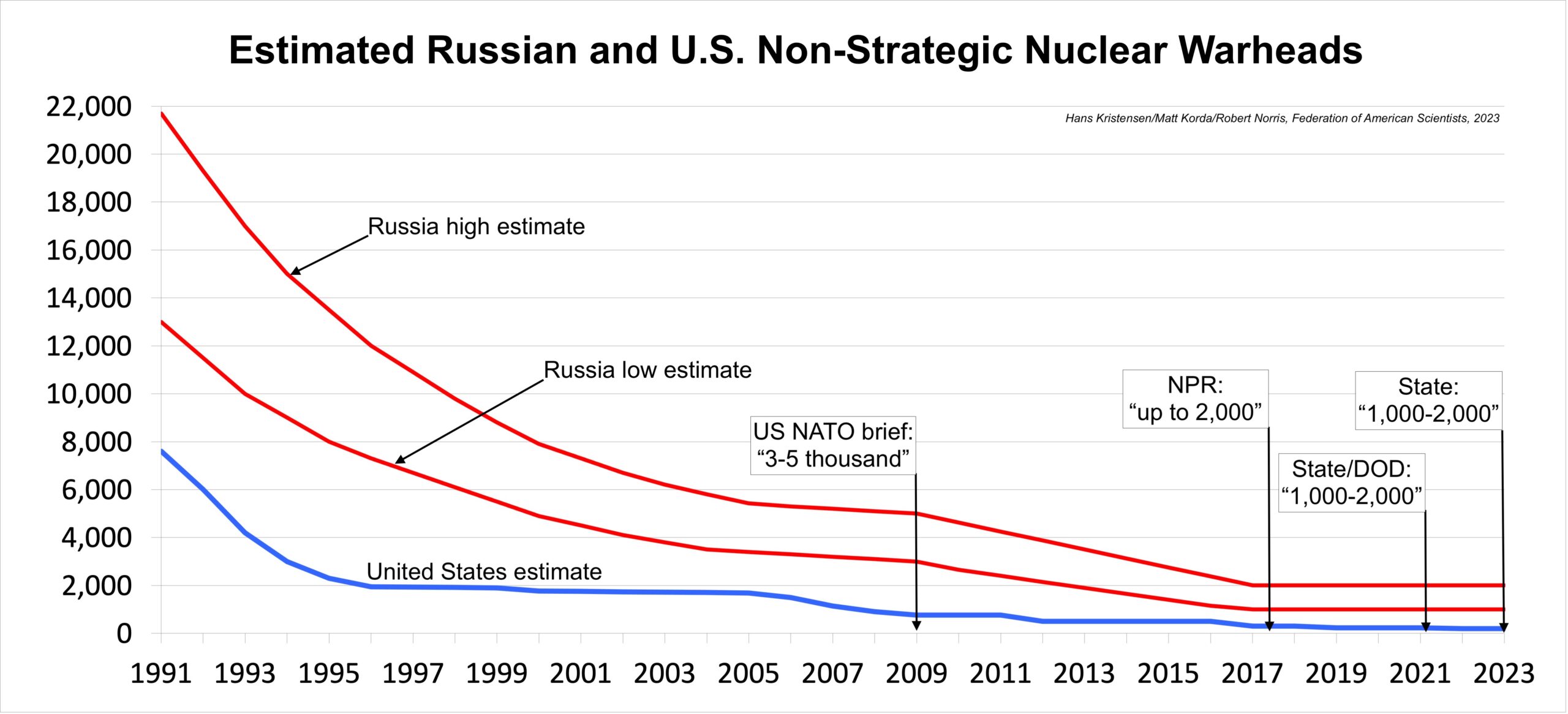

The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review in 2018 estimated that Russia had “up to 2,000” non-strategic nuclear weapons (this was close to the estimate we provided the same year). The NPR estimate was a significant reduction from the “3-5 thousand” Russian warheads listed by Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy James Miller in a briefing to NATO in 2009. Subsequent estimates published by the U.S. Intelligence Community (see above) indicate that the 2018 NPR number was at the high end of an estimated range of 1,000-2,000 warheads. Plotting these numbers from the much higher estimated inventory at the end of the Cold War shows this reduction of the Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons arsenal:

Russia’s stockpile of nuclear warheads for non-strategic forces has decreased significantly since the early-1990s – even during the past 15 years – and is estimated to be down to 1,000-2,000 warheads (including retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Interestingly, the U.S. State Department stated in 2022 that the Russian “active stockpile” of 1,000-2,000 non-strategic nuclear warheads included “warheads awaiting dismantlement…” This is curious because in the United States, warheads awaiting dismantlement are not considered “active” or part of an “active stockpile.” Rather, “active” warheads are part of the Department of Defense stockpile that includes both active and inactive warheads. “Active” warheads have all components installed; inactive warheads would need to have those components reinstalled first in order to be able to function.

This suggests that some of the Russian non-strategic warheads that are frequently portrayed in the public debate as part of the arsenal may in fact be retired warheads awaiting dismantlement. Although uncertain, nuclear landmines might be part of that inventory (nuclear artillery shells may be another part of the “awaiting dismantlement” inventory).

In addition to the uncertainty about the status of landmines in the Russian arsenal, advocates for modernization of the U.S. nuclear arsenal have claimed that Russian is expanding its non-strategic nuclear arsenal. Former STRATCOM commander Admiral Charles Richard told Congress in 2020 that “Russia’s overall nuclear stockpile is likely to grow significantly over the next decade – growth driven primarily by a projected increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added.)

The basis for that projection is unknown and uncertain. Russia is certainly modernizing its arsenal and fielding more types of weapons that the U.S. intelligence community claims are dual-capable. But how many of those launchers will actually be assigned nuclear warheads is another question. The latest U.S. State Department report acknowledges a Russian increase but cautions that “by how much is uncertain.”

Warhead projections are partially influenced by the expected growth of delivery platform deployments. But just because the number of dual-capable launchers in a weapons category is increasing doesn’t necessarily therefore mean that the number of warheads assigned to that weapons category is also increasing.

In the U.S. nuclear arsenal, for example, not all dual-capable F-15E and F-16 fighter-bombers are assigned nuclear weapons. And just because the F-35A Block 4 upgrade is intended to facilitate integration of nuclear technology, doesn’t therefore mean that all F-35A will be part of the nuclear posture and assigned nuclear weapons.

Simplistic dual-capable launcher counting as a basis for warhead projections could lead to exaggerated numbers.

So, there is much uncertainty about Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons and how the U.S. Intelligence Community makes projections about them. A first step to reducing that uncertainty is to ask questions.

Additional background: Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans in Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?

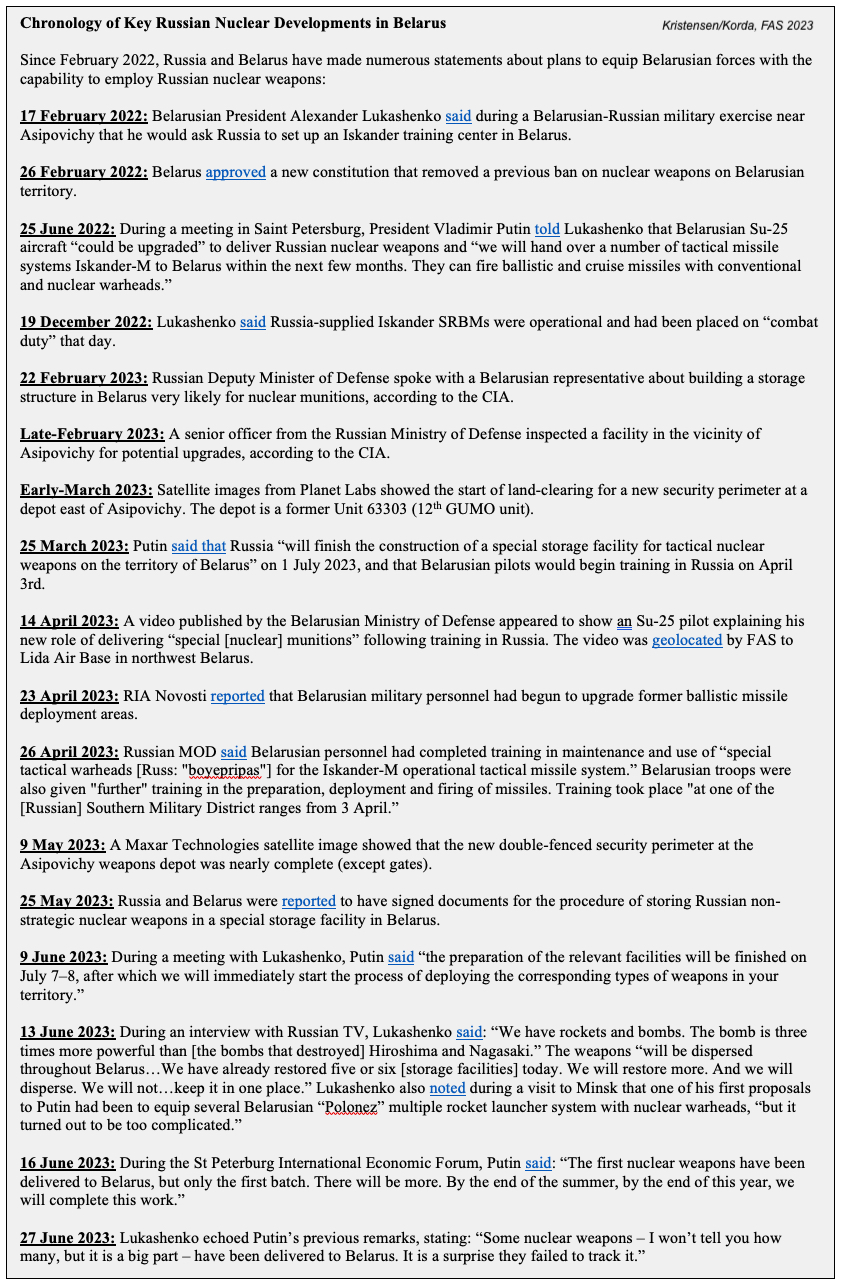

Shortly after a Russian defense official inspected possible nuclear weapons storage site near Asipovichy, construction of additional security perimeters began at depot.

New satellite images show that the construction of a double-fenced security perimeter is underway at a weapons depot near the town of Asipovichy in central Belarus.

The US Central Intelligence Agency reported in late-February 2023 that a senior officer from the Russian Ministry of Defense had inspected a facility in the vicinity of Asipovichy (occasionally also spelled Osipovichi) for a potential upgrade to nuclear weapons storage.

Asipovichy is the deployment area for the dual-capable Iskander (SS-26) launchers that Russia supplied to Belarus in 2022. Interestingly, the weapons depot featured in this article is roughly only 25 kilometers southeast of a vacant military base that, according to the New York Times, could be used to house relocated Wagner Group fighters in Belarus. This does not, however, imply any connection between the Wagner Group and Russian nuclear deployments in Belarus, which would be overseen by the Russian Ministry of Defence’s 12th Main Directorate (also known as the 12th GUMO).

President Vladimir Putin announced in March that Russia plans to complete a nuclear weapons storage site in Belarus by July 1st, 2023, but he later modified the timeline to July 7th-8th, apparently due to delays with preparing the storage facilities.

