Human Factors in Verifying Warhead Dismantlement

Arms control agreements that envision the verified dismantlement of nuclear weapons require the availability of suitable technology to perform the verification. But they also depend on the good faith of the participants and a shared sense of confidence in the integrity of the verification process.

An exercise in demonstrated warhead dismantlement showed that such confidence could be easily disrupted. The exercise, sponsored by the United States and the United Kingdom in 2010 and 2011, was described in a recent paper by Los Alamos scientists. See Review of the U.S.-U.K. Warhead Monitored Dismantlement Exercise by Danielle Kristin Hauck and Iain Russell, Los Alamos National Laboratory, August 4, 2016.

Participants played the roles of the host nation, whose weapons were to be dismantled, and of the monitoring nation, whose representatives were there to verify dismantlement. Confusion and friction soon developed because “the host and monitoring parties had different expectations,” the authors reported.

“The monitoring party did not expect to justify its reasons for performing certain authentication tasks or to justify its rationale for recommending whether a piece of equipment should or should not be used in the monitoring regime. However, the host party expected to have an equal stake in authentication activities, in part because improperly handled authentication activities could result in wrongful non-verification of the treaty.”

“Attempts by the host team to be involved in the authentication activities, and requests for justifications of monitoring party decisions felt intrusive and controlling. Monitoring party rebuffs to the host team reduced the host’s confidence in the sincerity of the monitoring party for cooperative monitoring.”

What emerged is that verified dismantlement of nuclear weapons is not simply a technical problem, though it is also that.

New START Data Shows Russian Warhead Increase Before Expected Decrease

By Hans M. Kristensen

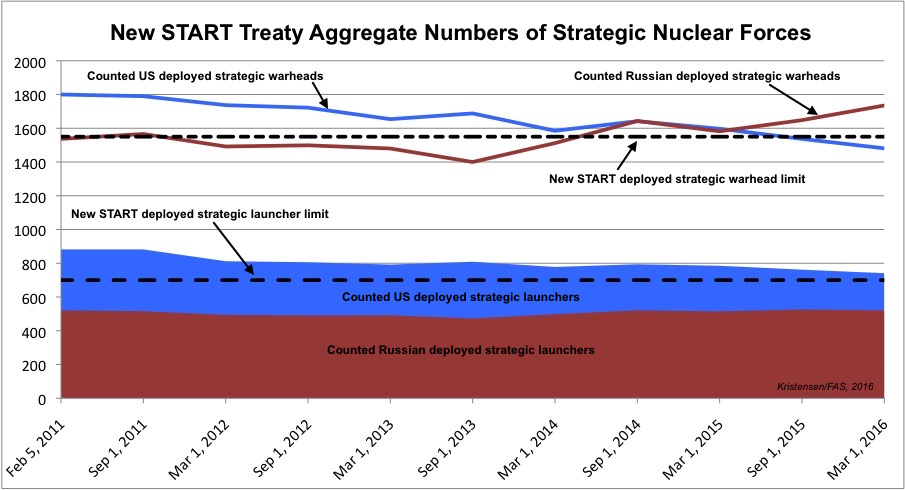

The latest set of so-called New START treaty aggregate data published by the U.S. State Department shows that Russia is continuing to increase the number of nuclear warheads it deploys on its declining inventory of strategic launchers.

Russia now has 259 warheads more deployed than when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Rather than a nuclear build-up, however, the increase is a temporary fluctuation cause by introduction of new types of launchers that will be followed by retirement of older launchers before 2018. Russia’s compliance with the treaty is not in doubt.

In all other categories, the data shows that Russia and the United States continue to reduce the overall size of their strategic nuclear forces.

Strategic Warheads

The aggregate data shows that Russia has continued to increase its deployed strategic warheads since 2013 when it reached its lowest level of 1,400 warheads. Russian strategic launchers now carry 396 warheads more.

Overall, Russia has increase its deployed strategic warheads by 259 warheads since New START entered into force in 2011. Although it looks bad, it has no negative implications for strategic stability.

The Russian warhead increase is probably a temporary anomaly caused primarily by the fielding of additional new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The third boat of the class deployed to its new base on the Kamchatka Peninsula last month, joining another Borei SSBN that transferred to the Pacific in 2015.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed strategic warheads. It dipped below the treaty limit in September 2015 but has continued to decrease its deployed warheads to 1,367 deployed strategic warheads

Overall, the United States has decreased its deployed strategic warheads by 433 since New START entered into force in February 2011.

As a result, the disparity in Russian and U.S. deployed strategic warheads is now greater than at any previous time since New START entered into force in 2011: 429 warheads.

It’s important to remind that the counted deployed strategic warheads only represent a portion of the two countries total warhead inventories; we estimate Russia and the United States each have roughly 4,500 warheads in their military stockpiles. The New START treaty only limits how many strategic weapons can be deployed but has no direct effect on the size of the total nuclear stockpiles.

The Russian increase in deployed strategic warheads is temporary due to fielding of several new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines. This picture shows the Vladimir Monomakh arriving at the submarine base near Petropavlovsk on September 27, 2016.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data shows that both Russia and the United States continue to reduce their strategic launchers.

Russia has been below the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers since New START entered into force in 2011. Even so, it continues to reduce its strategic launchers. Thirteen deployed launchers have been removed since March 2016 and Russia overall now has 13 launchers fewer than in 2011.

Russia will have to dismantle another 47 launchers to meet the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers by February 2018. Those launchers will likely come from retirement of the remaining Delta III SSBNs, retirement of additional Soviet-era ICBMs, and destruction of empty excess ICBM silos.

The United States is not also for the first time below the limit for deployed strategic launchers. The latest data lists 681 launchers deployed, a reduction of 60 compared with March 2016. The reduction reflects the ongoing work to denuclearize excess B-52H bombers, deactivate four excess launch tubes on each SSBN, and remove ICBMs from 50 excess silos.

The United States still has a considerable advantage in deployed strategic launchers: 681 versus Russia’s 508. But the disparity of 173 launchers is smaller than it was six months ago. The United States will need to dismantle another 48 launchers to meet the treaty’s limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers by February 2018.

Strategic Context

The ongoing implementation of the New START treaty is one of the only remaining bright spots on the otherwise tense and deteriorating relationship between Russia and the United States. Despite the current increase of Russian deployed strategic warheads, which is temporary and will be followed by retirement of older systems in the next few years that will reduce the count, Russian compliance with the treaty by 2018 is not in doubt. And both countries continue to reduce their deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers.

In fact, the temporary warhead increase seems to be of little concern to U.S. military planners. DOD concluded in 2012 that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty…”

Equally important are the ongoing onsite inspections and notifications between the United States and Russia. The two countries have each carried out 103 inspections and exchanged 11,817 notifications since the treaty entered into force in 2011. These activities are increasingly important confidence-building measures.

Yet the modest reductions under the treaty must also be seen in the context of the extensive nuclear weapons modernization programs underway in both countries. Although these programs do not constitute a buildup of the overall nuclear arsenal, they are very comprehensive and reaffirm the determination by both Russia and the United States to retain large offensive nuclear arsenals at high levels of operational readiness.

Although those forces are significantly smaller than the arsenals that existed during the Cold War, they are nonetheless significantly larger than the arsenals of any other nuclear-armed state.

Moreover, New START contains no sub-limits, which enables both sides to take advantage of loopholes. Whereas the now-abandoned START II treaty banned multiple warheads (MIRV) on ICBMs, the New START treaty has no such limits, which enables Russia to incorporate MIRV on its new ICBMs and the United States to store hundreds of non-deployed warheads for re-MIRVing of its ICBMs. Russia is developing a new “heavy” ICBM with MIRV and the next U.S. ICBM (GBSD) will be capable of carrying MIRV as well.

