Unlocking AI’s Grid Modernization Potential

Surging energy demand and increasingly frequent extreme weather events are bringing new challenges to the forefront of electric grid planning, permitting, operations, and resilience. These hurdles are pushing our already fragile grid to the limit, highlighting decades of underinvestment, stagnant growth, and the pressing need to modernize our system.

While these challenges aren’t new, they are newly urgent. The society-wide emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) is bringing many of these challenges into sharper focus, pushing the already increasing electricity demand to new heights and cementing the need for deployable, scalable, and impactful solutions. Fortunately, many transformational and mature AI tools provide near-term pathways for significant grid modernization.

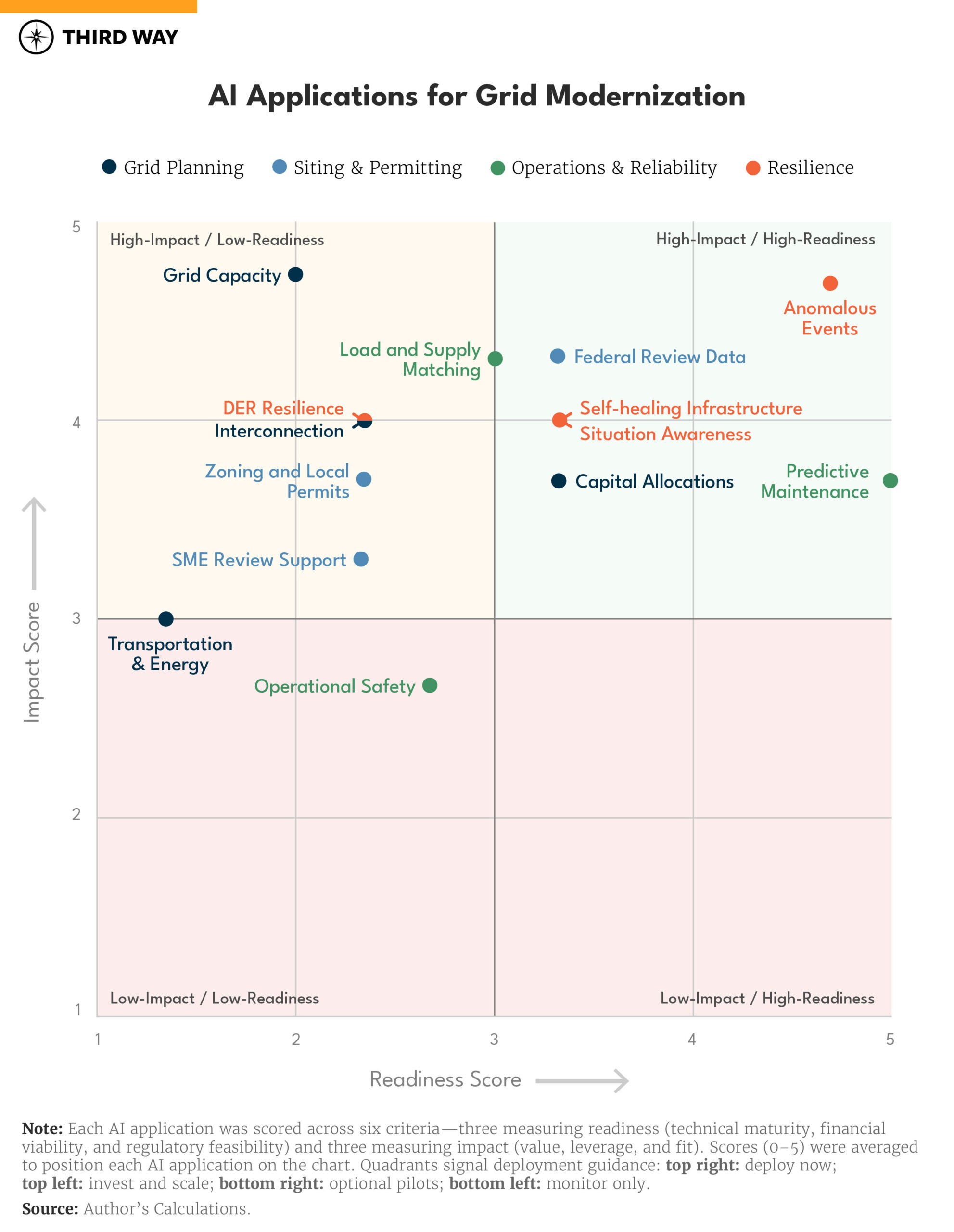

This policy memo builds on foundational research from the US Department of Energy’s (DOE) AI for Energy (2024) report to present a new matrix that maps these unique AI applications onto an “impact-readiness” scale. Nearly half of the applications identified by DOE are high impact and ready to deploy today. An additional ~40% have high impact potential but require further investment and research to move up the readiness scale. Only 2 of 14 use cases analyzed here fall into the “low-impact / low-readiness” quadrant.

Unlike other emerging technologies, AI’s potential in grid modernization is not simply an R&D story, but a deployment one. However, with limited resources, the federal government should invest in use cases that show high-impact potential and demonstrate feasible levels of deployment readiness. The recommendations in this memo target regulatory actions across the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) and the Department of Energy (DOE), data modernization programs at the Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC), and funding opportunities and pilot projects at and the DOE and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Thoughtful policy coordination, targeted investments, and continued federal support will be needed to realize the potential of these applications and pave the way for further innovation.

Challenge and Opportunity

Surging Load Growth, Extreme Events, and a Fragmented Federal Response

Surging energy demand and more frequent extreme weather events are bringing new challenges to the forefront of grid planning and operations. Not only is electric load growing at rates not seen in decades, but extreme weather events and cybersecurity threats are becoming more common and costly. All the while, our grid is becoming more complex to operate as new sources of generation and grid management tools evolve. Underlying these complexities is the fragmented nature of our energy system: a patchwork of regional grids, localized standards, and often conflicting regulations.

The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) has brought many of these challenges into sharper focus. However, the potential of AI to mitigate, sidestep, or solve these challenges is also vast. From more efficient permitting processes to more reliable grid operations, many unique AI use cases for grid modernization are ready to deploy today and have high-impact potential.

The federal government has a unique role to play in both meeting these challenges and catalyzing these opportunities by implementing AI solutions. However, the current federal landscape is fragmented, unaligned, and missing critical opportunities for impact. Nearly a dozen federal agencies and offices are engaged across the AI grid modernization ecosystem (see FAQ #2), with few coordinating in the absence of a defined federal strategy.

To prioritize effective and efficient deployment of resources, recommendations for increased investments (both in time and capital) should be based on a solid understanding of where the gaps and opportunities lie. Historically, program offices across DOE and other agencies have focused efforts on early-stage R&D and foundational science activities for emerging technology. For AI, however, the federal government is well-positioned to support further deployment of the technology into grid modernization efforts, rather than just traditional R&D activities.

AI Applications for Grid Modernization

AI’s potential in grid modernization is significant, expansive, and deployable. Across four distinct categories—grid planning, siting and permitting, operations and reliability, and resilience—AI can improve existing processes or enable entirely new ones. Indeed, the use of AI in the power sector is not a new phenomenon. Industry and government alike have long utilized machine learning (ML) models across a range of power sector applications, and the recent introduction of “foundation” models (such as large language models, or LLMs) has opened up a new suite of transformational use cases. While LLMs and other foundation models can be used in various use cases, AI’s potential to accelerate grid modernization will span both traditional and novel approaches, with many applications requiring custom-built models tailored to specific operational, regulatory, and data environments.

The following 14 use cases are drawn from DOE’s AI for Energy (2024) report and form the foundation of this memo’s analytical framework.

