Crowd-Sourcing the Treaty Verification Problem

Verification of international treaties and arms control agreements such as the pending Iran nuclear deal has traditionally relied upon formal inspections backed by clandestine intelligence collection.

But today, the widespread availability of sensors of many types complemented by social media creates the possibility of crowd-sourcing the verification task using open source data.

“Never before has so much information and analysis been so widely and openly available. The opportunities for addressing future [treaty] monitoring challenges include the ability to track activity, materials and components in far more detail than previously, both for purposes of treaty verification and to counter WMD proliferation,” according to a recent study from the JASON defense science advisory panel. See Open and Crowd-Sourced Data for Treaty Verification, October 2014.

“The exponential increase in data volume and connectivity, and the relentless evolution toward inexpensive — therefore ubiquitous — sensors provide a rapidly changing landscape for monitoring and verifying international treaties,” the JASONs said.

Commercial satellite imagery, personal radiation detectors, seismic monitors, cell phone imagery and video, and other collection devices and systems combine to create the possibility of Public Treaty Monitoring, or PTM.

“The public unveiling and confirmation of the Natanz nuclear site in Iran was an important early example of PTM,” the report said. “In December 2002, the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), an independent policy institute in Washington, DC, released commercial satellite images of Natanz, and based on these images assessed it to be a gas-centrifuge plant for uranium isotope separation, which turned out to be correct.”

An earlier archetype of public arms control monitoring was the joint verification project initiated in the late 1980s by the Natural Resources Defense Council, the Federation of American Scientists and the Soviet Academy of Sciences to devise acceptable methods for verifying deep reductions in nuclear weapons. The NRDC actually installed seismic monitors around Soviet nuclear test sites.

In the 1990s, John Pike’s Public Eye project pioneered the use of declassified satellite images and newly available commercial imagery for public interest applications.

Recently, among many other examples, commercial satellite imagery has been used to track development of China’s submarine fleet, as discussed in this report by Hans Kristensen of FAS.

Jeffrey Lewis and his colleagues associated with the Armscontrolwonk.com website are regularly using satellite imagery and related analytic tools to advance public understanding of international military programs.

“The reason that open source data gathering [for treaty verification] is an easier problem is that, increasingly, at least some of it will happen as a matter of course,” the JASONs said. More and more people carry mobile phones, are connected to the Internet, and actively use social media. Even with no specific effort to create incentives or crowd-sourcing mechanisms there is likely to be a wealth of images and sensor data publicly and freely shared from practically every country and region in the world.”

The flood of open source data naturally does not solve all verification problems. Much of the data collected may be of poor quality, and some of it may be erroneous or even deliberately deceptive.

There are “enormous difficulties still to be faced and work to be done before claiming confidence in the reliability of data obtained from open sources,” the JASON report said.

“The validity of the original data is especially problematic with social media, in that eyewitnesses are notoriously unreliable (especially when reporting on unanticipated or extreme events) and there can be strong reinforcement of messages — whether true or not — when a topic ‘goes viral’ on the Internet.”

“In addition to such errors, taken here to be honest mistakes and limitations of sensors, there is the possibility of willful deception and spoofing of the raw data, including through conscious insertion or duplication of false information.”

“Key to validating the findings of open sources will be confirming the independence of two or more of the sources. Multi-reporting — ‘retweeting’ — or posting of the same information is no substitute for establishing credibility.”

On the other hand, the frequent repetition of information “can provide an indication of importance or urgency… The occurrence of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake was first noted in the United States as an anomalous increase in text-messaging.” Because the information moved at near light speed, it arrived before the seismic waves could reach US seismic stations.

“Commercial satellites have also provided valuable data for analysis of (non-)compliance with the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and open sources proved valuable in detecting the use of chemical weapons in Aleppo, and in subsequent steps to remove such weapons from Syria. They also informed the world about the Russian troop movements and threats to Ukraine.”

While the US Government should take steps to promote and exploit open source data collection, the report said, it should do so cautiously. “It is crucial that citizens or groups not be put at risk by encouraging open-source activities that might be interpreted as espionage. The line between open source sensors and ‘spy gear’ is thin.”

In short, the JASON report concluded, “Rapid advances in technology have led to the global proliferation of inexpensive, networked sensors that are now providing significant new levels of societal transparency. As a result of the increase in quality, quantity, connectivity and availability of open information and crowd-sourced analysis, the landscape for verifying compliance with international treaties has been greatly broadened.”

* * *

Among its recommendations, the JASON report urged the government to “promote transparency and [data] validation by… keeping open-source information and analysis open to the maximum degree possible and appropriate.”

Within the U.S. intelligence community, such transparency has notably been embraced by the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency under its director Robert Cardillo.

But the Central Intelligence Agency has chosen to move in the opposite direction by shutting off much of the limited public access to open source materials that previously existed. Generations of non-governmental analysts who were raised on products of the Foreign Broadcast Information Service now must turn elsewhere, since CIA terminated public access to the DNI Open Source Center in 2013.

FAS has asked the Obama Administration to restore and increase public access to open source analyses from the DNI Open Source Center as part of the forthcoming Open Government National Action Plan.

Obama Administration Releases New Nuclear Warhead Numbers

By Hans M. Kristensen

In a speech to the Review Conference of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in New York earlier today, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry disclosed new information about the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile.

Updated Stockpile Numbers

First, Kerry updated the DOD nuclear stockpile history by declaring that the stockpile as of September 2014 included 4,717 nuclear warheads. That is a reduction of 87 warheads since September 2013, when the DOD stockpile included 4,804 warheads, or a reduction of about 500 warheads retired since President Obama took office in January 2009.

The September 2014 number of 4,717 warheads is 43 warheads off the estimate we made in our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook in March this year.

Disclosure of Dismantlement Queue

Second, Kerry also announced a new number we have never seen in public before: the official number of retired nuclear warheads in line for dismantlement. As of September 2014, the United States had approximately 2,500 additional warheads that have been retired (but are still relatively intact) and awaiting dismantlement.

The number of “approximately 2,500” retired warheads awaiting dismantlement is close to the 2,340 warheads we estimated in the FAS Nuclear Notebook in March 2015.

Increasing Warhead Dismantlements

Kerry also announced that the administration “will seek to accelerate the dismantlement of retired nuclear warheads by 20 percent.”

“Over the last 20 years alone, we have dismantled 10,251 warheads,” Kerry announced.

This updates the count of 9,952 dismantled warheads from the 2014 disclosure, which means that the administration between September 2013 and September 2014 dismantled 299 retired warheads.

Under current plans, of the “approximately 2,500” warheads in the dismantlement queue, the ones that were retired through (September) 2009 will be dismantled by 2022. Additional warheads retired during the past five years will take longer.

How the administration will accelerate dismantlement remains to be seen. The FY2016 budget request for NNSA pretty much flatlines funding for weapons dismantlement and disposition through 2020. In the same period, the administration plans to complete production of the W76-1 warhead, begin production of the B61-12, and carry out refurbishments of four other warheads. If the administration wanted to dismantle all “approximately 2,500” retired warheads by 2022 (including those warheads retired after 2009), it would have to dismantle about 312 warheads per year – a rate of only 13 more than it dismantled in 2014. So this can probably be done with existing capacity.

Implications

Secretary Kerry’s speech is an important diplomatic gesture that will help the United States make its case at the NPT review conference that it is living up to its obligations under the treaty. Some will agree, others will not. The nuclear-weapon states are in a tough spot at the NPT because there are currently no negotiations underway for additional reductions; because the New START Treaty, although beneficial, is modest; and because the nuclear-weapon states are reaffirming the importance of nuclear weapons and modernizing their nuclear arsenals as if they plan to keep nuclear weapons indefinitely (see here for worldwide status of nuclear arsenals).

And the disclosure is a surprise. As recently as a few weeks ago, White House officials said privately that the United States would not be releasing updated nuclear warhead numbers at the NPT conference. Apparently, the leadership decided last minute to do so anyway. [Update: another White House official says the release was cleared late but that it had been the plan to release some numbers all along.]

The roughly 500 warheads cut from the stockpile by the Obama administration is modest and a disappointing performance by a president that has spoken so much about reducing the numbers and role of nuclear weapons. Unfortunately, the political reality has been an arms control policy squeezed between a dismissive Russian president and an arms control-hostile U.S. Congress.