Similarly, the “fake” bomber count of attributing only one deployed strategic weapon per bomber despite its capacity to carry many more has caused both sides to retain large inventories of non-deployed weapons to retain a quick upload capability with many hundreds of long-range nuclear cruise missiles. And both sides are developing new nuclear-armed cruise missiles.

How the two countries justify such large arsenals is somewhat of a mystery but seem to be mainly determined by the size of the other side’s arsenal. According to the U.S. State Department, the New START “limits are based on the rigorous analysis conducted by Department of Defense planners in support of the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.”

Yet a recent GAO analysis of the 2010 NPR force structure found that “DOD officials were unable to provide us documentation of the NPR’s analysis of strategic force structure options that were considered.” Instead, STRATCOM, the Air Force and the Navy conducted their own analysis of options, which were discussed at senior-level meetings but not documented.

Both sides can easily reduce their nuclear forces further and increase security, reduce insecurity, and save money while doing so. Possible steps include: a five-year extension of the New START Treaty, lowering the limits of the existing treaty by one-third while maintaining the inspection regime, and taking unilateral steps to reduce the nuclear weapons modernization programs.

Additional information:

- Status of world nuclear forces

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces 2016

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russia nuclear forces 2016

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Non-Nuclear Bombers For Reassurance and Deterrence

Two non-nuclear B-1 bombers accompanied by two Japanese F-16 fighters before heading to South Korea for a demonstration overflight with South Korean forces in response to North Korea’s recent nuclear test.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force today sent two non-nuclear B-1 bombers to overfly South Korea in response to North Korea’s recent nuclear test.

The operation coincides with the deployment of two non-nuclear B-1 bombers and a recently denuclearized B-52 bomber to Europe for exercise Ample Strike.

To be sure, nuclear bombers continue to deploy to both Asia and Europe, and U.S. strategic bombers have had the capability to deliver conventional weapons for many years.

But the use of exclusively non-nuclear strategic bombers in support of extended deterrence missions signals a new phase in U.S. military strategy that is part of an effort to reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

Korea: Non-Nuclear Bomber Deployment

The conventional B-1 overflight of Korea was explicitly described by U.S. Pacific Command as a “response to the recent nuclear test by North Korea.”

The two B-1s are from the 28th Bomb Wing at Ellsworth Air Force Base in South Dakota, which in August forward deployed a squadron of the bombers to Anderson AFB on Guam for several months of operations in the Pacific. The B-1s relieved nuclear-capable B-52 bombers that had operated from the base more or less continuously since 2004. Nuclear B-2 bombers also occasionally operate out of Guam.

Europe: Non-Nuclear Bomber Deployment

The B-1 overflight of South Korea coincides with the deployment of a non-nuclear bomber strike group to Europe for exercise Ample Strike. The group consists of two non-nuclear B-1 bombers from Dyess AFB and a recently denuclearized B-52 bomber from Barksdale AFB that operate out of the RAF Fairford base in the United Kingdom.

The B-52 that visited Slovakia prior to exercise Ample Strike was recently denuclearized under the New START treaty.

Converting Bombers to Non-Nuclear Missions

The non-nuclear strategic bombers sent on assurance and deterrence operations in Europe and Asia are part of conversion of formerly nuclear bombers to conventional-only capability.

The B-1 was removed from nuclear planning in 1997 when the B-2 entered the force. But the B-1 was retained in a Nuclear Rerole Plan under which it could be returned to the nuclear mission in six months if necessary. The rerole plan was canceled in 2003 but the B-1s still had equipment that made them accountable under the 2010 New START treaty. Eventually, the last B-1 was stripped of nuclear equipment in 2011.

The B-1 has been used as a bomber as part of the war on terrorism for years. But the bomber was recently equipped with the new long-range conventional JASSM cruise missile and integrated into Air Force Global Strike Command as a strategic strike bomber alongside the B-52 and B-2 bombers. Each B-1 can carry up to 24 JASSMs.

The B-1 has been equipped to carry up to 24 long-range conventional JASSM cruise missiles and is being integrated into strategic strike planning.

The B-52 used in the ongoing Ample Strike exercise in Europe along with two non-nuclear B-1s was recently denuclearized as part of the implementation of the New START treaty. A total of 30 operational B-52s will be denuclearized before 2018 to reduce the number of deployed nuclear bombers to no more than 60.

B-52s have been able to launch Conventional Air Launched Cruise Missiles for many years but are now being converted to carry the JASSM and, in the case of 30 operational B-52s, being stripped of their nuclear capability. Each B-52 can carry up to 20 JASSMs.

The B-52 is being upgraded to carry the long-range conventional JASSM cruise missile. This drop test in 2016 is part of a bomb bay upgrade to enable each B-52 to carry 20 JASSMs.

Reducing the Role of Nuclear Weapons

The two non-nuclear bomber operations are important because they follow the 2013 Nuclear Employments Strategy which, among other things, directed the military to “conduct deliberate planning for non-nuclear strike options to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options…”

Although non-nuclear weapons are officially not seen as a substitute for nuclear weapons, the guidance stated that “planning for non-nuclear strike options is a central part of reducing the role of nuclear weapons.”

Advocates for building a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO) argue old-fashionedly that the weapon is essential for providing assurance and deterrence in support of allies in Europe and Asia. But the recent non-nuclear bomber operations demonstrate that conventional bomber with conventional cruise missiles can also serve that mission – and already do.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Seeking Verifiable Destruction of Nuclear Warheads

A longstanding conundrum surrounding efforts to negotiate reductions in nuclear arsenals is how to verify the physical destruction of nuclear warheads to the satisfaction of an opposing party without disclosing classified weapons design information. Now some potential new solutions to this challenge are emerging.

Based on tests that were conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission in the 1960s in a program known as Cloudgap, U.S. officials determined at that time that secure and verifiable weapon dismantlement through visual inspection, radiation detection or material assay was a difficult and possibly insurmountable problem.

“If the United States were to demonstrate the destruction of nuclear weapons in existing AEC facilities following the concept which was tested, many items of classified weapon design information would be revealed even at the lowest level of intrusion,” according to a 1969 report on Demonstrated Destruction of Nuclear Weapons.

But in a newly published paper, researchers said they had devised a method that should, in principle, resolve the conundrum.

“We present a mechanism in the form of an interactive proof system that can validate the structure and composition of an object, such as a nuclear warhead, to arbitrary precision without revealing either its structure or composition. We introduce a tomographic method that simultaneously resolves both the geometric and isotopic makeup of an object. We also introduce a method of protecting information using a provably secure cryptographic hash that does not rely on electronics or software. These techniques, when combined with a suitable protocol, constitute an interactive proof system that could reject hoax items and clear authentic warheads with excellent sensitivity in reasonably short measurement times,” the authors wrote.

See Physical cryptographic verification of nuclear warheads by R. Scott Kemp, et al,Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online July 18.

More simply put, it’s “the first unspoofable warhead verification system for disarmament treaties — and it keeps weapon secrets too!” tweeted Kemp.

See also reporting in Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Phys.org.

In another recent attempt to address the same problem, “we show the viability of a fundamentally new approach to nuclear warhead verification that incorporates a zero-knowledge protocol, which is designed in such a way that sensitive information is never measured and so does not need to be hidden. We interrogate submitted items with energetic neutrons, making, in effect, differential measurements of both neutron transmission and emission. Calculations for scenarios in which material is diverted from a test object show that a high degree of discrimination can be achieved while revealing zero information.”

