Urgent: Move US Nuclear Weapons Out Of Turkey

Should the U.S. Air Force withdraw the roughly 50 B61 nuclear bombs it stores at the Incirlik Air Base in Turkey? The question has come to a head after Turkey’s invasion of Syria, Erdogan’s increasingly authoritarian leadership and deepening discord with NATO, Trump’s inability to manage U.S. security interests in Europe and the Middle East, and war-torn Syria only a few hundred miles from the largest U.S. nuclear weapons storage site in Europe.

According to The New York Times, State and Energy Department (?) officials last weekend quietly reviewed plans for evacuating the weapons from Incirlik. “Those weapons, one senior official said, were now essentially Erdogan’s hostages. To fly them out of Incirlik would be to mark the de facto end of the Turkish-American alliance. To keep them there, though, is to perpetuate a nuclear vulnerability that should have been eliminated years ago.”

That review is long overdue! [Actually, I’ve heard there have been several reviews and a lively internal debate since the 2016 coup attempt.] Some of us have been calling for withdrawal for years (see here and here), but officials have resisted saying it wasn’t as bad as it looked and that the deployment still served a purpose. They were wrong. And by waiting so long to act, the United States has painted itself into a corner where the choice between nuclear security and abandoning Turkey has become unnecessarily stark and urgent.

The situation is even more untenable because Incirlik in just a few years is scheduled to receive a large shipment of the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, which would be a recommitment to nuclear deployment in Turkey.

This year is the 60th anniversary of the first deployment of nuclear weapons to Turkey. It is time to bring them home.

Nuclear Weapons At Incirlik

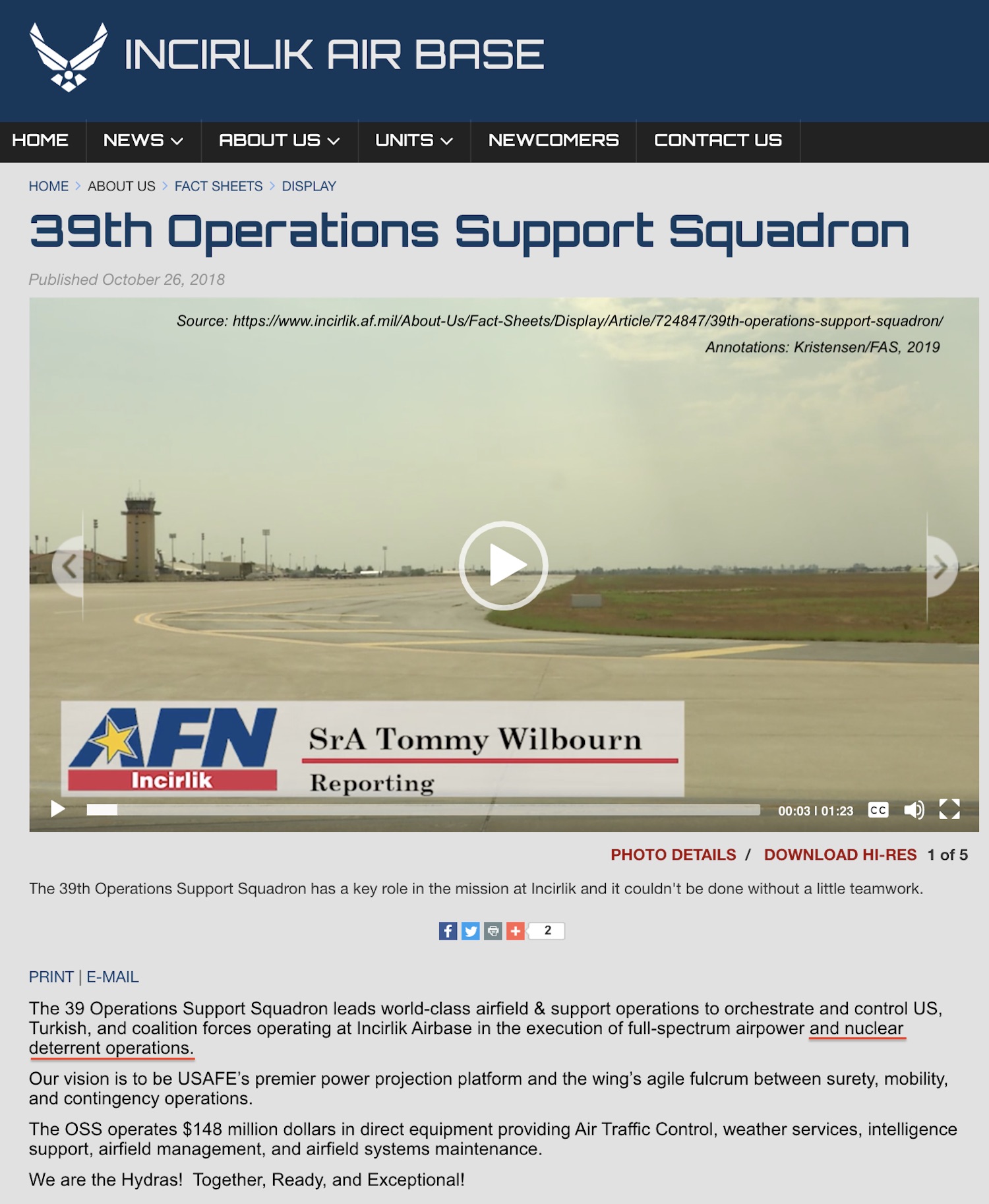

The specific reference in the New York Times article made by officials to nuclear weapons at Incirlik is the most recent and authoritative confirmation that nuclear weapons are still stored at the base. That confirms what I have been hearing and sources at US Air Forces Europe confirmed the report, telling William Arkin the weapons are still there. There have been rumors the weapons were removed after the coup attempt in 2016 (and some really bad disinformation that they had been moved to Romania). All of those rumors were wrong. An article on the official Incirlik Air Base web site even confirms that the mission of the 39th Operations Support Squadron is “to orchestrate and control US, Turkish, and coalition forces operating at Incirlik Airbase in the execution of full-spectrum airpower and nuclear deterrent operations” (emphasis added). Given that the article will likely be removed now that I have pointed this out, it is reproduced in full below:

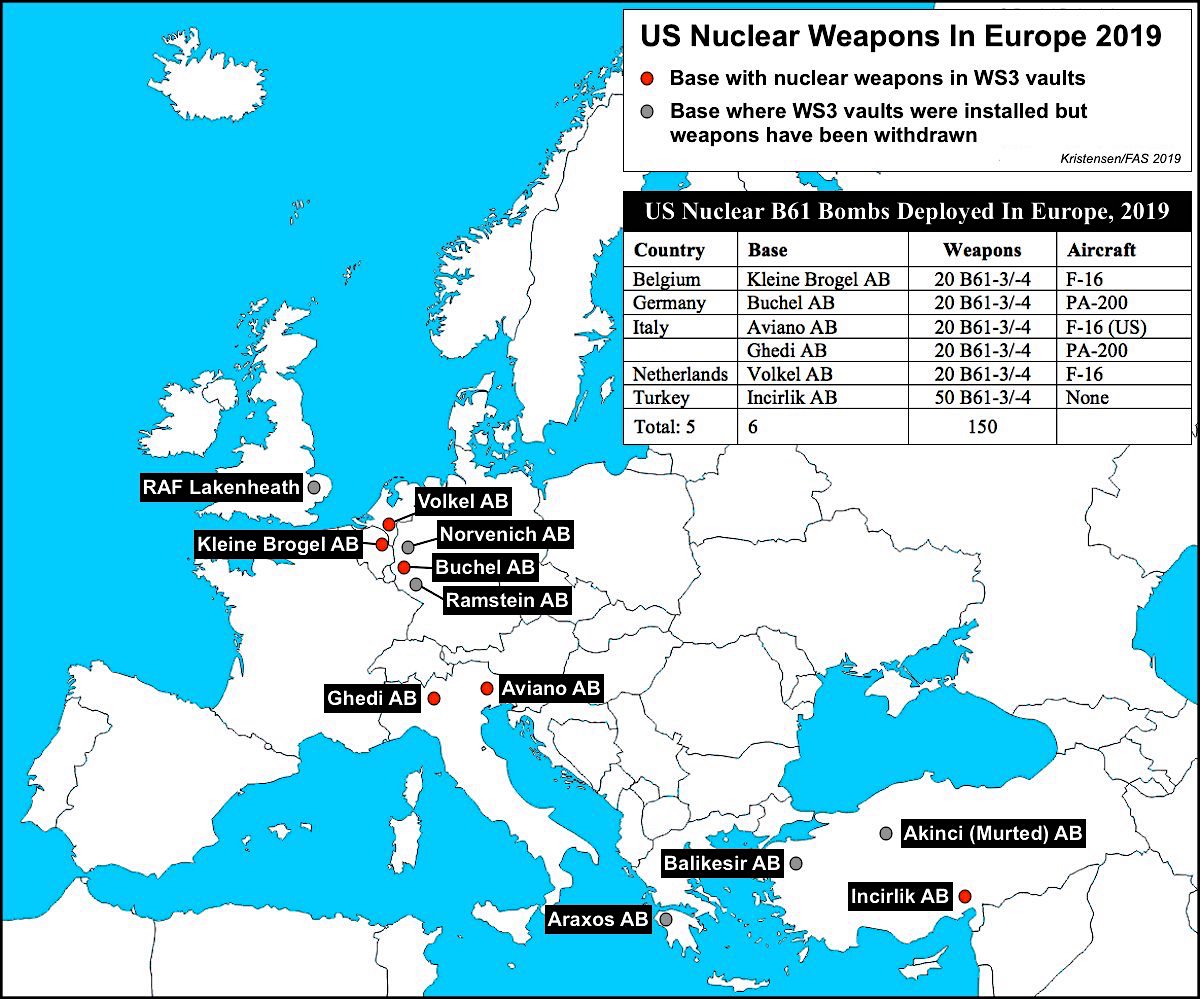

I have estimated for the past several years that the Air Force stores about 50 B61 nuclear gravity bombs at Incirlik, one-third of the 150 nuclear weapons currently deployed in Europe (see figure below). This estimate has been used by a wide range of news reports and commentators. The number of bombs at Incirlik has decreased over the past two decades from 90 in 2000. In those days, 40 of the 90 bombs were earmarked for delivery by Turkish F-16s. Those 40 bombs used to be stored in 6 vaults at both Akinci AB and Balikesir AB (20 at each) until they were moved to Incirlik when the US Air Force withdrew its Munition Support Squadrons from the Turkish bases in 1996. The 40 “Turkish” bombs remained at Incirlik until around 2005 when they were shipped back to the United States as part of the Bush administration’s unilateral nuclear reduction in Europe.

The US Air Force stores 150 nuclear bombs at six bases in five NATO countries. Click on map to view full size.

The remaining 50 bombs are for use by US jets, even though Turkey never allowed the US Air Force to permanently base fighter-squadrons at Incirlik. Jets would have to fly in during a crisis to pick up the weapons or they would have to be shipped to other locations before use. As a result, the nuclear posture at Incirlik has been more a storage site than a fighter-bomber base during the past two decades.

Although the Turkish participation in the NATO nuclear sharing mission was lessened (some would say mothballed) by the withdrawal of the “Turkish” weapons, the Turkish F-16s continued to serve a nuclear role. Despite local reports that F-16s never had a nuclear role, the US Air Force in 2010 informed Congress that “Turkey uses Turkish F-16s to execute their nuclear mission,” and that some of the F-16s would be upgraded to be able to deliver the new B61-12 bomb until the F-35A could take over the nuclear strike mission in the 2020s. That is now not going to happen after the Trump administration canceled the F-35 sale.

In 2015, satellite images revealed construction of a new security perimeter around most of the aircraft shelters with nuclear weapons storage vaults. Of the 25 shelters that originally were equipped with vaults, only 21 were included in the new security area with a capacity to store up to a maximum of 84 nuclear bombs. Normally only about two bombs are stored in each vault, for a total of inventory of 40-50 bombs at Incirlik.

The nuclear weapons mission areas at Incirlik AB include the “NATO Area” where nuclear weapons are stored and the nuclear weapons maintenance unit that manages the underground storage vaults

As recently as last month, Vice Chief Staff of the Air Force, Gen. Stephen W. Wilson, visited Incirlik and was given tours of the various functions and facilities at the base. One of these was Protective Aircraft Shelter H-2 inside the “NATO Area” where he spoke to members of the 39th Security Force that protects the nuclear weapons (see below). He was likely also shown the inside of the shelter and the weapons in the vault.

Last month, the Air Force Chief of Staff was taken to a nuclear weapons storage shelter at Incirlik AB. Click on image to view full size.

