Direct File Is the Floor, Not the Ceiling

And the Direct File product model approach shouldn’t just be for product teams, but all teams

Once a year Code for America brings together 1000+ of the most curious, forward thinking public sector minds at their annual Summit. Teams from across the country, from the federal, state, and local governments come together to discuss tangible ways to have a greater impact on their communities and constituents.

I was asked to give a talk on what lessons organizations can learn from my experience working on Direct File – the IRS’s beloved, free, online tax filing service – and how governments at any level can embark on greater digital transformation. You can check it out.

As you can tell, I’m proud of what our team accomplished with Direct File – but going forward, services similar to Direct File should be the bare minimum that government agencies offer. We proved that excellent digital experiences are possible in the federal government and the Direct File playbook can be adapted for not just new services, but the approach is applicable to wider agency transformation. The key plays – prototyping from day one, relentless user focus, empowering teams and holding them accountable for mission-level outcomes – are transferable not just from a product launch, but also to support agency modernization.

What can we learn from Direct File?

From my vantage point, Direct File success story offers both inspiration and frustration. First, the inspiration:

With satisfaction rates higher than Apple or Netflix and an 86% increase in trust for the IRS (PDF), Direct File proved that government can deliver excellent digital services by following this playbook:

- Prototype, even when you don’t think you’ve got a shot

- Appoint a single service owner

- Obsessively put the product in front of users with all different abilities – every day

- Build an in-house team that is both technically savvy, and in this example, tax savvy

- Build a service team – join up product and customer support so you have a continuous, real time feedback loop

- Use product data to inform product updates and reduce errors (in this example, the number of rejected returns submitted)

- Skip flashy launches in favor of actually helping people and their experience with government services.

This wasn’t a playbook that was handed to us. The Direct File team empowered itself without waiting for permission and ultimately demonstrated when you have when you bust through siloes, anything can be possible in government.

Now, the frustration:

This success – a successful, high stakes launch of a complex tax product that people loved – highlighted a painful truth: excellent products alone don’t transform institutions.

Despite Direct File’s achievements, it remained largely isolated within the broader IRS ecosystem. It was bolted onto existing systems rather than fundamentally changing how government operates. The public interest / civic technology sector has spent a decade of launching brilliant services and building strong teams and yet, the pattern remains the same – we create adjacent solutions without addressing the underlying institutional problems. With only 22% of Americans trusting the federal government to do the right thing, this incremental approach is no longer sufficient.

The path forward requires thinking bigger and going beyond the margins. Direct File should be the floor, not the ceiling – the bare minimum standard for government services. We need leaders who understand that government is fundamentally a software organization operating within bureaucracy built before telephones existed, and who are curious to explore how to run an entire agency with the same user-centric, technology-strategic approach that made Direct File successful. Technology and excellent user outcomes must be viewed as a strategic imperative at the highest levels, not an afterthought left to a silo within a large organization.

Building the future, today

While the chaotic ransacking of federal programs and firing hundreds of thousands of employees is no longer making headlines and seemingly slowed down come to an end, the principles of the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) will likely persist. Budget cuts will further constrain already constrained organizations.

Now, as a traumatized federal workforce is left to pick up the pieces of a government that was already in a precarious position pre-DOGE, the question is how can the government deliver for users in the future? Not just replace the capacity we’ve lost, but build a new infrastructure for federal employees to deliver real improvements for Americans that is relevant and resilient in the modern era?

Starting immediately where feasible, and with a vision for what’s possible, we should focus on building better institutions rooted in service to contemporary constituents. To do this we must start thinking of our institutions as places where, to use a software term, there is continuous improvement built in from the get-go.

Right now, I’m connecting with people who believe this is possible and necessary. We come from a diverse range of perspectives but we are all excited about exploring new operating models, theories of change, and building effective government services. We are all focused on providing tangible and ambitious new structures and services that can be implemented given current constraints, and hopefully built upon in the future.

Direct File showed that government can deliver in a new way that increases trust and raises expectations. Giving up on this momentum and progress is not an option – people rely on their government and will continue to do so in spite of whatever disdain elected officials may have for those who design and deliver those services.

As I said in my Code for America talk “The first rule of government transformation is: there are a lot of rules. And there should be-ish. But we don’t need to wait for permission to rewrite them. Let’s go fix and build some things and show how it’s done.”

We cannot afford to lose the progress we’ve gained, the lessons that have been learned over decades – and we can’t wait to take action. Connect with us to share your ideas where we can use technology and modern product led approaches to improve not just government service delivery, but also how we can reimagine how government works, now.

Creating A Vision and Setting Course for the Science and Technology Ecosystem of 2050

The science and technology (S&T) ecosystem is a complex network that enables innovation, scientific research, and technology development. The researchers, technologists, investors, educators, policy makers, and businesses that make up this ecosystem have looked different and evolved over centuries. Now, we find ourselves at an inflection point. We are experiencing long-standing crises such as climate change, inequities in healthcare, and education; there are now new ones, including the defunding of federal and private sector efforts to foster diverse, inclusive, and accessible communities, learning, and work environments.

As a Senior Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), I am focused on setting a vision for the future of the S&T ecosystem. This is not about making predictions; rather, it is, instead, about articulating and moving toward our collective preferred future. It includes being clear about how discoveries from the S&T ecosystem can be quickly and equitably distributed, and why the ecosystem matters.

The future I’m focused on isn’t next year, or the next presidential election – or even the one after that; many others are already having those discussions. I have my sights set on the year 2050, a future so far out that none of us can predict or forecast its details with much confidence.

This project presents an opportunity to bring together stakeholders across different backgrounds to work towards a common future state of the S&T ecosystem.

To better understand what might drive the way we live, learn, and work in 2050, I’m asking the community to share their expertise and thoughts about how key factors like research and development infrastructure and automation will shape the trajectory of the ecosystem. Specifically, we are looking at the role of automation, including robotics, computing, and artificial intelligence, in shaping how we live, learn, and work. We are examining both the transformative potential and the ethical, social, and economic implications of increasingly automated systems. We are also looking at the future of research and development infrastructure, which includes the physical and digital systems that support innovation: state-of-the-art facilities, specialized equipment, a skilled workforce, and data that enables discovery and collaboration.

