Nuclear Transparency and the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

I was reading through the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and wondering what I should pick to critique the Obama administration’s nuclear policy.

After all, there are plenty of issues that deserve to be addressed, including:

– Why NNSA continues to overspend and over-commit and create a spending bow wave in 2021-2026 in excess of the President’s budget in exactly the same time period that excessive Air Force and Navy modernization programs are expected to put the greatest pressure on defense spending?

– Why a smaller and smaller nuclear weapons stockpile with fewer warhead types appears to be getting more and more expensive to maintain?

– Why each warhead life-extension program is getting ever more ambitious and expensive with no apparent end in sight?

– And why a policy of reductions, no new nuclear weapons, no pursuit of new military missions or new capabilities for nuclear weapons, restraint, a pledge to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and the goal of disarmament, instead became a blueprint for nuclear overreach with record funding, across-the-board modernizations, unprecedented warhead modifications, increasing weapons accuracy and effectiveness, reaffirmation of a Triad and non-strategic nuclear weapons, continuation of counterforce strategy, reaffirmation of the importance and salience of nuclear weapons, and an open-ended commitment to retain nuclear weapons further into the future than they have existed so far?

What About The Other Nuclear-Armed States?

Despite the contradictions and flaws of the administration’s nuclear policy, however, imagine if the other nuclear-armed states also published summaries of their nuclear weapons plans. Some do disclose a little, but they could do much more. For others, however, the thought of disclosing any information about the size and composition of their nuclear arsenal seems so alien that it is almost inconceivable.

Yet that is actually one of the reasons why it is necessary to continue to work for greater (or sufficient) transparency in nuclear forces. Some nuclear-armed states believe their security depends on complete or near-compete nuclear secrecy. And, of course, some nuclear information must be protected from disclosure. But the problem with excessive secrecy is that it tends to fuel uncertainty, rumors, suspicion, exaggerations, mistrust, and worst-case assumptions in other nuclear-armed states – reactions that cause them to shape their own nuclear forces and strategies in ways that undermine security for all.

Nuclear-armed states must find a balance between legitimate secrecy and transparency. This can take a long time and it may not necessarily be the same from country to country. The United States also used to keep much more nuclear information secret and there are many institutions that will always resist public access. But maximum responsible disclosure, it turns out, is not only necessary for a healthy public debate about nuclear policy, it is also necessary to communicate to allies and adversaries what that policy is about – and, equally important, to dispel rumors and misunderstandings about what the policy is not.

Nuclear transparency is not just about pleasing the arms controllers – it is important for national security.

So here are some thoughts about what other nuclear-armed states should (or could) disclose about their nuclear arsenals – not to disclose everything but to improve communication about the role of nuclear weapons and avoid misunderstandings and counterproductive surprises:

Russia should publish:

Russia should publish:

– Full New START aggregate data numbers (these numbers are already shared with the United States, that publishes its own numbers)

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Number of history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has made statements about percentage reductions since 1991 but not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of which nuclear forces are nuclear-capable (has made some statements about strategic forces but not shorter-range forces)

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces (has made occasional statements about modernizations but no detailed plan)

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

China should publish:

China should publish:

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (stated in 2004 that it possessed the smallest arsenal of the nuclear weapon states but has not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of its nuclear-capable forces

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

France should publish:

France should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile in 2008 and 2015 (300 weapons), but not the history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has declared dismantlement of some types but not history)

(France has disclosed its overall force structure and some nuclear budget information is published each year.)

Britain should publish:

Britain should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has declared some approximate historic numbers, declared the approximate size in 2010 (no more than 225), and has declared plan for mid-2020s (no more than 180), but has not disclosed history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has announced dismantlement of systems but not numbers or history)

(Britain has published information about the size of its nuclear force structure and part of its nuclear budget.)

Pakistan should publish:

Pakistan should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

India should publish:

India should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

Israel should publish:

Israel should publish:

…or should it? Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel has not publicly confirmed it has a nuclear arsenal and has said it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Some argue Israel should not confirm or declare anything because of fear it would trigger nuclear arms programs in other Middle Eastern countries.

On the other hand, the existence of the Israeli nuclear arsenal is well known to other countries as has been documented by declassified government documents in the United States. Official confirmation would be politically sensitive but not in itself change national security in the region. Moreover, the secrecy fuels speculations, exaggerations, accusations, and worst-case planning. And it is hard to see how the future of nuclear weapons in the Middle East can be addressed and resolved without some degree of official disclosure.

North Korea should publish:

North Korea should publish:

Well, obviously this nuclear-armed state is a little different (to put it mildly) because its blustering nuclear threats and statements – and the nature of its leadership itself – make it difficult to trust any official information. Perhaps this is a case where it would be more valuable to hear more about what foreign intelligence agencies know about North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Yet official disclosure could potentially serve an important role as part of a future de-tension agreement with North Korea.

Additional information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces with links to more information about individual nuclear-armed states.

“Nuclear Weapons Base Visits: Accident and Incident Exercises as Confidence-Building Measures,” briefing to Workshop on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Practice, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 27-28 March 2014.

“Nuclear Warhead Stockpiles and Transparency” (with Robert Norris), in Global Fissile Material Report 2013, International Panel on Fissile Materials, October 2013, pp. 50-58.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

An AUMF Against the Islamic State, and More from CRS

Ongoing U.S. military action against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria lacks any specific authorization from Congress. A comparative analysis of various proposals for Congress to enact an Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF) against the Islamic State is provided in an updated report from the Congressional Research Service.

“Although the Obama Administration has claimed 2001 AUMF and 2002 AUMF authority for its recent and future actions against the Islamic State, these claims have been subject to debate,” the report said.

“Some contend that the Administration’s actions against the IS also fall outside the President’s Article II powers. Concerned with Congress’s constitutional role in the exercise of the war power, perceived presidential overreach in that area of constitutional powers, and the President’s expansion of the use of military force in Iraq and Syria, several Members of Congress have expressed the view that continued use of military force against the Islamic State requires congressional authorization. Members have differed on whether such authorization is needed, given existing authorities, or whether such a measure should be enacted.”

“This report focuses on the several proposals for a new AUMF specifically targeting the Islamic State made during the 113th and 114th Congresses. It includes a brief review of existing authorities and AUMFs, as well as a discussion of issues related to various provisions included in existing and proposed AUMFs that both authorize and limit presidential use of military force.” See A New Authorization for Use of Military Force Against the Islamic State: Issues and Current Proposals, January 15, 2016.

Other new and newly updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

North Korea: Legislative Basis for U.S. Economic Sanctions, updated January 14, 2016

North Korea: A Comparison of S. 1747, S. 2144, and H.R. 757, January 15, 2016

North Korea: U.S. Relations, Nuclear Diplomacy, and Internal Situation, updated January 15, 2016

Department of Homeland Security Appropriations: FY2016, updated January 14, 2016

Iran’s Nuclear Program: Tehran’s Compliance with International Obligations, updated January 14, 2016

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons, updated January 14, 2016

North Korea’s Fourth Nuclear Test: What Does it Mean?

