B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

|

| The US military is planning to replace the tail section of the B61 nuclear bomb with a new guided tail kit to increase the accuracy of the weapon. This will increase the targeting capability of the weapon and allow lower-yield strikes against targets that previously required higher-yield weapons. Image: FAS Illustration |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal.

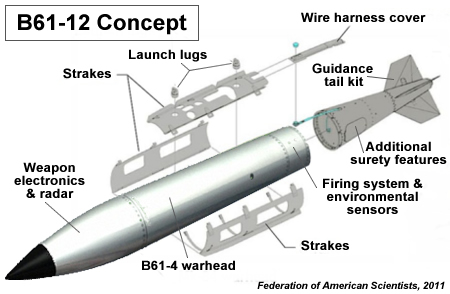

The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy.

As a result, if funded by Congress, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with a significantly enhanced capability to knock out military targets.

Add to that the stealthy capability of the new F-35 aircraft being built to deliver the new weapon, and NATO is up for a significant nuclear upgrade.

The upgrade would also improve the capability of U.S. strategic bombers to destroy targets with lower yield and less radioactive fallout, a scenario that resembles the controversial PLYWD precision low-yield nuclear weapon proposal from the 1990s.

Finally, the B61-12 will mark the end of designated non-strategic nuclear warheads in the U.S. nuclear stockpile, essentially making concern over “disparity” with Russian non-strategic weapons a non-issue.

The Obama administration and Congress should reject plans to increase the accuracy of nuclear weapons and instead focus on maintaining the reliability of existing weapons while reducing their role and numbers.

Increasing Military Capabilities

It is U.S. nuclear policy that nuclear weapons “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.” According to this policy stated in the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), the B61-12 cannot have new or greater military capabilities compared with the weapons it replaces.

Yet a new report published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reveals that the new bomb will have new characteristics that will increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

It is important at this point to underscore that the official motivation for the new capabilities does not appear to be improved nuclear targeting against Russia or other potential adversaries. Nonetheless, that will be the effect.

The GAO report describes that the nuclear weapons designers were asked to “consider revisions to the bomb’s military performance requirements” to accommodate both non-strategic and strategic missions. This includes equipping the B61-12 with a new guided tail kit section in an $800 million Air Force program that is “designed to increase accuracy, enabling the military to achieve the same effects as the older bomb, but with lower nuclear yield.”

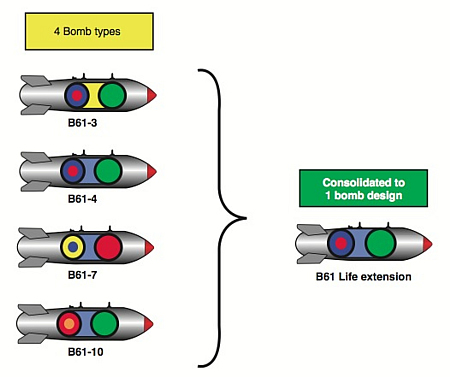

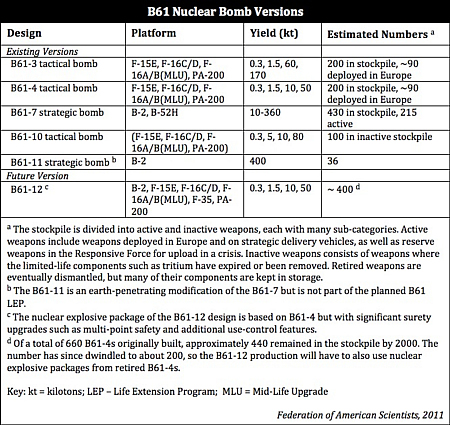

The B61 LEP consolidates four existing B61 types (non-strategic B61-3, B61-4 and B61-10, as well as the strategic B61-7) into one, so the new B61-12 must be able to meet the mission requirements for both the non-strategic and strategic versions. But since the B61-12 will use the nuclear explosive package of the B61-4, which has the lowest yield of the four types (a maximum of 50 kt), increasing the accuracy was added to essentially turn the B61-4 into a B61-7 in terms of targeting capability.

| Consolidating Four Bombs Into One |

|

| This STRATCOM slide used in the GAO report portrays the B61-12 as a mix of components from existing weapons. The message: it’s not a “new” nuclear weapon. But the slide is missing the most important new component: a new guided tail kit section that will increase the weapon’s accuracy. Image: STRATCOM/GAO |

.

The new guided tail kit – the B61 Tail Subassembly (TSA), as it is formally called – will be developed by Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing for the Air Force and similar to the tail kit used on the conventional Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bomb (Boeing has delivered more than 225,000 kits so far). But the B61-12 would be the first time a guided tail kit has been used to increase the accuracy of a deployed nuclear bomb.

The B61-12 accuracy is secret, but officials tell me it is similar to the tail kit on the JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition), which uses a GPS (Global Positioning System)-aided INS (Internal Navigation System). In its most accurate mode it provides the JDAM a circular error probable (CEP) of 5 meters or less during free flight when GPS data is available. If GPS data is denied, the JDAM can achieve a 30-meter CEP or less for free flight times up to 100 seconds with a GPS quality handoff from the aircraft. It is yet unclear if the B61-12 will have GPS, which is not hardened against nuclear effects, but many limited regional scenarios probably wouldn’t have sufficient radiation to interfere with GPS.

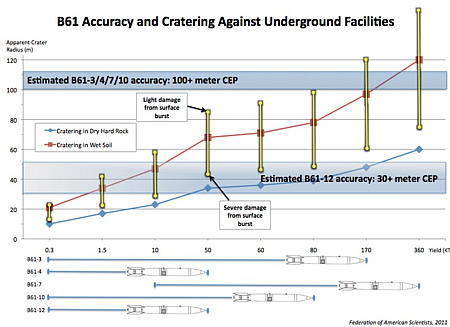

Officials explain that the increased accuracy will not violate the LEP policy in the NPR because the B61-12 will not have higher yield than the types it replaces. The B61-12 nuclear explosive package (NEP) will be based on the B61-4, which has the lowest maximum yield of the four types to be consolidated. The B61-7, in contrast, has a maximum yield of 360 kt (see table). But while B61-12 does not increase the yield of the B61-7, its guided tail kit will increase the targeting capability compared with the existing B61-3/4 and -10 versions.

|

| Click on chart to download larger version. |

.

