Geolocating China’s Unprecedented Missile Launch: The Potential What, Where, How, and Why

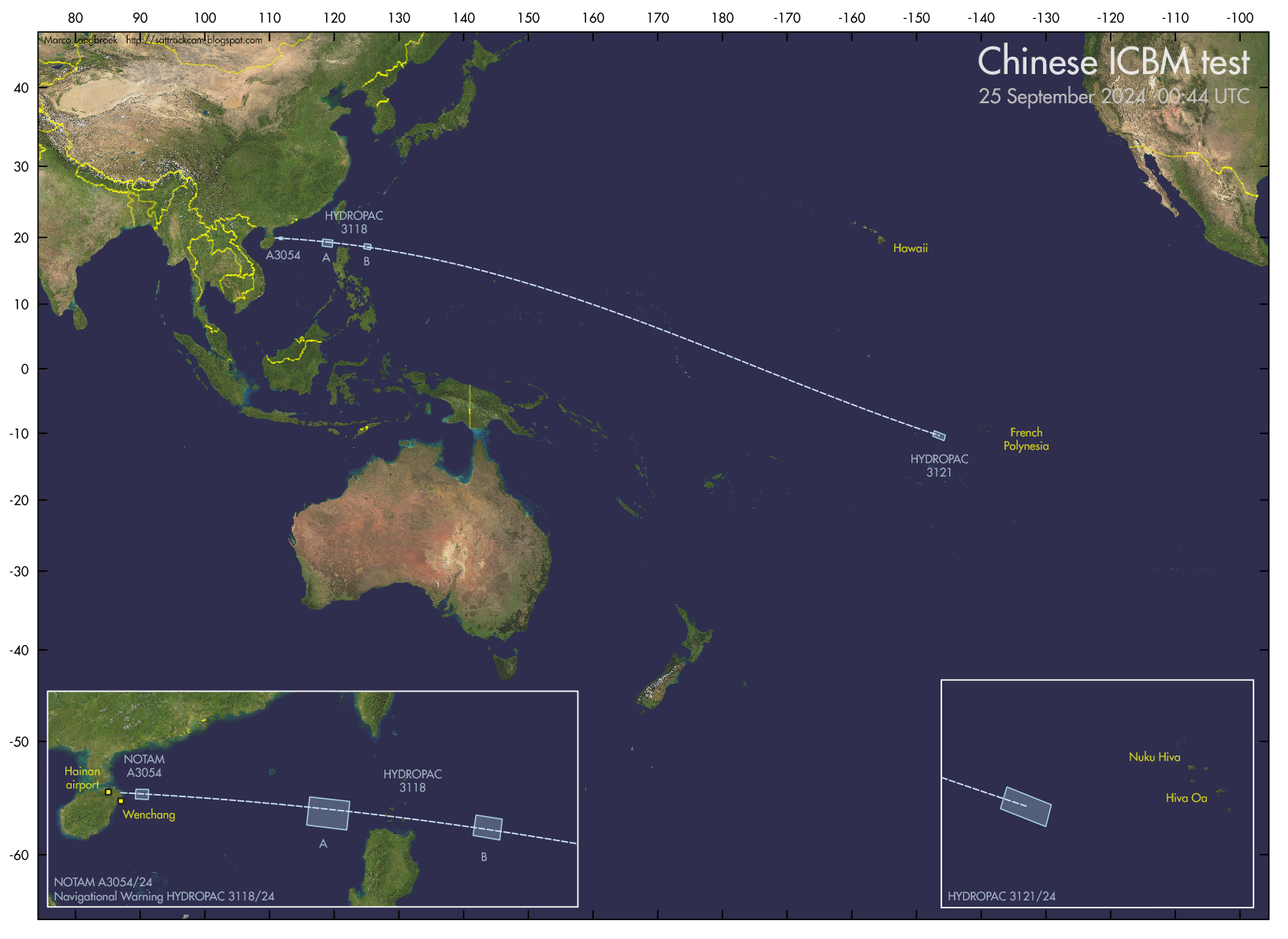

On September 25, 2024, the Chinese Ministry of National Defence announced that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) had test-launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) into the South Pacific. The announcement stated that this was a “routine arrangement in [their] annual training plan.” However, the ICBM was launched from Hainan Island, an unusual location for this kind of missile. In addition, the reentry vehicle impacted in the South Pacific, an estimated 11,700 km away, marking the first time China had targeted the Pacific in a test since 1980 when it tested its first ICBM (the DF-5) at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center.

