Produce to Reduce: The Hedge Gamble

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the fourth of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See previous posts: 1, 2, 3.

The FY2012 SSMP repeats the promise made in numerous previous government documents and official statements: construction of new factories with greater warhead production capability might enable retirement of some “hedge” warheads after the “responsive complex” has come online in the early-2020s and thereby reduce the overall size of the stockpile.

Today, the United States has approximately 2,150 operational warheads and another 2,850 in the hedge, for a stockpile total of 5,000. The FY2011 SSMP stated (Annex D, p. 2) that the planned production complex would be able to support a stockpile of 3,000-3,500 warheads, a level 1,500-2,000 warheads below today’s stockpile. However, it did not provide a timetable or strategy for any such reductions.

The FY2012 SSMP does, however, place conditions on further reductions. The report states that the number of nuclear weapons in the nation’s stockpile “may be reduced…if planned LEPs are completed successfully, the future infrastructure of the NNSA enterprise is achieved, and geopolitical stability permits” (emphasis added). The first two items on this list will not be accomplished for at least twenty years, but the plan shows that production of “hedge” warheads will continue even after that.

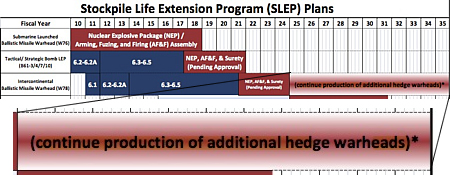

Specifically, the FY2012 SSNP states that this new production capacity is required “regardless of the size of stockpile” and shows that NNSA now plans to produce W78 hedge warheads during the 2021-2024 W78 LEP and even “continue production of additional hedge warheads” through 2035.

| NNSA Plans Production of More Hedge Warheads |

|

| Despite a promise that construction of new warhead production facilities will permit a reduction of the “hedge” of non-deployed warheads in the stockpile, the FY2012 SSMP shows that the new facilities will be used to produce “additional hedge warheads.” The key phrase is enlarged above. Click on image to see the original. |

.

The chart hints that hedge warhead production might also be part of the other warhead LEPs in the NNSA plan. The reason for the additional W78 hedge production in 2025-2035 is not stated. Right now, there are approximately 600 W78s in the stockpile, of which 350 are in the hedge. Are they planning to increase the latter number? Or is that simply continuing production of the “common or adaptable” warhead that would be actually used in the W88 LEP later on? Have other LEPs not been performed on warheads in the hedge, but they will here? The answer is a mystery.

Yet the use of new warhead production facilities to produce additional hedge warheads undermines the administration’s message that the new facilities are needed to allow a reduction of the stockpile. It suggests that even with a new “responsive” warhead production complex, the future stockpile will still include a sizeable hedge of reserve warheads.

Additionally, although the SSMP states that these facilities are needed to “maintain a safe, secure, and reliable arsenal over the long term,” these facilities will not be operational until most of the currently planned Life Extension Programs are either completed or well underway. That makes the plan to use the new facilities to produce additional hedge warheads particularly problematic.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Hydrodynamic Tests: Not to Scale

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the third of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See previous posts: 1, 2, 4.

Since the 1950s, the performance of U.S. nuclear warheads has been successfully validated using a wide range of simulation experiments, such as the compression of fissile material in hydrodynamic tests. And as the stockpile ages “and modernization design options become more complex,” the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) states, “subcritical experiment that include special nuclear material will become more important” (emphasis added). (Special nuclear material refers to highly enriched uranium and plutonium, which are key components of a nuclear weapon.)

The SSMP and other documents describe an interest in a type of hydrodynamic test called a “scaled experiment,” which uses more special nuclear material and more closely resembles actual warhead designs. The public justification is to “improve confidence in predictive capabilities and help validate simulation codes,” but part of the reason is also that those codes will become less reliable if NNSA changes the warhead designs by adding new safety and security features during the Life Extension Programs.

Hydrodynamic Experiments

Every year, the United States conducts “hydrodynamic” experiments designed to mimic the first stages of a nuclear explosion. In tests, conventional high explosives are set off to study the effects of the explosion on specific materials. The term “hydrodynamic” is used because material is compressed and heated with such intensity that it begins to flow and mix like a fluid, and “hydrodynamic equations” are used to describe the behavior of fluids. In one type of hydrodynamic test, researchers build a full-scale primary—the first stage of a modern nuclear weapon—but the plutonium is replaced with a metal that has similar density and weight, but is not fissionable. The device is then fired, revealing information on the design’s behavior from the high-explosive detonation to the beginning of the nuclear chain reaction.

|

| A hydrodynamic test of the W76 warhead design is conducted at the Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2005. |

.

Hydrodynamic tests using small amounts of plutonium are conducted underground at the U1a facility at the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS, formerly the Nevada Test Site), while others using surrogate materials occur at the Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Contained Firing Facility at Site 300 of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. The tests vary greatly in scale and purpose (and there is some overlap) but fall into two overall categories: Integrated Weapons Experiments (IWEs) and Focused Experiments (FEs).

|

| A model of a pin shot hydrodynamic experiment. |

Integrated Weapons Experiments (IWEs) use a rough approximation of an actual War Reserve warhead configuration, minus the special nuclear material. They can address many performance-related questions in one test. IWEs are used to validate modern weapon baseline models (the tested warhead designs) and are the most comprehensive tool for validating computer codes based on past nuclear weapon tests. Some IWEs involve “core punches” that use powerful radiographic imaging equipment to photograph the interior of nuclear weapon or surrogates’ components. Others are “pin shot” experiments that use hundreds of fiber optic, electrical or other types of “pins” emanating from a center to determine features of the plutonium pit or a surrogate pit as it implodes (see image). In 2007, NNSA estimated that it needed to conduct approximately 10 IWEs annually to meet its programmatic needs. However, at the time, part of its program included development of the Reliable Replacement Warhead, which Congress cancelled in 2008.

