Federation of American Scientists (FAS) Celebrates 2nd Anniversary of the Inflation Reduction Act

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is the largest climate investment in history. FAS scientists offer policy ideas to maximize the impacts of this investment on U.S. competitiveness, energy security, resilience, and more.

Washington, D.C. – August 16, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS), the non-partisan, nonprofit science think tank dedicated to using evidence-based science for the public good, is celebrating the two-year anniversary of the signing of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) by sharing policy ideas to drive continued successful implementation of this landmark legislation.

The IRA is a United States federal law which aims to reduce the federal government budget deficit, lower prescription drug prices, and invest in domestic energy production while promoting clean energy. It was passed by the 117th United States Congress and it was signed into law by President Biden on August 16, 2022. The IRA has catalyzed $265 billion in new clean energy investments and created hundreds of thousands of jobs in the United States, putting us on a path to achieving climate goals while boosting the economy.

“In just two years, the Inflation Reduction Act has driven down costs of energy and transportation for everyday Americans while reining in catastrophic climate change” says Hannah Safford, Associate Director of Climate and Environment. “This legislation proves that when we invest in a better future, everyone wins.”

“The IRA enables the country to move toward ambitious climate goals. We already see the effects with new policy proposal ideas that could supercharge pursuit of these goals,” says Kelly Fleming, Associate Director of Clean Energy. “The Department of Energy finds that with the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, we can double the share of clean electricity generation to 80% in 2030.”

FAS, one of the country’s oldest science policy organizations, works with scientists and technologists to propose policy-ready ideas to address current and emerging threats, including climate change and energy insecurity.

On today’s two-year anniversary of the IRA, FAS is highlighting policy proposals that build on the IRA’s successes to date and suggest opportunities for continued impact. Examples include:

Geothermal

Geothermal technologies became eligible for tax credits under IRA.

Breaking Ground on Next-Generation Geothermal Energy The Department of Energy (DOE) could take a number of different approaches to accelerating progress in next-generation geothermal energy, from leasing agency land for project development to providing milestone payments for the costly drilling phases of development.

Low-Carbon Cement

The IRA provides $4.5B to support government procurement of low-carbon versions of this cornerstone material.

Laying the Foundation for the Low-Carbon Cement and Concrete Industry Cement and concrete production is one of the hardest industries to decarbonize. Using its Other Transactions Authority, DOE could design a demand-support program involving double-sided auctions, contracts for difference, or price and volume.

Critical Minerals and Energy Manufacturing

Supply chains necessary for battery technologies are being built out in the U.S. thanks to IRA incentives. The new Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chain Office (MESC) has implemented and unveiled programs to retool existing facilities for EV manufacturing, and rehire existing work, and provide tax incentives for clean energy manufacturing facilities with funding provided in the IRA. The office supports the development and deployment of a domestic clean energy supply chain, including for critical minerals needed for batteries and other advanced technologies.

Critical Thinking on Critical Minerals: How the U.S. Government Can Support the Development of Domestic Production Capacity for the Battery Supply Chain Batteries for electric vehicles, in particular, will require the U.S. to consume an order of magnitude more lithium, nickel, cobalt, and graphite than it currently consumes.

Nature Based Solutions

Billions of dollars have been invested into nature based solutions, including $1 billion in urban forestry, that will make communities more resilient to climate change.

A National Framework For Sustainable Urban Forestry To Combat Extreme Heat. To realize the full benefits of the federal government’s investment in urban forestry, there will need to be a coordinated, equity-focused, and economically validated federal plan to guide the development and maintenance of urban forestry that will allow the full utilization of this critical resource.

Submit Your Science and Technology Policy Ideas

The IRA is one lever to make real-world change; good ideas can come from anyone, including you.

FAS is soliciting federal policy ideas to present to the next U.S. presidential administration through the Day One 2025 project, which closes soon. Interested parties can submit science and technology related policy ideas year-round at FAS’s Day One website page.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) Applauds the Newly Announced Board Selected to Lead the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI)

FAS eager to see the Board set an ambitious agenda that aligns with the potential scale of FESI’s impact

Washington, D.C. – May 9, 2024 – Earlier today Secretary of Energy Granholm took the first official step to stand up the Department of Energy-affiliated non-profit Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) by appointing its inaugural board. Today the “Friends of FESI” Initiative of the nonpartisan, non-profit Federation of American Scientists (FAS) steps forward to applaud the Secretary, congratulate the new board members, and wish FESI well as it officially begins its first year. The Inaugural FESI Board consists of 13 accomplished members whose backgrounds span the nation’s regions and communities and who have deep experience in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors. It includes:

- Jason Walsh, BlueGreen Alliance

- Nancy Pfund, DBL Partners

- Rita Baranwal, Westinghouse Electric

- Vicky Bailey, Anderson Stratton

- Mike Boots, Breakthrough Energy

- Miranda Ballentine, Clean Energy

- Stephen Pearse, Yucatan Rock

- Noel Bakhtian, Bezos Earth Fund

- Mung Chiang, President of Purdue University

- Noelle Laing, Builder’s Initiative Foundation

- Katie McGinty, Johnson Controls

- Tomeka McLeod, Hydrogen VP at bp

- Rudy Wynter, National Grid NY

Since the CHIPS and Science Act authorized FESI in 2022, FAS, along with many allies and supporters who collectively comprise the “Friends of FESI,” have been working to enable FESI to achieve its full potential as a major contributor to the achievement of DOE’s vital goals. “Friends of FESI” has been seeking projects and activities that the foundation could take on that would advance the DOE mission through collaboration with private sector and philanthropic partners.

“FAS enthusiastically celebrates this FESI milestone because, as one of the country’s oldest science and technology-focused public interest organizations, we recognize the scale of the energy transition challenge and the urgency to broker new collaborations and models to move new energy technology from lab to market,” says Dan Correa, CEO of FAS. “As a ‘Friend of FESI’ FAS continues our outreach amongst our diverse network of experts to surface the best ideas for FESI to consider implementing.” The federation is soliciting ideas at fas.org/fesi, underway since FESI’s authorization.

FESI has great potential to foster the public-private partnerships necessary to accelerate the innovation and commercialization of technologies that will power the transition to clean energy. Gathering this diverse group of accomplished board members is the first step. The next is for the FESI Board to pursue projects set to make real impact. Given FESI’s bipartisan support in the CHIPS & Science Act, FAS hopes the board is joined by Congress, industry leaders and others to continue to support FESI in its initial years.

“FESI’s establishment is a vital initial step, but its value will depend on what happens next,” says David M. Hart, a professor at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and leader of the “Friends of FESI” initiative at FAS. “FESI’s new Board of Directors should take immediate actions that have immediate impact, but more importantly, put the foundation on a path to expand that impact exponentially in the coming years. That means thinking big from the start, identifying unique high-leverage opportunities, and systematically building the capacity to realize them.”

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Resources

Building a Firm Foundation for the DOE Foundation: It All Starts with a Solid Board

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-board-launch/

FAS use case criteria:

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-priority-use-cases/

FAS open call for FESI ideas:

https://fas.org/publication/share-an-idea-for-what-fesi-can-do-to-advance-does-mission/

DOE announcing FESI board:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-appoints-inaugural-board-directors-groundbreaking-new-foundation

DOE release announcing FESI:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-launches-foundation-energy-security-and-innovation

Climate Change Challenges and Solutions in Forestry & Agriculture

Climate change is already impacting agriculture and forestry production in the U.S. However, these sectors also hold the key to adaptation and mitigation. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is at the forefront of addressing these challenges and developing solutions. Understanding the implications of climate change in agriculture and forestry is crucial for our nation to forge ahead with effective strategies and outcomes, ensuring our food and shelter resources remain secure.

