2025 Heat Policy Agenda

It’s official: 2024 was the hottest year on record. But Americans don’t need official statements to tell them what they already know: our country is heating up, and we’re deeply unprepared.

Extreme heat has become a national economic crisis: lowering productivity, shrinking business revenue, destroying crops, and pushing power grids to the brink. The impacts of extreme heat cost our Nation an estimated $162 billion in 2024 – equivalent to nearly 1% of the U.S. GDP.

Extreme heat is also taking a human toll. Heat kills more Americans every year than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined. The number of heat-related illnesses is even higher. And even when heat doesn’t kill, it severely compromises quality of life. This past summer saw days when more than 100 million Americans were under a heat advisory. That means that there were days when it was too hot for a third of our country to safely work or play.

We have to do better. And we can.

Attached is a comprehensive 2025 Heat Policy Agenda for the Trump Administration and 119th Congress to better prepare for, manage, and respond to extreme heat. The Agenda represents insights from hundreds of experts and community leaders. If implemented, it will build readiness for the 2025 heat season – while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation.

Core recommendations in the Agenda include the following:

- Establish a clear, sustained federal governance structure for extreme heat. This will involve elevating, empowering, and dedicating funds to the National Interagency Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), establishing a National Heat Executive Council, and designating a National Heat Coordinator in the White House.

- Amend the Stafford Act to explicitly define extreme heat as a “major disaster”, and expand the definition of damages to include non-infrastructure impacts.

- Direct the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to consider declaring a Public Health Emergency in the event of exceptional, life-threatening heat waves, and fully fund critical HHS emergency-response programs and resilient healthcare infrastructure.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to include extreme heat as a core component of national preparedness capabilities and provide guidance on how extreme heat events or compounding hazards could qualify as major disasters.

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace, and establish Centers of Excellence to protect troops, transportation workers, farmworkers, and other essential personnel from extreme heat.

- Retain and expand home energy rebates, tax credits, LIHEAP, and the Weatherization Assistance Program, to enable deep retrofits that cut the costs of cooling for all Americans and prepare homes and other infrastructure against threats like power outages.

- Transform the built and landscaped environment through strategic investments in urban forestry and green infrastructure to cool communities, transportation systems to secure safe movement of people and goods, and power infrastructure to ready for greater load demand.

The way to prevent deaths and losses from extreme heat is to act before heat hits. Our 60+ organizations, representing labor, industry, health, housing, environmental, academic and community associations and organizations, urge President Trump and Congressional leaders to work quickly and decisively throughout the new Administration and 119th Congress to combat the growing heat threat. America is counting on you.

Executive Branch

Federal agencies can do a great deal to combat extreme heat under existing budgets and authorities. By quickly integrating the actions below into an Executive Order or similar directive, the President could meaningfully improve preparedness for the 2025 heat season while laying the foundation for a more heat-resilient nation in the long term.

Streamline and improve extreme heat management.

More than thirty federal agencies and offices share responsibility for acting on extreme heat. A better structure is needed for the federal government to seamlessly manage and build resilience. To streamline and improve the federal extreme heat response, the President must:

- Establish the National Integrated Heat-Health Information System (NIHHIS) Interagency Committee (IC). The IC will elevate the existing NIHHIS Interagency Working Group and empower it to shape and structure multi-agency heat initiatives under current authorities.

- Establish a National Heat Executive Council comprising representatives from relevant stakeholder groups (state and local governments, health associations, infrastructure professionals, academic experts, community organizations, technologists, industry, national laboratories, etc.) to inform the NIHHIS IC.

- Appoint a National Heat Coordinator (NHC). The NHC would sit in the Executive Office of the President and be responsible for achieving national heat preparedness and resilience. To be most effective, the NHC should:

- Work closely with the IC to create goals for heat preparedness and resilience in accordance with the National Heat Strategy, set targets, and annually track progress toward implementation.

- Each spring, deliver a National Heat Action Plan and National Heat Outlook briefing, modeled on the National Hurricane Outlook briefing, detailing how the federal government is preparing for forecasted extreme heat.

- Find areas of alignment with efforts to address other extreme weather threats.

- Direct the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the National Guard Bureau, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to create an incident command system for extreme heat emergencies, modeled on the National Hurricane Program.

- Direct the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to review agency budgets for extreme heat activities and propose crosscut budgets to support interagency efforts.

Boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience in every corner of our nation.

Extreme heat has become a national concern, threatening every community in the United States. To boost heat preparedness, response, and resilience nationwide, the President must:

- Direct FEMA to ensure that heat preparedness is a core component of national preparedness capabilities. At minimum, FEMA should support extreme heat regional scenario planning and tabletop exercises; incorporate extreme heat into Emergency Support Functions, the National Incident Management System, and the Community Lifelines program; help states, municipalities, tribes, and territories integrate heat into Hazard Mitigation Planning; work with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to provide language-accessible alerts via the Integrated Public Alert & Warning System; and clarify when extreme heat becomes a major disaster.

- Direct FEMA, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT), and other agencies that use Benefit-Cost Analysis (BCA) for funding decisions to ensure that BCA methodologies adequately represent impacts of extreme heat, such as economic losses, learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs. This may require updating existing methods to avoid systematically and unintentionally disadvantaging heat-mitigation projects.

- Direct FEMA, in accordance with Section 322 of the Stafford Act, to create guidance on extreme heat hazard mitigation and eligibility criteria for hazard mitigation projects.

- Direct agencies participating in the Thriving Communities Network to integrate heat adaptation into place-based technical assistance and capacity-building resources.

- Direct the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) to form a working group on accelerating resilience innovation, with extreme heat as an emphasis area. Within a year, the group should deliver a report on opportunities to use tools like federal research and development, public-private partnerships, prize challenges, advance market commitments, and other mechanisms to position the United States as a leader on game-changing resilience technologies.

Usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data.

Extreme heat’s impacts are not well-quantified, limiting a systematic national response. To usher in a new era of heat forecasting, research, and data, the President must:

- Direct the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Weather Service (NWS) to expand the HeatRisk tool to include Alaska, Hawaii, and U.S. territories; provide information on real-time health impacts; and integrate sector-specific data so that HeatRisk can be used to identify risks to energy and the electric grid, health systems, transportation infrastructure, and more.

- Direct NOAA, through NIHHIS, to rigorously assess the impacts of extreme heat on all sectors of the economy, including agriculture, energy, health, housing, labor, and transportation. In tandem, NIHHIS and OMB should develop metrics tracking heat impact that can be incorporated into agency budget justifications and used to evaluate federal infrastructure investments and grant funding.

- Direct the NIHHIS IC to establish a new working group focused on methods for measuring heat-related deaths, illnesses, and economic impacts. The working group should create an inventory of federal datasets that track heat impacts, such as the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) datasets and power outage data from the Energy Information Administration.

- Direct NWS to define extreme heat weather events, such as “heat domes”, which will help unlock federal funding and coordinate disaster responses across federal agencies.

Protect workers and businesses from heat.

Americans become ill and even die due to heat exposure in the workplace, a moral failure that also threatens business productivity. To protect workers and businesses, the President must:

- Finalize a strong rule to prevent heat injury and illness in the workplace. The Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA)’s August 2024 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking is a crucial step towards a federal heat standard to protect workers. OSHA should quickly finalize this standard prior to the 2025 heat season.

- Direct OSHA to continue implementing the agency’s National Emphasis Program on heat, which enforces employers’ obligation to protect workers against heat illness or injury. OSHA should additionally review employers’ practices to ensure that workers are protected from job or wage loss when extreme heat renders working conditions unsafe.

