Federal Climate Policy Is Being Gutted. What Does That Say About How Well It Was Working?

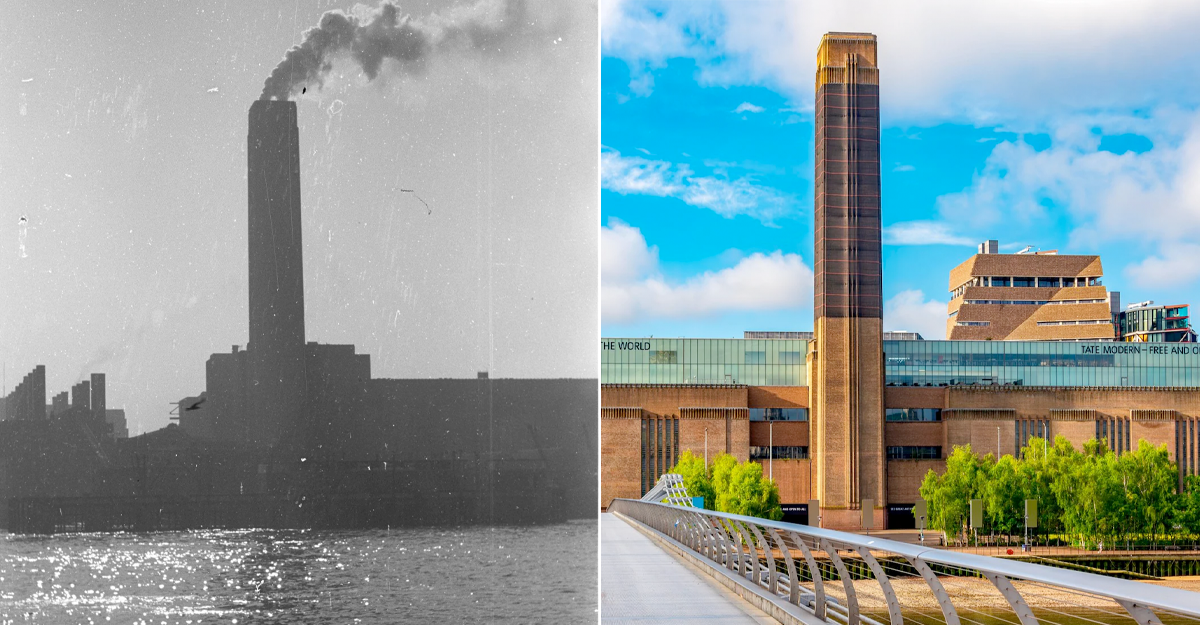

On the left is the Bankside Power Station in 1953. That vast relic of the fossil era once towered over London, oily smoke pouring from its towering chimney. These days, Bankside looks like the right:

The old power plant’s vast turbine hall is now at the heart of the airy Tate Modern Art Museum; sculptures rest where the boilers once churned.

Bankside’s evolution into the Tate illustrates that transformations, both literal and figurative, are possible for our energy and economic systems. Some degree of demolition – if paired with a plan – can open up space for something innovative and durable.

Today, the entire energy sector is undergoing a massive transformation. After years of flat energy demand served by aging fossil power plants, solar energy and battery storage are increasingly dominating energy additions to meet rising load. Global investment in clean energy will be twice as big as investment in fossil fuels this year. But in the United States, the energy sector is also undergoing substantial regulatory demolition, courtesy of a wave of executive and Congressional attacks and sweeping potential cuts to tax credits for clean energy.

What’s missing is a compelling plan for the future. The plan certainly shouldn’t be to cede leadership on modern energy technologies to China, as President Trump seems to be suggesting; that approach is geopolitically unwise and, frankly, economically idiotic. But neither should the plan be to just re-erect the systems that are being torn down. Those systems, in many ways, weren’t working. We need a new plan – a new paradigm – for the next era of climate and clean energy progress in the United States.

Asking Good Questions About Climate Policy Designs

How do we turn demolition into a superior remodel? First, we have to agree on what we’re trying to build. Let’s start with what should be three unobjectionable principles.

Principle 1. Climate change is a problem worth fixing – fast. Climate change is staggeringly expensive. Climate change also wrecks entire cities, takes lives, and generally makes people more miserable. Climate change, in short, is a problem we must fix. Ignoring and defunding climate science is not going to make it go away.

Principle 2. What we do should work. Tackling the climate crisis isn’t just about cleaning up smokestacks or sewer outflows; it’s about shifting a national economic system and physical infrastructure that has been rooted in fossil fuels for more than a century. Our responses must reflect this reality. To the extent possible, we will be much better served by developing fit-for-purpose solutions rather than just press-ganging old institutions, statutes, and technologies into climate service.

Principle 3. What we do should last. The half-life of many climate strategies in the United States has been woefully short. The Clean Power Plan, much touted by President Obama, never went into force. The Trump administration has now turned off California’s clean vehicle programs multiple times. Much of this hyperpolarized back-and-forth is driven by a combination of far-right opposition to regulation as a matter of principle and the fossil fuel industry pushing mass de-regulation for self-enrichment – a frustrating reality, but one that can only be altered by new strategies that are potent enough to displace vocal political constituencies and entrenched legacy corporate interests.

With these principles in mind, the path forward becomes clearer. We can agree that ambitious climate policy is necessary; protecting Americans from climate threats and destabilization (Principle 1) directly aligns with the founding Constitutional objectives of ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, and promoting general welfare. We can also agree that the problem in front of us is figuring out which tools we need, not how to retain the tools we had, regardless of their demonstrated efficacy (Principle 2). And we can recognize that achieving progress in the long run requires solutions that are both politically and economically durable (Principle 3).

