The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review: Arms Control Subdued By Military Rivalry

On 27 October 2022, the Biden administration finally released an unclassified version of its long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The classified NPR was released to Congress in March 2022, but its publication was substantially delayed––likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Compared with previous NPRs, the tone and content come closest to the Obama administration’s NPR from 2010. However, it contains significant adjustments because of the developments in Russia and China. (See also our global overview of nuclear arsenals)

Despite the challenges presented by Russia and China, the NPR correctly resists efforts by defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists to add nuclear weapons to the U.S. arsenal and delay the retirement of older types. Instead, the NPR seeks to respond with adjustments in the existing force posture and increase integration of conventional and nuclear planning.

Although Joe Biden during his presidential election campaign spoke strongly in favor of adopting no-first-use and sole-purpose policies, the NPR explicitly rejects both for now.

From an arms control and risk reduction perspective, the NPR is a disappointment. Previous efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals and the role that nuclear weapons play have been subdued by renewed strategic competition abroad and opposition from defense hawks at home.

Even so, the NPR concludes it may still be possible to reduce the role that nuclear weapons play in scenarios where nuclear use may not be credible.

Unlike previous NPRs, the 2022 version is embedded into the National Defense Strategy document alongside the Missile Defense Review.

Below is our summary and analysis of the major portions of the NPR:

The Nuclear Adversaries

The NPR identifies four potential adversaries for U.S. nuclear weapons planning: Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Of these, Russia and China are obviously the focus because of Russia’s large arsenal and aggressive behavior and because of China’s rapidly increasing arsenal. The NPR projects that “[b]y the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” This echoes previous statements from high-ranking US military leaders, including the former and incoming Commanders of US Strategic Command although the NPR appears less “the sky is falling.”

China: Given that the National Defense Strategy is largely focused on China, it is unsurprising that the NPR declares China to be “the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent.”

Echoing the findings of the previous year’s China Military Power Report, the NPR suggests that “[t]he PRC likely intends to possess at least 1,000 deliverable warheads by the end of the decade.” According to the NPR, China’s more diverse nuclear arsenal “could provide the PRC with new options before and during a crisis or conflict to leverage nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, including military provocations against U.S. Allies and partners in the region.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces.

Russia: The NPR presents harsh language about Russia, in particular surrounding its behavior around the invasion of Ukraine. In contrast to the Trump administration’s NPR, the assumptions surrounding a potential low-yield “escalate-to-deescalate” policy have been toned down; instead the NPR simply states that Russia is diversifying its arsenal and that it views its nuclear weapons as “a shield behind which to wage unjustified aggression against [its] neighbors.”

The review’s estimate of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons –– “up to 2,000 –– matches those of previous military statements. In 2021, the Defense Intelligence Agency concluded that Russia “probably possesses 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads.” The State Department said in April 2022 that the estimate includes retired weapons awaiting dismantlement. The subtle language differences reflect a variance in estimates between the different US military departments and agencies.

The NPR also suggests that “Russia is pursuing several novel nuclear-capable systems designed to hold the U.S. homeland or Allies and partners at risk, some of which are also not accountable under New START.” Given that both sides appear to agree that Russia’s new Sarmat ICBM and Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle fit smoothly into the treaty, this statement is likely referring to Russia’s development of its Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, its Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, and its Status-6 Poseidon nuclear torpedo.

It appears that Russia and the United States are at odds over whether these three systems are treaty-accountable weapons. In 2019, then-Under Secretary Andrea Thompson noted during congressional testimony that all three “meet the US criteria for what constitutes a “new kind of strategic offensive arms’ for purposes of New START.” However, Russian officials had previously sent a notice to the United States stating that they “find it inappropriate to characterize new weapons being developed by Russia that do not use ballistic trajectories of flight moving to a target as ‘potential new kinds of Russian strategic offensive arms.’ The arms presented by the President of the Russian Federation on March 1, 2018, have nothing to do with the strategic offensive arms categories covered by the Treaty.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces.

North Korea: In recent years, North Korea has been overshadowed by China and Russia in the U.S. defense debate. Nonetheless this NPR describes North Korea as a target for U.S. nuclear weapons planning. The NPR bluntly states: “Any nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its Allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime. There is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on North Korean nuclear forces.

Iran: The NPR also describes Iran even though it does not have nuclear weapons. Interestingly, although Iran is not in compliance with its NPT obligations and therefore does not qualify for the U.S. negative security assurances, the NPR declares that the United States “relies on non-nuclear overmatch to deter regional aggression by Iran as long as Iran does not possess nuclear weapons.”

Nuclear Declaratory Policy

The NPR reaffirms long-standing U.S. policy about the role of nuclear weapons but with slightly modified language. The role is: 1) Deter strategic attacks, 2) Assure allies and partners, and 3) Achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.

The NPR reiterates the language from the 2010 NPR that the “fundamental role” of U.S. nuclear weapons “is to deter nuclear attacks” and only in “extreme circumstances.” The strategy seeks to “maintain a very high bar for nuclear employment” and, if employment of nuclear weapons is necessary, “seek to end conflict at the lowest level of damage possible on the best achievable terms for the United States and its Allies and partners.”

Deterring “strategic” attacks is a different formulation than the “deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear attack” language in the 2018 NPR, but the new NPR makes it clear that “strategic” also accounts for existing and emerging non-nuclear attacks: “nuclear weapons are required to deter not only nuclear attack, but also a narrow range of other high consequence, strategic-level attacks.”