It is important to emphasize upfront that at this stage, we are not able to make a positive identification that this site is intended for or will definitively be used to store Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus. As we discuss in detail below, while the construction timeline and some signatures correlate with a potential nuclear storage site, other signatures do not, and these raise uncertainty about the purpose of the upgrade at the Asipovichy depot. In fact, overall, we are underwhelmed by the lack of visual evidence of the construction and infrastructure that would be expected to support the deployment of Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus. We have also surveyed satellite imagery of numerous other military facilities at locations mentioned in various reports, but we have yet to find visual evidence that conclusively indicates the presence of an active nuclear weapons facility on the territory of Belarus.

Below we survey facilities at various locations in Belarus that have been mentioned in the public debate as potential transit or deployment areas for nuclear-capable forces or even nuclear weapons.

Iskander Missile Launchers

Asipovichy is an important region because it is the location of new nuclear-capable Islander short-range missile launchers that Russia transferred to Belarus in 2022. One Belarusian news report stated the transfer happened in December, but satellite images show what appear to be Iskander launchers at the training site to the west of Asipovichy in August and October 2022 (see images below).

Iskander launchers have been observed at a training range west of Asipovichy several times.

The Russian Ministry of Defense announced in late-April 2023 that Belarusian personnel had completed training in maintenance and use of “special tactical warheads [Russ: “boyepripas”] for the Iskander-M operational tactical missile system” at one of Russia’s Southern Military District ranges in early April.

The Belarusian brigade base for the Iskander launchers is thought to be located in the southern outskirts of Asipovichy, roughly seven miles west of the depot undergoing upgrades. Some five miles to the west of that garrison, there is a training range where Iskander launches have been seen on several occasions (see image below).

Belarusian Iskander military photos were geolocation to the training range west of Asipovichy.

Most Russian Iskander bases have extensive support facilities as well as a distinctive missile storage site (see image below). No similar facility has been found near Asipovichy. The Belarusian military probably uses different storage standards and could potentially use the dirt-covered bunkers in the south-west corner of the facility.

The Belarusian Iskander base does not include the distinctive missile storage site found at most Russian Iskander bases.

A few Russian Iskander bases also do not have the more elaborate missile storage site. That includes the Iskander base in Kaliningrad.

Fighter-Bomber Aircraft

In their public remarks during a meeting in St. Petersburg on 25 June 2022, Presidents Putin and Lukashenko explicitly mentioned nuclear upgrade of Belarusian Su-25 aircraft. A year later, on 14 April 2023, the Belarusian Ministry of Defense published a video of what appeared to be an Su-25 pilot at Lida Air Base explaining the new nuclear role.

An examination of the Lida base area shows no physical indications of upgrades of the kind that are thought would be required to support nuclear weapons deployment. The very latest imagery shows early construction of what appears to be an additional security perimeter around the munitions storage area at the base (see image below). It is too soon to tell, but as in the case of the Asipovichy upgrade, a second fence security perimeter does not necessarily suggest a nuclear weapons upgrade; it could simply be improvement of an existing security infrastructure.

Construction of a second security perimeter at Lida Air Base has begun but there is yet no clear indication this is related to nuclear weapons.

There have also been some speculations that the Baranavichy Air Base further to the south, which is equipped with more modern Su-30SM jets, might be a potential candidate for the nuclear mission. We are not aware of any official statements to that effect and have not seen any observable indications of physical upgrades needed to support nuclear operations there.

As with the Iskander base area upgrades near Asipovichy, we can’t positively exclude the existence of an undetected facility near the western air bases. But so far, we don’t see conclusive physical indications of nuclear weapons related upgrades on or near Lida or Baranavichy. It is also relevant to mention that both bases are very close to NATO territory; Lida is only about 20 miles (35 kilometers) from Lithuania.

Warhead Transportation

On June 16th, Putin announced: “The first nuclear weapons have been delivered to Belarus, but only the first batch. There will be more. By the end of the summer, by the end of this year, we will complete this work.”

Careful monitoring of the 12th GUMO’s transit hub at Sergiev Posad has not yet indicated the shipment of specialized nuclear-related materials, such as fencing, certified loading equipment, vault doors, or environmental control systems. However, on June 27th, a group that monitors the Belarusian railway industry reported that nuclear weapons and related equipment would be delivered to Belarus in two stages, one in June and one in November––echoing Putin’s delivery timeline. The group reported that the shipments would involve three departures planned from Potanino, Lozhok, and Cheboksary stations in Russia, arriving at Prudok station in Belarus––more than 200 kilometers north of the Asipovichy depot. These locations in Russia are hundreds of kilometers away from known nuclear storage sites, and so could either be locations for subcomponents or security equipment rather than the warheads themselves, or they could potentially be an attempt to obfuscate where the warheads would actually be coming from.

Preparation of rail transfer points and storage would require construction of a number of unique security features and support facilities. An examination of satellite images of the Prudok station area in Belarus, however, revealed no observable indication of construction needed to safeguard nuclear weapons (see image below).

Satellite imagery of the Prudok rail station and depot area reported as the first transfer point of Russian nuclear weapons into Belarus show no observable indication of preparations to nuclear weapons storage.

Many Uncertainties

It is important to be clear that these satellite images do not prove decisively that the construction at Asipovichy or other known facilities is related to nuclear weapons storage. It could potentially be related to non-nuclear weapon systems, such as air-defense missiles. There are several uncertainties that should be mentioned and carefully considered:

First, the security perimeter has two inner fences, less than the three or four normally seen at Russia nuclear weapons storage sites. This is a significant difference, because the standard of at least three layers of fencing is directly correlated with the ability of the fence disturbance system to detect security threats to the complex. Fewer layers of fencing (and thus less clear space) could cause the microwave detection system to be accidentally triggered by movement inside the complex itself. To avoid that, vegetation has been removed along the new 12-meter wide inner security perimeter. Construction is ongoing and there is so far no visual indication of electronic sensors inside the new perimeter.

Construction of an additional double-fence security perimeter began at a weapons depot east of Asipovichy in central Belarus shortly after a senior Russian defense official inspected a facility in the area for potential storage of nuclear weapons

In comparison, Russian base- and national-level nuclear weapons storage facilities have extensive security features. The base-level storage facility near Tver approximately 325 kilometers (200 miles) from the Belarusian border has considerably stronger security features around the weapons bunkers (see image below).

The outline of this Russian base-level nuclear weapons storage site near Tver is very different from the Asipovichy site.

Second, there is no bunker visible inside the enclosure, another normal feature of Russian nuclear weapon storage sites. Apart from physical protection, nuclear weapons require climate-controlled storage facilities.

Third, there is no visible segregated housing for the large number of Russian 12th GUMO personnel that would be needed to protect and manage nuclear warheads.

Fourth, the depot is next to a storage site for conventional high explosives. As other researchers have pointed out, it would be highly unusual for conventional and nuclear warheads to be stored within the same perimeter in order to maintain the security of the warheads and to segregate the chain of custody between Russian 12th GUMO personnel and Belarusian army personnel.

These differences could potentially be explained if the Belarusian site is a temporary transit site and not intended for permanent storage, but rather to introduce nuclear weapons in a crisis.

It is also curious that part of the new double-fence construction extends around a group of buildings that were constructed in 2017-2018, long before any statements were made about deploying Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus.

Even if Russia intends to follow through on its planned construction of a storage site in Belarus, it is not guaranteed that any nuclear weapons would actually cross the border in peacetime. Rather, it is possible that Russia’s actions instead constitute the building blocks for a potential future decision on deployment. Moreover, some analysts have suggested that these actions could be deliberately designed to remind the West of Russia’s nuclear-armed status, rather than actually shift Russian force posture.

In total, the facility upgrade at Asipovichy is important to monitor given the CIA report about Russia nuclear-related storage inspections in the area. So far, however, our observations and analyses show no clear observable indicators of construction of the facilities we expect would be needed to support transport and deployment of Russian nuclear weapons into Belarus. As always, we don’t know what we don’t know and it is of course possible that there are other facilities that we are not aware of that would indicate nuclear weapons activities.

Positive identification of this and other potential facilities will have to await additional information. And we look forward to the contribution of other researchers.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons, and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Associate and Project Manager Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column examines Russia’s nuclear arsenal, which includes a stockpile of approximately 4,489 warheads. Of these, some 1,674 strategic warheads are deployed on ballistic missiles and at heavy bomber bases, while an approximate additional 999 strategic warheads, along with 1,816 nonstrategic warheads, are held in reserve. The Russian arsenal continues its broad modernization intended to replace most Soviet-era weapons by the late-2020s.

Read the full “Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

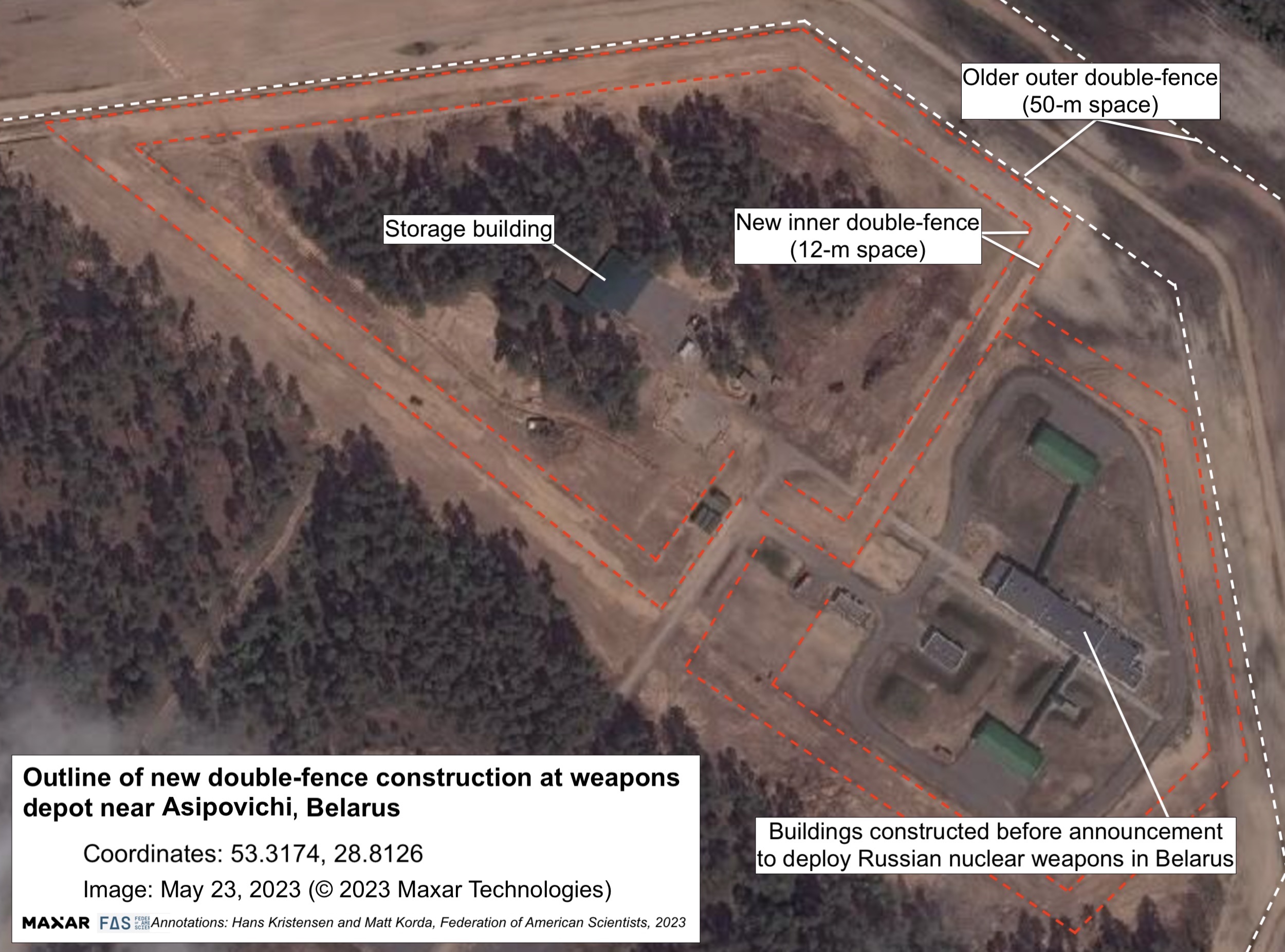

Video Indicates that Lida Air Base Might Get Russian “Nuclear Sharing” Mission in Belarus

