Flying Under The Radar: A Missile Accident in South Asia

A crashed Indian missile inside Pakistani territory. Image: Pakistan Air Force.

With all eyes turned towards Ukraine these past weeks, it was easy to miss what was almost certainly a historical first: a nuclear-armed state accidentally launching a missile at another nuclear-armed state.*

On the evening of March 9th, during what India subsequently called “routine maintenance and inspection,” a missile was accidentally launched into the territory of Pakistan and impacted near the town of Mian Channu, slightly more than 100 kilometers west of the India-Pakistan border.

Because much of the world’s attention has understandably been focused on Eastern Europe, this story is not getting the attention that it deserves. However, it warrants very serious scrutiny––not only due to the bizarre nature of the accident itself, but also because both India’s and Pakistan’s reactions to the incident reveal that crisis stability between South Asia’s two nuclear rivals may be much less stable than previously believed.

The Incident

Using official statements and open-source clues, it is possible to piece together a relatively complete picture of what took place on the evening of March 9th.

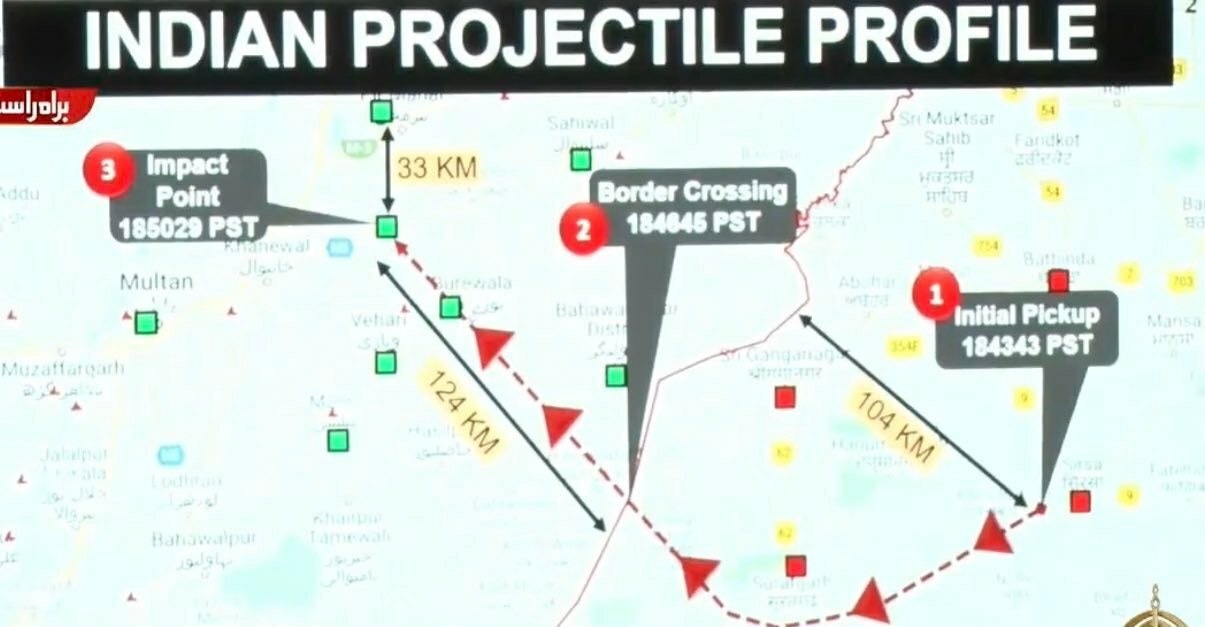

At 18:43:43 Pakistan Standard Time (19:13:43 India Standard Time), the Pakistan Air Force picked up a “high-speed flying object” 104 kilometers inside Indian territory, near Sirsa, in the state of Haryana. According Air Vice Marshal Tariq Zia––the Director General Public Relations for the Pakistan Air Force––the object traveled in a southwesterly direction at a speed between Mach 2.5 and Mach 3. After traveling between 70 and 80 kilometers, the object turned northwest and crossed the India-Pakistan border at 18:46:45 PKT. The object then continued on the same northwesterly trajectory until it crashed near the Pakistani town of Mian Channu at 18:50:29 PKT.

Tweet from @1stIndiaNews indicating that a “tremendous explosion” was heard at approximately 19:15 IST at the city of Sri Ganganagar near the India-Pakistan border. This time and location adds a data point to interpreting the flight path of the missile.

According to Pakistani military officials in a March 10th press conference, 3 minutes and 46 seconds of the object’s total flight time of 6 minutes and 46 seconds were within Pakistani airspace, and the total distance traveled inside of Pakistan was 124 kilometers.

Annotated map of the missile’s flight path provided by Pakistani military officials to media on 10 March 2022.

In a press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that the object was “certainly unarmed” and that no one was injured, although noted that it damaged “civilian property.”