See A zero-knowledge protocol for nuclear warhead verification by Alexander Glaser, et al, Nature, 26 June 2014.

But the technology of nuclear disarmament and the politics of it are two different things.

For its part, the U.S. Department of Defense appears to see little prospect for significant negotiated nuclear reductions. In fact, at least for planning purposes, the Pentagon foresees an increasingly nuclear-armed world in decades to come.

A new DoD study of the Joint Operational Environment in the year 2035 avers that:

“The foundation for U.S. survival in a world of nuclear states is the credible capability to hold other nuclear great powers at risk, which will be complicated by the emergence of more capable, survivable, and numerous competitor nuclear forces. Therefore, the future Joint Force must be prepared to conduct National Strategic Deterrence. This includes leveraging layered missile defenses to complicate adversary nuclear planning; fielding U.S. nuclear forces capable of threatening the leadership, military forces, and industrial and economic assets of potential adversaries; and demonstrating the readiness of these forces through exercises and other flexible deterrent operations.”

See The Joint Operating Environment (JOE) 2035: The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 14 July 2016.

Navy Builds Underground Nuclear Weapons Storage Facility; Seattle Busses Carry Warning

Seattle busses warn of largest nuclear weapons base. Click image to see full size.

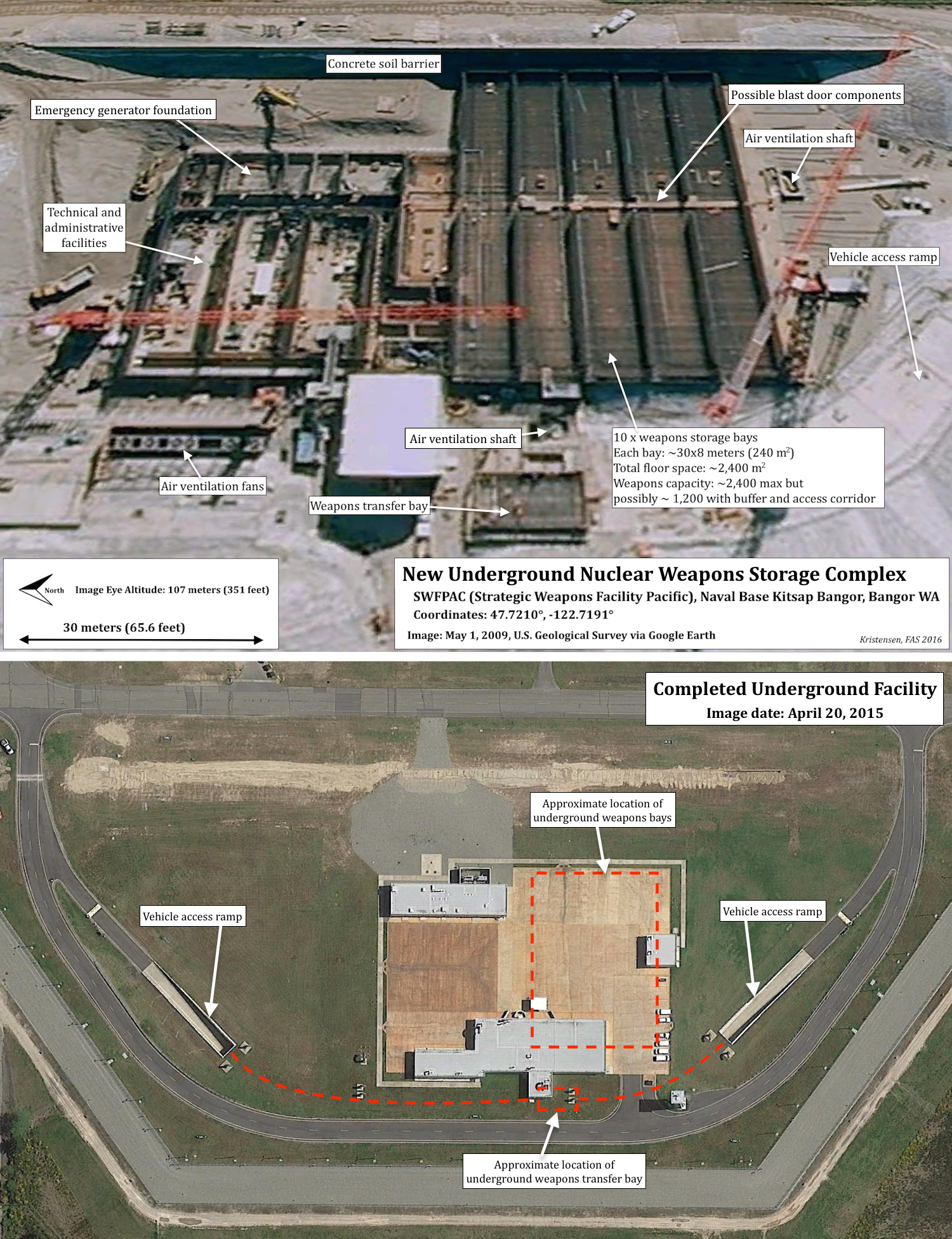

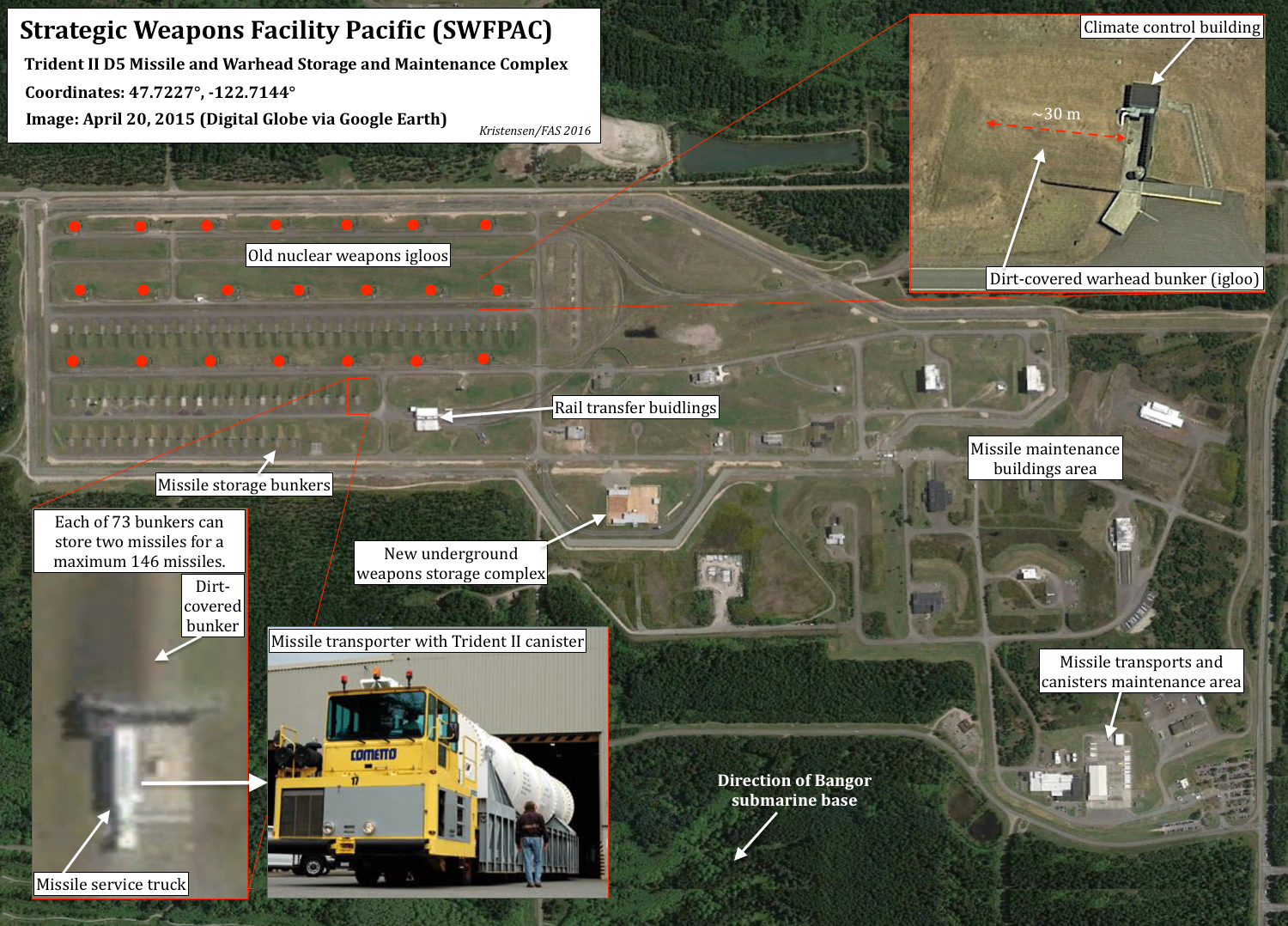

The US Navy has quietly built a new $294 million underground nuclear weapons storage complex at the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC), a high-security base in Washington that stores and maintains the Trident II ballistic missiles and their nuclear warheads for the strategic submarine fleet operating in the Pacific Ocean.

The SWFPAC and the eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) homeported at the adjacent Bangor Submarine Base are located only 20 miles (32 kilometers) from downtown Seattle. The SWFPAC and submarines are thought to store more than 1,300 nuclear warheads with a combined explosive power equivalent to more than 14,000 Hiroshima bombs.

A similar base with six SSBNs is located at Kings Bay in Georgia on the US east coast, which houses the SWFLANT (Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic) that appears to have a dirt-covered warhead storage facility instead of the underground complex built at SWFPAC. Of the 14 SSBNs in the US strategic submarine fleet, 12 are considered operational with 288 ballistic missiles capable of carrying 2,300 warheads. Normally 8-10 SSBNs are loaded with missiles carrying approximately 1,000 warheads.

To bring public attention to the close proximity of the largest operational nuclear stockpile in the United States, the local peace group Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action has bought advertisement space on 14 transit buses. The busses will carry the posters for the next eight weeks. FAS is honored to have assisted the group with information for its campaign.

The Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex

Although the new underground storage complex is not a secret – its existence has been reported in public navy documents since 2003 – it has largely escaped public attention until now.

The new complex is officially known as the Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex (LAPSC), or navy construction Project Number P973A. The complex was originally estimated to cost $110 million but ended up costing nearly $294 million.

The US Navy describes the complex as “a reinforced concrete, underground, multi-level re-entry body processing and storage facility” with “hardened floors, and hardened load-bearing walls and roof.” Glen Milner at the Ground Zero Center helped locate some of the budget documents. Other construction details provided by the navy further describe the complex as:

A 16,000-m2 [180,000 square feet] multi-level, underground, hardened, blast-resistant, reinforced concrete structure, with approximate dimensions of 110 meters long by 82 meters wide. Two tunnels (approximately 122 meters long, 6 meters wide, and 6 meters tall) will provide heavy vehicle access to and from the LAPSC. An aboveground portion of the facility will provide administrative and utility support spaces. Special features of the facility include: power-operated physical security and blast-resistant doors, TEMPEST shielded rooms, seven (7) overhead bridge cranes (2 ton capacity), three (3) elevators, lightning protection system, grounding system, liquid waste collection/retention system, emergency air purge system, fire protection systems, and multiple HVAC systems. This project will also provide a new 1000 kW emergency generator (enclosed within a new hardened, reinforced concrete structure), two security guard towers, lightning protection, utilities, and other site improvements. The existing Limited Area perimeter fence, security zone, and patrol roads will be expanded to encompass the new LAPSC.