On 14 April 2023, the Belarusian Ministry of Defence released a short video of a Su-25 pilot explaining his new role in delivering “special [nuclear] munitions” following his training in Russia. The features seen in the video, as well as several other open-source clues, suggest that Lida Air Base––located only 40 kilometers from the Lithuanian border and the only Belarusian Air Force wing equipped with Su-25 aircraft––is the most likely candidate for Belarus’ new “nuclear sharing” mission announced by Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The Belarusian MoD’s military channel features a Belarusian pilot standing in front of a Su-25 aircraft at an unidentified air base.

The video shows the pilot standing in a revetment with a Su-25 in the background. The interview takes place at a grassy location with trees in the distance along with several distinct features, including two drop tanks flanking the Su-25 on either side, and objects behind the aircraft. The revetment itself is also somewhat distinct, as the berm wraps around three sides of the hardstand and the size and orientation of the six rectangular tiles across the opening are clearly visible in the video.

The Belarusian MoD’s video shows a Su-25 aircraft sitting in a revetment surrounded by berms and trees, with drop tanks visible on either side of the aircraft.

Although the pilot is announcing the completion of their training that occured in Russia, the footage was filmed and released by the Belarusian Ministry of Defense. This factor seemed to indicate that the filming location took place in Belarus instead of at the training center in Russia. Additionally, while Su-25s have operated out of other air bases in Belarus throughout the war, including Luninets Air Base, the only Su-25 wing in the Belarusian Air Force is based at Lida.

After analyzing the satellite imagery of other possible candidate hardstands, including those at Luninets and Baravonichi, the video’s signatures appeared to most closely match a specific hardstand found at Lida Air Base. There are multiple revetments on the western side of the base, but the existence and location of a pole on top of one particular sloped berm, as well as the location of the trees in the background, the drop tanks, and the orientation of the tiles on the tarmac all align closely with features from the video footage. While the specific aircraft from the video has yet to be identified (although the individualized camouflage patterns on each Su-25 will help with this process), all of these factors suggest the video was filmed at Lida Air Base.

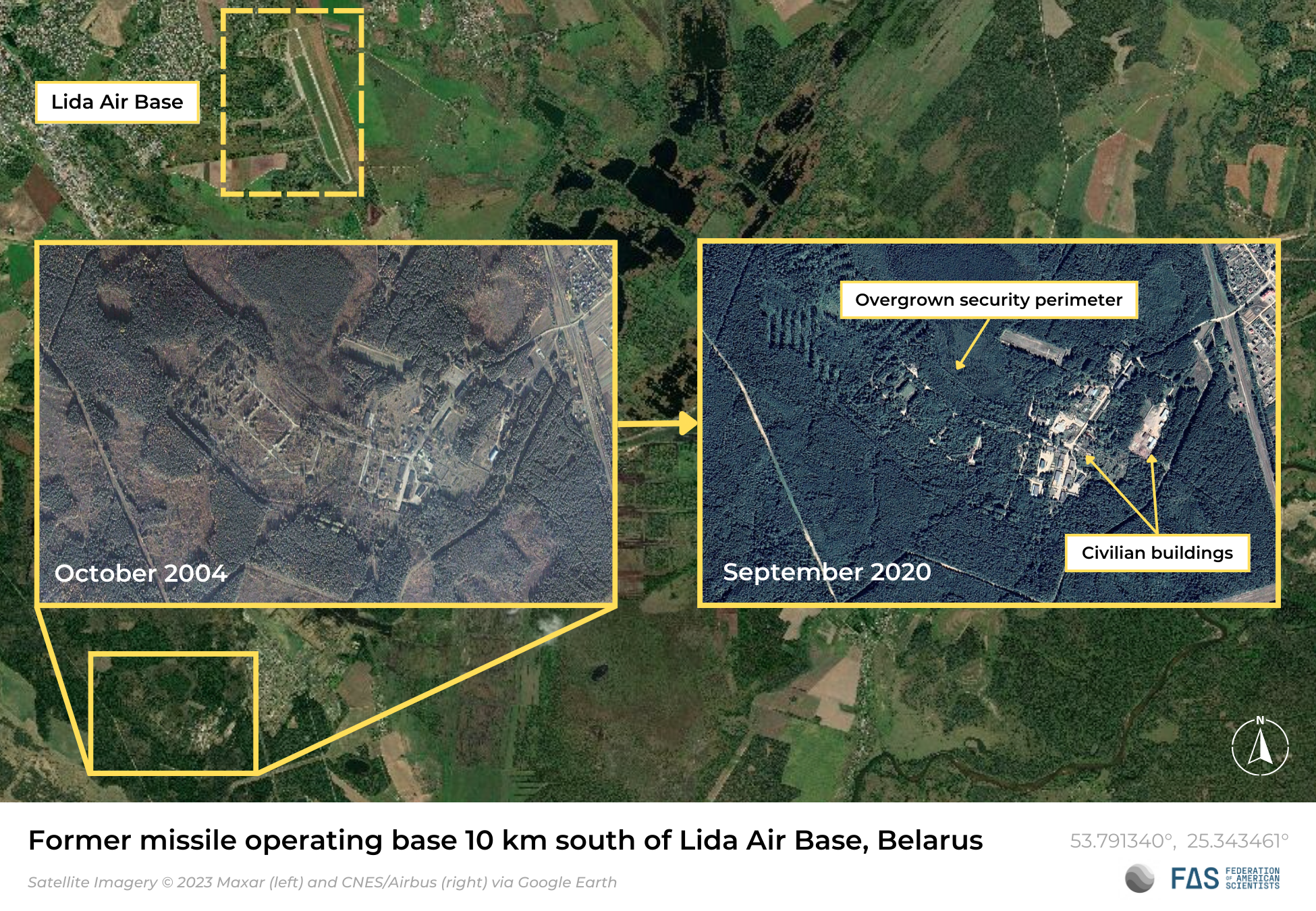

During and immediately after the Cold War, the Lida area was was home to a missile operating base for the 49th Guards Missile Division, first for the SS-4 MRBM, then the SS-20 IRBM, and finally the SS-25 ICBM before the division disbanded in 1997. The former missile operating base is located only ten kilometers south of the air base, and while some areas appear to still be active (perhaps in a civilian or other military role), others appear to be overgrown.

Currently, Lida is home to the Belarusian Air Force’s 116th Guards Assault Aviation Base, which flies the Su-25 Frogfoot––the type of plane confirmed by both the Belarusian Ministry of Defense and President Putin as being newly re-equipped to deliver tactical nuclear weapons. Lida’s Su-25 aircraft have also reportedly been used to conduct strikes in Ukraine.

Two additional data points suggest that Lida is the most likely candidate: on March 25th, Putin announced in an interview with Rossiya 24 that Belarusian crews would begin training in Russia on April 3rd. Belarusian Telegram channels subsequently identified these crews as being from Lida, with one channel stating that “According to my sources, the entire flight and engineering staff of the Lida air base will undergo retraining in Russia” (h/t Andrey Baklitskiy).

In addition, on April 2nd, Russia’s ambassador to Belarus stated that Russian nuclear weapons will be “moved up close to the Western border of our union state” (the supranational union of Russia and Belarus). Although the ambassador declined to offer a more specific location, Lida Air Base is located closer to NATO territory than any other suitable candidate site––only about 40 kilometers from Lithuania’s southern border and approximately 120 kilometers from Poland’s eastern border. Although this would mean a longer journey to transport the nuclear weapons from Russia (and could also make the weapons more vulnerable to NATO strikes), its proximity to Alliance territory would be a clear nuclear signal to NATO.

Challenges for the “nuclear sharing” mission

At the time of publication, it remained highly unclear whether Russia actually intends to deploy nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory, or whether it is developing the infrastructure needed to potentially deploy them in the future. It is clear, however, that such a deployment would likely come with logistical challenges.

President Putin’s March 25th announcement noted that Russia would begin training Belarusian nuclear delivery crews on April 3rd and “on July 1, we [will finish] the construction of a special storage facility for tactical nuclear weapons on the territory of Belarus.” Judging by the April 14th video released by the Belarusian Ministry of Defence, the Belarusian crews completed their training within this short period. This is an extraordinarily fast turnaround for completing the certification process; by contrast, nuclear certification for US/NATO nuclear weapon systems can take months, or even years. And as expert Bill Moon pointed out during a recent roundtable discussion, specialized equipment for warhead transportation and handling would also need to undergo intensive certification processes, which can take months.

Additionally, other Russian nuclear storage sites have taken years to upgrade. Usually, permanent nuclear storage sites in Russia have multi-layered fencing around both the perimeter as well as the storage bunkers themselves inside the complex, which can take months to install. Even a temporary site would still require extensive security infrastructure. Moreover, personnel from the 12th GUMO––the department within Russia’s Ministry of Defence that is responsible for maintaining and transporting Russia’s nuclear arsenal––would also necessarily be deployed to Belarus to staff the storage site (regardless of whether nuclear weapons were present or not) and would need a segregated living space. Bill Moon, who has decades of experience working alongside the 12th GUMO, estimates that this could be a contingent of approximately 100 personnel, including warhead maintainers, guards, and armed response forces. Constructing these kinds of facilities could also take many months to build up, revitalize, and maintain. Although it may be possible to complete construction by Putin’s July 1st deadline, a storage facility would not be ready to actually receive warheads until all of the specialized equipment and personnel were in place.

In order to meet this schedule, as Bill Moon highlighted during the recent roundtable discussion, personnel from the 12th GUMO would have to already be preparing and securing the warhead transportation route, as well as the rail spur used to transfer the warheads from trains to specialized trucks. Lida Air Base has an enclosed rail spur on-site that could potentially be used for this, although it could also require additional security infrastructure. Overall, such a deployment would be quite a difficult task: not only would deploying warheads to Lida Air Base be a very long distance for the warheads and associated equipment to travel, but both the Russian and Belarusian rail networks have experienced significant disruptions due to the war in Ukraine, from both anti-war activists and Ukrainian strikes.

