Produce to Reduce: The Hedge Gamble

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the fourth of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See previous posts: 1, 2, 3.

The FY2012 SSMP repeats the promise made in numerous previous government documents and official statements: construction of new factories with greater warhead production capability might enable retirement of some “hedge” warheads after the “responsive complex” has come online in the early-2020s and thereby reduce the overall size of the stockpile.

Today, the United States has approximately 2,150 operational warheads and another 2,850 in the hedge, for a stockpile total of 5,000. The FY2011 SSMP stated (Annex D, p. 2) that the planned production complex would be able to support a stockpile of 3,000-3,500 warheads, a level 1,500-2,000 warheads below today’s stockpile. However, it did not provide a timetable or strategy for any such reductions.

The FY2012 SSMP does, however, place conditions on further reductions. The report states that the number of nuclear weapons in the nation’s stockpile “may be reduced…if planned LEPs are completed successfully, the future infrastructure of the NNSA enterprise is achieved, and geopolitical stability permits” (emphasis added). The first two items on this list will not be accomplished for at least twenty years, but the plan shows that production of “hedge” warheads will continue even after that.

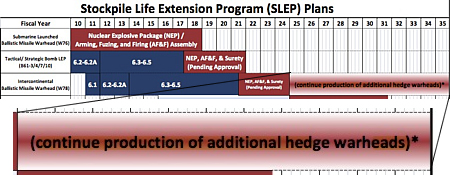

Specifically, the FY2012 SSNP states that this new production capacity is required “regardless of the size of stockpile” and shows that NNSA now plans to produce W78 hedge warheads during the 2021-2024 W78 LEP and even “continue production of additional hedge warheads” through 2035.

| NNSA Plans Production of More Hedge Warheads |

|

| Despite a promise that construction of new warhead production facilities will permit a reduction of the “hedge” of non-deployed warheads in the stockpile, the FY2012 SSMP shows that the new facilities will be used to produce “additional hedge warheads.” The key phrase is enlarged above. Click on image to see the original. |

.

The chart hints that hedge warhead production might also be part of the other warhead LEPs in the NNSA plan. The reason for the additional W78 hedge production in 2025-2035 is not stated. Right now, there are approximately 600 W78s in the stockpile, of which 350 are in the hedge. Are they planning to increase the latter number? Or is that simply continuing production of the “common or adaptable” warhead that would be actually used in the W88 LEP later on? Have other LEPs not been performed on warheads in the hedge, but they will here? The answer is a mystery.

Yet the use of new warhead production facilities to produce additional hedge warheads undermines the administration’s message that the new facilities are needed to allow a reduction of the stockpile. It suggests that even with a new “responsive” warhead production complex, the future stockpile will still include a sizeable hedge of reserve warheads.

Additionally, although the SSMP states that these facilities are needed to “maintain a safe, secure, and reliable arsenal over the long term,” these facilities will not be operational until most of the currently planned Life Extension Programs are either completed or well underway. That makes the plan to use the new facilities to produce additional hedge warheads particularly problematic.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Hydrodynamic Tests: Not to Scale

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the third of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See previous posts: 1, 2, 4.

Since the 1950s, the performance of U.S. nuclear warheads has been successfully validated using a wide range of simulation experiments, such as the compression of fissile material in hydrodynamic tests. And as the stockpile ages “and modernization design options become more complex,” the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) states, “subcritical experiment that include special nuclear material will become more important” (emphasis added). (Special nuclear material refers to highly enriched uranium and plutonium, which are key components of a nuclear weapon.)

The SSMP and other documents describe an interest in a type of hydrodynamic test called a “scaled experiment,” which uses more special nuclear material and more closely resembles actual warhead designs. The public justification is to “improve confidence in predictive capabilities and help validate simulation codes,” but part of the reason is also that those codes will become less reliable if NNSA changes the warhead designs by adding new safety and security features during the Life Extension Programs.

Hydrodynamic Experiments

Every year, the United States conducts “hydrodynamic” experiments designed to mimic the first stages of a nuclear explosion. In tests, conventional high explosives are set off to study the effects of the explosion on specific materials. The term “hydrodynamic” is used because material is compressed and heated with such intensity that it begins to flow and mix like a fluid, and “hydrodynamic equations” are used to describe the behavior of fluids. In one type of hydrodynamic test, researchers build a full-scale primary—the first stage of a modern nuclear weapon—but the plutonium is replaced with a metal that has similar density and weight, but is not fissionable. The device is then fired, revealing information on the design’s behavior from the high-explosive detonation to the beginning of the nuclear chain reaction.

|

| A hydrodynamic test of the W76 warhead design is conducted at the Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in 2005. |

.

Hydrodynamic tests using small amounts of plutonium are conducted underground at the U1a facility at the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS, formerly the Nevada Test Site), while others using surrogate materials occur at the Dual-Axis Radiographic Hydrodynamic Test (DARHT) facility at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, and the Contained Firing Facility at Site 300 of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California. The tests vary greatly in scale and purpose (and there is some overlap) but fall into two overall categories: Integrated Weapons Experiments (IWEs) and Focused Experiments (FEs).

|

| A model of a pin shot hydrodynamic experiment. |

Integrated Weapons Experiments (IWEs) use a rough approximation of an actual War Reserve warhead configuration, minus the special nuclear material. They can address many performance-related questions in one test. IWEs are used to validate modern weapon baseline models (the tested warhead designs) and are the most comprehensive tool for validating computer codes based on past nuclear weapon tests. Some IWEs involve “core punches” that use powerful radiographic imaging equipment to photograph the interior of nuclear weapon or surrogates’ components. Others are “pin shot” experiments that use hundreds of fiber optic, electrical or other types of “pins” emanating from a center to determine features of the plutonium pit or a surrogate pit as it implodes (see image). In 2007, NNSA estimated that it needed to conduct approximately 10 IWEs annually to meet its programmatic needs. However, at the time, part of its program included development of the Reliable Replacement Warhead, which Congress cancelled in 2008.

Focused Experiments (FEs) are smaller and less costly experiments than IWEs and are used to study and isolate issues related to specific components or materials used in nuclear weapons. FEs can be used to help validate computer codes and aid in advanced diagnostic development. In 2007, NNSA estimated that it needed approximately 50 focused experiments annually to meet its programmatic needs.

When IWEs, FEs or small-scale experiments involve use of special nuclear material, usually plutonium, they are called “subcritical” tests. “Subcritical” refers to the fact that the amount of special nuclear material used is not enough to initiate a chain reaction. These tests are conducted at the underground U1a facility in Nevada.

According to the nuclear weapons laboratories, hydrodynamic tests “provide essential data in developing and modifying weapons; such as Life Extension Programs” (emphasis added).

Scaled Experiments

The FY2012 SSMP refers to so-called “scaled experiments” as part of the hydrodynamic testing program. In older documents, NNSA describes scaled experiments as imploding “a primary using Pu-239 that is small enough (scaled) so that it remains sub-critical and core punch radiography can be used to validate modeling its gas cavity shape.” Unfortunately, NNSA doesn’t describe what scaled experiments are in its more recent documents or why they are needed, other than noting they “could improve the predictive capability of numerical calculations by providing data on plutonium behavior under compression by high explosives.” (FY12 SSMP, p. 62)

As far as we can gauge, scaled experiments are subcritical, core-punch, hydrodynamic tests designed to conduct experiments in an implosion geometry that is essentially identical to an actual warhead design, but reduced in size. Rather than a full-scale warhead with the plutonium replaced by other material, a one-third to one-half scale model is built that does use plutonium. At a half-scale size, only one-eighth of the plutonium in an actual warhead is required. The smaller amount of plutonium keeps the explosion from beginning a nuclear chain reaction. Eventually, NNSA wants to build scaled experiments to almost three-quarters (0.7) the size of a full primary.

