Understanding the Two Nuclear Peer Debate

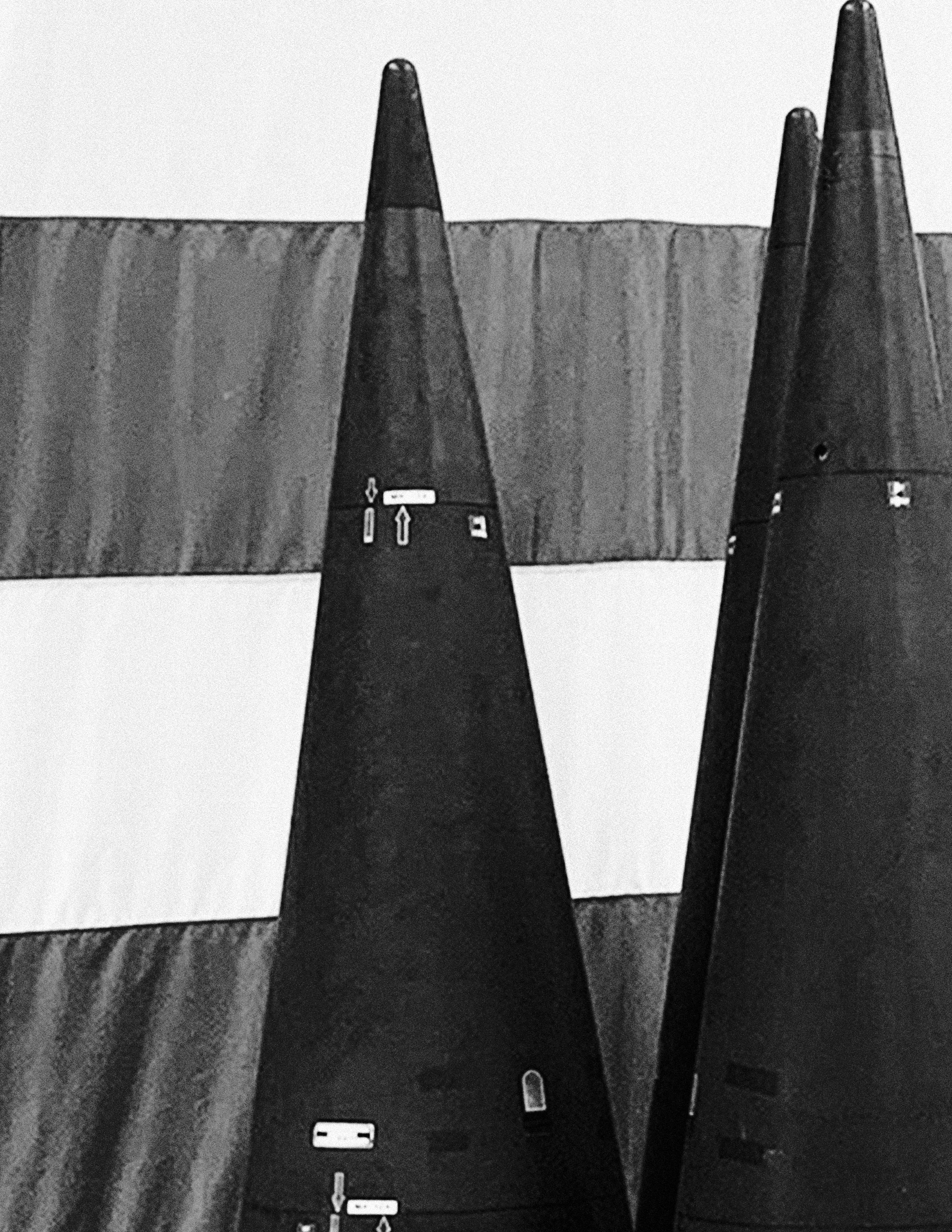

Since 2020, China has dramatically expanded its nuclear arsenal. That year, the Pentagon estimated China’s stockpile of warheads in the low 200s and projected that it would “at least double in size.”1 Two years later, the report warned that China would “likely field a stockpile of about 1500 warheads by its 2035 timeline.”2 Both inside and outside government, the finding has transformed discourse on U.S. nuclear weapons policy.