Targeting Implications

Increasing the accuracy of the B61 has important implications for NATO’s nuclear posture and for nuclear targeting in general.

In Europe, the new guided tail kit would increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons assigned to NATO by giving them a target kill capability similar to that of the high-yield B61-7, a weapon that is not currently deployed in Europe.

This would broaden the range of targets that can be held at risk, including some capability against underground facilities. In addition, delivery from new stealthy F-35 aircraft will provide additional military advantages such as improved penetration and survivability.

Shock damage to underground structures is related to the apparent (visible) radius of the crater caused by the nuclear explosion. For example, according to the authoritative The Effects of Nuclear Weapons) published by the Department of Defense and Department of Energy in 1977, severe damage to “Relatively small, heavy, well-designed, underground structures” is achieved by the target falling within 1.25 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero (the point of detonation), and light damage is achieved by the target falling within 2.5 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero. For a yield of 50 kt – the estimated maximum yield of the B61-12, the apparent crater radii vary from 30 meters to 68 meters depending on the ground (see graph below). Therefore an improvement in accuracy from 100-plus meter CEP (the current estimated accuracy of the B61) down to 30-plus meter CEP (assuming INS guidance) improves the kill probability against these targets significantly by achieving a greater likelihood of cratering the target during a bombing run. Put simply, the increased accuracy essentially puts the CEP inside the crater.

.

The U.S. Department of Defense and NATO agreed on the key military characteristics of the B61-12 in April 2010 – the same month the NPR was published and seven months before NATO’s new Strategic Concept was approved. This included the yield options, that the B61-12 will have both midair and ground-burst detonation options, that it will be capable of freefall (but not parachute-retarded) delivery, and the required accuracy when equipped with the new guided tail section and employed by the F-35. STRATCOM, which provides targeting assistance to NATO, subsequently asked for a different yield, which U.S. European Command and SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) agreed to. Since the NPR prohibits increasing the military capability, STRATCOM’s alternative B61-12 yield cannot be greater than the current maximum yield of the B61-4.

The GAO report states that “neither NATO nor U.S. European Command, in accordance with the NATO Strategic Concept, have prepared standing peacetime nuclear contingency plans or identified targets involving nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added). The “no standing plans” claim is correct because regional nuclear strike planning is no longer done with “standing plans” as during the Cold War. But that doesn’t mean there are no plans at all. Today’s strike planning does not require “standing” plans but relies on new adaptive planning capabilities that can turn out a strike plan within days or weeks.

But the “no identified targets” claim raises an obvious question: If NATO and EUCOM have not “identified targets” for the B61 bombs in Europe, how then can they identify the military characteristics needed for the B61-12 that will replace the bombs in 2018? Obviously, some targets have been identified.

The addition of the tail kit eliminates the need for the existing parachute-retarded laydown option, where a parachute deployed from the rear of the nuclear bomb provides for increased accuracy when employed from an aircraft flying at very low altitude (and allows the pilot (and aircraft) to escape the blast). But a GPS/INS tail kit would also give the B61-12 high accuracy independent of release altitude, weather, and axis of aircraft for much greater survivability.

Reinventing PLYWD: Low-Yield Prevision Nuke

Beyond Europe, the guidance tail kit would also have implications for nuclear targeting in general. Although the B61-12 will not be able to exceed the target kill capability of the maximum yield of the B61-7, the increased accuracy will have an effect on the target kill capability at lower yields. Indeed, the B61-12 concept resembles elements of the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) program from the early-1990s when the Air Force studied combining low-yield warhead options with precision guidance to reduce collateral damage from nuclear strikes.

|

| Click on image to download report. |

.

Much of that study remains classified but parts of it were released to me under the Freedom of Information Act (see box). The study concluded that, “The use of precision guidance could permit the Air Force to accomplish some missions as effectively, or more effectively, with low-yield weapons” (emphasis added). Overall, the study found that a precision, low-yield weapon “can be effective against a large fraction of potential targets, can reduce collateral damage on a significant number of targets, is technically feasible, and can provide aircraft standoff (and thus improve survivability).”

PLYWD was rejected by Congress, which banned work on and development of new warheads with a yield of less than five kilotons. Among other things, Congress was concerned that the combination of precision and low-yield to reduce collateral damage would make nuclear weapons appear more useable and risk lowering the nuclear threshold and increase the risk that nuclear weapons would actually be used.

The issue resurfaced in 2001 with proposals to build low-yield nuclear earth penetrators, but the scenarios were shown to be inherently dirty (examples of analysis here, here, and here). Even so, the Bush administration managed to defeat the ban in 2003 in order to explore advanced concepts of nuclear strike options against regional adversaries (see CRS report for background).

The beauty of the B61-12 program is that it avoids a controversial decision to develop a new low-yield nuclear warhead but achieves many of the PLYWD mission goals by combining the existing lower-yield options of the B61 (down to only 0.3 kt) with the increased accuracy provided by the new guidance tail kit to increase targeting capability while reducing collateral damage.

Interestingly, the PLYWD project emerged after EUCOM (now a recipient of the B61-12) pressed for nuclear weapons with lower yields, Los Alamos National Laboratory (the design lab for the B61) proposed a mini-nuke concept, and the Defense Nuclear Agency (now Defense Threat Reduction Agency) began research on “a very low collateral effects nuclear weapons concept.” In fact, both the Military Characteristics (MC) and Stockpile-to-Target Sequence (STS) documents for PLYWD were based on the B61 MC and STS.

In the future, if funded by Congress, the precision B61-12 would allow a B-2, F-35, F-15E, F-16, as well as the next generation long-range bomber, to destroy targets, which previously required high yield blasts, with lower yields and less radioactive fallout.

