The Minot Investigations: From Fixing Problems to Nuclear Advocacy

|

| The second report from the Schlesinger Task Force goes beyond fixing nuclear problems to promoting new nuclear weapons. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

For nuclear weapon advocates, the Minot incident in August 2007, where the Air Force lost track of six nuclear-armed cruise missiles for 36 hours, was a gift sent from heaven. No other event short of a nuclear attack against the United States could have provided a better opportunity to breathe new life into the declining nuclear mission.

But where is the line between fixing problems and advocacy?

Although the latest report from the Secretary of Defense Task Force on DOD Nuclear Weapons Management, also known as the Schlesinger report, contains many reasonable recommendations to ensure that the Services and agencies are capable of fulfilling the nuclear mission, it is also sprinkled with recommendations that have more to do with promoting nuclear weapons.

And it makes some remarkable claims about the deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Fuzzy Tasking Leads to Fuzzy Focus

The leap from investigation to promotion is an unfortunate byproduct of the tasking Defense Secretary Robert Gates provided to the Schlesinger Task Force in June 2008. That letter not only directed the task force to examine accountability and control procedures for nuclear weapons to “sustain public confidence in the safe handling of DoD nuclear assets,” but also to “bolster a clear international understanding of the continued role and credibility of the U.S. nuclear deterrent.”

The task force appears to have taken the second objective a bit far.

Rather than being focused on fixing the problems that resulted in the Minot incident and several other events, the report reads like a second volume of the Defense Science Board (DSB) report from 2006 in which disgruntled nuclear advocates lamented a decline in support for the nuclear mission.

The Schlesinger report is, at times, a phenomenal concoction of Cold War nuclear jargon and claims made without presenting any evidence or analysis to support their continued validity. The report skips over the expansion from deterring nuclear to deterring all forms of WMD (it doesn’t even list the difference), and it suggests that U.S. nuclear weapons even have a mission against “violent extremists and nonstate actors.”

Nuclear Promotions

Anticipating that some elements of the nuclear posture will probably be cut in the future as a result of the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission, the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, and an potential arms control agreement with Russia, the Schlesinger report correctly states that such cuts “should be a reflection of policy decisions at the highest level rather than a result of Service preferences or budgetary concerns.” Given this conclusion, it is all the more noteworthy how the Schlesinger report throws itself into a blunt advocacy of nuclear posture issues that clearly should be the purview of the next administration.

Examples of posture recommendations that go beyond “accountability and control procedures” to promotion of new nuclear weapons include:

* Develop follow-on capabilities that can come online prior to expiration of the nuclear Tomahawk Land Attack Missile (TLAM-N) effectiveness or, should there be a gap, extend the TLAM-N service life commensurate with introduction of the new system.

* The Secretary of Defense should direct the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to develop validated operational requirements for modernizing or replacing the capabilities now provided by Dual-Capable Aircraft (DCA), Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), and TLAM-N.

* Review and update the concept of operations for the TLAM-N to make it a more viable and responsive option for national leadership.

Clearly, these appear to be future posture decisions that are beyond the job the Schlesinger Task Force was asked to do.

The Extended Deterrence Confusion

The TLAM and DCA are weapons that are weapon systems that are both have roles in the extended deterrence mission. Yet the authors of the Schlesinger report repeatedly confuse the description of what extended deterrence means. Sometime they describe it as forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. At other times they describe as a nuclear umbrella extended over allies from afar.

For example, in the opening paragraphs of the section called “The Special Case of NATO,” the report concludes: “As long as NATO members rely on U.S. nuclear weapons for deterrence, no action should be taken to remove them without a thorough and deliberate process of consultation.”

