Conventional Deterrence of North Korea

The debate over whether North Korea could be deterred was eclipsed by the onset of negotiations in 2018. Yet, the last three years have been marked by rapid advancements in the regime’s military capabilities and apparent evolution in its military strategy, which now relies on the threat of preemptive attacks against allied conventional forces to limit damage to the regime. Many of the standard assumptions that have underwritten U.S.-ROK deterrence posture are now obsolete. The deterrence balance on the peninsula is now between DPRK nuclear forces and allied conventional forces. Allied deterrence posture that depends on the threat of nuclear use or invasion will be insufficient to deter the regime from attempting to impose a fait accompli to forcibly achieve limited objectives. The alliance must place conventional deterrence at the center of its planning to ensure that U.S. conventional forces can effectively supplement South Korea’s ability growing ability to defend itself from limited aggression. The proposed posture requires closer coordination and additional capability, a difficult but necessary step at a time when the alliance faces severe friction.

A Rare Look Inside a Russian ICBM Base

It’s relatively easy to observe Russian missile bases from above. It’s much harder to do it from inside.

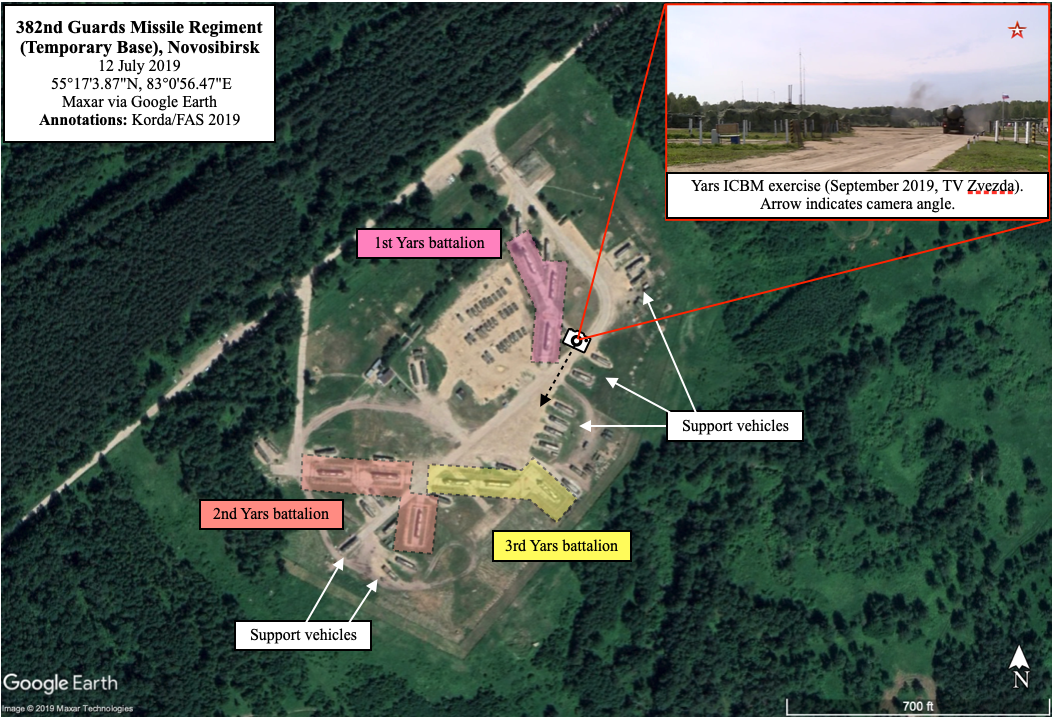

But in September, the Russian Ministry of Defense released a rare video of a command exercise which features mobile SS-27 Mod 2 “Yars-S” ICBMs driving around their base near Novosibirsk.

The base itself, which is likely to be the temporary home of the 382nd Guards Missile Regiment, has a relatively strange layout, which makes it significantly easier to identify. Unlike other Yars bases in the 39th Guards Missile Division (which houses the 382nd Regiment)––or even across the region––this base does not have any vehicle garages. Instead, the Yars launchers and support vehicles are simply parked out in the open, usually under camouflage (although they occasionally mix up their camouflage, weirdly replacing the forest green with snowy white well before any snow actually touches the ground!).

The September video shows Russian troops uncovering their ICBMs, taking them out for a spin, and eventually tucking them back in under camouflage blankets.

This regiment––along with the other two Novosibirsk bases associated with the 39th Guards Missile Division––recently completed its long-awaited conversion to Yars ICBMs from its older SS-25 Topol ICBMs. These new missiles are clearly visible in both satellite imagery and in the Ministry of Defense video.

During its conversion, the regiment was moved from its previous base (55°19’2.72”N, 83°10’6.70”E) to this temporary location, while the old base was dismantled in preparation for a substantial upgrade to build new missile shelters for the Yars ICBMs, as well as service and administrative buildings. Construction stalled for several years, possibly because of budget cuts, but has recently picked up again. Once completed, the 382nd Guards Missile Regiment presumably will be relocated back to its old base.

As we write in the Nuclear Notebook, Russia continues to retire its SS-25s at a rate of one or two regiments (nine to 18 missiles) each year, replacing them with newer Yars ICBMs. It is unclear how many SS-25s remain in the active missile force; however, we estimate that it is approximately 54. The remaining two SS-25 equipped divisions will start their upgrades to Yars in 2020, with the SS-25s expected to be fully retired in 2021-2022, according to the commander of Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces.

Read more about Russia’s nuclear forces in the 2019 Russian Nuclear Notebook, which is always freely-accessible via the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Urgent: Move US Nuclear Weapons Out Of Turkey

Should the U.S. Air Force withdraw the roughly 50 B61 nuclear bombs it stores at the Incirlik Air Base in Turkey? The question has come to a head after Turkey’s invasion of Syria, Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian leadership and deepening discord with NATO, Trump’s inability to manage U.S. security interests in Europe and the Middle East, and war-torn Syria only a few hundred miles from the largest U.S. nuclear weapons storage site in Europe.

According to The New York Times, State and Energy Department (?) officials last weekend quietly reviewed plans for evacuating the weapons from Incirlik. “Those weapons, one senior official said, were now essentially Erdogan’s hostages. To fly them out of Incirlik would be to mark the de facto end of the Turkish-American alliance. To keep them there, though, is to perpetuate a nuclear vulnerability that should have been eliminated years ago.”

That review is long overdue! [Actually, I’ve heard there have been several reviews and a lively internal debate since the 2016 coup attempt.] Some of us have been calling for withdrawal for years (see here and here), but officials have resisted saying it wasn’t as bad as it looked and that the deployment still served a purpose. They were wrong. And by waiting so long to act, the United States has painted itself into a corner where the choice between nuclear security and abandoning Turkey has become unnecessarily stark and urgent.

The situation is even more untenable because Incirlik in just a few years is scheduled to receive a large shipment of the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, which would be a recommitment to nuclear deployment in Turkey.

This year is the 60th anniversary of the first deployment of nuclear weapons to Turkey. It is time to bring them home.

Nuclear Weapons At Incirlik

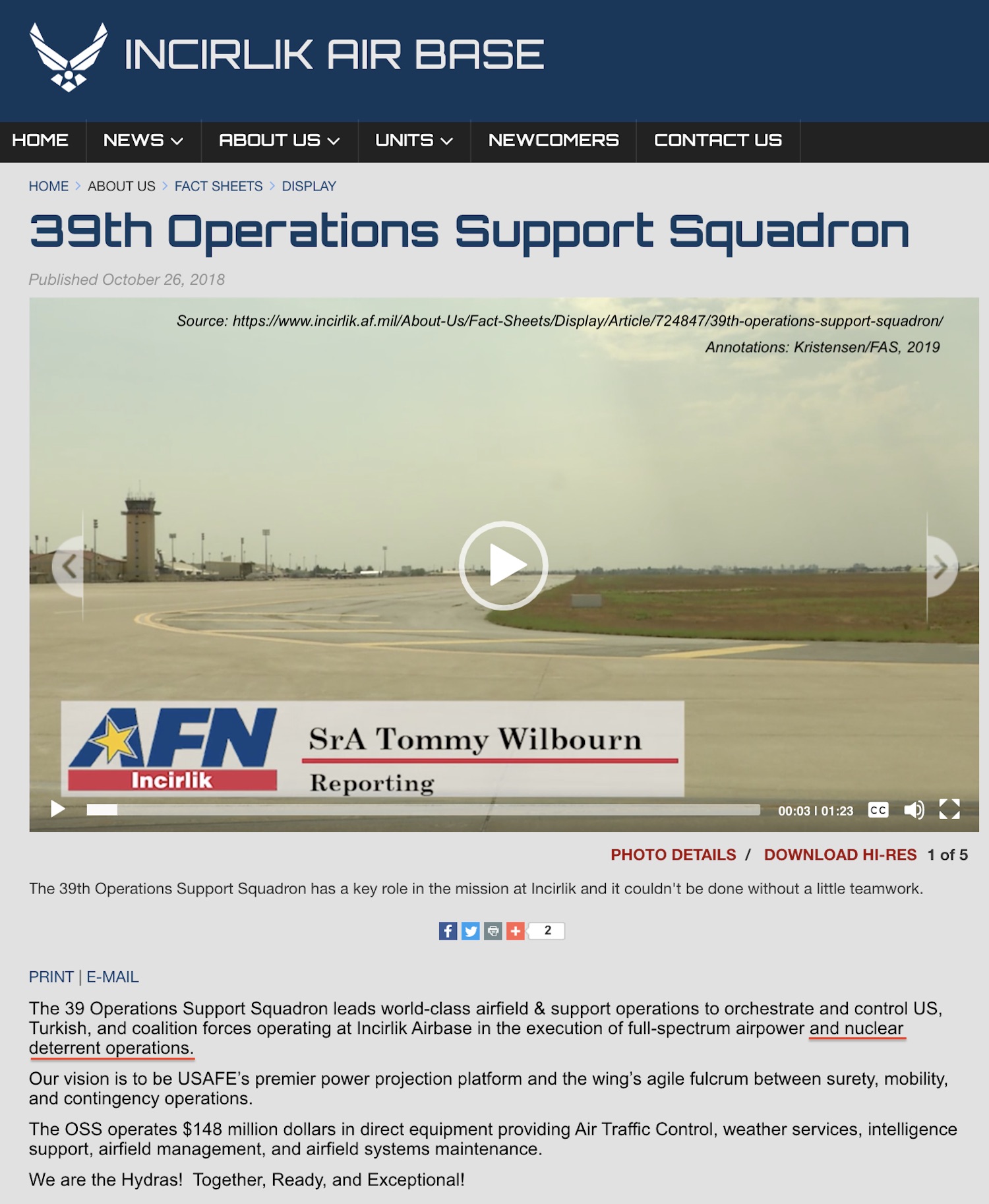

The specific reference in the New York Times article made by officials to nuclear weapons at Incirlik is the most recent and authoritative confirmation that nuclear weapons are still stored at the base. That confirms what I have been hearing and sources at US Air Forces Europe confirmed the report, telling William Arkin the weapons are still there. There have been rumors the weapons were removed after the coup attempt in 2016 (and some really bad disinformation that they had been moved to Romania). All of those rumors were wrong. An article on the official Incirlik Air Base web site even confirms that the mission of the 39th Operations Support Squadron is “to orchestrate and control US, Turkish, and coalition forces operating at Incirlik Airbase in the execution of full-spectrum airpower and nuclear deterrent operations” (emphasis added). Given that the article will likely be removed now that I have pointed this out, it is reproduced in full below:

