The Pentagon’s 2019 China Report

[Updated] The Pentagon has released its 2019 version of its annual report on China’s military developments. The report describes a Chinese military in significant modernization. There is much to digest but this review only examines the nuclear portion.

The DOD report does not indicate how many nuclear warheads China has to arm these forces. Our current estimate for 2019 is approximately 290 warheads.

Although China’s nuclear arsenal is far smaller than that of Russia and the United States, the growing and increasingly capable Chinese nuclear arsenal is pushing the boundaries of China’s “minimum” deterrent and undercutting its promise that it “will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.” And the more the Chinese arsenal grows, the less likely it is that Russia and the United States will significantly reduce theirs.

Land-Based Missiles

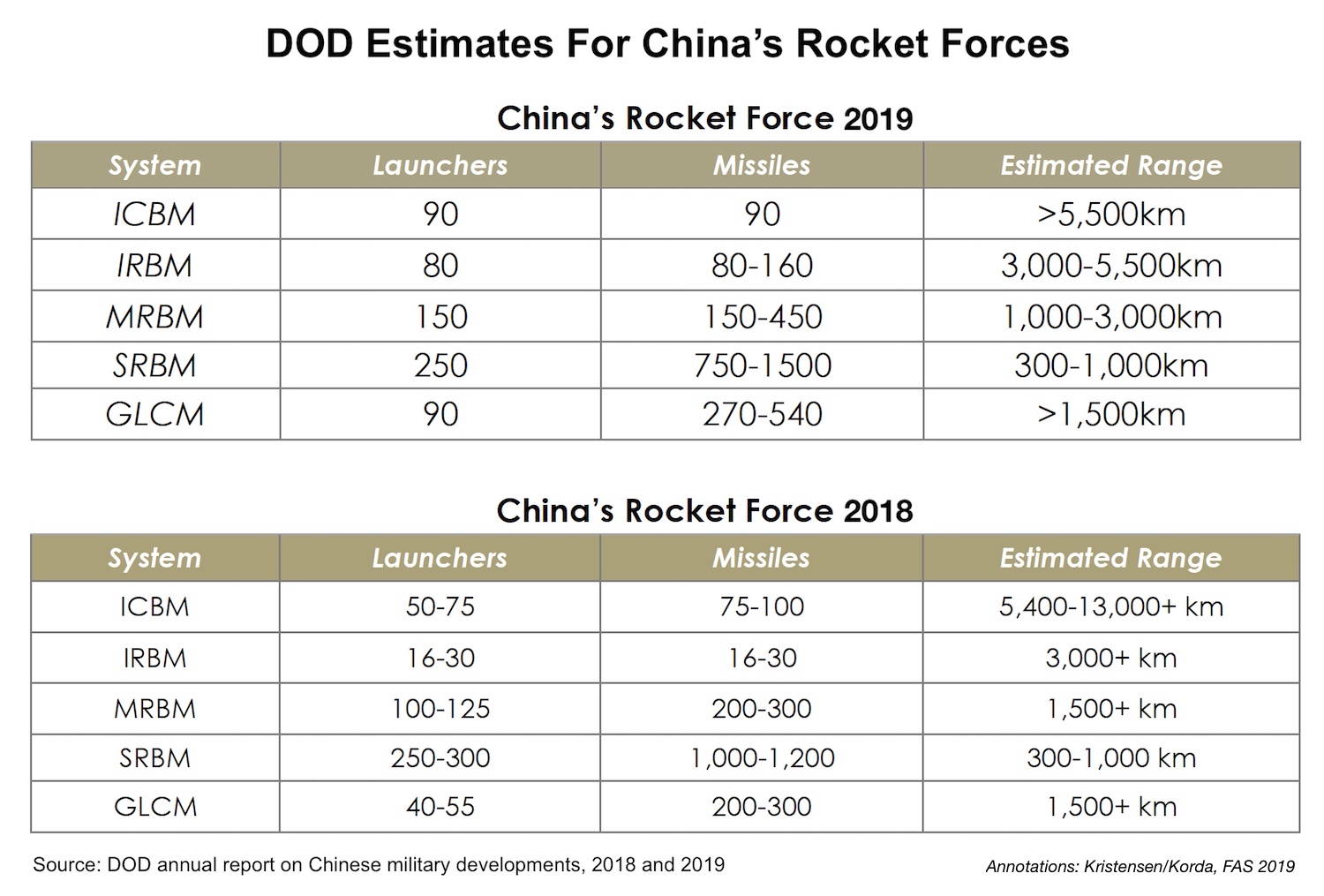

The DOD report describes a land-based missile force that is undergoing significant development with increases in almost all categories. China is clearly building up, even though it is still significantly below the nuclear force levels of Russia and the United States.

The report states that China now has 90 ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) with as many missiles. This is close to the 75-100 missiles reported for the past several years. But the number of launchers for those ICBMs is significantly higher this year: 90 versus the 50-75 listed in last year’s report. For that to be true, China would have fielded 15-40 new launchers, or the equivalent of two to six new brigades (assuming six launchers per ICBM brigade). Two or three new brigades seem more plausible so I suspect the range estimate is at the high end and might be 65-90. This increase is probably caused by the fielding of the improved road-mobile DF-31AG launcher.