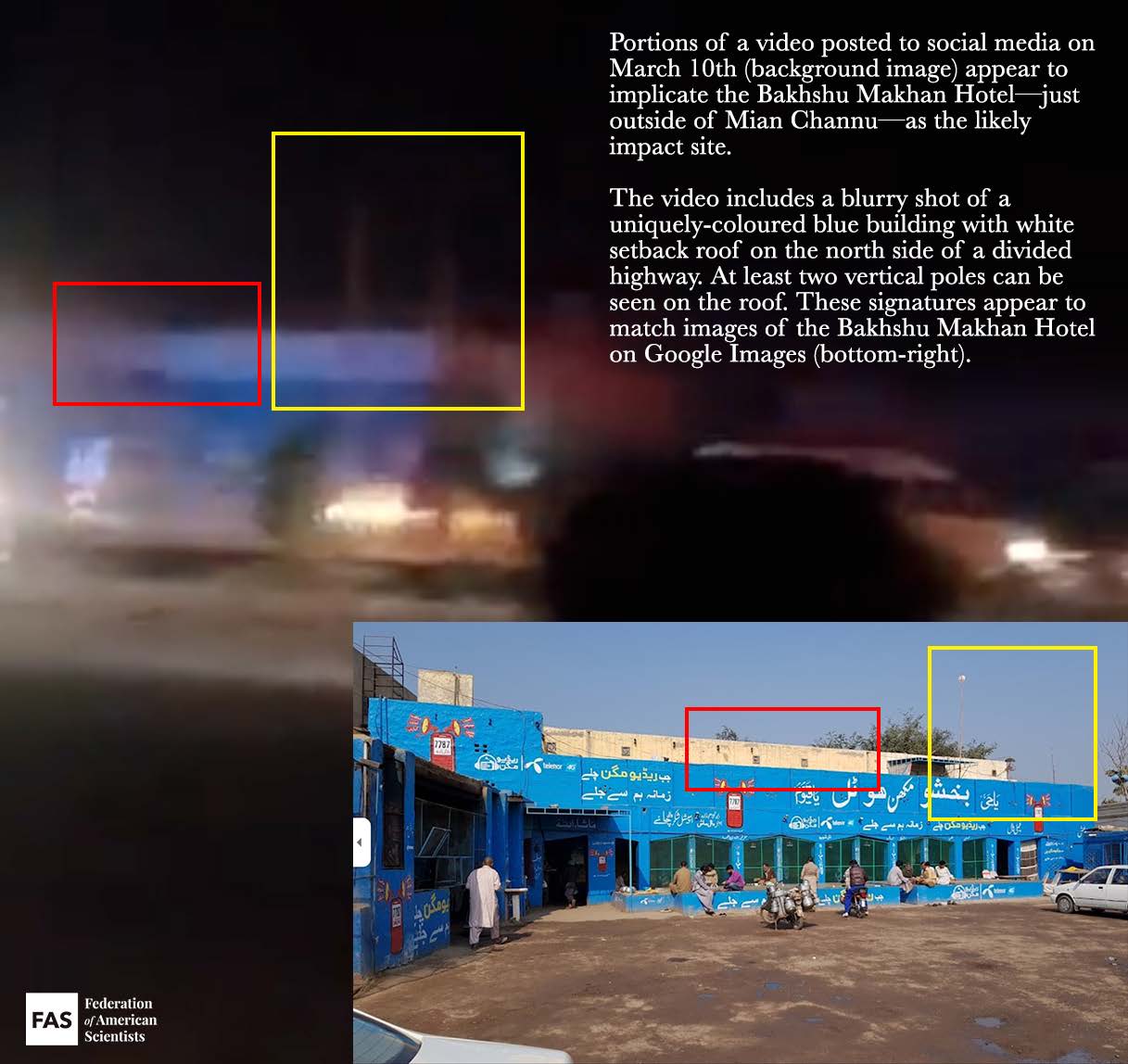

Although the crash site has not been confirmed and official photos include very few useful visual signatures, observation of local civilian social media activity indicates that a likely candidate is the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel, just outside of Mian Channu (30°27’6.40″N, 72°24’10.87″E). One video of the crash site posted to Twitter includes a shot of a uniquely-colored blue building with a white setback roof on the other side of a divided highway. At least two vertical poles can be seen on the roof of the building. All of these signatures appear to match those included in images of the Bakhshu Makhan Hotel in Google Images.

The video’s caption suggests that the object that crashed was an “army aviation aircraft drone;” however, Pakistani military officials subsequently reported that the object was an Indian missile. Neither Pakistan nor India has publicly confirmed what type of missile it was; however, in a March 10th press conference, Pakistani military officials stated that “we can so far deduce that it was a supersonic missile––an unknown missile––and it was launched from the ground, so it was a surface-to-surface missile.”

This statement, in addition to photos of the debris and other official details relating to range, speed, altitude, and flight time of the object, suggest that it was very likely a BrahMos cruise missile.