This map, created by Dr. Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek on X), shows hazard areas from Navigational Warnings and a NOTAM with the reconstructed ballistic flight path. (source)

Given the unusual nature of this test launch and the lack of official information about the status of China’s nuclear forces, this event is an opportunity to further examine China’s nuclear posture and activities, including the type of missile, how it fits into China’s nuclear modernization, and where it was launched from.

What missile is it?

When news of the launch broke, navigational warnings and trajectory calculations indicated the missile was launched from northeast Hainan Island, a Chinese province in the South China Sea. This is not where China normally test-launches its ICBMs, and there is no ICBM brigade permanently deployed on the island. The location and the range of the missile indicated that it was a road-mobile missile launcher, either a DF-41 or DF-31A/AG type. In the days after the launch, several images surfaced with clues about the type of missile and its potential launch location.

An image of the missile lauch released by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army on September 25, 2024.

The first image, released by news outlets on September 25, showed features that made it clear that this was, in fact, a DF-31AG missile. The DF-31AG is a modernized version of China’s first solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM, the DF-31, which debuted in 2006. Since 2007, China has been supplementing and now completely replaced the initial DF-31 versions with the longer-range DF-31A. The DF-31A launcher had limited maneuverability, so in 2017, China first displayed the enhanced DF-31AG launcher. The DF-31AG will likely completely replace the DF-31A in the next few years.

The DF-31AG launcher is thought to carry the same missile as the DF-31A, but the 21-meter-long eight-axle HTF5980 transporter erector launcher has improved maneuverability and is thought to require less support. The single erector arm seen in the above image matches other images of the DF-31AG. The image seems to show that the launcher was partially covered by some sort of camouflage during the launch.

The DF-31AG uses a cold-launch method, meaning the missile is ejected from the canister using compressed gas or steam before the first-stage engine ignites. Unfortunately, this also means it is harder to geolocate the site of the launch because there are unlikely to be burn marks that would normally remain visible on the ground after hot-launching a missile.

How did the missile get there?

The nearest deployment of DF-31AG missiles is with the 632 Brigade located in Shaoyang in mainland China, around 800 km away. There is no confirmation that the missile came from this particular brigade, but the distance gives some perspective as to the process and amount of time it takes to bring a DF-31AG to Hainan Island.

To transport the mobile ICBM to Hainan, it was likely placed onto a railcar and brought to a port such as Yuehai Railway Beigang Wharf before being loaded onto a ship and transferred to Haikou port or a similar location at Hainan Island. From there, the missile was likely driven, along with the accompanying support vehicles, to a sheltered and protected area near the final launch location.

It remains unknown whether the missile was launched directly from the launch position itself, remotely from a local command post, or remotely from a centralized authority.

Where was the missile launched from?

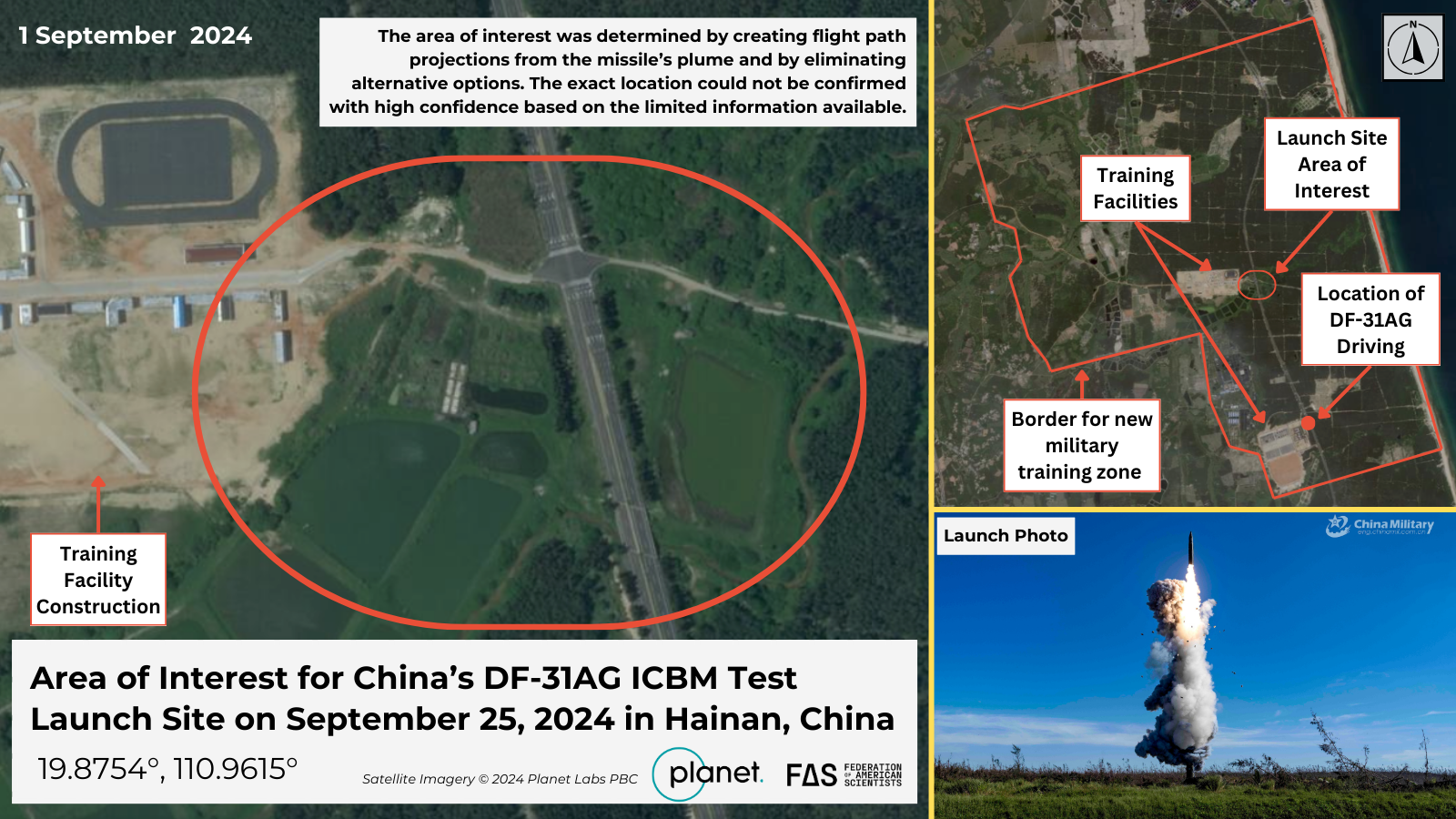

To find the precise location where the DF-31AG was launched on the island, we had to rely on the few photos and videos available to us (mostly captured by locals). To do this, we collaborated with analyst Ise Midori (@isekaimint on X), who carried out a complex analysis of the various launch videos to pinpoint the approximate launch location.

In the above image of the launch, one of the first noticeable features is the devastated vegetation, which matches what we would expect to see after typhoon Yagi impacted northeast Hainan in early September. There is also a small body of water barely visible at the bottom right of the image, which provides a clue when searching for the launch location.

After analyzing the available images, photos, and videos, Midori determined the general area where the launch likely occurred to be in Wenchang, Hainan. While we are unable to determine the exact location with high confidence due to a lack of clearly identifiable signatures, we expect it to be within the area of interest indicated below, potentially at the highway intersection.

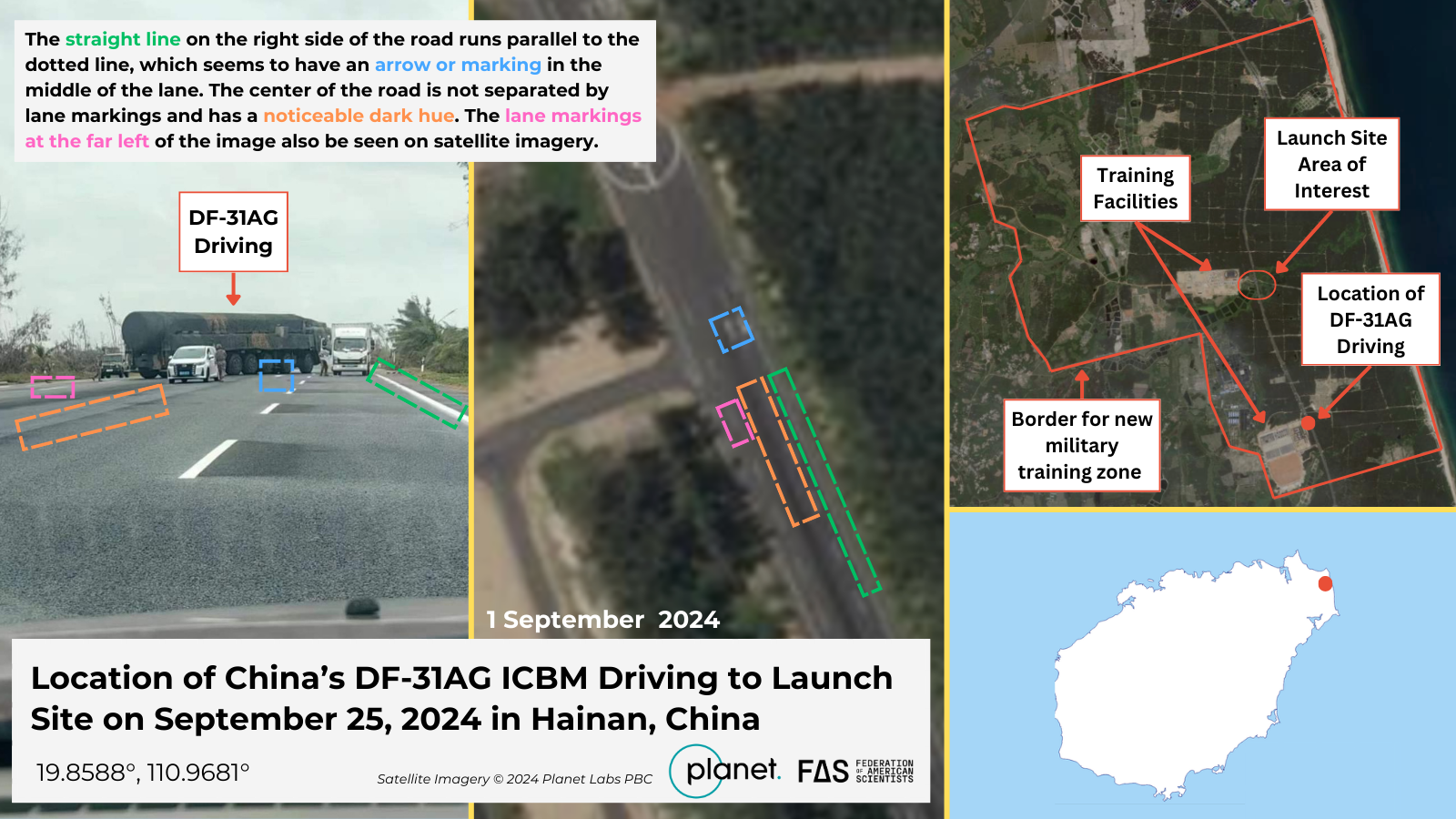

Meanwhile, the image below began circulating on social media shortly after the launch. The image reportedly captures the DF-31AG as it was driving to its launch position, although the cloud coverage does not match that from the photo of the launch and could have been taken hours beforehand.

An image of the DF-31AG missile driving on Hainan Island that circulated on social media shortly after the launch.

After observing the road markings and vegetation in the image, satellite imagery from Planet Labs PBC revealed a unique road that matched these signatures. This road is also only 1.9 km away from the launch location area of interest, increasing confidence that the launch occurred at or near this area.

Notably, both the launch area of interest and the location of the DF-31AG on the road are within the boundaries of what seems to be a new military training zone constructed in recent years. This also helps increase confidence in the launch area of interest and highlights this area as important for future observation.

Why here, and why now?

While China has not test-launched an ICBM into the Pacific in over four decades (it normally test launches the missiles in a very high apogee within its borders), it is not unusual for China – or other countries for that matter – to test-launch their nuclear-capable systems. It is interesting, however, to consider why China may have chosen to launch from Hainan Island instead of somewhere that is operationally representative or perhaps easier to travel to on the mainland coast. Nevertheless, the location allows China to fly the missile at full range without dropping missile stages on the ground or overflying other countries. It is unknown whether China will test-launch more ICBMs from Hainan Island in the future.

These types of tests also take months of extensive planning and coordination. Thus, the launch was likely motivated by broader political factors, not in response to particular recent events. Tong Zhao, Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, points out that this test was crucial for the PLARF to reestablish its internal and external credibility following corruption scandals and unprecedented leadership shifts. Additionally, reports of issues with the quality of certain missiles likely prompted a desire to reestablish recognition of operational competence.

Further, because the PLARF conducted the test launch as part of a “military drill” rather than a technological development program, it likely aims to convey military prowess and combat readiness. Conducting an ICBM test over the ocean also likely reflects China’s ambition to solidify its international status as a major nuclear power since the United States also regularly tests its ICBMs over the open ocean.

Notably, the Pentagon confirmed they received advanced notice of China’s test launch, which potentially sets a precedent for pre-launch notification and could leave room for further communication on risk reduction measures. Moving forward, it will be interesting to see if China begins to routinely conduct these kinds of tests beyond its borders and if it continues to provide pre-launch notification to relevant states. The new DF-41 has yet to be test-flown at full range in a realistic trajectory.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.