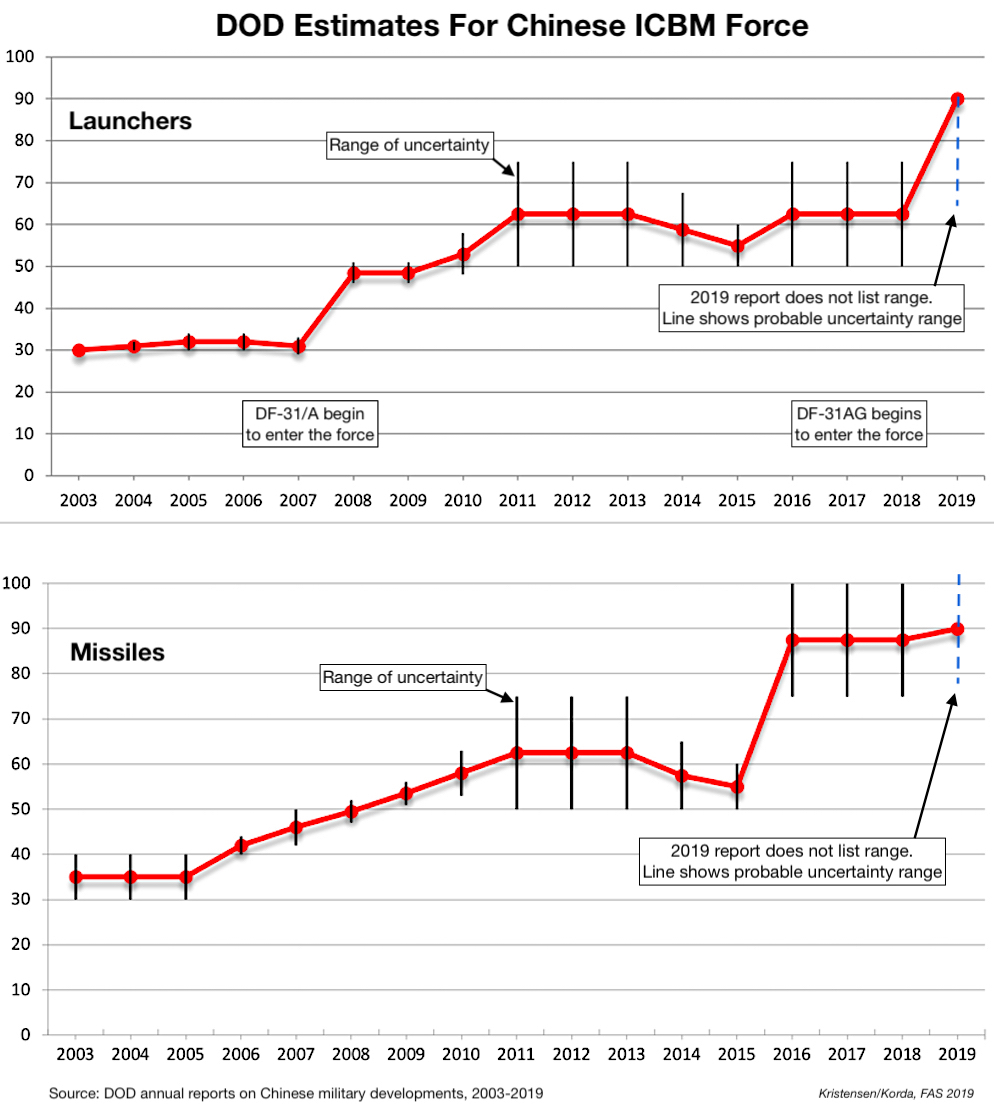

Each ICBM launcher normally is attributed one missile, except in previous years the DOD reports have presented more missiles than launchers. Part of that can be explained by the old liquid-fuel roll-out-to-launch DF-4, which is thought to have at least one reload. The DOD says the DF-4 is still operational, so it’s a mystery why the table doesn’t reflect that (all other missile categories are listed with a range instead of a single number). Since 2003, DOD’s estimates for Chinese ICBMs have fluctuated considerably:

DOD’s estimates for Chinese missiles have fluctuated considerably over the years. Click on graph to view full size.

The long-awaited road-mobile DF-41 ICBM is still not listed as operational but continues development. DOD has reported this system in development since at least 1997. Once it becomes operational, this solid-fuel missile might also replace the old liquid-fuel DF-5A/B in the silos. The DF-41 is said to be MIRV-capable, as is the DF-5B. The DOD report does not mention a DF-5C version that has been rumored in some outlets.

The most dramatic development is in the IRBM (intermediate-range ballistic missile) force, which has increased significantly since last year from 16-30 launchers to 80. That indicates the dual-capable DF-26 is being fielded more rapidly than anticipated, and might now be deployed at four bases. As with the ICBMs, the IRBM launcher estimate this year is a single number rather than a range used last year, which probably means that 80 is the upper number of a 65-80 range. The Chinese media in January 2019 described a DF-26 deployment that was later geo-located to a new missile training area in the Inner Mongolia province.