Some NNSA officials claim to have conducted a scaled experiment in 2005, a claim that is disputed by others, including Administrator Tom D’Agostino. Some recent hydrodynamic experiments have involved scaled technologies. Since 2008, for example, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has carried out several experiments to study the size at which conventional high explosive boosters could ignite the main conventional high explosive that compresses the plutonium. The experiments have used half-scale IWE primaries to better understand how boosting of the warhead yield works as the gas cavity is compressed during implosion.

One interesting note is that the push for scaled experiments is coming from NNSA officials, not the nuclear weapons laboratories. The labs have resisted because they are overburdened by the increasingly ambitious Life Extension Programs. NNSA officials claim that scaled experiments could yield ten times more data points and save money because one large scaled experiment could replace twenty of the smaller hydrodynamic experiments conducted today. Lab scientists maintain that scaled experiments would require major new equipment investments that are not currently planned. At present, U1a in Nevada apparently does not have the diagnostic equipment needed to harvest the additional data generated by scaled experiments.

Little additional information is available about scaled experiments, but more may be on the way, at least in classified settings. Congress has asked the independent technical expert group JASON to conduct a study to assess the benefits of these experiments. And NNSA is also conducting a review to better define what it wants from these (and other) tests. But just last week, the Senate Energy and Water Appropriations Subcommittee barred funding for scaled experiments, stating they “may not be needed for annual assessments of the current stockpile” and “may interfere with achieving the Nuclear Posture Review’s goals and schedule.”

The NNSA was directed by the appropriators to await the results of the JASON study and, if the agency wants to move forward, to “submit a plan explaining the scientific value of scaled experiments for stockpile stewardship and meeting the goals of the Nuclear Posture Review, the costs of developing the capabilities for and conducting scaled experiments, and the impact on other stockpile stewardship activities under constrained budgets.”

That sounds like a reasonable requirement to us.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Ambitious Warhead Life Extension Programs

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the second of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See the other posts: 1, 3, 4.

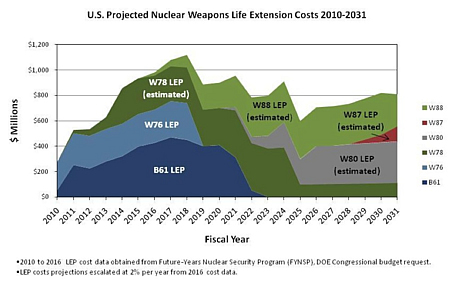

According to the FY2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan (SSMP), from 2011 to 2031, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) plans to spend almost $16 billion on Life Extension Programs (LEPs) to extend the service life and significantly modify almost every warhead in the enduring stockpile. This includes an estimated $3.7 billion on the W88 warhead, $3.9 billion on the B61 bomb, $4.2 billion on the W78 warhead, $1.7 billion on the W76 warhead, and $2.3 billion on the W80-1 warhead.

These figures do not include almost $11 billion in additional NNSA expenses simply to maintain the stockpile, outside of the LEP programs. This brings total spending on nuclear warheads over the next twenty years to $27 billion. These budget figures reflect a significant investment in maintaining and modifying the nuclear stockpile.

|

| The FY2012 SSMP contains a large number of graphs including this one, which adopts the style from the graph FAS and UCS produced in our analysis of the FY2011 plan. |

.

The FY2012 SSMP provides one possible indication that LEP programs are becoming more ambitious and will incorporate more intrusive changes to the warheads. For each weapon type, different variants are designated by a modification, or “Mod” number, as indicated by a hyphen followed by a number at the end of the warhead type, e.g., B61-7 is the “B61 Mod 7.” Only significant changes would result in a new Mod number. For example, the W87 warhead underwent a LEP a decade ago that fixed several structural issues but did not receive a new Mod number. The original warhead designs did not used to have a Mod designation, but the FY12 SSMP lists all the existing warhead types that did not previously have a Mod designation with a “-0” extension. This seems to indicate that all LEPs will now produce warheads with new Mod numbers, apparently in anticipation of significant modifications.

These increasingly intrusive modifications are driven by a stated requirement to improve the safety, security and reliability of the warhead designs. Up to a point, this effort enjoys widespread congressional and White House support—after all, who can be against increasing the safety, security and reliability of nuclear weapons? NNSA and the labs are using these requirements as a primary justification for creating wide-ranging simulation, design, engineering, and production programs that, while smaller in output capacity than those during the Cold War, will be exponentially more technically capable.

The SSMP describes how this capability will provide a “comprehensive science basis underpinning deployment of new safety technologies in the stockpile.” This goal also improves the justification of existing facilities—and those still coming on-line—such as DARHT, NIF, Omega, and the Z machine. NNSA’s goal is to incorporate an enormous array of new safety, security, and use control features in almost the entire stockpile by 2031.

The details of these technologies, their justifications, and costs are largely hidden from public scrutiny. A table listing the safety, security, and reliability features of existing warhead types—and of “an ‘Ideal’ System” (warhead)—is contained in the classified Annex B to the SSMP. (For a list of safety and security features probably installed on U.S. warheads, see here.) While some enhancements may be warranted, the justification for all these new features appears to be based on an open-ended development of new technologies for the incorporation of enhanced surety features into warheads independent of any threat scenario.

This pursuit of a wide range of surety improvements justifies the need for substantial warhead modifications and additional production and simulation capabilities. Yet there must be a point of diminishing returns, where the potential improvements are not justified by the monetary costs or the risks to the reliability of the stockpile.

Indeed, stockpile managers and designers used to warn against modifying warheads, noting that doing so could undermine the confidence in reliably predicting the performance of the weapons without nuclear testing. But warhead modification is now a central goal of the stockpile stewardship management program. Indeed, the goal of the LEPs, the FY2012 SSMP states, it to provide options for “maintaining and modifying the future stockpile” (emphasis added). Modification—not just maintenance—of the enduring stockpile has become a core objective. Interestingly, the SSMP bluntly acknowledges that such modifications of the warheads will reduce confidence in the reliability of the stockpile by changing warheads from the designs that were tested:

“An aggressive ST&E [Science, Technology and Engineering] program is replacing…empirical factors [used to calibrate simulation codes based on underground nuclear tests] with scientifically validated fundamental data and physical models for predicting capability. As the stockpile continues to change due to aging and through the inclusion of modernization features for the enhanced safety and security, the validity of the calibrated simulations decreases, raising the uncertainty and need for predictive capability. Increased computational capability and confidence in the validity of comprehensive science-based theoretical and numerical models will allow assessments of weapons performance in situations that were not directly tested.” (Emphasis added).

However, NNSA’s enthusiasm for extensively modifying all warheads may be going beyond what Congress and the Obama administration as a whole will support. The foundation for such objections is clearly laid out in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, which states explicitly that the United States “will study options for ensuring the safety, security, and reliability of nuclear warheads on a case-by-case basis.” (p. xiv). This seems to contradict NNSA’s pursuit of every available surety feature for every warhead.

In an example of rising concerns, the May 2011 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on the B61 LEP raised red flags about the NNSA’s proposed changes to the bomb. The report expressed concern about the scope of the LEP, noting that it was the first ever that sought to simultaneously refurbish multiple components, enhance safety and surety, and make other design changes. The report noted that some of the proposed new surety features, such as multipoint safety, have never been used in existing stockpile weapons.

Multipoint safety seeks to lessen the chance of an accidental nuclear explosion if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at more than one point nearly simultaneously. The current one-point safety requirement mandates that the risk of a nuclear detonation be no greater than one in a million if the conventional explosive accidentally ignites at one point, which the SSMP acknowledges is an “extraordinarily high reliability requirement.” As the GAO notes, warheads in the current stockpile do not have multi-point safety, and even the NNSA does not consider the technology mature.