Currently, the atmosphere contains more key greenhouse gasses (nitrous oxides, carbon dioxide, methane) than ever in history thanks to human activities. Industrial, agricultural, and deforestation practices add to the abundance of these critical gasses that are warming our planet. This has become more noticeable through more frequent severe weather and natural disasters with record heat waves, droughts, tornadoes, and rainfall. In 2023, global climate records of temperatures were broken and hit the highest in the last 174 years. Ocean temperatures are reaching record levels, along with major melts in ice sheets. All these changes will affect forestry and agriculture in profound ways. Crop damaging insects and diseases, along with other stresses caused by extreme changes, will also have cascading effects.

Adjustments or adaptations in response to climate change have progressed globally, with planning and implementation across multiple sectors and regions. While much attention is being paid to reforestation and reducing deforestation, gaps still exist and will need continued attention and financial input to address current and future challenges. Agriculture and forestry are two sectors worth exploring as they can open up climate adaptation and mitigation solutions that have positive cascading benefits across regions.

Challenges in the Agriculture and Forestry Sector

Agriculture contributes to greenhouse gas emissions through several activities, such as burning crop residues, soil management and fertilization, animal manure management, and rice cultivation. In addition, agriculture requires significant amounts of energy for vehicles, tractors, harvest, and irrigation equipment. Agriculture involves complex systems that include inputs of fertilizers and chemicals, management decisions, social factors, and interactions between climate and soil.

Most agriculture operations need fertilizers to produce goods, but the management and specific use of fertilizers need further focus. According to the Inventory of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, agriculture contributes 9.4% of total greenhouse gas emissions in the United States.

Agriculture is particularly vulnerable to climate change because many operations are exposed to climatic changes in the natural landscape. There has been widespread economic damage in agriculture due to climate change. Individuals and farms have been affected by flooding, tornadoes, extreme wildfires, droughts, and excessive rains. Loss of property and income, human health, and food security is real for agriculture producers. Adverse impacts will continue to be felt in agricultural systems, particularly in crop production, water availability, animal health, and pests and diseases.

Forestry is a major industry in the U.S. and plays a key role in regulating the climate by transferring carbon within ecosystems and the atmosphere.. Forests remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere and store it in trees and soils. Forestry has seen a decline in the last few decades due to development and cropland expansion. The decline in forestry acres affects essential services such as air purification, regulating water quantity and quality, wood products for shelter, outdoor recreation, medicines, and wildlife habitat. Many Indigenous people and Tribal Nations depend on forest ecosystems for food, timber, culture, and traditions. Effective forest management is crucial for human well-being and is influenced by social and economic factors.

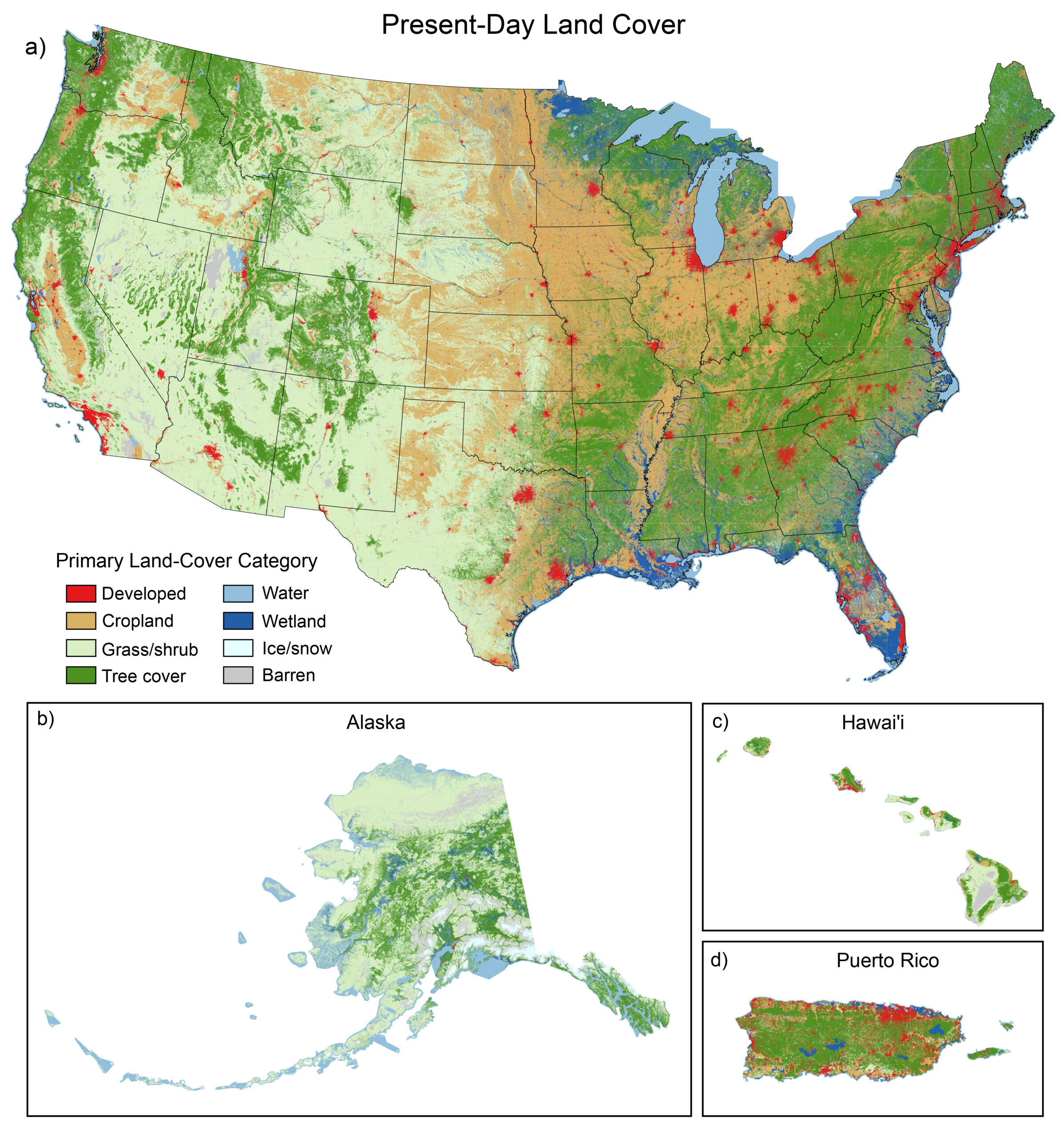

Land cover types and distribution of the United States. Forest lands have decreased in the last two decades. (Source: Fifth National Climate Assessment)

Forests are affected by climate change on local or regional levels based on climate conditions such as rainfall and temperature. The West has been significantly affected, with higher temperatures and drought leading to more wildfires. Higher temperatures come with higher evaporation rates, leading to drier forests that are susceptible to fires. The greater amount of dry wood causes extensive fires that burn more intensely. Fire activity is projected to increase with further warming and less rain. Since 1990, these extensive fires have produced greater greenhouse gas emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2). Other regions of the country with forests that typically receive more rain, like the southeast and northeast, are challenging to predict fire hazards. Other climate change effects include insects, diseases, and invasive species, which change forest ecosystems’ growth, death, and regeneration. Various degrees of disruption can impact a forest’s dynamics.

Current Adaptation Approaches in Agriculture and Forestry

Since agriculture’s largest contribution to greenhouse gas emissions is agriculture soil management, emphasis is being placed on reducing emissions from this process. Farmers are tilling less and using cover crops to keep the ground covered, which helps soils perform the important function of carbon storage. These techniques can also help lower soil temperatures and conserve moisture. In addition, those working in the agriculture sector are taking measures to adapt to the changing climate by developing crops that can withstand higher temperatures and water stress. Ecosystem-based solutions such as wetland restoration to reduce flooding have also been effective. Another potential solution is agroforestry, in which trees are planted, and other agricultural products are grown between the trees or livestock is grazed within a forestry system. This system provides shade to the animals and enhances biodiversity. It protects water bodies by keeping the soil covered with vegetation throughout the year. The perennial vegetation also stores carbon in above-ground vegetation and below-ground roots.