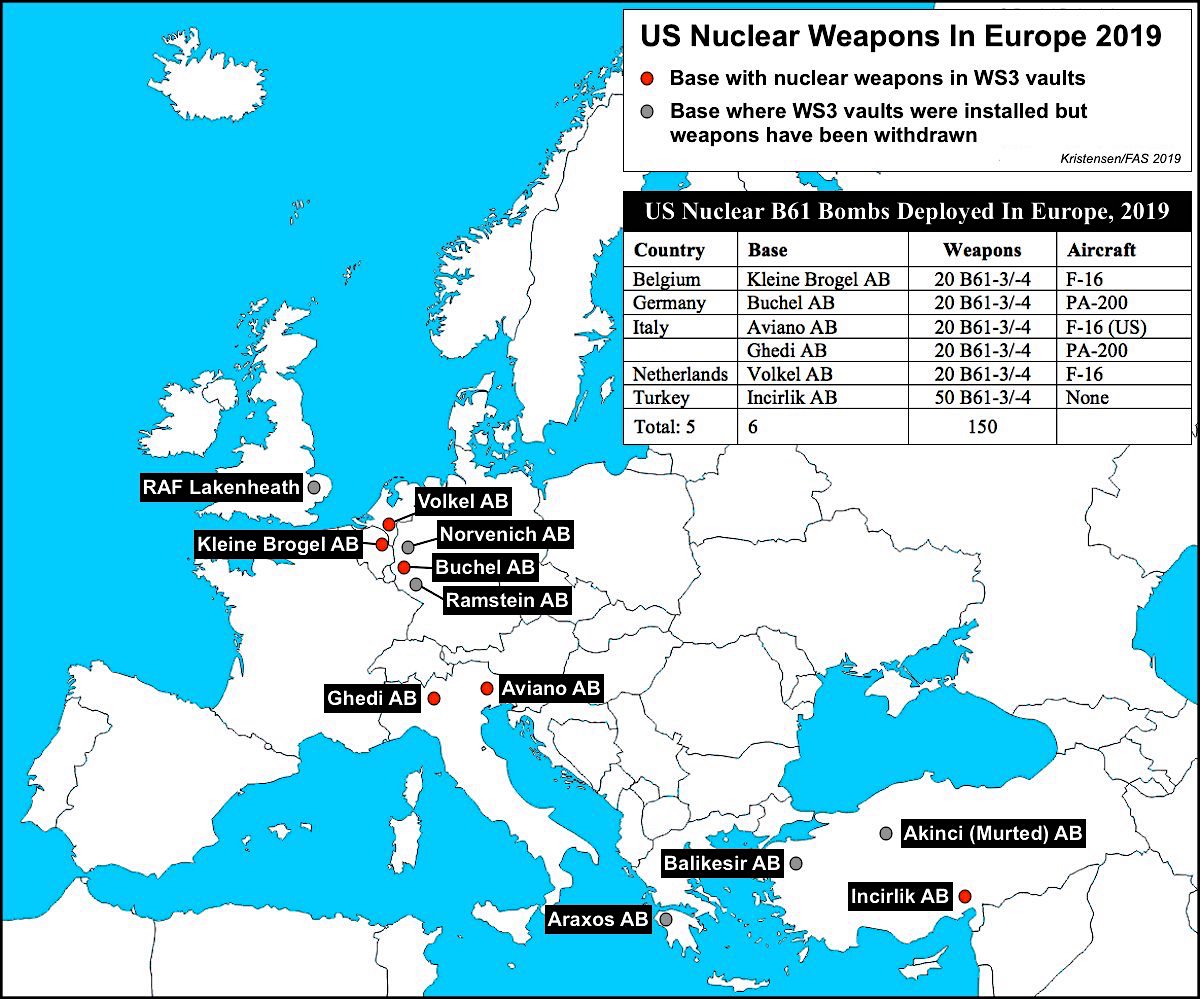

I have estimated for the past several years that the Air Force stores about 50 B61 nuclear gravity bombs at Incirlik, one-third of the 150 nuclear weapons currently deployed in Europe (see figure below). This estimate has been used by a wide range of news reports and commentators. The number of bombs at Incirlik has decreased over the past two decades from 90 in 2000. In those days, 40 of the 90 bombs were earmarked for delivery by Turkish F-16s. Those 40 bombs used to be stored in 6 vaults at both Akinci AB and Balikesir AB (20 at each) until they were moved to Incirlik when the US Air Force withdrew its Munition Support Squadrons from the Turkish bases in 1996. The 40 “Turkish” bombs remained at Incirlik until around 2005 when they were shipped back to the United States as part of the Bush administration’s unilateral nuclear reduction in Europe.

The US Air Force stores 150 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Click on map to view full size.

The remaining 50 bombs are for use by US jets, even though Turkey never allowed the US Air Force to permanently base fighter-squadrons at Incirlik. Jets would have to fly in during a crisis to pick up the weapons or they would have to be shipped to other locations before use. As a result, the nuclear posture at Incirlik has been more a storage site than a fighter-bomber base during the past two decades.

Although the Turkish participation in the NATO nuclear sharing mission was lessened (some would say mothballed) by the withdrawal of the “Turkish” weapons, the Turkish F-16s continued to serve a nuclear role. Despite local reports that F-16s never had a nuclear role, the US Air Force in 2010 informed Congress that “Turkey uses Turkish F-16s to execute their nuclear mission,” and that some of the F-16s would be upgraded to be able to deliver the new B61-12 bomb until the F-35A could take over the nuclear strike mission in the 2020s. That is now not going to happen after the Trump administration canceled the F-35 sale.

In 2015, satellite images revealed construction of a new security perimeter around most of the aircraft shelters with nuclear weapons storage vaults. Of the 25 shelters that originally were equipped with vaults, only 21 were included in the new security area with a capacity to store up to a maximum of 84 nuclear bombs. Normally only about two bombs are stored in each vault, for a total of inventory of 40-50 bombs at Incirlik.

The nuclear weapons mission areas at Incirlik AB include the “NATO Area” where nuclear weapons are stored and the nuclear weapons maintenance unit that manages the underground storage vaults

As recently as last month, Vice Chief Staff of the Air Force, Gen. Stephen W. Wilson, visited Incirlik and was given tours of the various functions and facilities at the base. One of these was Protective Aircraft Shelter H-2 inside the “NATO Area” where he spoke to members of the 39th Security Force that protects the nuclear weapons (see below). He was likely also shown the inside of the shelter and the weapons in the vault.

Last month, the Air Force Chief of Staff was taken to a nuclear weapons storage shelter at Incirlik AB. Click on image to view full size.

Recent Activities

If the Air Force decided to withdraw the B61 bombs from Incirlik, it would look pretty much like activities captured by Maxar’s satellites in 2019 and 2017. Those images show what appears to be either actual nuclear weapons movements or training to remove them.

One photo from March 22, 2019, shows a C-17 transport aircraft – likely from the 4th Airlift Squadron of the 62nd Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington – parked right outside the main gate to the NATO Area. The 4th Airlift Squadron, which is the only unit in the Air Force that is qualified to airlift nuclear weapons, flies Prime Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) and Emergency Nuclear Airlift Operations (ENAO) missions (see images below).

The satellite image shows the C-17 and gate area surrounded by armored vehicles and armed guards of the 39th Security Force as well as technicians to protect and carry out the weapon movement. One of the unique vehicles seen is an 18-meter truck lined up with the loading pad of the C-17. The same type of truck can be seen parked at the weapons maintenance unit building a few months later (see image below).

This Maxar satellite image acquired via Earth Watch shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in March 2019. Click on image to view full size.

Another set of Maxar satellite photos of a possible nuclear weapons movement or exercise is from December 2017. A Nuclear Security Inspection that year (and 2014) reportedly included weapons emergency evacuation drills. The scenario on the 2017 image is similar to that on the 2019 image: a C-17 parked outside the gate, security vehicles surrounding the scene, and transporters for moving weapons. But the 2017 photos are unique because they were taken moments apart as the satellite passed overhead. As a result, movements become visible: On the first image, a possible weapons trailer towed behind a truck in a column of armored security vehicles is moving toward the outer gate of the NATO Area. On the second photo, the column has passed through the gate onto the tarmac and the towed trailer is turning toward the rear of the C-17. The aircraft shadow shows the loading ramp is open and ready to receive the weapons (see image below).

This unique double-image shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in December 2017. Click on image to view full size.

The Task At Hand: Withdraw The Weapons!

The B61 nuclear bombs at Incirlik should have been withdrawn long ago but tradition, Cold War thinking, and bureaucratic inertia prevented officials from doing the right thing. Now things have come to a head where the United States is faced with the choice of securing its weapons or be seen as abandoning Turkey.

Withdrawing the weapons does not, of course, mean the United States is abandoning Turkey. That relationship is already in serious trouble and keeping the weapons at Incirlik based on the idea that it will somehow counterweight Turkey’s further drift away from NATO is probably an illusion. That boat seems to have sailed; the relationship is likely to deteriorate whether or not there are nuclear weapons at Incirlik. That is the reality the Air Force must relate to now.

Another argument against withdrawal will be that moving them out of Turkey will cause the other members of the so-called nuclear sharing arrangement (Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy) to question why they should continue to store U.S. nuclear weapons. Withdrawal from Turkey could, so the argument goes, trigger a domino effect of withdrawal from other countries as well.

But the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear bombs from Greece in 2001 and from England five years later did not cause the other countries to demand withdrawal as well or the collapse of NATO. If they truly believe deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons is important for NATO security, then they will stay. If the mission falls with withdrawal from Turkey, then they obviously don’t think it’s important and the weapons should be withdrawn from all the countries anyway. The U.S. extended deterrence posture in Europe can adequately be maintained with advanced conventional forces backed up by strategic forced in the background.

