Iran: Interim Nuclear Agreement, and More from CRS

New products from the Congressional Research Service that Congress has withheld from online public distribution include the following.

Iran: Interim Nuclear Agreement and Talks on a Comprehensive Accord, November 26, 2014

U.S. International Corporate Taxation: Basic Concepts and Policy Issues, December 2, 2014

Taxation of Internet Sales and Access: Legal Issues, December 1, 2014

The Corporate Income Tax System: Overview and Options for Reform, December 1, 2014

How OFAC Calculates Penalties for Violations of Economic Sanctions, CRS Legal Sidebar, December 1, 2014

What Is the Current State of the Economic Recovery?, CRS Insights, December 1, 2014

Employment Growth and Progress Toward Full Employment, CRS Insights, November 28, 2014

Major Disaster Declarations for Snow Assistance and Severe Winter Storms: An Overview, December 1, 2014

Jordan: Background and U.S. Relations, December 2, 2014

Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy, December 2, 2014

Verification Requirements for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran

Negotiations are currently underway with Iran regarding their nuclear program; as a result, one of the main questions for U.S. government policymakers is what monitoring and verification measures and tools will be required by the United States, its allies, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to ensure Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful.

To answer this question, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) convened a non-partisan, independent task force to examine the technical and policy requirements to adequately verify a comprehensive or other sustained nuclear agreement with Iran. Through various methods, the task force interviewed or met with over 70 experts from various technical and policy disciplines and compiled the results in the new report, “Verification Requirements for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran.” Authored by task force leaders Christopher Bidwell, Orde Kittrie, John Lauder and Harvey Rishikof, the report outlines nine recommendations for U.S. policymakers relating to a successful monitoring and verification agreement with Iran. They are as follows:

Six Elements of an Effective Agreement

1. The agreement should require Iran to provide, prior to the next phase of sanctions relief, a comprehensive declaration that is correct and complete concerning all aspects of its nuclear program both current and past.

2. The agreement should provide the IAEA, for the duration of the agreement, access without delay to all sites, equipment, persons and documents requested by the IAEA, as currently required by UN Security Council Resolution 1929.

3. The agreement should provide that any material acts of non-cooperation with inspectors are a violation of the agreement.

4. The agreement should provide for the establishment of a consultative commission, which should be designed and operate in ways to maximize its effectiveness in addressing disputes and, if possible, building a culture of compliance within Iran.

5. The agreement should provide that all Iranian acquisition of sensitive items for its post-agreement licit nuclear program, and all acquisition of sensitive items that could be used in a post-agreement illicit nuclear program, must take place through a designated transparent channel.

6. The agreement should include provisions designed to preclude Iran from outsourcing key parts of its nuclear weapons program to a foreign country such as North Korea.

Three Proposed U.S. Government Actions to Facilitate Effective Implementation of an Agreement

1. The U.S. Government should enhance its relevant monitoring capabilities, invest resources in monitoring the Iran agreement, and structure its assessment and reporting of any Iranian noncompliance so as to maximize the chances that significant anomalies will come to the fore and not be overlooked or considered de minimis.

2. The U.S. Government and its allies should maintain the current sanctions regime architecture so that it can be ratcheted up incrementally in order to deter and respond commensurately to any Iranian non-compliance with the agreement.

3. The U.S. Government should establish a joint congressional/executive branch commission to monitor compliance with the agreement, similar to Congress having created the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe to monitor the implementation of the 1975 Helsinki Accords.

President’s Message: Legitimizing Iran’s Nuclear Program

Be careful of self-fulfilling prophecies about the intentions for Iran’s nuclear program. Often, Western analysts view this program through the lens of realist political science theory such that Iranian leaders seek nuclear weapons to counteract threats made to overthrow their regime or to exert dominance in the Middle East. To lend support to the former argument, Iranian leaders can point to certain political leaders in the United States, Israel, Saudi Arabia, or other governments that desire, if not actively pursue, the downfall of the Islamic Republic of Iran. To back up the latter rationale for nuclear weapons, Iran has a strong case to make to become the dominant regional political power: it has the largest population of any of its neighbors, has a well-educated and relatively technically advanced country, and can shut off the vital flow of oil and gas from the Strait of Hormuz. If Iran did block the Strait, its leaders could view nuclear weapons as a means to protect Iran against attack from powers seeking to reopen the Strait. (Probably the best deterrent from shutting the Strait is that Iran would harm itself economically as well as others. But if Iran was subject to crippling sanctions on its oil and gas exports, it might feel compelled to shut down the Strait knowing that it is already suffering economically.) These counteracting external threats and exerting political power arguments provide support for the realist model of Iran’s desire for nuclear bombs.

But viewed through another lens, one can forecast continual hedging by Iran to have a latent nuclear weapons capability, but still keeping barriers to proliferation in place such as inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In particular, Iranian leaders have arguably gained considerable political leverage over neighbors by just having a latent capability and have maintained some legitimacy for their nuclear program by remaining part of the IAEA’s safeguards system.