Grid Planning

- Capital Allocations and Planned Upgrades. Use AI to optimize utility investment decisions by forecasting asset risk, load growth, and grid needs to guide substation upgrades, reconductoring, or distributed energy resource (DER)-related capacity expansions.

- Improved Information on Grid Capacity. Use AI to generate more granular and dynamic hosting capacity, load forecast, and congestion data to guide DER siting, interconnection acceleration, and non-wires alternatives.

- Improved Transportation and Energy Planning Alignment. Use AI-enabled joint forecasting tools to align EV infrastructure rollout with utility grid planning by integrating traffic, land use, and load growth data.

- Interconnection Issues and Power Systems Models. Use AI-accelerated power flow models and queue screening tools to reduce delays and improve transparency in interconnection studies.

Siting and Permitting

- Zoning and Local Permitting Analysis. Use AI to analyze zoning ordinances, land use restrictions, and local permitting codes to identify siting barriers or opportunities earlier in the project development process.

- Federal Environmental Review Accelerations. Use AI tools to extract, organize, and summarize unstructured and disparate datasets to support more efficient and consistent reviews.

- AI Models to Assist Subject Matter Experts in Reviews. Use AI and document analysis tools to support expert reviewers by checking for completeness, inconsistencies, or precedent in technical applications and environmental documents.

Grid Operations and Reliability

- Load and Supply Matching. Use AI to improve short-term load forecasting and optimize generation dispatch, reducing imbalance costs and improving integration of variable resources.

- Predictive and Risk-Informed Maintenance. Use AI to predict asset degradation or failure and inform maintenance schedules based on equipment health, environmental stressors, and historical failure data.

- Operational Safety and Issues Reporting and Analysis. Apply AI to analyze safety incident logs, compliance records, and operator reports to identify patterns of human error, procedural risks, or training needs.

Grid Resilience

- Self-healing Infrastructure for Reliability and Resilience. Use AI to autonomously isolate faults, reconfigure power flows, and restore service in real time through intelligent switching and local control systems.

- Detection and Diagnosis of Anomalous Events. Use AI to identify and localize grid disturbances such as faults, voltage anomalies, or cyber intrusions using high-frequency telemetry and system behavior data.

- AI-enabled Situational Awareness and Actions for Resilience. Leverage AI to synthesize grid, weather, and asset data to support operator awareness and guide event response during extreme weather or grid stress events.

- Resilience with Distributed Energy Resources. Coordinate DERs during grid disruptions using AI for forecasting, dispatch, and microgrid formation, enabling system flexibility and backup power during emergencies.

However, not all applications are created equal. With limited resources, the federal government should prioritize use cases that show high-impact potential and demonstrate feasible levels of deployment readiness. Additional investments should also be allocated to high-impact / low-readiness use cases to help unlock and scale these applications.

Unlocking the potential of these use cases requires a better understanding of which ones hit specific benchmarks. The matrix below provides a framework for thinking through these questions.

Using the use cases identified above, we’ve mapped AI’s applications in grid modernization onto a “readiness-impact” chart based on six unique scoring scales (see appendix for full methodological and scoring breakdown).

Readiness Scale Questions

- Technical Readiness. Is the AI solution mature, validated, and performant?

- Financial Readiness. Is it cost-effective and fundable (via CapEx, OpEx, or rate recovery)?

- Regulatory Readiness. Can it be deployed under existing rules, with institutional buy-in?

Impact Scale Questions

- Value. Does this AI solution reduce costs, outages, emissions, or delays in a measurable way?

- Leverage. Does it enable or unlock broader grid modernization (e.g., DERs, grid enhancing technologies (GETs), and/or virtual power plant (VPP) integration)?

- Fit. Is AI the right or necessary tool to solve this compared to conventional tools (i.e., traditional transmission planning, interconnection study, and/or compliance software)?

Each AI application receives a score of 0-5 in each category, which are then averaged to determine its overall readiness and impact scores. To score each application, a detailed rubric was designed with scoring scales for each of the above-mentioned six categories. Industry examples and experience, existing literature, and outside expert consultation was utilized to then assign scores to each application.

When plotted on a coordinate plane, each application falls into one of four quadrants, helping us easily identify key insights about each use case.

- High-Impact / High-Readiness use cases → Deploy now

- High-Impact / Low-Readiness → Invest, unlock, and scale

- Low-Impact / High-Readiness → Optional pilots, but deprioritize federal effort

- Low-Impact / Low-Readiness → Monitor private sector action

Once plotted, we can then identify additional insights, such as where the clustering happens, what barriers are holding back the highest impact applications, and if there are recurring challenges (or opportunities) across the four categories of grid modernization efforts.

Plan of Action

Grid Planning

Average Readiness Score: 2.3 | Average Impact Score: 3.8

- AI use cases in grid planning face the highest financial and regulatory hurdles of any category. Reducing these barriers can unlock high-impact potential.

- These tools are high-leverage use cases. Getting these deployed unlocks deeper grid modernization activities system-wide, such as grid-enhancing technology (GETs) integration.

- While many of these AI tools are technically mature, adoption is not yet mainstream.

Recommendation 1. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) should clarify the regulatory pathway for AI use cases in grid planning.

Regional Transmission Organizations (RTOs), utilities, and Public Utility Commissions (PUCs) require confidence that AI tools are approved and supported before they deploy them at scale. They also need financial clarity on viable pathways to rate-basing significant up-front costs. Building on Commissioner Rosner’s Letters Regarding Interconnection Automation, FERC should establish a FERC-DOE-RTO technical working group on “Next-Gen Planning Tools” that informs FERC-compliant AI-enabled planning, modeling, and reporting standards. Current regulations (and traditional planning approaches) leave uncertainty around the explainability, validation, and auditability of AI-driven tools.

Thus, the working group should identify where AI tools can be incorporated into planning processes without undermining existing reliability, transparency, or stakeholder-participation standards. The group should develop voluntary technical guidance on model validation standards, transparency requirements, and procedural integration to provide a clear pathway for compliant adoption across FERC-regulated jurisdictions.

Siting and Permitting

Average Readiness Score: 2.7 | Average Impact Score: 3.8

- Zoning and local permitting tools are promising, but adoption is fragmented across state, local, and regional jurisdictions.

- Federal permitting acceleration tools score high on technical readiness but face institutional distrust and a complicated regulatory environment.

- In general, tools in this category have high value but limited transferability beyond highly specific scenarios (low leverage). Even if unlocked at scale, they have narrower application potential than other tools analyzed in this memo.

Recommendation 2. The Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC) should establish a federal siting and permitting data modernization initiative.

AI tools can increase speed and consistency in siting and permitting processes by automating the review of complex datasets, but without structured data, standardized workflows, and agency buy-in, their adoption will remain fragmented and niche. Furthermore, most grid infrastructure data (including siting and permitting documentation) is confidential and protected, leading to industry skepticism about the ability of AI to maintain important security measures alongside transparent workflows. To address these concerns, FPISC should launch a coordinated initiative that creates structured templates for federal permitting documents, pilots AI integration at select agencies, and develops a public validation database that allows AI developers to test their models (with anonymous data) against real agency workflows. Having launched a $30 million effort in 2024 to improve IT systems across multiple agencies, FPSIC is well-positioned to take those lessons learned and align deeper AI integration across the federal government’s permitting processes. Coordination with the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), which was recently called on to develop a Permitting Technology Action Plan, is also encouraged. Additional Congressional appropriations to FPISC can unlock further innovation.

Operations and Reliability

Average Readiness Score: 3.6 | Average Impact Score: 3.6

- Overall, this category has the highest average readiness across technical, financial, and regulatory scales. These use cases are clear “ready-now” wins.