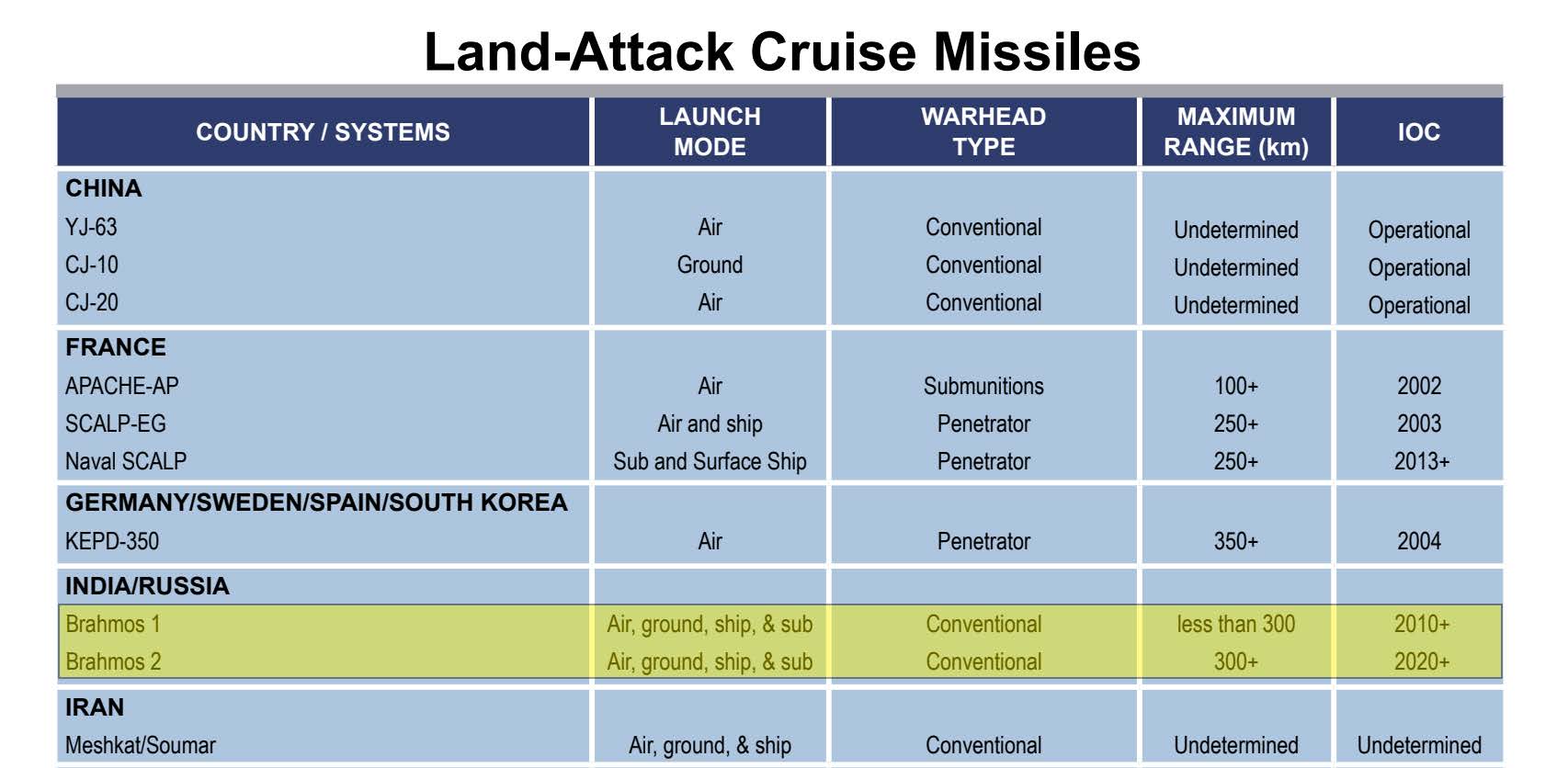

BrahMos is a ramjet-powered, supersonic cruise missile co-developed with Russia, that can be launched from land, sea, and air platforms and can travel at a speed of approximately March 2.8. The US National Air and Space Intelligence Centre (NASIC) suggested that an earlier version of BrahMos had a range of “less than 300” kilometers, but the Indian Ministry of Defence recently announced on 20 January 2022 that it had extended the BrahMos’ range, with defence sources saying that the missile could now travel over 500 kilometres. The reported speed of the “high-speed flying object,” as well as the distance traveled, matches the publicly-known capabilities of the BrahMos cruise missile.

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s 2017 Ballistic and Cruise Missile report lists two versions of the BrahMos missile as “conventional.”

Although many Indian media outlets often describe the BrahMos as a nuclear or dual-capable system, NASIC lists it as “conventional,” and there is no public evidence to indicate that the missile can carry nuclear weapons.

India has launched a Court of Inquiry to determine how the incident occurred; however, the Indian government has otherwise remained tight-lipped on details. In the absence of official statements, small snippets have trickled out through Indian and Pakistani media sources––prompting several questions that still need answers.

How did the missile get “accidentally” launched?

According to the Times of India, an audit was being conducted by the Indian Air Force’s Directorate of Air Staff Inspection at the time of the launch. As part of that audit, or possibly as part of a separate exercise, it appears that target coordinates––including mid-flight waypoints––were fed into the missile’s guidance system. According to Indian defence sources, in order to launch the BrahMos, the missile’s mechanical and software safety locks would also have had to be bypassed and the launch codes would have had to be entered into the system.

The BrahMos does not appear to have a self-destruct mechanism. As a result, once the missile was launched, there was no way to abort.

Given that defence sources indicate that the missile “was certainly not meant to be launched,” it still remains unclear whether the launch was due to human or technical error. On March 11th, in its first public statement about the incident, the Indian government stated that “a technical malfunction led to the accidental firing of a missile.” However, since the formal convening of a Court of Inquiry, the government has since changed its rhetoric, with Indian officials stating that “the accidental firing took place because of human error. That’s what has emerged at this stage of the inquiry. There were possible lapses on the part of a Group Captain and a few others.” Tribute India reports that there are currently four individuals under investigation.

While this is certainly a plausible explanation for the incident, it is also worth noting that the Indian government would be financially incentivized to emphasize the human error narrative over a technical malfunction narrative. On January 28th, India concluded a $374.96 million deal with the Philippines to export the BrahMos––a deal which amounts to the country’s largest defence export contract. Additional BrahMos exports will be crucial for India to meet its ambitious defence export targets by 2025, and the negative publicity associated with a possible BrahMos technical malfunction could significantly hinder that goal.

Did Pakistan track the missile correctly?

In a press conference on March 10th, Pakistani military officials noted that Pakistan’s “actions, response, everything…it was perfect. We detected it on time, and we took care of it.” However, Indian military officials have publicly disputed Pakistan’s interpretation of the missile’s flight path. Pakistan announced on March 10th that the missile was picked up near Sirsa; however, Indian officials subsequently stated that the missile was launched from a location near Ambala Air Force Station, nearly 175 kilometers away. India’s explanation is likely to be more accurate, given that there is no known BrahMos base near Sirsa, but there is one near Ambala (h/t @tinfoil_globe). Indian defence sources have also suggested that the map of the missile’s perceived trajectory that the Pakistani military released on March 10th was incorrect.

Annotated Google Earth image showing the 175 kilometer distance between the likely launch site and Pakistan’s radar pickup.

Furthermore, Pakistani officials announced on March 10th that the missile’s original destination was likely to be the Mahajan Field Firing Range in Rajasthan, before it suddenly turned and headed northwest into Pakistan. However, Indian defence sources have since suggested that the missile was not actually headed for the Mahajan Field Firing Range, but instead was “follow[ing] the trajectory that it would have in case of a conflict, but ‘certain factors’ played a role in ensuring that any pre-fed target was out of danger.” Given that the impact site was not near any critical military or political infrastructure, this could suggest that the cruise missile had its wartime mid-flight trajectory waypoints pre-loaded into the system, but its actual target had not yet been selected. If this is the case, then this targeting practice would be similar in nature to how some other nuclear-armed states target their missiles at the open ocean during peacetime––precisely in case of incidents like this one. Although the missile still landed on Pakistani territory, the fact that it did not hit any critical targets prevented the crisis from escalating. It is worth noting, however, that this would certainly not be the case if the missile had actually injured or killed anyone.