The Nonproliferation Argument

The relatively lower yield of the B61-4 means that its secondary (CSA, or Canned Sub Assembly) contains less Highly-Enriched Uranium (HEU) that the B61-3, B61-7, and B61-10 versions. Using the B61-4 nuclear explosive package in the B61-12 to replace the three other higher-yield bombs will remove significant quantities of HEU from the deployed force. In other words, so the argument goes, the B61 LEP is a nonproliferation measure intended to reduce the amount of HEU that would be lost if a B61-12 were ever stolen.

This justification is only partly relevant because roughly half of the weapons deployed in Europe already are B61-4 so returning them as B61-12 with the same nuclear explosive package and amount of HEU will not reduce that portion of the deployed force. The HEU-heavy B61-7s are not stored overseas but in the United States (and so are the B61-10s) and most of those are not even at the bomber bases but in central storage facilities.

| B61-7 and JDAM |

|

| The B61 (front, white) is similar in size to the JDAM (back). All high-yield B61-7s are stored in the United States. Image: USAF |

.

Moreover, the total number of B61-12s to be produced is far lower than the combined number of B61 versions in today’s stockpile – perhaps only around 400, down from an estimated 930 weapons.

Far less clear is how the agencies have determined that the risk of theft of a B61 has increased so much after September 2001 that too much HEU is deployed and existing safety and security features are inadequate to protect the weapons. Not least because a National Academy of Sciences task force recently concluded that “there is no comprehensive analytical basis for defining the attack strategies that a malicious, creative, and deliberate adversary might employ or the probabilities associated with them.” As a result, the task force concluded that it “could not identify how to assess the types of attacks that might occur and their associated probabilities.”

That doesn’t seem to have dampened NNSA’s pursuit of exotic safety and security features for all U.S. nuclear warheads in the name of an increased threat. Ironically, in doing so, NNSA is following White House guidance from 2003 that ordered “incorporation of enhanced surety features independent of any threat scenario” (emphasis added). Apparently, increased surety is not needed because of a specific increased threat but because of a policy.

But no one seems to be asking whether the B61 bombs in Europe are being exposed to unnecessary risks because the Air Force continues to scatter them in underground vaults underneath dozens of aircraft shelters at airbases in five European countries with different security standards; the deployment itself may add to the insecurity of the weapons.

The End of U.S. Non-Strategic Warheads

The B61-12 program marks the end of the 60-year old practice of the U.S. military to have designated non-strategic or tactical nuclear warheads in the stockpile. The only other remaining non-strategic warhead in the stockpile, the W80-0 for the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), is also being eliminated.

| A “Tactical” Nuclear Weapons Phase-Out |

|

| The B61 LEP eliminates the last designated non-strategic (tactical) nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile, a category of warheads that used to dominate the U.S. arsenal, making the disparity with Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons a non-issue. |

.

With the elimination of the last non-strategic bombs (B61-3, -4 and -10), the B61-4 will be converted to meet the mission requirement of the B61-7; essentially, the non-strategic B61-4 will become a strategic bomb. The B61-12 will be carried by both long-range bombers and short-range fighter-bombers; strategic or non-strategic will be determined by the delivery platform rather than the warhead designation.

Ironically, eliminating non-strategic nuclear warheads and instead using strategic warheads in support of NATO actually meets the language of the Alliance’s new Strategic Concept, which states that “The supreme guarantee of the security of the Allies is provided by the strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance” rather than non-strategic bombs (emphasis added).

Implications and Recommendations

The B61 LEP appears to be much more than a simple life-extension of an existing warhead but an upgrade that will also increase military capabilities to hold targets at risk with less collateral damage.

It is perhaps not surprising that the nuclear laboratories and nuclear warfighters will try to use warhead life-extension programs to increase military capabilities of nuclear weapons. But it is disappointing that the White House and Congress so far have not objected.

The NPR clearly states that, “Life Extension Programs…will not…provide for new military capabilities.” I’m sure we will hear officials argue that the B61 LEP doesn’t provide new military capabilities because it doesn’t increase the warhead yield beyond the maximum of the existing four types.

But this narrow interpretation misses the point. Mixing precision with lower-yield options that reduce collateral damage in nuclear strikes were precisely the scenarios that triggered opposition to PLYWD and mini-nukes proposal in the 1990s. Warplanners and adversaries could see such nuclear weapons as more useable allowing some targets that previously would not have been attacked because of too much collateral damage to be attacked anyway. This could lead to a broadening of the nuclear bomber mission, open new facilities to nuclear targeting, reinvigorate a planning culture that sees nuclear weapons as useable, and potentially lower the nuclear threshold in a conflict.

Such concerns ought to be shared by the Obama administration, which has pledged to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and work to prevent that nuclear weapons are ever used. The pledge to reduce the role of nuclear weapons has received widespread international support but will fall flat if one of the administration’s first acts is to increase the capability of nuclear weapons.

How Russia and NATO allies will react remain to be seen, but increasing NATO’s nuclear capabilities at a time when the United States is trying to engage Russia in talks about limiting non-strategic nuclear weapon seems counterproductive.

These talks could become more complicated because the B61 LEP eliminates non-strategic nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile and instead leaves the B61-12 to cover both strategic and non-strategic scenarios. That will further blur the line between strategic and non-strategic weapons and make it a challenge to meet the U.S. Senate’s requirement “to initiate…negotiations with the Russian Federation on an agreement to address the disparity between the non-strategic (tactical) nuclear weapons stockpiles of the Russian federation and of the United States and to secure and reduce tactical nuclear weapons in a verifiable manner.” After the B61 LEP the United States will not have any non-strategic nuclear warheads to negotiate with, essentially making the “disparity” a non-issue.