In addition to updating the stockpile history, the most important part of the initiative is the disclosure of the number of weapons awaiting dismantlement. This is an important new transparency initiative by the administration that was not included in the 2010 or 2014 stockpile transparency initiatives. Disclosing dismantlement numbers helps dispel rumors that the United States is hiding a secret stash of nuclear warheads and enables the United States to demonstrate actual dismantlement progress.

And, besides, why would the administration not want to disclose to the NPT conference how many warheads it is actually working on dismantling? This can only help the United States at the NPT review conference.

There will be a few opponents of the transparency initiative. Since they can’t really say this harms U.S. national security, their primary argument will be that other nuclear-armed states have so far not response in kind.

Russia and China have not made public disclosures of their nuclear warhead inventories. Britain and France has said a little on a few occasions about their total inventories and (in the case of Britain) how many warheads are operationally available or deployed, but not disclosed the histories of stockpiles or dismantlement. And the other nuclear-armed states that are outside the NPT (India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan) have not said anything at all.

But this is a work in progress. It will take a long time to persuade other nuclear-armed states to become more transparent with basic information about nuclear arsenals. But seeing that it can be done without damaging national security and at the same time helping the NPT process is important to cut through old-fashioned excessive nuclear secrecy and increase nuclear transparency. Hat tip to the Obama administration.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Treaty Count: Russia Dips Below US Again

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian deployed strategic warheads counted by the New START Treaty once again slipped below the U.S. force level, according to the latest fact sheet released by the State Department.

The so-called aggregate numbers show that Russia as of March 1, 2015 deployed 1,582 warheads on 515 strategic launchers.

The U.S. count was 1,597 warheads on 785 launchers.

Back in September 2014, the Russian warhead count for the first time in the treaty’s history moved above the U.S. warhead count. The event caused U.S. defense hawks to say it showed Russia was increasing it nuclear arsenal and blamed the Obama administration. Russian news media gloated Russia had achieved “parity” with the United States for the first time.

Of course, none of that was true. The ups and downs in the aggregate data counts are fluctuations caused by launchers moving in an out of overhaul and new types being deployed while old types are being retired. The fact is that both Russia and the United States are slowly – very slowly – reducing their deployed forces to meet the treaty limits by February 2018.

New START Count, Not Total Arsenals

And no, the New START data does not show the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States, only the portion of them that is counted by the treaty.

While New START counts 1,582 Russian deployed strategic warheads, the country’s total warhead inventory is much higher: an estimated 7,500 warheads, of which 4,500 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The United States is listed with 1,597 deployed strategic warheads, but actually possess an estimated 7,100 warheads, of which about 4,760 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The two countries only have to make minor adjustments to their forces to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads by February 2018.

Launcher Disparity

The launchers (ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) are a different matter. Russia has been far below the treaty limit of 700 deployed launchers since before the treaty entered into effect in 2011. Despite the nuclear “build-up” alleged by some, Russia is currently counted as deploying 515 launchers – 185 launchers below the treaty limit.

In other words, Russia doesn’t have to reduce any more launchers under New START. In fact, it could deploy an additional 185 nuclear missiles over the next three years and still be in compliance with the treaty.

The United States is counted as deploying 785 launchers, 270 more than Russia. The U.S. has a surplus in all three legs of its strategic triad: bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs. To get down to the 700 launchers, the U.S. Air Force will have to destroy empty ICBM silos, dismantle nuclear equipment from excess B-52H bombers, and the U.S. Navy will reduce the number of launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 20.

In 2015 the U.S. Navy will begin reducing the number of missile tubes from 24 to 20 on each SSBN, three of which are seen in this July 2014 photo at Kitsap Naval Submarine Base at Bangor (WA). The image also shows construction underway of a second Trident Refit Facility (coordinates: 47.7469°, -122.7291°). Click image for full size,

Even when the treaty enters into force in 2018, a considerable launcher disparity will remain. The United States plans to have the full 700 deployed launchers. Russia’s plans are less certain but appear to involve fewer than 500 deployed launchers.

Russia is compensating for this disparity by transitioning to a posture with a greater share of the ICBM force consisting of MIRVed missiles on mobile launchers. This is bad for strategic stability because a smaller force with more warheads on mobile launchers would have to deploy earlier in a crisis to survive. Russia has already begun to lengthen the time mobile ICBM units deploy away from their garrisons.

Modernization of mobile ICBM garrison base at Nizhniy Tagil in the Sverdlovsk province in Central Russia. The garrison is upgrading from SS-25 to SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) (coordinates: 58.2289°, 60.6773°). Click image for full size.

It seems obvious that the United States and Russia will have to do more to cut excess capacity and reduce disparity in their nuclear arsenals.

The INF Crisis: Bad Press and Nuclear Saber Rattling

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian online news paper Vzglaid is carrying a story that wrongly claims that I have said a Russian flight-test of an INF missile would not be a violation of the INF Treaty as long as the missile is not in production or put into service.

That is of course wrong. I have not made such a statement, not least because it would be wrong. On the contrary, a test-launch of an INF missile would indeed be a violation of the INF Treaty, regardless of whether the missile is in production or deployed.

Meanwhile, US defense secretary Ashton Carter appears to confirm that the ground-launched cruise missile Russia allegedly test-launched in violation of the INF Treaty is a nuclear missile and threatens further escalation if it is deployed.

Background

The error appears to have been picked up by Vzglaid (and apparently also sputniknews.com, although I haven’t been able to find it yet) from an article that appeared in a Politico last Monday. Squeezed in between two quotes by me, the article carried the following paragraph: “And as long as Russia’s new missile is not deployed or in production, it technically has not violated the INF.” Politico did not explicitly attribute the statement to me, but Vzglaid took it one step further:

According to Hans Kristensen, a member of the Federation of American Scientists, from a technical point of view, even if the Russian side and tests a new missile, it is not a breach of the contract as long as it does not go into production and will not be put into service.

Again, I didn’t say that; nor did Politico say that I said that. Politico has since removed the paragraph from the article, which is available here.

The United States last year officially accused Russia of violating the INF Treaty by allegedly test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a range that violates the provisions of the treaty. Russia rejected the accusation and counter-accused the United States for violating the treaty (see also ACA’s analysis of the Russian claims).

Conventional or Nuclear GLCM?

The US government has not publicly provided details about the Russian missile, except saying that it is a GLCM, that it has been test-launched several times since 2008, and that it is not currently in production or deployed. But US officials insist they have provided enough information to the Russian government for it to know what missile they’re talking about.

US statements have so far, as far as I’m aware, not made clear whether the GLCM test-launched by Russia is conventional, nuclear, or dual-capable. It is widely assumed in the public debate that it concerns a nuclear missile, but the INF treaty bans any ground-launched missile, whether nuclear or conventional. So the alleged treaty violation could potentially concern a conventional missile.

However, in a written answer to advanced policy questions from lawmakers in preparation for his nomination hearing in February for the position of secretary of defense, Ashton Carter appeared to identify the Russian GLCM as a nuclear system:

Question: What does Russia’s INF violation suggest to you about the role of nuclear weapons in Russian national security strategy?

Carter: Russia’s INF Treaty violation is consistent with its strategy of relying on nuclear weapons to offset U.S. and NATO conventional superiority.

That explanation would imply that US/ NATO conventional superiority to some extent has triggered Russian development and test-launch of the new nuclear GLCM. China and the influence of the Russian military-industrial complex might also be factors, but Russian defense officials and strategists are generally paranoid about NATO and seem convinced it is a real and growing threat to Russia. Western officials will tell you that they would not want to invade Russia even if you paid them to do it; only a Russian attack on NATO territory or forces could potentially trigger US/NATO retaliation against Russian forces.

Possible Responses To A Nuclear GLCM?

The Obama administration is currently considering how to respond if Russia does not return to INF compliance but produces and deploys the new nuclear GLCM. Diplomacy and sanctions have priority for now, but military options are also being considered. According to Carter, they should be designed to “ensure that Russia does not gain a military advantage” from deploying an INF-prohibited system:

The range of options we should look at from the Defense Department could include active defenses to counter intermediate-range ground-launched cruise missiles; counterforce capabilities to prevent intermediate-range ground-launched cruise missile attacks; and countervailing strike capabilities to enhance U.S. or allied forces. U.S. responses must make clear to Russia that if it does not return to compliance our responses will make them less secure than they are today.

