US Deploys New Low-Yield Nuclear Submarine Warhead

The USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) at sea. The Tennessee is believed to have deployed on an operational patrol in late 2019, the first SSBN to deploy with new low-yield W76-2 warhead. (Picture: U.S. Navy)

The US Navy has now deployed the new W76-2 low-yield Trident submarine warhead. The first ballistic missile submarine scheduled to deploy with the new warhead was the USS Tennessee (SSBN-734), which deployed from Kings Bay Submarine Base in Georgia during the final weeks of 2019 for a deterrent patrol in the Atlantic Ocean.

The W76-2 warhead was first announced in the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) unveiled in February 2018. There, it was described as a capability to “help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable ‘gap’ in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities,” a reference to Russia. The justification voiced by the administration was that the United States did not have a “prompt” and useable nuclear capability that could counter – and thus deter – Russian use of its own tactical nuclear capabilities.

We estimate that one or two of the 20 missiles on the USS Tennessee and subsequent subs will be armed with the W76-2, either singly or carrying multiple warheads. Each W76-2 is estimated to have an explosive yield of about five kilotons. The remaining 18 missiles on each submarine like the Tennessee carry either the 90-kiloton W76-1 or the 455-kiloton W88. Each missile can carry up to eight warheads under current loading configurations.

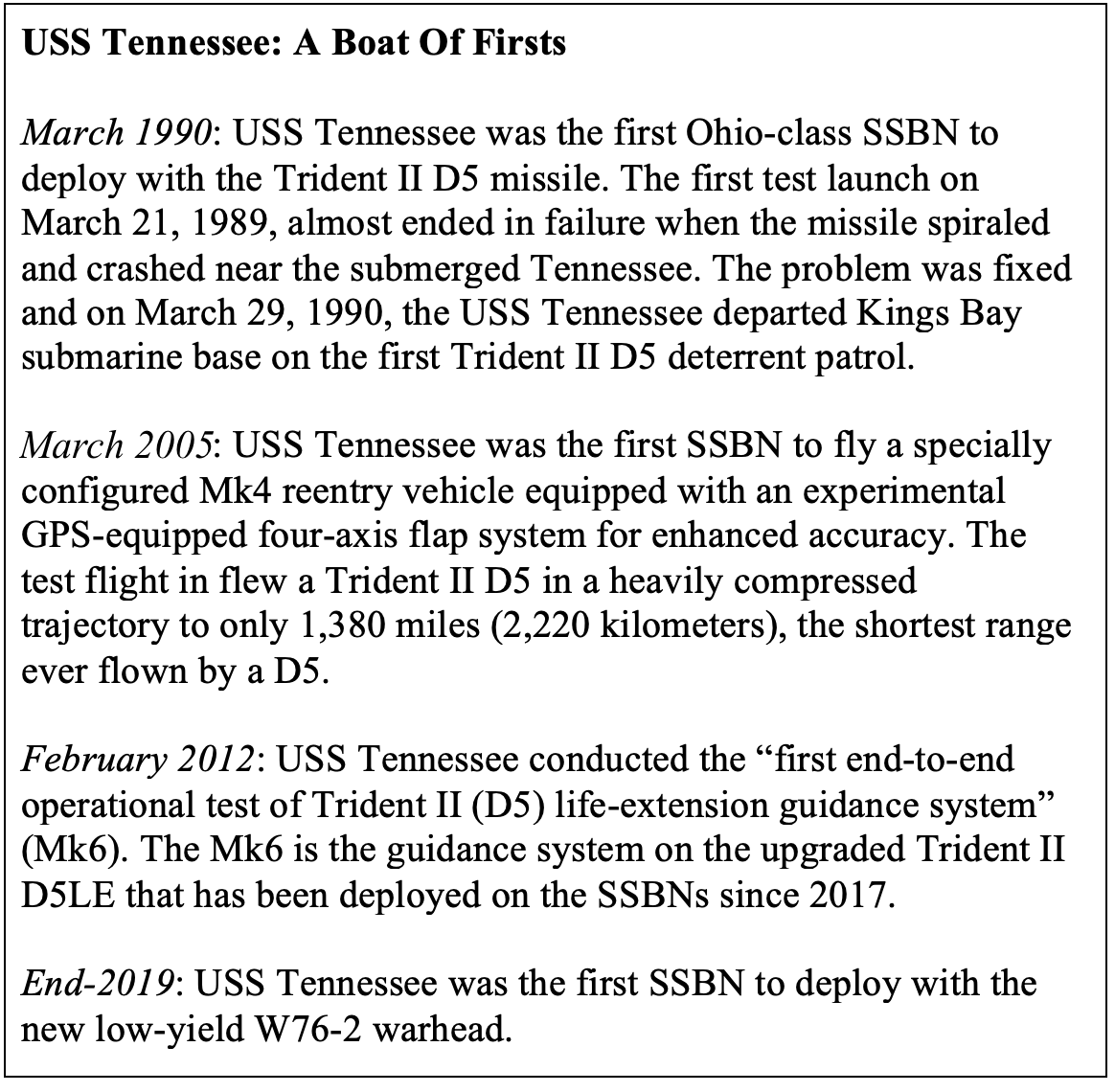

The first W76-2 (known as First Production Unit, or FPU) was completed at Pantex in February 2019. At the time, NNSA said it was “on track to complete the W76-2 Initial Operational Capability warhead quantity and deliver the units to the U.S Navy by the end of Fiscal Year 2019” (30 September 2019). We estimate approximately 50 W76-2 warheads were produced, a low-cost add-on to improved W76 Mod 1 strategic Trident warheads which had just finished their own production run.

The W76-2 Mission

The NPR explicitly justified the W76-2 as a response to Russia allegedly lowering the threshold for first-use of its own tactical nuclear weapons in a limited regional conflict. Nuclear advocates argue that the Kremlin has developed an “escalate-to-deescalate” or “escalate-to-win” nuclear strategy, where it plans to use nuclear weapons if Russia failed in any conventional aggression against NATO. The existence of an actual “escalate-to-deescalate” doctrine is hotly debated, though there is evidence that Russia has war gamed early nuclear use in a European conflict.