If Iran crosses the threshold to make its own nuclear weapons, it could stimulate neighbors to build or acquire their own nuclear weapons. For example, Saudi leaders have dropped several hints recently that they will not stand idly by as Iran develops nuclear weapons. The speculation is that Saudi Arabia could call on Pakistan to transfer some nuclear weapons or even help Saudi Arabia develop the infrastructure to eventually make its own fissile material for such weapons. Pakistan is the alleged potential supplier state because of stories that Saudi Arabia had helped finance Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program and thus, Islamabad owes Riyadh for this assistance. Moreover, Pakistan remains outside the Non-Proliferation Treaty and therefore would not have the treaty constraint as a brake on nuclear weapons transfer. Furthermore, one could imagine a possible nuclear cascade involving the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Egypt, all states that are developing or considering developing nuclear power programs. This proliferation chain reaction would likely then undermine Iran’s security and make the Middle East further prone to potential nuclear weapons use.

I would propose for the West to act optimistically and trust but verify Iran’s claim that its nuclear program is purely for peaceful purposes. The interim deal that was recently reached between Iran and the P5+1 (the United States, Russia, France, China, United Kingdom, and the European Union) is encouraging in that it places a temporary halt on some Iranian activities such as construction of the 40 MW reactor at Arak, the further enrichment of uranium to 20 percent uranium-235 (which is about 70 percent of the work needed to reach the weapons-grade level of 90 percent uranium-235), and continued expansion of the enrichment facilities. Iran also has become more open to the IAEA’s inspections. But these are measures that can be readily reversed if the next deal cannot be negotiated within the next several months. Iran is taking these actions in order to get relief from some economic sanctions.

Without getting into the complexities of the U.S. and Iranian domestic politics as well as international political considerations, I want to outline in the remaining part of this president’s message a research agenda for engineers and scientists. I offer FAS as a platform for these technical experts to publish their analyses and communicate their findings. Specifically, FAS will create a network of experts to assess the Iranian nuclear issues, publish their work on FAS.org, and convene roundtables and briefings for executive and legislative branch officials.

Let’s look at the rich research agenda, which is intended to provide Iran with access to a suite of peaceful nuclear activities while still putting limits on the latent weapons capacity of the peaceful program. By doing so, we can engender trust with Iranians, but this will hinge on adequate means to detect breakout into a nuclear weapons program.

First, consider the scale of Iran’s uranium enrichment program. It is still relatively small, only about a tenth of the capacity needed to make enough low enriched uranium for even the one commercial nuclear plant at Bushehr. Russia has a contract with Iran for ten years of fuel supply to Bushehr. If both sides can extend that agreement over the 40 or more years of the life of the plant, then Iran would not have the rationale for a large enrichment capacity based on that one nuclear plant. However, Iran has plans for a major expansion of nuclear power. Would it be cost effective for Iran to enrich its own uranium for these power plants? The short answer is no, but because of Iranian concerns about being shut out of the international enrichment market and because of Iranian pride in having achieved even a modestly sized enrichment capacity, Iranian leaders will not give up enrichment. I would suggest that a research task for technical experts is to work with Iran to develop effective multi-layer assurances for nuclear fuel. Another task is to assess what capacity of enrichment is appropriate for the existing and under construction research and isotope production reactors or for smaller power reactors. These reactors require far less enrichment capacity than a large nuclear power plant. A first order estimate is that Iran already has the right amount of enrichment capacity to fuel the current and planned for research reactors. But nuclear engineers and physicists can and should perform more detailed calculations.

One reactor under construction has posed a vexing challenge; this is the 40 MW reactor being built at Arak. The concern is that Iran has planned to use heavy water as the moderator and natural uranium as the fuel for this reactor. (Heavy water is composed of deuterium, a heavy form of hydrogen with a proton and neutron in its nucleus, rather than the more abundant “normal” hydrogen, with a proton in its nucleus, which composes the hydrogen atoms in “light” or ordinary water.) A heavy water reactor can produce more plutonium per unit of power than a light water reactor because there are more neutrons available during reactor operations to be absorbed by uranium-238 to produce plutonium-239, a fissile material. The research task is to develop reactor core designs that either use light water or use heavy water with enriched uranium. The light water reactor would have to use enriched uranium in order to operate. A heavy water reactor could also make use of enriched uranium in order to reduce the available neutrons. Another consideration for nuclear engineers who are researching how to reduce the proliferation potential of this reactor is to determine how to lower the power rating, while still providing enough power for Iran to carry out necessary isotope production services and scientific research with the reactor. The 40 MW thermal power rating implies that if operated at near full power for a year, this reactor can make one to two bombs’ worth of plutonium annually. Another research problem is to design the reactor so that it is very difficult to use in an operational mode to produce weapons-grade plutonium. Safeguards and monitoring are essential mechanisms to forestall such production but might not be adequate. Here again, research into proliferation-resistant reactor designs would shed light on this problem.

Regarding isotope production, further research and development would be useful to figure out if non-reactor alternative technologies such as particle accelerators can produce the needed isotopes at a reasonable cost. Derek Updegraff and Pierce Corden of the American Association of the Advanced of Science have been investigating alternative production methods. Science progresses faster when additional researchers investigate similar issues. Thus, this research task could bear considerable fruit if teams can develop cost effective non-reactor means to produce medical and other industrial isotopes in bulk (or whatever quantity is required). If such development is successful, Iran and other countries could retire isotope production reactors that could pose latent proliferation concerns.