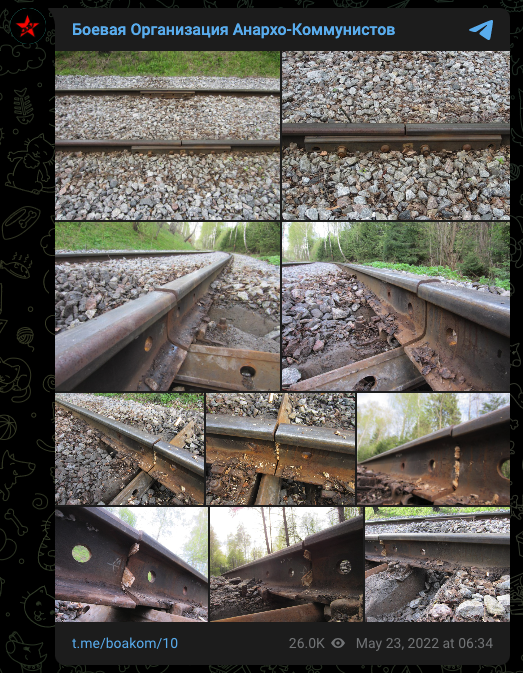

Notably, in May 2022 a Russian anarcho-communist activist group announced that they had sabotaged the rail tracks leading out of the 12th GUMO’s main transit hub at Sergiev Posad in an act of protest against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This site would be used to stage and transport specialized storage and warhead handling equipment, such as fencing, vault doors, and environmental control systems––as well as crews––from Russia to Belarus. In particular, the activist group claimed to have used standardized construction tools to unscrew the nuts connecting the rail joints together, thus allowing them to lift and move the rail tracks.

Telegram channel announcing a Russian anarcho-communist group’s successful sabotage of a rail line leading to the 12th GUMO’s main transit hub at Sergiev Posad

The group specifically noted that they wanted to conduct a type of sabotage that was “less visible so the train wouldn’t have time to slow down to a stop.” Given the relative ease with which this attack was conducted, the relative invisibility of the sabotage, and the distance that the warheads and equipment would need to travel to reach Lida or another destination inside Belarus, it is clear that the 12th GUMO’s task of securing the rail lines would be important, yet extremely difficult to accomplish.

Given all of these complexities, if Putin does indeed intend to transfer warheads to Belarus, it is highly unlikely that such a deployment would take place until at least after Putin’s July 1st construction deadline, and it could also be coupled with yet another high-level nuclear signal.

Background Information:

- “United States nuclear weapons, 2023,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 2023.

- “Russian nuclear weapons, 2022,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2022.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Was There a U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accident At a Dutch Air Base? [no, it was training, see update below]

Did the U.S. Air Force suffer a nuclear weapons accident at Volkel Air Base?

Did the U.S. Air Force suffer a nuclear weapons accident at an airbase in Europe a few years back? [Update: After USAFE and LANL initially declined to comment on the picture, a Pentagon spokesperson later clarified that the image is not of an actual nuclear weapons accident but of a training exercise, as cautioned in the second paragraph below. The spokesperson declined to comment on the main conclusion of this article, however, that the image appears to be from inside an aircraft shelter at Volkel Air Base.]

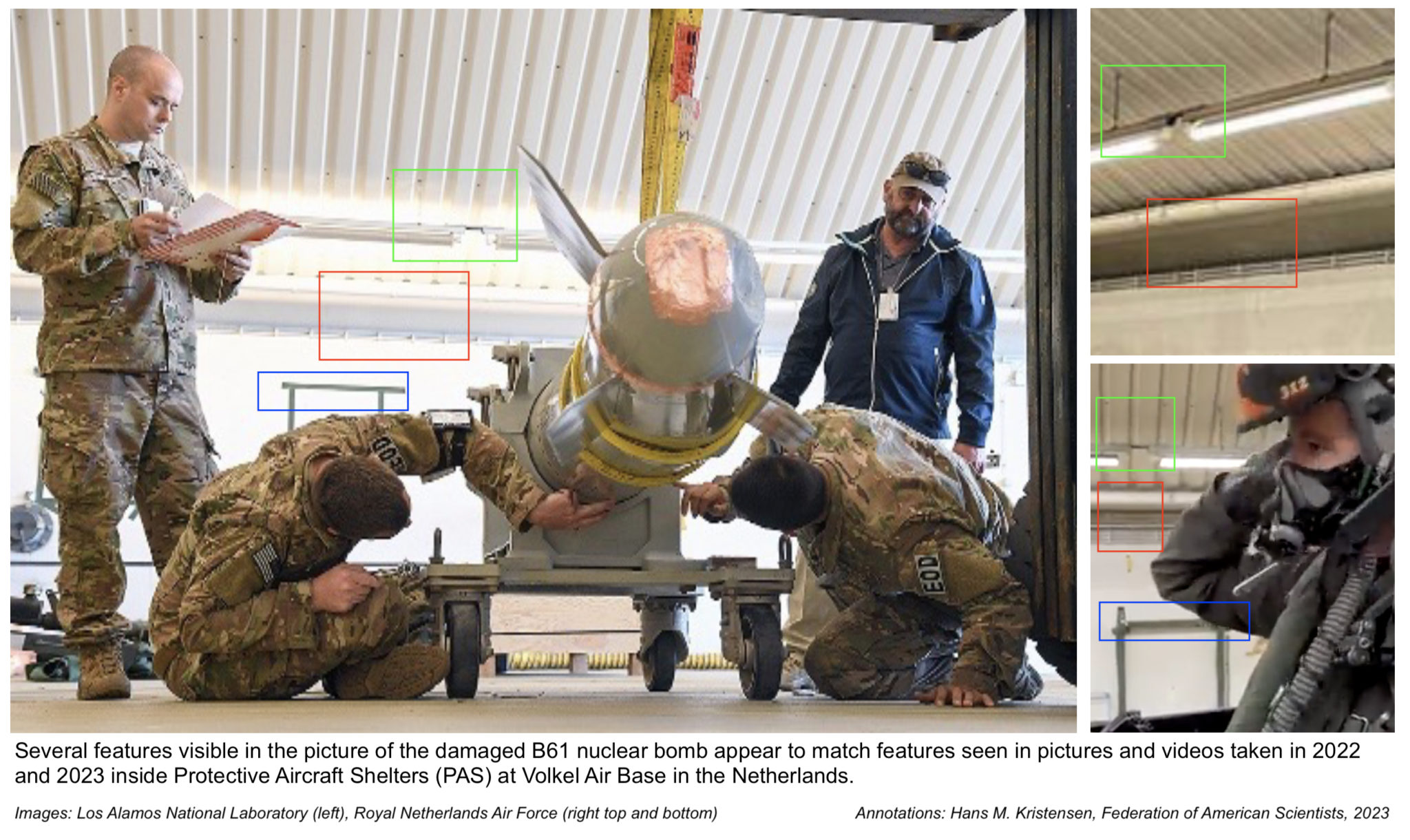

A photo in a Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) student briefing from 2022 shows four people inspecting what appears to be a damaged B61 nuclear bomb. The document does not identify where the photo was taken or when, but it appears to be from inside a Protective Aircraft Shelter (PAS) at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands.

It must be emphasized up front that there is no official confirmation that the image was taken at Volkel Air Base, that the bent B61 shape is a real weapon (versus a trainer), or that the damage was the result of an accident (versus a training simulation).

If the image is indeed from a nuclear weapons accident, it would constitute the first publicly known case of a recent nuclear weapons accident at an airbase in Europe.

Most people would describe a nuclear bomb getting bent as an accident, but U.S. Air Force terminology would likely categorize it as a Bent Spear incident, which is defined as “evident damage to a nuclear weapon or nuclear component that requires major rework, replacement, or examination or re-certification by the Department of Energy.” The U.S. Air Force reserves “accident” for events that involve the destruction or loss of a weapon.

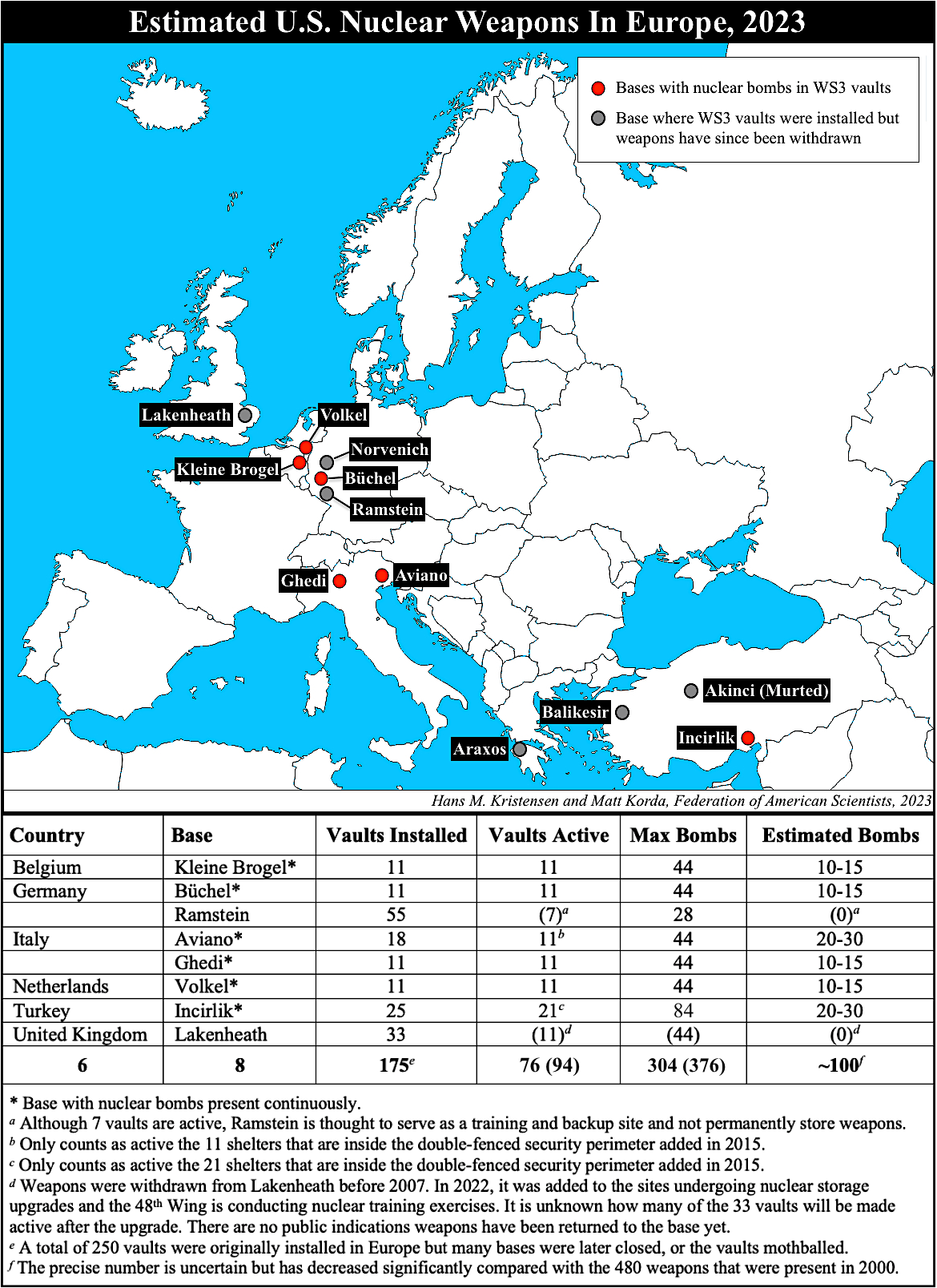

It is not a secret that the U.S. Air Force deploys nuclear weapons in Europe, but it is a secret where they are deployed. Volkel Air Base has stored B61s for decades. I and others have provided ample documentation for this and two former Dutch prime ministers and a defense minister in 2013 even acknowledged the presence of the weapons. Volkel Air Base is one of six air bases in Europe where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys an estimated 100 B61 nuclear bombs in total.