The underground complex is similar to the general design of the large underground nuclear weapons storage facility Kirtland AFB in New Mexico, known as Kirtland Underground Munitions Storage Complex (KUMSC) – except KUMSC appears to be four times bigger than the SWFPAC complex. It appears to include 10 weapons storage bays (each 30 x 8 meters; 98 x 26 feet) where nuclear W76 and W88 warheads in their containers will be stored when they’re not deployed on submarines (see image analysis below).

New underground nuclear weapons storage site at Naval Base Kitsap. Click to view full size.

The primary building contractor, Ammann & Whitney, describes the unique blast doors and gas-tight features intended to ensure the safe storage and handling of the nuclear weapons:

The structures are reinforced concrete containment structures designed to withstand both interior and exterior explosions. All exterior penetrations and blast doors are gas-tight. There are a total of 24 blast doors; 12 are located in the above ground structures and 12 in the buried structure. All 12 doors in the above ground structures are subject to exterior blast loads while seven are subject to additional internal gas loads. Of the 12 doors in the buried structure, six doors are subject to blast loads from both sides, the remaining six are subject to blast loads from one side only but three must be gas-tight. Penetrations from the buried structure are blast resistant and gas-tight.

Design of the complex began in 2002, construction in 2007, and by 2009 the excavation and main outlines were clearly visible on satellite images. The complex was completed in 2012. Construction required enormous amounts of concrete. Over an 18-month period between December 2008 and mid-2010, for example, two hundred cement trucks entered the base every two weeks.

Nuclear weapon at SWFPAC were previously stored in above-ground earth-covered bunkers, or igloos, from where they were transported to two above-ground handling facilities for maintenance or for loading onto Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles for deployment on operational SSBNs.

But the navy has concluded that a “single underground protected structure provides the most robust protection for fulfilling this mission against all threats.” With the completion of the underground complex, the old surface facilities (2 handling buildings and 21 igloos) will be demolished (see site outline above).

The US Navy plans to operate nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines at Naval Base Kitsap at least through 2080.

Over the next could couple of years the navy will “convert” four of the 24 missile launch tubes on each SSBN. The conversion will remove the capability to launch missiles from the four tubes, which no longer count under the New START treaty. The 384 excess warheads associated with the 24 missiles will likely be dismantled, leaving roughly 1,000 warheads at SWFPAC.

In the longer term (in the 2030s), the US Navy will transition to a new fleet of 12 SSBNs that will replace the current 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Each of the new submarines will only carry 16 missiles, a reduction of an additional four tubes from the 20 left on the New START compatible SSBNs. Assuming seven of the 12 new SSBNs will be based at Bangor, that will leave 112 missiles with an estimated 896 warheads at SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base, or a reduction of about one-third of the warheads currently stored there.

Despite these expected reductions, the Naval Base Kitsap complex (the SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base) will remain the largest and most important nuclear weapons base in the United States for the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Briefing to Arms Control Association Annual Meeting

Yesterday I gave a talk at the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting: Global Nuclear Challenges and Solutions for the Next U.S. President. A full-day and well-attended event that included speeches by many important people, including Ben Rhodes, who is Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications in the Obama administration.

My presentation was on the panel “Examining the U.S. Nuclear Spending Binge,” which included Mark Cancian from CSIS, Amy Woolf from CRS, and Andrew Weber, the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. I was asked to speak about the enhancement of nuclear weapons that happens during the nuclear modernization programs and life-extension programs and the implications these improvement might have for strategic stability.