- Direct the Department of Labor (DOL) to conduct a nationwide study examining the impacts of heat on the U.S. workforce and businesses. The study should quantify and monetize heat’s impacts on labor, productivity, and the economy.

- Direct DOL to provide technical assistance to employers on tailoring heat illness prevention plans and implementing cost-effective interventions that improve working conditions while maintaining productivity.

Prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts.

Extreme heat is both a public health emergency and a chronic stress to healthcare systems. Addressing the chronic disease epidemic will be impossible without treating the symptom of extreme heat. To prepare healthcare systems for heat impacts, the President must:

- Direct the HHS Secretary to consider using their authority to declare a Public Health Emergency in the event of an extreme heat wave.

- Direct HHS to embed extreme heat throughout the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), including by:

- Developing heat-specific response guidance for healthcare systems and clinics.

- Establishing thresholds for mobilizing the National Disaster Medical System.

- Providing extreme heat training to the Medical Reserve Corps.

- Simulating the cascading impacts of extreme heat through Medical Response and Surge Exercise scenarios and tabletop exercises.

- Direct HHS and the Department of Education to partner on training healthcare professionals on heat illnesses, impacts, risks to vulnerable populations, and treatments.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to integrate resilience metrics, including heat resilience, into its quality measurement programs. Where relevant, environmental conditions, such as chronic high heat, should be considered in newly required screenings for the social determinants of health.

- Direct the CDC’s Collaborating Office for Medical Examiners and Coroners to develop a standard protocol for surveillance of deaths caused or exacerbated by extreme heat.

Ensure affordably cooled and heat-resilient housing, schools, and other facilities.

Cool homes, schools, and other facilities are crucial to preventing heat illness and death. To prepare the build environment for rising temperatures, the President must:

Promote Housing and Cooling Access

- Direct HUD to protect vulnerable populations by (i) updating Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to ensure that manufactured homes can maintain safe indoor temperatures during extreme heat, (ii) stipulating that mobile home park owners applying for Section 207 mortgages guarantee resident safety in extreme heat (e.g., by including heat in site hazard plans and allowing tenants to install cooling devices, cool walls, and shade structures), and (iii) guaranteeing that renters receiving housing vouchers or living in public housing have access to adequate cooling.

- Direct the Federal Housing Finance Agency to require that new properties must adhere to the latest energy codes and ensure minimum cooling capabilities in order to qualify for a Government Sponsored Enterprise mortgage.

- Ensure access to cooling devices as a medical necessity by directing the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) to include high-efficiency air conditioners and heat pumps in Publication 502, which defines eligible medical expenses for a variety of programs.

- Direct HHS to (i) expand outreach and education to state Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) administrators and subgrantees about eligible uses of funds for cooling, (ii) expand vulnerable populations criteria to include pregnant people, and (iii) allow weatherization benefits to apply to cool roofs and walls or green roofs.

- Direct agencies to better understand population vulnerability to extreme heat, such as by integrating the Census Bureau’s Community Resilience Estimates for Heat into existing risk and vulnerability tools and updating the American Community Survey with a question about cooling access to understand household-level vulnerability.

- Direct the Department of Energy (DOE) to work with its Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) contractors to ensure that home energy audits consider passive cooling interventions like cool walls and roofs, green roofs, strategic placement of trees to provide shading, solar shading devices, and high-efficiency windows.

- Extend the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC), and direct agencies involved in that initiative to (i) develop codes and metrics for sustainable and passive cooling, shade, materials selection, and thermal comfort, and (ii) identify opportunities to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation.

Prepare Schools and Other Facilities

- Direct the Department of Education to collect data to better understand how schools are experiencing and responding to extreme heat, and to strengthen education and outreach on heat safety and preparedness for schools. This should include sponsored sports teams and physical activity programs. The Department should also collaborate with USDA on strategies to braid funding for green and shaded schoolyards.

- Direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop extreme heat guidance and temperature standards for Early Childhood Facilities and Daycares.

- Direct USDA to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

- Direct the General Services Administration (GSA) to identify and pursue opportunities to demonstrate passive and resilient cooling strategies in public buildings.

- Direct the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to increase coordination with long-term care facilities during heat events to ensure compliance with existing indoor temperature regulations, develop plans for mitigating excess indoor heat, and build out energy redundancy plans, such as back-up power sources like microgrids.

- Direct the Bureau of Prisons, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement to collect data on air conditioning coverage in federal prisons and detention facilities and develop temperature standards that ensure thermal safety of inmates and the prison and detention workforce.

- Direct the White House Domestic Policy Council to create a Cool Corridors Federal Partnership, modeled after the Urban Waters Federal Partnership. The partnership of agencies would leverage data, research, and existing grant programs for community-led pilot projects to deploy heat mitigation efforts, like trees, along transportation routes.

Legislative Branch

Congress can support the President in combating extreme heat by increasing funds for heat-critical federal programs and by providing new and explicit authorities for federal agencies.

Treat extreme heat like the emergency it is.

Extreme heat has devastating human and societal impacts that are on par with other federally recognized disasters. To treat extreme heat like the emergency it is, Congress must:

- Institutionalize and provide long-term funding for the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS), the NIHHIS Interagency Committee (IC), and the National Heat Executive Council (NHEC), including functions and personnel. NIHHIS is critical to informing heat preparedness, response, and resilience across the nation. An IC and NHEC will ensure federal government coordination and cross-sector collaboration.

- Create the National Heat Commission, modeled on the Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission. The Commission’s first action should be creating a report for Congress on whole-of-government solutions to address extreme heat.

- Adopt H.R. 3965, which would amend the Stafford Act to explicitly include extreme heat in the definition of “major disaster”. Congress should also define the word “damages” in Section 102 of the Stafford Act to include impacts beyond property and economic losses, such as learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs.

- Direct and fund FEMA, NOAA, and CDC to establish a real-time heat alert system that aligns with the World Meteorological Organization’s Early Warnings for All program.

- Direct the Congressional Budget Office to produce a report assessing the costs of extreme heat to taxpayers and summarizing existing federal funding levels for heat.

- Appropriate full funding for emergency contingency funds for LIHEAP and the Public Health Emergency Program, and increase the annual baseline funding for LIHEAP.

- Update the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act to prohibit residential utilities from shutting off beneficiaries’ power during periods of extreme heat due to overdue bills.

- Adopt S. 2501, which would keep workers safe by requiring basic labor protections, such as water and breaks, in the event of indoor and outdoor extreme temperatures.

- Establish sector-specific Centers of Excellence for Heat Workplace Safety, beginning with military, transportation, and farm labor.

Build community heat resilience by readying critical infrastructure.

Investments in resilience pay dividends, with every federal dollar spent on resilience returning $6 in societal benefits. Our nation will benefit from building thriving communities that are prepared for extreme heat threats, adapted to rising temperatures, and capable of withstanding extreme heat disruptions. To build community heat resilience, Congress must:

- Establish the HeatSmart Grids Initiative as a partnership between DOE, FEMA, HHS, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the North American Electric Reliability Corporation, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). This initiative will ensure that electric grids are prepared for extreme heat, including risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency and public health responses. This program should (i) perform national audits of energy security and building-stock preparedness for outages, (ii) map energy resilience assets such as long-term energy storage and microgrids, (iii) leverage technologies for minimizing grid loads such as smart grids and virtual power plants, and (iv) coordinate protocols with FEMA’s Community Lifelines and CISA’s Critical Infrastructure for emergency response.

- Update the LIHEAP formula to better reflect cooling needs of low-income Americans.

