Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

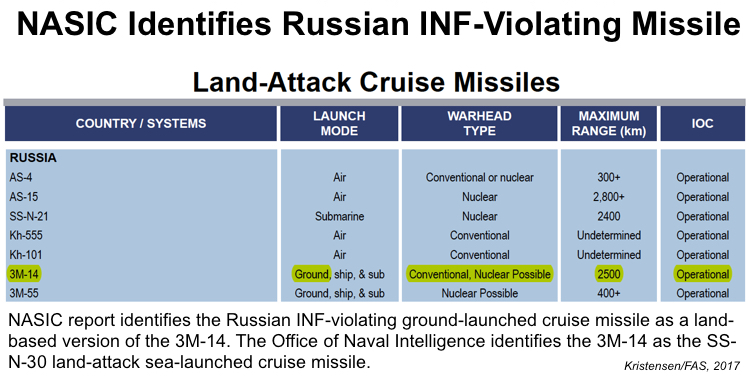

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

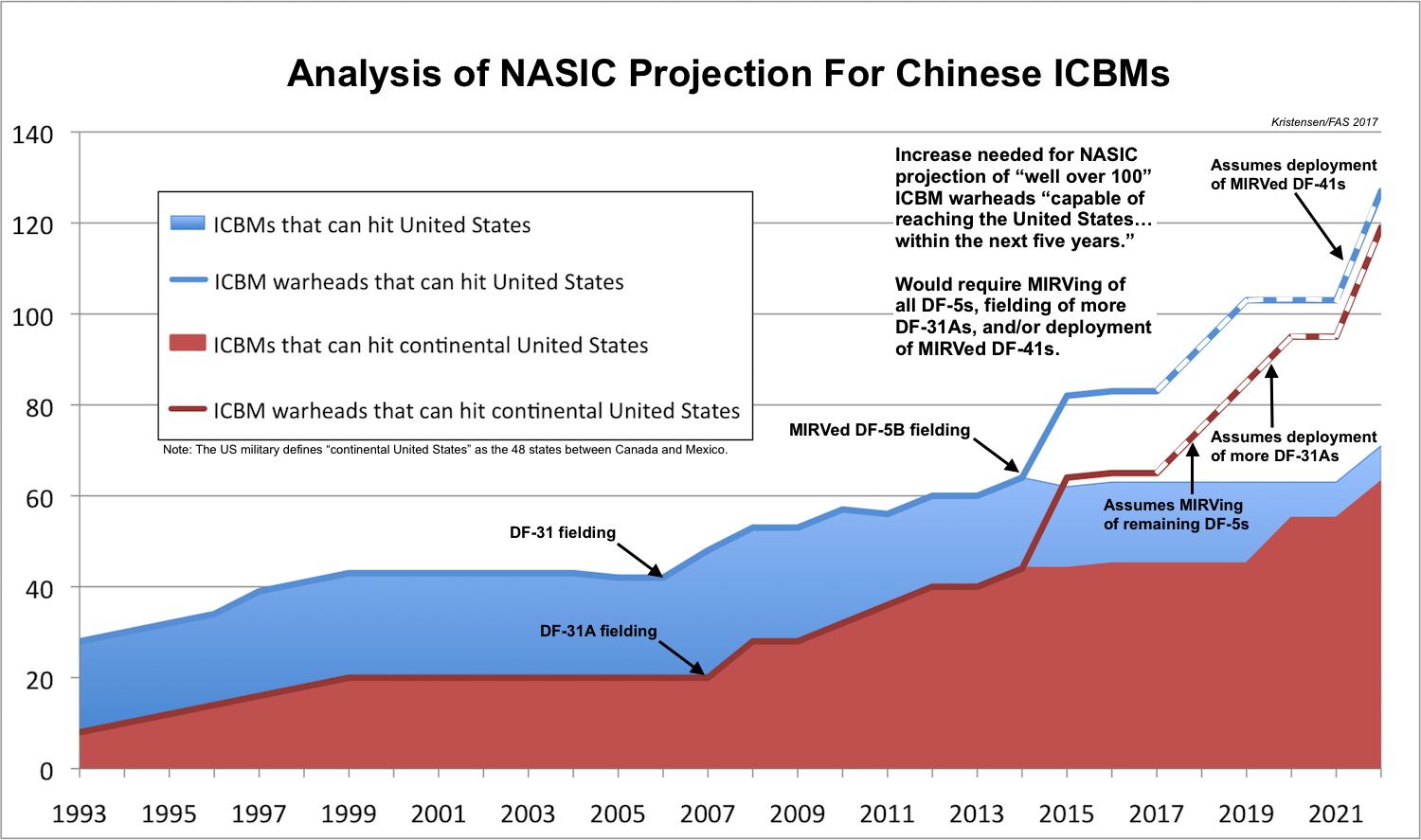

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Yet the description of the DF-31A program sounds like deployment is still in progress: “The longer range CSS-10 Mod 2 will allow targeting of most of the continental United States” (emphasis added).

For the first time, the report includes a graphic illustration of the DF-31 and DF-31A side by side, which shows the longer-range DF-31A to be little shorter but with a less pointy nosecone and a wider third stage (see image).

The long-awaited (and somewhat mysterious) DF-41 ICBM is still not deployed. NASIC says the DF-41 is “possibly capable of carrying MIRV,” a less certain determination than the 2017 DOD report, which called the missile “MIRV capable.” The report lists the DF-41 with three stages and a Post-Boost Vehicle, details not provided in the previous report.