Because of these issues, the Senate appropriations committee recently expressed its concern about the B61 LEP. The committee’s report notes that “NNSA plans to incorporate untried technologies and design features to improve the safety and security of the nuclear stockpile” (emphasis added). While expressing support for improved surety, the report states that it “should not come at the expense of long-term weapon reliability.” Due to this concern, the committee reduced funding for the B61 LEP by almost 20% and called for both an independent assessment of the proposed safety and security features and a cost-benefit analysis of them.

One gets the sense that, since Congress stopped the Reliable Replacement Warhead, NNSA has seized on safety and security as the sure-fire cause to allow major warhead modifications and win significant funding. Based on the new Senate findings, NNSA may discover there are limits to how far Congress will go down the modification path and what it will spend, even on the golden ticket of improved safety.

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

See also: FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan | Previous blog in this series

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Plan Conflicts with New Budget Realities

|

| Click on image to download document. |

.

By Nickolas Roth, Hans M. Kristensen and Stephen Young

Note: This is the first of four posts analyzing the FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan, each jointly produced by the Federation of American Scientists and Union of Concerned Scientists. See the other posts here: 2, 3, 4.

A new nuclear weapons plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), which seeks further increases in spending over the next decade for nuclear weapons and for weapons production and simulation facilities, will face real challenges in the new budget environment.

The FY2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP), which was sent to Congress in April, is NNSA’s outline of its near- and long-term plans and associated costs for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and supporting infrastructure. However, with national security spending facing real cuts below FY2011 levels for the next two years at a minimum, either the NNSA must overcome that trend or cut back on its plans.

The FY2012 SSMP is unclassified but has two secret annexes. The new plan updates, with input from Congress, the FY2011 SSMP published last year, and is the first plan to fully incorporate the recommendations of the Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.

Increased Nuclear Weapon Spending

The Obama administration has significantly increased the amount of money the United States spends on nuclear weapons, and had planned further increases before the Budget Control Act of 2011 was passed last month. The FY2011 budget proposed in early 2010 increased NNSA’s spending on Weapons Activities by nearly 10 percent relative to the previous year, and the administration later added another $5.4 billion for the 2011-2015 future years nuclear security program. According to the FY2011 SSMP, NNSA planned to spend about $80 billion from 2011 through 2020—or an average of $8 billion per year. In comparison, nuclear weapons budgets in the last years of the Bush administration were around $6.7 billion annually in inflation-adjusted dollars.

The FY2012 SSMP shows that the NNSA plans additional funding increases, beginning with an additional $4 billion for the 2012-2016 future years nuclear program. The NNSA now plans to spend $88 billion on nuclear weapons and the nuclear weapons complex from 2012 to 2021, for a yearly average of $8.8 billion. This is another 10% increase on top of the FY11 SSMP increase.

However, those budget levels may be less than what is required if NNSA’s plans do not change. In particular, cost estimates for two major facilities—the Uranium Processing Facility (UPF) in Oak Ridge, Tennessee and the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement-Nuclear Facility (CMRR-NF) in Los Alamos, New Mexico—are a cause for concern. The NNSA estimates that the UPF could cost $4.2 billion to $6.5 billion, and the CMRR $3.7 billion to $5.8 billion. The FY12 SSMP hints that the total for both might reach $12 billion, but a footnote in Table 6 on page 67 explains that the ten-year budgets above are based on those facilities coming in at the low end of the current cost estimates. Yet a recent independent estimate by the Army Corps of Engineers concluded that the cost of the UPF alone would be between $6.5 and $7.5 billion, which puts the low end equal to the high end of NNSA’s current estimate.

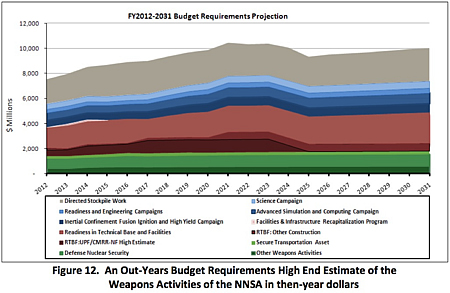

| NNSA Nuclear Weapons Budget Projection 2012-2031 |

|

| Click on image for larger version. Source: U.S. Department of Energy, National Nuclear Security Administration, FY 2012 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan Report to Congress, April 15, 2011, April 2011, p. 68. |

.

The budget requirements projection for FY12-31 above (Figure 12, taken directly from the FY12 SSMP) provides a budget estimate based on the high end of NNSA’s assumptions for all its costs. The chart indicates that the NNSA plans to spend over $120 billion between FY12 and FY24, when the CMRR and UPF are scheduled to be completed. Based on NNSA’s history, using these high end figures is probably a safe assumption, if not an underestimate.

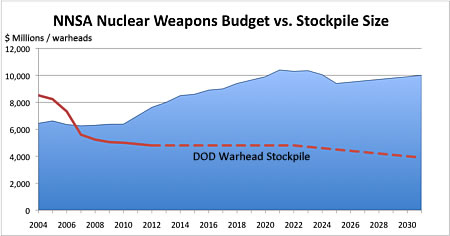

Gone from the FY2012 SSMP is the controversial statement made in the previous SSMP that “the costs to maintain capabilities necessary to support the stockpile are essentially independent of the size of the stockpile.” (Annex D, p. 2.) Yet it is clear from the new plan and other documents that the significant reduction of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile since 2004 has not resulted in any savings in NNSA’s budget, which will continue to increase due to more ambitious warhead modernization plans, cost overruns for the construction of new production facilities, and new simulation and testing facilities. The FY2012 SSMP shows that NNSA would like this trend to continue through the 2020s. See the chart below.

|

| While the size of the nuclear weapons stockpile has declined significantly since 2004, NNSA’s nuclear weapons budget has increased and is projected to grow considerably through the next two decades. Source: NNSA FY12 SSMP; Hans M. Kristensen, Federation of American Scientists. |

.

That desire conflicts with the realities of the Budget Control Act. Rather than a second 10% budget increase as laid out in the FY12 SSMP, the Act calls for a half-percent decrease in national security spending across the board. The House has already passed its version of the key appropriations bill that provides NNSA funding, exacting roughly a 7% cut below the administration’s request for FY2012, leaving a budget less than 3% greater than the FY11 level. The version passed by the Senate appropriations committee was approximately 6% below the request, modestly higher than the House. Because of the Act’s limits, for at least the next several years, NNSA is likely to maintain that level of funding rather than the increased budgets it proposes in the FY12 SSMP.

In short, to live within the new budget priorities that Congress and the administration agreed to in August, NNSA must make significant changes in the timing, scale, and extent of several major projects. Delays, downsizing and perhaps even cancellation of some current priorities seem almost inevitable. The question is: who will make these choices? Will it be the NNSA, the White House, or Congress? And how soon will these decisions be made?

About the authors: Nickolas Roth is Policy Fellow for the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation and a graduate student at the University of Maryland, Hans M. Kristensen is the Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, and Stephen Young is a Senior Analyst at Union of Concerned Scientists.

See also FY2011 Stockpile Stewardship Management Plan analysis

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Rewriting US Presidential Nuclear War Planning Guidance

|

| How will Obama reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the strategic war plan? |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Obama administration has begun a review of the president’s guidance to the military for how they should plan for the use of nuclear weapons. The review, which was first described in public by National Security Advisor Tom Donilon, is the ultimate test of President Obama’s nuclear policy; the rest is just words: to what extent will the new guidance reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the war plan?