During the March 10th press conference, Pakistani officials noted that the Pakistan Air Force did not attempt to shoot down the missile because “the measures in place in times of war or in times of escalation are different [from those] in peace time.” However, India’s challenges to Pakistan’s narrative also raise significant questions about whether the Pakistan Air Force was able to accurately track the missile correctly. If not, then this raises the possibility of miscalculation or miscommunication, and crisis stability would be seriously eroded if a similar situation occurred during a time of heightened tensions.

Were any civilian aircraft put in danger?

In its public statements, Pakistan has emphasized that the accidental missile launch could have put civilian flights in danger, as India did not issue a Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) prior to launch. Governments typically issue NOTAMs in conjunction with missile tests, in order to inform civilian aircraft to avoid a particular patch of airspace during the launch window. Given that India did not issue one, a time-lapse video prepared by Flightradar24 showed that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch. The video erroneously suggests that the missile traveled in a straight line from Ambala to Mian Channu, when it appears to have dog-legged in mid-flight; however, the video is still a useful resource to demonstrate how crowded the skies were at the time of the accident.

A screenshot of a video prepared by Flightradar24, showing that there were several civilian flights passing very close to the missile’s flight path at the time of launch.

Why was India’s response so poor?

Given the seriousness of the incident, India’s delayed response has been particularly striking. Immediately following the accidental launch, India could have alerted Pakistan using its high-level military hotlines; however, Pakistani officials stated that it did not do so. Additionally, India waited two days after the incident before issuing a short public statement.

India’s poor response to this unprecedented incident has serious implications for crisis stability between the two countries. According to DNA India, in the absence of clarification from India, Pakistan Air Force’s Air Defence Operations Centre immediately suspended all military and civilian aircraft for nearly six hours, and reportedly placed frontline bases and strike aircraft on high alert. Defence sources stated that these bases remained on alert until 13:00 PKT on March 14th. Pakistani officials appeared to confirm this, noting that “whatever procedures were to start, whatever tactical actions had to be taken, they were taken.”

We were very, very lucky

Thankfully, this incident took place during a period of relative peacetime between the two nuclear-armed countries. However, in recent years India and Pakistan have openly engaged in conventional warfare in the context of border skirmishes. In one instance, Pakistani military officials even activated the National Command Authority––the mechanism that directs the country’s nuclear arsenal––as a signal to India. At the time, the spokesperson of the Pakistan Armed Forces not-so-subtly told the media, “I hope you know what the NCA means and what it constitutes.”

If this same accidental launch had taken place during the 2019 Balakot crisis, or a similar incident, India’s actions were woefully deficient and could have propelled the crisis into a very dangerous phase.

Furthermore, as we have written previously, in recent years India’s rocket forces have increasingly worked to “canisterize” their missiles by storing them inside sealed, climate-controlled tubes. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis.

This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

India’s recent missile accident––and the deficient political and military responses from both parties––suggests that regional crisis instability is less stable than previously assumed. To that end, this crisis should provide an opportunity for both India and Pakistan to collaboratively review their communications procedures, in order to ensure that any future accidents prompt diplomatic responses, rather than military ones.

Background Information:

- “Indian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August 2020.

- “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2021,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept/Oct 2021.

- “India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, Dec 2021.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This article was made possible with generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

*[Note: This type of missile accident has apparently happened before; on 11 September 1986, a Soviet missile flew more than 1,500 off-course and landed in China. Thank you to the excellent Stephen Schwartz for the historical reference.]

Categories: Arms Control, ballistic missiles, Deterrence, Disarmament, India, Nuclear Weapons, Pakistan

India’s Nuclear Arsenal Takes A Big Step Forward

On 18 December 2021, India tested its new Agni-P medium-range ballistic missile from its Integrated Test Range on Abdul Kalam Island. This was the second test of the missile, the first test having been conducted in June 2021.

Our friends at Planet Labs PBC managed to capture an image of the Agni-P launcher sitting on the launch pad the day before the test took place.

Following both launches of the Agni-P, the Indian Government referred to the missile as a “new generation” nuclear-capable ballistic missile. Back in 2016, when the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) first announced the development of the Agni-P (which was called the Agni-1P at the time), a senior DRDO official explained why this missile was so special:

“As our ballistic missiles grew in range, our technology grew in sophistication. Now the early, short-range missiles, which incorporate older technologies, will be replaced by missiles with more advanced technologies. Call it backward integration of technology.”

The Agni-P is India’s first shorter-range missile to incorporate technologies now found in the newer Agni-IV and -V ballistic missiles, including more advanced rocket motors, propellants, avionics, and navigation systems.

Most notably, the Agni-P also incorporates a new feature seen on India’s new Agni-V intermediate-range ballistic missiles that has the potential to impact strategic stability: canisterization. And the launcher used in the Agni-P launch appears to have increased mobility. There are also unconfirmed rumors that the Agni-P and Agni-V might have the capability to launch multiple warheads.

Canisterization

“Canisterizing” refers to storing missiles inside a sealed, climate-controlled tube to protect them from the outside elements during transportation. In this configuration, the warhead can be permanently mated with the missile instead of having to be installed prior to launch, which would significantly reduce the amount of time needed to launch nuclear weapons in a crisis. This is a new feature of India’s Strategic Forces Command’s increased emphasis on readiness. In recent years, former senior civilian and military officials have reportedly suggested in interviews that “some portion of India’s nuclear force, particularly those weapons and capabilities designed for use against Pakistan, are now kept at a high state of readiness, capable of being operationalized and released within seconds or minutes in a crisis—not hours, as had been assumed.”

