Policy Experiment Stations to Accelerate State and Local Government Innovation

The federal government transfers approximately $1.1 trillion dollars every year to state and local governments. Yet most states and localities are not evaluating whether the programs deploying these funds are increasing community well-being. Similarly, achieving important national goals like increasing clean energy production and transmission often requires not only congressional but also state and local policy reform. Yet many states and localities are not implementing the evidence-based policy reforms necessary to achieve these goals.

State and local government innovation is a problem not only of politics but also of capacity. State and local governments generally lack the technical capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, search for reliable evidence about programs evaluated in other contexts, and implement the evidence-based programs with the highest chances of improving outcomes in their jurisdictions. This lack of capacity severely constrains the ability of state and local governments to use federal funds effectively and to adopt more effective ways of delivering important public goods and services. To date, efforts to increase the use of evaluation evidence in federal agencies (including the passage of the Evidence Act) have not meaningfully supported the production and use of evidence by state and local governments.

Despite an emerging awareness of the importance of state and local government innovation capacity, there is a shortage of plausible strategies to build that capacity. In the words of journalist Ezra Klein, we spend “too much time and energy imagining the policies that a capable government could execute and not nearly enough time imagining how to make a government capable of executing them.”

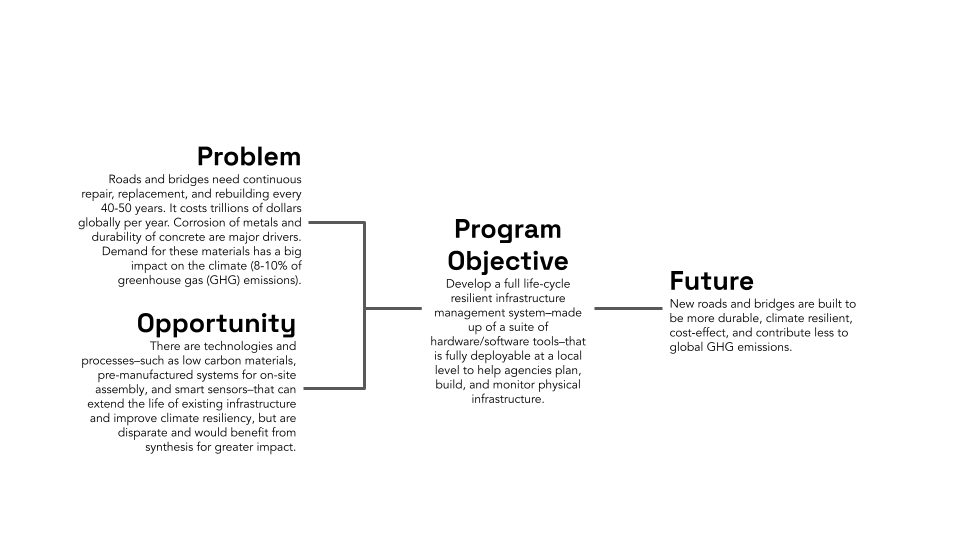

Yet an emerging body of research is revealing that an effective strategy to build government innovation capacity is to partner government agencies with local universities on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, curated syntheses of reliable evaluation evidence from other contexts, and implementation of evidence-based programs with the best chances of success. Leveraging these findings, along with recent evidence of the striking efficacy of the national network of university-based “Agriculture Experiment Stations” established by the Hatch Act of 1887, we propose a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations and tasked with accelerating state and local government innovation.

Challenge

Advocates of abundance have identified “failed public policy” as an increasingly significant barrier to economic growth and community flourishing. Of particular concern are state and local policies and programs, including those powered by federal funds, that do not effectively deliver critically important public goods and services like health, education, safety, clean air and water, and growth-oriented infrastructure.

Part of the challenge is that state and local governments lack capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their policies and programs. For example, the American Rescue Plan, the largest one-time federal investment in state and local governments in the last century, provided $350 billion in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to state, territorial, local, and Tribal governments to accelerate post-pandemic economic recovery. Yet very few of those investments are being evaluated for efficacy. In a recent survey of state policymakers, 59% of those surveyed cited “lack of time for rigorous evaluations” as a key obstacle to innovation. State and local governments also typically lack the time, resources, and technical capacity to canvass evaluation evidence from other settings and assess whether a program proven to improve outcomes elsewhere might also improve outcomes locally. Finally, state and local governments often don’t adopt more effective programs even when they have rigorous evidence that these programs are more effective than the status quo, because implementing new programs disrupts existing workflows.

If state and local policymakers don’t know what works and what doesn’t, and/or aren’t able to overcome even relatively minor implementation challenges when they do know what works, they won’t be able to spend federal dollars more effectively, or more generally to deliver critical public goods and services.

Opportunity

A growing body of research on government innovation is documenting factors that reliably increase the likelihood that governments will implement evidence-based policy reform. First, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are grounded in local evidence and/or recommended by local researchers. Boston-based researchers sharing a Boston-based study showing that relaxing density restrictions reduces rents and house prices will do less to convince San Francisco decision makers than either a San Francisco-based study, or San Francisco-based researchers endorsing the evidence from Boston. Proximity matters for government innovation.

Second, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are engaged as partners in the research projects that produce the evidence of efficacy, helping to define the set of feasible policy alternatives and design new policy interventions. Research partnerships matter for government innovation.

Third, evidence-based policies are significantly more likely to be adopted when the policy innovation is part of an existing implementation infrastructure, or when agencies receive dedicated implementation support. This means that moving beyond incremental policy reforms will require that state and local governments receive more technical support in overcoming implementation challenges. Implementation matters for government innovation.

We know that the implementation of evidence-based policy reform produces returns for communities that have been estimated to be on the order of 17:1. Our partners in government have voiced their direct experience of these returns. In Puerto Rico, for example, decision makers in the Department of Education have attributed the success of evidence-based efforts to help students learn to the “constant communication and effective collaboration” with researchers who possessed a “strong understanding of the culture and social behavior of the government and people of Puerto Rico.” Carrie S. Cihak, the evidence and impact officer for King County, Washington, likewise observes,

“It is critical to understand whether the programs we’re implementing are actually making a difference in the communities we serve. Throughout my career in King County, I’ve worked with County teams and researchers on evaluations across multiple policy areas, including transportation access, housing stability, and climate change. Working in close partnership with researchers has guided our policymaking related to individual projects, identified the next set of questions for continual learning, and has enabled us to better apply existing knowledge from other contexts to our own. In this work, it is essential to have researchers who are committed to valuing local knowledge and experience–including that of the community and government staff–as a central part of their research, and who are committed to supporting us in getting better outcomes for our communities.”

The emerging body of evidence on the determinants of government innovation can help us define a plan of action that galvanizes the state and local government innovation necessary to accelerate regional economic growth and community flourishing.

Plan of Action

An evidence-based plan to increase state and local government innovation needs to facilitate and sustain durable partnerships between state and local governments and neighboring universities to produce scientifically rigorous policy evaluations, adapt evaluation evidence from other contexts, and develop effective implementation strategies. Over a century ago, the Hatch Act of 1887 created a remarkably effective and durable R&D infrastructure aimed at agricultural innovation, establishing university-based Agricultural Experiment Stations (AES) in each state tasked with developing, testing, and translating innovations designed to increase agricultural productivity.

Locating university-based AES in every state ensured the production and implementation of locally-relevant evidence by researchers working in partnership with local stakeholders. Federal oversight of the state AES by an Office of Experiment Stations in the US Department of Agriculture ensured that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. Finally, providing stable annual federal appropriations for the AES, with required matching state appropriations, ensured the durability and financial sustainability of the R&D infrastructure. This infrastructure worked: agricultural productivity near the experiment stations increased by 6% after the stations were established.

Congress should develop new legislation to create and fund a network of state-based “Policy Experiment Stations.”