To date, we’ve talked to dozens of experts in workforce development, national security, R&D facilities, forecasting, AI policy, automation, climate policy, and S&T policy to better understand what their hopes are, and what it might take to realize our preferred future. They have shared perspectives on what excites and worries them, trends they are watching, and thoughts on why science and technology matter to the U.S. My work is just beginning, and I want your help.

So, I invite you to share your vision for science and technology in 2050 through our survey.

The information shared will be used to develop a report with answers to questions like:

- What’s the closest we can get to a shared “north star” to guide the S&T ecosystem?

- What are the best mechanisms to unite S&T ecosystem stakeholders towards that “north star”?

- What is a potential roadmap for the policy, education, and workforce strategies that will move us forward together?

We know that the S&T epicenter moves around the world as empires, dynasties, and governments rise and fall. The United States has enjoyed the privilege of being the engine of this global ecosystem, fueled by public and private investments and directed by aspirational visions to address our nation’s pressing issues. As a nation, we’ve always challenged ourselves to aspire to greater heights. We must re-commit to this ambition in the face of global competition with clarity, confidence, and speed.

As we stand at this inflection point, it is imperative we ask ourselves – as scientists, and as a nation – what is the purpose of the S&T ecosystem today? Who, or what, should benefit from the risks, capital, and effort poured into this work? Whether you are deeply steeped in the science and technology community, or a concerned citizen who recognizes how your life can be improved by ongoing innovation, please share your thoughts by August 31.

In addition to the survey, we’ll be exploring these questions with subject matter experts, and there will be other ways to engage – to learn more, reach out to me at QBrown@fas.org.

It’s become acutely clear to me that the ecosystem we live in will be shaped by those who speak up, whether it be few or many, and I welcome you to make your voice heard.

The Data We Take for Granted: Telling the Story of How Federal Data Benefits American Lives and Livelihoods

Across the nation, researchers, data scientists, policy analysts and other data nerds are anxiously monitoring the demise of their favorite federal datasets. Meanwhile, more casual users of federal data continue to analyze the deck chairs on the federal Titanic, unaware of the coming iceberg as federal cuts to staffing, contracting, advisory committees, and funding rip a giant hole in our nation’s heretofore unsinkable data apparatus. Many data users took note when the datasets they depend on went dark during the great January 31 purge of data to “defend women,” but then went on with their business after most of the data came back in the following weeks.

Frankly, most of the American public doesn’t care about this data drama.

However, like many things in life, we’ve been taking our data for granted and will miss it terribly when it’s gone.

As the former U.S. Chief Data Scientist, I know first-hand how valuable and vulnerable our nation’s federal data assets are. However, it took one of the deadliest natural disasters in U.S history to expand my perspective from that of just a data user, to a data advocate for life.

Twenty years ago this August, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. The failure of the federal flood-protection infrastructure flooded 80% of the city resulting in devastating loss of life and property. As a data scientist working in New Orleans at the time, I’ll also note that Katrina rendered all of the federal data about the region instantly historical.

Our world had been turned upside down. Previous ways of making decisions were no longer relevant, and we were flying blind without any data to inform our long-term recovery. Public health officials needed to know where residents were returning to establish clinics for tetanus shots. Businesses needed to know the best locations to reopen. City Hall needed to know where families were returning to prioritize which parks they should rehabilitate first.

Normally, federal data, particularly from the Census Bureau, would answer these basic questions about population, but I quickly learned that the federal statistical system isn’t designed for rapid, localized changes like those New Orleans was experiencing.

We explored proxies for repopulation: Night lights data from NASA, traffic patterns from the local regional planning commission, and even water and electricity hookups from utilities. It turned out that our most effective proxy came from an unexpected source: a direct mail marketing company. In other words, we decided to use junk mail data to track repopulation.

Access to direct mail company Valassis’ monthly data updates was transformative, like switching on a light in a dark room. Spring Break volunteers, previously surveying neighborhoods to identify which houses were occupied or not, could now focus on repairing damaged homes. Nonprofits used evidence of returning residents to secure grants for childcare centers and playgrounds.

Even the police chief utilized this “junk mail” data. The city’s crime rates were artificially inflated because they used a denominator of annual Census population estimates that couldn’t keep pace with the rapid repopulation. Displaced residents had been afraid to return because of the sky-high crime rates, and the junk mail denominator offered a more timely, accurate picture.

I had two big realizations during this tumultuous period:

- Though we might be able to Macgyver some data to fill the immediate need, there are some datasets that only the federal government can produce, and

- I needed to expand my worldview from being just a data user, to also being an advocate for the high quality, timely, detailed data we need to run a modern society.

Today, we face similar periods of extreme change. Socio-technological shifts from AI are reshaping the workforce; climate-fueled disasters are coming at a rapid pace; and federal policies and programs are undergoing massive shifts. All of these changes will impact American communities in different ways. We’ll need data to understand what’s working, what’s not, and what we do next.

For those of us who rely on federal data in small or large ways, it’s time to champion the federal data we often take for granted. And, it’s also going to be critical that we, as active participants in this democracy, take a close look at the downstream consequences of weakening or removing any federal data collections.

There are upwards of 300,000 federal datasets. Here are just three that demonstrate their value:

- Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS): The NCVS is a sample survey produced through a collaboration between the Department of Justice and the Census Bureau that asks people if they’ve been victims of crime. It’s essential because it reveals the degree to which different types of crimes are underreported. Knowing the degree to which crimes like intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and hate crimes tend to be under-reported helps law enforcement agencies better interpret their own crime data and protect some of their most vulnerable constituents.

- NOAA’s ARGO fleet of drifting buoys: Innovators in the autonomous shipping industry depend on NOAA data such as that collected by the Argo Fleet of drifting buoys – an international collaboration that measures global ocean conditions. These detailed data train AI algorithms to find the safest and most fuel-efficient ocean routes.

- USGS’ North American Bat Monitoring Program: Bats save the American agricultural industry billions of dollars annually by consuming insects that damage crops. Protecting this essential service requires knowing where bats are. The USGS North American Bat Monitoring Program database is an essential resource for developers of projects that could disturb bat populations – projects such as highways, wind farms, and mining operations. This federal data not only protects bats but also helps streamline permitting and environmental impact assessments for developers.

If your work relies on federal data like these examples, it’s time to expand your role from a data user to a data advocate. Be explicit about the profound value this data brings to your business, your clients, and ultimately, to American lives and livelihoods.