Focused Experiments (FEs) are smaller and less costly experiments than IWEs and are used to study and isolate issues related to specific components or materials used in nuclear weapons. FEs can be used to help validate computer codes and aid in advanced diagnostic development. In 2007, NNSA estimated that it needed approximately 50 focused experiments annually to meet its programmatic needs.

When IWEs, FEs or small-scale experiments involve use of special nuclear material, usually plutonium, they are called “subcritical” tests. “Subcritical” refers to the fact that the amount of special nuclear material used is not enough to initiate a chain reaction. These tests are conducted at the underground U1a facility in Nevada.

According to the nuclear weapons laboratories, hydrodynamic tests “provide essential data in developing and modifying weapons; such as Life Extension Programs” (emphasis added).

Scaled Experiments

The FY2012 SSMP refers to so-called “scaled experiments” as part of the hydrodynamic testing program. In older documents, NNSA describes scaled experiments as imploding “a primary using Pu-239 that is small enough (scaled) so that it remains sub-critical and core punch radiography can be used to validate modeling its gas cavity shape.” Unfortunately, NNSA doesn’t describe what scaled experiments are in its more recent documents or why they are needed, other than noting they “could improve the predictive capability of numerical calculations by providing data on plutonium behavior under compression by high explosives.” (FY12 SSMP, p. 62)

As far as we can gauge, scaled experiments are subcritical, core-punch, hydrodynamic tests designed to conduct experiments in an implosion geometry that is essentially identical to an actual warhead design, but reduced in size. Rather than a full-scale warhead with the plutonium replaced by other material, a one-third to one-half scale model is built that does use plutonium. At a half-scale size, only one-eighth of the plutonium in an actual warhead is required. The smaller amount of plutonium keeps the explosion from beginning a nuclear chain reaction. Eventually, NNSA wants to build scaled experiments to almost three-quarters (0.7) the size of a full primary.

Some NNSA officials claim to have conducted a scaled experiment in 2005, a claim that is disputed by others, including Administrator Tom D’Agostino. Some recent hydrodynamic experiments have involved scaled technologies. Since 2008, for example, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has carried out several experiments to study the size at which conventional high explosive boosters could ignite the main conventional high explosive that compresses the plutonium. The experiments have used half-scale IWE primaries to better understand how boosting of the warhead yield works as the gas cavity is compressed during implosion.

One interesting note is that the push for scaled experiments is coming from NNSA officials, not the nuclear weapons laboratories. The labs have resisted because they are overburdened by the increasingly ambitious Life Extension Programs. NNSA officials claim that scaled experiments could yield ten times more data points and save money because one large scaled experiment could replace twenty of the smaller hydrodynamic experiments conducted today. Lab scientists maintain that scaled experiments would require major new equipment investments that are not currently planned. At present, U1a in Nevada apparently does not have the diagnostic equipment needed to harvest the additional data generated by scaled experiments.

Little additional information is available about scaled experiments, but more may be on the way, at least in classified settings. Congress has asked the independent technical expert group JASON to conduct a study to assess the benefits of these experiments. And NNSA is also conducting a review to better define what it wants from these (and other) tests. But just last week, the Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee barred funding for scaled experiments, stating they “may not be needed for annual assessments of the current stockpile” and “may interfere with achieving the Nuclear Posture Review’s goals and schedule.”

The NNSA was directed by the appropriators to await the results of the JASON study and, if the agency wants to move forward, to “submit a plan explaining the scientific value of scaled experiments for stockpile stewardship and meeting the goals of the Nuclear Posture Review, the costs of developing the capabilities for and conducting scaled experiments, and the impact on other stockpile stewardship activities under constrained budgets.”

That sounds like a reasonable requirement to us.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Ambitious Warhead Life Extension Programs

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the second of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See the other posts: 1, 3, 4.

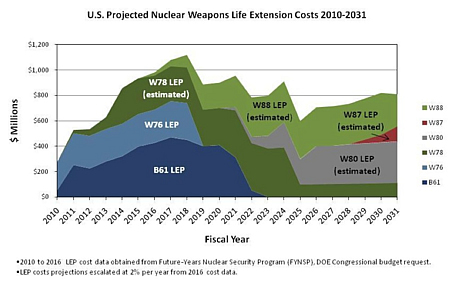

According to the FY2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan (SSMP), from 2011 to 2031, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) plans to spend almost $16 billion on Life Extension Programs (LEPs) to extend the service life and significantly modify almost every warhead in the enduring stockpile. This includes an estimated $3.7 billion on the W88 warhead, $3.9 billion on the B61 bomb, $4.2 billion on the W78 warhead, $1.7 billion on the W76 warhead, and $2.3 billion on the W80-1 warhead.

These figures do not include almost $11 billion in additional NNSA expenses simply to maintain the stockpile, outside of the LEP programs. This brings total spending on nuclear warheads over the next twenty years to $27 billion. These budget figures reflect a significant investment in maintaining and modifying the nuclear stockpile.

|

| The FY2012 SSMP contains a large number of graphs including this one, which adopts the style from the graph FAS and UCS produced in our analysis of the FY2011 plan. |

.

The FY2012 SSMP provides one possible indication that LEP programs are becoming more ambitious and will incorporate more intrusive changes to the warheads. For each weapon type, different variants are designated by a modification, or “Mod” number, as indicated by a hyphen followed by a number at the end of the warhead type, e.g., B61-7 is the “B61 Mod 7.” Only significant changes would result in a new Mod number. For example, the W87 warhead underwent a LEP a decade ago that fixed several structural issues but did not receive a new Mod number. The original warhead designs did not used to have a Mod designation, but the FY12 SSMP lists all the existing warhead types that did not previously have a Mod designation with a “-0” extension. This seems to indicate that all LEPs will now produce warheads with new Mod numbers, apparently in anticipation of significant modifications.