The 119th Congress that will convene on January 3, 2025 can adapt the core elements of the proven-effective network of state-based Agricultural Experiment Stations to accelerate state and local government innovation. Mimicking the structure of 7 USC 14, federal grants to states would support university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, tasked with partnering with state and local governments on (1) scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of state and local policies and programs; (2) translations of evaluation evidence from other settings; and (3) overcoming implementation challenges.

As in 7 USC 14, grants to support state policy innovation labs would be overseen by a federal office charged with ensuring that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. We see two potential paths for this oversight function, paths that in turn would influence legislative strategy.

Pathway 1: This oversight function could be located in the Office of Evaluation Sciences (OES) in the General Services Administration (GSA). In this case, the congressional committees overseeing GSA, namely the House Committee on Oversight and Responsibility and the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, would craft legislation providing for an appropriation to GSA to support a new OES grants program for university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that OES is a highly respected locus of program and policy evaluation expertise.

Pathway 2: Oversight could instead be located in the Directorate of Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships in the National Science Foundation (NSF TIP). In this case, the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation would craft legislation providing for a new grants program within NSF TIP to support university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that NSF is a highly respected grant-making agency.

Either of these paths is feasible with bipartisan political will. Alternatively, there are unilateral steps that could be taken by the incoming administration to advance state and local government innovation. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) recently released updated Uniform Grants Guidance clarifying that federal grants may be used to support recipients’ evaluation costs, including “conducting evaluations, sharing evaluation results, and other personnel or materials costs related to the effective building and use of evidence and evaluation for program design, administration, or improvement.” The Uniform Grants Guidance also requires federal agencies to assess the performance of grant recipients, and further allows federal agencies to require that recipients use federal grant funds to conduct program evaluations. The incoming administration could further update the Uniform Grants Guidance to direct federal agencies to require that state and local government grant recipients set aside grant funds for impact evaluations of the efficacy of any programs supported by federal funds, and further clarify the allowability of subgrants to universities to support these impact evaluations.

Conclusion

Establishing a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations, is an evidence-based plan to facilitate abundance-oriented state and local government innovation. We already have impressive examples of what these policy labs might be able to accomplish. At MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab North America, the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab and Education Lab, the University of California’s California Policy Lab, and Harvard University’s The People Lab, to name just a few, leading researchers partner with state and local governments on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of public policies and programs, the translation of evidence from other settings, and overcoming implementation challenges, leading in several cases to evidence-based policy reform. Yet effective as these initiatives are, they are largely supported by philanthropic funds, an infeasible strategy for national scaling.

In recent years we’ve made massive investments in communities through federal grants to state and local governments. We’ve also initiated ambitious efforts at growth-oriented regulatory reform which require not only federal but also state and local action. Now it’s time to invest in building state and local capacity to deploy federal investments effectively and to galvanize regional economic growth. Emerging research findings about the determinants of government innovation, and about the efficacy of the R&D infrastructure for agricultural innovation established over a century ago, give us an evidence-based roadmap for state and local government innovation.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Promoting American Resilience Through a Strategic Investment Fund

Critical minerals, robotics, advanced energy systems, quantum computing, biotechnology, shipbuilding, and space are some of the resources and technologies that will define the economic and security climate of the 21st century. However, the United States is at risk of losing its edge in these technologies of the future. For instance, China processes the vast majority of the world’s batteries and critical metals and has successfully launched a quantum communications satellite. The implications are enormous: the U.S. relies on its qualitative technological edge to fuel productivity growth, improve living standards, and maintain the existing global order. Indeed, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and CHIPS Act were largely reactionary moves to shore up atrophied manufacturing capabilities in the American battery and semiconductor industries, requiring hundreds of billions in outlays to catch up. In an ideal world, critical industries would be sufficiently funded well in advance to avoid economically costly catch-up spending.

However, many of these technologies are characterized by long timelines, significant capital expenditures, and low and uncertain profit margins, presenting major challenges for private-sector investors who are required by their limited partners (capital providers such as pension funds, university endowments, and insurance companies) to underwrite to a certain risk-adjusted return threshold. This stands in contrast to technologies like artificial intelligence and pharmaceuticals: While both are also characterized by large upfront investments and lengthy research and development timelines, the financial payoffs are far clearer, incentivizing private sectors to play a leading role in commercialization. This issue for technologies in economically and geopolitically vital industries such as lithium processing and chips is most acute in the “valley of death,” when companies require scale-up capital for an early commercialization effort: the capital required is too large for traditional venture capital, yet too risky for traditional project finance.

The United States needs a strategic investment fund (SIF) to shepherd promising technologies in nationally vital sectors through the valley of death. An American SIF is not intended to provide subsidies, pick political winners or losers, or subvert the role of private capital markets. On the contrary, its role would be to “crowd in” capital by uniquely managing risk that no private or philanthropic entities have the capacity to do. In doing so, an SIF would ensure that the U.S. maintains an edge in critical technologies, promoting economic dynamism and national security in an agile, cost-efficient manner.

Challenges

The Need for Private Investment

A handful of resources and technologies, some of which have yet to be fully characterized, have the potential to play an outsized role in the future economy. Most of these key technologies have meaningful national security implications.

Since ChatGPT’s release in November 2022, artificial intelligence (AI) has experienced a commercial renaissance that has captured the public’s imagination and huge sums of venture dollars, as evidenced by OpenAI’s October 2024 $6.5 billion round at a $150 billion pre-money valuation. However, AI is not the only critical resource or technology that will power the future economy, and many of those critical resources and technologies may struggle to attract the same level of private investment. Consider the following:

- To meet climate goals, the world needs to increase production of lithium by nearly 475%, rare earths by 100%, and nickel by 60% through 2035. For defense applications, rare earths are especially important; the construction of one F-35, for instance, uses 920 pounds of rare earth materials.

- The conflict in Ukraine has unequivocally demonstrated the value of low-cost drones on the battlefield. However, drones also have significant commercial applications, including safety and last-mile delivery. Reducing production and component costs could make a meaningful difference.

- Quantum technology has the potential to exponentially expand compute power, which can be used to simulate biological pathways, accelerate materials development, and process vast amounts of financial data. However, quantum technology can also be used to break existing encryption technologies and safeguard communications. China launched its first quantum communications satellite in 2020.

Few sectors receive the level of consistent venture attention that software technology, most recently in AI, has gotten in the last 18 months. However, this does not make them unbackable or unimportant; on the contrary, technologies that increase mineral recovery yields or make drone engines cheaper should receive sufficient support to get to scale. While private-sector capital markets have supported the development of many important industries, they are not perfect and may miss important opportunities due to information asymmetries and externalities.

Overcoming the Valley of Death

Many strategically important technologies are characterized by high upfront costs and low or uncertain margins, which tends to dissuade investment by private-sector organizations at key inflection points, namely, the “valley of death.”

By their nature, innovative technologies are complex and highly uncertain. However, some factors make future economic value—and therefore financeability—more difficult to ascertain than others. For example, innovative battery technologies that enable long-term storage of energy generated from renewables would greatly improve the economics of utility-scale solar and wind projects. However, this requires production at scale in the face of potential competition from low-cost incumbents. In addition, there is the element of scientific risk itself, as well as the question of customer adoption and integration. There are many good reasons why technologies and companies that seem feasible, economical, and societally valuable do not succeed.

These dynamics result in lopsided investment allocations. In the early stages of innovation, venture capital is available to fund startups with the promise of outsized return driven partially by technological hype and partially by the opportunity to take large equity stakes in young companies. At the other end of the barbell, private equity and infrastructure capital are available to mature companies seeking an acquisition or project financing based on predictable cash flows and known technologies.

However, gaps appear in the middle as capital requirements increase (often by an order of magnitude) to support the transition to early commercialization. This phenomenon is called the “valley of death” as companies struggle to raise the capital they need to get to scale given the uncertainties they face.

