Leveraging Department of Energy Authorities and Assets to Strengthen the U.S. Clean Energy Manufacturing Base

Summary

The Biden-Harris Administration has made revitalization of U.S. manufacturing a key pillar of its economic and climate strategies. On the campaign trail, President Biden pledged to do away with “invent it here, make it there,” alluding to the long-standing trend of outsourcing manufacturing capacity for critical technologies — ranging from semiconductors to solar panels —that emerged from U.S. government labs and funding. As China and other countries make major bets on the clean energy industries of the future, it has become clear that climate action and U.S. manufacturing competitiveness are deeply intertwined and require a coordinated strategy.

Additional legislative action, such as proposals in the Build Back Better Act that passed the House in 2021, will be necessary to fully execute a comprehensive manufacturing agenda that includes clean energy and industrial products, like low-carbon cement and steel. However, the Department of Energy (DOE) can leverage existing authorities and assets to make substantial progress today to strengthen the clean energy manufacturing base.

This memo recommends two sets of DOE actions to secure domestic manufacturing of clean technologies:

- Foundational steps to successfully implement the new Determination of Exceptional Circumstances (DEC) issued in 2021 under the Bayh-Dole Act to promote domestic manufacturing of clean energy technologies.

- Complementary U.S.-based manufacturing investments to maximize the DEC’s impact and to maximize the overall domestic benefits of DOE’s clean energy innovation programs.

Challenge and Opportunity

Recent years have been marked by growing societal inequality, a pandemic, and climate change-driven extreme weather. These factors have exposed the weaknesses of essential supply chains and our nation’s legacy energy system.

Meanwhile, once a reliable source of supply chain security and economic mobility, U.S. manufacturing is at a crossroads. Since the early 2000s, U.S. manufacturing productivity has stagnated and five million jobs have been lost. While countries like Germany and South Korea have been doubling down on industrial innovation — in ways that have yielded a strong manufacturing job recovery since the Great Recession — the United States has only recently begun to recognize domestic manufacturing as a crucial part of a holistic innovation ecosystem. Our nation’s longstanding, myopic focus on basic technological research and development (R&D) has contributed to the American share of global manufacturing declining by 10 percentage points, and left U.S. manufacturers unprepared to scale up new innovations and compete in critical sectors long-term.

The Biden-Harris administration has sought to reverse these trends with a new industrial strategy for the 21st century, one that includes a focus on the industries that will enable us to tackle our most pressing global challenge and opportunity: climate change. This strategy recognizes that the United States has yet to foster a robust manufacturing base for many of the key products —ranging from solar modules to lithium-ion batteries to low-carbon steel — that will dominate a clean energy economy, despite having funded a large share of the early and applied research into underlying technologies. The strategy also recognizes that as clean energy technologies become increasingly foreign-produced, risks increase for U.S. climate action, national security, and our ability to capture the economic benefits of the clean energy transition.

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has a central role to play in executing the administration’s strategy. The Obama administration dramatically ramped up funding for DOE’s Advanced Manufacturing Office (AMO) and launched the Manufacturing USA network, which now includes seven DOE-sponsored institutes that focus on cross-cutting research priorities in collaboration with manufacturers. In 2021, DOE issued a Determination of Exceptional Circumstances (DEC) under the Bayh-Dole Act of 19801 to ensure that federally funded technologies reach the market and deliver benefits to American taxpayers through substantial domestic manufacturing. The DEC cites global competition and supply chain security issues around clean energy manufacturing as justification for raising manufacturing requirements from typical Bayh-Dole “U.S. Preference” rules to stronger “U.S. Competitiveness” rules across DOE’s entire science and energy portfolio (i.e., programs overseen by the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4)). This change requires DOE-funded subject inventions to be substantially manufactured in the United States for all global use and sales (not just U.S. sales) and expands applicability of the manufacturing requirement to the patent recipient as well as to all assignees and licensees. Notably, the DEC does allow recipients or licensees to apply for waivers or modifications if they can demonstrate that it is too challenging to develop a U.S. supply chain for a particular product or technology.

The DEC is designed to maximize return on investment for taxpayer-funded innovation: the same goal that drives all technology transfer and commercialization efforts. However, to successfully strengthen U.S. manufacturing, create quality jobs, and promote global competitiveness and national security, DOE will need to pilot new evaluation processes and data reporting frameworks to better assess downstream impacts of the 2021 DEC and similar policies, and to ensure they are implemented in a manner that strengthens manufacturing without slowing technology transfer. It is essential that DOE develop an evidence base to assess a common critique of the DEC: that it reduces appetite for companies and investors to engage in funding agreements. Continuous evaluation can enable DOE to understand how well-founded these concerns are.

