A Response to Congresswoman Tauscher’s Article in Nonproliferation Review

A recent article, “Achieving Nuclear Balance”, in Nonproliferation Review, by Congresswoman Ellen Tauscher, Chairwoman of the Strategic Forces Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, includes a sobering summary of the dangerous nuclear policies of the Bush administration, including its desire for new nuclear weapons and an expansion of the roles of nuclear weapons. Congresswoman Tauscher has been an important voice of reason in the nuclear debate and one of the primary forces behind efforts to force a fundamental review of the missions of nuclear weapons, to ask what nuclear weapons are for.

Nevertheless, her arguments in support of exploring the Reliable Replacement Warhead are mistaken and based on deeply rooted but ultimately unsupported assumptions. Her essay highlights the critical importance of carefully defining terms and avoiding being fooled by our own euphemisms.

(more…)

A Closer Look at China’s New SSBNs

By Hans M. Kristensen

The two new Jin-class SSBNs I discovered on Google Earth earlier this month have now been photographed in port by an anonymous photographer. The photograph, which has appeared on several Chinese web sites (here and here) and sent to me by David, clearly shows the features of what I estimated to be the Jin-class submarine.

Nothing is known about who took this photograph or whether or not it has been digitally manipulated. But if it is authentic, it appears to lay to rest speculations that the Jin-class would carry 16 missiles. Instead the photograph confirms the assessment made by the U.S. intelligence community by clearly showing the wide-open hatches of 12 launch tubes.

The photograph shows the submarines at an angle, which makes it difficult to precisely measure the length of the various sections. Furthermore, he second submarine on the other side of the pier is obscured by the submarine closest to the camera, making comparison of the two impossible. Yet, a comparison made from the satellite images on my previous blog show that the two submarines have the same overall dimensions.

The new photograph shows the sail of both submarines, which appear to be very similar. Moreover, the front submarine shows a unique feature on the top of the rudder section, which may be a sensor of some kind.

Overall, it is not as if the Chinese are trying to hide anything. Indeed, it is almost as if they want to show what they’ve got.

Background: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning

Reliable Replacement Warhead Is a Symptom, Not the Solution

Last week, the Jasons, a group of distinguished scientists who advise the Department of Defense, released the unclassified summary of their review of the Reliable Replacement Warhead, or RRW. Walter Pincus covered the report in the Washington Post. The summary is posted on the FAS website.

Although almost everything about nuclear weapons and their design is classified, the unclassified summary contains many hints of problems with the RRW that are yet to be overcome.

(more…)

Two More Chinese SSBNs Spotted

|

|

China appears to have launched two more SSBNs. |

By Hans M. Kristensen (BLOG UPDATED OCTOBER 10, 2007)

China appears to have launched two more ballistic missiles submarines from the Bohai shipyard at Huludao approximately 400 km east of Beijing. This could bring to three the number of Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) launched by China in the past three to four years.

The two submarines were discovered during analysis of newly published commercial satellite images on Google Earth. This is the second time in three months that FAS has discovered new Chinese ballistic missile submarines on commercial satellite images. The first time was in July 2007, when the first Jin-class was disclosed on the FAS Strategic Security Blog.

The submarines on the new image have the same dimensions as the previous submarine.

So How Many Do They Have?

Whether China has now launched two or three Jin-class SSBNs is still unclear. The image of the first SSBN discovered at Xiaopingdao in July 2007 was taken on October 17, 2006. The new image of the two SSBNs at Huludao was taken six and a half months later on May 3, 2007. One possibility is that the Xiaopingdao SSBN returned to Huludao for repair or further adjustment and was captured on the 2007 photo together with the second SSBN. Another possibility is that the two Huludao SSBNs are indeed the second and third boats of the new Jin-class SSBN.

The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence estimated in December 2006 that “a fleet of probably five TYPE 094 SSBNs will be built in order to provide more redundancy and capacity for a near-continuous at-sea SSBN presence.” China has not stated how many SSBNs it plans to build and there is no authoritative information available in the public that confirms that China plans to build five SSBNs. It might, but it might also build less if it decides that three or four are sufficient.

Some Implications

The new Jin-class SSBNs add to the single and unsuccessful Xia-class (Type 092) that China launched in 1982. The Xia has never conducted a deterrent patrol and its operational status is in doubt. The rapid launch of two or three Jin-class SSBNs indicate that the Chinese navy feels confident it has overcome at least some of the technical problems that curtailed the Xia.

|

|

|

|

Comparison of Chinese SSBNs discovered on commercial satellite images made available on Google Earth since 2005 show clear differences between the Xia-class (Type-092) and the new Jin-class (Type 094). The roughly 23-meter missile compartment on the Xia (top) has been extended to about 34 meters on the Jin-class. The Jin-class photographed at Xiaopingdao (second from top) and the two at Huludao have the same dimensions, indicating that China has launched at least two boats. To download larger image, click on the image above or here. |

Each Jin-class appears to have 12 launch tubes for the new Julang-2 sea-launched ballistic missiles that are currently under development. If Julang-2 and three Jin-class SSBNs become fully operational, it would enable China to deploy up to 24 ballistic missiles at sea, assuming one boat would be in overhaul at any given time (and the Xia is still not operational). The range of the Julang-2 is estimated by the US intelligence community at more than 8,000 km (4,970+ miles), which brings Hawaii and Alaska (but not the continental United States) within reach from Chinese territorial waters.

Despite many rumors on the Internet about multiple warheads on Julang-2, the long-held assessment by the US intelligence community is that the Julang-2 will be a single-warhead missile.