- They also have the highest fit component of impact, representing unique opportunities for AI tools to improve on existing systems and processes in ways that traditional tools cannot.

Recommendation 3. Launch an AI Deployment Challenge at DOE to scale high-readiness tools across the sector.

From the SunShot Initiative (2011) through the Energy Storage Grand Challenge (2020) to the Energy Earthshots (2021), DOE has a long history of catalyzing the deployment of new technology in the power sector. A dedicated grand challenge – funded with new Congressional appropriations at the Grid Deployment Office – could deploy matching grants or performance-based incentives to utilities, co-ops, and municipal providers to accelerate adoption of proven AI tools.

Grid Resilience

Average Readiness Score: 3.4 | Average Impact Score: 4.2

- As a category, resilience applications have the highest overall impact score, including a perfect value score across all four use cases. There is significant potential in deploying AI tools to solve these challenges.

- Alongside operations and reliability use cases, these tools also exhibit the highest technical readiness, demonstrating technical maturity alongside high value potential.

- Anomalous events detection is the highest-scoring use case across all 14 applications, on both readiness and impact scales. It’s already been deployed and is ready to scale.

Recommendation 4. DOE, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and FERC should create an AI for Resilience Program that funds and validates AI tools that support cross-jurisdictional grid resilience.

AI for resilience applications often require coordination across traditional system boundaries, from utilities to DERs, microgrids to emergency managers, as well as high levels of institutional trust. Federal coordination can catalyze system integration by funding demo projects, developing integration playbooks, and clarifying regulatory pathways for AI-automated resilience actions.

Congress should direct DOE and FEMA, in consultation with FERC, to establish a new program (or carve out existing grid resilience funds) to: (1) support demonstration projects where AI tools are already being deployed during real-world resilience events; (2) develop standardized playbooks for integrating AI into utility and emergency management operations; and (3) clarify regulatory pathways for actions like DER islanding, fault rerouting, and AI-assisted load restoration.

Conclusion

Managing surging electric load growth while improving the grid’s ability to weather more frequent and extreme events is a once-in-a-generation challenge. Fortunately, new technological innovations combined with a thoughtful approach from the federal government can actualize the potential of AI and unlock a new set of solutions, ready for this era.

Rather than technological limitations, many of the outstanding roadblocks identified here are institutional and operational, highlighting the need for better federal coordination and regulatory clarity. The readiness-impact framework detailed in this memo provides a new way to understand these challenges while laying the groundwork for a timely and topical plan of action.

By identifying which AI use cases are ready to scale today and which require targeted policy support, this framework can help federal agencies, regulators, and legislators prioritize high-impact actions. Strategic investments, regulatory clarity, and collaborative initiatives can accelerate the deployment of proven solutions while innovating and building trust in new ones. By pulling on the right policy levers, AI can improve grid planning, streamline permitting, enhance reliability, and make the grid more resilient, meeting this moment with both urgency and precision.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

Scoring categories (readiness & impact) were selected based on the literature of challenges to AI deployment in the power sector. An LLM (OpenAI’s GPT-4o model) was utilized to refine the 0-5 scoring scale after careful consideration of the multi-dimensional challenges across each category, based on the author’s personal industry experience and additional consultation with outside technical experts. Where applicable, existing frameworks underpin the scales used in this memo: technology readiness levels for the ‘technical readiness category’ and adoption readiness levels for the ‘financial’ and ‘regulatory’ readiness categories. A rubric was then designed to guide scoring.

Each of the 14 AI applications were then scored against that rubric based on the author’s analysis of existing literature, industry examples, and professional experience. Outside experts were consulted and provided additional feedback and insights throughout the process.

Below is a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, list of the key Executive Branch actors involved in AI-driven grid modernization efforts. A detailed overview of the various roles, authorities, and ongoing efforts can be found here.

Executive Office of the President (Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)); Department of Commerce (National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)); Department of Defense (Energy, Installations, and Environment (EI&E), Defense Advanced Research projects Agency (DARPA)); Department of Energy (Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), Grid Deployment Office (GDO), Office of Critical and Emerging Technologies (CET), Office of Cybersecurity, Energy Security, and Emergency Response (CESER), Office of Electricity (OE), National Laboratories); Department of Homeland Security (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Agency (CISA)); Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC); Federal Permitting Improvement Steering Council (FPISC); Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA); National Science Foundation (NSF)

A full database of how the federal government is using AI across agencies can be found at the 2024 Federal Agency AI Use Case Inventory. A few additional examples of private sector applications, or public-private partnerships are provided below.

Grid Planning

- EPRI’s Open Power AI Consortium

- Google’s Tapestry

- Octopus Energy’s Kraken

Siting and Permitting

Operations and Reliability

- Schneider Electric’s One Digital Grid Platform

- Cammus

- Amperon

Grid Resilience

Enhancing US Power Grid by using AI to Accelerate Permitting

The increased demand for power in the United States is driven by new technologies such as artificial intelligence, data analytics, and other computationally intensive activities that utilize ever faster and power-hungry processors. The federal government’s desire to reshore critical manufacturing industries and shift the economy from service to goods production will, if successful, drive energy demands even higher.

Many of the projects that would deliver the energy to meet rising demand are in the interconnection queue, waiting to be built. There is more power in the queue than on the grid today. The average wait time in the interconnection queue is five years and growing, primarily due to permitting timelines. In addition, many projects are cancelled due to the prohibitive cost of interconnection.

We have identified six opportunities where Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to speed the permitting process.

- AI can be used to speed decision-making by regulators through rapidly analyzing environmental regulations and past decisions.

- AI can be used to identify generation sites that are more likely to receive permits.

- AI can be used to create a database of state and federal regulations to bring all requirements in one place.

- AI can be used in conjunction with the database of state regulations to automate the application process and create visibility of permit status for stakeholders.

- AI can be used to automate and accelerate interconnection studies.

- AI can be used to develop a set of model regulations for local jurisdictions to adapt and adopt.

Challenge and Opportunity

There are currently over 11,000 power generation and consumption projects in the interconnection queue, waiting to connect to the United States power grid. As a result, on average, projects must wait five years for approval, up from three years in 2010.

Historically, a large percentage of projects in the queue, averaging approximately 70%, have been withdrawn due to a variety of factors, including economic viability and permitting challenges. About one-third of wind and solar applications submitted from 2019 to 2024 were cancelled, and about half of these applications faced delays of 6 months or more. For example, the Calico Solar Project in the California Mojave Desert, with a capacity of 850 megawatts, was cancelled due to lengthy multi-year permitting and re-approvals for design changes. Increasing queue wait time is likely to increase the number of projects cancelled and delay those that are viable.

The U.S. grid added 20.2 gigawatts of utility-scale generating capacity in the first half of 2024, a 21% increase over the first half of 2023. However, this is still less power than is likely to be needed to meet increasing power demands in the U.S. Nor does it account for the retirement of generation capacity, which was 5.1 gigawatts in the first half of 2024. In addition to replacing aging energy infrastructure as it is taken offline, this new power is critically needed to address rising energy demands in the U.S. Data centers alone are increasing power usage dramatically, from 1.9% of U.S. energy consumption in 2018 to 4.4% in 2023, and with an expected consumption of at least 6.7% in 2028.

If we want to achieve the Administration’s vision of restoring U.S. domestic manufacturing capacity, a great deal of generation capacity not currently forecast will also need to be added to the grid very rapidly, far faster than indicated by the current pace of interconnections. The primary challenge that slows most power from getting onto the grid is permitting. A secondary challenge that frequently causes projects to be delayed or cancelled is interconnection costs.

