The Untold Story of the CHIPS and Science Act

Daniel Goetzel is currently a Practitioner-in-Residence at Harvard Kennedy School’s Reimagining the Economy project. Prior to his work at Harvard, he was Program Director of the National Science Foundation’s Technology, Innovation and Partnerships Directorate. He also authored a Day One policy memo focused on fostering the next generation of small business leaders. The piece that follows is an oral history of the establishment of the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines Program – a key part of the historic CHIPS and Science Act.

The CHIPS and Science Act was signed into law on August 9, 2022. It was the largest technology and industrial policy program in modern history, investing hundreds of billions of dollars into research, manufacturing, and American competitiveness.

When the government announces flagship programs like this, a bill signing or a ribbon cutting is often all the public sees. They rarely see the quiet, often messy work that goes into creating, passing, and implementing a major piece of legislation. This piece is an attempt to change that by digging into the CHIPS and Science Act and the NSF Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines) program.

While much of the media coverage and debate around the bill has focused on the multi-billion dollar incentives to large corporations like TSMC, Samsung, and Intel, the CHIPS and Science Act had a complementary focus and multi-billion dollar investment in R&D and economic development, spanning everything from chips and AIto battery storage and biotech. One investment vehicle that came out of the bill was the National Science Foundation’s Regional Innovation Engines, an up to $1.6B program aiming to create the industries of the future in communities that were historically ignored in past tech booms.

Contribute your own story about Regional Innovation Engines here.

Bridging Innovation and Expertise: Connecting Federal Talent to America’s Tech Ecosystems

The semiconductor shortfall during the COVID-19 pandemic spotlighted the consequences of underinvesting in critical technology ecosystems. This wake-up call, following years of advocacy and growing consensus, spurred bipartisan action through the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, which made transformative investments in the semiconductor industry as well as future-focused programs like the Economic Development Administration’s Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs (Tech Hubs) – a program I helped launch as EDA’s chief of staff – and the National Science Foundation’s Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines). These latter two initiatives – Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – are catalyzing dynamic innovation ecosystems across the country, advancing technologies critical to our national security and economic competitiveness while spurring broad-based regional economic growth.

But as these innovation ecosystems grow, so too does their demand for talent. Across these ecosystems, there is a need to fill specialized positions essential to their success. At the same time, we’re witnessing an exodus of talent from the federal service – scientists, engineers, technologists, workforce experts, and skilled generalists – professionals whose expertise could be lost altogether if not effectively deployed. While these departures are deeply troubling for government operations and the services Americans rely on, we face three pressing imperatives: preserving specialized knowledge, responding to the human impact on individuals suddenly without work, and addressing critical talent needs among these tech regions. During my time as a Senior Fellow at FAS, I’m focused on building bridges that connect these experienced professionals with innovation ecosystems where they can continue to apply their hard-won expertise in service of important national priorities.

Innovation ecosystems: What are they?

Both NSF Engines and Tech Hubs seek to advance critical and emerging technologies, but each focuses on different stages of technological advancement – NSF Engines on the research and development and early translation of technologies, while Tech Hubs comes in to support scaling and commercializing these technologies to achieve global competitiveness.

Together, they’re advancing our capabilities in 10 key technology areas:

- Advanced manufacturing and robotics

- Advanced materials

- Artificial intelligence

- Biotechnology

- Communications technology and immersive technology

- Cybersecurity and data storage

- Disaster risk and resilience

- Energy technology

- Quantum

- Semiconductors and advanced computing.

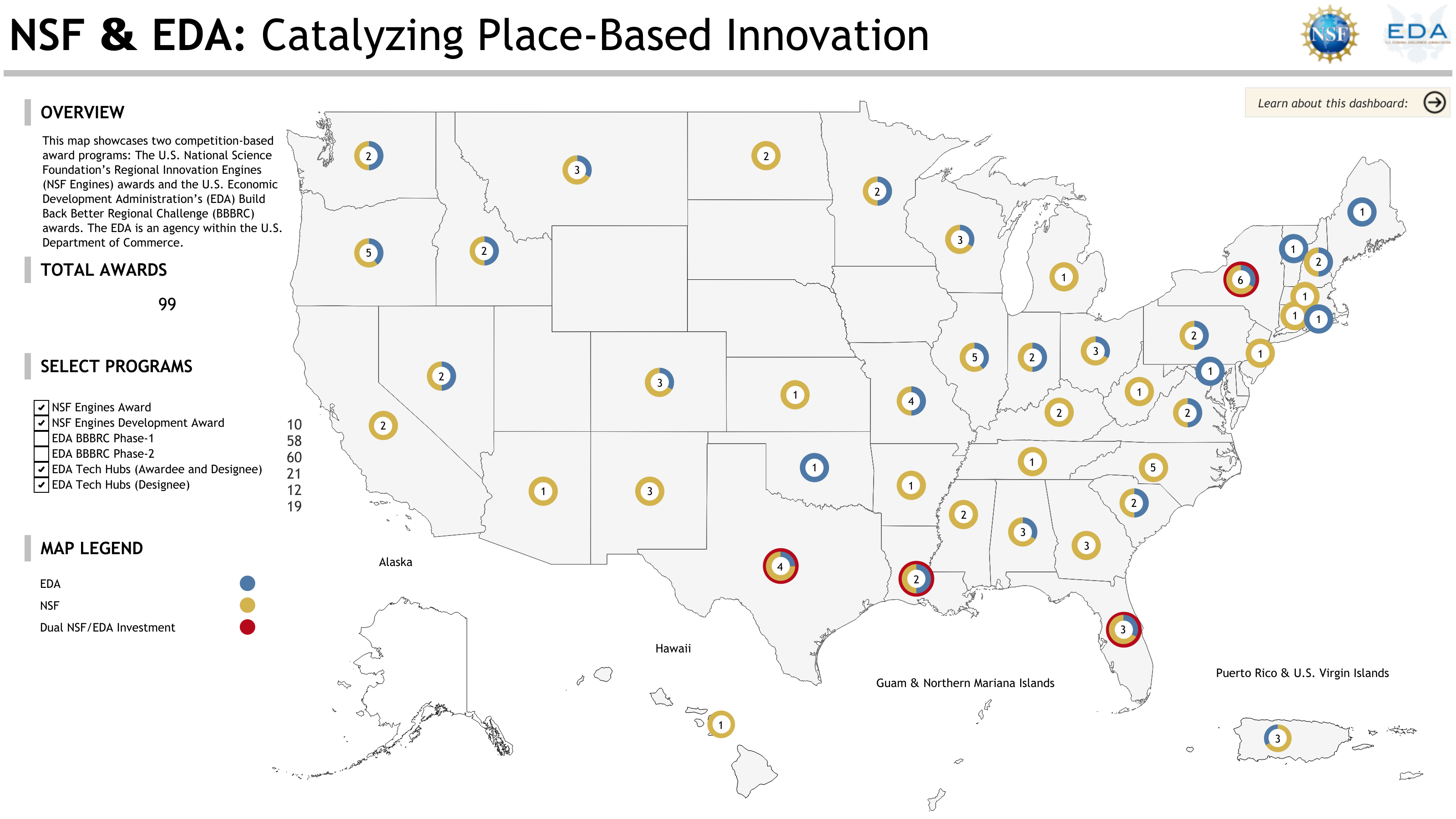

This geographically distributed innovation model is taking root across America, with 31 designated Tech Hubs and 10 NSF Engines receiving between approximately $15 million to $50 million each – not to mention the dozens of other innovation ecosystems that received development grants to continue to build their ecosystem strategies – spanning the majority of states across the country.