Recent Activities

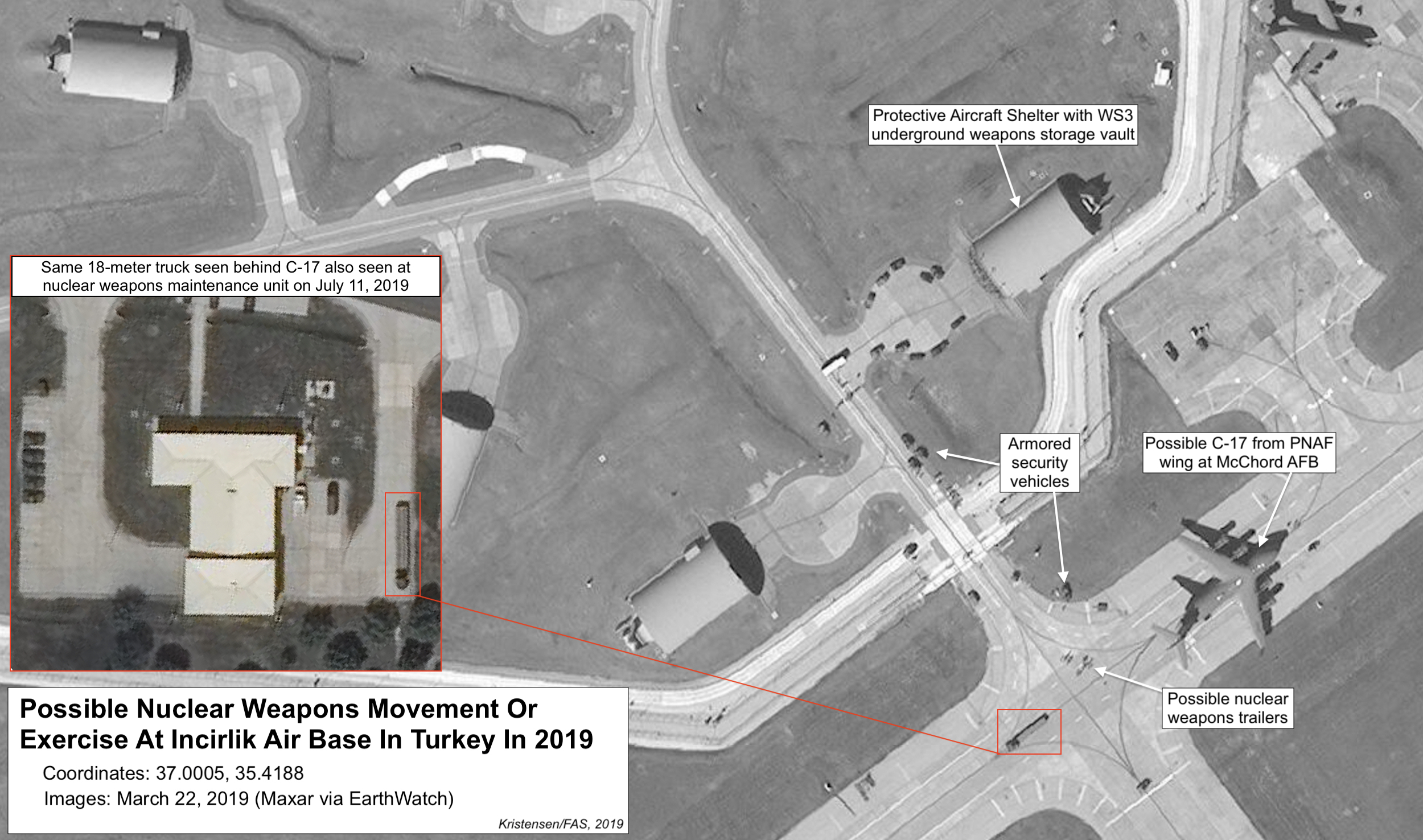

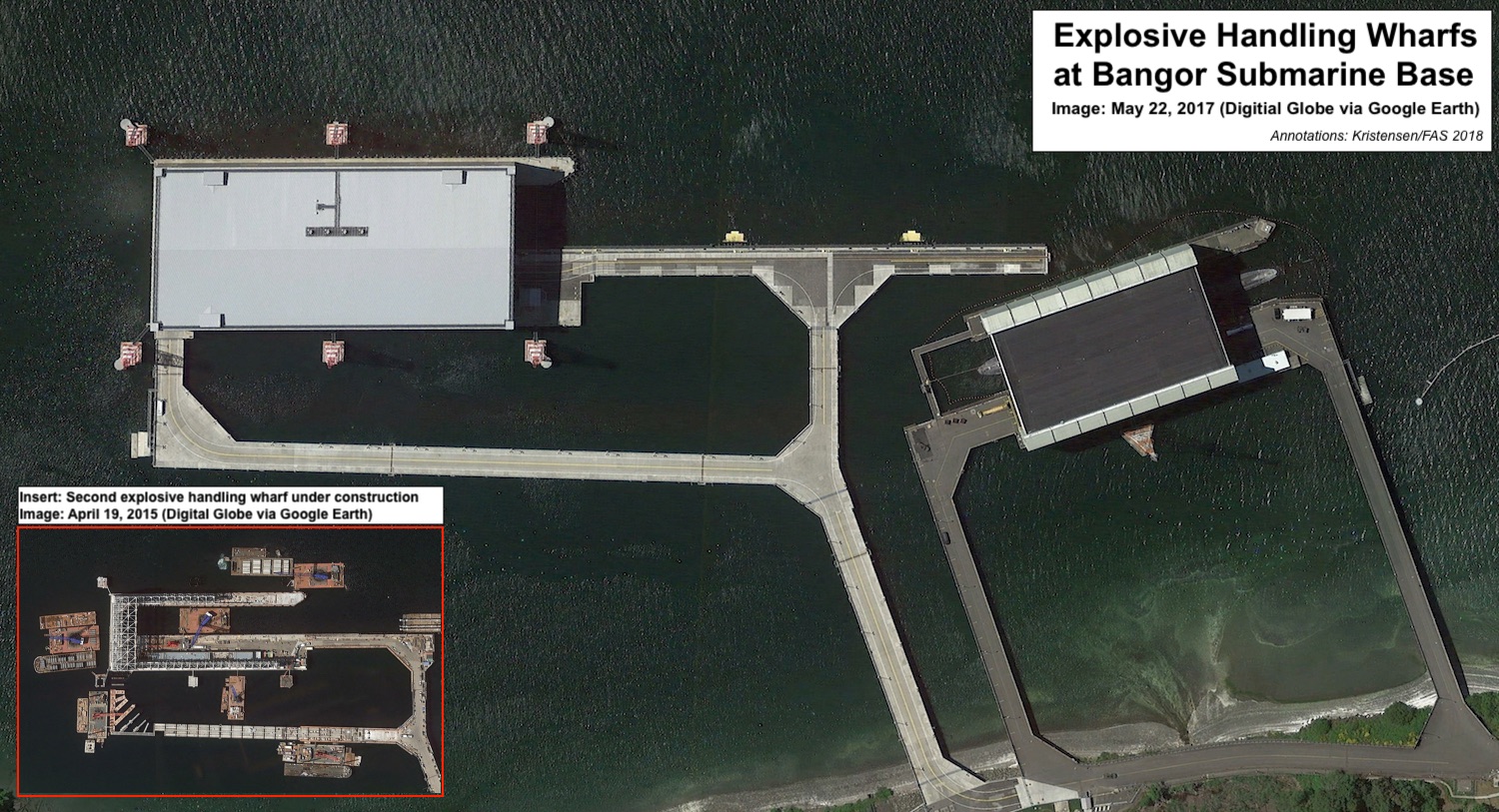

If the Air Force decided to withdraw the B61 bombs from Incirlik, it would look pretty much like activities captured by Maxar’s satellites in 2019 and 2017. Those images show what appears to be either actual nuclear weapons movements or training to remove them.

One photo from March 22, 2019, shows a C-17 transport aircraft – likely from the 4th Airlift Squadron of the 62nd Airlift Wing at Joint Base Lewis-McChord in Washington – parked right outside the main gate to the NATO Area. The 4th Airlift Squadron, which is the only unit in the Air Force that is qualified to airlift nuclear weapons, flies Prime Nuclear Airlift Force (PNAF) and Emergency Nuclear Airlift Operations (ENAO) missions (see images below).

The satellite image shows the C-17 and gate area surrounded by armored vehicles and armed guards of the 39th Security Force as well as technicians to protect and carry out the weapon movement. One of the unique vehicles seen is an 18-meter truck lined up with the loading pad of the C-17. The same type of truck can be seen parked at the weapons maintenance unit building a few months later (see image below).

This Maxar satellite image acquired via Earth Watch shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in March 2019. Click on image to view full size.

Another set of Maxar satellite photos of a possible nuclear weapons movement or exercise is from December 2017. A Nuclear Security Inspection that year (and 2014) reportedly included weapons emergency evacuation drills. The scenario on the 2017 image is similar to that on the 2019 image: a C-17 parked outside the gate, security vehicles surrounding the scene, and transporters for moving weapons. But the 2017 photos are unique because they were taken moments apart as the satellite passed overhead. As a result, movements become visible: On the first image, a possible weapons trailer towed behind a truck in a column of armored security vehicles is moving toward the outer gate of the NATO Area. On the second photo, the column has passed through the gate onto the tarmac and the towed trailer is turning toward the rear of the C-17. The aircraft shadow shows the loading ramp is open and ready to receive the weapons (see image below).

This unique double-image shows what appears to be a nuclear weapons movement or exercise in December 2017. Click on image to view full size.

The Task At Hand: Withdraw The Weapons!

The B61 nuclear bombs at Incirlik should have been withdrawn long ago but tradition, Cold War thinking, and bureaucratic inertia prevented officials from doing the right thing. Now things have come to a head where the United States is faced with the choice of securing its weapons or be seen as abandoning Turkey.

Withdrawing the weapons does not, of course, mean the United States is abandoning Turkey. That relationship is already in serious trouble and keeping the weapons at Incirlik based on the idea that it will somehow counterweight Turkey’s further drift away from NATO is probably an illusion. That boat seems to have sailed; the relationship is likely to deteriorate whether or not there are nuclear weapons at Incirlik. That is the reality the Air Force must relate to now.

Another argument against withdrawal will be that moving them out of Turkey will cause the other members of the so-called nuclear sharing arrangement (Belgium, Germany, Holland, Italy) to question why they should continue to store U.S. nuclear weapons. Withdrawal from Turkey could, so the argument goes, trigger a domino effect of withdrawal from other countries as well.

But the withdrawal of U.S. nuclear bombs from Greece in 2001 and from England five years later did not cause the other countries to demand withdrawal as well or the collapse of NATO. If they truly believe deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons is important for NATO security, then they will stay. If the mission falls with withdrawal from Turkey, then they obviously don’t think it’s important and the weapons should be withdrawn from all the countries anyway. The U.S. extended deterrence posture in Europe can adequately be maintained with advanced conventional forces backed up by strategic forced in the background.

The B61 bombs at Incirlik could easily be dispersed to empty storage vaults in the other countries. Space is not a problem. There are a total of 96 empty weapon slots in the active WS3 vaults in Belgium, Germany, Holland, and Italy. Moreover, there are 25 empty and inactive WS3 vaults with room for 100 bombs at RAF Lakenheath. But public and parliamentary opposition would likely prevent increasing the number of nuclear bombs stored in those countries. If the order goes out to evacuate Incirlik, it seems more likely the bombs would be returned to the United States.

There will be some people who will argue that deteriorating relations with Russia and Moscow’s alleged increased reliance on a so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” strategy of using tactical nuclear weapons first prevent the United States from reducing – certainly withdrawing – its tactical nuclear weapons from Europe. Those are curiously the same people who also argue that the United States should deploy a new low-yield warhead on its strategic submarines and a new nuclear cruise missile on its attack submarines to better counter Russian tactical nuclear weapons – a thinking that was recently endorsed by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review. That seems to signal to the European allies that the United States actually no longer believes the deployment of B61 nuclear bombs in Europe is credible and that other and better weapons are needed.

Whatever one might think about U.S. tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, Turkey is no longer an acceptable location. Erdogan’s confrontational and authoritarian leadership is rapidly undermining Turkey’s status as a reliable NATO ally, and the deteriorating security situation in the region presents a real physical threat to the weapons at Incirlik. That threat is real and the U.S. military sees it as real. So much so that an extra security force squadron deployed to Incirlik from Aviano Air Base in Italy to beef up nuclear security in response to “regional turmoil and government instability” according to USAF source, and Ohio Army National Guard military police reportedly were dispatched to Incirlik specifically to increase base security.

The security threat to the weapons at Incirlik is urgent and the continued deployment of nuclear weapons at the location is unjustifiable and incompatible with U.S. nuclear security standards. If you don’t believe that, ask yourself this question: If there were no U.S. nuclear weapons in Turkey and someone asked for them to be deployed to Incirlik, would the Pentagon approve?

I doubt it. It’s time to face reality and withdraw the weapons from Turkey before they have to be evacuated under fire.

Additional information:

- US nuclear weapons, 2019

- Tactical nuclear weapons, 2019

- Upgrades At US Bases In Europe Acknowledge Security Risk (2015)

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

New START Treaty Data Shows Treaty Keeping Lid On Strategic Nukes

The latest data on US and Russian strategic nuclear forces limited by the New START treaty shows the treaty is serving its intended purpose of keeping a lid on the two countries’ arsenals.

The data was published by the State Department yesterday.

Despite deteriorating relations and revival of “Great Power Competition” strategies, the data shows neither side has increased deployed strategic force levels in the past year.

The data set released is the last before the New START treaty enters its final year before it expires in February 2021. The treaty can be extended for another five years by the stroke of a pen, but arms control opponents in Washington and Moscow are working hard to prevent this from happening. If they succeed, the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals will be completely unregulated for the first time since the 1970s.