By Charles D. Ferguson

North Korea’s boast on January 5 about having detonated a “hydrogen bomb,” the colloquial name for a thermonuclear explosive, seems highly hyperbolic due to the relatively low estimated explosive yield, as inferred from the reported seismic magnitude of about 4.8 (a small- to moderately-sized event). More important, I think the Korean Central News Agency’s rationale for the test deserves attention and makes logical sense from North Korea’s perspective. That statement was: “This test is a measure for self-defense the D.P.R.K. has taken to firmly protect the sovereignty of the country and the vital right of the nation from the ever-growing nuclear threat and blackmail by the U.S.-led hostile forces and to reliably safeguard the peace on the Korean Peninsula and regional security.” (D.P.R.K. stands for the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, the official name for North Korea.)

Having been to North Korea twice (November 2000 and November 2011) and having talked to both political and technical people there, I believe that they are sincere when they say that they believe that the United States has a hostile policy toward their country. After all, the Korean War has yet to be officially ended with a peace treaty. The United States and the Republic of Korea (South Korea) conduct annual war games that have appeared threatening to the North while the United States and the ROK say that they perform these military exercises to be prepared to defend against or deter a potential war with North Korea. Clearly, there is more than enough fear on both sides of the Demilitarized Zone on the Korean Peninsula.

Aside from posturing and signaling to the United States, South Korea, and Japan, a North Korean claim of a genuine hydrogen bomb (even if it is not yet ready for prime time) is cause for concern from a military standpoint because of the higher explosive yields from such weapons. But almost all of the recent news stories, experts’ analyses, and the statements from the White House and South Korea have discounted this claim.

How Does a Boosted Fission Bomb Work?

Instead, at best, the stories and articles suggest that North Korea may have tested a boosted fission device. Such a device would use a fission chain reaction of fissile material, such as plutonium or highly enriched uranium, to then fuse the heavy hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium, which would have been injected just before detonation into the hollow core of the bomb. While the fusion reaction does somewhat increase the explosive yield, the main purpose of this reaction is to release lots of neutrons that would then cause many additional fission reactions.

Does this mean that the explosive yield of the bomb would be dramatically increased due to these additional fission reactions? The answer is yes, if there was a comparable amount of fissile material, as in a non-boosted fission bomb. But the answer is no, if there was much less fissile material than in a non-boosted fission bomb. In both cases, the overall use of fissile material is much more efficient in a boosted device than in a non-boosted device in that a greater portion or percentage of fissile material is fissioned in a boosted device. This increased efficiency is also due to the fact that the additional neutrons are very high energy and will rapidly cause the additional fission reactions before the bomb blows itself apart within microseconds.

In the case where North Korea does not need to produce a much bigger explosive yield per bomb, but is content with low to moderate yields, it can make much more efficient use of its available fissile material (with a stockpile estimated at a dozen to a few dozen bombs’ worth of material) and have much lower weight bombs. This is the key to understanding why a boosted fission bomb is a serious military concern. It is more apt to fit on ballistic missiles. The lighter the payload (warhead), the farther a ballistic missile with a given amount of thrust can carry the bomb to a target.

From a Military Standpoint: Cause for Concern?

So, in my opinion, a boosted fission bomb is even more cause for immediate concern than a thermonuclear bomb. (A thermonuclear “hydrogen” bomb would have the additional technical complication of a fusion fuel stage ignited by a boosted fission bomb. If North Korea eventually develops a true thermonuclear bomb, this type of bomb could, with further development, also likely be made to fit on a ballistic missile.) A boosted fission bomb alone, however, would mean that North Korea is well on its way to making nuclear bombs that are small enough and lightweight enough to fit on ballistic missiles.

If true, North Korea would have nuclear weapons that would provide real military utility. North Korea would not need high yield nuclear explosives to pose a real military nuclear threat because cities such as Seoul and Tokyo cover wide areas and would thus be easy targets even with relatively inaccurate missiles. But the most important point is that the nuclear weapon has to be light enough to be carried by a missile for a long enough distance to reach these and other targets such as the United States by using a long-range missile. In contrast, if North Korea only had large size and heavy weight nuclear bombs, it would have significant difficulty in delivering such weapons to targets, unless it tried to smuggle these unwieldy bombs into South Korea or Japan.

Setting the Record Straight on Recent Reporting

Obviously, the uncertainty about North Korea’s nuclear weapons program is considerable, and we may never fully find out what was really tested a few days ago, despite the planes that the U.S. has been flying near North Korea to detect any leakage of radioactive elements or other physical evidence from the test site.

Nonetheless, I think it is worthwhile to point out that some confusion has been afoot in several news stories. I have read in a number of press reports that there is doubt as to whether North Korea could produce the tritium that would be needed for a boosted fission device. In September of last year, David Albright and Serena Kelleher-Vergantini of the Institute for Science and International Security published a report that the 5 MWe gas-graphite reactor at Yongbyon is “not an ideal producer of isotopes, it can be used in this way.” They noted, “As part of the renovation of the reactor, North Korean technicians reportedly installed (or renovated) irradiation channels in the core. These channels would be used to make various types of isotopes, potentially for civilian or military purposes.”[1] They further observed that tritium could be produced in such irradiation channels, although there is not conclusive evidence of this production.

The New York Times further sowed some confusion by solely mentioning that tritium is used for boosting, but neglected to mention deuterium. The deuterium and tritium fusion reaction is the “easiest” fusion reaction to ignite while still very challenging to do.[2] The Times also gave the impression that boosting was just about increasing the explosive yield but did not discuss the important point about boosting the efficient use of fissile material so as to substantially decrease the overall weight of the bomb.

None other than Dr. Hans Bethe, leader of the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project and a founder of FAS, stated in a May 28, 1952 memorandum that “by the middle of 1948, [Dr. Edward] Teller had invented the booster, in which a fission bomb initiates a thermonuclear reaction in a moderate volume of a mixture of T [tritium] and D [deuterium], … [and a test in Nevada] demonstrated the practical usefulness of the booster for small-diameter implosion weapons.”[3] Note that “small-diameter” in this context implies that this weapon would be suitable for ballistic missiles.

Just a day before the nuclear test, Joseph Bermudez published an essay for the non-governmental website 38 North (affiliated with the US-Korea Institute at the School for Advanced International Studies) about North Korea’s ballistic missile submarine program. He assessed: “Reports of a North Korean ‘ejection’ test of the Bukkeukseong-1 (Polaris-1, KN-11) submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) on December 21, 2015, appear to be supported by new commercial satellite imagery of the Sinpo South Shipyard. This imagery also indicates that despite reports of a failed test in late November 2015 North Korea is continuing to actively pursue its SLBM development program.”[4] A boosted fission device test (if such took place on January 5) would dovetail with the ballistic missile submarine program.

Where Do We Go From Here?

I will conclude by underscoring that the United States will have to work even harder to reassure allies such as Japan and South Korea. Early last year, I wrote a paper that describes how relatively easily South Korea could make nuclear weapons while urging that the United States needs to prevent this from happening. As Prof. Martin Hellman of Stanford University and a member of FAS’s Board of Experts has written in a recent blog: “As distasteful as the Kim Jong-un regime is, we need to learn how to live with it, rather than continue vainly trying to make it collapse. As Dr. [Siegfried] Hecker [former Director of Los Alamos National Laboratory] points out, that latter approach has given us an unstable nation with a nuclear arsenal. Insanity has been defined as repeating the same mistake over and over again, but expecting a different outcome. Isn’t it time we tried a new experiment?”