Whether China plans to deploy a continuous sea-based deterrent is unknown. It appears doubtful because it would break with the Chinese practice of not deploying fully operational nuclear missiles. Nuclear warheads for China’s land-based missiles are believed to be stored separate from the missiles, although this has never actually been verified for the entire force. If the submarines deployed into the Pacific (like U.S. and to a smaller extent Russian SSBNs) it would also break with Chinese policy of not deploying nuclear weapons outside Chinese territory. An alternative would be to operate the SSBNs as a surge capability, intended to deploy in a crisis.

Background: Other Blogs About China

Flying Nuclear Bombs

|

|

The Air Force is reported to have loaded and flown five (some say six) nuclear-armed Advanced Cruise Missiles on a B-52H bomber – by mistake. This image shows a B-52H will a full load of 12 Advanced Cruise Missiles under the wings. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Michael Hoffman reports in Military Times that five (some say six) nuclear-armed Advanced Cruise Missiles were mistakenly flown on a B-52H bomber from Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota to Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana on August 30.

I disclosed in March that the Air Force had decided to retire the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM), and the Minot incident apparently was part of the dismantlement process of the weapon system.

| Update September 23, 2007: Contributed information to story in the Washington Post.Update September 6, 2007: The Air Force has issued a statement on the B-52 incident. |

Managing Nuclear Weapons Custody

Beyond the safety issue of transporting nuclear weapons in the air, the most important implication of the Minot incident is the apparent break-down of nuclear command and control for the custody of the nuclear weapons. Pilots (or anyone else) are not supposed to just fly off with nuclear bombs, and base commanders are not supposed to tell them to do so unless so ordered by higher command. In the best of circumstances the system worked, and someone “upstairs” actually authorized the transport of nuclear cruise missiles on a B-52H bomber.

To keep track of the thousands of nuclear weapons in the U.S. nuclear stockpile, the Department of Defense and Department of Energy use several Automated Information Systems (AISs) to provide automated assistance in stockpile management, stockpile database support, in processing nuclear weapons reports and controlling weapons movements, and in coordinating materiel management for DOE spare parts:

* Defense Integration and Management of Nuclear Data Services (DIAMONDS). Automated tool that, together with the Nuclear Management Information System (NUMIS), enables users to maintain, report, track and highlight trends affecting the nuclear weapon stockpile activities ensuring continued sustainability and viability of the nuclear stockpile. Installation of DIAMONDS at Navy sites was completed in December 2006.

* Nuclear Management Information System (NUMIS). NUMIS is the official AIS of record for maintaining the National Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Databases, and is used to maintain current data on the U.S. nuclear stockpile in the custody of DOD and DOE.

* Nuclear Weapons Contingency Operations Module (NWCOM). NWCOM is a database system that provides current summarized information on all nuclear weapons. NWCOM has the capability to operate independently from the NUMIS architecture, giving users a nuclear weapons tracking system capable of wartime operations. Once fully segmented and integrated into the Global Command and Control System-Top Secret (GCCS-T), NWCOM will begin its integration into the DOD (DISA/STRATCOM) Nuclear Planning and Execution System (NPES).

* Special Weapons Information Management (SWIM) system. SWIM is a PC-based system that provides worldwide nuclear custodial units the capability to automate weapons status reports and local stockpile management tasks.

|

|

|

|

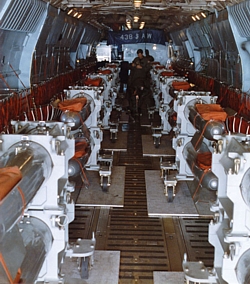

Twenty-four B61 nuclear bombs lined up in the cargo hull of a C-124 cargo aircraft of the 438th Airlift Wing. Since this Air Force picture was taken, the C-124 has been retired and its mission of nuclear weapons transporter taken over by the C-17. |

A Brief History of Nukes in the Air

The last time the Air Force is known to have flown nuclear weapons on a bomber was during the so-called Chrome Dome missions in the 1960s when the Air Force maintained a dozen bombers loaded with nuclear weapons in the air at any time. The program, formally known as the Airborne Alert Program, lasted between July 1961 and January 1968. The program ended abruptly on January 21, 1968, when a B-52 carrying four B28 thermonuclear bombs crashed on the ice off Thule Air Base in Greenland during an emergency landing. The accident followed another crash in Spain in 1966 and several other nuclear incidents.

Between 1968 and 1991, Air Force bombers continued to be loaded with nuclear weapons and stand alert at the end of runways on bases across the country, but flying them was not allowed due to safety concerns. The ground alert ended in September 1991 when the bombers were taken off nuclear alert as part of the first Bush administration’s Presidential Nuclear Initiative.

Although nuclear weapons are not flown on combat aircraft under normal circumstances, they are routinely flown on selected C-17 and C-130 transport aircraft, which as the Primary Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) are used to airlift Air Force nuclear warheads between operational bases and central service and storage facilities in the United States and in Europe (see overview here).