These increasingly intrusive modifications are driven by a stated requirement to improve the safety, security and reliability of the warhead designs. Up to a point, this effort enjoys widespread congressional and White House support—after all, who can be against increasing the safety, security and reliability of nuclear weapons? NNSA and the labs are using these requirements as a primary justification for creating wide-ranging simulation, design, engineering, and production programs that, while smaller in output capacity than those during the Cold War, will be exponentially more technically capable.

The SSMP describes how this capability will provide a “comprehensive science basis underpinning deployment of new safety technologies in the stockpile.” This goal also improves the justification of existing facilities—and those still coming on-line—such as DARHT, NIF, Omega, and the Z machine. NNSA’s goal is to incorporate an enormous array of new safety, security, and use control features in almost the entire stockpile by 2031.

The details of these technologies, their justifications, and costs are largely hidden from public scrutiny. A table listing the safety, security, and reliability features of existing warhead types—and of “an ‘Ideal’ System” (warhead)—is contained in the classified Annex B to the SSMP. (For a list of safety and security features probably installed on U.S. warheads, see here.) While some enhancements may be warranted, the justification for all these new features appears to be based on an open-ended development of new technologies for the incorporation of enhanced surety features into warheads independent of any threat scenario.

This pursuit of a wide range of surety improvements justifies the need for substantial warhead modifications and additional production and simulation capabilities. Yet there must be a point of diminishing returns, where the potential improvements are not justified by the monetary costs or the risks to the reliability of the stockpile.

Indeed, stockpile managers and designers used to warn against modifying warheads, noting that doing so could undermine the confidence in reliably predicting the performance of the weapons without nuclear testing. But warhead modification is now a central goal of the stockpile stewardship management program. Indeed, the goal of the LEPs, the FY2012 SSMP states, it to provide options for “maintaining and modifying the future stockpile” (emphasis added). Modification—not just maintenance—of the enduring stockpile has become a core objective. Interestingly, the SSMP bluntly acknowledges that such modifications of the warheads will reduce confidence in the reliability of the stockpile by changing warheads from the designs that were tested:

“An aggressive ST&E [Science, Technology and Engineering] program is replacing…empirical factors [used to calibrate simulation codes based on underground nuclear tests] with scientifically validated fundamental data and physical models for predicting capability. As the stockpile continues to change due to aging and through the inclusion of modernization features for the enhanced safety and security, the validity of the calibrated simulations decreases, raising the uncertainty and need for predictive capability. Increased computational capability and confidence in the validity of comprehensive science-based theoretical and numerical models will allow assessments of weapons performance in situations that were not directly tested.” (Emphasis added).

However, NNSA’s enthusiasm for extensively modifying all warheads may be going beyond what Congress and the Obama administration as a whole will support. The foundation for such objections is clearly laid out in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which states explicitly that the United States “will study options for ensuring the safety, security, and reliability of nuclear warheads on a case-by-case basis.” (p. xiv). This seems to contradict NNSA’s pursuit of every available surety feature for every warhead.

In an example of rising concerns, the May 2011 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the B61 LEP raised red flags about the NNSA’s proposed changes to the bomb. The report expressed concern about the scope of the LEP, noting that it was the first ever that sought to simultaneously refurbish multiple components, enhance safety and surety, and make other design changes. The report noted that some of the proposed new surety features, such as multipoint safety, have never been used in existing stockpile weapons.

Multipoint safety seeks to lessen the chance of an accidental nuclear explosion if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at more than one point nearly simultaneously. The current one-point safety requirement mandates that the risk of a nuclear detonation be no greater than one in a million if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at one point, which the SSMP acknowledges is an “extraordinarily high reliability requirement.” As the GAO notes, warheads in the current stockpile do not have multi-point safety, and even the NNSA does not consider the technology mature.

Because of these issues, the Senate appropriations committee recently expressed its concern about the B61 LEP. The committee’s report notes that “NNSA plans to incorporate untried technologies and design features to improve the safety and security of the nuclear stockpile” (emphasis added). While expressing support for improved surety, the report states that it “should not come at the expense of long-term weapon reliability.” Due to this concern, the committee reduced funding for the B61 LEP by almost 20% and called for both an independent assessment of the proposed safety and security features and a cost-benefit analysis of them.

One gets the sense that, since Congress stopped the Reliable Replacement Warhead, NNSA has seized on safety and security as the sure-fire cause to allow major warhead modifications and win significant funding. Based on the new Senate findings, NNSA may discover there are limits to how far Congress will go down the modification path and what it will spend, even on the golden ticket of improved safety.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

See also: FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan | Previous blog in this series

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Plan Conflicts with New Budget Realities

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the first of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See the other posts here: 2, 3, 4.

A new nuclear weapons plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which seeks further increases in spending over the next decade for nuclear weapons and for weapons production and simulation facilities, will face real challenges in the new budget environment.

The FY2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP), which was sent to Congress in April, is NNSA’s outline of its near- and long-term plans and associated costs for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and supporting infrastructure. However, with national security spending facing real cuts below FY2011 levels for the next two years at a minimum, either the NNSA must overcome that trend or cut back on its plans.

The FY2012 SSMP is unclassified but has two secret annexes. The new plan updates, with input from Congress, the FY2011 SSMP published last year, and is the first plan to fully incorporate the recommendations of the Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.