- Amend Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act to clarify that Title I funds may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning loss; e.g., replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavements and solar and other shade canopies, green roofs, trees and green infrastructure to keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves.

- Direct the HHS Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying strategies for maximizing federal childcare assistance dollars during the hottest months of the year, when children are not in school. This could include protecting recent increased childcare reimbursements for providers who conform to cooling standards.

- Direct the HUD Secretary to submit a report to Congress identifying safe residential temperature standards for federally assisted housing units and proposing strategies to ensure compliance with the standards, such as extending utility allowances to cooling.

- Direct the DOT Secretary to conduct an independent third-party analysis of cool pavement products to develop metrics to evaluate thermal performance over time, durability, road subsurface temperatures, road surface longevity, and solar reflectance across diverse climatic conditions and traffic loads. Further, the analysis should assess (i) long-term performance and maintenance and (ii) benefits and potential trade-offs.

- Fund FEMA to establish a new federal grant program for community heat resilience, modeled on California’s “Extreme Heat and Community Resilience” program and in line with H.R. 9092. This program should include state agencies and statewide consortia as eligible grantees. States should be required to develop and adopt an extreme heat preparedness plan to be eligible for funds.

- Authorize and fund a new National Resilience Hub program at FEMA. This program would define minimum criteria that must be met for a community facility to be federally recognized as a resilience hub, and would provide funding to subsidize operations and emergency response functions of recognized facilities. Congress should also direct the FEMA Administrator to consider activities to build or retrofit a community facility meeting these criteria as eligible activities for Section 404 Hazard Mitigation Grants and funding under the Building Resilience Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program.

- Authorize and fund HHS to establish an Extreme Weather Resilient Health System Grant Program to prepare low-resource healthcare institutions (such as rural hospitals or federally qualified health centers) for extreme weather events.

- Fund the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to establish an Extreme Heat program and clearinghouse for design, construction, operation, and maintenance of buildings and infrastructure systems under extreme heat events.

- Fund HUD to launch an Affordable Cooling Housing Challenge to identify opportunities to lower the cost of new home construction and retrofits adapted to extreme heat.

- Expand existing rebates and tax credits (including HER, HEAR, 25C, 179D, Direct Pay) to include passive cooling tech such as cool walls, pavements, and roofs (H.R. 9894), green roofs, solar glazing, and solar shading. Revise 25C to be refundable at purchase.

- Authorize a Weatherization Readiness Program (H.R. 8721) to address structural, plumbing, roofing, and electrical issues, and environmental hazards with dwelling units unable to receive effective assistance from WAP, such as for implementing cool roofs.

- Fund the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) Urban and Community Forestry (UCF) Program to develop heat-adapted tree nurseries and advance best practices for urban forestry that mitigates extreme heat, such as strategies for micro forests.

Leveraging the Farm Bill to build national heat resilience.

Farm, food, forestry, and rural policy are all impacted by extreme heat. To ensure the next Farm Bill is ready for rising temperatures, Congress should:

- Double down on urban forestry, including by:

- Reauthorizing the UCF Grant program.

- Funding and directing the USFS UCF Program to support states, locals and Tribes on maintenance solutions for urban forests investments.

- Funding and authorizing a Green Schoolyards Grant under the UCF Program.

- Reauthorize the Farm Labor Stabilization and Protection Program, which supports employers in improving working conditions for farm workers.

- Reauthorize the Rural Emergency Health Care Grants and Rural Hospital Technical Assistance Program to provide resources and technical assistance to rural hospitals to prepare for emerging threats like extreme heat

- Direct the USDA Secretary to submit a report to Congress on the impacts of extreme heat on agriculture, expected costs of extreme heat to farmers (input costs and losses), consumers and the federal government (i.e. provision of SNAP benefits and delivery of insurance and direct payment for losses of agricultural products), and available federal resources to support agricultural and food systems adaptation to hotter temperatures.

- Authorize the following expansions:

- Agriculture Conservation Easement Program to include agrivoltaics.

- Environmental Quality Incentives Program to include facility cooling systems

- The USDA’s 504 Home Repair program to include funding for high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

- The USDA’s Community Facilities Program to include funding for constructing resilience centers.These resilience centers should be constructed to minimum standards established by the National Resilience Hub Program, if authorized.

- The USDA’s Rural Business Development Grant program to include high-efficiency air conditioning and other sustainable cooling systems.

Funding critical programs and agencies to build a heat-ready nation.

To protect Americans and mitigate the $160+ billion annual impacts of extreme heat, Congress will need to invest in national heat preparedness, response, and resilience. The tables on the following pages highlight heat-critical programs that should be extended, as well as agencies that need more funding to carry out heat-critical work, such as key actions identified in the Executive section of this Heat Policy Agenda.

Mobilizing Innovative Financial Mechanisms for Extreme Heat Adaptation Solutions in Developing Nations

Global heat deaths are projected to increase by 370% if direct action is not taken to limit the effects of climate change. The dire implications of rising global temperatures extend across a spectrum of risks, from health crises exacerbated by heat stress, malnutrition, and disease, to economic disparities that disproportionately affect vulnerable communities in the U.S. and in low- and middle-income countries. In light of these challenges, it is imperative to prioritize a coordinated effort at both national and international levels to enhance resilience to extreme heat. This effort must focus on developing and implementing comprehensive strategies to ensure the vulnerable developing countries facing the worst and disproportionate effects of climate change have the proper capacity for adaptation, as wealthier, developed nations mitigate their contributions to climate change.

To address these challenges, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) should mobilize finance through environmental impact bonds focused on scaling extreme heat adaptation solutions. USAID should build upon the success of the SERVIR joint initiative and expand it to include a partnership with NIHHIS to co-develop decision support tools for extreme heat. Additionally, the Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) within the USAID should take the lead in tracking and reporting on climate adaptation funding data. This effort will enhance transparency and ensure that adaptation and mitigation efforts are effectively prioritized. By addressing the urgent need for comprehensive adaptation strategies, we can mitigate the impacts of climate change, increase resilience through adaptation, and protect the most vulnerable communities from the increasing threats posed by extreme heat.

Challenge

Over the past 13 months, temperatures have hit record highs, with much of the world having just experienced their warmest June on record. Berkeley Earth predicts a 95% chance that 2024 will rank as the warmest year in history. Extreme heat drives interconnected impacts across multiple risk areas including: public health; food insecurity; health care system costs; climate migration and the growing transmission of life-threatening diseases.

Thus, as global temperatures continue to rise, resilience to extreme heat becomes a crucial element of climate change adaptation, necessitating a strategic federal response on both domestic and international scales.

Inequitable Economic and Health Impacts

Despite contributing least to global greenhouse gas emissions, low- and middle-income countries experience four times higher economic losses from excess heat relative to wealthier counterparts. The countries likely to suffer the most are those with the most humidity, i.e. tropical nations in the Global South. Two-thirds of global exposure to extreme heat occurs in urban areas in the Global South, where there are fewer resources to mitigate and adapt.

The health impacts associated with increased global extreme heat events are severe, with projections of up to 250,000 additional deaths annually between 2030 and 2050 due to heat stress, alongside malnutrition, malaria, and diarrheal diseases. The direct cost to the health sector could reach $4 billion per year, with 80% of the cost being shouldered by Sub-Saharan Africa. On the whole, low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South experience a higher portion of adverse health effects from increasing climate variability despite their minimal contributions to global greenhouse emissions, underscoring a clear global inequity challenge.

