Old Anti-nuclear Movie from FAS

The Federation of American Scientists was formed just a couple of months after the dawning of the nuclear age by scientists as who had worked on the Manhattan Project to develop the world’s first nuclear weapons. In the fall of 1945, there was tremendous interest in the new atomic bomb: what it was, how it worked, and its effects–and not just direct effects but the effect this invention would have on the military balance and politics of the world. FAS organized a group of its members, which it called the National Committee on Atomic Information, to talk to the public, the press, and political leaders, and to produce media materials for distribution. (Sixty two years later and we still seem to be at it…)

Jeff Aron here at FAS recently came across this amazing little film on YouTube called One World or None. It was produced by FAS and the National Committee. I have to admit, no one currently at FAS knew about it, it predates anyone’s memory here, and we are ourselves doing some research on its origins and asking our long-term members what they know. (If any of our blog readers can provide any information, please let us know.) Presumably, it was released in conjunction with the release of the first publication of the Federation, also called One World or None, a collection of essays by great scientists of the day, including Albert Einstein, that was first published in 1946. One World has recently been reprinted by the New Press in New York and is available through bookstores, Amazon, and the FAS website.

The film is clearly a bit dramatic, but the dangers of nuclear weapons are dramatic. By today’s standards, the graphics are Stone Age but the message is as important today as it ever was and doesn’t depend on fancy graphics. I can’t say you should enjoy this little film–not much to enjoy when discussing nuclear dangers–but I hope you take it to heart. The Federation is still working to reduce the global threat of nuclear weapons.

A Response to Congresswoman Tauscher’s Article in Nonproliferation Review

A recent article, “Achieving Nuclear Balance”, in Nonproliferation Review, by Congresswoman Ellen Tauscher, Chairwoman of the Strategic Forces Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, includes a sobering summary of the dangerous nuclear policies of the Bush administration, including its desire for new nuclear weapons and an expansion of the roles of nuclear weapons. Congresswoman Tauscher has been an important voice of reason in the nuclear debate and one of the primary forces behind efforts to force a fundamental review of the missions of nuclear weapons, to ask what nuclear weapons are for.

Nevertheless, her arguments in support of exploring the Reliable Replacement Warhead are mistaken and based on deeply rooted but ultimately unsupported assumptions. Her essay highlights the critical importance of carefully defining terms and avoiding being fooled by our own euphemisms.

(more…)

Targeting Missile Defense Systems

By Hans M. Kristensen

The now month-long clash between Russia and the West over U.S. plans to build a missile defense system in Europe should warn us that – despite important progress in some areas – Cold War thinking is alive and well.

The missile defense system, Moscow says, is but the latest step in a gradual military encroachment on Russian borders by NATO, and could well be used to shoot down Russian ballistic missiles. The head of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces and President Putin have suggested that Russia might target the defenses with nuclear weapons. The United States has rejected the complaints insisting that Russia has nothing to fear and that the defenses will only be used against Iranian ballistic missiles. European allies have complained that the Russian threats are unacceptable and have no place in today’s Europe.

That may be true, but the reactions have revealed a frightening degree of naiveté about strategic war planning in the post-Cold War era, a widespread belief that such planning has somehow stopped. It has certainly changed, but all the major nuclear weapon states insist that they must hedge against an uncertain future and continue to adjust their strike plans against potential adversaries that have weapons of mass destruction. Russia continues to plan against the West and the West continues to plan against Russia. The plans are not the same that existed during the Cold War, but they are strike plans nonetheless.

The argument made by some officials that missile defense systems are merely defensive and don’t threaten anyone is disingenuous because it glosses over a fact that all planners know very well: Even limited missile defenses become priority targets if they can disturb other important strike plans. The West concluded that very early on in its military relationship with Russia.