The MRBM (medium-range ballistic missile) force has also increased, mainly because of the fielding of conventional versions. The DOD report lists 150 MRBM launchers with 150-450 missiles available. This includes four versions – DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2), DF-21C (CSS-5 Mod 4), DF-21D (CSS-5 Mod 5), and DF-21E (CSS-5 Mod 6) – of which two are nuclear: DF-21A and DF-21E (note: DOD has not yet identified the CSS-5 Mod 6 as DF-21E but it is assumed given naming of other versions). Most of the MRBMs are conventional. The report does not reveal how many of the launchers are nuclear, but it might be no more than 40-50 of the 150 MRBM launchers. There appears to be a problem with the breakdown because the DOD report states elsewhere that “the PLA is fielding approximately 150-450 conventional MRBMs.” That would imply all missiles listed in the table are conventional, which is clearly not the case.

SRBMs (short-range ballistic missiles) constitute the largest group of Chinese missiles. The number of launchers is a little lower than last year, while the uncertainty about the number of missiles available for them has increased to 750-1,500 versus 1,000-1,200 in 2018. There are many rumors on the Internet that some of China’s SRBMs (DF-11, DF-15, and DF-16) have nuclear capability. But neither the DOD report nor NASIC attributes such a capability to this group of missiles. On the contrary, the DOD report explicitly states that these weapons are part of “China’s conventional missile force.”

Finally, DOD says China has increased its ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) force from 40-55 launchers in 2018 to 90 today. The missiles available for those launchers has increased from 200-300 to 270-540, so a significant uncertainty. The GLCM is not nuclear-capable.