The United States is modernizing its air-delivered nuclear arsenal including in Europe and Volkel and the other air bases in Europe are scheduled to receive the new B61-12 nuclear bomb in the near future.

Image Description

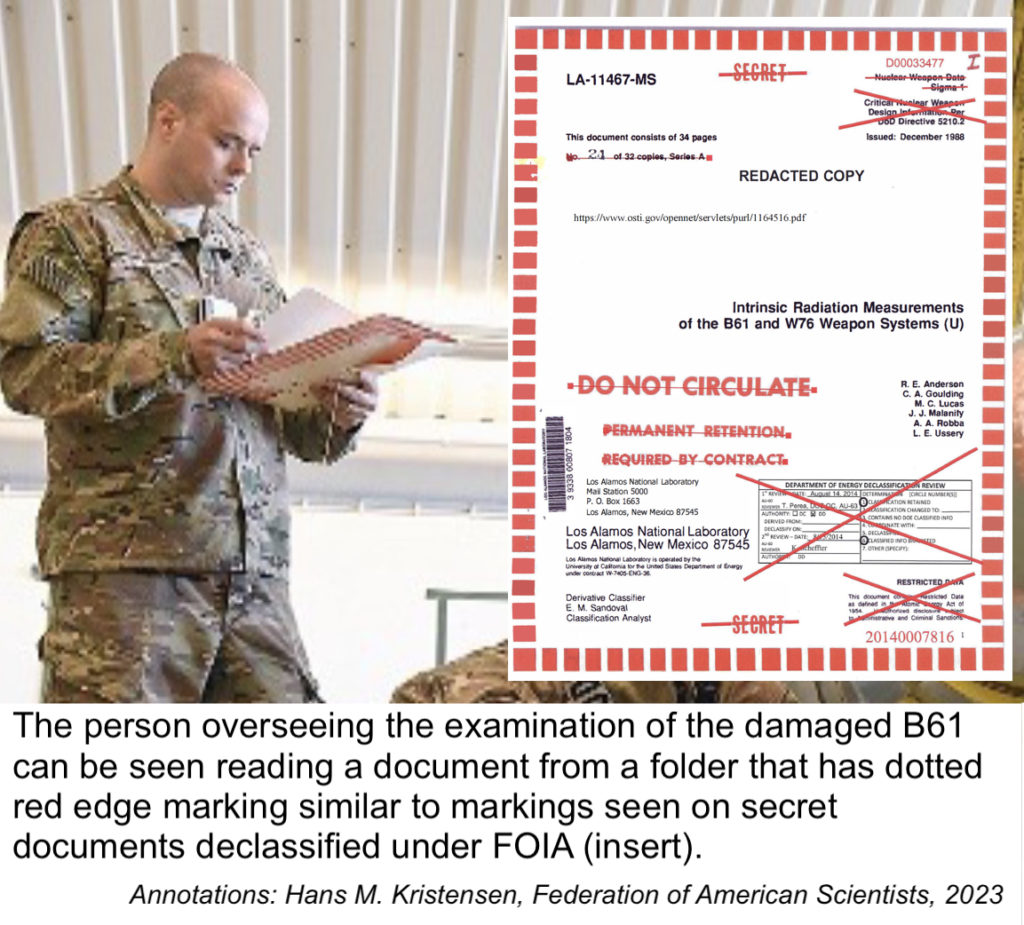

What does the image itself show? It appears to show a damaged B61 nuclear bomb shape strapped to a four-wheel trolly. The rear of the bomb curves significantly to the left and one of four tail fins is missing. There is also pink tape covering possible damage to the rear of the tail. The image first (to my knowledge) appeared in a Los Alamos National Laboratory student briefing published last year that among other topics described the mission of the Accident Response Group (ARG) to provide “world-wide support to the Department of Defense (DoD) in resolving incidents and accidents involving nuclear weapons or components in DoD custody at the time of the event.”

The personnel in the image also tell a story. The two individuals on the floor who appear to be inspecting the exterior damage on the weapon have shoulder pads with the letters EOD, indicating they probably are Explosive Ordnance Disposal personnel. According to the U.S. Air Force, “EOD members apply classified techniques and special procedures to lessen or totally remove the hazards created by the presence of unexploded ordnance. This includes conventional military ordnance, criminal and terrorist homemade items, and chemical, biological and nuclear weapons.”

The person to the left overseeing the operation appears to be holding a folder with red dotted color markings that are similar to color patterns seen on classified documents that have been declassified and released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) (see image to the right). The civilian to the right is possibly from one of the nuclear weapons laboratories. Los Alamos and Sandia both produced components to the B61 bomb.

What caused the damage to the B61 shape is unknown, but it appears to have been a significant force. It could potentially have been hit by a vehicle or bent out of shape by the weapons elevator of the underground storage vault.

Photo Geolocation

There is nothing in the photo itself or the document in which it was published that identify the location, the weapon, when it happened, or what happened. I have searched for the photo in search engines but nothing comes up. However, other photos taken inside Protective Aircraft Shelters (PASs) at Volkel Air Base show features that appear to match those seen in the accident photo.

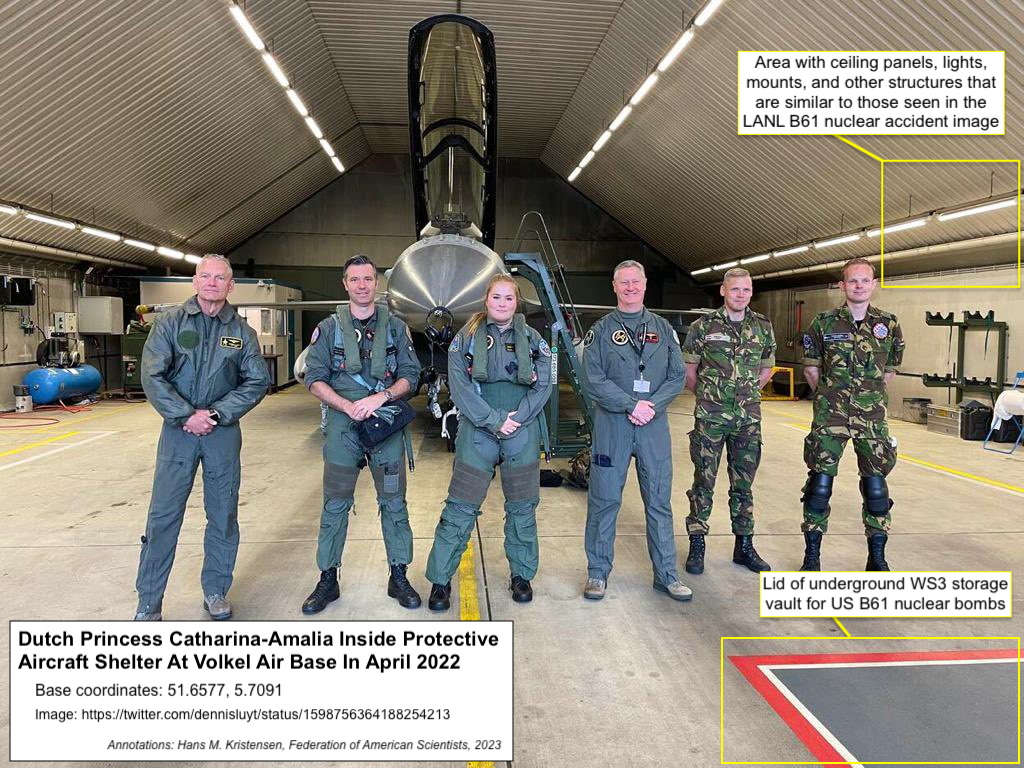

One of those photos is from April 2022 (the same month the Los Alamos briefing was published), when Dutch princess Catharina-Amalia visited Volkel Air Base and was taken on a flight in one of the F-16s. The Dutch Air Force commander highlighted the visit in a tweet that includes several photos, including one from inside an aircraft shelter. The photo shows the princess with Dutch air force officials including what appear to be the head of the Dutch air force and the commander of the nuclear-tasked 312th squadron at Volkel, an F-16 fighter-bomber, and part of the lid of an underground Weapons Storage System (WS3) vault built to store B61 nuclear bombs (see image below).

The 312th Squadron is part of the Dutch Air Force’s 1st Wing and is equipped with F-16 fighter-bombers with U.S.-supplied hardware and software that make them capable of delivering B61 nuclear bombs that the U.S. Air Force stores in vaults built underneath 11 of the shelters at the base. Dutch pilots receive training to deliver the weapons and the unit is inspected and certified by U.S. and NATO agencies to ensure that they have the skills to employ the bombs if necessary. In peacetime, the bombs are controlled by personnel from the U.S. Air Force’s 703rd Munition Support Squadron (MUNSS) at the base. If the U.S. military recommended using the weapons – and the U.S. president agreed and authorized use, the U.K. Prime Minister agreed as well, and NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) approved – then the weapon would be loaded onto a Dutch F-16 and the strike carried out by a Dutch pilot. Such an operation was rehearsed by the Steadfast Noon exercise in October last year.

One of these pilots (presumably), the commander of the 312th squadron, appeared in a Dutch Air Force video published in February on the one-year anniversary of the (second) Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the video, the commander climbs into the F-16 and puts on his helmet. At first a visor cover can be seen showing an orange-yellow mushroom cloud illustrating a nuclear explosion. However, when the video cuts and the commander turns to face the camera, the nuclear mushroom cloud cover is gone, presumably to avoid sending the wrong message to Russia (see below). The nuclear mushroom visor cover was also seen during the NATO Steadfast Noon exercise at Volkel AB in 2011.

These pictures and videos show features that indicate the B61 nuclear bomb accident picture is from Volkel Air Base. Unlike aircraft shelters at other nuclear bases in Europe, the Dutch shelters have ceilings made up of three flat surfaces: the two sides and the top. The surfaces include unique light fixtures and meet the side walls with unique pipes and grids. Moreover, the shelter wall has a gray structure outline that is very similar to one seen in the video. These different matching features are highlighted in the image below.

Nuclear Accident Management

Nuclear weapon designs such as the B61 are required to be “one-point safe,” which means the weapon must have a probability of less than one in one million of producing a nuclear yield if the chemical high explosives detonate from a single point. But if the weapon is not intact, such as during maintenance work inside a truck inside an aircraft shelter, a U.S. Air Force safety review discovered in 1997 – nearly three decades after the one-point safety requirement was established – that “nuclear detonation may occur” during a lightning storm. Improved lightning protection was quickly installed.