If Indian warheads are increasingly mated to their delivery systems, then it would be harder for an adversary to detect when a crisis is about to rise to the nuclear threshold. With separated warheads and delivery systems, the signals involved with mating the two would be more visible in a crisis, and the process itself would take longer. But widespread canisterization with fully armed missiles would shorten warning time. This would likely cause Pakistan to increase the readiness of its missiles as well and shorten its launch procedures––steps that could increase crisis instability and potentially raise the likelihood of nuclear use in a regional crisis. As Vipin Narang and Christopher Clary noted in a 2019 article for International Security, this development “enables India to possibly release a full counterforce strike with few indications to Pakistan that it was coming (a necessary precondition for success). If Pakistan believed that India had a ‘comprehensive first strike’ strategy and with no indication of when a strike was coming, crisis instability would be amplified significantly.”

For years, it was evident that India’s new Agni-V intermediate-range missile (the Indian Ministry of Defense says Agni-V has a range of up to 5,000 kilometers; the US military says the range is over 5,000 kilometers but not ICBM range) would be canisterized; however, the introduction of the shorter-range, canisterized Agni-P suggests that India ultimately intends to incorporate canisterization technology across its suite of land-based nuclear delivery systems, encompassing both shorter- and longer-range missiles. While Agni-V is a new addition to India’s arsenal, Arni-P might be intended––once it becomes operational––to replace India’s older Agni-I and Agni-II systems.

MIRV technology

It appears that India is also developing technology to potentially deploy multiple warheads on each missile. There is still uncertainty about how advanced this technology is and whether it would enable independent targeting of each warhead (using multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles, or MIRVs) or simply multiple payloads against the same target.

The Agni-P test in June 2021 was rumored to have used two maneuverable decoys to simulate a MIRVed payload, with unnamed Indian defense sources suggesting that a functional MIRV capability will take another two years to develop and flight-test. The Indian MOD press release did not mention payloads. It is unclear whether the December 2021 test utilized decoys in a similar manner.

In 2013, the director-general of DRDO noted in an interview that “Our design activity on the development and production of MIRV is at an advanced stage today. We are designing the MIRVs, we are integrating [them] with Agni IV and Agni V missiles.” In October 2021, the Indian Strategic Forces Command conducted its first user trial of the Agni-V in full operational configuration, which was rumored to have tested MIRV technology. The MOD press release did not mention MIRVs.

If India succeeds in developing an operational MIRV capability for its ballistic missiles, it would be able to strike more targets with fewer missiles, thus potentially exacerbating crisis instability with Pakistan. If either country believed that India could potentially conduct a decapitating or significant first strike against Pakistan, a serious crisis could potentially go nuclear with little advance warning. Indian missiles with MIRVs would become more important targets for an adversary to destroy before they could be launched to reduce the damage India could inflict. Additionally, India’s MIRVs might prompt Indian decision-makers to try and preemptively disarm Pakistan in a crisis.

India’s other nuclear adversary, China, has already developed MIRV capability for some of its long-range missiles and is significantly increasing its nuclear arsenal, which might be a factor in India’s pursuit of MIRV technology. A MIRV race between the two countries would have significant implications for nuclear force levels and regional stability. For India, MIRV capability would allow it to more rapidly increase its nuclear stockpile in the future, if it so decided––especially if its plutonium production capability can make use of the unsafeguarded breeder reactors that are currently under construction.

Implications for India’s nuclear policy

India has long adhered to a nuclear no-first-use (NFU) policy and in 2020 India officially stated that there has been no change in its NFU policy. Moreover, the Agni-V test launch in October 2021 was accompanied by a reaffirmation of a “’credible minimum deterrence’ that underpins the commitment to ‘No First Use’.”

At the same time, however, the pledge to NFU has been caveated, watered-down, and called into question by government statements and recent scholarship. The increased readiness and pursuit of MIRV capability for India’s strategic forces could further complicate India’s adherence to its NFU policy and could potentially cause India’s nuclear adversaries to doubt its NFU policy altogether.

Given that Indian security forces have repeatedly clashed with both Pakistani and Chinese troops during recent border disputes, potentially destabilizing developments in India’s nuclear arsenal should concern all those who want to keep regional tensions below boiling point.

Background Information:

- “Indian Nuclear Forces, 2020,” FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, July/August 2020.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, Federation of American Scientists

This article was made possible by generous support from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

What Is the Sole Purpose of U.S. Nuclear Weapons?

Summary

- Prior to assuming office, President Biden indicated that he would establish that “the sole purpose of our nuclear arsenal is to deter—and, if necessary, retaliate for—a nuclear attack against the United States and its allies.”

- Sole purpose should be understood as a central component of an integrated deterrence strategy that can effectively manage the risk of nuclear escalation in a limited conflict as well as the rising stability risks from nonnuclear weapons.

- Sole purpose could significantly reduce the risk of unintended escalation and increase the credibility of more flexible and realistic nonnuclear response options in a range of importance contingencies.

- In order to attain its intended benefits, declaratory policy must be reflected in force structure and planning.

- The president’s existing language on sole purpose provides considerable flexibility for the administration to define the doctrine, but does not itself provide clear guidance for strategy, force structure, or for related declaratory policies like “no first use.”

- Defining sole purpose is a critical task for the administration’s defense policy review.

- As a central component of an integrated defense policy that will strengthen US deterrence and assurance credibility, sole purpose should be defined at the level of the NDS.

- A sole type definition would state that the United States would consider nuclear use in response to a certain type of attack, having modest effects on a narrow set of plans but few effects on force structure.

- A sole function definition would define what is and what is not a requirement of deterrence, potentially removing certain strategic or nonstrategic roles of nuclear weapons.

Depending on how it is defined, sole purpose could have transformational effects on nearly every aspect of nuclear weapons policy or relatively modest effects. It could accommodate or incorporate a range of related policy options, like a deterrence-only posture or no first use.

- Fully implementing a sole purpose policy is critical to attaining its benefits.