Yet, the new DEC rules and requirements alone cannot overcome the structural barriers to domestic commercialization that clean energy companies face today. DOE will also need to systematically build domestic manufacturing efforts into basic and applied R&D, demonstration projects, and cross-cutting initiatives. DOE should also pursue complementary investments to ensure that licensees of federally funded clean energy technologies are able and eager to manufacture in the United States. Under existing authorities, such efforts can include:

- Elevating and empowering AMO and Manufacturing USA to build a competitive U.S. workforce and regional infrastructure for clean energy technologies.

- Directly investing in domestic manufacturing capacity through DOE’s Loan Programs Office and through new authorities granted under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

- Market creation through targeted clean energy procurement.

- Coordination with place-based and justice strategies.

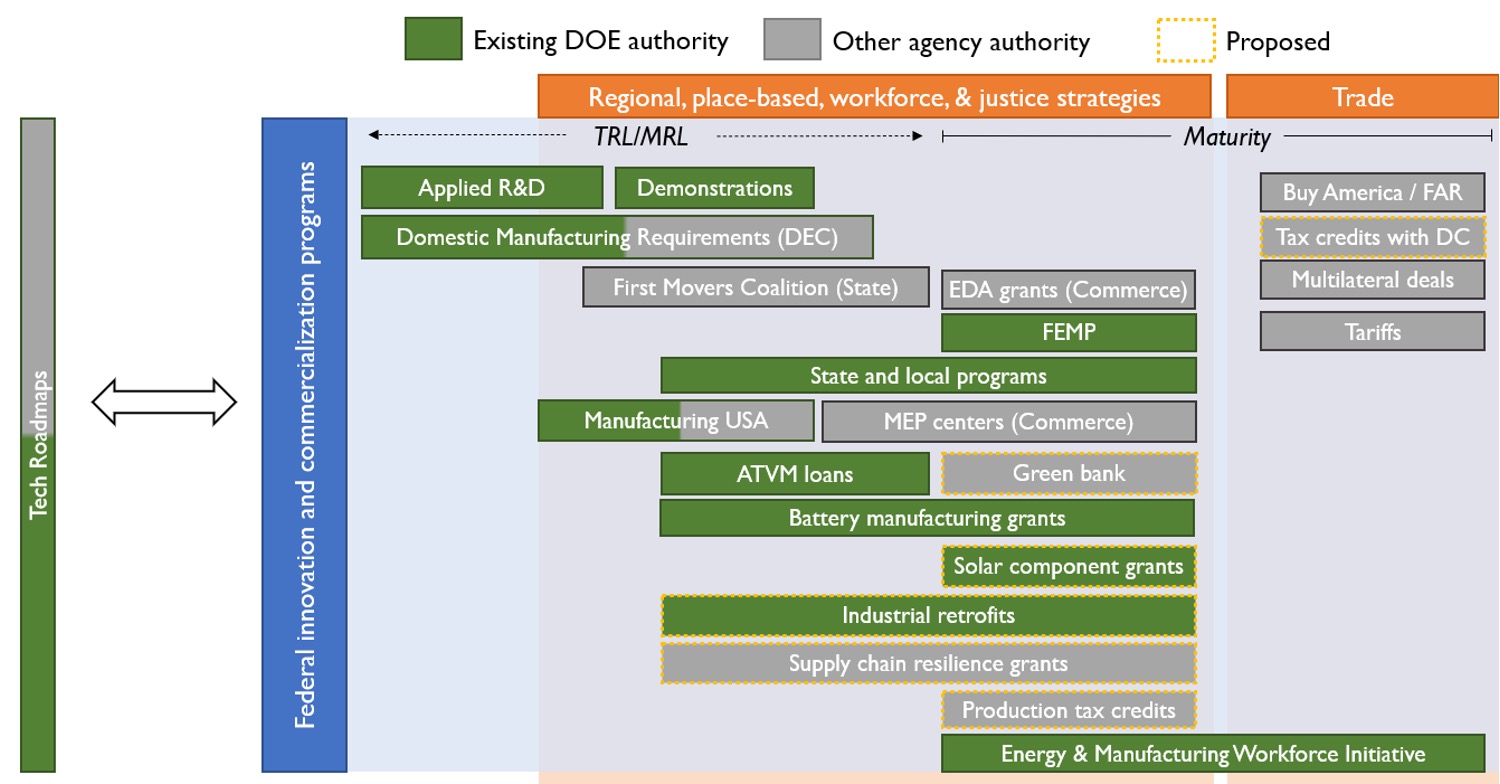

These complementary efforts will enable DOE to generate more productive outcomes from its 2021 DEC, reduce the need for waivers, and strengthen the U.S. clean manufacturing base. In other words, rather than just slow the flow of innovation overseas without presenting an alternative, they provide a domestic outlet for that flow. Figure 1 provides an illustration of the federal ecosystem of programs, DOE and otherwise, that complement the mission of the DEC.

Programs are arranged in rough accordance to their role in the innovation cycle. TRL and MRL refer to technology and manufacturing readiness level, respectively. Proposed programs, highlighted with a dotted yellow border, are either found in the Build Back Better Act passed by the House in 2021 or the Bipartisan Innovation Bill (USICA/America COMPETES)

Figure 1Programs are arranged in rough accordance to their role in the innovation cycle. TRL and MRL refer to technology and manufacturing readiness level, respectively. Proposed programs, highlighted with a dotted yellow border, are either found in the Build Back Better Act passed by the House in 2021 or the Bipartisan Innovation Bill (USICA/America COMPETES).

Plan of Action

While further Congressional action will be necessary to fully execute a long-term national clean manufacturing strategy and ramp up domestic capacity in critical sectors, DOE can meaningfully advance such a strategy now through both long-standing authorities and recently authorized programs. The following plan of action consists of (1) foundational steps to successfully implement the DEC, and (2) complementary efforts to ensure that licensees of federally funded clean energy technologies are able and eager to manufacture in the United States. In tandem, these recommendations can maximize impact and benefits of the DEC for American companies, workers, and citizens.

Part 1: DEC Implementation

The following action items, many of which are already underway, are focused on basic DEC implementation.

- Develop and socialize a draft reporting and data collection framework. The Office of the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation should work closely with DOE’s General Counsel and individual program offices to develop a reporting and data collection framework for the DEC. Key metrics for the framework should be informed by the Science and Innovation (S4) mission, and capture broader societal benefits (e.g., job creation). DOE should target completion of a draft framework by the end of 2022, with plans to socialize, pilot, and finalize the framework in consultation with the S4 programs and key external stakeholders.