Management of accidents and incidents involving U.S. nuclear weapons at foreign bases is carried out in accordance with national and bilateral arrangements. The United States has held that the 1954 Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) relating to the stationing of U.S. armed forces in the Netherlands was sufficient for regulating , but the Dutch government has been pressing for greater consultation in the Netherlands United States Operational Group (NUSOG), a special bilateral a coordinating body established to develop and manage U.S. nuclear weapons accident response plans, procedures, training, and exercises. Disclosure of a dispute in 2008-2009 once more confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons in the Netherlands.

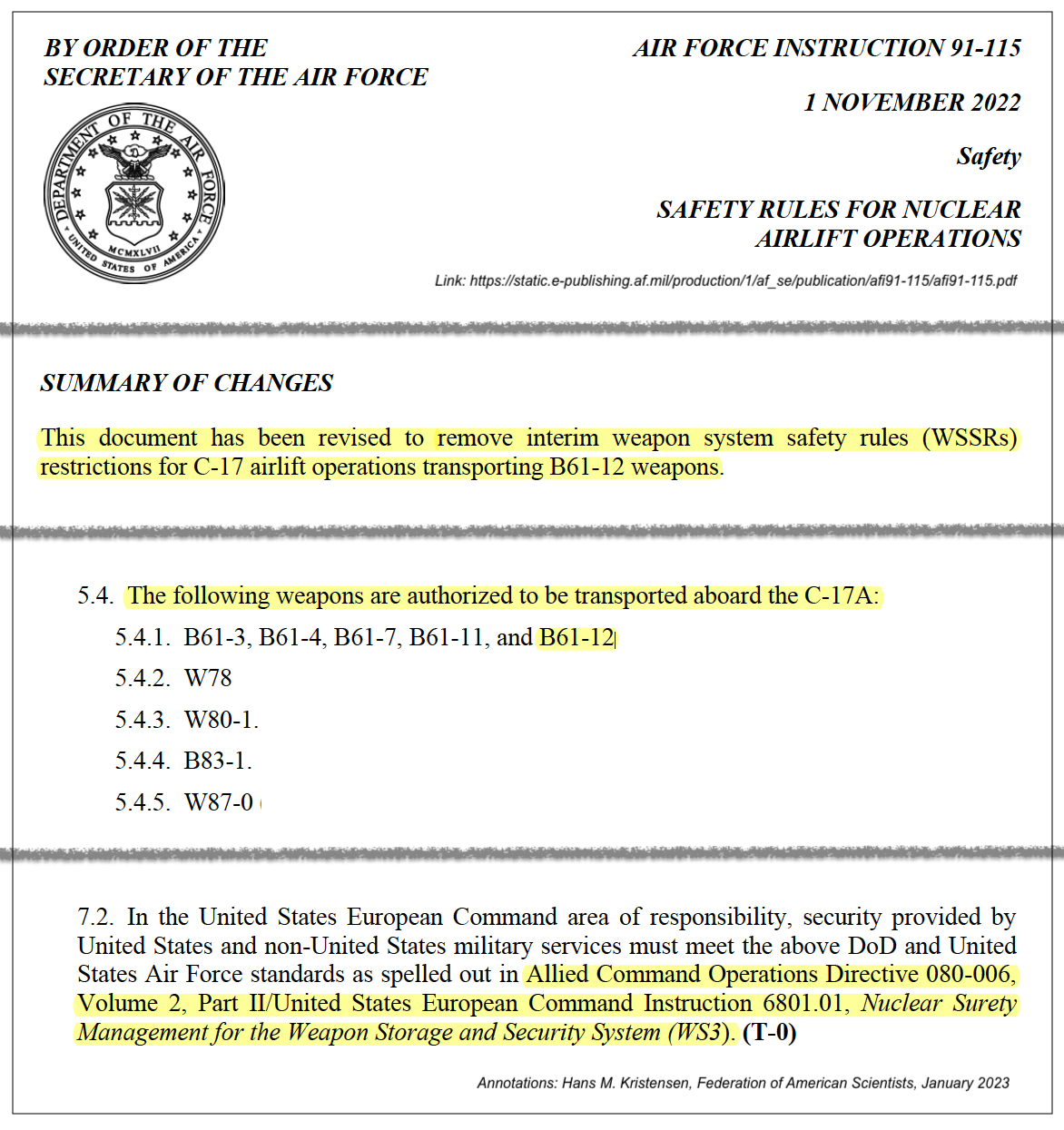

Although nuclear detonation from an accident is unlikely, detonation of the chemical high explosives in the weapon would likely scatter plutonium and other radioactive materials. An accident inside a vault or shelter potentially would have local effect, while pollution from the crash of a C-17A cargo aircraft carrying several weapons could be a lot more extensive. A picture published by the Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2020 indicates that a single C-17A can carry at least 30 B61 nuclear bombs (see image below). That means that all the 10-15 B61 bombs estimated to be stored at Volkel Air Base could be moved in just one flight.

Background information:

FAS Nuclear Notebook: US Nuclear weapons, 2023

NATO Steadfast Noon Exercise and Nuclear Modernization in Europe

The C-17A Has Been Cleared To Transport B61-12 Nuclear Bomb To Europe

Lakenheath Air Base Added To Nuclear Weapons Storage Site Upgrades

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

STRATCOM Says China Has More ICBM Launchers Than The United States – We Have Questions

In early-February 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) had informed Congress that China now has more launchers for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) than the United States. The report is the latest in a serious of revelations over the past four years about China’s growing nuclear weapons arsenal and the deepening strategic competition between the world’s nuclear weapon states. It is important to monitor China’s developments to understand what it means for Chinese nuclear strategy and intensions, but it is also important to avoid overreactions and exaggerations.

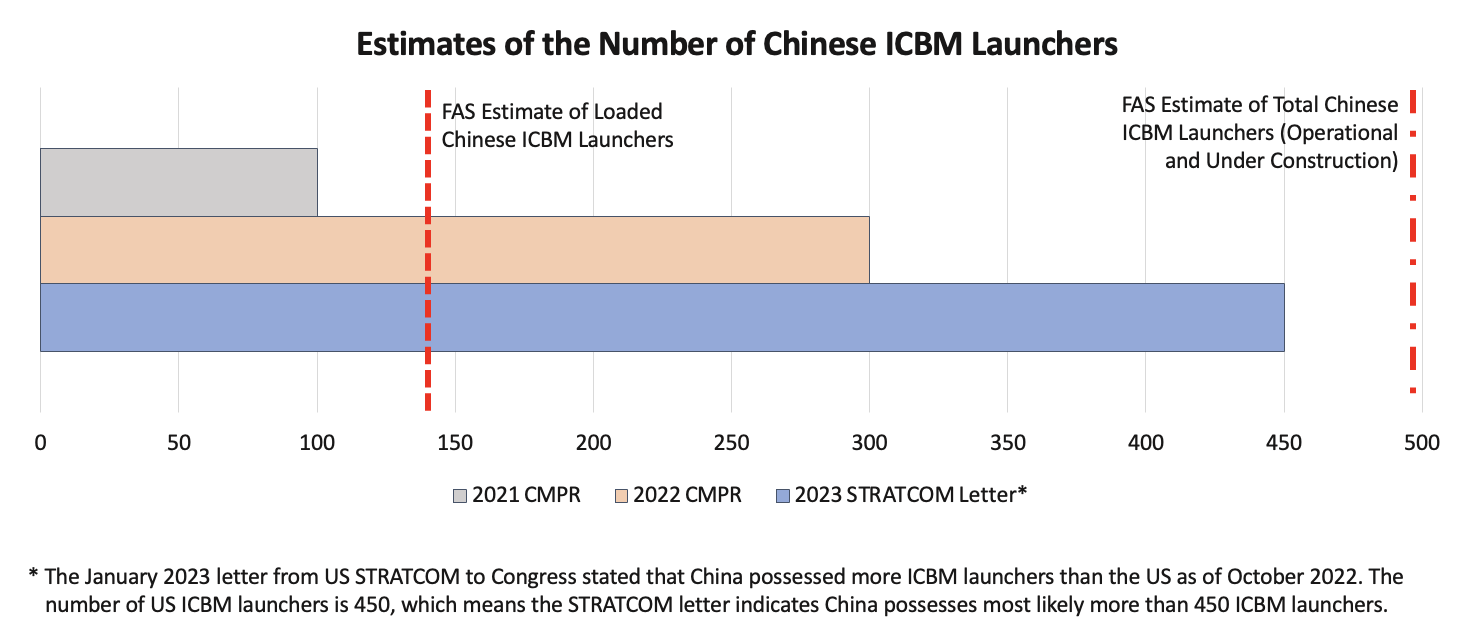

First, a reminder about what the STRATCOM letter says and does not say. It does not say that China has more ICBMs or warheads on them than the United States, or that the United States is at an overall disadvantage. The letter has three findings (in that order):

- The number of ICBMs in the active inventory of China has not exceeded the number of ICBMs in the active inventory of the United States.

- The number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of China has not exceeded the number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of the United States.

- The number of land-based fixed and mobile ICBM launchers in China exceeds the number of ICBM launchers in the United States.