Map of NSF Engines & EDA BBBRC via NSF on Tableau

Note: NSF’s interactive map also includes the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, a program of the Economic Development Administration, that includes many innovation ecosystems that span the country as well. In this version, only Tech Hubs and NSF Engines are demarcated on the map.

The strength of these innovation ecosystems lies in their coalition approach, which brings together industry, start-ups, research universities, community colleges, economic and workforce development organizations, community-based nonprofits, and entrepreneurial ecosystem builders. As these ecosystems scale, this broad spectrum of stakeholders need talent to fill a variety of roles: lab scientists, engineers, technicians, partnership managers, business support and entrepreneurship program staff, workforce development program managers, and other specialized industry and ecosystem builder roles. Where will some of this talent come from? I believe part of the answer lies in the talented professionals departing federal service.

The federal service: Who are they?

Since January 2025, tens of thousands of federal workers have left the federal government, in addition to thousands of contractors who have supported government services. They come from agencies where they worked in areas helpful to innovation ecosystems, like the National Institutes of Health (helpful for biotech-focused ecosystems) to the Department of Labor (helpful for workforce development strategizing). These individuals have managed multimillion-dollar grant programs, provided expert technical analyses and developed best practices across every area you can think of, and navigated complex stakeholder networks. Many already live in or near regions with emerging innovation ecosystems, given the distributed nature of federal agencies, and others are willing to relocate for the right mission-driven opportunity, potentially even back to places they call home. Their early involvement in these innovation ecosystems would help build the momentum needed for technological breakthroughs and sustained growth, in turn leading to more job creation for others at the local and regional level.

The initiative

With FAS’s support, I am launching an initiative to connect scientists, engineers, technologists, economic and workforce development practitioners, program manager extraordinaires, and other professionals who recently departed federal service with emerging innovation ecosystems across the country that need their expertise.

We’re talking directly with Tech Hubs and NSF Engines communities to identify immediate and near-term talent needs within their leadership teams, across federally funded Tech Hub and NSF Engine component projects, and among consortium stakeholders. Simultaneously, we are engaging displaced federal workers and contractors through job fairs and direct outreach to understand their skillsets, career interests, and location preferences. To help both innovation ecosystems and these workers, we aim to showcase opportunities across innovation ecosystems, facilitate direct matchmaking to expedite hiring, and create additional resources tailored to the needs of these professionals and innovation ecosystems.

This is an opportunity for innovation ecosystems to take advantage of the availability of mission-driven professionals who have transferable skills to meet the needs of these regions. At the same time, this allows former federal professionals to continue meaningful, public-purpose work that contributes to America’s technological leadership in a new capacity.

It is to our national peril if we do not set up these innovation ecosystems to succeed. And it is also to our peril if we do not leverage the thousands of years of collective experience these former feds have to offer. This FAS initiative wants to see regions, people, and the country succeed, and is doing so by addressing critical talent gaps in these strategically imperative innovation ecosystems, offering pathways for continued public-purpose impact, and ensuring the nation as a whole does not lose valuable expertise.

What you can do

We are excited to share more information soon on these available opportunities and how federal workers can plug in. In the meantime, if you are an innovation ecosystem – even outside of Tech Hubs and NSF Engines – please do reach out to learn more or share open roles. If you are a federal worker, fill out this interest form, and we’ll add you to the list to receive more information as it becomes available. And if you have any thoughts to offer on this initiative, we are all ears.

As the design of Tech Hubs and NSF Engines shows us, it takes a coalition of committed organizations and individuals to achieve big, but necessary, goals.

Maryam Janani-Flores (mjananiflores@fas.org) is a Senior Fellow at FAS and former chief of staff at the U.S. Economic Development Administration.

Strategies to Accelerate and Expand Access to the U.S. Innovation Economy

In 2020, we outlined a vision for how the incoming presidential administration could strengthen the nation’s innovation ecosystem, encouraging the development and commercialization of science and technology (S&T) based ventures. This vision entailed closing critical gaps from lab to market, with an emphasis on building a broadly inclusive pipeline of entrepreneurial talent while simultaneously providing key support in venture development.

During the intervening years, we have seen extraordinary progress, in good part due to ambitious legislation. Today, we propose innovative ways that the federal government can successfully build on this progress and make the most of new programs. With targeted policy interventions, we can efficiently and effectively support the U.S. innovation economy through the translation of breakthrough scientific research from the lab to the market. The action steps we propose are predicated on three core principles: inclusion, relevance, and sustainability. Accelerating our innovation economy and expanding access to it can make our nation more globally competitive, increase economic development, address climate change, and improve health outcomes. A strong innovation economy benefits everyone.

Challenge

Our Day One 2020 memo began by pitching the importance of innovation and entrepreneurship: “Advances in scientific and technological innovations—and, critically, the ability to efficiently transform breakthroughs into scalable businesses—have contributed enormously to American economic leadership over the past century.” Now, it is widely recognized that innovation and entrepreneurship are key to both global economic leadership and addressing the challenges of changing climate. The question is no longer whether we must innovate but rather how effectively we can stimulate and expand a national innovation economy.

Since 2020, the global and U.S. economies have gone through massive change and uncertainty. The Global Innovation Index (GII) 2023 described the challenges involved in its yearly analysis of monitoring global innovation trends amid uncertainty brought on by a sluggish economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, elevated interest rates, and geopolitical tensions. Innovation indicators like scientific publications, research and development (R&D), venture capital (VC) investments, and the number of patents rose to historic levels, but the value of VC investment declined by close to 40%. As a counterweight to this extensive uncertainty, the GII 2023 described the future of S&T innovation and progress as “the promise of Digital Age and Deep Science innovation waves and technological progress.”

In the face of the pressures of global competitiveness, societal needs, and climate change, the clear way forward is to continue to innovate based on scientific and technical advancements. Meeting the challenges of our moment in history requires a comprehensive and multifaceted effort led by the federal government with many public and private partners.

Grow global competitiveness

Around the world, countries are realizing that investing in innovation is the most efficient way to transform their economies. In 2022, the U.S. had the largest R&D budget internationally, with spending growing by 5.6%, but China’s investment in R&D grew by 9.8%. For the U.S. to remain a global economic leader, we must continue to invest in innovation infrastructure, including the basic research and science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education that underpins our leadership, while we grow our investments in translational innovation. This includes reframing how existing resources are used as well as allocating new spending. It will require a systems change orientation and long-term commitments.

Increase economic development

Supporting and growing an innovation economy is one of our best tools for economic development. From place-based innovation programs to investment in emerging research institutions (ERIs) and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs) to training S&T innovators to become entrepreneurs in I-Corps™, these initiatives stimulate local economies, create high-quality jobs, and reinvigorate regions of the country left behind for too long.

Address climate change

In 2023, for the first time, global warming exceeded 1.5°C for an entire year. It is likely that all 12 months of 2024 will also exceed 1.5°C above pre-industrial temperatures. Nationally and internationally, we are experiencing the effects of climate change; climate mitigation, adaptation, and resilience solutions are urgently needed and will bring outsized economic and social impact.

Improve U.S. health outcomes

The COVID-19 pandemic was devastating, particularly impacting underserved and underrepresented populations, but it spurred unprecedented medical innovation and commercialization of new diagnostics, vaccines, and treatments. We must build on this momentum by applying what we’ve learned about rapid innovation to continue to improve U.S. health outcomes and to ensure that our nation’s health care needs across regions and demographics are addressed.