Based upon the supposed “escalate-to-deescalate” doctrine, the February 2018 NPR claims that the W76-2 is needed to “help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable ‘gap’ in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities.” The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has further explained that the “W76-2 will allow for tailored deterrence in the face of evolving threats” and gives the US “an assured ability to respond in kind to a low-yield nuclear attack.”

Consultants who were involved in producing the NPR have suggested that “[Russian President] Putin may well believe that the United States would not respond with strategic warheads that could cause significant collateral damage” and “that Moscow could conceivably engage in limited nuclear first-use without undue risk…”

There is no firm evidence that a Russian nuclear decision regarding the risk involved in nuclear escalation is dependent on the yield of a US nuclear weapon. Moreover, the United States already has a large number of weapons in its nuclear arsenal that have low-yield options – about 1,000 by our estimate. This includes nuclear cruise missiles for B-52 bombers and B61 gravity bombs for B-2 bombers and tactical fighter jets.

Yes, but – so the W76-2 advocates argue – these low-yield warheads are delivered by aircraft that may not be able to penetrate Russia’s new advanced air-defenses. But the W76-2 on a Trident ballistic missile can. Nuclear advocates also argue the United States would be constrained from employing fighter aircraft-based B61 nuclear bombs or “self-deterred” from employing more powerful strategic nuclear weapons. In addition to penetration of Russian air defenses, there is also the question of NATO alliance consultation and approval of an American nuclear strike. Only a low-yield and quick reaction ballistic-missile can restore deterrence, they say. Or so the argument goes.

All of this sounds like good old-fashioned Cold War warfighting. In the past, every tactical nuclear weapon has been justified with this line of argument, that smaller yields and “prompt” use – once achieved through forward European basing of thousands of warheads – was needed to deter. Now the low-yield W76-2 warhead gives the United States a weapon its advocates say is more useable, and thus more effective as a deterrent, really no change from previous articulations of nuclear strategy.