In the forestry space, land managers and owners are developing plans to adapt to climate challenges by building adaptations in key areas such as relationships and connections of land stewardship, research teamwork, and education curriculum. Several guides, assessments, and frameworks have been designed to help private forest owners, Tribal lands, and federally managed forests. Tribal adaptation plans also include Tribal values and cultural considerations for forests. The coasts will be adapting to more frequent flooding, and relocation of recreation areas in vulnerable areas is being planned. In major forestry production areas in the West, forestry agencies are developing plans for prescribed burning to keep dead wood lower, eliminate invasive species, and enable fire-adapted ecosystems to thrive, all while reducing severe wildfires. Thinning forests and fuel removal also help with reducing wildfire risk.

While both sectors have made progress in quickly adjusting their practices, much more needs to be done to ensure that land managers and affected communities are better prepared for both the short-term and long-term effects of climate change. The federal government, through USDA, can drive adaptation efforts to help these communities.

Current Policy

The USDA created the Climate Adaptation and Resilience Plan in response to Executive Order 14008, Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, which requires all federal agencies to develop climate adaptation plans in all public service aspects, including management, operations, missions, and programs.

The adaptation plan focuses on key threats to agriculture and forestry, such as:

- Outreach and education to promote the adoption and application of climate-smart strategies;

- Investments in soil and forest health to build resilience across landscapes;

- Building access to climate data at regional and local scales for USDA and stakeholders and leveraging USDA Climate Hubs to support USDA in delivering adaptation science, technology, and tools; and

- Increasing support and research for climate-smart practices and technologies to help producers and land managers.

Many USDA agencies have developed actions to address the impacts of climate change in different mission areas of USDA. These adaptation plans provide information for farmers, ranchers, forest owners, rural communities, trade and foreign affairs on ways to address the impact of climate change that affects them the most. For example, farm and ranch managers can use COMET Farm, a user-friendly online tool co-developed by Colorado State University and USDA that helps compare land management practices and account for carbon and greenhouse gas emissions.

USDA has invested $3.1 billion in Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities, encompassing 141 projects that involve small and underserved producers. The diverse projects are matched financially with non-federal funds and include over 20 tribal projects, 100 universities, including 30 minority-serving institutions, and others. The goals of the federal and private sector funding include:

- Developing markets and promote climate-smart commodities;

- Piloting cost-effective and innovative methods for understanding, monitoring, and reporting greenhouse gas emissions; and

- Providing technical and financial assistance to producers to implement climate-smart production practices such as reduced tillage and cover crops.

The USDA Forest Service has also developed its own Climate Adaptation Plan that comprehensively incorporates climate adaptation into its mission and operations. The Forest Service has cultivated partnerships with the Northwest Climate Hub, National Park Service, Bureau of Land Management, University of Washington, and the Climate Impacts Group to develop tools and data to help with decision-making, evaluations, and developing plans for implementation. One notable example is the Sustainability and Climate website, which provides information on adaptation, vulnerability assessments, carbon, and other aspects of land management.

Conclusion

While sustained government incentives can help drive adaptation efforts, it is important for everyone to play a role in adapting to climate change, especially in the agriculture and forestry sectors. Purchasing products that are grown sustainably and in climate-smart ways will help protect natural resources and support these communities. Understanding the significance of resilience against climate changes and disruptions is crucial, both in the short and long term. These challenges require collaborators to work together to creatively solve problems in addressing greenhouse gas contributions. Climate models can help solve complex problems and test different scenarios and solutions. As the Fifth National Climate Assessment of the United States notes, greenhouse gas concentrations are increasing, global warming is on the rise, and climate change is currently happening. The choices we make now can have a significant impact on our future.

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.

Enhancing Public Health Preparedness for Climate Change-Related Health Impacts

The escalating frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, exacerbated by climate change, pose a significant and growing threat to public health. This problem is further compounded by the lack of standardized education and preparedness measures within the healthcare system, creating a critical gap in addressing the health impacts of extreme heat. The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), especially the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), and the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) can enhance public health preparedness for the health impacts of climate change. By leveraging funding mechanisms, incentives, and requirements, HHS can strengthen health system preparedness, improve health provider knowledge, and optimize emergency response capabilities.

By focusing on interagency collaboration and medical education enhancement, strategic measures within HHS, the healthcare system can strengthen its resilience against the health impacts of extreme heat events. This will not only improve coding accuracy, but also enhance healthcare provider knowledge, streamline emergency response efforts, and ultimately mitigate the health disparities arising from climate change-induced extreme heat events. Key recommendations include: establishing dedicated grant programs and incentivizing climate-competent healthcare providers; integrating climate-resilience metrics into quality measurement programs; leveraging the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act to enhance ICD-10 coding education; and collaborating with other federal agencies such as the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the Department of Defense (DoD) to ensure a coordinated response. The implementation of these recommendations will not only address the evolving health impacts of climate change but also promote a more resilient and prepared healthcare system for the future.

Challenge

The escalating frequency and intensity of extreme heat events, exacerbated by climate change, pose a significant and growing threat to public health. The scientific consensus, as documented by reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the National Climate Assessment, reveals that vulnerable populations, such as children, pregnant people, the elderly, and marginalized communities including people of color and Indigenous populations, experience disproportionately higher rates of heat-related illnesses and mortality. The Lancet Countdown’s 2023 U.S. Brief underscores the escalating threat of fossil fuel pollution and climate change to health, highlighting an 88% increase in heat-related mortality among older adults and calling for urgent, equitable climate action to mitigate this public health crisis.

Inadequacies in Current Healthcare System Response

Reports from healthcare institutions and public health agencies highlight how current coding practices contribute to the under-recognition of heat-related health impacts in vulnerable populations, exacerbating existing health disparities. The current inadequacies in ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health cases hinder effective healthcare delivery, compromise data accuracy, and impede the development of targeted response strategies. Challenges in coding accuracy are evident in existing studies and reports, emphasizing the difficulties healthcare providers face in accurately documenting extreme heat-related health cases. An analysis of emergency room visits during heat waves further indicates a gap in recognition and coding, pointing to the need for improved medical education and coding practices. Audits of healthcare coding practices reveal inconsistencies and inaccuracies that stem from a lack of standardized medical education and preparedness measures, ultimately leading to underreporting and misclassification of extreme heat cases. Comparative analyses of health data from regions with robust coding practices and those without highlight the disparities in data accuracy, emphasizing the urgent need for standardized coding protocols.

There is a crucial opportunity to enhance public health preparedness by addressing the challenges associated with accurate ICD-10 coding in extreme heat-related health cases. Reports from government agencies and economic research institutions underscore the economic toll of extreme heat events on healthcare systems, including increased healthcare costs, emergency room visits, and lost productivity due to heat-related illnesses. Data from social vulnerability indices and community-level assessments emphasize the disproportionate impact of extreme heat on socially vulnerable populations, highlighting the urgent need for targeted policies to address health disparities.