By The Numbers

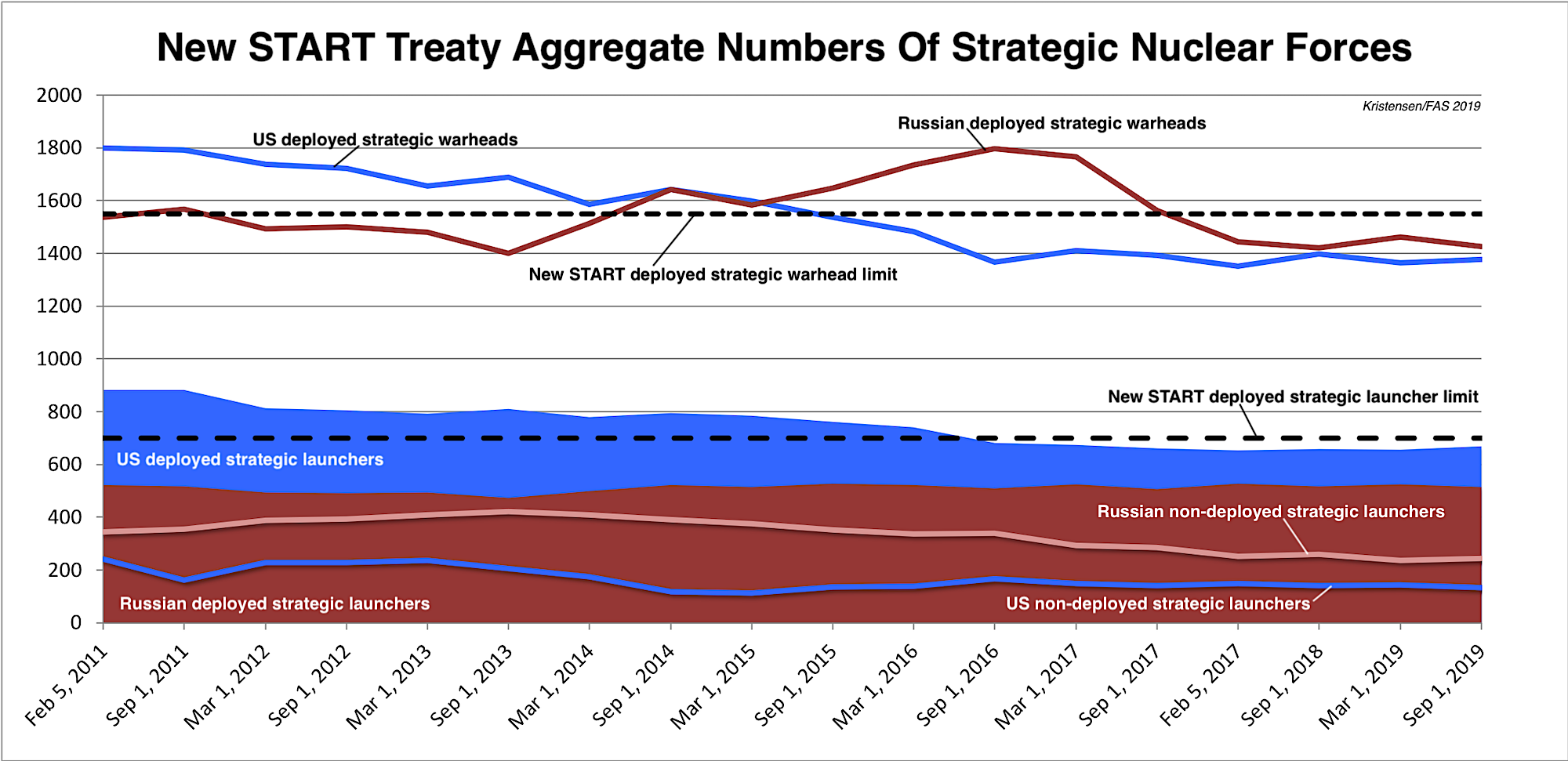

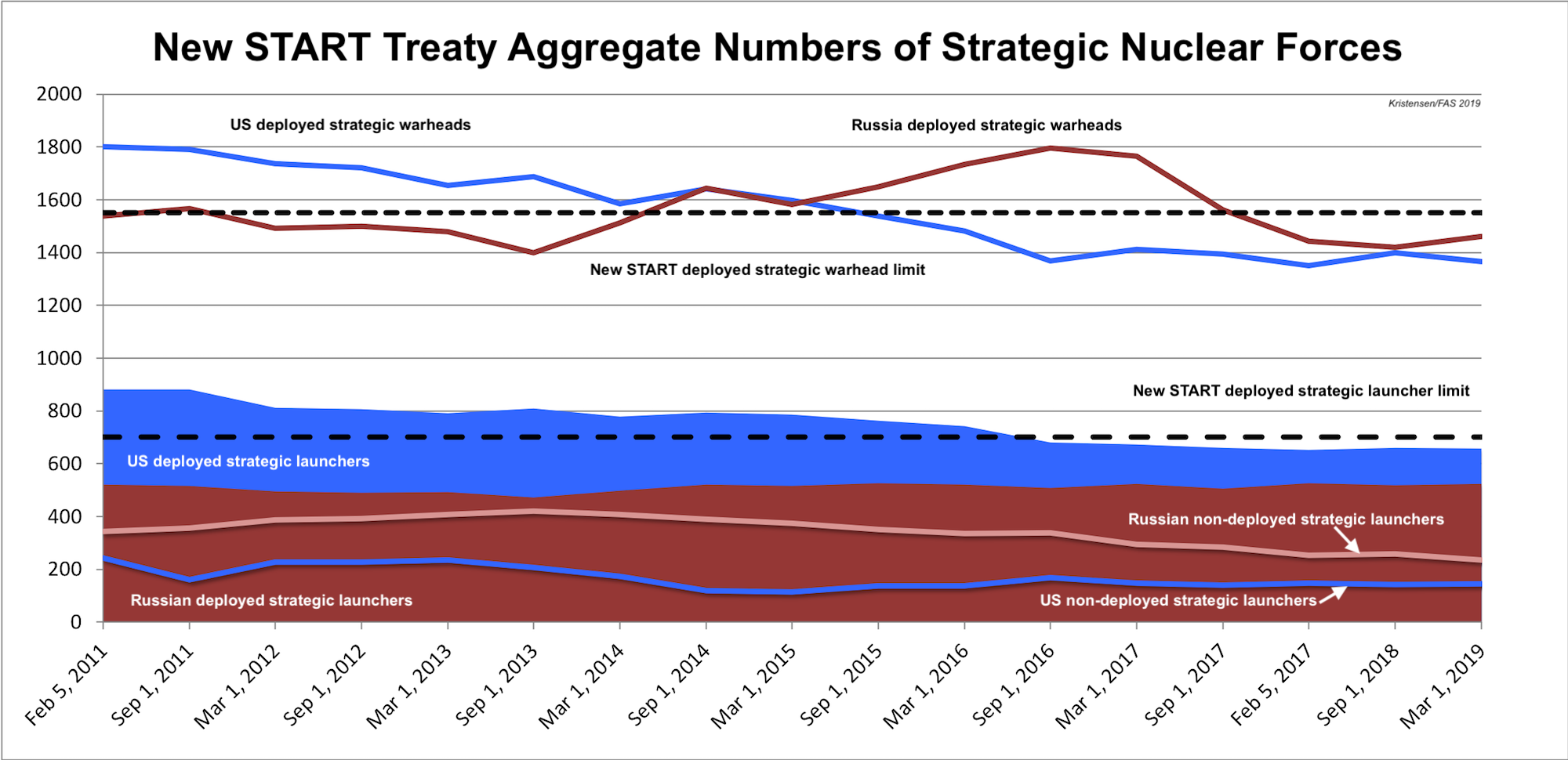

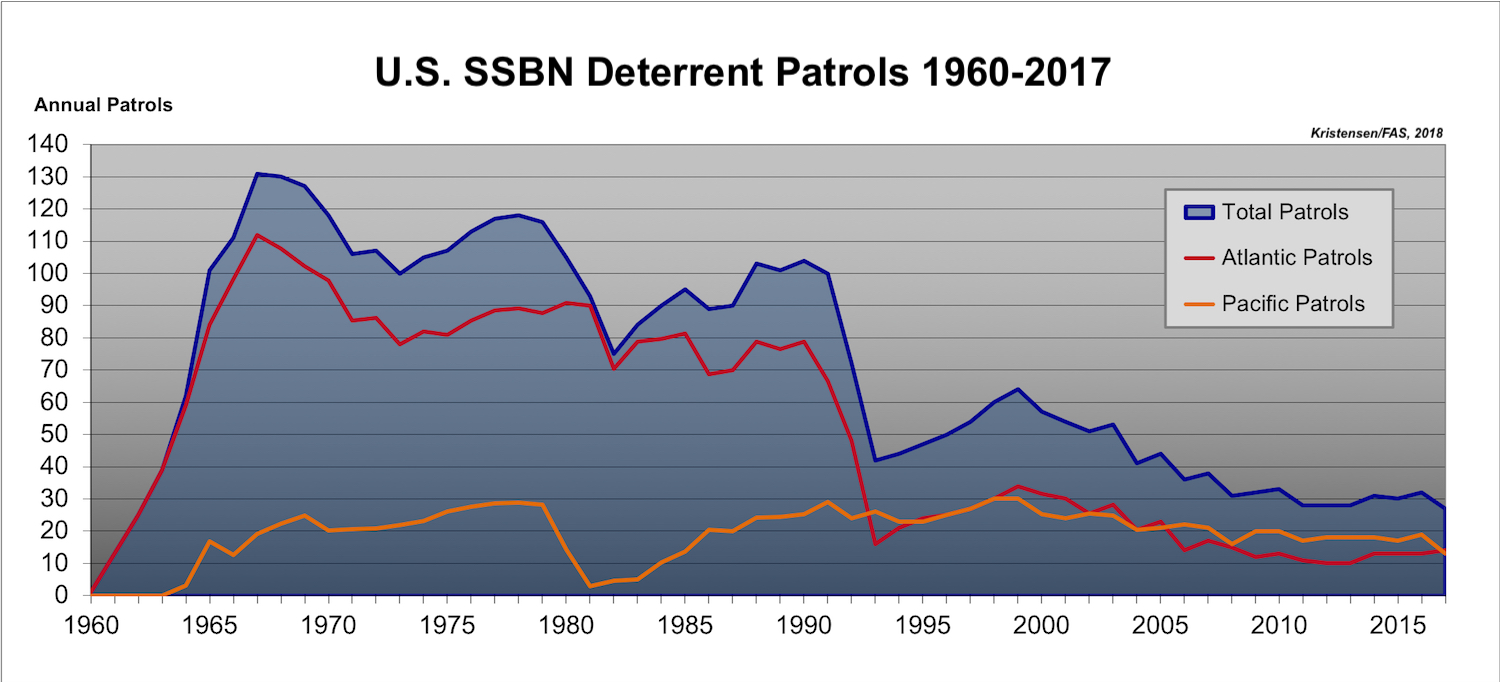

The latest data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,181 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,802 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). That is very close to the combined forces they deployed six months ago. These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 513 deployed strategic launchers with 1,426 warheads. That’s a slight decrease of 11 launchers and 3 warheads compared with March 2019. Russia is currently 187 launchers and 124 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 668 strategic launchers with 1,376 warheads attributed to them, according to the new data, or a slight increase of 12 launchers and 11 warheads compared with March 2019. The United States is currently 32 launchers and 174 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since March 2019 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the force structure or threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,330 warheads for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,500 and 6,185, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement). Both sides could upload many hundreds of warheads extra on their launchers if New START was allowed to expire.

Build-Up, What Build-Up?

Both Russia and the United States are engaged in significant modernization programs to extend and improve their strategic nuclear forces. So far, however, these programs largely follow the same overall structure and are unlikely to significantly change the strategic balance of those forces. The New START data shows the treaty is serving to keep a lid on those modernization plans.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not yet deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). The Trump administration is complaining these new weapons should be included in the treaty. A third weapon, an ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard, is close to initial deployment and will be accountable under the treaty but would likely replace existing deployed warheads. All of these weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces and the new data shows it does not appear to try to close the significant gap that exists in the number of deployed strategic launchers – 155 in US favor by the latest count (up 23 launchers from March 2019). To put things in perspective, 155 launchers are the equivalent of an entire US ICBM wing, or more than seven Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines fully loaded, or more than twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would certainly be complaining about a Russian advantage. Given this launcher disparity, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers (down 12 since March 2019).

Instead of trying to close the launcher gap, Russia is compensating for the disparity by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles to be able to keep overall parity with the United States. Since 2016, the New START data indicates that Russia has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian deployed strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could potentially – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed strategic launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits or the treaty was allowed to expire in 2021. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs. Significantly increasing the force structure, however, would take decades to achieve because both sides have based their long-term planning on the assumption that the New START force level would continue.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,” as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US to a conventional role cannot be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility, however, and the US insists the conversions have been carried out in accordance with the treaty provisions that Russia agreed to when it signed the treaty.

The Russia complaints about converted launchers and the US complaints about incorporating new strategic weapons are issues that should be resolved in the treaty’s Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

The US complains new Russian strategic weapons should be included in New START and Russia complains it can’t verify irreversibility of converted US launchers

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 313 onsite inspections (25 this year) and 18,803 notifications (2,387 last 12 months). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

What Now?

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: New START is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian complaints that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

This all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, that’s what they’ll get.

It is essential that Russia and the United States decide now to extend the New START treaty. Without it, the two sides will switch into a worst-case-scenario mindset for long-term planning of strategic forces that could well trigger a new nuclear arms race.

Additional information:

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russia nuclear forces, 2009

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces, 2019

- Status of world nuclear forces

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

No Bret, the U.S. Doesn’t Need More Nukes

Last week, on the 74th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, many took time to reflect upon the destruction caused by the only uses of nuclear weapons in wartime. But not the New York Times’ Bret Stephens, who took the opportunity to argue in favor of building more nuclear weapons.

In an op-ed entitled “The U.S. Needs More Nukes,” Stephens laid out his case against arms control: “the bad guys cheat, the good guys don’t,” and all the while, the US nuclear arsenal is becoming “increasingly decrepit.”

It’s a simple narrative; it’s also false. In fact, Stephens’ article is largely littered with bad analogies, flawed assumptions, and straight-up incorrect facts about the nature of nuclear weapons and arms control.

As examples of arms control agreements where the “bad guys cheat” and the “good guys don’t,” Stephens cites the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (from which the United States withdrew in 2002), the Iran Deal (which was working until the United States withdrew last year), and the Treaty of Versailles (which famously isn’t an arms control agreement), among others. None of these involved significant cheating on the part of the “bad guys,” unless you count the Trump administration’s violation of the Iran Deal in 2018.