Cold War Targeting of Missile Defense Systems

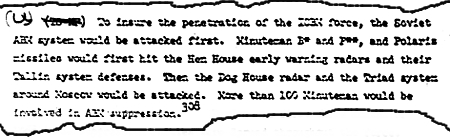

In 2003, I received a declassified Strategic Air Command document that showed how the United States reacted when the Soviet Union built a limited missile defense system back in the late 1960s. The response was overwhelming: A nuclear strike plan that included more than 100 ICBMs plus an unknown number of SLBMs to overwhelm and destroy the Soviet interceptors and radars. Based on the declassified information, two colleagues and I estimated in an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the total strike plan involved approximately 130 nuclear warheads with a total combined yield of some 115 megatons. Here is how the SAC historian described the plan:

|

|

|

|

“To ensure the penetration of the ICBM force, the Soviet ABM system would be attacked first. Minuteman E and F and Polaris missiles would first hit the Hen House early warning radars, and their Tallin system defenses [SA-5 SAM, ed.]. Then the Dog House radar and the Triad system around Moscow would be attacked. More than 100 Minuteman would be involved in the ABM suppression.” |

The Soviet ABM system back then consisted of about fifteen facilities, including eight launch sites around Moscow with a total of 64 nuclear-tipped interceptors, half a dozen SA-5 launch complexes (later found not to have much ABM capability) near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and at least three large early warning radars. Each of these surface facilities were highly vulnerable to the blast effect from a single nuclear warhead, so the large number of ICBMs was mainly needed to “suppress” (overwhelm) the interceptors.

In the late 1980s, the Soviets upgraded they system by moving 32 remaining interceptors at four sites into underground silos (see Figure 2) and adding 68 shorter-range nuclear-tipped interceptors at five new sites closer to Moscow. This hardened and dispersed the interceptors, requiring U.S. planners to upgrade their strike plan, which probably ballooned to more than 200 warheads (although with less total yield due to more accurate missiles with less powerful warheads).

|

|

|

|

Four long-range Gorgon interceptor site crescent Moscow toward the northwest. The 217-mile (350-kilometer) range Gorgon carries a 1 Megaton warhead. The site shown here is near Poryadino southwest of Moscow. There are unconfirmed rumors that the interceptors have been removed and the system is in the process of decommissioning. |

The 68 shorter-range (50 miles, 80 km) interceptors added to the system in the late 1980s were the nuclear-armed Gazelle. Each missile carried a 10-kiloton warhead. The five launch sites, which are still thought to be operational, are positioned in a circle around Moscow approximately 13 miles (23 kilometers) from the center of the city. The 68 interceptors are deployed in hardened silos, 16 at two sites (Northwest and Southeast), and 12 at each of the other three sites. Public uncertainty about the location of the fifth site was recently resolved by a satellite image showing the site next to the Pill Box radar north of Moscow.

|

|

|

|

Five launch sites with Gazelle interceptors in hardened silos are located in a circle around Moscow as part of the A-135 ABM system. The sites have either 12 silos, like the Southwestern site (top) near Moscow Vnukovo airport, or 16. The fifth site (bottom) next to the Pill Box ABM radar north of Moscow has 12 silos, and is depicted in the Pentagon drawing (insert). |

All of this happened during the Cold War and many things have changed, but the basic motivation for targeting a limited missile defense system then was the same as today: The Soviet ABM system was entirely defensive and couldn’t threaten anyone (to paraphrase a characterization frequently use by U.S. and NATO officials to justify their missile defense plans today), but it could disturb the main ICBM attack on Moscow and military facilities downrange. That made it a top-priority target. And even though U.S. planners suspected that the system was not very efficient, they committed about 10 percent of the entire ICBM force to destroy it. To the extent the Russia ABM is operational, U.S. nuclear strike plans probably still target it today.

|

Figure 4: |

||

|

||

| Type | Designation, Location | Remarks |

| Interceptor | ||

| Gorgon (SH-11/ABM-4)* | – E05, 6 miles (9 km) southwest of Karabanovo, at 56°14’39.51″N, 38°34’41.75″E | |

| – E24, 4 miles (6.5 km) northwest of Poryadino, at 55°20’58.31″N, 36°28’50.28″E | ||

| – E31, 6 miles (9.6 km) north of Nudol Sharino, at 56° 9’0.18″N, 36°30’13.08″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| – E33, east of Klin, at 56°20’30.03″N, 36°47’35.21″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| Gazelle (SH-08/ABM-3) | – South of Ashcherino, at 55°34’40.06″N, 37°46’17.89″E | |

| – 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Kaliningrad, at 55°52’41.63″N, 37°53’37.51″E | ||