Opportunity

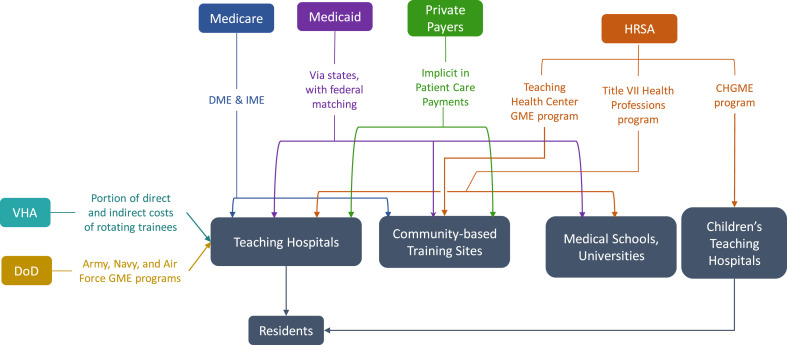

As Medicare is the largest federal source of Graduate Medical Education (GME) funding (Figure 1), the Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS) Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) play a critical role in developing coding guidelines. Thus, it is essential for HHS, CMS, and other pertinent coordinating agencies to be involved in the process for developing climate change-informed graduate medical curricula.

By focusing on medical education enhancement, strategic measures within HHS, and fostering interagency collaboration, the healthcare system can strengthen its resilience against the health impacts of extreme heat events. Improving coding accuracy, enhancing healthcare provider knowledge, streamlining emergency response efforts, and mitigating health disparities related to extreme heat events will ultimately strengthen the healthcare system and foster more effective, inclusive, and equitable climate and health policies. Improving the knowledge and training of healthcare providers empowers them to respond more effectively to extreme heat-related health cases. This immediate response capability contributes to the overarching goal of reducing morbidity and mortality rates associated with extreme heat events and creates a public health system that is more resilient and prepared for emerging challenges.

The inclusion of ICD-10 coding education into graduate medical education funded by CMS aligns with the precedent set by the Pandemic and All Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA), emphasizing the importance of preparedness and response to public health emergencies. Similarly, drawing inspiration from the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act), which promotes the adoption of electronic health records (EHR) systems, presents an opportunity to modernize medical education and ensure the seamless integration of climate-related health considerations. This collaborative and forward-thinking approach recognizes the interconnectedness of health and climate, offering a model that can be applied to various health challenges. Integrating mandates from PAHPA and the HITECH Act serves as a policy precedent, guiding the healthcare system toward a more adaptive and proactive stance in addressing climate change impacts on health.

Conversely, the consequences of inaction on the health impacts of extreme heat extend beyond immediate health concerns. They permeate through the fabric of society, widening health disparities, compromising the accuracy of health data, and undermining emergency response preparedness. Addressing these challenges requires a proactive and comprehensive approach to ensure the well-being of communities, especially those most vulnerable to the effects of extreme heat.

Plan of Action

The following recommendations aim to facilitate public health preparedness for extreme heat events through enhancements in medical education, strategic measures within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), and fostering interagency collaboration.

Recommendation 1a. Integrate extreme heat training into the GME curriculum.

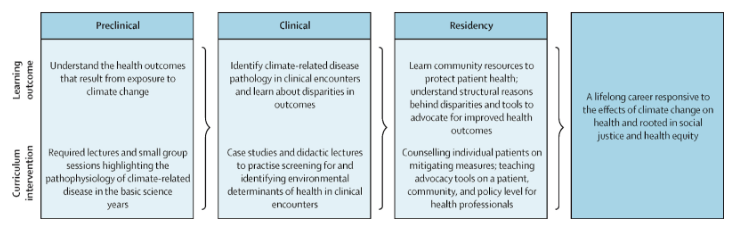

Integrating modules on extreme heat-related health impacts and accurate ICD-10 coding into medical education curricula is essential for preparing future healthcare professionals to address the challenges posed by climate change. This initiative will ensure that medical students receive comprehensive training on identifying, treating, and documenting extreme heat-related health cases. Sec. 304. Core Education and Training of the PAHPA provides policy precedent to develop foundational health and medical response curricula and training materials by modifying relevant existing programs to enhance responses to public health emergencies. Given the prominence of Medicare in funding medical residency training, policies that alter Medicare GME can affect the future physician supply and can be used to address identified healthcare workforce priorities related to extreme heat (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A model for comprehensive climate and medical education (adapted from Jowell et al. 2023)

Recommendation 1b. Collaborate with Veterans Health Administration Training Programs.

Partnering with the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to extend climate-related health coding education to Veterans Health Administration (VHA) training programs will enhance the preparedness of healthcare professionals within the VHA system to manage and document extreme heat-related health cases among veteran populations.

Recommendation 2. Collaborate with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

Establishing a collaborative research initiative with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) will facilitate the in-depth exploration of accurate ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health cases. This should be accomplished through the following measures:

Establish joint task forces. CMS, NCHS, and AHRQ should establish joint research initiatives focused on improving ICD-10 coding accuracy for extreme heat-related health cases. This collaboration will involve identifying key research areas, allocating resources, and coordinating research activities. Personnel from each agency, including subject matter experts and researchers from the EPA, NOAA, and FEMA, will work together to conduct studies, analyze data, and publish findings. By conducting systematic reviews, developing standardized coding algorithms, and disseminating findings through AHRQ’s established communication channels, this initiative will improve coding practices and enhance healthcare system preparedness for extreme heat events.

Develop standardized coding algorithms. AHRQ, in collaboration with CMS and NCHS, will lead efforts to develop standardized coding algorithms for extreme heat-related health outcomes. This involves reviewing existing coding practices, identifying gaps and inconsistencies, and developing standardized algorithms to ensure consistent and accurate coding across healthcare settings. AHRQ researchers and coding experts will work closely with personnel from CMS and NCHS to draft, validate, and disseminate these algorithms.

Integrate into Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) programs. Establish collaborative partnerships between the VA and other federal healthcare agencies, including CMS, HRSA, and DoD, to integrate education on ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health outcomes into CQI programs. Regularly assess the effectiveness of training initiatives and adjust based on feedback from healthcare providers. For example, CMS currently requires physicians to screen for the social determinants of health and could include level of climate and/or heat risk within that screening assessment.

Allocate resources. Each agency will allocate financial resources, staff time, and technical expertise to support collaborative activities. Budget allocations will be based on the scope and scale of specific initiatives, with funds earmarked for research, training, data sharing, and evaluation efforts. Additionally, research funding provided through PHSA Titles VII and VIII can support studies evaluating the effectiveness of educational interventions on climate-related health knowledge and practice behaviors among healthcare providers.

Recommendation 3. Leverage the HITECH Act and EHR.

Recommendation 4. Establish climate-resilient health system grants to incentivize state-level climate preparedness initiatives

HHS and OCCHE should create competitive grants for states that demonstrate proactive climate change adaptation efforts in healthcare. These agencies can encourage states to integrate climate considerations into their health plans by providing additional funding to states that prioritize climate resilience.

Within CMS, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) could help create and administer these grants related to climate preparedness initiatives. Given its focus on innovation and testing new approaches, CMMI could design grant programs aimed at incentivizing state-level climate resilience efforts in healthcare. Given its focus on addressing health disparities and promoting preventive care, the Bureau of Primary Health Care (BPHC) within HRSA could oversee grants aimed at integrating climate considerations into primary care settings and enhancing resilience among vulnerable populations.

Conclusion

These recommendations provide a comprehensive framework for HHS — particularly CMS, HRSA, and OCCHE— to bolster public health preparedness for the health impacts of extreme heat events. By leveraging funding mechanisms, incentives, and requirements, HHS can enhance health system preparedness, improve health provider knowledge, and optimize emergency response capabilities. These strategic measures encompass a range of actions, including establishing dedicated grant programs, incentivizing climate-competent healthcare providers, integrating climate-resilience metrics into quality measurement programs, and leveraging the HITECH Act to enhance ICD-10 coding education. Collaboration with other federal agencies further strengthens the coordinated response to the growing challenges posed by climate change-induced extreme heat events. By implementing these policy recommendations, HHS can effectively address the evolving landscape of climate change impacts on health and promote a more resilient and prepared healthcare system for the future.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

- Improved Accuracy in ICD-10 Coding: Healthcare providers consistently apply accurate ICD-10 coding for extreme heat-related health cases.