Although the administration’s Nuclear Posture Review is widely said to reduce the role of nuclear weapons, it doesn’t actually reduce the role that nuclear weapons have today because all the adversaries in the current strategic nuclear war plan are exempt from the reduction. They are either nuclear weapon states, not members of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, or are in violation of their NPT obligations and have chemical or biological weapons. The new guidance would have to remove some of these adversaries from the war plan to reduce the role, or reduce the role that nuclear weapons are required to play against each of them. There are many ways this could be done:

- Reduce the numer of target categories that are held at risk with nuclear weapons.

- Reduce the damage expectancy to be a achieved against individual targets.

- Reduce the number of adversaries in the plan.

- Reduce the number and types of strike options against each adversary.

- Remove the requirement to plan for prompt launch of nuclear forces.

- Remove any requirement to plan for damage limitation strikes.

- End counterforce nuclear planning.

- End the requirement to maintain standing fully operational strike plans.

Reducing the role of nuclear weapons in the war plan requires direct and continuous presidential attention to avoid that the commitments to reducing the number and role of nuclear weapons are watered down by bureaucrats and cold warriors in the National Security Council, Department of Defense, military commands and Services, as well as former officials who are busy lobbying against a reduction.

To support president Obama’s vision of dramatically reduced nuclear arsenals and a reduced role of nuclear weapons on the way to deep cuts of nuclear weapons and eventually disarmament, we published a study in 2009 that proposed a transition from counterforce planning to what we called a minimal deterrent. A study from 2010 further described the current strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-08 Change 1 from February 1, 2009 – this plan is still in effect). Building on those two studies, we have a new op-ed in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that describes what a new presidential directive could look like: A Presidential Policy Directive for a new nuclear path.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

20th Anniversary of START

July 31st is the 20-year anniversary of signing of the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) between the United States and the Soviet Union. The treaty, also known as START I, marked the beginning of a treaty-based reduction of U.S. and Soviet (later Russian) strategic nuclear forces after the end of the Cold War.

START I required each country to limit its number of accountable strategic delivery vehicles (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers) to no more than 1,600 with no more than 6,000 accountable warheads. The treaty came with a unique on-site inspection regime where inspectors from the two countries would inspect each other’s declared force levels. Thousands of other warheads were not affected and the treaty did not require destruction of a single nuclear warhead. START I entered into effect on December 5th, 2001, and expired on December 4, 2009.

Twenty years after the signing of START I, the United States and Russia are still in the drawdown phase of their strategic nuclear forces: START II followed in 1993, limiting the force levels to 3,500 accountable warheads by 2007 with no multiple warheads on land-based missiles; START II was never ratified by the U.S. Senate but surpassed by the Moscow Treaty in 2002, limiting the number of operationally deployed strategic warheads to 2,200 by 2012; The Moscow Treaty was replaced by the New START treaty signed in 2010, which limits the number of accountable strategic warheads to 1,550 on 700 deployed ballistic missiles and long-range bombers by 2018. Like its predecessors, New START does not limit thousands of non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads and does not require destruction of a single warhead.

The Obama administration has stated that the next treaty must also place limits on non-deployed and non-strategic nuclear warheads.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

|

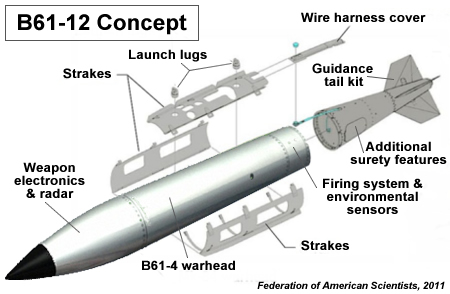

| The US military is planning to replace the tail section of the B61 nuclear bomb with a new guided tail kit to increase the accuracy of the weapon. This will increase the targeting capability of the weapon and allow lower-yield strikes against targets that previously required higher-yield weapons. Image: FAS Illustration |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal.

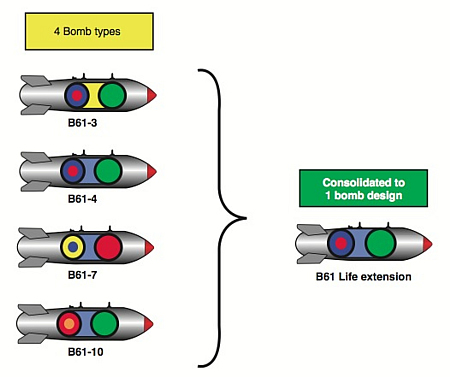

The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy.

As a result, if funded by Congress, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with a significantly enhanced capability to knock out military targets.

Add to that the stealthy capability of the new F-35 aircraft being built to deliver the new weapon, and NATO is up for a significant nuclear upgrade.

The upgrade would also improve the capability of U.S. strategic bombers to destroy targets with lower yield and less radioactive fallout, a scenario that resembles the controversial PLYWD precision low-yield nuclear weapon proposal from the 1990s.

Finally, the B61-12 will mark the end of designated non-strategic nuclear warheads in the U.S. nuclear stockpile, essentially making concern over “disparity” with Russian non-strategic weapons a non-issue.

The Obama administration and Congress should reject plans to increase the accuracy of nuclear weapons and instead focus on maintaining the reliability of existing weapons while reducing their role and numbers.

Increasing Military Capabilities

It is U.S. nuclear policy that nuclear weapons “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.” According to this policy stated in the Obama administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), the B61-12 cannot have new or greater military capabilities compared with the weapons it replaces.

Yet a new report published by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reveals that the new bomb will have new characteristics that will increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

It is important at this point to underscore that the official motivation for the new capabilities does not appear to be improved nuclear targeting against Russia or other potential adversaries. Nonetheless, that will be the effect.

The GAO report describes that the nuclear weapons designers were asked to “consider revisions to the bomb’s military performance requirements” to accommodate both non-strategic and strategic missions. This includes equipping the B61-12 with a new guided tail kit section in an $800 million Air Force program that is “designed to increase accuracy, enabling the military to achieve the same effects as the older bomb, but with lower nuclear yield.”

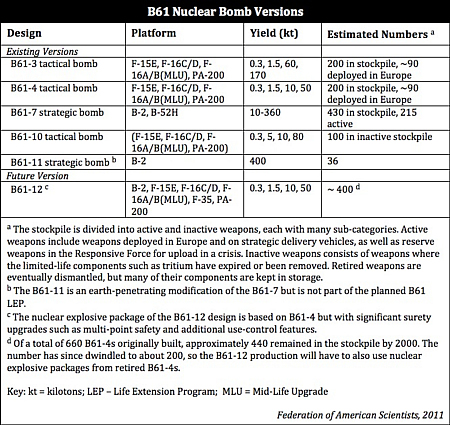

The B61 LEP consolidates four existing B61 types (non-strategic B61-3, B61-4 and B61-10, as well as the strategic B61-7) into one, so the new B61-12 must be able to meet the mission requirements for both the non-strategic and strategic versions. But since the B61-12 will use the nuclear explosive package of the B61-4, which has the lowest yield of the four types (a maximum of 50 kt), increasing the accuracy was added to essentially turn the B61-4 into a B61-7 in terms of targeting capability.

| Consolidating Four Bombs Into One |

|

| This STRATCOM slide used in the GAO report portrays the B61-12 as a mix of components from existing weapons. The message: it’s not a “new” nuclear weapon. But the slide is missing the most important new component: a new guided tail kit section that will increase the weapon’s accuracy. Image: STRATCOM/GAO |

.

The new guided tail kit – the B61 Tail Subassembly (TSA), as it is formally called – will be developed by Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and Boeing for the Air Force and similar to the tail kit used on the conventional Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bomb (Boeing has delivered more than 225,000 kits so far). But the B61-12 would be the first time a guided tail kit has been used to increase the accuracy of a deployed nuclear bomb.