- A simple declaratory statement is not a complete sole purpose policy. Because any statement is likely to be ambiguous, sole purpose should also consist of a set of presidential directives that determine how the policy will be affect force structure and planning.

- By eliminating one or more of the requirements that structure US nuclear forces, a sole function definition could potentially have significant effects on a range acquisition decisions and plans.

- If the president concludes that sole purpose has implications for force structure or force posture, the administration should ensure that these changes are made before the presidential term is concluded.

- Following a decision to adopt sole purpose, civilian officials should review existing operational plans and concepts to ensure that they comport with the president’s guidance for escalation management of a conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary.

- Embedding the policy in plans, force structure, and allied consultations is critical to achieving its benefits and reducing the risk that it is reversed by a future president, which would be highly risky.

- If defined, implemented, and communicated as a part of an effective integrated deterrence posture, sole purpose could strengthen assurance of allies.

- Some allies will be understandably apprehensive about any shift in US nuclear weapons policy in the current environment.

- Allies should be consulted closely as sole purpose is being defined, as it is released, and as it is being implemented.

In January 2021, President Biden assumed office after having made unusually explicit commitments to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in US national security strategy. In his primary articulation of his campaign’s foreign policy, BJoseph R. Biden, “Why American Must Lead Again: Rescuing US Foreign Policy after Trump,” Foreign Affairs 99 (2020): 64.iden declared that “the sole purpose of the US nuclear arsenal should be deterring—and if necessary, retaliating against—a nuclear attack.”1 Since assuming office, Biden has not repeated the pledge, though his initial national security guidance and his Secretary of State have reiterated the goal of reducing reliance on nuclear weapons.2 As the Pentagon begins its review of nuclear weapons policy, Biden and his national security officials will have to determine whether to adopt sole purpose and, if so, what it means. The established language on sole purpose offers the administration considerable latitude in how it chooses to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, it could have transformative consequences for nuclear force structure and strategy, or it could end up as a rhetorical commitment that has few practical effects at all.

Though the language dates back decades, there has never been a precise or agreed definition of sole purpose. The first published use of the phrase is in a piece Albert Einstein related to the eminent journalist Raymond Swing that was published in the Atlantic in 1947. Einstein argued while the United States must stockpile the bomb, it should forswear its use. “Deterrence should be the only purpose of the stockpile of bombs.” If the United Nations were granted international control over atomic energy, as President Truman had proposed, it should be “for the sole purpose of deterring an aggressor or rebellious nations from making an atomic attack.3 Since the idea was popularized in the 1960s, sole purpose has become a persistent staple in ongoing debates about the role of nuclear weapons, but it has rarely been attached to a precise definition or a plan to implement it.

Sole purpose is more ambiguous than other declaratory policy proposals (such as no first use) because it purports to define, or constrain, the purpose of nuclear weapons. Depending on how the terms of the statement are defined and how the statement is implemented in practice, its effects could be broad, narrow, restrictive, permissive, or ambiguous. For example, President Biden’s sole purpose language could be construed to proscribe nuclear weapons from performing a wide range of functions or from being used in wide ranges of contingencies. Slight variations in the wording of a sole purpose declaration can produce dramatically different policies and be perceived differently by allies and adversaries, who will examine the policy closely. Depending on how sole purpose is defined and implemented, sole could reduce or eliminate requirements for each piece of the triad or for nuclear use in a variety of different contingency plans.

Sole purpose is one potential option in declaratory policy, that aspect of nuclear weapons policy that publicly communicates when and why the United States would consider the use of nuclear weapons. It can be combined with or can subsume a range of other potential declaratory policy options. Because the president has sole authority to order the use of a nuclear weapon, only the president can set limits on that power. Though changes in declaratory policy should consider the views of civilian national security officials, uniformed military officials, members of Congress, US allies, and the American public, the president should provide clear guidance on how to modify US declaratory policy. Like all presidents, President Biden should provide clear guidance to the officials conducting the national defense strategy about nuclear declaratory policy.

Because sole purpose could potentially be defined in many different ways, some definitions will be better or worse. Advocates or opponents should be clear about what constitutes a better or worse definition. The administration should not accept the argument that a good definition is one that preserves existing force structure or plans, maintains ambiguity for its own sake, or comports with the preferences of certain allies or services. This piece argues that a good definition of sole purpose is one that assists with the development and implementation of a credible, integrated posture by which the United States and its allies deter aggression and nuclear use; reflects the president’s preferences about how to manage escalation in limited conflicts with nuclear-armed adversaries as well as his assessment of the requirements of deterring a major strategic attack; reduces the risk of misperception and adversary nuclear first use incentives; and can be implemented in force structure and plans so that it is resilient to leadership changes in the United States. Because the president has expressed a preference to reduce the nation’s reliance on nuclear weapons, a good definition of sole purpose should help to do so in ways consistent with his preferences.

This piece examines the range of options available to officials working to define sole purpose and reduce reliance on nuclear weapons. It explores the practical implications of different definitions of sole purpose and the steps necessary to ensure that they are implemented in a way that is responsible, effective, and most likely to endure over time. There are two central arguments. First, sole purpose should not be understood as a nuclear declaratory policy but as critical component in an integrated deterrence strategy. Understood in this way, sole purpose is not only a valuable means of reducing the risk of nuclear escalation and of meeting US commitments to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons but because it is a substantive judgment about how US nuclear and nonnuclear forces can best manage escalation in a limited conflict with a nuclear-armed adversary. Second, an effective sole purpose policy cannot simply be a sentence in a paragraph on nuclear declaratory policy. If the administration is serious about attaining the benefits of sole purpose, the policy should be comprised of the declaratory statement, additional language to clarify and contextualize the policy, and a set of directives that communicate the president’s guidance for how the policy should affect force structure and plans.