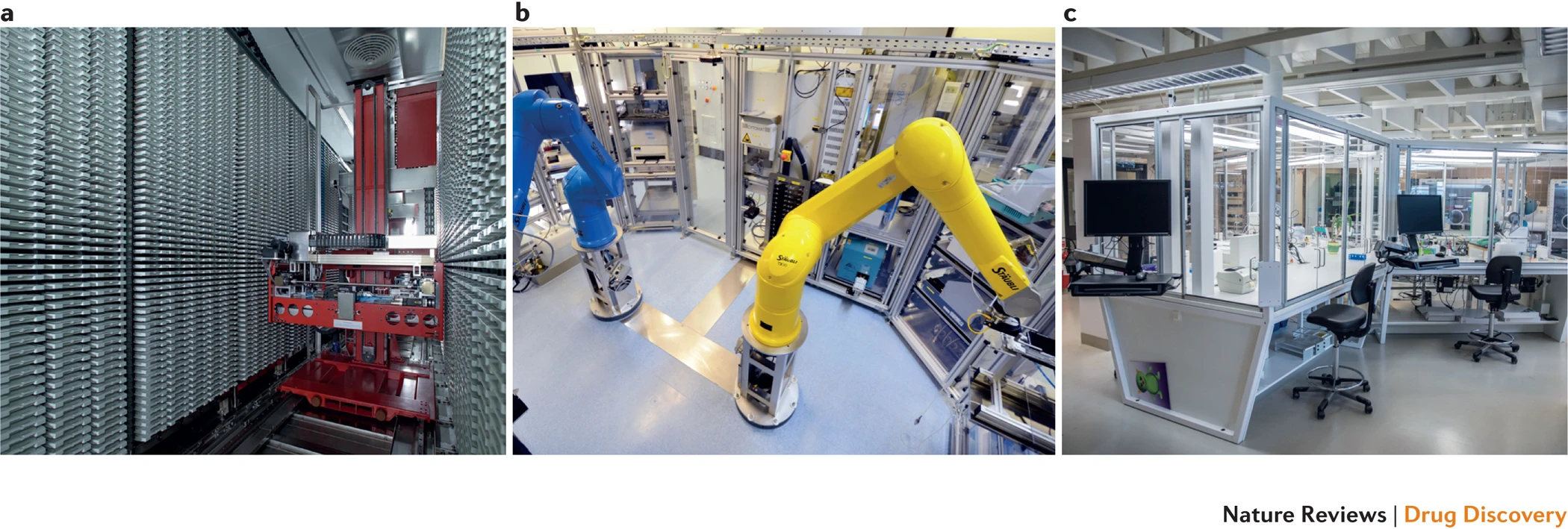

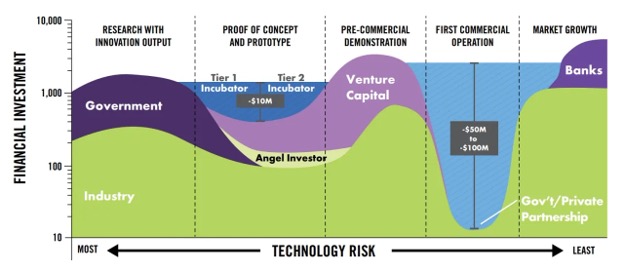

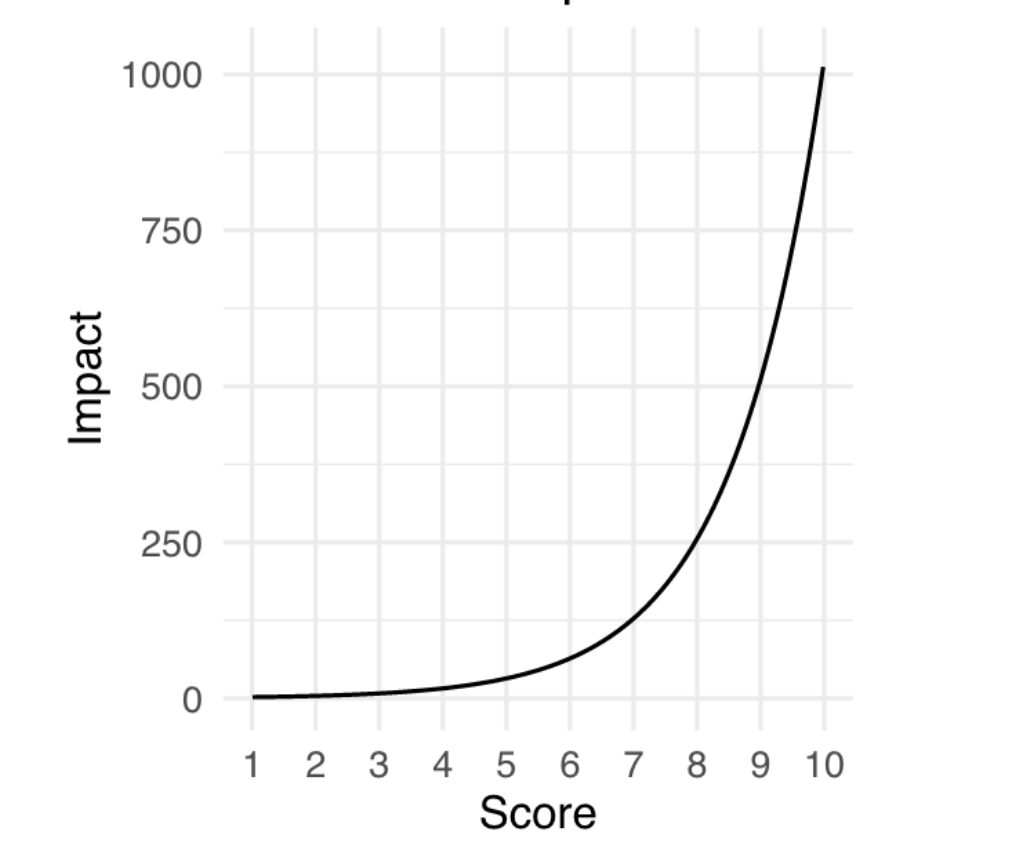

Figure 1. The “valley of death” describes the mismatch between existing financial structures and capital requirements in the crucial early commercialization phase. (Source: Maryland Energy Innovation Accelerator)

Shortcoming of Federal Subsidies

While the federal government has provided loans and subsidies in the past, its programs remain highly reactive and require large amounts of funding.

Aside from asking investors to take on greater risk and lower returns, there are several tools in place to ameliorate the valley of death. The IRA one such example: It appropriated some $370 billion for climate-related spending with a range of instruments, including tax subsidies for renewable energy production, low-cost loans through organizations such as the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office (LPO), and discretionary grants.

On the other hand, there are major issues with this approach. First, funding is spread out across many calls for funding that tend to be slow, opaque, and costly. Indeed, it is difficult to keep track of available resources, funding announcements, and key requirements—just try searching for a comprehensive, easy-to-understand list of opportunities.

More importantly, these funding mechanisms are simply expensive. The U.S. does not have the financial capacity to support an IRA or CHIPS Act for every industry, nor should it go down that route. While one could argue that these bills reflect the true cost of achieving the stated policy aims of energy transition or securing the semiconductor supply chain, it is also the case that there both knowledge (engineering expertise) and capital (manufacturing facility) capabilities underpin these technologies. Allowing these networks to atrophy created greater costs down the road, which could have been prevented by targeted investments at the right points of development.

The Future Is Dynamic

The future is not perfectly knowable, and new technological needs may arise that change priorities or solve previous problems. Therefore, agility and constant re-evaluation are essential.