- Enhanced Healthcare Provider Knowledge: Healthcare professionals possess comprehensive knowledge on extreme heat-related health impacts, improving patient care and response strategies.

- Strengthened Public Health Response: A coordinated effort results in a more effective and equitable public health response to extreme heat events, reducing health disparities.

- Improved Public Health Resilience:

- Short-Term Outcome: Healthcare providers, armed with enhanced knowledge and training, respond more effectively to extreme heat-related health cases.

- Long-Term Outcome: Reduced morbidity and mortality rates associated with extreme heat events lead to a more resilient and prepared public health system.

- Enhanced Data Accuracy and Surveillance:

- Short-Term Outcome: Improved accuracy in ICD-10 coding facilitates more precise tracking and surveillance of extreme heat-related health outcomes.

- Long-Term Outcome: Comprehensive and accurate data contribute to better-informed public health policies, targeted interventions, and long-term trend analysis.

- Reduced Health Disparities:

- Short-Term Outcome: Incentives and education programs ensure that healthcare providers prioritize accurate coding, reducing disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of extreme heat-related illnesses.

- Long-Term Outcome: Health outcomes become more equitable across diverse populations, mitigating the disproportionate impact of extreme heat on vulnerable communities.

- Increased Public Awareness and Education:

- Short-Term Outcome: Public health campaigns and educational initiatives raise awareness about the health risks associated with extreme heat events.

- Long-Term Outcome: Informed communities adopt preventive measures, reducing the overall burden on healthcare systems and fostering a culture of proactive health management.

- Streamlined Emergency Response and Preparedness:

- Short-Term Outcome: Integrating extreme heat preparedness into emergency response plans results in more efficient and coordinated efforts during heatwaves.

- Long-Term Outcome: Improved community resilience, reduced strain on emergency services, and better protection for vulnerable populations during extreme heat events.

- Increased Collaboration Across Agencies:

- Short-Term Outcome: Collaborative efforts between OCCHE, CMS, HRSA, AHRQ, FEMA, DoD, and the Department of the Interior result in streamlined information sharing and joint initiatives.

- Long-Term Outcome: Enhanced cross-agency collaboration establishes a model for addressing complex public health challenges, fostering a more integrated and responsive government approach.

- Empowered Healthcare Workforce:

- Short-Term Outcome: Incentives for accurate coding and targeted education empower healthcare professionals to address the unique challenges posed by extreme heat.

- Long-Term Outcome: A more resilient and adaptive healthcare workforce is equipped to handle emerging health threats, contributing to overall workforce well-being and satisfaction.

- Informed Policy Decision-Making:

- Short-Term Outcome: Policymakers utilize accurate data and insights to make informed decisions related to extreme heat adaptation and mitigation strategies.

- Long-Term Outcome: The integration of health data into broader climate and policy discussions leads to more effective, evidence-based policies at local, regional, and national levels.

Combating Extreme Heat with a National Moonshot

Extreme heat is the leading cause of weather-related deaths in the United States and has been for the past 30 years. Low-income communities and many other vulnerable populations are disproportionately affected by heat risk. As the climate continues to warm, the threat to public health will correspondingly increase. Through a presidential directive, the White House Climate Policy Office (WHCPO) should establish the National Moonshot to Combat Extreme Heat, an all-of-government program to harmonize and accelerate federal efforts to reduce heat risk and heat illness, save lives, and improve the cost-effectiveness of federal expenditures.

The goals of the Moonshot are to:

- Reduce heat deaths by 20% by 2030, 40% by 2035, and 60% by 2050.

- Build 150 heat-resilient communities by 2030 by facilitating access to funding and uplifting social infrastructure actions prioritizing at-risk, vulnerable populations.

- Increase visibility and awareness of federal efforts to protect residents from extreme heat.

The Moonshot will be overseen by a new, high-level appointee at WHCPO to serve as the Executive Officer of the White House Interagency Work Group on Extreme Heat (WHIWG).

Challenge and Opportunity

The threat to public health and safety from extreme heat is serious, expansive, and increasing as the planet continues to warm. According to Heat.gov, “Extreme heat has been the greatest weather-related cause of death in the U.S. for the past 30 years — more than hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding or extreme cold.” The number of deaths from extreme heat is difficult to accurately determine and is frequently undercounted. More recently, during the Heat Dome of 2021, the state of Washington reported 1,231 heat deaths in just one month. Further, heat-related illness includes a broad spectrum of diseases, from mild heat cramps to life-threatening heat stroke. Heat exposures have been linked to mental health illnesses and adverse birth outcomes, such as preterm births and low birth weights. Extreme heat disproportionately impacts marginalized people, including those that are low-income, BIPOC, seniors, veterans, children, the unhoused, and those with compromised health status, among others. All heat illnesses and deaths are considered preventable.

Extreme heat is an all-of-society problem that requires an all-of-government response. As the frequency, intensity, duration, and breadth of heat waves have increased dramatically over the past four years, officials and leaders at all levels have begun taking action.

The federal government has launched new programs for addressing extreme heat over the last few years as heat waves have become a front-page issue. Recent programs initiated by the Biden Administration are providing a variety of resources and increasing awareness of this threat. Key examples are:

- The White House Interagency Work Group on Extreme Heat (WHIWG) on Extreme Heat was launched in September 2021 to coordinate a “holistic” response. The WHIWG began work with the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) to develop a National Heat Strategy in July 2023. Information about the WHIWG is primarily communicated to the public through press releases from the White House. The initiative announced several new actions to address heat, including a rulemaking process at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to develop a workplace heat standard and actions and ongoing data collection efforts (i.e., syndromic surveillance and heat island mapping campaigns) by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and NIHHIS. The White House also announced a new set of planning tools to address extreme heat in April 2023 as part of the American Rescue Plan.

- In addition to working with the WHIWG, NIHHIS collaborates with the CDC and over 20 other federal agencies through Heat.gov, a resource hub for federal extreme heat and health information. NIHHIS focuses on developing and sharing information and tools, increasing interagency coordination, and developing a National Heat Strategy.

- The National Climate Resilience (NCR) Framework takes a high-level approach to building climate resilience through six overarching objectives. However, detailed treatment of extreme heat in the Framework is minimal.

Actions are needed to remedy the deficit in attention to extreme heat by uplifting the role of extreme heat in the federal response to climate impacts and give greater emphasis to social infrastructure actions.

Several bills to address extreme heat through federal legislation have been introduced in Congress, though none have advanced. Most notable are:

- S. 2645: Senator Edward Markey’s Preventing HEAT Illness and Deaths Act of 2023 would authorize NIHHIS to prescribe actions and provide funding.

- HR 3965: Representative Ruben Gallego’s “Extreme Heat Emergency Act of 2023” would amend the Stafford Act by adding “extreme heat” as a natural disaster for which response aid is authorized.

- H.R. 2945: Representative Ruben Gallego’s Excess Urban Heat Mitigation Act of 2023” would require the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to establish a grant program to fund activities to mitigate or manage heat in urban areas. The Senate version of this bill, S. 1379, is led by Senator Sherrod Brown.

Even with this momentum, actions are dispersed across many departments and agencies. Plus, many local and state governments tend to apply for federal funding on a program-by-program, agency-by-agency basis and must navigate a complicated landscape with limited funding explicitly earmarked for heat resilience. Further, most “infrastructure” and capacity-building funding is based on mitigating or restoring economic loss of property, leading to financial relief that has gone primarily to built infrastructure and natural infrastructure projects. Communities need social infrastructure: social cohesion, policy and governance, public health, communications and alerts, planning, etc., to respond to extreme heat. This requires a pathway for communities to access funds to combat extreme heat in a comprehensive and coordinated way and bring social infrastructure actions up to a level equal to built and natural infrastructure interventions.