Projects frequently face significant permitting challenges. Projects not only need to obtain permits to operate the generation site but must also obtain permits to move power to the point where it connects to the existing grid. Geographically remote projects may require new transmission lines that cover many miles and cross multiple jurisdictions. Even projects relatively close to the existing grid may require multiple permits to connect to the grid.

In addition, poor site selection has resulted in the cancellation of several high-profile renewable installation projects. The Battle Born Solar Project, valued at $1 billion with a 850 megawatt capacity, was cancelled after community concern that the solar farm would impact tourism and archaeological sites in the Mormon Mesa in Nevada. Another project, a 150 megawatt solar facility proposed for Culpeper County, Virginia, was denied permits for interfering with the historic site of a Civil War battle. Similarly, a geothermal plant in Nevada had to be scaled back to less than a third of its original plan after it was found to be in the only known habitat of the endangered Dixie Valley toad. While community outrage over renewable energy installations is not always avoidable, mostly due to complaints about construction impacts and misinformation, better site selection could save developers time and money by avoiding locations that encroach on historical sites, local attractions, or endangered species‘ habitats.

Projects have also historically faced cost challenges as utilities and grid operators could charge the full cost of new operating capacity to each project, even when several pending projects could utilize the same new operating assets. On July 28, 2023, FERC issued a final rule with a compliance date of March 21, 2024, that requires transmission providers to consider all projects in the queue and determine how operating assets would be shared when calculating the cost of connecting a project to the grid. However, the process for calculating costs can be cumbersome when many projects are involved.

On April 15th, 2025, the Trump Administration issued a Presidential Memorandum titled “Updating Permitting Technology for the 21st Century.” This memo directs executive departments and agencies to take full advantage of technology for environmental review and permitting processes and creates a permitting innovation center. While it is unclear how much authority the PIC will have, it demonstrates the Administration’s focus in this area and may serve as a change agent in the future. There is an opportunity to use AI to improve both the speed and the cost of connecting new projects to the grid. Below are recommendations to capitalize on this opportunity.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Funding for PNNL to expand the PolicyAI NEPA model to streamline environmental permitting processes beyond the federal level.

In 2023, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) was tasked by DOE with developing a PermitAI prototype to help regulators understand the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations and speed up project environmental reviews. PNNL data scientists created an AI-searchable database of federal impact environmental statements, composed primarily of information that was not readily available to regulators before. The database contains textual data extracted from documents across 2,917 different projects stored as 3.6 million tokens from the GPT-2 tokenizer. Tokens are the units in which text is broken down for natural language processing AI models. The entire dataset is currently publicly available via HuggingFace. The database is then used for generative-AI searching that can quickly find documents and summarize relevant results as a Large Language Model (LLM). While the development of this database is still preliminary and efficiency metrics have not yet been published, based on complaints from those involved in permitting about the complexity of the process and the lack of guidelines, this approach should be a model for tools that could be developed and provided to state and local regulators to assist with permitting reviews.

In 2021, PNNL created a similar process, without using AI, for NEPA permitting for small-to medium-sized nuclear reactors, which simplified the process and reduced the environmental review time from three to six years to between six and twenty-four months. Using AI has the potential to reduce the process exponentially for renewables permitting. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has also studied using LLMs to expedite the processing of policy data from legal documents and found the results to support the expansion of LLMs for policy database analysis, primarily when compared to the current use of manual effort.

State and local jurisdictions can use the “Updating Permitting Technology” Presidential Memorandum as guidance to support the intersection between state and local permitting efforts. The PNNL database of federal NEPA materials, trained on past NEPA cases, would be provided by PNNL to state jurisdictions as a service, through a process similar to that used by EPA to ensure that state jurisdictions do not need to independently develop data collection solutions. Ideally, the initial data analysis model would be trained to be specific to each participating state and continually updated with new material to create a seamless regulatory experience.

Since PNNL has already built a NEPA model and this work is being expanded to a multi-lab effort that includes NREL, Argonne and others The House Energy and Water development committee could appropriate additional funding to the Office of Policy (OP) or EERE (Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy) to enable the labs to expand the model and make it available to state and local regulatory agencies to integrate it into their permitting processes. States could develop models specific to their ordinances with the backbone of PNNL’s PermitAI. This effort could be expedited through engagement with the Environmental Council of the States (ECOS).

A shared database of NEPA information would reduce time spent reviewing backlogs of data from environmental review documents. State and local jurisdictions would more efficiently identify relevant information and precedent, and speed decision-making while reducing costs. An LLM tool also has the benefit of answering specific questions asked by the user. An example would be answering a question about issues that have arisen for similar projects in the same area.

Recommendation 2. Appropriate funding to expand AI site selection tools and support state and local pilots to improve permitting outcomes and reduce project cancellations.

AI could be used to identify sites that are suitable for energy generation, with different models eventually trained for utility-scale solar siting, onshore and offshore wind siting, and geothermal power plant siting. Key concerns affecting the permitting process include the loss of arable land, impacts on wildlife, and community responses, like opposition based on land use disagreements. Better site selection identifies these issues before they appear during the permitting process.

AI can access data from a range of sources, including satellite imagery from Google Earth, commercially available lidar studies, and local media screening to identify locations with the least number of potential barriers or identify and mitigate barriers for sites that have been selected. Unlike action one, which involves answering questions by pulling from large databases using LLMs, this would primarily utilize machine learning algorithms that process past and current data to identify patterns and predict outcomes, like energy generation potential. Examples of datasets these tools can use are the free, publicly available products created by the Innovative Data Energy Applications (IDEA) group in NREL’s Strategic Energy Analysis Center (SEAC), including the national solar radiation database and the wind resource database. The national solar radiation database visualizes the amount of solar energy potential at a given time and predicts future availability of solar energy for a given location in the dataset, which covers the entirety of the United States.

The wind resource database is a collection of modeled wind resource estimates for locations within the United States. In addition, Argonne National Lab has developed the GEM tool to support the NEPA reviews for transmission projects. A few start-ups have synthesized a variety of datasets like these and created their databases for information like terrain and slope to create site-selection decision-making tools. AI analysis of local news and landmarks important to local communities to identify locations that are likely to oppose renewable installations is particularly important since community opposition is often what kills renewable generation projects that have made it into the permitting process.

The House Committee for Energy and Water Development could appropriate funds to DOE’s Grid Deployment Office which could collaborate with EERE, FECM (Fossil Energy and Carbon Management), NE (Nuclear Energy) and OE (Office of Electricity) to further expand the technology specific models as well as to expand Argonne’s GEM tool. GDO could also provide grant funding to state and local government permitting authorities to pilot AI-powered site selection tools created by start-ups or other organizations. Local jurisdictions, in turn, could encourage use by developers.

Better site selection would speed permitting processes and reduce the number of cancelled projects, as well as wasted time and money by developers.

Recommendation 3. Funding for DOE labs to develop an AI-based permitting database, starting with a state-level pilot, to streamline permit site identification and application for large-scale energy projects.

Use AI to identify all of the non-environmental federal, state, and local permits required for generation projects. A pilot project, focused on one generation type, such as solar, should be launched in a state that is positioned for central coordination. New York may be the best candidate, as the Office of Renewable Energy Siting and Electric Transmission has exclusive jurisdiction over on-shore renewable energy projects of at least 25 megawatts.

A second option could be Illinois, which has statewide standards for utility-scale solar and wind facilities where local governments cannot adopt more restrictive ordinances. This would require the development of a database of regulations and the ability to query that database to provide a detailed list of required permits for each project by jurisdiction, the relevant application process, and forms. The House Energy and Water Development Committee could direct funds to EERE to support PNNL, NREL, Argonne, and other DOE labs to develop this database. Ideally, this tool would be integrated with tools developed by local jurisdictions to automate their individual permitting process.