The B61 bombs at Incirlik could easily be dispersed to empty storage vaults in the other countries. Space is not a problem. There are a total of 96 empty weapon slots in the active WS3 vaults in Belgium, Germany, Holland, and Italy. Moreover, there are 25 empty and inactive WS3 vaults with room for 100 bombs at RAF Lakenheath. But public and parliamentary opposition would likely prevent increasing the number of nuclear bombs stored in those countries. If the order goes out to evacuate Incirlik, it seems more likely the bombs would be returned to the United States.

There will be some people who will argue that deteriorating relations with Russia and Moscow’s alleged increased reliance on a so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy of using tactical nuclear weapons first prevent the United States from reducing – certainly withdrawing – its tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. Those are curiously the same people who also argue that the United States should deploy a new low-yield warhead on its strategic submarines and a new nuclear cruise missile on its attack submarines to better counter Russian tactical nuclear weapons – a thinking that was recently endorsed by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. That seems to signal to the European allies that the United States actually no longer believes the deployment of B61 nuclear bombs in Europe is credible and that other and better weapons are needed.

Whatever one might think about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, Turkey is no longer an acceptable location. Erdogan’s confrontational and authoritarian leadership is rapidly undermining Turkey’s status as a reliable NATO ally, and the deteriorating security situation in the region presents a real physical threat to the weapons at Incirlik. That threat is real and the U.S. military sees it as real. So much so that an extra security force squadron deployed to Incirlik from Aviano Air Base in Italy to beef up nuclear security in response to “regional turmoil and government instability” according to USAF source, and Ohio Army National Guard military police reportedly were dispatched to Incirlik specifically to increase base security.

The security threat to the weapons at Incirlik is urgent and the continued deployment of nuclear weapons at the location is unjustifiable and incompatible with U.S. nuclear security standards. If you don’t believe that, ask yourself this question: If there were no U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey and someone asked for them to be deployed to Incirlik, would the Pentagon approve?

I doubt it. It’s time to face reality and withdraw the weapons from Turkey before they have to be evacuated under fire.

Additional information:

- US nuclear weapons, 2019

- Tactical nuclear weapons, 2019

- Upgrades At US Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk (2015)

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

New START Treaty Data Shows Treaty Keeping Lid On Strategic Nukes

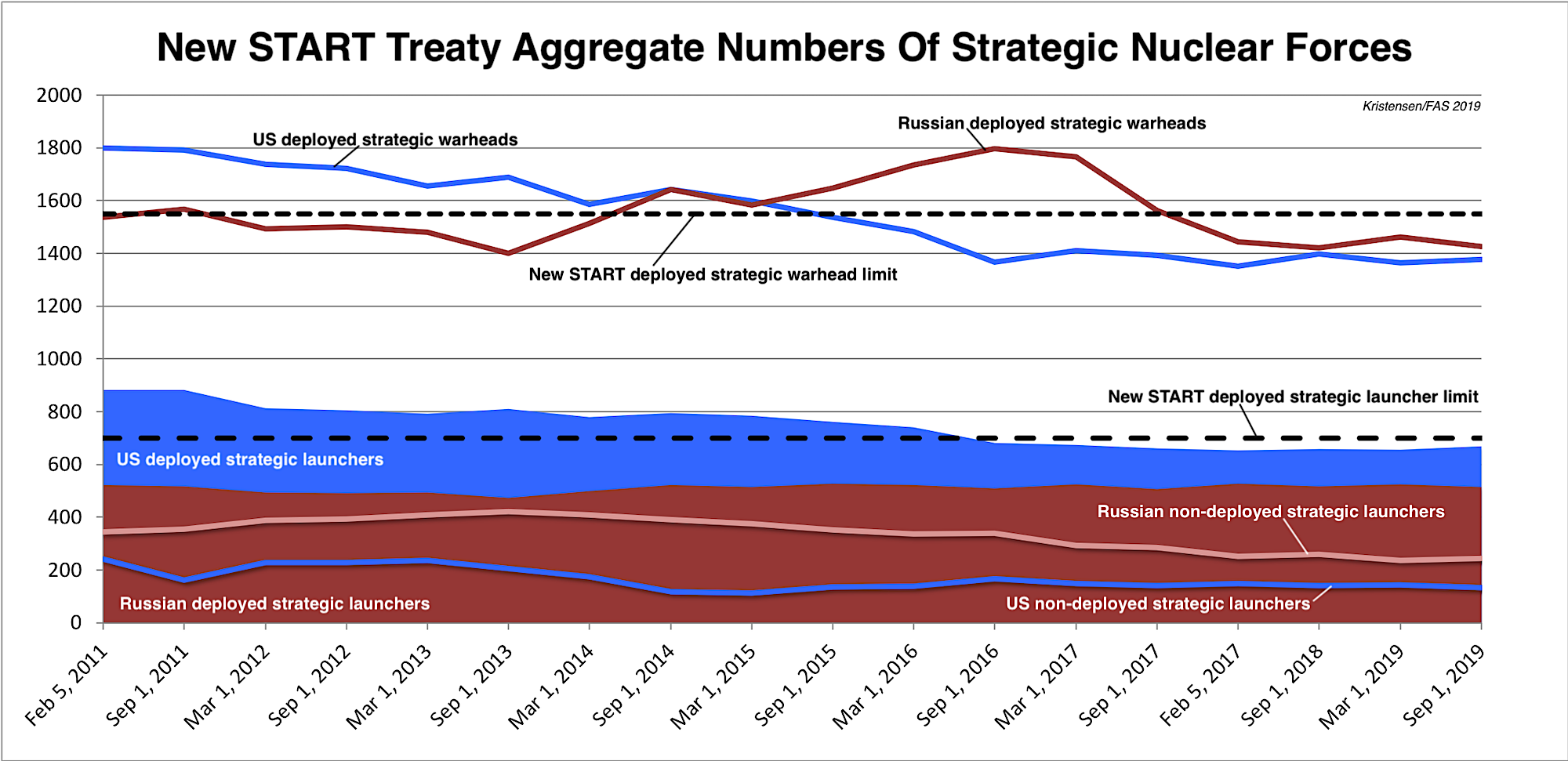

The latest data on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces limited by the New START treaty shows the treaty is serving its intended purpose of keeping a lid on the two countries’ arsenals.

The data was published by the State Department yesterday.

Despite deteriorating relations and revival of “Great Power Competition” strategies, the data shows neither side has increased deployed strategic force levels in the past year.

The data set released is the last before the New START treaty enters its final year before it expires in February 2021. The treaty can be extended for another five years by the stroke of a pen, but arms control opponents in Washington and Moscow are working hard to prevent this from happening. If they succeed, the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals will be completely unregulated for the first time since the 1970s.

By The Numbers

The latest data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,181 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,802 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). That is very close to the combined forces they deployed six months ago. These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 513 deployed strategic launchers with 1,426 warheads. That’s a slight decrease of 11 launchers and 3 warheads compared with March 2019. Russia is currently 187 launchers and 124 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 668 strategic launchers with 1,376 warheads attributed to them, according to the new data, or a slight increase of 12 launchers and 11 warheads compared with March 2019. The United States is currently 32 launchers and 174 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since March 2019 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the force structure or threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,330 warheads for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,500 and 6,185, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement). Both sides could upload many hundreds of warheads extra on their launchers if New START was allowed to expire.

Build-Up, What Build-Up?

Both Russia and the United States are engaged in significant modernization programs to extend and improve their strategic nuclear forces. So far, however, these programs largely follow the same overall structure and are unlikely to significantly change the strategic balance of those forces. The New START data shows the treaty is serving to keep a lid on those modernization plans.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not yet deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). The Trump administration is complaining these new weapons should be included in the treaty. A third weapon, an ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard, is close to initial deployment and will be accountable under the treaty but would likely replace existing deployed warheads. All of these weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces and the new data shows it does not appear to try to close the significant gap that exists in the number of deployed strategic launchers – 155 in US favor by the latest count (up 23 launchers from March 2019). To put things in perspective, 155 launchers are the equivalent of an entire US ICBM wing, or more than seven Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines fully loaded, or more than twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would certainly be complaining about a Russian advantage. Given this launcher disparity, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers (down 12 since March 2019).

Instead of trying to close the launcher gap, Russia is compensating for the disparity by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles to be able to keep overall parity with the United States. Since 2016, the New START data indicates that Russia has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian deployed strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could potentially – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed strategic launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits or the treaty was allowed to expire in 2021. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs. Significantly increasing the force structure, however, would take decades to achieve because both sides have based their long-term planning on the assumption that the New START force level would continue.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,” as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US to a conventional role cannot be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility, however, and the US insists the conversions have been carried out in accordance with the treaty provisions that Russia agreed to when it signed the treaty.

The Russia complaints about converted launchers and the US complaints about incorporating new strategic weapons are issues that should be resolved in the treaty’s Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

The US complains new Russian strategic weapons should be included in New START and Russia complains it can’t verify irreversibility of converted US launchers

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 313 onsite inspections (25 this year) and 18,803 notifications (2,387 last 12 months). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

What Now?

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: New START is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian complaints that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

This all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, that’s what they’ll get.

It is essential that Russia and the United States decide now to extend the New START treaty. Without it, the two sides will switch into a worst-case-scenario mindset for long-term planning of strategic forces that could well trigger a new nuclear arms race.

Additional information:

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russia nuclear forces, 2009

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces, 2019

- Status of world nuclear forces

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Military Might Takes Center Stage at Chinese 70-Year Anniversary Parade

The Chinese leadership used the 70-year anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China to display a dizzying amount of military hardware during a parade in Beijing (see officially narrated video here; higher-quality video is here. Beijing is rapidly becoming the new Red Square when it comes to military displays. On the nuclear side, the display included three ICBMs, an IRBM, a SLBM, and bombers.

The parade for the first time included the long-awaited DF-41 road-mobile ICBM. A total of 16 TELs were displayed (18 have been seen), launchers that Xinhua said came from two brigades. The display of the DF-41 happens more than two decades after it was first reported in development by the Pentagon in 1997. The DF-41, which is China’s first road-mobile ICBM capable of carrying MIRV, was described by the official parade commentator as to “balancing the power and security victory.”

The DF-41 was seen operating at the Jilantai training area in April 2019 and is currently being integrated into the PLARF. With an estimated range similar to the 13,000 kilometers of the silo-based DF-5, the DF-41 will initially complement but eventually probably replace the older liquid-fuel missile. China is currently building what appears to be silos in the Jilantai area that may eventually be intended for the DF-41.