One of the two nuclear versions of the DF-21 MRBM appears to have been retired. NASIC only lists one: CSS-5 Mod 2. In total, the report lists “fewer than 50” launchers for the nuclear version of the DF-21, which is the same number it listed in the 2013 report (see here for description of one of the DF-21 launch units. But that was also the number listed back then for the older nuclear DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1). The nuclear MRBM force has probably not been cut in half over the past four years, so perhaps the previous estimate of fewer than 50 launchers was intended to include both versions. The NASIC report does not mention the CSS-5 Mod 6 that was mentioned in the DOD’s annual report from 2016.

Sea-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report lists a total of 48 JL-2 SLBM launchers, corresponding to the number of launch tubes on the four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. That does not necessarily mean, however, that the missiles are therefore fully operational or deployed on the submarines under normal circumstances. They might, but it is yet unclear how China operates its SSBN fleet (for a description of the SSBN fleet, see here).

The 2017 report no longer lists the Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN or the JL-1 SLBM, indicating that China’s first (and not very successful) sea-based nuclear capability has been retired from service.

Cruise Missiles: The new report removes the “conventional or nuclear” designation from the DH-10 (CJ-10) ground-launched land-attack cruise missile. The possible nuclear option for the DH-10 was listed in the previous three NASIC reports (2006, 2009, and 2013). The DH-10 brigades are organized under the PLA Rocket Force that operates both nuclear and conventional missiles.

A US Air Force Global Strike Command document in 2013 listed another cruise missile, the air-launched DH-20 (CJ-20), with a nuclear option. NASIC has never attributed nuclear capability to that weapon and the Office of the Secretary of Defense stated recently that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.”

At the same time, the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently told Congress that China was upgrading is cruise missiles further, including “with two, new air-launched ballistic [cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Pakistan

The NASIC report surprisingly does not list Pakistan’s Babur GLCM as operational.

The NASIC report states that “Pakistan continues to improve the readiness and capabilities of its Army Strategic Force Command and individual strategic missile groups through training exercises that include live missile firings.” While all nuclear-armed states do that, the implication probably is that Pakistan is increasing the reaction time of its nuclear missiles, particularly the short-range weapons.

The report states that the Shaheen-2 MRBM has been test-launched “seven times since 2004.” While that fits the public record, NASIC doesn’t mention that the Shaheen-2 for some reason has not been test launched since 2014, which potentially could indicate technical problems.

The Abdali SRBM now has a range of 200 km (up from 180 km in the 2013 report). It is now designated as close-range ballistic missile instead of a short-range ballistic missile.

NASIC describes the Ababeel MRBM, which was first test-launch in January 2017, as as “MIRVed” missile. Although this echoes the announcement made by the Pakistani military at the time, the designation “the MIRVed Abadeel” sounds very confident given the limited flight history and the technological challenges associated with developing reliable MIRV systems.

Neither the Ra’ad ALCM nor the Babur GLCM is listed as deployed, which is surprising especially for the Babur after 13 flight tests. Babur launchers have been fitting out at the National Development Complex for years and are visible at some army garrisons. Nor does NASIC mention the Babur-2 or Babur-3 (naval version) versions that have been test-flown and announced by the Pakistani military.

India

It is a surprise that the NASIC report only lists “fewer than 10” Agni-2 MRBM launchers. This is the same number as in 2013, which indicates there is still only one operational missile group equipped with the Agni-2 seven years after the Indian government first declared it deployed. The slow introduction might indicate technical problems, or that India is instead focused on fielding the longer-range Agni-3 IRBM that NASIC says is now deployed with “fewer than 10” launchers.

Neither the Agni-4 nor Agni-5 IRBMs are listed as deployed, even though the Indian government says the Agni-4 has been “inducted” into the armed forces and has reported three army “user trial” test launches. NASIC says India is developing the Agni-6 ICBM with a range of 6,000 km (3,728 miles).

For India’s emerging SSBN fleet, the NASIC report lists the short-range K-15 SLBM as deployed, which is a surprise given that the Arihant SSBN is not yet considered fully operational. The submarine has been undergoing sea-trials for several years and was rumored to have conducted its first submerged K-15 test launch in November 2016. But a few more are probably needed before the missile can be considered operational. The K-4 SLBM is in development and NASIC sets the range at 3,500 km (2,175 miles).

As for cruise missiles, it is helpful that the report continue to list the Bramos as conventional, which might help discredit rumors about nuclear capability.

North Korea

Finally, of the nuclear-armed states, NASIC provides interesting information about North Korea’s missile programs. None of the North Korean ICBMs are listed as deployed.

The report states there are now “fewer than 50” launchers for the Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM. NASIC sets the range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles) instead of the 4,000 km (2,485 miles) sometimes seen in the public debate.

Likewise, while many public sources set the range of the mobile ICBMs (KN-08 and KN-14) as 8,000 km (4,970 miles) – some even longer, sufficient to reach parts of the United States, the NASIC report lists a more modest range estimate of 5,500+ km (3,418 miles), the lower end of the ICBM range.

Additional Information:

- Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2017 [Note: A corrected NASIC report was published in June 2017.]

- Previous versions of this NASIC report: 2006, 2009, 2013

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.