The authors of the NPR also saw the dilemma of suggesting a more usable weapon. They thus explained that the W76-2 was “not intended to enable, nor does it enable, ‘nuclear war-fighting.’ Nor will it lower the nuclear threshold.” In other words, while Russian low-yield nuclear weapons lower the threshold making nuclear use more likely, U.S. low-yield weapons instead “raise the nuclear threshold” and make nuclear use less likely. Undersecretary of Defense for Policy John Rood even told reporters that the W76-2 would be “very stabilizing” and in no way supports U.S. early use of nuclear weapons, even though the Nuclear Posture Review explicitly stated the warhead was needed for “prompt response” strike options against Russian early use of nuclear weapons.

“Prompt response” means that strategic Trident submarines in a W76-2 scenario would be used as tactical nuclear weapons, potentially in a first use scenario or immediately after Russia escalated, thus forming the United States’ own “escalate-to-deescalate” capability. The United States has refused to rule out first use of nuclear weapons.

The USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) in drydock at Kings Bay submarine base in September 2019 shortly before it returned to active duty and loaded with Trident D5 missiles carrying the new low-yield W76-2 warhead. (Photo: U.S. Navy)

Since the United States ceased allocating some of its missile submarines to NATO command in the late-1980s, U.S. planners have been reluctant to allocate strategic ballistic missiles to limited theater tasks. Instead, NATO’s possession of dual-capable aircraft and increasingly U.S. long-range bombers on Bomber Assurance and Deterrence Operations (BAAD) – now Bomber Task Force operations – have been seen as the most appropriate way to slow down regional escalation scenarios. The prompt W76-2 mission changes this strategy.

In the case of the W76-2, carried onboard a submarine otherwise part of the strategic nuclear force, amidst a war Russia would have to determine that a tactical launch of one or a few low-yield Tridents was not, in fact, the opening phase of a much larger escalation to strategic nuclear war. Thus, it seems inconceivable that any President would approve employment of the W76-2 against Russia; deployment on the Trident submarine might actually self-deter.

Though almost all of the discussion about the new W76-2 has focused on Russia scenarios, it is much more likely that the new low-yield weapon is intended to facilitate first-use of nuclear weapons against North Korea or Iran. The National Security Strategy and the NPR both describe a role for nuclear weapons against “non-nuclear strategic attacks, and large-scale conventional aggression.” And the NPR explicitly says the W76-2 is intended to “expand the range of credible U.S. options for responding to nuclear or non-nuclear strategic attack.” Indeed, nuclear planning against Iran is reportedly accelerating, B-2 bomber attacks are currently the force allocated but the new W76-2 is likely to be incorporated into U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) war planning.

Cheap, Quick, Simple, But Poorly Understood

In justifying the W76-2 since the February 2018 NPR, DOD has emphasized that production and deployment could be done fast, was simple to do, and wouldn’t cost very much. But the warhead emerged well before the Trump administration. The Project Atom report published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies in 2015 included recommendations for a broad range of low-yield weapons, including on long-range ballistic missiles. And shortly after the election of President Trump, the Defense Science Board’s defense priority recommendations for the new administration included “lower yield, primary-only options.” (This refers to the fact that the W76-2 is essentially little different than the strategic W76-1, “turning off” the thermonuclear secondary and thus facilitating rapid production.)

Initially, the military interest in a new weapon seemed limited. When then STRATCOM commander General John E. Hyten (now Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) was asked during Congressional hearings in March 2017 about the military need for lower-yield nuclear weapons, he didn’t answer with a yes or no but explained the U.S. arsenal already had a wide range of yields:

Rep. Garamendi: The Defense Science Board, in their seven defense priorities for the new administration, recommended expanding our nuclear options, including deploying low yield weapons on strategic delivery systems. Is there a military requirement for these new weapons?

