The Flawed Push For New Nuclear Weapons Capabilities

By Hans M. Kristensen

Voices in the United States are once again calling for new and better nuclear weapons. The claim is that adversaries somehow would no longer be deterred by existing capabilities and that new or significantly modified weapons are needed to better match the adversaries and more efficiently destroy targets with lower yield to reduce radioactive fallout.

In December 2016, the US Defense Science Board – a semi-independent group that advises the Secretary of Defense – warned that “the nuclear threshold may be decreasing owing to the stated doctrines and weapons developments of some states.” Therefore, the DSB recommended DOD should “provide many more options in stemming proliferation or escalation; and a more flexible nuclear enterprise that could produce, if needed, a rapid, tailored nuclear option for limited use should existing non-nuclear or nuclear options prove insufficient.” This would involve “lower yield, primary only options” for strategic warheads on long-range ballistic missiles. (Emphasis added.)

Others have chimed in as well. In 2015, CSIS published Project Atom to define US nuclear strategic and posture. The report, that included contributions from several people that are now involved in the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, recommended that the United States should acquire “a suite of low-yield, special-effects warheads (low collateral, enhanced radiation, earth penetration, electromagnetic pulse, and others as technology advances), including possibly a smaller, shorter-range cruise missile that could be delivered by F-35s.” Several of the co-authors advocated a wide range of lower-yield and more flexible nuclear weapons – even beyond those already found in the arsenal. One of the co-authors is now the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy and Force Development.

Even James Miller, who was President Obama’s Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, and as such part of the decision to retire the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile (TLAM-N) in 2010, recently recommended (in an article co-authored with a board member from Raytheon that makes the Tomahawk) that the Trump administration’s NPR “should bring back the TLAM-N” to “provide NATO with a far more credible rung on an escalation ladder that currently is binary between conventional weapons and all-out nuclear war.”

Miller’s view was echoed by General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command, who recently told Congress that there is “a mismatch in escalatory options” in Europe because of Russia’s deployment of an illegal ground-launched cruise missile.

And most recently, John Harvey, former DOD official now helping out on the Trump administration’s NPR, advocated that the review should consider:

- Modifying an existing warhead to provide a low-yield option for strategic ballistic missiles (at least until a viable prompt global conventional strike capability is achieved);

- Respond to Russia’s INF violations by 1) acceleration of LRSO and/or 2) bring back the TLAM-N;

- Augment US nuclear declaratory policy to address Russia’s (and others) “escalate to win” strategy;

- Increase dual-capable aircraft (DCA) readiness in NATO (in consultation with Allies);

- Strengthen deterrence and assurance in the Asia-Pacific region (in consultation with Japan and South Korea) by 1) demonstrate the capability to deploy DCA to bases in South Korea and Japan, 2) equip aircraft carriers with nuclear capability (via the F-35C), and 3) bring back TLAM-N on attack submarines.

That sounds a lot like the debate in the early-1990s (even the Cold War) where nuclear laboratory officials started advocating for development of mini-nukes and micro-nukes for use in tailored regional scenarios. During the W. Bush administration there were also attempt to get new low-yield weapons. These efforts failed but now they’re back in full force because, the advocates say, of a more aggressive Russia and North Korea’s nuclear buildup.

Russia has, according to a new DIA report, “since at least 1993 (and most recently codified in the 2014 Military Doctrine)…reserved the right to a nuclear response to a non-nuclear attack that threatens the existence of the state.” That would imply escalation, presumably in an attempt to stop the attack and end hostilities on terms favorable to Russia. But now the nuclear advocates claim that Russia has a new “escalate to de-escalate” strategy that would consider using a few nuclear weapons early in a conflict – perhaps even before a full conflict had broken out.

One former senior defense official claimed in 2015 that “Moscow is using an entirely different definition of ‘escalating to deescalate’” than NATO used during the Cold War when threatening nuclear escalation if its conventional defenses were failing, by “employing the threat of selective and limited use of nuclear weapons to forestall opposition to potential aggression.” (Emphasis added.) Intelligence officials say privately that the idea of very early use is overblown and defense hawks are exploiting the “escalate to deescalate” debate to get what they want.

STRATCOM commander General John Hyten sees it in a different way: “I don’t think the Russian doctrine is escalate to deescalate. To me, the Russian doctrine is to escalate to win. So the purpose of their escalation is to win the conflict because they believe we won’t respond. Therefore, that decision that they would consider is not a tactical decision that is a strategic decision.”

The evidence that Russia believes the US would not respond to nuclear use is hard to find, as is evidence that this has anything to do with the yield or matching weapon types. But as officials involved in nuclear strategy often say, anyone can come up with a scenario that requires a new weapon. What’s missing from the debate is why the existing and planned capabilities are not sufficient. The United States already has flexible nuclear forces, advanced conventional capabilities, tailored war plans, and low-yield warheads in its arsenal.