| – 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Kartmazovo, at 55°37’31.81″N, 37°23’19.99″E | ||

| – Korostovo, at 55°54’6.00″N, 37°18’28.33″E | ||

| – 6 miles (9.6 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’50.69″N, 37°47’12.01″E | ||

| Radar** | ||

| Pill Box (Don-2N) | – 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’23.48″N, 37°46’12.51″E | |

| To view satellite images of all these sites, click here. * There are unconfirmed rumors that the Gorgon interceptors have been removed from the system. ** Other forward-based early-warning radars are not included in this overview. Two older radars (Dog House and Cat House) are no longer operational. |

||

Now history repeats itself, but the table has been turned. Today it is the United States building a limited missile defense system (more capable than the Soviet system, but focused on “rogue” state missiles), and it is the Russians who say they need to target it to maintain the effectiveness of their deterrent. The Cold War may be over, but military and policy planners in both countries still think in Cold War terms.

Russia’s Real Concerns Today

Most of the current debate has focused on whether the missile defense system could disrupt Russia’s deterrent against the United States. Although this may be a concern to Russian planners in the long run, their objections probably have more to do with the capability of the system to disrupt limited strikes against France or the United Kingdom. Russian nuclear strike plans against each of those smaller nuclear powers probably include only a few ICBMs, but their flight path would take them right over the planned interceptors (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: |

|

|

The Russian objections to the proposed US anti-ballistic missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic seem more linked to potential Russian strike plans against British and French nuclear forces than to strike plans against the United States. The trajectories for a hypothetical ICBM attack against French and British nuclear submarines bases pass over the proposed U.S. missile defense system in Europe. |

Russian planners are probably also thinking ahead. By 2015, under current plans, Russia’s ICBM force is expected to have declined from about 480 missiles today to approximately 150. Significantly less than the 450 the United States plans to retain. This, of course, will have no real implications for Russia’s security, but for Russian planners it means that a European ballistic missile defense system with 10 interceptors (that could quickly be expanded) and 21 interceptors at Fort Greely in Alaska (and silos already dug for more) suddenly doesn’t seem so limited anymore. Indeed, if Russia’s statements about targeting a future missile defense system in Europe are genuine, then the U.S. interceptors in Alaska are probably already targeted by Russian missiles.

Implications

There’s probably a fair amount of chest beating in the Russian statements, especially because Russia has little to gain from antagonistic relations with the West in the long run. Putin’s recent “offer” to include Russian radars in the Western defense plans suggests he is trying to find a way out of the stalemate, although not necessarily the way out that Western governments would like to see.

It would, of course, be much simpler if the Russians “just got over it” and accepted Western missile defenses as a fact of life. But they haven’t, and there are clear signs that U.S. missile defense plans have already influenced Russian military planning. An eerie feeling is emerging in Washington that the Russian “experiment” may be over and that Russia, instead of becoming a full partner or a full enemy, is entering a new assertive period intent on acting as a counterbalance to current U.S. foreign policy. That may not necessarily be a bad thing, unless of course it plays out in the form of military posturing.

Western claims that Russia has nothing to fear, although genuine, miss the point: They apparently fear something enough to publicly use it to underscore their own capability. East and West need to figure out what has gone wrong and how to get out of this mess before strategic antagonism becomes a prominent policy feature for the long haul. The fact that we’re even having this debate nearly two decades after the Cold War ended shows that both countries have failed miserably to move beyond Cold War posturing and planning principles.

Background: The Protection Paradox | Russian Nuclear Forces, 2007 | Pavel Podvig’s Analysis

China Reorganizes Northern Nuclear Missile Launch Sites

|

|

A dozen trucks identified at possible missile launch sites near Delingha in the northern parts of central China resemble the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile launcher. If correct, about a third of China’s DF-21 inventory is deployed within striking distance of Russian ICBM fields. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

China has significantly reorganized facilities believed to be launch sites for nuclear ballistic missiles near Delingha in the northern parts of Central China, according to commercial satellite images analyzed by the Federation of American Scientists.

The images indicate that older liquid-fueled missiles previously thought to have been deployed in the area may have been replaced with newer solid-fueled missiles. From the sites, the missiles are within range of three Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) fields and a bomber base in the southern parts of central Russia.

