By Hans M. Kristensen

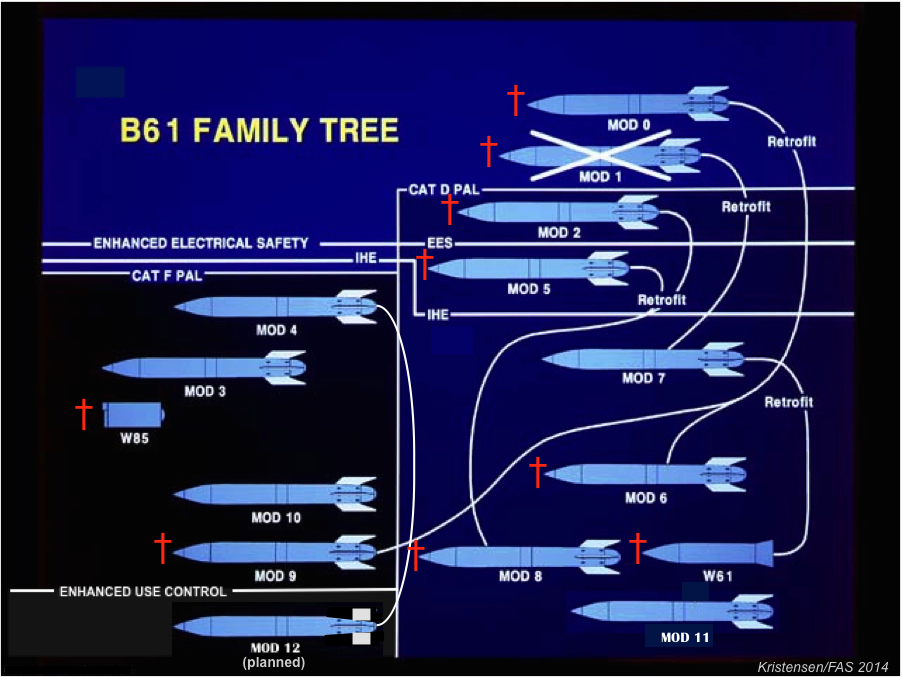

Robert Norris and I have made an update to our Nuclear Notebook on the B61 nuclear bomb family. Kind of an arcane title but that cozy-feeling title is what the nuclear weapon designers call that half a dozen different types of B61 nuclear weapons that were derived from the original design.

And it’s kind of timely, because the Obama administration is about to give birth to the newest member of the B61 family: the B61-12. And this is a real golden baby estimated at about $10 billion.

A Shrinking Family

The B61 family has lost a lot of members over the years. Nine of the fifteen total variations have been retired or canceled. The remaining five versions currently in the stockpile were built in 1979-1998.

Although based on the same basic warhead design first developed in the 1960s, the capabilities of the remaining version vary considerably with explosive yields ranging from 0.1 kilotons to a whopping 400 kilotons – more than 30 times as powerful as the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima in 1945.

Now the Obama administration has proposed that four of the remaining versions (B61-4, B61-7, B61-10, and B61-11) can be retired if the last version – the B61-4 – is converted into a guided standoff nuclear bomb. An even larger bomb, the B83-1, can also be retired, they say (even though its retirement was planned anyway).

The sales pitch is as arcane as the family name: building a new bomb is good for disarmament.

But most of the B61 bombs and the B83 could probably be retired anyway for the simple reason that deterrence no longer requires six different ways of dropping a nuclear bomb from an aircraft. A much simpler and cheaper life-extended version of the B61-7 could probably do the job.

Implications

The new B61-12 will be capable of holding at risk the same targets as current gravity bombs in the US stockpile (apparently even those currently covered by the B61-11 nuclear earth-penetrator that the Air Force no longer needs), but it will able to do so more effectively and with less yield (thus less collateral damage and radioactive fallout) that the existing bombs.

Congress rejected Air Force requests for new, low-yield, precision-guided nuclear weapons in the 1990s because of concern that such weapons would be seen as more usable than larger strategic warheads. With the B61-12, which will have several low-yield options, the military appears to obtain a guided low-yield nuclear strike capability after all.

In Europe, the effect of the B61-12 will be even more profound because its increased accuracy essentially will add high-yield targeting capability to NATO’s non-strategic arsenal. When mated with the stealthy F-35A fighter-bomber planned for Europe in the mid-2020s, the B61-12 will represent a considerable enhancement of NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

How they’re going to spin that development at the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference in New York next year will be interesting so see. But the B61-12 program is part of a global technological nuclear arms race with nuclear weapon modernization programs underway in all the nuclear-armed states that is in stark contrast to the wishes of the overwhelming number of countries on this planet to see the “cessation of the nuclear arms race at early date and to nuclear disarmament,” as enshrined in the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (more about that in the May issue of Arms Control Today).

Download the B61 Family article here.

For previous articles about the B61-12, click here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.