This imbalance points to a crucial need for a focus on extreme heat in climate change adaptation efforts and the overall importance of international solidarity in bolstering adaptation capabilities in developing nations. It is more cost-effective to prepare localities for extreme heat now than to deal with the impacts later. However, most communities do not have comprehensive heat resilience strategies or effective early warning systems due to the lack of resources and the necessary data for risk assessment and management — reflected by the fact that only around 16% of global climate financing needs are being met, with far less still flowing to the Global South. Recent analysis from Climate Policy Initiative, an international climate policy research organization, shows that the global adaptation funding gap is widening, as developing countries are projected to require $212 billion per year for climate adaptation through 2030. The needs will only increase without direct policy action.

Opportunity: The Role of USAID in Climate Adaptation and Resilience

As the primary federal agency responsible for helping partner countries adapt to and build resilience against climate change, USAID announced multiple commitments at COP28 to advance climate adaptation efforts in developing nations. In December 2023, following COP28, Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry and USAID Administrator Power announced that 31 companies and partners have responded to the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE) Call to Action and committed $2.3 billion in additional adaptation finance. Per the State Department’s December 2023 Progress Report on President Biden’s Climate Finance Pledge, this funding level puts agencies on track to reach President Biden’s pledge of working with Congress to raise adaptation finance to $3 billion per year by 2024 as part of PREPARE.

USAID’s Bureau for Resilience, Environment, and Food Security (REFS) leads the implementation of PREPARE. USAID’s entire adaptation portfolio was designed to contribute to PREPARE and align with the Action Plan released in September 2022 by the Biden Administration. USAID has further committed to better integrating adaptation in its Climate Strategy for 2022 to 2030 and established a target to support 500 million people’s adaptation efforts.

This strategy is complemented by USAID’s efforts to spearhead international action on extreme heat at the federal level, with the launch of its Global Sprint of Action on Extreme Heat in March 2024. This program started with the inaugural Global Heat Summit and ran through June 2024, calling on national and local governments, organizations, companies, universities, and youth leaders to take action to help prepare the world for extreme heat, alongside USAID Missions, IFRC and its 191-member National Societies. The executive branch was also advised to utilize the Guidance on Extreme Heat for Federal Agencies Operating Overseas and United States Government Implementing Partners.

On the whole, the USAID approach to climate change adaptation is aimed at predicting, preparing for, and mitigating the impacts of climate change in partner countries. The two main components of USAID’s approach to adaptation include climate risk management and climate information services. Climate risk management involves a “light-touch, staff-led process” for assessing, addressing, and adaptively managing climate risks in non-emergency development funding. The climate information services translate data, statistical analyses, and quantitative outputs into information and knowledge to support decision-making processes. Some climate information services include early warning systems, which are designed to enable governments’ early and effective action. A primary example of a tool for USAID’s climate information services efforts is the SERVIR program, a joint development initiative in partnership with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) to provide satellite meteorology information and science to partner countries.

Additionally, as the flagship finance initiative under PREPARE, the State Department and USAID, in collaboration with the U.S. Development Finance Corporation (DFC), have opened an Adaptation Finance Window under the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), which aims to de-risk the development and scaling of companies and investment vehicles that mobilize private finance for climate adaptation.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1: Mobilize private capital through results-based financing such as environmental impact bonds

Results-based financing (RBF) has long been a key component of USAID’s development aid strategy, offering innovative ways to mobilize finance by linking payments to specific outcomes. In recent years, Environmental Impact Bonds (EIBs) have emerged as a promising addition to the RBF toolkit and would greatly benefit as a mechanism for USAID to mobilize and scale novel climate adaptation. Thus, in alignment with the PREPARE plan, USAID should launch an EIB pilot focused on extreme heat through the Climate Finance for Development Accelerator (CFDA), a $250 million initiative designed to mobilize $2.5 billion in public and private climate investments by 2030. An EIB piloted through the CFDA can help unlock public and private climate financing that focuses on extreme heat adaptation solutions, which are sorely needed.

With this EIB pilot, the private sector, governments, and philanthropic investors raise the upfront capital and repayment is contingent on the project’s success in meeting predefined goals. By distributing financial risk among stakeholders in the private sector, government, and philanthropy, EIBs encourage investment in pioneering projects that might struggle to attract traditional funding due to their novel or unproven nature. This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

This approach can effectively mobilize the necessary resources to drive climate adaptation solutions.

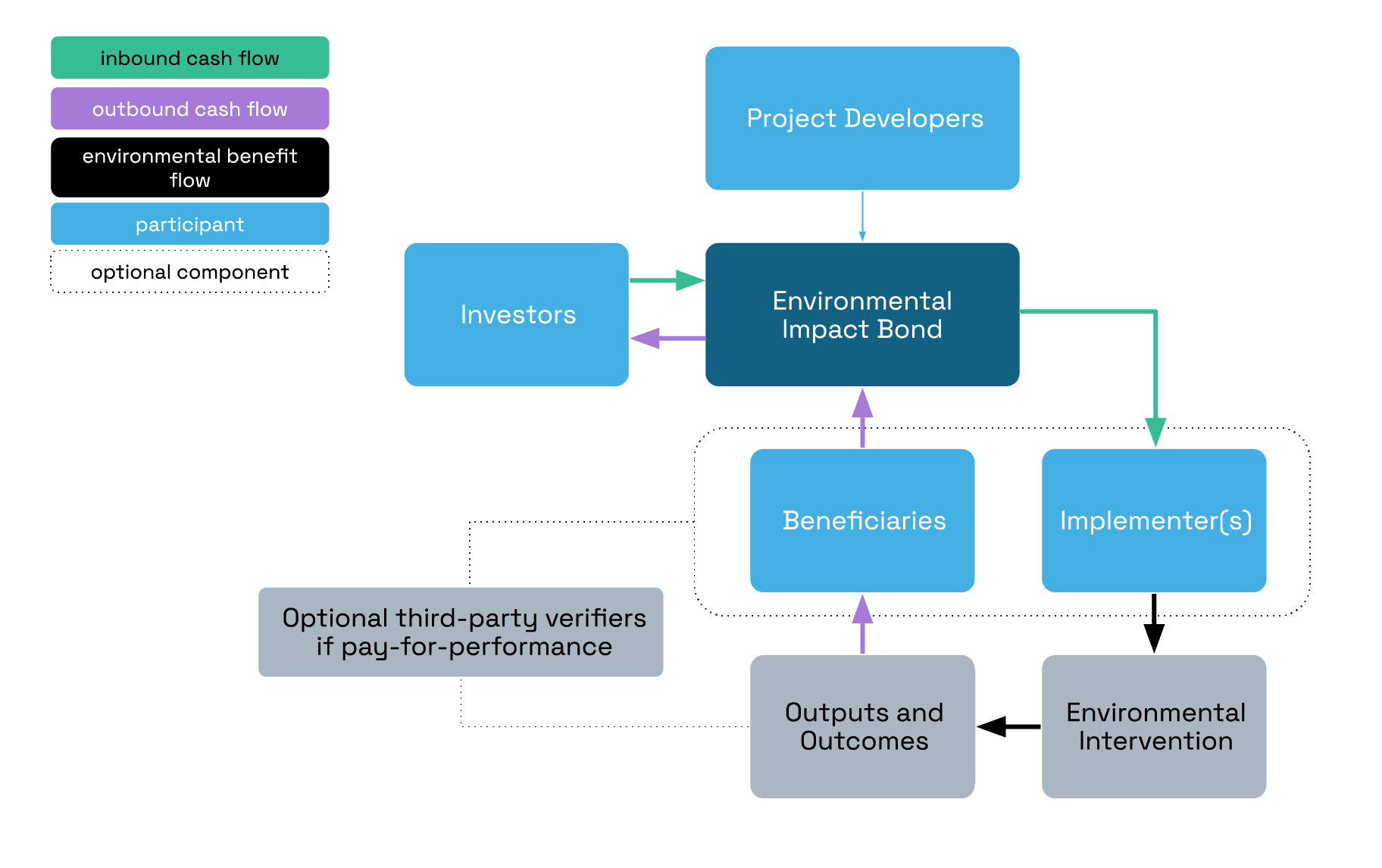

Overview of EIB structure, including cash flow (purple and green arrows) and environmental benefits (black arrows).