Stephens also cites the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty as a prime example of an arms control agreement gone wrong. Yes, it appears that Russia likely violated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty by developing and deploying a banned ground-launched cruise missile; however, as we’ve written previously, Trump’s decision to pull out of the treaty makes the United States needlessly complicit in its demise and frees Russia from both the responsibility and pressure to return to compliance. Contrary to Stephens’ thesis, when someone breaks the law, you shouldn’t throw away the law.

And contrary to the title of Stephens’ piece, the United States doesn’t need more nukes. As we explain in our latest US Nuclear Notebook, the Trump administration wants to develop two new ones––a low-yield warhead and a sea-launched cruise missile––both of which are dangerous, and neither of which are necessary. Aside from lowering the threshold for nuclear use, the “low-yield” aspect of the low-yield warhead is a misnomer; it’s roughly one-third the yield of the Hiroshima bomb that killed 100,000 people. And the new sea-launched cruise missile is a concept brought back from the dead: the United States had one until 2013, when the Obama administration retired it because it was pointless, wasteful, and politically controversial.

In addition to his well-established denialism of issues like systemic hunger, rape culture, and climate change, Stephens is known for his hawkish––and often inaccurate––takes on nuclear issues. In 2013, he claimed that the Iran Deal was worse than Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler in 1938. In 2017, he argued in favor of regime change in North Korea. Later that year, he derisively referred to ICAN––the group that won the Nobel Peace Prize for its work to ban nuclear weapons––as “another tediously bleating ‘No Nukes’ outfit.” In June, he wrote that “If Iran won’t change its behavior, we should sink its navy.” Remember, this is coming from a guy who awarded Iraq War architect Paul Wolfowitz “Man of the Year” in 2003 (The runners-up? Donald Rumsfeld, Dick Cheney, Tony Blair, and George W. Bush).

Furthermore, in last week’s piece, he erroneously stated that Iran repeatedly violated the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, a claim which the International Atomic Energy Agency—the international organization charged with monitoring Iran’s compliance––has continuously rebutted. Noticeably, Stephens linked to Mark Fitzpatrick’s work to back up his claim, but when Mark tweeted out that his article didn’t say anything of the sort, the link was changed. It now references David Albright of the Institute for Science and International Security, who is known for his hawkish views on Iran.

Stephens’ columns are clearly emphasizing ideology over accuracy. And publishing a pro-nukes article on the anniversary of the Nagasaki bombing––without acknowledging the human cost of nuclear weapons, or even the anniversary itself––demonstrates that he is clearly not guided by empathy.

But perhaps most evidently, Stephens’ piece is driven by fear. And understandably so: we’re currently locked into an ever-increasing nuclear arms race with no signs of it slowing down. If you’re not afraid, you’re probably not paying attention. However, crying “more nukes” without articulating any kind of strategic vision isn’t going to get us out of this mess.

In reality, the best way to get out of an arms race is by refusing to play. The United States shouldn’t base the size of its nuclear arsenal in response to how other countries are tweaking theirs––this only makes sense if you believe that nuclear weapons are for fighting wars. But to quote Reagan’s old adage, “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” Instead, as explained in Global Zero’s Alternative Nuclear Posture Review, the United States should move towards a “deterrence-only” nuclear posture, which would allow for sizable cuts to the US nuclear arsenal without changing the strategic balance.

Very simply, we need to start enacting ambitious solutions that are equal to the problems that we face. Not just reflexively demanding more nukes.

—

(image: Yosuke Yamahata, one day after the Nagasaki bombing)

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The INF Treaty Officially Died Today

Six months after both the United States and Russia announced suspensions of their respective obligations under the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), the treaty officially died today.

The Federation of American Scientists strongly condemns the irresponsible acts by the Russian and US administrations that have resulted in the demise of this historic and important agreement.

In a they-did-it statement on the State Department’s web site, Secretary of State Michael Pompeo repeated the accusation that Russia has violated the treaty by testing and deploying a ground-launched cruise missile with a range prohibited by the treaty. “The United States will not remain party [sic] to a treaty that is deliberately violated by Russia,” he said.

By withdrawing from the INF, the Trump administration has surrendered legal and political pressure on Russia to return to compliance. Instead of diplomacy, the administration appears intent on ramping up military pressure by developing its own INF missiles.

Signed in 1987, the INF Treaty dramatically helped reduce nuclear threats and stabilize the arms race for thirty-two years, by banning and eliminating all US and Russian ground-launched missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers––a grand total of 2,692 missiles. And it would have continued to have a moderating effect on US-Russia nuclear tensions indefinitely, if not for the recklessness of both the Putin and Trump administrations.

The United States first publicly accused Russia of violating the treaty in its July 2014 Treaty Compliance Report, stating that Russia had broken its obligation “not to possess, produce, or flight-test a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) with a range capability of 500 km to 5,500 km, or to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.” Russia initially denied the US claims, repeating for years that no such missile existed. However, once the United States publicly named the missile as the 9M729––or SSC-8, as NATO calls it––Russia acknowledged its existence but stated that the missile “fully complies with the treaty’s requirements.” Since then, the United States claimed that Russia had flight-tested the 9M729 from fixed and mobile launchers to deceive, and has deployed nearly a hundred missiles across four battalions.

We assess that involves 16 launchers with 64 missiles (plus spares), likely collocated with Iskander SRBM units at Elanskiy, Kapustin Yar (possibly moved to a permanent base by now), Mozdok, and Shuya. It is possible, but unknown, if more battalions have been deployed.

It is possible that Russia made the decision to violate the INF Treaty as early as 2007, when its UN proposal to multilateralize the treaty failed. Although it’s likely that the groundwork was laid even further back. According to Putin, a new arms race truly began in 2002 when the Bush administration withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty––understood by Putin to be the cornerstone of the US-Russia arms control regime.

For its part, Russia has responded to US accusations with claims that the United States is the true violator of the treaty, stating that US missile defense launchers based in Europe could be repurposed to launch INF-prohibited missiles, among other violations. In a detailed report, the Congressional Research Service has refuted all three accusations.

Regardless of who violated the INF, the Trump administration’s decision to kill the treaty is the wrong move. As we wrote in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists when Trump first announced his intention to quit the treaty, withdrawal establishes a false moral equivalency between the United States, who probably isn’t violating the treaty, and Russia, who probably is. It also puts the United States in conflict with its own key policy documents like the Nuclear Posture Review and public statements made last year, which emphasized bringing Russia back into compliance through diplomatic, economic, and military measures.

The bottom line is this: when someone breaks the law, you shouldn’t throw away the law. By doing so, you remove any chance to hold the violator accountable for their actions. If the ultimate goal is to coax or coerce Russia back into compliance with the treaty, then killing the treaty itself obviously won’t achieve that. Instead, it legally frees Russia to deploy even more INF missiles.

The decision to withdraw wasn’t based on long-term strategic thinking but appears to have been based on ideology. It was apparently the product of National Security Advisor John Bolton––a hawkish “serial arms control killer”––having the President’s ear. Defense hawks chimed in with warnings about Chinese INF-range missiles being outside the treaty (which they have always been) and recommendations about deploying new US INF missiles in the Pacific.

Now, we find ourselves on the brink of an era without nuclear arms control whatsoever. With the demise of the INF, the only remaining treaty – the New START treaty – is in jeopardy, a vital treaty that caps the number of strategic nuclear weapons the United States and Russia can deploy and provides important verification and data exchanges. Although it could easily be extended past its February 2021 expiry date with the stroke of a pen, John Bolton maddeningly says that it’s “unlikely.” And Russian officials too have begun raising issues about the extension. Allowing New START to expire would do away with the last vestiges of US-Russia nuclear restraint, and open the world up to a new open-ended nuclear arms race.

Congress must do whatever it can to convince President Trump to extend the New START treaty.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Russia Upgrades Western Nuclear Weapons Storage Sites

Amidst a deepening rift between the United States and Russia about the role of non-strategic nuclear weapons, Russia has begun to upgrade an Air Force nuclear weapons storage site near Tver, some 90 miles (145 kilometers) northeast of Moscow.

Satellite photos show clearing of trees within the site as well as the construction of a new security fence and guard post. The upgrade, which started late-2017 and was completed late last year, was followed by the arrival of what appears to be weapons transport and service trucks earlier this year (see image below).

The Tver site includes two nuclear weapons bunkers as well as service and security buildings. The new security fence and gate added within the site separates the bunker area from the service area. The site is near the Migalovo Air Base, which is not thought to be housing nuclear strike aircraft but might serve a nuclear weapons transport function. If so, it could potentially be responsible for the distribution of nuclear warheads to tactical air bases in north-western Russia in a crisis.

It is impossible to determine from the satellite images if the Tver site stores nuclear weapons at this time, but it is clearly active with considerable personnel and activities indicating weapons might be present. Alternatively, Tver could serve as an Air Force storage site in a crisis. Tver is one of several dozen nuclear weapons storage sites operated by the Russian ministry of defense and military services (see here and here.

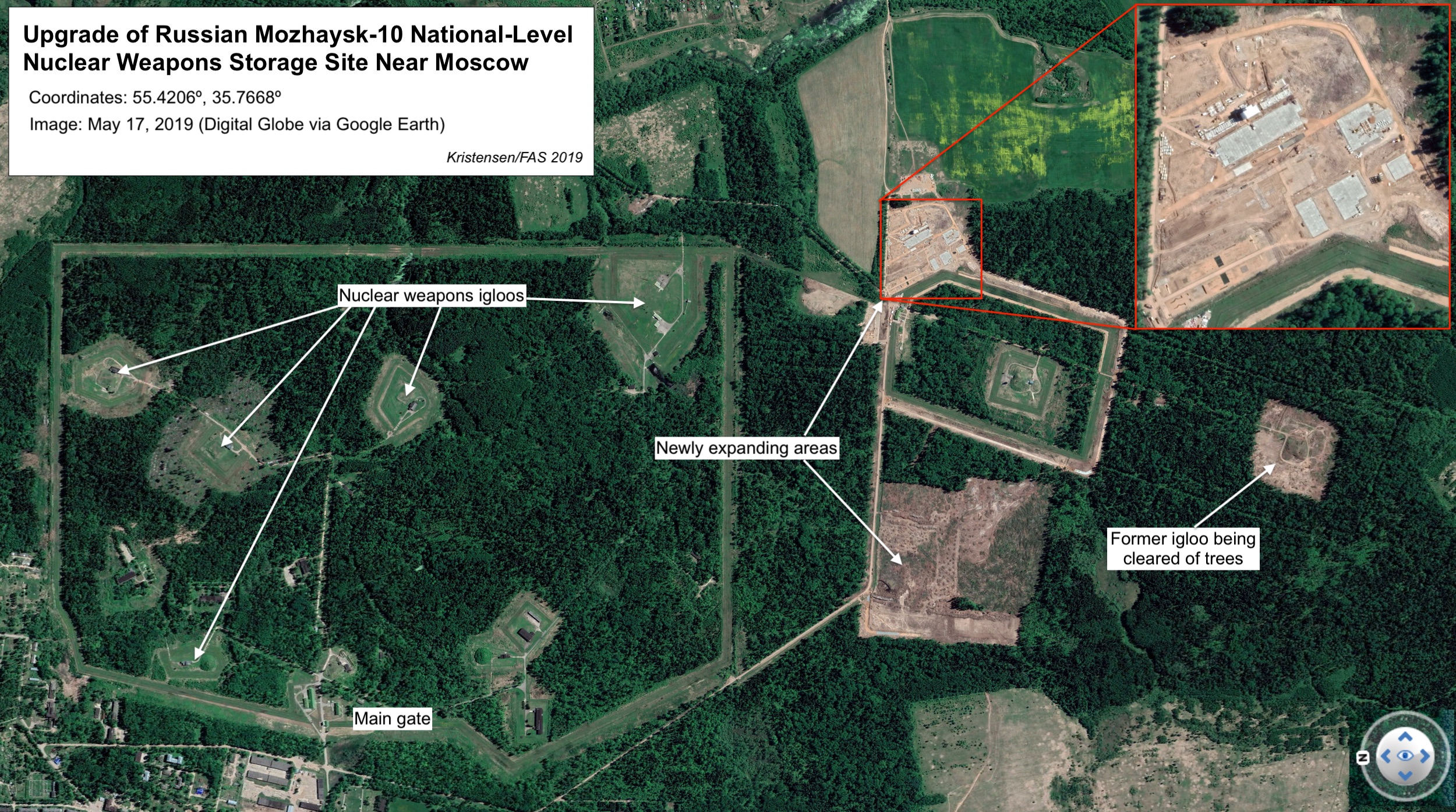

There are also important upgrades underway at the Mozhaysk-10 storage site about 70 miles (114 kilometers) west of Moscow, including addition of new support facilities as well clearing of a previously tree-covered weapons storage igloo. Mozhaysk-10 is one of a dozen national-level nuclear weapons storage site and includes six underground igloos and appears to be expanding (see below). Mozhaysk-10 might be used to store both strategic and tactical nuclear weapons.

The upgrades at the Tver and Mozhaysk-10 sites follow an ongoing upgrade to a nuclear weapons storage site in Kaliningrad that began in 2016 and appears intended to support nuclear-capable forces in the isolated enclave.

Russia is estimated to possess approximately 6,500 nuclear warheads, of which an estimated 4,330 are thought to be available for use by the military. We estimate that Russia has about 1,830 nuclear warheads assigned to non-strategic forces; the Pentagon says the number is “up to 2,000” warheads. The US Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently said it expects to see “a significant projected increase in the number of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons” over the next decade, although some past DIA growth projections have turned out to exaggerated.

In response, the United States has begun to increase the upgrade of its non-strategic nuclear weapons beyond the already-planned B61-12 guided gravity bomb for stealthy F-35 fighter-bombers. New weapons with “tactical” missions include the W76-2 low-yield warhead on the Trident II D5LE SLBM and a new nuclear sea-launched cruise missile. And NATO has been upgrading US nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe.

Russia and the United States refuse to disclose how many tactical nuclear weapons they have or where they are stored, and none of these weapons are limited by arms control agreements.