What to do? Defense Secretary Ashton Carter wants to use counterforce and countervailing planning if Russia deploys its new ground-launched nuclear cruise missile.

The answer does not explicitly imply that a response would necessarily involve developing and deploying nuclear cruises missiles in Europe. Doing so would signal intent to abandon the INF Treaty but the Obama administration wants to maintain the treaty. Yet the reference to using “counterforce capabilities to prevent” GLCM attacks and “countervailing strike capability to enhance U.S. or allied forces” sound very 1980’ish.

Counterforce is a strategy that focuses on holding at risk enemy military forces. Using it to “prevent” attack implies drawing up plans to use conventional or nuclear forces to destroy the GLCM before it could be used. Current US nuclear employment strategy already is focused on counterforce capabilities and does not rely on countervalue and minimum deterrence, according to the Defense Department. Given that a GLCM would be able to strike its target within an hour (depending on range), preempting launch would require time-compressed strike planning and high readiness of forces, which would further deepen Russian paranoia about NATO intensions.

“Countervailing” was a strategy developed by the Carter administration to improve the flexibility and efficiency of nuclear forces to control and prevail in a nuclear war against the Soviet Union. The strategy was embodied in Presidential Directive-59 from July 1980. PD-59 has since been replaced by other directives but elements of it are still very much alive in today’s nuclear planning. Enhancing the countervailing strike capability of US and NATO forces would imply further improving their ability to destroy targets inside Russia, which would further deepen Russian perception of a NATO threat.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Part of Carter’s language is probably intended to scare Russian officials into concluding that the cost to Russia of deploying the GLCM would be higher than the benefits of restoring INF compliance – a 21st century version of the NATO double-track decision in 1979 that threatened deployment of INF missiles in Europe unless the Soviet Union agreed to limits on such weapons.

Back then the threat didn’t work at first. The Soviet Union rejected limitations and NATO went ahead and deployed INF missiles in Europe. Only when public concern about nuclear war triggered huge demonstrations in Europe and the United States did Soviet and US leaders agree to the INF Treaty that eliminated those weapons.

Reawakening the INF spectra in Europe would undermine security for all. Both Russia and the United States have to be in compliance with their arms control obligations, but threatening counterforce and countervailing escalation at this point may be counterproductive. Vladimir Putin does not appear to be the kind of leader that responds well to threats. And the INF issue has now become so entangled in the larger East-West crisis over Ukraine that it’s hard to see why Putin would want to be seen to back down on INF even if he agreed treaty compliance is better for Russia.

In fact, the military blustering and posturing that now preoccupy Russia and NATO could deepen the INF crisis. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and increased air operations across Europe fuel anxiety in NATO that leads to the very military buildup and modernization Russian officials say they are so concerned about. And NATO’s increased conventional operations and deployments in Eastern NATO countries probably deepen the Russian rationale that triggered development of the new GLCM in the first place.

Will Carter’s threat work? Right now it seems like one hell of a gamble.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Seeking China-U.S. Strategic Nuclear Stability

“To destroy the other, you have to destroy part of yourself.

To deter the other, you have to deter yourself,” according to a Chinese nuclear strategy expert. During the week of February 9th, I had the privilege to travel to China where I heard this statement during the Ninth China-U.S. Dialogue on Strategic Nuclear Dynamics in Beijing. The Dialogue was jointly convened by the China Foundation for International Strategic Studies (CFISS) and the Pacific Forum Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). While the statements by participants were not-for-attribution, I can state that the person quoted is a senior official with extensive experience in China’s strategic nuclear planning.

The main reason for my research travel was to work with Bruce MacDonald, FAS Adjunct Senior Fellow for National Security Technology, on a project examining the security implications of a possible Chinese deployment of strategic ballistic missile defense. We had discussions with more than a dozen Chinese nuclear strategists in Beijing and Shanghai; we will publish a full report on our findings and analysis this summer. FAS plans to continue further work on projects concerning China-U.S. strategic relations as well as understanding how our two countries can cooperate on the challenges of providing adequate healthy food, near-zero emission energy sources, and unpolluted air and water.

During the discussions, I was struck by the gap between American and Chinese perspectives. As indicated by the quote, Chinese strategic thinkers appear reluctant to want to use nuclear weapons and underscore the moral and psychological dimensions of nuclear strategy. Nonetheless, China’s leaders clearly perceive the need for such weapons for deterrence purposes. Perhaps the biggest gap in perception is that American nuclear strategists tend to remain skeptical about China’s policy of no-first-use (NFU) of nuclear weapons. By the NFU policy, China would not launch nuclear weapons first against the United States or any other state. Thus, China needs assurances that it would have enough nuclear weapons available to launch in a second retaliatory strike in the unlikely event of a nuclear attack by another state.

American experts are doubtful about NFU statements because during the Cold War the Soviet Union repeatedly stated that it had a NFU policy, but once the Cold War ended and access was obtained to the Soviets’ plans, the United States found out that the Soviets had lied. They had plans to use nuclear weapons first under certain circumstances. Today, given Russia’s relative conventional military inferiority compared to the United States, Moscow has openly declared that it has a first-use policy to deter massive conventional attack.

Can NFU be demonstrated? Some analysts have argued that China in its practice of keeping warheads de-mated or unattached from the missile delivery systems has in effect placed itself in a second strike posture. But the worry from the American side is that such a posture could change quickly and that as China has been modernizing its missile force from slow firing liquid-fueled rockets to quick firing solid-fueled rockets, it will be capable of shifting to a first-use policy if the security conditions dictate such a change.

The more I talked with Chinese experts in Beijing and Shanghai the more I felt that they are sincere about China’s NFU policy. A clearer and fuller exposition came from a leading expert in Shanghai who said that China has a two-pillar strategy. First, China believes in realism in that it has to take appropriate steps in a semi-anarchic geopolitical system to defend itself. It cannot rely on others for outside assistance or deterrence. Indeed, one of the major differences between China and the United States is that China is not part of a formal defense alliance pact such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the alliance the United States has with Japan and South Korea. Although in the 1950s, Chairman Mao Zedong decried nuclear weapons as “paper tigers,” he decided that the People’s Republic of China must acquire them given the threats China faced when U.S. General Douglas MacArthur suggested possible use of nuclear weapons against China during the Korean War. In October 1964, China detonated its first nuclear explosive device and at the same time declared its NFU policy.

The second pillar is based on morality. Chinese strategists understand the moral dilemma of nuclear deterrence. On the one hand, a nuclear-armed state has to show a credible willingness to launch nuclear weapons to deter the other’s launch. But on the other hand, if deterrence fails, actually carrying out the threat condemns millions to die. According to the Chinese nuclear expert, China would not retaliate immediately and instead would offer a peace deal to avert further escalation to more massive destruction. As long as China has an assured second strike, which might consist of only a handful of nuclear weapons that could hit the nuclear attacker’s territory, Beijing could wait hours to days before retaliating or not striking back in order to give adequate time for cooling off and stopping of hostilities.

Because China has not promised to provide extended nuclear deterrence to other states, Chinese leaders would also not feel compelled to strike back quickly to defend such states. In contrast, because of U.S. deterrence commitments to NATO, Japan, South Korea, and Australia, Washington would feel pressure to respond quickly if it or its allies are under nuclear attack. Indeed, at the Dialogue, Chinese experts often brought up the U.S. alliances and especially pointed to Japan as a concern, as Japan could use its relatively large stockpile of about nine metric tons of reactor-grade plutonium (which is still weapons-usable) to make nuclear explosives. Moreover, last July, the administration of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced a “reinterpretation” of the Article 9 restriction in the Japanese Constitution, which prohibits Japan from having an offensive military. (The United States imposed this restriction after the Second World War.) The reinterpretation allows Japanese Self-Defense Forces to serve alongside allies during military actions. Beijing is opposed because then Japan is just one step away from further changing to a more aggressive policy that could permit Japan to act alone in taking military actions. Before and during the Second World War, Japanese military forces committed numerous atrocities against Chinese civilians. Chinese strategists fear that Japan is seeking to further break out of its restraints.