Adapted from Environmental Impact Bonds: a common framework and looking ahead

The USAID EIB pilot should focus on scaling projects that facilitate uptake and adoption of affordable and sustainable cooling systems such as solar-reflective roofing and other passive cooling strategies. In Southeast Asia alone, annual heat-related mortality is projected to increase by 295% by 2030. Lack of access to affordable and sustainable cooling mechanisms in the wake of record-shattering heat waves affects public health, food and supply chain, and local economies. An EIB that aims to fund and scale solar-reflective roofing (cool roofs) has the potential to generate high impact for the local population by lowering indoor temperature, reducing energy use for air conditioning, and mitigating the heat island effect in surrounding areas. Indonesia, which is home to 46.5 million people at high risk from a lack of access to cooling, has seen notable success in deploying cool roofs/solar-reflective roofing through the Million Cool Roof Challenge, an initiative of the Clean Cooling Collaborative. The country is now planning to scale production capacity of cool roofs and set up its first testing facility for solar-reflective materials to ensure quality and performance. Given Indonesia’s capacity and readiness, an EIB to scale cool roofs in Indonesia can be a force multiplier to see this cooling mechanism reach millions and spur new manufacturing and installation jobs for the local economy.

To mainstream EIBs and other innovative financial instruments, it is essential to pilot and explore more EIB projects. Cool roofs are an ideal candidate for scaling through an EIB due to their proven effectiveness as a climate adaptation solution, their numerous co-benefits, and the relative ease with which their environmental impacts can be measured (such as indoor temperature reductions, energy savings, and heat island index improvements). Establishing an EIB can be complex and time-consuming, but the potential rewards make the effort worthwhile if executed effectively. Though not exhaustive, the following steps are crucial to setting up an environmental impact bond:

Analyze ecosystem readiness

Before launching an environmental impact bond, it’s crucial to conduct an analysis to better understand what capacities already exist among the private and public sectors in a given country to implement something like an EIB. Additionally working with local civil society organizations is important to ensure climate adaptation projects and solutions are centered around the local community.

Determine the financial arrangement, scope, and risk sharing structure

Determine the financial structure of the bond, including the bond amount, interest rate, and maturity date. Establish a mechanism to manage the funds raised through the bond issuance.

Co-develop standardized, scientifically verified impact metrics and reporting mechanism

Develop a robust system for measuring and reporting the environmental impact projects; With key stakeholders and partner countries, define key performance indicators (KPIs) to track and report progress.

USAID has already begun to incubate and pilot innovative financing mechanisms in the global health space through development impact bonds. The Utkrisht Impact Bond, for example, is the world’s first maternal and newborn health impact bond, which aims to reach up to 600,000 pregnant women and newborns in Rajasthan, India. Expanding the use case of this financing mechanism in the climate adaptation sector can further leverage private capital to address critical environmental challenges, drive scalable solutions, and enhance the resilience of vulnerable communities to climate impacts.

Recommendation 2: USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NIHHIS and co-develop decision support tools such as an intersectional vulnerability map.

Building on the momentum of Administrator Power’s recent announcement at COP28, USAID should expand the SERVIR joint initiative to include a partnership with NOAA, specifically with NIHHIS, the National Integrated Heat Health Information System. NIHHIS is an integrated information system supporting equitable heat resilience, which is an important area that SERVIR should begin to explore. Expanded partnerships could begin with a pilot to map regional extreme heat vulnerability in select Southeast Asian countries. This kind of tool can aid in informing local decision makers about the risks of extreme heat that have many cascading effects on food systems, health, and infrastructure.

Intersectional vulnerabilities related to extreme heat refer to the compounding impacts of various social, economic, and environmental factors on specific groups or individuals. Understanding these intersecting vulnerabilities is crucial for developing effective strategies to address the disproportionate impacts of extreme heat. Some of these intersections include age, income/socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, gender, and occupation. USAID should partner with NIHHIS to develop an intersectional vulnerability map that can help improve decision-making related to extreme heat. Exploring the intersectionality of extreme heat vulnerabilities is critical to improving local decision-making and helping tailor interventions and policies to where it is most needed. The intersection between extreme heat and health, for example, is an area that is under-analyzed, and work in this area will contribute to expanding the evidence base.

The pilot can be modeled after the SERVIR-Mekong program, which produced 21 decision support tools throughout the span of the program from 2014-2022. The SERVIR-Mekong program led to the training of more than 1,500 people, the mobilization of $500,000 of investment in climate resilience activities, and the adoption of policies to improve climate resilience in the region. In developing these tools, engaging and co-producing with the local community will be essential.

Recommendation 3: USAID REFS and the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance should work together to develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. This also requires USAID and the State Department to develop clear guidelines on the U.S. approach to adaptation tracking and determination of adaptation components.

Enhancing analytical and data collection capabilities is vital for crafting effective and informed responses to the challenges posed by extreme heat. To this end, USAID REFS, along with the State Department Office of Foreign Assistance, should co-develop a mechanism to consistently track and report climate funding flow. Currently, both USAID and the State Department do not consistently report funding data on direct and indirect climate adaptation foreign assistance. As the Department of State is required to report on its climate finance contributions annually for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and biennially for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the two agencies should report on adaptation funding at similarly set, regular interval and make this information accessible to the executive branch and the general public. A robust tracking mechanism can better inform and aid agency officials in prioritizing adaptation assistance and ensuring the US fulfills its commitments and pledges to support global adaptation to climate change.

The State Department Office of Foreign Assistance (State F) is responsible for establishing standard program structures, definitions, and performance indicators, along with collecting and reporting allocation data on State and USAID programs. Within the framework of these definitions and beyond, there is a lack of clear definitions in terms of which foreign assistance projects may qualify as climate projects versus development projects and which qualify as both. Many adaptation projects are better understood on a continuum of adaptation and development activities. As such, this tracking mechanism should be standardized via a taxonomy of definitions for adaptation solutions.

Therefore, State F should create standardized mechanisms for climate-related foreign assistance programs to differentiate and determine the interlinkages between adaptation and mitigation action from the outset in planning, finance, and implementation — and thereby enhance co-benefits. State F relies on the technical expertise of bureaus, such as REFS, and the technical offices within them, to evaluate whether or not operating units have appropriately attributed funding that supports key issues, including indirect climate adaptation.

Further, announced at COP26, PREPARE is considered the largest U.S. commitment in history to support adaptation to climate change in developing nations. The Biden Administration has committed to using PREPARE to “respond to partner countries’ priorities, strengthen cooperation with other donors, integrate climate risk considerations into multilateral efforts, and strive to mobilize significant private sector capital for adaptation.” Co-led by USAID and the U.S. Department of State (State Department), the implementation of PREPARE also involves the Treasury, NOAA, and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Other U.S. agencies, such as USDA, DOE, HHS, DOI, Department of Homeland Security, EPA, FEMA, U.S. Forest Service, Millennium Challenge Corporation, NASA, and U.S. Trade and Development Agency, will respond to the adaptation priorities identified by countries in National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) and nationally determined contributions (NDCs), among others.

