Getting Federal Hiring Right from the Start

Validating the Need and Planning for Success in the Federal Hiring Process

Most federal agencies consider the start of the hiring process to be the development of the job posting. However, the federal hiring process really begins well before the job is posted and the official clock starts. There are many decisions that need to be made before an agency can begin hiring. These decisions have a number of dependencies and require collaboration and alignment between leadership, program leaders, budget professionals, hiring managers, and human resource (HR) staff. What happens in these early steps can not only determine the speed of the hiring process, but the decisions made also can cause the hiring process to be either a success or failure.

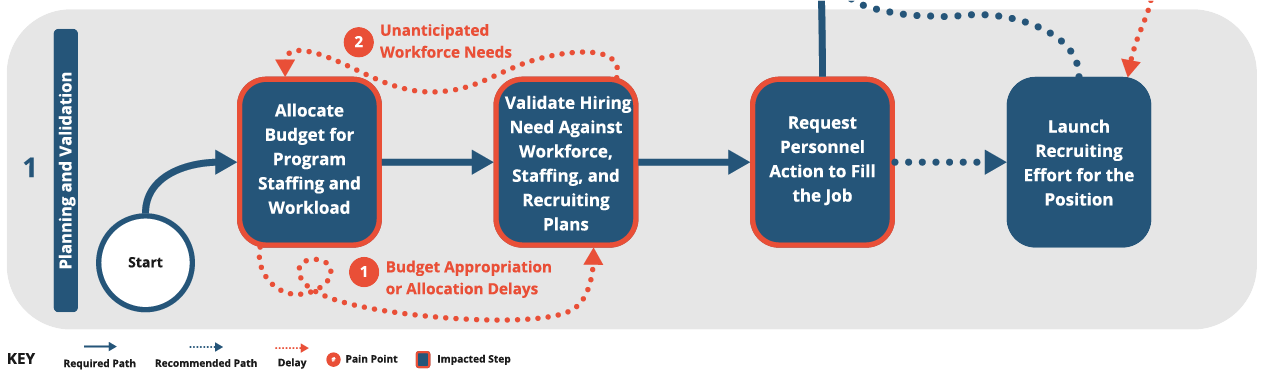

In our previous blog post, we outlined the steps in the federal hiring process and identified bottlenecks impacting the staffing of roles to support permitting activities (e.g., environmental reviews). This post dives into the first phase of the process: planning and validation of the hiring need. This phase includes four steps:

- Allocate Budget for Program Staffing and Workload

- Validate Hiring Need Against Workforce, Staffing, and Recruiting Plans

- Request Personnel Action to Fill the Job

- Launch Recruiting Efforts for the Position

Clear communication and quality collaboration between key actors shape the outcomes of the hiring process. Finance staff allocate the resources and manage the budget. HR workforce planners and staffing specialists identify the types of positions needed across the agency. Program owners and hiring managers define the roles needed to achieve their mission and goals. These stakeholders must work together throughout this phase of the process.

Even with collaboration, challenges can arise. For example, there may be:

- A lack of clarity in the budget appropriation and transmission regarding how the funds can be used for staffing versus other program actions;

- Emergent hiring needs from new legislation or program changes that do not align with agency workforce plans, meaning the HR recruiting and hiring functions are not prepared to support these new positions; and

- Pressure from Congressional appropriators and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to speed up hiring and advance implementation, which is particularly acute with specific programs named in legislation;

- New tools outside of the boundaries of individual staffing (e.g., shared certificates of eligibles) that need to be considered and integrated into this phase.

Adding to these challenges, the stakeholders engaging in this early phase bring preconceptions based on their past experience. If this phase has previously been delayed, confusing, or difficult, these negative expectations may present a barrier to building effective collaboration within the group.

Breaking Down the Steps

For each step in the Planning and Validation phase, we provide a description, explain what can go wrong, share what can go right, and provide some examples from our research, where applicable. This work is based on extensive interviews with hiring managers, program leaders, staffing specialists, workforce planners and budget professionals as well as on-the-job experience.

Step I. Allocate Budget for Program Staffing and Workload

In this first step, the agency receives budget authorization or program direction funding through OMB derived from new authorizing legislation, annual appropriations, or a continuing resolution. Once the funds are available from the Treasury Department, agency budget professionals allocate the resources to the particular programs inside the agency. They provide instructions regarding how the money is to be used (e.g., staffing, contracting, and other actions to support program execution). For example, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) provided funding for grants to build cell towers and connections for expanding internet access to underserved communities. This included a percentage of funds for administration and program staffing.