State-level regulatory coordination would speed the approval of projects contained within a single state, as well as improve coordination between states.

Recommendation 4. Appropriate funds for DOE to develop a state-level AI permitting application to streamline renewable energy permit approvals and improve transparency.

Use AI as a tool to complete the permitting process. While it would be nearly impossible to create a national permitting tool, it would be realistic to create a tool that could be used to manage developers’ permitting processes at the state level.

NREL developed a permitting tool with funding from the DOE Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) for residential rooftop solar permitting. The tool, SolarAPP+, automates plan review, permit approval, and project tracking. As of the end of 2023, it had saved more than 33,000 hours of permitting staff time for more than 32,800 projects. However, permitting for rooftop solar is less complex than permitting for utility-scale solar sites or wind farms because of less need for environmental reviews, wildlife endangerment reviews, or community feedback. Using the AI frameworks developed by PNNL mentioned in recommendation one and leveraging the development work completed by NREL could create tools similar to SolarAPP+ for large-scale renewable installations and have similar results in projects approved and time saved. An application that may meet this need is currently under development at NREL.

The House Energy and Water Development Committee should appropriate funds for DOE to create an application through PNNL and NREL that would utilize the NREL SolarAPP+ framework that could be implemented by states to streamline the permitting application process. This would be especially helpful for complex projects that cross multiple jurisdictions. In addition, Congress, through appropriation by the House Energy and Water Development Committee to DOE’s Grid Deployment Office, could establish a grant program to support state and local level implementation of this permitting tool. This tool could include a dashboard to improve permitting transparency, one of the items required by the Presidential Memorandum on Updating Permitting Technology.

Developers are frequently unclear about what permits are required, especially for complex multi-jurisdiction projects. The AI tool would reduce the time a developer spends identifying permits and would support smaller developers who don’t have permitting consultants or prior experience. An integrated electronic permitting solution would reduce the complexity of applying for and approving permits. With a state-wide system, state and local regulators would only need to add their requirements and location-specific requirements and forms into a state-maintained system. Finally, an integrated system with a dashboard could increase status visibility and help resolve issues more quickly. These tools together would allow developers to make realistic budgets and time frames for projects to allocate resources and prioritize projects that have the greatest chance of being approved.

Recommendation 5. Direct FERC to require RTOs to evaluate and possibly implement AI tools to automate interconnection analysis processes.

Use AI tools to reduce the complexity of publishing and analyzing the mandated maps and assigning costs to projects. While FERC has mandated that grid operators consider all projects coming onto the grid when setting interconnection pricing, as well as considering project readiness rather than time in queue for project completion, the requirements are complex to implement.

A number of private sector companies have begun developing tools to model interconnections. Pearl Street has used its model to reproduce a complex and lengthy interconnection cluster study in ten days, and PJM recently announced a collaboration with Google to develop an analysis capability. Given the private sector efforts in this space, the public interest would be best served by FERC requiring RTOs to evaluate and implement, if suitable, an automated tool to speed their analysis process.

Automating parts of interconnection studies would allow developers to quickly understand the real cost of a new generation project, allowing them to quickly evaluate feasibility. It would create more cost certainty for projects and would also help identify locations where planned projects have the potential to reduce interconnection costs, attracting still more projects to share new interconnections. Conversely, the capability would also quickly identify when new projects in an area would exceed expected grid capacity and increase the costs for all projects. Ultimately, the automation would lead to more capacity on the grid faster and at a lower cost as developers optimize their investments.

Recommendation 6. Provide funding to DOE to extend the use of NREL’s AI-compiled permitting data to develop and model local regulations. The results could be used to promote standardization through national stakeholder groups.

As noted earlier, one of the biggest challenges in permitting is the complexity of varying and sometimes conflicting local regulations that a project must comply with. Several years ago, NREL, in support of the DOE Office of Policy, spent 1500 staff hours to manually compile what was believed to be a complete list of local energy permitting ordinances across the country. In 2024, NREL used an LLM to compile the same information with a 90% success rate in a fraction of the time.

The House Energy and Water Development Committee should direct DOE to fund the continued development of the NREL permitting database and evaluate that information with an LLM to develop a set of model regulations that could be promoted to encourage standardization. Adoption of those regulations could be encouraged by policymakers and external organizations through engagement with the National Governors Association, the National Association of Counties, the United States Conference of Mayors, and other relevant stakeholders.

Local jurisdictions often adopt regulations based on a limited understanding of best practices and appropriate standards. A set of model regulations would guide local jurisdictions and reduce complexity for developers.

Conclusion

As demand on the electrical grid grows, the need to speed up the availability of new generation capacity on the grid becomes increasingly urgent. The deployment of new generation capacity is slowed by challenges related to site selection, environmental reviews, permitting, and interconnection costs and wait times. While much of the increasing demand for energy in the United States can be attributed to AI, it can also be a powerful tool to help the nation meet that demand.

The six recommendations for AI to speed up the process of bringing new power to the grid that have been identified in this memo address all of those concerns. AI can be used to assist with site selection, analyze environmental regulations, help both regulators and the regulated community understand requirements, develop better regulations, streamline permitting processes, and reduce the time required for interconnection studies.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

The combined generating capacity of the projects awaiting approval is about 1,900 gigawatts, excluding ERCOT and NYISO which do not report this data. In comparison, the generating capacity of the U.S. grid as of Q4 2023 was 1,189 gigawatts. Even if the current high cancellation rate of 70% is maintained, the queue will yield an approximately 50% increase in the amount of power available on the grid through a $600B investment in US energy infrastructure.

FERC’s five-year growth forecast through 2029 predicts an increased demand for 128 gigawatts of power. In that context, the net addition of 15.1 gigawatts of power in the first half of 2024 suggests an increase of 150 gigawatts of power and little excess capacity over the five-year horizon. This forecast is predicated on the assumption that the power added to the grid does not decline, retirements do not increase, and the load forecast does not increase. All these estimates are being applied to a system where supply and demand are already so closely matched that FERC predicted supply shortages in several regions in the summer of 2024.

Construction delays and cost overruns can be an issue, but this is more frequently a factor in large projects such as nuclear and large oil and gas facilities, and is rarely a factor for wind and solar which are factory built and modular.

While the current administration has declared a National Energy Emergency to expedite approvals for energy projects, the order excludes wind, solar, and batteries, which make up 90% of the power presently in the interconnection queue as well as mirroring the mix of capacity recently added to the grid. Therefore, the expedited permitting processes required by the administration only applies to 10% of the queue, composed of 7% natural gas and 3% that includes nuclear, oil, coal, hydrogen, and pumped hydro. Since solar, wind, and batteries are unlikely to be granted similar permitting relief, and relying on as-yet unplanned fossil fuel projects to bring more energy to the grid is not realistic, other methods must be undertaken to speed new power to the grid.

Transform Communities By Adaptive Reuse of Legacy Coal Infrastructure to Support AI Data Centers

The rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and the corresponding hyperscale data centers that support it present a challenge for the United States. Data centers intensify energy demand, strain power grids, and raise environmental concerns. These factors have led developers to search for new siting opportunities outside traditional corridors (i.e., regions with longstanding infrastructure and large clusters of data centers), such as Silicon Valley and Northern Virginia. American communities that have historically relied on coal to power their local economies have an enormous opportunity to repurpose abandoned coal mines and infrastructure to site data centers alongside clean power generation. The decline of the coal industry in the late 20th century led to the abandonment of coal mines, loss of tax revenues, destruction of good-paying jobs, and the dismantling of the economic engine of American coal communities, primarily in the Appalachian, interior, and Western coal regions. The AI boom of the 21st century can reinvigorate these areas if harnessed appropriately.