That’s why I’m devoting my time as a Senior Fellow at FAS to building EssentialData.US to collect and share the stories of how specific federal datasets can benefit everyday Americans, the economy, and America’s global competitiveness.

EssentialData.US is different from a typical data use case repository. The focus is not on the user – researchers, data analysts, policymakers, and the like. The focus is on who ultimately benefits from the data, such as farmers, teachers, police chiefs, and entrepreneurs.

A good example is the Department of Transportation’s T-100 Domestic Segment Data on airplane passenger traffic. Analysts in rural economic development offices use these data to make the case for airlines to expand to their market, or for state or federal investment to increase an airport’s capacity. But it’s not the data analysts who benefit from the T-100 data. The people who benefit are the cancer patient living in a rural county who can now fly directly from his local airport to a metropolitan cancer center for lifesaving treatment, or the college student who can make it back to her home town for her grandmother’s 80th birthday without missing class.

Federal data may be largely invisible, but it powers so many products and services we depend on as Americans, starting with the weather forecast when we get up in the morning. The best way to ensure that these essential data keep flowing is to tell the story of their value to the American people and economy. Share the story of your favorite dataset with us at EssentialData.US. Here’s a direct link to the form.

Federation of American Scientists and Georgetown University Tech & Society Launch Fellowships for Former Federal Officials

New initiative brings nine experts with federal government experience to work with the FAS and Tech & Society’s Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation, the Knight-Georgetown Institute, and the Institute for Technology Law & Policy

Wednesday, June 11, 2025—Today Georgetown University’s Tech & Society Initiative and the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) announce two new fellowship programs. These fellowships will bring technologists, lawyers, and policymakers with recent federal government experience to Georgetown University centers, where they will advance nonpartisan research and analysis in their areas of expertise and engage with students.

Federal Alumni Fellows will work with Georgetown University’s Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation, the Knight-Georgetown Institute, and the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy to advance competition policy and antitrust enforcement in the tech sector, modernize consumer protection and competition for American innovation, and support expanded internet access for underserved communities.

Digital Service Alumni Fellows will be housed under the University’s Tech & Society Initiative and will collaborate with FAS senior fellows to develop and execute “big wins” that significantly impact the science and tech policy landscape. In addition to providing a place and community for senior leaders to carry forward their work, both FAS and Tech & Society are providing support for digital service experts exiting federal service and continuing to grow the skills of the next generation of leaders in tech and policy.

“The launch of the Federal Alumni and Digital Service Fellowship Programs is a critical step in leveraging the departure of leaders and innovators from the federal government who helped modernize tech policy and digital service delivery,” said incoming Tech & Society Chair and Beeck Center Executive Director Lynn Overmann. “The fellows will bring deep experience that aligns with Tech & Society’s mission to foster innovative and interdisciplinary approaches at the intersection of tech, ethics, and governance. The fellows will elevate our centers’ collaborative work and share their expertise with Georgetown students, benefiting both our academic community and the broader field of science, data, effective service delivery, and technology communications. I am thrilled to welcome them to Georgetown University.”

“At FAS, we believe that talented and well-placed policy entrepreneurs are one of the most critical keys to unlocking innovation and solving our society’s most pressing challenges,” said Dr. Jedidah Isler, Chief Science Officer at the Federation of American Scientists. “It’s why we launched our Senior Fellows Program earlier this year, and why we wanted to collaborate with Georgetown to supercharge our collective impact. Together with our FAS Senior Fellows, the Digital Services Alumni Fellows will tackle ambitious projects – from clean energy modernization to preserving the most essential federal datasets – that drive positive change. In an uncertain time, we are taking a bold step to lead the way and champion the current and future science, technology and innovation policy leaders we will need for tomorrow.”

Federal Alumni Fellows

Erie Meyer most recently served as chief technologist of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). She was on the implementation team that launched the bureau and was a founding member of its Office of Technology and Innovation. Prior to that, she served as senior adviser for policy planning to former Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina Khan, as well as FTC chief technologist and technology adviser to former FTC Commissioner Rohit Chopra. Before working at the FTC, Meyer launched the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) in the White House, served as senior director for Code for America, and was a senior adviser to the White House chief technology officer. She is a recipient of the Harvard Kennedy School’s Joan Shorenstein fellowship and received a bachelor’s degree in journalism from American University. Meyer will be placed at the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy.

Stephanie Nguyen most recently served as chief technologist of the FTC. She spearheaded and launched the agency’s first Office of Technology with senior technologist experts to strengthen and support enforcement matters. Prior to her tenure at the FTC, Nguyen worked at the USDS in the White House, where she built and deployed products and services to millions of people across the Department of Education, Department of State, Health and Human Services, and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. She previously was a research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, a researcher at Consumer Reports, and a Gleitsman scholar at the Center for Public Leadership. She received a Master in Public Policy from the Harvard Kennedy School and a bachelor’s degree in Digital Media Theory and Design from the University of Virginia. Nguyen will be placed at the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy.

Reed Showalter most recently served as senior policy adviser on the National Economic Council. Showalter has broad expertise in competition law, previously serving at the Department of Justice as counsel for antitrust in the Office of Legislative Affairs and as an attorney adviser in the Antitrust Division. He has also worked as an antitrust attorney at the FTC, an associate at the Kanter Law Group, and as a member of the Digital Markets Investigation in the House of Representatives. He received a J.D. from Columbia Law School and a B.A. in International Politics from New York University. Showalter will be placed at the Knight-Georgetown Institute.

Stephanie Weiner most recently served as chief counsel of the National Telecommunications and Information Administration in the Department of Commerce. She has held senior positions in private industry, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the Department of Energy. She previously served as senior legal adviser to former FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler, where she oversaw all FCC matters relating to broadband competition and deployment. She received her law degree, magna cum laude, from Northwestern University School of Law, her master’s degree in public policy from the University of Chicago, and her bachelor’s degree from Brown University. Weiner will be placed at the Georgetown Law Institute for Technology Law & Policy.

Digital Service Alumni Fellows

Thushan Amarasiriwardena is an Emmy award-winning product leader focused on artificial intelligence (AI) and public impact. He led Google’s earliest efforts to bring large language models into production to power the Google Assistant; this project grew into the foundations of Gemini. Most recently, he served in the White House’s USDS, driving AI products in federal agencies like the IRS, following the Biden-era AI executive order. Previously, he co-founded Launchpad Toys, a Y Combinator and venture backed startup acquired by Google. His apps were recognized by the New York Times and Apple as one of the top iPad Apps. Amarasiriwardena began his career as a journalist at The Boston Globe.