Below, we consider how these principles might guide our responses to this summer’s crop of regulatory reversals and proposed shifts in federal investment.

Honing Regulatory Approaches

The Trump Administration recently announced that it plans to dismantle the “endangerment finding” – the legal predicate for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and transportation; meanwhile, the Senate revoked permission for California to enforce key car and truck emission standards. It has also proposed to roll back key power plant toxic and greenhouse gas standards. We agree with those who think that these actions are scientifically baseless and likely illegal, and therefore support efforts to counter them. But we should also reckon honestly with how the regulatory tools we are defending have played out so far.

Federal and state pollution rules have indisputably been a giant public-health victory. EPA standards under the Clean Air Act led directly to dramatic reductions in harmful particulate matter and other air pollutants, saving hundreds of thousands of lives and avoiding millions of cases of asthma and other respiratory diseases. Federal regulations similarly caused mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants to drop by 90% in just over a decade. Pending federal rollbacks of mercury rules thus warrant vocal opposition. In the transportation sector, tailpipe emissions standards for traditional combustion vehicles have been impressively effective. These and other rules have indeed delivered some climate benefits by forcing the fossil fuel industry to face pollution clean-up costs and driving development of clean technologies.

But if our primary goal is motivating a broad energy transition (i.e., what needs to happen per Principle 1), then we should think beyond pollution rules as our only tools – and allocate resources beyond immediate defensive fights. Why? The first reason is that, as we have previously written, these rules are poorly equipped to drive that transition. Federal and state environmental agencies can do many things well, but running national economic strategy and industrial policy primarily through pollution statutes is hardly the obvious choice (Principle 2).

Consider the power sector. The most promising path to decarbonize the grid is actually speeding up replacement of old coal and gas plants with renewables by easing unduly complex interconnection processes that would speed adding clean energy to address rising demand, and allow the old plants to retire and be replaced – not bolting pollution-control devices on ancient smokestacks. That’s an economic and grid policy puzzle, not a pollution regulatory challenge, at heart. Most new power plants are renewable- or battery-powered anyway. Some new gas plants might be built in response to growing demand, but the gas turbine pipeline is backed up, limiting the scope of new fossil power, and cheaper clean power is coming online much more quickly wherever grid regulators have their act together. Certainly regulations could help accelerate this shift, but the evidence suggests that they may be complementary, not primary, tools.

The upshot is that economics and subnational policies, not federal greenhouse gas regulation, have largely driven power plant decarbonization to date and therefore warrant our central focus. Indeed, states that have made adding renewable infrastructure easy, like Texas, have often been ahead of states, like California, where regulatory targets are stronger but infrastructure is harder to build. (It’s also worth noting that these same economics mean that the Trump Administration’s efforts to revert back to a wholly fossil fuel economy by repealing federal pollution standards will largely fail – again, wrong tool to substantially change energy trajectories.)

The second reason is that applying pollution rules to climate challenges has hardly been a lasting strategy (Principle 3). Despite nearly two decades of trying, no regulations for carbon emissions from existing power plants have ever been implemented. It turns out to be very hard, especially with the rise of conservative judiciaries, to write legal regulations for power plants under the Clean Air Act that both stand up in Court and actually yield substantial emissions reductions.

In transportation, pioneering electric vehicle (EV) standards from California – helped along by top-down economic leverage applied by the Obama administration – did indeed begin a significant shift and start winning market share for new electric car and truck companies; under the Biden administration, California doubled down with a new set of standards intended to ultimately phase out all sales of gas-powered cars while the EPA issued tailpipe emissions standards that put the industry on course to achieve at least 50% EV sales by 2030. But California’s EV standards have now been rolled back by the Trump administration and a GOP-controlled Congress multiple times; the same is true for the EPA rules. Lest we think that the Republican party is the sole obstacle to a climate-focused regulatory regime that lasts in the auto sector, it is worth noting that Democratic states led the way on rollbacks. Maryland, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Vermont all paused, delayed, or otherwise fuzzed up their plans to deploy some of their EV rules before Congress acted against California. The upshot is that environmental standards, on their own, cannot politically sustain an economic transition at this scale without significant complementary policies.

Now, we certainly shouldn’t abandon pollution rules – they deliver massive health and environmental benefits, while forcing the market to more accurately account for the costs of polluting technologies, But environmental statutes built primarily to reduce smokestack and tailpipe emissions remain important but are simply not designed to be the primary driver of wholesale economic and industrial change. Unsurprisingly, efforts to make them do that anyway have not gone particularly well – so much so that, today, greenhouse gas pollution standards for most economic sectors either do not exist, or have run into implementation barriers. These observations should guide us to double down on the policies that improve the economics of clean energy and clean technology — from financial incentives to reforms that make it easier to build — while developing new regulatory frameworks that avoid the pitfalls of the existing Clean Air Act playbook. For example, we might learn from state regulations like clean electricity standards that have driven deployment and largely withstood political swings.

To mildly belabor the point – pollution standards form part of the scaffolding needed to make climate progress, but they don’t look like the load-bearing center of it.

Refocusing Industrial Policy

Our plan for the future demands fresh thinking on industrial policy as well as regulatory design. Years ago, Nobel laureate Dr. Elinor Ostrom pointed out that economic systems shift not as a result of centralized fiat, from the White House or elsewhere, but from a “polycentric” set of decisions rippling out from every level of government and firm. That proposition has been amply borne out in the clean energy space by waves of technology innovation, often anchored by state and local procurement, regional technology clusters, and pioneering financial institutions like green banks.