My briefing described enhancement of military capabilities of the B61-12 nuclear bomb, the new air-launched cruise missile (LRSO), and the W76-1 warhead on the Trident submarines. The briefing slides are available here:

Nuclear Modernization, Enhanced Military Capabilities, and Strategic Stability.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Nuclear Stockpile Numbers Published Enroute To Hiroshima

The mushroom cloud rises over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, as the city is destroyed by the first nuclear weapon ever used in war.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Shortly before President Barack Obama is scheduled to arrive for his historic visit to Hiroshima, the first of two Japanese cities destroyed by U.S. nuclear bombs in 1945, the Pentagon has declassified and published updated numbers for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and warhead dismantlements.

Those numbers show that the Obama administration has reduced the U.S. stockpile less than any other post-Cold War administration, and that the number of warheads dismantled in 2015 was lowest since President Obama took office.

The declassification puts a shadow over the Hiroshima visit by reminding everyone about the considerable challenges that remain in reducing excessive nuclear arsenals – not to mention the daunting goal of eliminating nuclear weapons altogether.

Obama’s Stockpile Reductions

The declassified data shows that the stockpile as of September 2015 included 4,571 warheads. That means the Obama administration so far has reduced the stockpile by 702 warheads (or 13 percent) compared with the last count of the Bush administration.

Although 702 warheads is no small number (other than Russia, no other nuclear-armed state has more than 300 warheads), the reduction constitutes the smallest reduction of the stockpile achieved by any previous post-Cold War administration (see table).

The declassified 2015 number is about 100 warheads lower than the number we estimated in our latest Nuclear Notebook. The reason for the difference is that the number of warheads retired in 2014-2015 turned out to be higher than the average retirement in the previous three-year period. The increase probably reflects a quicker than anticipated retirement of excess warheads for the navy’s Trident missiles.

It can be deceiving to assess stockpile reduction performance by only comparing numbers of warheads. After all, there are significantly fewer warheads left in the stockpile today compared with 1991 (in fact, 14,437 warheads fewer!) so why wouldn’t the Obama administration be retiring fewer warheads than previous post-Cold War administrations?

To overcome that bias we also compare the reductions in terms of the percentage the stockpile size changed during the various administrations. But even so, the Obama administration’s performance comes in significantly below that of all other post-Cold War administrations (see table).

Obama’s Dismantlements

The declassified numbers also show that the Obama administration last year only dismantled 109 retired warheads. This is the lowest number of warheads dismantled in any year President Obama has been in office. And it appears to be the lowest number dismantled by the United States in one year since at least 1970.

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) says the poor performance in 2015 was due to “safety reviews, unusually high lightning events, and a worker strike at Pantex.”

But the decrease cannot be explained simply as disturbances. Although 2015 was unusually low, the Obama administration’s dismantlement record clearly shows a trendline of fewer and fewer warheads dismantled (see table).

Nuclear warhead dismantlement has decreased during the Obama administration. Click to view full size

There are currently roughly 2,300 retired warheads awaiting dismantlement, most of which were retired prior to 2009. NNSA says it plans to “increase weapons dismantlement by 20 percent starting in FY 2018” to be able to complete dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 before the end of September 2021.

With the Obama administration’s average of about 280 warheads dismantled per year, it will take at least until 2024 before the total current backlog is dismantled. The several hundred additional warheads that will be retired before then will take several additional years to dismantle.

Yet in the same time period NNSA has committed to several other big warhead jobs that will compete with dismantlement work over the capacity at Pantex, including: complete production of the W76-1 by 2019, start up production of the B61-12 and W88 Alt 370 in 2020, preparation for the start up of the W80-4 in 2025, as well as the ongoing disassembly and reassembly for inspection of the existing warhead types in the stockpile.

Conclusion and Recommendations

President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima takes place in the shadow of his nuclear weapons legacy: he has reduced the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile less than any other post-Cold War president and nuclear warhead dismantlement has declined on his watch.

For the arms control community (and that includes several important US allies, including Japan) the Obama administration’s modest performance on reducing the number of nuclear weapons – despite the New START Treaty – is a disappointment. Not least because the administration’s nuclear weapons modernization program has been anything but modest.

To be fair, it is not all President Obama’s fault. His vision of significant reductions and putting an end to Cold War thinking has been undercut by opposition ranging from Congress to the Kremlin. An entrenched and almost ideologically opposed Congress has fought his arms reduction vision every step of the way. And the Russian government has rejected additional reductions while New START is being implemented (although we estimate Russia during the Obama administration has reduced its own stockpile by more than 1,000 warheads).

Ironically, although Congress is vehemently opposed to additional nuclear reductions – certainly unilateral ones, the modernization plan Congress has approved has significant unilateral nuclear reductions embedded in it: a reduction of nuclear gravity bombs by one-half, a reduction of 48 sea-launched ballistic missiles beyond what’s planned under the New START Treaty, and unilateral reduction in the late-2020s of excess W76 warheads.

The Air Force wants to build a new and better nuclear air-launched cruise missile even though the mission can be covered by conventional cruise missiles or other nuclear weapons. President Obama should cancel or delay the program and pursue a global ban on nuclear cruise missiles.

Curiously, there seems to have been less resistance to stockpile reductions from the U.S. military. The Pentagon’s Defense Strategic Guidance from 2012, for example, concluded: “It is possible that our deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.”

Likewise, the Pentagon’s Nuclear Employment Strategy report sent to Congress in 2013 concluded that the nuclear force levels in place when the New START Treaty is fully implemented in 2018 “are more than adequate for what the United States needs to fulfill its national security objectives,” and that the United States “can ensure the security of the United States and our Allies and partners and maintain a strong and credible strategic deterrent while safely pursuing up to a one-third reduction in deployed nuclear weapons from the level established in the New START Treaty.”

And despite a significant turn for the worse in East-West relations, Russia is not increasing its nuclear arsenal but continuing to reduce it. But even if President Vladimir Putin decided to break out from the New START Treaty, the Pentagon concluded in 2012, Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” (Emphasis added.)

Those conclusions reveal a significant excess capacity in the U.S. nuclear arsenal that provides plenty of room for President Obama to do more in Hiroshima than simply remind of the dangers of nuclear weapons and reiterate the long-term vision of a world without them. Steps that he could and should take before leaving office include:

- Cancel plans to build a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (the LRSO) or delay the plans as part of a focused effort to get international support for a global ban on nuclear cruise missiles;

- Retire now the majority of the gravity bombs scheduled to be retired in mid/late-2020s;

- Reduce now the number of ballistic missiles on U.S. strategic submarines to the lower number already planned for the Ohio replacement submarine in the 2030s;

- Retire now the excess sea-launched ballistic missile warheads scheduled to be retired in the mid/late-2020s;

- Reduce the ICBM force below the 400 planned under New START, probably to 300 as recommended by STRATCOM when Obama first took office;

- Reduce the alert level of U.S. nuclear forces to reduce risk of accidents and incidents, motivate Russia to also reduce its alert level, and to pave the way for an international effort to prevent other nuclear-armed states from increasing the readiness of their nuclear forces.

These actions would help bring U.S. nuclear policy back on track, remove excess capacity in the nuclear arsenal, restore the credibility of its arms control policy, retain a Triad of long-range nuclear forces, provide plenty of reassurance to allies and friends, maintain strategic stability, and free up resources for conventional forces. If Obama doesn’t do it, President Hillary Clinton will have to clean up after him.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russian Increases and US Decreases

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Updated April 3, 2016] Russia continues to increase the number of strategic warheads it deploys on its ballistic missiles counted under the New START Treaty, according to the latest aggregate data released by the US State Department.

