New START Data Released: Nuclear Flatlining

|

| Reductions under the New START Treaty have gotten off to a very slow start |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

More than a year and a half after the New START Treaty between the United States and Russia entered into force on January 5, 2011, one thing is clear: they are not in a hurry to reduce their nuclear forces.

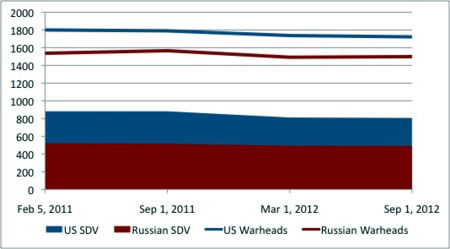

Earlier today the fourth batch of so-called aggregate data was released by the U.S. State Department. It shows that the United States and Russia since January 5, 2011, have reduced their accountable deployed strategic delivery vehicles by 76 and 30, respectively. Parts of those numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platforms entering or leaving maintenance. The U.S. number obscures the fact that it involves destruction of some of three dozen old B-52G bombers that still count as deployed even though they were retired two decades ago. The Russian number obscures replacement of older missiles with new ones on a less than one-for-one basis.

During the same period, the United States and Russia have reduced their number of accountable deployed strategic warheads by 78 and 38, respectively. Much of these numbers are fluctuations due to delivery platform maintenance and it is not clear that either country has made any explicit warhead reductions yet under the treaty. In any case, 38-78 warheads don’t amount to much out of the approximately 5,000 nuclear warheads the two countries retain in each of their respective nuclear stockpiles.

With 1,499 accountable warheads on 491 deployed strategic delivery vehicles, Russia is already well below the treaty limit and is only required to scrap 84 non-deployed delivery vehicles before the treaty enters into effect in six years on February 5, 2018.

The United States is well above the Russian force level, with 1,722 accountable warheads on 806 deployed strategic delivery vehicles. Over the next six years, it will have to remove 96 deployed delivery vehicles with 172 accountable warheads, and scrap 234 non-deployed platforms.

The U.S. posture appears even more bloated when considering that the Pentagon retains a large reserve of non-deployed warheads intended to increase the loading on the missiles in a crisis.

Russia does not have such an upload capacity. And even President Putin’s promised increased missile production over the next decade will not be able to offset the expected continued decline in the Russian triad that will result form the retirement of four old ICBM and SLBM systems over the next decade-plus.

This nuclear force structure asymmetry must be addressed in the next round of U.S.-Russian strategic nuclear talks. But even before such talks get underway, reductions can and should be made. There is simply no reason for the Pentagon to stretch reductions of excess nuclear forces through 2017. Forces slated for retirement should be removed from service now and the reserve of upload warheads should be trimmed. Doing so is good planning. Not only is it expensive (and stupid) to keep more nuclear forces than needed. But a bloated force structure provides unhelpful justification for those in the Russian establishment who argue for increasing missile production and deploying new missiles.

See previous analysis of New START data:

1. Second Batch of New START Data Released

2. US Releases Full New START Data

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.