Trimming the Cruise Missile Inventory

The ACM transport from Minot Air Force Base is part of the Air Force’s transition to a slimmer nuclear cruise missile force. By 2012, the current inventory of 1,800 nuclear cruise missiles will be trimmed to 528. The transition will completely retire 400 ACMs and scrap about 870 Air Launch Cruise Missiles (ALCMs). Under the plan, the 2nd Bomb Wing at Barksdale Air Force Base will no longer have a nuclear cruise missile capability, and all of the remaining 528 ALCMs will be based at Minot Air Force Base.

| Read also the comments section:

“If the B-52 incident tells us that the military’s command and control system cannot ensure with 100% certainty which weapons are nuclear and which ones are not, imagine the implications of the wrong weapon being used in a crisis or war. ‘Sorry Mr. President, we thought it was conventional.'” …and my comment on Google News. |

Background: USAF statement | U.S. Air Force Decides to Retire Advanced Cruise Missile | U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Today and Tomorrow

Article: U.S. Nuclear Stockpile Today and Tomorrow

|

|

The latest FAS-NRDC estimate of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

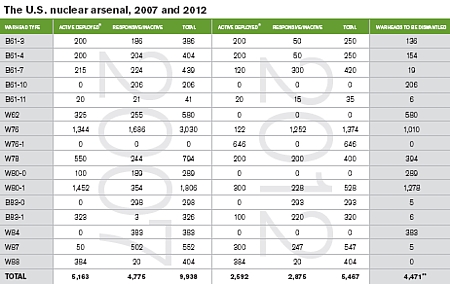

The U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile currently contains an estimated 9,900 nuclear warheads of 15 different versions of nine basic types, according to the latest FAS-NRDC Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. By 2012, approximately 4,470 of the warheads will have been withdrawn, leaving a stockpile of roughly 5,500 warheads.

The administration insists that the size and breakdown of the stockpile must be kept secret in the interest of national security, but a growing number of lawmakers argue that some stockpile information is not necessary to classify.

The Nuclear Notebook is written by FAS’ Hans M. Kristensen and NRDC’s Robert Norris.

Background: Administration Increases Submarine Warhead Production Plan | Estimates of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile, 2007 and 2012 | U.S. Nuclear Forces, 2007

Through the Indian Looking Glass

In an earlier blog (see below), I discussed how, during the Congressional debate about the US-India nuclear deal, even those members of Congress opposed to the deal bent over backwards to declare their support for closer ties between the world’s two largest democracies. And everyone agreed the deal is generous, opens long-closed doors, and sets minimal and perfectly reasonable expectations of India.

So what are we to make of the brouhaha in New Delhi? According to reports in both the Indian and western press, the US-Indian nuclear deal is being denounced, mostly by the communist and allied parties, as an unacceptable constraint on Indian sovereignty. (I want to thank Leonor Tomero for her extremely helpful India news summary.)

(more…)

Administration Increases Submarine Nuclear Warhead Production Plan

|

|

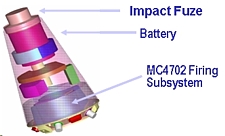

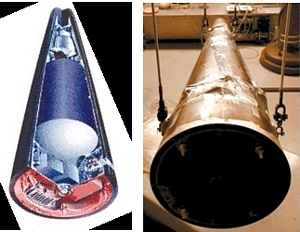

The slim Mk4A reentry body for the W76-1 warhead. The administration plans to produce 2,000 between 2007 and 2021. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Bush administration has decided to more than double the number of nuclear warheads undergoing an expensive upgrade for potential future deployment on the Navy’s 14 ballistic missile submarines, according to answers provided by the National Nuclear Security Administration in response to questions from the Federation of American Scientists.

The decision preempts a debate in Congress about how the United States should size its future nuclear weapons arsenal.

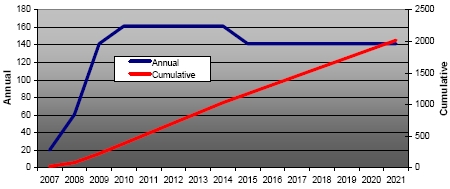

The upgrade concerns the W76, the most numerous warhead in the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile. The Clinton administration decided to upgrade 25 percent, but the Bush administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) in 2001 recommended that significantly more warheads had to be upgraded. An assessment completed by the Department of Defense in 2005 increased the plan to 63 percent of the W76 stockpile, corresponding to an estimated 2,000 warheads.

More than just a refurbished weapon, official sources indicate, the new weapon will have significantly increased military capabilities against hard targets.

Expansion of the W76 Life Extension Program

The W76 Life Extension Program (LEP) was initially approved in March 2000, when the Nuclear Weapons Council approved life-extension of approximately 800 W76s (Block 1). The decision whether to proceed with Block 2 and how many W76s to life-extend in total was deferred. Block 1 completion was initially set for 2012, but in subsequent DOE budget requests the W76 LEP completion date gradually began to slide: 2013 in the FY 2005 request; 2017 in the FY 2006 request; 2020 in the FY 2007 budget request; and most recently 2021 in the FY 2008 request. It was this slide that in May prompted FAS to submit questions to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

The NNSA letter explains that DOD requirements before 2001 called for 25 percent of the W76 stockpile to be life-extended, or approximately 800 of the roughly 3,200 W76 warheads estimated to be in the stockpile at the time. But the Bush administration’s 2001 Nuclear Posture Review “resulted in plans to refurbish a significantly greater quantity.” The NPR was implemented by the March 2003 Nuclear Posture Review Implementation Plan, a 26-page document that instructed government agencies which parts of the NPR they must implement and when. Finally, the “most recent classified [W76 LEP]Selected Acquisition Report estimate is for a planned refurbishment of 63 percent of the stockpile,” according to NNSA.

|

|

|

|

The Bush administration’s plan to life-extend 63 percent of the W76 stockpile requires production of approximately 2,000 W76-1 warheads between 2007 and 2021. Authorization to produce the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW) from 2014 could affect the second half of the plan. |

The 63 percent requirement (roughly 2,000 warheads) contained in the 2007 W76 LEP Selected Acquisition Report was set, the NNSA letter reveals, by the Strategic Capabilities Assessment, a review completed in 2005 in preparation for the Quadrennial Defense Review by the DOD of the assumptions used for the 2001 NPR. The DOD Assessment concluded that “the NPR’s planning assumptions remain valid, although conditions are trending toward − if anything − a more stressing strategic landscape, for example, with respect to North Korea, Iran and nuclear proliferation.”