- Identify pilots for the new data reporting framework in up to five Science and Innovation programs. Since the DEC issuance, Science and Innovation (S4) funding opportunity announcements (FOAs) have been required to include a section on “U.S. Manufacturing Commitments” that states the requirements of the U.S. Competitiveness Provision. FOAs also include a section on “Subject Invention Utilization Reporting,” though the reporting listed is subject to program discretion. By early 2023, DOE should identify up to five program offices in which to pilot the data reporting framework referenced above. The Office of the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4) should also consider coordinating with the Office of the Under Secretary for Infrastructure (S3) to pilot the framework in the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations. Pilot programs should build in opportunities for external feedback and continuous evaluation to ensure that the reporting framework is adequately capturing the effects of the DEC.

- Set up a DEC implementation task force. The DEC requires quarterly reporting from program offices to the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation. The Under Secretary’s office should convene a task force — comprising representatives from the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT), the General Counsel’s office (GC), the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains, and each of DOE’s major R&D programs — to track these reports. The task force should meet at least quarterly, and its findings should be transmitted to the DOE GC to monitor DEC implementation, troubleshoot compliance issues, and identify challenges for funding recipients and other stakeholders. From an administrative standpoint, these activities could be conducted under the Technology Transfer Policy Board.

- Incorporate domestic manufacturing objectives into all technology-specific roadmaps and initiatives, including the Earthshots. DOE and the National Labs regularly track the development and future potential of key clean energy technologies through analysis (e.g., the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)’s Future Studies). DOE also has developed high-profile cross-cutting initiatives, such as the Grid Modernization Initiative and the “Earthshots” initiative series, aimed at achieving bold technology targets. OTT, in concert with the Office of Policy and individual program offices, should incorporate domestic manufacturing into all technology-specific roadmaps and cross-cutting initiatives. Specifically, technology-specific roadmaps and initiatives should (i) assess the current state of U.S. manufacturing for that technology, and (ii) identify key steps needed to promote robust U.S. manufacturing capabilities for that technology. ARPA-E (which has traditionally included manufacturing in its technology targets and been subject to a DEC since 2013)and the supply chain recommendations in the Energy Storage Grand Challenge Roadmap may provide helpful models.