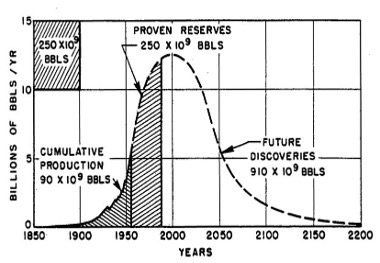

Technological progress is not static. Take the concept of peak oil: For decades, many of the world’s most intelligent geologists and energy forecasters believed that the world would quickly run out of oil reserves as the easiest to extract resources were extracted. In reality, technological advances in chemistry, surveying, and drilling enabled hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling, creating access to “unconventional reserves” that substantially increased fossil fuel supply.

Figure 2. In 1956, M.K. Hubbert created “peak oil” theory, projecting that reserves would be exhausted around the turn of the millennium.

Fracking greatly expanded fossil fuel production in the U.S., increasing resource supply, securing greater energy independence, and facilitating the transition from coal to natural gas, whose expansion has proved to be a helpful bridge towards renewable energy generation. This transition would not have been possible without a series of technological innovations—and highly motivated entrepreneurs—that arose to meet the challenge of energy costs.

To meet the challenges of tomorrow, policymakers need tools that provide them with flexible and targeted options as well as sufficient scale to make an impact on technologies that might need to get through the valley of death. However, they need to remain sufficiently agile so as not to distort well-functioning market forces. This balance is challenging to achieve and requires an organizational structure, authorizations, and funding mechanisms that are sufficiently nimble to adapt to changing technologies and markets.

Opportunity

Given these challenges, it seems unlikely that solutions that rely solely on the private sector will bridge the commercialization gap in a number of capital-intensive strategic industries. On the other hand, existing public-sector tools, such as grants and subsidies, are too costly to implement at scale for every possible externality and are generally too retrospective in nature rather than forward-looking. The government can be an impactful player in bridging the innovation gap, but it needs to do so cost-efficiently.

An SIF is a promising potential solution to the challenges posed above. By its nature, an SIF would have a public mission focused on strategic technologies crossing the valley of death by using targeted interventions and creative financing structures that crowd in private investors. This would enable the government to more sustainably fund innovation, maintain a light touch on private companies, and support key industries and technologies that will define the future global economic and security outlook.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Shepherd technologies through the valley of death.

While the SIF’s investment managers are expected to make the best possible returns, this is secondary to the overarching public policy goal of ensuring that strategically and economically vital technologies have an opportunity to get to commercial scale.

The SIF is meant to crowd in capital such that we achieve broader societal gains—and eventually, market-rate returns—enabled by technologies that would not have survived without timely and well-structured funding. This creates tension between two competing goals: The SIF needs to act as if it will intend to make returns, or else there is the potential for moral hazard and complacency. However, it also has to be willing to not make market-rate returns, or even lose some of its principal, in the service of broader market and ecosystem development.

Thus, it needs to be made explicitly clear from the beginning that an SIF has the intent of achieving market rate returns by catalyzing strategic industries but is not mandated to do so. One way to do this is to adopt a 501(c)(3) structure that has a loose affiliation to a department or agency, similar to that of In-Q-Tel. Excess returns could either be recycled to the fund or distributed to taxpayers.

The SIF should adapt the practices, structures, and procedures of established private-sector funds. It should have a standing investment committee made up of senior stakeholders across various agencies and departments (expanded upon below). Its day-to-day operations should be conducted by professionals who provide a range of experiences, including investing, engineering and technology, and public policy across a spectrum of issue areas.

In addition, the SIF should develop clear underwriting criteria and outputs for each investment. These include, but are not limited to, identifying the broader market and investment thesis, projecting product penetration, and developing potential return scenarios based on different permutations of outcomes. More critically, each investment needs to create a compelling case for why the private sector cannot fund commercialization on its own and why public catalytic funding is essential.

Recommendation 2. The SIF should have a permanent authorization to support innovation under the Department of Commerce.

The SIF should be affiliated with the Department of Commerce but work closely with other departments and agencies, including the Department of Energy, Department of Treasury, Department of Defense, Department of Health and Human Services, National Science Foundation, and National Economic Council.

Strategic technologies do not fall neatly into one sector and cut across many customers. Siloing funding in different departments misses the opportunity to capture funding synergies and, more importantly, develop priorities that are built through information sharing and consensus. Enter the Department of Commerce. In addition to administering the National Institute of Standards and Technology, they have a strong history of working across agencies, such as with the CHIPS Act.

Similar arguments can also be made for the Treasury, and it may even be possible to have Treasury and Commerce work together to manage an SIF. They would be responsible for bringing in subject matter experts (for example, from the Department of Energy or National Science Foundation) to provide specific inputs and arguments for why specific technologies need government-based commercialization funding and at what point such funding is appropriate, acting as an honest broker to allocate strategic capital.

To be clear: The SIF is not intended to supersede any existing funding programs (e.g., the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office or the National Institute of Health’s ARPA-H) that provide fit-for-purpose funding to specific sectors. Rather, an SIF is intended to fill in the gaps and coordinate with existing programs while providing more creative financing structures than are typically available from government programs.

Recommendation 3. Create a clear innovation roadmap.

Every two years, the SIF should develop or update a roadmap of strategically important industries, working closely with private, nonprofit, and academic experts to define key technological and capability gaps that merit public sector investment.

The SIF’s leaders should be empowered to make decisions on areas to prioritize but have the ability to change and adapt as the economic environment evolves. Although there is a long list of industries that an SIF could potentially support, resources are not infinite. However, a critical mass of investment is required to ensure adequate resourcing. One acute challenge is that this is not perfectly known in advance and changes depending on the technology and sector. However, this is precisely what the strategic investment roadmap is supposed to solve for: It should provide an even-handed assessment of the likely capital requirements and where the SIF is best suited to provide funding compared to other agencies or the private sector.

Moreover, given the ever-changing nature of technology, the SIF should frequently reassess its understanding of key use cases and their broader economic and strategic importance. Thus, after initial development of the SIF, it should be updated every two years to ensure that its takeaways and priorities remain relevant. This is no different than documents such as the National Security Strategy, which are updated every two to four years; in fact, the SIF’s planning documents should flow seamlessly into the National Security Strategy.

To provide a sufficiently broad set of perspectives, the government should include the expertise and insights of outside experts to develop its plan. Existing bodies, such as the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology and the National Quantum Initiative, provide some of the consultative expertise required. However, the SIF should also stand up subject matter specific advisory bodies where a need arises (for example, on critical minerals and mining) and work internally to set specific investment areas and priorities.

Recommendation 4. Limit the SIF to financing.

The government should not be an outsized player in capital markets. As such, the SIF should receive no governance rights (e.g., voting or board seats) in the companies that it invests in.

Although the SIF aims to catalyze technological and ecosystem development, it should be careful not to dictate the future of specific companies. Thus, the SIF should avoid information rights beyond financial reporting. Typical board decks and stockholder updates include updates on customers, technologies, personnel matters, and other highly confidential and specific pieces of information that, if made public through government channels, would play a highly distortionary role in markets. Given that the SIF is primarily focused on supporting innovation through a particularly tricky stage to navigate, the SIF should receive the least amount of information possible to avoid disrupting markets.

Recommendation 5. Focus on providing first-loss capital.

First-loss capital should be the primary mechanism by which the SIF supports new technologies, providing greater incentives for private-sector funders to support early commercialization while providing a means for taxpayers to directly participate in the economic upside of SIF-supported technologies.

Consider the following stylized example to demonstrate a key issue in the valley of death. A promising clean technology company, such as a carbon-free cement or long-duration energy storage firm, is raising $100mm of capital for facility expansion and first commercial deployment. To date, the company has likely raised $30 – $50mm of venture capital to enable tech development, pilot the product, and grow the team’s engineering, R&D, and sales departments.