The W76-1/Mk4A

Approximately 3,250 W76 warheads were produced between 1978 and 1988. The weapons armed the Poseidon C3 and Trident I C4 and currently the Trident II D5 missiles (together with about 400 W88 warheads). A modified W76 also arms Trident II missiles on British submarines. With the service life limit of the oldest units approaching, the Clinton administration in the late 1990s ordered a W76 Life Extension Program (LEP) to extend the service life for another 30 years. Major milestones for the program are:

|

|

|

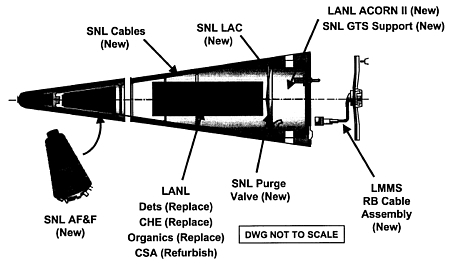

The W76 LEP creates a modified warhead called the W76-1. The cone-shaped Mk4 reentry body designed to protect the warhead against the heat created by the fiery reentry through the earth’s atmosphere will also be modified; the new reentry body is called the Mk4A. The W76 LEP is a major overhaul of the warhead that involves changes to both the reentry body and the warhead package: Replacing “organics” in the primary; replacing detonators; replacing chemical high explosives; refurbishing the secondary; adding a new Arming, Fuzing & Firing (AF&F) system, a new gas reservoir, a new gas transfer support system, a new lightning arrestor connector (LAC) (see Sandia National Laboratories drawing below).

|

|

|

|

The W76 LEP includes significant changes to the both the W76 warhead and the Mk4A reentry body. Guide: AF&F, Arming, Fuzing & Firing; CHE, Chemical High Explosives; CSA, Canned Secondary Assembly; Dets, detonators; GTS, Gas Transfer System; LAC, Lightning Arrestor Connector; LANL, Los Alamos National Laboratory; LMMS, Lockheed Martin Missiles & Space; SNL, Sandia National Laboratories. |

Boosting Hard Target Kill Capability

Government documents and statements by government officials hint that the W76 LEP is quietly creating a weapon with significantly improved military capability over the old version. Whereas the old fuze only permitted targeting of soft targets, the new MC4700 Arming, Fuzing and Firing (AF&F) system gives the W76 hard target kill capability for the first time. The former head of the navy’s Strategic Systems Program, Rear Admiral George P. Nanos, who later became the Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory which designed the W76, explained in an article in The Submarine Review in April 1997 that the “capability for the [existing] Mk4…is not very impressive by today’s standards, largely because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” But “with the accuracy of D5 and Mk4, just by changing the fuse in the Mk4 re-entry body, you get a significant improvement,” Nanos stated. In fact, “the Mk4, with a modified fuze and Trident II accuracy, can meet the original D5 hard target requirement.”

|

|

|

|

The new MC4700 Arming, Fuzing and Firing system developed for the W76-1/Mk4A will enable the warhead to take advantage of the accuracy of the Trident II D5 missile to “meet the original D5 hard target requirement.” |

The added capability is normally not highlighted in official presentations of the W76 LEP. Yet the purpose of developing a new AF&F system on the W76-1/Mk4A, according to the Department of Energy’s 1997 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (excerpt), is to “enable [the] W76 to take advantage of [the] higher accuracy of the D5 missile.”

There are two reasons for increasing the accuracy. First, the previous hard target kill missile – the Peacekeeper ICBM – was withdrawn from operational service in 2005, and the modernized Minuteman III apparently has not been able to achieve the same degree of accuracy. Second, as the number of weapons in the nation’s arsenal is reduced, the ones remaining must be more flexible and capable of holding a wider range of targets than before.

With “advanced fuzing options” the AF&F system will allowing targeteers to set the Height of Burst (HOB) more accurately and significantly improve the ability to hold hard targets at risk. Because 63 percent of the W76 stockpile is being added the new fuze, if Admiral Nanos is correct, the U.S. inventory of reentry vehicles with hard target kill capability will increase from 400 today to 2,400 in 2021.

Sizing the Arsenal

The disclosure of the 63 percent number adds new information about how the administration envisions the structure of the future nuclear arsenal. Under the SORT agreement signed with Russia in 2002, no more than 2,200 strategic warheads may be operationally deployed by 2012. Yet the total stockpile will be significantly larger, about two and a half times, and include an estimated 5,467 warheads.

|

|

|

|

The government has only recently begun to show pictures of the W76 reentry vehicle. Los Alamos National Laboratory has published a drawing of a W76 interior layout (left), and Sandia National Laboratories has published photographs of the Mk4A reentry body (right). |

Under SORT, the Navy plans to deploy up to an estimated 1,150 warheads on 12 ballistic missile submarines (an average of four warheads per missile). Another two submarines will normally be in overhaul. Approximately 750 of the warheads will be W76-1 with the balance made up by the more powerful W88 warheads. Because SORT doesn’t set limits on reserve warheads or regulate how Russia and the United States can distribute their nuclear weapons below the ceiling, most of the planned W76-1 warheads will not be deployed but kept in storage as a “hedge” against a nuclear-armed adversary suddenly increasing its nuclear arsenal. The 63 percent production plan suggests that the administration wants to retain the capability to increase the warhead loading to as much as eight warheads per missile, the same number it deployed during the Cold War. Another reason for retaining spare W76 warheads is to have replacement warheads in case of technical failure of deployed warheads.