—

[1] David Albright and Serena Kelleher-Vergantini, “Update on North Korea’s Yongbyon Nuclear Site,” Institute for Science and International Security, Imagery Brief, September 15, 2015, http://www.isis-online.org/uploads/isis-reports/documents/Update_on_North_Koreas_Yongbyon_Nuclear_Site_September15_2015_Final.pdf

[2] “Did North Korea Detonate a Hydrogen Bomb? Here’s What We Know,” New York Times, January 6, 2016.

[3] Hans A. Bethe, “Memorandum on the History of Thermonuclear Program,” May 28. 1952, (Assembled on 5/12/90 from 3 different versions by Chuck Hansen, Editor, Swords of Armageddon), available at http://www.fas.org/nuke/guide/usa/nuclear/bethe-52.htm

[4] Joseph S. Bermudez, Jr., “North Korea’s Ballistic Missile Submarine Program: Full Steam Ahead,” 38 North, January 5, 2016, http://38north.org/2016/01/sinpo010516/

Nuclear Modernization Briefings at the NPT Conference in New York

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week I was in New York to brief two panels at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (phew).

The first panel was on “Current Status of Rebuilding and Modernizing the United States Warheads and Nuclear Weapons Complex,” an NGO side event organized on May 1st by the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). While describing the U.S. programs, I got permission from the organizers to cover the modernization programs of all the nuclear-armed states. Quite a mouthful but it puts the U.S. efforts better in context and shows that nuclear weapon modernization is global challenge for the NPT.

The second panel was on “The Future of the B61: Perspectives From the United States and Europe.” This GNO side event was organized by the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation on May 2nd. In my briefing I focused on providing factual information about the status and details of the B61 life-extension program, which more than a simple life-extension will produce the first guided, standoff nuclear bomb in the U.S. inventory, and significantly enhance NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

The two NGO side events were two of dozens organized by NGOs, in addition to the more official side events organized by governments and international organizations.

The 2014 PREPCOM is also the event where the United States last week disclosed that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has only shrunk by 309 warheads since 2009, far less than what many people had anticipated given Barack Obama’s speeches about “dramatic” and “bold” reductions and promises to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

Yet in disclosing the size and history of its nuclear weapons stockpile and how many nuclear warheads have been dismantled each year, the United States has done something that no other nuclear-armed state has ever done, but all of them should do. Without such transparency, modernizations create mistrust, rumors, exaggerations, and worst-case planning that fuel larger-than-necessary defense spending and undermine everyone’s security.

For the 185 non-nuclear weapon states that have signed on to the NPT and renounced nuclear weapons in return of the promise made by the five nuclear-weapons states party to the treaty (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, and the United States) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to the cessation of the nuclear arms race at early date and to nuclear disarmament,” endless modernization of the nuclear forces by those same five nuclear weapons-states obviously calls into question their intension to fulfill the promise they made 45 years ago. Some of the nuclear modernizations underway are officially described as intended to operate into the 2080s – further into the future than the NPT and the nuclear era have lasted so far.

Download two briefings listed above: briefing 1 | briefing 2

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Air Force Intelligence Report Provides Snapshot of Nuclear Missiles

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published its long-awaited update to the Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report, one of the few remaining public (yet sanitized) U.S. intelligence assessment of the world nuclear (and other) forces.

Previous years’ reports have been reviewed and made available by FAS (here, here, and here), and the new update contains several important developments – and some surprises.

Most important to the immediate debate about further U.S.-Russian reductions of nuclear forces, the new report provides an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

Another new development is a significant number of new conventional short-range ballistic missiles being deployed or developed by China.

Finally, several of the nuclear weapons systems listed in a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing are not included in the NASIC report at all. This casts doubt on the credibility of the AFGSC briefing and creates confusion about what the U.S. Intelligence Community has actually concluded.

Russia

The report estimates that Russia retains about 1,200 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs, slightly higher than our estimate of 1,050. That is probably a little high because it would imply that the SSBN force only carries about 220 warheads instead of the 440, or so, warheads we estimate are on the submarines.

“Most” of the ICBMs “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” the report states. This excessive alert posture is similar to that of the United States, which has essentially all of its ICBMs on alert.

The report also confirms that although Russia is developing and deploying new missiles, “the size of the Russia missile force is shrinking due to arms control limitations and resource constraints.”

Unfortunately, the report does not clear up the mystery of how many warheads the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) missile carries. Initially we estimated thee because the throw-weight is similar to the U.S. Minuteman III ICBM. Then we considered six, but have recently settled on four, as the Strategic Rocket Forces commander has stated.

The report states that “Russia tested a new type of ICBM in 2012,” but it undercuts rumors that it not an ICBM by listing its range as 5,500+ kilometers. Moreover, in an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile, the report concludes: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

The report also describes how Russian designers are working to modify missiles to overcome U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. The SS-27 Mod 1 (Topol-M) deployed in silos at Tatishchevo was designed with countermeasures to ballistic missile systems, and Russian officials claim that a new class of hypersonic vehicle is being developed to overcome ballistic missile defense systems, according to NASIC.

The report also refers to Russian press report that a rail-mobile ICBM is being considered, and that a new “heavy” ICBM is under development.

One of the surprises in the report is that SS-N-32/Bulava-30 missile on the first Borei-class SSBN is not yet considered fully operational – at least not by NASIC. The report lists the missile as in development and “not yet deployed.”

Another interesting status is that while the AS-4 and AS-15 nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missiles are listed as operational, the new Kh-102 nuclear cruise missile that Russian officials have said they’re introducing is not listed at all. The Kh-102 was also listed as already “fielded” by a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing.

Finally, while the report lists the SS-N-21 sea-launched cruise missile as operational, it does not mention the new Kalibr cruise missile for the Yasen-class attack submarine that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed a having been “fielded” within the past five years.

China

The NASIC report states that the Chinese ballistic missile force is expanding both in size and types of missiles.

Deployment of the DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) ICBM continues at a slow pace with “more than 15” launchers deployed six years after the system was first introduced.

Despite many rumors about a new DF-41 ICBM, the NASIC report does not mention this system at all.

Deployment of the shorter-range DF-31 (CSS-10 Mod 1) ICBM, on the contrary, appears to have stalled or paused, with only 5-10 launchers deployed seven years after it was initially introduced (see my recent analysis of this trend here). Moreover, the range of the DF-31 is lowered a bit, from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ in the new version.

Medium-range nuclear missiles include the DF-21 (CSS-5) (in two versions: Mod 1 and Mod 2, but with identical range etc.) and the old DF-3A (CSS-2), which is still listed as deployed. Only 5-10 launchers are left, probably in a single brigade that will probably convert to DF-21 in the near future.

An important new development concerns conventional missiles, where the NASIC report states that several new systems have been introduced or are in development. This includes a “number of new mobile, conventionally armed MRBMs,” apparently in addition to the DF-21C and DF-21D already known. As for the DF-21D anti-ship missile, report states that “China has likely started to deploy” the missile but that it is “unknown” how many are deployed.