Increased Nuclear Weapon Spending

The Obama administration has significantly increased the amount of money the United States spends on nuclear weapons, and had planned further increases before the Budget Control Act of 2011 was passed last month. The FY2011 budget proposed in early 2010 increased NNSA’s spending on Weapons Activities by nearly 10 percent relative to the previous year, and the administration later added another $5.4 billion for the 2011-2015 future years nuclear security program. According to the FY2011 SSMP, NNSA planned to spend about $80 billion from 2011 through 2020—or an average of $8 billion per year. In comparison, nuclear weapons budgets in the last years of the Bush administration were around $6.7 billion annually in inflation-adjusted dollars.

The FY2012 SSMP shows that the NNSA plans additional funding increases, beginning with an additional $4 billion for the 2012-2016 future years nuclear program. The NNSA now plans to spend $88 billion on nuclear weapons and the nuclear weapons complex from 2012 to 2021, for a yearly average of $8.8 billion. This is another 10% increase on top of the FY11 SSMP increase.

However, those budget levels may be less than what is required if NNSA’s plans do not change. In particular, cost estimates for two major facilities—the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee and the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement-Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) in Los Alamos, New Mexico—are a cause for concern. The NNSA estimates that the UPF could cost $4.2 billion to $6.5 billion, and the CMRR $3.7 billion to $5.8 billion. The FY12 SSMP hints that the total for both might reach $12 billion, but a footnote in Table 6 on page 67 explains that the ten-year budgets above are based on those facilities coming in at the low end of the current cost estimates. Yet a recent independent estimate by the Army Corps of Engineers concluded that the cost of the UPF alone would be between $6.5 and $7.5 billion, which puts the low end equal to the high end of NNSA’s current estimate.

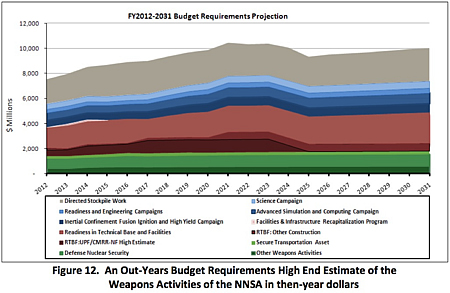

| NNSA Nuclear Weapons Budget Projection 2012-2031 |

|

| Click on image for larger version. Source: U.S. Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration, FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan Report to Congress, April 15, 2011, April 2011, p. 68. |

.

The budget requirements projection for FY12-31 above (Figure 12, taken directly from the FY12 SSMP) provides a budget estimate based on the high end of NNSA’s assumptions for all its costs. The chart indicates that the NNSA plans to spend over $120 billion between FY12 and FY24, when the CMRR and UPF are scheduled to be completed. Based on NNSA’s history, using these high end figures is probably a safe assumption, if not an underestimate.

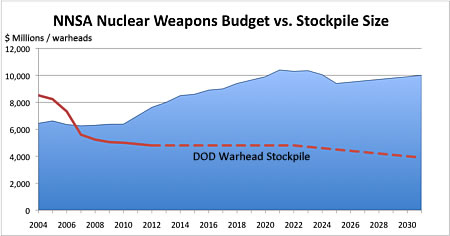

Gone from the FY2012 SSMP is the controversial statement made in the previous SSMP that “the costs to maintain capabilities necessary to support the stockpile are essentially independent of the size of the stockpile.” (Annex D, p. 2.) Yet it is clear from the new plan and other documents that the significant reduction of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile since 2004 has not resulted in any savings in NNSA’s budget, which will continue to increase due to more ambitious warhead modernization plans, cost overruns for the construction of new production facilities, and new simulation and testing facilities. The FY2012 SSMP shows that NNSA would like this trend to continue through the 2020s. See the chart below.

|

| While the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile has declined significantly since 2004, NNSA’s nuclear weapons budget has increased and is projected to grow considerably through the next two decades. Source: NNSA FY12 SSMP; Hans M. Kristensen, Federation of American Scientists. |

.

That desire conflicts with the realities of the Budget Control Act. Rather than a second 10% budget increase as laid out in the FY12 SSMP, the Act calls for a half-percent decrease in national security spending across the board. The House has already passed its version of the key appropriations bill that provides NNSA funding, exacting roughly a 7% cut below the administration’s request for FY2012, leaving a budget less than 3% greater than the FY11 level. The version passed by the Senate appropriations committee was approximately 6% below the request, modestly higher than the House. Because of the Act’s limits, for at least the next several years, NNSA is likely to maintain that level of funding rather than the increased budgets it proposes in the FY12 SSMP.

In short, to live within the new budget priorities that Congress and the administration agreed to in August, NNSA must make significant changes in the timing, scale, and extent of several major projects. Delays, downsizing and perhaps even cancellation of some current priorities seem almost inevitable. The question is: who will make these choices? Will it be the NNSA, the White House, or Congress? And how soon will these decisions be made?

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

See also FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan analysis

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

2012 Nuclear Security Summit in Seoul: Achieving Sustainable Nuclear Security Culture

By Igor Khripunov

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), nuclear security culture is “the assembly of characteristics, attitudes and behavior of individuals, organizations and institutions which serves as a means to support and enhance nuclear security.”[1] The concept of security culture emerged much later than nuclear safety culture, which was triggered by human errors that led to the Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima accidents. Much as these incidents confirmed the importance of nuclear safety, security culture has gained acceptance as a way to keep terrorist groups from acquiring radioactive materials and prevent acts of sabotage against nuclear power infrastructures. Safety and security culture share the goal of protecting human lives and the environment by assuring that nuclear power plants operate at acceptable risk levels.