In an ideal world, program leaders could select the best mix of investments in staffing, contracting, equipment, and services to implement their programs efficiently and effectively. They work toward this in budget requests, but in the real world, some of these decisions are constrained by the specifics of the authorizing legislation, OMB’s interpretation, and the agency’s language in the program direction.

What Can Go Wrong

- Prescriptive program direction funding can limit the options of program managers and HR leaders to craft the workforce for the future. In some cases, the legislation even identifies types of people to hire or the hiring authority to be used (e.g., Excepted Service, Competitive Service, Direct Hire Authority, etc.). This limits the program leaders’ options to build or buy the resource solutions that will work best for them.

- Legislation can be ambiguous regarding how programs can use the funding for staffing. This delays implementation because it requires deliberation by OMB, the agency budget function, program leaders, and even the agency attorneys to determine what is permissible with the funding. This can also increase risk aversion as agency leaders have grown concerned with trespassing on the Anti-Deficiency Act, which prohibits federal agencies from obligating or expending federal funds in advance or in excess of an appropriation, and from accepting voluntary services. For example, with the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding, one agency we spoke with decided to only authorize term hires because of the time-limited nature of the funding, despite having attrition data that predicted permanent positions would become available in the coming years. This can limit recruiting to only those willing to take temporary positions and reduce the ability to fill permanent, competitive roles.

- Delays between the passing of legislation, Treasury Department authorization, and OMB budget direction can create impatience and frustration by Congressional appropriators and agency leaders who want to fill jobs and implement intended programs. This pressures program leaders and HR specialists to make faster, sometimes suboptimal, decisions about who to hire and the timeline. They tend to proceed with the positions they already have, instead of making data-based decisions to match future workload with their hiring targets. In one case, a permitting hiring manager under this kind of pressure wanted to hire an Environmental Protection Specialist, but did not have a current PD or recruiting strategy. They opted for a management analyst position for which they already had a PD because they could hire for this position faster.

What Can Go Right

- Budget/Legislative Integration: Agency Chief Financial Officers (CFOs), program leaders and Legislative Affairs consult with each other to anticipate the impacts of new legislation and changes to budget language that alter resource management and staffing decisions. For example, one agency we spoke with anticipated the increased demand for HR services resulting from the yet-to-be passed BIL, and thus used existing open positions to hire the HR staff needed to recruit and hire the hundreds of new staff to support the legislation.

- Clear Guidance: Establishing clear budget guidance as early as possible and anticipating upcoming changes helps program and HR leaders plan for and implement optimal program resources. This frequently requires collaboration and consultation with all the parties involved in resource decisions, especially when new legislative mandates are ambiguous or provide no direction on resource use. In one of our discussions with a science agency, we learned that the agency engaged in collaborative negotiations across its programs to allocate the resources from the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) in the absence of clear legislative direction.

Step II. Validate Hiring Need Against Workforce, Staffing, and Recruiting Plans

After receiving their budget allocation, program leaders validate their hiring need by matching budget resources with workload needs. A robust workforce plan becomes useful, as it allows leaders to identify gaps in the current workforce, workload, and recruiting plans and future workload requirements. Workforce plans that align with budget requests and anticipate future needs enable HR specialists and hiring managers to quickly validate the hiring need and move to request the personnel action.

What Can Go Wrong

- Frequently, workforce plans do not address emergent needs coming from new legislation or abrupt program changes. This is often due to rapid technology changes in the job (e.g., use of geographical information systems or data analysis tools), dynamism in the external environment, or unfunded mandates. This means program leaders and hiring managers need to quickly adapt their workload estimates and workforce configurations to match these new needs.

- Ambiguity in the legislative intent for staffing can extend into this step. This creates a delay as the program leads work to build consensus on the positions needed, the hiring authorities to be used, and the timeline for bringing new candidates onboard.

- If program leaders have been constrained in backfilling open positions (due to previous budget issues) these immediate needs limit their options to configure a workforce for the future. When coupled with competition across the agency for resources and a lack of workforce planning data, program leaders often sacrifice longer term, sustainable workforce needs for short-term solutions.

What Can Go Right

- Readiness: A mature process in which workforce planners, legislative analysts, and program leaders are anticipating and addressing changes in legislation and their external environment reduces surprises and enables HR staff and program managers to adapt when new staffing or changes are required. In one interview, a program leader described using empirical data on key workload indicators to develop workload projections and determine the positions needed for implementing their program requirements.

- Strike Teams: When legislation or outside changes result in a hiring surge, successful agencies form strike teams with sponsorship from senior leaders. These strike teams pull staff from across the agency – leaders, program leaders, HR leaders and implementers – to focus on meeting the demands of the hiring surge. In response to the infrastructure laws, affected agencies were able to accelerate hiring and target key positions with these teams. Many agencies are doing this to address the AI talent surge right now.