The opportunity to repurpose existing coal infrastructure includes Tribal Nations, such as the Navajo, Hopi, and Crow, in the Western Coal regions. These regions hold post-mining land with potential for economic development, but operate under distinct governance structures and regulatory frameworks administered by Tribal governments. A collaborative approach involving Federal, State, and Tribal governments can ensure that both non-tribal and Tribal coal regions share in the economic benefits of data center investments, while also promoting the transition to clean energy generation by collocating data centers with renewable, clean energy-powered microgrids.

This memo recommends four actions for coal communities to fully capitalize on the opportunities presented by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI).

- Establish a Federal-State-Tribal Partnership for Site Selection, Utilizing the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Program.

- Develop a National Pilot Program to Facilitate a GIS-based Site Selection Tool

- Promote collaboration between states and utility companies to enhance grid resilience from data centers by adopting plug-in and flexible load standards.

- Lay the groundwork for a knowledge economy centered around data centers.

By pursuing these policy actions, states like West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky, as well as Tribal Nations, can lead America’s energy production and become tech innovation hubs, while ensuring that the U.S. continues to lead the AI race.

Challenge and Opportunity

Energy demands for AI data centers are expected to rise by between 325 and 580 TWh by 2028, roughly the amount of electricity consumed by 30 to 54 million American households annually. This demand is projected to increase data centers’ share of total U.S. electricity consumption to between 6.7% and 12.0% by 2028, according to the 2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report by the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. According to the same report, AI data centers also consumed around 66 billion liters of water for cooling in 2023. By 2028, that number is expected to be between 60 and 124 billion litres for hyperscale data centers alone. (Hyperscale data centers are massive warehouses of computer servers, powered by at least 40 MW of electricity, and run by major cloud companies like Amazon, Google, or Microsoft. They serve a wide variety of purposes, including Artificial intelligence, automation, data analytics, etc.)

Future emissions are also expected to grow with increasing energy usage. Location has also become important; tech companies with AI investments have increasingly recognized the need for more data centers in different places. Although most digital activities are traditionally centered around tech corridors like Silicon Valley and Northern Virginia, the need for land and considerations of carbon emissions footprints in these places make the case for expansion to other sites.

Coal communities have experienced a severe economic decline over the past decade, as coal severance and tax revenues have plummeted. West Virginia, for example, reported an 83% decline in severance tax collections in fiscal year 2024. Competition from natural gas and renewable energy sources, slow growth in energy demand, and environmental concerns have led to coal often being viewed as a backup option. This has led to low demand for coal locally, and thus a decrease in severance, property, sales, and income taxes.

The percentage of the coal severance tax collected that is returned to the coal-producing counties varies by state. In West Virginia, the State Tax Commissioner collects coal severance taxes from all producing counties and deposits them in the State Treasurer’s office. Seventy-five percent of the net proceeds from the taxes are returned to the coal-producing counties, while the remaining 25% is distributed to the rest of the state. Historically, these tax revenues have usually funded a significant portion of county budgets. For counties like Boone in West Virginia and Campbell County in Wyoming, once two of America’s highest coal-producing counties, these revenues helped maintain essential services and school districts. Property taxes and severance taxes on coal funded about 24% of Boone’s school budget, while 59% of overall property valuations in Campbell county in 2017 were coal mining related. With those tax bases eroding, these counties have struggled to maintain schools and public services.

Likewise, the closure of the Kayenta Mine and the Navajo Generating Station resulted in the elimination of hundreds of jobs and significant public revenue losses for the Navajo and Hopi Nations. The Crow Nation, like many other Native American tribes with coal, is reliant on coal leases with miners for revenue. They face urgent infrastructure gaps and declining fiscal capacity since their coal mines were shut down. These tribal communities, with a rich legacy of land and infrastructure, are well-positioned to lead equitable redevelopment efforts if they are supported appropriately by state and federal action.

These communities now have a unique opportunity to attract investments in AI data centers to generate new sources of revenue. Investments in hyperscale data centers will revive these towns through revenue from property taxes, land reclamation, and investments in energy, among other sources. For example, data centers in Northern Virginia, commonly referred to as the “Data Center Alley,” have contributed an estimated 46,000 jobs and up to $10 billion in economic impact to the state’s economy, according to an economic impact report on data centers commissioned by the Northern Virginia Technology Council.

Coal powered local economies and served as the thread holding together the social fabric of communities in parts of Appalachia for decades. Coal-reliant communities also took pride in how coal powered most of the U.S.’s industrialization in the nineteenth century. However, many coal communities have been hollowed out, with thousands of abandoned coal mines and tens of thousands of lost jobs. By inviting investments in data centers and new clean energy generation, these communities can be economically revived. This time, their economies will be centered on a knowledge base, representing a shift from an extraction-based economy to an information-based one. Data centers attract new AI- and big-data-focused businesses, which reinvigorates the local workforce, inspires research programs at nearby academic institutions, and reverses the brain drain that has long impacted these communities.

The federal government has made targeted efforts to repurpose abandoned coal mines. The Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Program, created under the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA) of 1977, reclaims lands affected by coal mining and stabilizes them for safe reuse. Building on that, Congress established the Abandoned Mine Land Economic Revitalization (AMLER) Program in 2016 to support the economic redevelopment of reclaimed sites in partnership with state and tribal governments. AMLER sites are eligible for flexible reuse for siting hyperscale AI data centers. Those with flat terrains and legacy infrastructure are particularly desirable for reuse. The AMLER program is supported by a fee collected from active coal mining operations – a fee that has decreased as coal mining operations have ceased – and has also received appropriated Congressional funding since 2016. Siting data centers on AMLER sites can circumvent any eminent domain concerns that arise with project proposals on private lands.

In addition to the legal and logistical advantages of siting data centers on AMLER sites, many of these locations offer more than just reclaimed land; they retain legacy infrastructure that can be strategically repurposed for other uses. These sites often lie near existing transmission corridors, rail lines, and industrial-grade access roads, which were initially built to support coal operations. This makes them especially attractive for rapid redevelopment, reducing the time and cost associated with building entirely new facilities. By capitalizing on this existing infrastructure, communities and investors can accelerate project timelines and reduce permitting delays, making AMLER sites not only legally feasible but economically and operationally advantageous.

Moreover, since some coal mines are built near power infrastructure, there exist opportunities for federal and state governments to allow companies to collocate data centers with renewable, clean energy-powered microgrids, thereby preventing strain on the power grid. These sites present an opportunity for data centers to:

- Host local microgrids for energy load balancing and provide an opportunity for net metering;

- Develop a model that identifies places across the United States and standardizes data center site selection;

- Revitalize local economies and communities;

- Invest in clean energy production; and,

- Create a knowledge economy outside of tech corridors in the United States.

Precedents for collocating new data centers at existing power plants already exist. In February 2025, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) reviewed potential sites within the PJM Interconnection region to host these pairings. Furthermore, plans to repurpose decommissioned coal power stations as data centers exist in the United States and Europe. However, there remains an opportunity to utilize the reclaimed coal mines themselves. They provide a readily available location with proximity to existing transmission lines, substations, roadways, and water resources. Historically, they also have a power plant ecosystem and supporting infrastructure, meaning minimal additional infrastructure investment is needed to bring them up to par.

Plan of Action

The following recommendations will fast-track America’s investment in data centers and usher it into the next era of innovation. Collaboration among federal agencies, state governments, and tribal governments will enable the rapid construction of data centers in historically coal-reliant communities. Together, they will bring prosperity back to American communities left behind after the decline in the coal industry by investing in their energy capacities, economies, and workforce.