Analysis of Changes

The Chinese launch sites, which are located at an elevation of approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 meters), are in an area that for years has been rumored to be a deployment area for liquid-fueled DF-4 long-range nuclear ballistic missiles. In November 2006, FAS and NRDC published Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning, which used satellite images to describe the two launch sites. Several other apparent sites nearby did not have any infrastructure and many appeared abandoned.

|

|

|

|

The launch sites are located at approximately 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) on the slopes of this mountain range north of Delingha. This image (used with permission) was shot approximately six miles (10 kilometers) from Delingha. |

The southern launch site has changed most dramatically. In late-2005, the site had what appeared to be a large missile garage, approximately 40 small buildings (possibly crew quarters), and more than half a dozen service trucks. A gate was also visible. In the new image from late-2006, all of those features are gone with only a single service truck visible on the launch pad, and the access road appears to have been paved (see below).

|

|

|

|

The southern launch site at Delingha (37°24’27.47″N, 97° 3’21.18″E) changed dramatically between late-2005 (left) and late-2006. All buildings were been removed and only a few small trucks remain. The 250-feet (80-meters) launch pad and the access roads have been paved. |

The second launch site some 2.5 miles (4.3 km) to the north has also changed significantly, but here operations appear to have increased. In late-2005, this site included what appeared to be a missile garage, an underground facility, approximately 15 buildings, and less than a dozen service trucks of various sizes. The new satellite image from late-2006, however, shows that the large garage has been removed, the number of buildings nearly doubled, the access roads paved, and work appears to be in progress next to the underground facility (see below).

|

|

|

|

The northern primary launch site has been expanded significantly between late-2005 (left) and late-2006. Numerous new buildings have been erected, the access roads have been paved, work appears to be in progress next to the underground facility, and six 13-meter trucks that resemble launchers for the DF-21 MRBM are clearly visible on the launch pad. Check it out on Google Earth. |

Most interestingly, clearly visible are eight 13-meter trucks lined up on the launch pad. The satellite image is not of high enough resolution to identify the trucks and their features with certainty, but they strongly resemble the six-axle transport erector launchers (TELs) in use with the 10-meter DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile. A vague line across the trailer two-thirds toward the rear resembles the position of the hydraulic pumps used to erect the missile canister to a vertical position.

|

|

|

|

Possible DF-21 launchers are also visible at several of a dozen smaller possible launch sites. This one, north of the main site (Site 2), has also been upgraded with a new building. |

Changes to Other Delingha Sites

The two launch sites described above are the most actively visible in the satellite images. But there are more sites that appear to be involved in missile operations. North along the main road is what appears to be five smaller dispersed parking or launch platforms. None of these sites had any vehicles or infrastructure visible in 2005, but the new image shows one 13-meter truck present at four of the five sites. One of the sites appears to be upgrading with new access roads, a building, and half a dozen service vehicles (see right).

Further to the west, approximately 10 miles (17 km) from site 1 and 2, is another road leading north into the mountains. Along this road, another eight possible dispersal launch sites are visible. No 13-meter trucks, buildings, or other vehicles are visible at these sites.

The DF-21 Medium-Range Ballistic Missile

The DF-21 is a medium-range ballistic missile estimated by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) to have a range of approximately 1,330 miles (2,150 kilometers). It is China’s first solid-fueled ballistic missile and believed to carry a single warhead with a yield of 200-300 kilotons. Full operational deployment began in 1991. The missile is approximately 33 feet (10 meters) long and launched from a six-axle transporter erect launcher (TEL). Two versions of the missile are deployed, according to the DOD. Some might have been converted to carry conventional warhead.

|

|

|

|

A DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile during calibration. |

The Defense Intelligence Agency estimated in 1996 that the DF-21 was expected to complement and possibly take over the strategic targeting role of the DF-3 by 2000. But introduction was slow. Whether this is now happening, and whether the DF-21 is also replacing DF-4s in some roles is unknown. The DOD’s annual report on China’s military power for years showed great uncertainty about the number of DF-21s, the 2006 report listing a range of 19-50 missiles on 34-38 launchers. The 2007 report, however, lists 40-50 missiles on 34-38 launchers, which suggests the DOD believes the number of missiles has increased while the number of launchers has stayed the same.