Indeed, the NPR makes clear that U.S. nuclear weapons can be used against the full spectrum of threats: “While the United States maintains a very high bar for the employment of nuclear weapons, our nuclear posture is intended to complicate an adversary’s entire decision calculus, including whether to instigate a crisis, initiate armed conflict, conduct strategic attacks using non-nuclear capabilities, or escalate to the use of nuclear weapons on any scale.”

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden spoke repeatedly in favor of a no-first-use and sole-purpose policy for U.S. nuclear weapons. But the NPR explicitly rejects both under current conditions. The public version of the NPR doesn’t explain why a no-first-use policy against nuclear attack is not possible, but it appears to trim somewhat the 2018 NPR language about an enhanced role of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear strategic attacks. And the stated goal is still “moving toward a sole purpose declaration” when possible in consultation with Allies and partners.

In that context the NPR reiterates previous “negative security assurances” that the United States “will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT [Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty] and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

“For all other states” the NPR warns, “there remains a narrow range of contingencies in which U.S. nuclear weapons may still play a role in deterring attacks that have strategic effect against the United States or its Allies and partners.” That potentially includes Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan.

Interestingly, the NPR states that “hedging against an uncertain future” is no longer a stated (formal) role of nuclear weapons. Hedging has been part of a strategy to be able to react to changes in the threat environment, for example by deploying more weapons or modifying capabilities. The change does not mean that the United States is no longer hedging, but that hedging is part of managing the arsenal, rather than acting as a role for nuclear weapons within US military strategy writ large.

The NPR reaffirms, consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy, that U.S. use of nuclear weapons must comply with the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) and that it is U.S. policy “not to purposely threaten civilian populations or objects, and the United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or objects in violation of LOAC.” That means that U.S. nuclear forces cannot attack cities per se (unless they contain military targets).

Nuclear Force Structure

The NPR reaffirms a commitment to the modernization of its nuclear forces, nuclear command and control and communication systems (NC3), and production and support infrastructure. This is essentially the same nuclear modernization program that has been supported by the previous two administrations.

But there are some differences. The NPR also identifies “current and planned nuclear capabilities that are no longer required to meet our deterrence needs.” This includes retiring the B83-1 megaton gravity bomb and cancelling the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). These decisions were expected and survived opposition from defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists.

Although the NPR has decided to move forward with retirement of the B83-1 bomb due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs, the NPR appears to hint at a replacement weapon “for improved defeat” of hard and deeply buried targets. The new weapon is not identified.

The NPR concludes that “SLCM-N was no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities.” This language is more subtle than the administration’s recent statement rebutting Congress’ attempt to fund the SLCM-N, which states:

“The Administration strongly opposes continued funding for the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) and its associated warhead. The President’s Nuclear PostureReview concluded that the SLCM-N, which would not be delivered before the 2030s, is unnecessary and potentially detrimental to other priorities. […] Further investment in developing SLCM-N would divert resources and focus from higher modernization priorities for the U.S. nuclear enterprise and infrastructure, which is already stretched to capacity after decades of deferred investments. It would also impose operational challenges on the Navy.

In justifying the cancelation of the SLCM-N, the NPR spells out the existing and future capabilities that adequately enable regional deterrence of Russia and China. This includes the W76-2 (the low-yield warhead for the Trident II D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile proposed and deployed under the Trump administration), globally-deployed strategic bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, and dual-capable fighter aircraft such as as the F-35A equipped with the new B61-12 nuclear bomb.

The NPR concludes that the W76-2 “currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use.” However, the review leaves the door open for its possible removal from the force structure in the future: “Its deterrence value will be re-evaluated as the F-35A and LRSO are fielded, and in light of the security environment and plausible deterrence scenarios we could face in the future.”

The review also notes that “[t]he United States will work with Allies concerned to ensure that the transition to modern DCA [dual-capable aircraft] and the B61-12 bomb is executed efficiently and with minimal disruption to readiness.” The release of the NPR coincides with the surprise revelation that the United States has sped up the deployment of the B61-12 in Europe. Previously scheduled for spring 2023, the first B61-12 gravity bombs will now be delivered in December 2022, likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Putin’s nuclear belligerency. Given that the Biden administration has previously taken care to emphasize that its modernization program and nuclear exercises are scheduled years in advance and are not responses to Russia’s actions, it is odd that the administration would choose to rush the new bombs into Europe at this time.

The NPR appears to link the non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe more explicitly to recent Russian aggression. “Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea in 2014, NATO has taken steps to ensure a modern, ready, and credible NATO nuclear deterrent.” While that is true, some of those steps were already underway before 2014 and would have happened even if Russia had not invaded Ukraine. This includes extensive modernizations at the bases and of the weapons and adding the United Kingdom to the nuclear storage upgrades. But the NPR also states that “Further steps are needed to fully adapt these forces to current and emerging security conditions,” including to “enhance the readiness, survivability and effectiveness of the DCA mission across the conflict spectrum, including through enhanced exercises…”

In the Pacific region, the NPR continues and enhances extended deterrence with U.S. capabilities and deepened consultation with Allies and partners. The role of Australia appears to be increasing. An overall goal is to “better synchronize the nuclear and non-nuclear elements of deterrence” and to “leverage Ally and partner non-nuclear capabilities that can support the nuclear nuclear deterrence mission.” The last part sounds similar to the so-called SNOWCAT mission in NATO where Allies support the nuclear strike mission with non-nuclear capabilities.