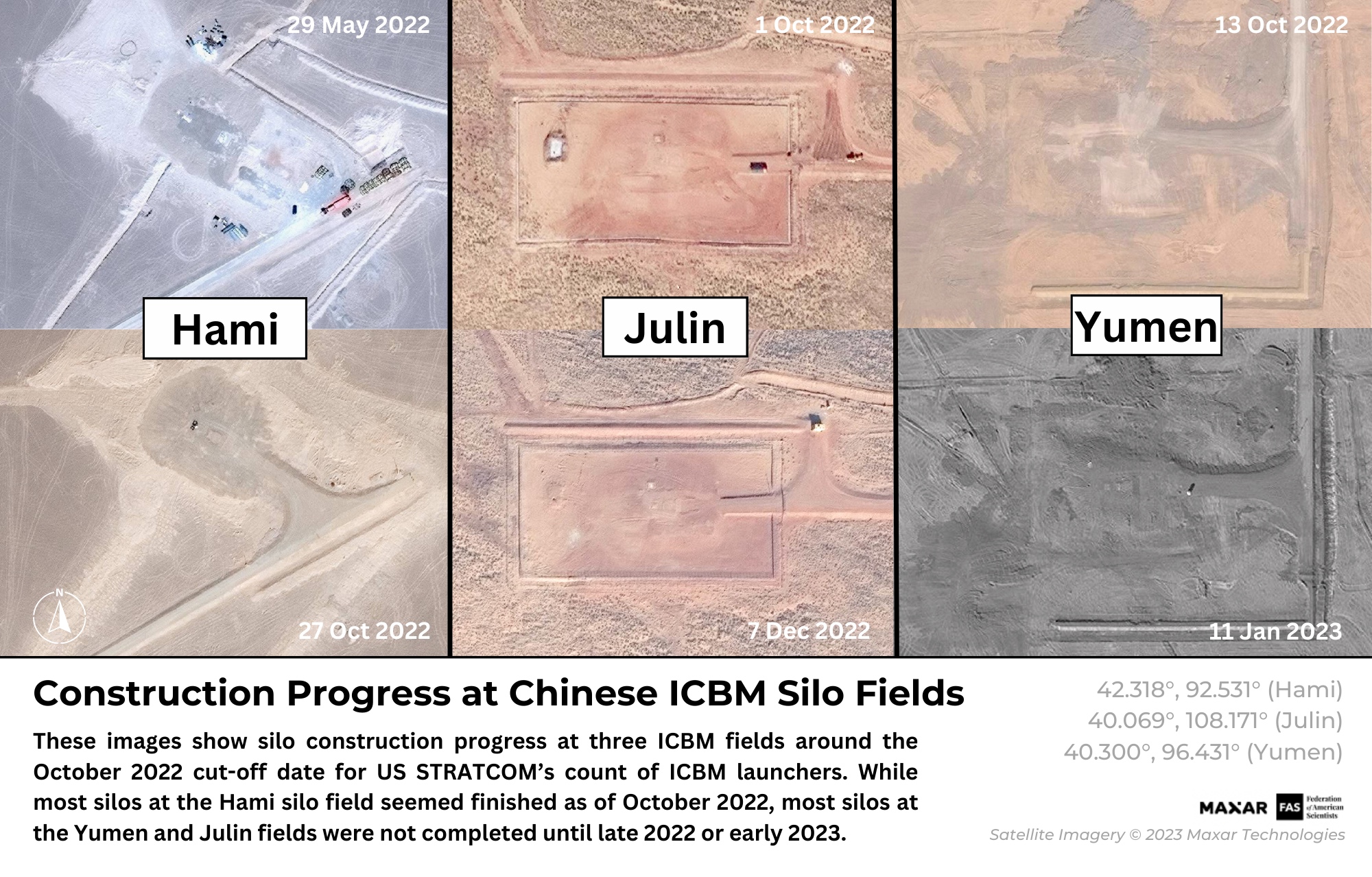

It is already well-known that China is building several hundred new missile silos. We documented many of them (see here, here and here), as did other analysts (here and here). It was expected that sooner or later some of them would be completed and bring China’s total number of ICBM launchers (silo and road-mobile) above the number of US ICBM launchers. That is what STRATCOM says has now happened.

STRATCOM ICBM Counting

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers included in the STRATCOM report to Congress was counted at a cut-off date of October 2022. It is unclear precisely how STRATCOM counts the Chinese silos, but the number appears to include hundreds of silos that were not yet operational with missiles at the time. So, at what point in its construction process did STRATCOM include a silo as part of the count? Does it have to be completely finished with everything ready except a loaded missile?

We have examined satellite photos of every single silo under construction in the three new large missile silo fields (Hami, Julin, and Yumen). It is impossible to determine with certainty from a satellite photo if a silo is completely finished, much less whether it is loaded with a missile. However, the available images indicate it is possible that most of the silos at Hami might have been complete by October 2022, that many of the silos at the Yumen field were still under construction, and that none of the silos at the Julin (Ordos) fields had been completed at the time of STRATCOM’s cutoff date (see image below).

Commercial satellite images help assess STRATCOM claim about China’s missile silos.

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers reported by the Pentagon over the past three years has increased significantly from 100 launchers at the end of 2020, to 300 launchers at the end of 2021, to now more than 450 launchers as of October 2022. That is an increase of 350 launchers in only three years.

To exceed the number of US ICBM launchers as most recently reported by STRATCOM, China would have to have more than 450 launchers (mobile and silo) – the US Air Force has 400 silos with missiles and another 50 empty silos that could be loaded as well if necessary. Without counting the new silos under construction, we estimate that China has approximately 140 operational ICBM launchers with as many missiles. To get to 300 launchers with as many missiles, as the 2022 China Military Power Report (CMPR) estimated, the Pentagon would have to include about 160 launchers from the new silo fields – half of all the silos – as not only finished but with missiles loaded in them. We have not yet seen a missile loading – training or otherwise – on any of the satellite photos. To reach 450 launchers as of October 2022, STRATCOM would have to count nearly all the silos in the three new missile silo fields (see graph below).

Pentagon estimates of Chinese completed ICBM launchers appear to include hundreds of new silos at three missile silo fields.

The point at which a silo is loaded with a missile depends not only on the silo itself but also on the operational status of support facilities, command and control systems, and security perimeters. Construction of that infrastructure is still ongoing at all the three missile silo fields.

It is also possible that the number of launchers and missiles in the Pentagon estimate is less directly linked. The number could potentially refer to the number of missiles for operational launchers plus missiles produced for launchers that have been more or less completed but not yet loaded with missiles.

All of that to underscore that there is considerable uncertainty about the operational status of the Chinese ICBM force.

However – in time for the Congressional debate on the FY2024 defense budget – some appear to be using the STRATCOM letter to suggest the United States also needs to increase its nuclear arsenal.

Comparing The Full Arsenals

The rapid increase of the Chinese ICBM force is important and unprecedented. Yet, it is also crucial to keep things in perspective. In his response to the STRATCOM letter, Rep. Mike Rogers – the new conservative chairman of the House Armed Services Committee – claimed that China is “rapidly approaching parity with the United States” in nuclear forces. That is not accurate.

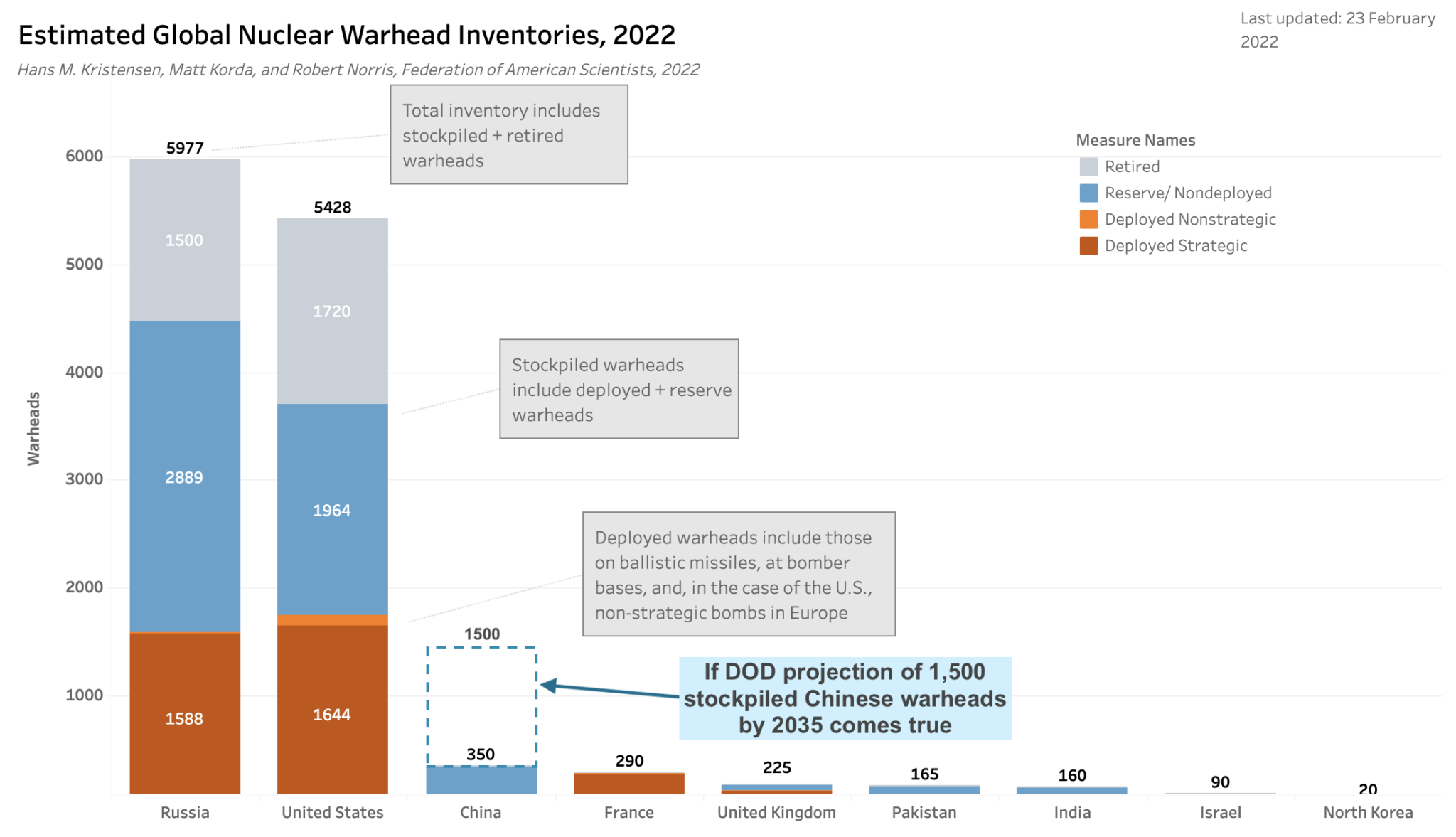

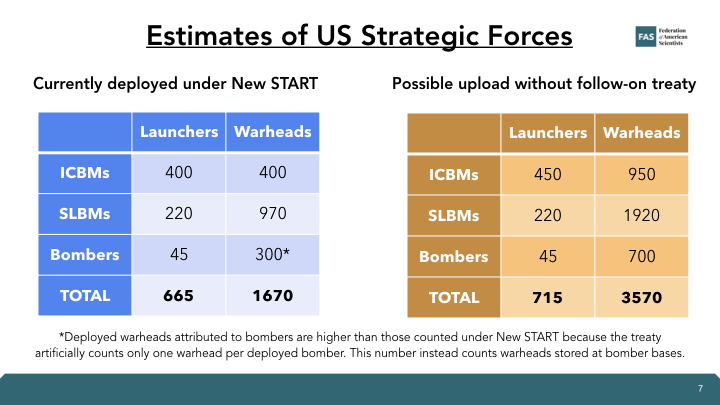

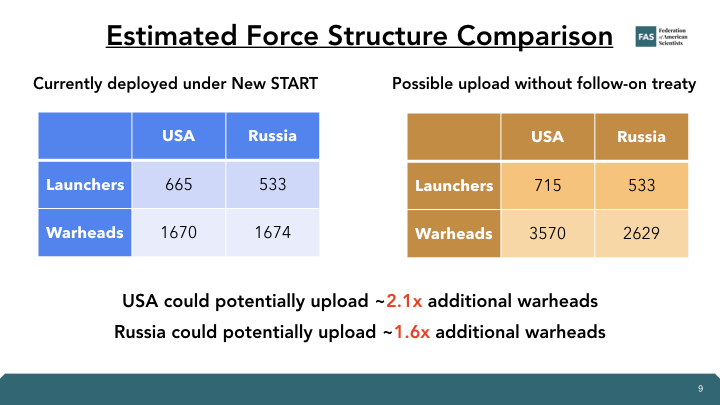

Even if China ends up with more ICBMs than the United States and increases its nuclear stockpile to 1,500 warheads by 2035, as projected by the Pentagon, that does not give China parity. The United States has 800 launchers for strategic nuclear weapons and a stockpile of 3,700 warheads (see graph below).

Even if China increases it nuclear weapons stockpile to 1,500 by 2035, it will only make up a fraction of the much larger US and Russian stockpiles.