The DF-31AG ICBM also reappeared. Xinhua described it as a “second-generation” nuclear missile with “high mobility and precision.” The 16 TELs displayed were said to be from two brigades. The official parade speaker described it as a “modified DF-31A” rather than a new missile. US intelligence has consistently described the DF-31A as a single-warhead ICBM, which also seems to be the case for the DF-31AG. DF-31AGs were also seen operating in Jilantai in April. The new DF-31AG TEL will likely replace the less maneuverable DF-31A (and DF-31) TELs.

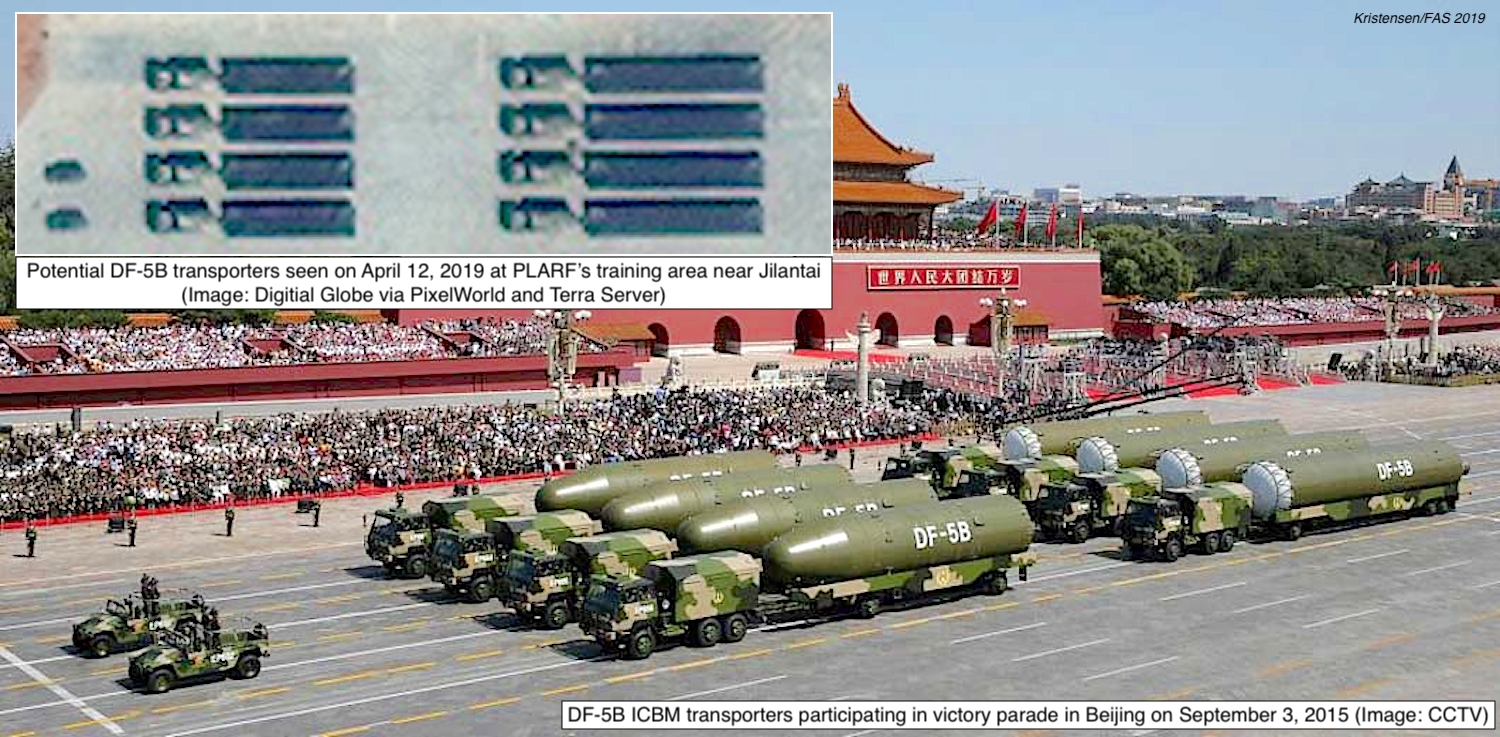

The DF-5B silo-based ICBM was also displayed, a repeat of the 2015 parade. Xinhua said the four-missile formation came from a single missile brigade established in the early 1960s that over the years has launched “dozens” of missiles. The official parade commentator reaffirmed the DF-5B is capable of carrying multiple warheads. The DF-5B was also seen operating in Jilantai in April. There are about 20 DF-5A/B ICBMs deployed. The much-rumored DF-5C did not appear.

The DF-26 dual-capable IRBM reappeared with 16 TELs described by Xinhua to come from “two missile troops.” First displayed in 2016, there are already 65-80 DF-26s deployed. The missile was seen operating in Jilantai in April.

The biggest surprise at the parade was probably the new DF-17 ballistic missile-launched hypersonic glide-vehicle, which made its first public appearance with 16 launchers. The DF-17 appears to use a modified DF-16 TEL and is possibly boosted by a DF-16 first stage. The US intelligence community has suggested the DF-17 might be dual-capable but the parade speaker described it as “conventional.”

The parade also included a unique display of JL-2 SLBMs, the first time the weapon has been publicly displayed. A total of 12 JL-2s were shown, corresponding to a full load of one of China’s six Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs. Each JL-2 can carry one warhead. China is developing a JL-3 for its next-generation Type 096).

The parade also saw the overflight of the H-6K and H-6N bombers, although they had to fly through a thick haze of air pollution that has plagued the Beijing area for years. Xinhua called them “long-range strategic bombers” and said they are “under the command of a division of the aviation forces of the People’s Liberation Army’s air force that has carried out many major missions, including air-dropping atomic and hydrogen bombs.” The official mentioning of a nuclear mission is interesting because of reports that Chinese bombers have recently been reassigned a nuclear strike mission. The H-6N is thought to be intended to carry an air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM), a modification of the DF-21 MRBM.

The effect of US missile defenses on Chinese military planning was palpable at this year’s parade. This included the two MIRV-capable DF-5B and DF-41 ICBMs as well as the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle. Although there are many rumors that the DF-41 will carry 10 MIRV, that is probably exaggerated. The objective of Chinese nuclear strategy is to ensure a secure retaliatory deterrent and penetrate US missile defenses, not to maximize the number of warheads, so the number of MIRV will likely be lower, perhaps three per missile.

The challenge of using an overstocked military parade to demonstrate China’s peaceful intensions was evident in several commentators. The official parade commentator reminded that China’s missiles are “deployed in the mountains and the oceans in defense of national security and world peace.” And the Global Times front-page coverage was balanced by a selection of editorials, reviews, and comments that reminded of China’s “peaceful intent,” “world peace” and “stability,” and that there’s “no need to overreact.”

Additional background about Chinese nuclear forces:

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2019

- FAS Blogs about Chinese nuclear forces

- Podcast with CSIS’ ChinaPower

- Podcast with Ploughshares Fund

- FAS Overview: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

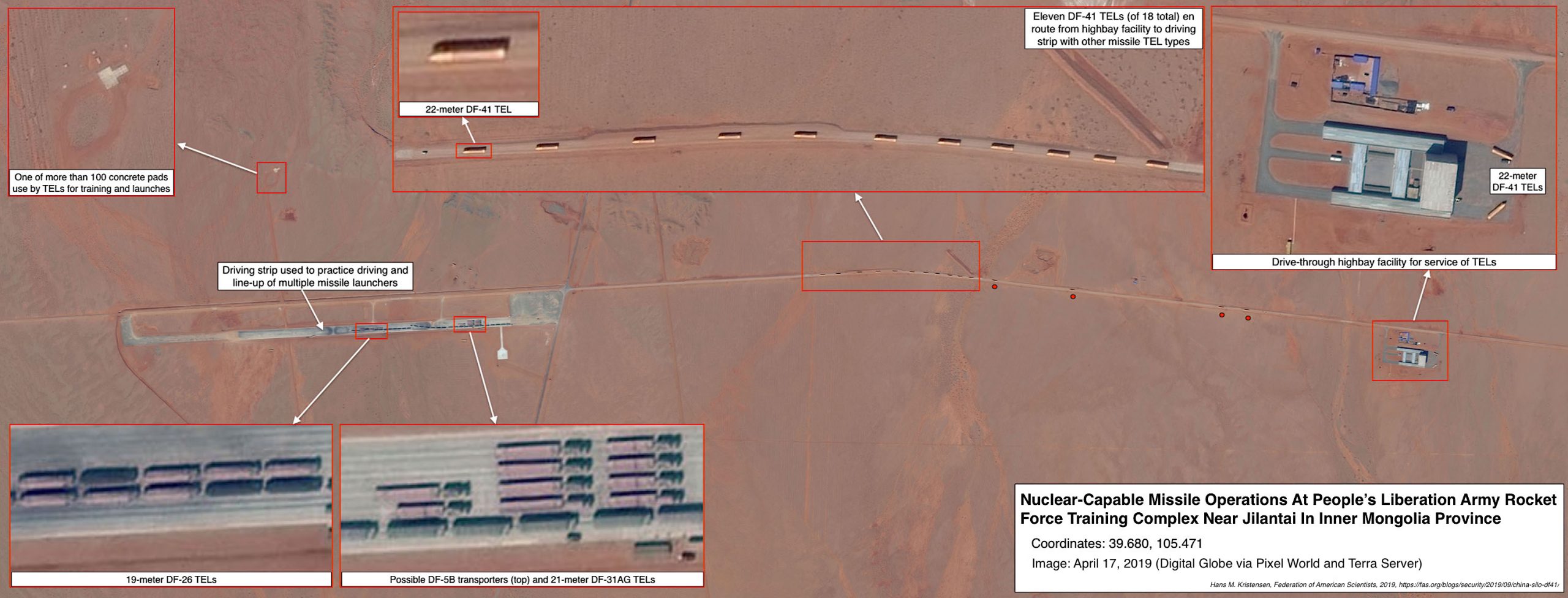

New Missile Silo And DF-41 Launchers Seen In Chinese Nuclear Missile Training Area

