We have the data to improve social services at the state and local levels. So how do we use it?

The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare for some what many already knew: the systems that our nation relies upon to provide critical social services and benefits have long been outdated, undersupported, and provide atrocious customer experiences that would quickly lead most private enterprises to failure.

From signing up for unemployment insurance to managing Medicaid benefits or filing annual tax returns, many frustrating interactions with government services could be improved by using data from user experiences and evaluating it in context with similar programs. How do people use these services? Where are customers getting repeatedly frustrated? At what point do these services fail, and what can we learn from comparing outcomes across different programs? Many agencies across the country already collect a huge amount of data on the programs they run, but fall short of adequately wielding that data to improve services across a wide range of social programs. Evaluating program data is necessary for providing effective social services, yet local and state governments face chronic capacity issues and high bureaucratic barriers to evaluating the data they have already collected and translating evaluation results into improved outcomes across multiple programs.

In a recent paper, “Blending and Braiding Funds: Opportunities to Strengthen State and Local Data and Evaluation Capacity in Human Services,” researchers Kathy Stack and Jonathan Womer deliver a playbook for state and local governments to better understand the limitations and opportunities for leveraging federal funding to build better integrated data infrastructure that allows program owners to track participant outcomes.

Good data is a critical component of delivering effective government services from local to federal levels. Right now, too much useful data lives in a silo, preventing other programs from conducting analyses that inform and improve their approach – state and local governments should strive to modernize their data systems by building a centralized infrastructure and tools for cross-program analysis, with the ultimate goal of improving a wide range of social programs.

The good news is that state and local governments are authorized to use federal grant money to conduct data analysis and evaluation of the programs funded by the grant. However, federal agencies typically structure grants in ways that make it difficult for states and localities to share data, collaborate on program evaluation, and build evaluation capacity across programs.

Interviews with leading programs in Colorado, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Rhode Island, and Washington revealed a number of different approaches that state and local governments have used to build and maintain integrated data systems, despite the challenges of working with multiple government programs. These range of approaches include: adopting a strong executive vision, working with external partners (such as research groups and universities), investing in building up a baseline capacity that enables higher level analytic work, delivering crucial initial analysis that motivated policy makers to deliver direct state funding, and (most notably) figuring out how to braid and blend funds from multiple federal grant sources. The programs in these states prove that it is possible to build a centralized system that evaluates outcomes and impacts across a range of government services.