Thus, Chinese strategists want clarity about Japan’s intentions and want to know how the evolving U.S.-Japan alliance could affect Chinese interests. Japan and the United States have strong concerns about China’s growing assertive actions near the disputed Diaoyu Islands (Chinese name) or Senkaku Islands (Japanese name) between China and Japan, and competing claims for territory in the South China Sea. Regarding nuclear forces, some Chinese experts speculate about the conditions that could lead to Japan’s development of nuclear weapons. The need is clear for continuing dialogue on the triangular relationship among China, Japan, and the United States.

Several Chinese strategists perceive a disparity in U.S. nuclear policy toward China. They want to know if the United States will treat China as a major nuclear power to be deterred or as a big “rogue” state with nuclear weapons. U.S. experts have tried to assure their Chinese counterparts that the strategic reality is the former. The Chinese experts also see that the United States has more than ten times the number of deliverable nuclear weapons than China. But they hear from some conservative American experts that the United States fears that China might “sprint for parity” to match the U.S. nuclear arsenal if the United States further reduces down to 1,000 or somewhat fewer weapons.1 According to the FAS Nuclear Information Project, China is estimated to have about 250 warheads in its stockpile for delivery.2Chinese experts also hear from the Obama administration that it wants to someday achieve a nuclear-weapon-free world. The transition from where the world is today to that future is fraught with challenges: one of them being the mathematical fact that to get to zero or close to zero, nuclear-armed states will have to reach parity with each other eventually.

FAS at Vienna Conference on Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons

By Hans M. Kristensen

For the next week I’ll be in Vienna for the Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons.

This is the third in a series of conferences organized and attended by a growing number of countries and humanitarian organizations to discuss the unique risks nuclear weapons pose to humanity and life on this planet. According to the Austrian government: “With this conference, Austria wishes to strengthen the global nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation regime and to contribute to the growing momentum to firmly anchor the humanitarian imperative in all global efforts dealing with nuclear weapons and nuclear disarmament.”

The nuclear-armed states have so far boycotted the conferences, but last month the Obama administration announced that the United States would attend after all – although with reservations. Britain quickly decided to join as well. No word from Russia or the other nuclear-armed states yet. [Update: China apparently has decided to participate as well.]

The State of World Nuclear Affairs

After a brief (although important and substantial) effort to reduce nuclear forces after the end of the Cold War, the nuclear-armed states are now slowing down the pace of reductions and shifting emphasis to modernizing their remaining nuclear arsenals. Some of them are even increasing their inventories and types. The modernization programs that all the nuclear-armed states have underway to extend their nuclear arsenals indefinitely are increasingly at odds with the their own promises – and the stated wishes of many of their allies and partners – to reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons.

At the same time, the non-nuclear allies and partners – many of which are participating in the Vienna conference – need to figure out how to reduce their reliance on the nuclear extended-deterrence provided by the nuclear-armed states. Otherwise, the need for nuclear “umbrellas” will block further reductions and fuel nuclear modernization programs in the nuclear-armed states.

This is not just a nuclear weapons issue. Excessive capability and modernization of conventional forces – or too little of them – may trigger some countries to use nuclear weapons to compensate. At the same time, conventional postures must meet some national defense need but without triggering insecurity in neighboring countries. So deep nuclear reductions may have to go hand in hand with relaxing or modifying conventional postures. How to square nuclear reductions with the overall balance and role of military power is truly one of the great challenges of the 21st Century.

But we’re not at that point in the disarmament process yet. Russia and the United States still possess extraordinarily disproportionately large nuclear arsenals compared with any other nuclear-armed state in the world. As owners of more than 90 percent of the world’s 16,300 nuclear weapons (FAS is honored that the Austrian Foreign Ministry conference web site and Media Information use the FAS estimate for the global inventory of nuclear weapons), Russia and the United States have a special responsibility to drastically reduce their nuclear arsenals first.

Meanwhile, the smaller nuclear-armed states (China, Pakistan, India, Israel, North Korea) have an equally important responsibility not to increase their nuclear arsenals. Without that self-imposed constraint, it is an illusion for those countries to demand that Russia and the United States (and its allies) agree to deep nuclear cuts.

These important challenges and the deterioration of East-West relations call for new and strengthened initiatives to sustain and deepen the efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

Two Presentations

I will give two presentations in Vienna. The first is at the Humanitarian Conference itself with Matthew McKinzie (NRDC) in the third panel on Scenarios, Challenges and Capabilities Regarding Nuclear Weapons Use and Other Events. The title of our presentation is “Deterrence, Nuclear War Planning, and Scenarios of Nuclear Conflict.”

The second presentation is at the ICAN Civil Society Forum preceding the Humanitarian Conference, where I will join Susi Snyder (PAX) in the panel: Nuclear Weapons In A Nutshell.

This publication and presentations in Vienna were made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The CTBT: At the Intersection of Science and Politics

Recent high-level meetings in Washington, D.C., the United Nations, California and Utah about the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) might lead one to believe that finally action might be taken towards ratification of the treaty. At the meeting in New York, foreign ministers and senior officials from 90 countries met on September 29 to acclaim the treaty and its value—both scientific and political. “This treaty isn’t just a feel-good exercise. It’s in all of our national security interests, and it’s verifiable,” said U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. “In fact, its verification regime is one of the great accomplishments of the modern world.” 1

In Washington, key U.S. officials—Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz, NNSA Director Frank Klotz, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Rose Gottemoeller, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Programs Andrew Weber–as well as Executive Secretary of the CTBT Organization Preparatory Commission Lassina Zerbo, held a public meeting on nuclear testing on September 15. “Today we can say with even greater certainty that we can meet the challenges of maintaining our stockpile with continued scientific leadership, not nuclear testing,” said Secretary Moniz. “So again, I repeat that the United States remains committed to ratification and entry into force of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, along with the monitoring and verification regime. And this administration will continue making the case for U.S. CTBT ratification to build bipartisan support.”2

Referring to the United States supercomputing and other capabilities, Mr. Klotz noted, “Thanks to this effort, today we have a greater understanding of how nuclear weapons actually work than we did when we were carrying out nuclear explosive testing. This is a remarkable achievement in innovation for our national security, and it is foundational to an effective no-test regime.”3

In addition, the largest scale, on-site inspection (OSI) simulation to date will be launched for a month in November in Jordan, and includes a day of visiting dignitaries, possibly to include the king. An OSI is the final step in the verification regime; it is a complex endeavor that involves enormous amounts of equipment and scientific as well as operational expertise. The simulation will be a significant test of the system.

Politics meets Science

Although the treaty deals with the highly technical and sensitive subject of nuclear test explosions, it has been considered in a political context since the negotiations. Countries possessing nuclear weapons do not want others to know about their facilities or capabilities, so verification provisions of the treaty were exceptionally difficult to negotiate. World-renown scientists worked in their labs and academic institutions, as well as in Geneva, on the intricacies of devising an international monitoring regime. They advised some of the top diplomats negotiating the treaty in Geneva. Even now, those working on the treaty still grapple with scientific questions in a political setting, the CTBTO Preparatory Commission in Vienna, as well as in their labs or government offices. The scientists possess the expertise and deep knowledge of the various verification techniques, and they provided information and counsel to their ambassadors, but the diplomats make the decisions.

Originally the key issues in the treaty revolved around questions such as: who should be included in the negotiations? What was to be the scope of the ban—a few pounds equivalent TNT of explosive yield, hundreds, or zero? (Negotiators decided on zero.) Would the non-nuclear weapon states agree with the nuclear weapon states that this would be a treaty to “ban the bang, not the bomb?” What kinds of monitoring technologies should be included in the treaty verification regime? Where would monitoring stations be placed? How many stations would be installed in the nuclear weapon states? Who would decide to conduct an OSI, and how would it be conducted? How could access to sensitive facilities be managed? And a crucial question: which countries were essential for entry into force? All of these questions, and more, involve complex scientific issues, but are highly political and contentious.