Nuclear-Conventional Integration

Although the integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities into strategic deterrence planning has been underway for years, the NPR seeks to deepen it further. It “underscores the linkage between the conventional and nuclear elements of collective deterrence and defense” and adopts “an integrated deterrence approach that works to leverage nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities to tailor deterrence under specific circumstances.”

This is not only intended to make deterrence more flexible and less nuclear focused when possible, but it also continues the strategy outlined in the 2010 NPR and 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons by relying more on new conventional capabilities.

According to the NPR, “Non-nuclear capabilities may be able to complement nuclear forces in strategic deterrence plans and operations in ways that are suited to their attributes and consistent with policy on how they are employed.” Although further integration will take time, the NPR describes “how the Joint Force can combine nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities in complementary ways that leverage the unique attributes of a multi-domain set of forces to enable a range of deterrence options backstopped by a credible nuclear deterrent.” An important part of this integration is to “better synchronize nuclear and non-nuclear planning, exercises, and operations.”

Beyond force structure issues, this effort also appears to be a way to “raise the nuclear threshold” by reducing reliance on nuclear weapons but still endure in regional scenarios where an adversary escalates to limited nuclear use. In contrast, the 2018 NPR sought low-yield non-strategic “nuclear supplements” for such a scenario, and specifically named a Russian so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” scenario as a potentially possibility for nuclear use.

Moreover, conventional integration can also serve to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear strategic attacks, and could therefore pave the way for a sole-purpose policy in the future (see also An Integrated Approach to Deterrence Posture by Adam Mount and Pranay Vaddi).

Finally, increasing conventional capabilities in deterrence planning also allows for deeper and better integration of Allies and partners without having to rely on more controversial nuclear arrangements.

A significant challenge of deeper nuclear-conventional integration in strategic deterrence is to ensure that it doesn’t blur the line between nuclear and conventional war and inadvertently increase nuclear signaling during conventional operations.

Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

The NPR correctly concludes that deterrence alone will not reduce nuclear dangers and reaffirms the U.S. commitment to arms control, risk reduction, and nonproliferation. It does so by stating that the United States will pursue “a comprehensive and balanced approach” that places “renewed emphasis on arms control, non-proliferation, and risk reduction to strengthen stability, head off costly arms races, and signal our desire to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons globally.”

The Biden administration’s review contains significantly more positive language on arms control than can be found in the Trump administration’s NPR. The NPR concludes that “mutual, verifiable nuclear arms control offers the most effective, durable and responsible path to achieving a key goal: reducing the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. strategy.”

In that vein, the review states a willingness to “expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START,” as well as an expansive recommitment to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty” (CTBT), and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). However, the authors take a negative view of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), stating that the United States does not “consider the TPNW to be an effective tool to resolve the underlying security conflicts that lead states to retain or seek nuclear weapons.”

Although the NPR states that “major changes” in the role of U.S. nuclear weapons against Russia and China will require verifiable reductions and constraints on their nuclear forces, it also concludes that there “is some opportunity to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our strategies for [China] and Russia in circumstances where the threat of a nuclear response may not be credible and where suitable non-nuclear options may exist or may be developed.” The NPR does not identify what those scenarios are.

Looking Ahead

Many of the activities described in the NPR are already well underway. Now that the NPR has been completed and published, the Pentagon will produce an NPR implementation plan that identifies specific decisions to be carried out.

Flowing from the reviews that were done in preparation of the NPR, the White House will move forward with an update to the nuclear weapons employment guidance. This guidance will potentially include changes to the strike plans and the assumptions and the assumptions and requirements that underpin them.

The Biden administration must use this opportunity to scrutinize more closely the simulations and analysis that U.S. Strategic Command is using to set nuclear force structure requirements.

––

Additional analysis can be found on our FAS Nuclear Posture Review Resource Page.

For an overview of global modernization programs, see our annual contribution to the SIPRI Yearbook and our Status of World Nuclear Forces webpage. Individual country profiles are available in various editions of the FAS Nuclear Notebook, which is published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and is freely available to the public.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

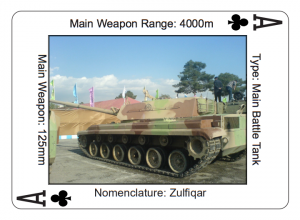

Army Playing Cards Feature Iranian Weapons

In a not very subtle sign of the times, the U.S. Army has produced a deck of playing cards featuring weaponry used or held by Iran in order to familiarize soldiers with Iran’s inventory of weapons and presumably to facilitate their recognition on the battlefield.

The Iran collection follows similar decks of playing cards illustrated with Chinese and Russian weapons.

Another set of U.S. Army playing cards featuring North Korean weapons systems is forthcoming.

Withdrawal from Iran Nuclear Deal: A Legal Analysis

The US is no longer complying with the Iran nuclear deal and is poised to re-impose some previously lifted sanctions on Iran and its trading partners.

But the legal basis for that action is a bit murky and contested. A new analysis from the Congressional Research Service tries to make legal sense of what has happened.