The Biden Administration responded to these emerging understandings with the CHIPS and Science Act, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – a package of legislation intended to shore up U.S. leadership in clean technology through investments that cut across sectors and geographies. These bills included many provisions and programs with top-down designs, but the package as a whole but did engage with, and encourage, polycentric and deep change.

Here again, taking a serious look at how this package played out can help us understand what industrial policies are most likely to work (Principle 2) and to last (Principle 3) moving forward.

We might begin by asking which domestic clean-technology industries need long-term support and which do not in light of (i) the multi-layered and polycentric structure of our economy, and (ii) the state of play in individual economic sectors and firms at the subnational level. IRA revisions that appropriately phase down support for mature technologies in a given sector or region where deployment is sufficient to cut emissions at an adequate pace could be worth exploring in this light – but only if market-distorting supports for fossil-fuel incumbents are also removed. We appreciate thoughtful reform proposals that have been put forward by those on the left and right.

More directly: If the United States wants to phase down, say, clean power tax credits, such changes should properly be phased with removals of support for fossil power plants and interconnection barriers, shifting the entire energy market towards a fair competition to meet increasing load, as well as new durable regulatory structures that ensure a transition to a low-carbon economy at a sufficient pace. Subsidies and other incentives could appropriately be retained for technologies (e.g., advanced battery storage and nuclear) that are still in relatively early stages and/or for which there is a particularly compelling argument for strengthening U.S. leadership. One could similarly imagine a gradual shift away from EV tax credits – if other transportation system spending was also reallocated to properly balance support among highways, EV charging stations, transit, and other types of transportation infrastructure. In short, economic tools have tremendous power to drive climate progress, but must be paired with the systemic reforms needed to ensure that clean energy technologies have a fair pathway to achieving long-term economic durability.

Our analysis can also touch on geopolitical strategy. It is true that U.S. competitors are ahead in many clean technology fields; it is simultaneously true that the United States has a massive industrial and research base that can pivot ably with support. A pure on-shoring approach is likely to be unwise – and we have just seen courts enjoin the administration’s fiat tariff policy that sought that result. That’s a good opportunity to have a more thoughtful conversation (in which many are already engaging) on areas where tariffs, public subsidies, and other on-shoring planning can actually position our nation for long-term economic competition on clean technology. Opportunities that rise to the top include advanced manufacturing, such as for batteries, and critical industries, like the auto sector. There is also a surprising but potent national security imperative to center clean energy infrastructure in U.S. industrial policy, given the growing threat of foreign cyberattacks that are exploiting “seams” in fragile legacy energy systems.

Finally, our analysis suggests that states, which are primarily responsible for economic policy in their jurisdictions, have a role to play in this polycentric strategy that extends beyond simply replicating repealed federal regulations. States have a real opportunity in this moment to wed regulatory initiatives with creative whole-of-the-economy approaches that can actually deliver change and clean economic diversification, positioning them well to outlast this period of churn and prosper in a global clean energy transition.

A successful and “sticky” modern industrial policy must weave together all of the above considerations – it must be intentionally engineered to achieve economic and political durability through polycentric change, rather than relying solely or predominantly on large public subsidies.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration has moved with alarming speed to demolish programs, regulations, and institutions that were intended to make our communities and planet more liveable. Such wholesale demolition is unwarranted, unwise, and should not proceed unchecked. At the same time, it is, as ever, crucial to plan for the future. There is broad agreement that achieving an effective, equitable, and ethical energy transition requires us to do something different. Yet there are few transpartisan efforts to boldly reimagine regulatory and economic paradigms. Of course, we are not naive: political gridlock, entrenched special interests, and institutional inertia are formidable obstacles to overcome. But there is still room, and need, to try – and effort bears better fruit when aimed at the right problems. We can begin by seriously debating which past approaches work, which need to be improved, which ultimately need imaginative recasting to succeed in our ever-more complex world. Answers may be unexpected. After all, who would have thought that the ultimate best future of the vast oil-fired power station south of the Thames with which we began this essay would, a few decades later, be a serene and silent hall full of light and reflection?

Building an Environmental Regulatory System that Delivers for America

The Clean Air Act. The Clean Water Act. The National Environmental Policy Act. These and most of our nation’s other foundational environmental laws were passed decades ago – and they have started to show their age. The Clean Air Act, for instance, was written to cut air pollution, not to drive the whole-of-economy response that the climate crisis now warrants. The Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 was designed to make cars more efficient in a pre-electric vehicle era, and now puts the Department of Transportation in the awkward position of setting fuel economy standards in an era when more and more cars don’t burn gas.

Trying to manage today’s problems with yesterday’s laws results in government by kludge. Legacy regulatory architecture has foundered under a patchwork of legislative amendments and administrative procedures designed to bridge the gap between past needs and present realities. Meanwhile, Congressional dysfunction has made purpose-built updates exceptionally difficult to land. The Inflation Reduction Act, for example, was mostly designed to move money rather than rethink foundational statutes or regulatory processes – because those rethinks couldn’t make it past the filibuster.

As the efficacy of environmental laws has waned, so has their durability. What was once a broadly shared goal – protecting Americans from environmental harm – is now a political football, with rules that whipsaw back and forth depending on who’s in charge.

The second Trump Administration launched the biggest environmental deregulatory campaign in history against this backdrop. But that campaign, coupled with massive reductions in the federal civil service and a suite of landmark court decisions (including Loper Bright) about how federal agencies regulate, risks pushing U.S. regulatory architecture past the point of sensible and much-needed reform and into a state of complete disrepair.