Luke Farrell is a public interest technology and policy executive. He currently serves as a fellow at FAS and as executive director for strategic innovation at the College Board. Most recently, Farrell served as senior adviser for technology and delivery on the White House Domestic Policy Council, where he worked to improve the delivery of core safety net benefits and health care for millions of Americans. At the USDS, he built and led rapid-response technology teams that mitigated nationwide supply chain shocks, launched critical public websites, and ensured millions of Americans remained enrolled in Medicaid following the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency. Prior to government service, Farrell led crisis response and machine learning teams at Google.

Faith Savaiano is a public policy professional and consultant with expertise in technology, government innovation, and STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) workforce development. Most recently, she served as a digital services expert with the USDS, where she provided policy guidance and contributed to the implementation of workforce and skilling objectives in President Biden’s executive order on AI. Additionally, she served as a subject-matter expert on federal regulatory policies and issues related to the federal workforce, public-private partnerships, and technology policy. Previously, Savaiano was the associate director of social innovation at the Federation of American Scientists, where she helped launch and lead a fellowship program that has now placed more than 100 technical experts into government. Prior to that time, she has worked at a variety of advocacy organizations focused on STEM workforce and education issues and the U.S. Department of State.

Diego Núñez most recently served in the Biden-Harris administration’s White House Climate Policy Office as a senior policy adviser. In that role, he led major initiatives across the power and transportation sectors, focusing on advanced transmission technologies, grid modernization, nuclear power, critical minerals, and solutions to manage increased demand from data centers and AI. Núñez began his tenure in the White House as an Associate Staff Secretary. Before that, Núñez served at the Department of the Treasury in the Office of Recovery Programs, at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, and on multiple political campaigns.

Meron Yohannes is a fellow at FAS focused on innovation, inclusivity, and technology related to economic and national security policy. Most recently, she served as the senior policy adviser for the U.S. Secretary of Commerce, formulating policy decisions related to economic development, minority businesses, workforce development, disaster recovery, and entrepreneurship. Her purpose was to guide policy development and program design for several agencies, a portfolio worth over $5 billion in funding that benefits underserved, distressed, and rural communities. Previously, she was the housing, infrastructure, and technology policy analyst at the Bipartisan Policy Center, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank researching and developing recommendations on affordable housing, water infrastructure, AI implications for the U.S. workforce, and evidence-based policymaking.

Participating Organizations:

Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University:

The Beeck Center for Social Impact + Innovation at Georgetown University connects government and the civic tech ecosystem to tackle problems that no one can solve alone, to create a people-centered, digitally-enabled government for all. An anchor of Georgetown University’s Tech & Society Initiative, the Beeck Center works alongside public, private, and nonprofit organizations to identify and establish human-centered solutions that help government services work better for everyone—especially the most vulnerable and underserved populations.

Federal of American Scientists:

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges.

Institute for Technology Law & Policy at the Georgetown University Law Center:

The Tech Institute is a hub for policymakers, academics, advocates, and technologists to study and discuss how to center humans and the social good, using technology as a tool. With the leading academic program for law and technology in the United States, the institute trains the next generation of lawyers and lawmakers with deep expertise in technology law and policy, provides nonpartisan insights to policymakers on issues related to new and emerging technologies, and fosters interdisciplinary approaches to solving complex technology law and policy problems.

Knight-Georgetown Institute:

The Knight-Georgetown Institute (KGI) is dedicated to connecting independent research with technology policy and design. KGI serves as a central hub for the growing network of scholarship that seeks to shape how technology is used to produce, disseminate, and access information. KGI is designed to provide practical resources that policymakers, journalists, and private and public sector leaders can use to tackle information and technology issues in real time. Georgetown University and the Knight Foundation came together to launch the institute in 2024.

Tech & Society Initiative:

The Tech & Society Initiative creates novel approaches for interdisciplinary collaboration, research, and understanding at the intersection of technology, ethics, and governance at Georgetown University. We bring together ten centers and programs at Georgetown that are deeply immersed in particular parts of the technology and society equation: ethics, privacy, national security, law, policy, governance, and data—and we are building connective tissue between them. We identify the points of connection between them, and then create opportunities for them to collaborate in tangible and productive ways.

Media Contact

Jessica Yabsley

Director of Communications

jessica.yabsley@georgetown.edu

Updating the Clean Electricity Playbook: Learning Lessons from the 100% Clean Agenda

Building clean energy faster is the most significant near-term strategy to combat climate change. While the Biden Administration and the advocacy community made significant gains to this end over the past few years, we failed to secure major pieces of the policy agenda, and the pieces we did secure are not resulting in as much progress as projected. As a result, clean energy deployment is lagging behind levels needed to match modeled cost-effective scenarios, let alone to achieve the Paris climate goals. Simultaneously, the Trump Administration is actively dismantling the foundations that have underpinned our existing policy playbook.

Adjusting course to rapidly transform the electricity sector—to cut pollution, reduce costs, and power a changing economy—requires us to upgrade the regulatory frameworks we rely upon, the policy tools we prioritize, and the coalition-building and messaging strategies we use.

After leaving the Biden Administration, I joined FAS as a Senior Fellow to jump into this work. We plan to assess the lessons from the Biden era electricity sector plan, interrogate what is and is not working from the advocacy community’s toolkit, and articulate a new vision for policy and strategy that is durable and effective, while meeting the needs of our modern society. We need a new playbook that starts in the states and builds toward a national mission that can tackle today’s pressing challenges and withstand today’s turbulent politics. And we believe that this work must be transpartisan—we intend to draw from efforts underway in a wide range of local political contexts to build a strategy that appeals to people with diverse political views and levels of political engagement.

This project is part of a larger FAS initiative to reimagine the U.S. environmental regulatory state and build a new system that can address our most pressing challenges.

Betting Big on 100% Clean Electricity

If we are successful in fighting the climate crisis, the largest share of domestic greenhouse gas emissions reductions over the next ten years will come from building massive amounts of new clean energy and in turn reducing pollution from coal- and gas-fired power plants. Electricity will also need to be cheap, clean, and abundant to move away from gasoline vehicles, natural gas appliances in homes, and fossil fuel-fired factories toward clean electric alternatives.