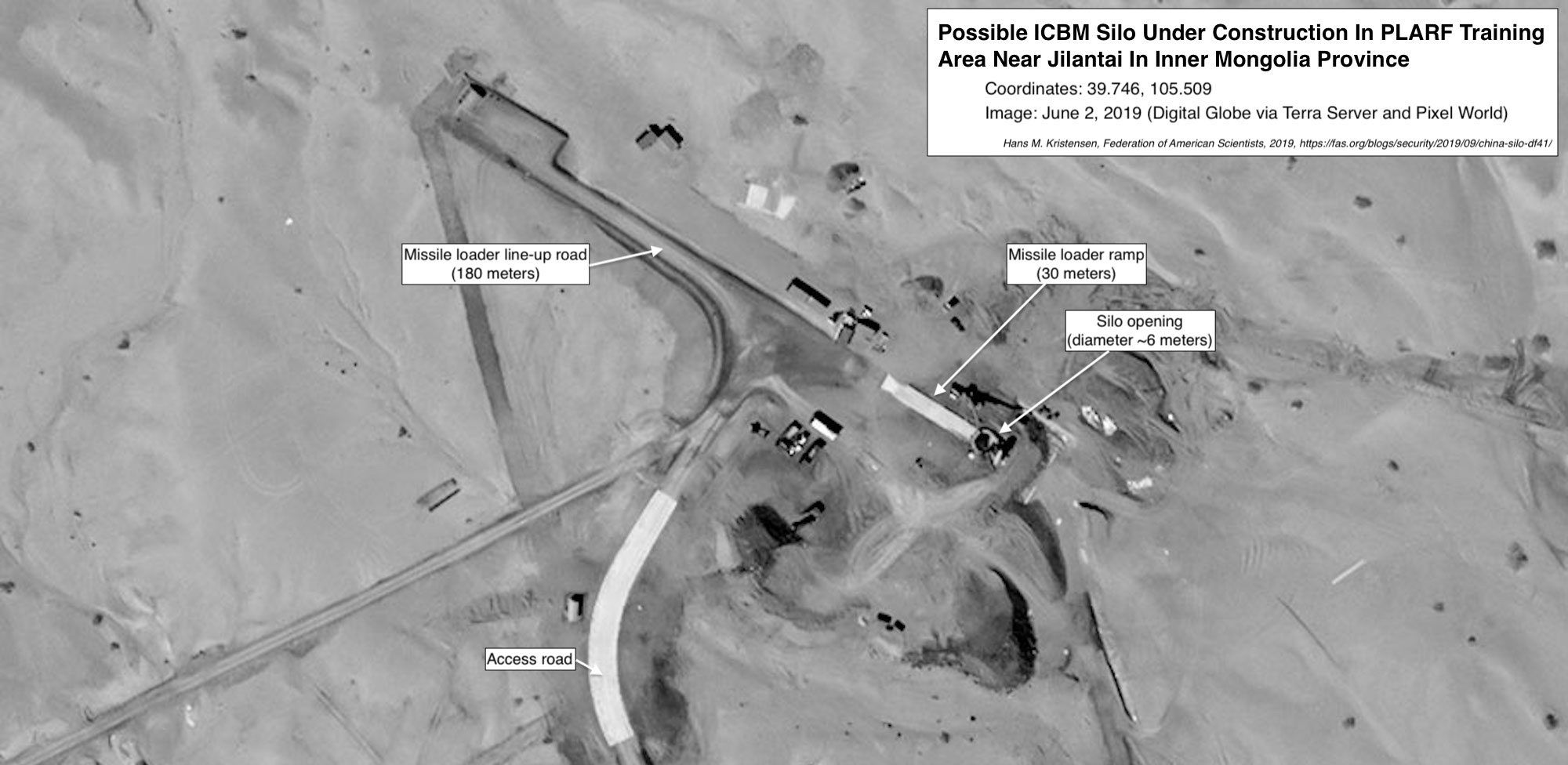

Newly acquired satellite photos acquired from Digital Globe (Maxar) show that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) is building what appears to be a new type of missile silo in the missile training area near Jilantai, possibly for use by a new ICBM.

The photos also show that 18 road-mobile launchers of the long-awaited DF-41 ICBM were training in the area in April-May 2019 together with launchers for the DF-31AG ICBM, possibly the DF-5B ICBM, the DF-26 IRBM, and the DF-21 MRBM.

Altogether, more than 72 missile launchers can be seen operating together.

China is in the middle of a significant modernization of its nuclear weapons arsenal and the Jilantai training area, which has been constructed since 2014, appears to play an important part in that modernization effort.

A New Type of Missile Silo?

The most surprising new development in the training area is the construction of what may be a new type of missile silo. I want to emphasize that there is no official confirmation the structure is a silo, but it strongly resembles one. If so, it is potentially possible it could be part of a Chinese effort to develop the option to deploy some of its new solid-fuel road-mobile ICBMs – possible the DF-41 – in silos. According to the 2019 Pentagon report on Chinese military developments, “China appears to be considering additional DF-41 launch options, including rail-mobile and silo basing.”

Construction of the silo began in June 2018. Initially, a roof was built over it to conceal details, but in May 2019 the roof was removed exposing the silo to satellite photography (see image below).

The layout of the Jilantai silo is very different from the silos seen at Wuzhai. Those silos, which are thought to be similar to about 20 operational silos hidden in the mountains of the Henan and Hunan provinces for use by the liquid-fuel DF-5A/B ICBMs, consist of a rectangular retractable lid covering the silo on a concrete pad. And they have large exhaust vents to protect the DF-5’s liquid fuel from the launch heat.

Instead, the Jilantai silo looks more like Russian ICBM silos. It is not yet complete but so far consists of what appears to be a 180-meter line-up path and a 30-meter missile loader pad next to the silo. The precise silo diameter is difficult to measure given the image resolution but appears to be 5-6 meters, which is smaller than the 8-9 meter diameter silos at Wuzhai. Moreover, the absence of exhaust vents hints the Jilantai silo might be intended for solid-fuel missiles.

The new silo design would offer a more efficient (and safe) missile loading. At the DF-5 silos, missiles are loaded by a crane, which hoists each stage off its transporter and lowers it into the silo. It is a cumbersome and lengthy procedure. Moreover, the DF-5 is propelled by liquid fuel that is stored separately and must be loaded before the missile can be launched. With the Jilantai silo design, however, the solid-fuel missile presumably would be brought in on a loader that backs up to the edge of the silo, elevates the missile, and lowers it into the silo in one piece (warhead payload is probably added later).

If the structure seen at Jilantai indeed is a new silo, it presumably would only be used for training. If the design is successful, it would likely be followed in the future by the construction of similar silos in China’s ICBM basing areas for use by operational missiles.

Extensive Missile Training

The Jilantai missile training area, which has been constructed since 2014 and is located in the south-western part of the Inner Mongolia province approximately 930 kilometers (578 miles) west of Beijing, has undergone significant changes since I described it in January. The central technical facilities continue to expand, TEL drive-through facilities are being added, and road-mobile launchers for China’s newest nuclear-capable ballistic missiles are seen more or less constantly training in the area.

This includes the new DF-41 ICBM that may be in the final phase before starting to deploy to operational PLARF brigades. The new DF-31AG ICBM is also training at Jilantai, as is the new DF-26 IRBM and the DF-21 MRBM (see image below).

Five types of ballistic missile can be seen operating in PLARF’s training area near Jilantai. Click on image to view full size.

All these systems are solid-fuel missiles on road-mobile launchers. But it is also possible – although at this point unconfirmed – that missile systems seen training at Jilantai include transporters for the silo-based DF-5B ICBM. This is a large silo-based missile that would not be able to launch from mobile launchers, but the images show unique two-part, truck-pulled trailers that resemble the DF-5B transports that were displayed at the Beijing parade in 2015 (see image below).

Vehicles operating at PLARF’s training center near Jilantai resemble DF-5B transporters shown in 2015 parade (click on image to view full size)

It must be underscored that there is no confirmation the trailers are for the DF-5B. In one photo some of the trailers are longer and it is unclear why DF-5B transporters would be training at Jilantai given there are no DF-5B silos in the area. If the towed trailers are not DF-5Bs, they could potentially be transporters of reload missile for the road-mobile launchers seen on the satellite photos.

The DF-41 ICBM

The satellite images indicate that the DF-41 TELs started training at Jilantai in April 2019 shortly after a new TEL drive-through highbay facility was completed (a second is under construction further to the north). There appear to be 18 DF-41 launchers. In one photo from April 17, 2019, for example, a column of 15 DF-41s can be seen making its way from the new drive-through facility (two additional DF-41s can still be seen at the facility and the 18th is probably still inside) to a parade strip to join an assembly of 18 DF-31AGs, 18 DF-26s, and 5 (possibly) DF-5B transporters.

Eighteen DF-41 TELs were operating at PLARF’s training site in April this year. Click on image to view full size.

The DF-41 has been in development for a very long time. The Pentagon’s annual report on Chinese military developments first mentioned the missile in 1997 and sensational news articles have claimed it has been operational for years. The DF-41 was widely expected to be displayed at the 2015 military parade in Beijing, but that didn’t happen. Nor was it displayed at the PLA’s anniversary parade in 2017.

The DF-41 training at Jilantai with the other launchers is probably part of the formal integration of the new missile into PLAFRF service, more than two decades after development began. It seems likely that the DF-41 will appear at the military parade in Beijing on October 1st. Indeed, two months after the training occurred at Jilantai, 18 DF-41 launchers (potentially the same 18) could be seen on a satellite photo of a military facility in Yangfang about 35 kilometers (22 miles) northwest of Beijing apparently getting ready for the October parade. The image first made its way onto the Internet on August 9th, when it was posted by the Twitter user @Oedosoldier. The image carried the user’s logo but it was a screenshot from a Digital Globe image on TerraServer dated July 4, 2019.

Chinese Nuclear Missile Outlook

The highly visible display and clustering of more than 72 missile launchers at Jilantai in April and May indicate the PLARF wants them to be seen and is keenly aware that satellites are watching overhead. This is Beijing’s way of telling the world that it has a capable and survivable nuclear deterrent.

Once they become operational, the 18 DF-41s seen on the satellite photos will probably form two or three brigades and join the existing force of 65-90 DF-5A/B, DF-31/A/AG, and DF-4 ICBMs.

Despite the visible display, there is considerable uncertainty about the future development of the Chinese nuclear arsenal, not least how many missiles China plans to deploy. It seems possible the DF-41 over time might replace one or more of the older ICBMs. It is potentially also possible that the DF-31AG will replace the older DF-31/A trailer launchers (the DF-31 is notably absent from the Jilantai images). And the old DF-4 seems likely to be retired in the near future.

The US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) stated in May this year that, “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile…” Part of that projection hinges on the DF-41 adding MIRV capability to the solid-fuel road-mobile missiles for the first time (the DF-5B is already equipped with MIRV).

