Building Momentum for Equity in Medical Devices

Just over a year ago, I found myself pausing during a research lab meeting. “Why were all the subjects in our studies of wearable devices white? And what were the consequences of exclusion?”

This question stuck with me long after the meeting. Digging into the evidence, I was alarmed to find paper after paper signaling embedded biases in key medical technologies.

One device stuck out amongst the rest – the pulse oximeter. Because of its crucial role in diagnosing COVID-19, it had caught the attention of a diverse group of stakeholders: clinicians looking to understand the impacts on patient care, engineers working to build more equitable devices, social scientists tracing the history of device and examining colorism in pulse oximetry, policymakers seeking solutions for their constituents, and the FDA, which was examining racial bias in medical technologies for the first time. But what I found as I scoped out this policy area is that these stakeholders weren’t talking to one another, at the expense of coordinated progress towards equity in pulse oximetry.

With all eyes directed towards the FDA’s Advisory Committee meeting on November 1st, 2022, FAS convened a half-day session of stakeholders on November 2nd to chart a research and policy agenda for near-term mitigation of inequities in pulse oximetry and other medical technologies. Eight experts from medicine, engineering, sociology, and anthropology shared insights with an audience of 60 participants from academia, the private sector, and federal government. Collectively, we developed several key insights for future progress on this issue and outlined a path forward for achieving equity now. You can access the full readout here. We’ll dive into the key highlights below:

Key Insights

Through discussions with experts during the forum, three key themes rose to the surface:

- Racial bias in pulse oximetry cannot be fixed by focusing on “race” alone. Existing evidence suggests reducing bias in pulse oximetry requires replacing devices with less-biased ones. This will take time as new devices are developed and will be a significant cost.

- Better calibration for skin tone is vital, but measurement is complicated. The crux of the problem is a comprehensive standard for quantifying the full range of skin pigmentation. This is vital to understanding how pulse oximeter accuracy varies by melanin content.

- Proactively identifying and addressing bias in medical devices will require system-wide efforts. Identification of bias in medical devices has been piecemeal rather than the outcome of proactive, deliberative efforts. Further efforts to address bias in medical devices should engage diverse stakeholders to establish best practices for ensuring equity in medical devices.

Resolving the problem of bias in pulse oximeter devices will likely take several years. But in the meantime, this issue will continue negatively impacting patients. Our participants urged that we need to think about actions that can be initiated this next year that will advance more equitable care with existing pulse oximeters.

Motivating Action for Equity Now

While a daunting problem, a collaborative, multi-stakeholder effort can bring us closer to solutions. We can work together to advance equity in standards of care by:

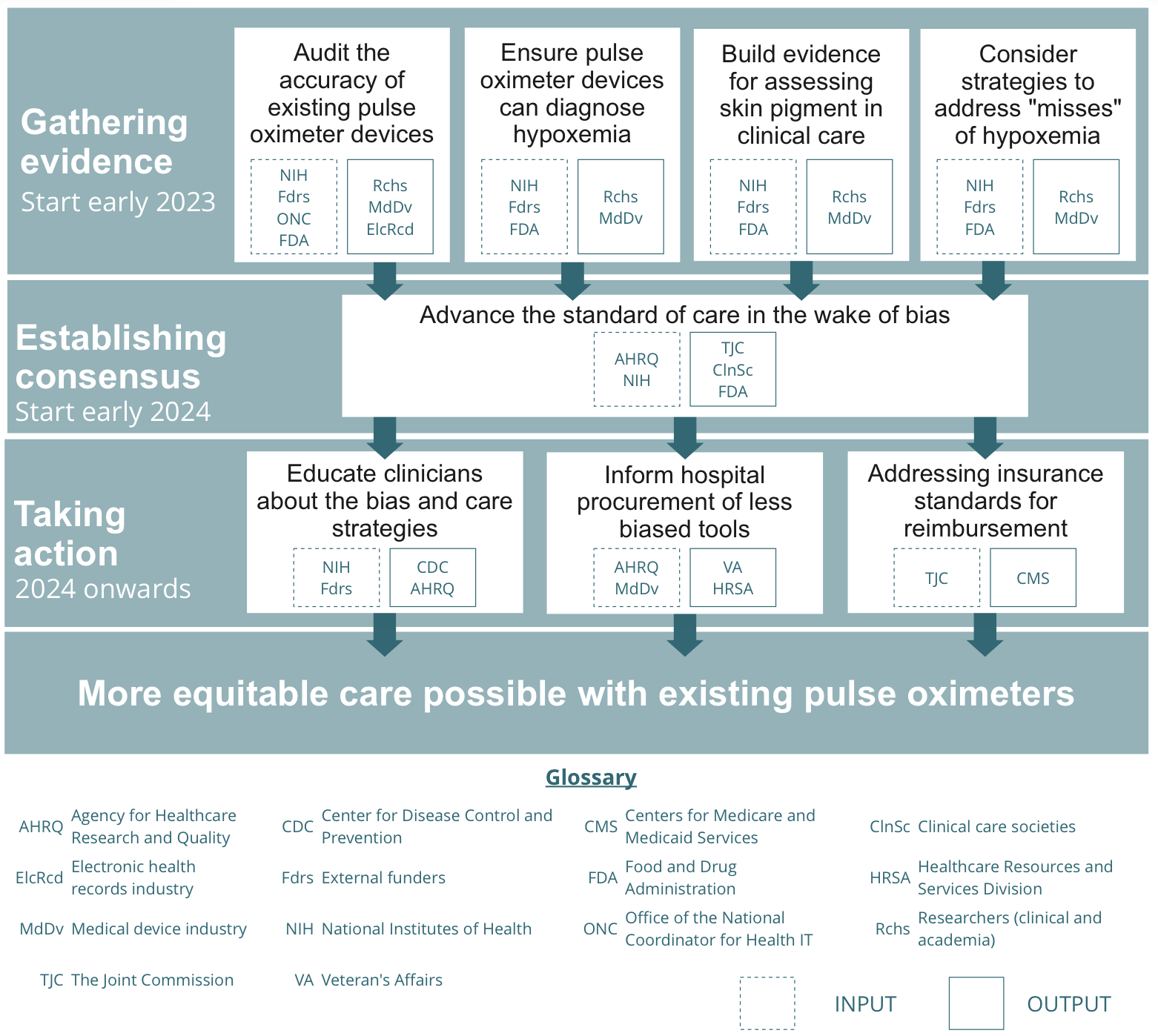

- Gathering evidence on existing pulse oximeter devices and their use in care [ASAP, start early 2023]. More evidence is required to identify the best approaches to equitable care with existing devices. This evidence gathering process should be initiated over the next year to inform clinicians on

- Establishing consensus to advance the standard of care [start early 2024]. After growing the body of evidence, there will be a need to convene around key conclusions derived from the evidence. Evidence synthesis will need to be generated and care societies will need to make decisions on how clinicians should use pulse oximeters in their care practice.

- Taking action to ensure equitable care nationwide [2024 onwards]. Once the care standards are changed, there is a need for system-wide efforts to communicate these to clinicians nationwide, inform procurement across federal hospitals, and re-evaluate insurance reimbursement standards.

Looking Ahead

This won’t be easy, but it’s 30 years overdue. We believe correcting the bias will pioneer a model that can be readily applied to combatting biases across the medical device ecosystem, something already underway in the United Kingdom with their Equity in Medical Devices Independent Review. Through a systematic approach, stakeholders can work to close racial disparities in the near-term and advance health equity.

The Federation of American Scientists supports Congress’ ongoing bipartisan efforts to strengthen U.S. leadership with respect to outer space activities.

By preparing credible, bipartisan options now, before the bill becomes law, we can give the Administration a plan that is ready to implement rather than another study that gathers dust.

Even as companies and countries race to adopt AI, the U.S. lacks the capacity to fully characterize the behavior and risks of AI systems and ensure leadership across the AI stack. This gap has direct consequences for Commerce’s core missions.

As states take up AI regulation, they must prioritize transparency and build technical capacity to ensure effective governance and build public trust.