That’s why clean electricity has been the centerpiece of federal and state climate policy. The signature climate initiative of the Obama Administration was the Clean Power Plan. Over the past several decades, states have made the most emissions progress through renewable portfolio standards and clean electricity standards that require power companies to provide increasing amounts of clean electricity. Now 24 (red and blue) states and D.C. have goals or requirements to achieve 100 percent clean electricity. And in the 2020 election, Democratic primary candidates competed over how ambitious their plans were to transform the electricity grid and deploy clean energy.

As a result of that competition and the climate movement’s efforts to put electricity at the center of the strategy, President Biden campaigned on achieving 100 percent clean electricity by 2035. This commitment was very ambitious—it surpassed every state goal except Vermont’s, Rhode Island’s, and D.C.’s. In making such a bold commitment, Biden recognized how essential the power sector is to addressing the climate crisis. He also staked a bet that the right policies—large incentives for companies, worker protections, and support for a diverse mix of low-carbon technologies—would bring together a coalition that would fight for the legislation and regulations needed to make the 2035 goal a reality.

A Mix of Wins and Losses

That bet only partially paid off. We won components of the agenda that made major strides toward 100% clean electricity. New tax credits are accelerating deployment of wind, solar, and battery storage (although the Trump Administration and Republicans in Congress are actively working to repeal these credits). Infrastructure investments are driving grid upgrades to accommodate additional clean energy. And new grant programs and procurement policies are speeding up commercialization of critical technologies such as offshore wind, advanced nuclear, and enhanced geothermal.

But the movement failed to secure the parts of the plan that would have ensured an adequate pace of deployment and pollution reductions, including a federal clean electricity standard, a suite of durable emissions regulations to cover the full sector, and federal and state policies to reduce roadblocks to new infrastructure and align utility incentives with clean energy deployment. We ran into real-world and political headwinds that held us back. For example, deployment was stifled by long timelines to connect projects to the grid and local ordinances and siting practices that block clean energy. Policy initiatives were thwarted by political opposition from perceived reliability impacts and blowback from increasing electricity rates, especially for newer technologies like offshore wind and advanced nuclear. The opposition to clean energy successfully weaponized the rising cost of living to fight climate policies, even where clean energy would make life less expensive. These barriers not only impeded commercialization and deployment but also dampened support from key stakeholders (project developers, utilities, grid operators, and state and local leaders) for more ambitious policies. The necessary coalitions did not come together to support and defend the full agenda.

As a result, we are building clean energy much too slowly. In 2024, the United States built nearly 50 gigawatts of new clean power. This number, while a new record, falls short of the amount needed to address the climate crisis. Analysis from three leading research projects found that, with the tax incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act, the future in which we get within striking distance of the Paris climate goals requires 70 to 125 gigawatts of new clean power per year for the next five years, 40 to 250 percent higher than our record annual buildout.

Where do we go from here?

The climate crisis demands faster and deeper policy change with more staying power. Addressing the obvious obstacles standing in the way of clean energy deployment, like the process to connect power plants to the grid, is necessary but insufficient. We must also develop new policy frameworks and expanded coalitions to facilitate the rapid transformation of the electricity system.

This work requires us to ask and creatively answer an evolving set of questions, including: What processes are holding us back from faster buildout, and how do we address them? How can utility incentives be better aligned with the deployment and infrastructure investment we need and support for the required policies? How can the way we pay for electricity be better designed to protect customers and a livable climate? Where have our coalitional strategies failed to win the policies we need, and how do we adjust? How should we talk about these problems and the solutions to build greater support?

We must develop answers to these questions in a way that leads us to more transformative, lasting policies. We believe that, in the near term, much of this work must happen at the state level, where there is energy to test out new ideas and frameworks and iterate on them. We plan to build out a state-level playbook that is actionable, dynamic, and replicable. And we intend to learn from the experiences of states and municipalities with diverse political contexts to develop solutions that address the concerns of a wide range of audiences.

We cannot do this work on our own. We plan to draw on the expertise of a diverse range of organizations and people who have been working on these problems from many vantage points. If you are working on these issues and are interested, please join us in collaboration and conversation by reaching out to akrishnaswami@fas.org.

Bridging Innovation and Expertise: Connecting Federal Talent to America’s Tech Ecosystems

The semiconductor shortfall during the COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted the consequences of underinvesting in critical technology ecosystems. This wake-up call, following years of advocacy and growing consensus, spurred bipartisan action through the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which made transformative investments in the semiconductor industry as well as future-focused programs like the Economic Development Administration’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs (Tech Hubs) – a program I helped launch as EDA’s chief of staff – and the National Science Foundation’s Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines). These latter two initiatives – Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – are catalyzing dynamic innovation ecosystems across the country, advancing technologies critical to our national security and economic competitiveness while spurring broad-based regional economic growth.

But as these innovation ecosystems grow, so too does their demand for talent. Across these ecosystems, there is a need to fill specialized positions essential to their success. At the same time, we’re witnessing an exodus of talent from the federal service – scientists, engineers, technologists, workforce experts, and skilled generalists – professionals whose expertise could be lost altogether if not effectively deployed. While these departures are deeply troubling for government operations and the services Americans rely on, we face three pressing imperatives: preserving specialized knowledge, responding to the human impact on individuals suddenly without work, and addressing critical talent needs among these tech regions. During my time as a Senior Fellow at FAS, I’m focused on building bridges that connect these experienced professionals with innovation ecosystems where they can continue to apply their hard-won expertise in service of important national priorities.

Innovation ecosystems: What are they?

Both NSF Engines and Tech Hubs seek to advance critical and emerging technologies, but each focuses on different stages of technological advancement – NSF Engines on the research and development and early translation of technologies, while Tech Hubs comes in to support scaling and commercializing these technologies to achieve global competitiveness.

Together, they’re advancing our capabilities in 10 key technology areas:

- Advanced manufacturing and robotics

- Advanced materials

- Artificial intelligence

- Biotechnology

- Communications technology and immersive technology

- Cybersecurity and data storage

- Disaster risk and resilience

- Energy technology

- Quantum

- Semiconductors and advanced computing.