The CTBT prohibits “any nuclear weapon test explosion or any other nuclear explosion” anywhere in the world. The verification provisions of the CTBT are more extensive and intrusive than those of other treaties, as they are designed to detect nuclear explosions anywhere on the planet: underground, in the oceans, and in the atmosphere. In order to verify compliance with its provisions, the treaty specifies a global network of 327 monitoring facilities in strategic locations in 89 countries, and allows for on-site inspections of suspicious events. The International Monitoring System (IMS) comprises four complementary or synergistic technologies: seismic, radionuclide, hydroacoustic and infrasound. The 50 primary and 120 auxiliary seismic stations monitor the ground for shockwaves that are caused by nuclear explosions. A radionuclide network encompassing 80 stations uses air samplers to detect radioactive particles released from atmospheric, underground or underwater explosions. Half of these stations will be capable of detecting noble gases upon entry into force of the treaty. In addition, 16 radionuclide laboratories will analyze samples of filters from the stations (evidence of radionuclides is called the “smoking gun” of a nuclear explosion). In addition, there are 11 hydroacoustic stations to detect explosions in the oceans, and 60 infrasound stations designed to detect nuclear explosions in the atmosphere.

The CTBT Organization (CTBTO) Preparatory Commission was established in March 1997 and has been building up the verification regime, which is about 90 percent complete. The IMS has been detecting global activities such as: some 100 earthquakes each day, the nuclear test explosions conducted by North Korea in 2006, 2009, and 2013, in addition to tsunamis, the dispersal of the radioactive plume from Fukushima, and other activities. Data from the IMS stations is transmitted for analysis to the International Data Center of the Preparatory Commission’s Provisional Technical Secretariat.

In November 2014, the Preparatory Commission will embark on its second full-scale on-site inspection (OSI) simulation in Jordan to test the operation and techniques of an OSI in an integrated manner. Although the treaty includes a timeline and specifics of the on-site inspection regime, details of the operational manual and other logistical arrangements were left for the Preparatory Commission to elaborate. The exercise in Jordan will be the most challenging endeavor to date, aimed to test the ability to conduct an on-site inspection under realistic and challenging conditions, and to demonstrate the progress made since the last Integrated Field Exercise in Kazakhstan in 2008 (IFE08). During Integrated Field Exercise 2014 (IFE14), the Preparatory Commission will simulate a CTBT on-site inspection in which 40 inspectors search a designated area of up to 1,000 square kilometers for evidence of a possible nuclear explosion. IFE14 aims to test 15 of the 17 inspection techniques listed in the treaty in an integrated manner, a significant increase in the technologies tested at the previous IFE in Kazakhstan.

There are numerous OSI techniques, from visual observations and over-flights to multi-spectral imaging, airborne gamma spectroscopy, gamma radiation monitoring, environmental sampling, measurement of argon-37 and radioxenon, seismological monitoring of aftershocks, magnetic field mapping, resonance seismometry, and drilling, among others. The IFE14 will not employ drilling (which is extremely expensive), or resonance seismometry. It plans to exercise each phase of an OSI, from the receipt of the request through the launch, pre-inspection and post-inspection activities, reporting preliminary findings, departure, and return of equipment and personnel. The exercise will involve transporting some 150 tons of equipment from Austria to Jordan. According to the PTS website, the IFE14 will also test newly developed operational elements of an OSI such as an enhanced operations support center, an improved in-field communications system and a rapid deployment system for transporting tons of inspection equipment anywhere in the world.4It should be noted that an OSI can only take place once the treaty has entered into force, thus the Preparatory Commission has had time to develop the procedures.

The provisions in the treaty for an OSI are quite demanding. Because some of the effects from a nuclear explosion can be short-lived, the Executive Council will need to decide on the on-site inspection request within 96 hours of its receipt from the requesting state party, and an OSI inspection team and its equipment must be deployed and initiate inspection activities within a six-day period. During the course of the inspection, the inspection team may submit a proposal to extend the inspection to begin drilling, which must be approved by 26 Council members. The inspection may continue for 60 days, but if the inspection team determines that more time is needed to fulfill its mandate, it may be extended by an additional maximum of 70 days, subject to Council approval.

Developments since 1996

Under the terms of the treaty, countries can use data outside of the IMS that is available from thousands of other seismological or radionuclide stations, satellite observations and other national technical means, as well as advanced data analysis in their efforts to monitor the treaty. Countries may submit this additional information as a basis for a request for an OSI. The IMS is performing far better than expected by the negotiators who designed it. Yet since the CTBT was negotiated in 1996, dramatic scientific and technical advances in monitoring and data analysis techniques have occurred. If countries use the data from the IMS, in combination with what is available outside of the IMS, they could enhance their monitoring capability significantly beyond that provided by the treaty, by an order of magnitude. Using this combination of information would also allow a country to focus its monitoring efforts on countries of concern, individually or in cooperation with others. Such “precision monitoring” would be useful to countries of a region that could pool their resources to support the effort.5 In contrast, the Technical Secretariat is not allowed to use information from stations or advanced technologies that are not included in the treaty. Further, the Secretariat must take a global approach; it is not allowed to focus on specific areas. Such precision monitoring capabilities would be of interest to states where verification might be an issue in the ratification process.

By focusing on specific areas of concern, precision monitoring would also increase the ability to accurately locate events. This is key to identifying areas for on-site inspections. A notable feature of the CTBT is that the decision regarding non-compliance or whether to conduct an on-site inspection rests with the States Parties, not the CTBTO Technical Secretariat. This is contrary to the role of the IAEA and the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). It is therefore in the interest of the international community to expand the knowledge base on verification technologies in all countries in order to improve their ability to monitor the Treaty. Countries will need to send to Vienna representatives who are well versed in the provisions of the treaty and who have scientific expertise in the technologies it employs. This will increase the likelihood that a vote in the Executive Council (responsible for compliance with the treaty) on an on-site inspection or a decision about non-compliance will be based on scientific facts rather than concentrating on political concerns. That is especially important, given that the decision to conduct an OSI must be made by 30 of the 51 members of the Executive Council. Critics of the treaty believe that it will likely be impossible to achieve such a number, although the criteria for membership in the Council are such that the nuclear weapon states will always have a seat on the Council. Although the United States and a few other countries have their own technical means to monitor compliance with the treaty, most countries have not yet established their national facilities to efficiently monitor it.

The treaty was opened for signature in September 1996, and has been signed by 183 nations and ratified by 163. The treaty cannot enter into force until it is ratified by 44 “nuclear capable” nations6 specified in the treaty, eight of which have yet to do so (China, Egypt, India, Iran, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, and the United States). India, Pakistan, and North Korea have not signed it. Although many countries in the negotiations wanted to have a numerical provision (e.g., 65 ratifications), the five nuclear-weapon states in particular insisted that each of the five–and other states capable of developing a bomb–be on board for the treaty to enter into force.

After the United States triggered the negotiations on a CTBT in 1993 and committed considerable political will to conclude it in 1996 at the multilateral Conference on Disarmament, the Senate refused to ratify the treaty in 1999. Since then it has been sitting on the back burner of the U.S. Senate and its counterparts in the seven other countries required for entry into force. It is unlikely that the Obama administration will bring it up for a vote in the Senate unless it knows it has the votes. Only 28 of the senators who voted on the ratification of the treaty in 1999 remain in the Senate (13 of whom voted against), and that figure may decrease in the November elections. A number of the other holdout countries claim to be waiting for the United States to ratify first, which makes entry into force a political exercise waiting to happen. As Dr. Zerbo said in Washington, “We have to be mindful of those who have signed and ratified this treaty long ago, and been waiting for its entry into force.”