The 2010 Nuclear Security Summit held in Washington, DC, emphasized the importance of culture as a critical contributing factor to nuclear security:

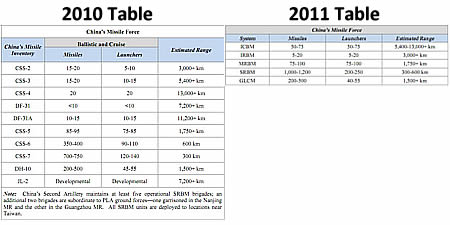

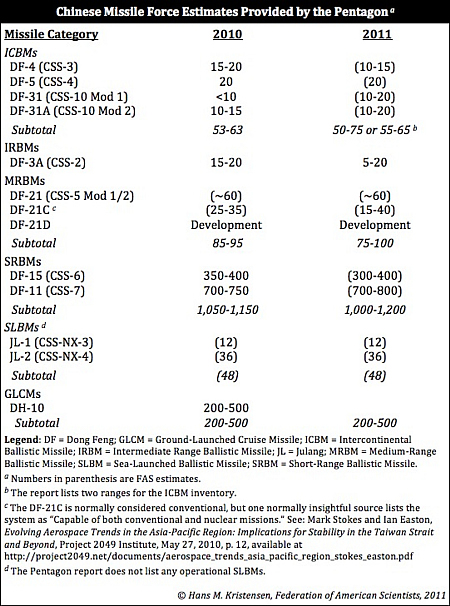

Pentagon’s 2011 China Report: Reducing Nuclear Transparency

|

| The Pentagon’s new report on China’s military forces significantly reduces transparency of China’s missile force by eliminating specific missile numbers previously included in the annual overview. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon has published its annual assessment of China’s military power (the official title is Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China). I will leave it to others to review the conclusions on China’s general military forces and focus here on the nuclear aspects.

Land-Based Nuclear Missiles

The most noticeable new development compared with last year’s report is that the Pentagon this year has decided to significantly reduce the transparency of China’s land-based nuclear missile force. For the past decade, the Pentagon reports have contained a breakdown of Chinese missiles showing approximately how many they have of each type. Not anymore. This year the details are gone and all we get to see are the overall numbers within each missile range category: ICBMs, IRBM, MRBM, SRBM, and GLCMs.

This is something one would expect the Chinese government to do and not the Pentagon, which has spent the last decade criticizing China for not being transparent enough about its military posture.

What the numbers we’re allowed to see indicate is that China’s missile force has been largely stagnant over the past year. The changes have been in minor adjustments, probably involving:

- Phasing out a few older DF-4s and introducing a few more DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs.

- Reducing the DF-3A force and replacing it with the DF-21 MRBMs (which appears largely unchanged but with greater uncertainty).

- Essentially no increase in number of SRBMs off Taiwan.

- The same number of DH-10 GLCMs.

| Addition: Some news media reports unfortunately misrepresent what the Pentagon report says about Chinese nuclear developments:Washington Times (8/25/11)

Claim: “China expanding its nuclear stockpile” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report says nothing about China expanding its nuclear stockpile (the word “stockpile” does appear in the report at all) but that it is “qualitatively and quantitatively improving its strategic missile forces.” But it is a “limited nuclear force.” Claim: “Richard Fisher, a China military-affairs analyst, said the report is significant for listing strategic nuclear forces that show an estimated increase of up to 25 new ICBMs, some with multiple warheads, in a year….” Fact: The Pentagon report lists 50-75 and 55-63 ICBMs (both ranges are listed). The medium values are 59-62 ICBMs. The 2010 report listed 53-63 (58) ICBMs. That is an increase of 1-4 ICBMs, not 25, which is the highest end of the estimate. The Pentagon report does not say that China has deployed ICBMs with MIRV, but that it “may be” developing a new mobile ICBM, “possible capable of carrying” MIRV. China has been researching MIRV since the 1980s but so far not chosen to deploy any. The one thing that could drive China to a decision to potentially deploy MIRV in the future would be a U.S. ballistic missile defense system that diminished the effectiveness of China’s nuclear deterrent. Claim: (Fisher) “China will not reveal its missile-buildup plans…so this simply is not the time to be considering further cuts in the U.S. nuclear force, as is the Obama administration’s intention.” Fact: The United States has 5,000 warheads, China 240. Only about 60 of the Chinese warheads can reach the United States, and only half of those can reach all of the United States. Claim: “Advanced China n-missiles on India border, says Pentagon” (headline) Fact: The Pentagon report does not state that China has deployed nuclear missiles on the Indian border. Instead, the report states in general terms that “To strengthen deterrence posture relative to India, the PLA has replaced” DF-3As “with more advanced and survivable” DF-21s. This is a reference to the DF-21 replacing outdated DF-3A brigades at Chuxiong, Jianshui and Kunming in the Yunnan province and near Delingha and Da Qaidam in the Qinghai province. |

.

Trying to reconstruct the table the way it should have been comes with considerable uncertainty, but here is my best estimate (for corrections I will have to rely on individuals in the Pentagon who think that buying into Chinese government secrecy does not advance U.S. or Northeast Asian interests):

|

| Click on table to download larger version. |

.

Ballistic Missile Submarines

The new Jin-class (Type 094) SSBN appears ready but the Pentagon report states that its JL-2 SLBM “has faced a number of problems and will likely continue flight tests.” The Pentagon previously estimated that the Jin/JL-2 system would become operational in 2010 but the new report now states that it is “uncertain” when the new system will become fully operational.

The range of the JL-2 SLBM is extended, somewhat, from 7,200+ km in the 2010 report to 7,400 km in the 2011 report. This does not change the fact that a Jin-class SLBM would have to deploy deep into the Sea of Japan for its JL-2 to be able to strike the Continental United States. Alaska is within range from Chinese waters, but not Hawaii.

The operational status of the old Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN and its JL-1 SLBM “remain questionable.” Neither class has conducted any deterrent patrols yet.

As a result, China does not appear to have any operational sea-launched ballistic missiles at this point.