Whether DIA’s projection comes true remains to be seen; the agency has been notoriously bad about Chinese nuclear warhead projections in the past. At this point, the Chinese arsenal is estimated to include roughly 290 warheads, a fraction of the U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals. To put things in perspective, all the launchers seen on the satellite photos make up less than half of the number of launchers in one of the three US ICBM wings.

Nonetheless, China is modernizing and increasing its nuclear arsenal. And the activities captured by commercial satellites at the PLARF’s training area west of Jilantai – operations of new DF-41 and DF-31AG ICBMs, the new dual-capable DF-26 IRBM, and the construction of what might be a new type of missile silo – are visual reminders of the important developments currently underway in China’s nuclear posture.

Additional background:

FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese nuclear forces, 2019

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

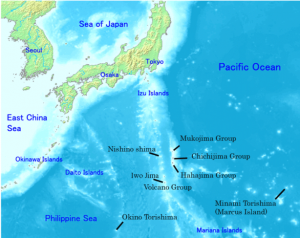

The History of U.S. Decision-making on Nuclear Weapons in Japan

Earlier this month, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper said he favored placing conventional intermediate-range missiles in Asia following the demise of the INF treaty. While Secretary Esper did not indicate where the missiles might be deployed, many security experts believe Japan to be the most likely candidate. The tight U.S.-Japan security alliance built from the American Occupation has historically set up Japan as an ideal staging ground for U.S. weapons systems. Though Secretary Esper and most proposals for intermediate-range missiles in Asia refer to conventional weapons, because of their strategic importance, many Japanese are likely to read these proposals as part of a long and politically fractious history of US weapons deployments to Japanese territory that included nuclear weapons.

Japan’s strategic location in the Pacific coupled with the heavy American influence on the emerging democracy made it an attractive option to host U.S. nuclear weapons during the Cold War. U.S. control of Japan’s southern island chain presented a strategic opportunity to forward deploy tactical nuclear weapons into an increasingly volatile Pacific region where war planners anticipated their increased military utility as they planned force postures to respond to the aftermath of the Korean War and the Chinese Civil War.

In 1959, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi first declared that Japan would neither develop nor permit nuclear weapons on its territory. This declaration formed the cornerstone of Prime Minister Eisaku Sato’s 1967 establishment of Japan’s “three non-nuclear principles” which promise not to process, produce, or permit the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan. The Diet formally adopted these principles through a resolution in 1971, though they are not legally binding. Prime Minister Sato, worried that the three non-nuclear principles were too binding on Japan’s defense posture, supplemented the policy in February 1968 with his “four pillars nuclear policy.” The four pillars were to promote peaceful use of nuclear power, to work toward global nuclear disarmament, to rely on the extended U.S. nuclear deterrent, and to support the three non-nuclear principles.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, U.S. officials often complained that Japan’s “nuclear allergy” imposed constraints on U.S. nuclear force posture. But despite the Japanese government’s public anti-nuclear stance, the nuances of the bilateral security relationship and treaty language emboldened the U.S. to deploy nuclear weapons to Japan in the mid-1950s. The occupation of mainland Japan ended in 1951 but the Treaty of San Francisco allowed the U.S. to maintain its control over Japan’s southern island chains, which include the islands of Okinawa, Iwo Jima, and Chichi Jima. War planners worried that compromised communication systems in a time of crisis would make emergency deployments and transfers of nuclear weapons difficult or impossible, so they sought to establish a forward deployed posture in the Pacific.

The bulk of the nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa at the Henoko Ordnance Ammunition Depot adjacent from Camp Schwab and the Kadena Ammunition Storage Area at Kadena Air Base, where SAC’s strategic bombers were based. Between 1954 and 1972, the bases on Okinawa hosted 19 different types of nuclear weapons. At the height of the Vietnam War, around 1,200 nuclear weapons were stored on Okinawa alone. A document declassified in 2017 shows that in 1969 Japan officially consented to the U.S. bringing nuclear weapons to Okinawa.

Every American president from 1952 onward remained publicly committed to the reversion of Okinawa, but was privately reluctant to initiate the hand-over. During the 1950s to mid-1960s, the Japanese were largely willing to accept reversion as a distant goal, in part because the U.S.-backed Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) that held power in the post-Occupation era was hesitant to challenge the U.S. on the issue. The Japanese government also recognized the security value of U.S. forces stationed in Okinawa, given Japan’s restraining pacifist constitution. However, in the late-1960s, pressure began to build from the Okinawans and the mainland Japanese establishment to return the island to Japan.

Prime Minister Sato first raised the issue with the U.S. in 1967 during talks with President Johnson. President Johnson responded that because of the 1968 election and the war in Vietnam, the U.S. would be unable to address reversion of Okinawa until 1969 at the earliest. In March of 1969, Henry Kissinger sent President Nixon a memo outlining the Japanese demands for reversion as well as the relevant military and political considerations. While the memo acknowledged that public demand within Japan for reversion was growing politically untenable for Prime Minister Sato, the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff were primarily concerned about the effect of reversion on nuclear storage and military activities such as B-52 operations against Vietnam. On nuclear storage, Kissinger wrote, “The loss of Okinawan nuclear storage would degrade nuclear capabilities in the Pacific and reduce our flexibility.”

Top secret agreement allowing the U.S. to maintain emergency reactivation of nuclear weapons storage on U.S. bases in Okinawa. (Image courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists.)

While the Joint Chiefs of Staff wanted the Nixon Administration to push for continued nuclear storage post-reversion, Kissinger wrote that it was unlikely that the Japanese Diet would support it in face of growing public dissatisfaction, even if Prime Minister Sato agreed. Kissinger added that “…in the slim possibility that Japanese agreement to nuclear storage is obtained, we must recognize that the Japanese proponents of this position view this as the opening wedge for an independent Japanese nuclear force.” Kissinger recommended that the U.S. return Okinawa to Japanese control and give up nuclear storage on the island in order to maintain basing rights, emergency nuclear storage rights, and full nuclear transit rights.

Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon agreed to the reversion of Okinawa in 1969. The agreement contained a secret clause permitting the U.S. to reintroduce nuclear weapons to its Okinawa bases in the case of an emergency. Okinawa was officially returned to Japan in 1972 and shortly after all U.S. nuclear warheads were withdrawn.

In 2016, the U.S. government officially declassified the fact that nuclear weapons were deployed to Okinawa before 1972. It also declassified “the fact that prior to the reversion of Okinawa to Japan that the U.S. Government conducted internal discussion, and discussions with Japanese government officials regarding the possible re-introduction of nuclear weapons onto Okinawa in the event of an emergency or crisis situation.”

While military planners believed the forward deployed nuclear weapons on Okinawa were useful in launching potential attacks against China, Russia, or Vietnam, they feared that in the event of nuclear war with either China or Russia, the U.S. bases on Okinawa would be attacked and destroyed early. In order to maintain a viable second salvo in the Pacific, nuclear weapons were also stored on the U.S.-controlled islands of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima. Iwo Jima became a fallback support station for the Far East Air Force, maintaining an unknown arsenal of atomic bombs that bombers could pick up for a second strike after dropping their first load on China or Russia. Chichi Jima was outfitted with W5 nuclear warheads for Regulus missiles to serve as a reload point for Regulus submarines if U.S. bases in Japan, Pearl Harbor, Guam, and Adak were destroyed in nuclear war.

The U.S. maintained nuclear weapons as well as other military support structures on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima into the mid-1960s. The Japanese had been pushing for return of Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima, and Okinawa since the mid-1950s and by 1964, U.S. diplomats in Tokyo also began pressuring Washington to return the islands to Japan, believing it vital to maintaining the cooperative and positive relationship the two countries shared. President Johnson, realizing that returning Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima would be a necessary concession in order to delay the return of the more strategically valuable island of Okinawa, reverted control of Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima to Japan in 1968. All nuclear weapons were removed from the islands by the time of their reversion, but the agreement President Johnson and Foreign Minister Takeo Miki signed would allow the U.S. to redeploy nuclear weapons to the islands in an emergency, upon consultation with the Japanese government. The U.S. government has not confirmed the deployment of nuclear weapons to Iwo Jima or Chichi Jima.

In addition to the nuclear weapons stored on Japan’s southern island chains, the U.S. allegedly stored nuclear weapons without the fissile cores on the Japanese mainland at Misawa and Itazuki airbases until 1965, avoiding by mere semantic technicality violation of Japan’s sovereignty and the integrity of Japan’s three non-nuclear principles. Nuclear armed naval ships were also allegedly allowed to transit Japanese waters and dock at mainland ports with tacit Japanese approval into the 1980s under an oral agreement the two countries made when Japan and the U.S. renegotiated the U.S.-Japan mutual security treaty in 1960.

While the U.S. government has never confirmed that U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons visited Japanese ports, there are two instances that support this claim. In 1974, retired Rear Admiral Gene La Rocque who formally commanded a flagship of the Seventh Fleet, testified before Congress that “any ship capable of carrying nuclear weapons carries nuclear weapons. They do not unload them when they go into foreign ports such as Japan or other countries.”

In 1981, Edwin O. Reischauer, former U.S. Ambassador to Tokyo during the 1960s, acknowledged in a newspaper interview that Japan was permitting U.S. naval ships carrying nuclear weapons to transit Japanese ports under the aforementioned oral agreement. According to Reischauer, American warships could bring nuclear weapons into Japanese waters and ports during routine visits but were not allowed to be unloaded or stored in Japan. The agreement allowed the same freedom to U.S. military planes carrying nuclear weapons.

Both disclosures incited protests from the Japanese public, which has adamantly maintained its anti-nuclear posture since U.S. atomic bombs destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. However, the historical record shows that the Japanese executive branch, dominated for decades by conservative LDP politicians, has at times acquiesced to asserted U.S. military necessities when it comes to nuclear weapons.

The coalitional Diet however has been historically reluctant to publicly support such domestically unpopular measures as allowing U.S. nuclear weapons into Japanese territory or developing an independent nuclear force. This reluctance extends to the possible deployment of conventional intermediate-range missiles being discussed among U.S. defense specialists today.

Policymakers and analysts should be aware of the complex history of US weapons deployments to Japan when discussing future deployments. It should be expected that proposed deployments will face similarly strong political reactions from activists, civil society groups, and communities who remember this history first hand.

Sunday’s US Missile Launch, Explained.

Arms Control Twitter has been abuzz since yesterday’s announcement that the United States had conducted a surprise launch of a Tomahawk missile on Sunday afternoon.

This wasn’t just your regular missile launch, however. It was a Tomahawk cruise missile launched from a ground-based Mark-41 Vertical Launch System (VLS), traveling to a distance of “more than 500 kilometers,” according to the Department of Defense.