China is the only other nuclear-weapon state among the five declared under the NPT that still needs to ratify. “The U.S. pushed for the negotiations and it has tested more than any other nation,” said Sha Zukang, former Ambassador to the negotiations. “I firmly believe that, were the U.S. to ratify the Treaty, China would definitely follow.” He added that the CTBT could be useful in promoting China-U.S. strategic mutual trust and building a “new model of major country relations.” Noting that the United States had conducted 1032 nuclear test explosions and China and the UK just 45 each, he claimed that China and the international community believed that the United States “wanted to ensure the overwhelming superiority of its nuclear arsenal, both in quantity and quality.” He added, “Serious efforts should be made to encourage U.S. law-makers to change the idea of seeking absolute security at the cost of leaving all other countries feeling insecure, and then to support Treaty ratification.”7

In an influential 2009 report on the Strategic Posture of the United States8, conducted by a bipartisan Congressional Commission and chaired by former Secretary of State James Schlesinger, and former Secretary of Defense William Perry, the CTBT was the only issue on which agreement could not be achieved. Opponents contended that the zero yield prohibition of the treaty cannot be verified and that other countries would cheat, thereby gaining a military advantage, while the United States observed the terms of the treaty. They faulted the fact that the treaty does not define a nuclear test, and this could result in different countries having different understandings of prohibitions and restrictions, to include the possibility of conducting tests with hundreds of tons of nuclear yield. In this context, they believe that Russia and possibly China are conducting low yield testing. They also believe that maintaining a safe, reliable stockpile of nuclear weapons will require testing over time.9 A number of senators and decision makers believe these and other aspects of the treaty will not confer benefits and would pose security risks to the United States.10 Proponents contend that the treaty is a strong nonproliferation tool which is verifiable, and that other states could develop and test new or improved weapons without constraints (posing a greater threat to U.S. security), and that the United States can maintain a safe, secure, and reliable nuclear weapons stockpile without additional testing.

A number of studies have been conducted on the scientific and verification capabilities of the treaty, including one by the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. The Academy released in March 2012 an update of its 2002 report on Technical Issues associated with the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. The newer study, conducted by eminent scientists in the field, found that the United States “has the technical capabilities to maintain a safe, secure, and reliable stockpile of nuclear weapons into the foreseeable future without nuclear-explosion testing” and “is now better able to maintain a safe and effective nuclear stockpile and to monitor clandestine nuclear-explosion testing than at any time in the past.” The study found that globally, the IMS seismic network provides complete coverage at magnitude 3.8 with about 80 percent of stations operational.11 This is a low magnitude, and the capability has likely improved since the study was conducted, with 90 percent of the stations now operational. As mentioned previously, the IMS detected all three low yield tests conducted by North Korea. “Other States intent on acquiring and deploying modern, two-stage thermonuclear weapons would not be able to have confidence in their performance without multi-kiloton testing,” the report states. “Such tests would likely be detectable (even with evasion measures) by appropriately resourced U.S. national technical means and a completed IMS network.”

Scientific arguments notwithstanding, politics usually get in the way. As former NNSA Administrator Linton Brooks is fond of saying, “The CTBT will not be ratified until there is a Republican president who supports it.” Ambassador Brooks, who was a member of the more recent NAS committee, said that although the report presented positive conclusions about the capabilities of the treaty and was favorably received by both supporters and opponents for its technical accuracy, “I don’t know anyone whose mind it changed.”12

Following the negotiations, member states of the Preparatory Commission in Vienna established a Working Group on Verification to implement the verification regime. They began by considering issues such as what stations to build first, when data from the stations should be transmitted to the International Data Center in Vienna, how to configure the global communications infrastructure, how to authenticate the data, the elaboration of the OSI regime (techniques, equipment, training, operational manual), what the budget should be prior to entry into force, etc. The Working Group breaks down into sub-groups that are quite technical, if not wonkish. Scientific experts from many countries gather to consider topics such as sources of noble gas backgrounds, testing regional seismic travel time, data fusion, autonomous buoys, new optical seismometers, infrasound calibration, and the Bayesian inference approach. Again, the scientists who work in the technical sub-groups advise the diplomats who make decisions in the Working Group on these issues. The CTBTO Provisional Technical Secretariat then carries out these decisions. (In this context, it should be noted that three women participated in the scientific meetings in Geneva, two of whom are the only women participating in Vienna.)

Arguments over the treaty’s benefits and drawbacks have preceded the completion of the current treaty and go back to several earlier attempts decades ago at negotiating a ban. In fact, the negotiators of the Limited Test Ban of 1963 (LTBT) couldn’t agree on the verification provisions of a comprehensive ban, which is why it was limited (i.e. it covered all environments except underground). Article 1 of the CTBT is the same as Article 1 of the LTBT, but expanded to include underground. The LTBT has not been contested over the years, regardless of the fact that it has no verification provisions. Politics have trumped science in a number of instances, and the CTBT is no exception. Secretary Kerry said at the UN in September, “I know some members of the United States Senate still have concerns about this treaty. I believe they can be addressed by science, by facts, through computers and the technology we have today coupled with a legitimate stockpile stewardship program.” It remains to be seen if he can trump politics.

Jenifer Mackby is a Senior Fellow for International Security at FAS. Ms. Mackby has worked on international security, nonproliferation, and arms control issues at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) Organization, the Conference on Disarmament (CD) and the United Nations. As a Fellow and Adjunct Fellow at CSIS, she has led projects on U.S.-U.K. Nuclear Cooperation, Asian Trilateral Nuclear Dialogues, 21st Century Nuclear Issues, and the CTBT, and has worked on Strengthening the Global Partnership, European Trilateral Nuclear Dialogues, Reduction of U.S. forces in Europe, among others. Previously, she was responsible for the negotiations on the CTBT in the CD, as well as the Group of Scientific Experts that designed the core monitoring system of the treaty. She then served as Secretary of the Working Group on Verification at the CTBTO in Vienna. Ms. Mackby served as Secretary of the Biological Weapons Convention Review Conference, the UN Special Commission on Iraq, the Convention on Environmental Modification Techniques Review Conference, Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty Review Conference committee, and others. She is a Senior Adviser for the Partnership for a Secure America, and has written extensively about non-proliferation and arms control issues.

The New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

By Hans M. Kristensen

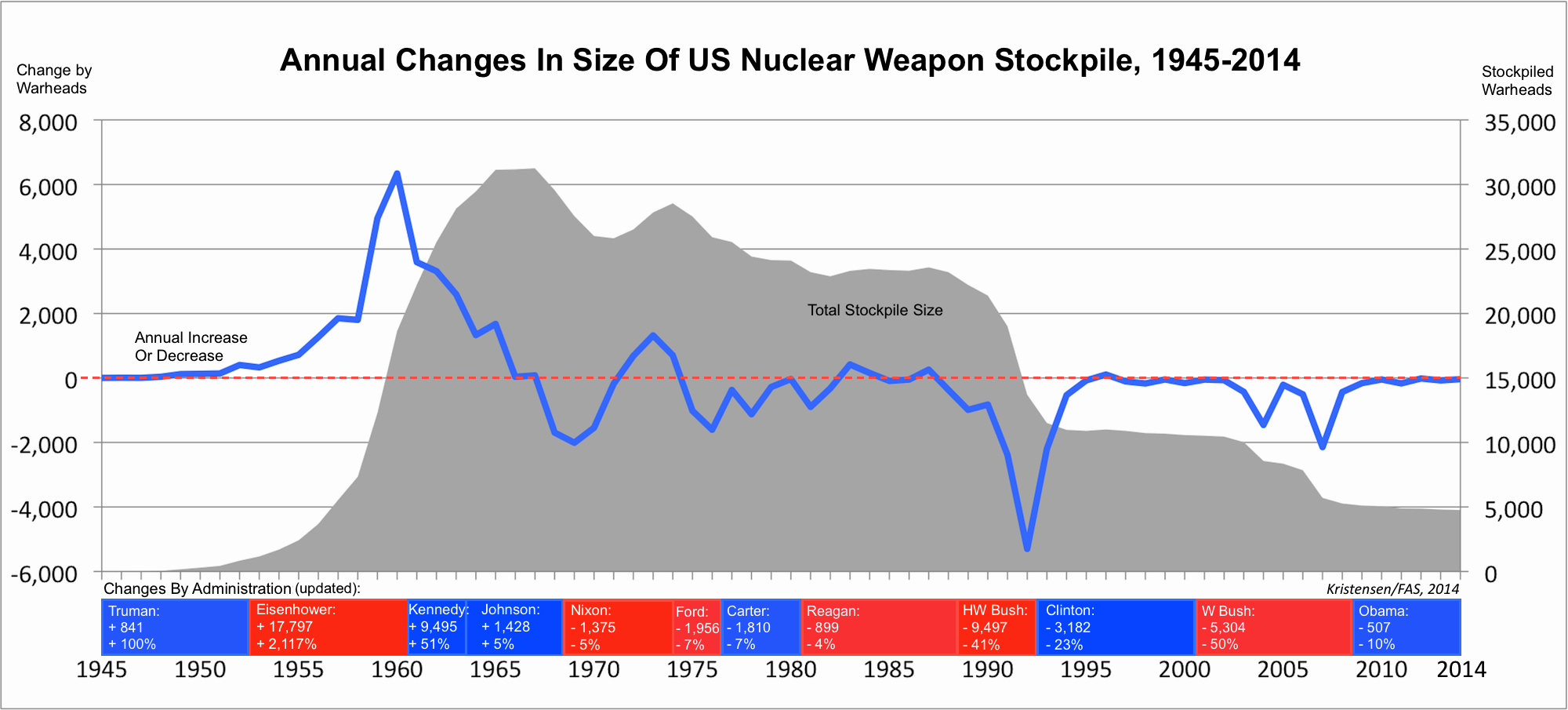

The New York Time today profiles my recent blog about U.S. presidential nuclear weapon stockpile reductions.