Make innovation more inclusive

Representational disparities persist across racial/ethnic and gender lines in both access to and participation in innovation and entrepreneurship. This is a massive loss for our innovation economy. The business case for broader inclusion and diversity is growing even stronger, with compelling data tracking the relationship between leadership diversity and company performance. Inclusive innovation is more effective innovation: a multitude of perspectives and lived experiences are required to fully understand complex problems and create truly useful solutions. To reap the full benefits of innovation and entrepreneurship, we must increase access and pathways for all.

Opportunity

With the new presidential administration in 2025, the federal government has a renewed opportunity to prioritize policies that will generate and activate a wave of powerful, inclusive innovation and entrepreneurship. Implementing such policies and funding the initiatives that result is crucial if we as a nation are to successfully address urgent problems such as the climate crisis and escalating health disparities.

Our proposed action steps are predicated on three core principles: inclusion, relevance, and sustainability.

Inclusion

One of this nation’s greatest and most unique strengths is our heterogeneity. We must leverage our diversity to meet the complexity of the substantial social and economic challenges that we face today. The multiplicity of our people, communities, identities, geographies, and lived experiences gives the U.S. an edge in the global innovation economy: When we bring all of these perspectives to the table, we better understand the challenges that we face, and we are better equipped to innovate to meet them. If we are to harness the fullness of our nation’s capacity for imagination, ingenuity, and creative problem-solving, entrepreneurship pathways must be inclusive, equitable, and accessible to all. Moreover, all innovators must learn to embrace complexity, think expansively and critically, and welcome perspectives beyond their own frame of reference. Collaboration and mutually beneficial partnerships are at the heart of inclusive innovation.

Relevance

Innovators and entrepreneurs have the greatest likelihood of success—and the greatest potential for impact—when their work is purpose-driven, nimble, responsive to consumer needs, and adaptable to different applications and settings. Research suggests that “breakthrough innovation” occurs when different actors bring complementary and independent skills to co-create interesting solutions to existing problems. Place-based innovation is one strategy to make certain that technology development is grounded in regional concerns and aspirations, leading to better outcomes for all concerned.

Sustainability

Multiple layers of sustainability should be integrated into the innovation and entrepreneurship landscape. First and most salient is supporting the development of innovative technologies that respond to the climate crisis and bolster national resilience. Second is encouraging innovators to incorporate sustainable materials and processes in all stages of research and development so that products benefit the planet and risks to the environment are mitigated through the manufacturing process, whether or not climate change is the focus of the technology. Third, it is vital to prioritize helping ventures develop sustainable business models that will result in long-term viability in the marketplace. Fourth, working with innovators to incorporate the potential impact of climate change into their business planning and projections ensures they are equipped to adapt to changing needs. All of these layers contribute to sustaining America’s social well-being and economic prosperity, ensuring that technological breakthroughs are accessible to all.

Proposed Action

Recommendation 1. Supply and prepare talent.

Continuing to grow the nation’s pipeline of S&T innovators and entrepreneurs is essential. Specifically, creating accessible entrepreneurial pathways in STEM will ensure equitable participation. Incentivizing individuals to become innovators-entrepreneurs, especially those from underrepresented groups, will strengthen national competitiveness by leveraging new, untapped potential across innovation ecosystems.

Expand the I-Corps model

By bringing together experienced industry mentors, commercial experts, research talent, and promising technologies, I-Corps teaches scientific innovators how to evaluate whether their innovation can be commercialized and how to take the first practical steps of bringing their product to market. Ten new I-Corps Hubs, launched in 2022, have expanded the network of engaged universities and collaborators, an important step toward growing an inclusive innovation ecosystem across the U.S.

Interest in I-Corps far outpaces current capacity, and increasing access will create more expansive pathways for underrepresented entrepreneurs. New federal initiatives to support place-based innovation and to grow investment at ERIs and MSIs will be more successful if they also include lab-to-market training programs such as I-Corps. Federal entities should institute policies and programs that increase awareness about and access to sequenced venture support opportunities for S&T innovators. These opportunities should include intentional “de-risking” strategies through training, advising, and mentoring.

Specifically, we recommend expanding I-Corps capacity so that all interested participants can be accommodated. We should also strive to increase access to I-Corps so that programs reach diverse students and researchers. This is essential given the U.S. culture of entrepreneurship that remains insufficiently inclusive of women, people of color, and those from low-income backgrounds, as well as international students and researchers, who often face barriers such as visa issues or a lack of institutional support needed to remain in the U.S. to develop their innovations. Finally, we should expand the scope of what I-Corps offers, so that programs provide follow-on support, funding, and access to mentor and investor networks even beyond the conclusion of initial entrepreneurial training.

I-Corps has already expanded beyond the National Science Foundation (NSF) to I-Corps at National Institutes of Health (NIH), to empower biomedical entrepreneurs, and Energy I-Corps, established by the Department of Energy (DOE) to accelerate the deployment of energy technologies. We see the opportunity to grow I-Corps further by building on this existing infrastructure and creating cohorts funded by additional science agencies so that more basic research is translated into commercially viable businesses.

Close opportunity gaps by supporting emerging research institutions (ERIs) and Minority-Serving Institutions (MSIs)

ERIs and MSIs provide pathways to S&T innovation and entrepreneurship, especially for individuals from underrepresented groups. In particular, a VentureWell-commissioned report identified that “MSIs are centers of research that address the unique challenges and opportunities faced by BIPOC communities. The research that takes place at MSIs offers solutions that benefit a broad and diverse audience; it contributes to a deeper understanding of societal issues and drives innovation that addresses these issues.”

The recent codification of ERIs in the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act pulls this category into focus. Defining this group, which comprises thousands of higher education institutions, was the first step in addressing the inequitable distribution of federal research funding. That imbalance has perpetuated regional disparities and impacted students from underrepresented groups, low-income students, and rural students in particular. Further investment in ERIs will result in more STEM-trained students, who can become innovators and entrepreneurs with training and engagement. Additional support that could be provided to ERIs includes increased research funding, access to capital/investment, capacity building (faculty development, student support services), industry partnerships, access to networks, data collection/benchmarking, and implementing effective translation policies, incentives, and curricula.

Supporting these institutions—many of which are located in underserved rural or urban communities that experience underinvestment—provides an anchor for sustained talent development and economic growth.

Recommendation 2. Support place-based innovation.

Place-based innovation not only spurs innovation but also builds resilience in vulnerable communities, enhancing both U.S. economic and national security. Communities that are underserved and underinvested in present vulnerabilities that hostile actors outside of the U.S. can exploit. Place-based innovation builds resilience: innovation creates high-quality jobs and brings energy and hope to communities that have been left behind, leveraging the unique strengths, ecosystems, assets, and needs of specific regions to drive economic growth and address local challenges.

Evaluate and learn from transformative new investments

There have been historic levels of government investment in place-based innovation, funding the NSF’s Regional Innovation Engines awards and two U.S. Department of Commerce Economic Development Administration (EDA) programs: the Build Back Better Regional Challenge and Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs awards. The next steps are to refine, improve, and evaluate these initiatives as we move forward.

Unify the evaluation framework, paired with local solutions

Currently, evaluating the effectiveness and outcomes of place-based initiatives is challenging, as benchmarks and metrics can vary by region. We propose a unified framework paired with solutions locally identified by and tailored to the specific needs of the regional innovation ecosystem. A functioning ecosystem cannot be simply overlaid upon a community but must be built by and for that community. The success of these initiatives requires active evaluation and incorporation of these learnings into effective solutions, as well as deep strategic collaboration at the local level, with support and time built into processes.