|

|

|

|

From Delingha the DF-21 is in range of northern India (including New Delhi) and three Russian ICBM fields and a bomber base. |

Uncertainties and Implications

It is important to caution that there is no information publicly available that confirms that the Delingha sites are launch sites for ballistic missiles, or that the 13-meter trucks indeed are DF-21 launchers. First, the changes at the sites may be routine because nearly all of China’s ballistic missile are mobile, and the support units are designed to follow the launchers wherever they go. Second, the rumored DF-4 deployment in the area may have been wrong, or the DF-21 may have moved in years ago but only been publicly visible now. U.S. and Russian spy satellites probably have monitored the changes at Delingha on a daily basis and provided a much more detailed understanding of what is happening at the sites.

Yet the indications that the DF-21 is deployed at Delingha appear to be strong. And if the dozen 13-meter trucks visible on the satellite images at Delingha indeed are DF-21 TELs, then 32-35 percent of China’s estimated inventory of DF-21 launchers are deployed in central China.

With a DIA-listed range of 1,330 miles (2,150 kilometers) the DF-21s would not be able to reach any U.S. bases from Delingha, but they would be able to hold at risk all of northern India including New Delhi. Moreover, and this is perhaps the most interesting implication of the discovery, DF-21s would be within range of three main Russian ICBM fields on the other side of Mongolia: the SS-25 fields near Novosibirsk and Irkutsk, the SS-18 field near Uzhur, and a Backfire bomber base at Belaya.

Whereas targeting New Delhi could be considered normal for a non-alert retaliatory posture like China’s, targeting Russian ICBM fields and air bases would be a step further in the direction of a counterforce posture. But again, it is unknown exactly what role the Delingha missiles have, and the DF-21 may not be accurate enough to pose a serious risk to hardened Russian ICBM silos. Regardless of targeting, Delingha appears to be very active.

|

|

|

|

A single B-2 stealth bomber with conventional JDAM bombs would probably be sufficient to incapacitate the Delingha missile launch sites. |

One of the most striking features about the sites is their high vulnerability to attack. All appear to be almost entirely surface-based facilities (although Site 2 has an underground structure), and a mobile missile launcher is extremely vulnerable once it has been discovered. The sites were possible DF-21 launchers were detected are located within a distance of about six miles (10 kilometers). A single high-yield nuclear warhead would probably be sufficient to neutralize the entire force visible in the images.

But an adversary might not even have to cross the nuclear threshold. A single U.S. B-2 bomber loaded with non-nuclear JDAM bombs (see this video) would probably be sufficient to neutralize the dozen launch sites seen in the images. The United States has begun to incorporate such advanced conventional weapons into its strategic strike plans to give the president “more options.” Since China has repeatedly pledged that it “will not be the first to use such [nuclear] weapons at any time and in any circumstance,” some might conclude that a conventional strike on Chinese nuclear forces would not trigger Chinese use of nuclear weapons. But whether Beijing (or anyone else) would indeed stand idle by as its nuclear forces were taken out by conventional weapons is highly questionable.

Background: Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning | Delingha on Google Earth

Article: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007

(Updated May 9, 2007)

At the beginning of 2007, Russia maintained approximately 5,600 operational nuclear warheads for delivery by ballistic missiles, aircraft, cruise missiles and torpedoes, according to the latest Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Russian Notebook, which is written by Hans M. Kristensen of FAS and Robert S. Norris of NRDC, breaks down the Russian arsenal into roughly 3,300 warheads for delivery by strategic weapon systems and 2,300 warheads for delivery by tactical systems.

In addition to operational warheads, the Notebook estimates that Russia has a stock of roughly 9,400 warheads intended as a reserve or awaiting dismantlement, for a total stockpile of approximately 15,000 warheads.