- Support the White House and NIST on the iEdison rebuild. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is currently revamping the iEdison tool for reporting federally funded inventions. The coincident timing of this effort with the DOE’s DEC creates an opportunity to align data and waiver processes across government. DOE should work closely with NIST to understand new features being developed in the iEdison rebuild, offer input on manufacturing data collection, and align DOE reporting requirements where appropriate. Data reported through iEdison will help DOE evaluate the success of the DEC and identify areas in need of support. For instance, if iEdison data shows that a certain component for batteries becomes an increasing source of DEC waivers, DOE and the Department of Commerce may respond with targeted actions to remedy this gap in the domestic battery supply chain. Under the pending Bipartisan Innovation Bill, the Department of Commerce could receive funding for a new supply-chain monitoring program to support these efforts, as well as $45 billion in grants and loans to finance supply chain resilience. iEdison data could also be used to justify Congressional approval of new DOE authorities to strengthen domestic manufacturing.

Part 2: Complementary Investments

Investments to support the domestic manufacturing sector and regional innovation infrastructure must be pursued in tandem with the DEC to translate into enhanced clean manufacturing competitiveness. The following actions are intended to reduce the need for waivers, shore up supply chains, and expand opportunities for domestic manufacturing:

- Elevate and empower DOE’s AMO to serve as the hub of U.S. clean manufacturing strategy. Under the Obama administration, recognition that the U.S. was underinvesting in manufacturing innovation led to a dramatic expansion of the Advanced Manufacturing Office (AMO) and the launch of the Manufacturing USA institutes, modeled on Germany’s Fraunhofer institutes. DOE has begun to add a seventh institute focused on industrial decarbonization to the six institutes it already manages, and requested funding to launch an eighth and ninth institute in FY22. While both AMO and Manufacturing USA have proven successful through an array of industry-university-government partnerships, technical assistance, and cooperative R&D, neither are fully empowered to serve as hubs for U.S. clean manufacturing strategy. AMO currently faces bifurcated demands to implement advanced manufacturing practices (cross-sector) and promote competitiveness in emerging clean industries (sector-specific). The Manufacturing USA institutes have also been limited by their narrow, often siloed mandates and the expectation of financial independence after five years; under the Trump Administration, DOE sought to wind down the institutes rather than pursue additional funding. DOE should reinvest in establishing AMO and the institutes as the “tip of the spear” for a domestic clean manufacturing strategy and seek to empower them in four ways:

- Institutional structure. AMO should be elevated to the Deputy Under Secretary or Assistant Secretary level, as has been recommended by recent DOE Chief of Staff Tarak Shah in a 2019 report, the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, the National Academies, and many others. This combination of enhanced funding and authority would empower DOE to pursue a more holistic clean manufacturing strategy, commensurate with the scale of the climate and industrial challenges we face.

- Mission focus. It is critical that AMO continue to work on both advanced manufacturing practices (cross-sector) and competitiveness in emerging clean energy industries (sector-specific), but this bifurcated mission does present challenges. As alluded to in a January 2022 RFI, AMO is attempting to pursue both goals in tandem. With the structural elevation proposed above, there is an opportunity for AMO’s clean energy manufacturing mission to be clarified, with a subset of staff and programs specifically dedicated to competitiveness in these emerging sectors.

- Regional infrastructure and workforce development. AMO’s authority already extends beyond applied R&D, providing technical assistance, workforce development, and more. The Manufacturing USA institutes provide regional support for early prototyping efforts, officially operating up to Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 7. However, these programs should be granted greater authority and budget to foster regional demonstration and workforce development centers for low-carbon and critical clean energy manufacturing technologies. These activities create the infrastructure for constant learning that is necessary to entice manufacturers to remain in the U.S. and reduce the need for waivers, even when foreign manufacturers present cost advantages. To start, DOE should establish a regional demonstration and workforce development facility operated by the new clean manufacturing institute for industrial decarbonization (similar in nature to Oak Ridge’s Manufacturing Demonstration Facility (MDF)) to accelerate domestic technology transfer of clean manufacturing practices, and consider additional demonstration and workforce development facilities at future institutes.