More dramatic is the development on five new short-range ballistic missiles, including the CSS-9, CSS-11, CSS-14, CSS-X-15, and CSS-X-16. The CSS-9 and CSS-14 come in different versions with different ranges. The CSS-11 Mod 1 is a modification of the existing DF-11, but with a range of over 800 kilometers (500 miles). None of these systems are listed as nuclear-capable.

Concerning sea-based nuclear forces, the NASIC report echoes the DOD report by saying that the JL-2 SLBM for the new Jin-class SSBN is not yet operational. The JL-2 is designated as CSS-NX-14, which I thought it was a typo in the 2009 report, as opposed to the CSS-NX-3 for the JL-1 (which is also not operational).

NASIC concludes that JL-2 “will, for the first time, allow Chinese SSBNs to target portions of the United States from operating areas located near the Chinese coast.” That is true for Guam and Alaska, but not for Hawaii and the continental United States. Moreover, like the DF-31, the JL-2 range estimate is lowered from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ km in the new version. Earlier intelligence estimates had the range as high as 8,000+ km.

One of the surprises (perhaps) in the new report is that it does not list the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile, which was listed in the U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing as a nuclear cruise missile that had been “fielded” within the past five years.

Concerning the overall size of the Chinese nuclear arsenal, there have been many rumors that it includes hundreds or even thousands of additional warheads more than the 250 we estimate. STRATCOM commander has also rejected these rumors. To that end, the NASIC report lists all Chinese nuclear missiles with one warhead each, despite widespread rumors in the news media and among some analysts that multiple warheads are deployed on some missiles.

Yet the report does echo a projection made by the annual DOD report, that “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM capable of carrying a MIRV payload.” But NASIC does not confirm widespread news media rumors that this system is the DF-41 – in fact, the report doesn’t even mention the DF-41 as in development.

As for the future, the NASIC report repeats the often-heard prediction that “the number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 15 years.” This projection has continued to slip and NASIC slips it a bit further into the future to 2028.

Pakistan

Most of the information about the Pakistani system pretty much fits what we have been reporting. The only real surprise is that the Shaheen-II MRBM does still not appear to be fully deployed, even though the system has been flight tested six times since 2010. The report states that “this missile system probably will soon be deployed.”

India

The information on India also fits pretty well with what we have been reporting. For example, the report refers to the Indian government saying the Agni II IRBM has finally been deployed. But NASIC only lists “fewer than 10” Agni II launchers deployed, the first time I have seen a specific reference to how many of this system are deployed. The Agni III IRBM is said to be ready for deployment, but not yet deployed.

North Korea

The NASIC report lists the Hwasong-13 (KN-08), North Korea’s new mobile ICBM, but confirms that the missile has not yet been flight tested. It also lists an IRBM, but without naming it the Musudan.

The mysterious KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed as a new nuclear system expected within the next five years is not mentioned in the NASIC report.

Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2013

See also previous NASIC reports: 2009 | 2006 | 1998

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

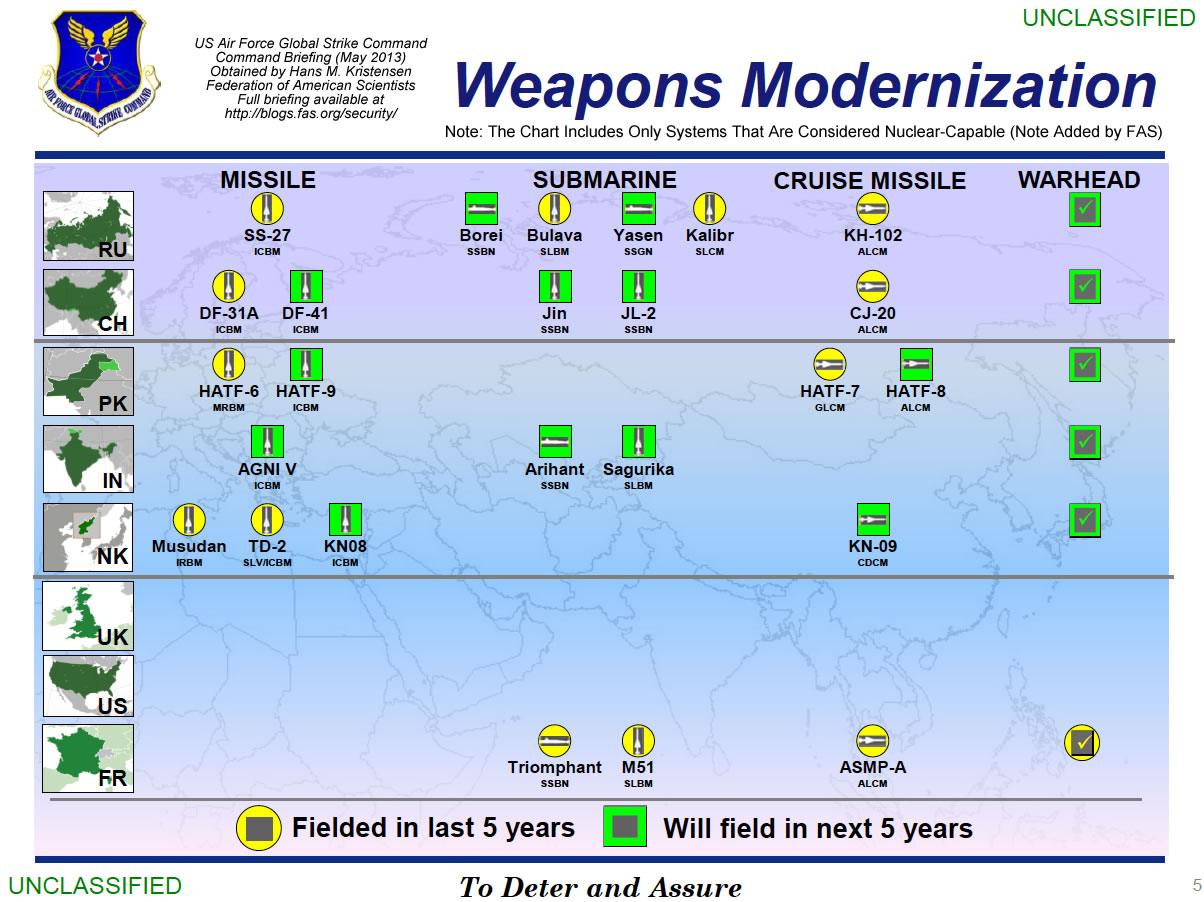

Air Force Briefing Shows Nuclear Modernizations But Ignores US and UK Programs

Click to view large version. Full briefing is here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

China and North Korea are developing nuclear-capable cruise missiles, according to U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC).

The new Chinese and North Korean systems appear on a slide in a Command Briefing that shows nuclear modernizations in eight of the world’s nine nuclear weapons states (Israel is not shown).

The Chinese missile is the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile for delivery by the H-6 bomber. The North Korean missile is the KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile. These weapons would, if for real, be important additions to the nuclear arsenals in Asia.

At the same time, a closer look at the characterization used for nuclear modernizations in the various countries shows generalizations, inconsistencies and mistakes that raise questions about the quality of the intelligence used for the briefing.

Moreover, the omission from the slide of any U.S. and British modernizations is highly misleading and glosses over past, current, and planned modernizations in those countries.