NATO declared in its Strategic Concept from November 2010 that the alliance “will seek to create the conditions for further reductions in the future” of the number and reliance on nuclear weapons. Increasing the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture appears to contradict that pledge and could lead to increased opposition to continued deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

At the very least, the administration and Congress need to define and publicly clarify what constitutes “new capabilities.” More than $213 billion are planned for nuclear modernizations in the next decade; it’s hard to believe that there will be no “new capabilities” slipping through in that work. In fact, current plans for warhead life-extension programs indicate that the nuclear establishment intends to take full advantage of the uncertainly by increasing the targeting capabilities of the nuclear weapons: it is already happening with the W76 LEP, which is being deployed on submarines with increased targeting capability; it is scheduled to happen with the B61 LEP; and it appears to be planned for the W78 LEP as well.

The logic seems to be: “We’re reducing the number of weapons so of course the remaining ones have to be able to cover more scenarios.” In other words, the price for arms control is increased military capabilities.

The administration should also direct that the portion of the B61-12s that are earmarked for deployment in Europe be deployed without the new guidance tail kit but retain the accuracy of the exiting weapons currently deployed in Europe. Otherwise the B61-12 should not be deployed in Europe.

Finally, the administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review should narrow the role of nuclear weapons to prevent that numerical reductions become a justification for increasing the capabilities of the remaining weapons. The new guidance must depart from the “warfighting” mentality that still colors nuclear war planning and is so vividly illustrated by the precision low-yield options offered by the B61-12.

NOTE: This blog is also available in PDF format as an Issue Brief.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The B61 Life-Extension Program: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal. The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy. As a result, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with an enhanced capability targets.

Upsetting the Reset – The Technical Basis of Russian Concern Over NATO Missile Defense

The Obama administration is working with NATO to develop a missile defense shield to protect U.S. and European interests from ballistic missile attacks by Iran. Russian President Dmitry Medvedev has expressed strong concerns over this shield and has warned of a return to Cold War tensions, as well as possible withdrawal from international disarmament agreements like the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START).

On June 9, the NATO-Russia Council plans to meet with defense ministers to establish cooperation guidelines for the new European antiballistic missile system. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is releasing a new report that addresses concerns made by officials of the Russia Federation and provides recommendations for moving forward with a missile defense system..

Dr. Yousaf Butt, Scientific Consultant to FAS, and Dr. Theodore Postol, Professor of Science, Technology and National Security Policy in the Program in Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have published a technical assessment (PDF) of the Phased Adaptive Approach (PAA) missile defense system proposed by NATO and the United States and analyzed whether the Russian Federation has a legitimate concern over the proposed NATO-U.S. missile defense shield.

In practice the PAA will provide little, if any, protection leaving nuclear deterrence fundamentally intact. While the PAA would not significantly affect deterrence, it may be seen by cautious Russian planners to impose some attrition on Russian warheads. While midcourse missile defense would not alter the fundamental deterrence equation with respect to Iran or Russia, it may, in the Russian view, constitute an infringement upon the parity set down in New START.

Chinese Jin-SSBNs Getting Ready?

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two of China’s new Jin-class nuclear ballistic missile submarines have sailed to the Xiaopingdao naval base near Dalian, a naval base used to outfit submarines for ballistic missile flight tests.

The arrival raises the obvious question if the Jin-class is finally reaching a point of operational readiness where it can do what it was designed for: launching nuclear long-range ballistic missiles.

The Pentagon reported a year ago that development of the missile – known as the Julang-2 (JL-2) – had run into developmental problems and failed its final test launches.

The Long March to Operational Capability

Even if the Jin subs are in Xiaopingdao to load out for upcoming missile tests and manage to pull it off, the submarines are unlikely to become operational in the sense that U.S. missile submarines are operational when they sail on patrols.

Chinese ballistic missiles submarines have never sailed on a deterrent patrol or deployed with nuclear weapons on board. Chinese nuclear weapons are stored on land in facilities controlled by the Central Military Commission (CMC), and the Chinese military only has a limited capability to communicate with the submarines while at sea.

It is possible, but unknown, that the two submarines are the same two boats that have seen fitting out at the Huludao shipyard for the past several years. One submarine was also seen at Jianggezhuang naval base in August 2010 (see below). Prior to that a Jin-class SSBN was seen seen at Xiaopingdao in March 2009, and at Hainan Island in February 2008. The first Jin-class boat was spotted in July 2007 on a satellite photo from late-2006.

|

| One of the Jin-class SSBNs was seen at Jianggezhuang in August 2010, the first time commercial satellite images have shown a Jin-class submarine at China’s northern fleet submarine base. |

.

And Then What?

Indeed, it is unclear how China intends to utilize the Jin-class submarines once they becomes operational; they are unlikely to be deployed with nuclear weapons on board in peacetime like U.S. missile submarines, so will China use them as surge capability in times of crisis?

Deploying nuclear weapons on Jin-class submarines at sea in a crisis where they would be exposed to U.S. attack submarines seems like a strange strategy given China’s obsession with protecting the survivability of its strategic nuclear forces. The Jin-class SSBN force seems more like a prestige project – something China has to have as a big military power.

Whether it makes sense is another matter.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

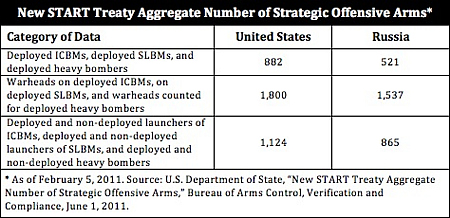

New START Aggregate Numbers Released: First Round Slim Picking

|

| You won’t be able to count SS-18s in the New START aggregate date. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia and the United States have released the first Fact Sheet with aggregate numbers for the strategic offensive nuclear forces counted under the New START treaty.

It shows that Russia has already dropped below the New START ceiling of 1,550 accountable deployed warheads and the United States is close behind, seven years before the treaty is scheduled to enter into effect (it makes you wonder what all the ratification delay was about).

But compared with the extensive aggregate numbers that were released during the previous START treaty, the new Fact Sheet is slim picking: just six numbers.

Unless the two countries agree to release more information in the months ahead, this could mark a significant step back in nuclear transparency.