In other words: a violation of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty––if the treaty still existed. It officially died on August 2nd, six months after both the United States and Russia announced suspensions of their respective treaty obligations. But the launch is an important walk-back of US security policy which for 32 years sought to curtail such weapons and instead, as we have written for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, makes the United States needlessly complicit in the INF’s demise and frees Russia from both the responsibility and pressure to return to compliance.

The launch was a bit of a surprise, but we knew it was coming. As early as March, US defense officials announced that DoD would test two missiles after the treaty expired on August 2nd: a ground-launched Tomahawk in August and a ground-launched ballistic missile in November.

Although the US test isn’t an official INF violation (because the treaty is dead), the timing and characteristics of the test itself has raised a few popular questions, which we will answer below:

The test took place only 16 days after INF died. That’s awfully quick to develop this missile configuration––does it mean that the United States was secretly violating the treaty this entire time?

No. Sunday’s test features an existing missile being launched from an existing missile launcher. It isn’t exactly a difficult engineering feat to cobble this together on short notice.

In fact, one of the most interesting things about the video is the haphazard nature of the test itself. As pointed out by Michael Duitsman, it looks like the Pentagon simply bolted a VLS launcher to a semi-trailer, planted a giant American flag nearby, and launched.

Why is everyone so worked up about the launcher?

This is where things get really interesting. The Mk-41 VLS launcher that was used to launch the Tomahawk is the same type of launcher that would be used to launch SM-3 interceptors from Aegis Ashore ballistic missile defense stations in Romania and Poland, once the latter station is completed.

For years, Russia has said that the US deployment of these ground-based Mk-41 VLS launchers to Europe constitutes an INF violation, because they could theoretically be used to launch Tomahawks over 500 kilometers. Legally speaking, this doesn’t hold water––Article VII, paragraph 7 of the INF Treaty states that in order for a launcher to be considered in violation of the treaty, it must actually conduct a ground launch of a prohibited missile. Since this never happened while the INF Treaty was in force, the Mk-41 VLS launchers weren’t in violation.

What’s more, the United States has consistently stated that although Mk-41s can launch Tomahawks, the ones deployed in Romania and Poland cannot. In December 2017, the State Department announced that “The Aegis Ashore Missile Defense System does not have an offensive ground-launched ballistic or cruise missile capability. Specifically, the system lacks the software, fire control hardware, support equipment, and other infrastructure needed to launch offensive ballistic or cruise missiles such as the Tomahawk.”

Perhaps this is true, perhaps it isn’t. But absent some kind of US transparency measure that offers visibility into the Aegis Ashore systems, Russia is forced to rely solely on an American promise. And for Putin, that’s simply not going to cut it. That being said, it’s also possible that no amount of transparency would ever have satisfied Putin, as his primary concern over Aegis Ashore appears to be directed at the general deployment of missile defenses in Europe, rather than their offensive potential.

So why did the United States do this test?

Both the timing and the nature of the test indicate that it’s driven primarily by political––rather than strategic––considerations. In all likelihood, the Trump administration asked the Pentagon to conduct an INF-violating test under a very tight timeline, and the quickest option also happened to be the most controversial. Also, any chance to give the INF Treaty’s corpse the middle finger is one that this administration will surely take.

Unfortunately, the test will almost certainly further entrench Russia’s suspicions of US missile defense deployments in Europe as well as enable the Kremlin to paint the United States as the problem rather than Russia.

And China can now feel completely vindicated in its decision not to join arms control talks or limitations. After all, why would it do so when it has far fewer nuclear weapons than both Russia and the United States, or consider limiting its INF-range missiles when Russia, India, and now the United States, are all developing such weapons?

With this flight test, the Trump administration has placed the United States firmly in the group of nations that it previously criticized for developing INF-range weapons. Instead of seeking to build international pressure against INF-missile proliferation, the Trump administration has needlessly surrendered the legal and political high-ground the United States previously had, and has now become part of the problem.

No Bret, the U.S. Doesn’t Need More Nukes

Last week, on the 74th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, many took time to reflect upon the destruction caused by the only uses of nuclear weapons in wartime. But not the New York Times’ Bret Stephens, who took the opportunity to argue in favor of building more nuclear weapons.

In an op-ed entitled “The U.S. Needs More Nukes,” Stephens laid out his case against arms control: “the bad guys cheat, the good guys don’t,” and all the while, the US nuclear arsenal is becoming “increasingly decrepit.”

It’s a simple narrative; it’s also false. In fact, Stephens’ article is largely littered with bad analogies, flawed assumptions, and straight-up incorrect facts about the nature of nuclear weapons and arms control.

As examples of arms control agreements where the “bad guys cheat” and the “good guys don’t,” Stephens cites the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (from which the United States withdrew in 2002), the Iran Deal (which was working until the United States withdrew last year), and the Treaty of Versailles (which famously isn’t an arms control agreement), among others. None of these involved significant cheating on the part of the “bad guys,” unless you count the Trump administration’s violation of the Iran Deal in 2018.

Stephens also cites the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty as a prime example of an arms control agreement gone wrong. Yes, it appears that Russia likely violated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty by developing and deploying a banned ground-launched cruise missile; however, as we’ve written previously, Trump’s decision to pull out of the treaty makes the United States needlessly complicit in its demise and frees Russia from both the responsibility and pressure to return to compliance. Contrary to Stephens’ thesis, when someone breaks the law, you shouldn’t throw away the law.

And contrary to the title of Stephens’ piece, the United States doesn’t need more nukes. As we explain in our latest US Nuclear Notebook, the Trump administration wants to develop two new ones––a low-yield warhead and a sea-launched cruise missile––both of which are dangerous, and neither of which are necessary. Aside from lowering the threshold for nuclear use, the “low-yield” aspect of the low-yield warhead is a misnomer; it’s roughly one-third the yield of the Hiroshima bomb that killed 100,000 people. And the new sea-launched cruise missile is a concept brought back from the dead: the United States had one until 2013, when the Obama administration retired it because it was pointless, wasteful, and politically controversial.

In addition to his well-established denialism of issues like systemic hunger, rape culture, and climate change, Stephens is known for his hawkish––and often inaccurate––takes on nuclear issues. In 2013, he claimed that the Iran Deal was worse than Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler in 1938. In 2017, he argued in favor of regime change in North Korea. Later that year, he derisively referred to ICAN––the group that won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work to ban nuclear weapons––as “another tediously bleating ‘No Nukes’ outfit.” In June, he wrote that “If Iran won’t change its behavior, we should sink its navy.” Remember, this is coming from a guy who awarded Iraq War architect Paul Wolfowitz “Man of the Year” in 2003 (The runners-up? Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Tony Blair, and George W. Bush).

Furthermore, in last week’s piece, he erroneously stated that Iran repeatedly violated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, a claim which the International Atomic Energy Agency—the international organization charged with monitoring Iran’s compliance––has continuously rebutted. Noticeably, Stephens linked to Mark Fitzpatrick’s work to back up his claim, but when Mark tweeted out that his article didn’t say anything of the sort, the link was changed. It now references David Albright of the Institute for Science and International Security, who is known for his hawkish views on Iran.

Stephens’ columns are clearly emphasizing ideology over accuracy. And publishing a pro-nukes article on the anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing––without acknowledging the human cost of nuclear weapons, or even the anniversary itself––demonstrates that he is clearly not guided by empathy.

But perhaps most evidently, Stephens’ piece is driven by fear. And understandably so: we’re currently locked into an ever-increasing nuclear arms race with no signs of it slowing down. If you’re not afraid, you’re probably not paying attention. However, crying “more nukes” without articulating any kind of strategic vision isn’t going to get us out of this mess.

In reality, the best way to get out of an arms race is by refusing to play. The United States shouldn’t base the size of its nuclear arsenal in response to how other countries are tweaking theirs––this only makes sense if you believe that nuclear weapons are for fighting wars. But to quote Reagan’s old adage, “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Instead, as explained in Global Zero’s Alternative Nuclear Posture Review, the United States should move towards a “deterrence-only” nuclear posture, which would allow for sizable cuts to the US nuclear arsenal without changing the strategic balance.

Very simply, we need to start enacting ambitious solutions that are equal to the problems that we face. Not just reflexively demanding more nukes.

—

(image: Yosuke Yamahata, one day after the Nagasaki bombing)

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The INF Treaty Officially Died Today

Six months after both the United States and Russia announced suspensions of their respective obligations under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), the treaty officially died today.

The Federation of American Scientists strongly condemns the irresponsible acts by the Russian and US administrations that have resulted in the demise of this historic and important agreement.

In a they-did-it statement on the State Department’s web site, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo repeated the accusation that Russia has violated the treaty by testing and deploying a ground-launched cruise missile with a range prohibited by the treaty. “The United States will not remain party [sic] to a treaty that is deliberately violated by Russia,” he said.

By withdrawing from the INF, the Trump administration has surrendered legal and political pressure on Russia to return to compliance. Instead of diplomacy, the administration appears intent on ramping up military pressure by developing its own INF missiles.

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty dramatically helped reduce nuclear threats and stabilize the arms race for thirty-two years, by banning and eliminating all US and Russian ground-launched missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers––a grand total of 2,692 missiles. And it would have continued to have a moderating effect on US-Russia nuclear tensions indefinitely, if not for the recklessness of both the Putin and Trump administrations.

The United States first publicly accused Russia of violating the treaty in its July 2014 Treaty Compliance Report, stating that Russia had broken its obligation “not to possess, produce, or flight-test a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) with a range capability of 500 km to 5,500 km, or to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.” Russia initially denied the US claims, repeating for years that no such missile existed. However, once the United States publicly named the missile as the 9M729––or SSC-8, as NATO calls it––Russia acknowledged its existence but stated that the missile “fully complies with the treaty’s requirements.” Since then, the United States claimed that Russia had flight-tested the 9M729 from fixed and mobile launchers to deceive, and has deployed nearly a hundred missiles across four battalions.

We assess that involves 16 launchers with 64 missiles (plus spares), likely collocated with Iskander SRBM units at Elanskiy, Kapustin Yar (possibly moved to a permanent base by now), Mozdok, and Shuya. It is possible, but unknown, if more battalions have been deployed.

It is possible that Russia made the decision to violate the INF Treaty as early as 2007, when its UN proposal to multilateralize the treaty failed. Although it’s likely that the groundwork was laid even further back. According to Putin, a new arms race truly began in 2002 when the Bush administration withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty––understood by Putin to be the cornerstone of the US-Russia arms control regime.

For its part, Russia has responded to US accusations with claims that the United States is the true violator of the treaty, stating that US missile defense launchers based in Europe could be repurposed to launch INF-prohibited missiles, among other violations. In a detailed report, the Congressional Research Service has refuted all three accusations.