Finally, I will underscore perhaps the biggest research challenge: how to ensure that the Iranian nuclear program is adequately safeguarded and monitored. One of the next important steps for Iran is to apply a more rigorous safeguards system called the Additional Protocol and for a period of time, perhaps from five to ten years, apply inspection measures that go beyond the requirements of the Additional Protocol in order to instill confidence in the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear program. Dozens of states have ratified the Additional Protocol, which requires the IAEA to assess whether there are any undeclared nuclear material and facilities in the country being inspected. The Additional Protocol was formed in response to the finding in 1991 in Iraq that Saddam Hussein’s nuclear technicians were getting close to producing fissile material for nuclear weapons, despite the fact that Iraq was subject to regular IAEA inspections of its declared nuclear material and facilities. The undeclared facilities were often physically near declared facilities. There are concerns that given the large land area of Iran, clandestine nuclear facilities might go unnoticed by the IAEA or other means of detection and thus pose a significant risk for proliferation. The research task is to find out if there are effective means to find such clandestine facilities and to provide enough warning before Iran would be able to make enough fissile material and form it into bombs.

A key consideration of any part of this research agenda is how to cooperate with Iranian counterparts. For this plan to be acceptable and achievable, Iranian engineers, scientists, and leaders must own these concepts and believe that the plan supports their objectives to have a legitimate nuclear program that can generate electricity, produce isotopes for medical and industrial purposes, and provide other peaceful benefits including scientific research. Thus, we will need to leverage earlier and ongoing outreach to Iran by organizations such as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advance of Science, and the Richard M. Lounsbery Foundation. Future workshops with Iranian counterparts are essential and companion studies by these counterparts would further advance the cause of legitimizing the Iranian nuclear program.

Several scientists and other technically trained experts in the United States have already been assessing aspects of this agenda as I indicated above with the mention of Updegraff and Corden’s research. Also, without meaning to slight anyone I may not know of or forget to mention, I would call out David Albright and his team at the Institute for Science and International Security, Richard Garwin of IBM, Frank von Hippel and colleagues at Princeton University, and Scott Kemp of MIT. This group is doing insightful work, but I believe that getting more engineers and scientists involved would bring more diverse ideas and more technical expertise to bear on this challenge to international security.

Engineers and scientists have a fundamental role to play in explaining the technical options to policy makers. For FAS, in particular, such work will help revitalize the organization as a true federation of scientists and engineers dedicated to devoting their talents to a more secure and safer world. FAS invites you to contact us if you have skills and knowledge you want to contribute to this proposal to help ensure Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists

One Step at a Time With Iran

As hoped, the P5+1 and Iran settled on a “first step” agreement to resolve concerns about Iran’s potential to develop nuclear weapons and its interest in doing so. We cannot predict how far this process will go or what the next step to establish a comprehensive, enduring agreement that puts the nuclear issue squarely in the past will include. But we can predict that we will never know how good a final agreement can be unless all sides work in good faith to support the process and abstain from taking actions that could potentially undermine it.

The agreement covers the next six months in order to de-escalate a standoff that has been growing in intensity for over a decade. As reported unofficially, some of the most significant provisions include Iran agreeing downblend half of its 20% enriched uranium gas to <5% and convert the remainder to a solid form for fuel*and to not advance further its work on the IR-40 heavy water reactor at Arak, among other things. Most importantly, Iran agreed to enhanced monitoring of its nuclear facilities by the IAEA and to provide the IAEA with an updated design inventory questionnaire for the IR-40 reactor at Arak in order to work out a long-term safeguarding plan for that facility.

In exchange, Iran will receive a pause on future sanctions to further reduce revenue from oil exports and sanctions relief on precious metals and petrochemical exports. The P5+1 also agreed to several other measures that can best be described as humanitarian. These include the licensing the supply of parts that will help improve aviation safety in Iran and establishing financial channels to open up trade in food, agricultural products, and medicine. In total, the package is estimated to be worth about $7 billion to Iran. Far from a windfall, that represents about a 1.3% boost to an Iranian economy that has an annual GDP of $548.9 billion, according to the CIA.

In a historical perspective, the opportunity is indeed a golden one. Although the great attention paid to the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation may make it seem otherwise, occurrences of it are rare. Since the conclusion of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), only three countries have developed and tested nuclear bombs. Promising opportunities to address acute proliferation risks diplomatically are even rarer. Make no mistake: the P5+1 and Iran are making a history right now that will be studied by social scientists for years to come.

The question is now this: What story will they tell? Will they tell the story of an agreement that set the stage for a groundbreaking, precedent-setting arrangement for nuclear transparency and nonproliferation? Or will they tell the of the United States and Iran acting in bad faith, and blowing yet another opportunity to settle and move beyond the questions surrounding Iran’s interest in nuclear weapons?

The United States Congress has a big role to play in answering that question. That is because, as Chris Bidwell at FAS explains, lifting the sanctions that are hurting Iran the most will require the consent of the legislative branch. Moving forward, Congress needs to get beyond the talking point of demanding that Iran mothball its nuclear program entirely and think more deeply, and more specifically, about how much is enough to warrant relief from all sanctions attached to concerns about Iran’s nuclear program.

That means getting clear about what is required (and not required) to resolve this issue. Instead of having a more focused national discourse on the matter, it has become common to conflate civilian with military uses of nuclear technology by framing the matter at-hand as one of stopping “expansion of Iran’s nuclear program toward a nuclear weapon.” The imagery almost makes it seem as if Iran’s nuclear facilities are cocooned by a magical shell that, once breached, will somehow produce a nuclear weapon. But it doesn’t work that way. Iran could install a google of centrifuges and have heavy water reactors all over the place and never make one nuclear bomb. And there is more good news in that, currently, Iran has a relatively modest civilian nuclear power infrastructure.