Recommendation 3. Increase access to financing and capital.

Funding is the lifeblood of innovation. S&T innovation requires more investment and more time to bring to market than other types of ventures, and early-stage investments in S&T startups are often perceived as risky by those who seek a financial return. Bringing large quantities of early-stage S&T innovations to the point in the commercialization process where substantial private capital takes an interest requires nondilutive and patient government support. The return on investment that the federal government seeks is measured in companies successfully launched, jobs created, and useful technologies brought to market.

Disparities in access to capital by companies owned by women and underrepresented minority founders are well documented. The federal government has an interest in funding innovators and entrepreneurs from many backgrounds: they bring deep and varied knowledge and a multitude of perspectives to their innovations and to their ventures. This results in improved solutions and better products at a cheaper price for consumers. Increasing access to financing and capital is essential to our national economic well-being and to our efforts to build climate resilience.

Expand SBIR/STTR access and commercial impact

The SBIR and STTR programs spur innovation, bolster U.S. economic competitiveness, and strengthen the small business sector, but barriers persist. In a recent third-party assessment of the SBIR/STTR program at NIH, the second largest administrator of SBIR/STTR funds, the committee found outreach from the SBIR/STTR programs to underserved groups is not coordinated, and there has been little improvement in the share of applications from or awards to these groups in the past 20 years. Further, NIH follows the same processes used for awarding R01 research grants, using the same review criteria and typically the same reviewers, omitting important commercialization considerations.

To expand access and increase the commercialization potential of the SBIR/STTR program, funding agencies should foster partnerships with a broader group of organizations, conduct targeted outreach to potential applicants, offer additional application assistance to potential applicants, work with partners to develop mentorship and entrepreneur training programs, and increase the percentage of private-sector reviewers with entrepreneurial experience. Successful example programs of SBIR/STTR support programs include the NSF Beat-The-Odds Boot Camp, Michigan’s Emerging Technologies Fund, and the SBIR/STTR Innovation Summit.

Provide entrepreneurship education and training

Initiatives like NSF Engines, Tech Hubs, Build-Back-Better Regional Challenge, the Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) Capital Challenge, and the Small Business Administration (SBA) Growth Accelerator Fund expansion will all achieve more substantial results with supplemental training for participants in how to develop and launch a technology-based business. As an example of the potential impact, more than 2,500 teams have participated in I-Corps since the program’s inception in 2012. More than half of these teams, nearly 1,400, have launched startups that have cumulatively raised $3.16 billion in subsequent funding, creating over 11,000 jobs. Now is an opportune moment to widely apply similarly effective approaches.

Launch a local investment education initiative

Angel investors are typically providing the first private funding available to S&T innovators and entrepreneurs. These very early-stage funders give innovators access to needed capital, networks, and advice to get their ventures off the ground. We recommend that the federal government expand the definition of an accredited investor and incentivize regionally focused initiatives to educate policymakers and other regional stakeholders about best practices to foster more diverse and inclusive angel investment networks. With the right approach and support, there is the potential to engage thousands more high-net-worth individuals in early-stage investing, contributing their expertise and networks as well as their wealth.

Encourage investment in climate solutions

Extreme climate-change-attributed weather events such as floods, hurricanes, drought, wildfire, and heat waves cost the global economy an average of $143 billion annually. S&T innovations have the potential to help address the impacts of climate change at every level:

- Mitigation. Promising new ideas and technologies can slow or even prevent further climate change by reducing or removing greenhouse gasses.

- Adaptation. We can adapt processes and systems to better respond to adverse events, reducing the impacts of climate change.

- Resilience. By anticipating, preparing for, and responding to hazardous events, trends, or disturbances caused by climate change, we can continue to thrive on our changing planet.

Given the global scope of the problem and the shared resources of affected communities, the federal government can be a leader in prioritizing, collaborating, and investing in solutions to direct and encourage S&T innovation for climate solutions. There is no question whether climate adaptation technologies will be needed, but we must ensure that these solutions are technologies that create economic opportunity in the U.S. We encourage the expansion and regular appropriations of funding for successful climate programs across federal agencies, including the DoE Office of Technology Transitions’ Energy Program for Innovation Clusters, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Ocean-Based Climate Resilience Accelerators program, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Climate Hubs.

Recommendation 4. Shift to a systems change orientation.

To truly stimulate a national innovation economy, we need long-term commitments in policy, practice, and regulations. Leadership and coordination from the executive branch of the federal government are essential to continue the positive actions already begun by the Biden-Harris Administration.

These initiatives include:

- Scientific integrity and evidence-based policy-making memo

- Catalyzing Clean Energy Industry Executive Order

- Implementation of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

- Advancing Biotechnology and Biomanufacturing Innovation for a Sustainable, Safe, and Secure American Bioeconomy

- Implementation of the CHIPS Act of 2022

- Advancing Women’s Health Research and Innovation

Policy

Signature initiatives like the CHIPS and Science Act, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, and the National Quantum Initiative Act are already threatened by looming appropriations shortfalls. We need to fully fund existing legislation, with a focus on innovative and translational R&D. According to a report by PricewaterhouseCoopers, if the U.S. increased federal R&D spending to 1% of GDP by 2030, the nation could support 3.4 million jobs and add $301 billion in labor income, $478 billion in economic value, and $81 billion in tax revenue. Beyond funding, we propose supporting innovative policies to bolster U.S. innovation capacity at the local and national levels. This includes providing R&D tax credits to spur research collaboration between industry and universities and labs, providing federal matching funds for state and regional technology transfer and commercialization efforts, and revising the tax code to support innovation by research-intensive, pre-revenue companies.

Practice

The University and Small Business Patent Procedures Act of 1980, commonly known as the Bayh-Dole Act, allows recipients of federal research funding to retain rights to inventions conceived or developed with that funding. The academic tech transfer system created by the Bayh-Dole Act (codified as amended at 35 U.S.C. §§ 200-212) generated nearly $1.3 trillion in economic output, supported over 4.2 million jobs, and launched over 11,000 startups. We should preserve the Bayh-Dole Act as a means to promote commercialization and prohibit the consideration of specific factors, such as price, in march-in determinations.

In addition to the continual practice and implementation of successful laws such as Bayh-Dole, we must repurpose resources to support innovation and the high-value jobs that result from S&T innovation. We believe the new administration should allocate a share of federal funding to promote technology transfer and commercialization and better incentivize commercialization activities at federal labs and research institutes. This could include new programs such as mentoring programs for researcher entrepreneurs and student entrepreneurship training programs. Incentives include evaluating the economic impact of lab-developed technology by measuring commercialization outcomes in the annual Performance Evaluation and Management Plans of federal labs, establishing stronger university entrepreneurship reporting requirements to track and reward universities that create new businesses and startups, and incentivizing universities to focus more on commercialization activities as part of promotion and tenure of faculty,

Regulations

A common cause of lab-to-market failure is the inability to secure regulatory approval, particularly for novel technologies in nascent industries. Regulation can limit potentially innovative paths, increase innovation costs, and create a compliance burden on businesses that stifle innovation. Regulation can also spur innovation by enabling the management of risk. In 1976 the Cambridge (Massachusetts) City Council became the first jurisdiction to regulate recombinant DNA, issuing the first genetic engineering license and creating the first biotech company. Now Boston/Cambridge is the world’s largest biotech hub: home to over 1,000 biotech companies, 21% of all VC biotech investments, and 15% of the U.S. drug development pipeline.