The Aggregate Numbers

The Fact Sheet includes six numbers for three categories of counted U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arms under the treaty:

United States

The table lists 882 deployed delivery vehicles. Since we know this includes 450 ICBMs and 288 SLBMs, the number of bombers counted appears to be 144. Less than half of those (about 60 B-2 and B-52H) are actually assigned nuclear missions, the balance being “phantom” bombers (B-52H and B-1B) that have some equipment installed that makes them accountable under the treaty.

The 1,800 deployed warheads include approximately 500 on 450 ICBMs and approximately 1,152 on 288 SLBMs. The remaining 148 warheads constitute the remaining “fake” count of one weapon per deployed bomber. That means our estimate was only four warheads off (!).

If subtracting the 144 “fake” bomber weapons, the actual number of U.S. deployed strategic warheads on ICBMs and SLBMs is 1,656, only about 100 warheads from the New START ceiling. The actual number of bomber weapons present at the bases, we estimate, is 300 or less. They are not deployed on the bombers, so they are not counted by New START, but they were counted by the United States during the now-expired Moscow Treaty (SORT). So the real number of operationally available warheads may be around 1,950, which is what we estimated in March.

Another 2,290 non-deployed strategic warheads are in reserve and there are about 760 non-strategic warheads for a total stockpile of approximately 5,000 warheads. Another 3,500 or so warheads are awaiting dismantlement for a total inventory of roughly 8,500 warheads.

The total number of 1,124 deployed and non-deployed missiles and bombers shows that there are 242 non-deployed missiles and bombers. That number includes 48 SLBMs for two non-deployed SSBNs and additional test SLBMs, reserve Minuteman ICBMs and 50 retired Peacekeeper ICBMs, and heavy bombers in overhaul.

The United States has declassified considerable information in the past and hopefully will continue to do so in the future, so the limited aggregate numbers has fewer implications than in the case of Russia. But it would help to see a breakdown of bombers and non-deployed missiles.

Russian Federation

The effect of the limited aggregate numbers has a much more significant effect on the ability to understand the Russian nuclear posture. Most important is the absence of a breakdown of strategic delivery vehicles.

The number of deployed delivery vehicles is listed as 521. The final aggregate number from the expired START treaty was 630 as of July 1, 2009. Not surprisingly, a reduction because the SS-18, SS-19, SS-25 and SS-N-18 are being phased out. But the limited aggregate information makes it impossible to see which missiles have been reduced.

In our latest estimate we counted 534 deployed delivery vehicles, or 13 more than the New START data. The difference may reflect that some SLBMs on Delta IV SSBNs were not fully deployed and a slightly different composition of the ICBM force.

The Fact Sheet lists 1,537 deployed warheads, which actually translates into 1,461 warheads because 76 of them are “fake” bomber weapons. That means Russia has already met the warhead limit of New START – seven years before the treaty enters into effect.

Despite the uncertainty about the force structure, our latest estimate of Russian strategic nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs was only 122 warheads off.

The aggregate deployed warhead number also more or less confirms long-held suspicion that Russia normally loads its missiles with their maximum capacity of warheads, in contrast to the United States practice of loading only a portion of the warheads.

That means that Russia only has comparatively few strategic warheads in reserve (essentially all bomber weapons). New START does not count such warheads, nor does it count 3,700-5,400 non-strategic warheads in storage or some 3,200 warheads awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of up to 11,000 warheads.

The total aggregate number for deployed and non-deployed delivery vehicles is listed as 865. That shows us that Russia has 344 non-deployed delivery vehicles, a considerable amount given the relatively limited size of their deployed force of 521 delivery vehicles. Since Russia has a limited number of bombers more or less exclusively committed to the nuclear mission, the non-deployed delivery vehicles mainly include retired ICBMs. It would be good to hear whether they will be destroyed or stored.

Additional releases

Each of the two parties to New START can decide under the treaty to release additional information to the public about their own nuclear postures. Given the limited information in the aggregate numbers Fact Sheet, it would be a huge disappoint if they don’t.

I understand from the U.S. government that it is planning to do so later this year, and it is important that Russia considers doing so as well.

Under the terms of the treaty the two parties may also agree to jointly release additional information.

Implications

At a first glance the aggregate numbers released by the United States and Russia under the New START treaty is a huge disappointment. It represents a step back in nuclear transparency compared with the standard set by the same two countries under the previous START treaty.

Earlier last month, Ambassador Linton Brooks, Ambassador Jack Matlock and Secretary William Perry joined FAS in calling on the United States and Russia to continue to meet this standard.

We have yet to receive a formal reply but the aggregate numbers Fact Sheet is a reply of sort.

It ought to be a natural that international nuclear transparency is increased with each new treaty, that previously unaccounted categories are brought under accounting, and that uncertainties are cleared up. Moreover, international nuclear transparency means transparency not just for the two parties to the treaty but for the international community as well.

The aggregate numbers Fact Sheet includes the total number of warheads actually deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, an important improvement from the previous treaty. But the breakdown of number of delivery vehicles and deployment locations has moved into the black.

As mentioned above, the United States and Russia have the right under the treaty – individually or jointly – to release additional information about their nuclear force structures.

It is essential that they do so and continue to do so with each future aggregate numbers Fact Sheet release. Otherwise, the uncertainty about their forces could accumulate and undermine predictability and transparency for other nuclear powers. That, in turn, could make it harder to get those countries involved in nuclear arms control in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Letter Urges Release of New START Data

|

| Ambassador Brooks, Secretary Perry and Ambassador Matlock join FAS in call for continuing nuclear transparency under New START treaty |

.By Hans M. Kristensen,

Three former U.S. officials have joined FAS in urging the United States and Russia to continue to declassify the same degree of information about their strategic nuclear forces under the New START treaty as they did during the now-expired START treaty.

The three former officials are: Linton Brooks, former chief U.S. START negotiator and administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, Jack Matlock, former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan for national security affairs, and William Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense.

At issue is whether the United States and Russia will continue under the New START treaty to release to the public detailed lists – known as aggregate data – of their strategic nuclear forces with the same degree of transparency as they used to do under the now-expired START treaty. There has been concern that the two countries might reduce the information to only include numbers of delivery systems but withhold information about warhead numbers and locations.