Gen. Hyten: So Congressman, that’s a great conversation to tomorrow when I can tell you the details [in closed classified session], but from a — from a big picture perspective in — in a public hearing, I can tell you that our force structure now actually has a number of capabilities that provide the president of the United States a variety of options to respond to any numbers of threats.

Later that month, in an interview at the Military Reporters and Editors Conference, Hyten elaborated further that the United States already had very flexible military capabilities to respond to Russian use of tactical nuclear weapons:

John Donnelly (Congressional Quarterly Roll Call): The Defense Science Board, among others, has advocated development of new options for maneuvering lower yield nuclear warheads instead of just air delivered, talking basically about ICBM, SLBM. The thinking, I think, is that given the Russian escalate to win, if you like, or escalate to deescalate doctrine, the United States needs to have more options. What do you think about, that is my question. Especially in light of the fact that there are those who are concerned that this further institutionalizes the idea that you can fight and maybe even win a limited nuclear war.

Gen. Hyten: …we’re going to look at that in the Nuclear Posture Review over the next six months. I think it’s a valid question to ask, but I’ll just tell you what I’ve said in public up until this point, and as we go into the Nuclear Posture Review.

…in the past and where I am right now is that I’ll just say that the plans that we have right now, one of the things that surprised me most when I took command on November 3 was the flexible options that are in all the plans today. So we actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, which is the Attorney General, Secretary of State and everybody, I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the President on to give him options on what he would want to do.

So I’m very comfortable today with the flexibility of our response options. Whether the President of the United States and his team believes that that gives him enough flexibility is his call. So we’ll look at that in the Nuclear Posture Review. But I’ve said publicly in the past that our plans now are very flexible.

And the reason I was surprised when I got to STRATCOM about the flexibility, is because the last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive. … We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing. So I’m comfortable with where we are today, but we’ll look at it in the Nuclear Posture Review again.

During the Trump NPR process, however, the tone changed. Almost one year to the day after Hyten said he was comfortable with the existing capabilities, he told lawmakers he needed a low-yield warhead after all: “I strongly agree with the need for a low-yield nuclear weapon. That capability is a deterrence weapon to respond to the threat that Russia, in particular, is portraying.”

While nuclear advocates were quick to take advantage of the new administration to get approval for new nuclear weapons they said were needed to now respond to Russia’s supposed “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy, efforts to engage Moscow to discuss nuclear strategy and their impact on nuclear arsenals are harder to find. See, for example, this written correspondence between Representative Susan Davis and General Hyten:

Rep. Davis: Have you ever had a discussion with Russia about their nuclear posture, and in particular an escalate-to-de-escalate (E2D) strategy, which the Nuclear Posture Review claims is part of Russia’s nuclear doctrine? How did they respond? Do you view this doctrine as offensive or defensive in nature?

Gen. Hyten: I would like to have such a discussion, but I have never had a conversation with Russia about their nuclear posture.

During the Fiscal Year 2019 budget debate, Democrats argued strongly against the new low-yield W76-2, and opposition increased on Capitol Hill after the 2018 mid-term elections gave Democrats control of the House of Representatives. But given the relatively low cost of the W76-2, and the fact that it was conveyed as merely an “add-on” to an already hot W76 production line, little progress was made by opponents. Reluctantly accepting production of the warhead in the FY 2019 defense budget, opponents again in August 2019 tried to block funding in the FY 2020 defense budget arguing the new warhead “is a dangerous, costly, unnecessary, and redundant addition to the U.S. nuclear arsenal,” and that it “would reduce the threshold for nuclear use and make nuclear escalation more likely.” When the Republican Senate majority refused to accept the House’s sense, Democrats caved.

Just a few months later, the first W76-2 warheads sailed into the Atlantic Ocean onboard the USS Tennessee.

* William M. Arkin is a journalist and consultant to FAS

For a detailed overview of the U.S. nuclear arsenal, see our latest Nuclear Notebook: United States nuclear forces, 2020

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.