We will further describe these developments, and much more, in our upcoming Nuclear Notebook on tactical nuclear weapons scheduled for publication in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in September 2019.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

DIA Estimates For Chinese Nuclear Warheads

During a Hudson Institute conference on Russian and Chinese nuclear modernizations, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley said in prepared remarks: “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile…”

This projection is new and significantly above recent public statements by US government agencies. But how reliable is it and how have US agencies performed in the past?

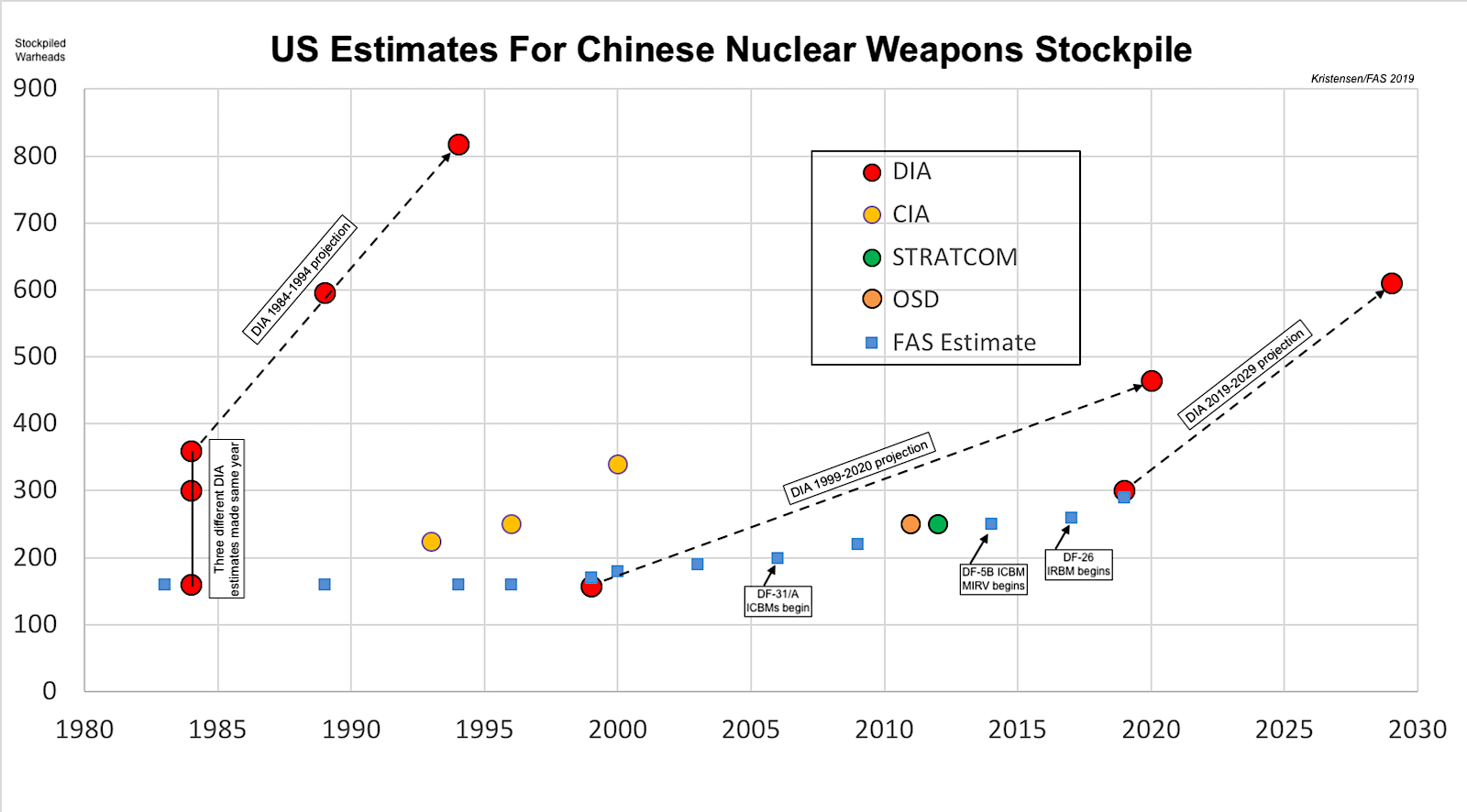

The public record is limited because estimates are normally classified and agencies and officials are reluctant to say too much. But a few examples exist from declassified documents and public statements. These estimates vary considerably – some seemed downright crazy.

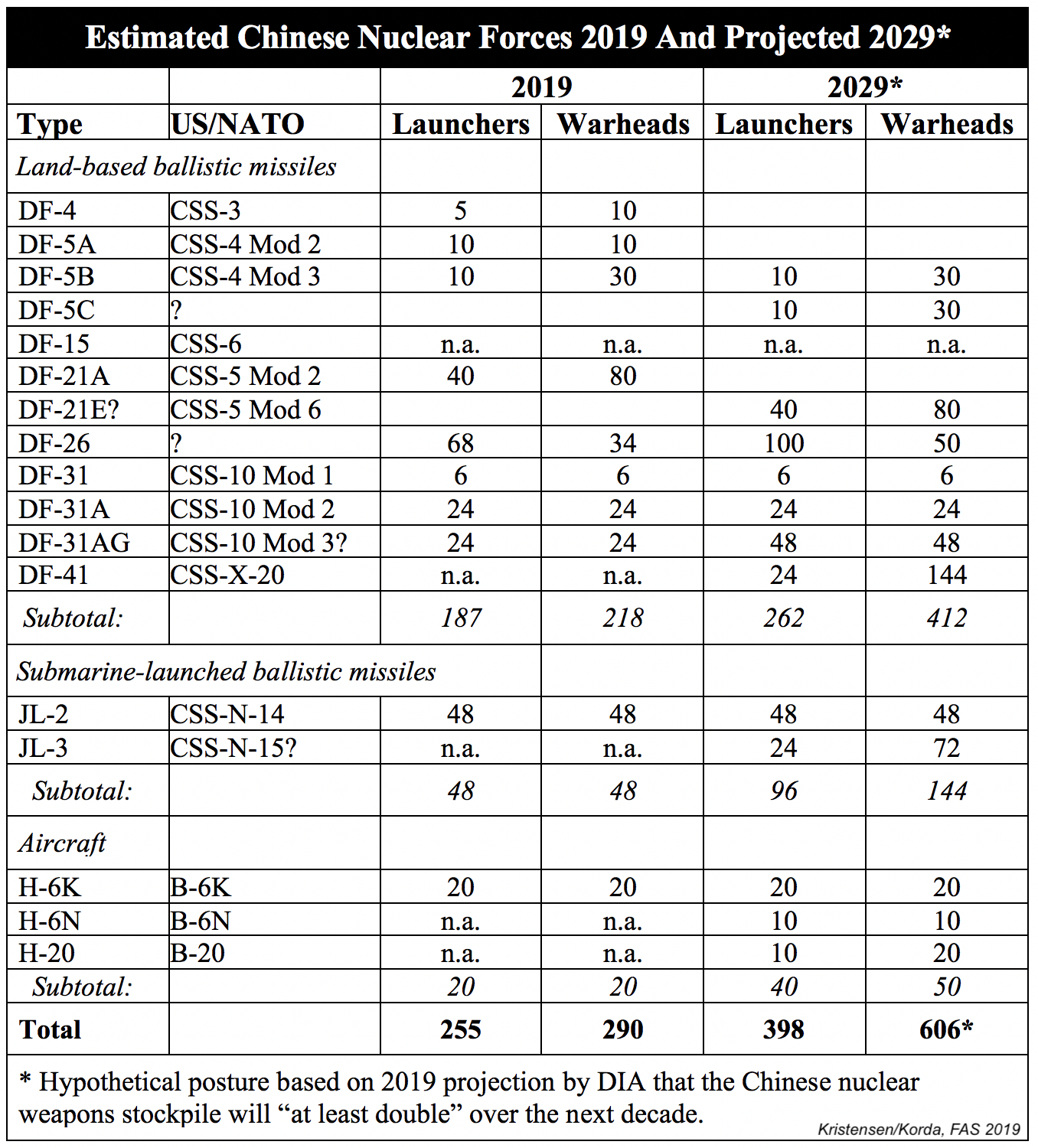

But before analyzing DIA’s projection for the future, let’s examine what the estimated Chinese nuclear stockpile looks like today.

Current Chinese Stockpile Estimate

While warning the Chinese stockpile will “at least double” over the next decade, Lt. Gen. Ashley’s prepared remarks did not say what it is today. But in the follow-up Q/A session, he added: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.

That estimate is close to statements made by DOD and STRATCOM nearly a decade ago. In our forthcoming Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces (scheduled for publication in July 2019), we estimate the Chinese stockpile now includes approximately 290 warheads and is likely to surpass the size of the French nuclear stockpile (~300 warheads) in the near future.

Earlier Chinese Stockpile Estimates

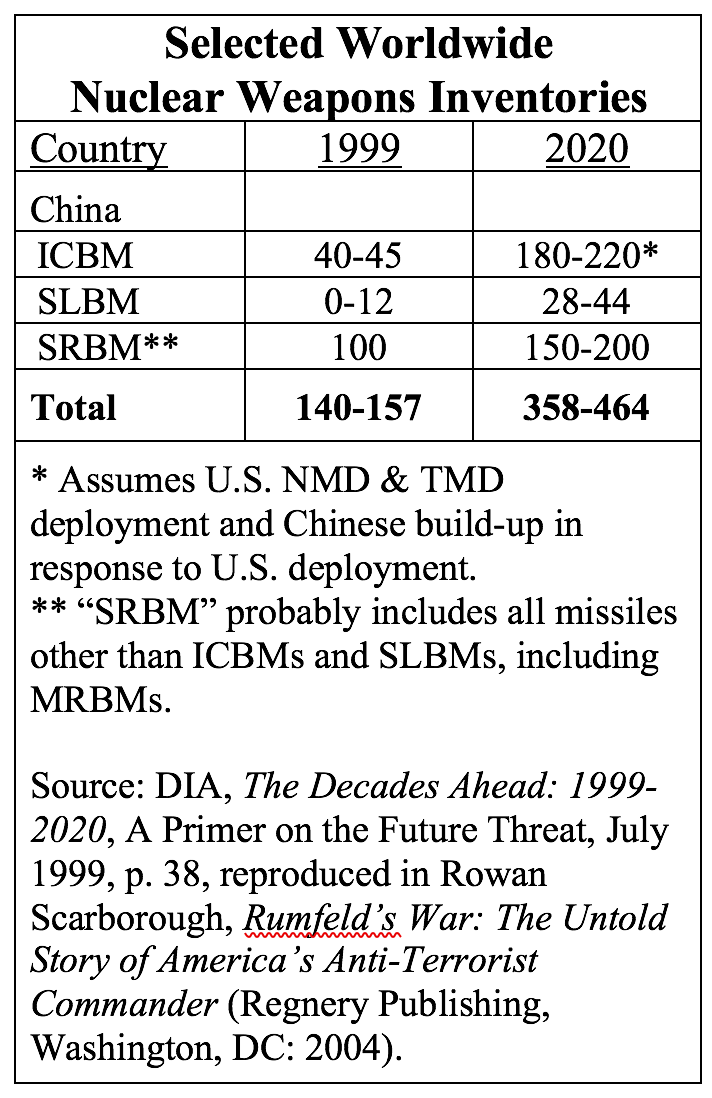

Earlier projections made by US agencies of China’s nuclear stockpile have varied considerably. DIA’s estimates have consistently been higher – even extraordinarily so – than that of other agencies (see graph below). The wide range reflects an enormous uncertainty and lack of solid intelligence, which makes it even more curious why DIA would make them. This record obviously raises questions about DIA’s latest projection.

In April 1980s, for example, DIA published a Defense Estimate Brief with the title: Nuclear Weapons Systems in China. The brief, which was prepared by the China/Far East Division of the Directorate for Estimates and approved by DIA’s deputy assistant director for estimates, projected an astounding growth for China’s nuclear arsenal that included everything from ICBMs, MRBMs, SRBMs, bombs, landmines, and air-to-surface missiles. The brief concluded a curious double estimate of 150-160 warheads in the text and 360 warheads in a table and projected an increase from 596 warheads in 1989 to as many as 818 by 1994. The brief was partially redacted for many years but it has since been possible to reconstruct in its entirety because of inconsistencies in the processing of different FOIA requests.

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

Following an intense debate in 2010 about Senate approval of the New START treaty, then-principle deputy undersecretary of defense for policy James Miller told Congress in 2011: “China is estimated to have only a few hundred nuclear weapons….”

And when false rumors flared up in 2012 that China had hundreds – even thousands – of warheads more than commonly assumed, STRATCOM commander Gen Kehler rebutted the speculations saying: “I do not believe that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than what the intelligence community has been saying,” which is “that the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear warheads.

Since then, China has started to deploy the modified silo-based DF-5B ICBM that is equipped with multiple warheads (MIRV) – part of the response to the US missile defenses that DIA predicted in 1999, and deployed a significant number of dual-capable DF-26 IRBMs. Even so, Ashley’s most recent statement roughly matches the estimates made by Miller and Kehler nearly a decade ago, when he says: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.”

How Could The Chinese Stockpile More Than Double?

Although Ashley predicted a significant expansion of the Chinese stockpile, he did not explain the assumptions that go into that assessment. What would China have to do in order to more than double its stockpile over the next decade?

There are several potential options. China could field a significant number of additional launchers, or deploy significantly more MIRVs on some of its missiles, or – if the MIRV increase is less dramatic – a combination of more launchers and more MIRV. It seems likely to be the latter option.