The B61-12 accuracy is secret, but officials tell me it is similar to the tail kit on the JDAM (Joint Direct Attack Munition), which uses a GPS (Global Positioning System)-aided INS (Internal Navigation System). In its most accurate mode it provides the JDAM a circular error probable (CEP) of 5 meters or less during free flight when GPS data is available. If GPS data is denied, the JDAM can achieve a 30-meter CEP or less for free flight times up to 100 seconds with a GPS quality handoff from the aircraft. It is yet unclear if the B61-12 will have GPS, which is not hardened against nuclear effects, but many limited regional scenarios probably wouldn’t have sufficient radiation to interfere with GPS.

Officials explain that the increased accuracy will not violate the LEP policy in the NPR because the B61-12 will not have higher yield than the types it replaces. The B61-12 nuclear explosive package (NEP) will be based on the B61-4, which has the lowest maximum yield of the four types to be consolidated. The B61-7, in contrast, has a maximum yield of 360 kt (see table). But while B61-12 does not increase the yield of the B61-7, its guided tail kit will increase the targeting capability compared with the existing B61-3/4 and -10 versions.

|

| Click on chart to download larger version. |

.

Targeting Implications

Increasing the accuracy of the B61 has important implications for NATO’s nuclear posture and for nuclear targeting in general.

In Europe, the new guided tail kit would increase the targeting capability of the nuclear weapons assigned to NATO by giving them a target kill capability similar to that of the high-yield B61-7, a weapon that is not currently deployed in Europe.

This would broaden the range of targets that can be held at risk, including some capability against underground facilities. In addition, delivery from new stealthy F-35 aircraft will provide additional military advantages such as improved penetration and survivability.

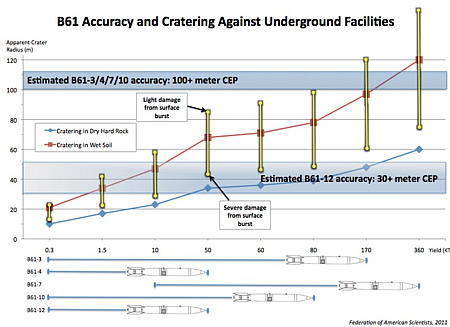

Shock damage to underground structures is related to the apparent (visible) radius of the crater caused by the nuclear explosion. For example, according to the authoritative The Effects of Nuclear Weapons) published by the Department of Defense and Department of Energy in 1977, severe damage to “Relatively small, heavy, well-designed, underground structures” is achieved by the target falling within 1.25 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero (the point of detonation), and light damage is achieved by the target falling within 2.5 apparent crater radii from the Surface Zero. For a yield of 50 kt – the estimated maximum yield of the B61-12, the apparent crater radii vary from 30 meters to 68 meters depending on the ground (see graph below). Therefore an improvement in accuracy from 100-plus meter CEP (the current estimated accuracy of the B61) down to 30-plus meter CEP (assuming INS guidance) improves the kill probability against these targets significantly by achieving a greater likelihood of cratering the target during a bombing run. Put simply, the increased accuracy essentially puts the CEP inside the crater.

.

The U.S. Department of Defense and NATO agreed on the key military characteristics of the B61-12 in April 2010 – the same month the NPR was published and seven months before NATO’s new Strategic Concept was approved. This included the yield options, that the B61-12 will have both midair and ground-burst detonation options, that it will be capable of freefall (but not parachute-retarded) delivery, and the required accuracy when equipped with the new guided tail section and employed by the F-35. STRATCOM, which provides targeting assistance to NATO, subsequently asked for a different yield, which U.S. European Command and SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe) agreed to. Since the NPR prohibits increasing the military capability, STRATCOM’s alternative B61-12 yield cannot be greater than the current maximum yield of the B61-4.

The GAO report states that “neither NATO nor U.S. European Command, in accordance with the NATO Strategic Concept, have prepared standing peacetime nuclear contingency plans or identified targets involving nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added). The “no standing plans” claim is correct because regional nuclear strike planning is no longer done with “standing plans” as during the Cold War. But that doesn’t mean there are no plans at all. Today’s strike planning does not require “standing” plans but relies on new adaptive planning capabilities that can turn out a strike plan within days or weeks.

But the “no identified targets” claim raises an obvious question: If NATO and EUCOM have not “identified targets” for the B61 bombs in Europe, how then can they identify the military characteristics needed for the B61-12 that will replace the bombs in 2018? Obviously, some targets have been identified.

The addition of the tail kit eliminates the need for the existing parachute-retarded laydown option, where a parachute deployed from the rear of the nuclear bomb provides for increased accuracy when employed from an aircraft flying at very low altitude (and allows the pilot (and aircraft) to escape the blast). But a GPS/INS tail kit would also give the B61-12 high accuracy independent of release altitude, weather, and axis of aircraft for much greater survivability.

Reinventing PLYWD: Low-Yield Prevision Nuke

Beyond Europe, the guidance tail kit would also have implications for nuclear targeting in general. Although the B61-12 will not be able to exceed the target kill capability of the maximum yield of the B61-7, the increased accuracy will have an effect on the target kill capability at lower yields. Indeed, the B61-12 concept resembles elements of the Precision Low-Yield Weapon Design (PLYWD) program from the early-1990s when the Air Force studied combining low-yield warhead options with precision guidance to reduce collateral damage from nuclear strikes.

|

| Click on image to download report. |

.

Much of that study remains classified but parts of it were released to me under the Freedom of Information Act (see box). The study concluded that, “The use of precision guidance could permit the Air Force to accomplish some missions as effectively, or more effectively, with low-yield weapons” (emphasis added). Overall, the study found that a precision, low-yield weapon “can be effective against a large fraction of potential targets, can reduce collateral damage on a significant number of targets, is technically feasible, and can provide aircraft standoff (and thus improve survivability).”

PLYWD was rejected by Congress, which banned work on and development of new warheads with a yield of less than five kilotons. Among other things, Congress was concerned that the combination of precision and low-yield to reduce collateral damage would make nuclear weapons appear more useable and risk lowering the nuclear threshold and increase the risk that nuclear weapons would actually be used.

The issue resurfaced in 2001 with proposals to build low-yield nuclear earth penetrators, but the scenarios were shown to be inherently dirty (examples of analysis here, here, and here). Even so, the Bush administration managed to defeat the ban in 2003 in order to explore advanced concepts of nuclear strike options against regional adversaries (see CRS report for background).

The beauty of the B61-12 program is that it avoids a controversial decision to develop a new low-yield nuclear warhead but achieves many of the PLYWD mission goals by combining the existing lower-yield options of the B61 (down to only 0.3 kt) with the increased accuracy provided by the new guidance tail kit to increase targeting capability while reducing collateral damage.

Interestingly, the PLYWD project emerged after EUCOM (now a recipient of the B61-12) pressed for nuclear weapons with lower yields, Los Alamos National Laboratory (the design lab for the B61) proposed a mini-nuke concept, and the Defense Nuclear Agency (now Defense Threat Reduction Agency) began research on “a very low collateral effects nuclear weapons concept.” In fact, both the Military Characteristics (MC) and Stockpile-to-Target Sequence (STS) documents for PLYWD were based on the B61 MC and STS.

In the future, if funded by Congress, the precision B61-12 would allow a B-2, F-35, F-15E, F-16, as well as the next generation long-range bomber, to destroy targets, which previously required high yield blasts, with lower yields and less radioactive fallout.