Still, the key to addressing concerns about its use and Iran’s nuclear destiny over the long term is a matter of addressing political issues, not technical ones. For now, the step one agreement makes clear that the imposition of new “nuclear related” sanctions will constitute a breach of trust and thus a violation. One could debate whether or not the passage of legislation that would impose new sanctions (or the restoration of sanctions relieved) after a provisional period would constitute a violation, but there is no point in risking it.

In fact, those who argue against the agreement on the grounds that the regime is deceptive, gaming the P5+1, and looking for an excuse to continue its so-called nuclear “march” should be the most wary about providing Iran with that excuse by imposing new sanctions now. Rather, those who truly believe that Iran intends to fool the world about its nuclear ambitions should be the staunchest advocates of strict adherence to the first step deal now in order to prove right their suspicions about the other side.

Carrying out that experiment requires, among other things, putting on the back burner Senator Bob Corker’s ill-advised “Iran Nuclear Compliance Act,” which would impose sanctions on Iran for failing to make good on its commitments made in Geneva. Not only is this bill – like all Iran sanctions bills at the moment – ill-timed, its title perpetuates the myth that U.S. objectives are limited to merely ensuring compliance with legal obligations. To the contrary, many of the things that Congress apparently wants Iran to do – mothballing facilities either already built or 90% complete, shipping out uranium, and disavowing any right to enrich again in the future – go far beyond anything for which there is legal basis or precedent.

Of course, one could only imagine the reaction if Iran passed similar legislation predetermining the outcome of future negotiations and demanding the installation of more centrifuges and hastening work on the IR-40 should the P5+1 fail to comply with their ends of the bargain just reached in Geneva. As far as the U.S. Congress is concerned, if it wants to deflect criticisms of sanctions by implying that its demands are limited to matters of “compliance,” then it should make sure that it limits its demands to those for which there is actually a pre-existing legal requirement that Iran comply. Iran would likely agree to such an approach. Moreover, those who remain concerned about Iranian intentions should do their part to address the Iranian motivations underneath them by supporting the Obama Administration’s efforts to repair the broken U.S.-Iran relationship instead of accusing it of appeasement whenever it tries.

We don’t need to re-litigate the entirety of Iran’s nuclear history or all the reasons it may have had (or still has) to pursue nuclear weapons. But we do need some clarity of thought on what we are trying to do about it and how. Skepticism about the process put in place is warranted, but the Obama Administration is undoubtedly on a track worth pursuing. Dressing up an overzealous sanctions drive that could derail that process in language about “compliance” may be good marketing, but it is terrible policy.

Mark Jansson is an Adjunct Fellow for Special Projects with the Federation of American Scientists. The views expressed above are his own.

*This post originally stated Iran, per the agreement, would cut in half its 20% enriched stockpile. In fact, by downblending half and also converting the remainder to a solid oxide form, this agreement effectively eliminates the 20% enriched uranium available for further enrichment. While Iran always claimed that its 20% enriched uranium would be used for fuel, the agreement hastens that conversion process to help ensure that it makes good in that claim.

President’s Message: Rights and Responsibilities

The election of Hassan Rouhani as the president of Iran has breathed new life into the negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. In recent months, a flurry of meetings has raised hopes that this program can remain peaceful and that war with Iran can be averted. But barriers still block progress. Among the major sticking points is Iranian leaders’ insistence that Iran’s “right” to enrichment be explicitly and formally acknowledged by the United States and the other nations in the so-called P5+1 (China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Germany). While it is a fact that Iran has enrichment facilities, it is not a foregone conclusion that Iran has earned a right or should be given a right to enrichment without meeting its obligations. Enrichment is a dual-use technology: capable of being used to make low enriched uranium for nuclear fuel for reactors or highly enriched uranium for nuclear weapons.

Iran has consistently pointed to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) itself as using the word “right.” Indeed, the beginning of Article IV of the NPT states, “Nothing in this Treaty shall be interpreted as affecting the inalienable right of all the Parties to the Treaty to develop research, production and use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.” [Emphasis added.] But rights come with responsibilities. In particular, the remaining part of the first sentence of Article IV concludes: “without discrimination and in conformity with articles I and II of this Treaty.” Article I puts responsibility on the nuclear weapon states not to transfer nuclear explosives or assist a non-nuclear weapon state in manufacturing such explosives. Article II places responsibility on the non-nuclear weapon states to not receive nuclear explosives or to manufacture such explosives. Article IV is also linked with Article III, in which non-nuclear weapon states have the obligation to apply comprehensive safeguards to their nuclear programs to ensure that those programs are peaceful. Nuclear weapon states can accept voluntary safeguards on the parts of their nuclear programs designated for peaceful purposes.

Iranian leaders have also often said that they want to be treated like Japan, which has enrichment and reprocessing facilities. But Japan has made the extra effort to apply advanced safeguards to these facilities. Specifically, it enacted the Additional Protocol to the Comprehensive Safeguards Agreement, which gives the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) access to a country’s entire nuclear program and requires the IAEA to assess whether there are any undeclared nuclear materials or facilities in that country. In effect, the IAEA must act like Sherlock Holmes investigating whether there is anything amiss throughout a nuclear program rather than acting like a green-eye shade wearing accountant who just checks the books. Iran had been voluntarily applying the Additional Protocol before early 2006 when its nuclear file was taken to the UN Security Council. Then Iran suspended application of these enhanced safeguards.