Dismantling old systems has proven surprisingly easy. Building what comes next will be harder. And the work must begin now.

It is time to articulate a long-term vision for a government that can actually deliver in an ever-more complex society. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is meeting this moment by launching an ambitious new project to reimagine the U.S. environmental regulatory state, drawing ideas from across ideological lines.

The Beginning of a New Era

Fear of the risks of systemic change often prevent people from entertaining change in earnest. Think of the years of U.S. squabbles over how or whether to reform permitting and environmental review, while other countries simply raced ahead to build clean energy projects and establish dominance in the new world economy. Systemic stagnation, however, comes with its own consequences.

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) are a case in point when it comes to climate and the environment. Together, these two pieces of legislation represented the largest global investment in the promise of a healthier, more sustainable, and, yes, cheaper future. Unfortunately, as proponents of the “abundance” paradigm and others have observed, rollout was hampered by inefficient processes and outdated laws. Implementing the IRA and the IIJA via old systems, in short, was like trying to funnel an ocean through a garden hose – and as a result, most Americans experienced only a trickle of real-world impact.

Similar barriers are constraining state progress. For example, the way we govern and pay for electricity has not kept pace with a rapidly changing energy landscape – meaning that the United States risks ceding leadership on energy technologies critical to national security, economic competitiveness, and combating climate change.

But we are perhaps now entering a new era. The United States appears to be on the edge of real political realignments, with transpartisan stakes around the core role of government in economic development that do not match up neatly to current coalitions. This realignment presents a crucial opportunity to catalyze a new era of climate, environmental, and democratic progress.

FAS will leverage this opportunity by providing a forum for debate and engagement on different facets of climate and environmental governance, a platform to amplify insights, and the capacity to drive forward solutions. Examples of topics ripe for exploration include:

- Balancing agility and accountability. As observed, regulatory approaches of the past have struggled to address the interconnected, quickly evolving nature of climate and environmental challenges. At the same time, mechanisms for ensuring accountability have been disrupted by an evolving legal landscape and increasingly muscular executive. There is a need to imagine and test new systems designed to move quickly but responsibly on climate and environmental issues.

- Complementing traditional regulation through novel strategies. There is growing interest in using novel financial, contractual, and other strategies as a complement to regulation for driving climate and environmental progress. There is considerable room to go deeper in this space, identifying both the power of these strategies and their limits.

- Rethinking stakeholder engagement. The effectiveness of regulation depends on its ability to serve diverse stakeholder needs while advancing environmental goals. Public comment and other pipelines for engaging stakeholders and integrating external perspectives and expertise into regulations have been disrupted by technologies such as AI, while the relationship between regulated entities and their regulators has become increasingly adversarial. There is a need to examine synergies and tradeoffs between centering stakeholders and centering outcomes in regulatory processes, as well as examine how stakeholder engagement could be improved to better ensure regulations that are informed, feasible, durable, and distributively fair.

In working through topics like these, FAS seeks to lay out a positive vision of regulatory reconstruction that is substantively superior to either haphazard destruction or incremental change. Our vision is nothing less than to usher in a new paradigm of climate and environmental governance: one that secures a livable world while reinforcing democratic stability, through systems that truly deliver for America.

We will center our focus on the federal government given its important role in climate and environmental issues. However, states and localities do a lot of the work of a federated government day-to-day. We recognize that federal cures are unlikely to fully alleviate the symptoms that Americans are experiencing every day, from decaying infrastructure to housing shortages. We are committed to ensuring that solutions are appropriately matched to the root cause of state capacity problems and that federal climate and environmental regulatory regimes are designed to support successful cooperation with local governments and implementation partners.

FAS is no stranger to ambitious endeavors like these. Since our founding in 1945, we have been committed to tackling the major science policy issues that reverberate through American life. This new FAS workstream will be embedded across our Climate and Environment, Clean Energy, and Government Capacity portfolios. We have already begun engaging and activating the diverse community of scholars, experts, and leaders laying the intellectual groundwork to develop compelling answers to urgent questions surrounding the climate regulatory state, against the backdrop of a broader state capacity movement. True to our nonpartisan commitment, we will build this work on a foundation of cross-ideological curiosity and play on the tension points in existing coalitions that strike us all as most productive.

We invite you to join us in conversation and collaboration. If you want to get involved, contact Zoë Brouns (zbrouns@fas.org).

Technology and NEPA: A Roadmap for Innovation

Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy proposed critical energy, infrastructure, and environmental restoration projects. Some of these projects must undergo some level of National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review, a process that requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impacts of their decisions.

Technology and data play an important role in and ultimately dictate how agencies, project developers, practitioners and the public engage with NEPA processes. Unfortunately, the status quo of permitting technology falls far short of what is possible in light of existing technology. Through a workstream focused on technology and NEPA, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) have described how technology is currently used in permitting processes, highlighted pockets of innovation, and made recommendations for improvement.

Key findings, described in more detail below, include:

- Systems and digital tools play an important role at every stage of the permitting process and ultimately dictate how federal employees, permit applicants, and constituents engage with NEPA processes and related requirements.

- Developing data standards and a data fabric should be a high priority to support agency innovation and collaboration.

- Case management systems and a cohesive NEPA database are essential for supporting policy decisions and ensuring that data generated through NEPA is reusable.

- Product management practices can and should be applied broadly across the permitting ecosystem to identify where technology investments can yield the highest gains in productivity.

- User research methods and investments can ensure that NEPA technology are easier for agencies, applicants, and constituents to use.