The core of the story is that the Obama administration, despite its strong arms control rhetoric and efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons, so far has cut fewer nuclear warheads from the U.S. nuclear weapon stockpile than any other administration in history.

Even in terms of effect on the overall stockpile size, the Obama administration has had the least impact of any of the post-Cold War presidents.

There are obviously reasons for the disappointing performance: The administration has been squeezed between, on the one side, a conservative U.S. congress that has opposed any and every effort to reduce nuclear forces, and on the other side, a Russian president that has rejected all proposals to reduce nuclear forces below the New START Treaty level and dismissed ideas to expand arms control to non-strategic nuclear weapons (even though he has recently said he is interested in further reductions).

As a result, the United States and its allies (and Russians as well) will be threatened by more nuclear weapons than could have been the case had the Obama administration been able to fulfill its arms control agenda.

Congress only approved the modest New START Treaty in return for the administration promising to undertake a sweeping modernization of the nuclear arsenal and production complex. Because the force level is artificially kept at levels above and beyond what is needed for national and international security commitments, the bill to the American taxpayer will be much higher than necessary.

The New York Times article says the arms control community is renouncing the Obama administration for its poor performance. While we are certainly disappointed, what we’re actually seeking is a policy change that cuts excess capacity in the arsenal, eliminates redundancy, stimulates further international reductions, and saves the taxpayers billions of dollars in the process.

In addition to taking limited unilateral steps to reduce excess nuclear capacity, the Obama administration should spend its remaining two years in office testing Putin’s recent insistence on “negotiating further nuclear arms reductions.” The fewer nuclear weapons that threaten Americans and Russians the better. That should be a no-brainer for any president and any congress.

New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

FAS Blog: How Presidents Arm and Disarm

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

How Presidents Arm and Disarm

The Obama administration has cut fewer nuclear weapons than any other post-Cold War administration.

It’s a funny thing: the administrations that talk the most about reducing nuclear weapons tend to reduce the least.

Analysis of the history of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile shows that the Obama administration so far has had the least effect on the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidencies.

In fact, in terms of warhead numbers, the Obama administration so far has cut the least warheads from the stockpile of any administration ever.

I have previously described how Republican presidents historically – at least in the post-Cold War era – have been the biggest nuclear disarmers, in terms of warheads retired from the Pentagon’s nuclear warhead stockpile.

Additional analysis of the stockpile numbers declassified and published by the Obama administration reveals some interesting and sometimes surprising facts.

What went wrong? The Obama administration has recently taken a beating for its nuclear modernization efforts, so what can President Obama do in his remaining two years in office to improve his nuclear legacy?

Effect on Warhead Numbers

On the graph above I have plotted the stockpile changes over time in terms of the number of warheads that were added or withdrawn from the stockpile each year. Below the graph are shown the various administrations with the total number of warheads that each added or withdrew from the stockpile during its period in office.

The biggest increase in the stockpile occurred during the Eisenhower administration, which added a total of 17,797 warheads – an average of 2,225 warheads per year! Those were clearly crazy times; the all-time peak growth in one year was 1960, when 6,340 warheads were added to the stockpile! That same year, the United Sates produced a staggering 7,178 warheads, rolling them off the assembly line at an average rate of 20 new warheads every single day.

The Kennedy administration added another 9,495 warheads in the nearly three years before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in October 1963. The Johnson administration initially continued increasing the stockpile and it was in 1967 that the stockpile reached its all-time high of 31,255 warheads. In its second term, however, the Johnson administration began reducing the stockpile – the first U.S. administration to do so – and ended up shrinking the stockpile by 1,428 warheads.

During the Nixon administration, the military started loading multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, but the stockpile declined for the first time due to retirement of large numbers of older warhead types. The successor, the Ford administration, reduced the stockpile and President Gerald Ford actually became the Cold War-period president who reduced the size of the stockpile the most: 1,956 warheads.

The Carter administration came in a close second Cold War disarmer with 1,810 warheads withdrawn from the stockpile.

The Reagan administration, which in its first term was seen by many as ramping up the Cold War, ended up shrinking the total stockpile by almost 900 warheads. But during three of its years in office, the administration actually increased the stockpile slightly, and the portion of those warheads that were deployed on strategic delivery vehicles increased as well.

As the first post-Cold War administration, the George H.W. Bush presidency initiated enormous nuclear weapons reductions and ended up shrinking the stockpile by almost 9,500 warheads – almost exactly the number the Kennedy administration increased the stockpile. In one year (1992), Bush cut 5,300 warheads, more than any other president – ever. Much of the Bush cut was related to the retirement of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration came into office riding the Bush reduction wave, so to speak, and in its first term cut approximately 3,000 warheads from the stockpile. But in his second term, President Clinton slowed down significantly and in one year (1996) actually increased the stockpile by 107 weapons – the first time since 1987 that had happened and the only increase in the post-Cold War era so far. It is still unclear what caused the 1996 increase. When the Clinton administration left office, there were still approximately 10,500 nuclear warheads in the stockpile.

President George W. Bush, who many of us in the arms control community saw as a lightning rod for trying to build new nuclear weapons and advocating more proactive use against so-called “rogue” states, ended up becoming one of the great nuclear disarmers of the post-Cold War era. Between 2004 and 2007 (mainly), the Bush W. administration unilaterally cut the stockpile by more than half to roughly 5,270 warheads, a level not seen since the Eisenhower administration. Yet the remaining Bush arsenal was considerably more capable than the Eisenhower arsenal.

President Barack Obama took office with a strong arms control profile, including a pledge to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, taking nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, and “put and end to Cold War thinking.” So far, however, this policy appears to have had only limited effect on the size of the stockpile, with about 500 warheads retired over six years.