The Nonproliferation Argument

The relatively lower yield of the B61-4 means that its secondary (CSA, or Canned Sub Assembly) contains less Highly-Enriched Uranium (HEU) that the B61-3, B61-7, and B61-10 versions. Using the B61-4 nuclear explosive package in the B61-12 to replace the three other higher-yield bombs will remove significant quantities of HEU from the deployed force. In other words, so the argument goes, the B61 LEP is a nonproliferation measure intended to reduce the amount of HEU that would be lost if a B61-12 were ever stolen.

This justification is only partly relevant because roughly half of the weapons deployed in Europe already are B61-4 so returning them as B61-12 with the same nuclear explosive package and amount of HEU will not reduce that portion of the deployed force. The HEU-heavy B61-7s are not stored overseas but in the United States (and so are the B61-10s) and most of those are not even at the bomber bases but in central storage facilities.

| B61-7 and JDAM |

|

| The B61 (front, white) is similar in size to the JDAM (back). All high-yield B61-7s are stored in the United States. Image: USAF |

.

Moreover, the total number of B61-12s to be produced is far lower than the combined number of B61 versions in today’s stockpile – perhaps only around 400, down from an estimated 930 weapons.

Far less clear is how the agencies have determined that the risk of theft of a B61 has increased so much after September 2001 that too much HEU is deployed and existing safety and security features are inadequate to protect the weapons. Not least because a National Academy of Sciences task force recently concluded that “there is no comprehensive analytical basis for defining the attack strategies that a malicious, creative, and deliberate adversary might employ or the probabilities associated with them.” As a result, the task force concluded that it “could not identify how to assess the types of attacks that might occur and their associated probabilities.”

That doesn’t seem to have dampened NNSA’s pursuit of exotic safety and security features for all U.S. nuclear warheads in the name of an increased threat. Ironically, in doing so, NNSA is following White House guidance from 2003 that ordered “incorporation of enhanced surety features independent of any threat scenario” (emphasis added). Apparently, increased surety is not needed because of a specific increased threat but because of a policy.

But no one seems to be asking whether the B61 bombs in Europe are being exposed to unnecessary risks because the Air Force continues to scatter them in underground vaults underneath dozens of aircraft shelters at airbases in five European countries with different security standards; the deployment itself may add to the insecurity of the weapons.

The End of U.S. Non-Strategic Warheads

The B61-12 program marks the end of the 60-year old practice of the U.S. military to have designated non-strategic or tactical nuclear warheads in the stockpile. The only other remaining non-strategic warhead in the stockpile, the W80-0 for the nuclear Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), is also being eliminated.

| A “Tactical” Nuclear Weapons Phase-Out |

|

| The B61 LEP eliminates the last designated non-strategic (tactical) nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile, a category of warheads that used to dominate the U.S. arsenal, making the disparity with Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons a non-issue. |

.

With the elimination of the last non-strategic bombs (B61-3, -4 and -10), the B61-4 will be converted to meet the mission requirement of the B61-7; essentially, the non-strategic B61-4 will become a strategic bomb. The B61-12 will be carried by both long-range bombers and short-range fighter-bombers; strategic or non-strategic will be determined by the delivery platform rather than the warhead designation.

Ironically, eliminating non-strategic nuclear warheads and instead using strategic warheads in support of NATO actually meets the language of the Alliance’s new Strategic Concept, which states that “The supreme guarantee of the security of the Allies is provided by the strategic nuclear forces of the Alliance” rather than non-strategic bombs (emphasis added).

Implications and Recommendations

The B61 LEP appears to be much more than a simple life-extension of an existing warhead but an upgrade that will also increase military capabilities to hold targets at risk with less collateral damage.

It is perhaps not surprising that the nuclear laboratories and nuclear warfighters will try to use warhead life-extension programs to increase military capabilities of nuclear weapons. But it is disappointing that the White House and Congress so far have not objected.

The NPR clearly states that, “Life Extension Programs…will not…provide for new military capabilities.” I’m sure we will hear officials argue that the B61 LEP doesn’t provide new military capabilities because it doesn’t increase the warhead yield beyond the maximum of the existing four types.

But this narrow interpretation misses the point. Mixing precision with lower-yield options that reduce collateral damage in nuclear strikes were precisely the scenarios that triggered opposition to PLYWD and mini-nukes proposal in the 1990s. Warplanners and adversaries could see such nuclear weapons as more useable allowing some targets that previously would not have been attacked because of too much collateral damage to be attacked anyway. This could lead to a broadening of the nuclear bomber mission, open new facilities to nuclear targeting, reinvigorate a planning culture that sees nuclear weapons as useable, and potentially lower the nuclear threshold in a conflict.

Such concerns ought to be shared by the Obama administration, which has pledged to reduce the role of nuclear weapons and work to prevent that nuclear weapons are ever used. The pledge to reduce the role of nuclear weapons has received widespread international support but will fall flat if one of the administration’s first acts is to increase the capability of nuclear weapons.

How Russia and NATO allies will react remain to be seen, but increasing NATO’s nuclear capabilities at a time when the United States is trying to engage Russia in talks about limiting non-strategic nuclear weapon seems counterproductive.

These talks could become more complicated because the B61 LEP eliminates non-strategic nuclear warheads from the U.S. stockpile and instead leaves the B61-12 to cover both strategic and non-strategic scenarios. That will further blur the line between strategic and non-strategic weapons and make it a challenge to meet the U.S. Senate’s requirement “to initiate…negotiations with the Russian Federation on an agreement to address the disparity between the non-strategic (tactical) nuclear weapons stockpiles of the Russian federation and of the United States and to secure and reduce tactical nuclear weapons in a verifiable manner.” After the B61 LEP the United States will not have any non-strategic nuclear warheads to negotiate with, essentially making the “disparity” a non-issue.

NATO declared in its Strategic Concept from November 2010 that the alliance “will seek to create the conditions for further reductions in the future” of the number and reliance on nuclear weapons. Increasing the capability of NATO’s nuclear posture appears to contradict that pledge and could lead to increased opposition to continued deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe.

At the very least, the administration and Congress need to define and publicly clarify what constitutes “new capabilities.” More than $213 billion are planned for nuclear modernizations in the next decade; it’s hard to believe that there will be no “new capabilities” slipping through in that work. In fact, current plans for warhead life-extension programs indicate that the nuclear establishment intends to take full advantage of the uncertainly by increasing the targeting capabilities of the nuclear weapons: it is already happening with the W76 LEP, which is being deployed on submarines with increased targeting capability; it is scheduled to happen with the B61 LEP; and it appears to be planned for the W78 LEP as well.

The logic seems to be: “We’re reducing the number of weapons so of course the remaining ones have to be able to cover more scenarios.” In other words, the price for arms control is increased military capabilities.

The administration should also direct that the portion of the B61-12s that are earmarked for deployment in Europe be deployed without the new guidance tail kit but retain the accuracy of the exiting weapons currently deployed in Europe. Otherwise the B61-12 should not be deployed in Europe.

Finally, the administration’s ongoing nuclear targeting review should narrow the role of nuclear weapons to prevent that numerical reductions become a justification for increasing the capabilities of the remaining weapons. The new guidance must depart from the “warfighting” mentality that still colors nuclear war planning and is so vividly illustrated by the precision low-yield options offered by the B61-12.

NOTE: This blog is also available in PDF format as an Issue Brief.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The B61 Life-Extension Program: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Strikes

A modified U.S. nuclear bomb currently under design will have improved military capabilities compared with older weapons and increase the targeting capability of NATO’s nuclear arsenal. The B61-12, the product of a planned 30-year life extension and consolidation of four existing versions of the B61 into one, will be equipped with a new guidance system to increase its accuracy. As a result, the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs currently deployed in five European countries will return to Europe as a life-extended version in 2018 with an enhanced capability targets.