For some, the briefing is a sales pitch to get Congress to fund new U.S. nuclear weapons.

Overall, however, the rampant nuclear modernizations shown on the slide underscore the urgent need for the international community to increase its pressure on the nuclear weapon states to curtail their nuclear programs. And it calls upon the Obama administration to reenergize its efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

Russia

![]()

The briefing lists seven Russian nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known and have been underway for many years. Fielded systems include SS-27 ICBM, Bulava SLBM, Kalibr SLCM, and KH-102 ALCM.

It is puzzling, however, that the briefing lists Bulava SLBM and Kalibr SLCM as fielded when their platforms (Borei SSBN and Yasen SSGN, respectively) are not. The first Borei SSBN officially entered service in January 2013.

Nuclear Cruise Missile For Yasen SSGN

It is the first time I’ve seen a U.S. government publication stating that the non-strategic Kalibr land-attack SLCM is nuclear (in public the Kalibr is sometimes called Caliber). The first Yasen SSGN, the Severodvinsk, test launched the Kalibr in November 2012. The weapon will also be deployed on the Akula-class SSGN. The Kalibr SLCM, which is dual-capable, will probably replace the aging SS-N-21, which is not. There are no other Russian non-strategic nuclear systems listed in the AFGSC briefing.

A new warhead is expected within the next five years, but since no new missile is listed the warhead must be for one of the existing weapons.

China

![]()

The briefing lists six Chinese nuclear modernizations: DF-31A ICBM, DF-41 ICBM, Jin SSBN, JL-2 SLBM, CJ-20 ALCM, and a new warhead.

The biggest surprise is the CJ-20 ALCM, which is the first time I have ever seen an official U.S. publication crediting a Chinese air-launched cruise missile with nuclear capability. The latest annual DOD report on Chinese military modernization does not do so.

H-6 with CJ-20. Credit: Chinese Internet.

The CJ-20 is thought to be an air-launched version of the 1,500+ kilometer ground-launched CJ-10 (DH-10), which the Air Force in 2009 reported as “conventional or nuclear” (the AFGSC briefing does not list the CJ-10). The CJ-20 apparently is being developed for delivery by a modified version of the H-6 medium-range bomber (H-6K and/or H-6M) with increased range. DOD asserts that the H-6 using the CJ-20 ALCM in a land-attack mission would be able to target facilities all over Asia and Russia (east of the Urals) as well as Guam – that is, if it can slip through air defenses.

The elusive DF-41 ICBM is mentioned by name as expected within the next five years. References to a missile known as DF-41 has been seen on and off for the past two decades, but disappeared when the DF-31A appeared instead. The latest DOD report does not mention the DF-41 but states that, “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM, possibly capable of carrying a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV).” (Emphasis added).

AFGSC also predicts that China will field a new nuclear warhead within the next five years. MIRV would probably require a new and smaller warhead but it could potentially also refer to the payload for the JL-2.

Pakistan

![]()

Pakistan is listed with five nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Hatf-8 (Shaheen II) MRBM, Hatf-9 (NASR) SRBM, Hatf-7 (Babur) GLCM, Hatf-8 (Ra’ad) ALCM, and a new warhead. Two of them (Hatf-8 and Hatf-7) are listed as fielded.

The briefing mistakenly identifies the Hatf-9 as an ICBM instead of what it actually is: a short-range (60 km) ballistic missile.

The new warhead might be for the Hatf-9.

India

![]()

India is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Agni V ICBM, Arihant SSBN, “Sagurika” SLBM, and a new warhead. The U.S. Intelligence Community normally refers to “Sagurika” as Sagarika, which is known as K-15 in India.

Neither the Agni III nor Agni IV are listed in the briefing, which might indicate, if correct, that the two systems, both of which were test launched in 2012, are in fact technology development programs intended to develop the technology to field the Agni V.

The U.S. Intelligence Community asserts that the Agni V will be capable of carrying multiple warheads, as recently stated by an India defense industry official – a dangerous development that could well motivate China to deploy multiple warheads on some of its missiles and trigger a new round of nuclear competition between India and China.

The new warhead might be for the SLBM and/or for Agni V.

North Korea

![]()

North Korea is listed with five nuclear modernizations: Musudan IRBM, TD-2 SLV/ICBM, KN-08 ICBM, KN-09 CDCM, and a warhead.

The biggest surprise is that AFGSC asserts that the KN-09 is nuclear-capable. There are few public reports about this weapon, but the South Korean television station MBC reported in April that it has a range of 100-120 km. MBC showed KN-09 as a ballistic missile, but AFGSC lists it as a CDCM (Coastal Defense Cruise Missile).

The Musudan IRBM is listed as “fielded” even though the missile, according to the U.S. Intelligence Community, has never been flight tested. In this case, “fielded” apparently means it has appeared but not that it is operational or necessarily deployed with the armed forces.

The Mushudan is listed as “fielded,” similar to the Russian SS-27, even though the North Korean missile has never been flight tested.

The KN-08 ICBM, which was displayed at the May 2012 parade, was widely seen by non-governmental analysts to be a mockup. But AFGSC obviously believes the weapon is real and expected to be “fielded” within the next five years. There were rumors in January 2013 that North Korea had started moving KN-08 launchers around the country at the beginning of a saber-rattling campaign that lasted through March.

Finally, the AFGSC briefing also predicts that North Korea will field a nuclear warhead within the next five year. Whether this refers to North Korea’s first weaponized warhead or newer types is unclear.

United Kingdom

![]()

The UK section does not include any weapons modernizations, which doesn’t quite capture what’s going on. For example, Britain is deploying the modified W76-1/Mk4A, which British officials have stated will increase the targeting capability of the Trident II D5 SLBM. Accordingly, a warhead icon has been added to the U.K. bar above.

Moreover, although the final approval has not been given yet, Britain is planning construction of a new SSBN to replace the current fleet of four Vanguard-class SSBNs. The missile section is under development in the United States. The new submarine will also receive the life-extended D5 SLBM.

United States

![]()

The U.S. section also does not show any nuclear modernizations, which glosses over important upgrades.

For example, the Minuteman III ICBM is in the final phases of a decade-long multi-billion dollar life-extension program that will extend the weapon to 2030. Privately, Air Force officials are joking that everything except the shell is new. Accordingly, a fielded ICBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Moreover, full-scale production and deployment of the W76-1/Mk4A warhead on the Trident II D5 SLBM is underway. The combination of the new reentry body with the D5 increases the targeting capability of the weapon. Accordingly, a fielded warhead icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

In addition, from 2017 the U.S. Navy will begin deploying a modified life-extended version of the D5 SLBM (D5LE) on Ohio-class SSBNs. Production of the D5LE is currently underway, which will be “more accurate” and “provide flexibility to support new missions,” according to the navy and contractor. Accordingly, a forthcoming SLBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Finally, the United States has begun design of a new SSBN class, a long-range bomber, a long-range cruise missile, a fighter-bomber, a guided standoff gravity bomb, and is studying a replacement-ICBM.

Hardly the dormant nuclear enterprise portrayed in the briefing.

France

![]()

France is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all well known: Triomphant SSBN, M51 SLBM, ASMP-A ALCM, and a new warhead.