While the deal announced on November 11 between the IAEA and Iran to allow the IAEA additional access and information on selected facilities and activities, it does not go far enough. Iran has left out the Arak heavy water research reactor and the Parchin site, in particular. The Arak reactor, which could start operations next year, has the type of design well suited to being able to produce weapons-grade plutonium. If Iran had a covert hot cell to reprocess irradiated fuel from this reactor, it could extract at least one bomb’s worth of plutonium per year depending on the level of operations. The Parchin site has been suspected of previously being used for testing of high explosives that might be relevant for nuclear weapons design work. Iran has stated that this is a military site not related to nuclear work and thus off limits to IAEA inspectors. Arak and Parchin are just two outstanding examples of sites that raise concern about Iran’s intentions and potential capabilities.

Without a doubt, Iran has the right to pursue and use peaceful nuclear energy. But before it is given a formal right to continue with enrichment, it has to take adequate efforts to ensure that its nuclear program is fully transparent and well safeguarded. The United States and its allies would concomitantly have the obligation to help Iran meet its energy needs and remove sanctions that have been in place against Iran’s nuclear program.

Air Force Intelligence Report Provides Snapshot of Nuclear Missiles

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published its long-awaited update to the Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report, one of the few remaining public (yet sanitized) U.S. intelligence assessment of the world nuclear (and other) forces.

Previous years’ reports have been reviewed and made available by FAS (here, here, and here), and the new update contains several important developments – and some surprises.

Most important to the immediate debate about further U.S.-Russian reductions of nuclear forces, the new report provides an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

Another new development is a significant number of new conventional short-range ballistic missiles being deployed or developed by China.

Finally, several of the nuclear weapons systems listed in a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing are not included in the NASIC report at all. This casts doubt on the credibility of the AFGSC briefing and creates confusion about what the U.S. Intelligence Community has actually concluded.

Russia

The report estimates that Russia retains about 1,200 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs, slightly higher than our estimate of 1,050. That is probably a little high because it would imply that the SSBN force only carries about 220 warheads instead of the 440, or so, warheads we estimate are on the submarines.

“Most” of the ICBMs “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” the report states. This excessive alert posture is similar to that of the United States, which has essentially all of its ICBMs on alert.

The report also confirms that although Russia is developing and deploying new missiles, “the size of the Russia missile force is shrinking due to arms control limitations and resource constraints.”

Unfortunately, the report does not clear up the mystery of how many warheads the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) missile carries. Initially we estimated thee because the throw-weight is similar to the U.S. Minuteman III ICBM. Then we considered six, but have recently settled on four, as the Strategic Rocket Forces commander has stated.

The report states that “Russia tested a new type of ICBM in 2012,” but it undercuts rumors that it not an ICBM by listing its range as 5,500+ kilometers. Moreover, in an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile, the report concludes: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

The report also describes how Russian designers are working to modify missiles to overcome U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. The SS-27 Mod 1 (Topol-M) deployed in silos at Tatishchevo was designed with countermeasures to ballistic missile systems, and Russian officials claim that a new class of hypersonic vehicle is being developed to overcome ballistic missile defense systems, according to NASIC.

The report also refers to Russian press report that a rail-mobile ICBM is being considered, and that a new “heavy” ICBM is under development.

One of the surprises in the report is that SS-N-32/Bulava-30 missile on the first Borei-class SSBN is not yet considered fully operational – at least not by NASIC. The report lists the missile as in development and “not yet deployed.”

Another interesting status is that while the AS-4 and AS-15 nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missiles are listed as operational, the new Kh-102 nuclear cruise missile that Russian officials have said they’re introducing is not listed at all. The Kh-102 was also listed as already “fielded” by a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing.

Finally, while the report lists the SS-N-21 sea-launched cruise missile as operational, it does not mention the new Kalibr cruise missile for the Yasen-class attack submarine that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed a having been “fielded” within the past five years.

China

The NASIC report states that the Chinese ballistic missile force is expanding both in size and types of missiles.

Deployment of the DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) ICBM continues at a slow pace with “more than 15” launchers deployed six years after the system was first introduced.

Despite many rumors about a new DF-41 ICBM, the NASIC report does not mention this system at all.

Deployment of the shorter-range DF-31 (CSS-10 Mod 1) ICBM, on the contrary, appears to have stalled or paused, with only 5-10 launchers deployed seven years after it was initially introduced (see my recent analysis of this trend here). Moreover, the range of the DF-31 is lowered a bit, from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ in the new version.

Medium-range nuclear missiles include the DF-21 (CSS-5) (in two versions: Mod 1 and Mod 2, but with identical range etc.) and the old DF-3A (CSS-2), which is still listed as deployed. Only 5-10 launchers are left, probably in a single brigade that will probably convert to DF-21 in the near future.

An important new development concerns conventional missiles, where the NASIC report states that several new systems have been introduced or are in development. This includes a “number of new mobile, conventionally armed MRBMs,” apparently in addition to the DF-21C and DF-21D already known. As for the DF-21D anti-ship missile, report states that “China has likely started to deploy” the missile but that it is “unknown” how many are deployed.

More dramatic is the development on five new short-range ballistic missiles, including the CSS-9, CSS-11, CSS-14, CSS-X-15, and CSS-X-16. The CSS-9 and CSS-14 come in different versions with different ranges. The CSS-11 Mod 1 is a modification of the existing DF-11, but with a range of over 800 kilometers (500 miles). None of these systems are listed as nuclear-capable.