To advance innovation, we propose two specific regulatory actions:

- Climate. We recommend the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) adopt market-based strategies to help fight climate change by monitoring and regulating CO2 emissions, putting an explicit price on carbon emissions, and incentivizing businesses to find cost-effective and innovative ways to reduce those emissions.

- Health. We recommend strengthening regulatory collaboration between the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to establish a more efficient and timely reimbursement process for novel FDA-authorized medical devices and diagnostics. This includes refining the Medicare Coverage of Innovative Technologies rule and fully implementing the new Transitional Coverage for Emerging Technologies pathway to expedite the review, coverage determination, and reimbursement of novel medical technologies.

Conclusion

To maintain its global leadership role, the United States must invest in the individuals, institutions, and ecosystems critical to a thriving, inclusive innovation economy. This includes mobilizing access, inclusion, and talent through novel entrepreneurship training programs; investing, incentivizing, and building the capacity of our research institutions; and enabling innovation pathways by increasing access to capital, networks, and resources.

Fortunately, there are several important pieces of legislation recommitting the U.S. leadership to bold S&T goals, although much of the necessary resources are yet to be committed to those efforts. As a society, we benefit when federally supported innovation efforts tackle big problems that are beyond the scope of single ventures; notably, the many challenges arising from climate change. A stronger, more inclusive innovation economy benefits the users of S&T-based innovations, individual innovators, and the nation as a whole.

When we intentionally create pathways to innovation and entrepreneurship for underrepresented individuals, we build on our strengths. In the United States, our strength has always been our people, who bring problem-solving abilities from a multitude of perspectives and settings. We must unleash their entrepreneurial power and become, even more, a country of innovators..

Earlier memo contributors Heath Naquin and Shaheen Mamawala (2020) were not involved with this 2024 memo.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Policy Experiment Stations to Accelerate State and Local Government Innovation

The federal government transfers approximately $1.1 trillion dollars every year to state and local governments. Yet most states and localities are not evaluating whether the programs deploying these funds are increasing community well-being. Similarly, achieving important national goals like increasing clean energy production and transmission often requires not only congressional but also state and local policy reform. Yet many states and localities are not implementing the evidence-based policy reforms necessary to achieve these goals.

State and local government innovation is a problem not only of politics but also of capacity. State and local governments generally lack the technical capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, search for reliable evidence about programs evaluated in other contexts, and implement the evidence-based programs with the highest chances of improving outcomes in their jurisdictions. This lack of capacity severely constrains the ability of state and local governments to use federal funds effectively and to adopt more effective ways of delivering important public goods and services. To date, efforts to increase the use of evaluation evidence in federal agencies (including the passage of the Evidence Act) have not meaningfully supported the production and use of evidence by state and local governments.

Despite an emerging awareness of the importance of state and local government innovation capacity, there is a shortage of plausible strategies to build that capacity. In the words of journalist Ezra Klein, we spend “too much time and energy imagining the policies that a capable government could execute and not nearly enough time imagining how to make a government capable of executing them.”

Yet an emerging body of research is revealing that an effective strategy to build government innovation capacity is to partner government agencies with local universities on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their programs, curated syntheses of reliable evaluation evidence from other contexts, and implementation of evidence-based programs with the best chances of success. Leveraging these findings, along with recent evidence of the striking efficacy of the national network of university-based “Agriculture Experiment Stations” established by the Hatch Act of 1887, we propose a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations and tasked with accelerating state and local government innovation.

Challenge

Advocates of abundance have identified “failed public policy” as an increasingly significant barrier to economic growth and community flourishing. Of particular concern are state and local policies and programs, including those powered by federal funds, that do not effectively deliver critically important public goods and services like health, education, safety, clean air and water, and growth-oriented infrastructure.

Part of the challenge is that state and local governments lack capacity to conduct rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of their policies and programs. For example, the American Rescue Plan, the largest one-time federal investment in state and local governments in the last century, provided $350 billion in State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to state, territorial, local, and Tribal governments to accelerate post-pandemic economic recovery. Yet very few of those investments are being evaluated for efficacy. In a recent survey of state policymakers, 59% of those surveyed cited “lack of time for rigorous evaluations” as a key obstacle to innovation. State and local governments also typically lack the time, resources, and technical capacity to canvass evaluation evidence from other settings and assess whether a program proven to improve outcomes elsewhere might also improve outcomes locally. Finally, state and local governments often don’t adopt more effective programs even when they have rigorous evidence that these programs are more effective than the status quo, because implementing new programs disrupts existing workflows.

If state and local policymakers don’t know what works and what doesn’t, and/or aren’t able to overcome even relatively minor implementation challenges when they do know what works, they won’t be able to spend federal dollars more effectively, or more generally to deliver critical public goods and services.

Opportunity

A growing body of research on government innovation is documenting factors that reliably increase the likelihood that governments will implement evidence-based policy reform. First, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are grounded in local evidence and/or recommended by local researchers. Boston-based researchers sharing a Boston-based study showing that relaxing density restrictions reduces rents and house prices will do less to convince San Francisco decision makers than either a San Francisco-based study, or San Francisco-based researchers endorsing the evidence from Boston. Proximity matters for government innovation.

Second, government decision makers are more likely to adopt evidence-based policy reforms when they are engaged as partners in the research projects that produce the evidence of efficacy, helping to define the set of feasible policy alternatives and design new policy interventions. Research partnerships matter for government innovation.

Third, evidence-based policies are significantly more likely to be adopted when the policy innovation is part of an existing implementation infrastructure, or when agencies receive dedicated implementation support. This means that moving beyond incremental policy reforms will require that state and local governments receive more technical support in overcoming implementation challenges. Implementation matters for government innovation.

We know that the implementation of evidence-based policy reform produces returns for communities that have been estimated to be on the order of 17:1. Our partners in government have voiced their direct experience of these returns. In Puerto Rico, for example, decision makers in the Department of Education have attributed the success of evidence-based efforts to help students learn to the “constant communication and effective collaboration” with researchers who possessed a “strong understanding of the culture and social behavior of the government and people of Puerto Rico.” Carrie S. Cihak, the evidence and impact officer for King County, Washington, likewise observes,

“It is critical to understand whether the programs we’re implementing are actually making a difference in the communities we serve. Throughout my career in King County, I’ve worked with County teams and researchers on evaluations across multiple policy areas, including transportation access, housing stability, and climate change. Working in close partnership with researchers has guided our policymaking related to individual projects, identified the next set of questions for continual learning, and has enabled us to better apply existing knowledge from other contexts to our own. In this work, it is essential to have researchers who are committed to valuing local knowledge and experience–including that of the community and government staff–as a central part of their research, and who are committed to supporting us in getting better outcomes for our communities.”

The emerging body of evidence on the determinants of government innovation can help us define a plan of action that galvanizes the state and local government innovation necessary to accelerate regional economic growth and community flourishing.

Plan of Action

An evidence-based plan to increase state and local government innovation needs to facilitate and sustain durable partnerships between state and local governments and neighboring universities to produce scientifically rigorous policy evaluations, adapt evaluation evidence from other contexts, and develop effective implementation strategies. Over a century ago, the Hatch Act of 1887 created a remarkably effective and durable R&D infrastructure aimed at agricultural innovation, establishing university-based Agricultural Experiment Stations (AES) in each state tasked with developing, testing, and translating innovations designed to increase agricultural productivity.