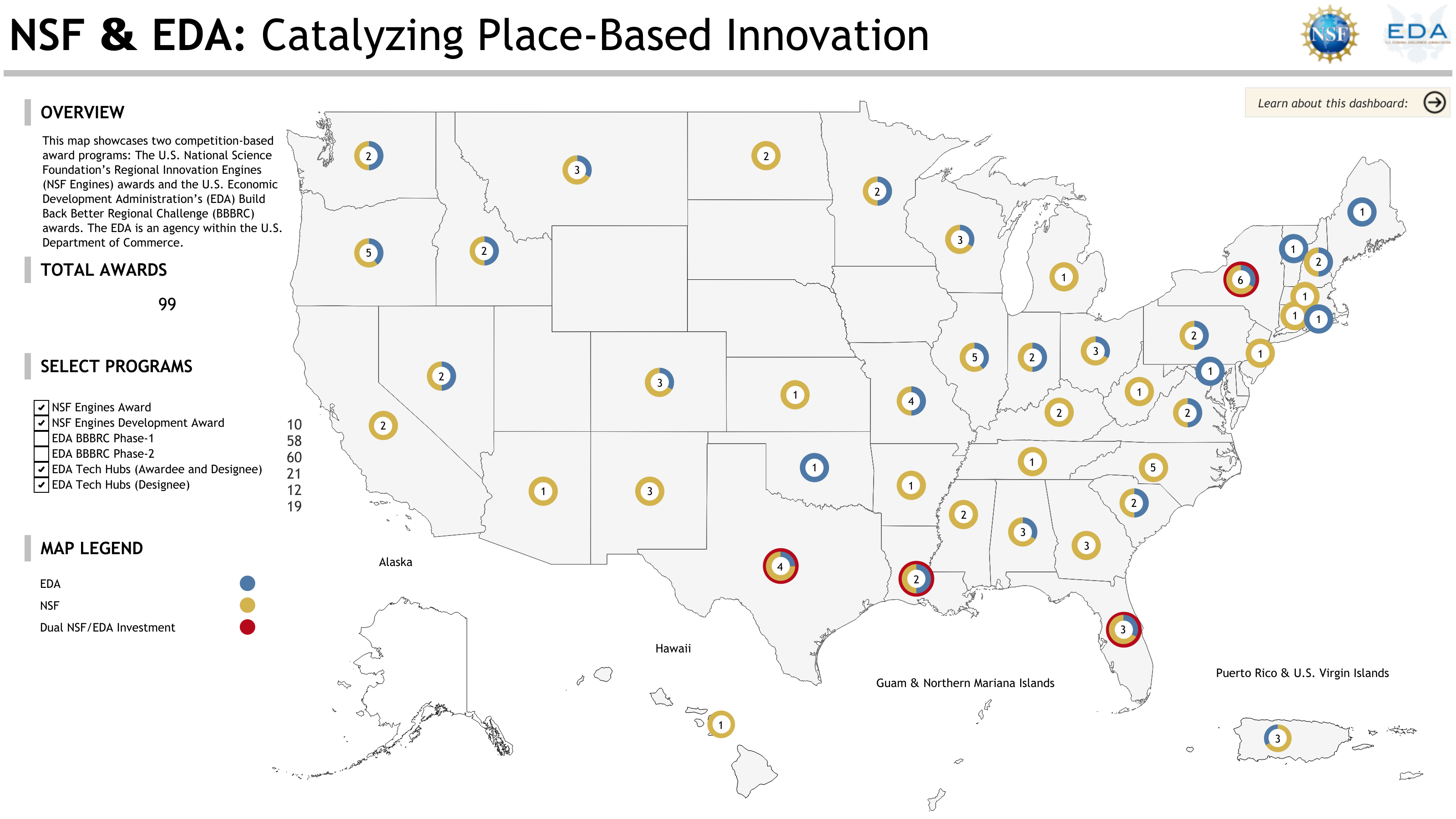

This geographically distributed innovation model is taking root across America, with 31 designated Tech Hubs and 10 NSF Engines receiving between approximately $15 million to $50 million each – not to mention the dozens of other innovation ecosystems that received development grants to continue to build their ecosystem strategies – spanning the majority of states across the country.

Map of NSF Engines & EDA BBBRC via NSF on Tableau

Note: NSF’s interactive map also includes the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, a program of the Economic Development Administration, that includes many innovation ecosystems that span the country as well. In this version, only Tech Hubs and NSF Engines are demarcated on the map.

The strength of these innovation ecosystems lies in their coalition approach, which brings together industry, start-ups, research universities, community colleges, economic and workforce development organizations, community-based nonprofits, and entrepreneurial ecosystem builders. As these ecosystems scale, this broad spectrum of stakeholders need talent to fill a variety of roles: lab scientists, engineers, technicians, partnership managers, business support and entrepreneurship program staff, workforce development program managers, and other specialized industry and ecosystem builder roles. Where will some of this talent come from? I believe part of the answer lies in the talented professionals departing federal service.

The federal service: Who are they?

Since January 2025, tens of thousands of federal workers have left the federal government, in addition to thousands of contractors who have supported government services. They come from agencies where they worked in areas helpful to innovation ecosystems, like the National Institutes of Health (helpful for biotech-focused ecosystems) to the Department of Labor (helpful for workforce development strategizing). These individuals have managed multimillion-dollar grant programs, provided expert technical analyses and developed best practices across every area you can think of, and navigated complex stakeholder networks. Many already live in or near regions with emerging innovation ecosystems, given the distributed nature of federal agencies, and others are willing to relocate for the right mission-driven opportunity, potentially even back to places they call home. Their early involvement in these innovation ecosystems would help build the momentum needed for technological breakthroughs and sustained growth, in turn leading to more job creation for others at the local and regional level.

The initiative

With FAS’s support, I am launching an initiative to connect scientists, engineers, technologists, economic and workforce development practitioners, program manager extraordinaires, and other professionals who recently departed federal service with emerging innovation ecosystems across the country that need their expertise.

We’re talking directly with Tech Hubs and NSF Engines communities to identify immediate and near-term talent needs within their leadership teams, across federally funded Tech Hub and NSF Engine component projects, and among consortium stakeholders. Simultaneously, we are engaging displaced federal workers and contractors through job fairs and direct outreach to understand their skillsets, career interests, and location preferences. To help both innovation ecosystems and these workers, we aim to showcase opportunities across innovation ecosystems, facilitate direct matchmaking to expedite hiring, and create additional resources tailored to the needs of these professionals and innovation ecosystems.

This is an opportunity for innovation ecosystems to take advantage of the availability of mission-driven professionals who have transferable skills to meet the needs of these regions. At the same time, this allows former federal professionals to continue meaningful, public-purpose work that contributes to America’s technological leadership in a new capacity.