Regardless of who violated the INF, the Trump administration’s decision to kill the treaty is the wrong move. As we wrote in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists when Trump first announced his intention to quit the treaty, withdrawal establishes a false moral equivalency between the United States, who probably isn’t violating the treaty, and Russia, who probably is. It also puts the United States in conflict with its own key policy documents like the Nuclear Posture Review and public statements made last year, which emphasized bringing Russia back into compliance through diplomatic, economic, and military measures.

The bottom line is this: when someone breaks the law, you shouldn’t throw away the law. By doing so, you remove any chance to hold the violator accountable for their actions. If the ultimate goal is to coax or coerce Russia back into compliance with the treaty, then killing the treaty itself obviously won’t achieve that. Instead, it legally frees Russia to deploy even more INF missiles.

The decision to withdraw wasn’t based on long-term strategic thinking but appears to have been based on ideology. It was apparently the product of National Security Advisor John Bolton––a hawkish “serial arms control killer”––having the President’s ear. Defense hawks chimed in with warnings about Chinese INF-range missiles being outside the treaty (which they have always been) and recommendations about deploying new US INF missiles in the Pacific.

Now, we find ourselves on the brink of an era without nuclear arms control whatsoever. With the demise of the INF, the only remaining treaty – the New START treaty – is in jeopardy, a vital treaty that caps the number of strategic nuclear weapons the United States and Russia can deploy and provides important verification and data exchanges. Although it could easily be extended past its February 2021 expiry date with the stroke of a pen, John Bolton maddeningly says that it’s “unlikely.” And Russian officials too have begun raising issues about the extension. Allowing New START to expire would do away with the last vestiges of US-Russia nuclear restraint, and open the world up to a new open-ended nuclear arms race.

Congress must do whatever it can to convince President Trump to extend the New START treaty.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

New Chinese White Paper Subtly Criticizes Trump’s Approach to Arms Control

On July 22nd, China published its latest Defense White Paper––an infrequent, but significant, military policy document meant for an international audience.

This year’s paper––entitled “China’s National Defense in the New Era”––offers an assessment of the evolving strategic landscape and highlights China’s responses to these new challenges. While the paper takes a more assertive tone than its predecessor (published in 2015), the content isn’t particularly provocative––especially in the sections about nuclear weapons and deterrence, which largely constitute a repetition of the 2015 language.

The white paper states:

China is always committed to a nuclear policy of no first use of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and not using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon free zones unconditionally. China advocates the ultimate complete prohibition and thorough destruction of nuclear weapons. China does not engage in any nuclear arms race with any other country and keeps its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security. China pursues a nuclear strategy of self-defense, the goal of which is to maintain national strategic security by deterring other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against China.

It also states:

Nuclear capability is the strategic cornerstone to safeguarding national sovereignty and security. China’s armed forces strengthen the safety management of nuclear weapons and facilities, maintain the appropriate level of readiness and enhance strategic deterrence capability to protect national strategic security and maintain international strategic stability.

This language is pretty standard for official Chinese statements about its nuclear policy. This makes sense; although China’s nuclear weapons arsenal is slowly growing and diversifying, its nuclear doctrine appears to be relatively consistent.

In reality, the main difference between the 2015 and 2019 language on nuclear weapons and arms control is in China’s assessment of the “international strategic landscape.” The paper notes that the United States has “adopted unilateral policies,” “provoked and intensified competition among major countries, significantly increased its defense expenditure, pushed for additional capacity in nuclear, outer space, cyber and missile defense, and undermined global strategic stability.”

It also specifically calls out NATO enlargement, EU integration and Russian nuclear modernization––criticisms which were all absent in the 2015 white paper.

Interestingly, it notes that “International arms control and disarmament efforts have suffered setbacks, with growing signs of arms races.” The paper additionally subtweets the Trump administration’s role in undermining global arms control, stating that “The Iranian nuclear issue has taken an unexpected turn,” “The international nonproliferation regime is compromised by pragmatism and double standards,” and concludes that “No country can respond alone or stand aloof.”

The white paper doesn’t go into detail about China’s nuclear or missile forces, only noting that the PLA Rocket Force has commissioned the DF-26 “intermediate and long-range ballistic missile.” Despite it being a relatively new missile, we estimate that China has deployed approximately 70 DF-26s––at least two brigades––and it was spotted conducting exercises in Inner Mongolia in January 2019. The 4,000 kilometer range of the DF-26 would allow China to target US bases in Guam, and some Chinese analysts claim that the missile is capable of targeting ships at sea, despite the significant tactical and procedural challenges involved with such an operation.

Read all about China’s nuclear forces in our latest edition of the FAS Nuclear Notebook, freely available at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Russia Upgrades Western Nuclear Weapons Storage Sites

Amidst a deepening rift between the United States and Russia about the role of non-strategic nuclear weapons, Russia has begun to upgrade an Air Force nuclear weapons storage site near Tver, some 90 miles (145 kilometers) northeast of Moscow.

Satellite photos show clearing of trees within the site as well as the construction of a new security fence and guard post. The upgrade, which started late-2017 and was completed late last year, was followed by the arrival of what appears to be weapons transport and service trucks earlier this year (see image below).

The Tver site includes two nuclear weapons bunkers as well as service and security buildings. The new security fence and gate added within the site separates the bunker area from the service area. The site is near the Migalovo Air Base, which is not thought to be housing nuclear strike aircraft but might serve a nuclear weapons transport function. If so, it could potentially be responsible for the distribution of nuclear warheads to tactical air bases in north-western Russia in a crisis.

It is impossible to determine from the satellite images if the Tver site stores nuclear weapons at this time, but it is clearly active with considerable personnel and activities indicating weapons might be present. Alternatively, Tver could serve as an Air Force storage site in a crisis. Tver is one of several dozen nuclear weapons storage sites operated by the Russian ministry of defense and military services (see here and here.

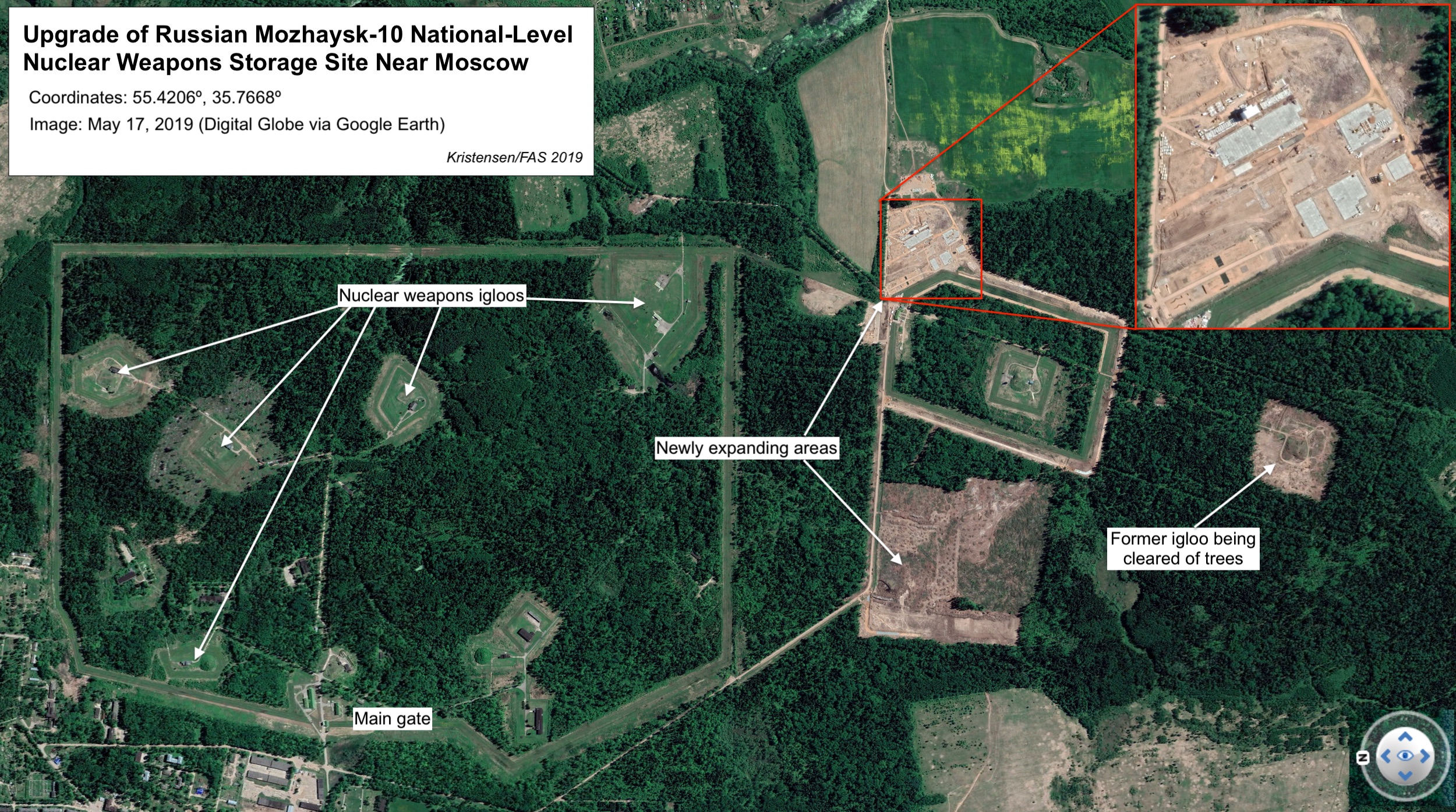

There are also important upgrades underway at the Mozhaysk-10 storage site about 70 miles (114 kilometers) west of Moscow, including addition of new support facilities as well clearing of a previously tree-covered weapons storage igloo. Mozhaysk-10 is one of a dozen national-level nuclear weapons storage site and includes six underground igloos and appears to be expanding (see below). Mozhaysk-10 might be used to store both strategic and tactical nuclear weapons.

The upgrades at the Tver and Mozhaysk-10 sites follow an ongoing upgrade to a nuclear weapons storage site in Kaliningrad that began in 2016 and appears intended to support nuclear-capable forces in the isolated enclave.

Russia is estimated to possess approximately 6,500 nuclear warheads, of which an estimated 4,330 are thought to be available for use by the military. We estimate that Russia has about 1,830 nuclear warheads assigned to non-strategic forces; the Pentagon says the number is “up to 2,000” warheads. The US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently said it expects to see “a significant projected increase in the number of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons” over the next decade, although some past DIA growth projections have turned out to exaggerated.