“The legal framework for withdrawal from an international pact depends on, among other features, the type of pact at issue and whether withdrawal is analyzed under domestic law or international law,” the report says. See Withdrawal from the Iran Nuclear Deal: Legal Authorities and Implications, CRS Legal Sidebar, May 17, 2018.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Iran’s Foreign and Defense Policies, updated May 23, 2018

Israel: Background and U.S. Relations In Brief, updated May 21, 2018

Bilateral and Regional Trade Agreements: Issues for Congress, May 17, 2018

Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of the Intelligence Community: Framework for Congressional Oversight In Brief, May 15, 2018

Military Construction: Process, Outcomes, and Frequently Asked Questions, updated May 16, 2018

The Federal Budget: Overview and Issues for FY2019 and Beyond, May 22, 2018

Violence Against Journalists in Mexico: In Brief, May 17, 2018

Venezuela’s 2018 Presidential Elections, CRS Insight, May 24, 2018

DACA Rescission: Legal Issues and Litigation Status, CRS Legal Sidebar, May 23, 2018

Coast Guard Polar Icebreaker Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, updated May 23, 2018

Advanced Pilot Training (T-X) Program: Background and Issues for Congress, updated May 21, 2018

The International Monetary Fund, updated May 24, 2018

Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs, updated May 24, 2018

Vehicle Fuel Economy and Greenhouse Gas Standards: Frequently Asked Questions, May 24, 2018

Is There Liability for Cross-Border Shooting?, CRS Legal Sidebar, May 22, 2018

Maritime Territorial and Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) Disputes Involving China: Issues for Congress, updated May 24, 2018

Internet Freedom in China: U.S. Government Activity, Private Sector Initiatives, and Issues of Congressional Interest, May 18, 2018

The Aftermath of US Withdrawal from the Iran Agreement

A new report from the Congressional Research Service begins to sort through the implications and the practical consequences of the Trump Administration decision to end US compliance with the Iran nuclear agreement, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA).

“The Trump Administration could have used provisions of the JCPOA itself to cease implementation of U.S. commitments under the agreement. It opted not to do so, but instead to cease implementing the JCPOA by reimposing U.S. sanctions,” the CRS report noted.

See U.S. Decision to Cease Implementing the Iran Nuclear Agreement, May 9, 2018.

For related background from CRS, see also Iran: U.S. Economic Sanctions and the Authority to Lift Restrictions, updated May 10, 2018; Withdrawal from International Agreements: Legal Framework, the Paris Agreement, and the Iran Nuclear Agreement, updated May 4, 2018; and Iran Nuclear Agreement, updated May 2, 2018.

The decision to unilaterally reimpose sanctions on Iran took the form of a National Security Presidential Memorandum (NSPM) on May 8. Although the NSPM posted on the White House website is unnumbered, the copy circulated to reporters was identified as NSPM-11.

It follows that the previous NSPM on conventional arms transfers, which was also unnumbered on the White House website, must have been NSPM 10.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Arms Control and Nonproliferation: A Catalog of Treaties and Agreements, updated May 8, 2018

Military Suicide Prevention and Response, CRS In Focus, April 30, 2018

Oil and Gas Activities Within the National Wildlife Refuge System, May 9, 2018

Civilian Nuclear Waste Disposal, updated May 9, 2018

High Intensity Drug Trafficking Areas (HIDTA) Program, May 3, 2018

From Slip Law to United States Code: A Guide to Federal Statutes for Congressional Staff, May 2, 2018

Covert Action and Clandestine Activities of the Intelligence Community: Selected Notification Requirements in Brief, May 7, 2018

The Director of National Intelligence (DNI), CRS In Focus, May 1, 2018

Iran: Politics, and More from CRS

Has the U.S. adopted a policy of regime change towards Iran? Government officials have sent different signals at different times.

In 2006, President George W. Bush called for a “free and democratic” Iran, which appeared to be an endorsement of regime change.

In 2013, President Obama explicitly disavowed a policy of regime change and referred to the country as the “Islamic Republic of Iran,” its post-revolutionary name, which was understood to convey recognition of the current Iranian leadership.

Most recently, the signals are mixed. “The Trump Administration has not adopted a policy of regime change, but there have been several Administration statements that indicate support for that outcome,” according to a newly updated report from the Congressional Research Service, which also takes note of the recent political protests in Iran. See Iran: Politics, Human Rights, and U.S. Policy, updated January 8, 2018.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Libya: Transition and U.S. Policy, updated January 8, 2018

The U.S. Export Control System and the Export Control Reform Initiative, updated January 8, 2018

A Balanced Budget Constitutional Amendment: Background and Congressional Options, updated January 8, 2018

Monetary Policy and the Federal Reserve: Current Policy and Conditions, updated January 9, 2018

Budget Enforcement Procedures: The Senate Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) Rule, updated January 9, 2018

Smart Toys and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998, CRS Legal Sidebar, January 8, 2018

Protecting Consumers and Businesses from Fraudulent Robocalls, January 5, 2018

Drug Compounding: FDA Authority and Possible Issues for Congress, January 5, 2018

Defense Primer: Under Secretary of Defense (Intelligence), CRS In Focus, updated January 3, 2018

Iran 1953 Covert History Quietly Released

The Department of State yesterday released a long-suppressed volume of historical records documenting the role of the United States in the 1953 coup against the Iranian government of Mohammad Mosadeq.

“This retrospective volume focuses on the evolution of U.S. thinking on Iran as well as the U.S. Government covert operation that resulted in Mosadeq’s overthrow on August 19, 1953,” the Preface says. See Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1952-1954, Iran, 1951-1954.

“This volume includes National Security Council and Presidential materials that document the U.S. decision to proceed with the operation against Mosadeq, and the operational files within the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that document the implementation of the operation, codenamed TPAJAX.”

Some of the relevant records were destroyed long ago.

“The original CIA cables relating to the implementation of the covert action TPAJAX no longer exist. The original TPAJAX operational cables appear to have been destroyed as part of an office purge undertaken in 1961 or 1962, in anticipation of Near East (NE) Division’s move to the Central Intelligence Agency’s new headquarters.”