Introduction

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that works to embed science, technology, innovation, and experience into government and public discourse. The Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization focused on building policies that deliver spectacular improvement in the speed of environmental progress.

FAS and EPIC have partnered to evaluate how agencies use technology in permitting processes required by NEPA. We’ve highlighted pockets of innovation, talked to stakeholders working to streamline NEPA processes, and made evidence-based recommendations for improved technology practices in government. This work has substantiated our hypothesis that technology has untapped potential to improve the efficiency and utility of NEPA processes and data.

Here, we share challenges that surfaced through our work and actionable solutions that stakeholders can take to achieve a more effective permitting process.

Background

NEPA was designed in the 1970s to address widespread industrial contamination and habitat loss. Today, it often creates obstacles to achieving the very problems it was designed to address. This is in part because of an emphasis on adhering to an expanding list of requirements that adds to administrative burdens and encourages risk aversion.

Digital systems and tools play an important role at every stage of the permitting process and ultimately dictate how federal employees, permit applicants, and constituents engage with NEPA processes and related requirements. From project siting and design to permit application steps and post-permit activities, agencies use digital tools for an array of tasks throughout the permitting “life-cycle”—including for things like permit data collection and application development; analysis, surveys, and impact assessments; and public comment processes and post-permit monitoring.

Unfortunately, the current technology landscape of NEPA comprises fragmented and outdated data, sub-par tools, and insufficient accessibility. Agencies, project developers, practitioners and the public alike should have easy access to information about proposed projects, similar previous projects, public input, and up-to-date environmental and programmatic data to design better projects.

Our work has largely been focused on center-of-government agencies and actions agencies can take that have benefits across government.

Key actors include:

- The Permitting Council. Established in 2015 through the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (known as FAST-41), the Permitting Council is charged with facilitating coordination of qualified infrastructure projects subject to NEPA as well as serving as a center of excellence for permitting across the federal government. Administrative functions and salaries are supported primarily by annual appropriations. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) funding enables “ongoing operation of, maintenance of, and improvements to the Federal permitting dashboard” while Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding supports the center of excellence and coordination functions.

- The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). CEQ is an office within the Executive Office of the President established in 1969 through the National Environmental Policy Act. Executive Order 11991, issued in 1977, gave CEQ the authority to issue regulations under NEPA. However, President Trump rescinded that EO in January 2025 and issued a new Executive Order on Unleashing American Energy. This new Executive Order directs the Chair of CEQ to provide “guidance on implementing the National Environmental Policy Act…and propose rescinding CEQ’s NEPA regulations found at 40 CFR 1500 et seq.” CEQ has received annual appropriations to support staff as well as supplemental funding. The IRA provided CEQ with $32.5 million to “support environmental and climate data collection efforts and $30 million more to “support efficient and effective environmental reviews.“

Below, we outline key challenges identified through our work and propose actionable solutions to achieve a more efficient, effective, and transparent NEPA process.

Challenges and Solutions

Product management practices are not being applied broadly to the development of technology tools used in NEPA processes.

Applying product management practices and frameworks has potential to drastically improve the return on investment in permitting technology and process reform. Product managers help shepherd the concept for what a project is trying to achieve and get it to the finish line, while project managers ensure that activities are completed on time and on budget. In a recent blog post, Jennifer Pahlka (Senior Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists and the Niskanen Center) contrasts the project and product funding models in government. Product models, executed by a team with product management skills, facilitate iterative development of software and other tools that are responsive to the needs of users.

Throughout our work, the importance of product management as a tool for improving permitting technology has become abundantly clear; however there is substantial work to be done to institutionalize product management practices in policy, technology, procurement, and programmatic settings.

Solutions:

- Create process maps for the permitting process – in detail – within and across agencies. Once processes are mapped, agencies can develop tailored technology solutions to alleviate identified administrative burdens by either removing, streamlining, or automating steps where possible and appropriate. As part of this process, agencies should evaluate existing software assets, use these insights to streamline approval processes, and expand access to the most critical applications. Agencies can work independently or in collaboration to inventory their software assets. Mapping should be a collaborative, iterative effort between project leads and practitioners. Mapping leads should consider whether the co-development of user journeys with practitioners who play different roles in the permitting process, such as applicants, environmental specialists (federal employees), and public commenters, would be a useful first step to help scope the effort.

- Hire product management and customer experience specialists in strategic roles. Agencies and center of government leaders should carefully consider where product management and customer experience expertise could support innovation. For example, the Permitting Council could hire a product management specialist or customer experience expert to consult with agencies on their technology development projects. Fellowship programs like the Presidential Innovation Fellows (PIF) or U.S. Digital Corps can be leveraged to provide agencies with expertise for specific projects.

- Strategically leverage existing product management guidance and resources. Agencies should use existing resources to support product management in government. The 18F unit, part of the General Services Administration (GSA)’s Technology Transformation Services (TTS), helps federal agencies build, share, and buy technology products. 18F offers a number of tools to support agencies with product management. GSA’s IT Modernization Centers of Excellence can support agency staff in using a product-focused approach. The Centers focused on Contact Center, Customer Experience, and Data and Analytics may be most relevant for agencies building permitting technology. In addition, the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) “collaborates with public servants throughout the government”; their staff can assist with product, strategy, and operations as well as procurement and user experience. 18F and USDS could work together to provide product management training for relevant staff at agencies with a NEPA focus. 18F or USDS could create product management guidance specifically for agencies working on permitting, expanding on the 18F Product Guide. These resources could also explore how agencies can make decisions about building or buying when developing permitting technology. Agencies can also look to the private sector and NGOs for compelling examples of product development.