As USAID’s REFS leads the implementation of the PREPARE and hosts USAID’s Chief Climate Officer, this office should be responsible for ensuring the agency’s efforts to effectively track and consistently report climate funding data. The two REFS Centers that should lead the implementation of these efforts include the Center for Climate-Positive Development, which advises USAID leadership and supports the implementation of USAID’s Climate Strategy, and the Center for Resilience, which supports efforts to help reduce recurrent crises — such as climate change-induced extreme weather events — through the promotion of risk management and resilience in the USAID’s strategies and programming.

In making standardized processes to prioritize and track the flow of adaptation funds, USAID will be able to more effectively determine its progress towards addressing global climate hazards like extreme heat, while enhancing its ability to deliver innovative finance and private capital mechanisms in alignment with PREPARE. Additionally, standardization will enable both the public and private sectors to understand the possible areas of investment and direct their flows for relevant projects.

USAID uses the Standardized Program Structure and Definitions (SPSD) system — established by State F — to provide a common language to describe climate change adaptation and resilience programs and therefore enable the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data within a country, regionally or globally. The SPSD system uses the following categories: (1) democracy, human rights, and governance; (2) economic growth; (3) education and social services; (4) health; (5) humanitarian assistance; (6) peace and security; and (7) program development and oversight. Since 2016, climate change has been in the economic growth category and each climate change pillar has separate Program Areas and Elements. The SPSD consists of definitions for foreign assistance programs, providing a common language to describe programs. By utilizing a common language, information for various types of programs can be aggregated within a country, regionally, or globally, allowing for the comparison and analysis of budget and performance data.

Using the SPSD program areas and key issues, USAID categorizes and tracks the funding for its allocations related to climate adaptation as either directly or indirectly addressing climate adaptation. Funding that directly addresses climate adaptation is allocated to the “Climate Change—Adaptation” under SPSD Program Area EG.11 for activities that enhance resilience and reduce the vulnerability to climate change of people, places, and livelihoods. Under this definition, adaptation programs may have the following elements: improving access to science and analysis for decision-making in climate-sensitive areas or sectors; establishing effective governance systems to address climate-related risks; and identifying and disseminating actions that increase resilience to climate change by decreasing exposure or sensitivity or by increasing adaptive capacity. Funding that indirectly addresses climate adaptation is not allocated to a specific SPSD program area. It is funding that is allocated to another SPSD program area and also attributed to the key issue of “Adaptation Indirect,” which is for adaptation activities. The SPSD program area for these activities is not Climate Change—Adaptation, but components of these activities also have climate adaptation effects.

In addition to the SPSD, the State Department and USAID have also identified “key issues” to help describe how foreign assistance funds are used. Key issues are topics of special interest that are not specific to one operating unit or bureau and are not identified, or only partially identified, within the SPSD. As specified in the State Department’s foreign assistance guidance for key issues, “operating units with programs that enhance climate resilience, and/or reduce vulnerability to climate variability and change of people, places, and/or livelihoods are expected to attribute funding to the Adaptation Indirect key issue.”

Operating units use the SPSD and relevant key issues to categorize funding in their operational plans. State guidance requires that any USAID operating unit receiving foreign assistance funding must complete an operational plan each year. The purpose of the operational plan is to provide a comprehensive picture of how the operating unit will use this funding to achieve foreign assistance goals and to establish how the proposed funding plan and programming supports the operating unit, agency, and U.S. government policy priorities. According to the operational plan guidance, State F does an initial screening of these plans.

MDBs play a critical role in bridging the significant funding gap faced by vulnerable developing countries that bear a disproportionate burden of climate adaptation costs—estimated to reach up to 20 percent of GDP for small island nations exposed to tropical cyclones and rising seas. MDBs offer a range of financing options, including direct adaptation investments, green financing instruments, and support for fiscal adjustments to reallocate spending towards climate resilience. To be most sustainably impactful, adaptation support from MDBs should supplement existing aid with conditionality that matches the institutional capacities of recipient countries.

In January 2021, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO 14008) calling upon federal agencies and others to help domestic and global communities adapt and build resilience to climate change. Shortly thereafter in September 2022, the White House announced the launch of the PREPARE Action Plan, which specifically lays out America’s contribution to the global effort to build resilience to the impacts of the climate crisis in developing countries. Nineteen U.S. departments and agencies are working together to implement the PREPARE Action Plan: State, USAID, Commerce/NOAA, Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), U.S. Trade and Development Agency (USTDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Treasury, DFC, Department of Defense (DOD) & U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), International Trade Administration (ITA), Peace Corps, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Energy (DOE), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), Department of Transportation (DOT), Health and Human Services (HHS), NASA, Export–Import Bank of the United States (EX/IM), and Department of Interior (DOI).

Congress oversees federal climate financial assistance to lower-income countries, especially through the following actions: (1) authorizing and appropriating for federal programs and multilateral fund contributions, (2) guiding federal agencies on authorized programs and appropriations, and (3) overseeing U.S. interests in the programs. Congressional committees of jurisdiction include the House Committees on Foreign Affairs, Financial Services, Appropriations, and the Senate Committees on Foreign Relations and Appropriations, among others.

Federation of American Scientists among leading voices for federal policy action at White House Summit on Extreme Heat

Summit comes on heels of record 2024 summer heat; convenes experts on strategies to address this nationwide threat

Washington, D.C. – September 13, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS), the non-partisan, nonprofit science think tank dedicated to deploying evidence-based policies to address national threats, is today participating in the White House Summit on Extreme Heat.

This Summit, announced by President Biden earlier this summer, will bring together local, state, Tribal, and territorial leaders and practitioners to discuss how to drive further locally-tailored and community-driven actions to address extreme heat. FAS has been a leading voice for action on this topic, and has developed a compendium of 150+ heat-related federal policy recommendations.

FAS will be represented by Hannah Safford, Associate Director of Climate and Environment, and Grace Wickerson, Health Equity Policy Manager.

“Extreme heat is affecting every corner of our nation, making it more difficult and dangerous for Americans to live, work, and play,” says Wickerson. “Heat-related deaths and illnesses are on the rise, especially among our most vulnerable populations. We must work together to tackle this public health crisis.”

“It’s September, and millions of Americans are still suffering in triple-digit temperatures,” adds Safford. “We applaud the Biden-Harris Administration for drawing attention to the increasing challenges of extreme heat, and for driving on action to build a more heat-resilient nation in 2025 and beyond.”

FAS’s Ongoing Work to Address Extreme Heat

To date FAS has fostered extensive policy innovation related to extreme heat:

- Our Extreme Heat Policy Sprint engaged more than 85 experts and generated heat-related policy recommendations for 34 federal offices and agencies.

- This work is comprehensively summarized in our Whole-of-Government Strategy To Address Extreme Heat, and our associated library of heat policy memos.

- FAS has delivered expert briefings on extreme heat to the White House and federal agencies. Our policy solutions have informed Senate appropriations requests, proposed legislation, and Congressional Research Service reports.

FAS Workshops Will Harness Momentum From White House Summit

Immediately following the White House Heat Summit, FAS will collaborate with the Arizona State University (ASU) Knowledge Exchange for Resilience to host the Celebration for Resilience 2024 Symposium and Gala on September 19th in Tempe.

On Friday, September 20th, FAS will partner with Arizona State University (ASU) to host workshops in Tempe, AZ, Washington DC, and virtually on Defining the 2025 Heat Policy Agenda. This workshop will harness momentum from the White House Summit on Extreme Heat, providing a forum to discuss actions that the next Administration and new Congress should prioritize to tackle extreme heat. For more information and to participate, contact Grace Wickerson (gwickerson@fas.org).