New START Aggregate Numbers Released: First Round Slim Picking

|

| You won’t be able to count SS-18s in the New START aggregate date. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russia and the United States have released the first Fact Sheet with aggregate numbers for the strategic offensive nuclear forces counted under the New START treaty.

It shows that Russia has already dropped below the New START ceiling of 1,550 accountable deployed warheads and the United States is close behind, seven years before the treaty is scheduled to enter into effect (it makes you wonder what all the ratification delay was about).

But compared with the extensive aggregate numbers that were released during the previous START treaty, the new Fact Sheet is slim picking: just six numbers.

Unless the two countries agree to release more information in the months ahead, this could mark a significant step back in nuclear transparency.

The Aggregate Numbers

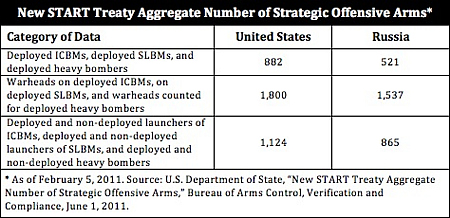

The Fact Sheet includes six numbers for three categories of counted U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear arms under the treaty:

United States

The table lists 882 deployed delivery vehicles. Since we know this includes 450 ICBMs and 288 SLBMs, the number of bombers counted appears to be 144. Less than half of those (about 60 B-2 and B-52H) are actually assigned nuclear missions, the balance being “phantom” bombers (B-52H and B-1B) that have some equipment installed that makes them accountable under the treaty.

The 1,800 deployed warheads include approximately 500 on 450 ICBMs and approximately 1,152 on 288 SLBMs. The remaining 148 warheads constitute the remaining “fake” count of one weapon per deployed bomber. That means our estimate was only four warheads off (!).

If subtracting the 144 “fake” bomber weapons, the actual number of U.S. deployed strategic warheads on ICBMs and SLBMs is 1,656, only about 100 warheads from the New START ceiling. The actual number of bomber weapons present at the bases, we estimate, is 300 or less. They are not deployed on the bombers, so they are not counted by New START, but they were counted by the United States during the now-expired Moscow Treaty (SORT). So the real number of operationally available warheads may be around 1,950, which is what we estimated in March.

Another 2,290 non-deployed strategic warheads are in reserve and there are about 760 non-strategic warheads for a total stockpile of approximately 5,000 warheads. Another 3,500 or so warheads are awaiting dismantlement for a total inventory of roughly 8,500 warheads.

The total number of 1,124 deployed and non-deployed missiles and bombers shows that there are 242 non-deployed missiles and bombers. That number includes 48 SLBMs for two non-deployed SSBNs and additional test SLBMs, reserve Minuteman ICBMs and 50 retired Peacekeeper ICBMs, and heavy bombers in overhaul.

The United States has declassified considerable information in the past and hopefully will continue to do so in the future, so the limited aggregate numbers has fewer implications than in the case of Russia. But it would help to see a breakdown of bombers and non-deployed missiles.

Russian Federation

The effect of the limited aggregate numbers has a much more significant effect on the ability to understand the Russian nuclear posture. Most important is the absence of a breakdown of strategic delivery vehicles.

The number of deployed delivery vehicles is listed as 521. The final aggregate number from the expired START treaty was 630 as of July 1, 2009. Not surprisingly, a reduction because the SS-18, SS-19, SS-25 and SS-N-18 are being phased out. But the limited aggregate information makes it impossible to see which missiles have been reduced.

In our latest estimate we counted 534 deployed delivery vehicles, or 13 more than the New START data. The difference may reflect that some SLBMs on Delta IV SSBNs were not fully deployed and a slightly different composition of the ICBM force.

The Fact Sheet lists 1,537 deployed warheads, which actually translates into 1,461 warheads because 76 of them are “fake” bomber weapons. That means Russia has already met the warhead limit of New START – seven years before the treaty enters into effect.

Despite the uncertainty about the force structure, our latest estimate of Russian strategic nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs was only 122 warheads off.

The aggregate deployed warhead number also more or less confirms long-held suspicion that Russia normally loads its missiles with their maximum capacity of warheads, in contrast to the United States practice of loading only a portion of the warheads.

That means that Russia only has comparatively few strategic warheads in reserve (essentially all bomber weapons). New START does not count such warheads, nor does it count 3,700-5,400 non-strategic warheads in storage or some 3,200 warheads awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of up to 11,000 warheads.

The total aggregate number for deployed and non-deployed delivery vehicles is listed as 865. That shows us that Russia has 344 non-deployed delivery vehicles, a considerable amount given the relatively limited size of their deployed force of 521 delivery vehicles. Since Russia has a limited number of bombers more or less exclusively committed to the nuclear mission, the non-deployed delivery vehicles mainly include retired ICBMs. It would be good to hear whether they will be destroyed or stored.

Additional releases

Each of the two parties to New START can decide under the treaty to release additional information to the public about their own nuclear postures. Given the limited information in the aggregate numbers Fact Sheet, it would be a huge disappoint if they don’t.

I understand from the U.S. government that it is planning to do so later this year, and it is important that Russia considers doing so as well.

Under the terms of the treaty the two parties may also agree to jointly release additional information.

Implications

At a first glance the aggregate numbers released by the United States and Russia under the New START treaty is a huge disappointment. It represents a step back in nuclear transparency compared with the standard set by the same two countries under the previous START treaty.

Earlier last month, Ambassador Linton Brooks, Ambassador Jack Matlock and Secretary William Perry joined FAS in calling on the United States and Russia to continue to meet this standard.

We have yet to receive a formal reply but the aggregate numbers Fact Sheet is a reply of sort.

It ought to be a natural that international nuclear transparency is increased with each new treaty, that previously unaccounted categories are brought under accounting, and that uncertainties are cleared up. Moreover, international nuclear transparency means transparency not just for the two parties to the treaty but for the international community as well.

The aggregate numbers Fact Sheet includes the total number of warheads actually deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, an important improvement from the previous treaty. But the breakdown of number of delivery vehicles and deployment locations has moved into the black.

As mentioned above, the United States and Russia have the right under the treaty – individually or jointly – to release additional information about their nuclear force structures.

It is essential that they do so and continue to do so with each future aggregate numbers Fact Sheet release. Otherwise, the uncertainty about their forces could accumulate and undermine predictability and transparency for other nuclear powers. That, in turn, could make it harder to get those countries involved in nuclear arms control in the future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Letter Urges Release of New START Data

|

| Ambassador Brooks, Secretary Perry and Ambassador Matlock join FAS in call for continuing nuclear transparency under New START treaty |

.By Hans M. Kristensen,

Three former U.S. officials have joined FAS in urging the United States and Russia to continue to declassify the same degree of information about their strategic nuclear forces under the New START treaty as they did during the now-expired START treaty.

The three former officials are: Linton Brooks, former chief U.S. START negotiator and administrator of the National Nuclear Security Administration, Jack Matlock, former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union and Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan for national security affairs, and William Perry, former U.S. Secretary of Defense.

At issue is whether the United States and Russia will continue under the New START treaty to release to the public detailed lists – known as aggregate data – of their strategic nuclear forces with the same degree of transparency as they used to do under the now-expired START treaty. There has been concern that the two countries might reduce the information to only include numbers of delivery systems but withhold information about warhead numbers and locations.

In a joint letter, the three former officials joined FAS President Charles Ferguson and myself in urging the United States and Russia to “continue under the New START treaty the practice from the expired START treaty of releasing to the public aggregate numbers of delivery vehicles and warheads and locations.” This practice contributed greatly to international nuclear transparency, predictability, reassurance, and helped counter rumors and distrust, the letter concludes.