- Learn from successes at other agencies. We have written about how agencies have successfully applied product management approaches inside and outside of the NEPA space.

Siloed, fragmented data and systems cost money and time for governments and industry

As one partner said, “NEPA is where environmental data goes to die.” Data is needed to inform both risk analysis and decisions; data can and should be reused for these purposes. However, data used and generated through the NEPA process is often siloed and can’t be meaningfully used across agencies or across similar projects. Consequently, applicants and federal employees spend time and money collecting environmental data that is not meaningfully reused in subsequent decisions.

Solutions:

- Develop a data fabric and taxonomy for NEPA-related data. CEQ’s Report to Congress on the Potential for Online and Digital Technologies to Address Delays in Reviews and Improve Public Accessibility and Transparency, delivered in July 2024, recommends standards that would give agencies and the public the ability to track a project from start to finish, know specifically what type of project is being proposed, and understand the complexity of that project. The federal government should pilot interagency programs to coordinate permitting data for existing and future needs. Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) should invest in this process and engage their staff where applicable and appropriate.

- Establish a Digital Service for the Planet to work with agencies specifically on how environmental data is collected and shared across agencies. The Administration should create a Digital Service for the Planet (DSP) that is staffed with specialists who have prior experience working on environmental projects. The DSP should support cross-agency technology development and improve digital infrastructure to better foster collaboration and reduce duplication of federal environmental efforts to achieve a more integrated approach to technology—one that makes it easier for all stakeholders to meet environmental, health, justice, and other goals for the American people.

- Centralize access to NEPA documents and ensure that a user-friendly platform is available to facilitate public engagement. The federal government should ensure public access to a centralized repository of NEPA documents, and a searchable, user-friendly platform to explore and analyze those documents. Efforts to develop a user friendly platform should include dedicated digital infrastructure to continually update centralized datasets and an associated dashboard. Centralizing searchable historical NEPA documents and related agency actions would make it easier for interested parties to understand the environmental assessments, analyses, and decisions that shape projects. Congress can require and provide resources to support this, agencies can invest staff time in participation, and agency leaders can set an expectation for participation in the effort.

Technology tools used in NEPA processes fall far short of their potential

The status quo of permitting technology falls far short of what is possible in light of existing technology. Permitting tools we identified in our inventory range widely in intended use cases and maturity levels. Opportunities exist to reduce feature fragmentation across these tools and improve the reliability of their content. Additionally, many software tools are built and used by a single agency, instead of being efficiently shared across agencies. Consequently, technology is not realizing its potential to improve environmental decision-making and mitigation through the NEPA process.

Solutions:

- Set more ambitious modernization goals. We have the technological capabilities to go above and beyond data fabric and taxonomy. CEQ and the Permitting Council can focus on helping agencies scale successful permitting technology projects and develop decision support tools. This could include supporting agency tools to bring e-permitting into the modern era, which speeds processing time and saves staff time. Agency tools to enhance could include USACE’s Regulatory Request System and tool for tracking wetland mitigation credits (RIBITS), USFWS’s tool for Endangered Species Act consultation (IPaC), the Permitting Council’s FAST-41 dashboard, and CEQ’s eNEPA tool. Policymakers and staff working to improve permitting technology should consider replicating the functionality of successful existing tools, and automating the determination of “application completeness”, which has frequently been cited as a source of delays.

- Institutionalize human centered design (HCD) principles and processes. Agencies should encourage and incentivize deployment of HCD processes. The Permitting Council, GSA, and agency leadership can play a key role in institutionalizing these principles through agency guidance and staff training. Applying human-centered design can ensure thoughtful, well-designed automation of tasks that free up staff members to focus their limited time and attention on matters that need their focus and, crucially, increase the number of NEPA decisions the federal government is able to reach in a designated period of time.

- Prioritize development of digital applications with easy-to-use forms. Application systems may look different from agency to agency depending on their specific needs, but all should prioritize easy-to-use forms, working collaboratively where applicable. Relevant HCD principles include entering data once, user-friendly templates or visual aids, and auto-populating information. Eventually, more advanced features could be incorporated into such forms—including features like AI-generated suggestions for application improvements, fast-tracking reviews for submissions that use templates, and highlighting deviations from templates for review by counsel.

- Create better pre-design tools to give applicants more information about where they can site projects. Improved pre-design tools can help applicants anticipate components of a site that may come up in environmental reviews, such as endangered species. Examples include Vibrant Planet’s landscape resilience tool and the USFWS iPAC platform. These platforms can be developed by agencies or by private-sector and nonprofit organizations. Agencies should seek opportunities to invest in tools that meet multiple needs or provide shared services. The Permitting Council and/or CEQ could lead an interagency task force on modernizing permitting and establish a cross-agency workflow to prevent the siloing of these tools and support agencies in pursuing shared services approaches where applicable.

- Invest in decision-support tools to better equip federal employees. Many regulators lack either the technical skillset to review projects and/or lack the confidence to efficiently and effectively review permit applications to the extent needed. Decision-support tools are needed to lay out all options that the reviewer needs to be aware of to make an informed and timely decision that isn’t based on institutional knowledge (e.g., existing categorical exclusions or nationwide permits that fit the project). These types of decision-support tools can also help create more consistency across reviews. CEQ and/or the Permitting Council could establish a cross-agency workflow to prevent siloing of these tools and support agencies in pursuing shared services approaches where applicable.