However, this company faces a fundraising dilemma. Its funding requirements are now too big for all but the largest venture capital firms, who may or may not want to invest in projects and companies like these. On the other hand, this hypothetical company is not mature enough for private equity buyouts nor is it a good candidate for typical project-based debt, which typically require several commercial proof points in order to provide sufficient risk reduction for an investor whose upside is relatively limited. Hence, the “valley of death.”

First-loss capital is an elegant solution to this issue: A prospective funder could commit to equal (pro rata) terms as other investors, except that this first-loss funder is willing to use its investment to make other investors whole (or at least partially offset losses) in the event that the project or company does not succeed. In this example, a first-loss funder would commit to $33.5 million of equity funding (roughly one-third of the company’s capital requirement). If the company succeeds, the first-loss funder makes the same returns as the other investors. However, if the company is unable to fully meet these obligations, the first-loss funder’s $33.5 million would be used to pay the other investors back (the other $66.5 million that was committed). This creates a floor on losses for the non-first-loss investors: Rather than being at risk of losing 100% of their principal, they are at risk of losing 50% of their principal.

The creation of a first-loss layer has a meaningful impact on the risk-reward profile for non-first-loss investors, who now have a floor on returns (in the case above, half their investment). By expanding the acceptable potential loss ratio, growth equity capital (or another appropriate instrument, such as project finance) can fill the rest, thereby crowding in capital.

From a risk-adjusted returns standpoint, this is not a free lunch for the government or taxpayers. Rather, it is intended to be a capital-efficient way of supporting the private-sector ecosystem in developing strategically and economically vital technologies. In other words, it leverages the power of the private sector to solve externalities while providing just enough support to get them to the starting line in the first place.

Conclusion

Many of tomorrow’s strategically important technologies face critical funding challenges in the valley of death. Due to their capital intensity and uncertain outcomes, existing financing tools are largely falling short in the critical early commercialization phases. However, a nimble, properly funded SIF could bridge key gaps while allowing the private sector to do most of the heavy lifting. The SIF would require buy-in from many stakeholders and well-defined sources of funding, but these can be solved with the right mandates, structures, and pay-fors. Indeed, the stakes are too high, and the consequences too dire, to not get strategic innovation right in the 21st century.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Put simply, there needs to be an entity that is actually willing and able to absorb lower returns, or even lose some of its principal, in the service of building an ecosystem. Even if the “median” outcome is a market-rate return of capital, the risk-adjusted returns are in effect far lower because the probability of a zero outcome for first-loss providers is substantially nonzero. Moreover, it’s not clear exactly what the right probability estimate should be; therefore, it requires a leap of faith that no economically self-interested private market actor would be willing to take. While some quasi-social-sector organizations can play this role (for example, Bill Gates’s Breakthrough Energy Ventures for climate tech), their capacity is finite, nor is there a guarantee that such a vehicle will appear for every sector of interest. Therefore, a publicly funded SIF is an integral solution to bridging the valley of death.

No, the SIF would not always have to use first-loss structures. However, it is the most differentiated structure that is available to the U.S. government; otherwise, a private-sector player is likely able—and better positioned—to provide funding.

The SIF should be able to use the full range of instruments, including project finance, corporate debt, convertible loans, and equity capital, and all combinations thereof. The instrument of choice should be up to the judgment of the applicant and SIF investment team. This is distinct from providing first-loss capital: Regardless of the financial instrument used, the SIF’s investment would be used to buffer other investors against potential losses.

The target return rate should be commensurate with that of the instrument used. For example, mezzanine debt should target 13–18% IRR, while equity investments should aim for 20–25% IRR. However, because of the increased risk of capital loss to the SIF given its first loss position, the effective blended return should be expected to be lower.

The SIF should be prepared to lose capital on each individual investment and, as a blended portfolio, to have negative returns. While it should underwrite such that it will achieve market-rate returns if successful in crowding in other capital that improves the commercial prospects of technologies and companies in the valley of death, the SIF has a public goal of ecosystem development for strategic domains. Therefore, lower-than-market-rate returns, and even some principal degradation, is acceptable but should be avoided as much as possible through the prudence of the investment committee.

By and large, the necessary public protections are granted through CFIUS, which requires regulatory approval for export or foreign ownership stakes with voting rights above 25% of critical technologies. The SIF can also enact controls around information rights (e.g., customer lists, revenue, product roadmaps) such that they have a veto on parties that can receive such information. However, given its catalytic mission, the SIF does not need board seats or representation and should focus on ensuring that critical technologies and assets are properly protected.

In most private investment firms, the investment committee is made up of the most senior individuals in the fund. These individuals can cross asset classes, sectors of expertise, and even functional backgrounds. However, the investment committee represents a wide breadth of expertise and experiences that, when brought together, enable intellectual honesty and the application of collective wisdom and judgment to the opportunity at hand.

Similarly, the SIF’s investment committee could include the head of the fund and representatives from various departments and agencies in alignment with its strategic priorities. The exact size of the investment committee should be defined by these priorities, but approval should be driven by consensus, and unanimity (or near unanimity) should be expected for investments that are approved.

Given the fluid nature of investment opportunities, the committee should be called upon whenever needed to evaluate a potential opportunity. However, given the generally long process times for investments discussed above (6–12 months), the investment committee should have been briefed multiple times before a formal decision is made.

Check sizes can be flexible to the needs of the investment opportunity. However, as an initial guiding principle, first loss capital should likely make up 20–35% of capital invested so as to require private-sector investors to have meaningful skin in the game. Depending on the fundraise size, this could imply investments of $25 million to $100 million.

Target funding amounts should be set over multiyear timeframes, but the annual appropriations process implies that there will likely be a set cap in any given year. In order to meet the needs of the market, there should be mechanisms that enable emergency draws, up to a cap (e.g., 10% of the annual target funding amount, which will need to be “paid for” by reducing future outlays).

An economically efficient way to fund a government program in support of a positive externality is a Pigouvian tax on negative externalities (such as carbon). However, carbon taxes are as politically unappealing as they are economically sensible and need to be packaged into other policy goals that could potentially support such legislation. Notwithstanding the questionable economic wisdom of tariffs in general, some 56% of voters support a 10% tax on all imports and 60% tariffs on China. Rather than using tariffs harmfully, they could be used more productively. One such proposal is a carbon import tariff that taxes imports on the carbon emitted in the production and transportation of goods into the U.S.

The U.S. would not be a first mover: in fact, the European Union has already implemented a similar mechanism called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which is focused on heavy industry, including cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity, and hydrogen, with chemicals and polymers potentially to be included after 2026. At full rollout in 2030, the CBAM is expected to generate roughly €10–15 billion of tax revenue. Tax receipts of a similar size could be used to fund an SIF or, if Congress authorizes an upfront amount, could be used to nullify the incremental deficit over time.

The EU’s CBAM phased in its reporting requirements over several years. Through July 2024, companies were allowed to use default amounts per unit of production without an explanation as to why actual data was not used. Until January 1, 2026, companies can make estimates for up to 20% of goods; thereafter, the CBAM requires reporting of actual quantities and embedded greenhouse gas emissions.

The U.S. could use a similar phase-in, although given the challenges of carbon reporting, could allow companies to use the lower of actual, verified emissions or per-unit estimates. Under a carbon innovation fee regime, exporters and countries could apply for exemption on a case-by-case basis to the Department of Commerce, which they could approve in line with other goals (e.g., economic development in a region).

The SIF could also be funded by repurposing other funding and elevating their strategic importance. Potential candidates include the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small State Business Credit Initiative (SSBCI), which could play a bigger role if moved into the SIF umbrella. For example, the SBIR program, whose latest reporting data is as of FY2019, awarded $3.3 billion in funding that year and $54.6 billion over its lifespan. Moreover, the SSBCI, a $10 billion fund that already provides loan guarantees and other instruments similar to those described above, can be used to support technologies that fall into the purview of the SIF.