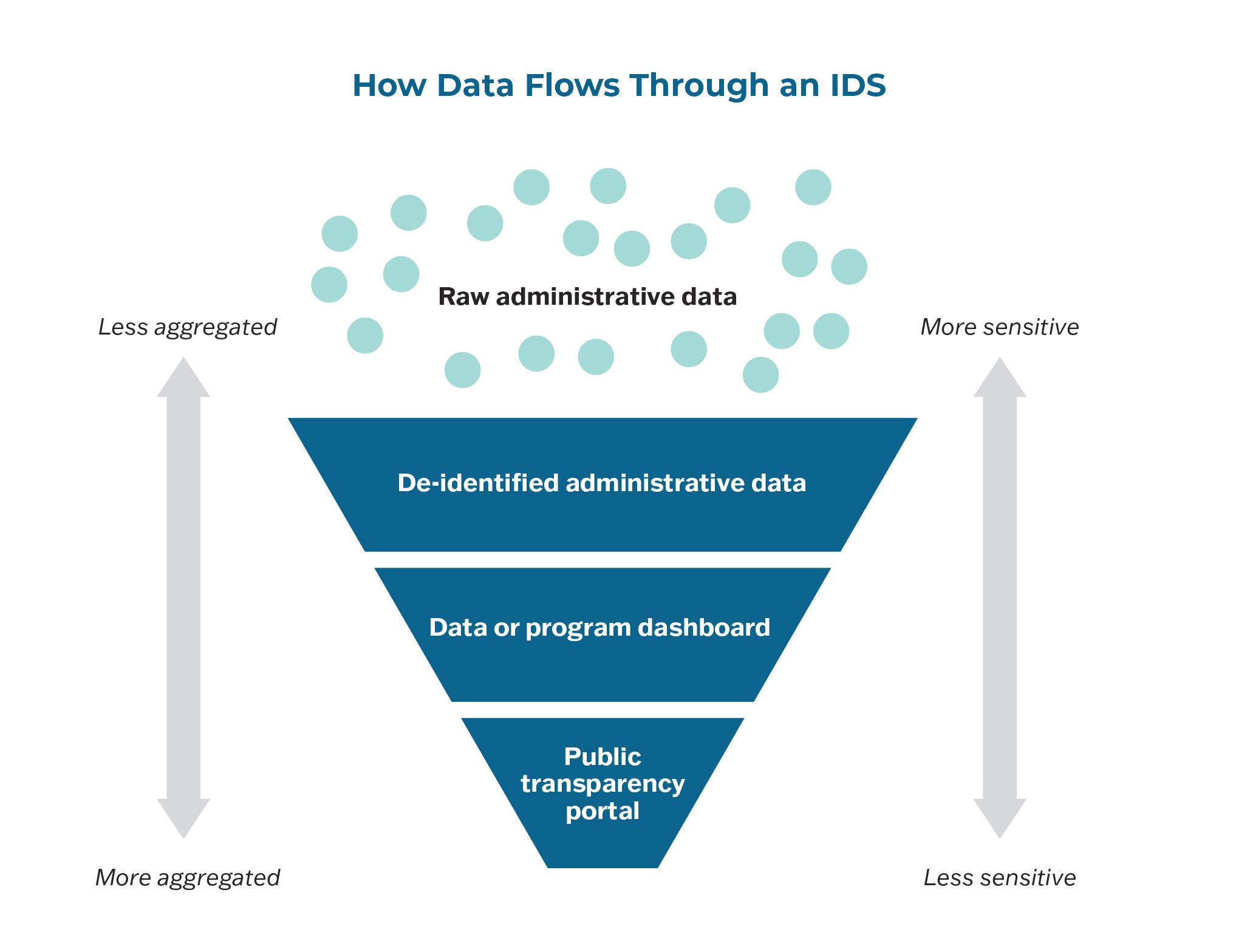

As data makes its way through an IDS, it is cleaned, verified, and matched with other data.

Stack and Womer lay out their menu of recommended options that states and localities can pursue in order to access federal funding for building data and evaluation capacity. These options include:

- stimulus funding from the American Rescue Plan’s State and Local Fiscal Recovery Fund and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act;

- program-specific funding that funds centralized capacity;

- direct state or local appropriations;

- funding on a project by project basis;

- cost allocation billing plans; and

- hybrid funding models.

The authors advocate for states and localities to both blend funds and braid funds, when appropriate, in order to fully leverage federal funding opportunities. Blended funds are sourced from multiple grants but lose their distinction upon blending; this type of federal funding requires statutory authority, and may have uniform reporting requirements. Alternatively, braided funds also come from separate sources, but remain distinct within the braided pot, with the original reporting, tracking, and eligibility requirements preserved from each source. Financing projects and programs via braiding funds is far more time-consuming, but it does not require special statutory authority.

While states and localities can strengthen and expand integrated data systems alone, the federal government should also take important steps to accelerate state and local progress. Stack and Womer point out a number of options that do not require legislative action. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and other federal agencies could issue clear guidance that recipients of federal grants must build and maintain efficient data infrastructure and analytics capacity that can support cross-program coordination and shared data usage. Regulatory and administrative actions like this would make it easier for states and localities to finance data systems via blending and braiding federal funds.

Integrated data systems are increasingly important tools for governments to achieve impact goals, avoid redundancy, and keep track of outcomes. State and local governments should take a page from Stack and Womer’s playbook and seek creative ways of using federal grants to build out existing data infrastructure into a modern system that supports cross-program analysis.

To secure the U.S. bio-infrastructure, maintain global leadership in biotechnology, and safeguard American citizens from emerging threats to their privacy, the federal government must modernize its approach to human genetic and biological data.

From use to testing to deployment, the scaffolding for responsible integration of AI into high-risk use cases is just not there.

The Federation of American Scientists supports Congress’ ongoing bipartisan efforts to strengthen U.S. leadership with respect to outer space activities.

By preparing credible, bipartisan options now, before the bill becomes law, we can give the Administration a plan that is ready to implement rather than another study that gathers dust.