The data shows that Russia now has almost 200 strategic warheads more deployed than when the New START treaty entered into force in 2011. Compared with the previous count in September 2015, Russia added 87 warheads, and will have to offload 185 warheads before the treaty enters into effect in 2018.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed warheads and the data shows that the United States currently is counted with 1,481 deployed strategic warheads – 69 warheads below the treaty limit.

The Russian increase is probably mainly caused by the addition of the third Borei-class ballistic missile submarine to the fleet. Other fluctuations in forces affect the count as well. But Russia is nonetheless expected to reach the treaty limit by 2018.

The Russian increase of aggregate warhead numbers is not because of a “build-up” of its strategic forces, as the Washington Times recently reported, or because Russia is “doubling their warhead output,” as an unnamed US official told the paper. Instead, the temporary increase in counted warheads is caused by fluctuations is the force level caused by Russia’s modernization program that is retiring Soviet-era weapons and replacing some of them with new types.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data also shows that Russia is now counted as deploying exactly the same number of strategic launchers as when the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011: 521.

But Russia has far fewer deployed strategic launchers than the United States (a difference of 220 launchers) and has been well below the treaty limit since before the treaty was signed. The United States still has to dismantle 41 launchers to reach the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers.

The United States is counted as having 21 launchers fewer than in September 2015. That reduction involves emptying of some of the ICBM silos (they plan to empty 50) and denuclearizing a few excess B-52 bombers. The navy has also started reducing launchers on each Trident submarine from 24 missile tubes to 20 tubes. Overall, the United States has reduced its strategic launchers by 141 since 2011, until now mainly by eliminating so-called “phantom” launchers – that is, aircraft that were not actually used for nuclear missions anymore but had equipment onboard that made them accountable.

Again, the United States had many more launchers than Russia when the treaty was signed so it has to reduce more than Russia.

New START Counts Only Fraction of Arsenals

Overall, the New START numbers only count a fraction of the total nuclear warheads that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals. The treaty does not count weapons at bomber bases or central storage, additional ICBM and submarine warheads in storage, or non-strategic nuclear warheads.

Our latest count is that Russia has about 7,300 warheads, of which nearly 4,500 are for strategic and tactical forces. The United States has about 6,970 warheads, of which 4,670 are for strategic and tactical forces.

See here for our latest estimates: https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/

See analysis of previous New START data: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2015/10/newstart2015-2/

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Kalibr: Savior of INF Treaty?

By Hans M. Kristensen

With a series of highly advertised sea- and air-launched cruise missile attacks against targets in Syria, the Russian government has demonstrated that it doesn’t have a military need for the controversial ground-launched cruise missile that the United States has accused Russia of developing and test-launching in violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

Moreover, President Vladimir Putin has now publicly confirmed (what everyone suspected) that the sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can deliver both conventional and nuclear warheads and, therefore, can hold the same targets at risk. (Click here to download the Russian Ministry of Defense’s drawing providing the Kalibr capabilities.)

The United States has publicly accused Russia of violating the INF treaty by developing, producing, and test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a distance of 500 kilometers (310 miles) or more. The U.S. government has not publicly identified the missile, which has allowed the Russian government to “play dumb” and pretend it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about.

The lack of specificity has also allowed widespread speculations in the news media and on private web sites (this included) about which missile is the culprit.

As a result, U.S. government officials have now started to be a little more explicit about what the Russian missile is not. Instead, it is described as a new “state-of-the-art” ground-launched cruise missile that has been developed, produced, test-launched – but not yet deployed.

Whether or not one believes the U.S. accusation or the Russian denial, the latest cruise missile attacks in Syria demonstrate that there is no military need for Russia to develop a ground-launched cruise missile. The Kalibr SLCM finally gives Russia a long-range conventional SLCM similar to the Tomahawk SLCM the U.S. navy has been deploying since the 1980s.

What The INF Violation Is Not

Although the U.S. government has yet to publicly identify the GLCM by name, it has gradually responded to speculations about what it might be by providing more and more details about what the GLCM is not. Recently two senior U.S. officials privately explained about the INF violation that:

- it is not the R-500 cruise missile (Iskander-K);

- it is not the RS-26 road-mobile ballistic missile;

- it is not a sea-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not an air-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not a technical mistake;

- it is not one or two test slips;

- it is in development but has not yet been deployed.

Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. under secretary of state for and international security, said in response to a question at the Brookings Institution in December 2014: “It is a ground-launched cruise missile. It is neither of the systems that you raised. It’s not the Iskander. It is not the other one, X-100. Is that what it is? Yeah, I’ve seen some of those reflections in the press and it’s not that one.” [The question was in fact about the X-101, sometimes used as a designation for the air-launched Kh-101, a conventional missile that also exists in a nuclear version known as the Kh-102.]

The explicit ruling out of the Iskander as an INF violation is important because numerous news media and private web sites over the past several years have claimed that the ballistic missile (SS-26; Iskander-M) has a range of 500 km (310 miles), possibly more. Such a range would be a violation of the INF. In contrast, the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has consistently listed the range as 300 km (186 miles). Likewise, the cruise missile known as Iskander-K (apparently the R-500) has also been widely rumored to have a range that violates the INF, some saying 2,000 km (1,243 miles) and some even up to 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles). But Gottemoeller’s statement seems to undercut such rumors.

Gottemoeller told Congress in December 2015 that “we had no information or indication as of 2008 that the Russian Federation was violating the treaty. That information emerged in 2011.” And she repeated that “this it is not a technicality, a one off event, or a case of mistaken identity,” such as a SLCM launched from land.

Instead, U.S. officials have begun to be more explicit about the GLCM, saying that it involves “a state-of-the-art ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has tested at ranges capable of threatening most of [the] European continent and out allies in Northeast Asia” (emphasis added). Apparently, the “state-of-the-art” phrase is intended to underscore that the missile is new and not something else mistaken for a GLCM.

Some believe the GLCM may be the 9M729 missile, and unidentified U.S. government sources say the missile is designated SSC-X-8 by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

Forget GLCM: Kalibr SLCM Can Do The Job

Whatever the GLCM is, the Russian cruise missile attacks on Syria over the past two months demonstrate that the Russian military doesn’t need the GLCM. Instead, existing sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can hold at risk the same targets. U.S. intelligence officials say the GLCM has been test-launched to about the same range as the Kalibr SLCM.

Following the launch from the Kilo-II class submarine in the Mediterranean Sea on December 9, Putin publicly confirmed that the Kalibr SLCM (as well as the Kh-101 ALCM) is nuclear-capable. “Both the Calibre [sic] missiles and the Kh-101 [sic] rockets can be equipped either with conventional or special nuclear warheads.” (The Kh-101 is the conventional version of the new air-launched cruise missile, which is called Kh-102 when equipped with a nuclear warhead.)

The conventional Kalibr version used in Syria appears to have a range of up to 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles). It is possible, but unknown, that the nuclear version has a longer range, possibly more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles). The existing nuclear land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (SS-N-21) has a range of more than 2,800 kilometers (the same as the old AS-15 air-launched cruise missile).

The Russian navy is planning to deploy the Kalibr widely on ships and submarines in all its five fleets: the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula; the Baltic Sea Fleet in Kaliningrad and Saint Petersburg; the Black Sea Fleet bases in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk; the Caspian Sea Fleet in Makhachkala; and the Pacific Fleet bases in Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk.

The Russian navy is already bragging about the Kalibr. After the Kalibr strike from the Caspian Sea, Vice Admiral Viktor Bursuk, the Russian navy’s deputy Commander-in-Chief, warned NATO: “The range of these missiles allows us to say that ships operating from the Black Sea will be able to engage targets located quite a long distance away, a circumstance which has come as an unpleasant surprise to counties that are members of the NATO block.”