Adm. Charles Richard, while Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, warned that changes in China’s nuclear forces would fundamentally alter how the United States practices strategic deterrence. In 2021, Richard told the Senate Armed Services Committee that “for the first time in history, the nation is facing two nuclear-capable, strategic peer adversaries at the same time.”3 In his view, China is pursuing “explosive growth and modernization of its nuclear and conventional forces” that will provide “the capability to execute any plausible nuclear employment strategy.”4 In Richard’s view, the United States is facing a “crisis” of deterrence that will require major shifts in U.S. nuclear strategy.5 “We’re rewriting deterrence theory,” he told an audience.6 For Richard, the danger is not just that the United States would face two separate major power, nuclear-armed adversaries but two nuclear peers that can coordinate their actions or act to exploit opportunities created by the other.

How the United States responds to China’s nuclear buildup will shape the global nuclear balance for the rest of the century. For many observers, the “two nuclear peer problem” presents an existential choice because existing U.S. nuclear force structure and strategy cannot maintain deterrence against two nuclear peers simultaneously. There are only three options: expand the capability of U.S. nuclear force structure; shift nuclear strategy to engage nonmilitary targets;7 or do nothing, which increases the risk of regional aggression and nuclear use.

Despite this growing wave of concern and commentary, there has been no systematic studies that define the nature of the “two nuclear peer problem” and the options available to the United States and its allies for responding to China’s nuclear buildup. An informed decision about how to respond to China’s buildup will depend on answering two additional questions.

First, what exactly is the threat posed by China’s expanding nuclear forces? What is a “two nuclear peer problem” and will the United States face one in the next decade? Specifically, will China’s nuclear buildup render U.S. nuclear forces incapable of attaining critical objectives for deterring nuclear attacks.

Second, what are the best options for responding to China’s expanding nuclear forces? What are the available options to modify U.S. nuclear force structure given existing constraints and will these options effectively correct vulnerabilities created by a “two nuclear peer problem?” Would these options create new risks to the interests of the United States and its allies?

In the following chapters, we each consider a central aspect of the “two nuclear peer problem” and the options available to meet it. Though we have tried to coordinate our chapters so they do not overlap, and build on assumptions and data regarding U.S. and Chinese nuclear forces, each chapter is the work of a single author. We do not present a consensus perspective or set of recommendations and do not necessarily endorse the arguments made in neighboring chapters.

In chapter 2, Adam Mount surveys expert analysis and the statements of government officials to develop a more rigorous definition of the “two nuclear peer problem” than currently exists in the literature. Characterizing and categorizing the risks posed by a tripolar system leads to an unappreciated possibility: there is no “two nuclear peer problem” in the way that the problem is commonly presented. As it stands today, the prominent and influential discourse on the “two nuclear peer problem” does not clearly or accurately characterize the risks posed by China’s expanding nuclear forces, nor the range of options available to U.S. officials to respond. The need to deter two nuclear adversaries does not necessarily create a qualitatively new problem for U.S. strategic deterrence posture.

Subsequent chapters evaluate important pieces of the “two nuclear peer problem” in detail. In chapter 3, Hans Kristensen presents new estimates of U.S. and Chinese force structure to 2035. He provides correctives against excessive estimates of China’s current and future capability and argues it should not properly be considered a nuclear peer of the United States.

The final chapters consider two plausible ways that a tripolar system could present a qualitatively new threat to U.S. deterrence credibility. In chapter 4, Pranay Vaddi considers how China’s buildup will affect U.S. nuclear strategy. He surveys how U.S. planning has historically approached China and evaluates multiple courses of action for how the United States might adapt. In chapter 5, John Warden examines the prospects for Sino-Russian cooperation in peacetime, in crisis, in conventional conflict, and in a nuclear conflict. He argues that it is not only the material facts of China’s buildup that will drive U.S. planning, but the expectations and risk acceptance of U.S. officials with respect to Sino-Russian coordination and U.S. extended deterrence commitments.

The authors are grateful to Carnegie Corporation of New York for their generous funding of the project, as well as innumerable colleagues, academics, and government officials for informative discussions. The authors each write in an independent capacity. Their chapters do not reflect the positions of any organization or government.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.

While advanced Chinese language proficiency and cultural familiarity remain irreplaceable skills, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for successful open-source analysis on China’s nuclear forces.