The report lists only five nuclear attack submarines with the three fleets, down from six last year, suggesting that retirement of the Han-class (Type 091) continues. The Shang-class (Type 093) is operational, and the Pentagon report states that “as many as five third-generation Type 095 SSNs will be added in the coming years.” The U.S. Navy’s intelligence branch estimated in 2009 that the Type 095 will be noisier than the Russian Akula I but quieter than the Victor III.

Chinese attack submarines conducted 12 patrols during all of 2010, the same level as the previous two years.

Underground Facilities

While there has recently been some sensational reporting (see also here) that China since 1995 has built a 5,000-km “great wall” of tunnels under Hebei mountain in the western parts of the Shaanxi province to hide “all of their missiles hundreds of meters underground,” including the DF-5 (CSS-4) ICBM, the reality is probably a little different.

First, as anyone who has spent just a few hours studying satellite images of Chinese military facilities and monitoring the Chinese internet will know, the Chinese military widely uses underground facilities to hide and protect military forces and munitions. Some of these facilities are also used to hide nuclear weapons. The old DF-4, for example, reportedly has existed in a cave-based rollout posture since the 1970s.

The Pentagon report states that China has “developed and utilized UGFs [underground facilities] since deploying its oldest liquid-fueled missile systems and continue today to utilize them to protect and conceal their newest and most modern solid-fueled mobile missiles.” So it is not new but it is also being used for modern missiles.

| Chinese Underground Missile Launcher Facility |

|

| A Chinese mobile missile launcher, possibly for the DF-11 or DF-15 SRBM, emerges from an underground facility at an unknown location. Image: Chinese TV |

.

Second, the particular facility under Hebei mountain appears to be China’s central nuclear weapons storage facility, as recently described by Mark Stokes. The missiles themselves are at the regional bases, although it cannot be ruled out that some may be near Hebei as well. But Stokes estimates that the warheads are concentrated in the central facility with only a small handful of warheads maintained at the six missile bases’ storage regiments for any extended period of time. The missile regiments themselves could also have nearby underground facilities for storing launchers and missiles, although specifics are not known.

One of the Chinese bases with plenty of underground facilities is the large naval base near Yulin on Hainan Island, which I described in 2006 and 2008. The Pentagon report concludes that this base has now been completed and asserts that it is large enough to accommodate a mix of attack and ballistic missile submarines and advanced surface combatants, including aircraft carriers. The report adds that, “submarine tunnel facilities at the base could also enable deployments from this facility with reduced risk of detection.” That would seem to require the submarine exiting from the tunnel submerged; a capability I haven’t seen referenced anywhere yet.

Conclusions

The 2011 Pentagon report shows that China’s nuclear missile force changed little during the past year but appears to continue the slow replacement of old liquid-fueled missiles with new solid-fueled missiles. China’s efforts to develop a sea-launched ballistic missile capability have been delayed.

In an unfortunate change from previous versions of the Pentagon report, the 2011 version significantly reduces the transparency of China’s nuclear missile forces by removing numbers for individual missile types. This change is particularly surprising given the Pentagon’s repeated insistence that China must increase transparency of its military posture. In this case, military secrecy appears to contradict U.S. foreign policy objectives.

The decision to reduce the transparency of China’s missile force is even more troubling because it follows the recent U.S.-Russian decision to significantly curtail the information released to the public under the New START treaty.

The combined effect of these two decisions is that within the past 12 months it has become a great deal harder for the international community to monitor the development of the offensive nuclear missile forces of the United States, Russia and China.

Tell me again whose interest that serves?

See also: 2010 Pentagon Report on China

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rewriting US Presidential Nuclear War Planning Guidance

|

| How will Obama reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the strategic war plan? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Obama administration has begun a review of the president’s guidance to the military for how they should plan for the use of nuclear weapons. The review, which was first described in public by National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, is the ultimate test of President Obama’s nuclear policy; the rest is just words: to what extent will the new guidance reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the war plan?

Although the administration’s Nuclear Posture Review is widely said to reduce the role of nuclear weapons, it doesn’t actually reduce the role that nuclear weapons have today because all the adversaries in the current strategic nuclear war plan are exempt from the reduction. They are either nuclear weapon states, not members of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, or are in violation of their NPT obligations and have chemical or biological weapons. The new guidance would have to remove some of these adversaries from the war plan to reduce the role, or reduce the role that nuclear weapons are required to play against each of them. There are many ways this could be done:

- Reduce the numer of target categories that are held at risk with nuclear weapons.

- Reduce the damage expectancy to be a achieved against individual targets.

- Reduce the number of adversaries in the plan.

- Reduce the number and types of strike options against each adversary.

- Remove the requirement to plan for prompt launch of nuclear forces.

- Remove any requirement to plan for damage limitation strikes.

- End counterforce nuclear planning.

- End the requirement to maintain standing fully operational strike plans.

Reducing the role of nuclear weapons in the war plan requires direct and continuous presidential attention to avoid that the commitments to reducing the number and role of nuclear weapons are watered down by bureaucrats and cold warriors in the National Security Council, Department of Defense, military commands and Services, as well as former officials who are busy lobbying against a reduction.

To support president Obama’s vision of dramatically reduced nuclear arsenals and a reduced role of nuclear weapons on the way to deep cuts of nuclear weapons and eventually disarmament, we published a study in 2009 that proposed a transition from counterforce planning to what we called a minimal deterrent. A study from 2010 further described the current strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-08 Change 1 from February 1, 2009 – this plan is still in effect). Building on those two studies, we have a new op-ed in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that describes what a new presidential directive could look like: A Presidential Policy Directive for a new nuclear path.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Anatomizing Non-State Threats to Pakistan’s Nuclear Infrastructure

The discovery and subsequent killing of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan raises troubling questions. The success of the U.S.’s airborne raid on bin Laden’s compound-undetected by Pakistan’s radar- lends credence to the belief that terrorists might be capable of successfully seizing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons.