- Integration with Strategy Development: The best workforce planning emerges when key actors are embedded into the agency’s strategy; each strategic goal has a workforce component. Using scenario planning, simulation, and other foresight tools agencies can develop adaptive, predictive workforce plans that model the workforce of the future and focus on the skills needed across the agency to sustain and thrive in achieving its mission. When the future changes, the agency is ready to pivot. OPM’s Workforce of the Future Playbook moves in this direction.

Step III. Request Personnel Action to Fill the Job and Launch Recruiting Efforts for the Position

Note: Requesting personnel action to fill the job is a relatively straightforward step, so we have combined it with launching the recruiting process for simplification.

In most agencies, the hiring manager or program leader fills out an SF-52 form to request the hiring action for a specific position. This includes defining the position title, occupation, grade level, type of position, agency, location, pay plan, and other pertinent information. To do this, they verify that the funding is available and they have the budget authority to proceed.

Though recruiting can begin before and after this step, this is the chance to begin recruiting in earnest. This can involve activating agency HR staff, engaging contract recruiting resources if they are available, preparing and launching agency social media announcements, and notifying recruitment networks (e.g., universities, professional organizations, alumni groups, stakeholders, communities of practice, etc.) of the job opening.

What Can Go Wrong

- If a hiring manager intimates that a potential candidate has an “inside track” on a position or promises that a candidate will be hired. These trespass on Merit Systems Principles and Prohibited Personnel Practices can result in financial damage to the agency and censure for the hiring manager.

- When an agency lacks recruiting resources and network connections, especially for highly specialized roles or a talent surge, this hinders agencies from reaching the right communities to attract strong applicants and restricts the applicant pool.

- Segmented recruiting to just HR and its resources results in a lack of expectation that the hiring manager plays a key role in recruiting and actively promotes the job to their networks.

- At any point in the process, funding can be pulled and the personnel action will need to be canceled. This disheartens the hiring manager and HR staff, who are ready to start the hiring process.

What Can Go Right

- Build The Pipeline: Hiring managers and recruiters who build and maintain pipelines of potential applicants for key positions have a ready base to begin outreach. This is permissible as long as there is no expectation that those on this list will receive any preferential treatment, as stated above. For example, in our discussion with one land-management agency, we learned that they keep in touch with potential candidates by sharing periodic updates on their programs and job opportunities. This continues to engage a pool of candidates and provides access to an interested community when launching a new position.

- Build Enthusiasm For The Job Across The Ecosystem: Rallying peers, fellow alumni, agency leaders, universities, contractor contacts, and others across HR and program networks to build enthusiasm for the open position and joining the agency. One sub-agency office we met promotes its positions on a variety of public sites (i.e., LinkedIn, Instagram, Facebook, and their website).

- Direct and Sustained Attention to Recruiting: Agencies that set clear expectations for hiring manager engagement in recruiting fare better at attracting qualified candidates because the hiring manager can directly speak to the job opportunity.

- Tell the Story: Hiring managers and recruiters that tell a compelling story of the agency and the importance of this job to the mission help potential applicants see themselves in the role and their potential impact, which increases the likelihood that they will apply.

Conclusion

Following What Can Go Right practices in this beginning phase can reduce the risk of challenges emerging later on in the hiring process. Delays in decision making around budget allocation and program staffing, lingering ambiguity in the positions needed for programs, and delayed recruiting activities can lead to difficulties in accessing the candidate pools needed for the roles. This ultimately increases the risk of failure and may require a restart of the hiring process.

The best practices outlined here (e.g., anticipating budget decisions, adapting workforce plans, and expanding recruiting) set the stage for a successful hiring process. They require collaboration between HR leaders, recruiters and staffing specialists, budget and program professionals, workforce planners, and hiring managers to make sure they are taking action to increase the odds of hiring a successful employee.

The actions that OPM, the Chief Human Capital Officers Council (CHCO), their agencies, and others are taking as a result of the recent Hiring Experience Memo support many of the practices highlighted in What Can Go Right for each step of the process. Civil servants should pay attention to OPM’s upcoming webinars, guidance, and other events that aim to support you in implementing these practices.

As noted in our first blog on the hiring process for permitting talent, close engagement between key actors is critical to making the right decisions about workforce configuration and workload management. Starting right in this first phase increases the chances of success throughout the hiring process.

How hard can it be to hire into the federal government? Unfortunately, for many, it can be very challenging.

Policy entrepreneurs have a unique opportunity to shape the agenda for the next administration. Knowing when and how to act is crucial to turning policy ideas into action.