Congress could also assess reallocating dollars towards an SIF from spending reforms that are likely inevitable given the country’s fiscal position. In 2023, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a report highlighting potential solutions for reducing the budget deficit. Some potential solutions, like establishing caps on Medicaid federal spending, while fiscally promising, seem unlikely to pass in the near future. However, others are more palatable, especially those that eliminate loopholes or ask higher-income individuals to pay their fair share.

For instance, increasing the amount subject to Social Security taxes above the $250,000 threshold has the potential to raise up to $1.2 trillion over 10 years; while this can be calibrated, an SIF would take only a small fraction of the taxes raised. In addition, the CBO found that federal matching funds for Medicaid frequently ended up getting back to healthcare providers in the form of higher reimbursement rates; eliminating what are effectively kickbacks could reduce the deficit by up to $525 billion over 10 years.

Promoting Fairness in Medical Innovation

There is a crisis within healthcare technology research and development, wherein certain groups due to their age, gender, or race and ethnicity are under-researched in preclinical studies, under-represented in clinical trials, misunderstood by clinical practitioners, and harmed by biased medical technology. These issues in turn contribute to costly disparities in healthcare outcomes, leading to losses of $93 billion a year in excess medical-care costs, $42 billion a year in lost productivity, and $175 billion a year due to premature deaths. With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) in healthcare, there’s a risk of encoding and recreating existing biases at scale.

The next Administration and Congress must act to address bias in medical technology at the development, testing and regulation, and market-deployment and evaluation phases. This will require coordinated effort across multiple agencies. In the development phase, science funding agencies should enforce mandatory subgroup analysis for diverse populations, expand funding for under-resourced research areas, and deploy targeted market-shaping mechanisms to incentivize fair technology. In the testing and regulation phase, the FDA should raise the threshold for evaluation of medical technologies and algorithms and expand data-auditing processes. In the market-deployment and evaluation phases, infrastructure should be developed to perform impact assessments of deployed technologies and government procurement should incentivize technologies that improve health outcomes.

Challenge and Opportunity

Bias is regrettably endemic in medical innovation. Drugs are incorrectly dosed to people assigned female at birth due to historical exclusion of women from clinical trials. Medical algorithms make healthcare decisions based on biased health data, clinically disputed race-based corrections, and/or model choices that exacerbate healthcare disparities. Much medical equipment is not accessible, thus violating the Americans with Disabilities Act. And drugs, devices, and algorithms are not designed with the lifespan in mind, impacting both children and the elderly. Biased studies, technology, and equipment inevitably produce disparate outcomes in U.S. healthcare.

The problem of bias in medical innovation manifests in multiple ways: cutting across technological sectors in clinical trials, pervading the commercialization pipeline, and impeding equitable access to critical healthcare advances.

Bias in medical innovation starts with clinical research and trials

The 1993 National Institutes of Health (NIH) Revitalization Act required federally funded clinical studies to (i) include women and racial minorities as participants, and (ii) break down results by sex and race or ethnicity. As of 2019, the NIH also requires inclusion of participants across the lifespan, including children and older adults. Yet a 2019 study found that only 13.4% of NIH-funded trials performed the mandatory subgroup analysis, and challenges in meeting diversity targets continue into 2024 . Moreover, the increasing share of industry-funded studies are not subject to Revitalization Act mandates for subgroup analysis. These studies frequently fail to report differences in outcomes by patient population as a result. New requirements for Diversity Action Plans (DAPs), mandated under the 2023 Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act, will ensure drug and device sponsors think about enrollment of diverse populations in clinical trials. Yet, the FDA can still approve drugs and devices that are not in compliance with their proposed DAPs, raising questions around weak enforcement.

The resulting disparities in clinical-trial representation are stark: African Americans represent 12% of the U.S. population but only 5% of clinical-trial participants, Hispanics make up 16% of the population but only 1% of clinical trial participants, and sex distribution in some trials is 67% male. Finally, many medical technologies approved prior to 1993 have not been reassessed for potential bias. One outcome of such inequitable representation is evident in drug dosing protocols: sex-aware prescribing guidelines exist for only a third of all drugs.

Bias in medical innovation is further perpetuated by weak regulation

Algorithms

Regulation of medical algorithms varies based on end application, as defined in the 21st Century Cures Act. Only algorithms that (i) acquire and analyze medical data and (ii) could have adverse outcomes are subject to FDA regulation. Thus, clinical decision-support software (CDS) is not regulated even though these technologies make important clinical decisions in 90% of U.S. hospitals. The FDA has taken steps to try and clarify what CDS must be considered a medical device, although these actions have been heavily criticized by industry. Finally, the lack of regulatory frameworks for generative AI tools is leading to proliferation without oversight.

Even when a medical algorithm is regulated, regulation may occur through relatively permissive de novo pathways and 510(k) pathways. A de novo pathway is used for novel devices determined to be low to moderate risk, and thus subject to a lower burden of proof with respect to safety and equity. A 510(k) pathway can be used to approve a medical device exhibiting “substantial equivalence” to a previously approved device, i.e., it has the same intended use and/or same technological features. Different technical features can be approved so long as there are no questions raised around safety and effectiveness.

Medical algorithms approved through de novo pathways can be used as predicates for approval of devices through 510(k) pathways. Moreover, a device approved through a 510(k) pathway can remain on the market even if its predicate device was recalled. Widespread use of 510(k) approval pathways has generated a “collapsing building” phenomenon, wherein many technologies currently in use are based on failed predecessors. Indeed, 97% of devices recalled between 2008 to 2017 were approved via 510(k) clearance.

While DAP implementation will likely improve these numbers, for the 692 AI-ML enabled medical devices, only 3.6% reported race or ethnicity, 18.4% reported age, and only .9% include any socioeconomic information. Further, less than half did detailed analysis of algorithmic performance and only 9% included information on post-market studies, raising the risk of algorithmic bias following approvals and broad commercialization.

Even more alarming is evidence showing that machine learning can further entrench medical inequities. Because machine learning medical algorithms are powered by data from past medical decision-making, which is rife with human error, these algorithms can perpetuate racial, gender, and economic bias. Even algorithms demonstrated to be ‘unbiased’ at the time of approval can evolve in biased ways over time, with little to no oversight from the FDA. As technological innovation progresses, especially generative AI tools, an intentional focus on this problem will be required.

Medical devices

Currently, the Medical Device User Fee Act requires the FDA to consider the least burdensome appropriate means for manufacturers to demonstrate the effectiveness of a medical device or to demonstrate a device’s substantial equivalence. This requirement was reinforced by the 21st Century Cures Act, which also designated a category for “breakthrough devices” subject to far less-stringent data requirements. Such legislation shifts the burden of clinical data collection to physicians and researchers, who might discover bias years after FDA approval. This legislation also makes it difficult to require assessments on the differential impacts of technology.

Like medical algorithms, many medical devices are approved through 510(k) exemptions or de novo pathways. The FDA has taken steps since 2018 to increase requirements for 510(k) approval and ensure that Class III (high-risk) medical devices are subject to rigorous pre-market approval, but problems posed by equivalence and limited diversity requirements remain.

Finally, while DAPs will be required for many devices seeking FDA approval, the recommended number of patients in device testing is shockingly low. For example, currently, only 10 people are required in a study of any new pulse oximeter’s efficacy and only 2 of those people need to be “darkly pigmented”. This requirement (i) does not have the statistical power necessary to detect differences between demographic groups, and (i) does not represent the composition of the U.S. population. The standard is currently under revision after immense external pressure. FDA-wide, there are no recommended guidelines for addressing human differences in device design, such as pigmentation, body size, age, and pre-existing conditions.