Mr. Charles P. Blair has authored a new FAS report (PDF) that addresses the security gap and identifies specific terrorists within Pakistan who are motivated and potentially capable of taking Pakistani nuclear assets. Blair explains in the report details why, amid Pakistan’s burgeoning civil war, the Pakistani Neo-Taliban is the most worrisome terrorist group motivated and possibly capable of acquiring nuclear weapons.

20th Anniversary of START

July 31st is the 20-year anniversary of signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) between the United States and the Soviet Union. The treaty, also known as START I, marked the beginning of a treaty-based reduction of U.S. and Soviet (later Russian) strategic nuclear forces after the end of the Cold War.

START I required each country to limit its number of accountable strategic delivery vehicles (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers) to no more than 1,600 with no more than 6,000 accountable warheads. The treaty came with a unique on-site inspection regime where inspectors from the two countries would inspect each other’s declared force levels. Thousands of other warheads were not affected and the treaty did not require destruction of a single nuclear warhead. START I entered into effect on December 5th, 2001, and expired on December 4, 2009.

Twenty years after the signing of START I, the United States and Russia are still in the drawdown phase of their strategic nuclear forces: START II followed in 1993, limiting the force levels to 3,500 accountable warheads by 2007 with no multiple warheads on land-based missiles; START II was never ratified by the U.S. Senate but surpassed by the Moscow Treaty in 2002, limiting the number of operationally deployed strategic warheads to 2,200 by 2012; The Moscow Treaty was replaced by the New START treaty signed in 2010, which limits the number of accountable strategic warheads to 1,550 on 700 deployed ballistic missiles and long-range bombers by 2018. Like its predecessors, New START does not limit thousands of non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads and does not require destruction of a single warhead.

The Obama administration has stated that the next treaty must also place limits on non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Norway’s Anders Brevik: Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Politics of Cultural Despair

ABOUT THIS REPORT (click to show)

At some point, most security analysts face the dilemma of balancing expediency with analytical thoroughness. Such is the case with Norway’s Anders Breivik. As his victims await burial, Breivik’s treatise—the 1500 page, 2083:

A European Declaration of Independence (click here for PDF link)—became available only a few days ago. While some researchers, mindful of the value of analytical completeness, patiently plod through this massive manifesto, analysts at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) conclude that the nature of Breivik’s attacks, compounded with the extraordinary content of his treatise, raise questions of such immediate concern that the formulation and release of initial analyses are prudent. We present such an effort here as both a highly formatted blog post and as a preliminary report. The former allows for a quick delivery of our preliminary investigation amid a platform for open discussion of a threat that remains, we believe, largely inchoate. The latter conforms to our professional dedication to robust research and application of various relevant analytical methodologies.

While Breivik’s unprecedented attacks alone warrant profound study, his treatise seeks to portend far greater acts of terror and destruction than those visited upon Norway on July 22nd. However, to date, no substantive effort addresses the document’s detailed exposition of the fabrication, delivery and general merits of chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear weapons (CBRN). The paucity of concern and immediacy revolving around Breivik’s assertions of forthcoming CBRN attacks likely result from two interrelated issues. First, Breivik is incarcerated and will likely remain so for the rest of his life; Breivik himself is no longer a threat. Second, some question his technical acumen with regard to CBRN; even if he were free, according to one putative CBRN expert, “Breivik’s WMD idea is not realistic.”[1] We

largely agree with such conclusions. However, any proper risk assessment must conduct a so-called “assumptions check.” Such an exercise has two primary elements: 1) explicitly identifying conclusions that rely, in part or in whole, on assumptions and 2) identifying and evaluating the consequences should such assumptions prove false.[2] Application of an assumptions check to the Breivik case, we believe, precipitates the need for serious and immediate analyses of the treatise’s content for two primary reasons.

First, Breivik has made claims, through his writing as well as to Oslo District Court Judge Kim Heger, that he is in league with extremist cells and that some of these co-conspirators “are already in the process of attempting to acquire chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear materials.”[3] While it is likely that Breivik acted alone, we are not comfortable assuming that this is the case. Moreover, given the operational sophistication of his attacks, and, among other salient components in the case writ large, the overall operational security that he maintained for years, it is axiomatic that Breivik’s threats should be considered in great detail. Indeed, as renowned terrorism expert Gary Ackerman has warned, “History is replete with cautionary tales warning against basing threat assessments on static analyses of an opponent’s motivations and capabilities.”[4] In short, it is possible that subsequent attacks—some perhaps even utilizing CBRN—may be forthcoming, and it is therefore prudent for the intelligence communities to carefully consider Breivik’s writings.

Second, our initial analyses of Brevik’s comprehension of the relevant issues surrounding the fabrication and employment of CBRN concludes that he was motivated and capable of credibly pursuing low-end CBRN attacks—specifically those likely to result in mass effect as opposed to mass destruction . As our report details, this is specifically the case with some biological and radiological agents. Should Breivik be part of a cell of violent extremists, it is possible that his confederates share an equal, if not greater, understanding of the technologies underlying certain CBRN. Moreover, they may have access to the necessary agents and technologies necessary to actualize Breivik’s more ambitious stratagems for the employment of CBRN.

We are presently inclined to conclude that Breivik acted alone. Consequently, his warnings of forthcoming CBRN events are likely invalid. However, given the nature of his attacks and the content of his treatise we urge the security community to seriously consider the possibility that cells of violent extremists are linked to Breivik; the pursuit of a CBRN capability—as well as the possibility of radiological and/or biological use—are a possibility.