The Importance of Arms Control (Section below updated May 9, 2007)

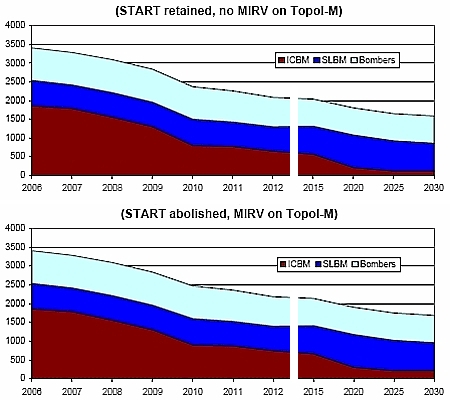

Russia and the United States apparently have decided not to extend the START agreement when it expires in 2009. The demise of the treaty will effect the number of warheads deployed on Russia’s ICBMs. Russia has already announced its intention to change the warhead loading on its Topol-M ICBMs.

Had START been extended, Russia’s arsenal of deployed strategic nuclear warheads would likely have declined to approximately 2,040 warheads by 2015 and roughly 1,590 warheads by 2030.

Once the treaty expires, however, and the Topol-M is equipped with three warheads (MIRVs, Multiple Independently Targeted Reentry Vehicles), the arsenal will reach roughly 2,210 warheads in 2015. Deployment of the silo-based Topol-M apparently will finish in 2020, in which case the warhead level will fall to approximately 1,810 warheads by 2030, depending on missile production rates for the mobile version of the Topol-M (see figure below).

|

Russian Strategic Nuclear Warheads 2006-2030 |

|

| The expiration of START in 2009 will have a significant impact on the future warhead level on Russia’s ICBMs. Beyond 2015, plans for the Russian force structure are uncertain. This projection a total of 84 Topol ICBMs on duty in 2015, and deployment of up to eight Borei-class SSBNs with 6 MIRVs per missile. The lower chart assumes up to 3 MIRVs on both silo and mobile Topol-M. |

Col. Gen. Nikolai Solovtsov, the commander of the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces (SRF), declared in December 2006 and again in May 2007 that Russia will begin to substitute the single warheads on Topol-M ICBMs with multiple warheads after START expires in 2009. He did not specify if that includes both the silo-based and mobile Topol-Ms. If only the silo-based Topol M is MIRVed, then Russia would have some 2,140 strategic warheads in 2015 and approximately 1,690 warheads deployed by 2030.

Current plans will leave Russia with roughly 146 ICBMs by 2015, a significant reduction from the 489 it had at the beginning of 2007, less than half of what the United States plans to have at that time. Russian planning also takes into consideration the Chinese posture, and the U.S. Air Force reported in March 2006 that work may be underway on a new strategic missile that can be deployed in both land-based and sea-based versions.

Russia apparently no longer believes it is necessary to maintain the same number of nuclear warheads as its potential adversaries, but still sees a significant strategic force as necessary. “For us,” President Vladimir Putin said in May 2006, “this idea of maintaining the strategic balance will mean that our strategic deterrence forces must be capable of destroying any potential aggressor, no matter what modern weapons systems this aggressor possesses.”

A Need For Additional Arms Control

Russia is currently, like the United States, making the decisions that will shape the long-term size and composition of its nuclear forces. Seventeen years after the Cold War ended, those decisions are still closely tied to the size and composition of the U.S. nuclear posture.

Putin proposed in June 2006 that START be replaced with a new treaty, and warned that “the stagnation we see today in the area of disarmament is of particular concern.” Although talks are underway with Washington on how to administer the strategic relationship after 2009, START apparently will not be extended.

The governments of both countries urgently need to articulate and decide on a new phase of arms control that will replace the open-ended, ad hoc nuclear planning of today with a framework for how to get to very low numbers with the medium-term goal of concluding the nuclear era.

Background: Russian Nuclear Forces 2007 | Status of World Nuclear Forces |

Nuclear Missile Testing Galore

(Updated January 3, 2007)

(Updated January 3, 2007)

North Korea may have gotten all the attention, but all the nuclear weapon states were busy flight-testing ballistic missiles for their nuclear weapons during 2006. According to a preliminary count, eight countries launched more than 28 ballistic missiles of 23 types in 26 different events.

Unlike the failed North Korean Taepo Dong 2 launch, most other ballistic missile tests were successful. Russia and India also experienced missile failures, but the United States demonstrated a very reliable capability including the 117th consecutive successful launch of the Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile.