In a joint letter, the three former officials joined FAS President Charles Ferguson and myself in urging the United States and Russia to “continue under the New START treaty the practice from the expired START treaty of releasing to the public aggregate numbers of delivery vehicles and warheads and locations.” This practice contributed greatly to international nuclear transparency, predictability, reassurance, and helped counter rumors and distrust, the letter concludes.

Both governments have stated their intention to seek to broaden the nuclear arms control process in the future to include other nuclear weapon states and the letter warns that achieving this will be a lot harder if the two largest nuclear weapon states were to decide to decrease transparency of their nuclear forces under New START.

“Any decrease in public release of information compared with START would be a step back.”

The letter was sent to Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, and Sergey Kislyak, the Ambassador of the Russian Federation to the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pakistan’s “Shoot and Scoot” Nukes: FAS Nukes in Newsweek

|

| Pakistan’s military describes its new short-range nuclear NASR missile as a “shoot and scoot…quick response system.” Image: ISPR |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Andrew Bast at Newsweek was kind enough to use our estimates for world nuclear forces in his latest article on Pakistan growing arsenal.

Of special interest is Pakistan’s production of the NASR (Hatf-9), a worrisome development for South Asia and the decade-long efforts to avoid nuclear weapons being used. With its range of only 60 kilometers, the multi-tube NASR system is not intended to retaliate against Indian cities but be used first against advancing Indian army forces in a battlefield scenario.

Pakistan’s military’s Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR) describes NASR as a system that “carries nuclear warheads of appropriate yield with high accuracy, shoot and scoot attributes” developed as a “quick response system” to “add deterrence value” to Pakistan’s strategic weapons development program “at shorter ranges” in order “to deter evolving threats.”

“Shoot and scoot…quick response system” ??

That sounds like an echo from nuclear battlefields in Europe at the height of the Cold War. It is time for Pakistan to explain how many nuclear weapons, of what kind, and for what purpose are needed for its minimum deterrent.

As bad as it is, though, talk about Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal passing the size of France at some point is, at the current rate, probably one or two decades ahead.

Don’t forget: Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is not equal to the number of warheads that could potentially be produced by all the highly-enriched uranium and plutonium Pakistan might have produced. The size also depends on other factors such as the number of delivery vehicles and other limitations.

More information in the next Nuclear Notebook scheduled for publications in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on July 1st.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Article: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2011

|

| Russia has 3,700-5,400 nonstrategic nuclear weapons, including the old dual-capable AS-4 Kitchen air-launched missile seen here under the wings of a Tu-22 Backfire bomber at an unknown airbase. All Russian nonstrategic warheads are in central storage. Image: web |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists with our updated estimate of Russian nuclear forces is now available via Sage Publications: http://bos.sagepub.com/content/67/3/67.full.pdf+html.

We estimate that Russia currently has nearly 2,430 strategic warheads assigned to operational strategic missiles and bombers, although most of the bomber weapons are probably in central storage. Another 3,700-5,400 nonstrategic warheads are in central storage, of which an estimated 2,080 can be delivered by nonstrategic aircraft, naval vessels and short-range missiles. Another 3,000 warheads are thought to be awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of some 11,000 nuclear warheads.

See also: US Nuclear Forces, 2011 | US Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 2011 | Nonstrategic Nuclear Weapons After the Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (Brief 2011)

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Defense Science Board: Air Force Nuclear Management Needs Improvements

|

| The Defense Science Board recommends reducing the number of inspections of nuclear bomber and missile units. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s “independent” Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety has completed a review of the Air Force’s efforts to improve the safety and proficiency of its nuclear bomber and missile units. The report comes three and a half years after the notorious incident at Minot Air Base where six nuclear cruise missiles were mistakenly loaded onto a B-52H bomber and flown across the United States.

The report, Independent Assessment of the Air Force Nuclear Enterprise, finds progress has been made but also identifies some serious issues that still need to be fixed. Some of them are surprising.

Inspections Gone Amok

The most important finding is probably that the nuclear inspection system following Minot has gone amok and in some cases become counterproductive. The number and scope of inspections were increased in response to the incident, but now they have become so frequent and widely applied that nuclear units have neither the time nor resources to correct the deficiencies that are actually identified. Instead the inspection system needs to be limited and focused on where the problems are.

It is natural that leadership will want to demonstrate rigorous efforts to correct deficiencies after a serious incident like Minot by beefing up inspections and exercises as proof that they’re taking things seriously. But this has resulted in a continuous and across-the-board level of inspections and exercise activity that part of the Air Force leadership sees as needed “until a zero-defect culture can be reestablished.”

In reality there has probably never been a zero-defect situation and, when overdone, the high level of inspections and exercises lead to an unrealistic zero-risk mindset. In other words, the leadership needs to cultivate a realistic inspection culture that is focused on detecting and correcting defects rather than expecting to eliminate them.

Over-focus on zero-defect can create distrust in the lower ranks that the leadership doesn’t trust them to perform professionally. This is, the DSB report bluntly concludes, “creating a leadership mindset where satisfying a Nuclear Surety Inspection team, for example, can supplant, or at least compete with, focus on readiness to perform the assigned nuclear mission.”

And nuclear inspection excess combined with multiple over-laying agencies and organizations can create bizarre situations such as in the case of inspections of Munitions Support Squadrons (MUNSSs) in Europe where it is not uncommon to have 80-90 inspectors examining a unit with a total manning of less than 150 personnel.

The report recommends returning gradually to the normal 18-month inspection scheduled used before the Minot incident, and states that additional inspections should occur “only to address unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends.” In other words: no additional inspections unless a problem has already been detected.

For the Air Force’s nuclear deployment in Europe, the report recommends that follow‐up re‐inspections and special inspections of air bases and other nuclear units be discontinued unless unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends have been identified. For all other discrepancies the wing commander or the MUNSS commander should be accountable for closing out the discrepancies in communication with the appropriate inspection agency. Serious security issues were found at European bases in 2008 and evidently had still not been fixed in 2010.