However, “Department of State historians obtained hand-typed transcriptions of microfilmed copies of these cables” and “twenty-one are published in this volume and an additional seven are referenced in footnotes.”

A small portion of the 1,000-page collection remains classified.

“The declassification review of this volume, which began in 2004 and was completed in 2014, resulted in the decision to withhold 10 documents in full, excise a paragraph or more in 38 documents, and make minor excisions of less than a paragraph in 82 documents,” the editors wrote. Without knowing for certain, some of the withheld information may pertain to discussion of British involvement in the operation, as well as technical details such as cryptonyms.

Rectifying a “Fraud”

The release of the Iran history volume is the culmination — and apparently the resolution — of decades of controversy that began in 1989 after the Department published a FRUS volume on US-Iran relations between 1951 and 1954 that neglected to mention any covert operation against the Iran government. That earlier volume was widely denounced by US historians and others.

“The omissions combine to make the Iran volume in the period of 1952–54 a fraud,” wrote historian Bruce R. Kuniholm in 1990.

“This is ‘Hamlet’ without the Prince of Denmark — or the ghost,” the New York Times editorialized back then.

Over time, the State Department itself came to agree with that critical assessment.

“The Department’s self-censorship exemplified, but also obscured, the restrictive impulses toward historical transparency that prevailed throughout the U.S. Government” at the time, according to a candid and thoughtful State Department history of the Foreign Relations series. “FRUS historians could have been more assertive in their efforts to promote greater openness in the 1980s. They should have recognized that the [1989] Iran volume was too incomplete to be published without damaging the series’s reputation.”

On the plus side, “Academic criticism of the [1989] ‘Iran Volume’ and the restrictions placed on [advisory committee] access to classified material raised public and congressional awareness of the erosion of transparency in the 1980s.”

This in turn led to enactment in 1991 of a new statutory requirement that the FRUS series must provide “a thorough, accurate, and reliable documentary record of major United States foreign policy.”

But at the end of the Obama Administration, and as recently as April of this year, release of the Iran retrospective volume seemed to be indefinitely blocked.

In 2016, “the Department of State did not permit publication of the long-delayed Iran Retrospective volume because it judged the political environment too sensitive,” the Department’s Historical Advisory Committee (HAC) wrote in its latest annual report. “The HAC was unsuccessful in its efforts to meet with [then-]Secretary Kerry to discuss the volume, and now there is no timetable for its release.”

And then yesterday, all of a sudden and with minimal notice, it was posted online. The publication was welcomed by the chair of the Historical Advisory Committee, Temple University historian Richard H. Immerman.

“As it expressed in last year’s annual report, the HAC was repeatedly frustrated–and disappointed–by Secretary Kerry’s refusal to allow the volume’s publication,” Prof. Immerman said yesterday. “In this regard the change in State’s perspective from the Obama to Trump administration is dramatic.”

There is no known evidence that Secretary of State Tillerson participated in the decision to permit publication. But, an official said, “there is no question that receiving approval to publish the volume was much less difficult with the change of administrations. Indeed, it encountered remarkably little resistance.”

Evidently wishing to downplay its significance, however, the State Department buried an announcement of the new volume at the bottom of a June 15 press release. After listing 16 other publications, it briefly mentioned that the Iran retrospective volume had “also” been released, making no mention of the decades-long controversy leading up to its publication.

Needless to say, the sky has not fallen due to the disclosure, and is not expected to. US relations with Iran will remain as fraught in the near future as they have been in the recent past. (The Senate voted yesterday 98-2 in favor of sanctions on Iran in connection with that country’s “ballistic missile program, support for acts of international terrorism, and violations of human rights.”)

But a pointless and misleading omission in the historical record has now been rectified.

“The public and scholarly community owes a great debt to not only the remarkable effort and perseverance of literally generations of State Department historians and the [History] Office’s leadership, but also their collective commitment to historical accuracy and transparency,” said Prof. Immerman.

Garwin on Strategic Security Challenges to the US

There are at least four major “strategic security challenges” that could place the United States at risk within the next decade, physicist Richard L. Garwin told the National Academy of Sciences earlier this month.

“The greatest threat, based on expected value of damage, is cyberattack,” he said. Other challenges arise from the actions of North Korea and Iran, due to their pursuit or acquisition of nuclear weapons and/or missiles. The remaining threat is due to the potential instability associated with the existing U.S. nuclear weapon arsenal.

These four could be ordered, he said, by the relative difficulty of reducing the threat, from “easiest” to hardest: “the Iranian nuclear program; North Korea; the U.S. nuclear weapon capability and its evolution; and, finally, most importantly and probably most difficult of solution, the cyber threat to the United States.”

In his remarks, Garwin characterized each of the challenges and discussed possible steps that could be taken to mitigate the hazards involved. See Strategic Security Challenges for 2017 and Beyond, May 1, 2017.

Among many other things, Dr. Garwin is a former board member of the Federation of American Scientists. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama last November. He was the subject of a biography published earlier this year called True Genius by Joel Shurkin. Many of his publications are archived on the FAS website.

Most of the threats identified by Garwin — other than the one posed by the U.S. nuclear weapon arsenal — were also discussed in the Worldwide Threat Assessment of the US Intelligence Community that was presented to the Senate Intelligence Committee on May 11.

Neither Garwin nor the US Intelligence Community considered the possibility that the US Government could ever be threatened from within. But that is what is now happening, former Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper told CNN on May 14.

“I think […] our institutions are under assault internally,” Clapper said, referring to recent actions by President Trump, including the abrupt termination of FBI director James Comey. “The founding fathers, in their genius, created a system of three co-equal branches of government and a built-in system of checks and balances,” he said. “I feel as though that is under assault and is eroding.”