The administration has proposed to replace some of the W76s with the Reliable Replacement Warhead (RRW-1) to increase the “diversity” of the type of warheads at sea. If Congress approves RRW-1 production, the second half of the 76-1 production plan would probably be changed to RRW-1 warheads beginning (under current plans) in 2014, in which case the future sea-based posture would be made up of a mix of W76-1, W88 and RRW-1 warheads.

In Congress both the Senate and House have called for a review of U.S. nuclear policy to ensure the right size and role of the nuclear posture. The 63 percent W76-1 production set by the 2005 Strategic Capabilities Assessment would appear to preempt that effort.

Background:

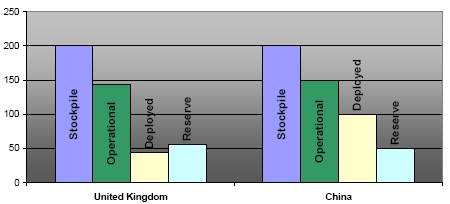

Nuclear Arms Racing in the Post-Cold War Era: Who is the Smallest?

|

|

China and the Uniked Kingdom have started a new arms race over who has the smallest nuclear weapons arsenal. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Mine is smaller! No, mine is smaller!!

China and the United Kingdom have started a new type of nuclear arms race for the honor to have the smallest number of nuclear weapons.

In April 2004, the Chinese Foreign Ministry declared in the fact sheet China: Nuclear Disarmament and Reduction of: “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China…possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.”

In May 2007, British Defense Minister Des Browne stated in a written response to a parliamentary question that the United Kingdom has “the smallest stockpile of any of the nuclear weapon states recognised under the NPT.”

Apparently, the race is on for who is the smallest.

So Who Is The Smallest Nuclear Power?

The size of the nuclear weapons inventory of both countries is secret, but it is possible to make best estimates.

Britain announced in December 2006 that it had reduced the number of “operationally available warheads” from fewer than 200 to “less than 160.” The gesture was somewhat hollow, however, because Britain hasn’t had room for more than 144 warheads on its Trident D5 missiles for years. Moreover, the language hints that Britain has more nuclear warheads in storage. Assuming it retains a small reserve, the total British stockpile is probably around 200 warheads.

The British government has stated that the single SSBN on patrol at any given time carries “up to 48” warheads, a statement that partly reflects that some of the missiles have been given a “substrategic” mission, probably with only one warhead each. Depending on the number of substrategic mission missiles carried, the actual loading of the patrolling submarine probably is 36-44 warheads. Assuming a similar loading for the other two SSBNs for which there are missiles available, the estimated number of warheads needed for the British SSBN fleet since the substrategic mission first became operational in 1996 is 108-132 warheads.

The Chinese government’s statement that it possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal among the nuclear-weapon states is different than the British statement. First, the Chinese statement refers to the “arsenal” rather than stockpile described by the British statement. It is unclear what the Chinese mean by “arsenal” – whether it refers to the entire stockpile or only operational warheads. Second, the statement refers to “the nuclear-weapon states,” rather than the NPT-declared nuclear weapon states (Britain, China, France, Russia, United States), and thus appears to include India and Pakistan as well. Yet elsewhere in the statement, the foreign minister uses the term “nuclear-weapon states” to refer to Britain, China, France, Russia, and the United States. Based on publicly available information and assessments made by the U.S. Intelligence Community, China is estimated to have approximately 150 operational nuclear weapons and a total stockpile of roughly 200 warheads. Only about 100 of these may actually be deployed with the delivery systems, although few (if any) of the warheads are thought to be mated on the weapon.

|

|

|

|

Britain and China both claim to have the lowest number of nuclear weapons of the original five nuclear weapon states. Both refuse to say how many they have. In reality, the two countries are estimated to have about the same total number of nuclear warheads, but the numbers can very considerably depending on which part of the posture is presented. |

The two postures differ significantly. China does not have a permanent deployment of nuclear weapons at sea, and most (if not all) of China’s land-based missiles are thought to be deployed without the nuclear warheads installed. Unlike Britain, moreover, China has a no-first-use policy for its nuclear weapons.

In the future, however, China may have to revisit its statement about its nuclear weapons inventory. Whereas the British stockpile has declined an is unlikely to increase in the future, the Chinese stockpile may be increasing some in the next decade.

Confidence Reaffirmed (Silly Secrecy Too)

The statements made by the two countries have revealed a curious phenomenon: both apparently are confident that they know how many nuclear weapons the other has. Indeed, confidence appears to be so high that both are willing to say so in public.

This is curious because both countries insist that the size of their nuclear stockpiles must be kept a secret, or national security would be jeopardized. But if they both know the size of the other’s arsenal, who are they keeping it secret from?

Background: Britain’s Next Nuclear Era | Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning | British Nuclear Forces, 2005

India Gets a Deal

The much anticipated “deal” between the United States and India for the transfer of nuclear technology and equipment was released over the weekend. It is a sobering read and tells us much about the administration’s thinking. In summary, there isn’t much of a deal here at all, India gets what it wants.

(more…)

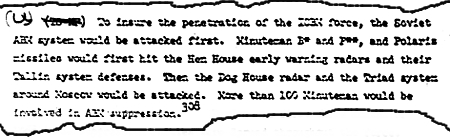

Targeting Missile Defense Systems

By Hans M. Kristensen

The now month-long clash between Russia and the West over U.S. plans to build a missile defense system in Europe should warn us that – despite important progress in some areas – Cold War thinking is alive and well.