Each of these arguments is critical for attaining the benefits of sole purpose and for maintaining an effective deterrence posture. Sole purpose will be a contentious idea under any circumstances. Allied governments, advocates of various aspects of the current nuclear weapons policies, and political opponents are understandably concerned about the president’s statements. Clearly defining the policy, articulating how it will strengthen an integrated deterrence policy, and moving forward with implementation will help to convince allies and many deterrence experts that sole purpose will increase rather than decrease deterrence credibility.

Increasing Nuclear Bomber Operations

CBS’s 60 Minutes program Risk of Nuclear Attack Rises described that Russia may be lowering the threshold for when it would use nuclear weapons, and showed how U.S. nuclear bombers have started flying missions they haven’t flown since the Cold War: Over the North Pole and deep into Northern Europe to send a warning to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The program follows last week’s program The New Cold War where viewers were shown unprecedented footage from STRATCOM’s command center at Omaha Air Base in Nebraska.

Producer Mary Welch and correspondent David Martin have produced a fascinating and vital piece of investigative journalism showing disturbing new developments in the nuclear relationship between Russia and the United States.

They were generous enough to consult me and include me in the program to discuss the increasing Cold War and dangerous military posturing.

Nuclear Bomber Operations Context

Just a few years ago, U.S. nuclear bombers didn’t spend much time in Europe. They were focused on operations in the Middle East, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Despite several years of souring relations and mounting evidence that the “reset” with Russia had failed or certainly not taken off, NATO couldn’t make itself say in public that Russia gradually was becoming an adversary once again.

Whatever hesitation was left changed in March 2014 when Vladimir Putin sent his troops to invade Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The act followed years of Russian efforts to coerce the Baltic States, growing and increasingly aggressive military operations around European countries, and explicit nuclear threats against NATO countries getting involved in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

Granted, NATO may not have been a benign neighbor, with massive expansion eastward of new members all the way up to the Russian border, and a consistent tendency to ignore or dismiss Russian concerns about its security interests.

But whatever else Putin might have thought he would gain from his acts, they have awoken NATO from its detour in Afghanistan and refocused the Alliance on its traditional mission: defense of NATO territory against Russian aggression. As a result, Putin will now get more NATO troops along his western and southern borders, larger and more focused military exercises more frequently in the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, increasing or refocused defense spending in NATO, and a revitalization of a near-slumbering nuclear mission in Europe.

Six years ago the United States was this close to pulling its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons out of Europe. Only an engrained NATO nuclear bureaucracy aided by the Obama administration’s lack of leadership prevented the withdrawal of the weapons. Russia has complained about them for years but now it seems very unlikely that the modernization of the F-35A with the B61-12 guided bomb can be stopped. The weapons might even get a more explicit role against Russia, although this is still a controversial issue for some NATO members.

But the U.S. military would much prefer to base the nuclear portion of its extended deterrence mission in Europe on strategic bombers rather than the short-range fighter-bombers forward deployed there. The non-strategic nuclear weapons are far too controversial and vulnerable to the myriads of political views in the host countries. Strategic bombers are free of such constraints.

A New STRATCOM-EUCOM Link

Therefore, even before NATO at the Warsaw Summit this summer decided to reinvigorate its commitment to nuclear deterrence, former U.S. European Command (EUCOM) commander General Philip Breedlove told Congress in February 2015, EUCOM had already “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence [BAAD] missions to NATO regional exercises” as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve to deter Russia.

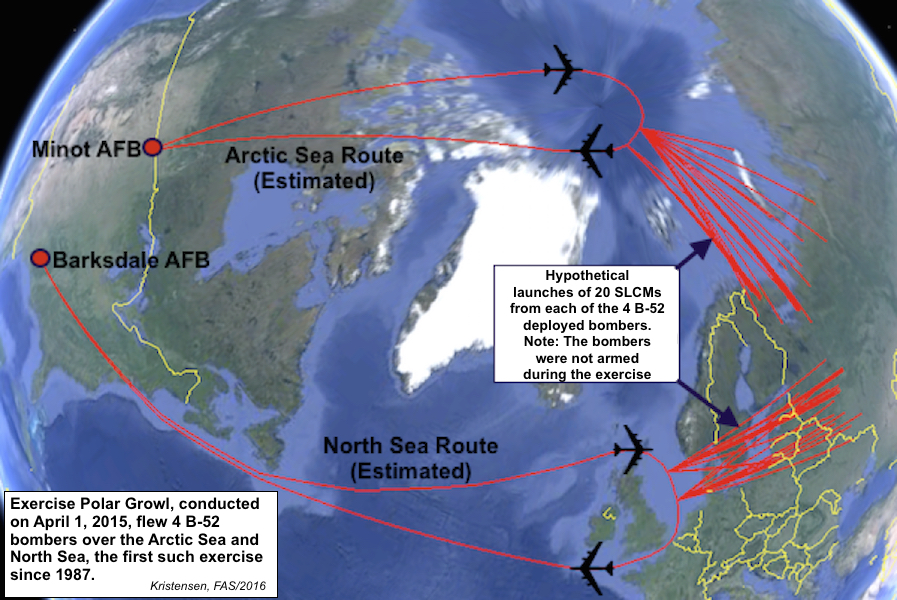

Less than two months later, on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took of from their bases in the United States and flew across the North Pole and North Sea in a simulated strike exercise against Russia. The bombers proceeded all the way to their potential launch points for air-launched cruise missiles before they returned to the United States. Such an exercise had not been conducted since the late-1980s against the Soviet Union. Combined, the four bombers could have delivered 80 long-range nuclear cruise missiles with a combined explosive power of 800 Hiroshima bombs.

During Exercise Polar Growl on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers flew along two routes into the Arctic and North Sea regions that appeared to simulate long-range strikes against Russia. The four bombers were capable of launching up to 80 nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a combined explosive power equivalent to 800 Hiroshima bombs. All routes are approximate.

Despite its strategic implications, Polar Growl also had a distinctive regional – even limited – objective because of the crisis in Europe. Planning for such regional deterrence scenarios have taken on a new importance during the past couple of decades and they have become central to current planning because it is in such regional scenarios that the United States believes it is most likely that nuclear weapons could actually be used.