History of Iran Covert Action Deferred Indefinitely

A declassified U.S. Government documentary history of the momentous 1953 coup in Iran, in which Central Intelligence Agency personnel participated, had been the object of widespread demand from historians and others for decades. In recent years, it finally seemed to be on the verge of publication.

But now its release has been postponed indefinitely.

Last year, “the Department of State did not permit publication of the long-delayed Iran Retrospective volume because it judged the political environment too sensitive,” according to a new annual report from the State Department Historical Advisory Committee (HAC). “The HAC was severely disappointed.”

“The HAC was unsuccessful in its efforts to meet with [then-]Secretary Kerry to discuss the volume, and now there is no timetable for its release,” the new report stated.

The controversy originally arose in 1989 when the State Department published its official history of US foreign relations with Iran that somehow made no mention of the 1953 CIA covert action against the Mossadeq government, triggering protests and ridicule.

That lapse led to enactment of a 1992 statute requiring the Foreign Relations of the United States series to present a “thorough, accurate, and reliable” documentary history of US foreign policy. The State Department also agreed to prepare a supplemental retrospective volume on Iran to correct the record. The retrospective volume is what now appears to be out of reach.

In truth, a fair amount of documentation related to the events of 1953 in Iran has been declassified and released. It is unclear how much more of significance remains to be disclosed. (Those who have read the missing volume say there is at least some new substance to it.)

But the position taken by the Obama State Department that 60 year old policy documents are too politically sensitive to be released is disheartening in any case.

Instead of disrupting relations with Iran, which are already fraught, an honest official U.S. account of events in 1953 might actually have elicited a constructive response. But that argument, advanced by the Historical Advisory Committee and its Chairman, Prof. Richard H. Immerman, did not get the serious consideration it deserved.

More broadly, the new annual report of the HAC did identify a few bright spots. One volume of the Foreign Relations series that was released last year met the statutory deadline for publication within 30 years of the events it describes. That hasn’t happened for two decades.

Overall, however, “the declassification environment is discouraging,” the HAC report found.

Countering the Islamic State, and More from CRS

Some 60 nations and partner organizations have made commitments to help counter the Islamic State with military forces or resources, according to a new report from the Congressional Research Service.

But coalition efforts suffer from a lack of coherence, CRS said. “Without a single authority responsible for prioritizing and adjudicating between different multinational civilian and military lines of effort, different actors often work at cross-purposes without intending to do so.”

CRS tabulated the contributions of each of the coalition partners by country and capability. “Each nation is contributing to the coalition in a manner commensurate with its national interests and comparative advantage, although reporting on nonmilitary contributions tends to be sporadic,” the report said.

“Some illustrative examples of the kinds of counter-IS assistance countries provided as the coalition was being formed in September 2014 include: Switzerland’s donation $9 million in aid to Iraq, Belgium’s contribution of 13 tons of aid to Iraq generally, Italy’s contribution of $2.5 million of weaponry (including machine guns, rocket-propelled grenades and a million rounds of ammunition), and Japan’s granting of $6 million in emergency aid to specifically help displaced people in Northern Iraq.” See Coalition Contributions to Countering the Islamic State, August 4, 2015.

*

The history and legal status of the U.S. military base in Guantanamo Bay were reviewed in another new CRS report.

“The origins of the U.S. military installation at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, lie in the execution of military operations during the Spanish-American War of April-August of 1898,” the report explained. Subsequent lease agreements signed in 1903 and 1934 “acknowledged Cuban sovereignty” over the site of the military base “but granted to the United States ‘complete jurisdiction and control over’ the property as long as it remained occupied.”

The existing leases “can only be modified or abrogated pursuant to an agreement between the United States and Cuba. The territorial limits of the naval station remain as they were in 1934 unless the United States abandons Guantanamo Bay or the two governments reach an agreement to modify its boundaries. While there appears to be no consensus on whether the President can modify the agreement alone, Congress is empowered to alter by statute the effect of the underlying 1934 treaty. There is no current law that would expressly prohibit the negotiation of lease modifications with the existing government of Cuba.”

However, “Congress has imposed practical impediments to closing the naval station by, for example, restricting the transfer of detainees from Guantanamo Bay to foreign countries.” See Naval Station Guantanamo Bay: History and Legal Issues Regarding Its Lease Agreements, August 4, 2015.

*

Many of the issues raised by the pending Iran nuclear agreement that Congress is likely to consider were itemized and described in another new CRS report obtained by Secrecy News.

“These issues include those related to monitoring and enforcing the agreement itself, how the sanctions relief provided by the agreement would affect Iran’s regional and domestic policies, the implications for regional security, and the potential for the agreement to change the course of U.S.-Iran relations,” the report said.

See Iran Nuclear Agreement: Selected Issues for Congress, August 6, 2015.

*

Other new and updated CRS reports that Congress has declined to make publicly available online include the following.