The missile defense system, Moscow says, is but the latest step in a gradual military encroachment on Russian borders by NATO, and could well be used to shoot down Russian ballistic missiles. The head of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces and President Putin have suggested that Russia might target the defenses with nuclear weapons. The United States has rejected the complaints insisting that Russia has nothing to fear and that the defenses will only be used against Iranian ballistic missiles. European allies have complained that the Russian threats are unacceptable and have no place in today’s Europe.

That may be true, but the reactions have revealed a frightening degree of naiveté about strategic war planning in the post-Cold War era, a widespread belief that such planning has somehow stopped. It has certainly changed, but all the major nuclear weapon states insist that they must hedge against an uncertain future and continue to adjust their strike plans against potential adversaries that have weapons of mass destruction. Russia continues to plan against the West and the West continues to plan against Russia. The plans are not the same that existed during the Cold War, but they are strike plans nonetheless.

The argument made by some officials that missile defense systems are merely defensive and don’t threaten anyone is disingenuous because it glosses over a fact that all planners know very well: Even limited missile defenses become priority targets if they can disturb other important strike plans. The West concluded that very early on in its military relationship with Russia.

Cold War Targeting of Missile Defense Systems

In 2003, I received a declassified Strategic Air Command document that showed how the United States reacted when the Soviet Union built a limited missile defense system back in the late 1960s. The response was overwhelming: A nuclear strike plan that included more than 100 ICBMs plus an unknown number of SLBMs to overwhelm and destroy the Soviet interceptors and radars. Based on the declassified information, two colleagues and I estimated in an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the total strike plan involved approximately 130 nuclear warheads with a total combined yield of some 115 megatons. Here is how the SAC historian described the plan:

|

|

|

|

“To ensure the penetration of the ICBM force, the Soviet ABM system would be attacked first. Minuteman E and F and Polaris missiles would first hit the Hen House early warning radars, and their Tallin system defenses [SA-5 SAM, ed.]. Then the Dog House radar and the Triad system around Moscow would be attacked. More than 100 Minuteman would be involved in the ABM suppression.” |

The Soviet ABM system back then consisted of about fifteen facilities, including eight launch sites around Moscow with a total of 64 nuclear-tipped interceptors, half a dozen SA-5 launch complexes (later found not to have much ABM capability) near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and at least three large early warning radars. Each of these surface facilities were highly vulnerable to the blast effect from a single nuclear warhead, so the large number of ICBMs was mainly needed to “suppress” (overwhelm) the interceptors.

In the late 1980s, the Soviets upgraded they system by moving 32 remaining interceptors at four sites into underground silos (see Figure 2) and adding 68 shorter-range nuclear-tipped interceptors at five new sites closer to Moscow. This hardened and dispersed the interceptors, requiring U.S. planners to upgrade their strike plan, which probably ballooned to more than 200 warheads (although with less total yield due to more accurate missiles with less powerful warheads).

|

|

|

|

Four long-range Gorgon interceptor site crescent Moscow toward the northwest. The 217-mile (350-kilometer) range Gorgon carries a 1 Megaton warhead. The site shown here is near Poryadino southwest of Moscow. There are unconfirmed rumors that the interceptors have been removed and the system is in the process of decommissioning. |

The 68 shorter-range (50 miles, 80 km) interceptors added to the system in the late 1980s were the nuclear-armed Gazelle. Each missile carried a 10-kiloton warhead. The five launch sites, which are still thought to be operational, are positioned in a circle around Moscow approximately 13 miles (23 kilometers) from the center of the city. The 68 interceptors are deployed in hardened silos, 16 at two sites (Northwest and Southeast), and 12 at each of the other three sites. Public uncertainty about the location of the fifth site was recently resolved by a satellite image showing the site next to the Pill Box radar north of Moscow.

|

|

|

|

Five launch sites with Gazelle interceptors in hardened silos are located in a circle around Moscow as part of the A-135 ABM system. The sites have either 12 silos, like the Southwestern site (top) near Moscow Vnukovo airport, or 16. The fifth site (bottom) next to the Pill Box ABM radar north of Moscow has 12 silos, and is depicted in the Pentagon drawing (insert). |

All of this happened during the Cold War and many things have changed, but the basic motivation for targeting a limited missile defense system then was the same as today: The Soviet ABM system was entirely defensive and couldn’t threaten anyone (to paraphrase a characterization frequently use by U.S. and NATO officials to justify their missile defense plans today), but it could disturb the main ICBM attack on Moscow and military facilities downrange. That made it a top-priority target. And even though U.S. planners suspected that the system was not very efficient, they committed about 10 percent of the entire ICBM force to destroy it. To the extent the Russia ABM is operational, U.S. nuclear strike plans probably still target it today.

|

Figure 4: |

||

|

||

| Type | Designation, Location | Remarks |

| Interceptor | ||

| Gorgon (SH-11/ABM-4)* | – E05, 6 miles (9 km) southwest of Karabanovo, at 56°14’39.51″N, 38°34’41.75″E | |

| – E24, 4 miles (6.5 km) northwest of Poryadino, at 55°20’58.31″N, 36°28’50.28″E | ||

| – E31, 6 miles (9.6 km) north of Nudol Sharino, at 56° 9’0.18″N, 36°30’13.08″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| – E33, east of Klin, at 56°20’30.03″N, 36°47’35.21″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| Gazelle (SH-08/ABM-3) | – South of Ashcherino, at 55°34’40.06″N, 37°46’17.89″E | |

| – 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Kaliningrad, at 55°52’41.63″N, 37°53’37.51″E | ||

| – 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Kartmazovo, at 55°37’31.81″N, 37°23’19.99″E | ||

| – Korostovo, at 55°54’6.00″N, 37°18’28.33″E | ||

| – 6 miles (9.6 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’50.69″N, 37°47’12.01″E | ||

| Radar** | ||

| Pill Box (Don-2N) | – 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’23.48″N, 37°46’12.51″E | |

| To view satellite images of all these sites, click here. * There are unconfirmed rumors that the Gorgon interceptors have been removed from the system. ** Other forward-based early-warning radars are not included in this overview. Two older radars (Dog House and Cat House) are no longer operational. |

||

Now history repeats itself, but the table has been turned. Today it is the United States building a limited missile defense system (more capable than the Soviet system, but focused on “rogue” state missiles), and it is the Russians who say they need to target it to maintain the effectiveness of their deterrent. The Cold War may be over, but military and policy planners in both countries still think in Cold War terms.