The SSBN Fleet

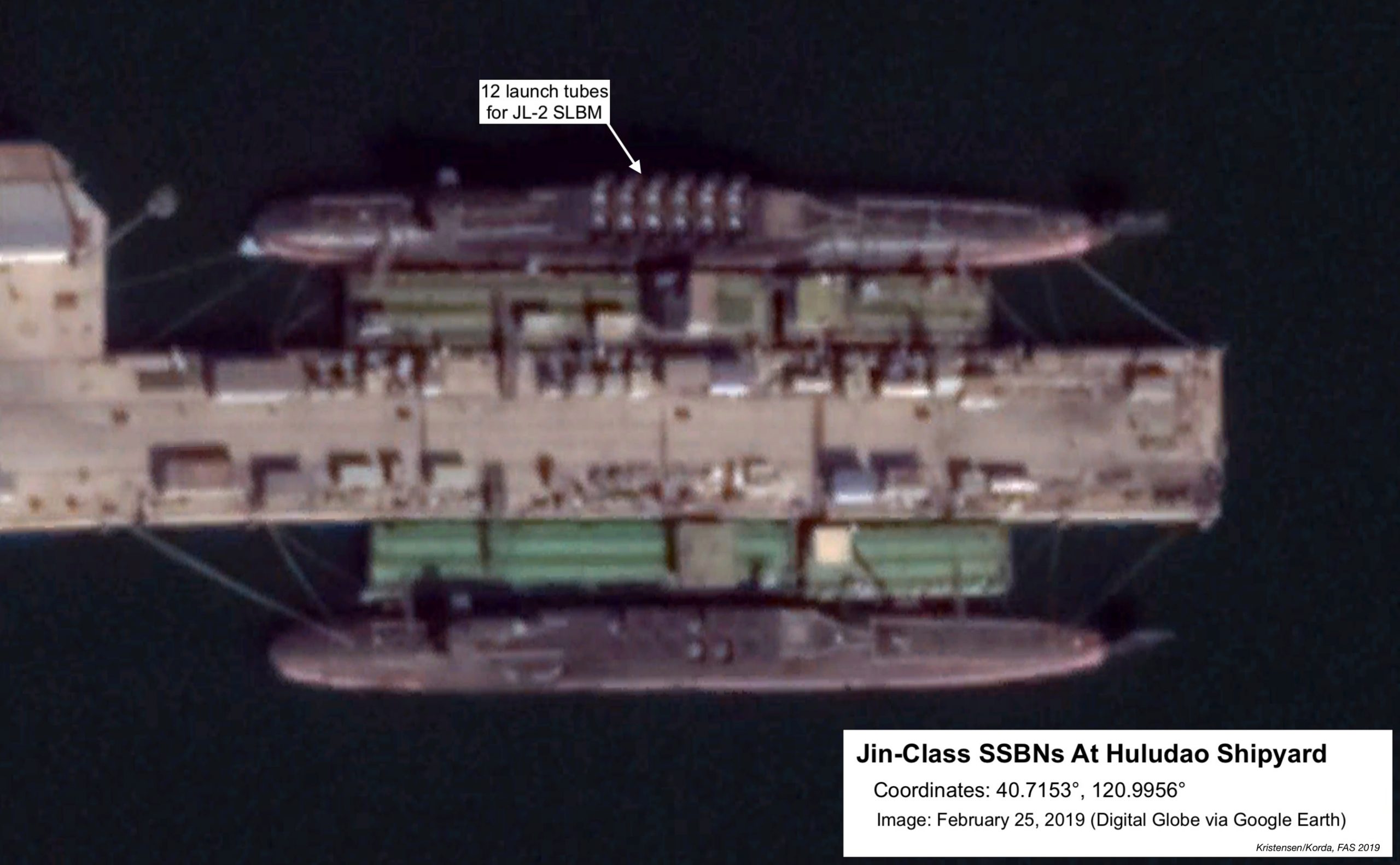

China currently operates four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs (nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines) with two more fitting out. The four operational SSBNs are all based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. The information about the fifth and sixth hulls is new and expands observations of a fifth hull in 2018. Once completed, this force will be capable of carrying up to 72 JL-2 SLBMs with as many warheads, 24 more than the four operational can currently carry.