The introduction of the ASMP-A is complete but the M51 SLBM is still replacing M45 SLBMs on the SSBN fleet.

The warhead section only appears to include the TNA warhead for the ASMP-A but ignores that France from 2015 will begin replacing the TN75 warhead on the M51 SLBM with the new TNO.

What is Meant by Nuclear and Fielded?

The AFGSC briefing is unclear and somewhat confusing about what constitutes a nuclear-capable weapon system and when it is considered “fielded.”

AFGSC confirmed to me that the slide only lists nuclear-capable weapon systems.

Air Force regulations are pretty specific about what constitutes a nuclear-capable unit. According to Air Force Instruction 13-503 regarding the Nuclear-Capable Unit Certification, Decertification and Restriction Program, a nuclear-capable unit is “a unit or an activity assigned responsibilities for employing, assembling, maintaining, transporting or storing war reserve (WR) nuclear weapons, their associated components and ancillary equipment.”

This is pretty straightforward when it comes to Russian weapons but much more dubious when describing North Korean systems. Russia is known to have developed miniaturized warheads and repeatedly test-flown them on missiles that are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

North Korea is a different matter. It is known to have detonated three nuclear test devices and test-launched some missiles, but that’s pretty much the extent of it. Despite its efforts and some worrisome progress, there is no public evidence that it has yet turned the nuclear devices into miniaturized warheads that are capable of being employed successfully by its ballistic or cruise missiles. Nor is there any public evidence that nuclear-armed missiles are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

Moreover, the U.S. Intelligence Community has recently issued strong statements that cast doubt on whether North Korea has yet mastered the technology to equip missile with nuclear warheads. James Clapper, the director of National Intelligence, testified before the Senate on April 18, 2013, that despite its efforts, “North Korea has not, however, fully developed, tested, or demonstrated the full range of capabilities necessary for a nuclear-armed missile.”

So how can the AFGSC briefing label North Korean ballistic missiles as nuclear-capable – and also conclude that the KN-09 cruise missile is nuclear-capable?

There are similar questions about the determination of when a weapon system is “fielded.” Does it mean it is fielded with the armed forces or simply that it has been seen? For example, how can a North Korean Musudan IRBM be considered fielded similarly to a Russia SS-27 ICBM?

Or how can the Musudan IRBM be identified as already “fielded” when it has not been flight tested and only displayed on parade, when the KN-08 is identified as not “fielded” even though it has also not been flight tested, also been displayed on parade, and even moved around North Korea?

Finally, how can the Russian Bulava SLBM and Kalibr SLCM be listed as “fielded” when their delivery platforms (Borei SSBN and Yasen SSGN, respectively) are listed as not fielded?

These inconsistencies cast doubt on the quality of the AFGSC briefing and whether it represents the conclusion of a coordinated Intelligence Community assessment, or simply is an effort to raise money in Congress for modernizing U.S. bombers and ICBMs.

Implications and Recommendations

There are still more than 17,000 nuclear weapons in the world and all the nuclear weapon states are busy maintaining and modernizing their arsenals. After Russia and the United States have insisted for decades that nuclear cruise missiles are essential for their security, the AFGSC briefing claims that China and North Korea are now trying to follow their lead.

For some, the AFGSC briefing will be (and probably already is) used to argue that nuclear threats against the United States and its allies are increasing and that Congress therefore should oppose further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces and instead approve modernizations of the remaining arsenal.

But Russia is not expanding its nuclear forces, the nuclear arsenals of China and Pakistan are much smaller than U.S. forces, and North Korea is in its infancy as a nuclear weapon state.

Instead, the rampant nuclear modernizations shown in the briefing symbolize struggling arms control and non-proliferation regimes that appear inadequate to turn the tide. They are being undercut by recommitments of a small group of nuclear weapon states to retain and improve nuclear forces for the indefinite future. The modernizations are partially being sustained by non-nuclear weapon states – often the very same who otherwise say they want nuclear disarmament – that insist on being protected by nuclear weapons.

The AFGSC briefing shows that there’s an urgent need for the international community to increase its pressure on the nuclear weapon states to curtail their nuclear programs. Especially limitations on MIRVed missiles are urgently needed. For its part, the Obama administration must reenergize its efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

There have been many nice speeches about reducing nuclear arsenals but too little progress on limiting the endless cycle of modernizations that sustain them.

Document: Air Force Global Strike Command Command Briefing

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 2

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the second of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea’s recent success with its nuclear test and satellite launch evidence that it is maturing? Is there trepidation in Japan over the perceived threat of North Korea attacking Japan with a nuclear weapon? Has North Korea mastered re-entry vehicle (RV) technology? Is there any plausible way to de-nuclearize North Korea?

This is the second part of the Q&A, featuring Dr. Yousaf Butt, Dr. Jacques Hymans and Ms. Masako Toki. Read the first part here. (more…)

Better Understanding North Korea: Q&A with Seven East Asian Experts, Part 1

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Editor’s Note: This is the first of two postings of a Q&A conducted primarily by the Federation of American Scientists regarding the current situation on the Korean Peninsula. Developed and edited by Charles P. Blair, Mark Jansson, and Devin H. Ellis, the authors’ responses have not been edited; all views expressed by these subject-matter experts are their own. Please note that additional terms are used to refer to North Korea and South Korea, i.e., the DPRK and ROK respectively.

Researchers from the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) asked seven individuals who are experts in East Asia about the the recent escalation in tensions on the Korean Peninsula. Is North Korea serious about their threats and are we on the brink of war? What influence does China exert over DPRK, and what influence is China wiling to exert over the DPRK? How does the increase in tension affect South Korean President Park Guen-he’s political agenda?

This is the first part of the Q&A featuring Dr. Ted Galen Carpenter, Dr. Balbina Hwang, Ms. Duyeon Kim and Dr. Leon Sigal. Read part two here.

The Unha-3: Assessing the Successful North Korean Satellite Launch

On December 12, 2012, North Korea finally succeeded in placing an object into low Earth orbit. Recovered debris of the launcher’s first stage verified some previous assumptions about the launch system, but it also included some surprises. Independent from the technical findings and their consequences, the public debate seems to miss some important points.

Fundamental Remarks

Threat is a product of two parameters: intention and capability. If a potential actor has the intention to act, but no capability, there is no threat. If the actor has the capability, but no intention, there is no threat either. Only the combination creates a real threat, but this threat is limited by the magnitude of both factors.

Looking at the public debate about the first successful Unha launch, it is often presupposed that North Korea has an intention to act against the United States (or at least be able to), and so its capabilities are typically interpreted according to that assumed intention: The launch of a large rocket is marked as a camouflaged long range missile test, and the debate now focuses on this missile’s exact throw-weight performance, and on implications of the United States being in reach of a postulated North Korean nuclear missile capability.

A different approach might offer unbiased conclusions, though: first, focus on a capability analysis. After that, figure out what these capabilities might reveal about the intentions. Only then start thinking about the threat and adequate responses. In this case, it means analyzing the Unha-3 on a wide scope, from technical details to the whole program, then considering what the consequences are, and only then re-evaluating the threat situation in a larger context.

Available Data

Reliable data on North Korea’s activities is often in short supply. We have high confidence that the data gathered from the launch footage and the recovered debris is reliable. But it is hard to judge the validity of other available data, especially data that comes from official North Korean sources.