Concerning sea-based nuclear forces, the NASIC report echoes the DOD report by saying that the JL-2 SLBM for the new Jin-class SSBN is not yet operational. The JL-2 is designated as CSS-NX-14, which I thought it was a typo in the 2009 report, as opposed to the CSS-NX-3 for the JL-1 (which is also not operational).

NASIC concludes that JL-2 “will, for the first time, allow Chinese SSBNs to target portions of the United States from operating areas located near the Chinese coast.” That is true for Guam and Alaska, but not for Hawaii and the continental United States. Moreover, like the DF-31, the JL-2 range estimate is lowered from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ km in the new version. Earlier intelligence estimates had the range as high as 8,000+ km.

One of the surprises (perhaps) in the new report is that it does not list the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile, which was listed in the U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing as a nuclear cruise missile that had been “fielded” within the past five years.

Concerning the overall size of the Chinese nuclear arsenal, there have been many rumors that it includes hundreds or even thousands of additional warheads more than the 250 we estimate. STRATCOM commander has also rejected these rumors. To that end, the NASIC report lists all Chinese nuclear missiles with one warhead each, despite widespread rumors in the news media and among some analysts that multiple warheads are deployed on some missiles.

Yet the report does echo a projection made by the annual DOD report, that “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM capable of carrying a MIRV payload.” But NASIC does not confirm widespread news media rumors that this system is the DF-41 – in fact, the report doesn’t even mention the DF-41 as in development.

As for the future, the NASIC report repeats the often-heard prediction that “the number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 15 years.” This projection has continued to slip and NASIC slips it a bit further into the future to 2028.

Pakistan

Most of the information about the Pakistani system pretty much fits what we have been reporting. The only real surprise is that the Shaheen-II MRBM does still not appear to be fully deployed, even though the system has been flight tested six times since 2010. The report states that “this missile system probably will soon be deployed.”

India

The information on India also fits pretty well with what we have been reporting. For example, the report refers to the Indian government saying the Agni II IRBM has finally been deployed. But NASIC only lists “fewer than 10” Agni II launchers deployed, the first time I have seen a specific reference to how many of this system are deployed. The Agni III IRBM is said to be ready for deployment, but not yet deployed.

North Korea

The NASIC report lists the Hwasong-13 (KN-08), North Korea’s new mobile ICBM, but confirms that the missile has not yet been flight tested. It also lists an IRBM, but without naming it the Musudan.

The mysterious KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed as a new nuclear system expected within the next five years is not mentioned in the NASIC report.

Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2013

See also previous NASIC reports: 2009 | 2006 | 1998

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

War with Iran? Revisiting the Potentially Staggering Costs to the Global Economy

The Senate passage of Resolution 65 on May 22, 2013, some argue, draws the United States closer to military action against Iran. In October 2012, amid concerns that surprisingly little research addressed the potential broad outcomes of possible U.S.-led actions against Iran, researchers at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) assembled nine renowned subject matter experts (SMEs) to investigate one underexplored question that now, eight months later, looms larger than ever: What are the potential effects on the global economy of U.S. actions against Iran? Collectively representing expertise in national security, economics, energy markets, and finance, the SMEs gathered for a one-day elicitation workshop to consider the global economic impacts of six hypothetical scenarios involving U.S.-led actions.

The elicitation revealed the rough effects of U.S. action against Iran on the global economy – measured only in the first three months of actualization – to range from total losses of approximately $60 billion on one end of the scale to more than $2 trillion to the world economy on the other end.

The results of the elicitation were compiled into the FAS report written by Charles P. Blair and Mark Jansson, “Sanctions, Military Strikes, and Other Potential Actions Against Iran.”