Locating university-based AES in every state ensured the production and implementation of locally-relevant evidence by researchers working in partnership with local stakeholders. Federal oversight of the state AES by an Office of Experiment Stations in the US Department of Agriculture ensured that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. Finally, providing stable annual federal appropriations for the AES, with required matching state appropriations, ensured the durability and financial sustainability of the R&D infrastructure. This infrastructure worked: agricultural productivity near the experiment stations increased by 6% after the stations were established.

Congress should develop new legislation to create and fund a network of state-based “Policy Experiment Stations.”

The 119th Congress that will convene on January 3, 2025 can adapt the core elements of the proven-effective network of state-based Agricultural Experiment Stations to accelerate state and local government innovation. Mimicking the structure of 7 USC 14, federal grants to states would support university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, tasked with partnering with state and local governments on (1) scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of state and local policies and programs; (2) translations of evaluation evidence from other settings; and (3) overcoming implementation challenges.

As in 7 USC 14, grants to support state policy innovation labs would be overseen by a federal office charged with ensuring that work was conducted with scientific rigor and that local evidence was shared across sites. We see two potential paths for this oversight function, paths that in turn would influence legislative strategy.

Pathway 1: This oversight function could be located in the Office of Evaluation Sciences (OES) in the General Services Administration (GSA). In this case, the congressional committees overseeing GSA, namely the House Committee on Oversight and Responsibility and the Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, would craft legislation providing for an appropriation to GSA to support a new OES grants program for university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that OES is a highly respected locus of program and policy evaluation expertise.

Pathway 2: Oversight could instead be located in the Directorate of Technology, Innovation, and Partnerships in the National Science Foundation (NSF TIP). In this case, the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation would craft legislation providing for a new grants program within NSF TIP to support university-based policy innovation labs in each state. The advantage of this structure is that NSF is a highly respected grant-making agency.

Either of these paths is feasible with bipartisan political will. Alternatively, there are unilateral steps that could be taken by the incoming administration to advance state and local government innovation. For example, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) recently released updated Uniform Grants Guidance clarifying that federal grants may be used to support recipients’ evaluation costs, including “conducting evaluations, sharing evaluation results, and other personnel or materials costs related to the effective building and use of evidence and evaluation for program design, administration, or improvement.” The Uniform Grants Guidance also requires federal agencies to assess the performance of grant recipients, and further allows federal agencies to require that recipients use federal grant funds to conduct program evaluations. The incoming administration could further update the Uniform Grants Guidance to direct federal agencies to require that state and local government grant recipients set aside grant funds for impact evaluations of the efficacy of any programs supported by federal funds, and further clarify the allowability of subgrants to universities to support these impact evaluations.

Conclusion

Establishing a national network of university-based “Policy Experiment Stations” or policy innovation labs in each state, supported by continuing federal and state appropriations, is an evidence-based plan to facilitate abundance-oriented state and local government innovation. We already have impressive examples of what these policy labs might be able to accomplish. At MIT’s Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab North America, the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab and Education Lab, the University of California’s California Policy Lab, and Harvard University’s The People Lab, to name just a few, leading researchers partner with state and local governments on scientifically rigorous evaluations of the efficacy of public policies and programs, the translation of evidence from other settings, and overcoming implementation challenges, leading in several cases to evidence-based policy reform. Yet effective as these initiatives are, they are largely supported by philanthropic funds, an infeasible strategy for national scaling.

In recent years we’ve made massive investments in communities through federal grants to state and local governments. We’ve also initiated ambitious efforts at growth-oriented regulatory reform which require not only federal but also state and local action. Now it’s time to invest in building state and local capacity to deploy federal investments effectively and to galvanize regional economic growth. Emerging research findings about the determinants of government innovation, and about the efficacy of the R&D infrastructure for agricultural innovation established over a century ago, give us an evidence-based roadmap for state and local government innovation.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Promoting American Resilience Through a Strategic Investment Fund

Critical minerals, robotics, advanced energy systems, quantum computing, biotechnology, shipbuilding, and space are some of the resources and technologies that will define the economic and security climate of the 21st century. However, the United States is at risk of losing its edge in these technologies of the future. For instance, China processes the vast majority of the world’s batteries and critical metals and has successfully launched a quantum communications satellite. The implications are enormous: the U.S. relies on its qualitative technological edge to fuel productivity growth, improve living standards, and maintain the existing global order. Indeed, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and CHIPS Act were largely reactionary moves to shore up atrophied manufacturing capabilities in the American battery and semiconductor industries, requiring hundreds of billions in outlays to catch up. In an ideal world, critical industries would be sufficiently funded well in advance to avoid economically costly catch-up spending.

However, many of these technologies are characterized by long timelines, significant capital expenditures, and low and uncertain profit margins, presenting major challenges for private-sector investors who are required by their limited partners (capital providers such as pension funds, university endowments, and insurance companies) to underwrite to a certain risk-adjusted return threshold. This stands in contrast to technologies like artificial intelligence and pharmaceuticals: While both are also characterized by large upfront investments and lengthy research and development timelines, the financial payoffs are far clearer, incentivizing private sectors to play a leading role in commercialization. This issue for technologies in economically and geopolitically vital industries such as lithium processing and chips is most acute in the “valley of death,” when companies require scale-up capital for an early commercialization effort: the capital required is too large for traditional venture capital, yet too risky for traditional project finance.

The United States needs a strategic investment fund (SIF) to shepherd promising technologies in nationally vital sectors through the valley of death. An American SIF is not intended to provide subsidies, pick political winners or losers, or subvert the role of private capital markets. On the contrary, its role would be to “crowd in” capital by uniquely managing risk that no private or philanthropic entities have the capacity to do. In doing so, an SIF would ensure that the U.S. maintains an edge in critical technologies, promoting economic dynamism and national security in an agile, cost-efficient manner.

Challenges

The Need for Private Investment

A handful of resources and technologies, some of which have yet to be fully characterized, have the potential to play an outsized role in the future economy. Most of these key technologies have meaningful national security implications.

Since ChatGPT’s release in November 2022, artificial intelligence (AI) has experienced a commercial renaissance that has captured the public’s imagination and huge sums of venture dollars, as evidenced by OpenAI’s October 2024 $6.5 billion round at a $150 billion pre-money valuation. However, AI is not the only critical resource or technology that will power the future economy, and many of those critical resources and technologies may struggle to attract the same level of private investment. Consider the following:

- To meet climate goals, the world needs to increase production of lithium by nearly 475%, rare earths by 100%, and nickel by 60% through 2035. For defense applications, rare earths are especially important; the construction of one F-35, for instance, uses 920 pounds of rare earth materials.

- The conflict in Ukraine has unequivocally demonstrated the value of low-cost drones on the battlefield. However, drones also have significant commercial applications, including safety and last-mile delivery. Reducing production and component costs could make a meaningful difference.

- Quantum technology has the potential to exponentially expand compute power, which can be used to simulate biological pathways, accelerate materials development, and process vast amounts of financial data. However, quantum technology can also be used to break existing encryption technologies and safeguard communications. China launched its first quantum communications satellite in 2020.

Few sectors receive the level of consistent venture attention that software technology, most recently in AI, has gotten in the last 18 months. However, this does not make them unbackable or unimportant; on the contrary, technologies that increase mineral recovery yields or make drone engines cheaper should receive sufficient support to get to scale. While private-sector capital markets have supported the development of many important industries, they are not perfect and may miss important opportunities due to information asymmetries and externalities.