It is to our national peril if we do not set up these innovation ecosystems to succeed. And it is also to our peril if we do not leverage the thousands of years of collective experience these former feds have to offer. This FAS initiative wants to see regions, people, and the country succeed, and is doing so by addressing critical talent gaps in these strategically imperative innovation ecosystems, offering pathways for continued public-purpose impact, and ensuring the nation as a whole does not lose valuable expertise.

What you can do

We are excited to share more information soon on these available opportunities and how federal workers can plug in. In the meantime, if you are an innovation ecosystem – even outside of Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – please do reach out to learn more or share open roles. If you are a federal worker, fill out this interest form, and we’ll add you to the list to receive more information as it becomes available. And if you have any thoughts to offer on this initiative, we are all ears.

As the design of Tech Hubs and NSF Engines shows us, it takes a coalition of committed organizations and individuals to achieve big, but necessary, goals.

Maryam Janani-Flores (mjananiflores@fas.org) is a Senior Fellow at FAS and former chief of staff at the U.S. Economic Development Administration.

Goodbye IRS Direct File, Hello Inefficiency

Decision to Sunset IRS’ Direct File Previews Worse Taxpayer Experience in 2026

Yesterday, tens of thousands of taxpayers filed their returns using IRS Direct File, the agency’s new free, public, online tax filing service now in its second filing season. They joined hundreds of thousands who have used the service, and who have been nearly-unanimously thrilled to fulfill their tax obligations easily and directly. It seems we have finally done the impossible: make Tax Day anything but the most dreaded day of the year. At least we did.

Today, the Associated Press reported that the Treasury Department will discontinue the program. “Cutting costs and saving money for families were just empty campaign promises,” says Adam Ruben, a vice president at the Economic Security Project of the administration’s decision to end the program.

I was an original architect of Direct File from 2021 until just a few months ago, and got to see its impact on government and on taxpayers directly. Make no mistake: Direct File is a shining example of government capacity and government efficiency. By providing a critical government service for free, and helping taxpayers file more timely and more accurate returns, it is projected to eventually generate $11 billion in net savings for taxpayers every year.

The dismantling of the program is not, at all, a step toward government efficiency. This is a move that will degrade our government services, incurring massive costs for people trying to file their taxes, further damaging the capacity of the nation’s revenue-collection agency, and making our institutions less robust and less capable.

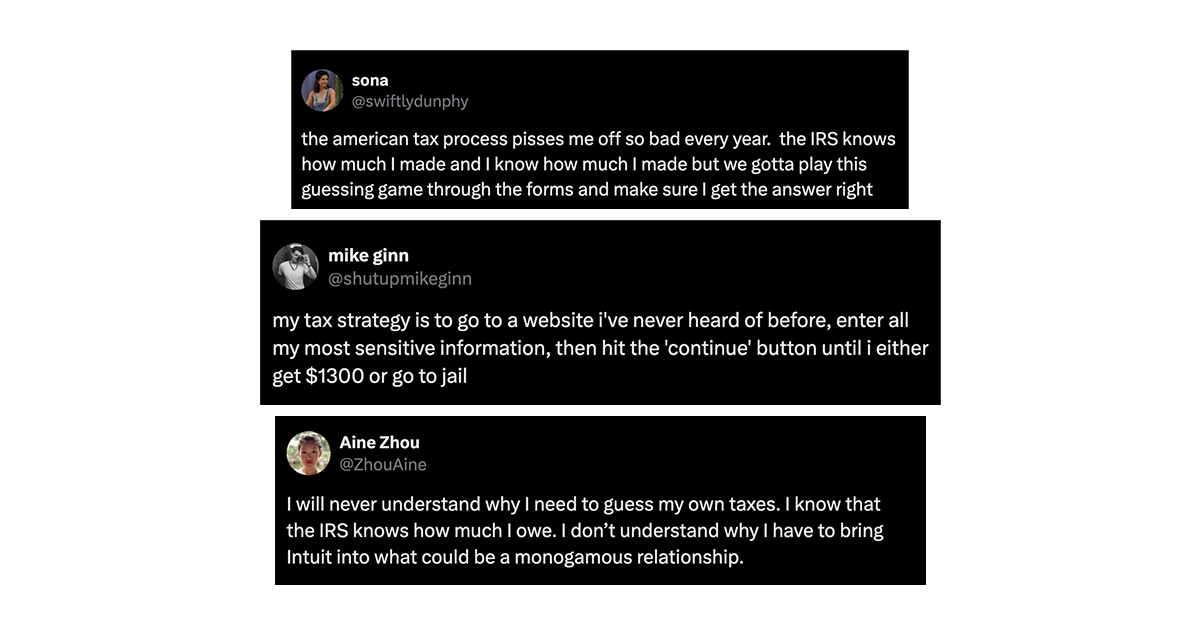

It’s no secret: Americans do not love tax season.

The Direct File story started for me, personally, when I moved back to the U.S. after living in London for 9 years. I had already spent years working in digital services: I had built the first in-house digital team at the brand-new Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in 2010, and then worked on multiple projects in London, culminating in helping the London Borough of Camden digitally transform its entire operations practically overnight during the pandemic. I moved back to the States and joined the US Digital Service to help rebuild after Covid, bringing the lessons I had learned from the UK. My first project at USDS was leading our efforts on Child Tax Credit expansion — ensuring that families across the country could access the enormous new child benefit that was created in the March 2021 American Rescue Plan.

But there was a problem: families naturally had to file a tax return to claim their tax credit. And I was pretty surprised to learn that our government still did not, in 2021, offer a free, online way to file your taxes directly with the government. Around the world, tax collection is seen as an inherent government function and, as such, tax filing is a service that the government offers free of charge. I thought we should too, especially if we were going to make such critical social supports contingent on it during a crisis.

Instead, in the U.S., we relied on a confusing — and sometimes costly — mishmash of private offerings and support from non-profits designed to ensure most people could maybe, sort of, file a return for free if they needed to. It made the barrier to entry high, both in terms of trying to navigate how to simply file a return, nevermind to do so without cost. Tax filing, I thought, is a core function of government, and making it free and easy to use would cut through this waste and deliver for the American people.