Procedures for Congressional Action in Relation to a Nuclear Agreement with Iran: In Brief, updated August 5, 2015

Iran Sanctions, updated August 4, 2015

History of the Navy UCLASS (Unmanned Carrier Launched Airborne Surveillance and Strike aircraft) Program Requirements: In Brief, August 3, 2015

Federal Support for Reproductive Health Services: Frequently Asked Questions, August 4, 2015

Fetal Tissue Research: Frequently Asked Questions, July 31, 2015

The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act of 2008 (GINA), updated August 6, 2015

Specialty Drugs: Background and Policy Concerns, August 3, 2015

Social Security: The Trust Funds, updated August 5, 2015

Medicare Financial Status: In Brief, updated August 10, 2015

Presidential Permit Review for Cross-Border Pipelines and Electric Transmission, August 6, 2015

EPA’s Clean Power Plan: Highlights of the Final Rule, August 14, 2015

Libya: Transition and U.S. Policy, updated August 3, 2015

U.S. Trade Concepts, Performance, and Policy: Frequently Asked Questions, updated August 3, 2015

National Security Letters in Foreign Intelligence Investigations: A Glimpse at the Legal Background, updated July 31, 2015

Nuclear Cooperation with Other Countries: A Primer, updated August 5, 2015

Six Achievable Steps for Implementing an Effective Verification Regime for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran

Now that an agreement has been reached between the P5+1 and Iran, a non-partisan task force convened by FAS has published Six Achievable Steps for Implementing an Effective Verification Regime for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran, a report that addresses anticipated implementation challenges and offers findings and recommendations for strengthening the implementation process both internationally and within the United States.

Over the last 20 months, Iran has been in negotiations with the P5+1 regarding its nuclear program, culminating in an agreement on July 14, 2015 that was memorialized in a 159-page text. The essence of the agreement is that Iran has offered the P5+1 constraints on its nuclear program in exchange for sanctions relief. As part of these negotiations, in paragraph iii of the Preamble and General Conditions, “Iran reaffirms that under no circumstances will Iran ever seek, develop or acquire any nuclear weapons.”

The negotiation process and the resulting agreement posed a critical question for the United States’ political and scientific communities: What monitoring and verification measures and tools will the United States, its allies, and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) require for a comprehensive and effective nuclear agreement with Iran? Although it is resoundingly clear that this issue is a sensitive and controversial one and there is discrepancy on the “wisdom, scope, and content” of a possible agreement with Iran, there does appear to be a general consensus that effective implementation is as important as the agreement itself, and an agreement with Iran without effective verification and monitoring measures “would be counterintuitive and dangerous” and would have negative long-term effects for all associated parties.

To examine and scrutinize these issues, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) convened the Verification Capabilities Independent Task Force that released a report last September titled Verification Requirements for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran. This new report, Six Achievable Steps for Implementing an Effective Verification Regime for a Nuclear Agreement with Iran, further dissects the issue and discusses potential strategies for successful implementation of the verification regime associated with the recent agreement.

This phase of the Task Force’s study focuses on the anticipation of implementation challenges and offers findings and recommendations for strengthening the implementation process both internationally and within the United States. The report emphasizes six feasible steps for executing a strong verification regime for a nuclear agreement with Iran:

- Ensure that the Joint Commission Works Effectively Among the P5+1 and Iran to Facilitate Compliance and Communication

- Organize Executive Branch Mechanisms to Create Synergy and Sustain Focus on Implementation Over the Long-Term

- Support and Augment the IAEA in the Pursuit of its Key Monitoring Role

- Create a Joint Executive-Congressional Working Group (JECWG) to Facilitate Coordination Across the Legislative and Executive Branches of the USG

- Prepare a Strategy and Guidebook for Assessing and Addressing Ambiguities and Potential Noncompliance

- Exploit New Technologies and Open Source Tools for Monitoring a Nuclear Agreement with Iran

The report was released to the public on Thursday, August 6, 2015 and the Task Force hosted a panel discussion in Washington, D.C. later that day to present their findings and discuss possible implications of the agreement. Over 50 attendees from the political, scientific, and NGO circles gathered to express their thoughts and share their opinions on the issue at hand.

In other relevant news regarding scientists and the agreement with Iran, 29 of the nation’s top scientists — including Nobel laureates, veteran makers of nuclear arms and former White House science advisers — wrote to President Obama on Saturday, August 8 to praise the Iran deal, calling it “innovative and stringent.” While many of those who signed the letter are prominent FAS members and affiliates, such as the lead writer Dr. Richard L. Garwin, who serves on the FAS Board of Directors, Dr. Frank von Hippel, who has served as chairman of the FAS Board, and Dr. Martin Hellman, who is an FAS adjunct senior fellow, FAS, as an organization, has not taken an organizational stance either for or against the deal. As indicated by the report released by FAS on August 6, the Task Force convened by FAS supports providing research, guidance, and recommendations for implementing an effective verification regime for a nuclear agreement with Iran. Scientists with nuclear expertise and scientifically credible analysis must continue to serve as essential components to a strong nonproliferation system that allows nations to use nuclear energy peacefully as long as safeguards commitments are upheld.

Iran Nuclear Deal: What’s Next?

By Muhammad Umar,

On July 14, 2015, after more than a decade of negotiations to ensure Iran only use its nuclear program for peaceful purposes, Iran and the P5+1 (US, UK, Russia, China, France + Germany) have finally agreed on a nuclear deal aimed at preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons.

Iran has essentially agreed to freeze their nuclear program for a period of ten years, as in there will be no new nuclear projects or research related to advanced enrichment processes. In exchange the West has agreed to lift crippling economic sanctions on Iran that have devastated the country for over a decade.

President Barack Obama said this deal is based on “verification” and not trust. This means that the sanctions will only be lifted after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has verified that Iran has fulfilled the requirements of the deal. Sanctions can be put back in place if Iran violates the deal in any way.