Existing NEPA technology tools are difficult for agencies, applicants, and constituents to use

Agencies generally do not conduct sufficient user research in the development of permitting technology. This can be because agencies do not have the resources to hire product management expertise or train staff in product management approaches. Consequently, agencies may only engage users at the very end (if at all), or not think expansively about the range of users in the development of technology for NEPA applications. Advocacy groups and permit applicants aren’t well considered as tools are being developed. As a consequence, permitting forms and other tools are insufficiently customized for their sectors and audiences.

Solutions:

- Incorporate user research into existing projects. Agencies can build user experience activities and funding into project plans and staffing for bespoke permitting tool development. There are resources available to agencies to incorporate user research if they don’t have the talent in-house (as many don’t). These include the 18F unit, GSA’s IT Modernization Centers of Excellence, USDS, and the Presidential Innovation Fellows program.

- Elevate case studies of agencies using user research to improve product delivery. As a center of excellence, the Permitting Council can support elevating agencies using user research. CEQ can also support sharing both challenges and opportunities across agencies. CERPOs can exchange ideas and elevate case studies to explore what is working.

- Launch a regulatory sandbox for permitting. A sandbox would allow testing of different forms and other small interventions. The sandbox would provide an environment for intentional AB testing (e.g., test a new permitting form with ten applicants). The sandbox could be managed by the Permitting Council or another agency, but responsibility to oversee the sandbox should be contained within one single agency. This office should be empowered to offer waivers or exemptions. Ideally, a customer experience specialist would lead the activities of the sandbox. Improving forms that project proponents or public commenters might encounter during the NEPA process is low-hanging fruit that could be a first focus area for the sandbox. Better forms would make processes simpler for applicants, but would also make it possible for agencies to receive and manage associated geospatial and environmental data with applications.

Poor understanding of the costs and benefits of NEPA processes

Costs and benefits of the federal permitting sector have to date been poorly quantified, which makes it difficult to decide where to invest in technology, process reform, talent, or a combination. Applying technology solutions in the wrong place or at the wrong time could make processes more complicated and expensive, not less. For instance, automating a process that simply should not exist would be a waste of resources. At the same time, eliminating processes that provide critical certainty and consistency for developers while delivering substantial environmental benefits would work against goals of achieving greater efficiency and effectiveness.

A more reliable, comprehensive accounting of NEPA costs and benefits will help us design solutions that cost less for taxpayers, better account for public input, and enable rapid yet responsible deployment of energy infrastructure and other critical projects.

Solutions:

- Equip agencies with case management systems that automatically collect data needed for process evaluation. Case management software systems support coordination across multiple stakeholders working on a shared task (e.g., an Environmental Impact Statement). Equipping agencies with these systems would enable automatic capture of data needed to conduct rigorous cost-benefit assessments, providing researchers with rich data to study the impacts of policy interventions on staff time and document quality. Automatic data collection would also drastically reduce the need for expensive and time-consuming retrospective data gathering and analysis efforts. and

- Rapidly execute on a permitting research agenda to support innovation. Establishing a robust case management system may take time. In the interim, agencies, philanthropy, nonprofits, and others can undertake research projects that inform nearer-term decisions about NEPA. Collaborations with user researchers, designers, and product managers will make this research agenda successful. Key gaps a research agenda could address include:

- Money and Time Federal Agencies Spend on NEPA Tasks

- How many staff whose primary job is spent on permitting-related tasks does each agency employ at the national, region, and field levels? The study scope could start with the agencies on the Permitting Council, as they are agencies with relatively large roles in the permitting process.

- How do staffing levels correspond with the number and kind of permitting actions by region and field office? Sources for agency staffing data could include General Services Administration employment classifications and agency NEPA offices.

- What is each agency’s total budget allocated for NEPA review? Do budget codes accurately reflect permitting work?

- Research Gap 2: Private Sector Cost and Scale. The NEPA sector is larger than just the federal government. For example, private-sector consulting firms sometimes help project sponsors prepare their applications and navigate federal processes. A number of private sector entities support the permitting process through government contracts. Questions include:

- What is the total market size of the permitting private sector (dollar amount and employees)?

- What percent is spent on federally mandated permits? How does this break down by task? What are the most expensive labor components and why?

- Research Gap 3: Technology-related Costs

- Building on FAS and EPIC’s permitting inventory, what is the annual technology budget for each agency’s major permit tracking system? Answers to this question should include both internal and external staff costs.

- How many years has each system been in operation? How did the application receive initial funding (e.g., appropriation, general fund, permitting-specific budget)? This helps us know 1) which systems are likely in the most need of an upgrade and 2) how likely it is that funding will be available in the future to modernize.

- Money and Time Federal Agencies Spend on NEPA Tasks

Conclusion

Policymakers, agencies, and permitting stakeholders should recognize the important role that systems and digital tools play in every stage of the permitting process and take steps to ensure that these technologies meet user needs. Developing data standards and a data fabric should be a high priority to support agency innovation and collaboration, while case management systems and a cohesive NEPA database are essential for supporting policy decisions and ensuring that data generated through NEPA is reusable. Leveraging technology in the right place at the right time can support permitting innovation that improves American competitiveness, security, and prosperity.

Building a Comprehensive NEPA Database to Facilitate Innovation

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Innovation and Jobs Act are set to drive $300 billion in energy infrastructure investment by 2030. Without permitting reform, lengthy review processes threaten to make these federal investments one-third less effective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions. That’s why Congress has been grappling with reforming the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) for almost two years. Yet, despite the urgency to reform the law, there is a striking lack of available data on how NEPA actually works. Under these conditions, evidence-based policy making is simply impossible. With access to the right data and with thoughtful teaming, the next administration has a golden opportunity to create a roadmap for permitting software that maximizes the impact of federal investments.