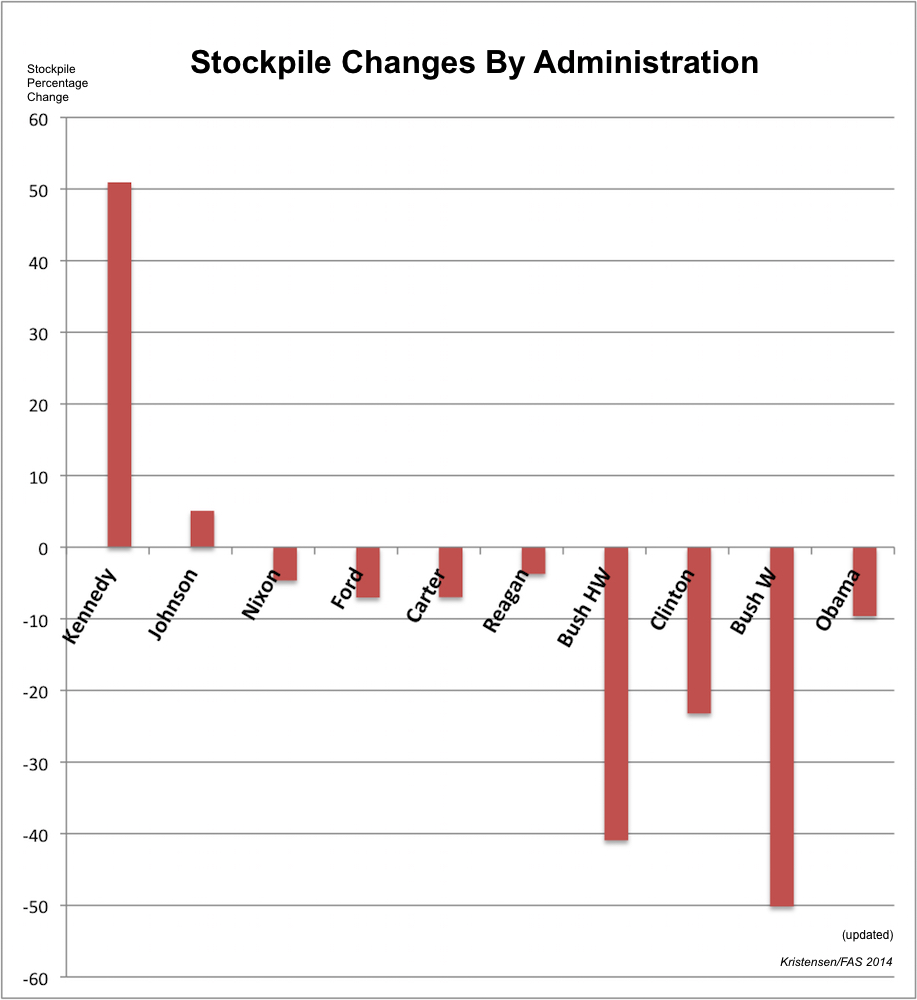

Effect On Stockpile Size

Counting warhead numbers is interesting but since the stockpile today is much smaller than during the previous three presidencies, comparing the number of warheads retired doesn’t accurately describe the degree of change inflicted by each president.

A better way is to compare the reductions as a percentage of the size of the stockpile at the beginning of each presidency. That way the data more clearly illustrates how much of an impact on stockpile size each president was responsible for.

This type of comparison shows that George W. Bush changed the stockpile the most: by a full 50 percent. His father, President H.W. Bush, came in a strong second with a 41 percent reduction. Combined, the Bush presidents cut a staggering 14,801 warheads from the stockpile during their 12 years in office – 1,233 warheads per year. President Clinton reduced the stockpile by 23 percent during his eight years in office.

The Obama administration has had less effect on the nuclear weapon stockpile than any other post-Cold War administration.

Despite his strong rhetoric about reducing the numbers of nuclear weapons, however, President Obama so far had the least effect on the size of the stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidents: a reduction of 10 percent over six years. The remaining two years of the administration will likely see some limited reductions due to force adjustments and management, but nothing on the scale seen during the tree previous post-Cold War presidencies.

What Went Wrong?

There are of course reasons for the Obama administration’s limited success in reducing the number of nuclear weapons compared with the accomplishments of previous post-Cold War administrations.

The first reason is that the Obama administration during all of its tenure has faced a conservative Congress that has openly opposed any attempts to reduce the arsenal significantly. Even the modest New START Treaty was only agreed to in return for commitments to modernize the remaining arsenal. A conservative Congress does not complain when Republican presidents reduce the stockpile, only when Democratic president try to do so. As a result of the opposition, the United States is now stuck with a larger and more expensive nuclear arsenal than had Congress agreed to significant reductions.

A second reason is that Russian president Vladimir Putin has rejected additional arms reductions beyond the New START Treaty. Because the Obama administration has made additional reductions conditioned on Russian agreement, the United States today deploys one-third more nuclear warheads than it needs for national and international security commitments. Ironically, because of Putin’s opposition to additional reductions, Russia will now be “threatened” by more U.S. nuclear weapons than had Putin agreed to further reductions beyond New START. As a result, Russian taxpayers will have to pay more to maintain a bigger Russian nuclear force than would otherwise have been necessary.

A third reason is that the U.S. nuclear establishment during internal nuclear policy reviews was largely successful in beating back the more drastic disarmament ambitions president Obama may have had. Even before the Nuclear Posture Review was completed in April 2010, a future force level had already been decided for the New START Treaty based largely on the Bush administration’s guidance from 2002. President Obama’s Employment Strategy from June 2013 could have changed that, but it didn’t. It failed to order additional reductions beyond New START, reaffirmed the need for a Triad, retained the current alert and readiness level, and rejected less ambitious and demanding targeting strategies.

In the long run, some of the Obama administration’s policies are likely to result in additional unilateral reductions to the stockpile. One of these is the decision that fewer non-deployed warheads are needed in the “hedge.” Another effect will come from the decision to reduce the number of missiles on the next-generation ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 16, which will unilaterally reduce the number of warheads needed for the sea-based leg of the Triad. A third effect will come from a decision to phase out most of the gravity bombs in the arsenal. But these decisions depend on modernization of nuclear weapons production facilities and weapons and are unlikely to have a discernible effect on the size of the stockpile or arsenal until well after president Obama has left office.

The Next Two Years

During its last two years in office, the Obama administration’s best change to achieve some of the stockpile reductions it failed to demonstrate in the first six years would be to initiate reductions now that are planned for later. In addition to implementing the reductions planned under the New START Treaty early, potential options include offloading excess Trident II SLBMs and retiring excess W76 warheads above what is needed for arming the future fleet of 12 SSBNX submarines; there are currently nearly 50 Trident II SLBMs too many deployed and about 800 W76s too many in the stockpile, so many that the Navy has asked DOE to accept transfer of excess W76s from navy depots faster than planned to free up space and save money. It also includes retiring excess warheads for cruise missiles and gravity bombs above what’s required for the B61-12 and LRSO programs; most, if not all, B61-3, B61-10, B83-1, and W84 warheads could probably be retired right away. Moreover, several hundred W78 and W87 warheads for the Minuteman ICBMs could probably be retired because they’re in excess of what’s needed for the force planned under New START.

But in addition to retiring excess warheads, there are also strong fiscal and operational reasons to work with congressional leaders interested in trimming the planned modernization of the remaining nuclear forces. Options include reducing the SSBNX program from 12 to 10 or 8 operational submarines, reducing the ICBM force to 300 by closing one of the three bases and ending considerations to develop a new mobile or “hybrid” ICBM, delaying the next-generation bomber, canceling the new cruise missile (LRSO), scaling back the B61-12 program to a simple life-extension of the B61-7, canceling nuclear capability for the F-35 fighter-bomber, and work with NATO allies to phase out deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Such reductions would have the added benefit of significantly reducing the capacity needed for warhead life-extension programs and production facilities.

Achieving some or all of these reductions would free up significant resources more urgently needed for maintaining and modernizing non-nuclear forces. The excess nuclear forces provide no discernible benefits to day-to-day national security needs and the remaining forces would still be more than adequate to deter and defeat potential adversaries – even a more assertive Russia.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

W80-1 Warhead Selected For New Nuclear Cruise Missile

The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Council has selected the W80-1 thermonuclear warhead for the Air Force’s new nuclear cruise missile (Long-Range Standoff, LRSO) scheduled for deployment in 2027.

The W80-1 warhead is currently used on the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), but will be modified during a life-extension program and de-deployed with a new name: W80-4.

Under current plans, the ALCM will be retired in the mid-2020s and replaced with the more advanced LRSO, possibly starting in 2027.

The enormous cost of the program – $10-20 billion by some estimates – is robbing defense planners of resources needed for more important non-nuclear capabilities.

Even though the United States has thousands of nuclear warheads on ballistic missiles and is building a new penetrating bomber to deliver nuclear bombs, STRATCOM and Air Force leaders are arguing that a new nuclear cruise missile is needed as well.

But their description of the LRSO mission sounds a lot like old-fashioned nuclear warfighting that will add new military capabilities to the arsenal in conflict with the administration’s promise not to do so and reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

What Kind of Warhead?

The selection of the W80-1 warhead for the LRSO completes a multi-year process that also considered using the B61 and W84 warheads.

The W80-4 selected for the LRSO will be the fifth modification name for the W80 warhead (see table below): The first was the W80-0 for the Navy’s Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), which was retired in 2011; the second is the W80-1, which is still used the ALCM; the third was the W80-2, which was a planned LEP of the W80-0 but canceled in 2006; the fourth was the W80-3, a planned LEP of the W80-1 but canceled in 2006.