The Pentagon report says the four operational SSBNs “represent China’s first credible, sea-based nuclear deterrent,” although the report doesn’t say if the submarines are armed with missiles under normal circumstances, if the warheads for those missiles are installed, or if the submarines sail on deterrent patrols.

The six Jin-class SSBNs will be followed by a next-generation SSBN known as Type 096, which DOD projects might begin construction in the early-2020s. The new SSBN class will carry the follow-on JL-3 SLBM but China will probably operate the two types concurrently.

The Bomber Force

The annual DOD reports have become more specific about the nuclear role of Chinese bombers in recent years. While the 2017 version said the “PLAAF does not currently have a nuclear mission,” the 2018 report said “the PLAAF has been newly re-assigned a nuclear mission” and that the “H-6 and future stealth bomber could both be nuclear capable.”

We have for years assessed that part of the Chinese H-6 bomber force had a dormant nuclear capability with a small number of bombs in storage. Aircraft, including the H-6, were used to deliver at least 12 of the nuclear weapons that China detonated in its nuclear testing program between 1965 and 1979, and a variety of what’s said to be tactical and strategic bombs can be seen displayed in Chinese museums.

The new report references unidentified “Chinese media” saying since 2016 that the upgraded H-6K is a dual nuclear-conventional bomber. The report says China is fielding the H-6K in greater numbers with land-attack cruise missiles and more efficient engines. Armed with cruise missiles, the H-6K can target Guam, the report says. Some H-6Ks are being equipped with air-refueling capability, and a new refuellable bomber is said to be in development that could reach initial operational capability before the next-generation H-20 bomber.

The DOD report does not identify any of China’s air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) as nuclear-capable. An Air Force Global Strike Command command briefing in 2013 listed the CJ-20 as nuclear-capable and a DOD fact sheet published along with the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review lists both nuclear ALCM and SLCM (sea-launched cruise missile) under China. But neither NASIC nor the public annual threat assessments from the Intelligence Community have attributed nuclear capability to Chinese ALCMs or SLCMs.

US officials have publicly identified two new Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles (ALBMs) in development, “one of which may include a nuclear payload.” The ALBM, designated by the US Intelligence Community as CH-AS-13, would be carried on a modified H-6 known as H-6N, potentially the new refuellable bomber that might become operational before the H-20.

These developments, if and when they become fully operational, would give China a real nuclear Triad for the first time.

The Road Ahead

In 2004, the Chinese government declared: “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China…possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.” The wording “nuclear-weapon states” probably referred to the five NPT-declared nuclear weapon states.

But the growing and increasingly capable Chinese nuclear arsenal is pushing the boundaries of China’s “minimum” deterrent and undercutting its promise that it “will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.”

China might not consider itself to be in a formal arms race with any particular country, but it is clear that the United States is seen as the primary driver. Since 2004, the size of China’s nuclear arsenal has surpassed that of Britain and we project that China in the near future will surpass France as the world’s third-largest nuclear-armed state – although it will still be far below the levels of the nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States.

President Trump recently declared his interest in including China in a future nuclear arms limitation agreement. His instinct is correct but it’s entirely unclear what he would offer China in return for limits on China’s nuclear forces, given how much smaller China’s arsenal is. Moreover, it should not be done at the expense of deciding now to extend the New START treaty with Russia. Indeed, China’s growing arsenal illustrate the importance of Russia and the United States maintaining existing arms control agreements and taking steps to reduce their arsenals further in consultations with China.

The Chinese leadership, however, can no longer hide behind the response: “Come down to our level. Then we’ll talk.” Beijing must be mindful that China’s growing nuclear arsenal – as well as its general military modernization and territorial pursuits – can serve to limit US willingness to reduce its arsenal further and may even lead to decisions to increase the capabilities. The Trump administration’s plan to abandon the INF treaty with Russia and add a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile to the arsenal are just two examples; they have China written all over it.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.