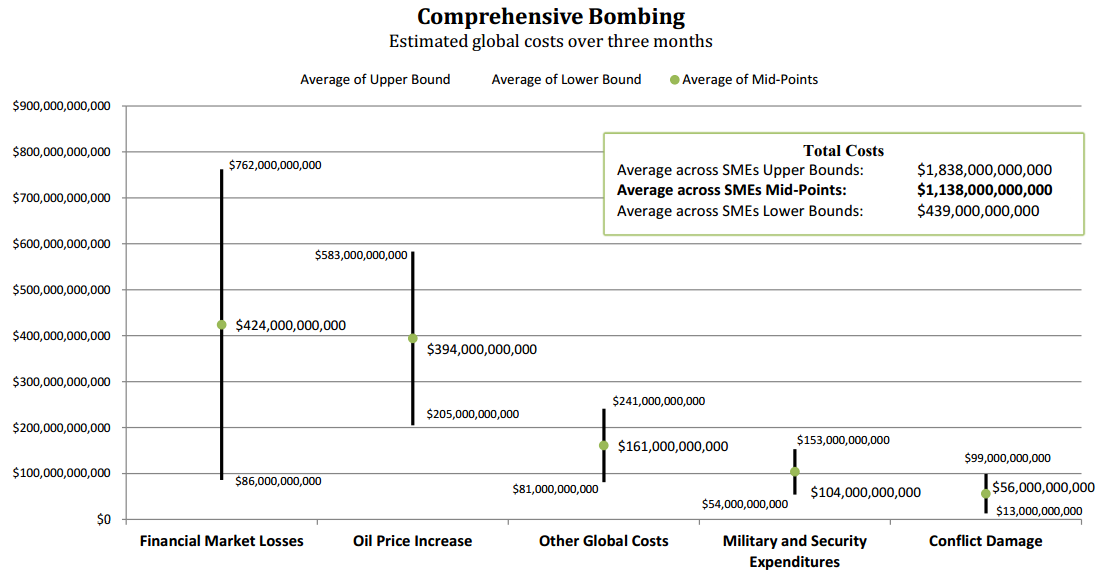

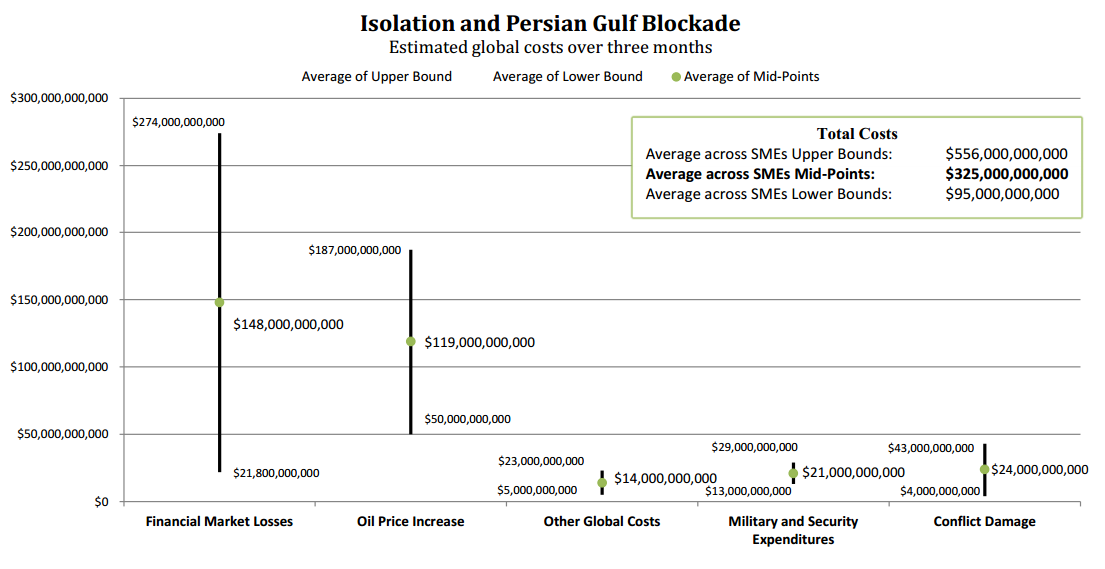

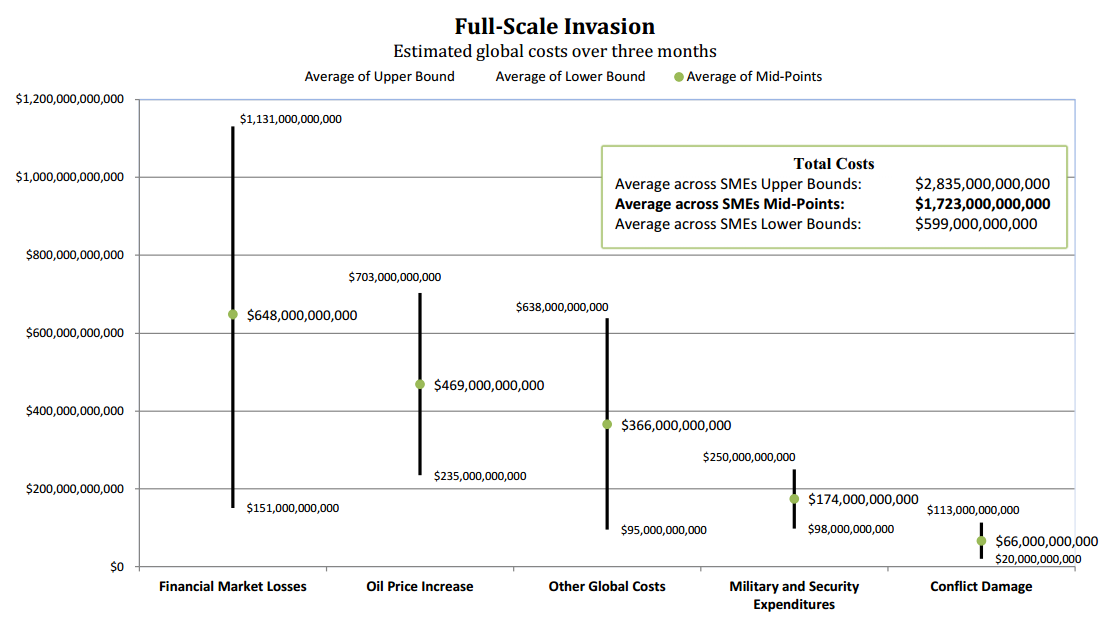

Summarized below are three of the six scenarios along with the associated estimated range of costs to the world economy in the first three months of U.S. action alone.

Scenario: Comprehensive Bombing Campaign (upper bounds of estimated costs to global economy: $1.7 trillion)

The president, not wanting to leave the job half-done and fearing that a more limited strike may not achieve all of its objectives or at too high a price should Iran retaliate, opts for a more thorough mission. The United States leads an ambitious air campaign that targets not only the nuclear facilities of concern but also seeks to limit Iran’s ability to retaliate by targeting its other military assets, including its air defenses, radar and aerial command and control facilities, and much of Iran’s direct retaliatory capabilities. These would include its main military bases, the main facilities of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and the Iranian Navy, Army, and Air Force. The United States seeks to ensure that the Strait of Hormuz remains open by targeting Iranian capabilities that may threaten it.