Both governments have stated their intention to seek to broaden the nuclear arms control process in the future to include other nuclear weapon states and the letter warns that achieving this will be a lot harder if the two largest nuclear weapon states were to decide to decrease transparency of their nuclear forces under New START.

“Any decrease in public release of information compared with START would be a step back.”

The letter was sent to Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, and Sergey Kislyak, the Ambassador of the Russian Federation to the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Defense Science Board: Air Force Nuclear Management Needs Improvements

|

| The Defense Science Board recommends reducing the number of inspections of nuclear bomber and missile units. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s “independent” Defense Science Board Permanent Task Force on Nuclear Weapons Surety has completed a review of the Air Force’s efforts to improve the safety and proficiency of its nuclear bomber and missile units. The report comes three and a half years after the notorious incident at Minot Air Base where six nuclear cruise missiles were mistakenly loaded onto a B-52H bomber and flown across the United States.

The report, Independent Assessment of the Air Force Nuclear Enterprise, finds progress has been made but also identifies some serious issues that still need to be fixed. Some of them are surprising.

Inspections Gone Amok

The most important finding is probably that the nuclear inspection system following Minot has gone amok and in some cases become counterproductive. The number and scope of inspections were increased in response to the incident, but now they have become so frequent and widely applied that nuclear units have neither the time nor resources to correct the deficiencies that are actually identified. Instead the inspection system needs to be limited and focused on where the problems are.

It is natural that leadership will want to demonstrate rigorous efforts to correct deficiencies after a serious incident like Minot by beefing up inspections and exercises as proof that they’re taking things seriously. But this has resulted in a continuous and across-the-board level of inspections and exercise activity that part of the Air Force leadership sees as needed “until a zero-defect culture can be reestablished.”

In reality there has probably never been a zero-defect situation and, when overdone, the high level of inspections and exercises lead to an unrealistic zero-risk mindset. In other words, the leadership needs to cultivate a realistic inspection culture that is focused on detecting and correcting defects rather than expecting to eliminate them.

Over-focus on zero-defect can create distrust in the lower ranks that the leadership doesn’t trust them to perform professionally. This is, the DSB report bluntly concludes, “creating a leadership mindset where satisfying a Nuclear Surety Inspection team, for example, can supplant, or at least compete with, focus on readiness to perform the assigned nuclear mission.”

And nuclear inspection excess combined with multiple over-laying agencies and organizations can create bizarre situations such as in the case of inspections of Munitions Support Squadrons (MUNSSs) in Europe where it is not uncommon to have 80-90 inspectors examining a unit with a total manning of less than 150 personnel.

The report recommends returning gradually to the normal 18-month inspection scheduled used before the Minot incident, and states that additional inspections should occur “only to address unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends.” In other words: no additional inspections unless a problem has already been detected.

For the Air Force’s nuclear deployment in Europe, the report recommends that follow‐up re‐inspections and special inspections of air bases and other nuclear units be discontinued unless unsatisfactory ratings or significant negative trends have been identified. For all other discrepancies the wing commander or the MUNSS commander should be accountable for closing out the discrepancies in communication with the appropriate inspection agency. Serious security issues were found at European bases in 2008 and evidently had still not been fixed in 2010.

The DSB report does not, however, describe in detail how or to what extent the nuclear proficiency level has evolved in the nuclear units as a result of the increased inspections and oversight established after 2007. It concludes that a culture of special attention to nuclear issues has been reestablished at the operational level, but not fully at the supporting system of the Air Force nuclear enterprise. It would have been interesting to see how that has affected the actual nuclear inspection grades of the individual units.

Resources Still Lacking

While the Air Force leadership has spoken at length about the importance of improving the nuclear proficiency and safety, the report concludes that the leadership has not yet put the money where its mouth is in terms of prioritizing budgets, upgrades of support equipment, directives and technical orders, and tailoring personnel policies to specific nuclear missions. There is still a degree of business-as-usual in planning and acquisition.

For example, the report identifies that 40-plus year munitions hoists are not being replaced, that engineering requests for reentry vehicles has skyrocketed from 100 in 2007 to 1,100 in 2010, and that repairs of nuclear Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMTs) at bases in Europe has been delayed by missing spare parts. There are currently 150-200 U.S. nuclear bombs scattered across six bases in five European countries. The 14 WMTs are scheduled for replacement with the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS) in 2014.

Reliability But No Trust

The report concludes that the Air Force’s Personal Reliability Program (PRP), intended to ensure that only qualified people are allowed access to nuclear weapons, has not improved and in some cases increasingly suffers from defects. One problem identified is a continuing escalation of the pursuit of absolute assurance of personal reliability, which the report concludes created “important dysfunctional aspects in the program” where threat of suspension and decertification has produced an environment of distrust. People that have been selected are not sufficiently trustworthy to live an acceptable daily life and must continuously reestablish their credibility. According to the report:

“Even the possibility of Potentially Disqualifying Information (PDI) leads to temporary decertification until it is established that there has been no compromise of reliability. Based on this fundamentally flawed assumption, the PRP repeatedly reexamines the history of each individual.”

“As one example of the consequences of this attitude, personnel are automatically suspended from PRP duties when referred by Air Force medical authorities to off‐base medical treatment regardless of the nature of the referral. The individual must then report to base medical authorities to be reinstated.”

Personnel issues also continue to plague the nuclear wings and MUNSS units in Europe, where the DSB report describes personnel management has created “a flow of people who have no nuclear experience into the key DCA wing in Europe” [i.e. 31st FW at Aviano] and the MUNSS sites at national bases.

As a result, the DSB report recommends that Air Force PRP-based restrictions and monitoring standards be reduced to match those required by DOD.

Command Structure Readjustment

The DBS report also recommends that the nuclear command structure that was set up after the Minot incident be readjusted to that all base-level operations and logistics functions be assigned to the strategic missile and bomb wings reporting through the numbered air forces to Air Force Global Strike Command.

One effect of this command readjustment is the transfer of all munitions squadrons responsible for nuclear mission support from Air Force Material Command to the Air Force Global Strike Command within the next 12 months, recently described by the Air Force.

Download Defense Science Board report

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

10 NATO Countries Want More Transparency for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

|

| Ten NATO countries recommend increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons, including numbers and locations at military facilities such as Incirlik Air Base in Turkey. Neither NATO nor Russia currently disclose such information. |

.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Four NATO countries supported by six others have proposed a series of steps that NATO and Russia should take to increase transparency of U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The steps are included in a so-called “non-paper” that Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Poland jointly submitted at the NATO Foreign Affairs Minister meeting in Berlin on 14 April.

Six other NATO allies – Belgium, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Iceland, Luxemburg and Slovenia – also supported the paper.

The four-plus-six group recommend that NATO and Russia:

- Use the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) as the primary framework for transparency and confidence-building efforts concerning tactical nuclear weapons in Europe.

- Exchange information about U.S. and Russian tactical nuclear weapons, including numbers, locations, operational status and command arrangements, as well as level of warhead storage security.

- Agree on a standard reporting formula for tactical nuclear weapons inventories.

- Consider voluntary notifications of movement of tactical nuclear weapons.

- Exchange visits by military officials [presumably to storage locations].

- Exchange conditions and requirements for gradual reductions of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe, including clarifying the number of weapons that have been eliminated and/or stored as a result of the 1991-1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives (PNIs).

- Hold a NRC seminar on tactical nuclear weapons in the first quarter of 2012 in Poland.

According to estimates developed by Robert Norris and myself, the United States currently has an inventory of approximately 760 non-strategic nuclear weapons, of which 150-200 bombs are deployed in five European countries. Russia (updated estimate forthcoming soon, previous estimate here) has larger inventory of 3,700-5,400 nonstrategic weapons in central storage, of which an estimated 2,000 are deliverable by nuclear-capable forces.