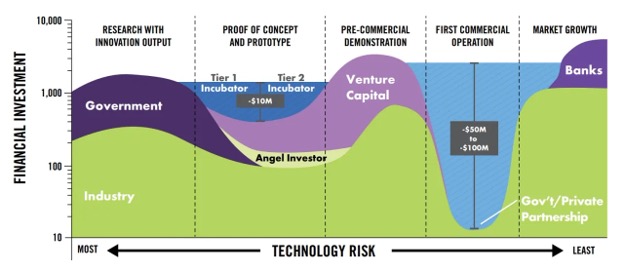

Overcoming the Valley of Death

Many strategically important technologies are characterized by high upfront costs and low or uncertain margins, which tends to dissuade investment by private-sector organizations at key inflection points, namely, the “valley of death.”

By their nature, innovative technologies are complex and highly uncertain. However, some factors make future economic value—and therefore financeability—more difficult to ascertain than others. For example, innovative battery technologies that enable long-term storage of energy generated from renewables would greatly improve the economics of utility-scale solar and wind projects. However, this requires production at scale in the face of potential competition from low-cost incumbents. In addition, there is the element of scientific risk itself, as well as the question of customer adoption and integration. There are many good reasons why technologies and companies that seem feasible, economical, and societally valuable do not succeed.

These dynamics result in lopsided investment allocations. In the early stages of innovation, venture capital is available to fund startups with the promise of outsized return driven partially by technological hype and partially by the opportunity to take large equity stakes in young companies. At the other end of the barbell, private equity and infrastructure capital are available to mature companies seeking an acquisition or project financing based on predictable cash flows and known technologies.

However, gaps appear in the middle as capital requirements increase (often by an order of magnitude) to support the transition to early commercialization. This phenomenon is called the “valley of death” as companies struggle to raise the capital they need to get to scale given the uncertainties they face.

Figure 1. The “valley of death” describes the mismatch between existing financial structures and capital requirements in the crucial early commercialization phase. (Source: Maryland Energy Innovation Accelerator)

Shortcoming of Federal Subsidies

While the federal government has provided loans and subsidies in the past, its programs remain highly reactive and require large amounts of funding.

Aside from asking investors to take on greater risk and lower returns, there are several tools in place to ameliorate the valley of death. The IRA one such example: It appropriated some $370 billion for climate-related spending with a range of instruments, including tax subsidies for renewable energy production, low-cost loans through organizations such as the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office (LPO), and discretionary grants.

On the other hand, there are major issues with this approach. First, funding is spread out across many calls for funding that tend to be slow, opaque, and costly. Indeed, it is difficult to keep track of available resources, funding announcements, and key requirements—just try searching for a comprehensive, easy-to-understand list of opportunities.

More importantly, these funding mechanisms are simply expensive. The U.S. does not have the financial capacity to support an IRA or CHIPS Act for every industry, nor should it go down that route. While one could argue that these bills reflect the true cost of achieving the stated policy aims of energy transition or securing the semiconductor supply chain, it is also the case that there both knowledge (engineering expertise) and capital (manufacturing facility) capabilities underpin these technologies. Allowing these networks to atrophy created greater costs down the road, which could have been prevented by targeted investments at the right points of development.

The Future Is Dynamic

The future is not perfectly knowable, and new technological needs may arise that change priorities or solve previous problems. Therefore, agility and constant re-evaluation are essential.

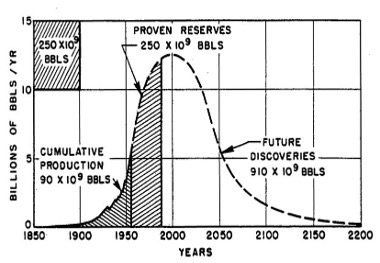

Technological progress is not static. Take the concept of peak oil: For decades, many of the world’s most intelligent geologists and energy forecasters believed that the world would quickly run out of oil reserves as the easiest to extract resources were extracted. In reality, technological advances in chemistry, surveying, and drilling enabled hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling, creating access to “unconventional reserves” that substantially increased fossil fuel supply.

Figure 2. In 1956, M.K. Hubbert created “peak oil” theory, projecting that reserves would be exhausted around the turn of the millennium.

Fracking greatly expanded fossil fuel production in the U.S., increasing resource supply, securing greater energy independence, and facilitating the transition from coal to natural gas, whose expansion has proved to be a helpful bridge towards renewable energy generation. This transition would not have been possible without a series of technological innovations—and highly motivated entrepreneurs—that arose to meet the challenge of energy costs.

To meet the challenges of tomorrow, policymakers need tools that provide them with flexible and targeted options as well as sufficient scale to make an impact on technologies that might need to get through the valley of death. However, they need to remain sufficiently agile so as not to distort well-functioning market forces. This balance is challenging to achieve and requires an organizational structure, authorizations, and funding mechanisms that are sufficiently nimble to adapt to changing technologies and markets.

Opportunity

Given these challenges, it seems unlikely that solutions that rely solely on the private sector will bridge the commercialization gap in a number of capital-intensive strategic industries. On the other hand, existing public-sector tools, such as grants and subsidies, are too costly to implement at scale for every possible externality and are generally too retrospective in nature rather than forward-looking. The government can be an impactful player in bridging the innovation gap, but it needs to do so cost-efficiently.

An SIF is a promising potential solution to the challenges posed above. By its nature, an SIF would have a public mission focused on strategic technologies crossing the valley of death by using targeted interventions and creative financing structures that crowd in private investors. This would enable the government to more sustainably fund innovation, maintain a light touch on private companies, and support key industries and technologies that will define the future global economic and security outlook.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Shepherd technologies through the valley of death.

While the SIF’s investment managers are expected to make the best possible returns, this is secondary to the overarching public policy goal of ensuring that strategically and economically vital technologies have an opportunity to get to commercial scale.

The SIF is meant to crowd in capital such that we achieve broader societal gains—and eventually, market-rate returns—enabled by technologies that would not have survived without timely and well-structured funding. This creates tension between two competing goals: The SIF needs to act as if it will intend to make returns, or else there is the potential for moral hazard and complacency. However, it also has to be willing to not make market-rate returns, or even lose some of its principal, in the service of broader market and ecosystem development.

Thus, it needs to be made explicitly clear from the beginning that an SIF has the intent of achieving market rate returns by catalyzing strategic industries but is not mandated to do so. One way to do this is to adopt a 501(c)(3) structure that has a loose affiliation to a department or agency, similar to that of In-Q-Tel. Excess returns could either be recycled to the fund or distributed to taxpayers.

The SIF should adapt the practices, structures, and procedures of established private-sector funds. It should have a standing investment committee made up of senior stakeholders across various agencies and departments (expanded upon below). Its day-to-day operations should be conducted by professionals who provide a range of experiences, including investing, engineering and technology, and public policy across a spectrum of issue areas.

In addition, the SIF should develop clear underwriting criteria and outputs for each investment. These include, but are not limited to, identifying the broader market and investment thesis, projecting product penetration, and developing potential return scenarios based on different permutations of outcomes. More critically, each investment needs to create a compelling case for why the private sector cannot fund commercialization on its own and why public catalytic funding is essential.

Recommendation 2. The SIF should have a permanent authorization to support innovation under the Department of Commerce.

The SIF should be affiliated with the Department of Commerce but work closely with other departments and agencies, including the Department of Energy, Department of Treasury, Department of Defense, Department of Health and Human Services, National Science Foundation, and National Economic Council.

Strategic technologies do not fall neatly into one sector and cut across many customers. Siloing funding in different departments misses the opportunity to capture funding synergies and, more importantly, develop priorities that are built through information sharing and consensus. Enter the Department of Commerce. In addition to administering the National Institute of Standards and Technology, they have a strong history of working across agencies, such as with the CHIPS Act.