Scenario: Isolation and Persian Gulf Blockade – no military action (upper bounds of estimated costs to global economy: $550 billion)

Iran’s economy is reeling yet diplomatic agreement remains elusive. The United States, concerned that the Iranian regime has gone into survival mode, enacts what can be referred to as a “total cutoff” policy. The United States moves to curtail any exports of refined oil products, natural gas, energy equipment, and services. Investments in Iran’s energy sector are banned worldwide. Official trade credit guarantees are banned, as is international lending to Iran and investment in Iranian bonds. Insurance and reinsurance for all shipping going to and from Iran is prohibited. Substantial U.S. military assets are deployed to the Persian Gulf to block unauthorized shipments to and from Iran as well as to protect shipments of oil and other products through the Strait of Hormuz.

Scenario: Full-Scale Invasion (upper bounds of estimated costs to global economy: $2.8 trillion)

The United States resolves to invade, occupy, and disarm Iran. It carries out all of the above missions and goes “all in” to impose a more permanent solution by disarming the regime. Although the purpose of the mission is not explicitly regime change, the United States determines that the threat posed by Iran to Israel, neighboring states, and to freedom of shipping in the Strait of Hormuz cannot be tolerated any longer. It imposes a naval blockade and a no-fly zone as it systematically takes down Iran’s military bases and destroys its installations one by one. Large numbers of ground troops will be committed to the mission to get the job done.

Note: All opinions expressed here and in the report, as well as its findings, are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federation of American Scientists or any of the participants in the elicitation that served as the centerpiece of this study.

Regulating Japanese Nuclear Power in the Wake of the Fukushima Daiichi Accident

The 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was preventable. The Great East Japan earthquake and the tsunami that followed it were unprecedented events in recent history, but they were not altogether unforeseeable. Stronger regulation across the nuclear power industry could have prevented many of the worst outcomes at Fukushima Daiichi and will be needed to prevent future accidents.

In an FAS issue brief, Dr. Charles Ferguson and Mr. Mark Jansson review some of the major problems leading up to the accident and provides an overview of proposed regulatory reforms, including an overhaul of the nuclear regulatory bureaucracy and specific safety requirements which are being considered for implementation in all nuclear power plants.

New Report Analyzing Iran’s Nuclear Program Costs and Risks

Iran’s quest for the development of nuclear program has been marked by enormous financial costs and risks. It is estimated that the program’s cost is well over $100 billion, with the construction of the Bushehr reactor costing over $11 billion, making it one of the most expensive reactors in the world.

The Federation of American Scientists and the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace have released a new report, “Iran’s Nuclear Odyssey: Costs and Risks” which analyzes the economic effects of Iran’s nuclear program, and policy implications of sanctions and other actions by the United States and other allies. Co-authored by Ali Vaez and Karim Sadjadpour, the report details the history of the program, beginning with its inception under the Shah in 1957, and how the Iranian government has continue to grow their nuclear capabilities under a shroud of secrecy. Coupled with Iran’s limited supply of uranium and insecure stockpiles of nuclear materials, along with Iran’s desire to invest in nuclear energy to revitalize their energy sector (which is struggling due to international sanctions), the authors examine how these huge costs have led to few benefits.

The report analyzes the policy implications of Iran’s nuclear program for the United States and its allies, concluding that economic sanctions nor military force cannot end this prideful program; it is imperative that a diplomatic solution is reached to ensure that Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful. Finally, efforts need to be made to the Iranians from Washington which clearly state that America and its allies prefer a prosperous and peaceful Iran versus an isolated and weakened Iran. Public diplomacy and nuclear diplomacy must go hand in hand.

Iran and the Global Economy

The escalating confrontation between the United States and Iran over the latter’s nuclear program has triggered much debate about what actions should be taken to ensure that Iran does not develop a nuclear weapon. How might certain actions against Iran affect the global economy? FAS released the results of a study, “Sanctions, Military Strokes, and Other Potential Actions Against Iran” which assesses the global economic impact on a variety of conflict scenarios, sanctions and other alternative actions against Iran. FAS conducted an expert elicitation with nine subject matter experts involving six hypothetical scenarios in regards to U.S. led actions against Iran, and anticipated three month cost to the global economy. These scenarios ranged from increasing sanctions (estimated cost of U.S. $64 billion) to full-scale invasion of Iran (estimated cost of U.S. $1.7 trillion).

Sanctions and Nonproliferation in North Korea and Iran

The nuclear programs of North Korea and Iran have been, for many years, two of the most pressing and intractable security challenges facing the United States and the international community. While frequently lumped together as “rogue states,” the two countries have vastly different social, economic, and political systems, and the history and status of their nuclear and long-range missile programs differ in several critical aspects.

The international responses to Iranian and North Korean proliferation bear many similarities, particularly in the use of economic sanctions as a central tool of policy. Daniel Wertz, Program Officer at the National Committee on North Korea, and Dr. Ali Vaez, former Director of the Iran Project at the Federation of American Scientists, offer a comparative analysis of U.S. policy toward Iran and North Korea in a FAS issue.

IAEA Releases New Report on Iran’s Nuclear Program

Today, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) released a critical report that concluded while some of the suspected secret nuclear work by Iran may have peaceful purposes, others are specific to building nuclear weapons.