The worst-case projection about China’s nuclear expansion assumes that it will fill everything with missiles with multiple warheads. In reality, it is unknown how many of the new silos will be filled with missiles, how many warheads each missile will carry, and how many warheads China can actually produce over the next decade.

The nuclear arsenals do not exist in a vacuum but are linked to the overall military capabilities and the policies and strategies of the owners.

The Political Dimension

STRATCOM initially informed Congress about its assessment that the number of Chinese ICBM launchers exceeded that of the United States back in November 2022. But the letter was classified, so four conservative members of the Senate and House armed services committees reminded STRATCOM that it was required to also release an unclassified version. They then used the unclassified letter to argue for more nuclear weapons stating (see screen shot of Committee web page below):

“We have no time to waste in adjusting our nuclear force posture to deter both Russia and China. This will have to mean higher numbers and new capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Lawmakers immediately used STRATCOM assessment of Chinese ICBM launchers to call for more US nuclear weapons.

Although defense contractors probably would be happy about that response, it is less clear why ‘higher numbers’ are necessary for US nuclear strategy. Increasing US nuclear weapons could in fact end up worsening the problem by causing China and Russia to increase their arsenals even further. And as we have already seen, that would likely cause a heightened demand for more US nuclear weapons.

We have seen this playbook before during the Cold War nuclear arms race. Only this time, it’s not just between the United States and the Soviet Union, but with Russia and a growing China.

Even before China will reach the force levels projected by the Pentagon, the last remaining arms control treaty with Russia – the New START Treaty – will expire in February 2026. Without a follow-on agreement, Russia could potentially double the number of warheads it deploys on its strategic launchers.

Even if the defense hawks in Congress have their way, the United States does not seem to be in a position to compete in a nuclear arms race with both Russia and China. The modernization program is already overwhelmed with little room for expansion, and the warhead production capacity will not be able to produce large numbers of additional nuclear weapons for the foreseeable future.

What the Chinese nuclear buildup means for Chinese nuclear policy and how the United States should respond to it (as well as to Russia) is much more complicated and important to address than a rush to get more nuclear weapons. It would be more constructive for the United States to focus on engaging with Russia and China on nuclear risk reduction and arms control rather than engage in a build-up of its nuclear forces.

Additional Information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

On January 31st, the State Department issued its annual Report to Congress on the Implementation of the New START Treaty, with a notable––yet unsurprising––conclusion:

“Based on the information available as of December 31, 2022, the United States cannot certify the Russian Federation to be in compliance with the terms of the New START Treaty.”

This finding was not unexpected. In August 2022, in response to a US treaty notification expressing an intent to conduct an inspection, Russia invoked an infrequently used treaty clause “temporarily exempting” all of its facilities from inspection. At the time, Russia attempted to justify its actions by citing “incomplete” work regarding Covid-19 inspection protocols and perceived “unilateral advantages” created by US sanctions; however, the State Department’s report assesses that this is “false:”

“Contrary to Russia’s claim that Russian inspectors cannot travel to the United States to conduct inspections, Russian inspectors can in fact travel to the United States via commercial flights or authorized inspection airplanes. There are no impediments arising from U.S. sanctions that would prevent Russia’s full exercise of its inspection rights under the Treaty. The United States has been extremely clear with the Russian Federation on this point.”

Instead, the report suggests that the primary reason for suspending inspections “centered on Russian grievances regarding U.S. and other countries’ measures imposed on Russia in response to its unprovoked, full-scale invasion of Ukraine.”

Echoing the findings of the report, on February 1st, Cara Abercrombie, deputy assistant to the president and coordinator for defense policy and arms control for the White House National Security Council, stated in a briefing at the Arms Control Association that the United States had done everything in its power to remove pandemic- and sanctions-related limitations for Russian inspectors, and that “[t]here are absolutely no barriers, as far as we’re concerned, to facilitating Russian inspections.”

Nonetheless, Russia has still not rescinded its exemption and also indefinitely postponed a scheduled meeting of the Bilateral Consultative Commission in November. In a similar vein, this is believed to be tied to US support for Ukraine, as indicated by Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov who said that arms control “has been held hostage by the U.S. line of inflicting strategic defeat on Russia,” and that Russia was “ready for such a scenario” if New START expired without a replacement.

These two actions, according to the United States, constitute a state of “noncompliance” with specific clauses of New START. It is crucial to note, however, the distinction between findings of “noncompliance” (serious, yet informal assessments, often with a clear path to reestablishing compliance), “violation” (requiring a formal determination), and “material breach” (where a violation rises to the level of contravening the object or purpose of the treaty).

It is also important to note that the United States’ findings of Russian noncompliance are not related to the actual number of deployed Russian warheads and launchers. While the report notes that the lack of inspections means that “the United States has less confidence in the accuracy of Russia’s declarations,” the report is careful to note that “While this is a serious concern, it is not a determination of noncompliance.” The report also assesses that “Russia was likely under the New START warhead limit at the end of 2022” and that Russia’s noncompliance does not threaten the national security interests of the United States.

The high stakes of failure: worst-case force projections after New START’s expiry

Both the US and Russia have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither country will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. Without a deal after 2026, that assumption immediately disappears; both sides would likely default to mutual distrust amid fewer verifiable data points, and our discourse would be dominated by worst case thinking about how both countries’ arsenals would grow in the future.

For an example of this kind of thinking, look no further than the new Chair of the House Armed Services Committee, who argued in response to the State Department’s findings of Russian noncompliance that “The Joint Staff needs to assume Russia has or will be breaching New START caps.” As previously mentioned, the State Department report explicitly states that they have only found Russia to be noncompliant on facilitating inspections and BCC meetings, not on deployed warheads and launchers.

It is clear that the longer that these compliance issues persist, the more they will ultimately hinder US-Russia negotiations over a follow-on treaty, which is necessary in order to continue the bilateral strategic arms control regime beyond New START’s expiry in February 2026. As Amb. Steve Pifer, non-resident Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution, noted during the ACA webinar, “We have three years until New START expires. That seems like a lot of time, but it’s not a long of time if you’re going to try to do something ambitious.”

To that end, both sides should be clear-eyed about the stakes, and more specifically, about what happens if they fail to secure a new deal limiting strategic offensive arms.

The United States has a significant upload capacity on its strategic nuclear forces, where it can bring extra warheads out of storage and add them to the deployed missiles and bombers. Although all 400 deployed US ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that is capable of carrying up to three warheads each. Moreover, the United States has an additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos which could be reloaded with missiles if necessary. With these potential additions in mind, the US ICBM force could potentially more than double from 400 to 950 warheads.

In the absence of treaty limitations, the United States could also upload each of its deployed Trident SLBMs with a full complement of eight warheads, rather than the current average of four to five. Factoring in the small numbers of submarines that are assumed to be out for maintenance at any given time, then the United States could approximately double the number of warheads deployed on its SLBMs, to roughly 1,920. The United States could potentially also reactivate the four launch tubes on each submarine that it deactivated to meet the New START limit, thus adding 56 missiles with 448 warheads to the fleet. However, this possibility is not reflected in the table because it is unlikely that the United States would choose to reconstitute the additional four launch tubes on each submarine given their imminent replacement with the next-generation Columbia-class.

Either of these actions would likely take months to complete, particularly given the complexities involved with uploading additional warheads on ICBMs. Moreover, ballistic missile submarines would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to be uploaded with additional warheads. However, deploying additional warheads to US bomber bases could be done very quickly, and the United States could potentially upload nearly 700 cruise missiles and bombs on its B-52 and B-2 bombers.

[Note: These numbers are projections based off of estimates; they are not predictions or endorsements. They also do not take into account how the number of available launchers and warheads will change when ongoing modernization programs are eventually completed, as this is unlikely to occur before New START’s expiry in 2026]

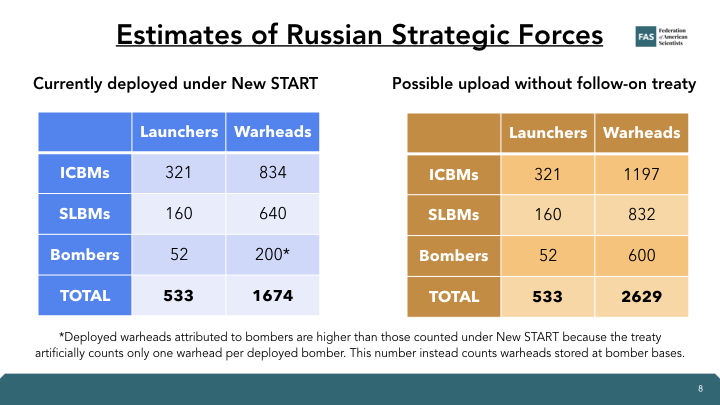

Russia also has a significant upload capacity, especially for its ICBMs. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities, in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase from approximately 834 warheads to roughly 1,197 warheads.

Warheads on submarine-launched ballistic missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without these limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased from an estimated 640 to approximately 832 (also with a small number of SSBNs assumed to be out for maintenance). As in the US case, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons. The number is highly uncertain but assuming approximately 50 bombers are operational, the number of warheads could potentially be increased to nearly 600.

Slide showing estimates of Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

Combined, if both countries uploaded their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals would approximately double in size. The United States would have more deployable strategic warheads but Russia would still have a larger total arsenal of operational nuclear weapons, given its sizable stockpile of nonstrategic nuclear warheads which are not treaty-accountable.

Slide showing comparison estimates of US and Russian strategic forces, as well as a projection showing the possible upload without a follow-on treaty. Numbers mirror those found in the article text.

Moreover, there are expected consequences beyond the offensive strategic nuclear forces that New START regulates. If the verification regime and data exchanges elapse, both countries are likely to enhance their intelligence capabilities to make up for the uncertainty regarding the other side’s nuclear forces. Both countries are also likely to invest more into what they perceive will increase their overall military capabilities, such as conventional missile forces, nonstrategic nuclear forces, and missile defense.

These moves could trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, some of whom might also decide to increase their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. In particular, it is becoming increasingly clear that China appears to no longer be satisfied with just a couple hundred nuclear weapons to ensure its security, and in a shift from longstanding doctrine, may now be looking to size its own nuclear force closer to the size of the US and Russian deployed nuclear forces.

Some US former defense officials have suggested that the United States needs to increase its deployed nuclear force to compensate for the increased nuclear arsenal that China is already building and an alleged increase in Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons––either by negotiating a higher treaty limit with Russia or withdrawing from the New START treaty.

But doing so would not solve the problem and could put the United States on a path where it would in fact face even greater numbers of Russian and Chinese nuclear weapons in the future. A higher treaty warhead limit would obviously increase – not reduce – the number of Russian warheads aimed at the United States; and pulling out of New START would likely cause Russia to deploy even more weapons. Moreover, a significant increase in the size of US and Russian deployed nuclear forces could cause China to increase its arsenal even further. Such developments could subsequently have ripple effects for India, Pakistan, and elsewhere – developments that would undermine, rather than improve, US and international security.

Uploading more warheads is not necessary to maintain deterrence

It is important to note that even if such worst-case scenarios were to occur, in the past the Department of Defense and the Director of National Intelligence have assessed that even a significant Russian increase of deployed nuclear warheads would not have a deleterious effect on US deterrence capabilities. A 2012 joint study assessed: