Get Ready, Get Set, FESI!: Putting Pilot-Stage Clean Energy Technologies on a Commercialization Fast Track

It may sound dramatic, but “Valleys of Death” are delaying the United States’ technology development progress needed to achieve the energy security and innovation goals of this decade. As emerging clean energy technologies move along the innovation pipeline from first concept to commercialization, they encounter hurdles that can prove to be a death knell for young startups. These “Valleys of Death” are gaps in funding and support that the Department of Energy (DOE) hasn’t quite figured out how to fill – especially for projects that require less than $25 million.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, almost 35% of CO2 emissions to avoid require technologies that are not yet past the demonstration stage. It’s important to note that this share is even higher in harder-to-decarbonize sectors like long-haul transportation and heavy industry. To reach this metric, a massive effort within the next ten years is needed for these technologies to reach readiness for deployment in a timely manner.

Although programs exist within DOE to address different barriers to innovation, they are largely constrained to specific types of technologies and limited in the type of support they can provide. This has led to a discontinuous support system with gaps that leave technologies stranded as they wait in the “valleys of death” limbo. A “Fast Track” program at DOE – supported by the CHIPS and Science-authorized Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) – would remove obstacles for rapidly-growing startups that are hindered by traditional government processes. FESI is uniquely positioned to be a valuable tool for DOE and its allies as they seek to fill the gaps in the technology innovation pipeline.

Where does FAS come in?

The Department of Energy follows the lead of other agencies that have established agency-affiliated foundations to help achieve their missions, like the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) and the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR). These models have proven successful at facilitating easier collaboration between agencies and philanthropy, industry, and communities while guarding against conflicts of interest that might arise from such collaboration. Notably, in 2020, the FNIH coordinated a public-private working group, ACTIV, between eight U.S. government agencies and 20 companies and nonprofits to speed up the development of the most promising COVID-19 vaccines.

As part of our efforts to support DOE in standing up its new foundation with the Friends of FESI Initiative, FAS is identifying potential use cases for FESI – structured projects that the foundation could take on as it begins work. The projects must forward DOE’s mission in some way, with a particular focus on accelerating clean energy technology commercialization.

In early April, we convened leaders from DOE, philanthropy, industry, finance, the startup community, and fellow NGOs to workshop a few of the existing ideas for how to implement a Fast Track program at DOE. We kicked things off with some remarks from DOE leaders and then split off into four breakout groups for three discussion sessions.

In these sessions, participants brainstormed potential challenges, refinements, likely supporters, and specific opportunities that each idea could support. Each discussion was focused around what FESI’s unique value-add was for each concept and how best FESI and DOE could complement each other’s work to operationalize the idea. The four main ideas are explored in more detail below.

Support Pilot-scale Technologies on the Path to Commercialization

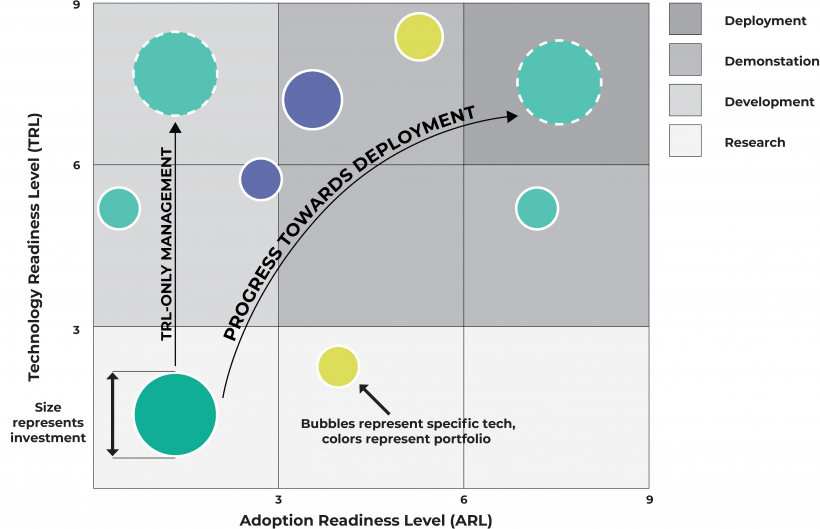

The technology readiness level (TRL) framework has been used to determine an emerging technology’s maturity since NASA first started using it in the 1970s. The TRL scale begins at “1” when a technology is in the basic research phase and ends at “9” when the technology has proven itself in an operating environment and is deemed ready for full commercial deployment.

However, getting to TRL 9 alone is insufficient for a technology to actually get to demonstration and deployment. For an emerging clean technology to be successfully commercialized, it must be completely de-risked for adoption and have an established economic ecosystem that is prepped to welcome it. To better assess true readiness for commercial adoption, the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) at the Department of Energy (DOE) uses a joint “TRL/Adoption Readiness Level (ARL)” framework. As depicted by the adoption readiness level scale below, a technology’s path to demonstration and deployment is less linear in reality than the TRL scale alone suggests.

Source: The Office of Technology Transitions at the Department of Energy

There remains a significant gap in federal support for technologies trying to progress through the mid-stages of the TRL/ARL scales. Projects that fall within this gap require additional testing and validation of their prototype, and private investment is often inaccessible until questions are answered about the market relevance and competitiveness of the technology.

FESI could contribute to a pilot-scale demonstration program to help small- and medium-scale technologies move from mid-TRLs to high-TRLs and low to medium ARLs by making flexible funding available to innovators that DOE cannot provide within its own authorities and programs. Because of its unique relationship as a public-private convener, FESI could reach the technologies that are not mature enough, or don’t qualify, for DOE support, and those that are not quite to the point where there is interest from private investors. It could use its convening ability to help identify and incubate these projects. As it becomes more capable over time, FESI might also play a role in project management, following the lead of the Foundation for the NIH.

Leverage the National Labs for Tech Maturation

The National Laboratories have long worked to facilitate collaboration with private industry to apply Lab expertise and translate scientific developments to commercial application. However, there remains a need to improve the speed and effectiveness of collaboration with the private sector.

A Laboratory-directed Technology Maturation (LDTM) program, first ideated by the EFI Foundation, would enable the National Labs to allocate funding for technology maturation projects. This program would be modeled after the highly successful DOE Office of Science Laboratory-directed Research and Development (LDRD) program and it would focus on taking ideas at the earliest Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) and translating them to proof of concept—from TRL 1 and 2 to TRL 3. This program would translate scientific discoveries coming out of the Labs into technology applications that have great potential for demonstration and deployment. FESI could assist in increasing the effectiveness of this effort by lowering the transaction costs of working with the private sector. It could also be a clearinghouse for LDTM-funded scientists who need partners for their projects to be successful, or could support an Entrepreneur-in-Residence or entrepreneurial postdoc program that could house such partners.

While FESI would be a practical convener of non-federal funding for this program, the magnitude of the funding needed to establish this program may not be well-suited for an initial project for the foundation to take on. It is estimated that each project would be in the ballpark of $5-20 million, and funding a full portfolio, which private sponsors are more likely to be interested in, is a nine-figure venture. Supporting a LDTM program is a promising idea for further down the line as FESI grows and matures.

Align Later-stage R&D Market Needs with Corporate Interest via a Commercialization Consortium

Industry and investors often struggle to connect with government-sponsored technologies that fit their plans and priorities. At the same time, government-sponsored researchers often struggle to navigate the path to commercialization for new technologies.

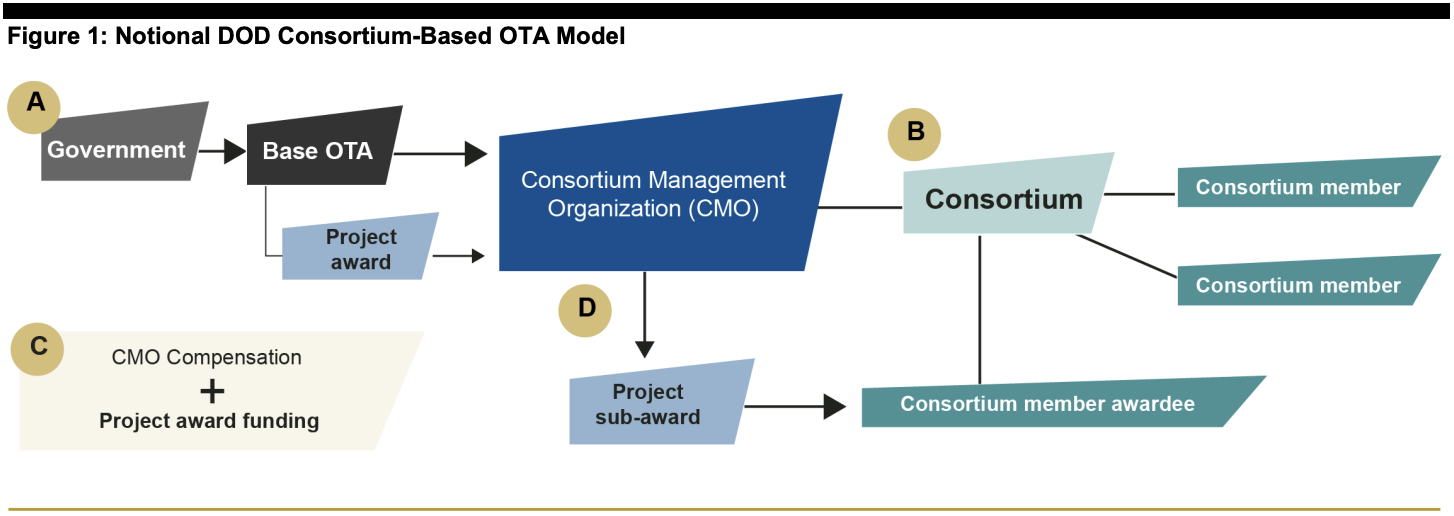

Based on a model widely-used by the Department of Defense (DOD), an open consortium is a mechanism and means to convene industry and highlight relevant opportunities coming out of DOE-funded work. The model creates an accessible and flexible pathway to get U.S.-funded inventions to commercial outcomes.

FESI could function as the Consortium Management Organization (CMO), pictured below, to help structure interactions and facilitate communications between DOE sponsors and award recipients while freeing government staff from “picking winners.” As the CMO, FESI would issue task orders and handle contracting per the consortium agreement, which would be organized under DOE’s other transactions authority (OTA). In this model, FESI could work with DOE staff in applied R&D offices and OCED to identify opportunities and needs in the development pipeline, and in parallel work with consortium members (including holders of DOE subject inventions, industry partners, and investors) to build teams and scope projects to advance targeted technology development efforts.

This consortium could help work out the kinks in the pipeline to ensure that successful technologies in the applied offices have sufficient “runway” to reach TRL 7, and that OCED has a healthy pipeline of candidate technologies for scaled demonstrations. FESI could mitigate the offtake risk that is known to stall first-of-a-kind projects, like financing a lithium extraction project, for example. Partners in industry and the investment community will be aligned, and potentially provide cost share, in order to gain access to technologies emerging from DOE subject inventions.

The Time is Right

This workshop comes at a prime time for FESI. The Secretary of Energy appointed the inaugural FESI board—composed of 13 leaders in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors—in mid-May. In the coming months, the board will formally set up the organization, hire staff, adopt an agenda, and begin to pursue projects that will make a real impact to advance DOE’s mission. As Friends of FESI, we want to see the foundation position itself for the grand impact it is designed to have.

The above proposals are actionable and affordable projects that a young FESI is uniquely-positioned to achieve. That said, supporting pilot-stage demonstrations is only one area where FESI can make an impact. If you have additional ideas for how FESI could leverage its unique flexibility to accelerate the clean energy transition, please reach out to our team at fesifriends@fas.org. You can also keep up with the Friends of FESI Initiative by signing up for our email newsletter. Email us!

As ‘Friends of FESI’ we want to see this new foundation set up from day one to successfully fulfill the promise of its large impact.

“FAS enthusiastically celebrates this FESI milestone because, as one of the country’s oldest science and technology-focused public interest organizations, we recognize the scale of the energy transition challenge and the urgency to broker new collaborations and models to move new energy technology from lab to market,” says Dan Correa, CEO of FAS.