Similar arguments can also be made for the Treasury, and it may even be possible to have Treasury and Commerce work together to manage an SIF. They would be responsible for bringing in subject matter experts (for example, from the Department of Energy or National Science Foundation) to provide specific inputs and arguments for why specific technologies need government-based commercialization funding and at what point such funding is appropriate, acting as an honest broker to allocate strategic capital.

To be clear: The SIF is not intended to supersede any existing funding programs (e.g., the Department of Energy’s Loan Program Office or the National Institute of Health’s ARPA-H) that provide fit-for-purpose funding to specific sectors. Rather, an SIF is intended to fill in the gaps and coordinate with existing programs while providing more creative financing structures than are typically available from government programs.

Recommendation 3. Create a clear innovation roadmap.

Every two years, the SIF should develop or update a roadmap of strategically important industries, working closely with private, nonprofit, and academic experts to define key technological and capability gaps that merit public sector investment.

The SIF’s leaders should be empowered to make decisions on areas to prioritize but have the ability to change and adapt as the economic environment evolves. Although there is a long list of industries that an SIF could potentially support, resources are not infinite. However, a critical mass of investment is required to ensure adequate resourcing. One acute challenge is that this is not perfectly known in advance and changes depending on the technology and sector. However, this is precisely what the strategic investment roadmap is supposed to solve for: It should provide an even-handed assessment of the likely capital requirements and where the SIF is best suited to provide funding compared to other agencies or the private sector.

Moreover, given the ever-changing nature of technology, the SIF should frequently reassess its understanding of key use cases and their broader economic and strategic importance. Thus, after initial development of the SIF, it should be updated every two years to ensure that its takeaways and priorities remain relevant. This is no different than documents such as the National Security Strategy, which are updated every two to four years; in fact, the SIF’s planning documents should flow seamlessly into the National Security Strategy.

To provide a sufficiently broad set of perspectives, the government should include the expertise and insights of outside experts to develop its plan. Existing bodies, such as the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology and the National Quantum Initiative, provide some of the consultative expertise required. However, the SIF should also stand up subject matter specific advisory bodies where a need arises (for example, on critical minerals and mining) and work internally to set specific investment areas and priorities.

Recommendation 4. Limit the SIF to financing.

The government should not be an outsized player in capital markets. As such, the SIF should receive no governance rights (e.g., voting or board seats) in the companies that it invests in.

Although the SIF aims to catalyze technological and ecosystem development, it should be careful not to dictate the future of specific companies. Thus, the SIF should avoid information rights beyond financial reporting. Typical board decks and stockholder updates include updates on customers, technologies, personnel matters, and other highly confidential and specific pieces of information that, if made public through government channels, would play a highly distortionary role in markets. Given that the SIF is primarily focused on supporting innovation through a particularly tricky stage to navigate, the SIF should receive the least amount of information possible to avoid disrupting markets.

Recommendation 5. Focus on providing first-loss capital.

First-loss capital should be the primary mechanism by which the SIF supports new technologies, providing greater incentives for private-sector funders to support early commercialization while providing a means for taxpayers to directly participate in the economic upside of SIF-supported technologies.

Consider the following stylized example to demonstrate a key issue in the valley of death. A promising clean technology company, such as a carbon-free cement or long-duration energy storage firm, is raising $100mm of capital for facility expansion and first commercial deployment. To date, the company has likely raised $30 – $50mm of venture capital to enable tech development, pilot the product, and grow the team’s engineering, R&D, and sales departments.

However, this company faces a fundraising dilemma. Its funding requirements are now too big for all but the largest venture capital firms, who may or may not want to invest in projects and companies like these. On the other hand, this hypothetical company is not mature enough for private equity buyouts nor is it a good candidate for typical project-based debt, which typically require several commercial proof points in order to provide sufficient risk reduction for an investor whose upside is relatively limited. Hence, the “valley of death.”

First-loss capital is an elegant solution to this issue: A prospective funder could commit to equal (pro rata) terms as other investors, except that this first-loss funder is willing to use its investment to make other investors whole (or at least partially offset losses) in the event that the project or company does not succeed. In this example, a first-loss funder would commit to $33.5 million of equity funding (roughly one-third of the company’s capital requirement). If the company succeeds, the first-loss funder makes the same returns as the other investors. However, if the company is unable to fully meet these obligations, the first-loss funder’s $33.5 million would be used to pay the other investors back (the other $66.5 million that was committed). This creates a floor on losses for the non-first-loss investors: Rather than being at risk of losing 100% of their principal, they are at risk of losing 50% of their principal.

The creation of a first-loss layer has a meaningful impact on the risk-reward profile for non-first-loss investors, who now have a floor on returns (in the case above, half their investment). By expanding the acceptable potential loss ratio, growth equity capital (or another appropriate instrument, such as project finance) can fill the rest, thereby crowding in capital.

From a risk-adjusted returns standpoint, this is not a free lunch for the government or taxpayers. Rather, it is intended to be a capital-efficient way of supporting the private-sector ecosystem in developing strategically and economically vital technologies. In other words, it leverages the power of the private sector to solve externalities while providing just enough support to get them to the starting line in the first place.

Conclusion

Many of tomorrow’s strategically important technologies face critical funding challenges in the valley of death. Due to their capital intensity and uncertain outcomes, existing financing tools are largely falling short in the critical early commercialization phases. However, a nimble, properly funded SIF could bridge key gaps while allowing the private sector to do most of the heavy lifting. The SIF would require buy-in from many stakeholders and well-defined sources of funding, but these can be solved with the right mandates, structures, and pay-fors. Indeed, the stakes are too high, and the consequences too dire, to not get strategic innovation right in the 21st century.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Put simply, there needs to be an entity that is actually willing and able to absorb lower returns, or even lose some of its principal, in the service of building an ecosystem. Even if the “median” outcome is a market-rate return of capital, the risk-adjusted returns are in effect far lower because the probability of a zero outcome for first-loss providers is substantially nonzero. Moreover, it’s not clear exactly what the right probability estimate should be; therefore, it requires a leap of faith that no economically self-interested private market actor would be willing to take. While some quasi-social-sector organizations can play this role (for example, Bill Gates’s Breakthrough Energy Ventures for climate tech), their capacity is finite, nor is there a guarantee that such a vehicle will appear for every sector of interest. Therefore, a publicly funded SIF is an integral solution to bridging the valley of death.

No, the SIF would not always have to use first-loss structures. However, it is the most differentiated structure that is available to the U.S. government; otherwise, a private-sector player is likely able—and better positioned—to provide funding.

The SIF should be able to use the full range of instruments, including project finance, corporate debt, convertible loans, and equity capital, and all combinations thereof. The instrument of choice should be up to the judgment of the applicant and SIF investment team. This is distinct from providing first-loss capital: Regardless of the financial instrument used, the SIF’s investment would be used to buffer other investors against potential losses.

The target return rate should be commensurate with that of the instrument used. For example, mezzanine debt should target 13–18% IRR, while equity investments should aim for 20–25% IRR. However, because of the increased risk of capital loss to the SIF given its first loss position, the effective blended return should be expected to be lower.

The SIF should be prepared to lose capital on each individual investment and, as a blended portfolio, to have negative returns. While it should underwrite such that it will achieve market-rate returns if successful in crowding in other capital that improves the commercial prospects of technologies and companies in the valley of death, the SIF has a public goal of ecosystem development for strategic domains. Therefore, lower-than-market-rate returns, and even some principal degradation, is acceptable but should be avoided as much as possible through the prudence of the investment committee.