“The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, in 2014 predicted only a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, “and continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.”

Two weeks after the bombers returned from Polar Growl, Robert Scher, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities, told Congress: “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts.” This includes “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

Nuclear Conventional Integration

Much of this increased planning involves conventional weapons such as the new long-range conventional JASSM-ER cruise missile, but the planning also involves nuclear. In fact, conventional and nuclear appear to be integrating in a way they have done before. This effort was described recently by Brian McKeon, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, during the annual STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium:

In the Department of Defense we’re working to effectively integrate conventional and nuclear planning and operations. Integration is not new but we’re renewing our focus on it because of recent developments and how we see potential adversaries preparing for conflict. This is an area where the focus in Omaha has really led the way and I want to commend Admiral Haney and STRATCOM for being able to shift planning so quickly toward this approach and thinking though conflict. No one wants to think about using nuclear weapons and we all know the principle role of nuclear weapons is to deter their use by others. But as we’ve seen, out adversaries may not hold the same view.

Let me be clear that when I say integration I do not mean to say we have lowered the threshold for nuclear use or would turn to nuclear weapons sooner in a conventional campaign. As we stated in the Nuclear Posture Review, the United States will “only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.” The NPR also emphasized the importance of reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, a requirement that has been advanced in our planning consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance, including with non-nuclear strike options.

What I mean by integration is synchronizing our thinking across all domains in a way that maximizes the credibility and flexibility of our deterrent through all phases of conflict and responds appropriately to asymmetrical escalation. For too long, crossing the nuclear threshold was through to move a nuclear conflict out of the conventional dimension and wholly into the nuclear realm. Potential adversaries are exploring ways to cross this threshold with low-yield nuclear weapons to test out resolve, capabilities, and Allied cohesion. We must demonstrate that such a strategy cannot succeed so that it is never attempted. To that end we’re planning and exercising our non-nuclear operations conscious of how they might influence an adversary’s decision to go nuclear.

We also plan for the possibility of ongoing U.S. and Allied operations in a nuclear environment and working to strengthen resiliency of conventional operations to nuclear attack. By making sure our forces are capable of continuing the fight following a limited nuclear use we preserve flexibility for the president. And by explicitly preparing for the implication of an adversary’s limited nuclear use and providing credible options for the President, we strengthen our deterrent and reduce the risk of employment in the first instance.

Regional nuclear scenarios no longer primarily involve planning against what the Bush administration called “rogue states” such as North Korea and Iran, but increasingly focus on near-peer adversaries (China) and peer adversaries (Russia). “We are working as part of the NATO alliance very carefully both on the conventional side as well as meeting as part of the NPG [Nuclear Planning Group] looking at what NATO should be doing in response to the Russian violation of the INF Treaty,” Scher explained.

STRATCOM last updated the strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) in 2012 and is currently about to publish an updated version that incorporates the changes caused by the Obama administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy from 2013.

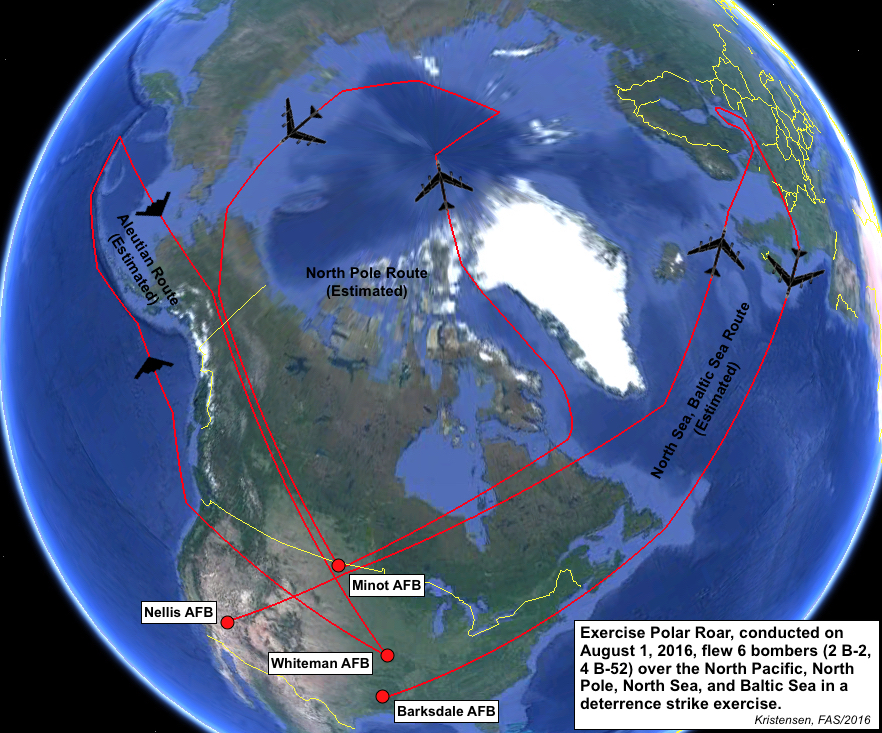

Two months ago, a little over a year after Polar Growl, another bomber strike exercise was launched. This time six bombers (4 B-52s and 2 B-2s) flew closer to Russia and simultaneously over the Arctic Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and North Pacific Ocean. The six Polar Roar sorties required refueling support from 24 KC-135 tankers as well as E4-B Advanced Airborne Command Post and E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft.

The routes (see below) were eerily similar to the Chrome Dome airborne alert routes that were flown by nuclear-armed bombers in the 1960s against the Soviet Union.

Exercise Polar Roar on August 1, 2016, followed Exercise Polar Growl from 2015 but involved more bombers, both nuclear-capable and conventional-only, and flew closer to Russia and deep into the Baltic Sea. Polar Roar also included B-2 stealth bombers in the North Pacific. All routes are approximate.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.