Russia’s Real Concerns Today

Most of the current debate has focused on whether the missile defense system could disrupt Russia’s deterrent against the United States. Although this may be a concern to Russian planners in the long run, their objections probably have more to do with the capability of the system to disrupt limited strikes against France or the United Kingdom. Russian nuclear strike plans against each of those smaller nuclear powers probably include only a few ICBMs, but their flight path would take them right over the planned interceptors (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: |

|

|

The Russian objections to the proposed US anti-ballistic missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic seem more linked to potential Russian strike plans against British and French nuclear forces than to strike plans against the United States. The trajectories for a hypothetical ICBM attack against French and British nuclear submarines bases pass over the proposed U.S. missile defense system in Europe. |

Russian planners are probably also thinking ahead. By 2015, under current plans, Russia’s ICBM force is expected to have declined from about 480 missiles today to approximately 150. Significantly less than the 450 the United States plans to retain. This, of course, will have no real implications for Russia’s security, but for Russian planners it means that a European ballistic missile defense system with 10 interceptors (that could quickly be expanded) and 21 interceptors at Fort Greely in Alaska (and silos already dug for more) suddenly doesn’t seem so limited anymore. Indeed, if Russia’s statements about targeting a future missile defense system in Europe are genuine, then the U.S. interceptors in Alaska are probably already targeted by Russian missiles.

Implications

There’s probably a fair amount of chest beating in the Russian statements, especially because Russia has little to gain from antagonistic relations with the West in the long run. Putin’s recent “offer” to include Russian radars in the Western defense plans suggests he is trying to find a way out of the stalemate, although not necessarily the way out that Western governments would like to see.

It would, of course, be much simpler if the Russians “just got over it” and accepted Western missile defenses as a fact of life. But they haven’t, and there are clear signs that U.S. missile defense plans have already influenced Russian military planning. An eerie feeling is emerging in Washington that the Russian “experiment” may be over and that Russia, instead of becoming a full partner or a full enemy, is entering a new assertive period intent on acting as a counterbalance to current U.S. foreign policy. That may not necessarily be a bad thing, unless of course it plays out in the form of military posturing.

Western claims that Russia has nothing to fear, although genuine, miss the point: They apparently fear something enough to publicly use it to underscore their own capability. East and West need to figure out what has gone wrong and how to get out of this mess before strategic antagonism becomes a prominent policy feature for the long haul. The fact that we’re even having this debate nearly two decades after the Cold War ended shows that both countries have failed miserably to move beyond Cold War posturing and planning principles.

Background: The Protection Paradox | Russian Nuclear Forces, 2007 | Pavel Podvig’s Analysis

China Reorganizes Northern Nuclear Missile Launch Sites

|

|

A dozen trucks identified at possible missile launch sites near Delingha in the northern parts of central China resemble the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile launcher. If correct, about a third of China’s DF-21 inventory is deployed within striking distance of Russian ICBM fields. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

China has significantly reorganized facilities believed to be launch sites for nuclear ballistic missiles near Delingha in the northern parts of Central China, according to commercial satellite images analyzed by the Federation of American Scientists.

The images indicate that older liquid-fueled missiles previously thought to have been deployed in the area may have been replaced with newer solid-fueled missiles. From the sites, the missiles are within range of three Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) fields and a bomber base in the southern parts of central Russia.

Analysis of Changes

The Chinese launch sites, which are located at an elevation of approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), are in an area that for years has been rumored to be a deployment area for liquid-fueled DF-4 long-range nuclear ballistic missiles. In November 2006, FAS and NRDC published Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning, which used satellite images to describe the two launch sites. Several other apparent sites nearby did not have any infrastructure and many appeared abandoned.

|

|

|

|

The launch sites are located at approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) on the slopes of this mountain range north of Delingha. This image (used with permission) was shot approximately six miles (10 kilometers) from Delingha. |

The southern launch site has changed most dramatically. In late-2005, the site had what appeared to be a large missile garage, approximately 40 small buildings (possibly crew quarters), and more than half a dozen service trucks. A gate was also visible. In the new image from late-2006, all of those features are gone with only a single service truck visible on the launch pad, and the access road appears to have been paved (see below).

|

|

|

|

The southern launch site at Delingha (37°24’27.47″N, 97° 3’21.18″E) changed dramatically between late-2005 (left) and late-2006. All buildings were been removed and only a few small trucks remain. The 250-feet (80-meters) launch pad and the access roads have been paved. |

The second launch site some 2.5 miles (4.3 km) to the north has also changed significantly, but here operations appear to have increased. In late-2005, this site included what appeared to be a missile garage, an underground facility, approximately 15 buildings, and less than a dozen service trucks of various sizes. The new satellite image from late-2006, however, shows that the large garage has been removed, the number of buildings nearly doubled, the access roads paved, and work appears to be in progress next to the underground facility (see below).