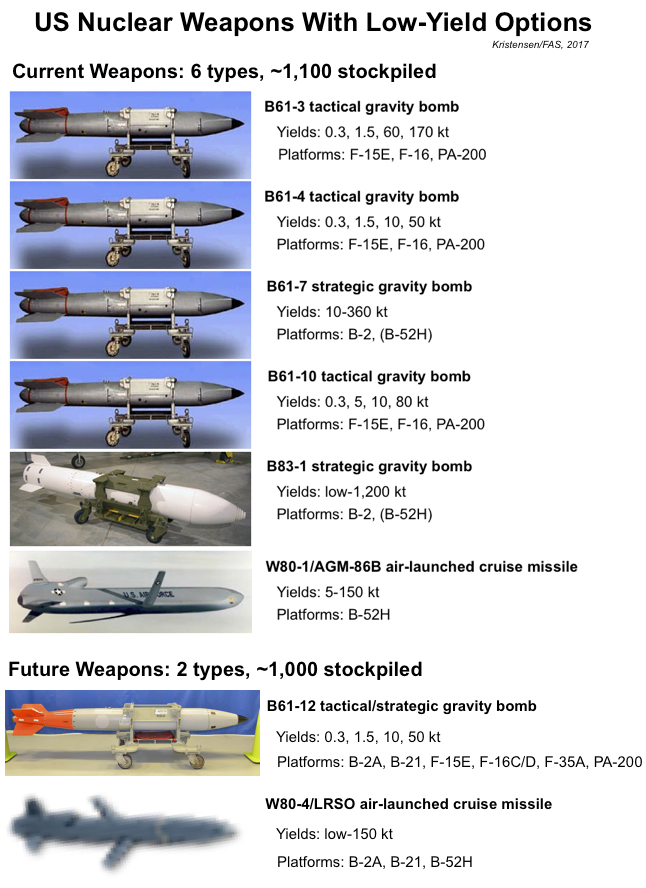

Current Capabilities

In fact, there are currently over 1,000 nuclear warheads in the US arsenal that have low-yield options. A yield is considered low if it’s 20 kilotons or less. Many high-yield weapons have selective low-yield options that can be chosen depending on the strike scenario; likewise, many low-yield weapons also have selective higher-yield options. After the planned modernization of the arsenal has been completed, there will still be about 1,000 warheads in the arsenal with low-yield options (see image below).

In response to a question from congressman John Geramendi (D-CA) about the DSB report recommending “expanding our nuclear options, including deploying low yield weapons on strategic delivery systems” and whether there is “a military requirement for these new weapons,” STRATCOM commander General John Hyten, said: “I can tell you that our force structure now actually has a number of capabilities that provide the president of the United States a variety of options to respond to any numbers of threats…” In another event General Hyten explained more about the current flexibility that is worth repeating:

“I’ll just say that the plans that we have right now, one of the things that surprised me most when I took command on November 3 was the flexible options that are in all the plans today. So we actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, which is the Attorney General, Secretary of State and everybody, I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the President on to give him options on what he would want to do.

So I’m very comfortable today with the flexibility of our response options. Whether the President of the United States and his team believes that that gives him enough flexibility is his call. So we’ll look at that in the Nuclear Posture Review. But I’ve said publicly in the past that our plans now are very flexible.

And the reason I was surprised when I got to STRATCOM about the flexibility, is because the last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing.” (Emphasis Added.)

Collateral Damage

So the current capabilities are sufficient to enable STRATCOM to build very flexible strike plans. Yet in its weapons life-extension and modernization plans, the military is nonetheless apparently pursuing additional lower-yield options. According to former STRATCOM commander General Robert Kehler, “we are trying to pursue weapons that actually are reducing in yield, because we are concerned about maintaining weapons that—that would have less collateral effect if the President ever had to use them…”

Collateral damage is a real issue for nuclear strike planners because they have to follow the guidelines for proportionality and discrimination in the Law of Armed Conflict. But whether that requires new or modified weapons is another issue. After all, the yields in the current arsenal have been with us for many years, so it’s unclear where the sudden need to change comes from. It sounds like the war planners are trying to get around some of the constraints imposed by the Law of Armed Conflict. If so, then the pursuit of lower-yield weapons would seem intended to make it easer to use nuclear weapons.

There is to my knowledge no evidence that the US Intelligence Community has concluded that US adversaries have decided to gamble that the US would be self-deterred from using nuclear weapons because they are too big or because the US doesn’t have more or better low-yield nuclear weapons.

Conclusions

General Hyden’s description of the flexibility of the current capabilities and the many options they provide to the president contradicts the EUCOM commander’s claim that there is “a mismatch in escalatory options” the claim by some that the United States needs to build new nuclear weapons, including low-yield nuclear weapons.

Advocates of additional nuclear capabilities seem too fixated on weapon types and don’t seem to understand or appreciate the flexibility of the current capabilities.

US nuclear planning long ago departed from the mindset that US nuclear capabilities necessarily have to match that of the adversaries. Even before the Cold War ended, the US navy began to unilaterally retire all its short-range nuclear weapons. After the Cold War ended the Army was completely denuclearized. Today the United States only retains about 300 non-strategic nuclear bombs, mainly for symbolic reasons to reassure its allies.

This near-elimination of non-strategic nuclear weapons was done despite US knowledge that Russia retained a large inventory of non-strategic nuclear weapons and despite growing concerns about regional nuclear adversaries. Those arsenals have continued to evolve without it leading to military requirements to bring back the ASROC, SUBROC, Lance, TLAM-N, or ground-launched cruise missiles.

Yes there are serious challenges in Russia and North Korea, but those challenges can be address with the considerable capabilities in the current nuclear arsenal.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.