The DSB report does not, however, describe in detail how or to what extent the nuclear proficiency level has evolved in the nuclear units as a result of the increased inspections and oversight established after 2007. It concludes that a culture of special attention to nuclear issues has been reestablished at the operational level, but not fully at the supporting system of the Air Force nuclear enterprise. It would have been interesting to see how that has affected the actual nuclear inspection grades of the individual units.

Resources Still Lacking

While the Air Force leadership has spoken at length about the importance of improving the nuclear proficiency and safety, the report concludes that the leadership has not yet put the money where its mouth is in terms of prioritizing budgets, upgrades of support equipment, directives and technical orders, and tailoring personnel policies to specific nuclear missions. There is still a degree of business-as-usual in planning and acquisition.

For example, the report identifies that 40-plus year munitions hoists are not being replaced, that engineering requests for reentry vehicles has skyrocketed from 100 in 2007 to 1,100 in 2010, and that repairs of nuclear Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMTs) at bases in Europe has been delayed by missing spare parts. There are currently 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs scattered across six bases in five European countries. The 14 WMTs are scheduled for replacement with the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS) in 2014.

Reliability But No Trust

The report concludes that the Air Force’s Personal Reliability Program (PRP), intended to ensure that only qualified people are allowed access to nuclear weapons, has not improved and in some cases increasingly suffers from defects. One problem identified is a continuing escalation of the pursuit of absolute assurance of personal reliability, which the report concludes created “important dysfunctional aspects in the program” where threat of suspension and decertification has produced an environment of distrust. People that have been selected are not sufficiently trustworthy to live an acceptable daily life and must continuously reestablish their credibility. According to the report:

“Even the possibility of Potentially Disqualifying Information (PDI) leads to temporary decertification until it is established that there has been no compromise of reliability. Based on this fundamentally flawed assumption, the PRP repeatedly reexamines the history of each individual.”

“As one example of the consequences of this attitude, personnel are automatically suspended from PRP duties when referred by Air Force medical authorities to off‐base medical treatment regardless of the nature of the referral. The individual must then report to base medical authorities to be reinstated.”

Personnel issues also continue to plague the nuclear wings and MUNSS units in Europe, where the DSB report describes personnel management has created “a flow of people who have no nuclear experience into the key DCA wing in Europe” [i.e. 31st FW at Aviano] and the MUNSS sites at national bases.

As a result, the DSB report recommends that Air Force PRP-based restrictions and monitoring standards be reduced to match those required by DOD.

Command Structure Readjustment

The DBS report also recommends that the nuclear command structure that was set up after the Minot incident be readjusted to that all base-level operations and logistics functions be assigned to the strategic missile and bomb wings reporting through the numbered air forces to Air Force Global Strike Command.

One effect of this command readjustment is the transfer of all munitions squadrons responsible for nuclear mission support from Air Force Material Command to the Air Force Global Strike Command within the next 12 months, recently described by the Air Force.

Download Defense Science Board report

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

10 NATO Countries Want More Transparency for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| Ten NATO countries recommend increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons, including numbers and locations at military facilities such as Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. Neither NATO nor Russia currently disclose such information. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Four NATO countries supported by six others have proposed a series of steps that NATO and Russia should take to increase transparency of U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The steps are included in a so-called “non-paper” that Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland jointly submitted at the NATO Foreign Affairs Minister meeting in Berlin on 14 April.

Six other NATO allies – Belgium, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, Luxemburg and Slovenia – also supported the paper.

The four-plus-six group recommend that NATO and Russia:

- Use the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) as the primary framework for transparency and confidence-building efforts concerning tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

- Exchange information about U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons, including numbers, locations, operational status and command arrangements, as well as level of warhead storage security.

- Agree on a standard reporting formula for tactical nuclear weapons inventories.

- Consider voluntary notifications of movement of tactical nuclear weapons.

- Exchange visits by military officials [presumably to storage locations].

- Exchange conditions and requirements for gradual reductions of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, including clarifying the number of weapons that have been eliminated and/or stored as a result of the 1991-1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs).

- Hold a NRC seminar on tactical nuclear weapons in the first quarter of 2012 in Poland.

According to estimates developed by Robert Norris and myself, the United States currently has an inventory of approximately 760 non-strategic nuclear weapons, of which 150-200 bombs are deployed in five European countries. Russia (updated estimate forthcoming soon, previous estimate here) has larger inventory of 3,700-5,400 nonstrategic weapons in central storage, of which an estimated 2,000 are deliverable by nuclear-capable forces.

The proposal comes as the first phase of NATO’s new Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR) has begun preparation of four so-called scoping papers on 1) the threat facing NATO, 2) the alliance’s strategic mission, 3) the appropriate mix of military forces, and 4) the alliance’s arms control and disarmament policy. The four-plus-six initiative seeks to provide input to the DDPR as well as future work of NATO’s new Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) Control and Disarmament Committee. The results of the DDPR are scheduled for approval by the alliance at the summit in March 2012.

Five of the 10 countries supporting the new initiative also were behind an initiative in February 2010 that urged the alliance to include its nuclear policy on the agenda for the NATO meeting in Tallinn in April 2010. The non-paper builds on a previous Polish-Norwegian initiative from April 2010 that is not described.

The Strategic Concept adopted by NATO in November 2010 removed much of the language that previously had identified U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe as the trans-Atlantic “glue” in the alliance. Unfortunately, after unilaterally reducing the U.S. weapons in Europe by more than half between 2000 and 2010 and insisting that the deployment was not linked to Russia, NATO reinstated Russia as an official link by concluding in the Strategic Concept that “any” reductions in the U.S. deployment must take into account the disparity with Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The four-plus-six paper does not explicitly call for new cuts and explicitly rejects unilateral reductions. However, it states that transparency and confidence building are “crucial to paving the way for concrete reductions.” To that end the paper is in tune with statements recently made by Gary Samore, Special Assistant to the President and White House Coordinator for Arms Control and Weapons of Mass Destruction, Proliferation, and Terrorism, and by Rose Gottemoeller, Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Arms Control, Verification and Compliance.