For example, some video footage and photos from the mission control room are also available. There is clear evidence, however, that the video is from a staged presentation. It is therefore unclear how reliable any information extracted from these sources might be.

General Observations

The basic design of the Unha-3 rockets launched in April and December 2012 seems to be widely the same.

The Unha-3 of December 2012 was powered by a cluster of four Nodong-class engines and four small control engines. Available photos of the recovered engines suggest that there might be minor differences between “Nodong/Shahab 3”-engines in Iran and the Unha engine cluster. The control engines show the typical design (corrugated metal sheets) of old Soviet engines, often referred to as “Scud technology.”These small engines are not related to the engines known from the Iranian Safir launcher’s upper stage.

With its Safir satellite launcher, Iran had successfully demonstrated that a two-stage rocket using a Nodong engine in the first stage and a wrung-out upper stage with highly energetic propellants (NTO/UDMH) can carry a small satellite weighing a few dozen kilograms into low Earth orbit (LEO). North Korea had to use a three-stage design for its satellite launch, thus indicating a different approach.

Control Room Video and Photos

An available video implies that the launch was filmed from within the launch control room (Figure 2). However, the various small videos that are displayed on the wall are out of sync, and the clearly visible Media Player interfaces suggest that the whole scene was recorded after the launch, with available launch clips being replayed for the recording. This raises the question of how reliable the displayed data is.

Analysis Results

According to the control room data, the second stage is powered by a Scud-class engine. This is further backed by imagery of the second stage in the assembly building, hinting at a small propulsion unit. The third stage seems to use NTO/UDMH, comparable to the Iranian Safir upper stage. This is further backed by the estimated tank volume ratio. However, some minor differences can be observed between the Safir upper stage and the North Korean Unha third stage.

With the available data, it was possible to reconstruct a model of the Unha rocket that, in simulated launches, could mirror the published trajectory data within a few percent.

The reconstruction is consistent with all the available data. It clearly shows that the Unha-3 is designed as a satellite launcher. The low-thrust engines in the second and third stage prevent the need for free-coast flight phases in the satellite launcher role, but in a ballistic missile role, they lead to significant gravity losses that result in a high performance penalty. A different second stage propulsion unit –a throttled engine, for example, or a simple Nodong engine – would offer range gains in the order of 1,000 km or more.

In a missile role, the three-stage Unha-3 offers around 8,000 km range with a 700 kg payload. With different propulsion units, this could have been extended, perhaps putting the U.S. East Coast into range.

Conclusions

The Unha seems to be designed as a space launch vehicle, with several constraints dictating the observed design (available engines, available technologies, etc.). Being in development for 20 years or more, the program pace is very slow, with only four launches so far. The current success rate of 25 percent is within the expected bandwidth for such a program. It will improve, but only slowly. Different design solutions would have offered more performance in a ballistic missile role.

According to available data, the Unha-3 looks like a typical, slow paced satellite launcher program, producing single prototypes every now and then. A serious missile program would look different. However, close observation is recommended.Table: Reconstructed Unha-3 Data

(approximate figures as of 2013-02-14)Total Length [m]30Total Launch Mass [t]88Payload Mass to LEO [t]~ 0.1+Range [km] (ballistic, 3-stage, 0.7 t)around 8,000First StageAirframealuminumEngine4 x Nodong, 4 x controlThrust (sea level) [t]120Burn Time [s]120FuelkeroseneOxidizerIRFNAUsed Propellant Mass [t]62.6Launch Mass [t]71.3Second StageAirframealuminumEngine1 x Scud-levelThrust (vacuum) [t]14.5Burn Time [s]200FuelkeroseneOxidizerIRFNAUsed Propellant Mass [t]11.6Initial Mass [t]13.1Third StageAirframealuminumEngine?Thrust (vacuum) [t]2.9Burn Time [s]260FuelUDMHOxidizerNTOUsed Propellant Mass [t]2.6Initial Mass [t]3.3

Markus Schiller studied mechanical and aerospace engineering at the TU Munich and received his doctorate degree in Astronautics in 2008. He has been employed at Schmucker Technologie since 2006, except for a one-year Fellowship at the RAND Corporation in Santa Monica, California, in 2011.

Robert Schmucker has five decades of experience researching rocketry, missiles and astronautics. In 1992, he opened his consulting firm, Schmucker Technologie, which provides threat and security analyses for national and international organizations about activities of developing countries and proliferation.

Sanctions and Nonproliferation in North Korea and Iran

The nuclear programs of North Korea and Iran have been, for many years, two of the most pressing and intractable security challenges facing the United States and the international community. While frequently lumped together as “rogue states,” the two countries have vastly different social, economic, and political systems, and the history and status of their nuclear and long-range missile programs differ in several critical aspects.

The international responses to Iranian and North Korean proliferation bear many similarities, particularly in the use of economic sanctions as a central tool of policy. Daniel Wertz, Program Officer at the National Committee on North Korea, and Dr. Ali Vaez, former Director of the Iran Project at the Federation of American Scientists, offer a comparative analysis of U.S. policy toward Iran and North Korea in a FAS issue.

When the Boomers Went to South Korea

There are not many public pictures showing the U.S. ballistic missile submarine visits to South Korea. This one apparently shows the USS John Marshall (SSBN-611) in Chinhae in 1979. The submarine carried 16 Polaris A3 missiles with a total of 48 200-kt warheads.

.

Back in the late-1970s, U.S. nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines suddenly started conducting port visits to South Korea. For a few years the boomers arrived at a steady rate, almost every month, sometimes 2-3 visits per month. Then, in 1981, the visits stopped and the boomers haven’t been back since.

At the time the visits began, the United States also had several hundred nuclear weapons deployed on land in South Korea, but the submarine visits apparently were needed to further demonstrate that the United States was prepared to defend the south against an attack from the north.

After North Korea’s nuclear tests in 2006 and 2009, shelling of South Korean territory and the sinking of one of its warships, there have been reports recently that an increasing number of South Koreans want the United States to deploy nuclear weapons in South Korea again, after the last such weapons were withdrawn in 1991. They think it is necessary to deter North Korea.

Some analysts have even suggested that the United States should develop an improved nuclear earth penetrator to better threaten North Korean deeply buried targets, an idea that was previously proposed the Bush administration but rejected by Congress.

Boomers in Chinhae

The SSBN visits to South Korea are unique; the United States normally does not send SSBNs into foreign ports. But there are exceptions. In 1963, the USS Sam Houston (SSBN-609) sailed into Izmir in Turkey on a mission to assure the Turkish government that the United States still had the nuclear capability to defend Turkey even after Jupiter missiles were withdrawn from bases in Turkey following the Cuban missile crisis. The Izmir visit was a one-time event, however, and no SSBN visited foreign ports for the next 12 years.

