Despite Obfuscations, New START Data Shows Continued Value Of Treaty

The latest set of New START treaty aggregate data released by the US State Department shows Russia and the United States continue to abide by the limitations of the New START treaty. The data shows that Russia and the United States combined have cut a total of 429 strategic launchers since February 2011, reduced the number of deployed launchers by 223, and reduced the number of warheads attributed to those launchers by 511.

The good news comes despite efforts by officials in Moscow and Washington to create doubts about the value of New START by complaining about lack of irreversibility, weapon systems not covered by the treaty, or other unrelated treaty compliance and behavioral matters. These complaints are part of the ongoing bickering between Russia and the United States and appear intended – they certainly have that effect – to create doubt about the value of extending New START for five years beyond 2021.

Playing politics with New START is irresponsible and counterproductive. While the treaty has facilitated coordinated and verifiable reductions and provides for on-site inspections and a continuous exchange of notifications about strategic offensive nuclear forces, the remaining arsenals are large, undergoing extensive modernizations, and demand continued limits and verification.

By the Numbers

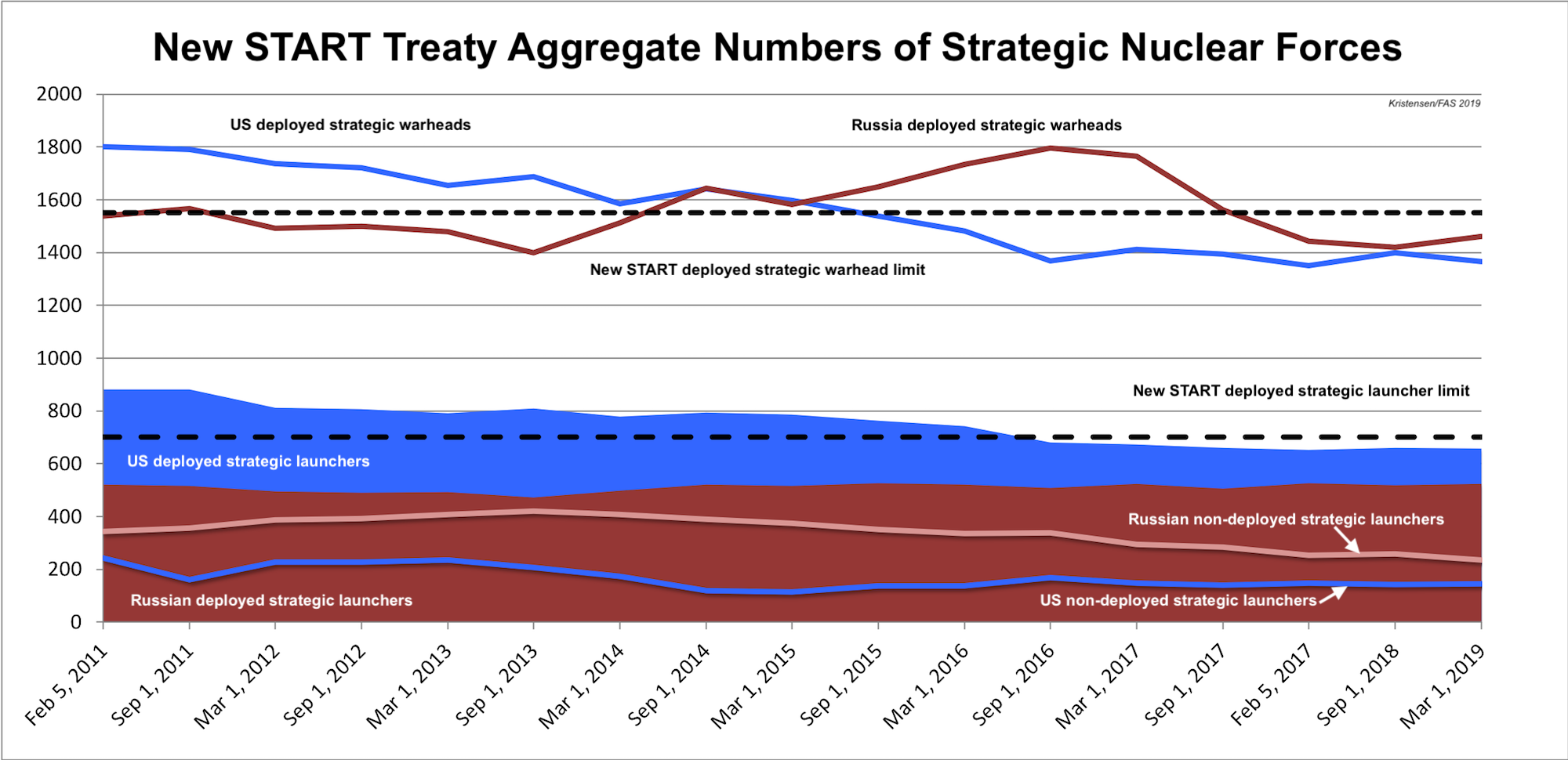

The latest New START data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,180 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,826 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 524 deployed strategic launchers with 1,461 warheads. That’s a slight increase of 7 launchers and 41 warheads compared with September 2018. Russia is currently 176 launchers and 89 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 656 strategic launchers with 1,365 warheads attributed to them, or a slight decrease of 3 launchers and 33 warheads compared with September 2018. The United States is currently 44 launchers and 185 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since September 2018 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,350 for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,850 and 6,460, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Build-Up, What Build-Up

Despite frequent claims by some about a Russian nuclear “buildup,” the New START data does not show such a development. On the contrary, it shows that Russia’s strategic offensive nuclear force level – despite ongoing modernization – is relatively steady. Deteriorating relations have so far not caused Russia (or the United States) to increase strategic force levels or slowed down the reductions required by New START. On the contrary, both sides seem to be continuing to structure their central strategic nuclear forces in accordance with the treaty’s limitations and intentions.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). An ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard is close to initial deployment but would likely supplement the current ICBM force rather than increasing it. The new weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces, nor does it appear to try to close the significant gap the New START data shows exists in the number of strategic launchers – 132 in US favor by the latest count. To put things in perspective, 132 launchers is nearly the equivalent of a US ICBM wing, more than six Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, or twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would be screaming about a disadvantage. Astoundingly, some are still trying to make that case despite the US advantage. Given the launcher asymmetry, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers by 185 since the peak of 421 in 2013.

Russian strategic modernization has been slower than expected with delays and less elaborate base upgrades and is stymied by a weak economy and corruption in government and defense industry. Russia is compensating for this asymmetry by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles, but the New START data indicates that Russia since 2016 has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,’ as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US can’t be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility and the US insists conversions have been carried out as required by the treaty rules that Russia agreed to. Discussions continue in Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 294 onsite inspections (3 each since September) and 17,516 notifications (up about 1,100 since September 2018). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

US SSBN in drydock. Russia says it cannot verify conversion of US strategic launchers. Click on image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: the treaty is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian claims that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

The idea that the INF debacle somehow requires a reevaluation of the value of New START is ridiculous. INF regulates regional land-based missiles whereas New START regulates the core strategic nuclear forces. Why would anyone in either country in their right mind jeopardize limits and verification of strategic forces that threaten the survival of the nation over a disagreement about regional forces that cannot? That seems to be the epidemy of irresponsible behavior.

And the disagreements about conversion of launchers and need to add new intercontinental forces to the treaty can and should be resolved within the BCC.

But it all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, well guess what, that’s what we’re going to get.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.