Additional MIRVing seems to be an important factor. China is developing the road-mobile DF-41 ICBM that is said to be capable of carrying MIRV. It is also developing a third modification of the silo-based DF-5 (DF-5C) that may have additional MIRV capability compared with the current DF-5B. Finally, the next-generational JL-3 SLBM could potentially have MIRV capability, although I have yet to see solid sources saying so. There are many rumors about up to 10 MIRV per DF-41 (even unreliable rumors about MIRV on shorter-range systems), but if China’s decision to MIRV is a response to US missile defenses (which DIA and DOD have stated for years), then it seems more likely that the number of warheads on each missile is low and the extra spaces used for decoys.

China is also expanding its SSBN fleet, which could potentially double in size over the next decade if the production of the next-generation Type-096 gets underway in the early-2020s. And China reportedly has reassigned a nuclear mission to its bombers, is developing a new nuclear-capable bomber, and an air-launched ballistic missile that might have a nuclear option. Assuming a few bomber squadrons would a nuclear capability by the late-2020s, that could help explain DIA’s projection as well. Altogether, that adds up to a hypothetical arsenal that could potentially look like this in order to “at least double” the size of the stockpile:

Conclusions

Whether DIA’s projection comes through of a Chinese stockpile “at least double” the size of the current inventory remains to be seen. Given DIA’s record of worst-case predictions, there are good reasons to be skeptical. It would, at a minimum, be good to hear what the coordinated Intelligence Community assessment is. Does the Director of National Intelligence agree with this projection?

That said, the Chinese leadership has obviously decided that its “minimum deterrent” requires more weapons. To that end, the debate over how much is enough, what the Chinese intentions are, and what the US response should be, are important reminders that the Chinese leadership needs to be more transparent about what its modernization plans are. Lack of basic information from China fuels worst-case assumptions in the United States that can (and will) be used to justify defense programs that increase the threat against China. The recommendation by the Nuclear Posture Review to develop a new nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile is but one example. Both sides have an interest in limiting this action-reaction cycle.

Even if DIA’s projection of a more than doubling of the Chinse stockpile were to happen, that would still not bring the inventory anywhere near the size of the US or Russian stockpiles. They are currently estimated at 4,330 and 3,800 warheads, respectively – even more, if counting retired, but still largely intact, warheads awaiting dismantlement.

But despite the much smaller Chinese arsenal, a significant expansion of the stockpile would likely make US and Russia even more reluctant to reduce their arsenals – a reduction the Chinese government insists is necessary first before it will join a future nuclear arms limitation agreement. So while China’s motivation for increasing its arsenal may be to reduce the vulnerability of its deterrent, it may in fact also cause the United States and Russian to retain larger arsenals than otherwise and even increase their capabilities to threaten China.

Whether DIA’s projection pans out or not, it is an important reminder of the increasingly dynamic nuclear competition that is in full swing between the large nuclear weapons states. The pace and scope of that competition are intensifying in ways that will diminish security and increase risks for all sides. Strengthening deterrence is not always beneficial and even smaller arsenals can have significant effects.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

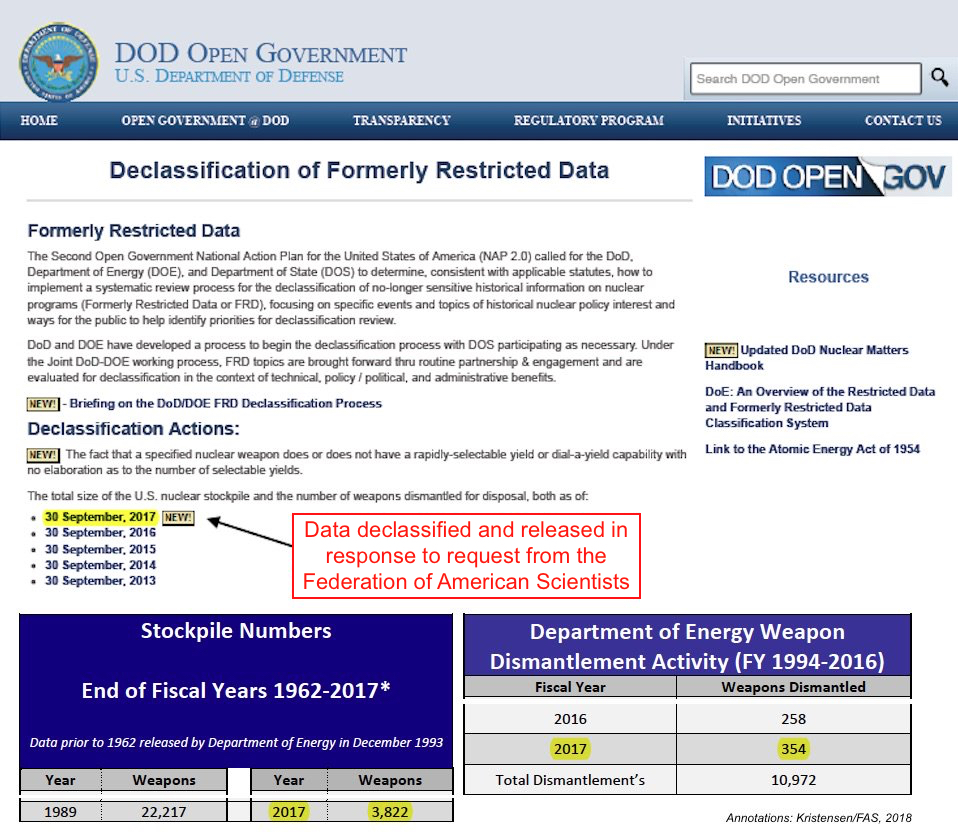

Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose the current number of nuclear weapons in the Defense Department’s nuclear weapons stockpile. The decision, which came as a denial of a request from FAS’s Steven Aftergood for declassification of the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpile number, reverses the U.S. practice from the past nine years and represents an unnecessary and counterproductive reversal of nuclear policy.

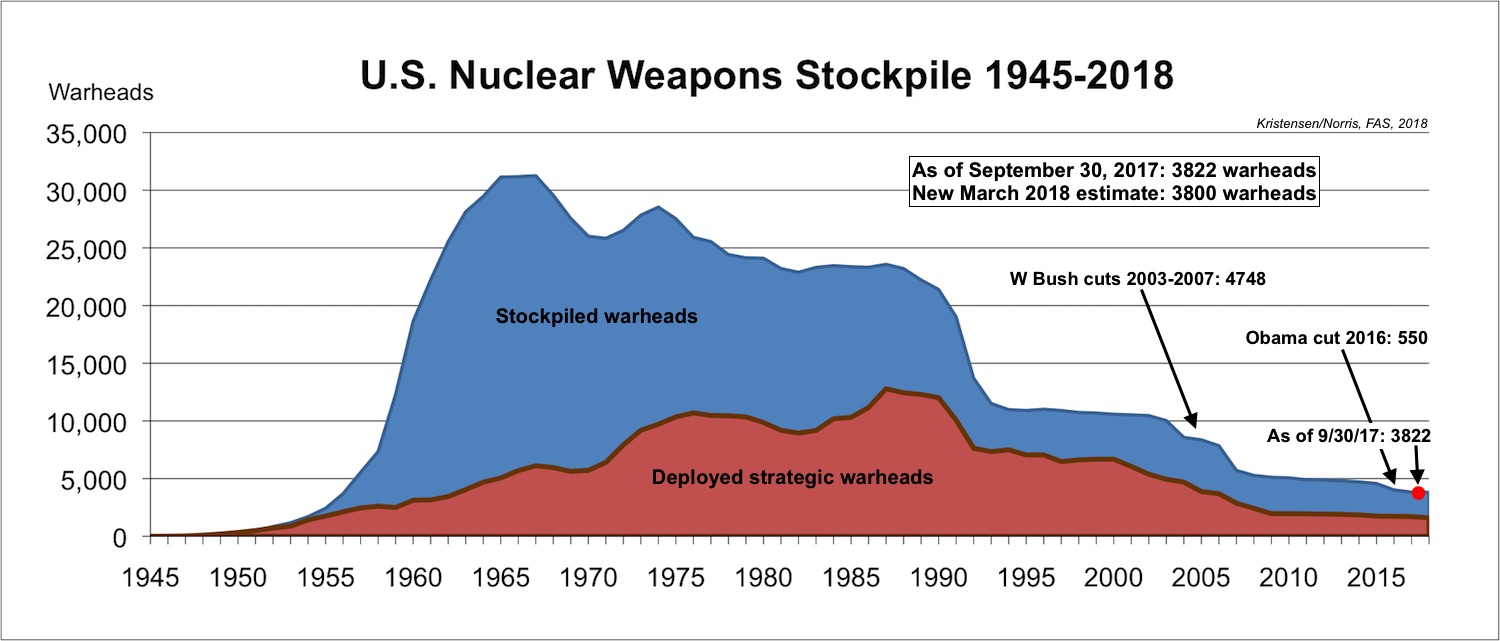

The United States in 2010 for the first time declassified the entire history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size, a decision that has since been used by officials to support U.S. non-proliferation policy by demonstrating U.S. adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), providing transparency about U.S. nuclear weapons policy, counter false rumors about secretly building up its nuclear arsenal, and to encourage other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals.

Importantly, the U.S. also disclosed the number of warheads dismantled each year back to 1994. This disclosure helped document that the United States was not hiding retired weapons but actually dismantling them. In 2014, the United States even declassified the total inventory of retired warheads still awaiting dismantlement at that time: 2,500.

The 2010 release built on previous disclosures, most importantly the Department of Energy’s declassification decisions in 1996, which included – among other issues – a table of nuclear weapons stockpile data with information about stockpile numbers, megatonnage, builds, retirements, and disassemblies between 1945 and 1994. Unfortunately, the web site is poorly maintained and the original page headlined “Declassification of Certain Characteristics of the United States Nuclear Weapon Stockpile” no longer has tables, another page is corrupted, but the raw data is still available here. Clearly, DOE should fix the site.

The decision in 2010 to disclose the size of the stockpile and the dismantlement numbers did not mean the numbers would necessarily be updated each subsequent year. Each year was a separate declassification decision that was announced on the DOD Open Government web site. The most recent decision from 2018 in response to a request from FAS showed the stockpile number as of September 2017: 3,822 stockpiled warheads and 354 dismantled warheads.

The 2017 number was extra good news because it showed the Trump administration, despite bombastic rhetoric from the president, had continued to reduce the size of the stockpile (see my analysis from 2018).

Since 2010, Britain and France have both followed the U.S. example by providing additional information about the size of their arsenals, although they have yet to disclose the entire history of their warhead inventories. Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have not yet provided information about the size or history of their arsenals.

FAS’ Role In Providing Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has been tracking nuclear arsenals for many years, previously in collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The 5,113-warhead stockpile number declassified by the Obama administration in 2010 was only 13 warheads off the FAS/NRDC estimate at the time.

We provide these estimates on our web site, on our Strategic Security Blog, and in publications such as the bi-monthly Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the annual nuclear forces chapter in the SIPRI Yearbook. The work is used extensively by journalists, NGOs, scholars, parliamentarians, and government officials.

With the Pentagon decision to close the books on the stockpile, and the rampant nuclear modernization underway worldwide, the role of FAS and others in documenting the status of nuclear forces will be even more important.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Pentagon’s decision not to disclose the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpiled and dismantled warhead numbers is unnecessary and counterproductive.

The United States or its allies are not suffering or at a disadvantage because the nuclear stockpile numbers are in the public. Indeed, there seems to be no rational national security factor that justifies the decision to reinstate nuclear stockpile secrecy.

The decision walks back nearly a decade of U.S. nuclear weapons transparency policy – in fact, longer if including stockpile transparency initiatives in the late-1990s – and places the United States is the same box as over-secretive nuclear-armed states, several of which are U.S. adversaries.

The decision also puts the United States in an even more disadvantageous position for next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference where the administration will be unable to report progress on meeting its Article VI obligations. Instead, this decision, as well as decisions to withdraw from the INF treaty, start producing new nuclear weapons, and the absence of nuclear arms control negotiations, needlessly open up the United States to criticism from other Parties to the NPT – a treaty the United States needs to protect and strengthen to curtail nuclear proliferation.

The decision also puts U.S. allies like Britain and France in the awkward position of having to reconsider their nuclear transparency policies as well or be seen to be out of sync with their largest military ally at a time of increased East-West hostilities.

With this decision, the Trump administration surrenders any pressure on other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about the size of their nuclear weapon stockpiles. This is curious since the Trump administration had repeatedly complained about secrecy in the Russian and Chinese arsenals. Instead, it now appears to endorse their secrecy.

The decision will undoubtedly fuel suspicion and worst-case mindsets in adversarial countries. Russia will now likely argue that not only has the United States obscured conversion of nuclear launchers under the New START treaty, it has now decided also to keep secret the number of nuclear warheads it has available for them.

Finally, the decision also makes it harder to envision achieving new arms control agreements with Russia and China to curtail their nuclear arsenals. After all, if the United States is not willing to maintain transparency of its warhead inventory, why should they disclose theirs?

It is yet unclear why the decision not to disclose the 2018 stockpile number was made. There are several possibilities:

- Is it because the chaos and incompetence in the Trump administration have enabled hardliners and secrecy zealots to reverse a policy they disagreed with anyway?

- Is it a result of the Nuclear Posture Review’s embrace of Great Power Competition with Cold War-like instincts to increase reliance on nuclear weapons, kill arms control treaties, increase secrecy, and scuttle policies that some say appease adversaries?

- Is it because of a Trump administration mindset opposing anything created by president Obama?

- Or is it because the United States has secretly begun to increase the size of its nuclear stockpile? (I don’t think so; the stockpile appears to have continued to decrease to now at or just below 3,800 warheads.)

The answer may be as simple as “because it can” with no opposition from the White House. Whatever the reason, the decision to reinstate stockpile secrecy caps a startling and rapid transformation of U.S. nuclear policy. Within just a little over two years, the United States under the chaotic and disastrous policies of the Trump administration has gone from promoting nuclear transparency, arms control, and nuclear constraint to increasing nuclear secrecy, abandoning arms control agreements, producing new nuclear weapons, and increasing reliance on such weapons in the name of Great Power Competition.