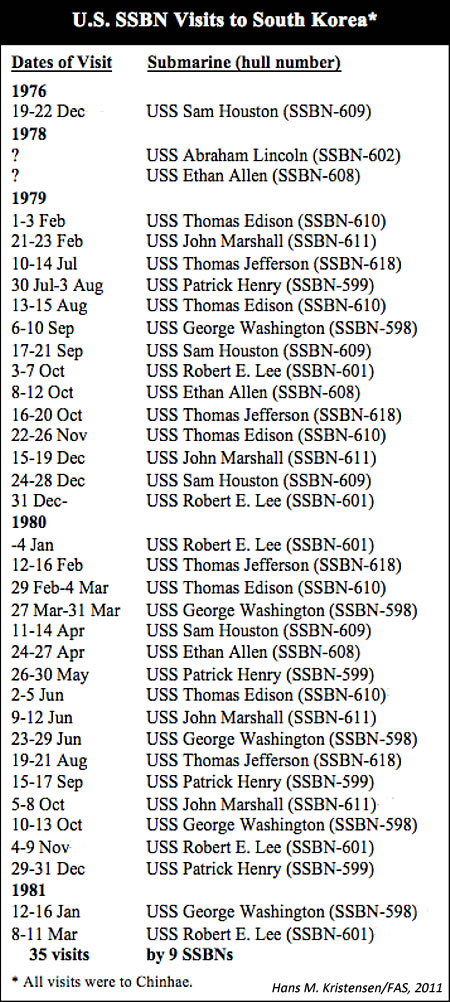

|

| Between December 1976 and March 1981, nine U.S. ballistic missile submarines conducted 35 port visits to South Korea |

Then, on December 19, 1976, the USS Sam Houston suddenly arrived in Chinhae, South Korea. The ship was under order to “surface in Korea for 3 days to ‘rattle the saber,” according to a former crew member. This was the first foreign port visit of a U.S. SSBN in the Pacific.

Two visits followed in 1978 but in 1979 the operations expanded with 14 visits conducted by eight SSBNs. In October that year, three SSBNs made three visits for a combined presence of 15 days.

The following year, in 1980, the number of visits expanded to 15, in June with three visits for a combined 17 days in port. In 1981, coinciding with the phase-out of the Polaris SLBM, the visits dropped to only two.

The Political Context

The 35 port visits conducted by nine SSBNs to Chinhae were a powerful message to South Korea and its potential adversaries about the U.S. nuclear capabilities in the area. But exactly what the reasons for the visits were remain unclear.

The visits took place in a complex political situation. South Korea had started a program to develop nuclear weapons technology, President Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from South Korea, and North Korea was building up its military forces backed by China and the Soviet Union.

Ironically, South Korea had started a nuclear weapons technology program in 1974 not because of doubts about the U.S. nuclear umbrella per ce, but because, according to the CIA, of doubts about the reliability of the overall U.S. security commitment. The program reportedly was terminated in 1976 after U.S. and French pressure. [See here for an insightful analysis]

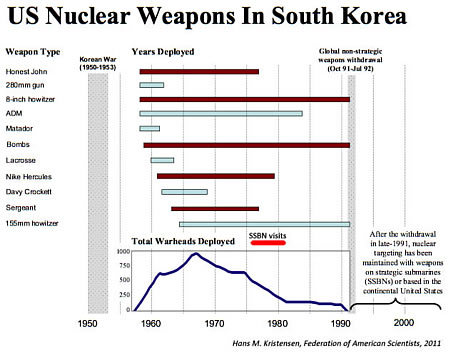

At the same time, newly elected president Jimmy Carter wanted to withdraw U.S. nuclear weapons from bases in South Korea. At the time the SSBN visits began, the U.S. had approximately 500 ground-launched nuclear weapons at bases in South Korea – roughly the same number of warheads as onboard the missiles of the nine visiting SSBNs. [For a brief history of U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in South Korea, go here]. In the end, Carter’s withdrawal didn’t happen but the land-based weapons were significantly reduced (see below).

|

| During the time of the SSBN visits, the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in South Korea was reduced from roughly 500 to 150. The last were withdrawn in 1991. |

.

The SSBN visits might also have been designed to remind China about the U.S. military presence in the region, despite its defeat in Vietnam. The end of the SSBN visits to South Korea in 1981 and the phase-out of the Polaris SSBNs fleet in the Pacific coincided with China’s removal from the U.S. strategic war plan as part of the Reagan administration’s efforts to recruit China as a partner against the Soviet Union. (China was later reinstated in the war plan in 1997 by the Clinton administration.)

In September 1982, the first new Ohio-class SSBN deployed on its first patrol in the Pacific and over the next five years it was followed by seven other boats, each loaded with 24 longer-range and more accurate Trident I C-4 missiles. (All have since been upgraded to the even more capable Trident II D-5 missile). None of the Trident SSBNs have ever visited South Korea, even after the withdrawal of the last land-based nuclear weapons from the country in 1991.

Implications

The SSBN visits to South Korea are a curious but little noticed footnote in the Cold War history. More research is needed to better describe exactly why they happened, but the visits seemed intended to signal assurance to South Korea and deterrence to its adversaries.

As such the visits have potential implications for today. North Korea has since crossed the nuclear threshold, support seems to be growing in South Korea for returning U.S. nuclear weapons to the peninsula, and some argue that better nuclear capabilities are needed to deter Pyongyang.

But the visits are a reminder of the already considerable nuclear capabilities in the region that could be used to signal. Nuclear-capable bombers routinely forward deploy to Guam, and the eight SSBNs patrolling in the Pacific could surface again and visit South Korea if necessary.

|

| Nearly 30,000 U.S. troops in South Korea, large-scale conventional exercises such as the three-carrier battlegroup Valiant Shield (image) and the half-a-million-man Ulchi Freedom Guardian, as well as forward operations of nuclear-capable forces in the region provide a powerful deterrent. |

.

The question is whether it is necessary. The nuclear capabilities the United States operates in the Pacific region today are far more capable than in the 1970s, and the combined conventional forces of South Korea and the United States enjoy a significant advantage over North Korea’s aging conventional forces. To the extent that anything can, these forces should be sufficient to deter large-scale North Korean attacks against the south.

Indeed, Pyongyang’s obsession with the U.S. nuclear capabilities – even its misperception that Washington still deploys nuclear weapons in South Korea – strongly suggests that the current nuclear umbrella has Pyongyang’s full attention and that nuclear redeployment or nuclear bunker busters are not needed. After all, the objective is to move forward toward a denuclearization of the Korean peninsula, not return to the past.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

North Korea: FAS Says We Have Nukes!

|

By Hans M. Kristensen

North Korea’s news agency – Korean Central News Agency – apparently has issued a statement saying that “The Federation of American Scientists of the United States has confirmed (North) Korea as a nuclear weapon state.” According to a report in the Korea Herald, the statement said a FAS publication issued in November listed North Korea as among the nine countries that possess nuclear weapons.

It’s certainly curious that they would need our reaffirmation, but after two nuclear tests we feel it is safe to call North Korea a nuclear weapon state. However, the agency left out that our assessment comes with a huge caveat:

“We are not aware of credible information on how North Korea has weaponized its nuclear weapons capability, much less where those weapons are stored. We also take note that a recent U.S. Air Force intelligence report did not list any of North Korea’s ballistic missiles as nuclear-capable.”

In other words, two experimental nuclear test explosions don’t make a nuclear arsenal. That requires deliverable nuclear weapons, which we haven’t seen any signs of yet. Perhaps the next statement could explain what capability North Korea actually has to deliver nuclear weapons.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.