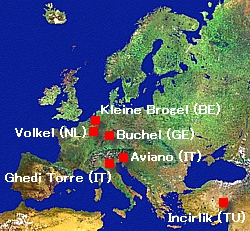

Certainly NATO members should be consulted, but withdrawing “them” (which refers to the roughly 200 tactical nuclear bombs deployed in five European countries) hardly constitutes eliminating the entire U.S. nuclear weapons deterrent. A withdrawal from Europe would not be the end of the nuclear umbrella, as the Schlesinger report indicates, which could be continued by long-range forces just like it was in the Pacific after tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from South Korea in 1991.

|

Figure 1: |

|

|

About 200 U.S. tactical nuclear weapons are deployed at six bases in five European countries. After the Blue Ribbon Review report in 2008 concluded that it would take considerable additional resources for security at European nuclear sites to meet DOD standards, the Schlesinger report now concludes that everything is fine. |

The Deployment in Europe

One of the most interesting parts of the report concerns the deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe. Unfortunately, the European section is filled with sweeping statements and conclusions about the virtues of the deployment that are not supported by any accompanying analysis except deterrence jargon and echoes from the Cold War:

“Much of the deterrent value of NATO’s DCA deployment is derived from their in-theater presence, demonstrating and maintaining the capability to employ them. This creates in the minds of potential aggressors an unacceptable level of uncertainty concerning the success of any contemplated attack on NATO. This deterrent effect cannot be created by simply having nuclear weapons stored and locked up or relying exclusively on “over-the-horizon” nuclear delivery capabilities.”

It is? It does? It cannot? Why?

Many actually do believe – including apparently U.S. European Command (EUCOM) – that the deployment in Europe is not necessary anymore. But the authors of the Schlesinger report do not share that view and they spend a good portion of the report criticizing EUCOM for believing that “deterrence provided by USSTRATCOM’s strategic nuclear capabilities outside of Europe are more cost effective” and that “an ‘over the horizon’ strategic capability is just as credible.”

That assessment sounds pretty sound to me. But instead of accepting EUCOM’s assessment that forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe is not necessary for extended deterrence and a burden on real-world nonnuclear operations, the Schlesinger report brushes aside EUCOM’s “narrow assessment.” It is a much broader issue, the authors’ claim, about Russia, flexible regional nuclear deterrence (although the weapons are not targeted against anyone), and a trans-Atlantic link between Europe and the United States. But as far as the tactical nuclear weapons in Europe are concerned, that link was a Cold War link between a Soviet conventional invasion of Europe and U.S. strategic nuclear weapons, a concept that is getting a little dated. And if the glue in NATO depends on forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons, then I think the alliance is in deeper trouble that people normally think.

Interestingly, one person who shares the view of EUCOM was recently selected to become national security advisor to President-elect Barack Obama: General James L. Jones. When he was the head of EUCOM and Supreme Allied Commander Europe in 2005, the New York Times reported that Jones “has privately told associates that he favors eliminating the American nuclear stockpile in Europe, but has met resistance from some NATO political leaders.”

|

Figure 2: |

|

| Unlike the authors of the Schlesinger report, General (Ret.) James Jones, who is President-elect Obama’s national security advisor and former Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR), reportedly favors a withdrawal of tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. |

.

Shortly before the U.S. in 2005 and 2006 secretly withdrew half of the nuclear weapons from Europe – including all weapons from the United Kingdom, Jones told a Belgian Senate committee: “The reduction will be significant. Good news is on the way.” NATO sources attempted to downplay the issue by claiming Jones had not mentioned nuclear weapons specifically, but the Belgian government later stated for the record that, “the United States has decided to withdraw part of its nuclear arsenal deployed in Europe….” German weekly Der Spiegel followed up by asking “whether German nuclear weapons sites will benefit from Gen. Jones’ ‘good news.’” They did: all weapons were withdrawn from Ramstein Air Base.

The authors also leave out that the European political landscape on the tactical nuclear weapons issue has changed dramatically since the justifications the authors use were concocted. An overwhelming majority of the public today favors a withdrawal, the German government parties favor a withdrawal, and the Belgium Senate has unanimously called for a withdrawal. While ignoring those views, the Schlesinger report instead refers to anonymous allies who allegedly have expressed concern over calls for a unilateral withdrawal.