- Scale. Despite accounting for roughly one-third of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and 11% of GDP, manufacturing receives less than 10% of DOE energy innovation funding. Additionally, the Manufacturing USA institutes have roughly one-fourth of the budget, one-fifth of the institutes, and one-hundredth of the employees of the Fraunhofer institutes in Germany, a much smaller country that has nevertheless managed to outpace the United States in manufacturing output. To align with climate targets and the administration’s goal to quadruple innovation budgets, DOE manufacturing RD&D would need to grow to roughly $2 billion by 2025.

- Deploy at least $20 billion in grants, loans, and loan guarantees to support solar, wind, battery, and electric vehicle manufacturing and recycling by 2027. Not only is financial support to expand domestic clean manufacturing capacity critical for energy security, innovation clusters, and economic development, but it can also alleviate the barriers for innovators to manufacture in the U.S. and reduce the need for DEC waivers. Existing DOE authorities include the $7 billion for battery manufacturing provided in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and $17 billion in existing direct loan authority at the Loan Programs Office’s Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing unit. DOE’s technology roadmaps can help these programs to be coordinated with earlier stage RD&D efforts by anticipating emerging manufacturing needs, so that S4 funding recipients who are subject to U.S. manufacturing requirements have more confidence in their ability to find ample domestic manufacturing capacity. The same entities that receive R&D funds also should be eligible for follow-on manufacturing incentives. The pending Bipartisan Innovation Bill and Build Back Better Act may also provide $3 billion for solar manufacturing, renewal of the 48C advanced manufacturing investment tax credit, and a new advanced manufacturing production tax credit. While these funding mechanisms have already been identified in response to the battery supply chain review, they should be applied beyond the battery sector.

- Leverage DOE procurement authority and state block grant programs to drive demand for American-made clean energy. Procurement is a key demand-pull lever in any coordinated industrial strategy, and can reinforce the DEC by assuring potential applicants that American-made clean energy products will be rewarded in government purchasing. This administration’s Executive Order (EO) on federal sustainability calls for 100% carbon-free electricity by 2030 and “net-zero emissions from overall federal operations by 2050, including a 65 percent emissions reduction by 2030.” The Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP), noted in the EO and the federal government’s accompanying sustainability plan as one of the hubs of clean-energy procurement expertise, will play a key role in providing technical support and progress measurement for all government agencies as they pursue these goals, including by helping agencies to identify U.S. suppliers. For instance, in response to the battery supply chain review, FEMP was tasked with conducting a diagnostic on stationary battery storage at federal sites. DOE also delivers substantial funding and technical assistance to help states and localities deploy clean energy through the Weatherization Assistance Program and State Energy Program. These programs are now consolidated under a new Under Secretary for Infrastructure. DOE should build on these efforts by leveraging DOE’s multi-billion dollar state block grant and competitive financial assistance programs, including the recently-authorized State Manufacturing Leadership grants, to support states and communities in planning to strengthen local and regional manufacturing capacity to make progress on sustainability targets (see Updating the State Energy Program to Promote Regional Manufacturing and Economic Revitalization).

- Align the above activities with DOE’s place-based strategies for advancing environmental justice and supporting fossil fuel-centered communities in their clean energy transition. Throughout U.S. history, manufacturing has fostered rich local cultures and strong regional economies. Domestic manufacturing of clean energy technologies and clean industrial materials represents a major opportunity for economic revitalization, job growth, and pollution reduction. DOE also has a major role in executing President Biden’s environmental justice agenda, including as chair of the Interagency Working Group (IWG) on Coal and Power Plant Communities. As noted in the IWG’s initial report, investments in manufacturing have the potential to provide pollution relief to frontline communities and also retain the U.S. industrial workforce from high-carbon industries. Indeed, this is one reason why NIST’s Manufacturing Extension Partnerships played a significant role in the POWER Initiative under the Obama administration. The domestic clean energy manufacturing investments detailed above — including expansion of AMO, new grant programs, and procurement —should all be executed in close coordination with DOE’s place-based strategies to deliver benefits for environmental justice and legacy energy communities and to foster regional cultures of innovation. Finally, DOE should coordinate with other regional development efforts across government, such as the EDA’s Build Back Better Regional Challenge and USDA’s Rural Development programs.

How DOE can emerge from political upheaval achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.