Recommendation 1. Establish a Federal-State-Tribal Partnership for Site Selection, Utilizing the Department of the Interior’s (DOI) Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Program.

The first step in investing in data centers in coal communities should be a collaborative effort among federal, state, and tribal governments to identify and develop data center pilot sites on reclaimed mine lands, brownfields, and tribal lands. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Department of the Interior (DOI) should jointly identify eligible sites with intact or near-intact infrastructure, nearby energy generation facilities, and broadband corridors, utilizing the Abandoned Mine Land (AML) Reclamation Program and the EPA Brownfields Program. Brownfields with legacy infrastructure should also be prioritized to reduce the need for greenfield development. Where tribal governments have jurisdiction, they should be engaged as co-developers and beneficiaries of data centers, with the right to lead or co-manage the process, including receiving tax benefits from the project. Pre-law AMLs (coal mines that were abandoned before August 3, 1977, when the SMCRA became law) offer the most flexibility in regulations and should be prioritized. Communities will be nominated for site development based on economic need, workforce readiness, and redevelopment plans.

State governments and lawmakers will nominate communities from the federally identified shortlist based on economic need, workforce readiness and mobility, and redevelopment plans.

Recommendation 2. Develop a National Pilot Program to Facilitate a GIS-based Site Selection Tool

In partnership with private sector stakeholders, the DOE National Labs should develop a pilot program for these sites to inform the development of a standardized GIS-based site selection tool. This pilot would identify and evaluate a small set of pre-law AMLs, brownfields, and tribal lands across the Appalachian, Interior, and Western coal regions for data center development.

The pilot program will assess infrastructure readiness, permitting pathways, environmental conditions, and community engagement needs across all reclaimed lands and brownfields and choose those that meet the above standards for the pilot. Insights from these pilots will inform the development of a scalable tool that integrates data on grid access, broadband, water, land use, tax incentives, and workforce capacity.

The GIS tool will equip governments, utilities, and developers with a reliable, replicable framework to identify high-potential data center locations nationwide. For example, the Geospatial Energy Mapper (GEM), developed by Argonne National Laboratory with support from the U.S. Department of Energy, offers a public-facing tool that integrates data on energy resources, infrastructure, land use, and environmental constraints to guide energy infrastructure siting.

The DOE, working in coordination with agencies such as the Department of the Treasury, the Department of the Interior, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and state economic development offices, should establish targeted incentives to encourage data center companies to join the coalition. These include streamlined permitting, data confidentiality protections, and early access to pre-qualified sites. Data center developers, AI companies, and operators typically own the majority of the proprietary operational and siting data for data centers. Without incentives, this data will be restricted to private industry, hindering public-sector planning and increasing geographic inequities in digital infrastructure investments.

By leveraging the insights gained from this pilot and expanding access to critical siting data, the federal government can ensure that the benefits of AI infrastructure investments are distributed equitably, reaching communities that have historically powered the nation’s industrial growth but have been left behind in the digital economy. A national site selection tool grounded in real-world conditions, cross-agency coordination, and private-public collaboration will empower coal-impacted communities, including those on Tribal lands and in remote Appalachian and Western regions, to attract transformative investment. In doing so, it will lay the foundation for a more inclusive, resilient, and spatially diverse knowledge economy built on reclaimed land.

Recommendation 3. Promote collaboration between states and utility companies to enhance grid resilience from data centers by adopting plug-in and flexible load standards.

Given the urgency and scale of hyperscale data center investments, state governments, in coordination with Public Utility Commissions (PUCs), should adopt policies that allow temporary, curtailable, and plug-in access to the grid, pending the completion of colocated, preferably renewable, energy microgrids in proposed data centers. This plug-in could involve approving provisional interconnection services for large projects, such as data centers. This short-term access is critical for communities to realize immediate financial benefits from data center construction while long-term infrastructure is still being developed. Renewable-powered on-site microgrids for hyperscale data centers typically exceed 100–400 MW per site and require deployment times of up to three years.

To protect consumers, utilities and data center developers must guarantee that any interim grid usage does not raise electricity rates for households or small businesses. The data center and/or utility should bear responsibility for short-term demand impacts through negotiated agreements.

In exchange for interim grid access, data centers must submit detailed grid resilience plans that include:

- A time-bound schedule (typically 18–36 months) for deploying an on-site microgrid, preferably powered by renewable energy.

- On-site battery storage systems and demand response capabilities to smooth load profiles and enhance reliability.

- Participation in net metering to enable excess microgrid energy to be sold back to the grid, benefiting local communities.

Additionally, these facilities should be treated as large, flexible loads capable of supporting grid stability by curtailing non-critical workloads or shifting demand during peak periods. Studies suggest that up to 126 GW of new data center load could be integrated into the U.S. power system with minimal strain if such facilities allow as little as 1% curtailment time (when data centers reduce or pause their electricity usage by 1% of their annual electricity usage).

States can align near-term economic gains with long-term energy equity and infrastructure sustainability by requiring early commitment to microgrid deployment and positioning data centers as flexible grid assets (see FAQs for ideas on water cooling for the data centers).

Recommendation 4. Lay the groundwork for a knowledge economy centered around data centers.

The DOE Office of Critical and Emerging Technologies (CET), in coordination with the Economic Development Administration (EDA), should conduct an economic impact assessment of data center investments in coal-reliant communities. To ensure timely reporting and oversight, the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and the House Committee on Energy and Commerce should guide and shape the reports’ outcomes, building on President Donald Trump’s executive order to pass legislation on AI education. Investments in data centers offer knowledge economies as an alternative to extractive economies, which have relied on selling fossil fuels, such as coal, that have failed these communities for generations.

A workforce trained in high-skilled employment areas such as AI data engineering, data processing, cloud computing, advanced digital infrastructure, and cybersecurity can participate in the knowledge economy. The data center itself, along with new business ecosystems built around it, will provide these jobs.

Counties will also generate sustainable revenue through increased property taxes, utility taxes, and income taxes from the new businesses. This new revenue will replace the lost revenue from the decline in coal over the past decade. This strategic transformation positions formerly coal-dependent regions to compete in a national economy increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence, big data, and digital services.

This knowledge economy will also benefit nearby universities, colleges, and research institutes by creating research partnership opportunities, developing workforce pipelines through new degree and certificate programs, and fostering stronger innovation ecosystems built around digital infrastructure.

Conclusion

AI is growing rapidly, and data centers are following suit, straining our grid and requiring new infrastructure. Coal-reliant communities possess land and energy assets, and they have a pressing need for economic renewal. With innovative federal-state coordination, we can repurpose abandoned mine lands, boost local tax bases, and build a knowledge economy where coal once dominated. These two pressing challenges—grid strain and post-coal economic decline—can be addressed through a unified strategy: investing in data centers on reclaimed coal lands.

This memo outlines a four-part action plan. First, federal and state governments must collaborate to prepare abandoned mine lands for data center development. Second, while working with private industry, DOE National Labs should develop a standardized, GIS-based site selection tool to guide smart, sustainable investments. Third, states should partner with utilities to allow temporary grid access to data centers, while requiring detailed microgrid-based resilience plans to reduce long-term strain. Fourth, policymakers must lay the foundation for a knowledge economy by assessing the economic impact of these investments, fostering partnerships with local universities, and training a workforce equipped for high-skilled roles in digital infrastructure.

This is not just an energy strategy but also a sustainable economic revitalization strategy. It will transform coal assets that once fueled America’s innovation in the 19th century into assets that will fuel America’s innovation in the 21st century. The energy demands of data centers will not wait; the economic revitalization of Appalachian communities, heartland coal communities, and the Mountain West coal regions cannot wait. The time to act is now.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

There is no direct example yet of data center companies reclaiming former coal mines. However, some examples show the potential. For instance, plans are underway to transform an abandoned coal mine in Wise County, Virginia, into a solar power station that will supply a nearby data center.