Pharmaceuticals

The 1993 Revitalization Act strictly governs clinical trials for pharmaceuticals and does not make recommendations for adequate sex or genetic diversity in preclinical research. The results are that a disproportionately high number of male animals are used in research and that only 5% of cell lines used for pharmaceutical research are of African descent. Programs like All of Us, an effort to build diverse health databases through data collection, are promising steps towards improving equity and representation in pharmaceutical research and development (R&D). But stronger enforcement is needed to ensure that preclinical data (which informs function in clinical trials) reflects the diversity of our nation.

Bias in medical innovation are not tracked post-regulatory approval

FDA-regulated medical technologies appear trustworthy to clinicians, where the approval signals safety and effectiveness. So, when errors or biases occur (if they are even noticed), the practitioner may blame the patient for their lifestyle rather than the technology used for assessment. This in turn leads to worse clinical outcomes as a result of the care received.

Bias in pulse oximetry is the perfect case study of a well-trusted technology leading to significant patient harm. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many clinicians and patients were using oximeter technology for the first time and were not trained to spot factors, like melanin in the skin, that cause inaccurate measurements and impact patient care. Issues were largely not attributed to the device. This then leads to underreporting of adverse events to the FDA — which is already a problem due to the voluntary nature of adverse-event reporting.

Even when problems are ultimately identified, the federal government is slow to respond. The pulse oximeter’s limitations in monitoring oxygenation levels across diverse skin tones was identified as early as the 1990s. 34 years later, despite repeated follow-up studies indicating biases, no manufacturer has incorporated skin-tone-adjusted calibration algorithms into pulse oximeters. It required the large Sjoding study, and the media coverage it garnered around delayed care and unnecessary deaths, for the FDA to issue a safety communication and begin reviewing the regulation.

Other areas of HHS are stepping up to address issues of bias in deployed technologies. A new ruling by the HHS Office of Civil Rights (OCR) on Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act requires covered providers and institutions (i.e. any receiving federal funding) to identify their use of patient care decision support tools that directly measure race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability, and to make reasonable efforts to mitigate the risk of discrimination from their use of these tools. Implementation of this rule will depend on OCR’s enforcement, and yet it provides another route to address bias in algorithmic tools.

Differential access to medical innovation is a form of bias

Americans face wildly different levels of access to new medical innovations. As many new innovations have high cost points, these drugs, devices, and algorithms exist outside the price range of many patients, smaller healthcare institutions and federally funded healthcare service providers, including the Veterans Health Administration, federally qualified health centers and the Indian Health Service. Emerging care-delivery strategies might not be covered by Medicare and Medicaid, meaning that patients insured by CMS cannot access the most cutting-edge treatments. Finally, the shift to digital health, spurred by COVID-19, has compromised access to healthcare in rural communities without reliable broadband access.

Finally, the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H) has a commitment to have all programs and projects consider equity in their design. To fulfill ARPA-H’s commitment, there is a need for action to ensure that medical technologies are developed fairly, tested with rigor, deployed safely, and made affordable and accessible to everyone.

Plan of Action

The next Administration should launch “Healthcare Innovation for All Americans” (HIAA), a whole of government initiative to improve health outcomes by ensuring Americans have access to bias-free medical technologies. Through a comprehensive approach that addresses bias in all medical technology sectors, at all stages of the commercialization pipeline, and in all geographies, the initiative will strive to ensure the medical-innovation ecosystem works for all. HIAA should be a joint mandate of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Office of Science Technology and Policy (OSTP) to work with federal agencies on priorities of equity, non-discrimination per Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act and increasing access to medical innovation, and initiative leadership should sit at both HHS and OSTP.

This initiative will require involvement of multiple federal agencies, as summarized in the table below. Additional detail is provided in the subsequent sections describing how the federal government can mitigate bias in the development phase; testing, regulation, and approval phases; and market deployment and evaluation phases.

Three guiding principles should underlie the initiative:

- Equity and non-discrimination should drive action. Actions should seek to improve the health of those who have been historically excluded from medical research and development. We should design standards that repair past exclusion and prevent future exclusion.

- Coordination and cooperation are necessary. The executive and legislative branches must collaborate to address the full scope of the problem of bias in medical technology, from federal processes to new regulations. Legislative leadership should task the Government Accountability Office (GAO) to engage in ongoing assessment of progress towards the goal of achieving bias-free and fair medical innovation.

- Transparent, evidence-based decision making is paramount. There is abundant peer-reviewed literature that examines bias in drugs, devices, and algorithms used in healthcare settings — this literature should form the basis of a non-discrimination approach to medical innovation. Gaps in evidence should be focused on through deployed research funding. Moreover, as algorithms become ubiquitous in medicine, every effort should be made to ensure that these algorithms are trained on representative data of those experiencing a given healthcare condition.

Addressing bias at the development phase

The following actions should be taken to address bias in medical technology at the innovation phase:

- Enforce parity in government-funded research. For clinical research, NIH should examine the widespread lack of adherence to regulations requiring that government funded clinical trials report sex, racial or ethnicity, and age breakdown of trial participants. Funding should be reevaluated for non-compliant trials. For preclinical research, NIH should require gender parity in animal models and representation of diverse cell lines used in federally funded studies.

- Deploy funding to address research gaps. Where data sources for historically marginalized people are lacking, such as for women’s cardiovascular health, NIH should deploy strategic, targeted funding programs to fill these knowledge gaps. This could build on efforts like the Initiative on Women’s Health Research. Increased funding should include resources for underrepresented groups to participate in research and clinical trials through building capacity in community organizations. Results should be added to a publicly available database so they can be accessed by designers of new technologies. Funding programs should also be created to fill gaps in technology, such as in diagnostics and treatments for high-prevalence and high-burden uterine diseases like endometriosis (found in 10% of reproductive-aged people with uteruses).

- Invest in research into healthcare algorithms and databases. Given the explosion of algorithms in healthcare decision-making, NIH and NSF should launch a new research program focused on the study, evaluation, and application of algorithms in healthcare delivery, and on how artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) can exacerbate healthcare inequities. The initial request for proposals should focus on design strategies for medical algorithms that mitigate bias from data or model choices.

- Task ARPA-H with developing metrics for equitable medical technology development. ARPA-H should prioritize developing a set of procedures and metrics for equitable development of medical technology. Once developed, these processes should be rapidly deployed across ARPA-H, as well as published for potential adoption by additional federal agencies, industry, and other stakeholders. ARPA-H could also collaborate with NIST on standards setting with NIST and ASTP on relevant standards setting. For instance, NIST has developed an AI Risk Management Framework and the ONC engages in setting standards that achieve equity by design. CMS could use resultant standards for Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements.

- Leverage procurement as a demand-signal for medical technologies that work for diverse populations. As the nation’s largest healthcare system, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) can generate demand-signals for bias-free medical technologies through its procurement processes and market-shaping mechanisms. For example, the VA could put out a call for a pulse oximeter that works equally well across the entire range of human skin pigmentation and offer contracts for the winning technology.

Addressing bias at the testing, regulation, and approval phases

The following actions should be taken to address bias in medical innovation at the testing, regulation, and approval phases:

- Raise the threshold for FDA evaluation of devices and algorithms. Equivalency necessary to receive 510(k) clearance should be narrowed. For algorithms, this would involve consideration of whether the datasets for machine learning tactics used by the new device and its predicate are similar. For devices (including those that use algorithms), this would require tightening the definition of “same intended use” (currently defined as a technology having the same functionality as one previously approved by the FDA) as well as eliminating the approval of new devices with “different technological characteristics” (the application of one technology to a new area of treatment in which that technology is untested).

- Evaluate FDA’s guidance on specific technology groups for equity. Requirements for the safety of a given drug, medical device, or algorithm should have the statistical power necessary to detect differences between demographic groups and represent all end-users of the technology..