I’m an avid supporter of increasing transparency, but given the success of the unilateral Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs) of 1991-1992 in jumpstarting reductions in non-strategic nuclear weapons without verification, I’m a little concerned about how ready some are to reject unilateral cuts. After all, the United States and NATO have just approved one: retirement of the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack missile (TLAM/N). Rather, transparency, unilateral cuts, and negotiated reductions should all be embraced as tools to move the process forward of reducing the number and role of nuclear weapons.

See: NATO Non-Paper on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

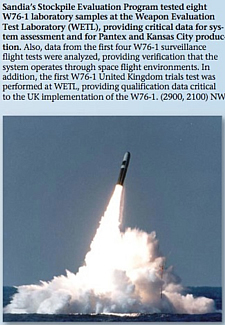

British Submarines to Receive Upgraded US Nuclear Warhead

Sea-launched ballistic missiles on British ballistic missile submarines will be armed with the upgraded W76-1 nuclear warhead currently in production in the United States, according to a report from Sandia National Laboratories.

According to the Labs Accomplishments from March 2011, “the first W76-1 United Kingdom trials test was performed at WETL [Weapon Evaluation Test Laboratory], providing qualification data critical to the UK implementation of the W76-1.”

The Royal Navy plans to “integrate” the US W76-1/Mk4A warhead onto British SSBNs.

Rumors have long existed that the nuclear warhead currently used on British sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) is very similar to the U.S. W76 warhead deployed on American SLBMs. Official sources normally don’t give U.S. warhead designations for the British warhead but use another name. A declassified document published by the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) in 1999, which I published in 2008, described maintenance work on the W76 warhead but called the British version the “UK Trident System.”

|

| Labs Accomplishments from Sandia National Laboratories describes “the first W76-1 United Kingdom trial test” and “UK implementation of the W76-1.” Download the publication here. |

The Sandia report, on the contrary, explicitly uses the U.S. warhead designation for the warhead on British SLBMs: W76-1.

Approximately 1,200 W76-1s are current in production at the Pantex Plant in Texas. The W76-1 is an upgraded version of the W76-0 (or simply W76) produced between 1978 and 1987. In its full configuration, the upgraded weapon is known as the W76-1/Mk4A, where the Mk4A is the designation for the cone-shaped reentry body that contains the W76-1 warhead.

After first denying it, the British government has since confirmed that the Mk4A reentry body is being integrated onto the British SLBMs but it has been unclear which warhead it will carry: the existing warhead or the new W76-1. The Sandia report appears to show that the United Kingdom will get the full package: W76-1/Mk4A.

HMS Vanguard launches US-supplied Trident II D5 SLBM off Florida in October 2005. In the future, missiles on British submarines will carry US-supplied W76-1/Mk4A nuclear warheads.

The upgrade extends the service life by another 30 years to arm U.S. and British nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) through the 2040s. That timeline fits the 2010 British Strategic Defence Review finding that “a replacement warhead is not required until at least the 2030s.”

|

| HMS Vanguard launches US-supplied Trident II D5 SLBM off Florida in October 2005. In the future, missiles on British submarines will carry US-supplied W76-1/Mk4A nuclear warheads. |

.

The transfer of W76-1/Mk4A warheads to the United Kingdom further erodes British claims about having an “independent” deterrent. The missiles on the SSBNs are leased from the U.S. Navy, the missile compartment on the next-generation SSBN will be supplied by the United States, and new reactor cores that last the life of future submarines hint of substantial U.S. nuclear assistance.

The transfer of nuclear technology from the United States to Britain is authorized by the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defense Agreement, which was most recently updated in 2004 and extended through 2014 to permit the “transfer of nonnuclear parts, source, byproduct, special nuclear materials, and other material and technology for nuclear weapons and military reactors” between the two countries. The will text is secret but a reconstructed version is here (see note 3).

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Nick Ritchie at Bradford University (“US-UK Special Relationship”) and John Ainslie at Scottish CND.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

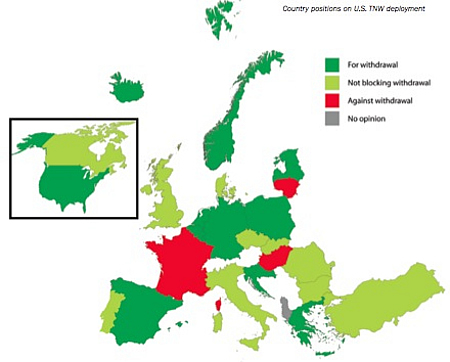

Report: What NATO Countries Think About Tactical Nukes

|

| Most NATO countries support withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe, only three oppose, according to interviews with NATO officials. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Two researchers from the Dutch peace group IKV Pax Christi have published a unique study that for the first time provides the public with an overview of what individual NATO governments think about non-strategic nuclear weapons and the U.S. deployment of nuclear bombs in Europe.

Their findings are as surprising as they are new: 14, or half of all NATO member states, actively support the end of the deployment in Europe; 10 more say they will not block a consensus decision to that end; and only three members say they oppose ending the deployment.

Anyone familiar with the debate will know that while there are many claims about what NATO governments think about the need for U.S. weapons in Europe, the documentation has been scarce – to say the least. Warnings against changing status quo are frequent and just yesterday a senior NATO official told me that, “no one in NATO supports withdrawal.”

The report, in contrast, finds – based on “interviews with every national delegation to NATO as well as NATO Headquarters Staff” – that there is overwhelming support in NATO for withdrawal.

The most surprising finding is probably that most of the Baltic States support withdrawal, only Lithuania does not.

Even Turkey, a country often said to be insisting on continued deployment, says it would not oppose a withdrawal.

The only real issue seems to be how a withdrawal would take place. The three opposing countries – one of which is France – block a potential consensus decision, a condition for 10 countries to support withdrawal.

The Obama administration needs to take a much more proactive role in leading NATO toward a decision to end the U.S. deployment in Europe. This can be done without ending extended deterrence and without weakening the U.S. commitment to NATO’s defense.

Background: IKV Pax Christi study | Nuclear Notebook: U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe, 2011

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.