This is a historic policy reversal by any standard and one that demands the utmost effort on the part of Congress and the 2020 presidential election candidates to prevent the United States from essentially going nuclear rogue but return it to a more constructive nuclear weapons policy.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Despite Obfuscations, New START Data Shows Continued Value Of Treaty

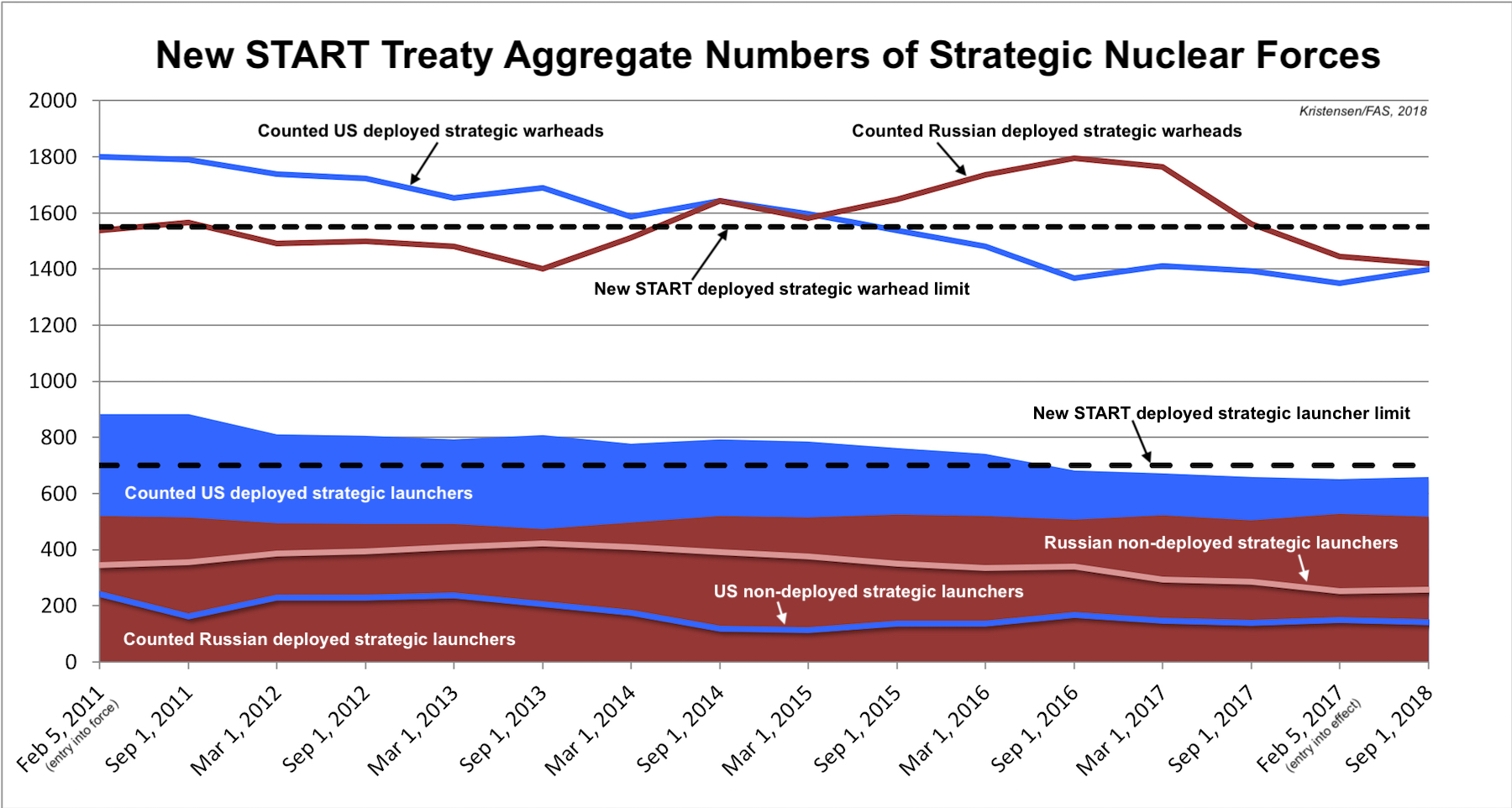

The latest set of New START treaty aggregate data released by the US State Department shows Russia and the United States continue to abide by the limitations of the New START treaty. The data shows that Russia and the United States combined have cut a total of 429 strategic launchers since February 2011, reduced the number of deployed launchers by 223, and reduced the number of warheads attributed to those launchers by 511.

The good news comes despite efforts by officials in Moscow and Washington to create doubts about the value of New START by complaining about lack of irreversibility, weapon systems not covered by the treaty, or other unrelated treaty compliance and behavioral matters. These complaints are part of the ongoing bickering between Russia and the United States and appear intended – they certainly have that effect – to create doubt about the value of extending New START for five years beyond 2021.

Playing politics with New START is irresponsible and counterproductive. While the treaty has facilitated coordinated and verifiable reductions and provides for on-site inspections and a continuous exchange of notifications about strategic offensive nuclear forces, the remaining arsenals are large, undergoing extensive modernizations, and demand continued limits and verification.

By the Numbers

The latest New START data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,180 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,826 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 524 deployed strategic launchers with 1,461 warheads. That’s a slight increase of 7 launchers and 41 warheads compared with September 2018. Russia is currently 176 launchers and 89 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 656 strategic launchers with 1,365 warheads attributed to them, or a slight decrease of 3 launchers and 33 warheads compared with September 2018. The United States is currently 44 launchers and 185 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since September 2018 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,350 for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,850 and 6,460, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Build-Up, What Build-Up

Despite frequent claims by some about a Russian nuclear “buildup,” the New START data does not show such a development. On the contrary, it shows that Russia’s strategic offensive nuclear force level – despite ongoing modernization – is relatively steady. Deteriorating relations have so far not caused Russia (or the United States) to increase strategic force levels or slowed down the reductions required by New START. On the contrary, both sides seem to be continuing to structure their central strategic nuclear forces in accordance with the treaty’s limitations and intentions.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). An ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard is close to initial deployment but would likely supplement the current ICBM force rather than increasing it. The new weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces, nor does it appear to try to close the significant gap the New START data shows exists in the number of strategic launchers – 132 in US favor by the latest count. To put things in perspective, 132 launchers is nearly the equivalent of a US ICBM wing, more than six Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, or twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would be screaming about a disadvantage. Astoundingly, some are still trying to make that case despite the US advantage. Given the launcher asymmetry, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers by 185 since the peak of 421 in 2013.

Russian strategic modernization has been slower than expected with delays and less elaborate base upgrades and is stymied by a weak economy and corruption in government and defense industry. Russia is compensating for this asymmetry by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles, but the New START data indicates that Russia since 2016 has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,’ as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US can’t be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility and the US insists conversions have been carried out as required by the treaty rules that Russia agreed to. Discussions continue in Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 294 onsite inspections (3 each since September) and 17,516 notifications (up about 1,100 since September 2018). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

US SSBN in drydock. Russia says it cannot verify conversion of US strategic launchers. Click on image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: the treaty is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian claims that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

The idea that the INF debacle somehow requires a reevaluation of the value of New START is ridiculous. INF regulates regional land-based missiles whereas New START regulates the core strategic nuclear forces. Why would anyone in either country in their right mind jeopardize limits and verification of strategic forces that threaten the survival of the nation over a disagreement about regional forces that cannot? That seems to be the epidemy of irresponsible behavior.

And the disagreements about conversion of launchers and need to add new intercontinental forces to the treaty can and should be resolved within the BCC.

But it all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, well guess what, that’s what we’re going to get.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

NNSA Plan Shows Nuclear Warhead Cost Increases and Expanded Production

By Hans M. Kristensen

NNSA has published the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan for Fiscal Year 2019, which updates the agency’s work on producing and maintaining the U.S. stockpile of nuclear warheads.

The latest plan follows the broad outlines of last year’s plan but contains important changes.

The new plan shows significant cost increases and warhead production plans that appear to collide with the fiscal realities facing the Nation in the years ahead.