There is a need to improve the coordination of heat actions across the federal government, align heat resilience activities with Justice40 mandates, and promote community-based interventions to reduce heat deaths. A National Moonshot to Combat Extreme Heat can do this by leveraging several new community-focused programs to accelerate the protection of at-risk populations from heat-related death and illness. The challenge, and therefore the opportunity, for the Moonshot is to identify, integrate, and accelerate existing resources in a human-centric framework to reduce preventable deaths, promote cool and healthy communities, and deliver value nationwide.

Plan of Action

The WHCPO should appoint a new Deputy Director for Heat to serve as the Executive Officer of the WHIWG and coordinate the National Moonshot to Combat Extreme Heat – an all-of-government program to accelerate federal actions to address extreme heat. The goals of the Moonshot are to:

- Reduce heat deaths by 20% by 2030, 40% by 2035, and 60% by 2050;

- Build 150 heat-resilient communities by 2030 by facilitating access to funding and uplifting social infrastructure actions prioritizing at-risk, vulnerable populations. Social infrastructure encompasses a variety of actions in four categories: social cohesion, policy, communications, and planning. Social infrastructure centers the needs of people in resilience. This target aligns with the U.S. goal to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 50% by 2030.

- Improve visibility and awareness of federal efforts to protect residents from extreme heat.

The Moonshot will capitalize on existing policies, programs, and funding and establish a human-centric approach to climate resilience by uplifting extreme heat. The Moonshot will identify and evaluate existing federal activities and available funding, including funds from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), as well as agency budgets, including Federal Emergency Management Agency’s funding for the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) and the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (HMGP). The Moonshot will integrate actions among the many existing programs dispersed across the government into a well-coordinated, integrated inter-agency initiative that maximizes results and will support cool, safe, and healthy communities

Recommendation 1. Enhance the visibility, responsibility, and capacity of the WHIWG.

Signaling high-level support through a presidential directive, the WHCPO should appoint a Deputy Director for Heat as the Executive Officer of the WHIWG to lead the Moonshot. Two additional staff positions will be established to support the assessment, stakeholder engagement, and planning processes. The WHIWG and the Deputy Director will design and implement the Moonshot working with the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Climate Change and Health Equity. A lead contact will be designated in each agency and department participating in the NIHHIS program.

Recommendation 2. Assess and report current status.

The Moonshot should identify, evaluate, and report on existing programs addressing heat across the federal government, including those recently launched by the White House, to establish a current baseline, identify gaps, and catalog opportunities for integration within the federal government. The Moonshot will generate a database of existing programs and a budget cross-cut analysis to identify current funding levels. The report will incorporate the NIHHIS Extreme Heat Strategy and identify existing funding opportunities, including those in the IRA, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, and agency programs. The Moonshot will also work with CDC and NIHHIS to develop a method to identify heat deaths to establish a baseline for tracking progress on the goals.

Recommendation 3. Build broad community support.

The Moonshot should convene conversations and conduct regional extreme heat workshops with state, local, and tribal government personnel; external experts and stakeholders; Justice40 community leaders; professional associations; private sector representatives; and philanthropies. Topics should span the spectrum of social infrastructure, including social cohesion, public health, insurance, infrastructure, communications, and more. Based on input, the Moonshot will establish an advisory committee of non-government participants and develop pathways to connect stakeholders with federal community-focused climate resilience programs, including the White House’s Justice 40 program, EPA’s Environmental Justice Thriving Communities Technical Assistance Centers Program, and the Department of Transportation’s Thriving Communities Network, and other relevant federal programs identified in Recommendation 2. The Moonshot would add extreme heat as a covered issue area in these programs.

Recommendation 4. Make a plan.

The Moonshot should expand upon the NIHHIS Extreme Heat Strategy and make a heat action plan uplifting human health and community access to harness the potential of federal heat programs. The plan would assign roles, responsibilities, and deadlines and establish a process to track and report progress annually. In addition, the Moonshot would expand the NCR Framework to include an implementation plan and establish a human-centric approach. The Moonshot will evaluate co-benefits from heat reduction strategies, including the role cool surfaces play in protecting public health while also decreasing smog, reducing energy use, and solar radiation management. And, consistent with the Biden Administration’s 2025 priorities, the Moonshot will support research and development on emerging technologies such as microfiber fabrics that keep people cool during heat waves, temperature-sensitive coatings, and high-albedo reflective materials that can reduce the need for mechanical air-conditioning. Innovation is especially needed related to resurfacing the nation’s aging roadways.

The Moonshot will also include a communications plan to increase awareness of federal programs and funding opportunities to combat extreme heat. This should all be in place in nine months to prepare for the FY 2026 budget. The NIHHIS and CDC will develop an enhanced method for improving the accuracy of tracking heat deaths.

Recommendation 5. Connect with people and communities.

The Moonshot should emphasize social infrastructure projects and facilitate access to funding by establishing a centralized portal for comprehensive local heat action planning and programs. The Moonshot will help build cool, safe, healthy communities by integrating heat into federal climate equity programs and supporting local heat plans and projects that reflect community input and priorities. Local heat plans should be comprehensive and integrate a suite of actions that emphasize social infrastructure and include built infrastructure and natural infrastructure.

Recommendation 6. Initiate all-of-government action.

The Moonshot will catalyze the implementation of the plan across the government, including all the agencies and departments identified in Recommendation 1. It will establish the grant portal to enhance access to federal resources for heat-related projects for state, local, tribal, and territorial governments, and community groups. It will launch a communications plan targeting press, social media, public employees at all levels of government, stakeholders, and more.

Recommendation 7. Support legislation to secure long-term success

In coordination with the White House Office of Legislative Affairs and Office of Management and Budget (OMB), the Moonshot should work with Congress to draft and support federal legislation and appropriations addressing extreme heat. Congressional authority is needed to firmly establish this human-centric approach to extreme heat. The Moonshot may recommend Congressional hearings on legislation or a Congressional commission to review the Administration’s work on heat. For example, the passage of S. 2645 would enshrine the position of NIHHIS in law. The Moonshot will help Congress fulfill its role in the all-of-government response and help empower local action.

Costs

Using information gathered in Recommendation 2, the Moonshot will focus on capturing and directing existing federal funding, including from the IRA, BIL, agency budgets, and grant programs to uplift actions addressing extreme heat and implementing the Moonshot action plan. Initial costs should be minimal: $1 million to hire the Executive Director and two staff and to report on existing programs, funding, and agency budgets. The Moonshot will produce a budget cross-cut initially and annually thereafter and assemble a budget proposal for the WHIWG on Extreme Heat for the FY 2025 and FY 2026 budget.

The Moonshot recommendation is aligned with the OMB Budget Memo of August 17, 2023, which transmits Guidance for Research and Development Priorities for the FY 2025 Budget. The OMB priorities call for addressing climate change by protecting communities’ health and mitigating its health effects, especially for communities that experience these burdens disproportionately.

Conclusion

Extreme heat is a serious public health problem disproportionately impacting many vulnerable populations, and the threat is increasing tremendously. So far in winter 2023, more than 130 monthly high-temperature records were set across the U.S.

The federal government has several programs addressing the threat of extreme heat in the U.S., and the WHIWG reflects the all-of-government approach needed to meet the threat. The next step is to capture the full potential of existing programs and funding by launching a focused and intensive National Moonshot to Combat Extreme Heat with quantitative goals to track and reduce heat deaths and build healthy communities. This effort will enable state and local governments and communities, especially those disproportionately impacted by extreme heat, to more readily access federal funding to develop and implement comprehensive heat action plans. The Moonshot will reduce heat deaths, improve the quality of life in cities, and reduce economic productivity loss while increasing the visibility of federal leadership on this issue.