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Keeping People Cool In A Heating World

Extreme heat is the deadliest weather phenomenon in the United States — more lethal than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined. And, as extreme temperatures rise, so do American household energy bills. An alarming 16% (20.9 million) of U.S. households are behind on their energy bills and at an increased risk of utility shut-offs.

Many households rely on electrical power systems like air conditioning (AC) to combat immediate heat effects, increasing energy demand and straining power transmission capabilities, non-reliability, and energy insecurity. Even as increasingly warmer winter months due to climate change reduce the need for heating, this indicates a future with increased energy demand for cooling. In the U.S., projected changes in cooling degree days — the metric to estimate how much cooling is needed to maintain a comfortable indoor air temperature — are expected to drive a 71% increase in household cooling demand by 2050, according to the latest annual energy outlook from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

Increasingly excessive heat is, therefore, a financial burden for many people, particularly low-income households. This is especially the case as low-income households tend to live in less energy-efficient homes that are more expensive to cool. The inability to afford household energy needs — that is, energy insecurity — makes it a challenge to stay cool, comfortable, and healthy during periods of extreme heat. Thus, as the impacts of extreme heat and energy insecurity are not distributed evenly, it is increasingly essential for the federal government to consider equity and prioritize disadvantaged populations in its efforts to tackle these intertwined crises.

Extreme Heat Drives Energy Burdens and Utility Insecurities

Energy insecurity refers to an individual or household’s inability to adequately meet basic household energy needs, like cooling and heating. Extreme heat compounds existing energy insecurities by surging the need for AC and other electrical sources of cooling technology. Thus, as the demand for cooling during summer increases energy consumption, many households cannot afford to run their AC, leading to life-threatening living conditions. According to the latest EIA Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS), a striking one in five households reported reducing or forgoing necessities like food and medicine to pay an energy bill. Over 10% of households reported keeping their home at an unhealthy or unsafe temperature due to costs.

Additionally, while household access to AC has increased over the years, a significant one in eight U.S. homes on average are still lacking AC, with renters going without at a higher rate than homeowners. The lack of access to cooling may be particularly hazardous for low-income, renter, rural, or elderly households, especially for those with underlying health conditions and those living in heat islands—urban areas where temperatures are higher than surrounding rural and suburban areas.

Another critical issue is that at least three million U.S. utility customers have their power disconnected every year due to payment challenges, yet 31 states have no policy preventing energy shut-offs during excessive heat events. The states that do have policies vary widely in their cut-off points and protection policies. Across the board, low-income people are disproportionately facing disconnections and are often charged a “reconnect fee” or a deposit after a cutoff.

As of 2021, 29 states had seasonal protections and 23 had temperature-based disconnection protections that prohibit utility companies from disconnecting power. Still, research from the Indiana University Energy Justice Lab shows that these do not fully prohibit disconnections, often putting the onus on customers to demonstrate eligibility for an exemption, such as medical need. Further, while 46 states, along with Washington D.C., give customers the option to set up a payment plan as an alternative to disconnection, high interest rates may be costly, and income-based repayment is rarely an option.

These cut-off policies are all set at the state level, and there is still an ongoing need to identify best practices that save lives. Policymakers can use utility regulations to protect residents from the financial burden of extreme heat events. For example, Phoenix passed a policy that went into effect in 2022 and prevents both residential energy disconnections in summer months (through October 2024) and late fees incurred during this time for residents who owe less than $300. Also, some stakeholders in Massachusetts are considering “networked geothermal energy with microdistricts” — also known as geogrids — to build the physical capability to transfer cool air through a geothermal network. This could allow different energy users to trade hot and cool air, in order to move cool air from members who can pay for it to those who cannot.

Grid Insecurity

Extreme heat also poses a significant threat to national energy grid infrastructure by increasing the risk of power outages due to increased energy consumption. Nationwide, major power outages have increased tenfold since 1980, largely because of damages from extreme weather and aging grid infrastructure. Regions not accustomed to experiencing extreme heat and lacking the infrastructure to deal with it will now become particularly vulnerable. Disadvantaged neighborhoods in urban heat islands also face heightened risks as they more frequently lack the essential infrastructure needed to adapt to the changing climate. For example, grid infrastructure in California’s urban disadvantaged communities has been shown to be weaker and less ready to support electric appliances.

Similarly, rural communities face unique challenges in preparing for disasters that could lead to power loss. Geographic isolation, limited resources, and older infrastructure are all factors that make power outages more frequent and long-lasting in rural areas. These factors also affect the frequency of maintenance service and speed of repairs. In addition, rural areas often have less access to emergency services and cooling centers, making power outages during extreme heat events additionally hazardous. Power outages during extreme heat events increase the risks for heat-related illnesses such as fainting, heat exhaustion, and heatstroke. And, for rural homes that rely on well water, losing power can mean losing access to water, since well systems rely on electrical pumps to bring water into the home.

Further heightening the need for urgency to consider these especially vulnerable populations and regions, research has shown that the time to restore power after an outage is significantly longer for rural communities and in low-income communities of color. Power restoration time reflects which communities are prioritized and, as a result, which communities are neglected.

Equity Considerations For Different Housing Types

Extreme heat and energy security cannot be addressed without considering equity, as the impacts are not distributed evenly, especially by race, income, and housing type. One example of this intersection: Black renters have faced disproportionate burdens of extreme heat and energy security, as wealth is deeply correlated with race and homeownership in the U.S. In 2021, the EPA reported that Black people are 40% more likely than non-Black people to live in areas with the highest projected increase in mortality rates due to extreme temperatures. Simultaneously, a 2020 analysis by the Brookings Institute found that Black renters had greater energy insecurity than white renters, Black homeowners, and white homeowners. Beyond the cost burden of staying cool, this energy security puts lives at greater risk of heat-related illness and death and hinders economic mobility.

This paradigm reflects historic, discriminatory housing policies like redlining. Such policies segregated neighborhoods, induced lower homeownership rates, and ensured underinvestment in low-income communities of color—all of these factors play a significant part in making Black residents more vulnerable to the effects of extreme heat. Further compounding this, a 2020 study of more than 100 cities across the U.S. found that 94% of formerly redlined areas are hotter than non-redlined areas; in the summer, this difference can be as high as 12.6℉.

Nationwide, households living in manufactured homes also face disproportionate risks and impacts, with about 25% having incomes at or below the federal poverty level. At the same time, manufactured homes consume 70% more per square foot on energy than site-built homes, while using 35% less energy due to their smaller size. Notably, about 70% of all manufactured homes are located in rural areas, which on average have higher median energy burdens than metropolitan areas.

Further, older manufactured housing units are often in inadequate condition and do not meet building codes established after 1976. However, research has shown that the vulnerability of households living in manufactured housing units to extreme temperatures is only partially related to whether they have AC systems installed. Other key factors that residents report to drive vulnerability include AC units that do not work efficiently, are located in less-used parts of the house, or are ineffective in maintaining comfortable temperatures. These factors hamper manufactured housing residents’ ability to control their home’s thermal environment — thereby driving thermal insecurity.

Manufactured housing households facing challenges with resource access (such as exclusions from assistance programs and lack of credit access), physical health and mental limitations, care burdens, and documentation status may be at disproportionate risk. These households deal with multiple, intersecting vulnerabilities and often must engage in trade-off behavior to meet their most immediate needs, sacrificing their ability to address unsafe temperatures at home. They often take adapting to the increasingly extreme climate into their own hands, using various ways to cope with thermal insecurity, such as installing dual-pane windows, adding insulation, planting shade trees, using supplemental mobile AC units, and even leaving home to visit local air-conditioned malls.