|

|

|

|

The northern primary launch site has been expanded significantly between late-2005 (left) and late-2006. Numerous new buildings have been erected, the access roads have been paved, work appears to be in progress next to the underground facility, and six 13-meter trucks that resemble launchers for the DF-21 MRBM are clearly visible on the launch pad. Check it out on Google Earth. |

Most interestingly, clearly visible are eight 13-meter trucks lined up on the launch pad. The satellite image is not of high enough resolution to identify the trucks and their features with certainty, but they strongly resemble the six-axle transport erector launchers (TELs) in use with the 10-meter DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile. A vague line across the trailer two-thirds toward the rear resembles the position of the hydraulic pumps used to erect the missile canister to a vertical position.

|

|

|

|

Possible DF-21 launchers are also visible at several of a dozen smaller possible launch sites. This one, north of the main site (Site 2), has also been upgraded with a new building. |

Changes to Other Delingha Sites

The two launch sites described above are the most actively visible in the satellite images. But there are more sites that appear to be involved in missile operations. North along the main road is what appears to be five smaller dispersed parking or launch platforms. None of these sites had any vehicles or infrastructure visible in 2005, but the new image shows one 13-meter truck present at four of the five sites. One of the sites appears to be upgrading with new access roads, a building, and half a dozen service vehicles (see right).

Further to the west, approximately 10 miles (17 km) from site 1 and 2, is another road leading north into the mountains. Along this road, another eight possible dispersal launch sites are visible. No 13-meter trucks, buildings, or other vehicles are visible at these sites.

The DF-21 Medium-Range Ballistic Missile

The DF-21 is a medium-range ballistic missile estimated by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) to have a range of approximately 1,330 miles (2,150 kilometers). It is China’s first solid-fueled ballistic missile and believed to carry a single warhead with a yield of 200-300 kilotons. Full operational deployment began in 1991. The missile is approximately 33 feet (10 meters) long and launched from a six-axle transporter erect launcher (TEL). Two versions of the missile are deployed, according to the DOD. Some might have been converted to carry conventional warhead.

|

|

|

|

A DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile during calibration. |

The Defense Intelligence Agency estimated in 1996 that the DF-21 was expected to complement and possibly take over the strategic targeting role of the DF-3 by 2000. But introduction was slow. Whether this is now happening, and whether the DF-21 is also replacing DF-4s in some roles is unknown. The DOD’s annual report on China’s military power for years showed great uncertainty about the number of DF-21s, the 2006 report listing a range of 19-50 missiles on 34-38 launchers. The 2007 report, however, lists 40-50 missiles on 34-38 launchers, which suggests the DOD believes the number of missiles has increased while the number of launchers has stayed the same.

|

|

|

|

From Delingha the DF-21 is in range of northern India (including New Delhi) and three Russian ICBM fields and a bomber base. |

Uncertainties and Implications

It is important to caution that there is no information publicly available that confirms that the Delingha sites are launch sites for ballistic missiles, or that the 13-meter trucks indeed are DF-21 launchers. First, the changes at the sites may be routine because nearly all of China’s ballistic missile are mobile, and the support units are designed to follow the launchers wherever they go. Second, the rumored DF-4 deployment in the area may have been wrong, or the DF-21 may have moved in years ago but only been publicly visible now. U.S. and Russian spy satellites probably have monitored the changes at Delingha on a daily basis and provided a much more detailed understanding of what is happening at the sites.

Yet the indications that the DF-21 is deployed at Delingha appear to be strong. And if the dozen 13-meter trucks visible on the satellite images at Delingha indeed are DF-21 TELs, then 32-35 percent of China’s estimated inventory of DF-21 launchers are deployed in central China.

With a DIA-listed range of 1,330 miles (2,150 kilometers) the DF-21s would not be able to reach any U.S. bases from Delingha, but they would be able to hold at risk all of northern India including New Delhi. Moreover, and this is perhaps the most interesting implication of the discovery, DF-21s would be within range of three main Russian ICBM fields on the other side of Mongolia: the SS-25 fields near Novosibirsk and Irkutsk, the SS-18 field near Uzhur, and a Backfire bomber base at Belaya.

Whereas targeting New Delhi could be considered normal for a non-alert retaliatory posture like China’s, targeting Russian ICBM fields and air bases would be a step further in the direction of a counterforce posture. But again, it is unknown exactly what role the Delingha missiles have, and the DF-21 may not be accurate enough to pose a serious risk to hardened Russian ICBM silos. Regardless of targeting, Delingha appears to be very active.

|

|

|

|

A single B-2 stealth bomber with conventional JDAM bombs would probably be sufficient to incapacitate the Delingha missile launch sites. |

One of the most striking features about the sites is their high vulnerability to attack. All appear to be almost entirely surface-based facilities (although Site 2 has an underground structure), and a mobile missile launcher is extremely vulnerable once it has been discovered. The sites were possible DF-21 launchers were detected are located within a distance of about six miles (10 kilometers). A single high-yield nuclear warhead would probably be sufficient to neutralize the entire force visible in the images.

But an adversary might not even have to cross the nuclear threshold. A single U.S. B-2 bomber loaded with non-nuclear JDAM bombs (see this video) would probably be sufficient to neutralize the dozen launch sites seen in the images. The United States has begun to incorporate such advanced conventional weapons into its strategic strike plans to give the president “more options.” Since China has repeatedly pledged that it “will not be the first to use such [nuclear] weapons at any time and in any circumstance,” some might conclude that a conventional strike on Chinese nuclear forces would not trigger Chinese use of nuclear weapons. But whether Beijing (or anyone else) would indeed stand idle by as its nuclear forces were taken out by conventional weapons is highly questionable.

Background: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning | Delingha on Google Earth