Numerous examples from the U.S. and abroad exist of tech companies collocating data centers with energy-generating facilities to manage their energy supply and reduce their carbon footprint. Meta signed a long-term power-purchase agreement with Sage Geosystems for 150 MW of next-generation geothermal power in 2024, enough to run multiple hyperscale data centers. The project’s first phase is slated for 2027 and will be located east of the Rocky Mountains, near Meta’s U.S. data center fleet.

Internationally, Facebook built its Danish data center into a district heating system, utilizing the heat generated to supply more than 7,000 homes during the winter. Two wind energy projects power this data center with 294 MW of clean energy.

Yes! Virginia, especially Northern Virginia, is a leading hub for data centers, attracting significant investment and fostering a robust tech ecosystem. In 2023, new and expanding data centers accounted for 92% of all new investment announced by the Virginia Economic Development Partnership. This growth supports over 78,000 jobs and has generated $31.4 billion in economic output, a clear sign of the job creation potential of the tech industry. Data centers have attracted supporting industries, including manufacturing facilities for data center equipment and energy monitoring products, further bolstering the state’s knowledge economy.

AMLER funds are federally restricted to use on or adjacent to coal mines abandoned before August 3, 1977. However, some of these pre-1977 sites—especially in Appalachia and the West—are not ideal for economic redevelopment due to small size, steep slopes, or flood risk. In contrast, post-1977 mine sites that have completed reclamation (SMCRA Phase III release) are more suitable for data centers due to their flat terrain, proximity to transmission lines, and existing utilities. Yet, these sites are not currently eligible for AMLER funding. To fully unlock the economic potential of coal communities, federal policymakers should consider expanding AMLER eligibility or creating a complementary program that supports the reuse of reclaimed post-1977 mine lands, particularly those that are already prepared for industrial use.

Brownfields are previously used industrial or commercial properties, such as old factories, decommissioned coal-fired power plants, rail yards, and mines, whose reuse is complicated by real or suspected environmental contamination. By contrast, Greenfields are undeveloped acreage that typically requires the development of new infrastructure and land permitting from scratch. Brownfields offer land developers and investors faster access to existing zoning, permitting, transportation infrastructure, and more.

Since 1995, the EPA Brownfields Program has offered competitive grants and revolving loan funds for assessing, cleaning up, and training for jobs at Brownfield sites, transforming liabilities into readily available assets. A study estimated that every federal dollar spent by the EPA in 2018 leveraged approximately $16.86 in follow-on capital and created 8.6 jobs for every $100,000 of grant money. In 2024, the Agency added another $300 million to accelerate projects in disadvantaged communities.

In early 2025, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) issued a Request for Information (RFI) seeking input on siting artificial intelligence and data infrastructure on DOE-managed federal lands, including National Labs and decommissioned sites. This effort reflects growing federal interest in repurposing publicly-owned sites to support AI infrastructure and grid modernization. Like the approach recommended in this memo, the RFI process recognizes the need for multi-level coordination involving federal, state, tribal, and local governments to assess land readiness, streamline permitting, and align infrastructure development with community needs. Lessons from that process can help guide broader efforts to repurpose pre-law AMLs, brownfields, and tribal lands for data center investment.

Yes, by turning a flooded mine into a giant underground cooler. Abandoned seams in West Virginia hold water that remains at a steady temperature of ~50–55°F (10–13°C). A Marshall University study logged 54°F mine-pool temperatures and calculated that closed-loop heat exchangers can reduce cooling power enough to achieve paybacks in under five years. The design lifts the cool mine water to the servers in the data centers, absorbs heat from the servers, and then returns the warmed water underground, so the computer hardware side never comes into contact with raw mine water. The approach is already being commercialized: Virginia’s “Data Center Ridge” project secured $3 million in AMLER funds, plus $1.5 million from DOE, to cool 36 MW blocks with up to 10 billion gallons of mine water held at a temperature of below 55°F.

Moving Beyond Pilot Programs to Codify and Expand Continuous AI Benchmarking in Testing and Evaluation

Rapid and advanced AI integration and diffusion within the Department of Defense (DoD) and other government agencies has emerged as a critical national security priority. This convergence of rapid AI advancement and DoD prioritization creates an urgent need to ensure that AI models integrated into defense operations are reliable, safe, and mission-enhancing. For this purpose, the DoD must deploy and expand one of its most critical tools available within its Testing and Evaluation (T&E) process: benchmarking—the structured practice of applying shared tasks and metrics to compare models, track progress, and expose performance gaps.

A standardized AI benchmarking framework is critical for delivering uniform, mission-aligned evaluations across the DoD. Despite their importance, the DoD currently lacks standardized, enforceable AI safety benchmarks, especially for open-ended or adaptive use cases. A shift from ad hoc to structured assessments will support more informed, trusted, and effective procurement decisions.

Particularly at the acquisition stage for AI models, rapid DoD acquisition platforms such as Tradewinds can serve as the policy vehicle for enabling more robust benchmarking efforts. This can be done with the establishment of a federally coordinated benchmarking hub, spearheaded by a coordinated effort between the Chief Data and Artificial Intelligence Officer (CDAO) and Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) in consultation with the newly established Chief AI Officer’s Council (CAIOC) of the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

Challenge and Opportunity

Experts at the intersection of both AI and defense, such as the retired Lieutenant General John (Jack) N.T. Shanahan, have emphasized the profound impact of AI on the way the United States will fight future wars – with the character of war continuously reshaped by AI’s diffusion across all domains. The DoD is committed to remaining at the forefront of these changes: between 2022-2023, the value of federal AI contracts increased by over 1200%, with the surge driven by increases in DoD spending. Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth has pledged increased investment in AI specifically for military modernization efforts, and has tasked the Army to implement AI in command and control across the theater, corps, and division headquarters by 2027–further underscoring AI’s transformative impact on modern warfare.

Strategic competitors—especially the People’s Republic of China—are rapidly integrating AI into their military and technological systems. The Chinese Communist Party views AI-enabled science and technology as central to accelerating military modernization and achieving global leadership. At this pivotal moment, the DoD is pushing to adopt advanced AI across operations to preserve the U.S. edge in military and national security applications. Yet, accelerating too quickly without proper safeguards risks exposing vulnerabilities adversaries could exploit.

With the DoD at a unique inflection point, it must balance the rapid adoption and integration of AI into its operations with the need for oversight and safety. DoD needs AI systems that consistently meet clearly defined performance standards set by acquisition authorities, operate strictly within the scope of their intended use, and do not exhibit unanticipated or erratic behaviors under operational conditions. These systems can deliver measurable value to mission outcomes while fostering trust and confidence among human operators through predictability, transparency, and alignment with mission-specific requirements.

AI benchmarks are standardized tasks and metrics that systematically measure a model’s performance, reliability, and safety, and have increasingly been adopted as a key measurement tool by the AI industry. Currently, DoD lacks standardized, comprehensive AI safety benchmarks, especially for open-ended or adaptive use cases. Without these benchmarks, the DoD risks acquiring models that underperform, deviate from mission requirements, or introduce avoidable vulnerabilities, leading to increased operational risk, reduced mission effectiveness, and costly contract revisions.

A recent report from the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) on best practices for AI T&E outlined that the rapid and unpredictable pace of AI advancement presents distinctive challenges for both policymakers and end-users. The accelerating pace of adoption and innovation heightens both the urgency and complexity of establishing effective AI benchmarks to ensure acquired models meet the mission-specific performance standards required by the DoD and the services.