With a range of 2,000 kilometers the Russian navy could target facilities in all European NATO countries without even leaving port (except Spain and Portugal), most of the Middle East, as well as Japan, South Korea, and northeast China including Beijing (see map below).

As a result of the capabilities provided by the Kalibr and other new conventional cruise missiles, we will probably see many of Russia’s old Soviet-era nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles retiring over the next decade.

The nuclear Kalibr land-attack version will probably be used to equip select attack submarines such as the Severodvinsk (Yasen) class, similar to the existing nuclear land-attack cruise missile (SS-N-21), which is carried by the Akula, Sierra, and Victor-III attack submarines, but not other submarines or surface ships.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Now that Russia has demonstrated the capability of its new sea- and air-launched conventional long-range cruise missiles – and announced that they can also carry nuclear warheads – it has demonstrated that there is no military need for a long-range ground-launched cruise missile as well.

This provides Russia with an opportunity to remove confusion about its compliance with the INF treaty by scrapping the illegal and unnecessary ground-launched cruise missile project.

Doing so would save money at home and begin the slow and long process of repairing international relations.

Moreover, Russia’s widespread and growing deployment of new conventional long-range land-attack and anti-ship cruise missiles raises questions about the need for the Russian navy to continue to deploy nuclear cruise missiles. Russia’s existing five nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (SS-N-9, SS-N-12, SS-N-19, SS-N-21 and SS-N-22) were all developed at a time when long-range conventional missiles were non-existent or inadequate.

Those days are gone, as demonstrated by the recent cruise missile attacks, and Russia should now follow the U.S. example from 2011 when it scrapped its nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile. Doing so would reduce excess types and numbers of nuclear weapons.

Background:

- Russian Nuclear Forces, 2015, FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, 2015

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russia’s Open Skies Flights Prompt DIA “Concern”

Ideally, arms control agreements that are well-conceived and faithfully implemented will foster international stability and build confidence between nations. But things don’t always work out that way, and arms control itself can become a cause for suspicion and conflict.

“Can you say anything about how Russia, in this venue, is using their Open Skies flights over the United States?,” Rep. Mike Rogers (R-AL) asked Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) director Lt.Gen. Vincent R. Stewart at a February 3 hearing of the House Armed Services Committee (at page 13).

“The Open Skies construct was designed for a different era,” Lt.Gen. Stewart replied. “I am very concerned about how it is applied today. And I would love to talk about that in closed hearing,” he added mysteriously.

The Open Skies Treaty, to which the United States and Russia are parties, entered into force in 2002. It allows member states to conduct overflights of other members’ territories in order to monitor their military forces and activities.

It is unclear exactly what prompted DIA director Stewart’s concern about Russian overflights of the United States, and his perspective does not appear to be shared by some other senior Defense Department officials.

The most recent State Department annual report on arms control compliance identified several obstacles to U.S. overflights of Russia that it said were objectionable. The only issue relating to Russian overflights of the U.S. was that “Russia continued not to provide first generation duplicate negative film copies of imagery collected during Open Skies flights over the United States.”

But there seems to be more to the concerns about Russian overflights than that.

“Is it true that the Commander of U.S. European Command non-concurred last year when OSD-P asked for his input on approving Russian Federation requests under the Open Skies treaty?,” Rep. Rogers asked at another hearing on February 26 (at page 72).

That “was part of the deliberative process and was used to inform DOD and U.S. Government decision-making,” replied Brian McKeon of the Department of Defense. “As we worked with other U.S. departments and agencies, we determined that the specific concerns would be ameliorated by some important, separate components of the policy.” Both the specific concerns and the steps to ameliorate them were described in a classified letter that is not publicly available.

“USSTRATCOM’s capabilities are not significantly impacted by Open Skies overflights today, any more than we have been since the Treaty was implemented in 2002,” said Admiral Cecil D. Haney, Commander of U.S. Strategic Command.

“While the U.S. works with Russia on a number of broader concerns, Open Skies continues to serve as a fundamental transparency and confidence building measure in support of the Euro-Atlantic alliance,” Admiral Haney said.

* * *

Relatedly, on the subject of arms control compliance, the Congressional Research Service updated its report on Russian Compliance with the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: Background and Issues for Congress, October 13, 2015.

Other new and updated CRS reports that have been issued in the past week include the following.

Appropriations Subcommittee Structure: History of Changes from 1920 to 2015, updated October 13, 2015

Congressional Action on FY2016 Appropriations Measures, updated October 9, 2015

EPA Policies Concerning Integrated Planning and Affordability of Water Infrastructure, October 8, 2015

Issues in a Tax Reform Limited to Corporations and Businesses, October 8, 2015

Advance Appropriations, Forward Funding, and Advance Funding: Concepts, Practice, and Budget Process Considerations, updated October 8, 2015

Department of Labor’s 2015 Proposed Fiduciary Rule: Background and Issues, October 8, 2015

U.S.-South Korea Relations, updated October 8, 2015

Armed Conflict in Syria: Overview and U.S. Response, updated October 9, 2015

US Drops Below New START Warhead Limit For The First Time

By Hans M. Kristensen

The number of U.S. strategic warheads counted as “deployed” under the New START Treaty has dropped below the treaty’s limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time since the treaty entered into force in February 2011 – a reduction of 263 warheads over four and a half years.

Russia, by contrast, has increased its deployed warheads and now has more strategic warheads counted as deployed under the treaty than in 2011 – up 111 warheads.

Similarly, while the United States has reduced its number of deployed strategic launchers (missiles and bombers) counted by the treaty by 120, Russia has increased its number of deployed launchers by five in the same period. Yet the United States still has more launchers deployed than allowed by the treaty (by 2018) while Russia has been well below the limit since before the treaty entered into force in 2011.

These two apparently contradictory developments do not mean that the United States is falling behind and Russia is building up. Both countries are expected to adjust their forces to comply with the treaty limits by 2018.

Rather, the differences are due to different histories and structures of the two countries’ strategic nuclear force postures as well as to fluctuations in the number of weapons that are deployed at any given time.

Deployed Warhead Status

The latest warhead count published by the U.S. State Department lists the United States with 1,538 “deployed” strategic warheads – down 60 warheads from March 2015 and 263 warheads from February 2011 when the treaty entered into force.

But because the treaty artificially counts each bomber as one warhead, even though the bombers don’t carry warheads under normal circumstances, the actual number of strategic warheads deployed on U.S. ballistic missiles is around 1,450. The number fluctuates from week to week primarily as ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) move in and out of overhaul.

Russia is listed with 1,648 deployed warheads, up from 1,537 in 2011. Yet because Russian bombers also do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are artificially counted as one warhead per bomber, the actual number of Russian strategic warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles is closer to 1,590 warheads.

Because it has fewer ICBMs than the United States (see below), Russia is prioritizing deployment of multiple warheads on its new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). In contrast, the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carry a single warhead – although the missiles retain the capability to load the warheads back on if necessary. And the next-generation missile (GBSD; Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent) the Air Force plans to deploy a decade from now will also be capable of carry multiple warheads.

Warheads from the last MIRVed U.S. ICBM are moved to storage at Malmstrom AFB in June 2014. The sign “MIRV Off Load” has been altered from “Wide Load” on the original photo. Image: US Air Force.

This illustrates one of the deficiencies of the New START Treaty: it does not limit how many warheads Russia and the United States can keep in storage to load back on the missiles. Nor does it limit how many of the missiles may carry multiple warheads.