The busy ballistic missile flight testing represents yet another double standard in international security, and suggests that initiatives are needed to limit not only proliferating countries from developing ballistic missiles but also find ways to curtail the programs of the existing nuclear powers.

The ballistic missile flight tests involved weapons ranging from 10-warhead intercontinental ballistic missiles down to single-warhead short-range ballistic missiles. Most of the flight tests, however, involved long-range ballistic missiles and the United States, Russia and France also launched sea-launched ballistic missiles (see table below).

|

Ballistic Missile Tests |

||

| Date | Missile | Remarks |

| China | ||

| 5 Sep | 1 DF-31 ICBM |

From Wuzhai, impact in Takla Makan Desert. |

| France | ||

| 9 Nov | 1 M51 SLBM | From Biscarosse (CELM facility), impact in South Atlantic. |

| India | ||

| 13 Jun | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| 9 Jul | 1 Agni III IRBM |

From Chandipur. Failed. |

| 20 Nov | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| Iran** | ||

| 23 May | 1 Shahab 3D MRBM |

From Emamshahr. |

| 3 Nov | 1 Shahab 3 MRBM, as well as “dozens” of Shahab 2, Scud B and other SRBMs |

Part of the Great Prophet 2 exercise. |

| North Korea*** | ||

| 4 Jul | 1 Taepo Dong 2 ICBM and 6 Scud C and Rodong SRBMs |

From Musudan-ri near Kalmo. ICBM failed. |

| Pakistan | ||

| 16 Nov | 1 Ghauri MRBM |

From Tilla? |

| 29 Nov | 1 Hatf-4 (Shaheen-I) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| 9 Dec | 1 Haft-3 (Ghaznavi) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| Russia | ||

| 28 Jul | 1 SS-18 ICBM | Attempt to launch satellite, but technically an SS-18 flight test (see comments below). |

| 3 Aug | 1 Topol (SS-25) ICBM |

From Plesetsk, impact on Kura range. |

| 7 Sep | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Sep | 1 SS-N-23 SLBM |

From K-84 (Delta IV) at North Pole, impact on Kizha range. |

| 10 Sep | 1 SS-N-18 SLBM |

From Delta III in Pacific, impact on Kizha range. |

| 25 Oct | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Nov | 1 SS-19 ICBM |

From Silo in Baykonur, impact on Kura range. |

| 21 Dec | 1 SS-18 ICBM |

From Orenburg, impact on Kura range. |

| 24 Dec | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From White Sea. Third stage failed. |

| United States | ||

| 16 Feb | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Final W87/Mk-21 SERV test flight. |

| Mar/Apr | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From SSBN. |

| 4 Apr | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact near Guam. Extended-range, single-warhead flight test. |

| 14 Jun | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead payload. |

| 20 Jul | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead flight test. Launched by E-6B TACAMO airborne command post. |

| 21 Nov | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From USS Maryland (SSBN-738) off Florida, impact in South Atlantic. |

| * Unreported events may add to the list. ** Iran does not have nuclear weapons but is suspected of pursuing nuclear weapons capability. *** It is unknown if North Korea has developed a nuclear reentry vehicle for its ballistic missiles. |

||

The Putin government’s reaffirmation of the importance of strategic nuclear forces to Russian national security was tainted by the failure of three consecutive launches of the new Bulava missile, but tests of five other missile types shows that Russia still has effective missile forces.

Along with China, Russia’s efforts continue to have an important influence on U.S. nuclear planning, and the eight Minuteman III and Trident II missiles launched in 2006 were intended to ensure a nuclear capability second to none. The first ICBM flight-test signaled the start of the deployment of the W87 warhead on the Minuteman III force.

China’s launch of the (very) long-awaited DF-31 ICBM and India’s attempts to test launch the Agni III raised new concerns because of the role the weapons likely will play in the two countries’ targeting of each other. But during a visit to India in June 2006, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Peter Pace, downplayed at least the Indian issue saying other countries in the region also have tested missiles. In a statement that North Korea would probably find useful to use, Gen. Pace explained that “the fact that a country is testing something like a missile is not destabilizing” as long as it is “designed for defense, and then are intended for use for defense, and they have competence in their ability to use those weapons for defense, it is a stabilizing event.”