Who are those allies? From what department in the government bureaucracies did the officials that sent those signals come from? Whenever I mention these “allied concerns” during conversations with European government officials, they always smile because they know quite well that what’s a play here is a small group of nuclear bureaucrats deep within the ministries of defense who are defending their own turf. [There are some hints here; none of them seem to be directly related to the deployment in Europe].

Extended Deterrence as Nonproliferation

Another prominent assertions in the NATO section of the report is that by holding a nuclear umbrella over allied countries – by promising to retaliate with nuclear weapons if they are attacked by nuclear weapons (or weapons of mass destruction, as the authors say) – U.S. nuclear weapons prevent allied countries from developing nuclear weapons themselves. This sure sounds good and is a popular claim, but how widespread is this effect.

The report states that the United States has “extended its nuclear protective umbrella to 30-plus friends and allies.” The countries are not identified, but most of them are known:

NATO (25): Albania, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Turkey.

ANZUS (2): Australia, New Zealand.

Northeast Asia (3): Japan, South Korea, Taiwan .

That’s 30, so who are the remaining -plus countries are that the authors say are covered by the U.S. umbrella? France and the U.K. obviously don’t need it because they have their own nuclear deterrents. So do Israel and India. Are there non-nuclear allies in the Middle East that are under the umbrella?

|

Figure 3: |

|

|

A NATO briefing in 2006 acknowledged serious pressure for a withdrawal of nuclear weapons. Click image to download. |

The Schlesinger report recommends that the views of those 30-plus countries should be included in U.S. nuclear policy guidance documents. That would indeed be interesting, given that many of the countries actually have policies that favor a total withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Europe, elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons, and total nuclear disarmament – political realities the report completely leave out.

Although all 30-plus are used to underscore the virtue of extended deterrence, how many of them would seriously consider acquiring their own nuclear weapons if things changed? Denmark? Iceland? Lithuania? Luxembourg? Portugal? New Zealand? Seriously! Only a few of the 30 are normally considered potential nuclear weapon proliferators: Germany, Japan, and perhaps South Korea.

It is probably also worth mentioning that two NATO countries – France and the United Kingdom – decided years ago to go nuclear even though the United States had thousands of nuclear weapons deployed to defend them. The report doesn’t mention why the NATO countries would not feel sufficiently protected by British or French nuclear forces in Europe.

The report also doesn’t mention that the United States since the early-1990 has maintained a nuclear umbrella over its allies in Northeast Asia without it requiring forward deployment of tactical nuclear weapons in those countries. Why is it possible to maintain extended deterrence with long-range nuclear weapons in the Pacific but not in Europe?

Conclusions and Remarks

Obviously the virtues of extended deterrence and the deployment in Europe are a little more nuanced than the Schlesinger report purports. But the central proposition that NATO and extended deterrence will go down the tube if tactical nuclear weapons were withdrawn from Europe seems preposterous.

It asks us to believe that if NATO really were attacked or threatened with nuclear (or, for those who believe nuclear weapons are also needed to deter chemical or biological weapons, WMD), U.S., British, and French ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), land-based missiles (ICBMs), and long-range bombers – along with all of NATO combined conventional military might (which is far more credible as a deterrent) – would sit idle in their bases because the political and military leaders somehow were incapable of reacting.

The decline in nuclear prowess that the Minot investigations have detected hasn’t simply happened because overstretched officers failed to do their job or the nation lost faith in nuclear weapons. It is a symptom, a hint. It has declined because nuclear weapons are no longer center and square to the national security of the United States nor its foreign policy. For sure, nuclear weapons haven’t gone away and there are still many challenges, but there are elements of the nuclear mission that are no longer essential and can and should be reassessed.

But the Minot investigations haven’t done that. Instead they have gone beyond fixing safety and security issues to using the incident to reaffirm status quo and reject change. Hopefully the Congressional Strategic Posture Commission and the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review can do better.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.