And just a reminder: the warheads counted by the New START Treaty are not the total arsenals or stockpiles of the United States and Russia. The total U.S. stockpile contains approximately 4,700 warheads (with another 2,500 retired but still intact warheads awaiting dismantlement. Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,500 warheads (with perhaps 3,000 more retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Deployed Launcher Status

The New START Treaty count lists a total of 762 U.S. deployed strategic launchers (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers), down 23 from March 2015 and a total reduction of 120 launchers since 2011. Another 62 launchers will need to be removed before February 2018.

Four and a half years after the treaty entered into force, the U.S. military is finally starting to reduce operational nuclear launchers. Up till now all the work has been focused on eliminating so-called phantom launchers, that is launchers that were are no longer used in the nuclear mission but still carry some equipment that makes them accountable. But that is about to change.

On September 17, the Air Force announced that it had completed denuclearization of the first of 30 operational B-52H bombers to be stripped of their nuclear equipment. Another 12 non-deployed bombers will also be denuclearized for a total of 42 bombers by early 2017. That will leave approximately 60 B-52H and B-2A bombers accountable under the treaty.

The Air Force is also working on removing Minuteman III ICBMs from 50 silos to reduce the number of deployed ICBMs from 450 to no more than 400. Unfortunately, arms control opponents in the U.S. Congress have forced the Air Force to keep the 50 empted silos “warm” so that missiles can be reloaded if necessary.

Finally, this year the Navy is scheduled to begin inactivating four of the 24 missile tubes on each of its 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The work will be completed in 2017 to reduce the number of deployed sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) to no more than 240, down from 288 missiles today.

Russia is counted with 526 deployed launchers – 236 less than the United States. That’s an addition of 11 launchers since March 2015 and five launchers more than when New START first entered into force in 2011. Russia is already 174 deployed launchers below the treaty’s limit and has been below the limit since before the treaty was signed. So Russia is not required to reduce any more deployed launchers before 2018 – in fact, it could legally increase its arsenal.

Yet Russia is retiring four Soviet-era missiles (SS-18, SS-19, SS-25, and SS-N-18) faster than it is deploying new missiles (SS-27 and SS-N-32) and is likely to reduce its deployed launchers more over the next three years.

Russia is also introducing the new Borei-class SSBN with the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM, but slower than previously anticipated and is unlikely to have eight boats in service by 2018. Two are in service with the Northern Fleet (although one does not appear fully operational yet) and one arrived in the Pacific Fleet last month. The Borei SSBNs will replace the old Delta III SSBNs in the Pacific and later also the Delta IV SSBNs in the Northern Fleet.

Russian Borei- and Delta IV-class SSBNs at the Yagelnaya submarine base on the Kola Peninsula. Click to open full size image.

The latest New START data does not provide a breakdown of the different types of deployed launchers. The United States will provide a breakdown in a few weeks but Russia does not provide any information about its deployed launchers counted under New START (nor does the U.S. Intelligence Community say anything in public about what it sees).

As a result, we can’t see from the latest data how many bombers are counted as deployed. The U.S. number is probably around 88 and the Russian number is probably around 60, although the Russian bomber force has serious operational and technical issues. Both countries are developing new strategic bombers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Four and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011, the United States has reduced its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads below the limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time. The treaty limit enters into effect in February 2018.

Russia has moved in the other direction and increased its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads and launchers since the treaty entered into force in 2011. Not by much, however, and Russia is expected to reduce its deployed strategic warheads as required by the New START Treaty by 2018. Russia is not in a build-up but in a transition from Soviet-era weapons to newer types that causes temporary fluctuations in the warhead count. And Russia is far below the treaty’s limit on deployed strategic launchers.

Yet it is disappointing that Russia has allowed its number of “accountable” deployed strategic warheads to increase during the duration of the treaty. There is no need for this increase and it risks fueling exaggerated news media headlines about a Russian nuclear “build-up.”

Overall, however, the New START reductions are very limited and are taking a long time to implement. Despite souring East-West relations, both countries need to begin to discuss what will replace the treaty after it enters into effect in 2018; it will expire in 2021 unless the two countries agree to extend it for another five years. It is important that the verification regime is not interrupted and failure to agree on significantly lower limits before the next Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2020 will hurt U.S. and Russian status.

Moreover, defining lower limits early rather than later is important now to avoid that nuclear force modernization programs already in full swing in both countries are set higher (and more costly) than what is actually needed for national security.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Modifying Arms Control Agreements, and More from CRS

Although it is theoretically possible to do so, the Senate has never imposed changes to an arms control treaty as a condition of ratification, according to a new Congressional Research Service report.

“The Senate has never conditioned consent to an arms control treaty’s ratification on changes in the terms of the agreement,” CRS said.

“In most cases, the conditions adopted during the Senate review were attached to resolutions of ratification and affected only U.S. activities, programs, and policies.” See Arms Control Ratification: Opportunities for Modifying Agreements, CRS Insights, September 2, 2015.

Another new CRS publication looks at the history of renegotiating arms control agreements, in the context of congressional debate over the pending Iran nuclear agreement.

“In the past 60 years, the United States has signed around 20 arms control agreements that affected U.S. weapons programs or military activities. In this period, the Senate has voted against giving its advice and consent to ratification of a treaty only once,” i.e. in the case of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty.

“It has, on three other occasions, not voted on treaties when it likely would have rejected the treaty. In only one of these three cases did the United States return to the negotiating table and modify the agreement to address the Senate’s concerns.”

In the latter case, which involved the Threshold Test Ban Treaty, “the new negotiations delayed [the Treaty’s] entry into force by nearly 15 years.” See Renegotiating Arms Control Agreements: A Brief Review, CRS Insights, September 2, 2015.

* * *

Three emerging technologies for defense of U.S. Navy surface ships are reviewed in a new report from the Congressional Research Service: shipboard lasers, the electromagnetic railgun, and hypervelocity projectile weapons.

“Any one of these new weapon technologies, if successfully developed and deployed, might be regarded as a ‘game changer’ for defending Navy surface ships against enemy missiles.”

“If two or three of them are successfully developed and deployed, the result might be considered not just a game changer, but a revolution,” the CRS report said.

“Rarely has the Navy had so many potential new types of surface-ship missile-defense weapons simultaneously available for development and potential deployment.”

However, any or all of the technologies might still prove to be a dead-end, and each still faces significant development hurdles. “Overcoming these challenges will likely require years of additional development work, and ultimate success in overcoming them is not guaranteed.”

The policy decision facing Congress today is therefore which if any of these approaches merits funding, and at what level. See Navy Lasers, Railgun, and Hypervelocity Projectile: Background and Issues for Congress, September 2, 2015.

* * *

The United States currently offers safe haven, or “temporary protected status,” to 5,000 Syrian nationals who have sought refuge from the conflict in that country. Altogether, the U.S. offers similar temporary protection to over 300,000 foreign nationals from 12 countries, a newly updated CRS report said. See Temporary Protected Status: Current Immigration Policy and Issues, updated September 2, 2015.

* * *

Other new or updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Long Range Strike Bomber Begins to Emerge, CRS Insights, September 2, 2015

What Does the Latest Court Ruling on NSA Telephone Metadata Program Mean?, CRS Legal Sidebar, September 3, 2015

Is Global Growth Slowing?, CRS Insights, September 2, 2015

Essential Air Service (EAS), September 3, 2015

Across-the-Board Rescissions in Appropriations Acts: Overview and Recent Practices, updated September 2, 2015

Coast Guard Polar Icebreaker Modernization: Background and Issues for Congress, updated September 2, 2015