But since all “defensive” ballistic missiles have very offensive capabilities, and since no nation plans it defense based on intentions and statements anyway but on the offensive capabilities of potential adversaries, Gen. Pace’s explanation seemed disingenuous and out of sync with the warnings about North Korean, Iranian and Chinese ballistic missile developments.

The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) seeks to limit the proliferation of ballistic missiles, but that vision seems undercut by the busy ballistic missile launch schedule demonstrated by the nuclear weapon states in 2006. Some MTCR member countries have launched the International Code of Conduct Against Ballistic Missile Proliferation initiative in an attempt to establish a norm against ballistic missiles, and have called on all countries to show greater restraint in their own development of ballistic missiles capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction and to reduce their existing missile arsenals if possible.

All the nuclear weapons states portray their own nuclear ballistic missile developments as stabalizing and fully in compliance with their pledge under the Non-Proliferation Treaty to pursue nuclear disarmament in good faith. But fast-flying ballistic missiles are inherently destablizing because of their vulnerability to attack may trigger use early on in a conflict. And the busy missile testing in 2006 suggests that the “good faith” is wearing a little thin.

US Air Force Publishes New Missile Threat Assessment

The Air Force has published a new report about the threat from ballistic and cruise missiles. The new report, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, presents the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) assessment of current and emerging weapon systems deployed or under development by Russia, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iran, Syria and others.

The Air Force has published a new report about the threat from ballistic and cruise missiles. The new report, Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat, presents the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s (NASIC) assessment of current and emerging weapon systems deployed or under development by Russia, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, Iran, Syria and others.

Among the news in the report is a different and higher estimate for China’s future nuclear arsenal than was presented in the previous NASIC report from 2003. Whereas the previous assessment stated that China in 15 years will have 75-100 warheads on ICBMs capable of reaching the United States, the 2006 report states that this number will be “well over 100” warheads. NASIC also believes that a new Chinese cruise missile under development will have nuclear capability.

Also new is that NASIC reports that the Indian Agni I ballistic missile has not yet been deployed despite claims by the Indian government that the weapon was “inducted” into the Indian Army in 2004. Contrary to claims made by some media and experts, the NASIC report states that the Indian Bramos cruise missile does not have a nuclear capability. The Babur cruise missile under development by Pakistan, however, is assessed to have a nuclear capability.

A copy of the report, which was published in March 2006 and recently obtained by the Federation of American Scientists, is available in full along with previous versions here.

Nuclear Weapons Reassert Russian Might, Sort Of

A new review of Russian nuclear forces published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists says that the Kremlin appears to be attempting to reassert its nuclear strength after years of decline in order to underscore Russia’s status as a powerful nation. Large-scale exercises have been reinstated and modernizations of nuclear forces continue with reports about a new maneuverable warhead and the mobile version of the SS-27 (Topol-M) expected to become operational later this year.

A new review of Russian nuclear forces published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists says that the Kremlin appears to be attempting to reassert its nuclear strength after years of decline in order to underscore Russia’s status as a powerful nation. Large-scale exercises have been reinstated and modernizations of nuclear forces continue with reports about a new maneuverable warhead and the mobile version of the SS-27 (Topol-M) expected to become operational later this year.

Yet the reassertion is done with fewer strategic warheads than at any time since the mid-1970s, approximately 3,500 operational strategic warheads. The number of operational non-strategic nuclear weapons has been cut by more than half to approximately 2,300 warheads.

Moreover, during 2005, Russia’s 12 nuclear ballistic missile submarines only conducted three deterrent patrols. This is a slightly better performance than in 2002 when no patrols were made, but a far cry from the 1980s when Soviet ballistic missile submarines conducted 50-100 deterrent patrols each year.

Article: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2006

Background: Russian Submarine Patrols

Missions for Nuclear Weapons after the Cold War

This report (PDF) examines currently proposed nuclear missions and finds that the United States is witnessing the end of a long process of having nuclear weapons be displaced by advanced conventional alternatives.

The most challenging nuclear mission is a holdover from the Cold War: to be able to carry out a disarming first strike against Russian central nuclear forces. Only if the US and Russia abandon this mission will meaningful reductions in the two largest arsenals be possible.