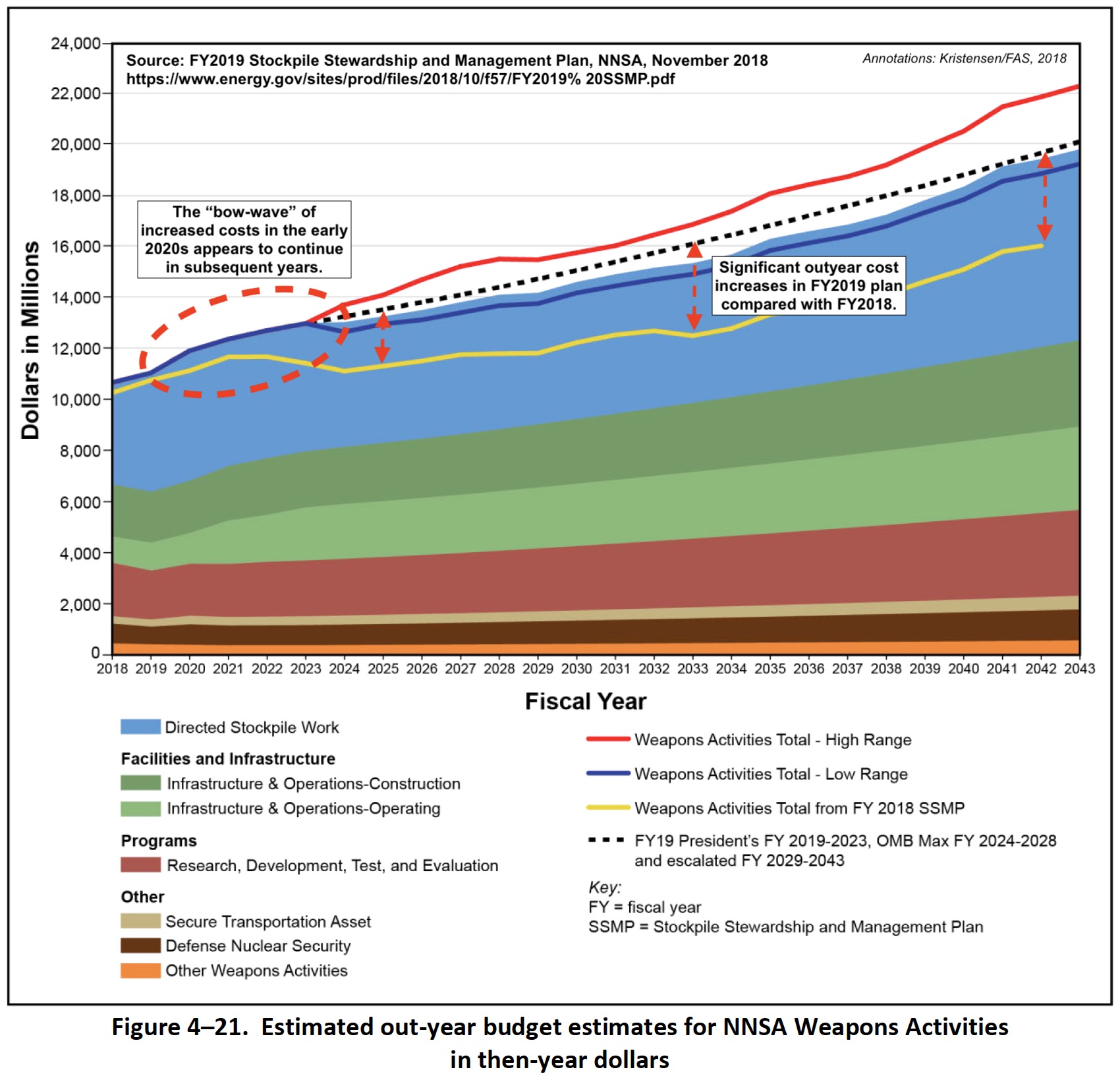

Significant Cost Increases

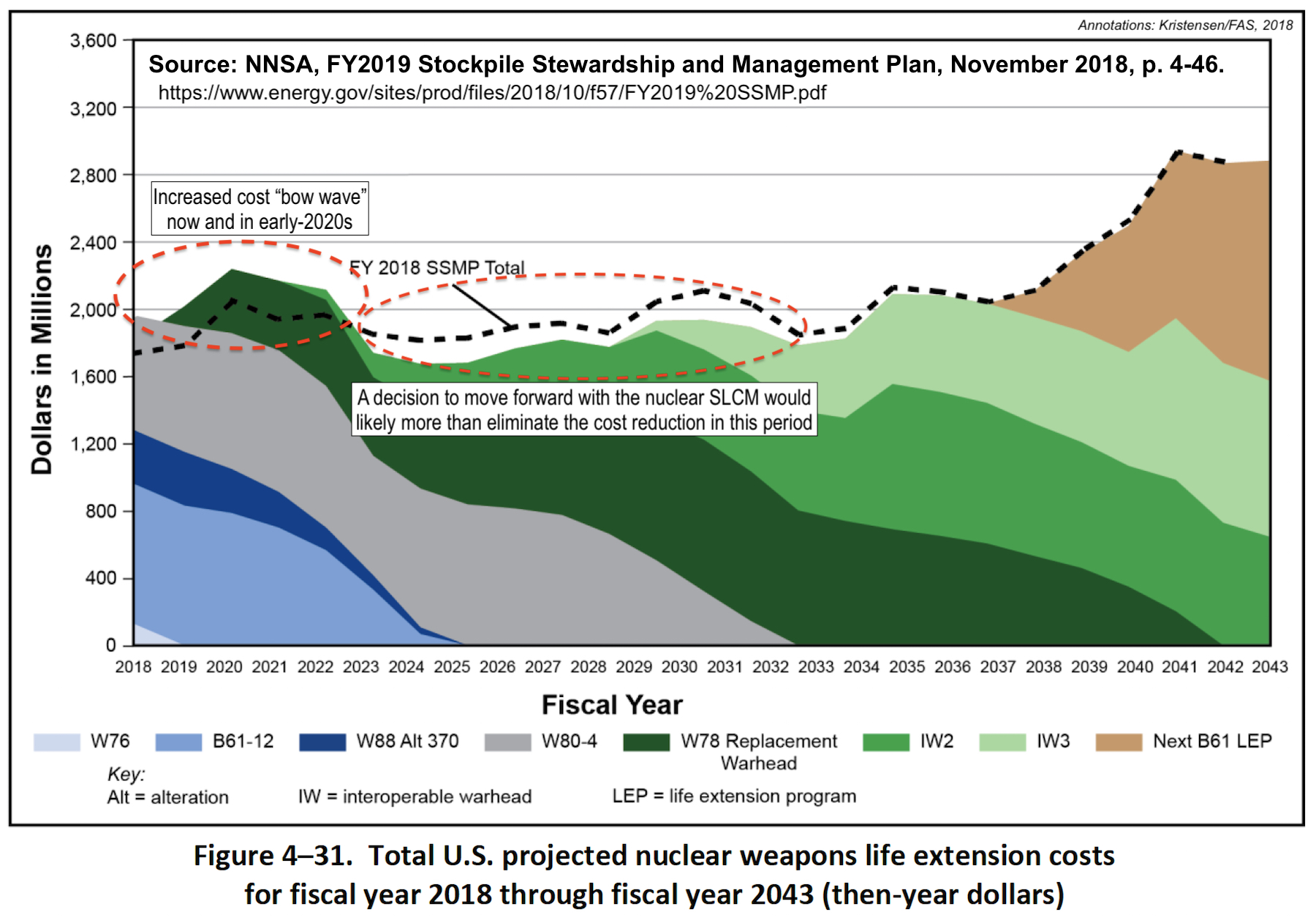

The FY2019 SSMP shows significant increases in out-year cost estimates. The “bow wave” of increased costs in the early-2020s that triggered concerns about affordability appears to have become “a flooding” and continue in subsequent years. The cost-drop the previous SSMP projected for the mid-2020s appears not to be happening. Over the next 25 years, NNSA’s spending on nuclear weapons activities is projected to double (see figure below).

Moreover, the addition of a new SLCM not included in the current plan will further increase costs over the next decade-plus.

FY2019 SSMP shows significant cost increases compared with the FY2018 plan. Click on image to view full size

Part of the greater cost comes from increases in the cost estimates for the individual warhead live-extension programs (LEPs). The W78 LEP, one of the two warheads on the Minuteman III ICBM, is now projected to cost $15.4 billion, up 3.3% from $14.9 billion in the previous plan. The high estimate has even greater increase: up from $18.6 billion to $19.5 billion. Moreover, this cost estimate does not include the incremental cost to get to a 30-pit-per-year plutonium capability by FY 2026 to support this LEP. All of the other warhead programs also have cost increases.

In the near-term, these developments result in immediate cost increases and exacerbate the cost “bow wave” in the first half of the 2020s, which shows an increase of several hundred million dollars each year. Total annual LEP costs are lower in the following decade but that reduction would likely be more than erased by expected cost increases and a decision to move forward with development and production of a SLCM as recommended by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (see figure below).

Cost growth increases fiscal “bow wave” and new weapons would erase future cost reductions. Click on image to view full size

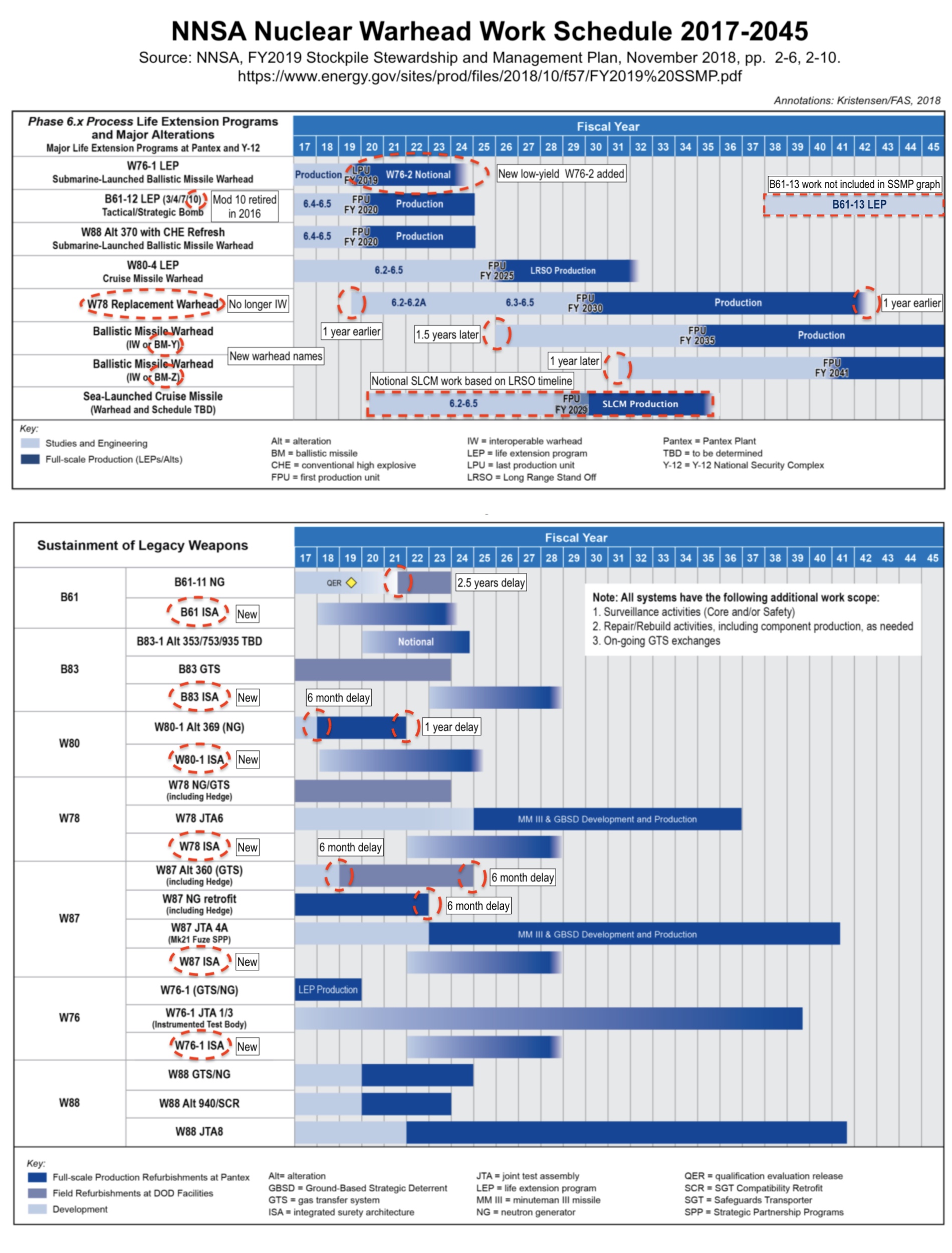

Extensive Warhead Work Planned

The FY2019 SSMP includes several graphs that expand transparency of the nuclear warhead work now and for the next several decades. Most significantly, the SSMP expands information about sustainment work on legacy warheads (those warheads that are already in the stockpile) by breaking it down by work on limited life components (LLCs) such as neutron generators and gas transfer systems, alterations, surety upgrades, and joint test assemblies (JCSs) used for text flights. Overall, this transparency improves overview of the total workload facing the nuclear enterprise.

Interestingly, the so-called “3+2 warhead strategy” that was highlighted in the previous SSMP and congressional hearings as the only way forward is not mentioned in the new plan at all. The intension was to build three interoperable warheads (IWs) for ICBMs and SLBMs and two warheads for aircraft. IW1, which was previously described as a combination of W78 and W88-1, is now simply referred to as the W78 Replacement Program. The two other IWs – the IW2 combining W87 and W88, and the IW3 involving the W76-1 – are now listed with new names: BM-Y and BM-Z.

The SSMP also shows that six warheads will get a new ISA (Integrated Surety Architecture). This involves “improving DOE/NNSA transportation surety by integrating nuclear weapon shipping configurations with physical security elements.” A “matured integrated surety architecture capability to stockpile systems” matured in FY2018 “for further development and integration activities.”

In the graph below, I have combined the SSMP graphs of warhead LEPs and legacy warhead work into one graph and marked changes and omissions compared with the previous SSMP. The new plan includes two new warheads: the low-yield W76-2 and the SLCM.

FY2019 SSMP warhead work sheets show expanded warhead work but do not include several weapons. Click on image to view full size

The LEP section shows W76-2 work stretching out five years from mid-FY2019 (after completion of the current W76-1 LEP) through much of FY2024 (although work might actually be happening one year earlier). The W76-2 is intended to be deployed on SSBNs along with higher-yield W76-1 and W88 warheads. The W76-2 is intended for use in limited “tactical” scenarios in response to for example Russian use of tactical nuclear weapons. It might also serve a role in the expanded nuclear first-use options against “non-nuclear strategic attack” described in the NPR.

The SLCM is mentioned in the SSMP but with no details about the development and production timeline. NNSA says the SLCM “will be a major new addition in the next decade.” In the combined graph I have included a notional SLCM development and production line for illustrative purposes based on the LRSO timeline. It assumes initial startup in FY2020 after completion of an Analysis of Alternatives (AoA).

The SSMP LEP graph does not include the next B61 life extension program (previously called B61-13 in FY2016 SSMP version), which is scheduled to start in 2038. To correct that oversight, I have included it in the graph. This is a major warhead upgrade with cost estimates in the early-2040s ($1.4 billion in 2043) that go beyond that of any other existing or projected LEP program. And based on the cost graph, annual costs estimates would be even greater after 2043. It is yet unclear why the next B61 LEP will be so expensive.

Altogether, the warhead LEP and legacy graphs show a very ambitious workload for the nuclear weapons complex. At some point in the early-2020s, as many as six different warheads LEPs would be in development or production at the same time, in addition to sustainment of legacy warheads in the stockpile.

The Fate of the B83-1 Megaton Bomb

DOD and NNSA in 2013 decided to retire the B83-1 megaton bomb after the B61-12 enters the stockpile in the early 2020s (prior to this decision the B83-1 inventory had already been significantly reduced). As a result, sustainment work on the bomb was canceled. The previous SSMP included a (poor quality) graph that showed the B83-1 (and B61-11) being phased out. Some B83-1s would be retained in the stockpile “until confidence in the B61-12 stockpile is gained.” But the 2018 NPR appeared to signal a delay of that decision, although the language actually seemed very similar: retain the B83-1 “at least until there is sufficient confidence in the B61-12 gravity bomb that will be available in 2020.”

The FY2019 SSMP shows intension to keep B83-1 megaton bomb until 2028. Click on image to view full size

Yet the FY2019 SSMP shows the intension to retain B83-1 longer, at least through 2028. To do that, the plan revives various sustainment programs, including two, possibly three, warhead alterations. Work is also planned on the gas transfer system and integration of a new “integrated surety architecture.”

Although the NPR and SSMP both indicate the B61-12 is the replacement, they leave some uncertainty by talking about retaining the B83-1 “until a suitable replacement is identified.” The two weapons are used to hold at risk hard irregular and underground targets, and the B61-12 has increased accuracy and appears to have some limited earth-penetration capability. But the language used in the NPR and SSMP about the need to identify a “suitable replacement” could potentially indicate that the B61-12 may not be sufficient and that plans for a new weapon are underway.

Implications

The projected cost increases shown in NNSA’s FY2019 SSMP, and plans to add two new nuclear weapons to the arsenal, are likely to significantly strain the capacity of the U.S. nuclear weapons complex. After initially proclaiming its intension to significantly increase the defense budget in the years ahead, the Trump administration instead has announced a reduction of the FY2020 defense budget.

The growing deficit and declining Federal revenues cause by the administration’s tax cuts are likely to further increase the budget pressure in the years ahead. Combined, these developments are likely to create significant risks for the U.S. nuclear weapons modernization program.

Unfortunately, the NPR glosses over and belittles the cost challenge for the nuclear modernization program. Rather than blindly pushing forward with excessively ambitious programs that would likely force emergency adjustments over the next decade in response to budget pressures, it is essential that the administration and Congress proactively modify the modernization programs now to take into account the significant fiscal risks.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Numbers Show Importance of Extending Treaty

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest New START treaty aggregate numbers published by the State Department earlier today show a slight increase in U.S. deployed strategic forces and a slight decrease in Russian deployed strategic forces over the past six months.

The data shows that the United States and Russia as of September 1, 2018 combined deployed a total of 1,176 strategic launchers with 2,818 attributed warheads. In addition, the two countries also had a total of 399 non-deployed launchers for a total of 1,576 strategic launchers.

Combined, the two countries have reduced their deployed strategic forces by 227 launchers and 519 warheads since 2011.

The warheads counted by the New START treaty are only a portion of the total warhead numbers possessed by the two countries. The Russian military stockpile includes an estimated 4,350 warheads while the United States has about 3,800.

The release of the data comes at a particular important time when the United States and Russia are considering whether to extend the New START treaty for another five years beyond 2021 when it expires. The treaty is under attack from defense hawks in Congress and the Trump administration is weighing whether to extend New START in light of Russia’s alleged violation of other agreements.

The data reaffirms that Russia, despite its modernization program, is not increasing its strategic nuclear forces but continue to limit them in compliance with the limitations of New START. In our latest Nuclear Notebook on Russia forces, we estimate that the New START limits recently caused Russia to reduce the number of warheads deployed on several of its strategic missiles.

Deployed Warheads