- Establish a data bank for auditing medical algorithms. The newly established Office of Digital Transformation within the FDA should create a “data bank” of healthcare images and datasets representative of the U.S. population, which could be done in partnership with the All of Us program. Medical technology developers could use the data bank to assess the performance of medical algorithms across patient populations. Regulators could use the data bank to ground claims made by those submitting a technology for FDA approval.

- Allow data submitted to the FDA to be examined by the broader scientific community. Currently, data submitted to the FDA as part of its regulatory-approval process is kept as a trade secret and not released pre-authorization to researchers. Releasing the data via an FDA-invited “peer review” step in the regulation of high-risk technologies, like automated decision-making algorithms, Class III medical devices, and drugs, will ensure that additional, external rigor is applied to the technologies that could cause the most harm due to potential biases.

- Establish an enforceable AI Bill of Rights. The federal government and Congress should create protections for necessary uses of artificial intelligence (AI) identified by OSTP. Federally funded healthcare centers, like facilities part of the Veterans Health Administration, could refuse to buy software or technology products that violate this “AI Bill of Rights” through changes to federal acquisition regulation (FAR).

Addressing bias at the market deployment and evaluation phases

- Strengthen reporting mechanisms at the FDA. Healthcare providers, who are often closest to the deployment of medical technologies, should be made mandatory reporters to the FDA of all witnessed adverse events related to bias in medical technology. In addition, the FDA should require the inclusion of unique device identifiers (UDIs) in adverse-response reporting. Using this data, Congress should create a national and publicly accessible registry that uses UDIs to track post-market medical outcomes and safety.

- Require impact assessments of deployed technologies. Congress must establish systems of accountability for medical technologies, like algorithms, that can evolve over time. Such work could be done by passing the Algorithmic Accountability Act which would require companies that create “high-risk automated decision systems” to conduct impact assessments reviewed by the FTC as frequently as necessary.

- Assess disparities in patient outcomes to direct technical auditing. AHRQ should be given the funding needed to fully investigate patient-outcome disparities that could be caused by biases in medical technology, such as its investigation into the impacts of healthcare algorithms on racial and ethnic disparities. The results of this research should be used to identify technologies that the FDA should audit post-market for efficacy or the FTC should investigate. CMS and its accrediting agencies can monitor these technologies and assess whether they should receive Medicare and Medicaid funding.

- Review reimbursement guidelines that are dependent on medical technologies with known bias. CMS should review its national coverage determinations for technologies, like pulse oximetry, that are known to perform differently across populations. For example, pulse oximeters can be used to determine home oxygen therapy provision, thus potentially excluding darkly-pigmented populations from receiving this benefit.

- Train physicians to identify bias in medical technologies and identify new areas of specialization. ED should work with medical schools to develop curricula training physicians to identify potential sources of bias in medical technologies and ensuring that physicians understand how to report adverse events to the FDA. In addition, ED should consider working with the American Medical Association to create new medical specialties that work at the intersection of technology and care delivery.

- Ensure that technologies developed by ARPA-H have an enforceable access plan. ARPA-H will produce cutting-edge technologies that must be made accessible to all Americans. ARPA-H should collaborate with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to develop strategies for equitable delivery of these new technologies. A cost-effective deployment strategy must be identified to service federally-funded healthcare institutions like Veterans Health Administration hospitals and clinical, federally qualified health centers, and Indian Health Service.

- Create a fund to support digital health technology infrastructure in rural hospitals. To capitalize on the $65 billion expansion of broadband access allocated in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, HRSA should deploy strategic funding to federally qualified health centers and rural health clinics to support digital health strategies — such as telehealth and mobile health monitoring — and patient education for technology adoption.

A comprehensive road map is needed

The GAO should conduct a comprehensive investigation of “black box” medical technologies utilizing algorithms that are not transparent to end users, medical providers, and patients. The investigation should inform a national strategic plan for equity and non-discrimination in medical innovation that relies heavily on algorithmic decision-making. The plan should include identification of noteworthy medical technologies leading to differential healthcare outcomes, creation of enforceable regulatory standards, development of new sources of research funding to address knowledge gaps, development of enforcement mechanisms for bias reporting, and ongoing assessment of equity goals.

Timeline for action

Realizing HIAA will require mobilization of federal funding, introduction of regulation and legislation, and coordination of stakeholders from federal agencies, industry, healthcare providers, and researchers around a common goal of mitigating bias in medical technology. Such an initiative will be a multi-year undertaking and require funding to enact R&D expenditures, expand data capacity, assess enforcement impacts, create educational materials, and deploy personnel to staff all the above.

Near-term steps that can be taken to launch HIAA include issuing a public request for information, gathering stakeholders, engaging the public and relevant communities in conversation, and preparing a report outlining the roadmap to accomplishing the policies outlined in this memo.

Conclusion

Medical innovation is central to the delivery of high-quality healthcare in the United States. Ensuring equitable healthcare for all Americans requires ensuring that medical innovation is equitable across all sectors, phases, and geographies. Through a bold and comprehensive initiative, the next Administration can ensure that our nation continues leading the world in medical innovation while crafting a future where healthcare delivery works for all.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

HIAA will be successful when medical policies, projects, and technologies yield equitable health care access, treatment, and outcomes. For instance, success would yield the following outcomes:

- Representation in preclinical and clinical research equivalent to the incidence of a studied condition in the general population.

- Research on a disease condition funded equally per affected patient.

- Existence of data for all populations facing a given disease condition.

- Medical algorithms that have equal efficacy across subgroup populations.

- Technologies that work equally well in testing as they do when deployed to the market.

- Healthcare technologies made available and affordable to all care facilities.

Regulation alone cannot close the disparity gap. There are notable gaps in preclinical and clinical research data for women, people of color, and other historically underrepresented groups that need to be filled. There are also historical biases encoded in AI/ML decision making algorithms that need to be studied and rectified. In addition, the FDA’s role is to serve as a safety check on new technologies — the agency has limited oversight over technologies once they are out on the market due to the voluntary nature of adverse reporting mechanisms. This means that agencies like the FTC and CMS need to be mobilized to audit high-risk technologies once they reach the market. Eliminating bias in medical technology is only possible through coordination and cooperation of federal agencies with each other as well as with partners in the medical device industry, the pharmaceutical industry, academic research, and medical care delivery.

A significant focus of the medical device and pharmaceutical industries is reducing the time to market for new medical devices and drugs. Imposing additional requirements for subgroup analysis and equitable use as part of the approval process could work against this objective. On the other hand, ensuring equitable use during the development and approval stages of commercialization will ultimately be less costly than dealing with a future recall or a loss of Medicare or Medicaid eligibility if discriminatory outcomes are discovered.

Healthcare disparities exist in every state in America and are costing billions a year in economic growth. Some of the most vulnerable people live in rural areas, where they are less likely to receive high-quality care because costs of new medical technologies are too high for the federally qualified health centers that serve one in five rural residents as well as rural hospitals. Furthermore, during continued use, a biased device creates adverse healthcare outcomes that cost taxpayers money. A technology functioning poorly due to bias can be expensive to replace. It is economically imperative to ensure technology works as expected, as it leads to more effective healthcare and thus healthier people.

Scaling Effective Methods across Federal Agencies: Looking Back at the Expanded Use of Incentive Prizes between 2010-2020

Policy entrepreneurs inside and outside of government, as well as other stakeholders and advocates, are often interested in expanding the use of effective methods across many or all federal agencies, because how the government accomplishes its mission is integral to what the government is able to produce in terms of outcomes for the public it serves. Adoption and use of promising new methods by federal agencies can be slowed by a number of factors that discourage risk-taking and experimentation, and instead encourage compliance and standardization, too often as a false proxy for accountability. As a result, many agency-specific and government-wide authorities for promising methods go under-considered and under-utilized.