Challenge and Opportunity

NEPA is a cornerstone of U.S. environmental law, requiring nearly all federally funded projects—like bridges, wildfire risk-reduction treatments, and wind farms—to undergo an environmental review. Despite its widespread impact, NEPA’s costs and benefits remain poorly understood. Although academics and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) have conducted piecemeal studies using limited data, even the most basic data points, like the average duration of a NEPA analysis, remain elusive. Even the Government Accountability Office (GAO), when tasked with evaluating NEPA’s effectiveness in 2014, was unable to determine how many NEPA reviews are conducted annually, resulting in a report aptly titled “National Environmental Policy Act: Little Information Exists on NEPA Analyses.”

The lack of comprehensive data is not due to a lack of effort or awareness. In 2021, researchers at the University of Arizona launched NEPAccess, an AI-driven program aimed at aggregating publicly available NEPA data. While successful at scraping what data was accessible, the program could not create a comprehensive database because many NEPA documents are either not publicly available or too hard to access, namely Environmental Assessments (EAs) and Categorical Exclusions (CEs). The Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) also built a language model to analyze NEPA documents but contained their analysis to the least common but most complex category of environmental reviews, Environmental Impact Statements (EISs).

Fortunately, much of the data needed to populate a more comprehensive NEPA database does exist. Unfortunately, it’s stored in a complex network of incompatible software systems, limiting both public access and interagency collaboration. Each agency responsible for conducting NEPA reviews operates its own unique NEPA software. Even the most advanced NEPA software, SOPA used by the Forest Service and ePlanning used by the Bureau of Land Management, do not automatically publish performance data.

Analyzing NEPA outcomes isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s an essential foundation for reform. Efforts to improve NEPA software have garnered bipartisan support from Congress. CEQ recently published a roadmap outlining important next steps to this end. In the report, CEQ explains that organized data would not only help guide development of better software but also foster broad efficiency in the NEPA process. In fact, CEQ even outlines the project components that would be most helpful to track (including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type).

Put simply, meshing this complex web of existing softwares into a tracking database would be nearly impossible (not to mention expensive). Luckily, advances in large language models, like the ones used by NEPAccess and PNNL, offer a simpler and more effective solution. With properly formatted files of all NEPA documents in one place, a small team of software engineers could harness PolicyAI’s existing program to build a comprehensive analysis dashboard.

Plan of Action

The greatest obstacles to building an AI-powered tracking dashboard are accessing the NEPA documents themselves and organizing their contents to enable meaningful analysis. Although the administration could address the availability of these documents by compelling agencies to release them, inconsistencies in how they’re written and stored would still pose a challenge. That means building a tracking board will require open, ongoing collaboration between technologists and agencies.

- Assemble a strike team: The administration should form a cross-disciplinary team to facilitate collaboration. This team should include CEQ; the Permitting Council; the agencies responsible for conducting the greatest number of NEPA reviews, including the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers; technologists from 18F; and those behind the PolicyAI tool developed by PNNL. It should also decide where the software development team will be housed, likely either at CEQ or the Permitting Council.

- Establish submission guidelines: When handling exorbitant amounts of data, uniform formatting ensures quick analysis. The strike team should assess how each agency receives and processes NEPA documents and create standardized submission guidelines, including file format and where they should be sent.

- Mandate data submission: The administration should require all agencies to submit relevant NEPA data annually, adhering to the submission guidelines set by the strike team. This process should be streamlined to minimize the burden on agencies while maximizing the quality and completeness of the data; if possible, the software development team should pull data directly from the agency. Future modernization efforts should include building APIs to automate this process.

- Build the system: Using PolicyAI’s existing framework, the development team should create a language model to feed a publicly available, searchable database and dashboard that tracks vital metadata, including:

- The project components suggested in CEQ’s E-NEPA report, including unique ID numbers, level of review, document type, and project type

- Days spent producing an environmental review (if available; this information may need to be pulled from agency case management materials instead)

- Page count of each environmental review

- Lead and supporting agencies

- Project location (latitude/longitude and acres impacted, or GIS information if possible)

- Other laws enmeshed in the review, including the Endangered Species Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the National Forest Management Act

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, cost of producing the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, staff hours used to produce the review

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, jobs and revenue created by the project

- When clearly stated in a NEPA document, carbon emissions mitigated by the project

Conclusion

The stakes are high. With billions of dollars in federal climate and infrastructure investments on the line, a sluggish and opaque permitting process threatens to undermine national efforts to cut emissions. By embracing cutting-edge technology and prioritizing transparency, the next administration can not only reshape our understanding of the NEPA process but bolster its efficiency too.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

It’s estimated that only 1% of NEPA analyses are Environmental Impact Statements (EISs), 5% are Environmental Assessments (EAs), and 94% are Categorical Exclusions (CEs). While EISs cover the most complex and contentious projects, using only analysis of EISs to understand the NEPA process paints an extremely narrow picture of the current system. In fact, focusing solely on EISs provides an incomplete and potentially misleading understanding of the true scope and effectiveness of NEPA reviews.

The vast majority of projects undergo either an EA or are afforded a CE, making these categories far more representative of the typical environmental review process under NEPA. EAs and CEs often address smaller projects, like routine infrastructure improvements, which are critical to the nation’s broader environmental and economic goals. Ignoring these reviews means disregarding a significant portion of federal environmental decision-making; as a result, policymakers, agency staff, and the public are left with an incomplete view of NEPA’s efficiency and impact.