Blog posts and reports from the FAS Terrorism Analysis Project are produced to increase the understanding of policymakers, the public, and the press about threats to national and international security from terrorist

groups and other violent non-state actors. The reports are written by individual authors—who may be FAS staff or acknowledged experts from outside

the institution. These reports do not represent an FAS institutional position on policy issues. All statements of fact and expressions of opinion contained in this and other FAS-published reports are the sole responsibility of the author or authors.

See “Alleged Norway Shooter Considered WMD Attack, Jihadi Alliance,” ABC News,

July 24, 2011. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Blotter/anders-breivik-alleged-norway-shooter-considered-wmd-attack/story?id=14148151

Whether we are conscious of it or not, most of us frequently conduct an

assumptions check. For example, imagine that as you are about to lie down in

bed for a night of sleep you suddenly realize that you cannot be sure if you

locked your car doors. You might temporarily assume you did; however,

you mind quickly assesses the consequences of a faulty assumption.

Whether or not you get up, get dressed, and trudge out to your car is largely

the result of the risk assessment you make should the car be unlocked.

Andrew Berwick [pseudonym for Anders Behring Breivik], 2083 A European

Declaration of Independence, July 2011, 1022.

United States Senate Committee on Homeland Security

and Governmental Affairs Hearing on “Nuclear Terrorism: Assessing the Threat to

the Homeland.” Testimony of Gary A. Ackerman, April 2, 2008, 3.

Available at: http://hsgac.senate.gov/public/_files/040208Ackerman3.pdf

Norway’s Anders Brevik: Weapons of Mass Destruction and the Politics of Cultural Despair

CHARLES P. BLAIR, KELSEY GREGG, AND JONATHAN GARBOSE[ref]The authors thank Rebecca A. Remy for her valuable research assistance.[/ref]

July 27, 2011

Ten years after the events of 9/11, it is often forgotten that high fatality terrorist incidents remain a rarity. Indeed, prior to 9/11 the single deadliest terrorist attack was the 1978 Iranian theatre firebombing perpetrated by Mujahedin-e Khalq (MEK: People’s Majahedin of Iran) with 470 fatalities. Since 1970, only 118 incidents of terrorism have killed more than 100 people—0.12 percent of the 98,000 terrorist events encompassing that four decade span. As the death toll of the July 22 attacks in Norway approaches 100, it is useful to appreciate this fact. In addition to recognizing their uncommonly deadly outcomes, two other features related to the attack are salient. First, significant elements of Anders Breivik’s treatise—the 1500 page 2083: A European Declaration of Independence [ref]Andrew Berwick, pseudonym for Anders Behring Breivik, 2083 A European Declaration of Independence, July 2011, hereafter referred to as The Declaration.[/ref] (click here for PDF link)—address the acquisition, weaponization, and use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) agents or devices against Breivik’s perceived enemies. Second, his ideological platform, said by Breivik to represent his role as “Justiciar Knight Commander for Knights Templar Europe and one of several leaders of the National and pan-European Patriotic Resistance Movement,” is largely informed by European racist ideology that first emerged in the nineteenth century and continues to this day. This report principally evaluates the CBRN elements of Breivik’s treatise. A subsequent report (schedule for release in late 2011) will orient Breivik’s ideological underpinnings within the broader historical milieu of European racist thinking. First, however, it is useful to place Breivik’s attack in perspective.

Panel Discussion at Brookings on NATO Nukes

Steve Pifer was kind enough to invite me to participate in a panel discussion at the Brookings Institution about NATO’s nuclear future and the issue of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Alliance’s current Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR).

Steve presented his excellent paper NATO, Nuclear Weapons and Arms Control, Frank Miller, who has been involved in these issue before I could tie my shoe laces, took the “keep US nukes in Europe,” while I argued for the withdrawal of the weapons. Angela Stent moderated the panel.

I’m not yet clear if they’re planning to post a transcript or video, so in the meantime here are my prepared remarks: NATO’s Posture Review and Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons.

For my writings on this blog about NATO nuclear policy issues, go here.

See also recent letter to NATO Secretary General Ander Fogh Rasmussen coordinated by ACA and and BASIC and signed by two dozen nuclear experts and former senior government officials.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces 2011

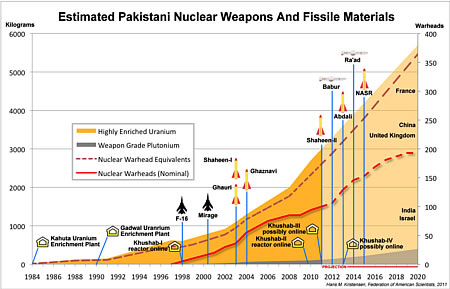

|

| Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal has doubled since 2004 and could double again in the next 10 years if the current trend continues, according to the latest Nuclear Notebook. Click on chart to download full size version. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

The latest Nuclear Notebook on Pakistan’s nuclear forces is available on the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists web site. Since our previous Notebook on Pakistan in 2009 there have been several important developments.

Based on our own estimates, official statements, and fissile material production estimates produced by the International Panel of Fissile Materials, we conclude that Pakistan’s current nuclear weapons stockpile of 90-110 warheads might increase to 150-200 within the next decade. This would bring the Pakistani stockpile within range of the British stockpile, the smallest of the original five nuclear weapon states, but still far from that of France (despite some recent news reports to the contrary).

This development is precipitated by the anticipated introduction of several new nuclear delivery systems over the next years, including cruise missiles and short-range ballistic missiles. The capabilities of these new systems will significantly change the composition and nature of Pakistan’s nuclear posture.

India is following this development closely and is also modernizing its nuclear arsenal and fissile material production capability. The growing size, diversity, and capabilities of the Pakistani and Indian nuclear postures challenge their pledge to only acquire a minimum deterrent. Bilateral arms control talks and international pressure are urgently needed to halt what is already the world’s fastest growing nuclear arms race.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.