With heat season 2024 beginning on April 29th, it’s essential to establish an all-of-government response to address extreme heat at all levels.

This idea of merit originated from our Extreme Heat Ideas Challenge. Scientific and technical experts across disciplines worked with FAS to develop potential solutions in various realms: infrastructure and the built environment, workforce safety and development, public health, food security and resilience, emergency planning and response, and data indices. Review ideas to combat extreme heat here.

Federal agencies involved in NIHHIS include: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Administration for Community Living, Administration for Children and Families, Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Department of Defense, Department of Energy, Department of Transportation, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Department of Veterans Affairs, US Census Bureau, Forest Service, National Park Service, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Occupational Safety and Health Administration, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and United States Agency for International Development.

Non-federal partners include, but are not limited to: CAPA Strategies, ESRI, Global Cool Cities Alliance, National League of Cities, and Global Heat Health Information Network.

For America to Become Climate Resilient, We Need Innovative Policy Solutions to Address The Extreme Heat Crisis

As 2023 was the hottest year on record, America must start to prepare for even hotter years in the future. To meet this moment, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has launched the Extreme Heat Policy Sprint, an initiative to accelerate experts’ high-impact policy recommendations to comprehensively address the extreme heat crisis.

The urgency of this initiative is underscored by global average temperatures soaring to a record 2.63°F (1.46°C) increase from pre-industrial levels and heat-related mortalities forecasted to surge 370% within the next three decades. In Maricopa County, Arizona alone, at least 579 people lost their lives to heat last year, with senior citizens accounting for one in three deaths. This staggering number is widely considered an undercount, as heat-related mortalities are difficult to document.

With heat being the top weather-related killer of Americans and the nation having faced the hottest summer on record, the federal government made the largest resourcing of extreme heat mitigation in history last year. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) distributed $1 billion in grants to projects expanding urban tree canopies to reduce average temperatures during extreme heat events, amongst other co-benefits like flood reduction and improved public health outcomes. In addition, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provided $5 million in funding for two centers of excellence to deliver actionable, place-based climate information for community heat resilience. These efforts were complemented by the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) distribution of $1.8 billion through two grant programs designed to help communities increase their resilience to the impacts of climate change, including extreme heat.

Despite these federal programs, the resourcing needs for future extreme heat conditions are growing exponentially, with anticipated exposure to dangerous heat (>125 °F) expected to impact 107.6 million Americans by 2053. Several key U.S. cities are expected to experience risky wet bulb temperatures of +87°F, which would trigger deadly heat stress and stroke in vulnerable populations within just a few years. These conditions would completely suspend safe outdoor operations of the city during the summer months. Further, the exponential growth of cooling technology adoption across the country catalyzes increased demand for energy, thereby increasing fossil fuel emissions and straining electric grids to the point of risky blackouts.

With such immense risks coming alarmingly soon, there is a need for transformative strategies to protect Americans from the heat where they live, where they work, and in their communities. Resilience to heat must be included in nationwide planning and management. The built environment must be adapted to chronic, sustained heat. Novel resilient cooling technologies need to be brought rapidly to market. Communities need climate services that include heat risk and offer regionally-specific solutions. The full health and economic costs of heat must be accounted for and responded to. All of this requires integrating heat resilience into every part of the federal government and developing new governance models for climate and health, focusing on adaptation-forward, people-centered disaster response approaches.

Introducing the Participants of the Extreme Heat Policy Sprint

This critical situation sets the stage for the pivotal contributions of the experts in the Extreme Heat Policy Sprint. Each of these professionals offer innovative and impactful policy recommendations, drawing from diverse areas of expertise, including but not limited to climate resilience, health care, public policy, law, and urban planning. This collaboration is essential in shaping effective federal strategies to mitigate the far-reaching impacts of extreme heat on communities nationwide.

Infrastructure and the Built Environment

- Bill Updike, Smart Surfaces Coalition, Program Manager

- Jacob Miller, Smart Surfaces Coalition, Project Manager

- Dan Metzger, Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, Smart Surfaces Fellow

- Kurt Shickman, Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, Former Director of Extreme Heat Initiatives

- Justin Schott, University of Michigan, Lecturer and Project Manager of the Energy Equity Project

- Dr. Vivek Shandas, Portland State University, Professor

- Dr. Larissa Larsen, University of Michigan, Professor

Workforce Safety and Development

- Dr. June Spector, University of Washington, Physician-scientist

- Dr. Margaret Morrissey-Basler, Providence College, Assistant Professor of Health Sciences

- Douglas Casa, University of Connecticut Korey Stringer Institute, Chief Executive Officer

Public Health and Preparedness

- Dr. Kari Nadeau, Harvard University Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, Professor and Director

- Nile Nair, Harvard University Center for Climate, Health and the Global Environment, Ambassador and PhD Fellow

- Nathaniel Matthews-Trigg, Americares, Associate Director of Climate and Disaster Resilience

- Dr. Arnab Ghosh, Cornell University, Assistant Professor of Medicine

Food Security

- Lori Adornato, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, former Program Manager

Planning and Response

- Louis Blumberg, Senior Climate Policy Advisor, Climate Resolve

- Johanna Lawton, Project Manager, Rebuild by Design

- Dr. Julie Robinson, Pima County Department of Health, Program Officer of Climate & Environmental Health Justice

- Kat Davis, Pima County, Division Manager of Emergency Mitigation and Preparedness

- Dr. Theresa Cullen, Pima County, Public Health Director

Data and Indices

- Dr. Alistair Hayden, Cornell University, Professor of Practice Public & Ecosystem Health

- Rebecca Morgenstern-Brenner, Cornell University Brooks School Public Policy, Senior Lecturer

- Dr. Amie Patchen, Cornell University Department of Public & Ecosystem Health, Chief Lecturer

- Dr. Nathaniel Hupert, Weill Cornell Medical College, Internal Medicine Physician and Public Health Researcher

- Bianca Corpuz, Johns Hopkins University, PhD Candidate

- Dr. Jeremy Hess, University of Washington, Director of Center for Health and the Global Environment (CHanGE) and Professor in the Schools of Medicine and Public Health

- Dr. Tim Sheehan, University of Washington Center for Health and the Global Environment (CHanGE), Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Leveraging Positive Tipping Points to Accelerate Decarbonization

Summary

The Biden Administration has committed the United States to net-zero emissions by 2050. Meeting this commitment requires drastic decarbonization transitions across all sectors of society at a pace never seen before. This can be made possible by positive tipping points, which demarcate thresholds in decarbonization transitions that, once crossed, ensure rapid progress towards completion. A new generation of economic models enables the analysis of these tipping points and the evaluation of effective policy interventions.

The Biden Administration should undertake a three-pronged strategy for leveraging the power of positive tipping points to create a larger-than-anticipated return on investment in the transition to a clean energy future. First, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) and the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) should evaluate new economic models and make recommendations for how agencies can incorporate such models into their decision-making process. Second, federal agencies should integrate positive tipping points into the research agendas of existing research centers and programs to uncover additional decarbonization opportunities. Finally, federal agencies should develop decarbonization strategies and policies based on insights from this research.

Challenge and Opportunity

Climate change brings us closer each year to triggering negative tipping points, such as the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet or the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. These negative tipping points, driven by self-reinforcing environmental feedback loops, significantly accelerate the pace of climate change.