I wasn’t the only one who thought this way. By 2021, a free public filing service was already the “white whale” of civic tech; everyone knew this was the critical government function to bring into a modern digital product, and yet it was too big, too daunting, too much of a change. Honestly, never in a million years did I think we would pull it off, either. The IRS, for all its genuine accomplishments in the face of constantly shrinking budgets and aging technology, had no real experience launching an enormous, high-stakes tech product designed to simplify the mind-numbing complexities of an American tax return. This was government capacity we would have to create.

But, we did. Since Direct File launched as a pilot in March 2023, hundreds of thousands of people have now filed their returns with it, to stunning results. In its pilot year, 86% of users said that Direct File increased their trust in the IRS. In its second year, it is winning awards and killing it with users, with a Net Promoter Score in the +80s, up from +74 last year (Apple’s, which is considered astronomically high, is +72). Direct File is a wildly successful government startup. Not only that, but the IRS now has its own in-house capacity to continue building awesome digital experiences — capacity that could have gone toward cost savings and experience improvements in all matter of IRS operations. This is all capacity, needless to say, that has gone away, all in the name of “efficiency.”

The impact for taxpayers from Direct File alone are, and would have been, enormous. In the U.S., the IRS estimates that it takes the average person over 9 hours and costs $160 to file your taxes each year. We even heard anecdotally from Direct File users who had paid thousands of dollars to do what Direct File does for free. There also remain millions of households who, every year, don’t file their returns at all, leaving sizable refunds on the table, because they can’t navigate the confusing tax filing “offers” advertising tax filing services. These households would have stood to finally access billions of dollars they leave unclaimed every year.

Not only are taxpayers saving these hundreds of dollars, they also feel newly empowered to interact with their government and take control of their tax situations. For decades, Americans have been told that they are not smart enough to do your own taxes; only highly-paid specialists that you have to pay for, can do it for you. Direct File stripped away the noise and showed taxpayers that filing can be simple and easy. The valuable trust this creates in government and public institutions is impossible to quantify.

Finally, there is the issue of data privacy and security. Taxpayers filing via private services must expose their most sensitive personal and financial information to third parties that monetize their data, sometimes illegally and without taxpayers’ consent. Without a public filing option, taxpayers are more or less required to sacrifice their privacy and the security of their data just to fulfill their filing obligations. Direct File gives taxpayers the option to protect their data and provide it straight to the tax agency, without a middleman.

All this — the in-house capacity to modernize the IRS, billions of dollars in cost savings, an empowered public — is what is cancelled today. But they have it exactly backwards. It’s a functional, high-quality government that’s efficient. The chaos they are sowing is anything but.

Federation of American Scientists Announces Arrival of our Inaugural Cohort of Senior Fellows to Advance Audacious Policy that Benefits Society

Fellows Brown, Janani-Flores, Krishnaswami, Ross and Vinton will work on projects spanning government modernization, clean energy, workforce development, and economic resiliency

Washington, D.C. – March 17, 2025 – Today our first cohort of Senior Fellows join the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), a non-partisan, nonprofit science think tank dedicated to developing evidence-based policies to address national challenges. These senior-level scientists and technologists represent a diverse group of thinkers and doers with deep experience across multiple fields who have committed to developing policy solutions to specific problems. The fellows were selected through a competitive process of project proposals, and will work in their area of expertise independently and collaboratively with FAS staff for six months.

“We are leaning into the reality of the present moment and bringing exceptional talent to join forces with our staff and the wider science and policy community to develop new policy ideas that solve specific and difficult societal challenges,” says Daniel Correa, CEO of the Federation of American Scientists.

Senior Fellows – 2025 Cohort

The inaugural cohort of senior fellows and their primary areas of focus are:

Quincy K. Brown served as Director of Space STEM and Workforce Policy on the National Space Council in the White House Office of the Vice President. She will design a participatory, strategic foresight process to identify solutions to the most pressing challenges we face in the evolving science and technology ecosystem. She will leverage data-driven insights, strategic partnerships, and evidence-based research to shape national policy, scale innovative initiatives, and cultivate cross-sector collaborations.

Maryam Janani-Flores served as the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Economic Development Administration at the Department of Commerce, where she oversaw policy, strategy, and operations for a $5 billion grant portfolio. She will focus on broad-based participation in innovation ecosystems by placing recently departed federal scientists, engineers, and technologists in innovation hubs nationwide to build inclusive, durable innovation ecosystems.

Arjun Krishnaswami served in the Biden-Harris Administration as the Senior Policy Advisor for Clean Energy Infrastructure in the White House. He will take lessons learned at the federal level to elicit adoption of clean technology at the state level, modernizing our nation’s energy grid so that communities across the country can benefit from the greater resiliency, lower costs, and cleaner air that follow from clean energy upgrades.

Denice Ross, former U.S. Chief Data Scientist and Deputy U.S. CTO, will prototype a Federal Data Use Case Repository for documenting and sharing how people across the nation use priority federal datasets from many agencies. Her project is a front-line effort to protect the continued flow of federal data.

Merici Vinton served as a Senior Advisor to IRS Commissioner Danny Werfel and prior to that was an original architect of the Direct File service. She will focus on technology innovation to deliver public services in a post “digital services” era, making institutions more relevant and responsive.

“This is a time where we need solutions, and these senior fellows bring with them the expertise, motivation and a vision for how to use policy as a tool to affect meaningful, positive change,” says Dr. Jedidah Isler, Chief Science Officer at FAS.

She continues: “These senior fellows have years of hands-on experience to draw upon to imagine, plan, and develop ambitious science and technology policy. We look forward to a bidirectional flow of expertise between senior fellows and our staff to deliver actionable policy ideas that will serve the public using the technical tools of today and emerging technology of tomorrow. They give me hope that we can co-create a future that provides safety, access and prosperity for all.”

Role of Senior Fellows at FAS

Senior fellows will work independently to develop and refine their policy plans over the next six months. All of the proposals are ambitious; to reach their desired outcomes, fellows will collaborate with a wide range of stakeholders in the science and policy communities, seeking to understand and implement feedback from evidence-based datasets, specialized experts, people with lived experience, and ultimately, from the people whom their policy could impact.

During the course of this policy development senior fellows will have access to FAS resources and full-time staff to ensure these ideas can be realized.

Senior fellows will be an extension of the wide range of scientific and technical expertise housed within FAS – ranging from nuclear weapons to climate science to emerging technologies – one of the country’s oldest science policy think tanks.

###

About FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address national challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.