These overlapping paradigms showcase the intrinsic interconnectedness among climate justice, climate justice, energy justice, and housing justice. Essentially, housing equity cannot be pursued without energy justice and climate justice, as the conditions for realizing each of these concepts entail the conditions for the others. Realizing these conditions will require substantial investment and funding for climate programs to include heat governance, housing resilience, and poverty alleviation policies.

Policy Considerations

Energy Burdens and Utility Insecurity

Update the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)

The Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) exists to relieve energy burdens, yet was designed primarily for heating assistance. Thus, the LIHEAP formulas advantage states with historically cooler climates. To put this in perspective, some states with the highest heat risk — such as Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, and Utah — offer no cooling assistance funds from LIHEAP. Despite their warm climates, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, and Hawai’i all limit LIHEAP cooling assistance per household to less than half the available heating assistance benefit. And, since most states use their LIHEAP budgets for heating first, very little remains for cooling assistance — in some cases, cooling assistance is not offered at all. As a result, from 2001 to 2019, only 5% of national energy assistance went to cooling.

For vulnerable households, the lack of cooling assistance is compounded by a lack of disconnection protections from extreme heat. Thus, with advanced forecasts, LIHEAP should also be deployed both to restore disconnected electric service and to make payments on energy bills, which may surge even higher with the increase in demand response pricing due to more extreme temperatures. The distribution of LIHEAP funds to the most vulnerable households should also be maximized. As most states do not have firm guidelines on which households to distribute LIHEAP funds to and use a modified “first-come, first-served” approach, a small number of questions specific to heat risk could be added to LIHEAP applications and used to generate a household heat vulnerability score.

Further, the LIHEAP program is massively oversubscribed, and can only service a portion of in-need families. To adapt to a hotter nation and world at large, the annual budgets for LIHEAP must increase and the allocation formulas will need to be made more “cooling”-aware and equitable for hot-weather states. The FY25 presidential budget keeps LIHEAP’s funding levels at $4.1 billion, while also proposing expanding eligible activities that will draw on available resources. Analysis from the National Energy Assistance Directors Association found that this funding level could cut off up to 1.5 million families from the program and remove program benefits like cooling.

Reform the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA)

While PURPA prohibits electric utilities from shutting off home electricity for overdue bills when doing so would be dangerous for someone’s health, it does not have explicit protections for extreme temperatures. The federal government could consider reforms to PURPA that require utilities to have moratoriums on energy shut-offs during extreme heat seasons.

Housing Improvements

Expand Weatherization Assistance Programs

Weatherization aims to make homes more energy efficient and comfortable in various climates through actions, such as attic and wall insulation, air sealing, or adding weather stripping to doors and windows. More than half of cities have a weatherization program. The Department of Energy (DOE) Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) funding is available for states and other entities to retrofit older homes for improved energy efficiency to power cooling technologies like AC. However, similar to LIHEAP, WAP primarily focuses on support for heating-related repairs rather than cooling. For all residential property types, weatherization audits, through WAP and LIHEAP, can be expanded to consider heat resilience and cooling efficiency of the property and then identify upgrades such as more efficient AC, building envelope improvements, cool roofs, cool walls, shade, and other infrastructure.

Further, weatherization can be complicated when trying to help the most vulnerable populations. As some of the houses are in such poor condition that they do not qualify for weatherization, there is a need for nationwide access to pre-weatherization assistance programs. These programs address severe conditions in a home that would cause a home to be deferred from the federal WAP because the conditions would make the weatherization measures unsafe or ineffective. Pre-weatherization assistance programs are typically run by the State WAP Office or administered in partnership with another state office.

Additionally, as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IJA) allocated roughly $3.5 billion to WAP, states should utilize this funding to target energy-insecure neighborhoods with high rates of rental properties. Doing so will help states prioritize decreasing energy insecurity and its associated safety risks for some of the most vulnerable households.

Increase Research on Federal Protections for Vulnerable Housing Types

There is a need for a nationwide policy for secure access to cooling. While the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) does not regulate manufactured home parks, it does finance the parks through Section 207 mortgages. HUD could stipulate park owners must guarantee resident safety. This agency could also update the Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to allow for AC and other cooling regulations in local building codes to apply to manufactured homes, as they do for other forms of housing, as well as require homes perform to a certain level of cooling under high heat conditions. Additionally, to support lower-cost retrofit methods for manufactured homes and other vulnerable housing types, new approaches to financing, permitting, and incentivizing building retrofits should be developed, per the Biden-Harris Administration’s Climate Resilience Game Changers Assessment. HUD’s Green and Resilient Retrofit Program, which provides climate resilience funding to affordable housing properties, can serve as a model.

Further, as home heat-risk remains under-studied and under-addressed by hazard mitigation planning, and policy processes, there needs to be better measures of home thermal security. Without better data, homes will continue to be overlooked in state and federal climate and adaptation efforts.

Grid Resilience and Energy Access

Prioritize access to affordable, resilient energy alternatives for energy-insecure individuals

The most long-term investment in reducing energy insecurity and climate vulnerability is ensuring the most energy insecure populations have access to alternative, renewable energy sources, such as wind and solar. This is a core focus of the DOE Energy Futures Grant (EFG) program, which provides $27 million in financial assistance and technical assistance to local- and state-led partnership efforts for increasing access to affordable clean energy. EFG is a Justice 40 program, and required to ensure 40% of the overall benefits of its federal investments flow to disadvantaged communities. Programs like EFG can serve as a model for federal efforts to reduce energy cost burdens, while simultaneously reducing dependence on nonrenewable energy sources like oil and natural gas.

Accelerate Energy-Efficient Infrastructure

Efficient AC technologies, such as air source heat pumps, can help make cooling more affordable. Therefore, resilient cooling strategies, like high-energy efficiency cooling systems, demand/response systems, and passive cooling interventions, need federal policy actions to rapidly scale for a warming world. For example, cool roofs, walls, and surfaces can keep buildings cool and less reliant on mechanical cooling, but are often not considered a part of weatherization audits and upgrades. District cooling, such as through networked geothermal, can keep entire neighborhoods cool while relying on little electricity. However, this is still in the demonstration project phase in the U.S. Initiatives like the DOE Affordable Home Energy Shot can bring new resilient cooling technologies into reach for millions of Americans, but only if it is given sufficient financial resources. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program can further incentivize low-power and resilient cooling technologies if rebates are designed that take advantage of these technologies.

Making the Most of OSHA’s Extreme Heat Rule

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- OSHA’s proposed heat safety standard is a critical step towards protecting millions of workers, but its success depends on substantial infrastructure investment.

- Effective implementation requires a multifaceted approach, improving workforce development, employer and industry resources, regulatory capacity, healthcare access and community support.

- Federal government plays a pivotal role through funding, grants, technical assistance, and interagency collaboration to protect workers from the effects of extreme heat.

- Investing in heat safety infrastructure offers multiple benefits: lives saved, injuries prevented, economic protection, and enhanced climate resilience.

- Challenges to implementation include regulatory delays, insufficient funding, financial constraints for small businesses, diverse settings, rural infrastructure limitations, and lack of awareness.

- Overcoming these challenges requires dedicated funding sources, financial incentives, tailored solutions, and comprehensive education campaigns.

- The success of the OSHA standard hinges on prioritizing these infrastructure investments to create a comprehensive, well-resourced system for heat safety.

This article is informed by extensive research and stakeholder engagement conducted by the Federation of American Scientists, including a comprehensive literature review and interviews with experts in the field. Much of this work informed our recent publication which can be found here.

The Imperative for Infrastructure Investment