Meeting the Biden Administration’s commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050 will reduce the risk of these negative tipping points but requires the United States to significantly accelerate the current pace of decarbonization. Traditional economic models used by the federal government and organizations such as the International Energy Agency consistently underestimate the progress of zero-emission technologies and the return on investment of policies that enable a faster transition, resulting in the agency’s “largest ever upwards revision” last year. A new school of thought presents “evidence-based hope” for rapidly accelerating the pace of decarbonization transitions. Researchers point out that our society consists of complex and interconnected social, economic, and technological systems that do not change linearly under a transition, as traditional models assume; rather, when a positive tipping point is crossed, changes made to the system can lead to disproportionately large effects. A new generation of economic models has emerged to support policymakers in understanding these complex systems in transition and identifying the best policies for driving cost-effective decarbonization.

At COP26 in 2021, leaders of countries responsible for 73% of world emissions, including the United States, committed to work together to reach positive tipping points under the Breakthrough Agenda. The United Kingdom and other European countries have led the movement thus far, but there is an opportunity for the United States to join as a leader in implementing policies that intentionally leverage positive tipping points and benefit from the shared learnings of other nations.

Domestically, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) include some of the strongest climate policies that the country has ever seen. The implementation of these policies presents a natural experiment for studying the impact of different policy interventions on progress towards positive tipping points.

How do positive tipping points work?

Figure 1. Diagram of a system and its positive tipping point. The levers for change on the left push the system away from the current high-emission state and towards a new net-zero state. As the system moves away from the current state, the self-reinforcing feedback loops in the system become stronger and accelerate the transition. At the positive tipping point, the feedback loops become strong enough to drive the system towards the new state without further support from the levers for change. Thus, policy interventions for decarbonization transitions are most crucial in the lead up to a positive tipping point. (Adapted from the Green Futures Network.)

Just as negative tipping points in the environment accelerate the pace of climate change, positive tipping points in our social, economic, and technological systems hold the potential to rapidly accelerate the pace of decarbonization (Figure 1). These positive tipping points are driven by feedback loops that generate increasing returns to adoption and make new consumers more likely to adopt (Figure 2):

- Learning by doing: As manufacturers produce more of a technology, they learn how to produce the technology better and cheaper, incentivizing new consumers to adopt it.

- Economies of scale: Manufacturers are able to realize cost savings as they increase their production capacity, which they pass on to consumers as lower prices that spur more demand.

- Social contagion: The more people adopt a new technology, the more likely other people will imitate and adopt it.

- Complementary technology reinforcement: As a technology is adopted more widely, complementary technology and infrastructure emerge to make it more useful and accessible.

The right set of policies can harness this phenomenon to realize significantly greater returns on investment and trigger positive tipping points that give zero-emission technologies a serious boost over incumbent fossil-based technologies.

Figure 2. Examples of positive feedback loops: (a) learning by doing, (b) social contagion, and (c) complementary technology reinforcement.

One way of visualizing progress towards a positive tipping point is the S-curve, where the adoption of a new zero-emission technology grows exponentially and then saturates at full adoption. This S-curve behavior is characteristic of many historic energy and infrastructure technologies (Figure 3). From these historic examples, researchers have identified that the positive tipping point occurs between 10% and 40% adoption. Crossing this adoption threshold is difficult to reverse and typically guarantees that a technology will complete the S-curve.

Figure 3. The historic adoption of a sample of infrastructure and energy systems (top) and manufactured goods (bottom). Note that the sharpness of the S-curve can vary significantly. (Source: Systemiq)

For example, over the past two decades, the Norwegian government helped build electric vehicle (EV) charging infrastructure (complementary technology) and used taxes and subsidies to lower the price of EVs below that of gas vehicles. As a result, consumers began purchasing the cheaper EVs, and over time manufacturers introduced new models of EVs that were cheaper and more appealing than previous models (learning by doing and economies of scale). This led to EVs skyrocketing to 88% of new car sales in 2022. Norway has since announced that it would start easing its subsidies for EVs by introducing two new EV taxes for 2023, yet EV sales have continued to grow, taking up 90% of total sales so far in 2023, demonstrating the difficult-to-reverse nature of positive tipping points. Norway is now on track to reach a second tipping point that will occur when EVs reach price parity with gas vehicles without assistance from taxes or subsidies.

Due to the interconnected nature of social and technological systems, triggering one positive tipping point can potentially increase the odds of another tipping point at a greater scale, resulting in “upward-scaling tipping cascades.” Upward-scaling tipping cascades can occur in two ways: (1) from a smaller system to a larger system (e.g., as more states reach their tipping point for EV adoption, the nation as a whole gets closer to its tipping point) and (2) from one sector to another. For the latter, researchers have identified three super-leverage points that policymakers can use to trigger tipping cascades across multiple sectors:

- Light-duty EVs → heavy-duty EVs and renewable energy storage: The development of cheaper batteries for light-duty EVs will enable cheaper heavy-duty EVs and renewable energy storage thanks to shared underlying battery technology. The build-out of charging infrastructure for light-duty EVs will also facilitate the deployment of heavy-duty EVs.

- Green ammonia → heavy industries, shipping, and aviation: The production of green ammonia requires green hydrogen as an input, so the growth of the former will spur the growth of the latter. Greater production of green hydrogen and green ammonia will catalyze the decarbonization of the heavy industries, shipping, and aviation sectors, which use these chemicals as fuel inputs.

- Traditional and alternative plant proteins → land use: Widespread consumption of traditional and alternative plant proteins over animal protein will reduce pressure on land-use change for agriculture and potentially restore significant amounts of land for conservation and carbon sequestration.

The potential for this multiplier effect makes positive tipping points all the more promising and critical to understand.

Further research to identify positive tipping points and tipping cascades and to improve models for evaluating policy impacts holds great potential for uncovering additional decarbonization opportunities. Policymakers should take full advantage of this growing field of research by integrating its models and insights into the climate policy decision-making process and translating insights from researchers into evidence-based policies.

Plan of Action

In order for the government to leverage positive tipping points, policymakers must be able to (1) identify positive tipping points and tipping cascades before they occur, (2) understand which policies or sequences of policies may be most cost-effective and impactful in enabling positive tipping points, and (3) integrate that insight into policy decision-making. The following recommendations would create the foundations of this process.

Recommendation 1. Evaluate and adopt new economic models

The President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST) and the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) should conduct a joint evaluation of new economic models and case studies to identify where new models have been proven to be more accurate for modeling decarbonization transitions and where there are remaining gaps. They should then issue a report with recommendations on opportunities for funding further research on positive tipping points and new economic models and advise sub agenciessubagencies responsible for modeling and projections, such as the Energy Information Administration within the Department of Energy (DOE), on how to adopt these new economic models.

Recommendation 2. Integrate positive tipping points into the research agenda of federally funded research centers and programs.

There is a growing body of research coming primarily from Europe, led by the Global Systems Institute and the Economics of Energy Innovation and Systems Transition at the University of Exeter and Systemiq, that is investigating global progress towards positive tipping points and different potential policy interventions. The federal government should foster the growth of this research area within the United States in order to study positive tipping points and develop models and forecasts for the U.S. context.

There are several existing government-funded research programs and centers that align well with positive tipping points and would benefit synergistically from adding this to their research agenda:

- Power, buildings, and heavy industries: The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), funded by the DOE, has an energy analysis research program that conducts analyses of future systems scenarios, market and policy impacts, sustainability, and techno-economics. This research program would be a good fit for taking on research on positive tipping points in the power, buildings, and heavy industries sectors.

- Transportation: The National Center for Sustainable Transportation (NCST), funded by the Department of Transportation, conducts research around four research themes—Environmentally Responsible Infrastructure and Operations, Multi-Modal Travel and Sustainable Land Use, Zero-Emission Vehicle and Fuel Technologies, and Institutional Change—in order to “address the most pressing policy questions and ensure our research results are incorporated into the policy-making process.” The policy-oriented focus of the NCST makes it a good candidate for conducting research on positive tipping points in the transportation sector under the theme of Institutional Change and translating research results into policy briefs.