All though the details of the final agreement have not yet been released, based on the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) agreed to in April, some of the key parameters the IAEA will be responsible for verifying are that Iran has reduced the number of centrifuges currently in operation from 19,000 to 6,140, and does not enrich uranium over 3.67 percent for at least 15 years. The IAEA will also verify that Iran has reduced its current stockpile of low enriched uranium (LEU) from ~10,000 kg to 300 kg and does not build any new enrichment facilities. According to the New York Times, most of the LEU will be shipped to Russia for storage. Iran will only receive relief in sanctions if it verifiably abides by its commitments.

Even after the period of limitations on Iran’s nuclear program ends, it will remain a party to the NPT, its adherence to the Additional Protocol will be permanent, and it will maintain its transparency obligations.

The President must now submit the final agreement to the US Congress for a review. Once submitted, the Congress will have 60 days to review the agreement. There is no doubt that there will be plenty of folks in Congress who will challenge the agreement. Most of their concerns will be unwarranted because they lack a basic understanding of the technical details of the agreement.

The confusion for those opposing the deal on technical grounds is simple to understand. Iran had two paths to the bomb. Path one involved enriching uranium by using centrifuges, and path two involved using reactors to produce plutonium. The confusion is that if Iran is still allowed to have enriched uranium, and keep centrifuges in operation, will it not enable them to build the bomb?

The fact is that Iran will not have the number of centrifuges required to enrich weapons grade uranium. It will only enrich uranium to 3.7 percent and has a cap on its stockpile at 300 kilograms, which is inadequate for bomb making.

Again, the purpose of the deal is to allow greater access to the IAEA and their team of inspectors. They will verify that Iran complies with the agreement and in exchange sanctions will be lifted.

Congress does not have to approve the deal but can propose legislation that blocks the execution of the deal. In a public address, the President vowed to “veto any legislation that prevents the successful implementation of the deal.”

The deal will undergo a similar review process in Tehran, but because it has the support of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khameeni, there will be no objection.

Those opposing the deal in the United States fail to understand that although the deal is only valid for 10 to 15 years, the safeguards being put in place are permanent. Making it impossible for Iran to secretly develop a nuclear weapon.

This deal has potentially laid down a blueprint for future nuclear negotiations with countries like North Korea. Once the deal is implemented, it will serve as a testament for diplomacy. It is definitely a welcome change from the experience of failed military action in Iraq, a mess we cannot seem to get out of to this day.

A stable Iran with a strong economy will not only benefit the region but the entire world. The media as well as Congress should keep this fact in mind as they begin to review the details of the final deal.

This is a tremendous victory for the West as well as Iran. This deal has strengthened the non-proliferation regime, and has proven the efficacy of diplomacy.

The writer is a visiting scholar at the Federation of American Scientists. He tweets @umarwrites.

Dept of State Delays Release of Iran History

The U.S. Department of State has blocked the publication of a long-awaited documentary history of U.S. covert action in Iran in the 1950s out of concern that its release could adversely affect ongoing negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program.

The controversial Iran history volume, part of the official Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) series, had been slated for release last summer. (“History of 1953 CIA Covert Action in Iran to be Published,” Secrecy News, April 16, 2014).

But senior State Department officials “decided to delay publication because of ongoing negotiations with Iran,” according to the minutes of a September 8, 2014 meeting of the Advisory Committee on Historical Diplomatic Documentation that were posted on the Department of State website this week.

Dr. Stephen P. Randolph, the Historian of the State Department, confirmed yesterday that the status of the Iran volume “remains as it was in September” and that no new publication date has been set. The subject was also discussed at an Advisory Committee meeting this week.

The suppression of this history has been a source of frustration for decades, at least since the Department published a notorious 1989 volume on U.S. policy towards Iran that made no mention of CIA covert action.

But the latest move is also an indirect affirmation of the enduring significance of the withheld records, which date back even further than the U.S. rupture with Cuba that is now on the mend.

It seems that the remaining U.S. records of the 1953 coup in Iran are not only of historical interest but they evidently hold the power to move whole countries and to alter the course of events today. Or so the State Department believes.

“The logic, as I understand it, is that the release of the volume could aggravate anti-U.S. sentiment in Iran and thereby diminish the prospects of the nuclear negotiations reaching a settlement,” said Prof. Richard H. Immerman, a historian at Temple University and the chair of the State Department Historical Advisory Committee.

“I understand the State Department’s caution, but I don’t agree with the position,” he said. “Not only is the 1953 covert action in Iran an open secret, but it was also a motive for taking hostages in 1979. The longer the U.S. withholds the volume, the longer the issue will fester.”

Besides, if the documents do have an occult power to shape events, maybe that power could be harnessed to constructive ends.

“I would argue that our government’s commitment to transparency as signaled by the release of this volume could have a transformative effect on the negotiations, and that effect would increase the likelihood of a settlement,” Prof. Immerman suggested.

“At least some in the Iranian government would applaud this openness and seek to reciprocate. Further, the State Department of 2014 would distinguish this administration from the ‘Great Satan’ image of 1953 and after,” he said.

Continued secrecy has become an unnecessary obstacle to the development of US-Iran relations, argued historian Roham Alvandi in a similar vein in a New York Times op-ed (“Open the Files on the Iran Coup,” July 9, 2014).

“Moving forward with a new chapter in American-Iranian relations is difficult so long as the files on 1953 remain secret,” he wrote. “A stubborn refusal to release them keeps the trauma of 1953 alive in the Iranian public consciousness.”

*

The State Department published a new Foreign Relations of the United States volume today on the Arab-Israeli Dispute, 1978-80. It is the ninth FRUS volume of the year, and it came out “a little ahead of schedule,” said Dr. Randolph, the Department Historian.